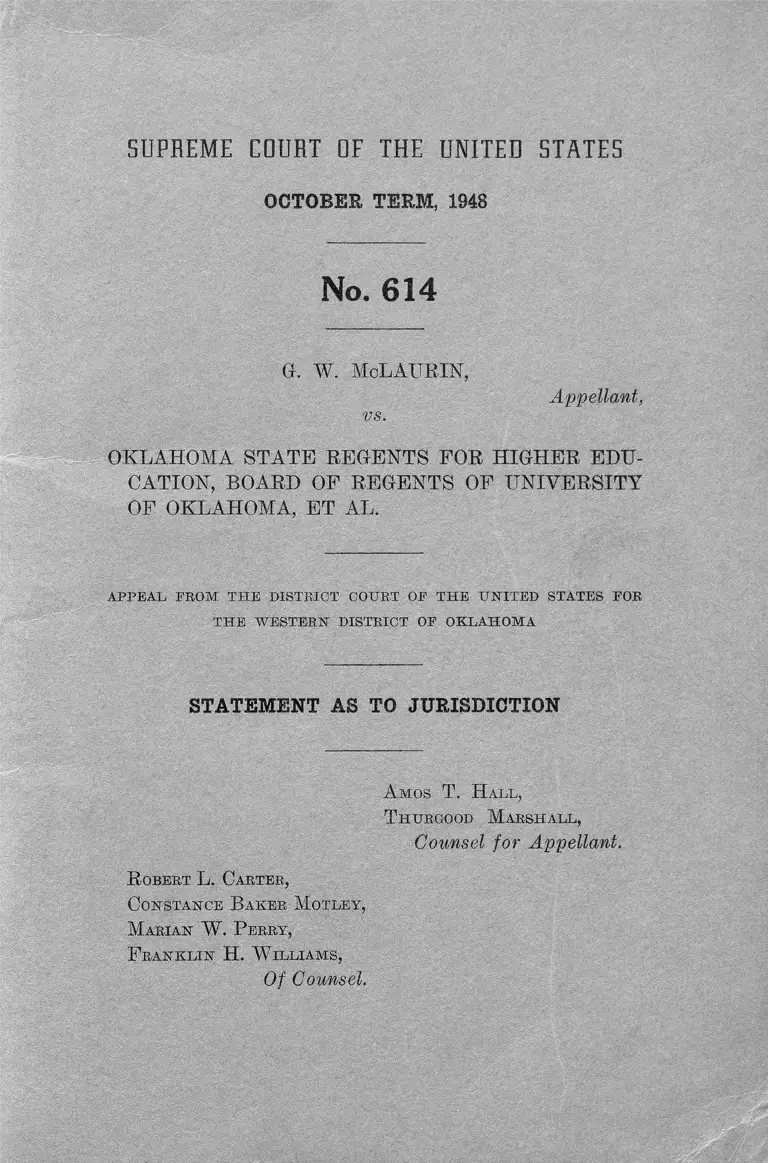

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education Statement as to Jurisdiction

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1948

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education Statement as to Jurisdiction, 1948. 86d976c0-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0a9f44a6-e82c-41c6-bff6-995aa654ba14/mclaurin-v-oklahoma-state-regents-for-higher-education-statement-as-to-jurisdiction. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

SU P R E M E COURT OF THE U N ITED ST A T E S

OCTOBER TERM, 1948

No. 614

G. W. McLAURIN,

vs.

Appellant,

OKLAHOMA STATE RELENTS FOR HIGHER EDU

CATION, BOARD OF REGENTS OF UNIVERSITY

OF OKLAHOMA, ET AL.

APPEAL FROM THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES FOR

THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF OKLAHOMA

STATEMENT AS TO JURISDICTION

A mos T. H all,

T hurgood Marshall,

Counsel for Appellant.

R obert L. Carter,

Constance Baker M otley,

Marian W . Perry,

F ranklin H. W illiams,

Of Counsel.

INDEX

Subject I ndex

Statement as to jurisdiction...........................................

Statute sustaining jurisdiction..............................

The state statutes and administrative orders, the

validity of which is involved.............................

Order by Board of Regents of University of

Oklahoma, a State Board, acting pursuant to

state statutes, the validity of which is in

volved .....................................................................

Dates of judgment and of application for ap

peal .........................................................................

Nature of the case and rulings in the District

Court .....................................................................

Statement of the grounds upon which it is con

tended that the questions involved are sub

stantial ...................................................................

Summary...........................................................

Argument...................................................................

Access to public education is so vital to De

mocracy that it requires the highest con

stitutional protection .................................

The United States Constitution prohibits

government classifications based on race

or ancestry...................................................

The order of the defendant State Board of

Regents requiring the segregation of the

plaintiff enforced by the exclusion of the

plaintiff from the regular classroom solely

because of race is unconstitutional...........

The conflict between early and recent deci

sions of the Supreme Court defining the

limits of state power to make classifica

tions based on race under the Fourteenth

Amendment should be resolved.................

Conclusion.............................................................

Page

1

1

2

3

4

4

9

13

15

19

23

— 1390

CO

-

<

l

11 INDEX

Page

Appendix ‘ ‘ A ’ ’—Oklahoma Statutes involved............ 25

Appendix “ B ’ ’—Order involved ................................. 26

Appendix “ C ” —Journal entry of District Court. . . . 27

Appendix “ D ” —Findings of fact and conclusions of

law of the District C ou rt........................................... 28

Appendix “ E ” — Journal entry of District Court. . . . 32

Appendix “ F ” —Findings o f fact and conclusions of

law of the District Court............................................. 33

Table ok Cases Cited

Atchison R.R. v. Matthews, 174 U. S. 96..................... 21

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60............................... 8

Carolina Highway Dept. v. Barnwell, 303 U. S. 177. . 21

Great A. <& P. Co. v. Grosjean, 301 IT. S. 412.............. 21

Grovey v. Townsend, 295 U. S. 45................................. 22

Hall v. DeCuir, 95 IT. S. 485............................................. 9

Hirabayashi v. U. 8., 320 U. S. 81................................. 13

Korematsu v. U. 8., 323 U. S. 214................................. 14

Liggett v. Lee, 288 U. S. 517........................................... 21

Mayflower Farms v. Ten Eyck, 297 U. S. 266............. 17

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 307 U. S. 305......... 8

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373................................. 9

Myers v. Nebraska, 262 IT. S. 390................................... 18

Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633............................ 13,14,17

Patsone v. Pennsylvania, 232 U. S. 138......................... 21

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510..................... 18

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537................................. 9, 20

Railway Mail Association v. Corsi, 326 IT. S. 88......... 15

Rosenthal v. New York, 226 IT. S. 260........................... 21

Shelley v. Kraemer, 92 L. Ed. 845................................. 8,14

Sipuel v. Board of Regents of TJniv. of Okla., 332

TJ. S. — .......................................................................... 7

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S. 535............................... 21

Smith v. Allwright, 321 IT. S. 649................................... 22

Steele v. Louisville <& Nashville R.R. Co., 323 IT. S.

