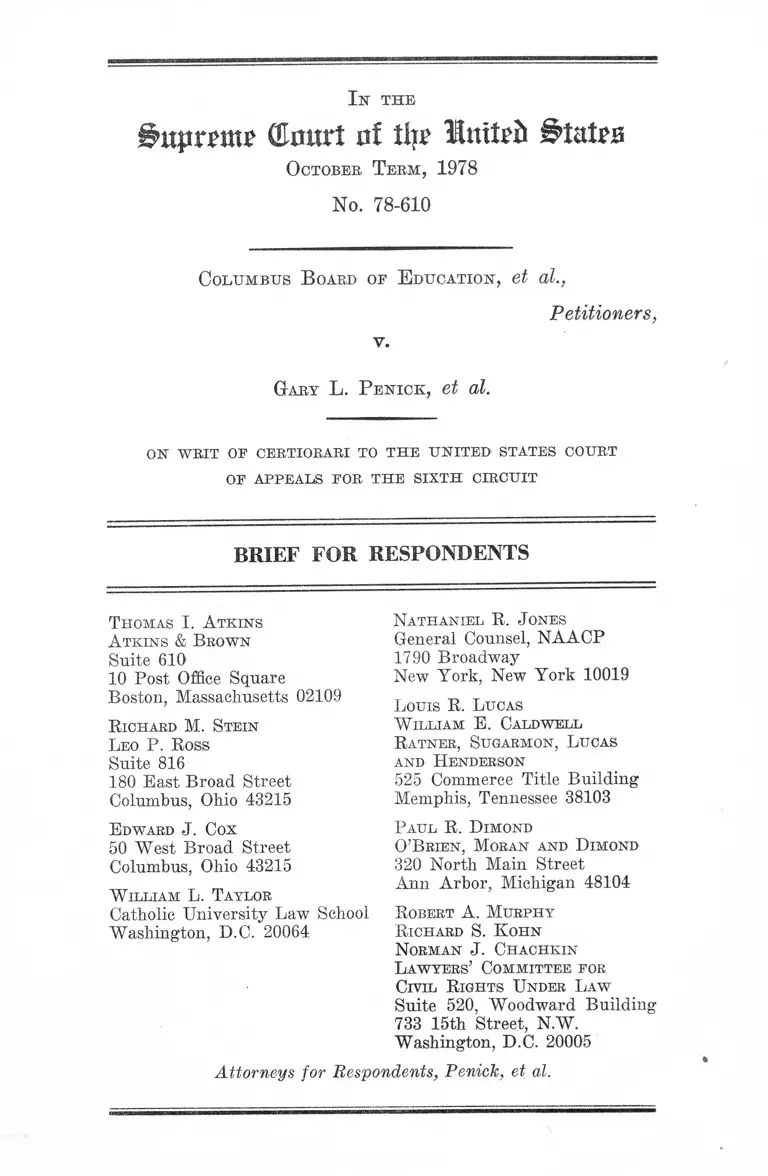

Columbus Board of Education v. Penick Brief for Respondents

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Columbus Board of Education v. Penick Brief for Respondents, 1979. 10ec6d0b-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0a2f066b-cc9f-4c2d-884e-7850fcbd40cb/columbus-board-of-education-v-penick-brief-for-respondents. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Supreme (tart at tip Initrd

October T eem , 1978

No. 78-610

1st th e

Columbus B oard op E ducation, et al.,

v .

Petitioners,

Gary L. Penick, et al.

ON W R IT OP CERTIORARI TO T H E U N IT E D STATES COURT

OP APPEALS FOR T H E S IX T H CIRCU IT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

Thomas I. A tkins

A tkins & Brown

Suite 610

10 Post Office Square

Boston, Massachusetts 02109

Richard M. Stein

Leo P. Ross

Suite 816

180 East Broad Street

Columbus, Ohio 43215

Edward J. Cox

50 West Broad Street

Columbus, Ohio 43215

W illiam L. Taylor

Catholic University Law School

Washington, D.C. 20064

Nathaniel R. Jones

General Counsel, NAACP

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

Louis R. Lucas

W illiam E. Caldwell

Ratner, Sugarmon, Lucas

and Henderson

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Paul R. Dimond

O’Brien, Moran and Dimond

320 North Main Street

Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104

Robert A. Murphy

Richard S. K ohn

Norman J. Chachkin

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

Suite 520, Woodward Building

733 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

Attorneys for Respondents, Penick, et al.

I N D E X

Table of Authorities ....................................................... v

Questions Presented ..... 1

Statement of the Case ..... ................................... ............. 2

Statement of Facts

Introduction .................................................................. 3

A. Pre-1954 Operation of the Columbus Public

Schools .............. 10

1. Demography.................................... 10

2. Early history: compulsory segregation ....... 11

3. Segregation ended and reinstated................. 12

4. Extending segregation: grade restructur

ing, optional zones, faculty replacement,

boundary changes, and gerrymandering .... 15

B. Post-Brown Administration of the Schools ..... 22

1. Demography ................................................. 23

2. Post-Brown actions leading to segregation .. 28

a. Faculty and staff assignment policies .... 29

b. Application of the “neighborhood school”

policy ............................................................ 32

c. Deviation from the “neighborhood school”

system ............. 37

Optional attendance areas ..... 38

Discontiguous attendance areas........... 40

PAGE

11

Segregative relocation of classes in

PAGE

other schools ........................................... 41

Rental facilities ....................................... 42

Construction and boundary establish

ment .......................................................... 43

d. The 1950’s .................................................. 45

e. The 1960’s .................................................... 56

f. The 1970’s .................................................... 81

g. Summary .................................................... 86

C. Impact on Current Segregation of Schools....... 87

D. The Remedy Proceedings ................................... 94

Summary of Argum ent...................................................... 96

A rgument—

I. The Evidence Overwhelmingly Supports the Dis

trict Court’s Conclusion of Systemwide Constitu

tional Violations by Columbus School Authorities 100

A. Plaintiffs Proved a Pattern and Practice of

Segregation by Columbus Defendants and

Their Predecessors in Office Which Fully

Justified the Trial Court’s Holding of System-

wide Liability, Irrespective of Any Eviden

tiary Presumptions Operating in Plaintiffs’

Favor ...................................................................... 100

I l l

B. The District Court’s Consideration of Peti

tioners’ Claimed Adherence to a “Neighbor

hood School” Policy, and of the Degree to

Which Segregative Results of Their Actions

Were Known or Foreseeable, in Reaching the

Ultimate Conclusion That There Was a Sys

temwide Policy of Segregation in Columbus

Was Not Inconsistent With Washington v.

Davis or Arlington Heights ........................ 109

C. The Systemwide Violation Finding Also Is

Consistent With the Procedures and Eviden

tiary Presumption Established by This Court

in Keyes ................................................................ 118

II. The District Court Acted Correctly in Requir

ing a Comprehensive, Systemwide Desegregation

Plan Which Promised to “Achieve The Greatest

Possible Degree Of Actual Desegregation, Tak

ing Into Account The Practicalities Of The

Situation” .................................................................... 124

A. There Was No Error in Putting the Burden

on Petitioners to Demonstrate That the Racial

Composition of Schools Omitted From Their

Proposed Remedial Plans Was Unaffected by

PAGE

Their Constitutional Violations ....................... 124

B. The District Court’s Rejection of the Board’s

June 10 and July 8 Plans “Was Compelled by

Green and Swann............................................ . 129

IV

III. Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman Did Not,

and Should Not Be Interpeted to, Change the

Foregoing Principles; and the Interpretation of

That Decision Urged by Petitioners Unduly Lim

its the Remedial Discretion of Federal Courts .... 133

A. Dayton I Did Not Overrule Keyes or the Other

Decisions Upon Which Plaintiffs Rely; Since

the Courts Below Properly Applied the Prin

ciples of Swann and Keyes to the Proof and

Findings in the Record, No Modification of

Their Judgments Is Indicated by Dayton I .... 134

B. Dayton I Should Not Be Extended to Displace

the Evidentiary Rules Announced in Keyes;

the Record Here Confirms the Wisdom of

Keyes’ Prima Facie Case Approach to the

Determination of the Nature and Extent of

the Constitutional Violation in School De

segregation Cases .............................................. 139

C. The Formula Advanced by Petitioners Would

Deprive Federal District Courts Sitting as

Equity Tribunals in School Desegregation

Cases of the Discretion and Breadth of Reme

dial Authority Which This Court Has Con

sistently Upheld as Necessary to Effective Im

plementation of the Constitutional Provisions

PAGE

Here at Issue ...................................................... 151

Conclusion ................................................. .............. ........... 156

A ppendix—

School Segregation and Residential Segregation:

A Social Science Statement ........ .............................. la

V

T able op A uthorities

Cases: page

Arthur v. Nyquist, 573 F. 2d 134 (2d Cir. 1978), cert.

denied, 47 U.S.L.W. 3324 (Oct. 2, 1978) ................... 114n

Austin Independent School Dist. v. United States, 429

U.S. 990 (1976) .......................................................111,115x1

Berenyi v. Immigration Serv., 385 U.S. 630 (1967) .... 4n

Board of Educ. v. State, 45 Ohio St. 555, 16 N.E. 373

(1888) ......................................... 14n

Booker v. Special School Dist. No. 1, 351 F. Supp. 799

(IX Minn. 1972) .................................... ................. ..106,108

Bradley v. Milliken, 338 F. Supp. 582 (E.D. Mich.

