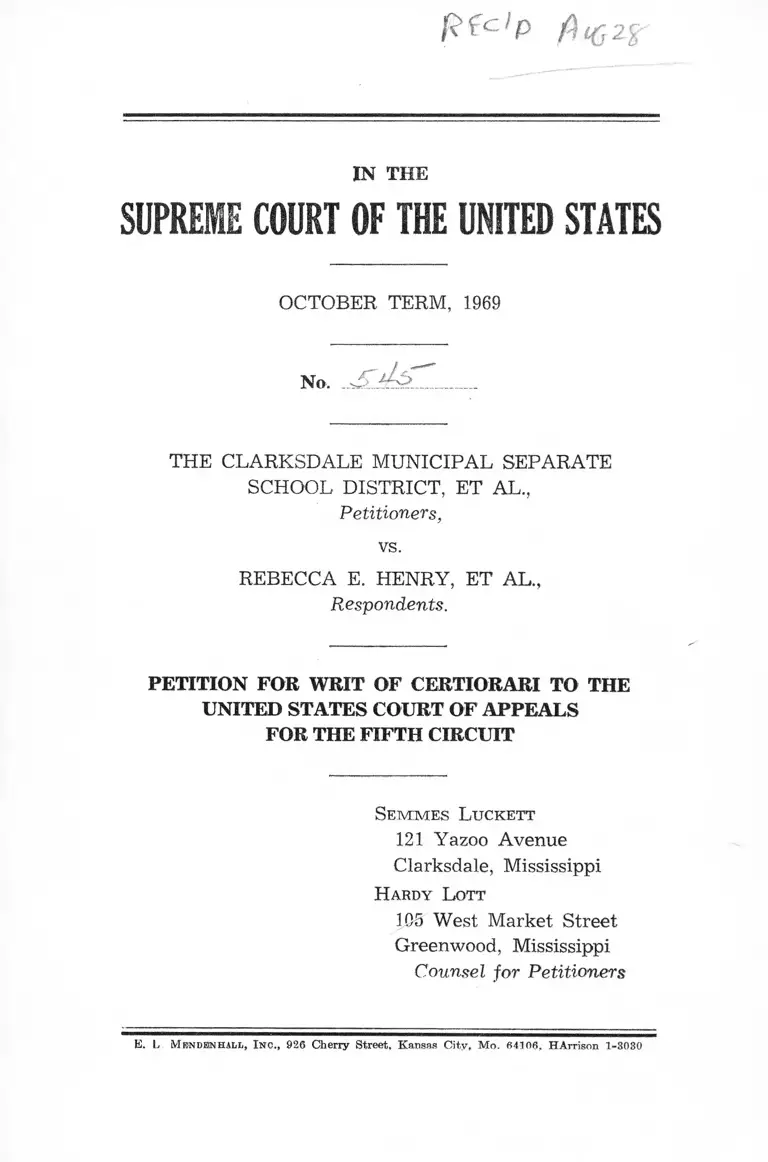

Clarksdale School District v. Henry Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Public Court Documents

August 27, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Clarksdale School District v. Henry Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1969. 0e22a6b6-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0a6f7150-9e2c-45b4-86db-5c70392be956/clarksdale-school-district-v-henry-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Rf c / P f l i f i 2%

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1969

THE CLARKSDALE MUNICIPAL SEPARATE

SCHOOL DISTRICT, ET AL.,

Petitioners,

vs.

REBECCA E. HENRY, ET A L ,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Semmes Luckett

121 Yazoo Avenue

Clarksdale, Mississippi

Hardy Lott

105 West Market Street

Greenwood, Mississippi

Counsel for Petitioners

E. L M endbnhall, I n c ., 926 Cherry Street. Kansas City. Mo. 64106. HArrison 1-3080

INDEX

Opinions Below ............. ..................................................— 2

Questions Presented for Review ................ ..................... 3

Constitutional Provisions and Statutes Involved ....... 5

Statement of the Case .......................... ....... ................. 6

Reasons for Allowance of the Writ ................... .......... 14

Brown Directed, As the Means of Achieving the

Desegregation of the Schools of a District, the

Creation of Compact Attendance Areas or Zones .... 15

Brown Requires the Creation of School Systems Not

Based on Color Distinctions ......... ...... ........... ....... 16

De Facto Segregation—Which Occurs Fortuitously

Because of Housing Patterns—According to Brown

and the Holdings of the Seventh, Tenth, Fourth

and Sixth Circuit Courts of Appeals, Does Not

Make an Otherwise Acceptable Desegregation

Plan Unconstitutional ............................ ................. .. 20

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 Validates Bona Fide

Neighborhood School Lines and Prohibits Court

Orders Intended to Alleviate Racial Imbalance in

Neighborhood Schools ................. ......... ....... .......... _ 31

The Constitutionality of an Attendance Area De

segregation Plan Is to Be Judged by the Decisions

in Those Cases Dealing with Such Plans. It Is

Not to Be Judged by Decisions Dealing with

“Freedom-of-Choice” Plans, for Those Decisions

Are Based on Considerations Foreign to Attend

ance Area Plans ........... ..... ............ ......... ................. 34

Conclusion ................ ................................... ........................ 40

Certificate of Service ...... ........ ............. .......................... 42

Appendix—

Opinion, United States Court of Appeals, Fifth Cir

cuit, March 6, 1969 ......................................... ... ....... A1

II In dex

Judgment, United States Court of Appeals, Fifth

Circuit, issued June 26, 1969 ........................... ...... A23

Petition for Rehearing and Petition for Rehearing

en Banc, United States Court of Appeals, Fifth

Circuit, denied June 26, 1969 ........... ............ ....... . A25

Order of the District Court Dated June 26, 1964 .... A26

Memorandum Opinion of District Court Dated Au

gust 10, 1965 ............... ..... ..................................... . A31

Order of the District Court Dated August 10, 1965 A68

Order of the District Court Amending Order of Oc

tober 1, 1965 ................ .............................. .................A74

Memorandum Opinion of the Court Dated De

cember 13, 1965 __________ __ - _______ _______ A76

Order of the District Court Dated December 13,

1965 ..................... ....... ................................... .................A83

Table of Cases

Bell v. School City of Gary, Ind., 324 F. 2d 209 (certio

rari denied 377 U.S, 924, 12 L. Ed 2d 216) 3, 4, 22, 30, 31,34

Broussard v. Houston Independent School District,

206 F. Supp. 266, 395 F. 2d 817 ___________ ____-.-28, 30

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 98 L. Ed.

873; 349 U.S. 294, 99 L. Ed. 1083 ....... 3, 4, 7,12,14,15,16,

.... ........................ .................17, 20, 21, 22, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 41

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 139 F. Supp.

468 ........ ............................. ....................................... ........ 21

Collins V. Walker, 328 F. 2d 100 ...................................... 19

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, 364 F. 2d 896 ................. .......... ................- ...... . 34

Deal V. Cincinnati Board of Education, 369 F. 2d 55 ....24, 26

Downs v. Board of Education of Kansas City, 336 F.

2d 988 (certiorari denied 380 U.S. 914, 13 L. Ed. 2d

800) ........ ..........................................................................23,30

Gilliam v. School Board of the City of Hopewell, Va.,

345 F. 2d 325 ................................ .................. ....... ......24,30

Index hi

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683, 10 L. Ed.

2d 632 ..................................... .......... ............. .................-

Goss v. Board of Education, City of Knoxville, Tenn.,

406 F. 2d 1183 ............................................................... 26,

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

Va., 391 U.S. 430, 20 L. Ed. 2d 716 ...... ......... ....... ...38,

Griggs v. Cook, 272 F. Supp. 163 (N.D. Ga., July 21,

1967), affirmed 384 F. 2d 705 .......................... ...... ...26,

Holland v. Board of Public Institutions, 258 F. 2d

730 __ ____ _____ _______________ _________- .... ... .

