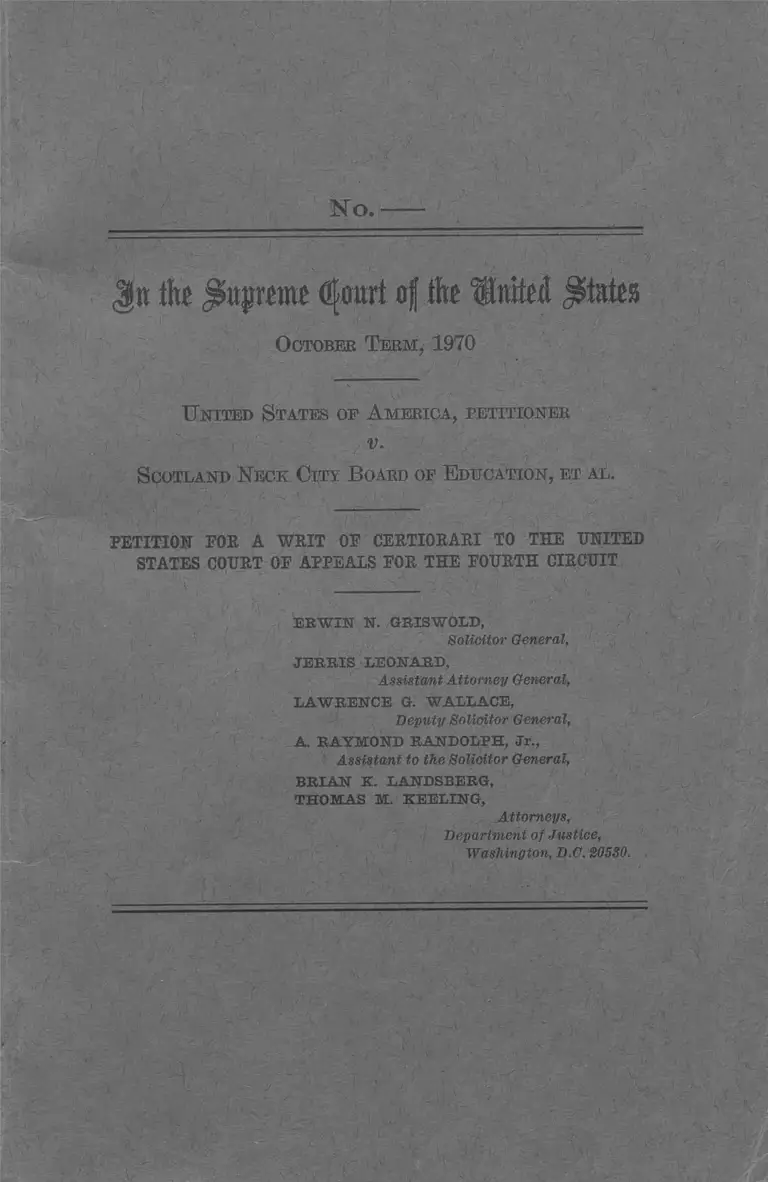

United States v. Scotland Neck City Board of Education Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

April 30, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Scotland Neck City Board of Education Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1971. b8299ed0-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0b2b4e73-ae6e-4302-8e10-fb9597f415f3/united-states-v-scotland-neck-city-board-of-education-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

Jit t o j&tpvetne dj-ourt of t o United States

October Term, 1970

U nited States or A merica, petitioner

v.

Scotland Neck City B oard op E ducation, et al.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED

STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

ERWIN N. GRISWOLD,

Solicitor General,

JERRIS LEONARD,

Assistant Attorney General,

LAWRENCE G. WALLACE,

Deputy Solicitor General,

A. RAYMOND RANDOLPH, Jr.,

Assistant to the Solicitor General,

BRIAN K. LANDSBERG,

THOMAS M. KEELING,

Attorneys,

Department of Justice,

Washington, D.O. 20530. .

IN D E X

Opinions below_________________________________

Jurisdiction____________________________________

Question presented_____________________________

Constitutional and statutory provisions involved-.

Statement_____________________________________

Reasons for granting the writ___________________

Conclusion_____________________________________

Appendix A ____________________________________

Appendix B ________________ ___________________

Appendix C____________________________________

Appendix D ____________________________________

Appendix E ____________________________________

Appendix F ____________________________________

Appendix G____________________________________

Appendix H____________________________________

Page

1

1

2

2

2

7

13

la

19a

56a

62a

91a

92a

99a

101a

CITATIONS

Cases:

Alexander v. County Board of Education, 396

U.S. 19__________________________________ 10

Aytch and United States v. Mitchell, C.A. No.

PB 70-C-127, E.D. Ark., decided January

15,1971_________ 11

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483___ 9,10

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294,__ 10

Buchanan v. War ley, 245 U.S. 60_____________ 10

Burleson v. County Board of Election Com

missioners of Jefferson County, 308 F. Supp.

352, affirmed 432 F. 2d 1356_____________ 10, 11

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1________________ 8, 9

Green v. School Board of New Kent County, 391

U.S. 430_______________________________ 3, 9, 10

Hawkins v. Town of Shaw, No. 29013, C.A. 5,

decided January 28, 1971__________________ 12

Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States, 379

U.S. 241________ 10

(i)

422- 400— 71-----------1

n

Cases—Continued

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385-------------—

Jackson v. Godwin, 400 F. 2d 529-----------------

Kennedy Park Homes Association, Inc. and

United States v. City of Lackawanna, 436 F.

2d 108, certiorari denied April 5, 1971, No.

1319, Oct. Term, 1970------------------------------

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1----------------------

McLaughlin v. Florida, 579 U.S. 184----------

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128------------------------

Swann v. Board of Education, No. 281, Oct.

Term, 1970, decided April 20,1971---------- -

Turner v. Warren County Board of Education,

C.A. No. 1482, E.D. N.C., affirmed sub nom.

Turner v. Littleton-Lake Gaston School Dis

trict, No. 14,990 C.A. 4, decided March 23,

1971____________________________________

Page

10

12

12

9

9

9

8,10

United States v. State of Texas, 321 F. Supp.

1043, appeal pending, C.A. 5, No. 71-1061 _ _ 11

Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia, N o.

14,552, C.A. 4, decided March 23, 1971-J- 7,8

Wright v. City of Brighton, Alabama, No.

29,262, C.A. 5, decided March 16, 1971___ 12

Constitution and statutes:

United States Constitution, Fourteenth

Amendment_____________________________ 2, 8

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 407, 42

U.S.C. 2000c-6_______________________ 2, 3, 5, 99

28 U.S.C. 1345_____________________________ 5

1969 Session Laws of North Carolina, Chapter

31_____________________________ 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 101

Jtt the Supreme (fiourt of the Suited States

October Term, 1970

M o .------

U nited States of A merica, petitioner

v.

Scotland K eck City B oard of Education, et al.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED

STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

The Solicitor General, on behalf o f the United

States, petitions for a writ of certiorari to review the

judgment of the United States Court o f Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit in this ease.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the court of appeals sitting en banc

(App. A, infra, pp. la-18a) and the dissenting opin

ions (App. B, infra, pp. 27a-43a and pp. 44a-55a) are

not yet reported.

The opinion and order of the district court entered

on motion for preliminary injunction (App. C, infra,

pp. 56a-61a) are not reported; the opinion and order

on permanent injunction (App. D, infra, pp. 62a-90a)

are reported at 314 F. Supp. 65.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the court of appeals (App. E,

infra, p. 91a) was entered on March 23, 1971. The

■CD

9

jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C.

1254(1).

