NAACP Detroit Branch v. Detroit Police Officers Association (DPOA) Petition for Writ of Certiorari and Appendix to Petition

Public Court Documents

September 17, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP Detroit Branch v. Detroit Police Officers Association (DPOA) Petition for Writ of Certiorari and Appendix to Petition, 1990. 45fd5134-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0b9bb9ac-e64a-4529-9ef1-828400f2c871/naacp-detroit-branch-v-detroit-police-officers-association-dpoa-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-and-appendix-to-petition. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

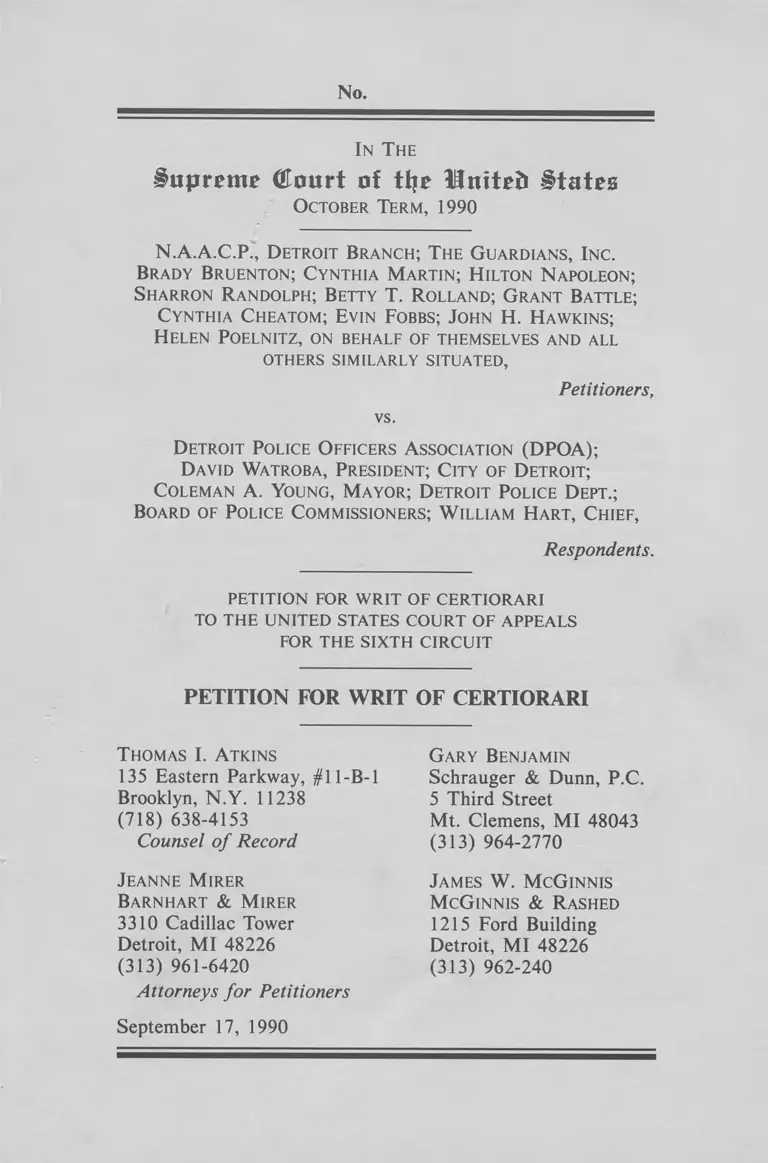

No.

In T he

Supreme Court of tl?e United §tates

October Term, 1990

N.A.A.C.P., D etroit Branch; T he Guardians, Inc .

Brady Bruenton; Cynthia M artin; H ilton N apoleon;

S harron Randolph; Betty T. Rolland; Grant Battle;

Cynthia C heatom; Evin Fobbs; John H. H awkins;

H elen Poelnitz, on behalf of themselves and all

OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED,

Petitioners,

vs.

D etroit Police O fficers A ssociation (DPOA);

D avid Watroba, President; C ity of D etroit;

Coleman A. Young, Mayor; D etroit Police D ept.;

Board of Police Commissioners; W illiam H art, C hief,

Respondents.

p e t it io n f o r w r it o f c e r t io r a r i

t o t h e u n i t e d s t a t e s c o u r t o f a p p e a l s

fo r t h e s ix t h c ir c u it

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

T homas I. A tkins

135 Eastern Parkway, # 11 -B-1

Brooklyn, N.Y. 11238

(718) 638-4153

Counsel o f Record

Jeanne M irer

Barnhart & M irer

3310 Cadillac Tower

Detroit, MI 48226

(313) 961-6420

Attorneys fo r Petitioners

Gary Benjamin

Schrauger & Dunn, P.C.

