Partial Memorandum in Support of Intervenors Motion for Payment of Fees and Expenses

Public Court Documents

April 24, 1995

16 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Partial Memorandum in Support of Intervenors Motion for Payment of Fees and Expenses, 1995. 3c3ba4ec-a246-f011-877a-0022482c18b0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0a347264-377b-44f9-a7f5-31c9950f2741/partial-memorandum-in-support-of-intervenors-motion-for-payment-of-fees-and-expenses. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

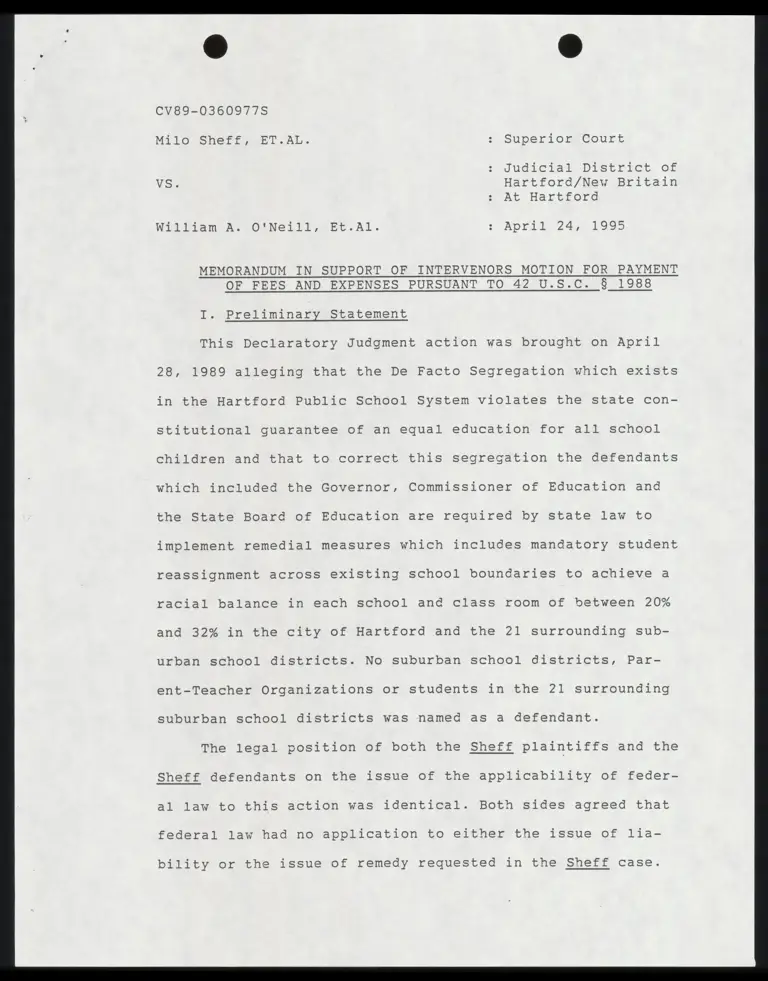

Cv89-0360977S

Milo Sheff, ET.AL. : Superior Court

: Judicial District of

VS. Hartford/New Britain

: At Hartford

William A. O'Neill, Et.Al. : April 24, 1995

MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF INTERVENORS MOTION FOR PAYMENT

OF FEES AND EXPENSES PURSUANT TO 42 U.S.C. 8 1988

I. Preliminary Statement

This Declaratory Judgment action was brought on April

28, 1989 alleging that the De Facto Segregation which exists

in the Hartford Public School System violates the state con-

stitutional guarantee of an equal education for all school

children and that to correct this segregation the defendants

which included the Governor, Commissioner of Education and

the State Board of Education are required by state law to

implement remedial measures which includes mandatory student

reassignment across existing school boundaries to achieve a

racial balance in each school and class room of between 20%

and 32% in the city of Hartford and the 21 surrounding sub-

urban school districts. No suburban school districts, Par-

ent-Teacher Organizations or students in the 21 surrounding

suburban school districts was named as a defendant.

The legal position of both the Sheff plaintiffs and the

Sheff defendants on the issue of the applicability of feder-

al law to this action was identical. Both sides agreed that

federal law had no application to either the issue of lia-

bility or the issue of remedy requested in the Sheff case.

