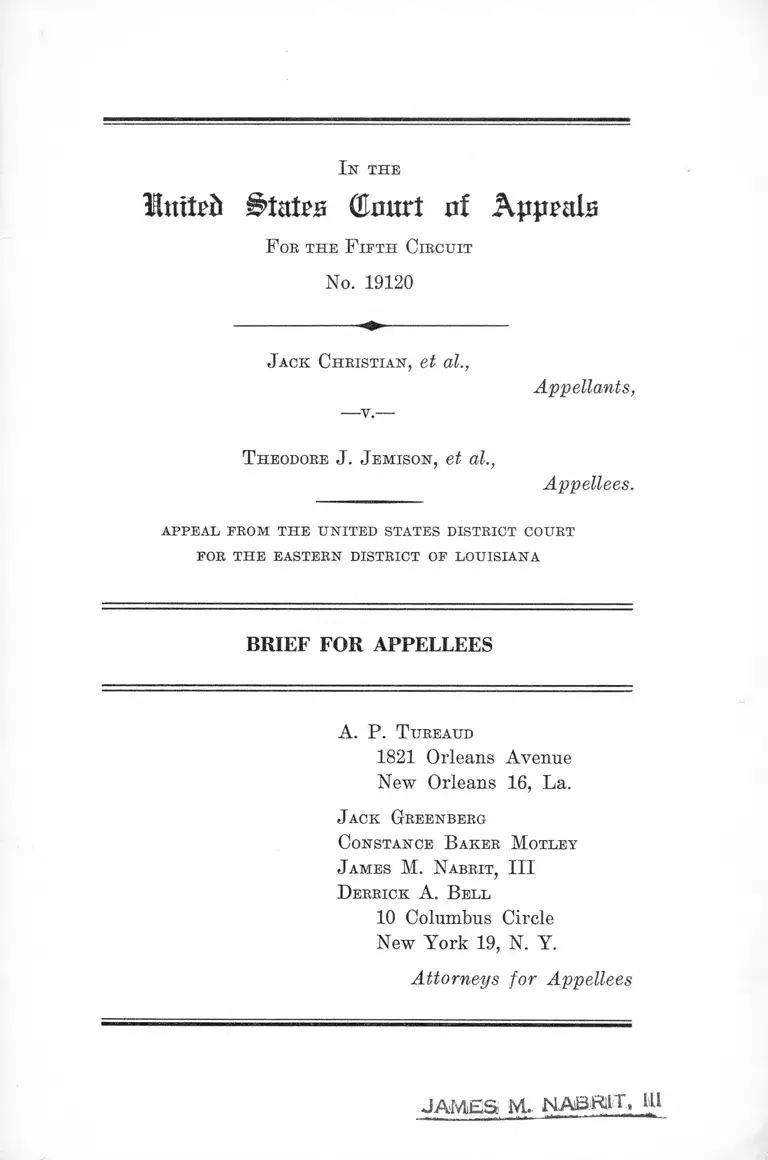

Christian v. Jemison Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Christian v. Jemison Brief for Appellees, 1961. 6edd427a-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0a6bf6e6-53a7-4b89-b4d4-227809eb279b/christian-v-jemison-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

Ik t h e

Mxntzb States (tort of Appeals

F oe th e F if t h C ircuit

No. 19120

J ack C hristian , et al.,

Appellants,

T heodore J . J em ison , et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL PROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

A. P. T ureaud

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans 16, La.

