Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Support of Plaintiffs' Motion for Partial Summary Judgement

Public Court Documents

June 21, 1991

26 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Matthews v. Kizer Hardbacks. Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Support of Plaintiffs' Motion for Partial Summary Judgement, 1991. 07ddcd6c-5c40-f011-b4cb-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0b510bc9-9d6d-42dc-aad3-aab9f6233a86/memorandum-of-points-and-authorities-in-support-of-plaintiffs-motion-for-partial-summary-judgement. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

4

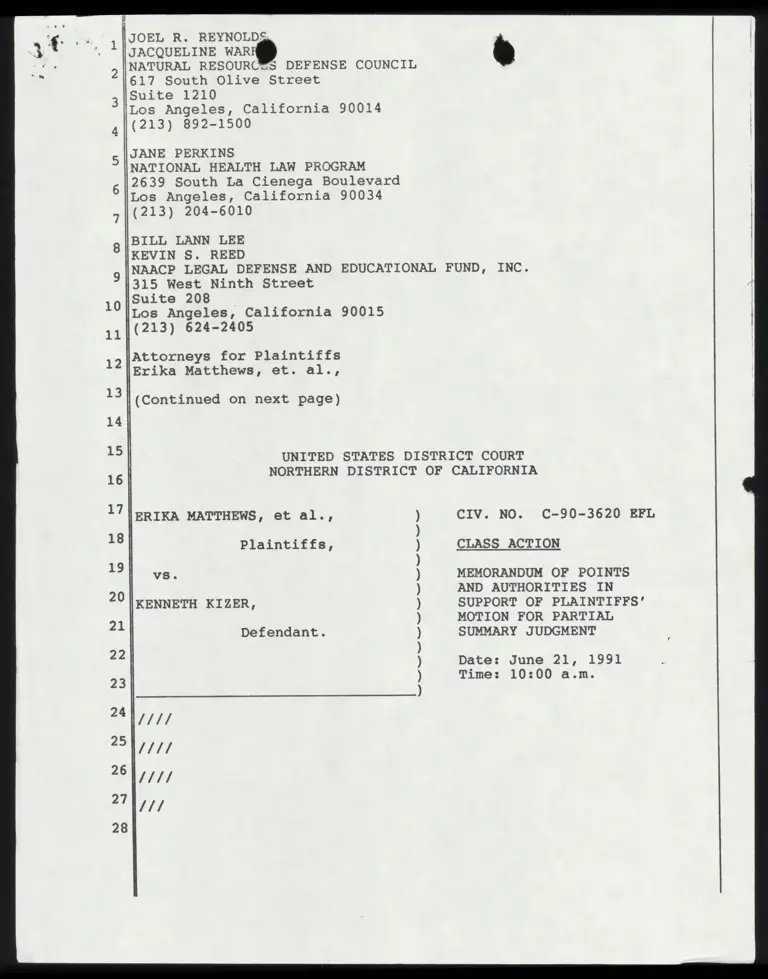

JOEL R. REYNOLDS

JACQUELINE wif) i

NATURAL RESOURCTS DEFENSE COUNCIL

617 South Olive Street

Suite 1210

Los Angeles, California 90014

(213) 892-1500

JANE PERKINS

NATIONAL HEALTH LAW PROGRAM

2639 South La Cienega Boulevard

Los Angeles, California 90034

(213) 204-6010

BILL LANN LEE

KEVIN S. REED

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

315 West Ninth Street

Suite 208

Los Angeles, California 90015

(213) 624-2405

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

Erika Matthews, et. al.,

(Continued on next page)

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

ERIKA MATTHEWS, et al., CIV. NO. C-90-3620 EFL

Plaintiffs, CLASS ACTION

vs. MEMORANDUM OF POINTS

AND AUTHORITIES IN

SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS’

MOTION FOR PARTIAL

KENNETH KIZER,

N

e

t

?

Se

t”

Se

s”

S

t

?

N

a

”

N

n

”

“u

nt

an

t

V

t

?

w

t

mi

?

“w

it

“

w

t

?

Defendant. SUMMARY JUDGMENT

Date: June 21, 1991

Time: 10:00 a.m.

11/4

[1/7

/11/

[17

MARK D. ROSENBAUM

ACLU FOUNDATI OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

633 South Shatco Place

Los Angeles, California 90005

(213) 487-1720

SUSAN SPELLETICH

KIM CARD

LEGAL AID SOCIETY OF ALAMEDA COUNTY

1440 Broadway

Suite 700

Oakland, California 94612

(415) 451-9261

EDWARD M. CHEN

ACLU FOUNDATION OF NORTHERN CALIFORNIA

1663 Mission Street

Suite 460

San Francisco, California 94103

(415) 621-2493

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

Erika Matthews, et al.,

/11/

[177

/t1#

/141/

{111

{1/44

[117

17/4

11/4

[1/1]

/171/

/11/

[11/7

[177

[177

TABLE OF CONTENTS

» » Page

INTRODUCTION. «ott tins snnininnisin svn snvommenas euvinmasneess wns 1

STATEMENT ‘OF THE CASE.» caisv sv svvviainie ssleinsvvne vine elely du din nv 2

A. California's Medicaid Program ....ssceeesvsne 2

B. The Problem of Childhood Lead Poisoning....... 3

C. Lead Blood Level Assessments Under Medi-Cal .. 5

ARGUMENT * 0.00 0 0 0 0 Sie a iials ores wv ainivniein vinlode eine ula nine vinenie vane sn B