2

See Intervenors' Exhibit (hereinafter I.Ex.) 2, Answer at

Fourth Special Defense (Any right to education which the

[Intervenors] might have is a right guaranteed by state law,

not federal law. The questions raised by the [Intervenors] are,

at best, matters of state law.) and I.Ex. 5, Memorandum Op-

posing Motion to Intervene at 2 (The proposed intervenors

make only federal claims, which is not what the [Sheff] case

is about.)

The legal position of the Intervenors was egually clear

that since the suburban school districts are independent

school districts as that term is defined in Lee v. Lee Coun-

Ly Board of Educ., 639 F.24 1243, 1256 (5th Cir.. 1981), with

regard to remedy only, any attempt by this court to remedy

"societal discrimination" as that term is used by Mrs. Just-

ice O'Connor in Wygant v. Jackson Board of Educ., 476 U.S.

267, 288 (1985)(0'Connor, J., concurring in part and concur-

ring in judgment) by attempting to remove suburban school

children from their local school districts and assigning

them to other school districts on the basis of race for the

purpose of racial balancing would violate the federal con-

stitutional rights of the suburban parents and school child-

ren under Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954) (Brown

I) and Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1973)(Milliken I).

The Intervenors had one purpose and one purpose only, to

prevent the imposition of a remedial plan which would vio-

late the federal constitutional rights of the suburban par-

ents and school children in the suburban school districts.

3

On April 12, 1995, this court issued it's opinion in

the Sheff case. That opinion which was a complete vindica-

tion of the legal positions offered by the Intervenors and

which can fairly be said to have shocked both the plaintiffs

and defendants in Sheff, forms the basis for this Motion for

Payment of Fees and Expenses under 42 U.S.C. § 1988.

II. The Legal Justification for the Award of Fees & Expenses

Although § 1988 is a federal statute designed to shift

fees in favor of those who vindicate federal civil rights,

there can be no doubt that where, as here, those federal

civil rights are vindicated in a state court forum, § 1988

provides for the payment of attorneys' fees and expenses at

the direction of the state court. Maine v. Thiboutot, 448

U.S. 1, 11 (1980). As the Second Circuit noted in Wilder v.

Bernstein, 965 F.2d 1196 (2nd Cir.), cert. denied, U.S. ’

113 S.Ct. 410 (1992), "Although the statute expressly condi-

tions the award of attorneys' fees upon the discretion of

the court, the effect of this language has been interpreted

to create a strong preference in favor of the prevailing

party's right to fee shifting. Therefore, '[a] party seeking

to enforce the rights protected by the statutes covered by

[§ 1988], if successful, should ordinarily recover an attor-

neys' fee unless special circumstances would render such an

avard unjust." (citations omitted) Id4., at 1201 - 02. Under

federal law, there can be absolutely no doubt that Inter-

venors can recover attorneys' fees where they qualify as

prevailing parties. Wilder v. Bernstein, supra., 965 F.2d at

A

1202; United States v. Board of Education of Waterbury, 605

F.2d 573,876. -"77 {2nd ‘Cir. 197%}.

This application is essentially the same as the one

filed in United States v. Board of Education of Waterbury,

supra. In that case an action was filed by the U.S. Attorney

General alleging racial discrimination in the public schools

of Waterbury. The defendant Board of Education entered into

a consent decree which called for school desegregation

thereby ending the liability aspect of the case and the par-

ties began to draft various remedial proposals. The govern-

ment submitted a proposal, Plan H, which called for the bus-

ing of 65% of the Hispanic students but only 5% of the white

students to achieve integration. A group called The South

End Education Committee, an organization of Puerto Rican

parents and community leaders along with several individuals

was allowed to intervene in the case, "[fl]or the limited

purpose of protecting the interests of the Hispanic commu-

nity and participating in the development of remedial meas-

ures under the consent decree." Id., at 574. Upon motion of

the Intervenors, the court rejected Plan H and subsequently

adopted Plan C upon finding, "[t]hat the plan 'would effect

desegregation without disproportionately burdening any rac-

jal group'." Id., at 575. The Intervenors then filed a mot-

ioin for attorneys' fees and costs under § 718 of the Emer-

gency School Aid Act of 1972, 20 U.S.C. § 1617. The district

court denied the motion because, "[i]ntervenors were not a

‘prevailing party' because they had not prevailed on the

‘merits’ of the lawsuit ."wId.,.at 575.

