Daly v. Darby Township, PA School District Brief for Appellee-Intervenors

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Daly v. Darby Township, PA School District Brief for Appellee-Intervenors, 1968. 9486d8e5-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0a9b3139-f6c6-4be2-8d87-67dfc983d5ff/daly-v-darby-township-pa-school-district-brief-for-appellee-intervenors. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

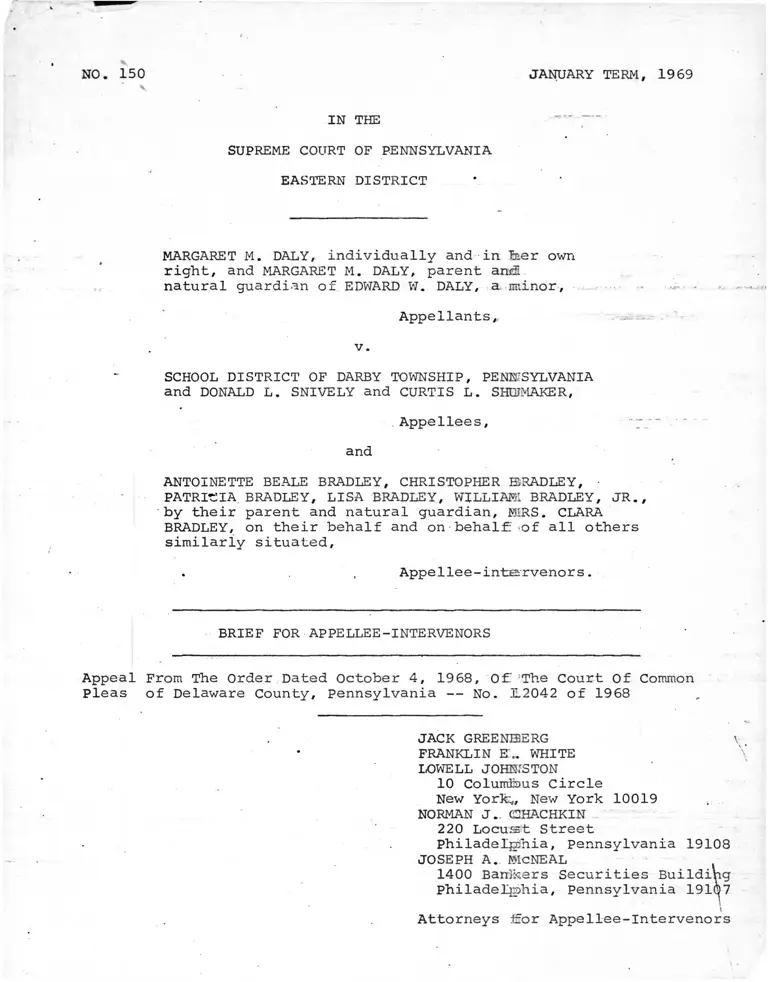

NO. 150 JANUARY TERM, 1969

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF PENNSYLVANIA

EASTERN DISTRICT

MARGARET M. DALY, individually and in feer own

right, and MARGARET M. DALY, parent and!

natural guardian of EDWARD W. DALY, a minor,

Appellants,

v.

SCHOOL DISTRICT OF DARBY TOWNSHIP, PENNSYLVANIA

and DONALD L. SNIVELY and CURTIS L. SHQIMAKER,

Appellees, ~p_

and

ANTOINETTE BEALE BRADLEY, CHRISTOPHER BRADLEY, •

PATRICIA BRADLEY, LISA BRADLEY, WILLIAM BRADLEY, JR.,

by their parent and natural guardian, M1RS. CLARA

BRADLEY, on their behalf and on behalf of all others

similarly situated,

. , Appel lee-intervenors.