J ack Greenberg

Constance B aker M otley

J ames M. N abrit, III

D errick A. B ell

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y,

Attorneys for Appellees

JAM ES M. NAiBHilT, ill

SUBJECT INDEX

Statement of tlie Case......... .............................................. 1

A rgument :

I. The Plea Of Ees Judicata And The Alternative

Motions That The Case Be Remitted To State

Courts And For A Jury Trial Were Properly

Overruled And Denied By The Court Below .... 7

II. The Baton Rouge Bus Segregation Ordinance Is

Plainly Invalid Under Settled Precedent And

There Were No Genuine Issues Of Material

PAGE

Facts ......................................................................... 11

Co n c l u s io n ........................................................................... 14

T able op Cases C ited

Baldwin v. Morgan, 251 F. 2d 780 (5th Cir. 1958) .....12,13

Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750 (5th Cir. 1961) ....... 12

Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., 280 F. 2d 531 (5th

Cir. 1960) .................... ............... .......... ....... ................- 12

Bratley v. Nelson, 67 F. Supp. 272 (S. D. Fla. 1946) .... 10

Browder v. City of Montgomery, 146 F. Supp. 127

(M. D. Ala. 1956) ........................................................... 12

Browder v. Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707 (M. D. Ala. 1956),

aff’d. 352 U. S. 903 (1956) ............. ........... 7, 8, 9,10,11,12

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) ..... 7, 8

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 (1955) ..... 7, 8

Douglas v. City of Jeannette, 319 U. S. 157, 163 ........... 10

XI

Fletcher v. Norfolk Newspapers, Inc., 239 F. 2d 169

(4th Cir. 1956) ................................................................. 13

Harrison v. NAACP, 360 IT. S. 185 ......... ......................... 9

Iselin v. C. W. Hunter Co., 173 F. 2d 388 (5th Cir. 1949) 7

Jemison v. City of Baton Rouge, No. 46,023, 19th Jud.

Dist. Ct. of La. (Jan. 20, 1954) ................................ . 6

Lawlor v. National Screen Services Corp., 349 IT. S.

322, 99 L. ed. 1122, 75 S. Ct. 865 (1955) ....................... 8

Morrison v. Davis, 252 F. 2d 102 (5th Cir. 1958), cert,

den. 357 IT. S. 944 (1958) ....................................... 9,12,13

(Means Parish School Boaxvl v. Bush, 268 F. 2d 78, 80

(5th Cir. 1959) ........ 9

Richard v. Credit Suisse, 242 N. Y. 346, 152 N. E. 110

(1926) .............................................................................. 14

Toomer v. Witsell, 334 U. S. 385, 392 n. 15 (1948) ....... 9

Williams v. Kolb, 79 IT. S. App. D. C. 253, 145 F. 2d 344

(D. C. Cir. 1944) ............................................ ................ 13

Other A uthorities Cited

1 Moore’s Federal Practice, Par. 0.401, p. 4018 ........... 8

5 Moore’s Federal Practice, Par. 38.24[1] ................. 12

6 Moore’s Federal Practice, Par. 56.04, pp. 2028 et seq. 14

28 United States Code, §1331....... ............... ..................... 2

28 United States Code, §1343 ........................................... 2

PAGE

Ill

PAGE

42 United States Code, §1981............................................ 2

42 United States Code, §1983 ............................................ 2

Emergency Ordinance, No. 251 of the City of Baton

Rouge ..................................................... 2, 3,4, 5, 6, 7,12,13

L.S.A.-R.S. 45:194, 45:195, 45:196, which were repealed

by Act No. 261, Louisiana Acts of 1958 .......... ............ 2

Restatement, Judgments, §46, Comment b, §53, Com

ment c ................... .......................................................... 8

Rule 56, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure................. . 13

In t h e

Wuxteb States (Emtrt of Appals

F ob th e F ifth Cikcuit

No. 19120

J ack Christian , et ol.,

-v.-

Appellants,

T heodore J . J em ison , et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

Statement of the Case

This action was filed February 4, 1957 in the United

States District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana

by plaintiffs, Theodore J. Jemison, Edward \Y. Brown,

Felton B. Hitchens, Dupuy H. Anderson, Curtis J. Gil

liam and Louis J. Jones. The defendants in this action

are numerous named individuals who hold offices as the

Mayor-President of the City of Baton Rouge and Parish

of East Baton Rouge, Louisiana, the members of the City-

Parish councils of said city and parish, the city chief of

police, the parish sheriff, and the manager of the Baton

Rouge Bus Company, Inc. The last-mentioned corporation

was also named as a defendant.