I. THE PLAIN MEANING OF THE MEDICAID ACT,

AUTHORITATIVELY CONSTRUED, REQUIRES BLOOD

LEAD TESTING OF ALL ELIGIBLE CHILDREN

ACES ONE TO PIVE:t1s cress trtssonssstrsasssnscens 7

II. THE PLAIN MEANING OF THE MEDICAID ACT IS

CONFIRMED BY THE LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF

THE EPSDT STATUTE, AS WELL AS BY

LONGSTANDING REGULATORY AND MEDICAL GUIDANCE ..... 9

III. THE DEPARTMENT'S INTERPRETATION IS

ARBITRARY... +: Cone rining . cow rss cine FI 13

CONCLUSION "vont sav es eo oo 0 ® ® eo e 0 0° 9 eo eo 0 ® eo oo . ® 20

— i

i A TABLE OF AUTHORITIES{f])

2 Cases Page

3 American Tobacco Co, v. Patterson, 456 U.S. 63 (1982) . . . 9

4 Beisler v. C.F.R,, 814 F.2d 1304 (9th Cir. 1987) & +. . » +. 1B

5 Beltran v. Myers, 701 F.2d 91 (9th Cir.)

cert. denied sub nom. Rank v. Beltram, 462 U.S.

6 1134 (1983) ‘ 2

“ California Department of Health Services v.

United States Department of Health and Human

8 Servics, 853. F.2d 634 (Sth Cir. 1888) vv « ¢« sie « v + 5.0 9

9 Citizens Action League v. Kizer, 887 F.2d 1003

(9th Cir, 1989) LJ LJ LJ LJ LJ LJ [J LJ LJ LJ * LJ] . * LJ LJ LJ ° LJ * 7. 19

10 Clark v., Kizer, 758 F.Supp. 572 (E.D. Cal. 1990) . « . « + 14

11 Co Petro. Mktg. Group, Inc., 680 F.2d 566

12 (Sth CAX. 1982) ot. oe a ov a a Taine sas vs iiniia vw o +» 1B

13 Delancey v, E.P.A., 898 F.2d 687 (Oth Cir. 1987) . viv + « « 14

14 [In_xe Oxborrow, 913 F.2d 751 (Sth Cir. 1990) . « . « + «+ + 18

15 Markair, Inc. v. C.A.B., 744 F.2d 1383

(Oth Cire 1984) iv ovis ov 0 0 0 viois sin sin wie isnie 19

16 Mitchell v. Johnston, 701 F.2d 336 (5th Cir. 1983) . . . . 3

17 Oregon O0.B.0. Oregon Health Services v. Bowen, 854 F.2d

18 346 (Oth Cir, 11988) ys ov ov sv 0 oe ni sie oie sa 2 ase so » +» 14

19 Pacificorp v. Bonneville Power Admin., 856 F.2d 94

(Oth CiX. 1988) io vi +. so is ie o 0. v.00 e's ais u's vv 0% «14

20 | pottgieser v. Kizer, 906 F.2d 1319 (9th Cir. 1990) . . 7, 14

2) inane v. Botevan, 462:0.8. 00134 (1983) + vv + cu viii) 2

22 Schweiker v. Gray Panthers, 453 U.S. 34 (1981) . . .. . . 2

23 Stanton v. Bond, 504 F.2d 1246 (7th- Cir. 1974) ., «. . +. « +» 3

24 lynited States v. 594,464 Pounds of Salmon, 871 F.2d 824

25 (Sth Cix,. 1988) « «0 «a 0 o wine wie 0 oinileaVe nin o's ey |

26 Vierra v. Rubin, 915 P.2d 1372 (9th Cir, 1980) .. . «. + 14, 19

27

28

ii

& Statutes

42. U.S.C. § 1396a

42 U.S.C. § 1396a(a)

42 U.S.C. § 1396d(a)

AU, 8.0, SG A3S6ALTY + oo + SE WE Ne SY,

42 U.S.C. 8S 1396

Miscellaneous

135 Cong. Rec. § 13233 (October 12, 1989 1989)

Explanation of the Conference Committee

Affecting Medicare-Medicaid Programs Re:

Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of

1989 (H.R. 3299), reprinted in

Medicare & Medicaid Guide (CCH),

Extra Edition No. 603 (Dec. 15, 1989) + «¢ 4 ¢ « ov.» +

HEW, A Guide to Screening-EPSDT and Medicaid (1974).

HEW, Guide to Administration, Diagnosis

and Treatment for the EPSDT Program under

Madicaid (HEW 1977) « + 5 5 + os 5 o'»

HEW, Information Memorandum, "New Technology Available

in the Screening and Detection of Lead Poisoning and

EPSDT" (1M-77-32 (MSA)) June 9, 1977), reprinted in

Medicare & Medicaid Guide (CCH) ¥ 28,505. . . . ‘

HEW, Medical Assistance Manual, § 5-70-00 (June 28,

1972) LJ * . * LJ LJ LJ L] LJ LJ LJ LJ LJ LJ LJ LJ LJ LJ * LJ LJ *

Health Care Financing Administration

State Medicaid Manual (April 1988)

Hearing on HR 5700 Before the House

Committee on Ways and Means, 90th

Cong., 1 Sess., Pt. 1, at 189 (1967)

Sutherland, 1A Statutory Construction

§ 31.06 (Sands 4th ed. 1985) . . . . . .

Welfare of Children H.R. Doc. #54,

90th Cong., 1St Sess. (1967) + os « +. + «. sls

iii

11,

e123

12

12

.10

.10

.10

27

28

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The Medicaid Act requires the Department of Health

Services ("DHS") to provide "lead blood level assessment[s]"

to eligible children as “appropriate for age and risk

factors," as a mandatory "laboratory test." 42° U.8.C...§

1396d(r). Controlling federal authority contained in the

State Medicaid Manual, California Dep't of Health Services v.

United States Dep’t of Health and Human Services, 853 F.2d 634

(9th Cir. 1988), refines the requirement: All Medicaid

eligible children ages 1-5 must be screened using a lead blood

test. DHS does not comply with this law, instead requesting

providers merely to ask unspecified questions of children.