1971), appeal dismissed, 468 F. 2d 902 (6th Cir.),

cert, denied, 409 U.S. 844 (1972), aff’d 484 F. 2d 215

(6th Cir. 1973) (en banc), aff’d in pertinent part,

418 U.S. 717 (1974) .................................... ....... 106-07,108

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 382 U.S. 103

(1965) ............................... ................................................149 n

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 345 F. 2d 310 (4th

Cir. 1965) .............................. ....................... ........... . ,U9ii

Brainard v. Buck, 184 U.S. 99 (1902) ...... ................ 4n, 105

Brennan v. Armstrong, 433 U.S. 672 (1977) .......137n, 138

Brewer v. School Bd, of Norfolk, 397 F. 2d 37 (4th

Cir. 1968) .......................................................... 34n, 127,151

Brinkman v. Gilligan, 578 F. 2d 853 (6th Cir. 1975)

135n

Brinkman v. Gilligan, 503 F. 2d 684 (6th Cir. 1974)

134

Brown v. Board of Educ., 349 U.S. 294 (1955) ......... . 6

Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954) .......passim

Brunson v. Board of Trustees, 429 F. 2d 820 (4th Cir.

1970) ............ ............................................... 149n

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917) ...................... 143

VI

City of Richmond v. Deans, 281 U.S. 704 (1930) ....... 143

Clark v. Board of Educ., 426 F. 2d 1035 (8th Cir.),

cert, denied, 402 U.S. 952 (1971) .............................. 127

Clemons v. Board of Educ. of Hillsboro, 228 F. 2d 853

(6th Cir. 1956) ................. ........ ..... ............ ....... -.......... 107

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ...............................123n

Davis v. Board of School Comm’rs, 402 U.S. 33 (1971)

123,124n

Davis v. School Dist. of Pontiac, 443 F. 2d 573 (6th

Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 913 (1971) ..................... 103

Davis v. School Dist. of Pontiac, 309 F. Supp. 734

(EJD. Mich. 1970), aff’d 443 F. 2d 573 (6th Cir.),

cert, denied, 404 U.S. 913 (1971) ..........................103,108

Dayton Bd. of Educ. v. Brinkman, 433 U.S. 406 (1977)

passim

Ellis v. Board of Public Instruction, 423 F. 2d 203 (5th

Cir. 1970) ........................................................................ 117n

Ford Motor Co. v. United States, 405 U.S. 562 (1972) .. 152

Goss v. Board of Educ. of Knoxville, 373 U.S. 683

(1963) ................................................. 39n

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County, 391

U.S. 430 (1968) .............................6,98,99,124,125n,127,

129,138,149,150,155

Harrington v. Colquitt County Bd. of Educ., 460 F. 2d

193 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 915 (1972) ...... 154

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dist.,

409 F. 2d 682 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 396 U.S. 940

(1969) .............................................................................. 127

Higgins v. Board of Educ. of Grand Rapids, 508 F. 2d

779 (6th Cir. 1974) ............................................... 147-48

PAGE

V ll

Jones v. Alfred II. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968)

26n, 149n

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ., Civ. No.

2094 (M.D. Tenn., July 15, 1971), aff’d 463 F. 2d 732

(6th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1001 (1972) ........... 154

Kelly v. Guinn, 456 F. 2d 100 (9th Cir. 1972), cert.

denied, 413 U.S. 919 (1973) ............... ......................... 108

Kemp v. Beasley, 423 F. 2d 851 (8th Cir. 1970) ........... 149

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, 413 U.S. 189

(1973) .................................................................... ..... passim

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, 303 F. Supp.

279, 289 (D. Colo. 1969), aff’d 445 F. 2d 990 (10th

Cir. 1971), vacated and remanded on other grounds,

413 U.S. 189 (1973) ....... ............................... ......... 27n, 113

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268 (1939) ......................... 142

Lee v. Nyquist, 318 F. Supp. 710 (W.D.N.Y. 1970)

(three-judge court), aff’d 402 U.S. 935 (1971) .......126n

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) .........._152n

Massachusetts Mut. Life Ins. Co. v. Ludwig, 426 U.S.

479 (1976) .............................................. ......................... 10

McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39 (1971) ....................... 149

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (1977) .......144,148,149,

151,152,153,154-55

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974) ....27n, 126n, 144n

Monroe v. Board of Comm’rs, 427 F. 2d 1005 (6t,h Cir.

1970) .................................................................. . 127

Monroe v. Board of Comm’rs of Jackson, 391 U.S. 430

(1968) ..... ................... ..... ............................ ........ ........... 125

Morgan v. Hennigan, 370 F. Supp. 410 (D. Mass.),

aff’d sub nom. Morgan v. Kerrigan, 509 F.2d 580

(1st Cir. 1974), cert, denied, 421 U.S. 963 (1975).....103,

108,117

PAGE

Y l l l

Moses v. Washington Parish School Bd., 276 F. Supp.

834 (E.D. La. 1967) ...................................................... 39n

NAACP v. Lansing Bd. of Educ., 429 F. Supp. 583

(W.D. Mich. 1973), aff’d 559 F. 2d 1042 (6th Cir.

1977), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1065 (1978) ________ 107n

North Carolina State Bd. of Educ. v. Swann, 402 U.S.

43 (1971) ........................................................ 123n, 126n, 149

Oliver v. Kalamazoo Bd. of Educ., 368 F. Supp. 143

(W.D. Mich. 1973), aff’d sub nom. Oliver v. Michigan

State Bd. of Educ., 408 F. 2d 178 (6th Cir. 1974),

cert, denied, 421 U.S. 963 (1975) .............103-04,106,108

Oliver y. Michigan State Bd. of Educ., 408 F. 2d 178

(6th Cir. 1974), cert, denied, 421 U.S. 963 (1975)

114n, 116,118n, 129

Pasadena City Bd. of Educ. v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424

(1976) ......................................... 123-24,150

Pate v. Dade County School Bd., 434 F. 2d 1151 (5th

Cir. 1970) ........................................................................ 132

Raney v. Board of Educ. of Gould, 391 U.S. 443 (1968) 125

Reed v. Cleveland Bd. of Educ., 481 F. 2d 570 (6th

Cir. 1978) ........................................................................ 148

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) ............ ....... ........ 149n

San Antonio Independent School Dist. v. Rodrigues,

411 U.S. 1 (1973) ............... ............ ....... ...................... 126n

School Dist. of Omaha v. United States, 433 U.S. 667

(1977) ......................... ....... .......................................137n, 138

Sloan v. Tenth School Dist. of Wilson County, 433 F.

2d 587 (6th Cir. 1970) .................................................. 34n

South Park Independent School Dist. v. United States,

47 U.S.L.W. 3385 (Dec.. 4, 1978) ................................ 124n

PAGE

IX

Spangler v. Pasadena City Bd. of Educ., 311 F. Sapp.

501 (C.O. Cal. 1970) .......................... ..... ...................... 107

State ex rel. Games v. McCann, 21 Ohio St. 198 (1871) 12n

Swann v. Chariotte-Mecldenburg Bd. of Educe, 402

U.S. 1 (1971) ......... ................. .......... .......... ........... .passim

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 362 F.

Sapp. 1263 (W.D.N.C. 1973), appeal dismissed, 489

F. 2d 966 (4th Cir. 1974), subsequent proceedings,

379 F. Sapp. 1098 (W.D.N.C. 1974) ......................... 154

Taylor v. Board of Educ. of New Rochelle, 191 F.