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether the court of appeals erred in holding that

a State may split desegregating school districts into

multiple districts, even if the establishment of a

unitary system is thereby impaired, unless the “ pri

mary purpose” of the split is to retain as much sepa

ration of the races as possible.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED

Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States provides as follows:

All persons born or naturalized in the United

States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof,

are citizens of the United States and of the

State wherein they reside. Uo State shall make

or enforce any law which shall abridge the

privileges or immunities of citizens of the

United States; nor shall any State deprive any

person of life, liberty, or property, without due

process of law; nor deny to any person within

its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Section 407 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42

U.S.C. 2000c-6, is set out in Appendix G-, infra, p.

99 a.

Chapter 31 of the 1969 Session Laws of North

Carolina, is set out in Appendix H, infra, p. 101a.

STATEMENT

Scotland Neck, North Carolina, is a town with a

population of approximately 3000 located in the

southeastern portion of Halifax County. The schools

3

in Scotland Neck have been operated as part of the

Halifax County Administrative Unit since 1936.

Halifax County ran a completely segregated dual

school system until 1965, when it adopted a freedom-

of-choice desegregation plan (App. A 8a). Little in

tegration followed (ibid.). After this Court’s decision

in 1968 in Green v. School Board of New Kent

County, 391 U.S. 430, the Department of Justice, pur

suant to 42 U.S.C. 2000c-6, informed the Halifax

County Board that the operation of its schools did

not comply with constitutional requirements. Negotia

tions with the Board resulted in a plan to disestablish

the county’s dual school system by the beginning of

the 1969-70 school year. Interim steps were to be

taken in 1968-69.1 (App. A 9a.) The plan and interim

steps were given wide local publicity (App. D 67a).

As a result of renewed efforts by citizens o f Scot

land Neck a number of months after the Green

decision, a local law, Chapter 31, 1969 Session Laws

of North Carolina (App. H 101a) was enacted by

the North Carolina General Assembly on March 3,

1969.1 2 Chapter 31 provided for a new school district

bounded by the city limits of Scotland Neck, and for

a supplemental tax assessment upon approval by a

majority of the city’s voters. The voters registered

1 One such step was the combining of the 7th and 8th grades

of the previously all-black Brawley school, located near the

city limits of Scotland Neck, with the all-white junior high school

in the city (App. D 67a-68a).

2 Earlier unsuccessful attempts had been made by the citizens

of Scotland Neck to have a law similar to Chapter 31 passed.

(See App. D 69a).

4

their approval in a special election on April 8, 1969,

and some preliminary steps were taken so that the

newly-created school district— Scotland Neck City

Administrative Unit—could start operation at the

beginning of the 1969-70 school year (App. D 72a, 73a).

Shortly thereafter, the Halifax County Board de

cided not to carry out the previously adopted desegre

gation plan (App. A 9a).

Chapter 31 ’s implementation would have resulted in

carving out of the Halifax County system, which had a

student population of 10,655, a smaller school district

of 695 students. The predominantly black county

system consisted of 22 percent white students, 77 per

cent black, and 1 percent Indian; by comparison, the

new, smaller district would have consisted of 57.4

percent white students and 42.6 percent black. (App.

I) 14a-15a). By the removal of Scotland Neck from the

larger rural area its schools had traditionally served,

the number of white children in schools in that area

would have been reduced by almost one half (from

804 to 405) and the number of black children would

have changed from 3,095 to 2,799. The County system

as a whole would then have had 9,960 students, 19

percent of whom would have been white, 80 percent

black and 1 percent Indian. (App A 14a).

Since the planned Scotland Neck schools could

accommodate 1,000 students/' but would have had 695 3

3 The schools in Scotland Neck were inadequate to accom

modate even the original 605 students; the City therefore

purchased from the County a junior high school located outside

the City’s boundaries (App. B52a).

5

pupils when Chapter 31 was implemented, the City

and the County agreed to a plan allowing County

students to transfer into the Scotland Neck system

for a fee (App. D 74a). By August 25,1969, 350 white

and 10 black students had applied to transfer into

Scotland Neck, and 44 black students had applied to

transfer out. The combined effect o f Chapter 31 and

the transfer plan would have been a Scotland Neck

system of 1,011 students, 74 percent white and 26

percent black, a Halifax County system of 9,644

students, 17 percent white, 82 percent black and 1

percent Indian, and virtually all-black enrollment

in the rural area immediately surrounding Scotland

Neck.4

1. The decisions o f the district court. The govern

ment’s complaint in this action, filed on .June 16, 1969,

under Section 407 of the Civil Rights Act o f 1964,

42 U.S.C. 2000e-6, and 28 U.S.C. 1345, sought an

order to desegregate the Halifax County school sys

tem and an injunction against the implementation of

Chapter 31. After a hearing on the government’s

motion for a preliminary injunction, the district court,

on August 25, 1969, enjoined the Scotland Neck City

Board of Education from carrying out Chapter 31

pending a hearing on the merits (App. C 56a).

4 In its amended answer to the government’s complaint, the

School Board withdrew the transfer plan and informed the

district court that it intended to allow only such transfers as

“ may be in conformity to the law and/or Court order or

orders applicable to Defendant, and in conformity to a plan

of limitation of transfers to be prepared by Defendant and

submitted to this Court.” (App. A n. 4, p. 18a.) See, also, App.

B52a (Winter, J.,dissenting).

6

On December 17 and 18, 1969, there was a con

solidated trial on the merits of the instant case and

Turner v. Warren County Board of Education (C.A.

No. 1482, E.D. N.C.),5 which presented similar ques

tions.6 The district court entered its judgment on

May 26, 1970, finding that a significant factor in the

enactment of Chapter 31 was a desire to preserve a

ratio of black to white students that would be accept

able to white parents and thereby encourage them

not to take their children out of the public school

system.7 (App. D 62a.) Further, the district court

found that the effect of Chapter 31 was to create a

refuge for white students in Halifax County that

interfered with the desegregation of Halifax County

schools and prevented the County Board of Education

from complying with court orders (App. D 89a). The

court also found that Chapter 31 served no state inter

est and, therefore, concluded that the Act was un

constitutional and its operation should be enjoined

(id. at 90a).

2. The decision of the court of appeals. On appeal

by the Scotland Neck City Board of Education and

5 The Turner case involved the carving out of two separate

city administrative units from a county system; the order and

opinion enjoining such action was affirmed sub nom. Turner v.

Littleton-Lake Gaston School District, C.A. 4, decided March 23,

1971 (App. F92a).

6 The district court permitted intervention by the Attorney

General of North Carolina, certain Haliwa Indians, and certain

black teachers in the Halifax County system (App. D 63a n. 1).

7 Two other significant factors found by the court were a

desire for more local control and a desire to increase the

expenditures for the Scotland Neck schools.

7

the Attorney General of North Carolina, the court

of appeals sitting en bancs reversed (App. A la ),

with Judges Sobeloff and Winter dissenting (App.

B 27a, 44a). The court held that Chapter 31 did not

interfere with the desegregation of the Halifax County

schools, that it did not create a white refuge, and,

following the rule formulated in Wright v. Council

of the City of Emporia (No. 14,552), decided by the

court on the same day,8 9 that two non-racial justifica

tions adequately explain the splitting-off o f Scotland

Neck, even assuming that a more even racial balance

would be more effective in creating a unitary system

in Halifax County (App. A 17a). The proposed trans

fer plan was enjoined, however, on the ground that

it would tend to resegregate the school systems

(ihid.).10

REASONS EOR GRANTING THE WRIT

As the court of appeals observed in Emporia, supra,

“ There is serious danger that the creation of new

school districts may prove to be yet another method to

8 After argument on September 16, 1970, before a panel of

three judges, the case was reargued before the court en banc

on December 7, 1970, along with the appeal in Littleton-Lake

Gaston, supra.

9 Three cases, Scotland Neck, Emporia, and Littleton-Lake

Gaston, involving basically the same issues, were decided by

the court of appeals on the same date. The rale of law formu

lated by the majority is most fully set out in Emporia, and

the dissents in the present case are appended to that opinion.