The plain meaning of the statute and implementing

regulations is dispositive. (Citizens Action League v. Kizer,

887 F.2d "1003 (9th Cir... 1989). Requiring blood level

assessment of all young children is consistent with 17 years

of development of regulatory recommendations. Legislative

history, moreover, is clear that Congress intended in 1989 to

codify and expand regulatory authorities to make the Act more

effective in early detection of childhood illnesses.

DHS’'s refusal to implement testing of all young

children is arbitrary. Mere questioning will not reveal a

high blood lead content; only a test will do that. DHS’s

approach cannot be squared with regulatory authority, opinions

from the leading experts in the field, or statements by the

DHS’s own representatives. Sutherland, 1A Statutory

Construction § 31.06 (Sands 4th ed. 1985) (and cases therein).

INTRODUCTION

This case concerns the failure of Tne California Department

of Health Services ("DHS" or "Department") to provide lead blood

level assessments to Medi-Cal eligible children as required by the

federal Medicaid Act ("Act"). This Act was amended in 1989 to

require for all eligible children "lead blood level assessment

appropriate for age and risk factors," as a mandatory "laboratory

test." 42 U.S.C. § 1396d(r). Federal regulatory authority -- which

the Department admits is controlling -- further refines this testing

directive as to young children in conformity with the statute and

current scientific knowledge to require participating providers to

"[s]creen all Medicaid eligible children ages 1-5 for lead

poisoning," and to conduct this screen by using a lead blood test.

The Department, however, refuses to require periodic lead

blood tests for eligible young children; rather, it takes the

position that health care providers need only conduct an oral

examination concerning a Medi-Cal eligible child, making no

differentiation as to its special legal duty for children ages 1-5.

This construction treats the specifically articulated federal

requirements as if they had never been drafted. Furthermore, it is

at war with undisputed medical facts: young children are especially

vulnerable to lead, and lead poisoning, because it is asymptomatic

in its early, still reversible stages, cannot be detected without a

blood test.

Because the Department contends that lead blood assessments

are not mandatory, these tests are virtually never performed in

California. During the last six months of 1990, for example, the

Department tested only .0002% of the eligible children below age five

living in the,State, As a result, tens of thousands of young

children are needlessly placed at risk ofTiead poisoning each year,

victims of a preventable disease that state and federal officials

have called "the number one environmental health hazard facing

children."! And the tragic effects of the disease are indisputable:

decreased intelligence, impaired nervous system and cognitive

development, kidney disease, anemia, sterility, convulsions, coma,

and even death.

Under the circumstances, and in the absence of a dispute

as to any material fact underlying the legal claims that give rise

to this motion, summary judgment is appropriate in this case.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. California’s Medicaid Program

In 1965, Congress enacted Title XIX of the Social Security

Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1396 et seg., establishing a cooperative federal-

state medical assistance program for the poor. See Beltran v. Myers,

701 F.2d 91, 92 (9th Cir.), cert. denied sub nom. Rank v. Beltran,

462 U.S. 1134 (1983). Commonly known as "Medicaid," each state's

standards for providing assistance must be consistent with the

"objectives of the Act," 42 U.S.C. § 1396a(a)(17), and must meet the

"requirements imposed by both the Act itself and by the Secretary of

Health and Human Services." Schweiker v. Gray Panthers, 453 U.S. 34,

36-37 (1981). Seas 42 U.S.C. § 1398a.

Federal law requires states participating in the Medicaid

: Declaration ("Dec.") of Dr. John F. Rosen at 9¢ 4

(Exhibit A, hereto); CHDP Provider Information Notice #91-6 from

Director Kenneth Kizer to CHDP Providers Re: Lead Poisoning in

Children « (March 12, 1991) (hereinafter "CHDP Provider

Information Notice #91-6") (Exhibit C, hereto). See also Dr.

Herbert L. Needleman Dec. at § 3 (Exhibit B, hereto).

program to provide recipients with certain "essential" services, H.R.

Rep. No. 213, ¥3th Cong., 1st Sess. 9-109 70 (1965), including a

disease prevention program for children under age 21 called the Early

and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment ("EPSDT") program.

42 U.S.C. 8§§ 139%6a(a)(43), d(a)(4)(B), and d(r). See Mitchell wv.

Johnston, 701 F.2d 336, 340 (5th Cir. 1983); Stanton v. Bond, 504

F.2d 1246 (7th Cir. 1974) (discussing mandatory nature of EPSDT

benefit and specifically mentioning need for early detection and

treatment of lead poisoning). Laboratory tests, including lead blood

level assessments, are a required EPSDT benefit. 42 U.S.C. §

1396d(r)(1) (iv) and, therefore, should be a component of California's

Medicaid program.

The State of California has elected to participate in the

Medicaid program and, to that end, has established the California

Medical Assistance Program, known as "Medi-Cal" and administered by

DHS. Cal. Welf. & Inst. Code §§ 14005.1, 14090.1, 14051. DHS calls

its EPSDT screening program the Child Health and Disability

Prevention ("CHDP") Program. Calf. Welf. & Inst. Code § 10721; Cal.

Health & Safety Code §§ 320 et seq.

B. The Problem of Childhood Lead Poisoning

DHS concedes that "lead poisoning is the most significant

environmental health problem facing California children today[.]"?

The problem exists because lead is pervasive in our society =-- in

paint, gasoline, drinking-water pipes, printing inks, pigments used

in toys, fertilizers, food cans, and soil. Rosen Dec. at § 5

(Exhibit A, hereto). Poor and minority «children are

2

hereto).

CHDP Provider Information Notice #91-6 (Exhibit C,

disproportionataly affected by lead because they are more likely to

live or visit older homes and homes with peeling paint, live with an

adult who is exposed to lead, or live and play near industries likely

to release lead. 1Id.; Needleman Dec. at § 3 (Exhibit B, hereto).