Jurisdiction of the trial court was invoked on alterna

tive grounds, namely (1) “ federal question” jurisdiction

2

under 28 U. S. C. §1331, the matter involving questions

under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States and under 42 U. S. C. §1981; and (2)

“ civil rights” jurisdiction under 28 U. S. C. §1343 as au

thorized by 42 U. S. C. §1983 to enforce rights under the

Fourteenth Amendment and 42 U. S. C. §1981. The Com

plaint sought injunctive and declaratory relief, against

several state statutes (which have now been repealed)1 and

a city ordinance, i.e., Emergency Ordinance No. 251 of the

City of Baton Rouge, which provides as follows:

Amending Title 10, Chapter 2, of the Baton Rouge

City Code of 1951, by amending Section 118, “ Seating

of Passengers,” so as to provide for the separation of

races in the buses in the City of Baton Rouge; pro

viding for the reservation of certain seats; making

certain exceptions; and providing penalties for failure

to comply therewith.

W hereas, on March 11, 1953, the City Council of

the City of Baton Rouge adopted Ordinance No. 222,

providing a method for seating passengers riding any

buses for hire within the City of Baton Rouge; and,

W hebeas, by an opinion dated June 18, 1953, .the

Office of the Attorney General held that such ordinance

was invalid as being in conflict with the Louisiana,:

Revised Statutes Title 45, Section 194 and 195; and,

W hereas, it is necessary that the Council now adopt

a suitable ordinance regulating the seating of pas

sengers on buses for hire within the City of Baton

Rouge and an emergency, within the meaning of Sec

tion 2.12 of the Plan of Government exists, requiring

that such ordinance be adopted without the necessity

1 These statutes were L.S.A.-R.S. 45 :194, 45 :195, 45 :196, which

were repealed by Act. No. 261, Louisiana Acts of 1958. Cf. Mor

rison v. Davis, 252 F.2d 102 (5th Cir. 1958), cert. den. 357 U.S.

944 (1958).

3

of a public hearing or introduction and a second read

ing, as otherwise required by Section 2.12 of the Plan

of Government:

Now, therefore, be it ordained by the City Council

of the City of Baton Rouge that Title 10, Chapter 2,

of the Baton Rouge City Code of 1951, be and the same

is hereby amended by repealing the present Section

118 thereof and re-enacting same so as to add thereto

a section 118, which shall read as follows:

Section 118. Seating of Passengers.

(1) Separation of Races in Buses: Every transpor

tation company, lessee, manager, receiver or owner

thereof, operating passenger buses in the City of Bat

on Rouge as a carrier of passengers for hire, shall

require that all white passengers boarding their buses

for transportation shall take seats from the forward

or front end of the bus and that all Negro passengers

boarding their buses for transportation shall take

seats from the. back or rear end of the bus.

(2) Reservation of Seats: No white passenger shall

occupy the long rear seat of the bus, which shall be re

served for the sole and exclusive use of negro pas

sengers. No negro passenger shall occupy the two

front seats facing the aisle of the bus, but such seats

shall be reserved for the sole and exclusive use of

white passengers.

(3) No passengers of different races shall occupy

the same seat.

(4) When there maybe or become vacant and avail

able for occupancy any seat in the rear of a seat oc

cupied by a Negro passenger or passengers, such

negro passenger or passengers shall, when requested

by the operator of the bus, remove to such rear seat;

4

and, likewise, when there may be or become vacant

and available for occupancy any seat in front of any

seat occupied by a white passenger or passengers, such

white passenger or passengers shall, when requested

by the operator of the bus, remove to such front seat.

(5) Authority of Bus Operator: The operator on

all passenger buses in the City of Baton Rouge shall

have authority to refuse any passenger further oc

cupancy or use of any bus in the City of Baton Rouge

unless such passenger shall comply with the provisions

of this ordinance.