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of the City of

Jackson, Tenn., 391 U.S. 450, 20 L. Ed. 2d 733 _____

Moses v. Washington Parish School Board, 276 F.

Supp. 834 (E.D. La., Oct. 26, 1967 ...........28, 30, 36, 37,

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537, 41 L. Ed. 256 .......17,

Raney v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 443, 20 L. Ed.

2d 727 ____ ________________ __________ ____________

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 355 F. 2d 865 ...... .......... ............. ................ ..... .

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

372 F. 2d 836; 380 F. 2d 385 ...............31, 32, 33, 34, 38,

Statutes and Constitutional Provisions

Civil Rights Act of 1964 ......................3,4,5,15,31,33,

Section 401 (42 U.S.C. §2000c) .... .......... ......4,5,32,

Section 407 (42 U.S.C. §2000c-6) .............. 4, 5, 32, 33,

Section 410 (42 U.S.C. §2000c-9) ______ 4, 6, 32, 33,

Fourteenth Amendment, Constitution of the United

States ................................................... ............ .5, 6, 15, 40,

28 U.S.C. §1343 (3) ........................................... .............

42 U.S.C. §1983 .................................................................

17

30

39

30

29

35

38

41

39

37

39

34

40

40

40

41

6

6

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1969

No.

THE CLARKSDALE MUNICIPAL SEPARATE

SCHOOL DISTRICT, ET AL„

Petitioners,

vs.

REBECCA E. HENRY, ET AL.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners, Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, a school district organized under the laws of Missis

sippi, Gycelle Tynes, Superintendent of the schools of the

school district, and the members of the Board of Trustees of

the school district, pray that a writ of certiorari issue to

review the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit entered in the above case on March

6, 1969.

2

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinions and orders of the District Court of the

United States for the Northern District of Mississippi in

the above case are not reported. Copies are included in

the Appendix at pages A26 to A84. The opinions of

Claude F. Clayton, District Judge, rendered August 10,

1965, and December 10, 1965, which are included in the

Appendix at pages A31 to A67, and pages A76 to A82,

and the orders of the District Court entered pursuant thereto

on said dates, which are included in the Appendix at

pages A68 to A75, and pages A83 to A84, are the opinions

and orders from which respondents appealed to the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals,

which was rendered March 6, 1969, more than 33 months

after the case was argued before that court on May 25,

1966, is reported at 409 F. 2d 682. A copy is included in

the Appendix at pages A1 to A22.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit was made and entered on March 6,

1969. A copy is included in the Appendix at pages A23 to

A24.

The order of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit denying petitioners’ Petition for Rehear

ing in Banc was made and entered on June 26, 1969. A

copy is included in the Appendix at page A25.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under U.S.C.

1254 (1).

3

QUESTIONS PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

In Brown I and Brown II (347 U.S. 483. 98 L. Ed.

873; 349 U.S. 294, 99 L. Ed 1083), this Court called for

the cessation of the practice of segregating children solely

on the basis of their race, and the establishment of sys

tems whereby the admissions of children to public schools

would be determined on a nonracial basis. In spelling out

how those objectives could be accomplished, it authorized

the revision of school districts and attendance areas,

within the limits set by normal geographic school district

ing, into compact units, to bring about a system not based

on color distinctions. Consequently, when the Seventh,

Tenth, Fourth and Sixth Circuit Courts of Appeals were

required to pass on the constitutionality of desegregation

plans which provided for the creation of attendance areas

or zones fairly arrived at, bounded by natural, nonracial

monuments which defined, in truth and in fact, true

neighborhoods, and directed that all children living in an

attendance area or zone, without exception, should attend

the appropriate school in his or her attendance area or

zone, each ruled in favor of the constitutionality of such

plans, even though some of the attendance areas or zones

were populated, as a result of housing patterns in the

community, with people of one race. In addition, the

Congress and the President of the United States, through

the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, placed

their approval on the holding of the Court of Appeals for

the Seventh Circuit in Bell v. School City of Gary, Ind.,

324 F. 2d 209 (certiorari denied 377 U.S. 924, 12 L. Ed.

2d 216) wherein the fact of de facto segregation which

fortuitously resulted from housing patterns was held not

to invalidate a school system developed on the neigh

borhood school plan, honestly and conscientiously con

4

structed with no intention or purpose to segregate the

races.

Yet despite the fact that when this Court spoke in

Brown of attendance areas, it said that such areas should

be “compact units” constructed “within the limits set by

normal geographic school districting,” and when it spoke

in Brown of the type of school system which should be

created, it said that such system should be “a system not

based on color distinctions,” and when it spoke in Brown

of admission policies which should be achieved, it said

that admissions of children to public schools should be

on “a nonracial basis,” and despite the fact that the thrust

of Bell—“which was that if school districts were drawn

without regard to race, . . . those districts are valid even

if there is racial imbalance caused by discriminatory prac

tices in housing”—was written into the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, and despite the provisions of Sections 401, 407

and 410 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, wherein school

districts were authorized to assign students according to

their residences and courts were prohibited from shifting

students in order to achieve racial balance, the Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, relying on “ freedom-of-

choice” cases, ruled in this case that petitioners’ zone lines

should be gerrymandered in order to alleviate racial im

balance resulting from housing patterns and that “ if there

are still all-Negro schools, or only a small fraction of

Negroes enrolled in white schools, . . . then, as a matter

of law, the existing plan fails to meet constitutional stand

ards as established in Green and its companion cases.”

The questions presented for review are:

1. Whether de facto segregation which occurs fortui

tously because of housing patterns renders an otherwise

acceptable desegregation plan unconstitutional.

5

2. Whether a school district can be required to gerry

mander its attendance area or zone lines so as to include

pupils of a certain race within an attendance area or zone,

who would not be included therein if its attendance area

or zone lines were drawn in a reasonable, rational and

nonracial fashion.

3. Whether the courts, in view of the provisions of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, have authority to issue orders

seeking to achieve a racial balance in neighborhood schools.

4. Whether the constitutionality of an attendance

area or zone plan should be judged by the requirements

of decisions dealing with “freedom-of-choice” plans.

THE CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS AND

STATUTES INVOLVED

This case involves the pertinent parts of the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States—

“ . . . No State shall make or enforce any law

which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of

citizens of the United States; . . . nor deny to any

person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of

the laws.”

It also involves the pertinent parts of Section 401 of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C. §2QQ0c.)—

“ ‘Desegregation’ means the assignment of students

to public schools and within such schools without re

gard to their race, color, religion, or national origin,

but ‘desegregation’ shall not mean the assignment of

students to public schools in order to overcome racial

imbalance.”

And the pertinent part of Section 407 of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C. §2000c-6.1—-

6

. . nothing herein shall empower any official

or court of the United States to issue any order seeking

to achieve a racial balance in any school by requiring

the transportation of pupils or students from one school

to another or one school district to another in order to

achieve such racial balance,..

And Section 410 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42

U.S.C. §2000c-9.)—

“Nothing in this subchapter shall prohibit classi

fication and assignment for reasons other than race,

color, religion, or national origin.”

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This is the first school desegregation case brought in

the Northern District of Mississippi. It was begun April

2,2, 1964, by the filing of a complaint, accompanied by a

motion for a preliminary injunction, wherein respondents,

on behalf of themselves and other Negro children similarly

situated, demanded, among other things—

a) the end of all racial designations and consid

erations in the budgets, expenditures, programs, pol

icies and plans of the school district;

b) the establishment of school zones or attend

ance areas on a nonracial basis; and

c) the assignment of pupils to the schools of the

school district on a nonracial basis.