BRIEF FOR APPELLEE-INTERVENORS

Appeal From The Order Dated October 4, 1968, Of The Court Of Common

Pleas of Delaware County, Pennsylvania -- No. 312042 of 1968

JACK GREENBERG

FRANKLIN E„ WHITE

LOWELL JOHNSTON

10 Columibus Circle

New Yorlc,, New York 10019

NORMAN J.. (CHACHKIN

220 Locust Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19108

JOSEPH A. McNEAL

1400 BanHcars Securities Building

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19107

Attorneys for Appellee-Intervenors

STATEMENT OF THE QUESTIONS INVOLVED

I. Whether appellants have standing to prosecute an appeal

from an injunctive order directed at the School Board,

where compliance with such order by the Board would

violate no statutory or constitutional rights of

appellants.

II. Whether an equity court may, upon the oral motion of a

party, incorporate into an order an agreement reached by

where

the participation and consent of all parties,/all parties

consented to the incorporation and where in its judgment

incorporation would materially further the orderly

resolution of the dispute. j

III. Whether 43 P.S. §962(b) (Section 12 of the Pennsylvania Human

Relations Act) barred the lower court from accepting juris

diction over the subject matter.

HISTORY OF THE CASE

This is an appeal from an order denying a request to enjoin

the School Board of the School District of Darby Township from

implementing a resolution, adopted September 12, 1968, requiring

the integration of its two elementary schools on a ratio of two

black pupils to one white pupil (48a) and directing the board to

integrate the schools according to a specified pairing system.

1. The Pleadings

On September 19, 196,8, • appellant Margaret M. Daly, & Vhite -- -

taxpayer and parent of a child enrolled in the Darby Township

Elementary School — one of the District's two such schools —

filed, in the Court of Common Pleas of Delaware County, a Petition)

for a Preliminary Injunction seeking to restrain the School Dis-

[

trict of Darby Township from acting upon or implementing the

aforesaid resolution. The Petition named as defendants•the School

District, its Superintendent, Donald L. Snively and Curtis L.

Shumaker, Principal of the Darby Township Elementary School. It

alleged that the proposed ratio for the assignment of pupils con

stituted a specified distinction of pupils by reason of race or

color, and. as such, was in violation both of.the Pennsylvania

Public School Code and of the constitutional rights of Mrs. Daly's

child (2a). A Rule to Show Cause why the Preliminary Injunction

should not be issued was granted that same day by President Judge

Henry G. Sweeney (9a) and a hearing was scheduled for September

24, 1968.

: ~0n. September 24, 1968, the School .District filed an answer ...

denying the essential allegations* of the petition (10-12a) . That

same day, Clara Bradley, a Negro taxpayer and resident of Darby

Township filed, on behalf of five of her minor children, all of

whom attended Darby Township schools, a petition for leave to

1/intervene as parties-defendant (13-15a). The petition alleged that

the issuance of the injunction sought by the white plaintiffs

against the School District's plan would deny intervenors' right

"to equal educational opportunity £ree from radial discrimination

or s.egregation" guaranteed by the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments

to -the'Constitution of the United States (13a). At the hearing - the' "

Chancellor orally granted the pe tition to intervene and subsequently

signed an order to that effect (17a).

2. Background of the Litigation

This litigation is but the latest in a long series of attempts

to desegregate the public schools of Darby Township.

Darby Township is a small school district enrolling approximately

1800 students. As is evident fron> the record, Negro students outnumber

whites by two to one. The district maintains but three schools, two

elementary — Darby Township Elementary, Studevan Elementary — and one

high school, the Darby Township Junior-Senior High School.

The intervention petition stated that it was also brought

"on behalf of the black community of Darby Township, and Qn

behalf of all black pupils residing in the lower (southeastern)

portion of Darby Township who attend or are eligible.to attend

[Darby Township] schools . . . (14a)."

2

The district is in two non-contiguous parts which are separated

by the virtually all-white boroughs of Glenolden and Sharon Hill

(51a).

Although both whites and Negroes reside in the northern part,

the southeasterly portion is heavily or exclusively Negro. Through

the close of the 1967-68 school year, the'district, assigned elementary

children to their nearest school. As a consequence* the Darby

Township Elementary School located in the northern half enrolled both

Negro and white children, while the Studevan school -in the southeasterly

portion enrolled only Negro students. No whites have attended

2/

Studevan for several years.

In February 19 6 8, the township was directed by -the Human.

Relations Commission to submit no later than July 1, 1968, a plan

to eliminate the racial imbalance existing in the elementary schools.

