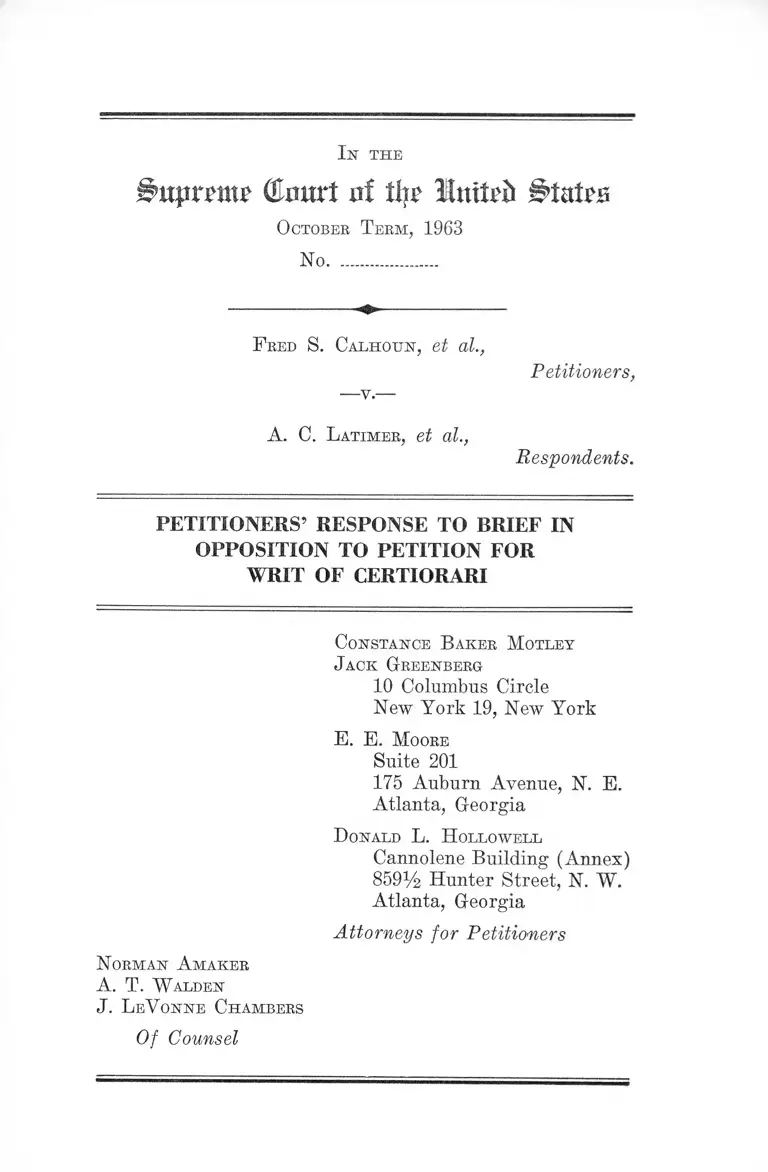

Calhoun v. Latimer Petitioners' Response to Brief in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Calhoun v. Latimer Petitioners' Response to Brief in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1963. 71382288-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0b5b23ca-0f0b-4b8b-85aa-672b4eb4c9c9/calhoun-v-latimer-petitioners-response-to-brief-in-opposition-to-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

Btxpttm? (£mnl n! % luttai States

O ctober T erm , 1963

No.....................

1st the

F red 8. Calh o u n , et al.,

Petitioners,

A . C. L atimer, et al.,

Respondents.

PETITIONERS’ RESPONSE TO BRIEF IN

OPPOSITION TO PETITION FOR

WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Constance B aker M otley

J ack G reenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

E. E. M oore

Suite 201

175 Auburn Avenue, N, E.

Atlanta, Georgia

D onald L . H ollowell

Cannolene Building (Annex)

859% Hunter Street, N. W.

Atlanta, Georgia

Attorneys for Petitioners

N orman A m a k e r

A. T. W alden

J. L eV onne Chambers

Of Counsel

I n th e

Jhtpr?ntT (to r t of the Ilnttoit Stairs

O ctobee T eem , 1963

No......................

F eed S. Calh o u n , et al,

Petitioners,

A . C. L atim ee , et al.,

Respondents.

PETITIONERS’ RESPONSE TO BRIEF IN

OPPOSITION TO PETITION FOR

WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Although the Fifth Circuit has ruled in Augustus v.

Board of Public Instruction of Escambia County, 306 F. 2d

862, that the redrawing of school zone lines on a nonracial

basis is a minimum requirement in every school desegrega

tion plan, respondents say on page 11 of their brief in op

position, “ We would still oppose the drawing of school

zones by a Court or even the school authorities” . This mini

mal requirement for desegregation has been adopted by the

Sixth Circuit, Northcross v. Board of Education of Memphis,

302 F. 2d 818, and the Fourth Circuit. Jones v. School

Board of City of Alexandria, 278 F. 2d 72, 76. The majority

opinion below does not require Atlanta to follow the Au

gustus case in this respect. It was for this reason that

Judge Rives in his dissenting opinion characterized the

majority opinion as a step backward for the Fifth Circuit.

2

The obvious reason for this minimum requirement is the

eventual elimination of initial assignments to schools based

on race with Negro children thereafter enjoying only an

opportunity to apply for transfer out of a Negro school into

a white school. Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 308

F. 2d 491 (5th Cir. 1962). However, there being no direc

tive in the majority opinion to the Atlanta school authori

ties to abolish the dual zones, which respondents now admit

exist (see pp. 11-12 of Respondents’ Brief), the Atlanta

plan is still one providing for initial racial assignments

and dual zones. Another setback for the Fifth Circuit.

Respondents read into the majority opinion below a re

quirement that beginning in September 1964 (when the

present plan will be effective as to grades 8-12, in that it

will permit students in these grades to apply for transfer

to other schools) every child in grades 8-12 will have the

right to attend the school nearest his home. Petitioners

do not so read the opinion of the majority. The majority

opinion requires only that the present pupil assignment

criteria of the plan be applied to all students entering the

high schools for the first time (eighth grade where the

feeder system takes hold) and to all students new to the

system entering a desegregated grade and to first grade

pupils when the plan eventually reaches that grade (Ap

pendix to Petition 22a and 40a). There is no ruling that

pupils in grades 9-12 are now entitled to attend the schools

nearest their homes, as claimed by respondents. A further

setback for the Fifth Circuit.

The crucial fact which cannot be gainsaid is that three

years of desegregation in Atlanta, one of the largest cities

in the south, has resulted in less than 150 Negro children

out of a total school enrollment of approximately 106,000

(57,500 white and 48,000 Negro) transferring to white

schools without any order from the District Court or the

B

Court of Appeals to speed the desegregation process. More

over, the majority opinion approves a grade-a-year pupil

assignment plan, still another setback for the Fifth Circuit,

Boson v. Rippy, 285 F. 2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960), which has

brought about this meager result and does not require any

speeding up of the plan despite this Court’s clear admoni

tion to the District Court, Watson v. City of Memphis, 373

U. S. 526, and Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 683.

Respondents say that the atmosphere in Georgia has

changed from one of massive resistance to acceptance of

this Court’s decision in the Brown ease, and for this reason

certiorari should be denied in this case. Yet, it should be

clear to all that in former massive resistance states the only

way to insure compliance with the Fourteenth Amendment

against interference by either state officials, Cooper v.

Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, or individuals, Hoxie v. School Board,

137 F. Supp. 364 (D. C. Ark. 1956), aff’d 238 F. 2d 91 (8th

Cir. 1956) is to insulate school authorities against such

interference by the orders of lower federal courts. The

school desegregation record throughout the south to date

makes plain that so far only constant pressure brings prog

ress, notwithstanding the good faith of the school authori

ties. And as the Fifth Circuit said in Borders v. Rippy,

247 F. 2d 268, 272: “ Faith by itself, however, without works,

is not enough. There must be ‘compliance at the earliest

practicable date’ ” .