1 92 .................................................................................. 15

Takahaski v. Fish & Game Commission, ■— IT. S. — . . 14

United States v. Classic, 313 IT. S. 299......................... 22

INDEX 111

Statutes Cited _Page

American Jurisprudence, Yol. 47, Section 6, p. 299. . 10

Congressional Globe, Forty-Third Congress, May 22,

1874 ................................................................................ 11

Constitution of the United States:

Fifth Am endm ent.................................................. 15

Fourtenth Amendment................ 6,11,13,15,17,18,19

Judicial Code, Section 266............................................. 4

Mannheim, Karl, “ Diagnosis of Our Time,” Oxford

University Press, 1944, p. 177..................................... 11

Oklahoma Statutes, 1941, Title 70:

Section 455 .............................................................. 2, 4, 5

Section 456 ............................................................... 2, 4, 5

Section 457 ............................................................ 2, 3, 4, 5

Report on Inequality of Opportunity in Higher Edu

cation, Mayor’s Committee on Unity, Hew York,

1946, pp. 1, 2 ................................................................. 12

Report of the President’s Committee on Civil Rights,

Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C.,

1947, p. 1 6 6 ................................................................... 23

Report of the President’s Commission on Higher Ed

ucation, Higher Education for American Democ

racy, Government Printing Office, Washington,

D. C., 1947, Vol. 1, p. 5 ................................................. 11

United States Code, Title 28:

Section 1253 ............................................................. 1

Section 2281 ............................................................. 2

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

WESTERN DISTRICT DF OKLAHOMA

Civil No. 4039

G. W. McLAURIN,

vs.

Plaintiff,

BOARD OF REGENTS OF UNIVERSITY OF OKLA

HOMA, GEORGE L. CROSS, LAWRENCE H. SNY

DER and J. E. FELLOWS,

Defendants

STATEMENT IN SUPPORT OF JURISDICTION

The plaintiff-appellant, having presented this day his

petition for appeal and assignment of errors, now files

this his statement of the basis upon which it is contended

that the Supreme Court of the United States has jurisdic

tion on a direct appeal to review the final order and judg

ment in question, and should exercise such jurisdiction in

this case.

I

Statute Sustaining Jurisdiction

The Supreme Court of the United States has jurisdic

tion to review this cause on appeal under the provisions of

Title 28 United States Code, section 1253, this being an

appeal from an order denying, after notice and hearing, an

injunction in a civil action required by an act of Congress

2

to be beard and determined by a district court of three

judges. (Title 28, United States Code, section 2281) The

District Court for the Western District of Oklahoma sitting

as a specially constituted three-judge court rendered a final

judgment in this cause sustaining the validity of an order

made by an administrative board acting under statutes of

the State of Oklahoma after the validity of that order and

statutes had been placed in issue by the plaintiff on the

ground of its being repugnant to the Constitution of the

United States.

II

The State Statutes and Administrative Orders, the Validity

of Which Is Involved

The Oklahoma Statutes, the validity of which are involved

are Sections 455, 456 and 457 of Title 70 of the Oklahoma

Statutes (1941) which provide in part as follows: 70 O. S.

1941, Section 455 makes it a misdemeanor, punishable by

a fine of not less than $100 nor more than $500 for

“ any person, corporation or association of persons

to maintain or operate any college, school or institution

of this State where persons of both white and colored

races are received as pupils for instruction,”

and provides that each day same is to be maintained or

operated “ shall be deemed a separate offense.”

70 O. S. 1941, Section 456, makes it a misdemeanor, pun

ishable by a fine of not less than $10 nor more than $50 for

any instructor to teach

“ in any school, college or institution where members

of the white race and colored race are received and en

rolled as pupils for instruction,”

and provides that each day such an instructor shall con

tinue to so teach “ shall be considered a separate offense.”

3

70 0. S. 1941, section 457, makes it a misdemeanor pun

ishable by a fine of not less than $5 nor more than $20 for

“ any white person to attend any school, college or

institution, where colored persons are received as pupils

for instruction,”

and provides that each day such a person so attends ‘ ‘ shall

he deemed a distinct and separate offense. ’ ’

The full text of these statutes is set forth in the Appen

dix hereto.

At the hearing for a preliminary injunction the Court

held that “ insofar as any statute or law of the State of

Oklahoma denies or deprives this plaintiff admission to the

University of Oklahoma for the purpose of pursuing the

courses of study he seeks, it is unconstitutional and unen

forceable.” The Court, however, refused to issue a prelim

inary injunction.

Order by Board of Regents of University of Oklahoma, a

State Board, Acting Pursuant to State Statutes, the Valid

ity of Which Is Involved.

Subsequent to the above order of the Court the filing of

a motion for further relief by the plaintiff, the defendant

Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma acting

as a state board pursuant to the statutes of Oklahoma

adopted an order which appears in the minutes of said

board as follows:

“ That the Board of Regents of the University of

Oklahoma authorize and direct the President of the

University, and the appropriate' officials of the Uni

versity, to grant the application for admission to the

Graduate College of G. W. McLaurin in time for Mr.

McLaurin to enrol at the beginning of the term, under

such rules and regulations as to segregation as the

President of the University shall consider to afford

to Mr. G. W. McLaurin substantially equal educational

4

opportunities as are afforded to other persons seeking

the same education in the Graduate College, and that

the President of the University promulgate such regu

lations. ’ ’

In refusing to enjoin the enforcement of this order the

Court held as a matter of law that: “ The Oklahoma stat

utes held unenforceable in the previous order of this Court

have not been stripped of their validity to express the pub

lic policy of the State in respect to matters of social

concern.”

The Court refused to enjoin the enforcement of either

the statutes or the order, dismissed the complaint of the

plaintiff, and rendered judgment for the defendants.

III

Dates of Judgment and of Application for Appeal

The date of the judgment of the United States District

Court for the Western District of Oklahoma which is now

sought to be reviewed was November 22d, 1948. The ap

plication for appeal was presented on January 18th, 1949.

IV

Nature of the Case and Rulings in the District Court

On the 5th day of August, 1948, plaintiff filed in the

United States District Court for the Western District of

Oklahoma a complaint seeking a three-judge court as re

quired by the then existing Section 266 of the Judicial Code

for the issuance of a preliminary and permanent injunction

against the Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education,

the Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma and

the Administrative Officers of the University of Oklahoma

from, enforcing Sections 455-457 of the Oklahoma statutes

of 1941 under which the plaintiff and other qualified Negro

5

applicants were excluded from admission to the courses of

study offered only at the Graduate School of the University

of Oklahoma.

The complaint alleged that the plaintiff, G. W. McLaurin,

was qualified in all respects for admission to the Graduate

School of the University of Oklahoma but was denied ad

mission solely because of race or color pursuant to the stat

utes of the State of Oklahoma and the orders of the Board

of Regents of the University of Oklahoma acting pursuant

to said statutes. Motion was made for a preliminary injunc

tion. A hearing was held on the motion for preliminary

injunction upon an agreed' statement of facts in which all

of the material facts were admitted and agreed upon. It

was admitted that plaintiff, McLaurin, was qualified in all

respects other than race or color for admission to the Uni

versity of Oklahoma and that the courses he desired were

offered by the State of Oklahoma only at the University of

Oklahoma.

On the 6th day of October, 1948, the three-judge court

filed a journal entry that “ it is ordered and decreed that

insofar as Sections 455, 456 and 457, 70 0. S. 1941, are

sought to be applied and enforced in this particular case,

they are unconstitutional and unenforceable.” The Court,

however, refrained from issuing and granting any injunc

tive relief but retained jurisdiction over the subject matter

for entering any further orders as might be deemed proper.