Jurisdiction was invoked pursuant to the provisions

of 28 U.S.C. §1343 (3), 42 U.S.C. §1983, and the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

Petitioners did not question the right of respondents

to such relief. To the contrary, in order to acquaint them

selves with the requirements respecting such relief, they

employed the writer as their attorney and sought his advice

7

about the requirements of Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U.S. 483, 98 L. Ed. 873; 349 U.S. 294, 99 L. Ed. 1083, and

the cases which had followed in its wake (R. 203). They

were advised by him that Brown required the cessation

of the practice of segregating children solely on the basis

of race and the achievement of a system of determining

admissions to the schools of the district on a nonracial basis

(R. 203), and that in the pursuit of those objectives the

Constitution and the cases required them to discard all

considerations of race and to treat the pupils of the district

as individuals—neither as Negroes nor whites (R. 203, 205).

On the basis of such advice, petitioners thereupon un

dertook to provide respondents with the relief to which

they were entitled under Broivn, and to do so in the manner

spelled out by this court in Brown. That meant, of course,

the choice of desegregating the schools of the district by

the establishment of attendance areas or zones, rather than

through the dubious but more popular “freedom-of-ehoice”

method (R. 205).

Then, having chosen to establish attendance areas or

zones, petitioners proceeded to the fixing of the boundary

lines. That, of course, required a consideration of the way

the district is laid out and the location of its schools (R.

209, 210).

Clarksdale is a town of approximately 25,000 inhabi

tants. It is bisected by the railroad tracks of the Illinois

Central Railroad Company which run in an easterly and

westerly direction from the northeastern to the south

western corner of the town, dividing it into approximately

equal northerly and southerly halves (R. 213, 214). Ac

centuating the division of the residential areas of the town

made by those railroad tracks is the fact that throughout

a good portion of the town the lands adjacent to both the

northerly and southerly side of those railroad tracks are

8

occupied by commercial and industrial establishments. Also

adding to such division is the fact that those railroad

tracks, located as they are in a town situated in the flat

lands of the Yazoo-Mississippi Delta, are on an embank

ment. With but one exception (which is where Sunflower

Avenue crosses over the tracks), no one can cross those

railroad tracks from one residential area to another except

through an underpass. And throughout the length of those

railroad tracks as they pass through Clarksdale—some three

and a half miles—there are but four underpasses, with but

one west of the Sunflower River and that one right next

to the river. (See maps.)

There is a high school north of those railroad tracks

which is adequate—but not more than adequate—for those

high school pupils who live north of those railroad tracks

(R. 219, 223).

There is a more than adequate high school south of

those railroad tracks which is modern in every particular

—much more so than the high school north of the tracks

—for those high school pupils who live south of those rail

road tracks (R. 219, 221).

There is a junior high school north of those railroad

tracks which is also adequate, although obsolete, for those

junior high school pupils who live north of those railroad

tracks (R. 225).

There was a modern and adequate junior high school

south of those railroad tracks for those junior high school

pupils who live south of those railroad tracks (R. 225).

Now there are two.

In the light of those facts, petitioners reached the ob

vious conclusion that two high school sub-districts and two

junior high school sub-districts should be established,

with those railroad tracks as the dividing line between the

sub-districts. fSeemaps.l

9

The southerly half of the town is bisected almost

equally by the railroad tracks of the Illinois Central Rail

road Company which run in a southerly direction from

Clarksdale to Jackson and are referred to in the plans as

running from Clarksdale to Mattson (R. 210). Those

tracks, which create a southwest quadrant and a southeast

quadrant, are not elevated and one can cross over at grade

level at almost every intersection. About as many pupils

live in the southwest quadrant as in the southeast quadrant.

There are two modern elementary schools in the south

west quadrant of the town which can adequately take care

of the pupils in that neighborhood (R. 227).

There are three elementary schools in the southeast

quadrant of the town—one quite modem—which can ade

quately provide for the pupils in that neighborhood (R.

227).

Since those are the facts with reference to the terri

tory and schools south of the east-west railroad tracks of

the Illinois Central Railroad Company, petitioners reached

the obvious conclusion that two elementary sub-districts

should be established south of those east-west railroad

tracks, with the north-south railroad tracks of the Illinois

Central Railroad Company as the dividing line between

them, and with each of those sub-districts divided into at

tendance areas or zones. They then divided the south

west quadrant into two attendance areas or zones, with an

elementary school in each of those attendance areas or

zones, and they divided the southeast quadrant into three

attendance areas or zones, with an elementary school in

each of those attendance areas or zones. (See maps.)

The northerly half of the town is bisected by the Sun

flower River, but there are many more pupils in the

northerly half of the town west of the river than east of the

10

river, due principally to the fact that the central business

district of the town is in the northerly half of the town east

of the river (R. 216, 228, 230). There are two bridges over

the river in that section of the town (just as there are

two bridges over the river in the southerly half of the

town) which enable those elementary school pupils who

live in the northeast quadrant of the town and north of

First Street to pass over into the northwest quadrant of the

town (which is entirely residential) without passing

through the central business district. (See maps.)

There are three elementary schools in the northwest

quadrant of the town (R. 228). The northeast quadrant

had none, but petitioners’ plans committed them to try to

have one built there in 1966 (R. 228).

With those facts before them, petitioners established

two elementary sub-districts in the northerly half of the

town with Sunflower River as the dividing line between

them; divided the northwest quadrant of the town into

three attendance areas or zones, with an elementary

school located in each of them; and then provided that

those elementary school pupils in the northeast quadrant

of the town (where there was no elementary school) could

—for the present—attend either Oakhurst Elementary

School (the westernmost elementary school in the north

west quadrant) or Eliza Clark School (the northernmost

elementary school in the southeast quadrant) (R. 229, 231).

Thus, by utilizing the obvious and indisputable nat

ural barriers which separate Clarksdale into separate and

distinct neighborhoods as the boundary lines for the vari

ous sub-districts, petitioners established sub-districts de

manded by the topography of the town, the location and

the capacity of the school buildings, the proximity of the

pupils to the school buildings, and the requirements of

good educational practices. They took the same action as

11

they would have taken had all of the pupils of the school

district been white, or all Negro, or had every other resi

dence in the town been occupied by whites and the re

mainder by Negroes. They discriminated against no one.

None of the interior lines dividing the elementary

school districts into separate attendance areas or zones

have ever been seriously questioned with the exception of

the north-south line between what was originally the

E-l-B (Hall) zone and the E-l-C (Clark) zone, which was

originally selected so as to ensure sufficient room at the

Eliza Clark School for those children who lived closest to

it and those children in the E-3-A zone who had to go

there because of a lack of an elementary school in their

home zone (R. 246). Because of its dubious validity as a

dividing line between the two zones, it failed to win ap

proval of the district court. Thereafter, to meet that prob

lem, petitioners proposed what is favorably known as the

“ Princeton Plan” among those active in mixing the races

in the schools. Their proposal called for combining the two

zones into one, to be designated E-l-B, with the two schools

(Hall and Clark) to be administered by one set of adminis

trative officials. Grades one and two would attend Eliza

Clark and grades three, four, five and six would attend

Myrtle Hall (R. 130).

After a hearing, petitioners’ revised plans were ap

proved by the trial court and ordered into effect for the

1966-67 school year (R. 148-149).

Racially, Clarksdale is almost evenly divided between

Negroes and whites, and, of course, as in all other towns

and cities where there is a bi-racial population, there is no

even distribution of the races throughout the community.