The decisions in Emporia and in Littleton-Lake Gaston are

contained, respectively, in Appendices B and F, infra.

10 A motion by the United States for a stay of the court of

appeals’ mandate in the present case pending application for

certiorari is pending in the court of appeals.

8

obstruct the transition from racially separated school

systems to school systems in which no child is denied

the right to attend a school on the basis of race” (App.

B 21a. Of. Swann v. Board of Education, No. 281,

this Term, decided April 20, 1971, slip op. at 9. This

case raises significant questions with respect to seced

ing school districts and the requirements of the Four

teenth Amendment.

The court of appeals here applied the test it formu

lated in the Emporia case (App. B 21a ):

I f the creation of a new school district is de

signed to further the aim of providing qua!it}7

education and is attended secondarily by a modi

fication of the racial balance, short of resegre

gation, the federal courts should not interfere.

If, however, the primary purpose for creating

a new school district is to retain as much of

separation of the races as possible, the state has

violated its affirmative constitutional duty to

end state supported segregation.

This ‘ ‘ primary purpose” test is, we submit, seri

ously inadequate for fulfillment of the mandate of the

Fourteenth Amendment and at variance with the de

cisions of this Court. It encourages whites in school

districts having a substantial black student popula

tion to carve out as independent districts areas that

are predominantly white and, in so doing, to mask the

true purpose by devising other justifications. Compare

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1,17. The dissenting judges

in the court of appeals correctly observed that under

the majority’s test the constitutional mandate will be

easily avoided (App. B 30a, 45a-46a).

9

In holding that “ [s] eparate educational facilities are

inherently unequal,” Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U.S. .483, 495, this Court did not distinguish be

tween racial segregation with a 40 percent racial pur

pose and racial segregation with a 60 percent racial

purpose. Indeed, however innocent its motives, a state

may not simply ignore the racial consequences of its

actions, for it has long been settled that “ [w]hat

the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits is racial dis

crimination * * * whether accomplished ingeniously

or ingenuously * * Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128,

132. See Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1,17.

Accordingly, when the state’s action produces racial

segregation in the public schools, the courts must

consider its constitutionality in light of the set

ting of the Act (for example, whether it took place in

the historical setting of state-imposed segregation),

the available alternatives (whether the Act’s legiti

mate objectives could be accomplished by means hav

ing a less adverse racial impact), and the magnitude

of the state’s interest in pursuing the particular

course of action. See, e.g., Green v. School Board of New

Kent County, 391 U.S. 430; compare McLaughlin v.

Florida, 379 U.S. 184; Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1.

When, as here, a dual school system is created by

the “ simple expedient of labeling the two sets of

schools as separate districts” 11— one with a 57:43

white to Mack ratio, the other with a 19: 80 ratio— that

is, when the state’s action impedes full realization of 11

11 Judge Sobeloff, dissenting (App. B 36a).

10

the promise of Brown, that action can be upheld only

if the state can show a compelling justification for it.

In so analyzing the secession of Scotland Neck from

the Halifax County school system, the dissenting

judges in the court of appeals and the district court

found no such justification (App. B 37a; 50a-53a;

App. D 90a). W e agree.

In addition, the standard applied by the court of

appeals will significantly weaken the ability of dis

trict courts to use their equitable powers as contem

plated by this Court in Brown v. Board of Education,

349 U.S. 294, 300-391, to effectuate their decrees im

plementing the requirements of Green and Alexander

v. County Board of Education, 396 U.S. 19. Cf. Swann

v. Board of Education, supra. While the district

courts may sometimes determine the various motives 12

that played a part in a decision, a requirement that

they weigh the relative influence of each motive to

determine which predominated will not only trap the

federal courts “ in a quagmire of litigation” as they

seek to delve into the inner workings of the minds of

legislators or other public officials, but will also sanc

tion an easy method of evading the mandate of Brown

(App. B 42a; App. D 77a). See Burleson v. County

Board of Election Commissioners of Jefferson County,

308 F. Supp. 352, 357 (E.D. Ark.), affirmed, 432 F.

2d 1356 (C .A .8).

12 The possible variety of mixed motives is well illustrated

by such cases as Bueha'iian v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (maintenance

of public peace and property values); Hunter v. Erickson, 393

U.S. 385, 392 (need to move slowly in a delicate area of race

relations); Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States, 379 U.S.

241, 260 (fear of economic loss).

11

Indeed, the court below has adopted a method of

analysis of secessions from desegregating school sys

tems which is at variance with the decision of the

Eighth Circuit in the Burleson case, supra. In that

case, the district court had enjoined the secession of

the Hardin area (predominantly white) from the

Dollarway School District in Arkansas (55 percent

white and 45 percent black) because it would inter

fere with implementation o f the approved desegre

gation plan for Dollarway. The Eighth Circuit af

firmed per curiam based on the opinion of the district

court.13

The standard adopted by the court below also de

parts from the test applied by both the Second and * 12

13 Several cases pending in other courts o f appeals also pre

sent quite similar issues. In United States v. Jefferson County

Board of Education (No. 30,387, C.A. 5, docketed August 21,

1970), the issue is whether the city of Pleasant Grove, Ala

bama, can separate itself from the Jefferson County school sys

tem where the separation would adversely affect implementa

tion o f a previously approved desegregation plan for Jefferson

County. In Aytch and United States v. Mitchell, et al. {C.A.

No. PB 70-C-127, E.D. Ark., decided January 15, 1971), the

district court enjoined the holding of an election to divide the

Watson Chapel School District. The defendants filed a notice

of appeal on February 19, 1971. Likewise, in United States v.

State o f Texas, 321 F. Supp. 1043 (E.D. Tex. 1970),

appeal pending (No. 71-1061, C.A. 5, docketed January

12, 1971), the district court found racial discrimination in

the transfer of white residential areas from a predominantly

black to a predominantly white school system. In Lee and

United States, et al. v. Calhoun County Board of Education,

et al.. (No. 30,154, C.A. 5, docketed July 1970), the district

court treated the Calhoun County school system and the newly

formed Oxford City school system as one for purposes of rul

ing on the sufficiency of a desegregation plan for Calhoun

County (including Oxford).

12

the Fifth Circuits in eases involving racially discrim

inatory state action in other areas. In those cases

the courts properly held that where action by a state

agency has a racially discriminatory effect the action

can be justified only by a “ compelling state interest.”

Kennedy Park Homes Association, Inc. and United

States v. City of Lackawanna, 436 F. 2d. 108 (C.A. 2),

certiorari denied April 5, 1971, Ho. 1319, this Term;

Jackson v. Godwin, 400 F. 2d 529 (C.A. 5) ; Hawkins v.

Town of Shaw, Ho. 29,013, C.A. 5, decided January 28,

1971); Wright v. The City of Brighton, Alabama, Ho.

29,262, C.A. 5, decided March 16,1971.

Here both courts below agreed that at least one

purpose for the realignment of the school districts was

racial and the undeniable effect would be to create a

“ more white” school or schools from which the vast

majority of black students in the Halifax County sys

tem would be effectively excluded. In these circum

stances, the State’s showing of additional, non-racial

purposes fell far short of the requisite compelling

justification for such a result, and the judgment o f the

district court enjoining the realignment should have

been affirmed.

CONCLUSION

For- the foregoing reasons, the petition for a writ

o f certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted.

E rwin 1ST. Griswold,

Solicitor General.

Jerris Leonard,

Assistant Attorney General.

L awrence G. W allace,

Deputy Solicitor General.

A. R aymond R andolph, Jr.,

Assistant to the Solicitor General.

B rian K . L andsberg,

Thomas M. K eeling,

A pril 1971

Attorneys.