(6) Chartered and Special Buses: The provisions

of this ordinance shall not apply to any chartered bus

or special bus run strictly designated for the exclusive

use of members of any race, but in all such cases, such

bus or buses shall he plainly marked “ Charter” or

“ Special.”

(7) Penalties: Any person, firm, corporation or as

sociation of persons or a member thereof convicted of

violating any provisions of this ordinance shall be

fined not less than ten dollars ($10.00). nor more than

one hundred dollars ($100.00), or imprisonment for

not less than ten (10) days, nor more than sixty (60)

days, or both, at the discretion of the Court for each

offense.

(8) This ordinance, being an emergency ordinance,

shall be effective upon adoption.

The verified complaint (R. 3-15), alleged, in summary,

that plaintiffs were Negro citizens of the City of Baton

Rouge, and Parish of East Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and

that they used the public transportation system operated

by the defendant bus company. The complaint alleged the

identity of the various defendants as public officials, the

5

identity of the manager of the bus company, and that the

company was engaged in carrying passengers for hire

under a franchise issued by the City of Baton Rouge. It

was further alleged that on December 28, 1956, plaintiffs

met with the bus company manager and requested that they

and other Negroes be permitted to use the company buses

on a nonsegregated basis; that the manager informed them

that the bus company would abide by the existing state

laws and municipal ordinances; that on January 3, 1957

plaintiffs met with the defendant Mayor-President of the

City and Parish and members of the City-Parish councils

again requesting the right to use the buses on a non

segregated basis; and that these defendants “ told plain

tiffs that the aforementioned statutes of the State of Louisi

ana and ordinances of the City of Baton Rouge, Louisiana

are valid and would be enforced by defendants until de

clared unconstitutional, null and void by a court of com

petent jurisdiction” (R. 11-12).

On March 27, 1957, in response to the complaint defen

dants filed a motion to dismiss, a plea of res judicata, an

alternative request that the case be remitted to the state

courts, and a further alternative request for a jury trial

(R. 16-21; 29-32). Following a hearing on October 14,

1957, the court entered an order denying the various de

fense motions on March 24, 1957 (R. 79). Thereafter no

further proceedings were had until plaintiffs filed a motion

for summary judgment on February 29, 1960 (R. 80). The

defendants filed their Answer on October 12, 1960 (R. 84-

92). The answer defended Ordinance No. 251 as a valid

exercise of the police powers, generally admitted the iden

tity of the various defendants, admitted that the two meet

ings referred to in the complaint had occurred, but denied

the allegations that plaintiffs were Negro residents of

Baton Rouge who used the city buses, denied jurisdiction,

and denied that the buses were being operated on a “ segre

6

gated basis.” The answer acknowledged that the ordinance

in suit was “ in effect.” In addition, a copy of a prior or

dinance requiring separation of the races in buses was

appended to the answer, which asserted that the “ only dif

ference” between the two ordinances was that the current

ordinance contains a provision which “ reserves the long

rear seat on the bus for the exclusive use of those Negro

passengers who wish to use it, and a reservation of the

two short front seats for the exclusive use of those white

patrons who wish to use them” (R. 90).

Defendants appended to their pleadings copies of the

petition (R. 64-78), opinion (R. 32-50), and judgment (R.

50-51) in a case decided on January 20, 1954 in the Louisi

ana 19th Judicial District Court, captioned Jemison v. City

of Baton Rouge, No. 46,023, which was relied upon to sup

port the claim of res judicata in bar of the present action.

This prior case was concluded in 1954, prior to the events

of 1956 and 1957 which formed the basis for the present

suit. The prior litigation was primarily concerned with a

claim that Emergency Ordinance No. 251 was not authorized

by various provisions of local law (see Petition R. 65-77).

The validity of the ordinance under the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States was not put

in issue, and no Federal Constitutional issues were decided

by the state court, on the ground that no specific consti

tutional provisions had been invoked (R. 49). Only two

of the plaintiffs in the instant case (Jemison and Hitchens)

were parties to the prior proceeding and none of the de

fendants in the present suit were parties to the prior case,

the only defendant named in that case being the City of

Baton Rouge (R. 64).