A majority of the whites live north of the east-west rail

road tracks. Most of the Negroes live south of those

tracks. But there are sizable areas where the races are

12

mixed. Sub-District S-l and Sub-District J-l both have

a substantial amount of racial mixture in their population.

In Zone E-2-B (Riverton), about half of the area is com

posed of white residences and a considerable proportion

of the population is white. In Zone E-2-A (Booker T.

Washington), there are a few people who are not Negroes.

The original Zone E-l-C (Eliza Clark) was populated en

tirely by whites, but then it was combined with Zone

E-l-B (Myrtle Hall) which is predominantly, but not

entirely populated by Negroes. Zone E-l-A (George

Oliver) has a considerable number of whites among its

predominantly Negro population. By adopting a “neigh

borhood school” plan and requiring all pupils to attend

the school in the zone wherein he or she lives—thus bas

ing their admissions’ policy on residence and not on race—•

and particularly by providing that every white pupil in

a racially mixed neighborhood is assigned by virtue of

his residence to a formerly all-black school, petitioners

met all requirements of Brown and established, as much

as it was within their power so to do, a desegregated

school system which necessarily had to result in integrated

schools if the school children of Clarksdale attend public

schools.

To be specific, under petitioners’ desegregation plan—

The schools of the district were completely

desegregated by the beginning of the 1967-1968 school

year.

The segregation of pupils on the basis of race

has been ended.

Compact attendance areas or zones, with reason

able, rational and natural boundaries have been es

tablished in order to achieve a system of determin

ing admission to the schools of the district on a non-

racial basis.

13

All racial designations have been abolished and

all racial considerations have been abandoned.

All students desiring to take a course not offered

at the school he or she attends but offered at another

school are allowed to transfer to the latter school.

No transfers other than those referred to in the

paragraph immediately preceding this paragraph are

granted.

Petitioners are required to offer an identical cur

riculum at all of the district’s elementary, junior high

and senior high schools; to maintain substantially the

same teacher-pupil ratios for each grade in all of the

district’s schools; to maintain substantially the same

level of expenditures of public funds per pupil at all

of the district’s elementary schools, each of the dis

trict’s junior high schools, and at each of the dis

trict’s senior high schools.

Those requirements—which are a part of the court’s

order of August 10, 1965—make certain that no school

in the district will be inferior to any other school in the

district. But lest this court be misled into believing what

respondents say about what were formerly the Negro

schools of the district, petitioners—with understandable

pride—call attention to these facts:

Every school in the district is fully accredited,

with every so-called Negro school graded AA. (See

Answer to Interrogatory 3G in 2nd Set of Interroga

tories.)

Every school in the district is a member of the

Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. (See

Answer to Interrogatory 3G in 2nd Set of Interroga

tories.) But one other school system in Mississippi

can make that claim.

Every Negro teacher in the system possesses a

Class A or Class AA professional certificate (R. 186).

14

Teacher salaries, pursuant to a program adopted

several years before the beginning of this action, have

been equalized. (See Answer to Interrogatory 8D in

2nd Set of Interrogatories.)

There is no real difference in the courses offered

throughout the system and any course really desired

by pupils in any of the schools is provided. (See

Answer to Interrogatory 3F in 2nd Set of Interroga

tories.)

There is no overcrowding in any of our schools.

The orders of the District Court approving petitioners’

plan and putting it into effect were made and entered

on August 10, 1965, and December 10, 1965. Respondents’

appeal therefrom was argued before the Circuit Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit on May 25, 1966. On March

6, 1969, more than 33 months thereafter, and largely on

the basis of decisions in “ freedom-of-choice” cases, the

Court of Appeals reversed the orders of the District

Court by the order which petitioners pray this Court to

review.

The questions presented for review are unquestion

ably the most important questions in the field of school

law.

REASONS FOR ALLOWANCE OF THE WRIT

There are many reasons why the decision below should

be reviewed by this Court:

First, it is in conflict with the decisions of the

Seventh, Tenth, Fourth and Sixth Circuit Courts of Ap

peals on the same matter.

Second, it decides important questions of federal law

which, if not decided by Brown, has not been, but should

be, settled by this Court.

15

Third, it decides important questions of federal law

in a way which, if those questions were decided by

Brown, as we believe, is in conflict with the applicable

decisions of this Court, particularly those in Brown.

Fourth, it violates the express provisions of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Fifth, it is based on an untenable and erroneous

construction of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States.

Sixth, it does not accord with the applicable decisions

of this Court and the other Circuit Courts of Appeals.

Seventh, it is erroneous and its probable results will

be so mischievous as to make a “ shambles” of public

education throughout the nation.

Brown Directed, As the Means of Achieving the

Desegregation of the Schools of a District, the

Creation of Compact Attendance Areas or Zones

This Court, in Brown, authorized the lower federal

courts to consider—

“ . . . problems related to administration, arising

from the physical condition of the school plant, the

school transportation system, revision of school dis

tricts and attendance areas into compact units to

achieve a system of determining admission to the public

schools on a nonracial basis.” (Emphasis added).

The sort of attendance areas which this court had in

mind was indicated in one of the questions propounded

for reargument as attendance areas resulting from

“normal geographic school districting.”

And those words have been almost unanimously con

strued by the courts as authorization for attendance

16

areas or zones honestly and conscientiously constructed

without regard for race, and as requiring the disapproval

of attendance areas gerrymandered for racial purposes.

Respondents, whose contentions in this case are

voiced by the NAACP, should have no quarrel with that

construction of those words. For in the brief filed by

the NAACP in Brown II, it was stated on page 12:

“The extent of the boundary alterations required,

in the reformulation of school attendance areas on a

nonracial basis, will vary. This is illustrated by the

recent experience in the District of Columbia in re

casting attendance boundaries on a wholly geograph

ical basis. In the neighborhoods where there is little

or no mixture of the races, and where school facilities

have been fully utilized, it was found that the elimina

tion of the racial factor did not work any material

change in the territory served by each school.” (Em

phasis supplied).

Petitioners, in fashioning the plan now before this

Court, have also so construed those words of this Court.

Brown Requires tlie Creation of School Systems

Not Based on Color Distinctions

In Brown II, this Court directed school boards “to

achieve a system of determining admission to the public

schools on a nonracial basis.”

That the systems to be created pursuant to its direc

tions should be free of racial considerations was made clear

by this Court in one of the questions propounded for re

argument when it described the sort of system it desired

as—

“a system not based on color distinctions.”

The “separate but equal” doctrine repudiated in Brown

was, as we all know, the legal basis for segregation. It

17

had its genesis in the majority opinion in Plessy v. Fergu

son, 163 U.S. 537, 41 L. Ed. 256, wherein a Louisiana statute

regulating the privileges of passengers on public carriers

by race was held not to violate the fourteenth amendment.

Its antithesis, i.e., the doctrine that the right of any citizen

to enjoy the privileges of a public institution to which he

is otherwise entitled cannot be made to depend on his race

or color—which Brown established as the law of the land

for all public school districts—was thus expressed in the

dissenting opinion of Mr. Justice Harlan:

“ In respect of civil rights, common to all citizens,

the Constitution of the United States does not, I think,

permit any public authority to know the race of those

entitled to be protected in the enjoyment of such rights.

. . . I deny that any legislative body or judicial

tribunal may have regard to the race of citizens when

the civil rights of those citizens are involved.

“These notable additions to the fundamental law

(the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitu

tion of the U.S.) were welcomed by the friends of

liberty throughout the world. They removed the race

line from our governmental systems.