5

This ruling by the district court was reversed by the

Court of Appeals. As the Circuit Court reasoned:

In concluding that intervenors were not a 'prevail-

ing party' the district court rested its decision on

the grounds that they were not a party when the consent

decree was entered, that "in no area of the merits of

the lawsuit did [they] prevail or succeed" and that

while they were instrumental in opposing defendants’

plans, the plan ultimately adopted was not theirs.

Intervenors entered this lawsuit to oppose a plan

which unfairly burdened their constitutuency, and which

was not being opposed by the government. In this they

succeeded. They contested several later proposals, and

worked in support of a plan which better served their

valid interests...In light of the success of inter-

venors in these respects, we conclude that they come

within the meaning of the term "prevailing party". Id.,

at 576 - 77.

The Intervenors in this case stand in the same position

as the intervenors in the Waterbury case. Although the Sheff

defendants contested liability, in this non-bifurcated pro-

ceeding, they did not oppose the imposition of an interdis-

trict remedial plan impacting the independent suburban

school districts if the court found in favor of the plain-

tiffs on the liability issue. The Intervenors herein did not

wish to be heard on the issue of liability, their sole pur-

pose was to "oppos2 a plan which unfairly burdened their

constituency, and which was not being opposed by the govern-

ment".

Although the application in Waterbury was pursuant to

a specific educational statute authorizing payment of attor-

neys fees and expenses, in light of the Second Circuits' dec-

ision in Wilder v. Bernstein, supra., there can be no doubt

that Intervenors such as these qualify for payment of attor-

6

neys fees and expenses under 42 U.S.C. § 1988. Wilder invol-

ved placement of children in child care facilities. The

original parties to the action, the plaintiff Protestant

Black children in need of care outside their homes, and the

original defendants, City of New York and municipal offic-

ials responsible for the City's child care system, began

to negotiate a settlement and a formal proposal was drafted.

At this point certain child care agencies who were not part

of the action interposed objections to the proposed settle-

ment. The Circuit Court's discussion of the precise status

of the intervenors in Wilder is important in the context of

this case. As the Circuit Court noted in its decision:

We digress for a moment to discuss how leave to inter-

vene came about. Although no petition for intervention

was filed, letters, memoranda and affidavits objecting to

the stipulation were submitted prior to the date inter-

vention was ordered. The customery terms of either

"plaintiff-intervenor" or "defendant-intervenor" were not

used to refer to the intervenors. Nor does the district

court's order set forth on what grounds and under which

section of Fed.Civ.P. Rule 24 they were permitted entry

into the action...The district court considered the

intervenors "non-parties vis-a-vis the underlying consti-

tutional claims in the lawsuit" and, despite their con-

stitutional objections, stated the intervenors joined the

lawsuit for the "sole purpose of objecting to the Stipu-

lation on clinical grounds. 965 F.2d at 1199 - 1200.

Despite their "non-party" status, because their compre-

hensive objections had a significant impact upon the creat-

jon of the ultimate remedy, the district court held that the

intervenors were therefore prevailing parties entitled to an

award of attorneys' fees and costs. Id., at 1201. In affirm-

ing, the Circuit Court after ruling that a party may prevail

when it vindicates rights regardless of whether there is a

formal judgment, reasoned:

7

Actions alleging civil rights violations tradition-

ally seek injunctive relief directly affecting not only

the plaintiffs, but also certain non-participants anc

less directly the public at large. In addition to per-

mitting non-participants to protect their implicated in-

terests, intervention furthers the goals of efficiency

and uniformity. To forbid the shifting of attorneys' fees

to intervenors, who could otherwise bring a separate act-

ion later as plaintiffs alleging the same civil rights

violations...defeats the goal of judicial economy. Hence,

there is no reason why the present intervenors, whether

they be styled intervenor-plaintiffs or intervenor-defen-

‘dants, may not be prevailing parties for purposes of

$1988, 1d4., at 1202.

The Circuit Court then noted, "Waterbury presents ana-

logous facts instructive on the resolution of the present

cage". 14., at 1204.