While early lead toxicity is potentially reversible, the

adverse affects of untreated lead exposure are wide-ranging.

Needleman Dec. at 99 4-7; Rosen Dec. at 49 6-7. Severe lead exposure

can cause coma, convulsions, and death. Id. Lower levels adversely

affect the central nervous system, kidneys, reproductive system, and

blood system. Id. Even very low blood lead levels are associated

with decreased intelligence, stature, hearing acuity, and slowed

neurobehavioral development. Id. Young children are especially

vulnerable to these effects because their neurologic systems are

still developing and because they tend to engage in hand-to-mouth

behavior that leads to ingestion of lead. Needleman Dec. at § 3;

Rosen Dec. at ¥ 5.

To complicate matters, children, especially young children,

generally exhibit no overt symptoms during the early stages of lead

poisoning. Id.; CHDP Provider Information Notice #91-6 (Exhibit C,

hereto). Thus, a lead blood level assessment is the only accurate

and reliable method of screening for lead exposure. Needleman Dec.

at § 7; Rosen Dec. at § 8. See also Deposition ("Depo.") of Dr.

Maridee Gregory at 32, 43, 46-47; Range Depo. at 36-37. As even

Defendant Kizer has recognized, "[t]lhe biggest problem is the

awareness, getting doctors to test kids. . . . You have to test for

it."?

3 S.Roan, "High Number of Lead Poison Cases Found," L.A.

Times, Aug. 30, 1990, A3, col. 1 (Exhibit D, hereto).

C. Lead Blood Level Assessments Under Medi-Cal

oll oe of the State’s needy, eligible children are

obtaining lead blood level assessments through the Medi-Cal program.

During fiscal year 1989-90, for example, only 283 lead blood tests

were provided to Medi-Cal eligible children under age five.‘ Only 117

tests were provided to this group of children during the last six

months of 1990.° By comparison, there were over 570,000 Medi-Cal

eligible children below age five living in California during this

time.® |

Moreover, fully two-thirds of the Medi-Cal reimbursed lead

level assessments tests were performed in a single county among

Asian-American children and were given by a single provider,’ called

an "aggressive" tester by the Department. CHDP Provider Information

Notice #91-6 (Exhibit C, hereto). Although an estimated 67% of

African-American inner city children, nationwide, suffer from lead

toxicity, Rosen Dec. at ¥ 4, only two lead blood tests were provided

during fiscal year 1989-90 to African-American children under age

‘ DHS, Statewide: Fiscal Year 1989-90 Ethnicity by Age

Group by Funding Source by Lead Test (Feb. 15, 1991) (Exhibit

E, hereto).

5 DHS, Statewide: July 1990 thru January 1991 Ethnicity

by Age Group by Funding Source by Lead Test (Feb. 15, 1991)

(Exhibit F, hereto).

5 DHS Medical Care Statistics Section, California's

Medical Assistance Program Annual Statistical Report Calendar

Year 1989, at Table 20 (Exhibit G, hereto).

7 DHS, Fiscal Year 1989-90 Provider Number by Age Group by

Funding Source by Lead Test: County of Residence = Santa Clara

(Feb. 15, 1991) (Exhibit H, hereto).

five living in Los Angeles County’ -- the county with the highest

concentration OY African-Americans in the Yate.’

Defendant Kizer admits that "insufficient consideration"

is presently being given to lead poisoning during EPSDT evaluations

and that "essentially no routine childhood screening for lead ha[s]

been conducted in California since the late 1970’s." CHDP Program

Information Notice #91-6 (Exhibit C, hereto). Persons in the

Department responsible for the EPSDT/lead assessment program concede

they have no idea of the numbers of children who obtain lead blood

level assessments, nor have they made any inquiry to discern the

numbers of tested or affected children. Range Depo. at 28-33, 38

(Exhibit J, hereto); Gregory Depo. at 23-24, 28 (Exhibit K, hereto).

$ DHS, Fiscal Year 1989-90 Ethnicity by Age Group By

Funding Source by Lead Test: County of Residence = Los Angeles

(Feb. 15, 1991) (Exhibit I, hereto).

9

DHS Medical Care Statistics Section, California Medical

Assistance Program Annual Statistical Report Calendar Year 1989,

at Table 29 (Exhibit G, hereto).

ARGUMENT

I. THE ®. MEANING OF THE oe» ACT, AUTHORITATIVELY

CONSTRUED, REQUIRES BLOOD LEAD TESTING OF ALL ELIGIBLE

CHILDREN AGES ONE TO FIVE.

Construction of a congressional statute or its implementing

regulations starts with the plain meaning of the law. Pottgieser v.

Kizer, 906 F.2d 1319, 1322 (9th Cir. 1990); Citizens Action League

v. Kizer, 887 F.2d 1003, 1006 (9th Cir. 1989). This plain meaning

controls unless Congress has clearly expressed a contrary legislative

intention. United States v. 594,464 Pounds of Salmon, 871 F.2d 824,

825-26 (9th Cir. 1989).

Lead blood level assessment of Medicaid recipient children

is required by the plain terms of the Medicaid Act as recently

amended and authoritatively construed. The EPSDT Program, which was

created by 1967 amendments to Title XIX of the Social Security Act,

"is the most important publicly-financed preventive child health

program ever enacted by Congress, and the benefits that it offers are

unparalleled." Health Care Coverage for Children: Hearing Before the

Senate Committee on Finance, 101st Cong., lst Sess. 24 (statement of

Kay A. Johnson, Director, Children’s Defense Fund Health Division)

(June 20, 1989) (Exhibit L, hereto). EPSDT requires mandatory,

medical screening for poor children to diagnose their "physical or

mental defects" as early as possible. 42 U.S.C. § 1396d(a)(4)(B)

("EPSDT statute").