5 Third Street

Mt. Clemens, MI 48043

(313) 964-2770

James W. M cG innis

M cG innis & R ashed

1215 Ford Building

Detroit, MI 48226

(313) 962-240

September 17, 1990

1

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

Petitioners are a certified class of 800 Black Detroit police

officers who were laid off in reverse seniority order from their

jobs in 1979 and 1980. The district court, finding a violation of

Petitioners’ rights under the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment, ordered reinstatement of all laid off

officers, both Black and White, and enjoined further uniformed

police layoffs without court approval. The Court of Appeals for

the Sixth Circuit initially reversed and remanded in 1987. On

remand, the district court declared the case to be moot and

dismissed it, on the grounds that all the officers had been rehired

by the City and Blacks then constituted a majority of the union,

making them capable of protecting themselves through union

democracy. Petitioners appealed the determination of mootness.

The court of appeals reversed the determination of mootness, but

then ordered the case dismissed, on the grounds that §703(h) of

Title VII immunized the City’s layoffs from attack because they

were done pursuant to a bona fide seniority system, and it further

found that the union’s conduct was similarly immunized from

attack.

The questions presented are:

(1) Did the layoffs violate Petitioners’ Equal Protec

tion rights where, at the time of the layoffs, the City of

Detroit was under an unmet constitutional obligation to

remedy the effects of its pervasive intentional racial discrim

ination in Police Department employment.

(2) In a case in which no formal complaints were filed

with the EEOC, does the Equal Protection Clause, enforcea

ble through 42 U.S.C. §1983, empower federal courts to

enjoin such layoffs, notwithstanding §703(h) of Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act . of 1964, under which the routine

application of a seniority system does not violate Title VII?

(3) Where the DPOA (Petitioners’ union) failed to

bargain about these layoffs and where the Petitioners’ race

limited the union’s efforts to find alternatives to the layoffs.

il

is the union liable under its Duty of Fair Representation and

42 U.S.C. §1981, even if layoffs are not a mandatory subject

of bargaining?

(4) Will the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1990

require remand of this case so that the Sixth Circuit Court

of Appeals may revisit its decision?

Ill

With the exception of the Detroit Branch of the NAACP, all

parties with an interest in this matter are fully contained on the

cover page.

The Detroit Branch of the NAACP is the biggest one of

nearly 2,000 subsidiary units of the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People, a New York Corporation, with

current headquarters at 4805 Mt. Hope Dr., Baltimore, MD

21215, (301) 486-9191. The NAACP, a membership organiza

tion, seeks to confront and combat racial discrimination in all

areas of American life, including in law enforcement.

The Guardians, Inc. is a Michigan Corporation, with a

membership of Black Police Officers, drawn primarily, but not

exclusively, from the City of Detroit’s Police Department. Its

aims are to advance the interests of blacks and other non-whites

in the law enforcement field, including to confront racial discrim

ination, segregation and prejudice where viewed as impediments

to equal opportunity for black officers.

The 10 individual Petitioners were all Detroit police officers

and members of the Guardians at the time of trial below.

The named Plaintiffs-Petitioners are the representatives for

a certified class which consists of black uniformed police officers

in the City of Detroit who were laid off in either 1979 or 1980

from their employment with the Detroit Police Department.

LIST OF PARTIES

Thomas I. Atkins, Esq.

Counsel o f Record for

Petitioners

IV

Page

QUESTIONS PRESEN TED ............................................. i

LIST OF PA R TIES............................................................. iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.............................................. v

INTRODUCTORY PRA Y ER........................................... ix

CITATIONS TO OPINIONS BELOW............................ x

JURISDICTION................................................................... xi

STATUTES, CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS . . . . xii

STATEMENT OF THE C A SE ......................................... 1

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE W R IT ................ 6

I. THE COURT OF APPEALS OPINION

CONFLICTS WITH THE DECISIONS OF

OTHER CIRCUITS CONCERNING THE

REMEDIAL RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE

EQUAL PROTECTION CLAUSE AND

TITLE V II ..................................................................... 6

II. THE Opinion BELOW CONFLICTS WITH

LANDMARK CASES IN THIS COURT

CONCERNING THE REMEDIAL REACH OF

THE EQUAL PROTECTION CLAUSE AND 42

U.S.C. 1983 ................................................................... 10

III. THE SIXTH CIRCUIT’S Opinion RAISES

IMPORTANT ISSUES RE: 42 U.S.C. 1983

THAT NEED RESOLUTION BY THIS COURT 15

IV. THE OPINION BELOW ON UNION

LIABILITY CONFLICTS IN PRINCIPLE

WITH APPLICABLE RULINGS OF THIS

COURT

District Court Findings On DPOA L iab ility ........... 19

The Opinion’s Dismissal of the §1981 Claim

Conflicts With This Court’s Holding in Johnson v.

Railway Express Agency .............................................. 21

The Duty of Fair Representation C laim .................... 24

V. HISTORIC AND CURRENT

CONGRESSIONAL ACTION EACH

SUPPORTS GRANTING THE PETITION ......... 26

Conclusion.............................................................................. 27

TABLE OF CONTENTS

V

FEDERAL CASES Page

Alexander v. Chicago Park District, 773 F.2d

850 (7th Cir. 1985)................................................ 8

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Company, 415 U.S.