On the 7th day of October, 1948, plaintiff filed a motion

for further relief alleging that despite the prior ruling of

the court, plaintiff had again been denied admission to

the Graduate School of the University of Oklahoma and

requested that the court enter an order requiring defend

ants to admit plaintiff to the “ graduate school of the Uni

versity of Oklahoma for the purpose of taking courses lead

ing to a doctor’s degree in education, subject only to the

6

same rules and regulations which, apply to other students in

said school.”

At this hearing there was placed in issue the order of

the defendant Board of Regents of the University of Okla

homa ordering that the plaintiff be admitted only on a basis

of segregation solely because of his race. The plaintiff chal

lenged the order as unconstitutional and the defendants

rested upon the validity of such order as within the power

of the Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma as a

state board.

At the hearing on said motion for further relief, the es

sential facts were agreed upon by counsel for both parties

and, in addition, plaintiff testified as to the conditions under

which he was admitted to the University of Oklahoma subse

quent to the filing of the motion for further relief.

On the 22d day of November, 1948, the three-judge court

issued Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law and Journal

Entry. In the Conclusions of Law, the Court held:

1. That the United States Constitution “ does not author

ize us to obliterate social or racial distinctions which the

State has traditionally recognized as a basis for classifica

tion for purposes of education and other public ministra

tions. The Fourteenth Amendment does not abolish dis

tinctions based upon race or color, nor was it intended to

enforce social equality between classes and races.”

2. “ It is the duty of this court to honor the public policy

of the State in matters relating to its internal social affairs

quite as much as is our duty to vindicate the supreme law

of the land.”

3. “ The Oklahoma statutes held unenforceable in the

previous order of this court have not been stripped of their

vitality to express the public policy of the State in respect

to matters of social concern.”

7

4. “ We conclude therefore that the classification, based

upon racial distinctions, as recognized and enforced by the

regulations of the University of Oklahoma, rests upon a rea

sonable basis, having its foundation in the public policy of

the State, and does not therefore operate to deprive this

plaintiff of the equal protection of the laws.”

The journal entry entered by the Court denied the relief

prayed for, dismissed the complaint of plaintiff and entered

judgment for the defendants.

V

Statement of the Grounds upon Which It Is Contended That

the Questions Involved Are Substantial

Summary

The issue presented by this case has never been decided

by the United States Supreme Court.

For one year the plaintiff has been endeavoring to secure

admission to classes given at the University of Oklahoma

leading to a doctor’s degree in education. Such education

is offered by the state only at the University of Oklahoma.

Originally plaintiff was excluded from the University by the

defendants in reliance upon the same criminal statutes pro

hibiting inter-racial education upon which these defendants

had relied in excluding a qualified Negro from the law

school.1

When those statutes had been declared unconstitutional

insofar as they operated to exclude plaintiff from the only

educational facility offered by the state, the defendants

ordered plaintiff to be admitted to the University on a

segregated basis. In operation, that order, while purport

1 See Sipuel v. Board of Regents of University of Oklahoma, 332 TJ. S.

—, decided January 12, 1948.

8

ing to admit plaintiff, actually excludes him from the class

in which the desired courses are given, for he has been

placed in a different room from which he participates in

class work through an open door.

All other students at the University of Oklahoma are

accepted on an equal basis without regard to race, ancestry,

creed, color or consideration other than individual merit.

Plaintiff is excluded from the regular classroom, the regular

library rooms and the main part of the cafeteria. This

exclusion and segregation is based wholly in terms of race

or color, “ simply that and nothing more.” 2 3 Solely because

plaintiff is a Negro he has been denied rights enjoyed as a

matter of course by other citizens of other races.

It is in this historical and factual context that the issue

raised by the denial of plaintiff’s motion for an injunction

compelling his admission to the graduate school of the

University “ for the purpose of taking courses leading to

a doctor’s degree in education, subject only to the same

rules and regulations which apply to other students in said

school.”

Thus, this Court is asked to decide—

Whether in providing graduate education in a state uni

versity the state may exclude a Negro student from the class

room and require him to participate in classes through an

open doorway maintaining a spatial separation from other

students ?

No previous decision of this court dealing with the exclu

sion of Negroes from educational facilities 8 or with the

2 Shelley v. Kraemer, 92 L. Ed. 845 Adv. Sheets; Buchanan v. Warley,

245 U. S. 60.

3 Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada, 307 U. S. 305, Sipuel v. Board of

Regents of University of Oklahoma, supra.

9

separation of the races in other aspects of life 4 has ever

passed upon the issue here presented.

This question is certainly substantial, undecided by any

decisions of this Court, and is of such a character as to

affect the basic rights of citizens of all races, not only in

Oklahoma but throughout the United States.

VI

Argument

The right here involved is set forth clearly in the prayer

for further relief where plaintiff sought an injunction re

quiring the defendants to admit the plaintiff “ to the grad

uate school of the University of Oklahoma for the purpose

of taking courses leading to a doctor ’s degree in education,

subject only to the same rules and regulations which apply

to other students in said school. ’ ’

The right of Negroes not to be excluded from the only

state university offering the desired subjects has been clearly

established and recognized by this Court. However, the

right of a Negro student subsequently admitted to such

university not to be excluded from the regular classroom

and thereby ostracized solely because of race or color and

segregated from fellow students of all other races and

colors has not been decided by the Supreme Court.

A

Access to Public Education Is So Vital to Democracy That

It Requires the Highest Constitutional Protection

The role of education, in a democracy, might be defined as:

The development in all citizens of the fullest intellectual and

4 Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537; Hall v. DeCuir, 95 U. S. 485; Mor

gan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373.

10

moral qualities, and the most effective participation in the

duties of the citizens.

Any general agreement with this definition would auto

matically preclude any system of segregation on the basis of

color,—the existence of which would most certainly abort

any meaningful “ . . . participation in the duties of the

citizens. ’ ’

I f an enlightened citizenry is a necessary factor in the

equation of democracy, then it follows that education is an

integral part of the democratic process. If education be a

privilege, it is one of such a peculiar and precious nature

that those entrusted with its administration have a com

pelling duty rather than mere discretionary power to see

that no distinctions are made on the basis of race, creed

or color.

Segregation in education is doubly damaging. First, it

prevents both the Negro and white student from obtaining

a full knowledge and understanding of the group from which

he is separated, thereby infringing upon the natural rights

of an enlightened citizen. Second, a feeling of distrust for

the minority group is fostered in the community at large, a

psychological atmosphere which is not favorable to the

acquisition and conduct of an education or for the discharge

of the duties of a citizen.

As stated in 47 Am. Jur., Schools, Section 6, p. 299, at

common law, the parent’s control over his child extended to

the acquisition of an education. The parent’s common law

rights and duties in this regard “ have been generally sup

plemented by constitutional and statutory provisions, and

it is now recognized that education is a function of the gov

ernment.” (Italics ours.)