In 1989, Congress noted that the increasing numbers of poor

children mean that the "EPSDT benefit will become even more important

to the health status of children in this country." Report of the

House Budget Committee on H.R. 3299 (Sept. 20, 1989), reprinted in

Medicare & Medicaid Guide (CCH), Extra Edition No. 596 (Oct. 5, 1989)

at 398 (Exhibit M, hereto). Thus, it amended the EPSDT statute to

add a new definTtional subsection requiring, in part, that screening

"shall at a minimum include . . . laboratory tests (including lead

blood level assessment appropriate for age and risk factors)." 42

U.S.C. § 1396d(r)(l)(iv). That Congress specifically mentioned lead

blood laboratory testing in the Medicaid Act as the only statutorily

required laboratory test illustrates its importance: because, for the

most part, Congress has chosen instead simply to list broad

categories of services (e.g., hospital services, physician services,

laboratory tests) rather than enumerate specific procedures by name.

Compare 42 U.S.C. § 1396d(r)(1)(iv) with 42 U.S.C. §§ 1396 et. seq.

The Health Care Financing Administration ("HCFA") of the

United States Department of Health and Human Services ("HHS"), which

administers the EPSDT program, issued changes to the State Medicaid

Manual to implement the 1989 amendments. Those changes further

defined the timing and nature of the statutory screening requirement

in light of current scientific knowledge:

Appropriate Laboratory Tests. Identify as statewide

screening requirements, the minimum laboratory tests or

analyses to be performed by medical providers for

particular age or population groups.... As appropriate,

conduct the following laboratory tests:

1. Lead Toxicity Screening. - Where age and risk factors

indicate it is medically appropriate to perform blood level

assessments, a blood level assessment is mandatory. Screen

all Medicaid eligible children ages 1-5 for lead poisoning.

Lead poisoning is defined as an elevated venous blood lead

level (i.e., greater than or equal to 25 micrograms per

deciliter (ug/dl) with an elevated erythrocyte

protoporphyrin (EP) level (greater than or equal to 35

ug/dl of whole blood). In general, use the EP test as the

primary screening test. Perform venous blood measurements

on children with elevated EP levels.

HCFA, State Medicaid Manual, § 5123.2(D) (incorporating revisions

contained in HCFA transmittals of April and July 1990) (emphases

added) (Exhibit N, hereto).

DHS itself admits that it is bound by the Manual'’s terms,

see Range Depo. at 34-35, 46 (Exhibit J, hereto); Gregory Depo. at

62-64 (Exhibit K, hereto). DHS also admits that the specific

portions of the Manual quoted above dictate how the Department must

screen children for lead. Range Depo. at 46 ("Q.: But, I take it,

with respect to them [the specific provisions quoted above] as

guidelines, you would take them as controlling the way you carried

out your duties; is that right? A: Yes."). The State Medicaid

Manual, moreover, has been recognized by the courts as the

authoritative regulatory guidance on implementation of the Medicaid

Act's requirements and, as such, binding on participating states.

See, e.q., California Department of Health Services Vv. United States

Department of Health and Human Services, 853 F.2d 634, 640 (9th Cir.

1988) ("Even though State sets forth a reasonable argument . . . the

‘interpretation of an agency charged with the administration of a

statute is entitled to substantial deference’ [citations omitted].").

These authorities unequivocally establish the Department’s

duty to provide lead blood level assessments, and the Department’s

failure to do so cannot be reconciled with its legal obligations

under the Medicaid program.

11. THE PLAIN MEANING OF THE MEDICAID ACT IS CONFIRMED BY THE

LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF THE EPSDT STATUTE, AS WELL AS BY

LONGSTANDING REGULATORY AND MEDICAL GUIDANCE.

The federal courts have long recognized that consideration

of legislative history is inappropriate where, as here, the statutory

language is plain and unambiguous. See, e.qg., American Tobacco Co.

v. Patterson, 456 U.S. 63 (1982). In this case, however, the

legislative history reinforces and confirms the statute’s terms.

Indeed, the 1929 amendment to the EPSDT statute on mandatory lead

level assessments codified and expanded almost two decades of

regulatory development in the area of lead testing of young children.

Congress enacted the underlying EPSDT statute with a broad

remedial intent to "discover, as early as possible, the ills that

handicap our children." President Lyndon B. Johnson, Welfare of

Children, H.R. Doc. No. 54, 90th Cong., 1st Sess. 7 (1967).

During hearings on the legislation, HEW Secretary John Gardner

explained that "under our proposed amendments, all children in low-

income or medically indigent families would be assured periodic

screening. . . , particularly in the preschool years." Hearings on

H.R. 5700 Before the House Committee on Ways and Means, 90th Cong.,

) Sess., Pt. 1,.8t 189 (1967).

Although the EPSDT statute did not specify blood lead level

assessments, such assessments have consistently been recommended by

federal EPSDT program regulators for 17 years before the 1989

amendment, with the recommendations becoming generally more rigorous

over time. In 1972, the Department of Health, Education and Welfare

("HEW"), predecessor agency to HHS, included a discussion of the

EPSDT program as part of the Medical Assistance Manual, the

predecessor to the HCFA State Medicaid Manual. HEW, Medical

Assistance Manual § 5-70-00 (June 28, 1972) (Exhibit O, hereto).

Under the heading "Lead Poisoning Screening," the Program Regulation

Guide contained a specific recommendation, but not a directive, that

1 president Johnson originally proposed the EPSDT program

as part of a comprehensive package of programs for children,

pointing out that over 3.5 million medically-needy children

under five did not receive help under public medical care

programs and that over a million more children needed treatment

under the crippled children’s program.

10

all young chilgaen should be periodically gareened and older children

as medically indicated for a "determination of blood lead levels" in

order "to identify which children may have had undue exposure to

lead-based paint and other sources of lead poisoning." Id. at § 5-

70-20. See also id. at 5-70-20E.4.E. The recommendation for testing

of all young children was carried forward in subsequent editions

until the recommendation was changed to a directive after the 1989

amendments to the EPSDT statute.'