The activities of the Intervenors fall squarely within

the Wilder rationale. The Sheff plaintiffs were seeking in-

junctive relief. See Plaintiffs' Post Trial Brief dated

April 19, 1993 at 108-09. The Remedial Plan offered by the

plaintiffs would clearly impact the non-participating subur-

ban school districts. 14. at 109-20. This remedial plan was

not being opposed by the government. In fact, the defendant

state officials testified in favor of the remedial plans be-

ing put forward by the Sheff plaintiffs. See Plaintiffs’

Reply Brief dated August 16, 1993 at 51 (Defendants Ferandi-

no and Tirozzi both support controlled choice plans.) The

Intervenors could have allowed the Sheff proceedings to come

to a conclusion and result in an interdistrict plan includ-

ing state imposed racial balancing in the independent school

districts and then have gone to federal court. Instead, in

keeping with Wilder, they filed their federal action before

this case reached its conclusion anc, after the federal

8

court refused to dismiss on the merits and denied the decla-

ratory judgment motion without prejudice to renewal after

this court rendered its decision, they intervened here

to advise this court that its decision was subject to colla-

teral attack in federal court and presented the reasons why

granting the remedy requested by the Sheff plaintiffs would

violate the Intervenors federal constitutional rights.

The fact that after arguing their Motion to Intervene on

December 14, 1993, the Intervenors voluntarily withdrew the

Motion has no impact at all on this Motion for Fees. In

Wilder, there was no clear discussion of who the intervenors

were since there had been no motion to intervene and the

district court described them as "non-parties", nevertheless

both the district court and the circuit court ruled that

they were the prevailing parties for the purposes of § 1988.

Similarly, in cases such as Assoc. Builders & Contractors of

La., Inc. v. Orleans Parish School Board, 919 F.2d 373 (5th

Cir. 1990)(case dismissed as moot); Luethje v. Paevine School

District of Adair County, 872 F.2d 352 (10th Cir. 1989)(vol-

untary dismissal of the action); and Thomas v. Board of

Trustees of Regional Comm. Colleges, 599 F.Supp. 331 (D.Conn

1984) (voluntary dismissal of action), the courts have award-

ed attorneys' fees and costs to the plaintiffs even where

the action had been withdrawn or dismissed prior to any for-

mal judgment based upon the finding by the court that the

plaintiffs had been the prevailing party. As Judge Dorsey

stated in Thomas, "A plaintiff will be considered a 'pre-

9

vailing party' entitled to such fees if the plaintiff has

succeeded "'on any significant issue in litigation which

achieves some of the benefit the part[y] sought in bringing

the suit'"...[d]etermination as to whether or not a party

has "prevailed" has been subjected to a two fold test:First,

‘the plaintiffs] lawsuit must be causually linked to the

achievement of the relief obtained', and second, 'the defen-

dant must not have acted gratuitously, i.e. the plaintiff[s]

claim[], if pressed, cannot have been frivolous, unreason-

able, or groundless."(citations omitted) Id. at 334.

III. The Intervenors were the "Prevailing Party".

This court would be haré pressed to deny the impact of

the actions and the legal arguments raised by the Interven-

ors in the federal action and their Motion to Intervene

which was clearly predicated upon the federal action. The

legal issues they raised for the first time in both the fed-

eral action and the Motion to Intervene are clearly reflect-

ed in the subsequent statements and decision of this court

in Sheff.

1) The Sheff Parties as "Friendly Adversaries".

The very first argument made by the Intervenors in the

federal Memorandum in Support of Motion for Declaratory

Judgment was that Sheff was not an adversary proceeding. The

parties in this case, both plaintiffs and defendants, were

acting as "Friendly Adversaries" as that term was used by

Mr. Justice Kennedy in Missouri v. Jenkins, 495 U.S. 33, 59

(1989) (Kennedy, J., concurring in part and concurring in

10

judgment). Essentially, the Friendly Adversaries in Sheff

agreed among themselves as to what had to be done, however,

they needed to harness the power of this court to overcome

the resistance of the general assembly and the public. See,

I.Ex. 7 at 10-15. The impact of this argument upon this case

is undeniable. At the December 16, 1993 aborted first final

arguments which occurred two days after the Intervenors Mot-

ion to Intervene was argued and copies of the federal briefs

and decision was presented to the court, this court engaged

Attorney Horton in an extended discussion of the lack of ad-

verseness in this action. This court itself noted that de-

fendant Tirozzi had been the plaintiffs' best witness and

that there was no dispute between the plaintiffs and the

defendants. The real dispute lay between the parties in

Sheff and the general assembly. The court, to its credit,

then tried to inject adversity into this case by joining the

general assembly offering to order them into the case that

very day. The Friendly Adversaries, however, would have none

of this adverseness business and convinced the court that

joinder of the general assembly was not feasible. Neverthe-

less, the court was painfully aware that there was a poten-

tial constitutional taint on this record, one which the non-

party suburban school districts would raise in defense to

imposition of any interdistrict remedy.