Sapp. 181 (S.D.N.Y. 1961) ................................. ..... 5n, 107

United States v. Armour & Co., 402 U.S. 673 (1971) „..152n

United States v. Board of School Comm’rs, 332 F.

Sapp. 655 (S.D. Ind. 1971), aff’d 474 F. 2d 81 (7th

Cir. 1973) ................................................ 106,107,108,117n

United States v. Commercial Credit Co., 286 U.S. 63

(1932) ................................................................................ 105

United States v. Crescent Amusement Co., 323 U.S.

173 (1944) ................................... 153n

United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ., 372 F.

2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966), aff’d on rehearing en banc,

380 F. 2d 385 (5th Cir.), cert, denied sub nom. Caddo

Parish School Bd. v. United States, 389 U.S. 840

(1967) .................................................................. ..145n, 149n

United States v. Loew’s, Inc., 371 U.S. 38 (1962) .....153n

United States v. School Dist. No. 151, 286 F. Sapp.

786 (N.D. 111. 1967), aff’d 404 F. 2d 1125 (7th Cir.

1968) ....................................... 107

United States v. School Dist. of Omaha, 565 F. 2d 127

(8th Cir.) (en banc), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1064

(1977) ........... 114n

United States v. Scotland N ed City Bd. of Educ., 407

U.S. 484 (1972) ...................................................100,127,154

PAGE

X

United States v. United Shoe Machinery Corp., 391

U.S. 244 (1968) ........... ............................ ........................ 152

United States v. United States Gypsum Co., 340 U.S.

76 (1950) ........................................................... ............ . 153

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

Dev. Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977) .... ...... 97,109, 111, 112,

113,114n, 115,116,137n

PAGE

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) ....... 97,109, HOn,

111,113,114n,116

West Virginia State Bd. of Educ. v. Barnette, 319 U.S.

624 (1943) ............... ............................. ........................... 147

Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia, 407 U.S.

451 (1972) ........ .......................... 100,127,133,141,149,154

Statutes and Buies:

20 U.S.C. § 1701 ............................................................ -.._117n

42 U.S.C. §§ 3601 et seq...................................... .............. 26n

84 Ohio L. 43 .................................................................... 14n

75 Ohio L. 513 ............................................................. 12

Fed. R. Civ. P. 41(b) ............ ...................... ................... 106

Sup. Ct. Rule 36(2) ................................................ ......... 3n

Sup. Ct. Rule 40(2) .......................................................... 3n

Other Authorities:

American Institute of Public Opinion, T he Gallup

Opinion I ndex (1976) ..... ...........................................146n

C. Black, The Lawfulness of the Segregation Deci

sions, 69 Y ale L.J. 421 (1960) .................................148n

XI

E. Calm, Jurisprudence, 30 N.Y.U.L. Rev. 150 (1955) 148n

A. Campbell and P. Meranto, The Metropolitan Edu

cational Dilemma, in T he M anipulated City (S.

Gale and E. Moore, eds., 1975) ...............................146n

0. Duncan, S ocial Change in a M etropolitan Com

m unity (1973) ............................................................ 146n

J. Egerton, S chool D esegregation: A R eport Card

F rom the South (1976) ...........................................154n

J. Freund, M odern E lementary S tatistics (4th ed.

1973) ........ ..................................................................... 150n

M. Giles, et al., Symposium on S chool D esegregation

and W hite F light (1975) ............... ........ ........ ...... 154n

M. Giles, D. Catlin and E. Cataldo, D eterminants op

R esegregation : Compliance/ R ejection B ehavior

and P olicy A lternatives (National Science Foun

dation, 1976) - ........................................................ 154n

R. Green, Northern School Desegregation: Educa

tional, Legal and Political Issues, in U ses of the

Sociology of E ducation (1974) ................ 146n

S. Kanner, From Denver to Dayton: The Develop

ment of a Theory of Equal Protection Remedies,

72 NW. U. L. Rev. 382 (1978) ........................... .....136n

G. Orfield, I f Wishes Were Houses Then Busing Could

Stop: Demographic Trends and Desegregation

Policy, U rban R eview (Summer, 1978) ................. 154n

G. Orfield, M ust W e B u s? (1978) ................................ 154n

L. Poliak, Racial Discrimination and Judicial In

tegrity: A Reply to Professor Weehsler, 108 U.

Pa. L. R ev. 1 (1960) ............................................... _149n

PAGE

Xll

K. Taeuber, Demographic Perspective on Housing and

School Segregation, 21 W ayne L. B ev. 833 (1975)

146n

United States Comm’n on Civil Bights, B acial I sola

PAGE

tion in the P ublic S chools (1967) .......................154n

K. Vandell and B. Harrison, B acial T ransition in

Neighborhoods (1976) ..... ........... ...................... ...... 146n

M. Weinberg, D esegregation B esearch (1970) ...........146n

J. Wigmore, E vidence (3rd ed. 1940) ......................... 6

I n t h e

(ta r t of % Hutted B u U b

Octobee Term, 1978

No. 78-610

Columbus B oard oe E ducation, et al.,

Petitioners,

V.

Gary L. Penick, et al.

ON W R IT OP CERTIORARI TO T H E U N IT E D STATES COURT

OP A PPEALS POR T H E S IX T H C IR C U IT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

Questions Presented

Respondents do not accept the statement of Questions

Presented as framed by Petitioners, because the assump

tions reflected in the questions are inaccurate, with respect

to the status of the Columbus school system (where “man

datory [i.e., state-imposed] segregation by law has [not]

long since ceased” ), with respect to the evidence (there is

much more in the record than “ evidence of discrete and iso

lated constitutional violations” ), and with respect to the

basis for the rulings below (which were not based solely

on “ legal presumptions” ). However, we forsake the se

mantic exercise of rewording the questions. As Petitioners

have described their claims in their brief, and in light of

the record made at the trial of this matter, the issue to be

2

determined by this Court is : what do plaintiffs in a school

desegregation action need to prove in order to be entitled

to meaningful (usually systemwide) relief1?

Statement of the Case

The prior proceedings in this matter are, by and large,

accurately described at pages 3-7 of Petitioners’ Brief, with

the exception of certain characterizations of the parties

and the actions of the trial court. The most important of

these is Petitioners’ contention that the July 29, 1977 Order

o f the district court (Pet. App. 97) required “ development

of a new systemwide racial balance remedy plan” or “ that

every school in the Columbus system be racially balanced.”

The trial judge did not require racial balance; he did re

ject the plans proposed by the Columbus Board of Educa

tion because “ the Columbus defendants did not shoulder the

burden of showing that the amended plan’s remaining one-

race schools are not the result of present or past discrimi

natory action on their part as required by Swann, supra,

402 U.S. at 26” and because “adequate justification for the

retention of one-race schools must be supplied by the de

fendants. They have not done so.” (Pet. App. 102-03; see

also, id. at 105.)

Additionally, we do not understand why Petitioners re

fer to counsel for Respondents as “ NAACP lawyers”

(Pet. Br. 4, 5). Among counsel for respondents during the

course of proceedings in this matter have been salaried

attorneys employed by several different organizations, in

cluding the NAACP (as well as attorneys in private prac

tice) ; but the NAACP is not a party to the case and the

identification of counsel is without significance.

3

Statement of Facts1

Introduction

In school desegregation matters, as in other constitu

tional cases, the facts are critical to an informed judgment.

Petitioners have confined their recitation of facts (Pet. Br.

7-39) to the specific examples of segregative actions enu

merated in the trial court’s opinion and to other evidence

which Petitioners believe weighs in their favor.2 The mass

of evidence considered by the district judge in reaching the

conclusion that there had been systematic, systemwide se

gregation in the Columbus public schools is hardly ad

1 The form of citations employed throughout this Brief is as fol

lows : The opinions below, reprinted in the Appendix to the Petition

for Writ of Certiorari, are cited “ Pet. A p p .------ That portion of

the testimony and evidence printed in the Appendix is cited “A.

------ .” Because of the volume of the testimony and exhibits in the

trial court, every effort was made to limit the amount of material

designated for inclusion in the printed Appendix, see Sup. Ct.