Education is not only a component part of true demo

cratic living, but is the very essence of and medium through

which democracy can be effected. The intent of the framers

1 1

of the Fourteenth Amendment was indicated in the 43rd

Congress in 1874 by these words: . . that all classes

should have the equal protection of American law and he

protected in their inalienable rights, those rights ivMch

grow. out of the very nature of society, and the organic law

of this country. ’ ’ 5 In 1943, an eminent sociologist and

economist, Dr. Karl Mannheim, then Professor of Eco

nomics at London School of Economics, said;

“ Finally, there is a move towards a true democracy

arising from dissatisfaction with the infinitesimal con

tribution guaranteed by universal suffrage, a democ

racy which through careful decentralization of func

tions allots a creative social task to everyone. The

same fundamental democratization claims for everyone

a share in real education, one which no longer seeks

primarily to satisfy the craving for social distinction,

but enables us adequately to understand the pattern of

life in which we are called upon to live and act.” 5 6

Finally, in 1947, seventy-three years after the 43rd

Congress, the President’s Committee on Higher Education

took an unequivocal position against segregation in educa

tion. In terms of a definition of the role played by educa

tion the Report said:

“ . . . the role of education in a democratic society

is at once to insure equal liberty and equal opportunity

to differing individuals and groups, and to enable the

citizens to understand, appraise, and redirect forces,

men, and events as these tend to strengthen or to weaken

their liberties.” 7

5 Congressional Globe, Forty-Third Congress, May 22, 1874.

6 Mannheim, Karl, Diagnosis of Our Time, Oxford University Press,

1944, p. 177.

7 Report of the President’s Commission on Higher Education, Higher

Education for American Democracy, Gov’t. Printing 'Office, Washington,

1947, Vol. I, p. 5.

12

Discrimination on the part of educational institutions

constitutes a deeper injury to democracy. The Mayor’s

Committee on Unity stated in its Report on Inequality in

Higher Education: 8

. . It is generally agreed that the most urgent

social problem of the day is to attain such attitudes of

understanding and mutual respect among all elements of

our population as will enable them to live together

in harmony, regardless of diversity of race, creed, color

or national origin. We call that the American Way.

Actually such a condition is impossible of realization

unless the principle of equality of opportunity in the

important fields of human endeavor and relationship is

recognized not only in theory but in practice, and until

people are judged on the basis only of their own indi

vidual worth, and not according to what race they be

long to or what creeds they profess.

“ To attain such a goal, deep-seated prejudices must

be overcome. And it is on education, in the broadest

sense of the term, that we must primarily rely to correct

these prejudices.”

In the light of this role played by education, it is par

ticularly pertinent to consider the uncontroverted testi

mony of the plaintiff that the effect upon him of his ex

clusion from the classroom is to deny him an opportunity

to secure an equal education. Leaving aside for the

moment the grave damage to society resulting from the

failure of education to demonstrate in practice the principle

of equality upon which our society is founded, in this case

the plaintiff’s individual right, guaranteed by the Consti

tution, to have an equal opportunity to secure an education

. has been denied by the segregation practiced by the Univer

sity of Oklahoma.

8 Report on Inequality of Opportunity in Higher Education, Mayor’s

Committee on Unity, New York, 1946, pp. 1, 2.

13

B

The United States Constitution Prohibits Government

Classifications Based On Race or Ancestry

In recent cases the Supreme Court has held on many

occasions under a variety of circumstances that racial

criteria are irrational, irrelevant, odious to our way of life

and specifically proscribed under the Fourteenth Amend

ment.9 Whether this proscription against racial classifica

tions be found in the constitutional concept of equal pro

tection 10 or is included within the meaning of due process,11

the result is the same. The only apparent limitation on

this doctrine appears to be that of a national emergency

such as the danger of espionage and sabotage in time of

war which might control the decision of the Court.

In Hirabayashi v. United States,12 the Supreme Court

had to determine whether a curfew order adopted by the

West Coast military commander pursuant to Congressional

authority violated petitioner’s constitutional rights in

that the curfew applied only to persons of Japanese ances

try.

The Court said:

‘ ‘ Distinctions between citizens solely because of their

ancestry are by their nature odious to a free people.

For that reason, legislative classification or discrim

ination based on race alone has often been held to be a

denial of equal protection. ” 320 U. S. 101.

Except for the dangers of war and sabotage the racial

distinctions there in issue would have been struck down.

9 Shelley v. Kraemer, supra, Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 214; Taka-

hashi v. Fish <& Game Commission, — U. S. — .

10 Shelley v. Kraemer, supra.

11 Hirabayashi v. V. S., 320 U. S. 81.

12 320 U. S. 81.

14

In Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214, petitioner

was convicted for remaining in California in violation of the

Japanese exclusion order. The Court said that “ legal

restrictions which curtail the civil rights of a single racial

group are immediately suspect. . . . Pressing public

necessity may sometimes justify the existence of such re

strictions; racial antagonism never can.”

In 0 i/ama, v. California, 332 U. S. 633 (1948) the Court

had before it the constitutionality of the California Alien

Land Law which forbade aliens ineligible for American

citizenship from acquiring, owning, occupying, leasing or

transferring agricultural land.

Said the Court: “ In approaching cases, such as this one,

in which federal constitutional rights are asserted, it is in

cumbent on us to inquire not merely whether those rights

have been denied in express terms, but also whether they

have been denied in substance and effect. We must re

view independently both the legal issues and those factual

matters with which they are commingled. . . . In our view

of the case, the State has discriminated against Fred

Oyama; the discrimination is based solely on his parents’

country of origin; and there is absent the compelling justi

fication which would be needed to sustain discrimination of

that nature.”

In Shelley v. Kraemer, 92 L. Ed. 845, Adv. Sheets, the

basic issue was the validity of court enforcement of racial

restrictive covenants intended to exclude Negroes from

the ownership or occupancy of real property. The Court

stated: ‘ ‘ Because of the race or color of these petitioners

they have been denied rights of ownership or occupancy

enjoyed as a matter of course by other citizens of different

race or color.” . . . 92 L. Ed. 855, Adv. Sheets.

“ The historical context in which the Fourteenth Amend

ment became a part of the Constitution should not be for

gotten. Whatever else the framers sought to achieve, it is

15

clear that the matter of primary concern was the establish

ment of equality in the enjoyment of basic civil and political

rights and the preservation of those rights from discrimi

natory action on the part of the States based on considera

tions of lace or color.” . . . “ Upon full consideration,

we have concluded that in these cases the States have acted

to deny petitioners the equal protection of the laws guaran

teed by the Fourteenth Amendment.” (92 L. Ed. 857 Adv.

Sheets.)

The Supreme Court has also held that union bargaining

representatives operating under authority of Congress are

not permitted to discriminate because of race or color.13

On the other hand state statutes prohibiting racial discrim

ination by labor unions have been upheld as within the

spirit of the Fourteenth Amendment.14

It is clear that although states are permitted to make rea

sonable classifications for governmental purposes, classifi

cations on the basis of race are unconstitutional violations

of the Fifth or Fourteenth Amendment depending on

whether the racial classification is by the federal or state

government.

0. The Order of the Defendant State Board of Regents

Requiring the Segregation of the Plaintiff Enforced

by the Exclusion of the Plaintiff from the Regular

Classroom Solely Because of Race Is Unconstitutional.

It is clear from the history of the treatment of Negroes

seeking graduate educational advantages offered by the

State of Oklahoma that the problem confronting the court

is one of exclusion. That was true in Sipuel v. Board of

Regents (92 L. Ed. 256 Adv. Sheets) and it was true in the

earliest stages of this action, when the plaintiff was excluded

13 Steele v. Louisville & Nashville HR Go., 323 U. S. 192 (1944).

14 Railway Mail Association V. Corsi, 326 U. S. 88 (1945).

16

entirely from the University of Oklahoma. It is true at the

present time, when the plaintiff, admitted to the campus

of the University, is still excluded from the classroom in

which the courses he is taking are given to other students.