Other regulatory or medical guidance was initially narrower

in scope, but subsequently broadened. The American Academy of

Pediatrics and HEW published A Guide to Screening-EPSDT Medicaid (HEW

1974), which recommended repeated lead screening of all children ages

one to three who lived or frequented older homes or were exposed to

industrial pollution. Id. at 188 (Exhibit Q, hereto). The Guide

recommended two blood tests as the "methods for use in screening for

undue lead absorption." Id. at 189.

In 1977, however, an HEW Information Memorandum amended the

Guide to abandon a selective testing approach, recommending screening

2

of all children ages one to three.!? After noting that excessive lead

11

See, e.q. HCFA, State Medicaid Manual § 5122.5.d (April

1988) ("All EPSDT eligible children, ages 1-5 should be screened

for lead toxicity, using the erythrocyte protoporphyrin (EP)

test as the primary screening test.") (Exhibit P, hereto). HCFA

also issued regulations to implement the EPSDT program in 1984

which included within the screen "appropriate laboratory tests,"

42 C.F.R. § 441.56{(P)(1)(v). This regulation has been

interpreted by at least one court to require lead poisoning

screening. New York City Coalition to End Lead Poisoning Vv.

Koch, 524 N.Y. 8.24 314, 318-19 (S.Ct. 1987).

12. HEW, Information Memorandum, "New Technology Available

in the Screening and Detection of Lead Poisoning and EPSDT" (1M-

77-32(MSA)) (June 9, 1977), reprinted in Medicare & Medicaid

Guide (CCH) ¥ 28,505 (Exhibit R, hereto).

11

exposure "can god does have serious and yr - irreversible effects

on the development of the central nervous system" of younger

children, the Information Memorandum declared that most poisoned

children "do not have overt symptoms of the disease [which] . . . can

only be detected by screening the child" and that, "the majority of

the children served by the EPSDT Program are in the high risk group"

of those who live in or near poorly maintained old housing. Id. The

Information Memorandum, therefore, recommended that all young

children would be tested at least once using the then-newly developed

and inexpensive erythrocyte protoporphyrin ("EP") blood test.

The same year the Information Memorandum was issued, the

Academy of Pediatrics and HEW prepared A Guide to Administration,

Diagnosis and Treatment for the EPSDT Program under Medicaid (HEW

1977) (Exhibit S, hereto) as a revision of the 1974 Guide. Because

"[c]lassical symptomatic lead poisoning is generally not seen," the

Guide to Administration recommended that all children through five

years of age as a routine matter should receive an EP blood test for

lead poisoning. Thus, when Congress considered the 1989 amendments,

both the federal EPSDT regulators and the Academy of Pediatrics

recommended blood lead level testing of all young children.

The legislative history of the 1989 amendments clearly

indicates congressional intent generally to codify and expand the

mandatory elements of the EPSDT program. Recognizing that “the

benefit package has never been described in detail in the statute,”

Congress explained that "many [states] still do not provide to

children participating in EPSDT all care and services allowable under

federal law." 135 Cong. Rec. S 13233 (October 12, 1989) (Exhibit T,

hereto). The House Committee Report, therefore, required that

12

"screening serygces must, at a minimum, include . . . laboratory

tests (including blood lead level assessment appropriate for age and

risk factors)." Report of the House Budget Committee on H.R. 3299

(Sept. 20, 1989), reprinted in Medicare & Medicaid Guide (CCH), Extra

Edition No. 596 (Oct. 5, 1989) at 398 (Exhibit M, hereto). The

Conference Committee, following the House bill, noted with approval

that the House bill had "codified the current regulations on minimum

components of EPSDT screening. . . with minor changes," but

"provide[d] that screening must include blood testing when

appropriate." Explanation of the Conference Committee Affecting

Medicare-Medicaid Programs Re: Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of

1989 (H.R. 3299), reprinted in Medicare & Medicaid Guide (CCH), Extra

Edition No. 603 (Dec. 15, 1989) at 453 (emphasis added) (Exhibit U,

hereto).

This legislative history is fully consistent with the plain

meaning of the law. From the inception of the EPSDT program, changes

in requirements for health care providers have all been in the

direction of expanding recommendations for testing so as to prevent

or treat lead poisoning at the earliest stage feasible. As

longstanding medical guidance makes clear, this objective can only

be met in the area of lead poisoning in young children by using a

blood level assessment. Any construction of statutory requirements

to mean less than blood level testing of all Medi-Cal eligible young

children would be contrary to two decades of regulatory development,

capped by the 1989 Congressional amendments and authoritative

construction of the statute contained in the State Medicaid Manual.

III. THE DEPARTMENT'S INTERPRETATION IS ARBITRARY.

DHS contends that, under the Medicaid Act, a doctor need

13

i

—

_

.

S

A

A

A

A

A

-3

only conduct a verbal screen of the child and that lead blood

assessments, however valuable, are simply a matter of discretion.

Range Depo. at 47, 54-55 (Exhibit J, hereto) ("Providers are

requested or directed to assess all children for risk of lead burden”

but have not been given the specific questions to ask).

The Department’s position is invalid because it is "not

reasonably related to the purposes of the statute [and directives]

it seeks to implement." Vierra v. Rubin, 915 F.2d 1372, 1376-80 (9th

Cir. 1980). See Pacificorp v. Bonneville Power Admin., 856 F.2d 94,

97 (9th Cir. 1988); cf. Oregon 0O.B.O. Oregon Health Services v.

Bowen, 854 F.2d 346, 350 (9th Cir. 1988)." Particularly in the area

of health and human services, courts in this circuit have often

invalidated departmental constructions of statutes and regulations

that collide with legislative purpose. See, e.q., Vierra v. Rubin,

915 F.2d at 1376 & n.2 (and cases cited therein); Pottgieser v.

Kizer, 906 F.2d 1319, 1323 (9th Cir. 1990); Delaney v. E.P.A., 898

F.2d 687 (9th Cir. 1987); Clark v, Rizer, 758 F.Supp. 572 (E.D. Cal.