“There is no caste here. Our Constitution is color

blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among

citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are

equal before the law. . . . The law regards man as man,

and takes no account of his surroundings or of his color

when his civil rights as guaranteed by the supreme law

of the land are involved.”

When the transfer provisions incorporated into the de

segregation plans of the public school systems of Knox

ville, Tennessee, which were based solely on racial factors,

came on for review in Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U.S.

683, 10 L. Ed. 2d 632, this Court, in invalidating them, bor

18

rowed from the language in one of its prior decisions to

say—

“Racial classifications are ‘obviously irrelevant

and invidious.’ ”

And then went on to capsulize a history of those of its

decisions which demonstrated its animosity toward racial

classifications:

. . The cases of this Court reflect a variey of in

stances in which racial classifications have been held

to be invalid, e.g., public parks and playgrounds,

Watson v. Memphis, 373 U.S. 526, 10 L. Ed. 2d 529,

83 S. Ct. 1314 (1963); trespass convictions, where

local segregation ordinances pre-empt private choice,

Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U.S. 244, 10 L. Ed. 2d

323, 83 S. Ct. 1119 (1963); seating in courtrooms,

Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U.S. 61, 10 L. Ed. 2d 195,

83 S. Ct. 1053 (1963); restaurants in public buildings,

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S.

715, 6 L. Ed. 2d 45, 81 S. Ct. 856 (1961); bus ter

minals, Boynton v. Virginia, < 364 U.S. 454, 5 L. Ed.

2d 206, 81 S. Ct. 182 (1960); public schools, Brown

v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 98 L. Ed. 873,

74 S. Ct. 686, 38 A.L.R. 2d 1180, supra; railroad din

ing car facilities, Henderson v. United States, 339 U.S.

816, 94 L. Ed. 1302, 70 S. Ct. 843 (1950); state enforce

ment of restrictive covenants based on race, Shelley

v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1, 92 L. Ed. 1161, 68 S. Ct. 836,

3 A.L.R. 2d 441 (1948); labor unions acting as statu

tory representatives of a craft, Steele v. Louisville &

N, R. Co., 323 U.S. 192, 89 L. Ed. 173, 65 S. Ct. 226,

supra; voting, Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649, 88

L. Ed. 987, 64 S. Ct. 757, 151 A.L.R. 1110 (1944); and

juries, Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303, 25

L. Ed. 664 (1879).”

It followed with a gist of a decision by the Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit:

19

. . The recognition of race as an absolute

criterion for granting transfers which operate only

in the direction of schools in which the tranferee’s

race is in the majority is no less unconstitutional

than its use for original admission or subsequent as

signment to public schools. See Boson v. Rippy, 285

F. 2d 43 (C.A. 5th Cir.).” (Emphasis added).

In that case which this Court cited with approval,

the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit said:

. . Negro children have no constitutional right

to the attendance of white children with them in the

public schools. Their constitutional right to ‘the

equal protection of the laws’ is the right to stand

equal before the laws of the State; that is, to be treated

simply as individuals without regard to race or color.

The dissenting view of the elder Mr. Justice Harlan

in Plessy v. Ferguson, 1895, 163 U.S. 537, 559, 16 S.

Ct. 1138, 1146, 41 L. Ed. 256, has been proved by

history to express the true meaning of our Consti

tution:

“ . . There is no caste here. Our constitution

is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes

among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens

are equal before the law. The humblest is the peer

of the most powerful. The law regards man as man,

and takes no account of his surroundings or of his

color when his civil rights as guaranteed by the su

preme law of the land are involved.’ ”

Many other decisions from this and other courts could

be cited to the same effect, but one will suffice. It is

that of Collins v. Walker, 328! F. 2d 100, wherein the Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ruled that a grand jury

upon which Negroes had been purposely included was as

unconstitutional as one from which they had been pur

posely excluded. The court said:

20

“A Negro is entitled to the equal protection of

the laws, no less and no more. He stands equal be

fore the law, and is viewed by the law as a person,

not as a Negro.”

Hence, as the foregoing cases show, petitioners, in

carrying out the mandate of Brown, which was to admit

children to the schools of the district on a nonracial basis,

were enjoined to disregard the face of every school child

in the district, to look on every pupil simply as a pupil

and not as a white pupil or a Negro pupil. They were ob

liged to come up with the same segregation plan as they

would have produced had all of the pupils of the district

been white, or all colored, or had every other residence

in the district been occupied by whites and every other

been occupied by Negroes. As the record shows, that is

exactly what they did.

De Facto Segregation—Which Occurs Fortuitously Be

cause of Housing Patterns—According to Brown and the

Holdings of the Seventh, Tenth, Fourth and Sixth Cir

cuit Courts of Appeals, Does Not Make an Otherwise

Acceptable Desegregation Plan Unconstitutional.

As we have pointed out, the directives of this Court

for the construction of attendance areas or zones, as set

forth in Brown, are—

First, the attendance areas or zones must be

“ compact units,” and

Second, the system thus created must be “a sys

tem not based on color distinctions.”

Brown necessarily was to the effect that de facto

segregation—that which occurs fortuitously because of

housing patterns—does not make an otherwise acceptable

desegregation plan unconstitutional. For if an area around

a school is inhabited solely by whites or blacks, the ere-

21

ation of the “compact units” required by Brown will nec

essarily result in racially imbalanced attendance areas or

zones. And only by the drawing of zone lines without

regard to color can “a system not based on color consider

ations” be devised. For only if attendance areas or zones

are set up as they should be: through the drawing of rea

sonable, rational and nonracial lines, without regard to the

race of the pupils enclosed thereby, will admissions to the

school of that zone be determined on a nonracial basis,

i.e., the residence of the pupils. But if the boundaries of

the attendance areas or zones must be gerrymandered

so as to include certain pupils within the zone who would

not be included therein if those boundary lines were

drawn in a reasonable, rational and nonracial fashion,

then the admission into the school of the zone of those

pupils artificially brought into the zone will be based on

racial considerations, in defiance of the command of

Brown.

From the very beginning—in fact, in Brown after re

mand to the trial court—it has been held that if attendance

areas or zones are fairly arrived at, and all children living

in each attendance area or zone are required to attend the

school in that area or zone, no violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment results even though the concentration of chil

dren of one race in particular areas or zones results in

racial imbalance in the schools. Brown v. Board of Educa

tion of Topeka, 139 F. Supp. 468. To quote from the trial

court’s opinion:

“It was stressed at the hearing that such schools

as Buchanan are all-colored schools and that in them

there is no intermingling of colored and white chil

dren. Desegregation does not mean that there must be

intermingling of the races in all school districts. It

means only that they may not be prevented from

intermingling or going to school together because of

race or color,

22

“If it is a fact, as we understand it is, with respect

to Buchanan School that the district is inhabited en

tirely by colored students, no violation of any constitu

tional right results because they are compelled to at

tend the school in the district in which they live.”

At least four Courts of Appeals have reached the same

conclusion. The Seventh, in Bell v. School City of Gary,

Ind., 324 F. 2d 209 (certiorari denied 377 U.S. 924, 12 L. Ed.

2d 216), which first appeared in 213 F. Supp., at page

819, was presented the question whether the schools of

Gary, with some having all-white and some all-colored

student bodies, met the requirements of Brown. After

pointing out that the composition of those student bodies

was the result of the concentration of the city’s Negroes

in certain sections, the court added:

“ Plaintiffs argue that Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, 347 U.S. 483, 74 S. Ct. 686, 98 L. Ed. 873, pro

claims that segregated public education is incompatible

with the requirements of the Fourteenth Amendment

in a school system maintained pursuant to state law.

However, the holding in Brown was that the forced

segregation of children in public schools solely on the

basis of race, denied the children of the minority group

the equal protection of the laws granted by the Four

teenth Amendment.