Plaintiff and those other students are, presumably, entitled

to pursue the same course of instruction, at the same time,

take the same examinations and will, presumably, if they

are competent, be awarded the same degree by the Univer

sity. But during this entire period of study the plaintiff

will be excluded, physically, from the room in which other

students undertake the joint enterprise of securing an edu

cation.

The Supreme Court has dealt on many occasions with

the efforts of state agencies to exclude racial minorities

from some aspect of community life. Recently, in Shelley

v. Kraemer, supra, the Supreme Court found that the state

courts could not exclude Negroes from residential areas by

enforcement of racial restrictive covenants entered into by

white residents. Thirty years earlier the Court had held

that such exclusion could not be accomplished by the enact

ment of municipal ordinances fixing the boundaries of white

and Negro residential areas. Buchanan v. Warley, supra.

If the state may not, through any of its officials enforce

the exclusion of a Negro from a neighborhood where he

has “ qualified” as a resident by purchasing a home from a

willing seller, by what logic can the state be justified in

excluding from a classroom a Negro who has qualified and

been admitted as a student in that class.

The Supreme Court has held that exclusion of Negroes

from residential areas by state action could not be justified

by resort to the police power of the state in an effort to

prevent race conflict (Buchanan v. Warley, supra) nor by

the sanctity of private contracts (Shelley v. Kraemer,

supra).

17

It is apparent that the power of the president of a state

university acting upon an order of an administrative board

of the state to require a qualified Negro student, duly ad

mitted to a class in the University, to remain physically

excluded at all times from the room in which that class is

conducted must be tested against the same constitutional

limitations which apply to the power of other state agencies

to exclude a Negro from a home he has purchased.

As the Supreme Court stated in the Shelley case:

“ Only recently this Court has had occasion to de

clare that a state law which denied equal enjoyment of

property rights to a designated class of citizens of

specified race and ancestry, was not a legitimate exer

cise of the state’s police power but violated the guar

anty of the equal protection of the laws. Oyama v.

California, 332 U. S. 633 (1948)” 92 L. Ed. 856.

The record of this case is barren of any attempt to define

the source of the extraordinary power claimed by the State

of Oklahoma. Clearly the trial court was not justified in

resorting to a vague public policy, not in itself shown to

be reasonable, for when no basis is shown for a classifica

tion, the courts may not “ conjure up” justifications. May

flower Farms v. Ten Eyck, 297 U. S. 266 (1935).

The two basic considerations used by the Supreme Court

in the Shelley case (supra) to determine whether the Four

teenth Amendment had been violated were first whether the

action was state action and second whether the race of the

parties was the determining factor in that action. Those

two questions having been affirmatively answered the pro

hibitions of the Fourteenth Amendment automatically at

tached to the action of the state. Thus, the Court stated:

“ It should be observed that these covenants do not

seek to proscribe any particular use of the affected

properties. Use of the properties for residential occu

18

pancy, as such, is not forbidden. The restrictions of

these agreements, rather, are directed toward a desig

nated class of persons and seek to determine who may

and who may not own or make use of the properties for

residential purposes. The excluded class is defined

wholly in terms of race or color; ‘ simply that and noth

ing more.’ . . . (92 L. Ed. 850, Adv. Sheets.)

“ We have noted that freedom from discrimination

by the States in the enjoyment of property rights was

among the basic objectives sought to be effectuated by

the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment. That such

discrimination has occurred in these cases is clear.

Because of the race or color of these petitioners they

have been denied rights of ownership or occupancy

enjoyed as a matter of course by other citizens, of

different race or color.” (92 L. Ed. 855, Adv. Sheets.)

The United States Supreme Court has also given pro

tection to those substantive rights which it has found to be

included within the liberty guaranteed by the due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Myers v. Nebraska,

262 U. S. 390 (1922); Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S.

510, (1925). In each of these cases the Court found that the

state, notwithstanding its power to regulate all schools, had

interfered with a right belonging to the individuals pro

tected by this clause and which was beyond the power of

the state to regulate.

In this case, plaintiff sought to invoke the protection of

the federal constitution against unequal treatment and also

against the deprivation of his liberty or right to enjoy

facilities afforded by the state and open to members of

another group.

The rights created by the Fourteenth Amendment are, by

its terms, guaranteed to the individual. The rights estab

lished are personal rights—personal to the individual not to

racial groups.

The plaintiff has been seeking to enforce his right to

19

obtain graduate education at the University of Oklahoma

on the same basis as all other qualified students and sub

ject only to the same rules and regulations. This right can

only be enjoyed by his admission to the only class and class

room where these courses are taught. However, plaintiff

is still excluded from the classroom and is only permitted

to participate in the class from another room through an

open door, thereby being subjected to rules and regula

tions applicable solely to him because of his race and color.

Thus the plaintiff’s individual right was qualified on a group

racial basis, set aside by the State of Oklahoma and thereby

effectively denied to the plaintiff.

D, The Conflict Between Early and Recent Decisions of the

Supreme Court Defining the Limits of State Power to

Make Classifications Based On Race under the Four

teenth Amendment Should Be Resolved.

In this case the defendants put in no evidence to show

any basis for the exclusion of the plaintiff , from, the regular

classroom. They relied solely upon their alleged right to

do so because of race and color.

In denying the plaintiff the relief requested this Court

held that the Fourteenth Amendment ‘ ‘ does not authorize us

to obliterate social or racial distinctions which the State

has traditionally recognized as a basis for classification for

purposes of education and other public ministrations. The

Fourteenth Amendment does not abolish distinctions based

upon race or color, nor was it intended to enforce social

equality between classes and races . . . It is the duty

of this Court to honor the public policy of the State in mat

ters relating to its internal social affairs quite as much as

it is our duty to vindicate the supreme law of the land.”

It is thereby clear that the basic error in the decision in this

case was the reliance on the theory set forth in the case of

2 0

Plessy v. Ferguson, supra, rather than the basic pronounce

ments of the United States Supreme Court in the more re

cent cases.

In the case of Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 (1896)

the majority of the Supreme Court, in upholding the validity

of a state statute requiring segregation of the races in intra

state transportation, stated:

"T he object of the amendment (Fourteenth) was

undoubtedly to enforce the absolute equality of the two

races before the law, but in the nature of things it could

not have been intended to abolish distinctions based

upon color, or to enforce social, as distinguished from

political, equality, or a commingling of the two races

upon terms unsatisfactory to either.” (163 U. S. 537,

544)

In the case of Buchanan v. Warley, supra, the Supreme

Court, in declaring invalid an ordinance requiring resi

dential segregation, stated:

" I t is the purpose of such enactments, and it is

frankly avowed it will be their ultimate effect, to re

quire by law, at least in residential districts, the com

pulsory separation of the races on account of color.

Such action is said to be essential to the maintenance

of the purity of the races, although it is to be noted in

the ordinance under consideration that the employment

of colored servants in white families is permitted, and

nearby residences of colored persons not coming within

the blocks, as defined in the ordinance, are not pro

hibited.

"The case presented does not deal with an attempt

to prohibit the amalgamation of the races. The right

which the ordinance annulled was the civil right of a

white man to dispose of his property if he saw fit to do

so to a person of color, and of a colored person to make

such disposition to a white person.

" I t is urged that this proposed segregation will pro

2 1

mote the public peace by preventing race conflicts. De

sirable as this is, and important as is the preservation

of the public peace, this aim cannot be accomplished by

laws or ordinances which deny rights created or pro

tected by the Federal Constitution. ’ ’ 245 U. S. 81.