The District failed to submit a plan but obtained an extension of time

to April 1969, in which to do so. Responding to the failure of the

School Board to come forward with a plan, and reacting to 'the1 prospect

of another y§ar of segregated education for their children, parents

of Negro children assigned to Studevan School protested -t?o school

officials and demonstrated to publicize their demands that Studevan

be integrated. In an effort to ease” the mounting tension and

Although some of these background facts are not in the record,

their omission does not mean they were not considered. Proof of

them became unnecessary in view of the way .the litigation pro

gressed in the lower court. But the Chancellor was well aware of

them (51a). We include them merely to provide this Courtswith

the full picture of the situation then before the Chancellor.

They are known to the appellants and, we believe, are not in

dispute.

3

dee ning turmoil dividing the community, the Board met several times

and. adopted a resolution to integrate fully both elementary schools

for the 1968-69 school year. The resolution, challenged below,

provided that integration would be effected by assigning pupils to

each grade of each school in a ratio of two Negro puphls to each

white pupil (48a).

3. The Initial Hearing

At the hearing, after, very brief testimony by appellant,

Margaret M. Daly, it became, apparent that appellants' primary objec- —

tion was to the particular manner of integration incorporated in the

2/ -2/resolution - the formula of two to one (3a). The Chancellor orally

indicated that he would not interfere with the goal of integrating

Studevan. (41a, 37a) but apparently agreed that the-two to one formula

arrangement was improper (38a). He continued the matter for one week

to give the parties time to explore the possibility of an amicable

settlement (46a).

4. Conference between the parties

■ That same day counsel for the parties met to explore alternative •

ways , of .integrating Studevan. All agreed that the September-12-------

resolution utilizing a tŵ > to one ratio was ill-advised in that it

contained no standards to determine "which" white -children in each

1 /grade at Darby Township Elementary would be sant to Studevan; that

it made more sense to pair the schools with certain grades being

offered only at Studevan and other grades only at D.T.E.; that white

parents would object less where all white .children in a particular-

grade^ and not just some, arbitrarily chosen, would now attend Studevan.

- There was some indication that appellant also opposed any

attempt to integrate Studevan (36a). That view was not shared

by her trial counsel. And it appears to have been abandoned in

this court, since appellants d o not argue in their brief that

compliance by the District with the order under review would

violate their rights.

_4/ Hereinafter referred to as "D.T.E."

__________________________________- 4 -___________________________ ___

TVo such plans prepared earlier by the District wer >

d i s Q c r S ^ T h e first would have placed all students in -grades—l ̂

and 2 at Studevan and all students in grades 3 through 6 at D.T.E.

with the administrative offices remaining where they are now

located — in a private dwelling. The second placed grades 1-4 at

D.T,E., grades 5 and 6 at Studevan and would have moved the

administrative offices to Studevan. Under either plan first and

second graders, rather young children, would be bused. The critical

d-itf-erenc-e between the two was that the first would involve white" ir ;t- -wed

first and second graders and the second Negro first and second

graders-. All parties realized that neither group wished to have

its young bused. After much discussion, it was decided that the

second plan promised to develop the most over-all community support.

All parties agreed tljat it was the most feasible method of integrating

Studevan. The District agreed to cohVene a Board meeting to adopt it

by resolution. Counsel for appellants, in appellants' own presence

assented to it as did intervenor and her counsel.

5. The Second Meeting with the Chancellor

On October 4, counsel for all parties met with the Chancellor .