“We approve . . . the statement in the District

Court’s opinion, ‘Nevertheless, I have seen nothing in

the many cases dealing with the segregation problem

which leads me to believe that the law requires that

a school system developed on the neighborhood school

plan, honestly and conscientiously constructed with

no intention or purpose to segregate the races, must

be destroyed or abandoned because the resulting effect

is to have a racial imbalance in certain schools where

the district is populated almost entirely by Negroes

or whites. * * ”

23

The Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals reached the same

conclusion in Downs v. Board of Education of Kansas City,

336 F. 2d 988 (certiorari denied 380 U.S, 914, 13 L. Ed. 2d

800), which involved a broad attack on the administration

of the Kansas City, Kansas, school system, and particularly

on the action of the school board in defining school bound

ary lines and requiring students to attend the school in

the district in which they lived, with the result that some

of the schools were all-white and some all-Negro. But,

said the court:

“The neighborhood school system and other school

systems, by which admission to the school is deter

mined upon the basis of similar criteria such as res

idence and aptitude, are in use in many parts of the

country. . . . In the second Brown case, supra, the

Supreme Court appears to have recognized that school

admissions may be based upon such factors as res

idence. It said that in determining ‘good faith com

pliance at the earliest practicable date,’ the lower

courts might take into account problems arising from

the * * revision of school districts and attendance

areas into compact units to achieve a system of de

termining admission to the public schools on a non-

racial basis * * *.

“The drawing of school zone lines is a discretion

ary function of a school board and will be reviewed

only to determine whether the school board acted ar

bitrarily.

“We conclude that the decisions in Brown and

the many cases following it do not require a school

board to destroy or abandon a school system developed

on the neighborhood school plan, even though it re

sults in a racial imbalance in the schools, where, as

here, that school system has been honestly and con

scientiously constructed with no intention or purpose

to maintain or perpetuate segregation.”

24

The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals reached the same

conclusions in Gilliam v. School Board of the City of Hope-

well, Va., 345 F. 2d 325, which involved a neighborhood

school plan which inevitably resulted in some all-Negro

schools because of “ the fact that the surrounding res

idential areas are inhabited entirely by Negroes.” In re

jecting the objections thereto, the court said:

“The plaintiffs object that the result of the geo

graphic zoning is a large measure of de facto segrega

tion. It is true that it is, but this is because of the

residential segregation that exists. The Harry E.

James School zone, for instance, bounded in part by

Hopewell’s city limits, is otherwise largely surrounded

by railroad classification yards and industrial tracks,

with adjacent industrialized areas, which isolate the

residential portions of that zone from all other res

idential areas. De facto segregation could be avoided

for those pupils only by transporting them to distant

schools.

“The Constitution does not require the abandon

ment of neighborhood schools and the transportation

of pupils from one area to another solely for the pur

pose of mixing the races in the schools.”

Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education, 369 F. 2d 55,

decided by the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals on Decem

ber 6, 1966, is also to the same effect. In it, the appel

lants posed the question—

“Whether the neighborhood system of pupil place

ment, fairly administered without racial bias, comports

with the requirements of equal opportunity if it

nevertheless results in the creation of schools with

predominantly or even exclusively Negro pupils.”

In responding, the court said:

“The neighborhood system is in wide use through

out the nation and has been for many years the basis

25

of school administration. This is so because it is

acknowledged to have several valuable aspects which

are an aid to education, such as minimization of safety

hazards to children in reaching school, economy of

cost in reducing transportation needs, ease of pupil

placement and administration through the use of

neutral, easily determined standards, and better home-

school communication. The Supreme Court in Brown

recognized geographic districting as the normal

method of pupil placement and did not foresee chang

ing it as the result of relief to be granted in that

case.

“Because of factors in the private housing market,

disparities in job opportunities, and other outside in

fluences (as well as positive free choice by some Ne

groes), the imposition of the neighborhood concept

on existing residential patterns in Cincinnati creates

some schools which are predominantly or wholly of

one race or another. Appellants insist that this situa

tion, which they concede is not the case in every

school in Cincinnati, presents the same separation and

hence the same constitutional violation condemned

in Brown. We do not accept this contention. The

element of inequality in Brown was the unnecessary

restriction on freedom of choice for the individual,

based on the fortuitous, uncontrollable, arbitrary fac

tor of his race. The evil inherent in such a classifica

tion is that it fails to recognize the high value which

our society places on individual worth and personal

achievement. Instead, a racial characterization treats

men in the mass and is unrelated to legitimate gov

ernmental considerations. It fails to recognize each

man as a unique member of society.

“ In the present case, the only limit on individual

choice in education imposed by state action is the use

of the neighborhood school plan. Can it be said that

this limitation shares the arbitrary, invidious char

acteristics of a racially restrictive system? We think

26

not. In this situation, while a particular child may

be attending a school composed exclusively of Negro

pupils, he and his parents know that he has the choice

of attending a mixed school if they so desire, and they

can move into the neighborhood district of such a

school. This situation is far removed from Brown,

where the Negro was condemned to separation, no

matter what he as an individual might be or do.

Here, if there are obstacles or restrictions imposed

on the ability of a Negro to take advantage of all the

choices offered by the school system, they stem from

his individual economic plight, or result from private,

not school, prejudice. We read Brown as prohibiting

only enforced segregation.” (Emphasis supplied).

The Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, on February 10th

of this year, reaffirmed its holding in Deed. In Goss v.

Board of Education, City of Knoxville, Tennessee, 406

F. 2d 1183, it had this to say of a plan which required each

student to be assigned to the school in the district in which

he or she resides:

“Preliminarily answering question I, it will be

sufficient to say that the fact that there are in Knox

ville some schools which are attended exclusively or

predominantly by Negroes does not by itself estab

lish that the defendant Board of Education is violat

ing the constitutional rights of the school children of

Knoxville. Deal v. Cincinnati Bd. of Education, 369

F. 2d 55 (6th Cir. 1966), cert, denied, 389 U.S. 847,

88 S. Ct. 39, 19 L. Ed. 2d 114 (1967); Mapp. v. Bd. of

Education, 373 F. 2d 75, 78 (6th Cir. 1967). Neither

does the fact that the faculties of some of the schools

are exclusively Negro prove, by itself, violation of

Brown.”

And there are comparatively recent district court

cases from the Fifth Circuit to the same effect. Griggs v.

Cook, 272 F. Supp. 163 (N.D. Georgia, July 21, 1967), af

firmed by the court in 384 F. 2d 705, clearly recognizes

2?

that there is nothing unconstitutional or illegal about

fortuitous de facto segregation. We quote:

. . the sole question here is whether the loca

tion of a neighborhood school, ipso facto, is uncon

stitutional, because it will result in a predominantly

all-negro enrollment. Short of racially motivated ac

tion in the manipulation of attendance patterns or

‘gerrymandering’ of school districts, and prior to Jef

ferson County, the matter appeared to be at rest un

der such cases as Bell v. School City of Gary, 213

F. Supp. 819 (N.D. Ind. 1963), aff’d 324 F. 2d 209

(7th Cir. 1963), cert. den. 377 U.S. 924, 84 S. Ct. 1223,

12 L. Ed. 2d 216 (1964), and Briggs v. Elliott, 132

F. Supp. 776 (E.D.S.C. 1955); Holland v. Board of

Public Instruction, 258 F. 2d 730 (5th Cir. 1958);

Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education, 369 F. 2d 55

(6th Cir. 1966).