36 (1974)................................................................. 12

Alvey v. General Electric, 622 F.2d 1279

(7th Cir. 1 9 8 0 )...................................................... 24

American Tobacco Company v. Patterson, 456

U.S. 63 (1982),...................................................... 18

Arthur v. Nyquist, 712 F.2d 816 (2d Cir. 1983) . 6, 7, 8

Baker v. City o f Detroit, 483 F. Supp. 930 (E.D.

Mich. 1979)............................................................. 1, 2, 4,

6, 9

Bratton v. City o f Detroit, 704 F.2d 878

(6th Cir. 1 9 8 3 )...................................................... 1 ,9

Brown v. Bd. o f Education,

347 U.S. 483 (1954).............................................. 2 ,10

Brown v. Bd. o f Education,

349 U.S. 294 (1955).............................................. 2 ,10

Brown v. G.S.A,

425 U.S. 820 (1976).............................................. 22

Carpenter v. Stephen F. Austin State University,

706 F.2d 608 (5th Cir. 1983)............................... 8

Chance v. Board o f Examiners and Board o f

Education o f the City o f New York, 534 F.2d

993 (2nd Cir. 1 9 7 6 ).............................................. 9

City o f Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980) . . . 26

Columbus Bd. o f Educ. v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449

(1979) ............................ -........................................ 2,11

Day v. Wayne County Board o f Auditors, 749

F.2d 119 (6th Cir. 1984);...................................... 8

Dayton Bd. v. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526 (1979) . . 2, 11

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

VI

FEDERAL CASES P?H£

Drummond v. Acree, 409 U.S. 1228 (1972)......... 17

Emmanuel v. Omaha Carpenters District

Council, 535 F.2d 420 (8th Cir. 1 9 7 6 )............. 24

Firefighters Local Union No. 1784 v. Stotts,

467 U.S. 561 (1984).............................................. 9, 18, 24

General Electric v. Gilbert, 429 U.S. 125 (1976) . 26

Goodman v. Luckens Steel Co., 482 U.S. 656

(1987) ..................................................................... 24

Grano v. Department o f Development, City of

Columbus, 637 F.2d 1073 (6th Cir. 1980) ___ 8

Great American Federal Savings & Loan

Association v. Novotny, 442 U.S. 366 (1979) . . 22

Green v. New Kent County Bd. o f Education,

391 U.S. 430 (1968)............................................ 2 ,6 ,1 0 ,

11, 13

Griffin v. Breckenridge, 403 U.S. 88 (1971)............. 26

Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. 424 (1971).............................................. 9 ,14

Groves City College v. Bell,

465 U.S. 555 (1984).............................................. 26

Hines v. Anchor Motor Freight, Inc.,

424 U.S. 554 (1976).............................................. 24

Jennings v. American Postal Workers Union,

672 F.2d 712 (8th Cir. 1982)................................ 24

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc.,

421 U.S. 454 (1975).............................................. 12 ,21 ,22

Jones v. Mayer, 392 U.S. 409 (1968).................... 26

Keyes v. School Dist. No. I, Denver, 413 U.S.

189 (1973)....................... 10,11

Local 28 o f Sheet Metal Workers v. EEOC,

478 U.S. 421 (1986).............................................. 9

Louisiana v. U.S., 380 U.S. 145 (1 9 6 5 )............... 10, 1 1, 16

Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cranch 137 (1 8 0 3 )......... 15, 17

FEDERAL CASES Page

McDonnell-Douglas Corp. v. Green, 41 1 U S

792 (1973)............................................................... 14

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (1 9 7 7 )........... 7

Missouri v. Jenkins, 110 S. Ct. 1651, 109 L. Ed.

2d 31, 58 U.S.L.W. 4480 (1990)........................ 16, 19

Morgan v. O’Bryant, 671 F.2d 23 (1st Cir. 1982) 6, 7, 8

Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535 (1974)............. 14

NAACP v. DPOA, 591 F. Supp. 1194

(E.D. Mich. 1984).................................................. 2, 3, 6, 9,

19

NAACP v. DPOA, 629 F. Supp. 1173

(E.D. Mich. 1985).................................................. 20

NAACP v. DPOA, 676 F. Supp. 790

(E.D. Mich. 1988).................................................. 5, 1 , 9 ,

21

NAACP v. DPOA, 685 F. Supp. 1004

(E.D. Mich. 1988).................................................. 5 7

NAACP v. DPOA, 821 F.2d 328 (6th Cir. 1987) . 4

NAACP v. DPOA, 900 F.2d 903 (6th Cir. 1990) . passim

Patterson v. McLean, 109 S. Ct. 2363 (1989) . . . 5, 23

North Carolina State Bd. o f Education v.