4

CONCLUSION

For the additional foregoing reasons, this Petition for

a Writ of Certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

N orman A maker

Constance B aker M otley

J ack G reenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

E. E. M oore

Suite 201

175 Auburn Avenue, N. E.

Atlanta, Georgia

D onald L. H ollowell

Cannolene Building (Annex)

859V2 Hunter Street, N. W.

Atlanta, Georgia

Attorneys for Petitioners

A . T . W alden

J. L eV onne C hambers

Of Counsel

o 38

I s T H E

(tart of tl?? i>tat?s

O ctober T erm , 1963

No. - .............

F red S. Calh o u n , et al.,

— v . —

Petitioners,

A . C. L atim er , et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Co sstasce B aker M otley

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

E. E. M oore

Suite 201

175 Auburn Avenue, N. E.

Atlanta, Georgia

D onald L . H ollowell

Cannolene Building (Annex)

859% Hunter Street, N. W.

Atlanta, Georgia

Attorneys for Petitioners

N o rm a s A maker

A . T . W alden

J . L eV onnb Chambers

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Citation to Opinions Below ...................... ......... ............. 1

Jurisdiction ........................................................................ . 2

Question Presented ............................................................ 2

Constitutional Provision Involved .................................. 3

Statement ........................................................................... 3

Reasons Relied On For Allowance Of Writ ................... 8

Co n c l u s io n ........................................................... ............... 16

A ppendix

Opinion of District Court Denying Motion for

Further Relief .......... la

Opinion of Court of Appeals Affirming District

Court ....................................................................... 7a

Opinion of Court of Appeals on Rehearing........... 39a

T able of Cases :

Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction, 306 F. 2d

862 (5th Cir. 1962) .................................... ............. 8,11,13

Bailey v. Patterson, ------ F. 2 d ------ (5th Cir., Sept.

24, 1963, not yet reported) ................................ 14

Boson v. Rippy, 285 F. 2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960) ...........9,10

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 ....2, 3, 5,10,11

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 ...............8,15

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 308 F. 2d

491 (5th Cir. 1962) .... 8,11

11

PAGE

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ........................................ 10,11

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, Alabama, 318 F. 2d 63 (5th Cir. 1963) ....... 9

Evans v. Ennis, 281 F. 2d 385 (3d Cir. 1960) ............... 9

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction, 272 F. 2d 767

(5th Cir. 1959) ............................................................... 13

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction, 246 F. 2d 913

(5th Cir. 1957) ............................................................... 13

Goss v. Board of Education of the City of Knoxville,

373 U. S. 683 ....................................... .................. 8, 9,14,15

Goss v. Board of Education, 270 F. 2d 164 (6th Cir.

1962) ................................................................................. 9

Holland v. Board of Public Instruction, 258 F. 2d 730

(5th Cir. 1958) ............................................................... 11

Jackson v. School Board of City of Lynchburg, Vir

ginia, 321 F. 2d 230 (5th Cir. 1963) .......................... 9

Jones v. School Board of the City of Alexandria, 278

F. 2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960) ..........................................11,12,15

Northcross v. Board of Education of the City of Mem

phis, 302 F. 2d 818 (6th Cir. 1962) .......................11,12,15

Potts V. Flax, 313 F. 2d 284 (5th Cir. 1963) ................... 11

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham Board of Education, 358

U. S. 101, affirming 162 F. Supp. 372 (N. D. Ala.

1958) ............................................................... 4 n.3,10,13,14

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526 ....8,10,11,14,15

Ill

S tatutes and Other A uthorities :

PAGE

United States Code, Title 28, §1254(1) ........... ........... 2

Code of Alabama (Recompiled) §§61(1) et seq.......... . 13

Tennessee Code Annotated §§49-1741 et seq................. 13

Southern School News, September 1963 ......... ............ .4,16

Southern School News, October 1963 .......................... 16

I n the

(tart of % lotted

O ctober T erm , 1963

No.................

F red S. Calh o u n , et al.,

Petitioners,

—v.—

A. C. L atim er , et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit, entered in the above-entitled case on

June 17, 1963, rehearing of which was denied on August

16, 1963.

Citation to Opinions Below

The District Court’s opinion denying the further relief

sought and from which an appeal was taken to the court

below is reported at 217 F. 2d 614 and printed in the Ap

pendix hereto at page la.

Prior Findings of Facts, Conclusions of Law, Orders and

Judgments of the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Georgia, Atlanta Division (R. 13, 27,

2

55, 63, 69, 70, 302, 311),* reported at 188 F. Supp. 401 and

188 F. 2d 412 are not printed in Appendix hereto.

The opinions of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit, modifying and affirming the decision of

the District Court and denying petitioners’ petition for

rehearing en banc are printed in the Appendix, infra, at

7a, 39a, and reported in 321 F. 2d 828.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

June 17, 1963. Application for rehearing en banc was

denied on August 16, 1963 (A. 39a). The jurisdiction of

this Court is invoked under 28 U. S. C. §1254(1).

Question Presented

Respondents school authorities operate a biracial system

which, under court order, now allows children to transfer

to schools for the other race upon satisfying seventeen

pupil assignment criteria, leaving the dual system other

wise intact. This limited opportunity to transfer has been

given on a twelve year descending grade-a-year basis and

is now enjoyed by children in 12th, 11th, 10th and 9th

grades. In 1972 children will still have only this limited

right. Does not Brown v. Board of Education impose upon

respondents the affirmative duty to eliminate all racial

classifications by reorganizing the schools into a unitary

nonraeial system and to do so now much more quickly than

in twelve years!

* (R. — ) refers to Volumes 1-3 of the mimeographed record;

(A. — ) refers to the Appendix herein.

3

Constitutional Provision Involved

This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

Statement

As early as 1955, Negro parents in Atlanta began peti

tioning local school authorities to desegregate Atlanta’s

public school system in compliance with this Court’s deci

sion in Broivn v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S.

483 (1954) (R. 6, 306). Today, almost ten years after this

Court’s holding that racial segregation in public education

denies Negro children equal educational opportunities,

Atlanta’s segregated school system is still essentially

intact.

Atlanta now has a total public school population of

approximately 106,000—approximately 57,500 whites and

48,000 Negroes. Although Negroes constitute 45% of the

total, they have been allotted only 33% of the school build

ings and 40% of the teachers and principals; they suffer

serious overcrowding in certain schools and higher pupil-

teacher ratios (R. 86, 143, 144, 169, 199, 200).

Approximately four years after Brown, on January 11,

1958, petitioners, parents of Negro school children, brought

suit in a United States District Court to secure compliance.

More than three years later, in September, 1961, school

desegregation began with the admission of 10 Negro stu

dents in grades eleven and twelve to four formerly all-

white high schools (R. 100, 138).1 In September, 1962, 44

1 The District Court refused to require school authorities to com

mence desegregation in May, 1960 because it was of the opinion that

no action should be required until the Georgia Legislature made it

4

more Negro students were admitted to seven formerly

all-white high schools in grades twelve, eleven and ten

(R. 139-141, 188).2 3

They were admitted pursuant to a desegregation plan

approved by the District Court on January 20, 1960 (R. 55).

This plan provides for grade-a-year desegregation begin

ning with the 12th grade and proceeding, in reverse, a

grade a year. However, in order for any desegregation to

take place in any grade, applications by individual children

must be made between May 1st and 15th (R. 50) and must

be acted upon according to 17 pupil assignment criteria (R.

48-49).8 The plan maintains unimpaired the dual school

system (R. 88-91, 106-109). All racial assignments previ

ously made were frozen unless and until a transfer in

accordance with the plan is granted (R. 50). In short, a

person desiring desegregation may apply when the reverse

stair-step operation of the plan reaches his or her grade

level. But except as to that individual no other change can

be made.