1990).

> Here, deference to DHS’s position is doubly unwarranted

because neither the EPSDT statute nor the State Medicaid Manual

delegates authority to the states to define or otherwise

determine for themselves what constitutes a screen for Medicaid

eligible children ages 1-5 for lead poisoning. See, e.q.,

Kenaitze Indian Tribe v. State of Alaska, 860 F.2d 312, 316 (9th

Cir. 1988)("Most fundamentally, unlike a federal agency, the

state is delegated no authority [by the statute] .... Deference

is not appropriate”). While state Medicaid agencies do have

flexibility in deciding which groups of the poor they will

cover, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1396a(a)(10), what optional services they

will offer, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1396a(a)(10) and 1396(d), and, to a

certain extent, which income and resource eligibility standards

they will use, 42 U.S.C. §§ 139%6a(a)(10)(c) and (a)(17), no room

is left for the possibility of fifty possibly widely divergent

approaches to medical screens for the national problem of lead

toxicity in young children.

14

In this case, the Department’s cgatention that a minimally

adequate lead SCreening program need not =nclude lead blood level

assessments is arbitrary on its face. First, this position is

dangerously at odds with the nation’s principal experts in the

subject area of lead toxicology who uniformly agree that screening

for lead poisoning in young children requires, at minimum, periodic

determinations of blood lead levels, impossible without measurement

of blood lead content.'* As explained by Dr. John F. Rosen, Chairman

of the Centers for Disease Control’s Advisory Committee on Childhood

Lead Poisoning Prevention:

7. Most [lead] poisoned children ... have no

symptoms. As a result, the vast majority of lead

poisoning cases go undiagnosed and untreated.

Because of this and the fact that early lead

toxicity is reversible, monitoring of blood lead

levels of young children through periodic

screening is absolutely essential. Once

detected, lead poisoning and related health

effects can often be treated and, in many cases,

measures can be undertaken to detect and

eliminate the source of exposure. Screening

programs have had a tremendous impact on reducing

the occurrence of symptomatic lead poisoning in

the United States.

8. Measuring blood lead content is the most

accurate and reliable method of screening for

recent lead exposure. Blood lead level testing

is essential to adequate lead screening programs,

in part because an oral assessment of risk

factors is totally unreliable to identify

toxicity in young children. Only direct

measurements of lead in blood can establish the

presence or absence of recent excessive exposure.

For all children, I am not aware of any protocol

for lead screening satisfying accepted

professional standards that fails to include

periodic blood lead level tests. In my opinion,

periodic screening by blood lead measurement

"* When it amended the EPSDT statute in 1989, Congress

noted the importance of expert opinions when determining

appropriate preventive child care. 42 U.S.C. §1396d(r)(1)(A)(1)

requires consultation with "recognized" medical organizations).

15

shoulg be conducted at least onge per year for

any ld under the age of six b use virtually

all young children -- especially those who are

poor -- are at risk for lead poisoning. For

children considered to be at high risk for lead

exposure due to positive testing results or

environmental or other factors, blood lead

testing should be conducted, at the very least,

every three to six months. To do otherwise would

be unconscionable in light of what we now know

of the effects of lead at relatively low exposure

levels.

Rosen Dec. at 991 7-8 (emphasis added) (Exhibit A, hereto). See also

Needleman Dec. at § 7 (Exhibit B, hereto) ("A lead screening program

that failed to require such periodic lead blood testing would, in my

opinion, be both unsound and inadequate").

Second, the Chief of the California Children Services

Branch of the Department, Dr. Maridee A. Gregory, admitted that "the

routine type of screening that is done" in California --the mere use

of physician interviews -- "might not find anything because of the -

- type of screening that’s being done," Gregory Depo. at 43 (Exhibit

K, hereto), and that "blood lead is the definitive test." Id. at

46."

Ruth Range, Chief of the State’s Regional Operations

Section of CHDP, conceded similarly that the purpose of the EPSDT

program as it relates to exposure to lead for Medi-Cal eligible

children is "[t]o identify any child with an elevated blood lead

level, and treat and remove that lead from the environment." Range

15 She stated that in separate DHS studies of lead

poisoning in young children in California communities of

Oakland, Wilmington, and Compton, unrelated to the EPSDT

program, blood lead level screens were automatically

administered to all children, explaining that "[w]henever you're

assessing or truly trying to evaluate whether a child has a lead

problem, you have to do blood lead." Id. at 46 (emphasis

added).

16

Depo. at 31 (Exhibit J, hereto). Range defined "elevated blood

level" as anytiiing more than 25 microgram® of lead per deciliter of

blood, id. at 31-32, a circumstance that is discernible only with

laboratory testing. She further testified that between 25-50

micrograms per deciliter, a child suffering from lead poisoning

"would not be necessarily symptomatic," and below 25 would

"[p]robably not [be symptomatic], or they would be very subtle,”

defining this latter condition as "[p]robably symptomatology that

would not be identified as resulting from lead." Id. at 36. See

also id. at 37 (testifying as true for children below the age of

five).

Third, the Department’s position that it need only ask

unspecified questions of all eligible children and their families is

unacceptable because it ignores entire portions of the State Medicaid

Manual’s screening requirements for young children. Under the

Department’s protocol, children ages one through five are "screened"

for lead poisoning in just the same way as children ages six and

above; DHS thereby interprets the law to prescribe no different

procedures for separate age classifications of eligible children.

Pursuant to DHS’s construction, therefore, the screening sentence

might as well be deleted or amended simply to read, "[s]creen all

Medicaid eligible children." The State Medicaid Manual does neither.