The rationale of the I’less// case as to classification of

Negroes has always been in direct conflict not only with

the principles set forth in the Buchanan ease, supra, as to

residential segregation but has also been in conflict with

other decisions of the Supreme Court on the limitations of

the Fourteenth Amendment on the right of states to make

classifications.15

More reecnt decisions of the Supreme Court set out above

have made it clear that the basis for the decision in the

Plessy case that the Fourteenth Amendment ‘ ‘ could not have

been intended to abolish distinctions based upon color” is no

longer valid.

In this case the right which the plaintiff asserts is a right

in keeping with these latter decisions of the Supreme Court.

The trial court, again following the doctrines of the

Plessy ease, upheld the racial classification because it “ rests

upon a reasonable basis, having its foundation in the pub

lic policy of the state.” This ruling is in direct conflict with

prior decisions of the Supreme Court.

In the Buchanan case the Supreme Court stated “ . . .

it is equally well established that the police power, broad

15 In order that a classification may meet the prohibitions of the equal

protection clause, the Supreme Court has required that the state must show:

first, that the purpose sought to be achieved by the classification is within

the scope of state power, and second, that the classification bears a reason

able relationship to the end sought by the legislation.

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S. 535 (1942); South Carolina Highway

Dept. v. Barnwell, 303 U. S. 177 (1938); Great A. & P. Co. v. Grosjean,

301 U. S. 412 (1937) ; Liggett v. Lee, 288 U. S. 517 (1933) ; Patsone V.

Pennsylvania, 232 U. S. 138 (1914) ; Rosenthal v. New York, 226 U. S.

260 (1912) ; Atchison RR v. Matthews, 174 U. S. 96 (1899).

22

as it is, cannot justify the passage of a law or ordinance

which runs counter to the limitations of the Federal Con

stitutions; that principle has been so frequently affirmed

in this court that we need not stop.to cite the cases.” (245

IT. S. 66, 74)

In the Shelley case the Supreme Court stated “ . . . Nor

may the discriminations imposed by the state courts in these

cases be justified as proper exercises of state police power”

(92 L. Ed. Adv. Sheets 845, 856).

In the Plessy case, there was enunciated the now anti

quated and discarded doctrine which has been relied upon

by various states to sustain the constitutionality of statutes

requiring the segregation of the races in public education.

In the light of morei recent decisions of the United States

Supreme Court, that case can no longer be used as an

authority for the type of discrimination here in issue.

The recent cases, standing as they do for the principle that

racial classification by government is unconstitutional be

cause “ (d)istinctions between citizens solely because of their

ancestry are by their nature odious to a free people,” have

completely repudiated the doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson

that the Fourteenth Amendment ‘ ‘ could not have been in

tended to abolish distinctions based upon color.”

The important governmental function of public educa

tion is seriously handicapped by the blind adherence to the

doctrine set forth in the Plessy case. Just as the conflict

between the decisions of Grovey v. Townsend, 295 U. S. 45,

and United States v. Classic, 313 U. S. 299, had to be re

solved in Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649, the conflict be

tween the Plessy case and the latter cases set out above

must be resolved.

That the questions here presented are substantial is made

23

even clearer by the Fifth recommendation of the Report of

the President’s Committee on Civil Rights.

“ The separate but equal doctrine has failed in three

important respects. First, it is inconsistent with the

fundamental equalitarianism of the American way of

life in that it marks groups with the brand of inferior

status. Secondly, where it has been followed, the re

sults have been separate and unequal facilities for

minority peoples. Finally, it has kept people apart

despite incontrovertible evidence that an environment

favorable to civil rights is fostered whenever groups

are permitted to live and work together. There is no

adequate defense of segregation.” 18

Conclusion

Negroes seeking public education in Oklahoma and other

southern States have always been subjected to varying de

grees of discrimination—all based on race and color alone. In

this case the plaintiff is seeking to enforce the right to an

education by the State of Oklahoma on the same basis as

other students subject only to rules and regulations ap

plicable to all. On the other hand, the State of Oklahoma

has insisted upon determining his right on the basis of a

racial classification. First it was complete exclusion from

the university—later it was the exclusion from the class

room. Plaintiff is still the victim of the same racial classifi

cation. His individual right is lost in the racial group

classification pursuant to the alleged State public policy

derived from statutes heretofore declared unconstitutional.

The evil complained of is the racial classification which the

Fourteenth Amendment was intended to abolish. The ques

tion herein involved is not only substantial within the mean

18 Report of the President’s Committee on Civil Rights, To Secure These

Bights, Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C., 1947, p. 166.

24

ing of the jurisdictional statutes but is basic to two of the

most vital areas of our democratic process—public educa

tion and the individual’s right to complete equality before

the law.

Respectfully submitted,

A mos T. H aul,

107Y2 N. Greenwood Avenue,

Tulsa, Oklahoma;

Thurgood Marshall,

20 West 40th Street,

New York 18, N. Y.,

Attorneys for Plaintiff.

R obert L. Carter,

Constance Baker M otley,

Marian W . Perry,

F ranklin H. W illiams,

20 West 40th Street,

New York 18, N. Y.

Of Counsel.

25

Oklahoma Statutes Involved

70 0.8.1941, Section 455. It shall be unlawful for any per

son, corporation or association of persons, to maintain or

operate any college, school or institution of this state where

persons of both white and colored races are received as

pupils for instruction, and any person or corporation who

shall operate or maintain any such college, school or institu

tion in violation hereof, shall be deemed guilty of a misde

meanor, and upon conviction thereof shall be fined not less

than one hundred dollars nor more than five hundred dol

lars, and each day such school, college or institution shall be

open and maintained shall be deemed a separate offense.

(L. 1913, ch. 219, p. 572, art. 15, Section 5.)

70 O.S. 1941, Section 456. Any instructor who shall teach

in any school, college or institution where members of the

white race and colored race are received and enrolled as

pupils for instruction, shall be deemed guilty of a misde

meanor, and upon conviction thereof shall be fined in any

sum not less than ten dollars nor more than fifty dollars for

each offense, and each day any instructor shall continue to

teach in any such college, school or institution, shall be con

sidered a separate offense. (L. 1913, ch. 219, p. 572, art.

15, Section 6.)

70 O.S. 1941, Section 457. It shall be unlawful for any

white person to attend any school, college or institution,

where colored persons are received as pupils for instruction,

and any one so offending shall be fined not less than five

dollars, nor more than twenty dollars for each offense, and

each day such person so offends, as herein provided, shall

be deemed a distinct and separate offense; provided, that

nothing in this article shall be construed as to prevent any

private school, college or institution of learning from main

taining a separate or distinct branch thereof in a different

locality. (L. 1913, ch. 219, p. 572, art. 15, Section 7.)

APPENDIX “A”

26

Order Involved

From the minutes of a special meeting of the Regents of

the University of Oklahoma held on Sunday, October 10,

1948.

Regent Emery: “ I now offer the following motion and

move its adoption: ‘ That the Board of Regents of the Uni

versity of Oklahoma authorize and direct the President of

the University, and the appropriate officials of the Uni

versity to grant the application for admission to the Grad

uate College of G. W. McLaurin in time for Mr. McLaurin

to enroll at the beginning of the term, under such rules and

regulations as to segregation as the President of the Uni

versity shall consider to afford to Mr. G. W. McLaurin

substantially equal educational opportunities as are af

forded to other persons seeking the same education in the

Graduate College, and that the President of the University

promulgate such regulations’.”