A P P E N D IX A

U nited States Court of A ppeals for the F ourth

Circuit

No. 14929

U nited States of A merica, and P attie B lack Cot

ton, E dward M. F rancis, P ublic School Teachers

of H alifax County, et al., appellees

versus

Scotland N eck City B oard of E ducation, a B ody

Corporate, appellant

No. 14930

U nited States of A merica, and P attie B lack Cot

ton, E dward M. F rancis, P ublic School Teachers

of H alifax County, and Others, appellees

versus

R obert M organ, A ttorney General of N orth Caro

lina, the State B oard of E ducation of N orth

N orth Carolina, and Dr. A. Craig P hillips,

N orth Carolina State Superintendent of P ublic

I nstruction, appellants

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of North Carolina, at Wilson

A lgernon L. B utler, District Judge, and John D.

L arkins, Jr., District Judge

(la)

422- 400— 71----------2

2a

Argued September 16, 1970

Before B oreman, B ryan and Craven, Circuit Judges

Reargued December 7, 1970—Decided March 23, 1971

Before H aynsworth, Chief Judge, Sobeloff, B ore-

m an , B ryan, W inter, Craven and B utzner, Circuit

Judges sitting en banc, on resubmission

William, T. Joyner and G. Kitchin Josey (Joyner &

Howison and Robert Morgan, Attorney General of

North Carolina, on brief) for Appellants; and Brian

K. Landsberg, Attorney, Department o f Justice { Jor

ris Leonard, Assistant Attorney General, David L.

Norman, Deputy Assistant Attorney General, and

Francis H. Kennedy, Jr., Attorney, Department of

Justice, and Warren H. Coolidge, United States At

torney, on brief) for Appellee United States of

America; and James R. Walker, Jr., (Samuel S.

Mitchell on brief) for Appellees Pattie Black Cotton,

et al.

Craven, Circuit Judge:

The Scotland Neck City Board of Education and

the State of North Carolina have appealed from an

order of the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of North Carolina entered May 23,

1970, declaring Chapter 31 of the 1969 Session Laws

of North Carolina unconstitutional and permanently

enjoining any further implementation of the statute.1

W e reverse. 1

1 This is one of three cases now before the Court involving

the “ carving out” of part o f a larger school district. The others

are Alvin Turner v. Littleton-Lake Gaston School District, —

F. 2d — (No. 14,990) and Wright v. Council o f City o f Em

poria, — F. 2d — (No. 14,552).

3a

Chapter 31 o f the 1969 Session Laws of North Caro

lina,2 enacted by the North Carolina General Assembly

on March 3, 1969, provided for a new school district

bounded by the city limits of Scotland Neck upon the

2 Chapter 31 is entitled and reads as follows:

“AN ACT to improve and provide public schools of a higher

standard for the residents of Scotland Neck in Halifax

County, to establish the Scotland Neck City Administrative

Unit, to provide for the administration o f the public schools

in said administrative unit, to levy a special tax for the

public schools o f said administrative unit, all of which shall

be subject to the approval o f the voters in a referendum or

special election

Section 1. There is hereby classified and established a pub

lic school administrative unit to be known and designated as

the Scotland Neck City Administrative Unit which shall consist

of the territory or area lying and being within the boundaries

or corporate limits of the Town of Scotland Neck in Halifax

County, and the boundaries o f said Scotland Neck City A d

ministrative Unit shall be coterminous with the present cor

porate limits or boundaries of the Town of Scotland Neck. The

governing board of said Scotland Neck City Administrative

Unit shall be known and designated as the Scotland Neck

City Board of Education, and said Scotland Neck City Board

of Education (hereinafter referred to as: Board) shall have

and exercise all o f the powers, duties, privileges and authority

granted and applicable to city administrative units and city

boards o f education as set forth in Chapter 115 of the General

Statutes, as amended.

“Section 2. The Board shall consist of five members ap

pointed by the governing authority o f the Town of Scotland

Neck, and said five members shall hold office until the next regular

municipal election of the Town of Scotland Neck to be held

in May, 1971. At the regular election for Mayor and Com

missioners of the Town of Scotland Neck to be held in May,

1971, there shall be elected five members o f the Board, and

three persons so elected who receive the highest number o f votes

shall hold office for four years and the two persons elected

who receive the next highest number o f votes shall hold office

4a

approval of a majority of the voters of Scotland Neck

in a referendum. The new school district was approved

by the voters of Scotland Neck on April 8, 1969, by

a vote of 813 to 332 out of a total of 1,305 registered

for two years, and thereafter all members o f the Board so

elected, as successors, shall hold office for four years. All mem

bers of the Board shall hold their offices until their successors

(sic) are elected and qualified. All members of the Board shall

be eligible to hold public office as required by the Consti

tution and laws of the State.

“Section 3. All members of the Board shall be elected by

the qualified voters of the Town of Scotland Neck and said

election shall be held and conducted by the governing author

ity of the Town of Scotland Neck and by its election officials

and pursuant to the same laws, rules and regulations as are

applicable to the election of the municipal officials of the Town

of Scotland Neck, and the results shall be certified in the same

manner. The election of members of the Board shall be held

at the same time and place as applicable to the election of the

Mayor and Board o f Commissioners o f the Town of Scotland

Neck and in accordance with the expiration of terms o f office

of members of the Board. The members of the Board so elected

shall be inducted into office on the first Monday following the

date of election, and the expense of the election of the mem

bers of the Board shall be paid by the Board.

“Section 4. At the first meeting of the Board appointed

as above set forth and of a new Board elected as herein

provided, the Board shall organize by electing one of its

members as chairman for a period of one year, or until his

successor is elected and qualified. The chairman shall pre

side at the meetings of the Board, and in the event of his

absence or sickness, the Board may appoint one of its members

as temporary chairman. The Scotland Neck City Superin

tendent of Schools shall be ex officio secretary to his Board

and shall keep the minutes of the Board but shall have no

vote. I f there exists a vacancy in the office of Superintendent,

then the Board may appoint one of its members to serve tem

porarily as secretary to the Board. All vacancies in the mem

bership o f the Board by death, resignation, removal, change

5a

voters. Prior to this date, Scotland Neck was part

of the Halifax County school district. In July 1969,

the United States Justice Department filed the com

plaint in this action against the Halifax County Board

of residence or otherwise shall be filled by appointment by the

governing authority of the Town of Scotland Neck o f a per

son to serve for the unexpired term and until the next regular

election for members o f the Board when a successor shall be

elected.

“Section- 5. All public school property, both real and per

sonal, and all buildings, facilities, and equipment used for

public school purposes, located within the corporate limits of

Scotland Neck and within the boundaries set forth in Section

1 of this Act, and all records, books, moneys budgeted for said

facilities, accounts, papers, documents and property of any

description shall become the property of Scotland Neck City

Administrative Unit or the Board; all real estate belonging to

the public schools located within the above-described bound

aries is hereby granted, made over to, and automatically by

force of this Act conveyed to the Board from the County

public school authorities. The Board of Education o f Halifax

County is authorized and directed to execute any and all deeds,

bills of sale, assignments or other documents that may be

necessary to completely vest title to all such property to the

Board.

“Section 6. Subject to the approval o f the voters residing

within the boundaries set forth in Section 1 o f this Act, or

within the corporate limits of the Town of Scotland Neck, as

hereinafter provided, the governing authority o f the Town of

Scotland Neck, in addition to all other taxes, is authorized

and directed to levy annually a supplemental tax not to exceed

Fifty Cents (50c) on each One Hundred ($100.00) Dollars of

the assessed value of the real and personal property taxable

in said Town of Scotland Neck. The amount or rate pf said

tax shall be determined by the Board and said tax shall be

collected by the Tax Collector of the Town of Scotland Neck

and paid to the Treasurer of the Board. The Board may use

the proceeds o f the tax so collected to supplement any object

or item in the school budget as fixed by law or to supplement

6a

of Education seeking the disestablishment of a dual

school system operated by the Board and seeking a

declaration of invalidity and an injunction against

the implementation of Chapter 31. Scotland Neck

any object or item in the Current Expense Fund or Capital

Outlay Fund as fixed by law.