Swann, 402 U.S. 43 (1 9 7 1 )................................. 16

Ratliff v. City o f Milwaukee, 795 F.2d 612 (7th

Cir. 1986), cert, denied, 106 S. Ct. 1492

(1986) ...................................................................... 8

Smith v. Robinson, 468 U.S. 992 (1 9 8 4 )............... 26

Steel v. L & N Railway, 323 U.S. 192 (1944). . . 24

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f

Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1 9 7 1 )............................ 6, 9, 10,

17

Teamsters v. United States,

431 U.S. 324 (1977).............................................. 14,17

Trans World Airlines, Inc. v. Hardison,

432 U.S. 63 (1 9 7 7 ),.............................................. 18

vii

Vl l l

FEDERAL CASES Page

Trigg v. Fort Wayne Community Schools,

766 F.2d 299 (7th Cir. 1985)’................................. 8

United States v. Paradise, 107 S. Ct. 1053

(1987) ..................................................................... 9

U S. v. Price, 383 U.S. 787 (1 9 6 6 )........................ 26

Vaca v. Sipes, 386 U.S. 171 (1967) ...................... 24

Vulcan Society o f N. Y. City Fire Department v.

Civil Service Commission, 490 F.2d 387

(2d Cir. 1973)........................................................ 8

Washington v. Davis, 626 U.S. 229 (1976)........... 15

Watkins v. United Steel Workers, 516 F.2d 41

(5th Cir. 1 9 7 5 )...................................................... 23

Wright v. Council o f City o f Emporia, 407 U.S.

451, 92 S. Ct. 2196 (1972) ................................... 11

Wyatt v. Interstate & Ocean Transport Co., 623

F.2d 888 (4th Cir. 1980 )..................................... 24

STATE CASES

Local 1277, AFSCME v. City o f Centerline, 414

Mich. 642, 327 N.W.2d 822 .............................. 24, 25

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISION

Tenth Amendment .................................................... 16, 20

Fourteenth Amendment, 42 U.S.C. §1981 ........... passim

STATUTES AND LEGISLATIVE MATERIALS

42 U.S.C. §1981......................................................... passim

42 U.S.C. §1983 ......................................................... passim

Title VII o f the 1964 Civil Rights Act, 42

U.S.C. §2000e et seq.............................................. passim

Civil Rights Act o f 1990, Sen. Bill 2104 ............. 26

The Congressional Globe, 42d Congress,

1st Sess. (1871)...................................................... 26

INTRODUCTORY PRAYER

Now come the Petitioners to respectfully request that this

Court grant the Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the 6/18/90

Opinion of the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, so that

Petitioners will be permitted to discuss the rulings below which

conflict with decisions of other circuits and with the rulings of

this Court.

Respectfully submitted,

Thomas I. Atkins

X

CITATIONS TO OPINIONS BELOW

The opinions below which are implicated in this Petition are:

1. NAACP v. DPOA,

591 F. Supp. 1194 (E.D. Mich. 1984)

2. NAACP v. DPOA,

629 F. Supp. 1173 (E.D. Mich. 1985)

3. NAACP v. DPOA,

676 F. Supp. 790 (E.D. Mich. 1988)

4. NAACP v. DPOA,

685 F. Supp. 1004 (E.D. Mich. 1988)

5. NAACP v. DPOA,

821 F.2d 328 (6th Cir. 1987)

6. NAACP v. DPOA,

900 F.2d 903 (6th Cir. 1990)

XI

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

was rendered on April 9, 1990. The Court of Appeals denied

Petitioners’ request for Rehearing and Rehearing En Banc on

June 18, 1990. NAACPv. DPOA, 900 F.2d 903 (6th Cir. 1990).

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C.

§1254(1).

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS

1. The Equal Protection Clause o f the Fourteenth Amend

ment is the only constitutional provision directly impli

cated in this Petition.

Statutory provisions implicated are:

2. 42 U.S.C. §1981

“All persons within the jurisdiction of the United States

shall have the same right in every State and Territory to

make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, give

evidence, and to the full and equal benefit of all laws and

proceedings for the security of persons and property as is

enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be subject to like

punishment, pains, penalties, taxes, licenses, and exac

tions of every kind, and to no other.” Rev. Stat. @ 1977.

3. 42 U.S.C. §1983

“Every person who, under color of any statute, ordinance,

regulation, custom, or usage, of any State or Territory,

subjects, or causes to be subjected, any citizen of the

United States or other person within the jurisdiction

thereof to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or

immunities secured by the Constitution and laws, shall

be liable to the party injured in an action at law, suit in

equity, or other proper proceeding for redress.”

4. 42 U.S.C. §2000e et seq., particularly §703(h), which

provides protection for bona fide seniority systems from

suit under Title VII.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U. S. C. @

2000e-2(a), provides;

“(a) It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an

employer—

“(1) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any

individual, or otherwise to discriminate

against any individual with respect to his

compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges

xii

XIII

of employment, because of such individual’s

race, color, religion, sex, or national origin; or

“(2) to limit, segregate, or classify his employees or

applicants for employment in any way which

would deprive or tend to deprive any individ

ual of employment opportunities or otherwise

adversely affect his status as an employee,

because of such individual’s race, color, relig

ion, sex, or national origin.”