Rule 36(2). The major portions of plaintiffs’ proof of segregation

by Columbus school authorities have been included in shortened,

excerpted form. Nevertheless, at various places throughout this

Brief it has been necessary to refer to additional evidence in the

record. Where reference is made to oral testimony at the hearings

on liability held between April 19 and June 17, 1976, it is cited

“L. Tr. ------ .” Where reference is made to oral testimony at the

hearings on remedy held in 1977, it is cited “R'. T r .------ .” Exhibits

not reprinted in the Appendix will be identified as introduced at

either the liability or remedy hearings, respectively, through use of

the letters “L” and “R” and will be cited in accordance with Sup.

Ct. Rule 40(2) ; for example, “PI. L. Ex. •—— , L. Tr. ------ .” In

accordance with the request of the Clerk of this Court,, the trial

exhibits were not transmitted as part of the record; however, some

of the most important trial exhibits have been withdrawn from the

district court and lodged with the Clerk of this Court so that they

will be available for inspection if desired. See note 6 infra.

2 On occasion, Petitioners err in their description of the record

evidence or propose inapposite comparison of exhibits which are not

compatible. These misstatements are noted as appropriate in the

course of the factual summary which follows.

4

verted to.3 For this reason, we believe that a full

presentation in our Brief of the record evidence which

supports Bespondents is necessary.

There is an additional ground why complete factual

documentation is indispensable in this instance. Some of

the legal questions posed by Petitioners, we contend, do not

actually arise on this record. Their presence in this case is

traceable to misconceptions about the evidence and to lan

guage used (perhaps too loosely) by the Court of Appeals.

For example, this case does not involve the application of

legal presumptions to proof of only “ isolated” constitu

tional violations (compare Pet. Br. 3). An accurate evalu

ation of the judgments below requires an adequate factual

exposition.

The district court had before it an unprecedented amount

of information about the policies and practices of Colum

bus public school authorities, from formation of the dis

trict in the 1820’s through the date of trial. A significant

portion of the historical pre-1954 evidence was documen

tary— and the documentation was maintained by the school

system’s own historian. (A. 254-55.).4 In addition, wit

3 In some instances Petitioners seem to contest the district court’s

school-specific findings as expressed in the opinion (e.g., Pet. Br.

22-24). Petitioners also contest the overall finding of systemwide

segregation made by the trial court on the basis not only of the

incidents detailed in his opinion but also of the entire record (see

Pet. App. 94-95). Since those findings were explicitly affirmed by

the Court of Appeals (e.g., Pet. App. 172-73, 198-99), debating

the evidence here would seem to be precluded by the “ two-court”

rule. See Berenyi v. Immigration Serv., 385 U.S. 630 (1967). How

ever, because Petitioners’ argument may be construed as a claim

that the findings are “ clearly erroneous” on the part of both courts

below, see Brainard v. Buck, 184 7J.S. 99, 105 (1902), the “ two-

court” rule may not bar their review. But this underscores the

importance of examining the entire record.

4 Petitioners deprecate the testimony of Myron Seifert (Pet. Br.

39, 69 n.35) but they fail to identify him as a school system em

ployee who collected and maintained historical material about the

Columbus school system as part of his official duties (A. 255). Nor

5

nesses testified from personal recollection dating back at

least to 1916 about the school system’s discriminatory prac

tices; this testimony was basically undisputed by Peti

tioners.5

For both legal and factual reasons, the pre-1954 history

of the Columbus public school system is of significance in

this case. First, the district court explicitly found that

. . . the Columbus school system cannot reasonably be

said to have been a racially neutral system on May 17,

1954. The then-existing racial separation was the di

rect result of cognitive acts or omissions of those

school board members and administrators who had

originally intentionally caused and later perpetuated

the racial isolation, in the east area of the district,

of black children and faculty at Champion, Mt. Vernon,

Garfield, Felton and Pilgrim . . . .

. . . As a result, in 1954 there was not a unitary school

system in Columbus. (Pet. App. 11.)

The Court of Appeals upheld this finding (Pet. App. 159-

60). Hence, unless both courts below were wrong, when

have Petitioners ever denied the accuracy of the facts and occur

rences about which he testified, nor presented record evidence to

refute his testimony.

5 Petitioners now characterize this testimony as “ subjective” and

of “little probative value” (Pet. Br. 39) but they never rebutted

it and have never denied that the events took place. See, e.g.,

Taylor v. Board of Educ. of New Rochelle, 191 F. Supp. 181, 184

(S.D.N.Y. 1961). In contrast, after one of plaintiffs’ witnesses

described an incident involving reassignment of his child from one

school to another in 1952, an incident which he interpreted at the

time as demonstrating racial discrimination (L. Tr. 2026-36), Peti

tioners produced class rosters, monthly school enrollment reports,

newspaper clippings, pupil census cards (L. Tr. 4612-33), and a

woman who was employed for less than a single school year in

1952 as a substitute teacher by the Columbus publie school's (L. Tr.

4713-21) in order to demonstrate that this action did not have a

racial purpose or effect.

6

Brown II was decided in 1955, the Columbus board was

cleaily charged with the affirmative duty to take whatever

steps might be necessary to convert to a unitary system in

which racial discrimination would be eliminated root and

branch,” Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430, 437-48 (1968); see also, Keyes v. School Dist.

No. 1, 413 U.S. 189, 203 (1973). Second, the pre-1954 ac

tions are also relevant because many of the devices and

techniques utilized by the Columbus school authorities

prior to Brown to maintain segregation are identical or

similar to actions taken in later years. The pre-1954 vio

lations are thus persuasive evidence of the system’s intent

in implementing decisions after that date which entrenched

or extended pupil and faculty segregation in its schools.

Cf. Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, supra, 413 U.S. at 207,

citing 2 J. Wigmore, E vidence (3rd ed. 1940).

For the period 1957 through 1975, because more of the

official records were extant, the operations of the school

system were examined and analyzed in even greater detail

before the district court. Directories indicating the exact

location of every school attendance boundary and optional

attendance area during those years permitted the prepara

tion of demonstrative exhibits which allowed the trial court

to evaluate visually the impact of pupil assignment devices

used by the system. Maps of the district showing the resi

dential distribution of the white and non-white population

of Columbus in 1950, 1960, and 1970, as recorded by the

U.S. Census, both aided that evaluation and also corrobo

rated the testimony of witnesses about Columbus residen

tial patterns at the time when school zones were established

and modified.6 Beginning with the 1964-65 school year,

6 These demonstrative exhibits, PI. L. Exs. 250-52, L Tr 3897

(base maps), PL L. Exs. 261-320, L. Tr. 3898 (attendance zone

7

both enrollment and faculty and principal assignment data,

by race, were available.

In 36 trial days of hearing on liability, covering more

than 6000 pages of transcript, more than 70 witnesses and

750 exhibits were presented by the parties. Based upon all

of the evidence, the trial court concluded that

the Columbus Public Schools were openly and inten

tionally segregated on the basis of race when Brown I

was decided in 1954. The Court has found that the

Columbus Board of Education never actively set out

to dismantle this dual system. The Court has found

that until legal action was initiated by the Columbus

Area Civil Rights Council, the Columbus Board did

not assign teachers and administrators to Columbus

schools at random, without regard for the racial com

position of the student enrollment at those schools.

The Columbus Board even in recent times, has ap

proved optional attendance zones, discontiguous at

tendance areas and boundary changes which have

maintained and enhanced racial imbalance in the Co

lumbus Public Schools. The Board, even in very recent

times and after promising to do otherwise, has ab

jured workable suggestions for improving the racial

balance of city schools. (Pet. App. 61.)

. . . The evidence in this case and the factual deter

minations made earlier in this opinion support the

finding that those elementary, junior, and senior high

schools in the Columbus school district which pres

ently have a predominantly black student enrollment

have been substantially and directly affected by the

overlays), and PI. L. Bxs. 336-38, L. Tr. 3899 (new construction

overlays) have been lodged with the Clerk of this Court and are

available for the Court’s inspection.

8

intentional acts and omissions of the defendant local

and state school boards. (Pet. App. 73.) (emphasis

added.)7

After this Court’s opinion in Dayton Bd. of Educ. v. Brink-

man., 433 U.S. 406 (1977) was announced, the district court

repeated its findings:

. . . Viewing the Court’s March 8 findings in their

totality, this case does not rest on three specific vio

lations, or eleven, or any other specific number. It

concerns a school hoard which since 1954 has by its

official acts intentionally aggravated, rather than al

leviated, the racial imbalance of the public schools it

administers. These were not the facts of the Dayton

case.

Systemwide liability is the law of this case pending

review by the appellate courts. 429 F. Supp. at 266.