“Section 7. Within ten days from the date of the ratification

of this Act it shall be the duty o f the governing authority of

the Town of Scotland Neck to call a referendum or special

election upon the question of whether or not said Scotland

Neck City Administrative Unit and its administrative board

shall be established and whether or not the special tax herein

provided shall be levied and collected for the purposes herein

provided. The notice of the special election shall be published

once a week for two successive weeks in some newspaper pub

lished in the Town of Scotland Neck. The notice shall contain

a brief statement of the purpose of the special election, the

area in which it shall be held, and that a vote by a majority

of those voting in favor of this Act will establish the Scotland

Neck City Administrative Unit and its Administrative Board

as herein set forth, and that an annual tax not to exceed Fifty

Cents (50c) on the assessed valuation o f real and personal

property, according to each One Hundred Dollars ($100.00)

valuation, the rate to be fixed by the Board, will be levied as a

supplemental tax in the Town of Scotland Neck, for the pur

pose o f supplementing any lawful public school budgetary item.

A new registration o f voters shall not be required and in all

respects the laws and regulations under which the municipal

elections of the Town of Scotland Neck are held shall apply

to said special election. The governing authority o f the Town

of Scotland Neck shall have the authority to enact reasonable

rules and regulations for the necessary election books, records

and other documents for such special election and to fix the

necessary details of said special election.

“ Section 8. In said referendum or special election a ballot

in form substantially as follows shall be used: VOTE FOR

ONE:

“ ( ) FOR creating and establishing Scotland Neck City

Administrative Unit with administrative Board to operate pub-

7a

City Board of Education was added as a defendant

in August 1969, and the Attorney General of North

Carolina was added as a defendant in November 1969.

On August 25, 1969, the District Court issued a tem

porary injunction restraining the implementation of

Chapter 31, and thereafter on May 23, 1970, made

the injunction permanent. The District Court rea

soned that Chapter 31 was unconstitutional because

it would create a refuge for white students and would

interfere with the desegregation of the Halifax

County school system.

lie schools of said Unit and for supplemental tax not to exceed

Fifty Cents (50c) on the assessed valuation of real and per

sonal property according to each One Hundred Dollars

($100.00) valuation for objects o f school budget.

“ ( ) AGAINST creating and establishing Scotland Neck

City Administrative Unit with administrative Board to oper

ate public schools of said Unit and against supplemental tax

not to exceed Fifty Cents (50c) on the assessed valuation of

real and personal property according to each One Hundred

Dollars ($100.00) valuation for objects o f school budget.

“ I f a majority of the qualified voters voting at such refer

endum or special election vote in favor of establishing Scotland

Neck City Administrative Unit, for creation of administrative

Board to operate public schools o f said Unit and for special

supplemental tax as herein set forth, then this Act shall be

come effective and operative as to all its provisions upon the

date said special election results are canvassed and the result

judicially determined, otherwise to be null and void. The ex

pense o f said referendum or special election shall be paid by

the governing authority of the Town of Scotland Neck but if

said Unit and Board are established, then said Town of Scot

land Neck shall be reimbursed by the Board for said expense

as soon as . possible.

“ Section 9. All laws and clauses of laws in conflict with

this Act are hereby repealed.

“ Section 10. This Act shall be in full force and effect accord

ing to its provisions from and after its ratification.”

It is clear that Chapter 31 is not unconsitutional

on its face. But a facially constitutional statute may

in the context of a given fact situation be applied

unfairly or for a discriminatory purpose in violation

of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. Yick W o v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356

(1886). W e cannot .judge the validity of the statute

in vacuo but must examine it in relation to the prob

lem it was meant to solve. Poindexter v. Louisiana

Financial Assistance Commission, 275 F. Supp. 833

(E.D. La. 1967).

I

THE HISTORY OF SCHOOL DESEGREGATION' IN HALIFAX

COUNTY AND THE ATTEMPTS TO SECURE A SEPARATE

SCHOOL DISTRICT FOR THE CITY OF SCOTLAND NECK

For many years until 1936, the City o f Scotland

Heck was a wholly separate school district operating

independently of the Halifax County school system

into which it was then merged. Both the elementary

and the high school buildings presently in use in Scot

land Heck were constructed prior to 1936 and were

financed by city funds.

Halifax County operated a completely segregated

dual school system from 1936 to 1965. In 1965, Hali

fax County adopted a freedom-of-choiee plan. Little

integration resulted during the next three years.

Shortly after the Supreme Court decision in Green

v. County School Board of New Kent County, 391

IT.S. 430, in May of 1968, the Halifax County Board

of Education requested the Horth Carolina Depart

ment of Public Instruction to survey their schools

and to make recommendations regarding desegre

gation of the school system.

9a

In July 1968, the Justice Department sent a “ notice

letter” to the Halifax County Board notifying them

that they had not disestablished a dual school sys

tem and that further steps would be necessary to

comply with Green. After negotiations with the Jus

tice Department, the Halifax County Board agreed

informally to disestablish their dual school system

by the beginning of the 1969-70 school year, with a

number of interim steps to be taken in the 1968-69

school year. As part of the interim steps, the seventh

and eighth grades were transferred from the Brawley

School, an all-black school located just outside the

city limits of Scotland Heck, to the Scotland Heck

School, previously all white.

The results of the North Carolina Department of

Public Instruction survey were published in Decem

ber of 1968. It recommended an interim plan and a

long range plan. The interim plan proposed the crea

tion of a unitary school system through a combination

of geographic attendance zones and pairing of previ

ously all-white schools with previously all-black

schools. Scotland Heck School was to be paired with

Brawley School, grades 1-4 and 8-9 to attend Braw

ley and grades 5-6 and 10-12 to attend Scotland

Heck. The long range plan called for the building of

two new consolidated high schools, each to serve half

of the geographic area composing the Halifax County

school district. The Halifax County Board of Educa

tion declined to implement the plan proposed by the

Department of Public Instruction and the Justice

Department filed suit in July 1969.

Paralleling this history of school segregation in the

Halifax County school system is a history of attempts

on the part of the residents of Scotland Heck to ob

10a

tain a separate school district. The proponents o f a

separate school district began to formulate their plans

in 1963, five years prior to the Green decision and

two years prior to the institution of freedom-of-choice

by the Halifax County Board. They were unable to

present their plan in the form of a bill prior to the

expiration of the 1963 session o f the North Carolina

Legislature, but a bill was introduced in the 1965

session which would have created a separate school

district composed of Scotland Neck and the four sur

rounding townships, funded partially through local

supplemental property taxes. The bill did not pass and

it was the opinion of many of the Scotland Neck

residents that its defeat was the result o f opposition

of individuals living outside the city limits o f Scot

land Neck.

At the instigation of the only Halifax County

Board of Education member who was a resident of

Scotland Neck, a delegation from the Halifax County

schools attempted in 1966 to get approval for the

construction of a new high school facility in Scotland

Neck to be operated on a completely integrated basis.

The proposal was not approved by the State Division

of School Planning.

After visiting the smallest school district in the

state to determine the economic feasibility o f creating

a separate unit for the City o f Scotland Neck alone,

the proponents of a separate school district again

sponsored a bill in the Legislature. It was this bill

which was eventually passed on March 31, 1969, as

Chapter 31 of the Session Laws of 1969.

11a

I I

THE THREE PURPOSES OF CHAPTER 31

The District Court found that the proponents of a

special school district had three purposes in mind in

sponsoring Chapter 31 and the record supports these

findings. First, they wanted more local control over

their schools. Second, they wanted to increase the

expenditures for their schools through local supple

mentary property taxes. Third, they wanted to pre

vent anticipated white fleeing of the public schools.