5. §703(h) o f the Civil Rights Act o f 1964, as set forth in 42

U.S.C. §2000e-2(h) states, in pertinent part:

“Notwithstanding any other provision of this subchapter,

it shall not be an unlawful employment practice for an

employer to apply different standards of compensation,

or different terms, conditions, or privileges of employ

ment pursuant to a bona fide seniority or merit system, or

a system which measures earnings by quantity or quality

of production or to employees who work in different

locations, provided that such differences are not the

result of an intention to discriminate because of race,

color, religion, sex, or national origin.”

1

Petitioners are a certified class of eight hundred Black police

officers who were laid off from their jobs in the Detroit Police

Department. The layoffs in question occurred in two waves, one

in October of 1979, the other in September 1980. A total of

eleven hundred officers were laid off. The Complaint in this case,

filed on September 30, 1980 by the NAACP, the Guardians

Police Association, and ten individual laid off officers, alleged

that these layoffs inter alia, violated the Petitioners’ rights under

the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, 42

U.S.C. §1981, and §1983.

The Plaintiffs’ Equal Protection claim was grounded in more

than two dozen pages of findings made by Judge Keith in Baker

v. City o f Detroit, 483 F. Supp. 930 (E.D. Mich. 1979), holding

the City liable for past intentional racial discrimination violative

of the Equal Protection Clause. Included were findings that the

City of Detroit had: (1) systematically excluded Blacks from

consideration for hiring; (2) refused to hire all but a token

number of Blacks; (3) segregated those Blacks who were hired;

and (4) prevented Blacks from obtaining promotions to ranks

above police officer. Baker v. City o f Detroit, supra.'

Petitioners’ case was filed against the City of Detroit and the

Detroit Police Officers Association (DPOA), the union which was

certified to represent all uniformed police officers. The Baker

findings formed the basis for the instant controversy because at

the time of the layoffs in 1979 and 1980, the City had not yet

remedied the effects of its prior discriminatory conduct. They

had the effect of reducing Black representation on the uniformed

force from 39% to 26%, at a time the percentage of Blacks

necessary for the City to have eliminated the effects of its prior 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

1 The findings in Baker, affirmed in toto by the Court of Appeals, Bratton v.

City o f Detroit, 704 F.2d 878 (6th Cir. 1983), arose because of an

unsuccessful challenge by White police sergeants to a one-for-one affirma

tive promotion plan implemented in 1974 by the City after the Board of

Police Commissioners determined such a plan was necessary. The findings

in Baker were de novo, and based on the record made in the trial of a case

in which one of the Petitioners herein, the Guardian Police Association,

was an intervening Defendant.

2

conduct was slightly in excess of 50%. NAACP v. DPOA, 591 F.

Supp. 1194, 1200-01 (E.D. Mich. 1984).

Petitioners alleged that the City, by virtue of the findings of

past intentional discrimination in Baker, was under an affirma

tive duty to remedy not only the fact of that past discrimination

but also its effects, including the duty not to abandon its effort

until the effects had been eliminated “root and branch”.2 The

City was sued pursuant to the Equal Protection Clause of the

14th Amendment, and 42 U.S.C. §1983.

Petitioners alleged that the DPOA could have caused the

layoffs to be avoided, had the unions’s all-white leadership

refrained from discriminating on the basis of race. That is, had

race not been factored in as a negotiation strategy, alternatives to

the layoffs might well have been effected. Petitioners charged

that the DPOA’s race-based conduct violated both the union’s

Duty of Fair Representation and Petitioner’s rights under

42 U.S.C. §1981.

Petitioners sought declaratory relief under the doctrine of

collateral estoppel, asking that the findings of intentional dis

crimination made in Baker be deemed binding on the City and

the DPOA in the instant case. On 11/17/81 The district court

granted that relief, making relitigation of those issues unneces

sary. Petitioners thereafter sought Partial Summary Judgment

against the City on the issue of liability. On 2/24/84, the district

court granted the Partial Summary Judgment Motion, holding:

“ 1. That, based on the findings of intentional discrimi

nation in Baker v. City o f Detroit, 483 F. Supp. 930 (cit.

omitted) (E.D. Mich. 1979) . . . (cit. omitted), the City had

a constitutionally imposed continuing affirmative obligation

not only to stop the discrimination but to remedy all of the

effects of the discrimination.

2 For these propositions, Petitioners relied on the principles stated in Brown

v. Bd. o f Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) (Brown I); Brown v. Bd. o f

Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) (Brown II); Green v. New Kent County

Bd. o f Education, 391 U.S. 430 (1968); Columbus Bd. v. Penick, 443

U.S. 449 (1979); and Dayton Bd. v. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526 (1979)

(Dayton II).

3

“2. That the City had not yet remedied the effects of

this prior discrimination when, in 1979 and 1980, it reduced

black representation on the police force.

“3. That by these layoffs, which the City knew full well

would reduce black representation on the police force, the

City breached its affirmative obligation to the plaintiffs in

violation of their rights under the Fourteenth Amendment.”3

Trial commenced in May 1984 on the issues of liability

against the DPOA and remedy against the City. The district

court’s 7/25/84 opinion ordered the reinstatement of all laid off

police officers, both black and white, and enjoined any further

layoffs without court approval. The officers were not granted

back pay, but were to retain their full seniority as if they had not

been laid off. NAACP v. DPOA, 591 F. Supp., @ 1220-1221.