Between May 1st and 15th, 1961, 129 Negro students in

grades eleven and twelve returned application forms for

possible for Atlanta to proceed without having its schools closed.

Because of this delay, the court ordered the school authorities to

desegregate the 12th and 11th grades pursuant to the court-

approved plan upon its commencement in 1961 (R. 63-69).

2 In September, 1963, a total of 145 Negro students were in for

merly all-white high schools in grades 12, 11, 10 and 9. Southern

School News, Sept. 1963, p. 8, cols. 1 and 5. Twenty-nine had been

previously admitted. .

3 The 17 criteria are identical with those of the Alabama pupil

assignment law upheld as constitutional on its face in Shuttlesworth

v. Birmingham Board of Education, 358 U. S. 101 (1958), affirming

162 F. Supp. 372 (N. D. Ala. 1958). Here, of course, the case in

volves application of such a plan, not its surface plausibility.

5

transfer to white high schools (E. 95, 137-139).4 From these

school authorities admitted 10 to 4 formerly all-white high

schools. The following year, 44 were selected out of 266

applicants (E. 139-141, 188).

The pupil assignment criteria were applied only to those

applicants, all Negroes, seeking transfer during the May

1st to 15th period to schools attended by pupils of the oppo

site race. All other applications for transfer, whites to

white schools and Negroes to Negro schools, were consid

ered “ informal” transfers and were made throughout the

school year (E. 189-194, 161-162).

April 30, 1962, after the first year of operation of the

plan, petitioners moved the District Court for further relief

(E. 77-84). Petitioners claimed that the plan, which had

been approved over their numerous objections, had not

resulted in desegregation (E. 81-82). They prayed for not

only a new plan to speed up desegregation but for one pro

viding prompt reassignment and initial assignment of all

students on some reasonable nonracial basis, e.g., the draw

ing of a single set of attendance area lines for all schools,

without regard to race, to replace the present dual scheme

of schoof attendance area lines for Negro and white schools.

Petitioners claimed the Brown case contemplated the re

assignment of teachers on a nonracial basis and the elimi

nation of all other racial distinctions in the operation of the

school system (E. 81). In short, petitioners sought an

integration of the dual school system into a unitary non

racial system with greater speed. Petitioners’ motion for

further relief was finally denied on November 15, 1962 on

the ground that the plan “ is eliminating segregation.” The

4 One white student sought a transfer from Northside High

School (white) to Dykes High School (white) because Northside

had been designated as a school to which Negroes would be ad

mitted. The white student’s application was denied (R. 138, 187).

6

teacher assignment issue was indefinitely deferred (R. 291).

This denial of further relief was flatly affirmed by the Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in a two-to-one decision

(A. 7a),5 Judge Richard T. Rives, dissenting.

The District Court’s refusal to grant any further relief

was squarely affirmed by the majority, on the ground that

certain deficiencies in the plan “would be adjusted by those

having charge of the schools, or upon their failure, by the

District Court” (A. 25a). Subsequently, upon denial of

rehearing, the majority issued a further opinion describing

corrective action to eliminate some of the discriminatory

characteristics of the plan. The majority stated that this

corrective action “must apply to transfers and assignments

for the 1963-64 term to the extent, if any, that the practices

giving rise to the deficiencies may have been continued in

use” (A. 40a). The deficiencies which the majority wrote

should be corrected were:

1. The plan must now be applied “ in an even handed

manner without regard to race to all assignments of

pupils new to a school for admission in a desegregated

grade in that school. (Emphasis added.)

2. The plan must be applied to all transfers, formal

and informal. (Emphasis added.)

3. Personality interviews, if utilized, may not be given

only to Negro students seeking assignment or transfer.

4. No transferee may be required to score a grade on

scholastic ability and achievement tests equal to the

average of the class in the school to which transfer is

sought.

5 The Court consisted of Judges Griffin B. Bell and David T.

Lewis of the 10th Circuit, sitting by designation, as well as Judge

Rives. Petition for rehearing was denied on August 16, 1963, Judge

Rives again dissenting.

7

5. No scholastic requirement may be used which is

limited to Negro students seeking transfer or assign

ment.

The petition for rehearing was denied August 16, 1963,

less than three weeks before the opening of school. How

ever, assuming the suggested corrections were made, the

practical results wTere the admission of approximately 116

more Negro students to 10 of the 16 formerly all white high

schools in grades 12, 11, 10, and 9 out of a total Negro

school population of approximately 48,000, with no white

pupils, who number at least 57,500, admitted to any of the

5 Negro high schools.6 In short, the majority opinion re

quired no speedup in the desegregation process and left

undisturbed all of the major props on which the dual system

rests. The majority left intact: 1) all existing racial as

signments in the high schools in grades 10-12; 2) the

“ feeder” system whereby certain Negro elementary schools

(grades 1-7) “ feed” certain Negro high schools (grades

8-12) and the same with respect to white elementary and

high schools, although the opinion seems to suggest the

plan be applied to all assignments at the point (grade 8)

where the feeder system takes hold; 3) all existing and

future racial assignments in the elementary schools made

pursuant to the dual scheme of attendance area lines;

4) all teacher assignments which are admittedly based on

race; 5) the five administrative areas plan whereby all

Negro schools are in Area One under the jurisdiction of a

Negro Area Supervisor;7 and 6) the grade-a-year feature

of the plan.

In other words, Atlanta still has, and for the future, will

have segregated schools from which Negro children must

6 See footnote 2, supra.

7 R. 107, 145, 171.

8

seek escape by taking an administrative initiative. Isolated

children may thereby get into “white” schools. The segre

gated system survives but for this token accommodation.

Reasons Relied On for Allowance of the Writ

The Decision Below Approving Respondents’ Desegre

gation Plan Conflicts With Prior Decisions of the Fifth

and Other Circuits and With the Applicable Decisions of

This Court.

1. Circuit Judge Richard T. Rives dissented below not

only on the ground the majority opinion disregarded this

Court’s admonition in Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S.

526 and Goss v. Board of Education of the City of Knox

ville, 373 IJ. S. 683, but also because that opinion repre

sented “ a step backward” for the Fifth Circuit which

previously had required other school districts, New Orleans,

Louisiana, Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 308 F. 2d

491 (5th Cir. 1962) and Pensacola, Florida, Augustus v.

Board of Public Instruction, 306 F. 2d 862 (5th Cir. 1962),

to abolish the dual school system.

In Watson, Memphis attempted to extend to public rec

reation the deliberate speed concept of Brown v. Board of

Education of Topeka, 349 U. S. 294 (1955). In holding the

concept inapplicable to public recreation, this Court warned

that the concept did not “ countenance indefinite delay” in

bringing about a transition from a segregated to a desegre

gated school system (at p. 534). The Court specifically

admonished that the passage of time since 1954 has con

siderably altered the type of plans which would now satisfy

the requirement of “ all deliberate speed.” However, de

spite the clear teaching of Watson, the majority below

approved, in 1963, eight years after this Court’s decision

requiring “deliberate speed,” a grade-a-year plan which

9

when completed will leave Atlanta with a system of token

ism based upon a foundation of fundamental segregation.

The majority approved Atlanta’s grade-a-year plan de

spite the fact that the Fifth Circuit, itself, had warned in

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County,

Alabama, 318 F. 2d 63 (5th Cir. 1963), that . . the amount

of time available for the transition from segregrated to de

segregated schools becomes more sharply limited with the

passage of the years since the first and second Brown de

cisions” (at p. 64).

Moreover, the Fifth Circuit previously had rejected plans

which provided for desegregation on a grade a year basis.

Boson v. Rippy, 285 F. 2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960). There the

Fifth Circuit ruled in approving a grade a year plan as a

start: “ In so directing, we do not mean to approve the

twelve-year, stair-step plan ‘insofar as it postpones full

integragtion’ ” (at p. 47).

The Third Circuit, as early as 1960, rejected the notion

that it would take 12 years to desegregate public schools

throughout the State of Delaware. It required an accelera

tion of the transition period in that state. Evans v. Ennis,

281 F. 2d 385, 389 (3rd Cir. 1960).

The Sixth Circuit having originally approved a twelve-

year plan for a school board which commenced desegrega

tion in 1956, Kelley v. Board of Education of City of Nash

ville, 270 F. 2d 209 (6th Cir. 1959), subsequently rejected a

similar plan commencing a grade-a-year in 1962. Goss v.

Board of Education, 301 F. 2d 164 (6th Cir. 1962), reversed

on other grounds 373 U. S. 683 (1963).

Twelve year plans to commence in 1962 also have been

rejected emphatically by the Fourth Circuit. In Jackson v.

School Board of City of Lynchburg, Virginia, 321 F. 2d 230

(4th Cir. 1963), after reviewing this Court’s decision in

10

Watson v. City of Memphis, the Fourth Circuit ruled: . .

the ‘grade-a-year’ plan, promulgated by the Lynchburg

School Board, for initial implementation eight years after

the first Brown decision, cannot now be sustained” (at p.

233).

The majority opinion below, therefore, clearly conflicts

with the prior decisions of the Fifth Circuit, itself, and the

decisions of three other circuits with respect to the length

of time which should now be allowed Atlanta in which to

desegregate its schools.

As the Fifth Circuit noted in Boson v. Rippy, supra, the

District Court’s approval of the 12 year plan for Atlanta in

January, 1960, which went into effect in September, 1961,

must be viewed as no more than the approval of a plan for

initiating a start toward desegregation. That these peti

tioners did not appeal from that approval in 1961, as Judge

Rives wrote, does not preclude them—a start having been

made—from seeking full compliance and seeking to set

aside a plan which demonstrably did not result in the de

segregation of the Atlanta schools, and which had been

administered to discriminate against Negroes although con

stitutional on its face. See, Shuttlesworth v. Board of

Education of the City of Birmingham, 358 TJ. S. 101 (1958)

affirming 162 F. Supp. 372 (N. D. Ala. 1958).

2. But more invidious than the twelve-year feature is

the denial of rights which will persist after twelve years are

gone. The majority ignored the fact that Brown struck

down the dual school system. It did not merely afford to

Negro pupils an opportunity to apply and to be subjected

to a number of criteria to determine their eligibility and

suitability for admission to “white” schools within the seg

regated framework.

In Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S. 483

(1954), 349 U. S. 294 (1955), Cooper v. Aaron, 358 IT. S. 1

11

(1958) and Watson v. City of Memphis, supra, this Court

made clear that the time allowed southern school authori

ties for affording Negro pupils their constitutional rights

was tolerable only because there is involved in these cases

the problem of transition from a segregated to a desegre

gated school system. These opinions speak in terms of

transforming school “ systems” and the holding in Brown

is that racial segregation in “public education” has no place.

347 U. S. 483, 495. In Cooper v. Aaron, supra, at page 7,

this Court directed the District Courts again to require “ ‘a

prompt and reasonable start toward full compliance,’ ” and

to “ take such action as was necessary to bring about the end

of racial segregation in the public schools. . . .” (Emphasis

added.) There was clearly never any thought that the

Brown decision was a license to continue the dual school sys

tems while affording to Negro children the opportunity to

apply for transfers to “white” schools within the “ separate-

but-equal” structure. The structure, itself, was doomed.

The Fifth Circuit in a prior decision, Potts v. Flax, 313

F. 2d 284 (5th Cir. 1963), had made this abundantly clear.

There a Negro claimed to have brought suit to desegregate

the schools on behalf of his children alone and denied that

he represented a class. The court ruled that even where a

single Negro sues the relief which must necessarily be

granted under Brown involves relief for Negroes as a class.

See also Holland v. Board of Public Instruction, 258 F. 2d

730 (5th Cir. 1958). In addition, the Fifth Circuit in prior

decisions specifically had required elimination of the dual

school system, Bush v. Orleans School Board, supra and

Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction, supra, by direct

ing elimination of dual school attendance areas for Negro

and white schools. The Fourth Circuit in Jones v. School

Board, of the City of Alexandria, 278 F. 2d 72, 76 (4th Cir.

1960) and the Sixth Circuit in Northcross v. Board of Edu

12

cation of the City of Memphis, 302 F. 2d 818, 823 (6th Cir.

1962) have also imposed such a requirement. In Northeross

the court said:

“ Minimal requirements for nonracial schools are geo

graphic zoning, according to the capacity and facilities

of the buildings and admission to a school according to

residence as a matter of right. ‘Obviously, the mainte

nance of a dual system of attendance areas based on

race offends the constitutional rights of the plaintiffs

and others similarly situated and cannot be tolerated.’

Jones v. School Board of the City of Alexandria, Vir

ginia, 278 F. 2d 72, 76, C. A. 4.” (At p. 823).

The majority opinion does not require Atlanta to abolish

dual school attendance areas. As Judge Fives points out in

his dissenting opinion, both the District Court and the ma

jority below overlook the record with respect to present

existence of a dual system of school attendance area lines in

Atlanta (A. 32a-33a, footnote 4).

^ince the Fifth Circuit previously had ordered New Or

leans and Escambia County, Florida to abolish dual attend

ance area lines, it is obvious that the majority opinion not

only represents a step backwards for that circuit which

had recognized that the Brown case required the reor

ganization of the dual school system into a unitary non

racial system but conflicts with decisions of the Fourth and

Sixth Circuits which also require reorganization. Jones v.

School Board of the City of Alexandria, supra and North-

cross v. Board of Education of the City of Memphis, supra.

3. The decision below also conflicts with the decision of

the Sixth Circuit in Northcross v. Board of Education City

of Memphis, 302 F. 2d 818 (6th Cir. 1962) enjoining use

of the Tennessee Pupil Assignment Law as a vehicle for

desegregating the public school system of Memphis which,

13

like Atlanta’s plan, requires Negroes to apply for that to

which they are already entitled. The Atlanta plan incorpo

rated 17 criteria of the Alabama Pnpil Placement Law

which had been held constitutional on its face by this Court

with the. admonition that it might subsequently be held un

constitutional with respect to its administration. Shuttles-

worth v. Board of Education of the City of Birmingham,

supra. The Sixth Circuit has barred use of Tennessee’s

Pupil Assignment Law as a plan of desegregation whereas

the opinion below, in effect, adopts the Alabama Pupil

Placement Law as a plan of desegregation.8 Again, the

Fifth Circuit had previously ruled that the Florida Pupil

Assignment Law, standing alone, was not a plan of desegre

gation. Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction, 272 F. 2d 767

(5th Cir. 1959) and 246 F. 2d 913 (5th Cir. 1957) and

Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction, 306 F. 2d 862 (5th

Cir. 1962).

Petitioners here had challenged by their motion for fur

ther relief the application of the Atlanta plan. Petitioners

claimed first that the plan had not been used to bring

about desegregation but had been used to maintain segre

gation. Admission of 10 Negroes out of 129 in September

1961 and 44 out of 266 in September 1962 pursuant to

criteria applied only to these Negro applicants seeking

transfer to white schools, established beyond question the

discriminatory application of the plan. The majority did

not direct the District Court to enjoin discriminatory

application of the plan. Instead, it ruled that petitioners

should first have complained of their grievances with

respect to the administration of the plan to the Board

and, upon the Board’s failure to remedy same, appeal to

the District Court. Even upon rehearing the majority did

8 The Tennessee and Alabama Pupil Assignment Laws are essen

tially identical in all material respects. Compare Tenn. Code Ann.

§§ 49-1741 to 49-1763 with Code of Ala. (Recompiled) §§ 61(1) to

61(11).

14

not direct the District Court to enjoin discriminatory

application of the plan and again assumed that the cor

rective action which it outlined in its opinion would be

taken by the Board, and if not, that petitioners would return

once again to the District Court and again seek an end to

discriminatory application of the plan.

• Petitioners say, however, that Atlanta, as this Court

warned in the Shuttlesworth case, having administered a

pupil assignment plan in an unconstitutional manner,

should have been enjoined from further use of the plan.

Bailey v. Pattersonp------ F. 2 d ------ (5th Cir., Sept. 24,

1963, not yet reported). Atlanta has demonstrated by its

failure to apply all criteria to all students in even a single

grade the manifest impracticability for a school board

the size of Atlanta to administer any such onerous pupil

assignment plan.

The majority opinion, therefore, conflicts not only with

the opinion of the Sixth Circuit in the Northcross case

barring use of a pupil assignment law as a vehicle for

desegregation but conflicts with the clear warning of this

Court in the Shuttlesworth case concerning unconstitu

tional administration of a pupil assignment law.,

4. Another major prop of the segregated school system

which the majority opinion leaves standing is the segre

gated staff. In Atlanta, as elsewhere, the schools are

segregated not only because in every seat in a Negro school

is a Negro child but in front of every class is a Negro

teacher. Atlanta goes further, as do other school dis

tricts, in placing all Negro schools under the direction of

a Negro Supervisor (R. 107, 145, 171).

The District Court in this case postponed indefinitely

consideration of the assignment of Negro teachers on a

nonracial basis. Again, such deferment, per se, is con

trary to this Court’s admonition in Watson and Goss v.

15

Board of Education of City of Knoxville, 373 U. S. 683,

that the time has come for full compliance with this Court’s

decision and the end of built-in devices for maintaining

segregation. Contrary to the opinion of this Court and

other circuits, clearly indicating that the relief to be

afforded in these cases encompasses the entire school sys

tem, including personnel, Brown v. Board of Education of

Topeka, 349 U. 8. 294, 300-301 (1955); Northcross v. Board

of Education of the City of Memphis, supra,, at p. 819;

Jackson v. School Board of the City of Lynchburg, supra,

at p. 233, the court below postponed without day considera

tion of this problem.

5. The additional vice of the opinion below is that un

reversed the majority opinion means that soon another

whole generation of Negro students will graduate from

Atlanta’s “ separate but equal” public school system with

the promise of equality made in 1954 unredeemed. As this

Court said in Watson v. City of Memphis, supra, at p. 535:

“ The rights here asserted are, like all such rights, present

rights; they are not merely hopes to some future enjoy

ment of some formalistic constitutional promise. The basic

guarantees of our Constitution are warrants for the here

and nowT and, unless there is an overwhelmingly compel

ling reason, they are to be promptly fulfilled.” Not only

is the result of the majority opinion inconsistent with the

great promise of equality envisioned by this Court’s 1954

decision, but the majority opinion^ so clearly guarantees

the continuation of “ separate but equal” that three other

major school districts, Savannah, Georgia, Birmingham,

Alabama and Mobile County, Alabama, ordered to com

mence desegregation in September 1963, by the Fifth Cir

cuit, pending appeal, immediately adopted the Atlanta

plan which had just been approved. As a result, Savannah

admitted 21 Negro students to the twelfth grade out of a

school population of 24,013 whites and 15,336 Negroes.

16

Birmingham admitted 5 to the twelfth grade out of a

school population of 37,500 whites and 34,834 Negroes.

Mobile County admitted 2 to the twelfth grade out of a

school population of 47,247 whites and 30,020 Negroes.9

The majority opinion thus has established the pattern of

the future.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, this Petition for a Writ of

Certiorari should be granted.

Bespectfully submitted,

Constance B aker M otley

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

E. E. M oore

Suite 201

175 Auburn Avenue, N. E.

Atlanta, Georgia

D onald L . H ollowell

Cannolene Building (Annex)

859% Hunter Street, N. W.

Atlanta, Georgia

Attorneys for Petitioners

N orman A maker

A . T . W alden

J. L eV onne C hambers

Of Counsel

9 See Southern School News, Sept. 1963, p. 2, col. 3; p. 3, cols. 2-4-

p. 8, col. 1; id., Oct. 1963, p. 10, col. 3.

APPENDIX

A P P E N D IX

Opinion o f Hooper, District Judge

Nov. 15, 1962.

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

N. D. G eorgia— A tlanta D ivision

Civ. A. No. 6298.

V ivian Calh o u n , et al.

A. 0. L atim er , et al.

H ooper, District Judge.

S tatem ent of the Case.

This Court on January 20, 1960 approved a Plan of

desegregation proposed by defendant Atlanta Board of

Education. Details of that Plan may be obtained by refer

ence to Calhoun v. Members of Board of Education, D. C.,

188 F. Supp. 401 and D. C., 188 F. Supp. 412. On Sep

tember 13, 1960 the Court provided the Plan in question

should begin in September, 1961 and apply to the eleventh

and twelfth grades of the schools. The Plan has been in

operation for the two school years beginning September,

1961 and September, 1962 respectively, and pursuant

thereto fifty-three Negro students have transferred from

schools previously Negro schools to schools previously all

white schools. This was done peaceably and without vio

lence, largely due to the unusually effective methods em

2a

Opinion of Hooper, District Judge

ployed by the Mayor of Atlanta, its Chief of Police, and all

groups working in concert with them.

The Plan adopted by this Court on January 20, 1960 was

the Plan which was adopted upon the insistence of plain

tiffs in order to comply with the mandates of the United

StateTBupreme Court and other courts, to the effect that

discrimination should cease and that compulsory segrega

tion should no longer be enforced in the Atlanta Public

Schools.

It is significant to note that the Plan in question at the

time of its adoption met with the approval of these plain

tiffs. An appeal from this Order of Court was filed but

upon motion of the plaintiffs was permitted to be dismissed

by the Court of Appeals.

G rounds of th e M otion .

A large part of the motion filed April 30, 1962 is couched

in vague and indefinite terms and is largely a repetition of

charges made against defendants concerning discrimination

before the Plan had been put into operation. Thus plain

tiffs seek an injunction against defendants “ from continu

ing to maintain and operate a segregated bi-racial school

system,” from “ continuing to assign pupils to the public

schools upon the basis of race and color,” from “ continuing

to designate schools as Negro or white,” from maintaining

“ racially segregated extracurricular school activities.”

Complaint is also made of alleged assigning of teachers

and others on basis of race and color and maintaining a

dual system of school attendance area lines.

[1, 2] There is no disputing that discrimination had

existed prior to the Order of this Court of January 20,

1960, and that the Order of that date was designed to elimi-

3a

nate the discrimination over a period of years. Even plain

tiffs’ counsel upon the original trial disclaimed any purpose

of seeking to have “wholesale integration.” The only ques

tion then involved was the plan by which discrimination

could be eliminated; a Plan was carefully prepared and

adopted and no appeal taken. The Plan is eliminating

segregation, but until it has completed its course there will

of course still be areas (in the lower grades) where segre

gation exists. The Court is therefore at a loss to see how

anything could be accomplished at this time by “ an order

enjoining defendants from continuing to maintain and

operate a segregated, bi-racial school system,” for the

Court has already taken care of that in its decree of Janu

ary 20, 1960. There is no evidence that defendants are

“ continuing to designate schools as Negro or white,” nor

that they are maintaining “ racially segregated extra

curricular school activities.”

The assigning of teachers and other personnel on the

basis of race and color is not now passed upon but is de

ferred (as other courts have done) awaiting further prog

ress made in the desegregation of the students.

[3] The objection to said Plan of Desegregation which

most impressed this Court related to the charge that it

caused discrimination between a Negro transferring to a

grade in a previously white school, in that certain tests

were required for the transfer to which the white students

promoted to the same grade were not subjected. At the

hearing of this motion, however, it appeared without dis

pute that defendants beginning in September 1962 had

ceased using the tests required of transfers as used there

tofore. In lieu thereof as of September 1962 the school

authorities gave to all pupils in the school system a nation

ally recognized test known as the “ School and College Abil-

Opinion of Hooper, District Judge

4a

ity Test” (SCAT). (See Transcript, p. 22.) Testimony of

Superintendent John Letson shows that this test was given

to all students, Negro and white, and this testimony was not

disputed. Proximity of the pupil to the school involved was

also considered by the Board, as were certain other criteria

contained in the Plan approved by this Court on January

20, 1960.

[4] Neither does the evidence show that defendants are

maintaining a “ dual system of school attendance area

lines.” Proximity to the schools in question is a factor con

sidered by the defendant Board. It is not shown that de

fendants are acting arbitrarily in connection with the

assignment of pupils in relation to their distance from the

school. It does appear that area lines (where such exist)

are sometimes changed for the sole purpose of relieving

over-crowded conditions in the schools.

P lain tiffs ’ P roposed N ew P l a n .

[5] The original motion filed by plaintiffs on April 30,

1962 made certain attacks on the Plan of Desegregation

established January 20, 1960, but did not make any com

plaint that the Plan contemplated too much time for the

completion of the desegregation. Not until the Court re

quiredAhe parties Jo' file Findings of Fact and Conclusions

of Law did it occur to plaintiffs to make any effort to speed

up the transition^ However, on July 20, 1962 plaintiffs filed

a paper entitled “Plaintiffs’ Proposed Plan of Desegrega

tion,” which does bear some similarity to the Plan adopted

by the Court on January 20, 1960, already in operation for

a period of two years. However, the Proposed Plan accel

erates the dates to which the various grades might be in

tegrated (which in September 1963 include the ninth, tenth,

Opinion of Hooper, District Judge

5a

eleventh and twelfth grades) so that in September 1965 “ all

pupils and personnel in grades one, two and three shall be

desegregated in the same manner in which the other grades

are desegregated, as set forth above.”

This suggestion by plaintiffs’ counsel that the Court sum

marily speed up the Plan already adopted without any

evidence to show that the new Plan is practicable or feasi

ble, is no doubt inspired by one or more recent decisions by

appellate courts which do summarily establish a Plan of

Desegregation. In all such instances, however, that action

was taken by appellate courts because the school authorities

in question had not proposed a Plan, or the district judge

in question had not ordered a Plan. This Court finds no

precedent for a trial judge summarily changing and speed

ing up a Plan, already in operation for two years, without

some facts or circumstances requiring the same.

When this Court approved the Plan on January 20, 1960

many local conditions mitigating against a more speedy

transition were considered (see 188 P. Supp. 401), these

factors included the following:

There were in Atlanta 116,000 pupils, of which approxi

mately forty per cent, or some 46,400, were Negroes. There

was a rapid influx of children of school age into the city and

a shortage of some 580 class rooms, many classes then being

held in churches and other buildings, and many having

double sessions. Other problems confronted the School

Board, caused by slum clearances and changes in residen

tial patterns, to which may now be added complications

arising out of large tracts of land being condemned for

expressways.

The United States Supreme Court has ordered that seg

regation be eliminated “with deliberate speed,” and has

invested the trial judges in the first instance with some

Opinion of Hooper, District Judge

6a

discretion, bearing in mind all local conditions, as to the

timing of a Plan of Desegregation. The Plan heretofore

approved by this Court, and now under attack, has been

administered fairly and in good faith by defendant Atlanta

Board of Education, the local authorities have given utmost

cooperation in maintaining law and order, and the number

of students being transferred each year from previously

designated colored schools to previously designated white

schools is increasing at an accelerated rate each year as the

lower grades are reached. This Court feels that the public

interests demand that the Plan now in operation be con

tinued according to its terms and not be summarily dis

placed by the new Plan of Desegregation proposed by

plaintiffs.

For reasons set forth above plaintiffs’ motion for further

relief and plaintiffs’ motion to adopt a Proposed New Plan

of Desegregation are denied.

Opinion of Hooper, District Judge

7a

I n t h e

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F or th e F if t h C ircuit

No. 20273

Opinion o f Bell, Circuit Judge

V ivian Calh o u n , et al., Infants, by F red Calh o u n ,

their father and next friend, et al.,

—versus-

Appellants,

A. C. L atim er, et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA.

(June 17, 1963)

Before R ives, L ew is* and B ell , Circuit Judges.

B ell , Circuit Judge:

I.

This appeal from an order denying a motion for further

relief brings up for review, for the first time,* 1 the plan for

the desegregation of the Atlanta school system. The plan

* Of the Tenth Circuit, sitting by designation.

1 Appellants filed notice of appeal from the order of the court

dated March 9, 1960 refusing to make the plan effective for the

school term 1960-61 but dismissed the appeal.

8a

was formulated pursuant to court order, and approved by

the court on January 20, 1960. It became effective on May

1, 1961 for the school term 1961-62 beginning in September

1961. It was applied to the twelfth and eleventh grades

at that time for the purposes of desegregation, to the tenth

grade beginning with the 1962-63 school term, and will be

applied to the ninth grade beginning with the 1963-64 school

term. It is to be applied progressively to the next succeed

ing grade each school term thereafter until all grades in the

school system have been included, and desegregated.

The sequence of events in this case began with the filing

of a complaint on January 11, 1958 by appellants seeking

the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution; Brown v. Board of

Education of Topeka, 1954, 347 U. S. 483, 74 S. Ct. 686, 98

L. Ed. 873, having proscribed racial discrimination in public

education. The District Court had first enjoined appellees,

members of the Board of Education of the City of Atlanta,

and the school superintendent, from enforcing and pursu

ing the policy, practice, custom, and usage of requiring or

permitting racial segregation in the operation of the

schools, and from engaging in any and all action which lim

ited or affected admission to, attendance in, or the educa

tion of the appellant children, or any other Negro children

similarly situated, in the schools on the basis of race. A

reasonable period of time was allowed within which to com

ply with the order, and for bringing about a transition to a

school system not operated on the basis of race. The school

board was required to present a plan on or before Decem

ber 1, 1959 designed to bring about compliance with the

order, and which would provide for a prompt and reason

able start toward desegregation of the public schools of

Atlanta, and a systematic and effective method for achiev

ing such desegregation with all deliberate speed.

Opinion of Bell, Circuit Judge

9a

A plan was submitted, contingent upon the enactment of

statutes by the State of Georgia permitting the same to be

put into operation. It provided procedures of uniform ap

plication for the assignment, transfer, or continuance of

pupils among and within the schools of the system. The

plan was largely modeled upon the placement law approved

as constitutional on its face in Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham

Board, of Education, 1ST. D. Ala., 1958, 162 F. Supp. 372,

affirmed, 358 U. S. 101,79 S. Ct. 221, 3 L. Ed. 2d 145. It was,

however, amended in various respects by court order before

final approval to meet some of the objections of appellants.

There was also objection to the plan being contingent upon

changes in the state laws which then required segregated

schools, under penalty, among others, of loss of state finan

cial support. The court limited the contingency to one year

and included two grades in the plan for the first year of its

operation. It was to be invoked for the 1961-62 school year

in any event. See Calhoun v. Members of Board of Educa

tion, City of Atlanta, N. D. Ga., 1959, 188 F. Supp. 401, 188

F. Supp. 412.

Opinion of Bell, Circuit Judge

II.

The Georgia laws were changed, obviating harm to public

education, and making it possible for the plan of the school

board to proceed on schedule. Schools were no longer classi

fied as white or Negro, but the plan did contemplate that

each child would continue in the school to which assigned

for the then present school term unless and until trans

ferred, on request, to another school. Applications for

transfer were to be filed between May 1 and May 15 in each

school year. This was the method of transition agreed upon

rather than some other plan requiring reassignment by

school officials. Any child was free to seek transfer to the

grades within the plan.