Local control and increased taxation were thought

necessary to increase the quality o f education in their

schools. Previous efforts to upgrade Scotland Neck

Schools had been frustrated. Always it seemed the

needs o f the County came before Scotland Neck. The

only county-wide bond issue passed in Halifax County

since 1936 was passed in 1957. Two local school dis

tricts operating in Halifax County received a total

of $1,020,000 from the bond issue and the Halifax

County system received $1,980,000. None of the money

received by Halifax County was spent on schools

within the city limits o f Scotland Neck. I f Scotland

Neck had been a separate school district at the time,

it would have received $190,000 as its proportionate

share of the bond issue. The Halifax County system

also received $950,000 in 1963 as its proportionate

share o f the latest statewide bond issue. None o f this

money was spent or committed to any of the schools

within the city limits o f Scotland Neck. Halifax

County has reduced its annual capital outlay tax from

63 cents per $100 valuation in 1957 to 27.5 cents per

$100 valuation in the latest fiscal year. In order for

the referendum to pass under the terms of Chapter

31, the voters o f Scotland Neck had to approve not

12a

only the creation of a separate school district but in

addition had to authorize a local supplementary

property tax not to exceed 50 cents per $100 valua

tion per year. Despite such a political albatross the

referendum was favorable, and moreover, the sup

plementary tax was levied by the Scotland Xeek

Board at the full 50 cent rate.

I l l

W HITE FLEEING— THE QUESTIONABLE THIRD PURPOSE

But it is not the permissable first purpose or the

clearly commendable second purpose which caused the

District Court to question the constitutionality of

Chapter 31. It is rather the third purpose, a desire

on the part of the proponents o f Chapter 31 to pre

vent, or at least diminish, the flight of white students

from the public schools, that concerned the District

Court. The population of Halifax County is pre

dominantly black. The population of Scotland Neck

is approximately 50 percent black and 50 percent

white, and the District Court found that the pupil

ratio by race in the schools would have been 57.3

percent white to 42.7 percent black.

A number of decisions have mentioned the problem

of white flight following the integration of school

systems which have a heavy majority of black stu

dents. Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of the City

of Jackson, 391 U.S. 450, 459 (1968); Brunson v.

Board of Trustees of School District No. 1 of Claren

don County, — F. 2d — (4th Cir. 1970); Walker v.

County School Board of Brunswick County, 413 F.

2d 53 (4th Cir. 1969); Anthony v. Marshall County

Board of Education, 409 F. 2d 1287 (5th Cir. 1969).

All of these cases hold that the threat of white flight

will not justify the continuing operation of a dual

13a

school system. But it has never been held by any court

that a school board (or a state) may not constitu

tionally consider and adopt measures for the purpose

o f curbing or diminishing white flight from a unitary

school system. Indeed it seems obvious that such a

purpose is entirely consistent with and may help

implement the Brown principle. It is not the purpose

of preventing white flight which is the subject of

judicial concern but rather the price of achievement.

I f the effect of Chapter 31 is to continue a dual school

system in Halifax County, or establish one in Scot

land Heck, the laudable desire to stem an impending

flow of white students from the public schools will

not save it from constitutional infirmity. But if

Chapter 31 does not have that effect, the desire of its

proponents to halt white flight will not make an other

wise constitutional statute unconstitutional.

In considering the effect of Chapter 31 on school

desegregation in Halifax County and Scotland Heck,

it is important to distinguish the effect of Chapter 31

from the effect of a transfer plan adopted by the

Scotland Heck Board of Education. The effect o f the

transfer plan was to substantially increase the per

centage of white students in the Scotland Heck

schools. But the transfer plan is solely the product of

the Scotland Heck Board of Education and not

Chapter 31. Therefore the effect of the transfer plan

has no relevance to the question of the constitutional

ity of Chapter 31.3

3 Appellees argue that, the creation of the transfer plan is

evidence that the intended effect of Chapter 31 was to preserve

the previous racial makeup of the Scotland Heck schools. We

disagree.

We are concerned here with the intent of the Horth Carolina

Legislature and not the intent of the Scotland Neck Board. In

determining legislative intent of an act such as Chapter 31,

14a

The District Court held that the creation of a sep

arate Scotland Neck School district would unconstitu

tionally interfere with the implementation of a plan

to desegregate the Halifax County schools adopted by

the Halifax County Board of Education. W e hold

that the effect of the separation of the Scotland Neck

schools and students on the desegregation of the re

mainder of the Halifax Comity system is minimal and

insufficient to invalidate Chapter 31. During the 1968-

69 school year, there were 10,655 students in the Hali

fax County Schools, 8,196 (77% ) were black, 2,357

(22% ) were white, and 102 (1% ) were Indian. Of

this total, 605 children of school age, 399 white and

296 black, lived within the city limits o f Scotland

Neck. Removing the Scotland Neck students from the

Halifax County system would have left 7,900 (80% )

black students, 1,958 (19% ) white students, and 102

(1% ) Indian students. This is a shift in the ratio of

black to white students of only 3 percent, hardly a

substantial change. Whether the Scotland Neck stu

dents remain within the Halifax County system or

attend separate schools of their own, the Halifax

County schools will have a substantial majority of

black students. Nor would there be a per pupil de-

it is appropriate to consider the reason that the proponents of

the act desired its passage if it can be inferred that those rea

sons were made known to the Legislature. There is evidence

in the record to show that the three purposes that the District

Court found were intended by the proponents of Chapter 31

were presented to the Legislature. However, there is nothing

in the record to suggest that the Legislature had any idea that

the Scotland Neck Board would adopt a transfer plan after the

enactment of Chapter 31 which would have the effect o f in

creasing the percentage of white students.

We will discuss the transfer plan later in a separate part of

the opinion.

15a

crease in the proceeds from the countywide property

taxes available in the remaining Halifax County sys

tem. The county tax is levied on all property in the

county and distributed among the various school

districts in the county on a per pupil basis. In addi

tion, the Superintendent o f Schools for the Halifax

County system testified that there would be no de

crease in teacher-pupil ratio in the remaining Halifax

County system and in fact that in a few special areas,

such as speech therapy, the teacher-pupil ratio may

actually increase.

Nor can we agree with the District Court that

Chapter 31 creates a refuge for the white students of

the Halifax County system. Although there are more

white students than black students in Scotland Neck,

the white majority is not large, 57.3 percent white and

42.6 percent black. Since all students in the same

grade would attend the same school, the system would

be integrated throughout. There is no indication that

the geographic boundaries were drawn to include

white students and exclude black students as there

has been in other cases where the courts have ordered

integration across school district boundaries. Haney

v. County Board of Education of Sevier County, 410

F. 2d 920 (8th Cir. 1969). The city limits provide a

natural geographic boundary. There is nothing in the

record to suggest that the greater percentage of white

students in Scotland Neck is a product o f residential

segregation resulting in part from state action. See

Brewer v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, 397

F. 2d 37 (4th Cir. 1968).

From the history surrounding the enactment of

Chapter 31 and from the effect o f Chapter 31 on

school desegregation in Halifax County, we conclude

that the purpose of Chapter 31 was not to invidiously

16a

discriminate against black students in Halifax County

and that Chapter 31 does not violate the equal protec

tion clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Appellees urge in their brief that conceptually the

way to analyze this case is to “ view the results of

severance as if it were part of a desegregation plan

for the original system.” W e do not agree. The sever-

e ance was not part of a desegregation plan proposed

by the school board but was instead an action by the

Legislature redefining the boundaries of local govern

mental units. I f the effect of this act was the con

tinuance of a dual school system in Halifax County

or the establishment of a dual system in Scotland

Feck it would not withstand challenge under the equal

protection clause, but we have concluded that it does

\not have that effect.