in Chambers. No record of the conference was made. Counsel for the

School District informed him that the 2-1 resolution was being with

drawn, that the parties had agreed that Studevan would be integrated

by pairing with D.T.E. and that the Board had adopted a resolution

to that effect. All agreed that appellants' case had thereby be

come moot. At that time, however, the Board President, who was al

so present, indicated to the Chancellor that there was continuing

disruption in the community and that it.wished further direction from

the court (51a). Counsel for appellee-intervenors -thereupon- orally — -

moved the court to incorporate into an order the agreement reached by

the parti&s. The Chancellor was informed that the Negro community

•was still undecided whether it would assent to the new pairing

arrangement under which "their" young children, would be the ones

bused; . that if the new plan were put into the context of a court

order it would induce community acceptance of the agreement and end

the disruption plaguing the community for several months; that there

was no guarantee that the District would implement the agreement and 1

not'relent -in the facer of new opposition by the white community-r that.,

if it should fail to do so, the rights of appellee-intervenors to equaT

educational opportunities would be denied; that, all of these concerns

would be resolved, the dispute between the parties settled, peace and

normalcy returned to the community if an order were entered requiring

the Board to implement the agreement. — - •--- = ----

___ No verbal objection was made by appellants’ counsel, at the time;..

1 /so, with the apparent consent of all parties {.‘51,52 a), .the court, on

October 4, 1968, entered an order denying appellant's ’ petition for an

injunction on-the ground of mootness and directing the Board, to

implement a plan integrating the Studevan school, under the terms and

5/ in his opinion the Chancellor stated "’several plans were

discussed and it was agreed (or I thought it was agreed) that

the most workable plan would be . • . . " (53La) .

6

conditions agreed to by the parties (49a).

Appellants filed a notice of. appeal a'nd chi October 16, 1968,

and order was issued permitting the appeal to operate as a super

sedeas upon the furnishihg of a bond (56a).

- • SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT '

The injunctive order made the basis of this appfeal is directed *

at the School District not appellants. The School District consented

to the order. Since appellants do notf argue that compliance by the

District would violate any of their rights, they lack sufficient

interest therein to prosecute this appeal. -- -----*

•The lower court -could, in the -exercise, of its-equity powers;-

incorpora into an order the provisions of an agreement reached by

the parti s. Where the District consented to the injunctive decree,

and- where-, as here, the original pleadings gave notice that the pur

pose of the -intervention was to insure the implementation of an

integration plan, it was of no consequence that intervenors' motion

for an order against the Board was oral and not written.

Section 12 of the Human Relations Act, 43 P.S. §962 (b) , per

mits complaining persons to choose to vindicate their rights either

bef.o.re_the Commission or in court. One is barred in court- only- if- --

one had previously "-invoked" or "resorted to" the procedures pro

vided by the»act. Neither the original appellants nor intervenors

had previously "invoked" or "resorted to" the procedures provided by

the Human Relations Act. The court therefore had jurisdiction to

hear their claims and to provide relief. In any event, since the

rights-asserted by intervenors were derived from the Federal

Constitution, the court was obliged to accept jurisdiction notwith-

\

standing any procedures available under the Human Relations Act.

6/ Provisions 3 and 4 of the plan, that bus transportation be

furnished without regard to race and that faculties be integrated,

were proposed by appellee-intervenors and consented to by all parties prior to and at the meeting with the Chancellor.

6/

ARGUMENT

I. Appellant Is Not An Aggrieved F>arty

And Therefore Does Not Have Stamding

To Contest The Order of the Lower Cpurt

Sec. 1091^ Title 12 of Pennsylvania- Code wlhich sets out the

circumstances in which an appeal will lie, proxvides as follows:

If any parson on persons shall ifind him

or themselves aggrieved with the ^judgment

of any of the said courts of generral quarter. i _

sessions of the peace and jail de&ivery, or

. any other courts, of record within- this .

province, it st>all and may be lawfful to and

-* ■ for the party or parties so aggriieved,^to;“

ha.ve his "or their writ or writs cclf error; which

shall be granted to them, of counse, in such tr -

manner as other writs of error arcs to be* — ̂ ____ . . •

. ", . - - granted, and made returnable to tdhe said supreme ... . _.

court of this province. 1722, M3?,y 22, 1 Sm.L.

131, §9.

It is established that an aggrieved party, is cone who has "a present

interest in the subject matter and must be aggrieved by the judgment,

order, or decree entered." In re Elliott's Esrtate, 131 A. 2d 357,- 388

pa. 321 (1957) . "The interest which must:_be_ .tfrhus invaded must be

one in which the appellant has a right to be ^protected. . . . " -In

other words, to be aggrieved, a party must hav/a suffered the invasion

of. a Legal right, Atlee Estate, 406 Pa. 528, 53 32,. 1.78 A. 2d 722.,. 7.24

(1962). See also, Linden Hill Farm, Inc, v. Mlills Central Commission,

\217 A- 2d 735, 420 pa. 548 (1966); Appeal of D'xJDomenico, -6 Chester Co.