Defendants had ample opportunity at trial to show,

if they could, that the admitted racial imbalance of the

Columbus Public Schools is the result of social dynam

ics or of the acts of others for which defendants owe

no responsibility. This they did not do, 429 F. Supp.

at 260. (Pet. App, 94-95) (emphasis supplied.)

Despite this rather clear statement, Petitioners insist

upon arguing this case as if the conclusions of current,

systemwide impact of their own segregatory actions are

based solely on the examples of such actions set out at

length in the trial court’s opinion, combined with “ legal

presumptions.” They repeatedly refer to “ remote and iso

la te d ” acts of segregation, and attempt to support this

thesis by lifting from its context a single sentence used by

7 The district court’s findings with respect to the State of Ohio

defendants were remanded by the Court of Appeals (Pet. App.

208) and are thus not at issue in this Court.

9

the Court of Appeals in its opinion affirming the district

court’s judgment:

These instances can properly he classified as isolated

in the sense that they do not form any systemwide

pattern. (Pet. App. 175.)

Not only does this language of the Court of Appeals

refer explicitly only to a portion of the evidence before the

district court, compare Pet. App. 166-74, but it is a char

acterization not made by the trial court. As we show be

low, the evidence in this case demonstrates the consistent

adoption of segregative devices by the Columbus school

authorities up to the very eve of trial. The Court of Ap

peals’ statement must be read in light of the record to

mean only that the Columbus school authorities did not

succeed in segregating every black student from every

white student through the segregative pupil assignment

devices discussed under the heading of “ Gerrymandering,

Pupil Options, Discontiguous Pupil Assignment Areas,

Etc.” (Pet. App. 174), especially since the Court of Ap

peals’ opinion goes on to recognize that this evidence was

most significant because it indicated that the board’s selec

tive invocation of the “neighborhood school” concept was

but a pretext for a policy of segregation (Pet. App. 175).

Consideration of all of the evidence may not be neces

sary to interpret the remark in perspective, but meticulous

appraisal of the record is crucial because of the pivotal

significance accorded the Court of Appeals’ language in

Mr. Justice Rehnquist’s stay opinion, Pet. App. 213:

. . . In both cases the Court of Appeals employed

legal presumptions of intent to extrapolate system-

wide violations from what was described in the Colum

bus case as “ isolated” instances, [citation omitted] The

Sixth Circuit is apparently of the opinion that pre

10

sumptions, in combination with such isolated viola

tions, can be used to justify a systemwide remedy

where such a remedy would not be warranted by the

incremental segregative effect of the identified viola

tions. . . .

Even if we are wrong about the meaning of the Sixth Cir

cuit’s sentence in context, this Court must carefully weigh

the trier of fact’s determination in light of the entire rec

ord. For if the evidence supports the judgment which the

Court of Appeals affirmed, then that judgment must be

allowed to stand and the remedial decrees of the trial court

implemented. See Massachusetts Mut. Life Ins. Co. v.

Ludwig, 426 U.S. 479 (1976), and cases cited.

A. Pre-1954 Operation of the Columbus Public Schools.

1. Demography. The Columbus district radiates in all

four directions from the downtown intersection of Broad

and High Streets. The shortest and narrowest of its four

“ arms” lies to the west, across the Scioto River; to the

east, prior to 1950 the district extended around three sides

of the City of Bexley (which it now entirely surrounds).

To the north, it included a wide band of territory on both

sides of the Olentangy R iver; and to the south was a slight

ly narrower and shorter extension. As the district court’s

opinion recites, the Columbus district has significantly in

creased in area since 1950 (Pet. App. 12). In particular,

since that time the district has expanded substantially to

the east, southeast, and northeast. (Compare Fig. 3, PL L.

Ex. 59, L. Tr. 3882, at 7 [1950 Ohio State University

study] with PI. L. Exs. 320, 252, L. Tr. 3897, 3898 [over

lay of 1975 senior high school attendance areas over 1970

census].) The arena of concern during the pre-Brown

years is accordingly the smaller unit. (See also, Fig. 14,

11

PL L. Ex. 58, L. Tr. 3882, at 111 [1939 Ohio State Uni

versity study].)

Prior to 1954 the black population of the city was located

generally in the central and east-central portions of the

district (see, for example, the 1950 census map, PI. L. Ex.

250, L. Tr. 3897). The Columbus Board of Education con

structed its first all-black schools in this area, and the evi

dence of pre-1954 constitutional violations in this case

concerns that area almost exclusively. For the convenience

of the Court in following the summary of that evidence, a

line drawing of the area to the east and north of the

Broad-High intersection is reproduced on page 13.8

2. Early history: compulsory segregation. The evidence

demonstrates that racial segregation of students and teach

ers has been a recurrent theme in public education in Co

lumbus since free schooling was first made available. Prior

to 1848, free blacks were excluded from the public schools

(though they were also exempted from contributing prop

erty taxes used for education) (PI. L. Ex. 351, L. Tr. 3902,

at 3). Thereafter, Ohio mandated separate “ colored”

schools in any district having 20 or more black children

(id.). Following the Civil War, the pattern of segregation

was continued. Black elementary students in Columbus

were assigned to separate schools; a Board of Education

plan to house all Negro students in a facility on Sixth

Street, no matter what their place of residence or the dis

tance they had to travel to get there, provoked opposition

8 This drawing was prepared by tracing from the map at PI. L.

Ex. 376, L. Tr. 3907, at 8, and adding indications of the approxi

mate locations of the American Addition and Eleventh Avenue

School, both to the north. School names are in italics and locations

indicated by heavy dots.

12

from a black leader (A. 256-58; PL L. Ex. 351, L. Tr. 3902,

at 113-14). Compulsory segregation in public education

was upheld against a Fourteenth Amendment challenge by

the Ohio Supreme Court in 18719 (Pet. App. 7-8) and the

state legislature reaffirmed this holding in 1878 when it

adopted a permissive school segregation statute, 75 Ohio

L. 513 (Pet. App. 8).

In the meantime, the Columbus School Board rebuilt a

facility for Negro grade school students (the Loving

School), named for the Board member who had shown

the greatest concern for the education of Negro children

even though he was highly critical of its location and

adequacy (A. 258-59; PI. L. Ex. 351, L. Tr. 3902, at 16;

see also, Dr. Loving’s later report of the building’s defects,

A. 264-66; PI. L. Ex. 351, L. Tr. 3902, at 33).

3. Segregation ended and reinstated. In 1881 the Board

was finally persuaded to close the Loving School (A. 266,

270-71; PI. L. Ex. 351, L. Tr. 3902, at 44-45). For almost

three decades thereafter, the Columbus schools were offi

cially not segregated— although the subject of a return to

the practice of racially separate schools arose repeatedly

(see A. 271-72, PL L. Ex. 351, L. Tr. 3902, at 46, 49-51).

The system also hired a few black teachers during this

time.10

9 State ex rel. Games v. McCann, 21 Ohio St. 198 (1871).

10 Columbus operated not only a twelve-grade elementary and

secondary system, but also a “Normal School” to prepare high

school graduates for teaching careers (see A. 178), but the first

black to complete high school in the city did not receive a diploma

until 1878 (A. 262; PI. L. Ex. 351, L. Tr. 3902, at 26; Pet. App. 8).

Approx, loca- Approx, loca

tion of 11th ^ t ion of Amer-

Avenue School ican Addi t ion

14

By 1907 the Board of Education was again under com

munity pressure to restore school segregation; it requested

an opinion from the City Solicitor concerning the legal

permissibility of such a course (A. 365-67; PI. L. Ex. 351,

L. Tr. 3902, at 58) and was eventually advised that explicit

segregation was invalid under Ohio law11 (L. Tr. 3169-70).

However, the Board decided to purchase a site and con

struct a new facility on Champion Avenue (A. 273-76). This

decision was widely viewed as a means of effectuating

segregation: when first announced, it resulted in presenta

tion of a petition to the school board from Negroes who

feared that this was the Board’s purpose (A. 370-72) ;12 and

it was reported in the press as a “ Clever Scheme to Sepa

rate Races in Columbus Schools” (A. 272-73, 370). By

January, 1910, when construction of the facility was nearly

complete, a newspaper story reported, “Negroes to have

fine new school” staffed entirely with black teachers (A.

276-79, 372).

Despite the protests, the newspaper stories proved ac

curate. The Champion Avenue School was located midway

between two existing facilities (the Twenty-Third Street

[now Mount Vernon Avenue] and Eastwood Avenue

Schools), approximately three blocks from each. (See p.