A roll call vote was asked for with the following voting

Aye:

Regent Emery

Regent Shepler

Regent White

Regent Benedum

Regent Deacon

Regent McBride

Absent:

Regent Noble.

APPENDIX “B”

27

No. 4039 (Civil)

G. W. M cLaurin, Plaintiff,

APPENDIX “C”

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR

THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF OKLAHOMA

vs.

Oklahoma State Regents fob H igher E ducation, et al.,

Defendants

Journal Entry

Be it remembered that this cause came on regularly for

hearing before this duly constituted court on August 23,

1948. The plaintiff appeared in person and by his attorneys

Thurgood Marshall and Amos T. Hall. The defendants

appeared either in person, or by and through the Honorable

Mac Q. Williamson, Attorney General of the State of Okla

homa, Fred Hansen and George T. Montgomery, Assistant

Attorneys General. Testimony was introduced, argument

was had, and the matter was continued until September 24,

1948, and was thereafter continued until September 29,1948.

Further evidence was taken, argument heard, and the cause

finally submitted.

On this, the 6 day of October, 1948, it is ordered and de

creed that insofar as Sections 455, 456 and 457, 70 O. S. 1941,

are sought to be applied and enforced in this particular case,

they are unconstitutional and unenforceable.

The court refrains at this time, however, from issuing or

granting any injunctive relief, but jurisdiction over the

subject matter is reserved for the purpose of entering any

such further orders as may be deemed proper in the circum

2 8

stances to secure to the plaintiff the redress he seeks under

the Constitution and laws of the United States.

Done this 6 day of October, 1948.

(S.) A lfred P. M urrah,

Judge of the U. 8. Court of Appeals.

(S.) E dgar S. V aught,

U. S. District Judge.

(S.) B ower Broaddus,

U. S. District Judge.

Endorsed: Filed October 6, 1948. Theodore M. Filson,

Clerk.

APPENDIX “D”

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR

THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF OKLAHOMA

No. 4039 (Civil)

G-. W. M cL aurin, Plaintiff,

vs.

Oklahoma State Regents for H igher E ducation, et al.,

Defendants

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

Preliminary Statement

By this suit, we are asked to enjoin the defendants from

refusing to admit the plaintiff to the University of Okla

homa, for the purpose of pursuing a postgraduate course

in education leading toward a doctor’s degree. It is said

that although having made timely application for admis

sion, and being morally and scholastically qualified, he has

been denied admission solely because, as a member of the

Negro race, the laws of Oklahoma forbid his admission

under criminal penalty. It is said that in these circum

stances, refusal to admit the plaintiff to the University of

29

Oklahoma, for the purpose of pursuing the course of study

he seeks, is a deprivation of his rights to the equal protec

tion of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States.

Findings of Fact

I

In accordance with the stipulation, the court finds that the

University of Oklahoma is an educational institution main

tained by the taxpayers of the State, from funds derived

from uniform taxation, and that it is the only educational

institution supported by public taxation in which the plain

tiff can pursue a postgraduate course leading to a doctor’s

degree in education.

II

That during the enrollment period for the second semester

for the 1947-1948 school term, plaintiff applied for admis

sion to the University for the purpose of taking such courses

which would entitle him to a doctor’s degree in education,

and that at the time of his application, he possessed and

still possesses all of the scholastic and moral qualifications

prescribed by the University of Oklahoma for admission to

the courses he seeks to pursue, and that he was denied

admission to the University on February 2, 1948, solely

because as a member of the Negro race, the applicable laws

of Oklahoma (70 0. S. 1941, Sections 455, 456 and 457) make

it a criminal offense for any person to operate a school or

college or any educational institution where persons of both

white and colored races are received as pupils for instruc

tion, or for any instructors to teach in, or any white person

to attend, any such school.

Conclusions of Law

I

This suit arises under the Constitution and laws of the

United States, and seeks redress for the deprivation of civil

rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. The

court is therefore vested with jurisdiction, regardless of

30

diversity of citizenship or amount in controversy. Hague

v. C. I. 0., 307 IT. S. 496, 514; Douglas v. Jeannette, 319 U. S.

157. Since a temporary injunction against the enforcement

of the State laws on the grounds of their unconstitutionality

is sought, the subject matter is properly cognizable by a

three judge court under Section 266 of the Judicial Code,

28 U. S. C. A. 380.

II

We hold, in conformity with the equal protection clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment, that the plaintiff is entitled

to secure a postgraduate course of study in education lead

ing to a doctor’s degree in this State in a State institution,

and that he is entitled to secure it as soon as it is afforded

to any other applicant. Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332

U. S. 631; Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337.

That such educational facilities are now being offered to

and received by other applicants at the University of Okla

homa, and that although timely and appropriate application

has been made therefore, to this time such facilities have

been denied this plaintiff.

III

The court is of the opinion that insofar as any statute or

law of the State of Oklahoma denies or deprives this plain

tiff admission to the University of Oklahoma for the pur

pose of pursuing the course of study he seeks, it is unconsti

tutional and unenforceable. This does not mean, however,

that the segregation laws of Oklahoma are incapable of

constitutional enforcement. We simply hold that insofar

as they are sought to be enforced in this particular case, they

are inoperative.

IV

Our attention has been called to and we have seen a state

ment of the Governor of this State in which he commits the

State to a certain course of action, designed to afford equal

segregated facilities to this plaintiff and members of his

Race in compliance with the constitutional requirements.

In that connection, we think it appropriate to state that it

is not our function to say what the State shall do in order

31

to comply with its acknowledged responsibilities to its

citizens. Rather it is our function to determine whether

what has been done and what is being done meets the con

stitutional mandate.

V

In the performance of this important function, we sit as

a court of equity, with power to fashion our decree in accord

ance with right and justice under the law. Accordingly,

we refrain at this time from issuing or granting any injunc

tive relief, on the assumption that the law having been

declared, the State will comply. We retain jurisdiction of

this case, however, with full power to issue such further

orders and decrees as may be deemed necessary and proper

to secure to this plaintiff the equal protection of the laws,

which, translated into terms of this lawsuit, means equal

educational facilities.

(S .) A lfred P. M u erah ,

Judge of the U. IS'. Court of Appeals.

(S.) E dgar S. V au g h t ,

U. S. District Judge.

(S .) B ower B roaddus,

U. S’. District Judge.

Endorsed: Filed October 6, 1948. Theodore M. Filson,

Clerk.

32

No. 4039 (Civil)

G. W . M cL aurin , Plaintiff,

vs.

Oklahoma State Regents foe H igher E ducation, et al.,

Defendants

Journal Entry

Be it remembered that this cause came on for further con

sideration on the 25th day of October, 1948. The plaintiff,

McLaurin, appeared in person and by his counsel, Thur-

good Marshall and Amos T. Hall. The applicant, Mauderie

Florence Hancock Wilson, appeared in person and by the

same counsel of record. The defendants appeared either

in person or by and through the Attorney General of the

State of Oklahoma, the Honorable Mac Q. Williamson, and

Assistant Attorneys General Fred Hansen and George T.

Montgomery. Testimony was heard, and the case was fin

ally submitted on briefs of the parties.