If the directive to screen young children means anything, it must

mean that DHS is required to make distinctions between the screening

for lead poisoning for children ages 1-5 and that conducted for older

children. Regulatory language must, of course, be construed so as

to render no provision surplusage or redundant, and to give effect,

if possible, to every word used. See Sutherland, 1A Statutory

17

Construction §,31.06 (Sands 4th ed. 1985) ("It is obvious, that

inasmuch as a regulation is a written instlument the general rules

of interpretation apply."). See, e.9., In re Oxborrow, 913 F.2d 751,

753-54 (9th Cir. 1990); Beisler v. C.F.R., 814 F.2d 1304, 1307 (9th

Cir. 1987); In re Co Petro. Mktg. Group, Inc., 680 F.2d 566, 569-70

(9th Cir. 1982).

Third, DHS’ interpretation of the State Medicaid Manual

makes no sense because it requires the term "lead poisoning" to mean

one thing in one part of the provision and something quite different

thereafter. Specifically, the Wanual states: "Screen all Medicaid

eligible children ages 1-5 for lead poisoning. Lead poisoning is

defined as an elevated venous blood lead level ...." HCFA, State

Medicaid Manual § 5123.2(D) (Exhibit N, hereto). Application of DHS’

policy, then, finds the term "lead poisoning" to mean a verbal

examination when it is first used, but to mean a lead blood

assessment when it is used immediately thereafter. This position

simply makes no sense. Significantly, "lead poisoning," as

deliberately defined within the Manual, is a term capable -- indeed,

only capable -- of determination by means of blood level assessment.

"Lead poisoning," as thus specified within the Manual, can never be

ascertained unless a medical blood test is administered to discover

whether there actually exists "an elevated . . . blood lead level"

above a designated microgram per deciliter standard. Especially

where, as DHS concedes, lead poisoning in young children may well be

asymptomatic, no mechanism short of blood analysis for lead content

can ever truly achieve the objective of "[s]creen[ing] ... for lead

poisoning" as so fixed by the Manual’s definition. It is certainly

no accident, therefore, that the lead screening paragraph appears in

18

the section entjtled "appropriate laboratory tests.” To adopt a

different definition of "lead poisoning," as Giecessarily follows from

DHS’ definition of screening when applied to young children,

therefore, impermissibly frustrates the deliberate policy of the

Manual. See Vierra v. Rubin, 915 F.2d 1372, 1376-80 (9th Cir. 1980);

Marksir, Inc..yv. C.A.B., 744 F.2d 1383, 1385 (Sth Cir. 1984).

Finally, DHS’ view does not comport with the "minimum

Federal requirements" articulated in a letter dated April 11, 1991

from Charles Woffinden, Chief of the HHS Medicaid Operations Branch

to the California CHDP Branch. (Exhibit V, hereto). In it, the HHS

official described what he deemed compliance with the EPSDT statute

and the cited HCFA transmittals. Although not entitled to deference,

and even though apparently misinformed as to DHS’s actual practice,

the letter is nevertheless instructive regarding HHS’ candid view of

the "minimum Federal requirements" that "all Medi-Cal eligible

children ages 1-5 are to be screened for elevated blood lead levels

through the performance of an ‘FEP’ test."'S

Under these circumstances, the Department’s refusal to

18 Subsequent to this letter, counsel for the Department

apparently had a discussion with an employee of HHS, Gregory

Depo. at 58-59, which resulted in issuance of a second letter,

which appears to reverse the opinion stated in the first letter

in light of the discussion with DHS counsel. Letter from

Charles A. Woffinden, Chief HHS Medicaid Operations Branch, to

Michael Quinn, Research Manager CHDP (May 7, 1991) (Exhibit W,

hereto). Although no explanation for the change in position is

given, the letter concludes that the Department meets "minimum

Federal requirements" even though it "does not routinely perform

the FEP test for all children 1-5 years of age." Id. This

letter is clearly entitled to no deference from this Court. It

was only written for purposes of this litigation; moreover, it

lacks the candid appraisal of the Department’s lead policy that

was reflected in HHS’ earlier letter. See, e.q., Citizens

Action League v. Kizer, 887 F.2d 1003, 1007 (9th Cir. 1989)

(letter written for purposes for litigation entitled to no

deference).

19

test poor, young children for lead poisoning is entitled to no

deference. Ny as a matter of clear st®Rutory interpretation,

3 longstanding medical standards, and common sense, its self-

serving construction of its obligations under federal law must be

4

5 rejected and summary judgment granted in favor of plainciffs.V

6 CONCLUSION

. For the reasons set forth above, plaintiffs respectfully

g [request that this Court grant their Motion for Summary Judgment

9 and enter the accompanying proposed order.

Dated: May 43, 1991 Respectfully submitted,

1 Natural Resources Defense Council

12 National Health Law Program

ACLU Foundation of Southern California

13 NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund

Legal Aid Society of Alameda County

14 ACLU Foundation of Northern California

15 By: (pel R Cenoldds ap

Jéel R. Reynolds

Natural Resources Defense Council 16 S

17 By: Qin onto oni

(Jans Perkins

ational Health Law Program

3% By: 72 Jeok DD Foson bucive sor

Mark D. Rosenbaum

ACLU Foundation of Southern California

20 By: Bell ofan Aoi

Bill Lann Lee a ”

2) NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund

22 By: Ale (zl of

23 Kim Card

Legal Aid Society of Alameda County

24

25

'” See Fed. R. Civ. P. 56(d); Retail Clerks Union Local

261648, AFL-CIO v. Hub Pharmacy, Inc., 707 F.2d 1030, 1033 (9th

Cir. 1983). See also Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, 477 U.S. 31%,

2701323 (1966) (moving party may rely upon "the pleadings,

depositions, answers to interrogatories, and admissions on file,

28 ltogether with the affidavits, if any").

20