Repts. 4 (1953).

8

Putting to one side questions.concerning the propriety or

impropriety .of the lower courts issuance of the challenged order ‘

we believe appellant is not an aggrieved party within the meaning

of section 1091 and may not prosecute this .appeal. in the first

place, the order of which appellant complains does not run against

her. It directs the Board to implement a plan of integration, which

plan was consented to by the other parties and appellants 1 own

trial counsel. The Board itself consented to the order. Appellee-

intervenors are unaware of-'any* case in which a party'has been

.permitted to appeal an injunctive order not procured by it and which

runs against some other party. - __ .

--.l Conceivably a party might have standing to appeal' an order :

directed at another party, where compliance by’ that dthet party ~ A

would-endanger or impair some legally enforceable interest of the

party taking the appeal. But it is only on such a showing that

I

such .a..party could manifest sufficient interest to be deemed

"aggrieved." Here no such showing is made or attempted. No where

in appellants' brief do they argue that compl-iance by the Board

with the order would damage them or otherwise violate any protected

interest. That being the case, and since the order runs against a

• «

party who consents to it, our submission* is that appellant is not

an aggrieved party and therefore lacks standing to prosecute this

appeal. And this is so whether or not appellant consented or

objected to its entry below.

N

-9-

II. Ihe Lower Court Could Provide

. . _ Relief to Pefendant-InteCTenors

' * Although Petitioners- Casa Had

Become Moot.

Appellants' case became moot when the School District withdrew

the challenged resolution and announced to the Chancellor that the

parties had agreed to a pairing arrangement. But that did not end

- — the dispute as between all parties; and it certainly would not have r--

quelled the disruption then occurring in the community.

- Appellee-intervenors’ interest-was then and still is different —

from that o-f- the District. Having been permitted to intervene as a

party they were free to assert claims for relief against the Board;

•andUthpse.-Qlaims could be asserted and relief afforded without -r«saj.-e

• - * regard’to the-fact that pl-aintif f-appellants we ref entitled-"to no 'relief.

_ . Appellee-intervenors intervened in this case because they - .3

believed they were "not adequately represented by the present parties ‘

because of, inter alia, the patron-elected official relationship __ •

existing between plaintiffs and some of- the defendants, and because

defendants are free to disregard [intervenor’s] rights. . . by

compromising, settling or otherwise consenting to the dismissal of

this litigation in a manner which does not fully protect [their]

rights."(14a). We were wise to have intervened. Had the case merely

1 been dismissed desegregation of the Darby Township Public Schools

could have been indefinitely postponed/- and fh.a Negro minors subjected

to continuing irreparable injury. - -

After the School Board decided to withdraw the resolutions, the

President of the Board discussed with the Chancellor the problems it

was having desegregating the schools. The court was also aware of

-10-

the turmoil the'desegregation issue was causing among both blacks

and whites. He states in his opinion that "the situation. . . was

in many respects critical, the question of bussing white children

to black schools was uppermost in the minds of the contending parties

and racism was apparent from many angles"(50a) . Secondly, there was"-

the fact that the Board had permitted for several years the total

segregation of Studevan in violation of intervenors1 rights.

Intervenor had no guarantee that the Board would, indeed, implement

and "carry out the new pairing arrangement; finally there was the .

added problem that segments of the Negro community.' jposed the new

plan which required that their young children be bused. Intervenors

believed" that the full support of the black comnmmity,CQuld be .

developed if the plan were presented in the context of a court order.

For ®li these reasons intervenors asked the court: to enter an order r-v.rr

requiring the District to implement the various ^features of the new

agreement. None of the parties then expressed opposition- to - the ■>>- -'•=>= . - •

order. And with the apparent consent of all he. entered it.

We- believe the Chancellor was empowered to do what he did.