13 supra.) An attendance area for the school was created

from the former Twenty-Third Street and Eastwood

Avenue zones such that more than 90 percent of the resi-

11 In 1887 the Legislature repealed Ohio’s permissive segregation

statute, 84 Ohio L. 34, and despite its earlier McCann ruling be

fore the statute was enacted, the Ohio Supreme Court ruled that

the repeal made segregation illegal in the state. Board of Educ.

v. State, 45 Ohio St. 555, 16 N.E. 373 (1888) ; see Pet. App. 8.

12 In 1907, the school board’s request for an opinion on segrega

tion from the City Solicitor also produced a protest petition from

the black community, in which it was alleged that “ the boundary

lines of certain school districts in this city [had already so] been

drawn as to segregate colored children . . . ” (A. 367-70).

15

deuces within the zone were occupied by black families,

compared to less than four percent in the new areas for

the other two schools (A. 377-78; L. Tr. 3310-15).13 Black

teachers were reassigned from other schools to Champion

(A. 179-80); in 1916, a black applicant was told that

Champion was the only school in the system at which

Negro teachers would be hired (A. 180; see also id. at 188).

Champion was the only school in Columbus which had a

black principal (L. Tr. 176-77).

4. Extending segregation: grade restructuring, optional

zones, faculty replacement, boundary changes, and gerry

mandering. As the black population in Columbus grew, the

educational authorities embarked upon a series of actions

to maintain a high degree of racial separation in the public

schools. In 1922, the same year that Pilgrim Junior High

School opened, ninth grade students were withdrawn from

23rd Street and added to Champion’s enrollment despite

protests that this would further reduce most Columbus

black children’s opportunity for an integrated educational

experience (A. 378-79; L. Tr. 3324-28). In 1925, as the

black population expanded westward toward the business

center, the Board created the so-called “Downtown Option” .

Students residing within this large area (which included

the zone of the former Spring Street School, which was

integrated in 1921, L. Tr. 136-37) could elect to attend any

13 A black parent brought suit against the Board, challenging

the zone established for Champion as part of a plan to operate a

segregated school in violation of Ohio law. The complaint pointed

out, for example, that the northern boundary of the Champion zone

was an alley immediately adjacent to the site of the 23rd Street

School (A. 373-76). The Board claimed that construction of a new

facility was made necessary because of overcrowding and because

junior high school grades were being established at the 23rd Street

School (see A. 178), which Champion would feed (L. Tr. 3306).

The state Circuit Court dismissed the suit, holding that it had no

authority to interfere with the Board’s administration of the school

system (A. 376-77).

16

of the surrounding schools, which varied widely in their

racial compositions. White students could thus avoid at

tending the closest facilities if they happened to be inte

grated or predominantly black (A. 478-86).14 By 1928,

many black students were attending the Twenty-Third

Street School; it was renamed the Mt. Vernon Avenue

School and its white principal and faculty were replaced

with a principal and staff of black teachers (A. 315).

That same year, the Champion facility was enlarged (L.

Tr. 3349). Attendance areas for Champion and Mt. Vernon

were altered in 1931 with a concomitant reduction in size

of the Eastwood zone. The Champion boundaries were

expanded eastward to Taylor Street and south to Long

Street to add black residences formerly in the Eastwood

zone, and a portion of the Eastwood area south of Long

Street and east of Ohio Avenue was added to Mt. Vernon

School (L. Tr. 3351-57). (See p. 13 supra.) Eastwood’s

enrollment further declined in 1932, when students in sev

eral grades residing in the Eastgate subdivision were

housed in a portable building in that area (A. 383-84).

Then in 1933, the Eastwood facility was shut down entirely.

White students residing in the eastern portion of its former

zone were assigned to a “ school” composed solely of port

able buildings located in the predominantly white Eastgate

subdivision across Woodland Avenue,15 16 while white stu

dents in the western end of its zone (as altered in 1931)

14 The “Downtown Option” was paralleled by an optional atten

dance area, or “neutral zone” , at the junior high school level (L.

Tr. 3345-47).

16 As early as 1925, the Board had created a similar “ portable

school,” this one staffed entirely with black teachers, for black stu

dents living in the “ American Addition” well to the north (see

p. 13 supra), rather than accommodate these children at nearby

Leonard Avenue Elementary. Black junior high school students

living in this area were required to attend Champion rather than

the closer schools with junior high grades—Pilgrim and Eleventh

Avenue. Not until 1937 did the school system provide these stu-

17

were assigned to the predominantly white Fair Elementary

School south of Broad Street (A. 384-86). None of the

white former Eastwood pupils were reassigned to Cham

pion or Mt. Vernon (A. 181). (Cf. L. Tr. 150-51.)16

In 1932 the Garfield Elementary School was converted

from an all-white to an all-black faculty and principal (A.

315). That year also, the Board detached the virtually

all-white Eastgate and Shepard Elementary areas from

the nearby Pilgrim junior high school zone and, despite

vehement protest about segregation (L. Tr. 3936-38), trans

ferred them to the more distant Franklin Junior High, to

the south below Broad Street (A. 380-83). This action re

moved a significant number of white students from Pilgrim

and signaled its expected transformation into a school for

black children. The transformation was completed in 1937

when an all-black faculty was transferred to the Pilgrim

school (A. 184-85). It was made an elementary-level facil

ity, and Champion became a junior high school serving

graduates of the newly created black elementary schools

(Mt. Vernon, Garfield and Pilgrim) (A. 387-89).* 16 17 Franklin

dents with transportation to Champion. (L. Tr. 3334-43.) The

all-black elementary grades in portables remained in the American

Addition until a new Superintendent of Schools arrived after 1949.

He found deplorable conditions and directed that the students be

housed in vacant classrooms at Leonard (A. 574-75).

16 Looking back on this 'sequence of events in 1941, the Vanguard

League_ (an integrated civic group, see A. 194-95; L. Tr. 182)

complained that the low enrollment at Eastwood which was used

to justify its closing -was the result of the 1931 zone changes. The

League recommended that Eastwood be reopened (A. 386-89 • PI

L. Ex. 51H-5(b), L. Tr. 3994.)

17 The 1938 attendance zone maps at Figs. 13-14, pp. 107, 111

of the 1939 Ohio State University facilities study, PI. L. Ex. 58,

L. Tr. 3882, indicate that the zone for Champion Junior High

also included the Felton Elementary area. Although the exact

racial enrollment of Felton at this time is not known, by 1943 it

was a heavily black school and a black principal and staff were ‘

reassigned there (see text infra).

18

Junior High (south of Broad Street), on the other hand,

served the still-white Fair, Douglas, Eastgate, and Shepard

elementary schools although Shepard and Eastgate were

well north of Broad (compare Figs. 13 and 14, PI. L. Ex.

58, L. Tr. 3882, at 107, 111). Both Champion and Pilgrim

were provided with used furniture and hooks (A. 182-84;

L. Tr. 162-63), and black children living in the vicinity of

other elementary schools were assigned to those two

schools (A. 184; note 15 supra). White students living

within their attendance zones, however, were permitted to

enroll in other schools (A. 191).

After Pilgrim was changed to a grade school, the atten

dance zone for Fair Elementary retained the former East-

wood areas reassigned to Fair in 1933, and also extended

far north of Broad Street, very close to Pilgrim—now also

an elementary school (see Fig. 14, PI. L. Ex. 58, L. Tr. 3882,

at 111). It was gerrymandered to exclude black students

from Fair (Pet. App. 9), as vividly described in a 1944

pamphlet of the Vanguard League,18 “Which September ?”

(PI. L. Ex. 376, L. Tr. 3907 at 7 ):

School districts are established in such a manner

that white families living near “ colored” schools will

not be in the “ colored” school district. The area in the

vicinity of Pilgrim school, embracing Richmond, Park-

wood, and parts of Greenway, Clifton, Woodland, and

Granville streets, is an excellent example of such

gerrymandering. A part of Greenway is only one

block from Pilgrim school, however, the children who

live there are in the Fair Avenue school district, twelve

and one half blocks away!

A more striking example of such gerrymandering is

Taylor and Woodland Avenues between Long Street

18 See note 16 supra.

19

and G-reenway. Here we find the school districts skip

ping about as capriciously as a young child at play.

The west side of Taylor Avenue (colored residents) is

in Pilgrim elementary district and Champion Junior

High. The east side of Taylor (white families) is in

Fair Avenue elementary district and Franklin for

Junior High.