The plaintiffs’ motion for summary judgment was sub

mitted to the Court on October 12, 1960 and considered

again on March 31, 1961. A final Judgment in favor of

7

the plaintiffs was entered on April 5, 1961 (R. 97). The

Court found that there were no genuine issues as to any

material facts, and that the ordinance was plainly invalid

under the Fourteenth Amendment and the federal civil

rights acts. A judgment granting declaratory and injunc

tive relief restraining enforcement of the ordinance was

entered. Notice of Appeal was filed May 2, 1961.

ARGUMENT

I.

The plea of res judicata and the alternative motions

that the case he remitted to state courts and for a jury

trial were properly overruled and denied by the court

below.

A. The prior litigation which is urged in bar of the

present suit has been described above in the Statement of

the Case. As indicated therein, the prior litigation in

volved different parties, different issues and was con

cluded in 1954, several years prior to the events complained

of in the present action, namely, (1) the December 1956

and January 1957 demands by plaintiffs for desegregation

of the city buses, (2) the refusal of these demands by the

defendants, (3) and the continuing operation of Emer

gency Ordinance 251 in the years following. Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954), 349 U. S. 294

(1955), and Browder v. Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707 (M. D.

Ala. 1956), aff’d 352 U. S. 903 (1956).

It is familiar doctrine that res judicata precludes fur

ther litigation of the same cause of action between the

same parties, but does not bar litigation as to other causes

of action. See Iselin v. C. IF. Hunter Co., 173 F. 2d 388

8 .

(5th Cir. 1949); 1 Moore’s Federal Practice, fjO.401, p.

4018.

Lawlor v. National Screen Services Corporation, 349

U. S. 322, is dispositive of the issue raised by appellants’

claim of res judicata. In that case the Court held at 349

U. S. 322, 327-28:

That both suits involved “ essentially the same course

of wrongful conduct” is not decisive. Such a course of

conduct—for example, an abatable nuisance—may fre

quently give rise to more than a single cause of action.

And so it is here. The conduct presently complained

of was all subsequent to the 1943 [prior] judgment.

The Court went on to observe that while a judgment is

res judicata as to claims arising prior to its entry “ . . . it

cannot be given the effect of extinguishing claims which do

not even then exist and which could not possibly have been

sued upon in the previous case” (Id. at 349 U. S. 329). It

was made clear that the rule of the Lawlor case was appli

cable to proceedings in equity as well as to a damage claim;

see note 16 at 349 U. S. 329, citing Restatement, Judgments,

§46, Comment b ; §53, Comment c.

The continuing enforcement of a segregation ordinance

is plainly a continuing wrongful course of conduct within

the rule of the Lawlor case. Furthermore, it would be

manifestly unjust and unconscionable to rule as appellants

urge, that a segregation ordinance upheld prior to the de

mise of the “ separate but equal” doctrine in the Brown and

Browder cases, supra, must therefore go unchallenged for

ever.

B. Appellants insist that if the plea of res judicata be

overruled, the appellees should nevertheless be required to

proceed in the State courts and obtain there a ruling on

9

the ordinance in question. Similar abstention-type argu

ments have been raised in this Circuit at least twice in

cases involving statutes and ordinances requiring racial

segregation in public transportation facilities.

In Browder v. Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707 (M. D. Ala. 1956),

affirmed, 352 U. S. 903, Judge Rives, speaking for a three-

judge district court, set forth the guiding principle by

stating:

. . . the doctrine [of comity] has no application where

the plaintiffs complain that they are being deprived of

constitutional civil rights, for the protection of which

the Federal courts have a responsibility as heavy as

that which rests on the State courts. 142 F. Supp. at

713.