2) The Feasibility of a Collateral Challenge.

The purpose of the Intervenors in going to federal

court first was two fold. First and foremost, they wanted to

11

demonstrate in the clearest possible terms that in the wake

of the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Martin Vv. Wilks, 490

U.S. 755 (1989), the service of notice of this action upon

the suburban school districts and their subsequent failure

to intervene to protect their rights in this case would not

preclude a subsequent collateral attack upon this court's

judgment and remedy. Prior to the Motion to Intervene, the

working procedural hypothesis of the court and the Friendly

Adversaries was that the failure of the suburban school sys-

tems to intervene constituted a waiver of any rights they

might have had to collaterally challenge this court's ruling

even if it impacted their rights. This in fact was the pre-

Wilks rule in the Second Circuit. The Wilks decision, how-

ever, completely vitiated this legal position. This concern

with a successful collateral attack is clearly reflected in

the court's comments in subsequent proceedings. During the

September 22, 1994 status conference, the court expressed

concern over whether the Hartford school district should be

joined as a party defendant. During the September 28, 1994

status conference, the court clearly expressed a desire not

to reopen completed portions of the 5 year old file, never-

theless, it was concerned over having its ruling overturned

for procedural reasons and inquired again as to the adequacy

of the notice sent to the 22 school districts involved even

to the point of suggesting a new round of legal notices. And

at the final arguments on November 30, 1994, the court spe-

cifically noted for the record the federal action and that

12

the court and the parties agreed that the issues raised in

that action would be dealt with at a later date. Clearly,

the Intervenors interpretation and use of Wilks to open the

door for a subsequent collateral attack became a principal

concern when this court considered remedies which directly

impacted the non-party school districts.

3) The Predominance of Federal Constitutional Issues.

One of the principal issues raised by the Intervenors

in the federal case and which became part of the Motion to

Intervene was the fact that the 14th Amendment of the U.S.

Constitution preempts the entire area of state action and

race. In their legal memorandum, I.Ex. 7 at 15 - 21, the

Intervenors clearly argue that the issue of whether or not

societal discrimination violates the state constitution is

irrelevant to the authority of this court to redress socie-

tal discrimination under the 14th Amendment. Even assuming

arguendo that societal discrimination violated the state

constitution, in the absence of de jure discrimination link-

ed to the state, this court as a state actor is powerless to

redress it. The Friendly Adversaries, on the other hand,

both argued that there were no federal constitutional issues

raised by the Sheff claims or remedies.

On April 12,:1995, this court issued its decision in

the Sheff case. The operative portion of that decision com-

mences on page 60 and continues through the conclusion on

page 72. In this section, the court focused exclusively on

federal decisional law under the Equal Protection Clause of

13

the federal constitution. In this section, the court focused

upon the Supreme Court opinions which were most favorable to

the plaintiffs positions, those of Mr. Justice Douglas. Even

Mr. Justice Douglas, whose opinions attempt to equate de

jure and de facto segregation, recognized the limits of per-

missible state action where the state had not contributed to

the dual system. As the court noted at page 67:

Justice Douglas [in Gompers v. Chase] then raised

what he referred to as "another troublesome question",

namely, the remedy that should be provided under equal

protection analysis where the state is found not to be

"implicated in the actual creation of the dual system."

He answered his own question by stating that the only

constitutionally appropriate "solution" in a situation

where minority schools are not qualitatively equal to

white schools would be to design "a system whereby the

educational inequalities are shared by the several

races." (emphasis added) (citations omitted)

The court then goes on to find that the Sheff plain-

tiffs had not met the minimum factual requirement of some

state action, no mater how subtle, to justify any state im-

posed remedy or solution in this case.

The judgment of the court in Sheff is entirely consis-

tent with the legal arguments made by the Intervenors. In

the absence of some showing of state action, under equal

protection analysis the solutions suggested by the Sheff

plaintiffs and not objected to by the Sheff defendants are

not constitutionally appropriate. This is the gravamen of

the Intervenors position.

4) The Privileges and Immunities of School Districts.