Equity courts have power to determine all the rights of parties and.

to grant such relief as will .finally determine the issues.between them,

and the decree should be framed to that end so that complete justice -

will be done. OverfieId v. penroad Corp., 42 F_ Supp. 586, opinion

supplemented 48 F. Supp-. 1008 (E.D. Pa.), aff1 d 146 F.2d 889 3d Cir.

(1945) .. Likewise, a court of equity which has assumed jurisdiction

will retain jurisdiction to prevent a multitude of actions, Lafean v.

American Caramel Co., 271 Pa. 276 114 Atl. 622, (1921). Here, the

Chancellor was aware of the disruption in the community. He also was

-11-

aware that entering the order requested by intervenors and consented

to by the other parties would assist in settling the dispute. It

eliminated the possibility of another action by intervenors against

the District, if it failed to carry out the new ]plan. In his

discretion he decided "to take time by the foreliock" and enter an

order -- then consented to by all parties -- wiiiLch promised to "end

the litigation." (52a)

In these circumstances, he can hardly be famlted for-»having done

so.

Appellants 1 argument that his action was hairred by reason of

the rule' of Celia v. Davidson, 304 pa. 389, A. 9)9 is misplaced. That

casgL. 4-S"distinguishable on the facts from the ome here, because it ̂

did not concern the rights of a defendant-intarwenor whose cross

claim was justiciable in equity.

Lack of Notice in the Pleadings

— •“--Appellants argue that the court could not grant intervenors"

motion to incorporate the new agreement into ait injunctive order

against-the Board because-intervenors1 pleadings stated no claim

against the district and gave no notice of the tissues raised. But

appellants would exalt form over substance. The very essence of the

suit had been bared by the pleadings and the testimony. It was quite

clear that the real question was whether and haw the Board cou-ld

correct racial imbalance existing at Studevan ((erf. 36a)-. When the

Board adopted a plan to do so and was sued, intervenors joined to

uphold its power and define its obligation to <Tco so. The purpose of

intervention was to ensure that the Board would! be permitted to go

\through with its integration plan. Intervenors1 later motion, )

therefore, that the plan be placed into an ordear raised no new

-12-

subject matter and could have been made orally,

be

Even if it/held that intervenors' request for affirmative

• relief against the Board should properly have been in a written

plead’ing, that objection we believe is only open to the Board.

The Board does not object but rather consented below to the entry

of the order and also acquiesces in this court.

-~'-For -the same reasons discussed in point I, pp. 8-9, supra,... T

we believe appellants have no standing to question the procedures

under,<whichLrthe order was entered. Since the order-runs against- - -he orde

the Board, and appellants do not argue that- compliance by the Board

would violate their statutory or constitutional rights, they are'

r. r rt precluded" from contesting the circumstances of its issuance.instanceof _tg:

______ The Absence of a Bond __[_________;_ ;_ .___

Appell-ants1 argue that the order was a preliminary injunction' .

and that .the court erred in failing to require a bond. But the order •

was clearly, and intended by the Chancellor to be, a final mandatory

injunction. The -facts underlying intervenors ’ right to relief were

known to the court and discernible from the record. No further

hearing to establish intervenors’ right to relief was contemplated

or necessary.

The short answer to appellants' contention, however, is that

no bond was necessary since the Board consented to the order. The

purpose of the Bond requirement is to indemnify the party against

whom injunctive relief is sought. Here, it would have been silly

for the court to insist on a bond where the Board acquiesced in the

issuance of the injunction.

-13

III. The Lower Court Had' Jurisdiction

•- To Entertain Appel lee-In tervenors-1 ~

Claims Notwithstanding Section 12

Of The Pennsylvania Human Relations

Act. __:_

—Having themselves chosen the forum in which to litigate the --

propriety of the District's efforts to integrate Studevan, and

having been successful in having the court disallow the 2 - 1 assign

ment method, appellants now reverse their position by challenging

the jurisdiction of the lower court to hear the matter.

Appellants argue that the lower court lacked jurisdiction to

afford relief because of Section 12 of the Pennsylvania-Human-

Relations Act, 43 P.S. 962(b), and because the Human Relations

Commission had assumed jurisdiction. Section 962(b), however, 1:

provides:

If such complainant institutes any

• * action based on such grievance without

— -- resorting to the procedure provided" in~~~ 7"

this act he may not subsequently- re- ~ ‘ “

sort to the procedure herein.