Upon consideration of the evidence, argument and briefs,

it is ordered that the relief now sought by the Plaintiff

McLaurin should be and the same is hereby denied.

It is further ordered that the relief prayed for by the

applicant, Wilson, should be and the same is thereby denied.

The complaint as to each of the parties is dismissed and

judgment is entered for the defendants.

A lfred P. Mure ah .

E dgar S. V aught.

B ower Broaddus.

Endorsed: Filed Nov. 22, 1948. Theodore M. Filson,

Clerk, by Margaret P. Blair, Deputy.

APPENDIX “E”

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR

THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF OKLAHOMA

33

No. 4039 (Civil)

Gr. W. M cLaurin, Plaintiff,

APPENDIX “F”

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR

THE W ESTERN DISTRICT OF OKLAHOMA

vs.

Oklahoma State Regents for H igher E ducation, et al.,

Defendants

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

Preliminary Statement

At a former hearing of this cause, we held the segrega

tion laws of the State of Oklahoma (70 0. S. 1941, Sections,

455, 456 and 457) unconstitutional and inoperative insofar

as they deprived the plaintiff of his constitutional right to

pursue the course of study he sought at the University of

Oklahoma. We were careful, however, to confine our decree

to the particular facts before us, while recognizing the

power of the State to pursue its own social policies regard

ing segregation in conformity with the equal protection of

the laws. We expressly refrained from granting injunc

tive relief, on the assumption that the State statutory im

pediments to equal educational facilities having been de

clared inoperative, the State would provide such facilities

in obedience to the constitutional mandate.

Now this eause comes on for further consideration on

complaint of the plaintiff, to the effect that although he has

been admitted to the University o f Oklahoma, and to the

course of study he sought, the segregated conditions under

which he was admitted, and is required to pursue his course

of study, continue to deprive him of equal educational facil

ities in conformity with the Fourteenth Amendment.

34

F indings of F act

I

Tlie undisputed evidence is that subsequent to our decree

in this case, plaintiff was admitted to the University of

Oklahoma, and to the same classes as those pursuing the

same courses. He is required, however, to sit at a desig

nated desk in or near a v?ide opening into the classroom.

From this position, he is as near to the instructor as the

majority of the other students in the classroom, and he can

see and hear the instructor and the other students in the

main classroom as well as any other student. His objection

to these facilities is that to he thus segregated from the

other students so interferes with his powers of concentra

tion as to make study difficult, if not impossible, thereby de

priving him of the equal educational facilities. He says in

effect that only if he is permitted to choose his seat as any

other student, can he have equal educational facilities.

II

He is accorded access to and use of the school library as

other students, except if he remains in the library to study,

he is required to take his books to a designated desk on the

mezzanine floor. All other students who use the library

may choose any available seat in the reading room in the

library, but a majority find it necessary to study elsewhere

because of a lack of seating capacity in the library. The

plaintiff says that this secluded and segregated arrange

ment tends to set him apart from other students and hence

to deprive him of equal facilities.

III

He is admitted to the school cafeteria, where he is served

the same food as other students, but at a different time and

at a designated table. He does not object to the food, the

dining facilities, or the hour served, but to the segregated

conditions under which he is served.

In the language of his counsel, he complains that “ his

required isolation from all other students, solely because

35

of the accident of birth * * * creates a mental discom

fiture, which makes concentration and study difficult, if not

impossible * * * ” ; that the enforcement of these regu

lations places upon him “ a badge of inferiority which affects

his relationship, both to his fellow students, and to his pro

fessors.”

ConcLUSions on Law

I

It is said that since the segregation laws have been declared

inoperative, the University is without authority to require

the plaintiff to attend classes under the segregated condi

tions. But the authority of the University to impose segre

gation is of concern to this court only if the exercise of that

authority amounts to a deprivation of a federal right. See

Screws v. United States, 325 U. S. 91.

The Constitution from which this court derives its juris

diction does not authorize us to obliterate social or racial

distinctions which the State has traditionally recognized as

a basis for classification for purposes of education and other

public ministrations. The Fourteenth Amendment does not

abolish distinctions based upon, race or color, nor was it in

tended to enforce social equality between classes and races.

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 ; Cummings v. United

States, 175 U. S. 528; Gang Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78; Mis

souri ex rel Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 37. It is only when

such distinctions are made the basis for discrimination and

unequal treatment before the law that the Fourteenth

Amendment intervenes. Trusts v. Raich, 293 U. S. 33, 42. It

is the duty of this court to honor the public policy of the

State in matters relating to its internal social affairs quite as

much as it is our duty to vindicate the supreme law of the

land.

I l l

The Oklahoma statutes held unenforceable in the prev

ious order of this court have not been stripped of their

vitality to express the public policy of the State in respect

to matters of social concern. The segregation condemned

in Westminister School District v. Mendez, 161 F. 2d 774,

was found to be “ wholly inconsistent ’ ’ with the public policy

36

of the State of California, while in our case the segregation

based upon racial distinctions is in accord with the deeply

rooted social policy of the State of Oklahoma.

IY

The plaintiff is now being afforded the same educational

facilities as other students at the University of Oklahoma.

And, while conceivably the same facilities might be afforded

under conditions so odious as to amount to a denial of equal

protection of the law, we cannot find any justifiably legal

basis for the mental discomfiture which the plaintiff says

deprives him of equal educational facilities here. We con

clude therefore that the classification, based upon racial

distinctions, as recognized and enforced by the regulations

of the University of Oklahoma, rests upon a reasonable basis,

having its foundation in the public policy of the State, and

does not therefore operate to deprive this plaintiff of the

equal protection of the laws. The relief he now seeks is

accordingly denied.

A pplication op M rs. Maude F lorence H ancock W ilson

Mrs. Maude Florence Hancock Wilson, claiming to be a

member of the same class and similarly situated with the

plaintiff McLaurin, has renewed her application for entrance

to the University of Oklahoma to pursue a course of study

in social work, and upon being denied entrance she comes

here seeking the same relief sought by McLaurin in his class

action.

The facts are that Mrs. Wilson applied for admission to

the University of Oklahoma on January 28, 1948, for the

purpose of studying for a master’s degree in sociology. She

was morally and scholastically qualified to pursue this

course of study, and it was unavailable at any separate

school within the State of Oklahoma. When her applica

tion for entrance was denied, solely because the laws of

Oklahoma forbade it, she filed suit in the District Court of

Cleveland County, Oklahoma, in May 1948, for a writ of

mandamus to compel her admission on substantially the

same grounds now asserted here. Having been denied relief

in the District Court, she has perfected her appeal to the

37

Supreme Court of Oklahoma, and that appeal is now pending

and undecided. She did not renew her application for ad

mission to the University until October 15, 1948, two days

after registration was closed to any applicant for any

course of study at the University.

Having elected to pursue an equally adequate remedy in

the courts of the State for the purpose of securing equal

protection of the laws, and is now actively pursuing that

remedy, she is not similarly situated with the plaintiff, Mc-

Laurin. Moreover, the course of study she now seeks to pur

sue is not the same as the one originally sought, and not

having applied for admission until all other persons would

have been similarly denied admission, she is not within the

class for which this suit is prosecuted. The relief sought

by her is, therefore, denied.

A lfred P. Mtjrrah.

E dgar S. Y aught.

B ower B roaddus.

Endorsed: Piled Nov. 22, 1948. Theodore M. Filson,

Clerk, by Margaret P. Blair, Deputy.

(1390)