The Court also found that the union had violated the Duty

of Fair Representation in its handling of the matter, and made

extensive findings as to the history of racial hostility toward

DPOA’s black members and their aspirations.4

Of particular importance to this Petition is the district

court’s statement that it:

“did not accept the City’s position advanced in post-trial

argument that Title VII law regarding bona fide seniority

systems is controlling in Constitutional litigation”.5

3 NAAC P v. DPOA, 591 F. Supp. 1194, 1199 (E.D. Mich. 1984). The

district court noted the City had admitted in its pleadings that it had

made the race-conscious and politically-expedient decision to face a law

suit by Blacks rather than by whites.

4 The Court placed the blame for the violation on a union leadership which

failed to reflect or be sensitive to its black membership. The district court

therefore ordered the union to integrate its leadership bodies and commit

tees within twelve months. Ibid.

5 NAACP v. DPOA, 591 F. Supp., @ 1203.

4

The district court’s remedial order, nonetheless, left the

seniority system intact.6

The City reinstated all the officers in compliance with the

district court’s injunctive orders. The City and the DPOA

appealed as to liability and remedy, and Petitioners appealed the

denial of back pay, other monetary relief such as pension credits,

and the refusal of the district court to order reinstatement of

those class members driven by the illegal layoffs to renounce

recall rights in order to secure interim employment.

On 6/12/87, the court of appeals, while affirming the dis

trict court’s ruling that collateral estoppel properly made the

findings in Baker binding, remanded the case on the grounds that

those findings, standing alone, were insufficient to support the

relief.7

As to the union’s liability, the court of appeals held that, as

layoffs were not a mandatory subject of bargaining, the DPOA

had no duty to bargain over them, and that the failure to

negotiate about the layoffs could not be the basis of a Duty of

Fair Representation violation. The court of appeals remanded for

action consistent with its Opinion, particularly instructing the

district court to review Petitioners’ §1981 claim against the

union.8

On remand, the district court denied motions by the City to

enter judgment, and by the union for summary judgment, and

accepted Petitioners’ claim that the remand hearing might pro

duce findings to cure the alleged defects found by the court of

6 Petitioners had not directly attacked the seniority system, which was

negotiated in 1967 at a time when the City was found to be discriminat

ing. Rather, Petitioners argued that contractual seniority rights could not

be relied on to defeat Constitutional rights.

7 NAAC P v. DPOA, 821 F.2d 328 (6th Cir. 1987). The Court of Appeals

largely ignored the supplemental, de novo findings of liability made by the

district court, based on the trial held below in the Spring of 1984.

8 NAAC P v. DPOA, 821 F.2d, @ 333. The District Court had not reached

this claim in light of its ruling on the Duty of Fair Representation charge.

5

appeals.9 However, the district court declined to take any further

action on the ground that the case was then moot.10 *

Petitioners appealed the mootness finding. The court of

appeals, while agreeing with Petitioners that the case was not

moot, ordered the case dismissed anyway."

As it related to the City defendants, the dismissal was

premised on the panel’s perception of Title VII law and its

holding that §703(h) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. §2000e, immunized

the City’s layoffs from attack, because the layoffs had been based

on the seniority system.12

The court also dismissed the claim as to the union, holding

that the §1981 claim against the union was dependent upon the

claim against the City, which it had already held was barred by

§703(h). Citing Patterson v. McLean, 109 S. Ct. 2363 (1989), it

noted that the §1981 claim was most likely not viable in any

event.

A timely Petition for Rehearing was denied on 6/18/90,

giving rise to the instant Petition for a Writ of Certiorari.

9 NAACP v. DPOA, 676 F. Supp. 790, 796 (E.D. Mich. 1988).

10 NAAC P v. DPOA, 685 F. Supp. 1004 (E.D. Mich. 1988). The district

court’s mootness ruling was based on its finding that, at the time of the

1988 remand hearing, the police force, through a combination of recalls

and new hires had surpassed the percentage of black representation that

the Court had previously found necessary to eliminate the effects of the

past intentional discrimination. Similarly, the district court found the

claim for relief against the union moot because blacks were now more

than 50% of the union and, the Court reasoned, capable of electing

leadership that would protect their interests. Ibid, @ 1007.

" NAACP v. DPOA, 900 F.2d 903 (6th Cir. 1990)

12 The court of appeals assigned no legal significance to the fact that

Petitioners were seeking to vindicate Constitutional rights, nor to the fact

that the City was protected from any collateral action by the DPOA

precisely because the challenged layoffs occurred by seniority, nor to the

fact that no Title VII complaints had been filed in this case with the

EEOC.

6

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

The Court of Appeals Opinion Conflicts with the Decisions

of Other Circuits Concerning the Remedial Relationship

Between the Equal Protection Clause and Title VII

The Opinion below has created a direct conflict between the

Circuits concerning the scope of a district court’s powers under

the Equal Protection Clause to remedy the effects of intentional

past employment discrimination where seniority systems exist,

whether or not Title VII complaints are involved.

Prior to this case, the Circuits were in agreement that where

a federal court had found pervasive violations of the Equal

Protection Clause, it had a duty to eliminate the effects of that

discrimination “root and branch”, Green v. New Kent County

School Board, 391 U.S. 430, 438 (1968), and that race conscious

remedies are not only permitted but required where color blind

approaches would be inadequate, Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklen-

burg Board o f Education, 401 U.S. 1, 28 (1971), even if those

remedies temporarily prevent the layoffs of some blacks. Morgan

v. O’Bryant, 671 F.2d 23 (1st Cir. 1982); Arthur v. Nyquist, 712

F.2d 816 (2d Cir. 1983).

In his 7/25/84 opinion, Judge Gilmore ordered that, as a

result of its intentional and unremedied discrimination in viola

tion of the Equal Protection Clause, the City must reinstate all

officers laid off in violation of that clause. He also enjoined the

City from laying off, suspending, or discharging any police officer

without prior approval of the Court.13

The Sixth Circuit ultimately reversed the injunction, finding

it to be barred by §703(h) of Title VII,14 specifically holding that

13 NAACP v. DPOA, 591 F. Supp., @ 1220-1221

14 As earlier noted, on the first appeal the Sixth Circuit found the injunction

improper because it was entered solely on the basis of factual findings in

Baker v. Detroit, 483 F.Supp 930 (E.D. Mich 1979). However, on

remand, the District Court held that Plaintiffs could demonstrate that,

7

the text of §703(h) “establishes an exception to liability for

employment discrimination based on race.”15

The Opinion below failed to recognize that the district court

is not limited to Title VII remedies where a claim is grounded in

the Equal Protection Clause and not Title VII, an error high

lighted by the conflict the Opinion creates with the First and

Second Circuit’s decisions in Morgan v. O’Bryant, 671 F.2d 23

(1st Cir. 1982),16 Arthur v. Nyquist, 712 F.2d 816 (2d Cir.

wholly apart from the Baker findings, the City’s prior unconstitutional

acts were a proximate cause of the 1979 and 1980 layoffs. NAAC P v.

DPOA, 676 F. Supp. 790, 796 (E.D. Mich. 1988). It then later held that

the issue was moot. NAAC P v. DPOA. 685 F. Supp. 1004 (E.D. Mich.

1988). It was on appeal from this Order that the Sixth Circuit reversed

the mootness finding and held that §703(h) barred the injunction

NAACP v. DPOA, 900 F.2d 903 (6th Cir. 1990).

15 NAACP v. DPOA. 900 F.2d 903, 907 (6th Cir. 1990). The Opinion

disregarded the fact that the district court injunction was based on a

finding of intentional discrimination violative of the Equal Protection

Clause, and had nothing to do with Title VII, stating “Congress did not

intend that its detailed remedial scheme constructed in Title VII be

circumvented through pleadings that allege other causes of action under

general statutes.”

16 In Morgan, the First Circuit addressed a case quite similar to this one.

The court considered the district court s refusal to modify a prior reme

dial order so as to allow for the layoffs of black administrators during a

budgetary crisis. The Court of Appeals held the orders of the district

court to satisfy the standards articulated by this Court in M illiken v.

Bradley. 433 U.S. 267, 280-281, 97 S.Ct. 2749, 2757, 53 L.Ed.2d 745

(1977). Specifically, the First Circuit found that these orders were

“reasonable" as required for race conscious remedies. It stated:

“They were necessary to safeguard the progress toward desegrega

tion painstakingly achieved over the least seven years. Without

them, the percentage of blacks would have fallen almost to its level

nearly a decade ago, before this suit was brought. Such a result

could not be countenanced.”

Morgan, supra, at 28

8

1983).17 Other Circuit Court opinions addressing the relation

ship between 1983 and Title VII have also found them to be

separate and unrelated.18

The Opinion below also conflicts with the remedial power

this Court has granted to district courts which seek to remedy the

present effects of past racial discrimination in employment where

the claim is not based on Title VII. Under such circumstances,

precedents from this Court make clear that the scope of the

remedy is not defined by constraints contained within Title VII.

While the Nyquist and Morgan decisions were both ren

dered in cases where intentional, state-imposed school discrimi

nation had been found, this Court has applied the same broad,

17 In Nyquist, the Buffalo Teachers Federation challenged a remedial plan

ordered by the district court which was designed to achieve a goal of 21%

minority teachers through a race conscious system for hiring and laying

off teachers. The Second Circuit rejected the Federation's argument that

§703(h) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 invalidated the district court’s

refusal to lift its remedial order. It found §703(h) inapplicable because:

“ H ere,. . . the suit was brought to remedy violations of the Constitu

tion rather than Title VII, and the district court made a finding of

intentional discrimination . . .