But assuming for the sake of argument that the

appellees’ method of analysis is correct, we conclude

that the severance of Scotland Feck students would

still withstand constitutional challenge. Although it is

not entirely clear from their brief, appellants’

apparent contention is that the variance in the ratio

of black to white students in Scotland Feck from the

ratio in the Halifax County system as a whole is so

substantial that if Scotland Feck was proposed as a

geographic zone in a desegregation plan, the plan

would have to be disapproved. The question of

“ whether, as a constitutional matter, any particular

racial balance must be achieved in the schools” has

yet to be decided by the courts. Northcross v. Board

of Education of Memphis, —TJ.S.—, 90, S. Ct. 891,

893 (1970) (Burger, C. J., concurring). In its first

discussion of remedies for school segregation, Brown

v. Board of Education o f Topeka, 349 TJ.S. 294

(1955) (Brown I I ) , the Supreme Court spoke in

terms of “ practical flexibility” and “ reconciling pub-

17a

lie and private needs.” 349 U.S. at 300. In Green v.

County School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S.

430 (1968), the court made it clear that the school

board has the burden of explaining its preference

for a method of desegregation which is less effective

in disestablishing a dual school system than another

more promising method. Even if we assume that a

more even racial balance throughout the schools of

Halifax County would be more effective in creating

a unitary school system, we conclude that the devia

tion is adequately explained by the inability of peo

ple of Scotland Heck to be able to increase the level

of funding o f the schools attended by their children

when the geographic area served by those schools

extended beyond the city limits of Scotland Heck.

Our conclusion that Chapter 31 is not unconsti

tutional leaves for consideration the transfer plan

adopted by the Scotland Heck School Board. The

transfer plan adopted by the Board provided for

the transfer of students from the remaining Halifax

County system into the Scotland Heck system and

from the Scotland Heck system into the Halifax

County system. Transfers into the Scotland Heck

system were to pay $100 for the first child in a fam

ily, $25 for the next two children in a family, and

no fee for the rest of the children in a family. As

a result o f this transfer plan, 350 white students and

10 black students applied for transfer into the Scot

land Heck system, and 44 black students applied for

transfer out of the system. The net result o f these

transfers would have been to have 74 percent white

students and 26 percent black students in the Scot

land Heck system. W e conclude that these transfers

would have tended toward establishment o f a resegre

gated system and that the transfer plan violates the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amend-

422-400—'71'-------S

18a

ment.4 See Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of the

City of Jackson, 391 U.S. 450 (1968).

W e reverse the judgment of the District Court

holding Chapter 31 unconstitutional, and remand to

the District Court with instructions to dissolve its

injunction. The District Court will retain jurisdic

tion to consider plans of integration proposed by

Halifax County Board of Education and by Scotland

Heck Board of Education.

4 Perhaps it should be noted that in the school board’s

amended answer filed on September 3, 1969, it withdrew

the original transfer plan and represented to the District

Court that it intended to allow only such transfers as “may

be in conformity to the law and/or Court order or orders

applicable to Defendant, and in conformity to a plan of

limitation of transfers to be prepared by Defendant and

submitted to this Court.”

A P P E N D IX B

United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

No. 14552

P ecola A nnette W right, et al., appellees

v.

Council of the City of E mporia and the M embers

Thereof, and School B oard of the City of E mporia

and the M embers Thereof, appellants

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia, at Richmond

R obert R. M erhige, Jr., District Judge

Argued October 8,1970—Decided March 23,1971

Before H aynsworth, Chief Judge, B oreman, B ryan,

W inter, and Craven, Circuit Judges sitting en

banc*

John F. Kay, Jr., and D. Dortch Warriner ( W ar-

riner, Outten, Slagle & Barrett; and Mays, Valentine,

Davenport & Moore on brief) for Appellants, and S.

W . Tucker (Henry L. Marsh, I I I , and Hill, Tucker

& Marsh; and Jack Greenberg, James M. Nabrit, I I I ,

and Norman Chachkin on brief) for Appellees.

CRAVEN, Circuit Judge: In this case and two

others now under submission en banc we must deter

mine the extent of the power o f state government to

* Judge Sobeloff did not participate. Judge Butzner disqualified

himself because he participated as a district judge in an eai'lier

stage o f this case.

(19a)

20a

redesign the geographic boundaries o f school dis

tricts.1 Ordinarily, it would seem to be plenary but

in school districts with a history of racial segregation

enforced through state action, close scrutiny is required

to assure there has not been gerrymandering for the

purpose of perpetuating invidious discrimination.

Each of these cases involve a county school district

in which there is a substantial majority of black students

out of which was carved a new school district comprised

of a city or a city plus an area surrounding the city. In

each case, the resident students of the new city unit are

approximately 50 percent black and 50 percent white.

In each case, the district court enjoined the establish

ment of the new school district. In this case, we reverse.

I

I f legislation creating a new school district produces

a shift in the racial balance which is great enough to

support an inference that the purpose of the legisla

tion is to perpetuate segregation, and the district

judge draws the inference, the enactment falls under

the Fourteenth Amendment and the establishment of

such a new school district must be enjoined. See

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 399 (I960). Cf.

Haney v. County Board of Education of Sevier

County, 410 E. 2d 920 (8th Cir. 1969); Burleson v.

County Board of Election Commissioners o f Jefferson

County, 308 E. Supp. 352 (E.D. Ark.) a ff’d — F. 2d — ,

No. 20228 (8th Oir. Nov. 18, 1970). But where the

shift is merely a modification of the racial ratio rather

than effective resegregation the problem becomes more

difficult.

1 The other two cases are United States v. Scotland. Neck City

Board of Education, — F. 2d —, Nos. 14929 and 14930 (4th

Cir. —, 1971) and Turner v. Littleton-Lake Gaston School Dis

trict, — F. 2d —, No. 14990 (4th Cir. —, 1971).

21a

The creation of new school districts may be desir

able and/or necessary to promote the legitimate state

interest of providing quality education for the state’s

children. The refusal to allow the creation of any new

school districts where there is any change in the racial

makeup of the school districts could seriously impair

the state’s ability to achieve this goal. At the same

time, the history of school integration is replete with

numerous examples of actions by state officials to im

pede the mandate of Brown v. Board of Education,

349 U.S. 294 (1955) (Brown I I ) . There is serious

danger that the creation of new school districts may

prove to be yet another method to obstruct the transi

tion from racially separated school systems to school

systems in which no child is denied the right to attend

a school on the basis of race. Determining into which

of these two categories a particular case fits requires a

careful analysis of the facts of each case to discern the

dominant purpose of boundary realignment. I f the cre

ation of a new school district is designed to further

the aim of providing quality education and is attended

secondarily by a modification of the racial balance,

short of resegregation, the federal courts should not

interfere. If, however, the primary purpose for creat

ing a new school district is to retain as much of sepa

ration o f the races as possible, the state has violated

its affirmative constitutional duty to end state sup

ported school segregation. The test is much easier to

state than it is to apply.

I I

Emporia became a city of the so-called second class

on July 31, 1967, pursuant to a statutory procedure

established at least as early as 1892. See 3 Va. Code

§ 15.1-978 to -998 (1950); Acts of the Assembly 1891-

92, eh. 595. Prior to that time it was an incorporated

22a

town and as such was part of Greensville County. At

the time city status was attained Greensville County

was operating public schools under a freedom of

choice plan approved by the district court, and Green

v. County School Board of Neiv Kent County, 391

U.S. 430 (1968), invalidating freedom of choice unless

it “ worked,” could not have been anticipated by Em

poria, and indeed, was not envisioned by this court.

Bowman v. County School Board of Charles City

County, 382 E. 2d 326 (4th Cir. 1967). The record does

not suggest that Emporia chose to become a city in

order to prevent or diminish integration. Instead, the

motivation appears to have been an unfair allocation

of tax revenues by county officials.