Both sides of Woodland Avenue between Long and

Greenway are occupied by white families and are,

therefore, in the Fair Avenue-Franklin district. Both

sides of this same street between 340 and 500 are oc

cupied by colored families and are in the Pilgrim-

Champion, or “colored” school, district. White fami

lies occupy the residences between 500 and 940, and,

as would be expected, the “white” school district of

Shepard-Franklin applies.

In 1943 yet another school (Felton) was officially con

verted into a black school by replacing its entire white

faculty and administrative staff with blacks (A. 195, 313-

15; Pet. App. 9-10). Thus by the end of World War II,

five schools in east Columbus had been created and identi

fied as black schools by Board action. At the same time, a

facility (Eastwood) which would have been integrated, had

it remained open, was closed and its attendance area

divided among black (Mt. Yernon and Champion) and

white (Eastgate portable and Fair) schools. The area of

east Columbus within which the five black schools had

been created and maintained was hardly insubstantial; in

1950 it included the major share of black residences in the

city (see PI. L. Ex. 250, L. Tr. 3897).

Yet desegregation of these schools within the constraints

of the operational practices of the Columbus school system

was possible at all times. By drawing zone lines on a

20

north-south basis across Broad Street prior to 1954— as

the school board was whiling to do when Eastwood was

closed in 1933, in order to provide white students living

east of Woodland Avenue with an alternative to predom

inantly black Champion or Pilgrim—desegregated student

bodies at all of the schools in the area could have been

achieved and maintained. Particularly if the same tech

niques utilized to preserve segregation had been employed

to avoid it (conscious shaping of attendance boundaries

and transportation of pupils, as was done in the case of

the American Addition pupils), a stable situation in which

the existence of racially isolated white and black schools

would not have provided an incentive for residential re

location (compare A. 240-41) could have been created.

Certainly there was no educational impediment to such

possibilities. For the school system’s willingness to have

children living in the “Downtown Option” area— or in the

American Addition—travel long distances to reach their

classes19 refutes any possible claim that desegregation was

infeasible prior to 1954. Furthermore, as suburban areas

were annexed to Columbus in the decades following Brown,

school authorities more and more frequently made use of

pupil transportation (busing) to get pupils to school fa

cilities.20 However, pupil transportation was eschewed when

it would have resulted in desegregation.21

19 This is graphically apparent on the overlay of the 1957-58 ele

mentary school zones, Pl. L. Ex. 261, L. Tr. 3898.

20 See, for example, the Willis Park Elementary zone in 1958-59,

PI. L. Ex. 262, L. Tr. 3898. By the time of trial, the system trans

ported more than 9,000 pupils daily exclusive of transfers under

its voluntary desegregation program (A. 233-34). See also, A. 229-

31, 400.

21 Prom 1956-75, Columbus did transport classes from crowded

schools to those with space available (A. 401-02). In many in

stances, white pupils were bused from one white school to another

white school, and black pupils from one black school to another,

21

Throughout the period, black faculty were assigned in

rigidly segregated fashion, only to schools with black

students (A. 188-89). There were no black principals of

predominantly white schools or white principals of pre

dominantly black schools (A. 402-06; L. Tr. 176-78; Pet.

App. 10). When a new Superintendent of Schools arrived

on the scene in 1949, he found systemwide faculty segre

gation (A. 573-74). Racial designations appeared on sub

stitute teacher assignment cards (A. 225-26; PI. L. Exs.

494B, 494C, L. Tr. 3921) and on enrollment reports sub

mitted by teachers (A. 685-87) and black substitute teachers

were assigned only to schools with black students (A.

187-88; L. Tr. 168-70).

In sum, when Brown I was decided, the Columbus school

system was riven with segregation. In the preceding 45

years the Board of Education disregarded complaints that

its actions were discriminatory and segregative. Tak

ing advantage of grade structure alterations, population

growth, and other systemwide patterns, it had utilized

construction, transportation, school closings, boundary

changes, grade restructuring, faculty and administrative

staff assignments to designate schools as intended for

despite the availability of receiving schools which were not similarly

racially identifiable (L. Tr. 3601-3620). At other times, this sort

of transportation had no racial consequences or could have had an

integrative effect (L. Tr. 5339-78). However, when black students

were sent to predominantly white schools, they were moved with

their teacher in class groupings, remained on the rolls of the send

ing school, and did not participate in academic activities with the

students at the receiving schools (A. 612-13). Sometimes they were

separated for recess and other functions as well (A. 701-14). The

Columbus system was insensitive to the humiliating connotation of

keeping black students confined to a separate classroom with a black

teacher in an otherwise predominantly white facility (A. 400).

Prom 1969-70 until 1973-74, for example, classes from Sullivant

(61% to 70% black) were transported on an intact basis to Bellows

(4% to 9.5% black) rather than adjusting the boundary, pairing

the schools, etc. (A. 639-40).

2 2

only black or white students. White students living in

east-central Columbus were “ protected” from having to

attend school with black children through precise gerry

mandering and optional zone techniques. The stigma of

black undesirability was reinforced by overcrowding and

inferior materials, equipment and facilities at black schools,

and by the absence of black administrators anywhere in

the system except at black schools. As the district court

aptly put it, . . the Columbus school system cannot

reasonably be said to have been a racially neutral system

on May 17, 1954” (Pet. App. 11).

B. Post-B row n Administration of the Schools.

Even after this Court announced that compelled segre

gation of the public schools was unconstitutional, Brown

v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), Columbus

school authorities continued to employ a wide variety of

techniques to maintain significant, if not total, separation

of the races in its public schools. Because the enrollment

of the system grew sizably both as a result of the post-

World War II “baby boom” and also as the geographic

size of the district more than tripled through annexation

of adjacent territory, the school plant consistently grew

as well. The combination of residential relocation within

the pre-1954 area of the district and settlement of the

suburbs meant that numerous boundary adjustments,

school site and construction decisions, grade structure

modifications, and staff-faculty assignments had to be made

each year. The result was a high degree of school segre

gation (see PI. L. Exs. 461A-461D, L. Tr. 2135-36; A. 775-

87, L. Tr. 3909 [PX 383] ; PL L. Exs. 409A-409D, 448A-

448D, 450A-450D, L. Tr. 3910, 3911), which defendants

ascribed solely to their pursuit of “neighborhood schools.”

Plaintiffs sought to demonstrate, to the contrary, that the

only consistent policy of the school system was one lead

23

ing to increased segregation; that the Board used an ever-

changing concept of “neighborhood schools” to entrench

that segregation; and that every manner of exception to

“neighborhood schools” was tolerated in the interest of

segregation. The district court found “that the evidence

clearly and convincingly weighs in favor of the plaintiffs”

(Pet. App. 2).

1. Demography. BetwTeen 1954 and the present, the

Columbus school district has expanded along all four geo

graphic axes. Although there has been a nearly contin

uous series of annexations of small parcels of territory,

several major additions can be identified which account

for much of the total growth of the system. Annexations

from 1954 to 1955 included the airport, two small par

cels to the south, and a large tract to the south of the

City of Whitehall.22 None was densely settled at the time.23

By 1959, additional areas to the far north, around the

airport, immediately south of Columbus, to the east and

south of Whitehall, and at the edge of the district’s western

projection across the Scioto River, had been added, in

creasing its size by more than half.24 25 In a small annexed

area to the northeast, the Columbus district purchased

a site, constructed a building, and opened a new elementary

school (Arlington Park) in 1957.2B The major acquisition

was in 1957, involving a large section to the south of the

district and including several school buildings previously

operated by Marion-Pranklin Township.26 See Fig. 1, PI.

L. Ex. 62, L. Tr. 3882, at 7.

22 See Fig. 1, PI. L. Ex. 61, L. Tr. 3882, at 7.

23 Id. at 2, 5.

24 PI. L. Ex. 62, L. Tr. 3882, at 5.

25 Id. at 48.

26 Id.

24

Few significant additions took place between 1959 and

1964, except for an area north of McKinley Avenue along

the northern edge of the city’ projection toward the west.27

The same situation prevailed in 1969; a substantial amount

of territory to the west, north and northeast had been an

nexed by the City of Columbus but not added to the school

district.28 The major subsequent growth was to the north

east, in 1971. Compare, e.g. PI. L. Exs. 312, 320, L. Tr.

3898 [overlays of senior high school zones in 1967-68,

1975-76].