Another main legal argument made by the Intervenors was

that based upon the rationale of Milliken I, legally indep-

14

endent local school districts which had not been the cause

of racial segregation could not be made the subject of any

remedial action by the state. I.Ex. 7 at 30-40. The Court

in Milliken I specifically addressed the argument made by

the Detroit plaintiffs that school district lines are no

more than arbitrary lines on a map drawn for political con-

venience and rejected that argument in its entirety. As the

Court stated, "Boundary lines may be bridged where there has

been a constitutional violation calling for interdistrict

relief, but the notion that school district lines may be

casually ignored or treated as a mere administrative conven-

ience is contrary to the history of public education in our

country." Milliken v. Bradley, supra., 418 U.S., at 741-742.

The Court more recently reiterated this statement in another

case cited by the Intervenors. As the Court stated in Board

of Education of Okla. City P. Sch. v. Dowell, U.S. 7-111

S.Ct. 630, 637 (1991), "Local control over the education of

children allows citizens to participate in decision making

and allows innovation so that school programs can £1: local

needs. The legal justification for displacement of local

authority by an injunctive decree is a school desegregation

case is a violation of the Constitution by local authori-

ties."

In reaching its decision in Sheff, this court did not

cite Milliken I or Dowell. It reached the same result, how-

ever, by citing another federal case, Spencer Vv. Kugler, 326

F.Supp. 1235, affirmed, 404 U.S. 1027 (1072). As this court

15

stated in its decision, "[r]acially balanced municipalities

are beyond the pale of either judicial or legislative inter-

vention. Id., 1240" Memorandum of Decision at 71-72. Whether

the citation is to Milliken I or to Spencer v. Kugler, the

result is the same. Once again the court's decision directly

paralleled the legal arguments presented by the Intervenors.

IV. The Intervenors Should be Fully Reimbursed for

Their Attorneys' Fees and Costs in This Case

Turning to Judge Dorsey's two-fold test for determin-

ing whether or not a party has "prevailed", the Intervenors

do not believe that there is any serious question as to the

second prong of the test, namely that the Intervenors'

claims, if pressed, were not frivolous, unreasonable, or

groundless. Thomas v. Board of Trustees, supra., 599 F.Supp.

at 334. As to compliance with the first prong, that the

Intervenors claims must be causually linked to the achieve-

ment of the relief obtained, the key issue is the "provoca-

tive" or catalytic role of the Intervenors' claims. e,

Nadeau v. Helgemoe, 581 F.24 275, 280-81 (lst Cir. 1978). On

this issue the Intervenors rely on the candor and courage of

the court in making this decision. Did the Intervenors

play a "provocative" or catalytic role in leading this court

to its ultimate decision? Based upon the public statements

of the court, the fact that the arguments urged by the

Intervenors were entirely separate and distinct from the

arguments raised by the Sheff defendants and the signifi-

cance of those arguments in this court's Memorandum of Dec-

ision, the Intervenors have no doubt of the role they played

16

in this litigation. They nov look to the court to confirm

their role and grant this Motion.

As Judge Dorsey noted in Thomas:

Once a plaintiff is found to be a "prevailing party"

it must be determined whether the plaintif has asserted

any unsuccessful claims "distinctly different" from,

i.e., based on "different facts and legal theories,"

than the successful claims...If plaintiff's successful

and unsuccessful claims are a "common core of facts,"

or are based on "related legal theories," and if the

results obtained are "excellent," all hours reasonably

expended on the litigation are normally compensablz.

500 F.Supb., at 334.

In this case, the Intervenors results were excellent

and all the fees and costs requested in Schedule A attached

to the accompanying affidavit should be paid fully. With re-

gard to the projected fees and costs related to the appeal

of this court's decision, those estimates should be consid-

ered the maximum and should be paid by the defendants only

upon receipt of invoices tendered after completion of the

legal work related to the appeal process.

This Motion filed within 10 days of the successful

decision of this court is timely. The fact that the Inter-

venors did not cite either §1983 or § 1988 specifically in

the Motion to Intervene does not in any way negate consider-

ation of this motion at this time. In Americans United for

Separation of Church and State v. School District of Grand

Rapids, 835 F.2d 627 (6th Cir. 1987), the court was faced

with the question of, "[w]hether plaintiffs who prevail in

an action against the state authorities to vindicate rights

secured by the Constitution must plead and rely specifically

upon 42 U.S.C. § 1983 in order to be entitled to an award of