One of the duties imposed on Emporia by the V ir

ginia statutes as a city of the second class was to

establish a school board to supervise the public educa

tion of the city’s children. Under the Virginia statutes,

Emporia had the option o f operating its own school

system or to work out one of a number o f alternatives

under which its children would continue to attend

school jointly with the county children. Emporia con

sidered operating a separate school system but decided

it would not be practical to do so immediately at the

time o f its independence. There was an effort to work

out some form of joint operation with the Greensville

County schools in which decision making power would

be shared. The county refused. Emporia finally signed

a contract with the county on April 10, 1968, under

which the city school children would attend schools

operated by the Greensville County School Board in

exchange for a percentage of the school system’s oper

ating cost. Emporia agreed to this form of operation

only when given an ultimatum by the county in March

1968 that it would stop educating the city children

mid-term unless some agreement was reached.

23a

At the same time that the county was engaged in its

controversy with Emporia about the means of educat

ing the city children, the county was also engaged in

a controversy over the elimination of racial segrega

tion in the county schools. Until sometime in 1968,

Greensville County operated under a freedom of

choice plan. At that time the plaintiffs in this action

successfully urged upon the district court that the

freedom of choice plan did not operate to disestablish

the previously existing dual school system and thus

was inadequate under Green v. County School Board

of Neiv Kent County, supra. After considering various

alternatives, the district court, in an order dated June

25, 1969, paired all the schools in Greensville County.

Also in June 1969, Emporia was notified for the

first time by counsel that in all probability its contract

with the county for the education of the city children

was void under state law. The city then filed an action

in the state courts to have the contract declared void

and notified the county that it was ending its con

tractual relationship forthwith. Parents of city school

children were notified that their children would at

tend a city school system. On August 1, 1969, the

plaintiffs filed a supplemental complaint seeking an

injunction against the City Council and the City

School Board to prevent the establishment of a sepa

rate school district. A preliminary injunction against

the operation of a separate system was issued on Au

gust 8, 1969. The temporary injunction was made

permanent on March 3 ,1969.2

The Emporia city unit would not be a white island

in an otherwise heavily black county. In fact, even in

2 The decision of the court below is reported as Wright v.

County School Board of Greensville County, 309 F. Supp. 671

(E.D. Ya. 1970).

24a

Emporia there will be a majority of black students

in the public schools, 52 percent black to 48 percent

white. Under the plan presented by Emporia to the

district court, all of the students living within, the city

boundaries would attend a single high school and a

single grade school. At the high school there would

be a slight white majority, 48 percent black and 52

percent white, while in the grade school there would

be a slight black majority, 54 percent black and 46

percent white. The city limits of Emporia provide a

natural geographic boundary for a school district.

The student population of the Greensville County

School District without the separation of the city unit

is 66 percent black and 34 percent white. The stu

dents remaining in the geographic jurisdiction of the

county unit after the separation would be 72 percent

black and 28 percent white. Thus, the separation of

the Emporia students would create a shift of the

racial balance in the remaining county unit of 6 per

cent. Regardless of whether the city students attend

a separate school system, there will be a substantial

majority of black students in the county system.

Rot only does the effect of the separation not de

monstrate that the primary purpose of the separation

was to perpetuate segregation, but there is strong evi

dence to the contrary. Indeed, the district court found

that Emporia officials had other purposes in mind.

Emporia hired Dr. Neil H. Tracey, a professor of

education at the University o f North Carolina, to

evaluate the plan adopted by the district court for

Greensville County and compare it with Emporia’s

proposal for its own school system. Dr. Tracey said

his studies were made with the understanding that it

was not the intent of the city to resegregate. He testi

fied that the plan adopted for Greensville County

would require additional expenditures for transpor

25a

tation and that an examination of the proposed budget

for the Greensville County Schools indicated that not

only would the additional expenditures not be forth

coming but that the budget increase over the previous

year would not even keep up with increased costs due

to inflation, Emporia on the other hand proposed in

creased revenues to increase the quality of education

for its students and in Dr. Tracey’s opinion the pro

posed Emporia system would be educationally su

perior to the Greensville system. Emporia proposed

lower student teacher ratios, increased per pupil ex

penditures, health services, adult education, and the

addition of a kindergarten program.

In sum, Emporia’s position, referred to by the dis

trict court as “ uncontradicted,” was that effective

integration of the schools in the whole county would

require increased expenditures in order to preserve

education quality, that the county officials were un

willing to provide the necessary funds, and that

therefore the city would accept the burden of educat

ing the city children. In this context, it is important

to note the unusual nature of the organization of city

and county governments in Virginia. Cities and coun

ties are completely independent, both politically and

geographically. See City of Richmond v. County

Board, 199 Va. 679, 684 (1958); Murray v. Roanoke,

192 Va. 321, 324 (1951). When Emporia was a town,

it was politically part of the county and the people of

Emporia were able to elect representatives to the

county board of supervisors. When Emporia became a

city, it was completely separated from the county and

no longer has any representation on the county board.

In order for Emporia to achieve an increase in school

expenditures for city schools it would have to obtain

the approval of the Greensville County Board of

26a

Supervisors whose constituents do not include city

residents.

Determining what is desirable or necessary in terms

of funding for quality education is the responsibility

of state and school district officers and is not for our

determination. The question that the federal courts

must decide is, rather, what is the primary purpose

of the proposed action of the state officials. See Devel

opments in the Lcnv—Equal Protection, 82 Harv. L.

Rev. 1065 (1969). Is the primary purpose a benign

one or is the claimed benign purpose merely a cover-

up for racial discrimination? The district court must,

of course, consider evidence about the need for and

efficacy of the proposed action to determine the good

faith of the state officials ’ claim of benign purpose. In

this case, the court did so and found explicitly that

“ [t]he city clearly contemplates a superior quality

education program. It is anticipated that the cost will

be such as to require higher tax payments by city resi

dents.” 309 F. Supp. at 674. Notably, there was no

finding of discriminatory purpose, and instead the

court noted its satisfaction that the city would, i f per

mitted, operate its own system on a unitary basis.

W e think the district court’s injunction against the

operation of a separate school district for the City of

Emporia was improvidently entered and unnecessarily

sacrifices legitimate and benign educational improve

ment. In his commendable concern to prevent resegre

gation—under whatever guise—the district judge

momentarily overlooked, we think, his broad discretion

in approving equitable remedies and the practical flex

ibility recommended by Brown I I in reconciling

public and private needs. W e reverse the judgment of

the district court and remand with instructions to dis

solve the injunction.

Because of the possibility that Emporia might insti

tute a plan for transferring students into the city sys

tem from the county system resulting in resegregation,3

or that the hiring of teachers to serve the Emporia

school system might result in segregated faculties, the

district court is directed to retain jurisdiction.

Reversed and remanded.

SOBELOFF, Senior Circuit Judge, with whom

W IN TER, Circuit Judge, joins, dissenting and con

curring specially: In respect to Nos. 1.4929 and 14930,

United States v. Scotland Neck City Board of Educa

tion, — F. 2d — (4th Cir. 1971), and No. 14990,

Turner v. Littleton-Lake Gaston School District, —

F. 2d — (4th Cir. 1971), the two cases in which I par

ticipated, I dissent from the court’s reversal in Scot

land Neck and concur in its affirmance in Littleton-

Lake Gaston. I would affirm the District Court in each

of those cases. I join in Judge W inter’s opinion, and

since he has treated the facts analytically and in

detail, I find it unnecessary to repeat them except as

required in the course of discussion. Not having partic

ipated in No. 14552, Wright v. Council of City of

Emporia, — F. 2d — (4th Cir. 1971), I do not vote

on that appeal, although the views set forth below

necessarily reflect on that decision as well, since the

principles enunciated by the majority in that case are

held to govern the legal issue common to all three of

these school cases.

3 A notice of August 31, 1969, invited applications from the

county. Subsequently, the city assured the district court- it

would not entertain such applications without court permission.

28a

I

The history of the evasive tactics pursued by white

communities to avoid the mandate o f Brown v. Board

of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955), is well documented.