More recently in Morrison v. Davis, 252 F. 2d 102 (5th

Cir. 1958), cert, denied, 356 IT. S. 968, which involved a test

of the Louisiana statute requiring segregation in local

public transportation facilities, this Court per curiam held

that the withholding of federal court action for reasons of

comity was not required,'citing the Supreme Court action

in Browder v. Gayle, supra. See also, Orleans Parish School

Board v. Bush, 268 F. 2d 78, 80 (5th Cir. 1959).

In Harrison v. NAACP, 360 U. S. 185, the Court applied

the abstention principle because of its inability to find that

the terms of the statutes there involved left no reasonable

room for a construction by the state courts. But there is no

room for interpretation by the State courts of the Baton

Rouge ordinance which specifically requires the seating of

passengers according to race, a requirement which appel

lees contend renders it unconstitutional on its face. There

fore, abstention could not result in avoiding decision of the

federal constitutional issues presented, and would be im

proper. Toomer v. Witsell, 334 U. S. 385, 392, n. 15 (1948).

10

None of the authorities relied on by appellants alters

this conclusion. In Bratley v. Nelson, 67 F. Supp. 272

(S. D. Fla. 1946), plaintiffs sought to void a city ordinance,

the validity of which was then being tested in the state

courts by one of the plaintiffs arrested for violating its

provisions. The court ruled that equitable relief which

would interfere with state criminal prosecutions, should

be refused since the facts did not show “ irreparable injury

which is clear and imminent.” Douglas v. City of Jeannette,

319 XL S. 157,163.

A contrary decision has been reached by this Court in

cases similar to those in issue here, Browder v. Gayle,

supra, Morrison v. Davis, supra, in the latter of which the

Court indicated that “ to the extent that this [the Browder

case] is inconsistent with Douglas v. City of Jeannette, Pa.,

we must consider the earlier case modified.” 252 F. 2d at

103. Appellees suggest that a similar modification of any

inconsistencies in Judge Johnson’s ruling in Browder v.

City of Montgomery. 146 F. Supp. 127 (M. D. Ala. 1956)

must be made in light of the more recent Browder v. Gayle

case in which Judge Johnson joined the majority.

C. In the further alternative, appellants charge that

they are entitled to jury trial as to issues of fact regarding

whether Ordinance No. 251 was adopted in the valid exer

cise of the police power, and whether conditions existing

then still prevail. The short answer to this contention is

that in a suit for injunction which is essentially equitable

in nature, there is no right to a trial by jury, Moore’s

Federal Practice, 1138.24 [1]. Here, appellees have sought

and obtained an injunction. Moreover, it is appellees’ con-,

tention that there were no substantial issues of fact in

volved in this case. See Argument II, infra.

11

II.

The Baton Rouge bus segregation ordinance is plainly

invalid under settled precedent and there were no

genuine issues of material facts.

The appellants’ contentions that there were material

issues of fact which required a trial for their resolution

and that the ordinance in suit is valid under the Fourteenth

Amendment may be treated together. It is submitted that

neither claim has merit.

A cursory review of the provisions of Ordinance 251

reveals that it compels racial segregation in violation of

the Fourteenth Amendment. One paragraph entitled “ Sep

aration of Races in Buses,” requires bus companies to re

quire all white passengers to take seats from the front and

all Negro passengers to take seats from the rear of the

bus; the next paragraph reserves a rear seat for Negroes

and two front seats for white passengers; the next prohibits

passengers of different races to occupy the same seat;

the next paragraph requires passengers to move to the

rear (Negroes) or the front (whites) on direction of bus

operatorsthe next provision authorizes buses to refuse

transportation to anyone not obeying the ordinance; the

next exempts from the law chartered buses run for the

exclusive use of any race; the next provides criminal pen

alties ; and the last provides that the ordinance be effective

immediately upon its adoption as an emergency ordinance.

The proposition that an ordinance requiring racial segre

gation on local buses and other local public transportation

facilities is unconstitutional under the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States is so clearly

settled as not to require argument. Browder v. Gayle, 142

F. Supp. 707 (M. D. Ala. 1956), affirmed 352 U. S. 903

1 2

(1956) ; Morrison v. Davis, 252 F. 2d 102 (5th Cir. 1958) ;

Baldwin v. Morgan, 251 F. 2d 780 (5th Cir. 1958); Bonian v.