The same period of time witnessed school-age population

increases both within the “ old” district and in the annexed

areas. To serve this burgeoning school enrollment, Colum

bus undertook an ambitious school construction program.29

Between 1950 and 1975, a total of 103 new schools was

built (Pet. App. 21). Not all of these were to serve either

the annexed territory or areas of residential population

increase; the number includes reconstructions of schools

on the same site {e.g., Garfield and Franklinton) and re

placements of portables with a permanent facility {e.g.,

Fairmoor and Eastgate). Finally, the district made exten

sive renovations and building additions at almost every

school in the system during this period {see PI. L. Exs.

22, 23, L. Tr. 3881, 3991). For new facilities, attendance

27 Compare Pig. 1, PL L. Ex. 64, L. Tr. 3882, at 8 with Pig. 1,

PI. L. Ex. 62, L. Tr. 3882, at 7.

28 Compare id. with Pig. 1, PI. L. Ex. 63, L. Tr. 3882, at 13.

29 Columbus also consistently altered the capacities of its existing

facilities to reflect changing policy objectives chosen by the Super

intendent or the board. For example, the policy decisions to create

and site remedial classes, or to reduce pupil-teacher ratios, had

implications for building capacities. The choice and timing of such

decisions was almost always within the control of school officials,

who could opt to proceed integratively or segregatively. The deci

sion to site special programs at a particular school, for example,

was simultaneously a decision not to use that school’s space to re

lieve overcrowding at another, opposite-race, school.

25

zones had to be established and existing zones modified

(see A. 631, 398). As many as sixty boundary changes a

year were recommended to the school board for approval

(A. 242, 577; see A. 234-37). The exact location of the

building and the pupil capacity for which it is designed

limit the zone-drawing opportunities (along with admin

istrative decisions about pupil transportation) (A. 322-23,

643-44). Hence, Columbus’ multifaceted building program

between 1950 and 1975 presented the school board with

more than a thousand instances in which decisions would

have an impact on the racial composition of school en

rollments.30

At the same time, shifts in the residential location of

Columbus blacks were occurring, in patterns which were

apparent and well delineated. Between 1950 and 1960, for

example, the black population settled in substantial num

bers to the south of Broad Street in the east-central por

tion of the city which was the locus of most pre-Broivn

segregation. (Compare PI. L. Ex. 251, L. Tr. 3897, with

PI. L. Ex. 252, L. Tr. 3897.)31 By 1960, blacks predom

30 This is not a case in which the school board has suggested by

way of defense that it attempted to avoid segregation but was un

done by population shifts which it had been unable to anticipate.

The school system’s employees who had responsibility for the estab

lishment and alteration of recommended attendance zone boundaries

testified that they had never sought to avoid segregation or racial

imbalance (e . g A . 406; cf. A. 577, 598-99 [Ohio State study teams

never instructed to consider race]). Even after the school board

in 1967 adopted a formal policy of considering racial balance when

drawing attendance zones (Pet. App. 16; see A. 684-85), the policy

was disregarded when it might otherwise have feasibly been ap

plied to schools already in existence or previously planned (A. 361,

606).

31 The census maps for 1950, 1960 and 1970 were based on block

data, which results in a more accurate representation of population

movement than use of figures aggregated into larger census tracts

(A. 192). Census “ blocks” are not, however, identical to city blocks

and where land is devoted to institutional use or density is sparse,

census “blocks” may be as large as tracts (L. Tr. 281-83).

26

inated in the area of the Eastgate school established in

1933 and were a substantial, but not majority proportion,

of the residents in the Shepard zone (id.).

The black population also moved northeast toward the

Linden area. Where there had been comparatively few

blacks living north of 5th Avenue in 1950 (see PI. L. Ex.

250, L. Tr. 3897), by 1960 there were substantial numbers

south of 17th Avenue—especially east of the Pennsylvania

Railroad lines (see PI. L. Ex. 251, L. Tr. 3897). At least

prior to the passage of the Fair Housing Act of 196832

(and in reality for most if not all of the period there

after), widespread racial discrimination limited and chan

neled the residential mobility of Columbus blacks. Realtors

could describe with precision what areas or streets were

“ approved” for Negro residence at any given time (A.

244-46; L. Tr. 1504-21, 2148-56; cf. L. Tr. 1298-1305). The

minority population also increased in the areas immedi

ately adjacent to small Negro settlements which had

existed in 1950 in the middle of the district’s western

projection, and to what was the extreme south of the dis

trict prior to the 1957 annexation from Marion-Franklin

Township (see PI. L. Exs. 250, 251, L. Tr. 3897).

These trends continued and accelerated in the 1960’s

(see PI. L. Ex. 252, L. Tr. 3897 [1970 census]; L. Tr. 288).

Thus, not only the activity in the area east and north of

the High-Broad intersection, but also most of the other

school construction and zoning decisions made by the

school board had a direct and immediate impact on the

minority composition of the Columbus public schools. As

the district court found (Pet. App. 25):

This opportunity [to bring about integration rather

than segregation through school construction and

82 42 U.S.C. §§3601 et seq.; see also, Jones v. Alfred E. Mayer

Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968).

27

zoning without pupil transportation] existed, and con

tinues to exist in those areas of the city where the

population shifts from one race to another. An ex

amination of the census maps for the years 1950, 1960

and 1970 discloses a general pattern of high density

(50 to 100%) black population in the center of the

city fringed by areas of lesser, but still substantial

(10% to 50%), black population. The remainder of

the city is predominantly white, although there are

pockets of white population within the central city

area, and pockets of black population in the outlying

areas.

Unfortunately, these opportunities to avoid segregation

were not seized. Instead, the consistent result of school

board policy and action since 1954 has, with rare excep

tion, been to keep blacks in black schools where they are

located in established areas of black residence, and to pro

tect whites from attending schools with substantial black

student populations for as long as possible in areas into

which blacks were moving.33 Despite the growth of the

system in absolute terms and the redistribution of white

and minority population, there has been little change in

the patterns of school segregation (PI. L. Exs. 458, 460,

L. Tr. 2135-36).34

33 This was the pattern of school hoard actions in the Park Hill

area held segregative in Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, 303

F. Snpp. 279, 289 (D. Colo'. 1969), aff’d 445 F.2d 990 (10th Cir.

1971), vacated and remanded on other grounds, 413 U.S. 189

(1973); see 413 U.S. at 199 n. 10 and accompanying text. See also,

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717, 725-26, 738 n. 18, 745 (1974).

34 These exhibits indicate that in 1964, 36.3% of Columbus’ black

student enrollment was in schools over 90% black, and in 1975,

the corresponding figure was 30.2%. At the elementary grade level,

the percentage of black students in schools at least 90% black in

1964 was 38.1%; in 1975-76 it had declined only to 34.6%. Seg

regation actually increased during the middle of that time span;

2 8

2. Post-Brown actions leading to segregation. In his

opinion on liability, the district judge remarked that

[t]he complexity and the sheer volume of the evi

dence presented in this case have delayed this opinion

long past the point at which the Court would have

preferred to have rendered a decision.

(Pet. App. 2.) Based upon his extensive and thorough

review of that evidence, as noted above (pp. 7-8 supra) the

district court found system-wide intentional segregation

having pervasive current effects. Because the district

court’s opinion elaborates only upon examples of post-1954

discrimination by the school authorities, rather than

setting out every act at every school (e.g., Pet. App. 21,

29, 61; cf. Pet. App. 94),85 this case has been portrayed

as one involving only isolated segregative acts. (E.g., Pet.

Br. 19, 22). See discussion, pp. 3-10 supra. In the factual

summary which follows, we attempt to sketch the over

whelming nature and broad compass of the evidence which

supports the trial judge’s ultimate findings.36 In the dis- * 86

in 1970-71 51.7% of black elementary pupils and 45% of all black

pupils were in virtually all-black schools. PI. L. Ex. 459, L. Tr.

2135-36.

86 See Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, supra, 413 U.S. at 200.

86 The evidence may be placed in three categories according to

its treatment by the district court. First, certain evidence was fully

described in the trial judge’s opinion, such as that involving the

pattern's of faculty and principal-assistant principal assignments.

(See Pet. App. 14-15, 60-61). Second, a large body of evidence

was not summarized in detail in the opinion; but instead, repre

sentative examples were set out. (See Pet. App. 20-42.) This evi

dence included not only other examples of those segregative devices

appearing in the internal headings of the court’s opinion (school

construction, optional attendance areas and boundary changes, dis