“ The dilemma arises from the legal application

of a decree directed at de jure situations upon facts

which plaintiffs themselves assert are de facto prob

lems. It is apparent to all that the difficulty here arises

out of residential racial patterns in the City of At

lanta. That such residential segregation actually pro

duces educational segregation and renders the task

of school integration extremely difficult is obvious.

However, it is impossible for the court in this action to

abolish the Atlanta housing problem by judicial solu

tion of the school problem. Such result must await

effective legislation and social maturity on the part

of many parties not remotely concerned with this suit.

“ . . . What is decided is that the establishment

of a school on nonracially motivated standards is not

unconstitutional because it fortuitously results in all

negro or all-white enrollment.”

28

In Moses v. Washington Parish School Board, 276

F. Supp. 834 (E.D. La., Oct. 26, 1967), it was said:

“ . . . This Court’s considered position is that

separation which occurs fortuitously is not ‘inherently’

unequal.

. . this Court cannot sanction a rule of law

which places the legal burden on the state to correct

the effects on one class of individuals of chance occur

rences or of the free exercise by another group of their

rights of free association.”

Broussard v. Houston Independent School District, 395

F. 2d 817, decided May 30, 1968, by a three-judge court,

rejected the contention that the construction of new schools

should be halted because they might promote and per

petuate de facto segregation in the schools.

“ The Constitution does not require such a result,

and we entertain serious doubt that it would permit

it. Racial imbalance in a particular school does not

in itself, evidence a deprivation of constitutional rights.

Zoning plans fairly arrived at have been consistently

upheld, though racial imbalance might result.”

We live in a pluralistic society. Our communities are

as diverse as the races and the ethnic groups which popu

late them. All-white communities abound in sections out

side the South. A few all-Negro communities can be found

in the South. Towns made up of French-speaking citizens

exist in Louisiana. Scandinavian groups compose com

munities located in the Mid-West. Perhaps the same can

be said about German and Italian groups. For this country

has provided a refuge for those of every race and nation

ality, with no restrictions on where they should settle.

And since like attracts like, our various racial and ethnic

29

groups have inevitably moved into those communities

which numbered among their inhabitants those of their

own group and have shunned those communities which do

not have those of their background. For instance, while

Mississippi has, along with its many Anglo-Saxons, those

of German and Italian stock, it has no Scandinavians or

Poles. It has Chinese but not Japanese. And other il

lustrations could be given.

Where communities have sizable racial or ethnic

groups, those groups tend to congregate in identifiable

sections of their community. In parts of Boston, none

but Irish can be found. The same can be said of New

York, which also includes sections composed exclusively

of Italians. In San Francisco, Chinese have their own

part of the city. Those are but examples of a phenomena

well known to those familiar with American communities.

Other such examples can easily be given.

Negroes have the same tendencies as the white groups.

Where they form a sizable proportion of the population,

whether it be in the South, North, East or West, they nat

urally, and of their own volition, create their own neigh

borhood. It can be safely said that there is not a com

munity in this country where Negroes, if there are enough

of them, do not congregate into a particular section of their

community. The instincts which motivate their white

counterparts to do so, also impel Negroes to live together.

Such de facto segregation as exists in Clarksdale is,

of course, the fortuitous result of the housing patterns in

the community. But those housing patterns did not result

from any state law or local ordinance, as did the housing

patterns in the community under consideration in Holland

v. Board of Public Institutions, 258 F. 2d 730. The fact of

the matter is that they are the result of the natural desires

of people to live near those of their own kind.

30

There is some de facto segregation in Clarksdale, just

as there is in every community in this nation where there

is a sizable proportion of Negro population. Given the

housing patterns which prevail in towns and cities through

out the country, any other result would be inconceivable.

But the de facto segregation found in Clarksdale is

fortuitous de facto segregation and not the result of any

law or ordinance. It is, in every essential respect, the same

type of de facto segregation as prevails in Gary, Indiana,

which was before the court in Bell; as prevails in Kansas

City, Missouri, which was before the court in Downs; as

prevails in Hopewell, Virginia, which was before the court

in Gilliam; as prevails in Cincinnati, Ohio, which was be

fore the court in Deal; as prevails in Knoxville, Tennes

see, which was before the court in Goss v. Board of Edu

cation, City of Knoxville, Tennessee, 406 F. 2d 1183; as

prevails in Houston, Texas, which was before the court in

Broussard v. Houston Independent School District, 262 F.

Supp. 266; as prevails in Atlanta, Georgia, which was be

fore the court in Griggs v. Cook, 272 F. Supp. 163, 384 F.

2d 705; as prevails in Washington Parish, Louisiana, which

was before the court in Moses v. Washington Parish School

Board, 276 F. Supp. 834; and as prevails in numerous other

communities whose plans have been validated by the

courts even though they encompassed areas where de

facto segregation prevailed.

Where such de facto segregation exists, and a district’s

zones are set up as they should be: through the drawing

of reasonable, rational and nonracial lines, without regard

to the race of the pupils enclosed thereby, there will be, of

necessity, some all-black and some all-white schools.

There is no escape from such an inevitable result, except

the racist solution advanced by the court below. But

neither race, nor religion, should be acknowledged as con

stituting in any way a valid condition or measure, in this

31

nation, of a person’s access to public facilities, positions or

activities of any sort. Those who would make it such ought

to be rejected with finality because, in racial matters, en

during progress and justice will come about only under

rules of law which unswervingly treat all men as equal

before the law, regardless of race, color or national origin.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 Validates Bona Fide

Neighborhood School Lines and Prohibits Court

Orders Intended to Alleviate Racial Imbalance in

Neighborhood Schools

As we have pointed out, Bell v. School City of Gary

holds that de facto segregation which occurs fortuitously

because of housing patterns is not unconstitutional. Now

we point out that the gist of that holding was incorporated

into the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This is clear from the

language of Senator Humphrey, floor manager of the bill,

as quoted in Jefferson 1 (372 F. 2d 836):

“ Senator Humphrey explained:

“ ‘Judge Beamer’s opinion in the Gary case is sig

nificant in this connection. In discussing this case,

as we did many times, it was decided to write the

thrust of the court’s opinion into the proposed sub

stitute.’ (Emphasis added).

“ ‘The bill does not attempt to integrate the schools,

but it does attempt to eliminate segregation in the

schools. The natural factors, such as density of

population, and the distance that students would

have to travel are considered legitimate means

to determine the validity of a school district, if

the school districts are not gerrymandered, and

in effect deliberately segregated. The fact that there

is a racial imbalance per se is not something which

is unconstitutional. That is why we have attempted

to clarify it with the language of Section 4.’ (Em

phasis added).”

32

The pertinent provisions of the Civil Rights Act of

1964 are, of course, Sections 401, 407 and 410, which read

as follows:

“ Sec. 401. As used in this title—

“ (b) ‘Desegregation’ means the assignment of

students to public schools and within such schools

without regard to their race, color, religion, or national

origin, but ‘desegregation’ shall not mean the assign

ment of students to public schools in order to over

come racial imbalance.

“ Sec. 407 .. .

“ . . . nothing herein shall empower any official

or court of the United States to issue any orders seek

ing to achieve a racial balance in any school by re

quiring the transportation of pupils or students from

one school to another or one school district to another

in order to achieve such racial balance.

“Sec, 410.

“Nothing in this title shall prohibit classification

and assignment for reasons other than race, color,

religion, or national origin.”

In defining the latter part of Section 401—

“but desegregation shall not mean the assign

ment of students to public schools in order to over

come racial imbalance,”

the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, in Jefferson 1,

said:

“The negative portion, starting with ‘but’, ex

cludes assignment to overcome racial imbalance, that

is acts to overcome de facto segregation.”