Birmingham Transit Co., 280 F. 2d 531 (5th Cir. 1960);

Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750 (5th Cir. 1961). The

cases cited above recognize no distinction snch as that

urged by appellants, between an ordinance which required

Negroes and whites to occupy certain firmly designated

portions of a bus, and one like Ordinance No. 251 adopting

another more flexible formula to require separation of the

races on buses. There is plainly no merit in appellants’

intimation that this ordinance merely provides for volun

tary segregation; it compels segregation under penalty of

fine and imprisonment. As the Court stated so recently

in Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750, 754 (1961) :

“What is forbidden is the state action in which color

(i.e. race) is the determinant. It is simply beyond the

constitutional competence of the state to command that

any facility either shall be labeled as or reserved for

the exclusive or preferred use of one rather than the

other of the races.”

The appellants’ claim that there are material issues of

fact rests in part upon its legal argument that its statute

designating certain seats for the exclusive use of Negro

and white patrons and prohibiting different races from

occupying the same seat is materially different from the

laws involved in the Browder case, supra, which required

segregated sections on buses (see Appellants’ Brief, pp.

16-17). This is the basis for the defense that there is no

“ segregation” on the buses, the argument being that this

is so since there are no segregated sections set aside on

each bus under the ordinance. It is clear that this does not

present any factual question requiring a trial. There is

no suggestion in the record that the defendants have aban

13

doned Ordinance No. 251 conceding its validity; rather

defendants continue to maintain the contrary even in this

Court.

The formal issue raised by the denial that plaintiffs are

Negroes, are residents of Baton Rouge, and use the buses

is plainly insufficient to raise a genuine issue. The allega

tion on these matters was made in a verified complaint, no

specific averment of the answer alleged any conflicting

facts—there was merely a general denial; and no opposing

affidavit or statement indicating the unavailability of proof

by affidavit was submitted (see Rule 56, Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure). Where verified pleadings are submitted,

even though not required by the rules, they may be treated

as affidavits for the purposes of Rule 56. See Fletcher v.

Norfolk Newspapers, Inc., 239 F. 2d 169 (4th Cir. 1956);

Williams v. Kolb, 79 U. S. App. D. C. 253, 145 F. 2d 344

(D. C. Cir. 1944).

Finally plaintiffs are not required as a prerequisite to

an action to enjoin a bus segregation ordinance to show that

they disobeyed the ordinance and risked arrest, or were

arrested. See Baldwin v. Morgan, 251 F. 2d 780, 787 (5th

Cir. 1958), and Morrison v. Davis, 252 F. 2d 102 (5th Cir.

1958). In the Morrison case the Court said:

Since all transportation can be denied them [Ne

groes] under the statute unless they obey the illegal

requirement, it is not even apparent that they could

put themselves in position to be arrested and prose

cuted even if they sought to test their constitutional

rights in that manner, which we hold they do not have

to do (252 F. 2d at 103).

It is settled that under Rule 56, Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure, the courts can pierce formal allegations or de

nials in pleadings and render judgment where there are

14

no genuine factual disputes. 6 Moore’s Federal Practice

T156.04, pp. 2028 et seq. The basic principle applicable here

was succinctly stated by Judge Cardozo (later Mr. Justice

Cardozo) in Richard v. Credit Suisse, 242 N. Y. 346, 152

N. E. 110 (1926) : “The very object of a motion for sum

mary judgment is to separate what is formal or pretended

in denial or averment from what is genuine and substantial,

so that only the latter may subject a suitor to the burden

of trial.”

CONCLUSION

Appellees respectfully submit that the judgment of

the Court below should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

A. P. T ubeatjd

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans 16, La.

J ack (xbebnbebg

C onstance B akee M otley

J ames M . N abbit, III

D ebeick A. B ell

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellees