Ford v. Wainwright Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 30, 1986

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ford v. Wainwright Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amici Curiae, 1986. 5e59ab15-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0b7b8ae4-b7c8-4b22-be5f-d7982806ff73/ford-v-wainwright-motion-for-leave-to-file-and-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

y

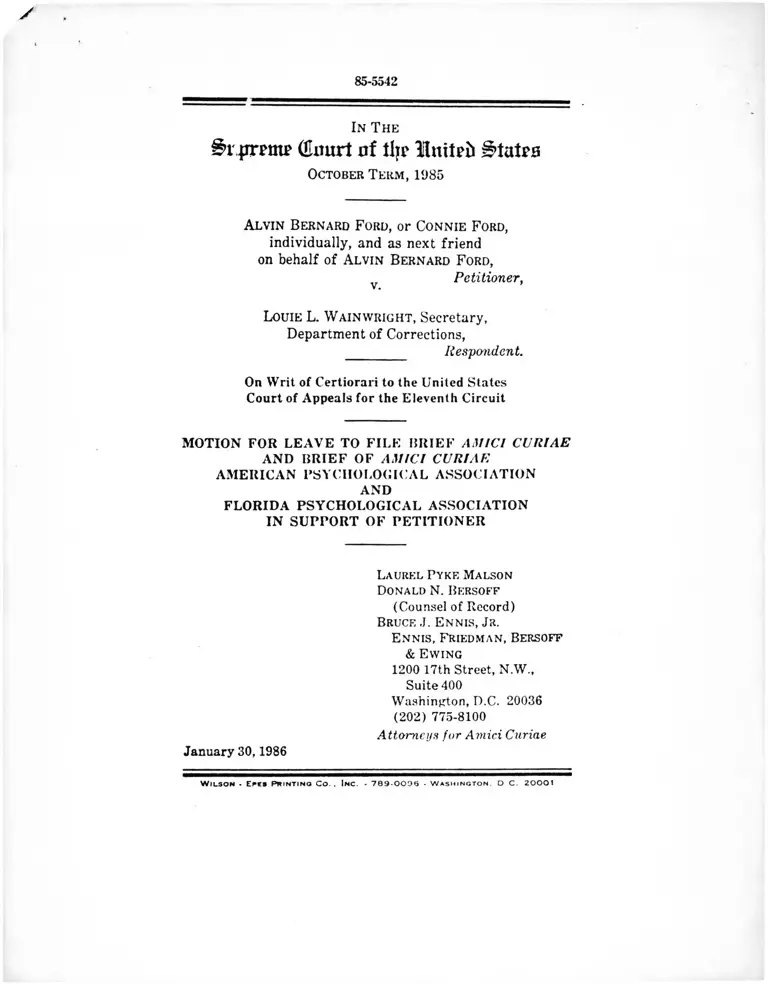

85-5542

In T he

§>i{rmnp (Enurt of Jljr lilmteii States

October Term, 1985

Alvin Bernard Ford, or Connie Ford,

individually, and as next friend

on behalf of Alvin Bernard Ford,

Petitioner,

Louie L. Wainwright, Secretary,

Department of Corrections,

________ Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AM ICI CU RIAE

AND BRIEF OF AM ICI CURIAE

AMERICAN PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

AND

FLORIDA PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER

Laurel Pyke Malson

Donald N. Bersoff

(Counsel of Record)

Bruce J. E n n is , Jr.

E n n is , Friedman , Bersoff

& E wing

1200 17th Street, N.W.,

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 775-8100

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

January 30,1986

W i l s o n • E pks P o i n t i n g C o .. In c . - 7 8 9 -0 0 9 6 - W a s h i n g t o n . D C. 20001

In The

S?uprrmr (Cmtrt nf tljr Huitpti g>tatps

October Term, 1985

85-5542

Alvin Bernard Ford, or Connie Ford,

individually, and as next friend

on behalf of Alvin Bernard Ford,

v Petitioner,

Louie L. Wainwright, Secretary,

Department of Corrections,

________ Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AM ICI CURIAE

AMERICAN PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION AND

FLORIDA PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER

Pursuant to Rule 36.3 of the Rules of this Court, the

American Psychological Association (hereafter “APA” )

and the Florida Psychological Association (hereafter

“FPA” ) move for leave to file the attached brief amici

curiae. Although Petitioner consented to the filing of this

brief, Respondent denied consent, thereby necessitating

the filing of this Motion.

The APA, a nonprofit scientific and professional or

ganization founded in 1892, is the major association of

psychologists in the United States. APA has more than

60,000 members, including the vast majority of psychol

ogists holding doctoral degrees from accredited universi

(i)

11

ties in the United States. The purpose of APA, as set

forth in its bylaws, is to “advance psychology as a science

and profession, and as a means of promoting human wel

fare . . . A substantial number of APA’s members are

concerned with clinical and forensic psychology, including

the collection of data and the development of research,

and engage regularly in the evaluation of the mental con

dition of criminal offenders.

The FPA, with over 700 members, represents the ma

jority of psychologists in Florida and is affiliated for

mally with the APA. The work of FPA’s members en

compasses basic and applied research, teaching, and a

myriad of mental health services to hospitals, courts,

clinics, schools, and the community at large. Many of

Florida’s psychologists offer expert testimony in court

proceedings in which an individual’s mental or emotional

state is an issue. An even larger number are involved in

the study, assessment, and treatment of mental and emo

tional disorders and the effects of such disorders on hu

man behavior and cognitive abilities. In this way, Florida

psychologists, like psychologists nationally, bring unique

qualifications to matters bearing on the case at hand. Be

cause this case originated in Florida, and because Florida

psychologists are committed to the promotion of public

welfare, FPA, representing psychology in Florida, joins

APA as co-amicus.

The APA has participated as amicus in many cases in

this Court involving mental health issues, including

Youngberg v. Romeo, 457 U.S. 307 (1982) (the rights of

mentally retarded residents of state hospitals) ; Mills v.

Rogers, 457 U.S. 291 (1982) (the right of a competent

committed mental patient to refuse psychotropic drugs) ;

City of Akron v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health,

Inc., 4G2 U.S. 41G (1983) (abortion counseling by non

physicians) ; and Akc v. Oklahoma, 105 S. Ct. 1087 (1985)

(indigent defendant’s right to assistance from a mental

health professional). So far this Term, the APA has filed

amicus briefs in Thornburgh v. American College of Ob

stetricians and Gynecologists, No. 84-495; Lockhart v.

McCree, No. 84-1865; and Smith v. Siclaff, No. 85-5487.

APA contributes amicus briefs to this Court only where

the APA has special knowledge to share with the Court.

APA regards this as one of those cases. In this instance,

APA and FPA wish to inform the Court about the

methodologies of psychological evaluations and the need

for and use of expert testimony in post-sentencing com

petency proceedings. APA and FPA believe this impor

tant and relevant information will not be provided by the

parties and will be of assistance to the Court in deciding

this case.

Respectfully submitted,

iii

Laurel P yke Malson

Donald N. Bersoff

(Counsel of Record)

Bruce J. E n n is , J r.

E n n is , F riedman, Bersoff

& E wing

1200 17th Street, N.W.,

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 775-8100

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

January 30, 1986

Pape

TABLE OF CONTENTS

MOTION. FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICI

CURIAE ............................................................................. i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.............................................. vi

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE .......................................... 1

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGU

MENT ...................................................................................... 1

ARGUMENT.............................................................................. 5

I. CONDEMNED PRISONERS OF QUESTION

ABLE MENTAL COMPETENCY MAY NOT

BE EXECUTED WITHOUT FIRST HAV

ING THEIR COMPETENCY DETERMINED

THROUGH AN ACCURATE AND RELIABLE

FACTFINDING PROCEEDING......................... 5

A. Accurate And Reliable Factfinding On The

Issue Of Mental Competency Requires An

Adversary Hearing Where The Issue Of Com

petency Is Disputed........................................... 10

B. Accurate And Reliable Factfinding On The

Issue Of Mental Competency Requires The

Assistance Of Mental Health Professionals

In The Evaluation And Preparation Of All

Issues Relevant To Determining Condemned

Prisoners’ Competency .......... .......................... 13

C. Accurate And Reliable Factfinding On The

Issue Of Mental Competency Requires De

cisionmakers To Specify Tn Writing The

Factors Relied Upon In Making Competency

Determinations .......... ................. 17

II. THE PROCEDURES FOLLOWED BY THE

STATE OF FLORIDA IN EVALUATING PE

TITIONER’S COMPETENCY TO BE EXE

CUTED FAILED TO PROVIDE AN ACCU

RATE AND RELIABLE DETERMINATION

ON THE ISSUE ..................................................... 18

CONCLUSION ...................................................................... 30

(v)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES: Page

Addington v. Texas, 441 U.S. 418 (1979)...............2, 12, 13

Ake v. Oklahoma, 105 S.Ct. 1087 (1985) ................. passim

Arnett v. Kennedy, 416 U.S. 134 (1974)................. 8

Barefoot v. Estelle, 463 U.S. 880 (1983)................. 2

Blue Shield v. McCready, 457 U.S. 465 (1982) ... 2

Board of Regents v. Roth, 408 U.S. 564 (1972).. 10

California v. Ramos, 463 U.S. 992 (1983).............. 4, 6

Caritativo v. California, 357 U.S. 549 (1958)........ 7

Drape v. Missouri, 420 U.S. 162 (1975)................... 4

Eddings v. Oklahoma, 455 U.S. 104 (1982)............ 6

Estelle v. Smith, 451 U.S. 454 (1981)....................... 2

Ford v. Wainwright, 752 F.2d 526 (11th Cir. 1985),

cert, granted, 54 U.S.L.W. 3420 (Dec. 9, 1985).. 7

Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972)..................6, 7, 17

Gardner v. Florida, 430 U.S. 349 (1977).................. passim

Goode v. Wainwright, 448 So.2d 999 (Fla. 1984).... 22

Goss v. Lopez, 419 U.S. 565 (1975) ........................ 10

Greenwood v. United States, 350 U.S. 366 (1956) . 12

Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153 (1976).....................passim

Hays v. Murphy, 663 F.2d 1004 (10th Cir. 1981).... 24

Hidden v. Mutual Life Insurance Co., 217 F.2d

818 (4th Cir. 1954) ................................................. 1

Jenkins v. United States, 307 F.2d 637 (D.C. Cir.

1962) .......................................................................... 1

Lindsey v. State. 254 Ga. 444, 330 S.E. 2d 563

(1985) ......................................................................... 2

Lockett v. Ohio, 438 U.S. 586 (1978) .......................passim

Logan v. Zimmerman Brush Co., 455 U.S. 422

(1982) ........................................................................ 7,8

Mathews v. Eldridge, 424 U.S. 319 (1976).............. 8, 9, 10

O'Connor v. Donaldson, 422 U.S. 563 (1975) ........ 12

Parham v. J.R., 442 U.S. 584 (1979)......................... 2

Pate v. Robinson, 383 U.S. 375 (1966)..................... 4

People v. Hawthorne, 293 Mich. 15, 291 N.VV. 205

(1940) ..................................... 1

Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962) ......... 7

Solesbee v. Balkcom, 339 U.S. 9 (1950) ................ 7, 12

Vitek v. Jones, 445 U.S. 480 (1980) ........................ passim

vi

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

Williams v. New York, 337 U.S. 241 (1949) 23

Wolff v. McDonnell, 418 U.S. 539 (1974) 8

Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S. 280 (1976) passim

Youngbcrg v. Romeo, 457 U.S. 307 (1982) ........... 2

STATU TES AND CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS:

United States Constitution, Amendment VIII .......passim

United States Constitution. Amendment X IV ......... passim

Fla. Stat. § 922.07 (1983) (amended 1985) ......... passim

OTHER AUTHORITIES:

ABA Standards for Criminal Justice (1984) ....... 3

American Bar Association Project on Standards

for Criminal Justice, Sentencing Alternatives

and Procedures, Commentary (App. Draft

1968) ........................................................................... 6

A PA, Specialty Guidelines for the Delivery of

Services bj/ Clinical Psychologists, 36 A m .

Psychol. 640 (1981) ............................................ 25

APA, Standards for Providers of Psychological

Services, 32 A m . Psychol. 495 (1977) ............... 25

A. A nastasi, Psychological Testing (5th ed.

1982) .................................................................................. 28

L. Rellak & L. Loer. T he Schizophrenic S yn

drome (1969) ................................................................. 24

T. Blau. T he Psychologist as E xpert W itness

(1984) ............................................ 1,26

Rluestone& McGahee, Reaction to Extreme Stress:

Impending Death by Execution, 119 A m . J.

Psychiat. 393 (1962) ............................................... 16

Bonnie and Slobogin, The. Role, of Mental Health

Professionals in the Criminal Process: The Case

For Informed Specidation, 66 Va . L. Rev. 427

(1980) .................................................................... 1

Comment, The Psychologist as an Expert Witness,

15 Ka n . L. Rev. 88 (1 9 6 6 ) ......................................... 2

V III

Page

Cooke, An Introduction to Basic Issues and Con

cepts in Forensic Psychology, in T he Role op

the F orensic Psychologist 5 (G. Cooke, ed.

1980) .................................................................... 28

Cooke, The Role of the Psychologist in Criminal

Court Proceedings, in T he Role ok the Foren

sic Psychologist 91 (G. Cooke, ed. 1980)........... 28

L. Cronbach, Essentials of Psychological Test

ing (4th ed. 1984) ...................................................... 28

H. Kaplan , A. Freedman, B. Saddock, A Compre

hensive Textbook Of P sychiatry/III (3d ed.

1980) ..................................................................... 26

Lassen, The Psychologist as an Expert Witness in

Assessing Mental Disease or Defect, 50 A.R.A. J.

239 (1 9 6 4 ) ........................................................................ 1

Levitt, The Psychologist: A Neglected Legal Re

source, 45 Ind . L. J. 82 (1969)............................... 1

Louisell. The Psychologist in Today’s Legal World,

39 Mi n n . L. Rev. 235 (1955) ................................... 1

Nash, Parameters and Distinctiveness of Psycho

logical Testimony, 5 PROF. PSYCHOL. 239 (1974) 2

Note, Psychologist’s Diagnosis Regarding Mental

Disease or Defect Admissible on Issue of In

sanity, 8 V ill. L. Rev. 119 (1 9 6 2 ) ............................ 2

Pacht, Kuehn, Bassett & Nash, The Current Status

of the Psychologist as an Expert. Witness, 4

Prof. Psychol. 409 (1 9 7 3 ) ............................................. 2

Perlin, The Legal Status of the Psychologist in the

Courtroom, in T he Role of the Forensic Psy

chologist 26 (G. Cooke, ed. 1980) ........................ 2

SadolT, Working with the Forensic Psychologist,

in T he Role of T he Forensic Psychologist

106 (G. Cooke, ed. 1980) 28

D. S hapiro, Psychological Evaluation and E x

pert Testimony (1984) 28

Wilson. Prison As An Environment in T he Role

of T he F orensic Psychologist 279 (G. Cooke,

ed. 1980) ...................................................... 25

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

IX

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

J. Zisk in , 2 Coping W ith Psychiatric and Psy

chological Testimony , (3d ed. 1981)................. 24

Ziskin, Giving Expert Testimony: Pitfalls and

Hazards for the Psychologist in Court, in THE

Role Of T he Forensic Psychologist 98 (G.

Cooke, ed. 1980) ............. .................. 24,29

BRIEF OF AM ICI CURIAE

AMERICAN PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

AND

FLORIDA PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

The interest of amici curiae is set out in the attached

Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae, a t pp. i-iii,

supra.

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

This case raises two related issues regarding the extent

to which the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments pro

hibit the execution of condemned prisoners who are pres

ently mentally incompetent, and, assuming such a pro

hibition, the minimum procedural safeguards that must

be observed in determining such individuals’ competency

to be executed. Determination of appropriate procedures

for competency evaluations of condemned prisoners in

volves recognition and understanding of the roles played

by mental health professionals in this context.' Because

1 Throughout this brief, amici use the term “mental health pro

fessional” to refer to professional psychologists, psychiatrists and

other clinicians qualified by law to evaluate and present opinion

testimony on the mental health issues relevant to capital cases.

Expert testimony in this area by psychologists, for example, has

been admissible in most jurisdictions since the 1940s, see Jenkins

v. United States, 307 F.2d 637 (D.C. Cir. 1962) (en banc) ; Hidden

v. Mutual Life Insurance Co., 217 F.2d 818 (4th Cir. 1954) ; and

People v. Hawthorne, 293 Mich. 15, 291 N.W. 205 (1940) ; see

generally T. Blau, T he P sychologist as E xpert W itness (1984);

D. S hapiro, P sychological E valuation and E xpert T estimony

(1984), and has met with almost unanimous endorsement by com

mentators. See Bonnie and Slobogin, The Role of Mental Health

Professionals in the Criminal Process: The Case For Informed Spec

ulation, 66 Va. L. Rev. 427 (1980) ; Lassen, The Psychologist as an

Expert Witness in Assessing Mental Disease or Defect, 50 A.B.A. J.

239 (1964); Levitt, The Psychologist: A Neglected Legal Resource,

45 IND. L. J. 82 (1969) ; Louisell, The Psychologist in Today's Legal

2

of amici’s strong interest and expertise in the various

methodologies for cognitive assessment that are integral

components of all competency evaluations, including those

World, 39 Min n . L. Rev. 235 (1955) ; Nash, Parameters and Distinc

tiveness of Psychological Testimony, 5 P rok. PSYCHOL. 239 (1974) ;

Pacht, Kuehn, Bassett & Nash, The Current Status of the Psycholo

gist as an Expert Witness, 4 PROF. PSYCHOL. 409 (1973); Perlin,

The Legal Status of the Psychologist in the Courtroom, in T he

Role of the F orensic P sychologist 26-36 (G. Cooke, ed. 1980);

Note, Psychologist's Diagnosis Regarding Mental Disease or De

fect Admissible on Issue of Insanity, 8 VlLL. L. Rev. 119 (1962) ;

Comment, The Psychologist as an Expert Witness, 15 Ka n . L. Rev.

88 (1966). For further discussion of this point, see Briefs for

Amicus Curiae American Psychological Association in Smith v.

Sielaff, No. 85-5487; and Ake v. Oklahoma, No. 83-5424.

Although some of the Court’s decisions in cases involving mental

health issues have referred to psychiatrists and not psychologists

or other appropriately trained and licensed mental health profes

sionals, see, e.g., Ake v. Oklahoma, 105 S.Ct. 1087 (1985) ; Barefoot

v. Estelle, 463 U.S. 880 (1983) ; Estelle v. Smith, 451 U.S. 454

(1981) ; and Parham v. J.R., 442 U.S. 584 (1979), other decisions

properly have recognized that psychologists stand on an equal foot

ing with psychiatrists. See, e.g., Youngberg v. Romeo, 457 U.S.

307, 323 n.30 (1982) (“professional decisionmaker’’ includes persons

with “appropriate training” in “psychology”) ; Blue Shield v.

McCready, 457 U.S. 465 (1982) (health plan subscriber denied

reimbursement for psychologist’s fees has standing to sue for con

spiracy to exclude psychologists from psychotherapy market); Vitek

v. Jones, 445 U.S. 480, 491 (1980) (“ [the state]’s reliance on the

opinion of a designated physician or psychologist . . . .”) ; and

Addington v. Texas, 441 U.S. 418, 429 (1979) (". . . which must

be interpreted by expert psychiatrists and psychologists”). Amici

assume that holdings referring solely to psychiatrists were not in

tended to imply that rules deemed appropriate in those cases

for psychiatrists would be inappropriate for psychologists or other

appropriately trained and licensed mental health professionals.

However, these ambiguities have led lower courts to read Ake

and analogous cases too narrowly. See, e.g., Lindsey v. State, 254

Ga. 444, 330 S.E. 2d 563 (1985) (Ake not satisfied by providing

defense with access to examination by a mental health expert other

than a psychiatrist). To dispel any confusion that these ambiguities

may have engendered among lawyers and judges on this point,

amici urge the Court to use a more neutral and descriptive phrase

such as “mental health professional.” This phrase has been adopted

3

provided under Florida law,'* * amici believe that their views

regarding this latter issue will be useful to the Court’s

deliberations.

Although amici do not address in this brief the question

whether States are prohibited by the Eighth Amendment’s

prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment, or by

the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment,

from carrying out the death penalty against individuals

who are presently incompetent, for the purpose of present

ing their argument, amici will assume that, whether as a

substantive constitutional right or as an interest entitled

to federal due process protections, Florida constitutionally

may not execute mentally incompetent individuals.'1

Under either the enhanced reliability standard for

imposing capital punishment under the Eighth Amend

ment or the procedural due process standards of the Four

teenth Amendment, the procedures followed by the State

of Florida in evaluating Petitioner’s competency to be

by the American Bar Association, on the recommendation of an

interdisciplinary task force composed of lawyers, psychologists, psy

chiatrists and other mental health professionals, including formal

representatives of the American Psychological Association and the

American Psychiatric Association, in its recently adopted Criminal

Justice Mental Health Standards. See ARA Standards for Criminal

Justice ( lSS-C), Standard 7-1.1 et seq.

- Fla. Stat. § 922.07(2') provides that a condemned prisoner is in

competent to be executed upon a determination by the Governor,

after professional examination of the prisoner, that the prisoner

lacks “the mental capacity to understand the nature of the death

penalty and the reasons why it was imposed upon him." This test

requires the assessment of primarily cognitive abilities.

* Amici's decision not to address the question whether Petitioner

has a constitutional right not to he executed while mentally incom

petent reflects only their judgment that, in light of their special

expertise, amici's views would be most useful to the Court’s de

liberations on the issues addressed herein. Nevertheless, amici

believe that the arguments presented to the Court by Petitioner’s

counsel on the underlying constitutional issues are soundly based

in the prior holdings of the Court.

4

executed were inadequate. Although Petitioner docs not

now challenge the validity of his conviction and sentenc

ing, because of the consistent recognition by this Court of

the “qualitative difference” between the penalty of death

and other punishments, California v. Ramos, 4(13 U.S.

992, 998 (1983); Lockett v. Ohio, 438 U.S. .r)8(l. 004

(1978) (opinion of Burger, C.J.) ; Woodson v. North

Carolina, 428 U.S. 280, 305 (1976) (plurality opinion),

the requirement that procedural safeguards be observed

to ensure accuracy and reliability in the guilt and sen

tencing phases of capital proceedings should be extended

to proceedings in the post-sentencing phase in which com

petency for execution is evaluated.4 5

Because of the critical role that adversarial debate

plays in the “truth-seeking” process, Gardner v. Florida,

430 U.S. 349, 360 (1977) (plurality opinion), amici urge

this Court, whenever there is reasonable cause to believe

that a condemned prisoner lacks the mental competency

to be executed, and there is a factual dispute as to that

issue, to require a full and fair adversarial hearing on the

issue of his or her competency." Amici further urge the

Court’s recognition, as a requirement of due process, of

the effective assistance of mental health professionals,

and the appointment of such professionals in the case of

indigents, to conduct appropriate examinations of con

demned prisoners and to assist them and their attorneys

in evaluating and preparing all issues relevant to the

accurate determination of their present competency to

4 See also Gardner r. Florida, 430 U.S. 349, 357 (1977) (plurality

opinion) (and cases cited therein). See tjrnernlly Alee v. Oklahoma,

105 S.Ct. 1087, 1099 (1985) (Burger, C. J., concurring).

5 Because the constitutional right not to be executed while in

competent is no less important than the right not to be tried while

incompetent, the threshold inquiry for requiring a hearing on a

condemned prisoner’s competency to be executed should be whether

there is “reasonable cause” to question, or “sufficient doubt” as to,

the prisoner’s competency. See generally Drope v. Missouri, 420

U.S. 162, 173, 180 (1975) ; Pate v. Robinson, 383 U.S. 375 (1966).

be executed. Finally, amici urge the Court to require

written statements by decisionmakers specifying the facts

relied upon in determining a condemned prisoner’s com

petency to be executed, to ensure that proper procedural

and substantive standards are observed by the State in

competency proceedings. The procedures provided by Fla-

Stat. S 922.07 for determining the competency of con

demned prisoners failed in all of these respects to pro

vide Petitioner adequate protection of his constitutional

right not to be executed at this time.

Apart from the general right of condemned prisoners

in Petitioner’s circumstances to the assistance of a men

tal health professional, the mental status examination of

Petitioner which was conducted by the psychiatrists ap

pointed by the Governor pursuant to Fla. Stat. 5 922.07

failed to meet the relevant professional standards of

mental health professionals engaged in forensically-ori-

ented clinical evaluations.

As a result of these procedural inadequacies and pro

fessional deficiencies, the determination that Petitioner

is competent to be executed fails the enhanced reliability

and heightened procedural fairness standards of the

Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments.

ARGUMENT

I. CONDEMNED PRISONERS OF QUESTIONABLE

MENTAL COMPETENCY MAY NOT BE EXE

CUTED WITHOUT FIRST HAVING THEIR COM

PETENCY DETERMINED THROUGH AN ACCU

RATE AND RELIABLE FACTFINDING PROCEED

ING.

The question presented by this case is whether the

constitutional requirement that adequate procedural safe

guards be observed to ensure accurate and reliable deter

minations in the guilt and sentencing phases of capital

punishment should be extended to proceedings whore

the State determines a condemned prisoner’s competency

6

to proceed with the execution. This Court has recognized

consistently the special nature of capital cases and has

construed the Constitution to require adherence to the

highest standards of procedural fairness in imposing the

death penalty. Because the death penalty is “unique in

its severity and irrevocability,” and because of the fun

damental nature of the individual interest that is at stake

in death penalty proceedings, the Court has imposed pro

cedural standards designed to minimize the possibility of

erroneous determinations in such proceedings. Gregg v.

Georgia, 428 U.S. 153, 187 (19761 (plurality opinion),

citing Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238, 286-91, 306

(19721 (concurring opinions of Brennan and Stewart,

J J .l . See, e.g., Ake v. Oklahoma, 105 S.Ct. 1087, 1099

(19851 (Burger, C.J., concurring in judgmentl ; Lockett

v. Ohio, 438 U.S. at 604; Gardner v. Florida, 430 U.S.

at 357; Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S. at 305.

These standards require individualized consideration of

all factors relevant to the determination to impose capital

punishment as a means of ensuring that “the death pen

alty is not meted out arbitrarily or capriciously,” but

rather in a consistent and reasoned manner. California

v. Ramos, 463 U.S. at 992; Lockett v. Ohio, 438 U.S. at

601; Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. at 188-89." The Court

has required further that adequate procedural safeguards

be followed in capital proceedings to ensure the accuracy 6

6 Because “the imposition of death by public authority is so

profoundly different from all other penalties, . . .” Lockett v. Ohio,

438 U.S. at 605 (Burger. C. J.) (emphasis added), individuals sub

ject to capital punishment must be permitted to present any mitigat

ing evidence that is relevant to the decisionmaker’s determination of

the appropriateness of capital punishment in their particular cases,

and such evidence must be considered by the decisionmaker. Wood-

son v. Worth Carolina, 428 U.S. at 304. Sie Eddings v. Oklahoma,

455 U.S. 104 (1982). Without informed decisionmaking, “ ‘the sys

tem cannot function in a consistent and rational manner.’ ’’ Gregg v.

Georgia, 428 U.S. at 189, quoting the American Bar Association

Project on Standards for Criminal Justice, Sentencing Alternatives

and Procedures § 4.1(a), Commentary, p. 201 (App. Draft 1968).

7

of the information used by decisionmakers and the reli

ability of the determination that “death is the appropri

ate punishment in a specific case.” Woodson v. North

Carolina, 428 U.S. at 304, 305.

Although the Court has not had occasion to address the

specific applicability of these procedural requirements to

post-sentencing competency proceedings in light of con

temporary Eighth and Fourteenth Amendment stand

ards, the constitutional values of consistent, reasoned

determinations and enhanced reliability in imposing cap

ital punishment are no less compelling in the context of

post-sentencing competency determinations." Chief Jus- 7 8

7 The court of appeals’ reliance on Solesbee v. Balkcom, 330 U.S.

9 (1950), and Caritativo v. California, 357 U.S. 549 (1958), is

misplaced. See Ford v. Wainwright, 752 F.2d 526, 528 (11th Cir.

1985). Because these decisions predate significant developments in

Eighth and Fourteenth Amendment jurisprudence, their applica

bility in the context of this case is severely limited. First,

Solesbee and Caritativo did not purport to consider whether the

Constitution imposed any substantive prohibitions on the execu

tion by States of mentally incompetent prisoners because the Eighth

Amendments prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment

was not applicable to the State until 1962. See Robinson v. Cali

fornia, 370 U.S. 660 (1962). Second, although Solesbee and

Caritativo did address the procedural issue of what process was due

in these circumstances, the requirements of enhanced reliability and

consistent, reasoned decisionmaking in capital sentencing imposed

by this Court in Furman in 1972 and its progeny has rendered im

permissible under the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments many

sentencing practices that were approved previously under the Due

Process Clause. See Lockett r. Ohio. 438 U.S. at 599; Gregg v.

Georgia, 428 U.S. at 195-96 n.47. Third, Solesbee and Caritativo

were decided before this Court accorded state-created “objective

expectation [s'!” the procedural protections of the Due Process

Clause. Vitek v. Jones, 445 U.S. 480, 489 (1980). See Logan v.

Zimmerman Brush Co., 455 U.S. 422 (1982) (and cases cited

therein).

8 In addition to the constitutional values underlying the right

not to be executed while mentally incompetent, there are several

bases, recognized historically at common law, for prohibiting the

execution of mentally incompetent prisoners. Sec gent rail;/ Ford v.

Wainu-right, 752 F.2d at 531 (Clark, dissenting).

tice Burger’s observation in Lockett v. Ohio regarding

capital sentencing is even more apt with respect to post-

sentencing capital determinations: “The nonavailability

of corrective or modifying mechanisms with respect to an

executed capital sentence underscores the need for indi

vidualized consideration [and accurate factfinding | as a

constitutional requirement [in these proceedings].” 438

U.S. at 605 (emphasis added).

Assuming the Court recognizes in this case a constitu

tional right not to be executed while incompetent, “ ‘the

determination of [prisoners’ competency to be executed]

is critical, and the minimum requirements of procedural

due process appropriate for the circumstances must be

observed.’ ” Vitek v. Jones, 445 U.S. 480, 491 (1980),

quoting Wolff v. McDonnell, 418 U.S. 539, 558 (1974).'

This Court consistently has recognized that “ ‘the ade

quacy of statutory procedures for deprivation of a statu

torily created (life, liberty or] property interest must

be analyzed in [federal] constitutional terms.’ ” 445

U.S. at 490-91, n.6, quoting Arnett v. Kennedy, 416 U.S.

134. 167 11974) (Powell, J., concurring in part) (and

cases cited therein). See also Logan v. Zimmerman Brush

Co., 455 U.S. 422, 432 (1982). Balancing the factors set

forth in Mathews v. Eld ridge, 424 U.S. 319, 335 (1976),

as critical to the determination of what process is due, it

is clear that federal due process demands as heightened *

0 Even where the entitlement is based on a state-ereated right

rather than a substantive federal constitutional right, the minimum

due process requirements are “a matter of federal law [and| are

not diminished by the fact that the State may have specified its

own procedures that it may deem adequate for determining the

preconditions to adverse official action.” 115 U.S. at 491. Nor

does the fact that certain determinations are primarily medical or

psychological in nature, and that States rely ‘‘on the opinion f s | of

. . . designated physician[s| or psychologist[s] for determining

whether the conditions warranting [deprivation of a protected in

terest] exist],] . . . remove]] the prisoner’s interest from due

process protection] ] or answer]] the question of what process is

due under the Constitution.” hi.

8

9

procedural protections in determining present eligibility

for the death penalty as are required in the initial guilt

and sentencing phases of capital proceedings.10

Those protections include the opportunity to review and

challenge the accuracy of information upon which the

sentencing authority relies in imposing capital punish

ment, see Gardner v. Florida, 430 U.S. 349 (1977) ; the

assistance of a competent mental health professional, and

appointment of such a professional for indigents, “ in

[the] evaluation, preparation, and presentation of” all

issues relevant to the defense, Ake v. Oklahoma, 105

U.S. at 1097; and a written statement by the sentencing

authority of the evidence relied on and the reasons for

the imposition of capital punishment, to ensure adherence

to proper substantive and procedural standards. See

Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. at 195. These measures,

which seek to ensure consistency and reliability in the

imposition of capital punishment, are “a constitutionally

indispensable part of the process of inflicting the penalty

of death,” Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S. at 304,

including the actual execution of the death sentence. The

absence of these safeguards in the State’s determination

of competency to be executed creates a constitutionally

intolerable risk of erroneous deprivation of life.

10 The three factors identified by the Court as relevant to the

determination of what process is due before an individual may be

deprived by governmental action of a protected life, liberty or

property interest are: 1) the private interest that will be affected

by the governmental action; 2) the governmental interest that will

be affected if the proposed safeguard is provided; and 3) “the

probable value of the additional . . . procedural safeguards that are

sought, and the risk of an erroneous deprivation of the affected

interest if those safeguards are not provided.” Ake i>. Oklahoma,

105 S.Ct. at 1004. Sec Mathews v. L'ldriclye, 424 U.S. at 335.

10

A. Accurate And Reliable Factfinding On The Issue

Of Mental Competency Requires An Adversary

Hearing Where The Issue Of Competency Is Dis

puted.

The Due Process Clause requires that before individ

uals are finally deprived of a constitutionally protected

interest, they must be provided “some form of hearing”

in which to present their case and have its merits fairly

judged. Board of Regents v. Roth, 408 U.S. a t 570-71,

n.8. The nature of the required hearing, however, “will

depend on appropriate accommodation of the competing

interests involved.” Goss v. Lopez, 419 U.S. 565, 579

(1975). Weighing, under Matheios, the private and gov

ernmental interests at stake in light of the probable con

tribution that adversary hearings will make to the con

sistency and reliability of competency determinations,

the balance tips overwhelmingly in favor of providing

condemned prisoners a meaningful opportunity to review

and challenge the factual bases of the State’s determina

tions regarding their mental status.

It cannot reasonably be disputed that “ |t]he private

interest in the accuracy of a . . . proceeding that places

an individual’s life . . . at risk is almost uniquely com

pelling.” Ake v. Oklahoma, 105 S. Ct. at 1094. Although

condemned prisoners may have forfeited some constitu

tional protections by virtue of having been duly convicted

and sentenced to death, assuming the execution of incom

petent prisoners is forbidden under federal or state law,

such prisoners must be considered to possess a “residuum”

of “life” interest so long as they are incompetent. Thus,

condemned prisoners of questionable competency retain a

powerful interest in the reasoned determination, based on

reliable factfinding, of their competency to be executed.

Likewise, the State has a compelling interest in en

suring the accuracy and reliability of competency pro

ceedings. Indeed, the State’s interest in assuring that

its “ultimate sanction” is not erroneously carried out is

“profound.” Id. at 1097. The State has additional in

11

terests in the deterrent and retributive values of enforc

ing sanctions that have been lawfully imposed by its

criminal process, unimpeded by delays and additional ad

ministrative or financial burdens. However, unlike a pri

vate adversary, the State must temper its interest in effi

cient enforcement of the death penalty with its larger

interest in preserving the constitutional integrity of its

criminal justice system. Id. at 1095.

The safeguard of an adversary hearing, in which pris

oners are permitted to review and challenge evidence of

their competency that is adduced by the State, enhances

substantially the likelihood of accurate determinations of

competency. Sec, e.tj., Vitek v. Jones, 445 U.S. 480

(1980); Gardner v. Florida, 430 U.S. 349 (1977). Al

though providing condemned prisoners with such an op

portunity may cause delays in the administration of their

ultimate punishment, those costs are clearly outweighed

by the benefits of allowing the adversary process to

sharpen and refine the evidentiary bases on which de

terminations are made to carry out “this most irrevocable

of sanctions.” Grcytj v. Georgia, 428 U.S. at 182.

In Gardner v. Florida, the Court held that the Due

Process Clause required an opportunity for adversarial

debate on “confidential” presentence reports on which

the State intended to rely in a capital sentencing pro

ceeding. Regarding the State’s interest in avoiding de

lay, the Court stated that delay could be avoided if the

decisionmaker disregarded any material in the report

which was contested by the defendant. If, however, the

contested material was “of critical importance [and

therefore would be used by the decisionmaker in sentenc

ing the defendant], the time invested in ascertaining the

truth would surely be well spent if it makes the differ

ence between life and death.” Id. at 359-60.

Similarly, the Court cautioned that “consideration

must be given to the quality, as well as the quantity, of

the information on which the fdecisionmaker | may rely”

in imposing the death penalty. Id. at 359. Information

12

that has not been subjected to the “truth-seeking func

tion” of the adversary process is inherently less reliable

than information that has been so tested. This is par

ticularly true with mental health assessments. As the

Court has noted, mental health professionals “disagree

widely and frequently on what constitutes mental illness

[and] on the appropriate diagnosis to be attached to

given behavior symptoms. . . .” Ake v. Oklahoma, 105

S.Ct. at 1096. The same uncertainties in mental health

assessments that the Court has noted in the contexts of

civil commitment, the insanity defense and incompetence

to stand t r ia l11 are equally applicable in the context of

determinations of competency to be executed. Indeed,

because questions of competency in this context arise only

after the individual has already been determined to have

been competent to stand trial, and not insane at the time

of the offense, the symptoms of mental disorder at this

stage can be particularly “elusive and often deceptive,”

and therefore difficult to assess. Solesbee v. Balkcom, 339

U.S. 9, 12 (1950). Thus, allowing condemned prisoners

whose competency is questionable to call witnesses, cross-

examine the State’s mental health experts, and present

arguments and mental health experts on their own behalf

is especially necessary to reduce to a constitutionally

tolerable level the risk of erroneous deprivation of life.

Even where the private interest at stake is less than

life, the Court has rejected deprivation by the State of

an individual’s constitutionally-protected interest in the

absence of an adversary hearing. In Vitek v. Jones, 445

U.S. 480 (1980), the Court held that a prisoner’s liberty

interest was violated by his classification as mentally ill

and involuntary transfer to a mental hospital for psy

chiatric treatment without adequate procedural protec

tions. Although recognizing the State’s “strong” interest

11 See generally, Addington v. Texas, 441 U.S. 418, 429-30 (107!)) ;

O'Connor v. Donaldson, 422 U.S. 563 (1075) ; Crecnirood u. United

States, 350 U.S. 366, 375-76 (1056) ; Solesbee v. Balkcom, 330 U.S.

9 (1950).

in segregating and treating mentally ill patients, the

Court found the prisoner's state-created interest in not

being “arbitrarily classified as mentally ill and subjected

to unwanted treatment . . . powerful.” Id. at 495. These

and other considerations, including the substantial risk

of error in making the required mental health assess

ments under the statute, led the Court to require ade

quate procedural safeguards in making these deter

minations.12 Recognizing that the inquiry in Vitek was

essentially medical . . . ‘turnfing] on the meaning of

the facts which must be interpreted by expert psychia

trists and psychologists,’ ” the Court stated that “ ft]he

medical nature of the inquiry, however, [did] not justify

dispensing with due process requirements.” 445 U.S. at

495, quoting Addington v. Texas, 441 U.S. 418, 429

(1979). Rather, “ [i]t is precisely [6ccazi.se ofj ‘[t]he

subtleties and nuances of psychiatric diagnoses' that . . .

adversary hearings [are required].” Id., quoting 441

U.S. at 430 (emphasis added).

B. Accurate And Reliable Factfinding On The Issue

Of Mental Competency Requires The Assistance Of

Mental Health Professionals In The Evaluation And

Preparation Of AH Issues Relevant To Determining

Condemned Prisoners’ Competency.

A ruling that due process requires access to competent

mental health professionals to examine and meaningfully

assist prisoners during competency hearings is an appro

priate accommodation of the competing interests of the

State and condemned prisoners. This requirement nec

essarily includes the appointment of mental health pro

fessionals to assist indigent condemned prisoners of ques

tionable competency. See Ake v. Oklahoma, 105 S.Ct.

‘-The procedural safeguards included, inter alia, a hearing at

which: the State is required to disclose the evidence on which it

intends to rely; prisoners are given an opportunity to be heard in

person and to present contrary documentary evidence; and prisoners

are provided an opportunity to present testimony by their own

witnesses and to confront and cross-examine witnesses called by

the State.

13

14

1087 (1985). Both the State ami condemned prisoners

have a very substantial interest in the fair and accurate

adjudication of condemned prisoners’ competency to be

executed. The State has additional interests, however, in

avoiding the financial and administrative burdens that

providing condemned prisoners with the assistance of

mental health professionals would impose on its crimi

nal justice system. However, in light of the compelling

interests of both the State and the individual in accurate

dispositions, it is clear that those governmental interests

are “not substantial.” Ake v. Oklahoma, 105 S.Ct. at

1095.

Balancing these private and governmental interests in

light of “the probable value of [the assistance of a men

tal health professional], and the risk of erroneous depri

vation of the [prisoner’s life] if [such a safeguard] is

not provided,” the weight favors providing the assistance

of independent mental health professionals to prisoners of

questionable competency. Ake v. Oklahoma, 105 S.Ct. at

1094. Providing such prisoners with independent mental

health professionals who will conduct appropriate exami

nations. challenge the findings of State experts, and pro

vide other relevant assistance will contribute to the ad

versarial debate and thereby enhance the decisionmaker's

ability to make a reliable and informed determination.

In 4̂Are, the Court, recognizing the “pivotal role” that

mental health professionals have come to play in criminal

proceedings, acknowledged that when “the defendant’s

mental condition [is] relevant to . . . the punishment he

might suffer, the assistance of a [mental health profes

sional] may well be crucial to the defendant’s ability to

marshal his defense.” 105 S.Ct. at 1095. In such cases,

because “the risk of inaccurate resolution of sanity issues

[would be] extremely high” without such assistance, fail-

adjudication at the guilt and sentencing phases of capi

tal cases requires, “at a minimum, [that the State] as

sure the defendant access to a competent [mental health

professional] who will conduct an appropriate examina

15

tion and assist in the evaluation, preparation, and pre

sentation of the defense.” Id. a t 1097.

As in the guilt and sentencing phases of criminal pro

ceedings, when a condemned prisoner’s mental condition

is relevant to the determination whether to proceed with

a death sentence, the assistance of a mental health pro

fessional becomes critical to the fair and accurate deter

mination of the prisoner’s competency to be executed. A

mental health professional retained or appointed to assist

the prisoner will be able to examine the prisoner and

conduct relevant tests over the period of time necessary

to produce an accurate mental assessment, will provide

the trusting relationship necessary to evoke the candid

and spontaneous disclosures upon which accurate assess

ment depends, and will provide meaningful assistance to

the prisoner and counsel in reviewing and responding to

the reports of the State’s mental examiners.1'1

The client-clinician relationship is particularly impor

tant in this context because the symptoms of psychological

distress caused by the imminence of one’s execution may

not always manifest themselves in obviously aberrational

behavior. In addition, because the psychological stress

that accompanies living under a sentence of death can

cause condemned prisoners to develop defensive mecha

nisms to cope with the stress, the mental health profes

sional must be sensitive to the degrading nature of the

forces—and their physical, psychological, and emotional

impact—that uniquely press upon prisoners awaiting ex-

u Although Petitioner was evaluated by two mental health

professionals, the reports of those evaluations were neither sub

mitted to the Governor, nor referred to in the state-appointed

psychiatrists’ reports to the Governor, for hi3 consideration in de

termining Petitioner’s competency to be executed. Moreover, the

absence of an adversarial proceeding precluded any meaningful

assistance to Petitioner by these professionals, e.g., helping to pre

pare the cross-examination of the State psychiatrists, giving testi

mony on behalf of Petitioner.

edition.™ To assess fully the effects that these defensive

mechanisms have on a condemned prisoner’s rational and

factual understanding of his or her fate, i.e., competency

to be executed, the mental health professional must pos

sess the time and the skill essential to developing a re

lationship with the prisoner that will provide the neces

sary access to the prisoner’s psychological composition.

The provision of such assistance to prisoners of ques

tionable competency will enhance significantly the likeli

hood of an accurate determination of the prisoner’s com

petency to be executed: “By organizing [the prisoner’s]

mental history, examination results and behavior, and

other information, interpreting it in light of their ex

pertise, and then laying out their investigative and

analytic process to the [decisionmaker], [mental health

professionals] for each party enable the [decisionmaker]

to make its most accurate determination of the truth of

the issue before [it].” .4A:e v. Oklahoma, 105 S.Ct. at

1096.* 13 * 15

Thus, a proper balancing of interests, “where the con

sequence of error is so groat, the relevance of responsive

psychiatric testimony so evident, and the burden on the

State so slim, . . . requires access to a [mentall examina

tion on relevant issues, to the testimony of the [mental

health professional], and to assistance in preparation at

the [post-sentencing competency evaluation] phase.” Id.

at 1097.

16

14 For example, a common reaction to the extreme anxiety and

stark terror that many prisoners experience when confronted with

the imminence of their death is the suppression of that reality by a

variety of psychological defense mechanisms, including denial by

delusion formation, denial by minimizing their predicament, projec

tion, and obsessive preoccupation with religious, intellectual or philo

sophical matters. See generally Rluestone & McGahee, Reaction to

Extreme Stress: Impending Death by Execution, 119 Am . J.

PsycHIAT. 393 (1962).

13 This is especially true given the frequency and breadth of

disagreement that may obtain in mental evaluations of the same

individual. See p. 12, supra.

C. Accurate And Reliable Factfinding On The Issue Of

Mental Competency Requires Decisionmakers To

Specify In Writing The Factors Relied Upon In

Making Competency Determinations.

The requirement that decisionmakers in capital cases

specify in writing the factors relied upon in reaching

their decision to impose capital punishment has been

recognized by the Court as necessary “to ensure that

death sentences are not imposed capriciously or in a

freakish manner.” Cretin v. Georgia, 428 U.S. at 195.1,1

The l equii ement of written findings forces decision

makers to focus more closely on the reasons underlying

their decisions, and thereby enhances the likelihood of

compliance with the required standards for imposing or

proceeding with capital punishment.1' Written findings

also provide an adequate basis for a collateral chal

lenge to the constitutionality of competency proceedings,

as well as for meaningful appellate review in those juris

dictions where such review is provided. In this way, the

requirement of a written record satisfies the require

ments of reasoned, consistent decisionmaking and en

hanced reliability which have been articulated by this

Court as the touchstones of constitutionally adequate de

cisionmaking in capital cases.

These protections are no less critical when the interests

of condemned prisoners are balanced against those of the 16 17

16 Even in the noncapital context, the Court has recognized in

certain circumstances that the proper balancing of individual inter

ests and governmental interests demands a “written statement by

the factfinder as to the evidence relied on and the reasons for [ the

deprivation of the individual's protected interests 1 Vitek v. Jones,

445 U.S. at 495.

17 See also Gardner v. Florida. 430 U.S. at 361 (“[ l i t is important

that the record . . . disclose . . . the considerations which motivated

the death sentence in every case in which it is imposed. Without

full disclosure of the basis for the death sentence, the Florida capital

sentencing procedure would be subject to the defects which resulted

in the holding of unconstitutionality in Furman v. Georgia.")

(footnote omitted).

17

18

State. Both the State and the questionably competent

prisoners whose lives are at stake have a “compelling

interest” in the accurate and reliable assessment of the

prisoners’ mental competency. Ake v. Oklahoma, 105

S.Ct. a t 1095. The State’s additional interests in finan

cial and administrative economy are taxed only incre

mentally by requiring the decisionmaker to provide a

written statement of the evidence relied on in deter

mining the prisoner’s competency. Indeed, the absence

of such a statement, should the prisoner challenge the

constitutionality of the State’s determination in col

lateral or appellate proceedings, could require the State

to bear the expense of an additional fact-finding hear

ing. Thus, on balance, due process requires that decision

makers support their determinations that condemned

prisoners of questionable competency are fully competent

to be executed with written statements of their findings

of fact.

II. THE PROCEDURES FOLLOWED HY THE STATE

OF FLORIDA IN EVALUATING PETITIONER’S

COMPETENCY TO BE EXECUTED FAILED TO

PROVIDE AN ACCURATE AND RELIABLE DE

TERMINATION ON THE ISSUE.

Pursuant to Fla. Stat. § 922.07, “ [wlhen the Governor

is informed that a person under sentence of death may

be insane, he shall stay execution of the sentence and

appoint a commission of three psychiatrists to examine

the convicted person.” $ 922.07(1). The Governor is re

quired under the statute to instruct the examiners in

writing “to determine whether [the condemned person]

understands the nature and effect of the death penalty

and why it is to be imposed upon him.” Id. If, after re

ceiving the reports from the commission, the Governor

determines that the convicted person “has the mental

capacity to understand the nature of the death penalty

and the reasons why it was imposed upon him, he shall

issue a w’arrant to the warden directing him to execute

the sentence at a time designated in the w arrant.”

§ 922.07(2).

19

Following these procedures, on October 20, 1983, Peti

tioner’s counsel advised the Governor that Petitioner’s

mental condition had deteriorated to the point where his

sanity was questionable, and sought the appointment of

a commission of psychiatrists.18 Three psychiatrists were

appointed and, on December 19, 1983, as provided by

statute, they examined Petitioner “with all three psychi

atrists present at the same time [along with Petitioner’s]

[cjounsel . . . and the state attorney . . . $ 922.07(1).

The “examination” consisted of a one-half hour inter

view with Petitioner in the prison courtroom,1” conversa

tions with the prison’s medical and correctional staff, in

spection of Petitioner’s cell, and, in some cases, review

of materials provided by Petitioner’s counsel20 which con-

18 Petitioner had been examined by a psychiatrist in July, 1981

in connection with unsuccessful clemency proceedings. Because of

the deterioration of Petitioner’s mental state. Petitioner’s counsel

arranged for Petitioner to continue seeing that psychiatrist on a

therapeutic basis. Appendix to Petition for Certiorari (hereafter

“App.”) at 94a. In August, 1982, Petitioner discontinued therapy

because he believed the psychiatrist was conspiring against him in

concert with the Ku Klux Klan. Id. In January, 198.'$, because

Petitioner wanted to dismiss his appeals and submit to execution.

Petitioner's counsel sought evaluation of Petitioner’s mental condi

tion by a second psychiatrist in order to assess Petitioner’s com

petency to make such a decision. Id. at 97a. Petitioner refused to

see this psychiatrist—and anyone else, including family and coun

sel—until November, 1983. Id.

19 Also present during the interview were “one or two correctional

officers’’ and two paralegals. Petition for Writ of Certiorari at 37.

20 Although Petitioner’s counsel provided these materials to the

commission psychiatrists as background information prior to their

interview, whether, and to what extent, these materials were

actually reviewed by the psychiatrists is unclear. Two of the three

commission members stated in their reports that they had reviewed

the materials, but their reports did not even address, much less

account for, the pervasive evidence in those materials of Petitioner’s

delusional processes. See App. 160a-l(iGa. The third psychiatrist

refused to accept the materials until after the interview, and one day

before he submitted his report to the Governor. He made no refer

ence in his report to having reviewed the materials. See id. at

160-62a.

tained portions of the trial transcript, copies of Petition

er's correspondence, reports of two earlier psychiatric

exams, and Petitioner’s medical history. Included in the

reports of the two prior examiners, both of whom ex

amined him over a significantly longer period than the

commission psychiatrists and one of whom had been

Petitioner’s treating therapist, were the following ob

servations: “ [Petitioner’s] mental disorder is severe

enough to substantially affect [his] present ability to

assist in the defense of his life[ ; ] ” “ [Petitioner’s] psy

chotic disorder [is] so severe that it suicidally compels

him to embrace his own death[ ; ] ” and “ [Petitioner] lacks

the mental capacity to understand the reasons why [the

death penalty] is being imposed on him.” App. at 155a,

158a.-1

20

31 See n.18, supra. The first psychiatrist, Petitioner’s treating

therapist, concluded, based on: 1) four in-person evaluations be

tween July, 1981 and August, 1982; 2) taped conversations and

letters between Petitioner and his family, friends and attorneys;

3) interviews with other individuals having had direct observa

tions of Petitioner’s behavior during that period; 4) psychological

and psychiatric evaluations by the prison mental health stall; and

5) prison medical records, that Petitioner suffers from:

a severe, uncontrollable, mental disease which closely re

sembles “Paranoid Schizophrenia With Suicidal Potential”.

This major mental disorder is severe enough to substantially

affect Mr. Ford’s present ability to assist in the defense of his

life.

It should be noted that Mr. Ford's ambivalence around whether

to continue his legal fight is in and of itself an indication of a

psychotic disorder so severe that it suicidally compels him to

embrace his own death.

App. at 155a.

The second psychiatrist concluded after a three-hour interview

that Petitioner suffers from “schizophrenia, undifferentiated type,

acute and chronic,” as a result of which,

while he does understand the nature of the death penalty, he

lacks the mental capacity to urulerstand the reasons why it is

being imposed on him. His ability to reason is occluded, dis

organized and confused when thinking about his possible execu

tion. He can make no connection between the homicide he com-

21

After their examination, notwithstanding the prior

evaluations of Petitioner, all three psychiatrists reported

to the Governor that although Petitioner suffered from

a “severe adaptational disorder,” - “psychosis with para

noia,” 23 or “serious emotional problems . . . [so] pro

found [] . . . it forces Tone] to put a ‘psychotic’ label

on [Petitioner],” 24 he “ha[d] enough cognitive function

ing” to satisfy Florida’s competency standard.25 On April

30, 1984, without any further proceedings, the Governor

signed Petitioner’s death warrant.

Measured against the constitutionally-mandated stand

ard in capital cases of enhanced reliability and consist

ent, reasoned determinations, the procedures by which

Petitioner’s competency was evaluated were grossly inade

quate. First, although § 922.07 (1) authorizes the ap

pointment of counsel to “represent” condemned prisoners

during competency evaluations, there is no provision in

the statute for adversary participation by prisoners’

mittrd and the death penalty. Even when I pointed this con

nection out to him he laughed derisively at me. He sincerely

believes that he is not going to be executed because he owns

the prisons, could send mind waves to the Governor and con

trol him. President Reagan’s interference in the execution

process, etc.

App. at 158a (emphases added).

~ App. at 161a. The “disorder,” however, “seem[edl contrived

and recently learned” and, therefore, not a “natural insanity.” Id.

at 162a. But see earlier report of non-commission psychiatrist:

[Petitioner] is suffering from schizophrenia, undifferentiated

type, acute and chronic. The delusional material, the free-

floating and disorganized ideational and verbal productivity,

and his flatness of afreet are the highlights of the signs leading

to this diagnosis of psychosis. The possibility that he could

be lying or malingering is indeed remote in my professional

opinion.

Id. at 100a (emphasis added).

23 Id. at 164a.

24 Id. at 166a.

23 Id. at 164a.

22

counsel or by independent mental health experts.10 The

absence of any adversarial debate on the issue of Peti

tioner’s competency deprived the Governor of the oppor

tunity to test the accuracy of the conclusions reached by

the three state-appointed psychiatrists.

The opportunity to challenge the commission’s findings

was especially critical to a proper determination by the

Governor of Petitioner’s competency because, although all

of the examiners agreed that Petitioner suffers from

some form of serious mental disorder, they disagreed as

to the severity of his mental disorder. Moreover, the

commission’s conclusions differed radically from the con

clusions of two other psychiatrists who earlier had per

formed more extensive and comprehensive examinations

of Petitioner, with no indication that these earlier con

clusions had been considered by the three State psychia

trists or reconciled with the conclusions they reported to

the Governor. Because Petitioner was not given an oppor

tunity to respond to the findings of the commission ex

aminers, the quality of those findings was untested by the

“truth-seeking function” of the adversary process, and

were inherently unreliable. See Gardner v. Florida, 430

U.S. at 359. This conclusion is especially warranted be

cause the decisionmaker—the Governor—was a lay per

son who lacked the specialized knowledge and training

necessary to evaluate the conflicting evidence, a t least

without the benefit of an adversarial hearing. In view

of these procedural deficiencies, the risk of error to which

the determination of Petitioner's competency was sub

jected is constitutionally intolerable.

Like the absence of a hearing, the failure to provide

Petitioner with the meaningful assistance of a competent

mental health professional during these proceedings pre- 20

20 Indeed, in construing this statute, the Florida Supreme Court

approved the Governor's “publicly announced policy of excluding all

advocacy on the part of the condemned from the process of deter

mining whether a person under a sentence of death is insane.”

Goode v. Wainwright, 448 So.2d 999, 1001 (Fla. 1984).

eluded the Governor’s individualized consideration of all

relevant factors and substantially undermined the possi

bility of accurate factfinding. Although Petitioner’s men

tal condition was evaluated by two psychiatrists prior to

the § 922.07 proceeding, the failure to provide for mean

ingful participation in the proceedings by these profes

sionals resulted in the exclusion of highly probative evi

dence on the issue of Petitioner’s competency. Not only

were the comprehensive reports of these professionals not

considered by the Governor,-7 but he was not even myde

aware of the existence of these reports by the commis

sion psychiatrists. Nor were the commission psychia

trists required to explain, deny, or otherwise account for

the extensive documentation by these professionals of

Petitioner s psychotic delusional processes, and their con

clusions that Petitioner’s severe psychosis “suicidally

compels him to embrace his own death” and that he

“lacks the mental capacity to understand the reasons

why [the death penalty] is being imposed on him.” App.

at 155a, 158a. Thus, the Governor’s decision was based

upon partial and unchallenged information of highly

questionable accuracy. This exclusion of highly relevant

information is inconsistent with the constitutional re

quirement that the decisionmaker in capital proceedings

“possess[] the fullest information possible concerning the

defendant’s life and characteristics,” including any miti

gating evidence. Lockett v. Ohio, 438 U.S. at 003, quoting

Williams v. New York, 337 U.S. 241, 247 (1949).

The failure to provide Petitioner with an adversary

proceeding in which he could be assisted meaningfully by

competent mental health professionals is especially egre

gious in view of the nature of the “examination” con

ducted by the state-appointed psychiatrists. As noted

above, their “examination” consisted of a one-half hour

interview with Petitioner in the prison courtroom, con- 27

27 There is no provision in the statutory scheme of § 022.07 for

submitting materials other than those prepared by the commission

psychiatrists to the Governor.

23

24

versations with the prison staff, inspection of Petition

er’s cell and cursory review, at best, of background ma

terials containing Petitioner’s medical history and re

ports of other psychiatric evaluations. These procedures

fall significantly below the generally accepted standard of

care necessary to produce reliable forensic mental health

evaluations.2®

First, “ [b]ecause psychological states are complex and

fluctuate, a single and relatively brief examination is

. . . inadequate.” J. Zis k in , 2 Co ping W ith P sychiatric

a nd Psychological T e stim o n y 13 (3d ed. 1981). See

also Ziskin, Giving Expert Testimony: Pitfalls and Haz

ards for the Psychologist in Court, in T he Role of t h e

F orensic P sychologist 101 (G. Cooke, ed. 1980) (“ [A]

single examination even of two to three hours duration,

is insufficient . . . . [M laterial elicited in a single ses

sion might be quite different a week later in the same

individual . . . . [I ]t is advisable to spread the examina

tion over at least two and preferably three sessions.” ).

Manifestations of schizophrenia “are present one day and

not the next. They are revealed to one examiner and not

to another . . . . A complete account of a patient’s symp-

tomotology, therefore, demands that he be observed over

an extended period of time.” L. B ellak & L. Loeb , T he

S chizo ph renic S yndro m e , 337-38 (19G9), cited in Hays

v. Murphy, 663 F.2d 1004, 1012 n.13 (10th Cir. 1981)

(discussion of competency to bring habeas proceeding on

one’s own behalf). A one-half hour examination fails to

provide a sufficient basis for an accurate and reliable

professional opinion as to a condemned prisoner’s compe

tency to be executed.

Proper clinical evaluation also requires the establishment

of a trusting relationship with the examiner, in a physical

setting that is conducive to evoking the spontaneous and 28

28 See also the critical reviews of these procedures by two

nationally-known forensic psychiatrists. App. at l(!'Ja, 187a. See

generally nn.30, 32, infra.

25

candid exchange with the subject that forms the prin

cipal basis for the evaluation. Standard 4.1 of the Stand

ards for Providers of Psychological Services, requires

psychologists to “promote the development in the service

setting of a physical, organizational, and social environ

ment that facilitates optimal human functioning.” See

oluo APA, Specialty Guidelines for the Delivery of Serv

ices by Clinical Psychologists at Guideline 4, 36 A m.

Psychol. 640 (1981). The likelihood that, given Peti

tioner’s paranoid condition, the courtroom was inherently

“oppressive” to Petitioner and thereby increased the dif

ficulty of establishing trust with his examiners, is sub

stantial. See generally Wilson, Prison <4.s An Environ

ment in The Role Of T he Forensic Psychologist,

supra at 279. This impression might have been rein

forced further by the presence of correctional officers,

and numerous other “strange” individuals—including the

three psychiatrists—all observing him during the same

brief time period. Finally, the very short time period

made it extremely unlikely that any of the commission

psychiatrists would be able to establish sufficient rap

port with Petitioner to evoke reliable data on which to

base a valid assessment of his mental condition.29 30

29 The Interpretation of this Standard provides in pertinent part:

As providers of services, psychologists have the responsibility

to be concerned with the environment of their service unit,

especially as it affects the quality of service, but also as it im

pinges on human functioning . . . . Physical arrangements and

organizational policies and procedures should be conducive to

the human dignity, self-respect, and optimal functioning of

users, and to the effective delivery of service.

APA, Starulards for Providers of Psychological Services, 32 Am.

Psychol. 495 (1977).

•10 These criticisms were made also by the forensic psychiatrists

who reviewed the commission psychiatrists’ procedures:

The conditions under which the interview was conducted, in

cluding the amount of time spent interviewing [Petitioner],

were unlikely to produce sufficient data for reliable forensic

In addition to the clinical interview, forensically-

oriented mental health professionals generally recjuire

appropriate physical examinations and certain standard

psychological test batteries before rendering an opinion

on an individual’s mental competency. See generally T.

Blau, T he Psychologist As E xpert Witness (1984);

H. Kaplan, A. F reeman & B. Saddock, A Comprehen

sive Textbook Of Psychiatry/III (3d ed. 1980). Fur

ther psychological assessment was especially important

in this case because of the difficulties of establishing ver

bal communication with Petitioner.31 Had psychological

tests been administered to Petitioner, the commission psy

chiatrists would not have had to rely “largely on infer

ential deduction from physical behavioral observation,”

App. at 160a, and other nonverbal indicia, which “greatly

enhance the opportunity for error and misinterpretation

evaluation. The interview was conducted in a courtroom, and

a “room full” of people, including- one or more correctional

officers, was present. The environment was thus not conducive

to the informal, intimate setting which is generally necessary

to establish sufficient rapport for a psychiatric interview. In

the setting described it would have been extremely difficult for

(Petitioner] to fully reveal his problems or the nature of his

illness. The thirty minute effort to establish communication

under the conditions already noted was also inadequate. On

rare occasions some patients can be accurately diagnosed in

such a brief period. (Petitioner!’s diagnosis, however, was

not easily made due to the unusual nature of his behavior and

his unusual method of communicating.

App. at 171a. See also id. at 192a.

31 One of the commission psychiatrists reported that “(t]he in

terview was conducted with great difficulty from a verbal point of

view, since the inmate responded] to questions in a stylized, man-

neristic doggerel. Thus, an answer to a question might be ‘beckon

one, come one, Alvin one, Q one, kind one.’ ’’ App. at 160a.

Another reported that “(Petitioner ] did not initially respond but

did so after hi3 lawyers encouraged him. Most of his responses to

the questions were bizarre. He continued to respond by jibberish

talk such as ‘break one’, ‘God one’, ‘heaven one.’ ” Id. at 163a.

26

on the part of the examining [clinician],” in assessing

Petitioner’s competency

Psychological tests, which measure a variety of factors

including intelligence, personality and psychopathology,33

27

33 See Critique of Forensic Psychiatrist at App. 100a:

[One of the commission psychiatristsj indicated that by his

ability to “read between the lines” of verbal responses which

[Petitioner] did give that [the psychiatrist) was of the

opinion that [Petitioner] knew exactly what was going on[,]

but if one relies on the transcript of the interchange between

the psychiatrist and [Petitioner] then there is great doubt, at

least to this observer, that there was a rational interchange be

tween [Petitioner] and the psychiatrist, because [Petitioner]

gave irrelevant responses to questions put to him although

the words he used had some association with the questions

asked. [Petitioner]’s responses do not indicate he had a ra

tional understanding of the process and in fact some of [Peti

tioner]^ responses were interpreted by [the psychiatrist] to

mean [Petitioner] maintained the belief that he would be spared

by the angel of death and this delusional belief is in keeping

with other delusional beliefs that [Petitioner] manifested to

others in his correspondence.

33 See, e.g., the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (“WAIS”),

the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (“MMPI”), the