Opinion of Bell, Circuit Judge

Some three hundred Negro children and one white child

obtained application forms for transfer for the 1961-62

term. Only one hundred and thirty of these were actually

filed by Negro children. Ten of these were granted and re

assignment was made to the eleventh and twelfth grades of

formerly white schools. The transfer sought by the white

child out of one of these schools because Negroes were to

be admitted was denied.. See Stone v. Members of the Board

of Education City of Atlanta, 5 Cir., 1962, 309 F. 2d 638.

At this time there were one hundred thirteen elementary

schools, grades one through seven, and twenty-two high

schools, grades eight through twelve, in Atlanta. There

were no junior high schools. Forty-one of the elementary

schools were all Negro in attendance while seventy-two were

all white. This is still true since the plan has not reached

the elementary grades. There were five all Negro and sev

enteen all white high schools. This latter number was re

duced to thirteen by the transfer of the ten Negro students.

Forty-four additional Negro students, out of some two hun

dred sixty-six requesting transfer, were transferred, to

white high schools for the 1962-63 term resulting in the

desegregation of seven additional formerly all white

schools. The result to date is that there are eleven inte

grated high schools in Atlanta, five all Negro high schools

and six all white high schools.

Special intelligence tests were given those students seek

ing transfer under the plan in 1961, but this requirement

was abandoned prior to 1962; thus, our discussion will cen

ter on the practices and procedures required under the plan

for 1962. Only a few of the seventeen factors or criteria set

out in the plan were used. A scholastic ability and achieve

ment test routinely given to every child in the grades in

question in the school system was used in considering the

11a

applications. The standard used was that the transferee

had to score a grade at least equal to the average of the

class in the school to which transfer was requested. Such a

requirement is, of course, discriminatory per se when ap

plied only to Negro students. Proximity of the residence of

the student to the school in question, subject to variation

for educational reasons, and also the reasons given on the

application for the requested transfer were other factors

used. Each student was also given a personality interview

by school officials to determine probable success or failure

in the new school.2 * 4

When the plan became effective, all students in the grades

to be segregated were already assigned to high schools.

Thus, the plan to date encompasses only those students

wishing to transfer, and new students entering a school for

the first time in the desegregated grades. However, it has

not been applied to new students, nor to those students

being transferred at times other than during the period

May 1 to May 15 under the plan. Transfers, other than

during this period, not substantial in number, are known

to the school board as informal transfers, and are to be

distinguished from transfers under the plan, called formal

transfers.

There is no evidence that the criteria applied in informal

transfers were racially discriminatory as among informal

transferees,. but they were apparently different from the

criteria applied in formal transfers. The school superin

tendent testified that the criteria applied in formal transfers

Opinion of Bell, Circuit Judge

2 Such solicitude has rightly been condemned where applied only

to Negroes, Green v. School Board of the City of Roanoke, Virginia,

4 Cir., 1962, 304 F. 2d 118, although it would appear, where done

in good faith, and there is no contrary contention here, to lend

itself, at least in the early days of transition, to assuring the suc

cess of a plan.

12a

included the reason given by the student for requesting

transfer, tests that were a part of his permanent record,

grades, teacher opinion and educational judgment as to

whether the request, for these reasons, would be educa

tionally justified. Also considered was proximity of resi

dence to school and the capacity of the school. The

difference in the requirements for formal and informal

transfers, in the main, was that no personality interview

was required for informal transfers, nor does it appear

that the standard of scholastic ability basis was the same.

The form used in requesting transfers as well as the plan

itself is designed to apply in the admission and assignment

procedure, as well as in the transfer procedure. The Dis

trict Court said in this regard:

“ Essentially the Plan contemplates that all pupils

in the schools shall, until and .unless transferred to

some other school, remain where they are, all new and

beginning students being assigned by the Superintend

ent or his authority to a school selected by observance

of certain standards as set forth in the proposed Plan.”

188 F. Supp. 401, 406, supra.

Not one of the Negro applicants for transfer has com

plained individually to the District Court at any time. The

case is still proceeding as a class action. Both appellants

and the school board were satisfied to rely largely on the

testimony of the school superintendent. His testimony in

substance was that the board was abiding the letter and the

spirit of the plan approved by the court. Pupils were as

signed to schools they attended the previous year in order

to establish a base from which they were free under the plan

to request a transfer. He contended that the Atlanta school

system was desegregated and pointed out that all mention

Opinion of Bell, Circuit Judge

13a

oi race had been removed from the school directory, official

reports, building programs, and all other classifications.

Schools are no longer designated as white or Negro. Negro

students assigned to previously all white schools partici

pated in both regular and extra-curricular activities, includ

ing honor banquets, clubs and other activities on the basis of

free choice, and their parents attended Parent-Teacher As

sociation meetings, athletic events, graduation programs

and other school activities free of racial discrimination.

School events to which the public is invited are not segre

gated, nor are meetings of professional committees.

He testified that there were no attendance areas or zone

lines established by the board, but that lines are sometimes

drawn administratively between schools in an attempt to

equalize class loads. There was no evidence before the

court that they were based on race. The Atlanta system is

divided into five sub-areas with an assistant superintendent

in charge of each area. One sub-area has only all Negro

schools in it, but there is no evidence of white children liv

ing in it, or that it resulted from gerrymandering.8

Another pertinent fact is that there is overcrowding in

the school system particularly in those schools still having

all Negro populations, with additional schools being needed.

Some white schools are under populated. The growth in

the school population in recent years is almost entirely

Negro, with considerable change in area patterns from the

standpoint of changing from white to Negro residents. 3

Opinion of Bell, Circuit Judge

3 The dearth of evidence probably results from the parties each

taking the position that the burden of proof was on the other.

The burden is plainly on the board to justify the plan and the

delay under it. Having done so and having obtained the approval

of the court, we think that the burden shifted to appellants to at

least make a prima facie showing that changes were in order.

14a

The District Court in this case, after hearing all evidence

offered, and full arguments, held:

“ There is no disputing that discrimination had ex

isted prior to the Order of this Court of January 20,

1960, and that the Order of that date was designed to

eliminate the discrimination over a period of years.

Even plaintiffs’ counsel upon the original trial dis

claimed any purpose of seeking to have ‘wholesale in

tegration.’ The only question then involved was the

plan by which discrimination could be eliminated; a

Plan was carefully prepared and adopted and no appeal

taken. The Plan is eliminating segregation, but until it

has completed its course there will of course still be

areas (in the lower grades) where segregation exists.

The Court is therefore at a loss to see how anything

could be accomplished at this time by ‘an order enjoin

ing defendants from continuing to maintain and oper

ate a segregated, biraciai school system,’ for the Court

has already taken care of that in its decree of January

20, 1960. There is no evidence that defendants are

‘continuing to designate schools as Negro or white,’ nor

that they are maintaining ‘racially segregated extra

curricular school activities.’

“ The assigning of teachers and other personnel on

the basis of race and color is not now passed upon but

is deferred (as other courts have done) awaiting fur

ther progress made in the desegregation of the stu

dents.

# # * # #

“ Neither does the evidence show that defendants are

maintaining a ‘dual system of school attendance area

lines.’ Proximity to the schools in question is a factor

considered by the defendant Board. It is not shown

Opinion of Bell, Circuit Judge

15a

that defendants are acting arbitrarily in connection

with the assignment of pupils in relation to their dis

tance from the school. It does appear that area lines

(where such exist) are sometimes changed for the sole

purpose of relieving overcrowded conditions in the

schools.

# * # # #

“ . . . The Plan heretofore approved by this Court,

and now under attack, has been administered fairly and

in good faith by defendant Atlanta Board of Educa

tion, the local authorities have given utmost coopera

tion in maintaining law and order, and the number of

students being transferred . . . from previously desig

nated colored schools to previously designated white

schools is increasing at an accelerated rate each year as

the lower grades are reached. This Court feels that

the public interests demand that the Plan now in opera

tion be continued according to its terms and not be

summarily displaced by the new Plan of Desegregation

proposed by plaintiffs.” Calhoun v. Latimer, N. D. Ga.,

1962,------F. Supp.------- , 7 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1054.