33

In support of its conclusion that the prohibition in

Section 407 against assignment of students to overcome

racial imbalance was related solely to racial imbalance

resulting from de facto segregation, the Court, in Jefferson

1, went on to say this about the undefined term “racial

imbalance” :

“ It is clear however from the hearings and de

bates that Congress equated the term, as do com

mentators, with ‘de facto segregation’ that is, non-

racially motivated segregation in a school system

based on a single neighborhood school for all children

in a definable area.”

In recognition of the fact that “classification and as

signment for reasons other than race, color, religion, or

national origin,” as used in Section 410, includes classi

fication and assignment on the basis of residence, the

Court, in Jefferson 1, said:

“The thrust of the Gary case (Bell) was that if

school districts were drawn without regard to race, but

rather on the basis of such factors as density of popu

lation, travel distances, safety of the children, costs of

operating the school system, and convenience to par

ents and children, those districts are valid even if there

is a racial imbalance caused by discriminatory prac

tices in housing.”

When the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit de

cided in Jefferson 1, as it had to do, that the thrust of Bell

had been written into the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and that

the Act applies, at the very least, to those school districts

whose zone lines are drawn without regard to race, but

rather on the basis of such factors as density of popula

tion, travel distances, safety of the children, cost of operat

ing the school system, and convenience to parents and chil

dren, it decided, beyond all question, that the Act applies

to the Clarksdale Municipal Separate School District. For

34

petitioners’ zones are set up exactly as were the zones in

Bell.

It follows therefore, from the decision in Jefferson 1

and the express words of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, that

petitioners’ attendance areas or zones are valid even if

there is a racial imbalance therein and that the court was

without authority to issue any order designed to achieve

a racial balance in petitioners’ schools.

The Constitutionality of an Attendance Area Desegre

gation Plan is to Be Judged by the Decisions in Those

Cases Dealing with Such Plans. It Is Not to Be Judged

by Decisions Dealing with “Freedom-of-Choice” Plans,

for Those Decisions Are Based on Considerations

Foreign to Attendance Area Plans.

The plan before the court is unique in that no other

school district in the Fifth Circuit has initially proposed to

do exactly that which is required by Brown, to-wit: to

abolish its dual zone lines, to revise its attendance areas

into compact units, and to establish a system of determining

admissions to its schools on a nonracial basis, without in

cluding in its proposal an escape provision whereby a white

pupil in a predominantly black neighborhood could avoid

the school for that zone and attend a school designated for

a different zone. As Judge Tuttle put it in Davis v. Board

of School Commissioners of Mobile County, 364 F. 2d 896—

“As every member of this court knows, there are

neighborhoods in the South and in every city of the

South which contain both Negro and white people. So

far as has come to the attention of this court, no Board

of Education has yet suggested that every child be re

quired to attend his ‘neighborhood school’ if the neigh

borhood school is a Negro school. Every board of ed

ucation has claimed the right to assign every white

child to a school other than the neighborhood school

under such circumstances.”

35

Judge Tuttle simply didn’t know about the plan now before

this court, which was then before another panel of his

court.

In the plan before the court every pupil is required

to attend the school in his or her zone with the exception

that students desiring to take a course not offered at the

school he or she attends but offered at another school are

allowed to transfer to the latter school. That exception is

nullified for all practical purposes by the requirement that

identical curriculum be offered at all of the district s ele

mentary, junior high and senior high schools. During the

five years the plan has been in operation, not a single white

pupil has taken advantage of that exception, nor been ex

cused from his or her initial assignment under the plan.

In sum, the plan before the court has no transfer provi

sions such as that which led this court to equate the plan

in Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of the City of Jack-,

son, Tennessee, 391 U.S. 450, 20 L. Ed. 2d 733, with a free-

dom-of-choice” plan, and no gimmick such as those re

ferred to by Judge Tuttle in Davis.

Since the plan before the court is a bona fide attend

ance area plan, and uncontaminated with “ freedom-of-

choice” provisions, it should, we submit, be judged by the

decisions in those cases dealing with attendance area plans.

In particular, it should be judged by what this court said

in Brown, for what this court had in mind when deciding

Brown was the organization and operation of school dis

tricts by the establishment of attendance areas, with single

rather than dual lines, and with admissions determined by

the residences of the pupils.

Of course, primarily Brown called for the achievement

of a system of determining admissions to the public schools

on a nonracial basis. But it contemplated that such result

would be obtained through revision of school districts and

36

attendance areas into compact units. For it directed the

lower courts to consider, in determining whether a school

district’s efforts were consistent with good faith compli

ance at the earliest possible date,

“problems related to administration, arising from the

physical condition of the school plant, the school trans

portation system, personnel, revision of school districts

and attendance areas into compact units to achieve a

system of determining admission to the public schools

on a nonracial basis.” (Emphasis supplied).

At the time Brown was decided, pupils everywhere

were required to attend their neighborhood school. Hence

it is certain that what Brown contemplated was the elim

ination of dual zone lines and the drawing of single zone

lines around each school, with the new attendance areas

to be the “compact units” which result from “normal geo

graphic school districting,” coupled with the requirement

that every pupil be required to attend that school located

in the zone of his residence. The resulting school systems

would not be based on “ color distinctions.” Districts so

organized and operated would have a system of deter

mining admissions on a nonracial basis.

What we have just said was better said in Moses v.

Washington Parish School Board, 276 F. Supp. 834:

“ . . . One need not go back more than three or four

years in time to find the school systems in the South

operating, along with those in the rest of the nation,

smoothly and efficiently. In the days before the im

pact of the Brown decision began to be felt, pupils were

assigned to the school (corresponding, of course, to the

color of the pupils’ skin) nearest their homes; once

the school zones and maps had been drawn up, nothing

remained to be done but to inform the community of

the structure of the zone boundaries. Upon the rendi

tion of the Brown decision and the issuance of the ulti

matum to abolish the segregated dual zones in each

37

school district, it was natural for the citizenry to ex

pect to see the old coterminous dual zones abolished,

and single independent zones drawn up around each

school in each district.”

After Brown was decided, most Southern school dis

tricts took the first step required by that decision, i.e,, the

elimination of their dual zone lines. But practically none

of them took the second step required, i.e., the establish

ment of single zone lines around each school, so as to cre

ate new compact units as attendance centers. Instead, the

idea which culminated in the “ freedom-of-choice plan ap

peared on the scene and was embraced as an excuse for not

meeting the second requirement of Brown.

Beyond peradventure, the “ freedom-of-choice”

method of operating schools was not that called for by

Brown. Equally clear was the fact that “ freedom-of-

choice” is a “haphazard” way of administering a school

system. Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

District, 355 F. 2d 865. “When attempted on a permanent

basis,” according to Moses, “ the system becomes so un

workable as to be ridiculous. But its real defect, as

viewed by the courts, was that it transferred the burden

of achieving a system of admissions to public schools on a

nonracial basis from the school boards, where the courts

felt it belonged, to the parents of black pupils, and that

the parents of black pupils, in the opinion of the courts,

were so conditioned by their heritage that they were in

capable of exercising their choices in a free and unfettered

manner. Hence the usefulness of “ freedom-of-choice”

plans had to be limited to the interim period required for

the transition to a school system impartially zoned on a

geographic and nondiscriminatory basis. In other words,

school districts were simply given the privilege of op

erating under “ freedom-of-choice” plans for a limited pe

38

riod. They never had the right so to operate their schools.

To quote from Moses again:

“Obviously there is no constitutional ‘right’ for

any student to attend the public school of his own

choosing. But the extension of the privilege of choos

ing one’s school, far from being a ‘right’ of the

students, is not even consistent with sound school

administration.”

The question presented in cases involving “ freedom-