Thus a person claiming a violation of a right granted by the Act *

can eleot to obtain a remedy either before the Commission or in

court. The same section provides that "the procedure herein shall,

when invoked, be- exclusive. . and that it excludes only such

other actions as are "based on the same grievance of the complainant

^concerned." A -person is barred from court, therefore, only if that

very person had previously "invoked" or "resorted to" the pro

cedures provided by the act to redress the very same grievance."

14

Here^ appellants, although they claimed a violation of. --

their rights under the act, had never "invoked" or "resorted to"

the procedure provided by the act and the court was obliged to

_take jurisdiction.- The same was true of the intervenors' claims.

They alleged no rights under- Pennsylvania law in their pleading

nor had they ever "invoked" or "resorted to" the procedures of the

act. Their claims therefore were not barred by 962 (b.) . To be*

sure, since the Commission had directed the District to prepare

a plan, it .could be inferred that someone did resort to the act

to effect the elimination of imbalance in township schools. But

the act by its terms bars only subsequent actions "on the same

grievance- ofhthe complainant- concerned. " Note 4 of the Chester ■-■nr:- <- '

case, ,22.3_„A. 2d..293 (1967), suggests -- as does the. plain language

•of the statute — that the very same person must have made the -

Iearlier resort to the Commission. Thus, that other persons, j

white or Negro, might have activated the Commission would not

bar intervenor .where she-had made -no previous attempt herself.

In any event, the rights sought to be vindicated by intervenors

were rights guaranteed by the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments

2 /of the United States Constitution, and as to such rights one

need not exhaust the state system of enforcement. Thus, in

. Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167, 183 the Supreme Court held:

7/ Intervenors sought to protect their "rights guaranteed by

the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution

of the United States to equal educational opportunity free N

from racial discrimination or segregation."

15

It is no answer that the state has a law

— which if enforced would give relief.L The

federal remedy is supplementary to the state,

remedy and the latter need not be sought, and

refused before the federal one is invoked.

And in McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. >6 6 8, 674, it was __

held that, "It is immaterial whether respondent's conduct is

legal or illegal as a matter of state law. Sudfh claims are

entitled to be adjudicated in the federal court's."'' it is no answer* *

that these-cases were brought in federal court- Under the Supremacy

Cla^se^£U^§-.i,€onst. , Art. VI, Clause 2, 'if federal courts'would, be teds

obliged to accept jurisdiction and provide relixef although relief

is-' available from a state agency, state courts would similarly be

obligated. :

The court-below sought and-obtained from the parties in the

proceedings below the same attitude of conciliation, restraint and

flexibility that characterizes proceedings befonre the Human Relations

Commission. Indeed the court was able to prodix<ce a plan for the

1968-69 school year (while the Commission had mot), which plan would

have been implemented but for this appeal. - .-_-r ■

We reiterate -that this is not a -case where- appellants have been

dragged before a hostile forum, protested the alleged lack of

jurisdiction of the court and had to incur the additional risk of ,

expense and delay to appeal a decision inimical, to their interests.

Appellants began this litigation in this Court,, resolved it in

their favor, and now seek to challenge its power because the

Chancellor also acted to facilitate the orderly elimination of the

16

imbalance that prevailed. We submit that the challenge fails

i : n i i n

since §962(b) — in the circumstances of this case — does not

deprive the lower court of the power to accept jurisdiction over

the subject matter.

CONCLUSION

. For the foregoing reasons, the appeal should be dismissed.

5U.S Ci rcie

Respectfully submitted, -— - --

FRANKLIN E. WHITE ISSNKLEX Z - U

LOWELL JOHNSTON .

10 Columbus Circle 10 jCo lure bus

New York, New York 10019

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

220 Locust Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19108

IJOSEPH A. MCNEAL 1 ----

1400 Bankers Securities Building

tPhiladelphia, Pennsylvania 19107

Attorneys for Appe-llee-lntervenors

\

-17