III.

The questions presented may be reduced to four in num

ber. First, can the Atlanta plan be justified in the light of

the results of its operation to date, and in view of the teach

ings of Brown, supra, the second Brown case, 1955, 349

IT. S. 294, 75 S. Ct. 753, 99 L. Ed. 1083, Cooper, infra, and

the most recent decisions of this court, handed down long

after the, Atlanta plan became effective. Bush v. Orleans

Parish School Board, 5 Cir., 1962, 308 F. 2d 491; and Au

gustus v. The Board of Public Instruction of Escambia

County, Florida, 5 Cir., 1962, 306 F. 2d 862. Second, assum-

Opinion of Bell, Circuit Judge

16a

ing that it may, has it been applied in a discriminatory man-

ner? This includes the questions of admission, assignment,

transfers, both formal and informal, and extra-curricular

activities. Third, was it error for the District Court to post

pone consideration of the practice relating to the assign

ment of teachers? Fourth, did the court err in not speeding

up the plan as suggested by appellants?

And with these facts before us, we begin the consideration

of the questions presented with the mandate of the Supreme

Court in the second Brown opinion in mind. There the

court, with regard to eliminating racial discrimination in

public education following its decision in the first Brown

case, supra, said:

“ Full implementation of these constitutional princi

ples may require solution of varied local school

problems. School authorities have the primary respon

sibility for elucidating, assessing, and solving these

problems; courts will have to consider whether the

action of school authorities constitutes good faith im

plementation of the governing constitutional principles.

Because of their proximity to local conditions and the

possible need for further hearings, the courts which

originally heard these cases can best perform this

judicial appraisal. . . .

“ In fashioning and effectuating the decrees, the

courts will be guided by equitable principles. Tradi

tionally, equity has been characterized by a practical

flexibility in shaping its remedies and by a facility for

adjusting and reconciling public and private needs.

These cases call for the exercise of these traditional

attributes of equity power. At stake is the personal

interest of the plaintiffs in admission to public schools

as soon as practicable on a nondiscriminatorv basis.

Opinion of Bell, Circuit Judge

17a

To effectuate this interest may call for elimination of

a variety of obstacles in making the transition to school

systems operated in accordance with the constitutional

principles set forth in our May 17, 1954, decision.

Courts of equity may properly take into account the

public interest in the elimination of such obstacles in a

systematic and effective manner. But it should go with

out saying that the vitality of these constitutional prin

ciples cannot be allowed to yield simply because of

disagreement with them..

“ While giving weight to these public and private con

siderations, the courts will require that the defendants

make a prompt and reasonable start toward full com

pliance with our May 17, 1954, ruling. Once such a

start has been made, the courts may find that additional

time is necessary to carry out the ruling in an effective

manner. The burden rests upon the defendants to es

tablish that such time is necessary in the public interest

and is consistent with good faith compliance at the

earliest practicable date. To that end, the courts may

consider problems related to administration, arising

from the physical condition of the school plant, the

school transportation system, personnel, revision of

school districts and attendance areas into compact

units to achieve a system of determining admission to

the public schools on a nonracial basis, and revision

of local laws and regulations which may be necessary

in solving the foregoing problems. They will also con

sider the adequacy of any plans the defendants may

propose to meet these problems and to effecutate a

transition to a racially nondiscriminatory school sys

tem. During this period of transition, the courts will

retain jurisdiction of these cases.”

Opinion of Bell, Circuit Judge

18a

And see Cooper v. Aaron, 1958, 358 U. S. 1, 78 S. Ct. 1401,

3 L. Ed. 2d 5, where, after reiterating what was said in the

Brown implementation decision, and the investiture of su

pervisory powers in the District Courts for the necessary

transition from segregated to desegregated school systems,

the court said:

“Under such circumstances, the District Courts were

directed to require ‘a prompt and reasonable start

toward full compliance,’ and to take such action as was

necessary to bring about the end of racial segregation

in the public schools ‘with all deliberate speed.’ . . . Of

course, in many, locations, obedience to the duty of

desegregation would require the immediate general ad

mission of Negro children, otherwise qualified as

students for their appropriate classes, at particular

schools. On the other hand, a District Court, after anal

ysis of the relevant factors (which, of course, excludes

hostility to racial desegregation), might conclude that

justification existed for not requiring the present non-

segregated admission of all qualified Negro children.

In such circumstances, however, the courts should

scrutinize the program of the school authorities to

make sure that they had developed arrangements

pointed toward the earliest practicable completion of

desegregation, and had taken appropriate steps to put

their program into effective operation. . .

Nothing then could stay the inexorable hand of the Con

stitution in this regard. Some school boards complied with

out the intervention of the courts. Others acted under court

order, as did the Atlanta board. The cases arising are

myriad, but each, with respect to transition, goes back to

the fountainhead, Brown and Cooper. Does the plan as

Opinion of Bell, Circuit Judge

19a

conceived and administered comport with the constitutional

mandate and the duty imposed on school boards and Dis

trict Courts? Gradualism in desegregation, if not the usual,

is at least an accepted mode with the emphasis on getting

the job of transition done.

Opinion of Bell, Circuit Judge

IV.

The questions here may be the better discerned in the

background of what appellants offered by way of a plan

in the District Court. The plan proposed by them in con

nection with the motion for further relief which is the sub

ject matter of this appeal suggested a speed up of five years

in the original twelve year plan for transition. Their sug

gestion was that grades eight and nine rather than nine be

desegregated in September 1963. They would desegregate

grades four, five, six and seven in September 1964, and

grades one, two and three in September 1965. They would

reassign all high school teachers, counselors, principals and

supervisors prior to the opening of school in September

1963 on the basis of qualification and need without regard to

race or color. The same procedure would be followed as to

such personnel on the succeeding years in connection with

the proposed desegregation procedure. All school spon

sored, school related, school supported, school sanctioned

extra-curricular school activities would be open to all

qualified students without regard to race or color as each

grade is desegregated. Desegregation would be provided on

the basis of drawing school zone lines for each school and

assigning all children living in the zone to the school with

out regard to race or color. It is this last suggestion that is

the bare bones of this case and which gives rise to the first

question.

20a

Appellants do not object to a gradual plan. They do seek

to speed it up from a twelve to a seven year span for accom

plishment. What they object to is that feature of the court

approved plan that permits the continued assignment of

those children already in school to the same schools with the

right to transfer. This question has not heretofore been

before this court. We held in Bush v. Orleans Parish School

Board, supra, and in Augustus v. The Board of Public In

struction of Escambia County, Florida, supra, that dual

school districts must be abolished as they related to the

grades being desegregated. We have never laid out a

method of abolishment, or adopted a policy of absolutism.

The Atlanta plan of abolishment is one of gradualism by

permitting transfers from present assignments. The New

Orleans plan in Bush, formulated by the District Court in

stead of the school board, begins with the first grade. It rec

ognizes the dual system and provides for its elimination by

permitting the children, at their option, to attend either the

formerly all white or all Negro school nearest their homes,

with transfers to be allowed provided they are not based on

consideration of race. The Houston plan which was also

court formulated, R.oss v. Dyer, 5 Cir., 1962, 312 F. 2d 191,

is substantially like that of New Orleans. We do not yet

know what method of eliminating the dual system is to be

used in the Escambia County case. Even if it may be said

that there is a dual system in Atlanta, and the evidence does

not so disclose,4 it can also be said that there is an option

under the Atlanta plan just as there is under the New Or

leans and Houston plans, assuming the plan is applied to

transfers as well as assignments of all new students in

4 The dual system undoubtedly continues in the grades not yet

reached by the plan. It exists in residual form in the grades

reached because desegregation has not reached the elementary school

grades which feed the high schools.

Opinion of Bell, Circuit Judge

21a

desegregated grades, and is not based on consideration of

race.

This court disapproved one feature, in the nature of an

option, of a plan for desegregating the Dallas school system