“Once a local board of education has been found to have employed

staff hiring practices that contribute to a racially segregated school

system, the District Court has the power to remedy those practices

and override seniority systems that perpetuate those practices.”

Nyquist, supra, at 822.

18 R a tliff v. City o f Milwaukee, 795 F.2d 612, 623-24 (7th Cir. 1986), cert,

denied, 106 S. Ct. 1492 (1986); Alexander v. Chicago Park District. 773

F.2d 850 (7th Cir. 1985); Trigg v. Fort Wayne Community Schools, 766

F.2d 299 (7th Cir. 1985); Carpenter v. Stephen F. Austin Sta te Univer

sity, 706 F.2d 608, 612 n.l (5th Cir. 1983) Vulcan Society o f N .Y. City

Fire Department v. Civil Service Commission, 490 F.2d 387, 390 n.l (2d

Cir. 1973) . Even other panels of the Sixth Circuit itself have handed

down decisions which noted the separate nature of Title VII and 1983

remedies: Day v. Wayne County Board o f Auditors, 749 F.2d 119 (6th

Cir. 1984); Grano v. Department o f Development, City o f Columbus

637 F.2d 1073 (6th Cir. 1980).

9

flexible rules to remedy intentional, state-imposed Equal Protec

tion violations in the context of employment discrimination.'9

The case below does not involve the situation found in

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971), where the

problem was to remedy the disparate impact of unintentional

discrimination."0 The findings of the district court below made

clear that the City of Detroit had engaged in long-running,

widespread, intentional, racial discrimination in the recruitment,

employment, deployment, and promotion of police officers, which

had affected and infected every segment of the Detroit Police

Department.19 20 21

19 See, United S tates v. Paradise, 107 S.Ct. 1053, 1073 (1987); Local 28 o f

Sheet M etal Workers v. EEOC. 478 U.S. 421, 480 (1986). See also,

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board o f Education, 402 U.S. 1,15

(1971), where Chief Justice Burger wrote for a unanimous court:

“a school desegregation case does not differ fundamentally from

other cases involving the framing of equitable remedies to repair the

denial of a constitutional right. The task is to correct, by a balancing

of the individual and collective interests, the 'condition that offends

the Constitution’.”

20 See, Firefighters Local Union No. 1784 v. Stotts, 467 U.S. 561, 590 fn.

16 (1984) (District court’s order enjoining layoffs of black employees

invalidated where there had been no finding of intentional discrimina

tion.) Also see. Chance v. Board o f Examiners and Board o f Education

o f the City o f New York, 534 F.2d 993, 999 (2nd Cir. 1976) (District

court’s order modifying a layoff, or “excessing” plan, struck down, where

“there is no claim that defendant’s excessing practices are or have been

discriminatory”).

21 See, e.g.. Baker v. City o f Detroit, 483 F. Supp. 930 (E.D. Mich. 1979);

Bratton v. City o f Detroit. 704 F.2d 878 (6th Cir. 1983); NAACP v.

DPOA, 591 F. Supp. 1194, 1199 (E.D. Mich. 1984); NAAC P v. DPOA,

676 F. Supp. 790, 796 (E. D. Mich. 1988). The detailed findings in Baker

were based, in part, on City of Detroit’s detailed admissions of intentional

discrimination, but were buttressed by the independent findings of de

jure conduct made by the district judge in that case.

10

II.

The Opinion Below Conflicts with Landmark Cases

In This Court Concerning the Remedial Reach of

The Equal Protection Clause and 42 U.S.C. §1983

The Opinion below conflicts with numerous landmark rul

ings of this Court which have for more than thirty years provided

state and federal courts with direction in identifying and remedy

ing intentional, invidious, racial discrimination, including: Brown

v. Bd. o f Education, 349 U.S. 294 (Brown II);22 Louisiana v.

United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965);23 Green v. New Kent County

School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968);24 Swann v. Charlotte-Meck-

lenburgSchool Board, 402 U.S. 1 (1971 );25 Keyes v. School Dist.

22 In (Brown II), this Court said the vitality of the Constitutional principles

enacted in Brown v. Bd. o f Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954) (Brown I), should

not yield simply because of disagreement with them. While recognizing

the primary responsibility of school authorities for solving the problems

of racial discrimination in education, Brown I! instructed lower courts to

be guided by equitable principles in fashioning and effectuating decrees

designed to dismantle dual systems and guard against their continuing

vestigial effects.

23 In Louisiana v. United States, this Court said that the federal courts have

not just the right but the “duty to render a decree which will so far as

possible eliminate the discriminatory effects of the past as well as bar like

discrimination in the future.”

24 Though Louisiana v. United S tates was a voting rights case, Green v.

New Kent County School Board, a school desegregation case, imposed

the same duty upon an offending state actor as well as the federal courts

in remedying Constitutional violations:

“School boards . . . (under Brown II) were . . . charged with the

affirmative duty to take whatever steps might be necessary to con

vert to a unitary system in which racial discrimination would be

eliminated root and branch. The constitutional rights of negro chil

dren articulated in Brown I permit no less than this . . .

“The obligation of the district courts, as it has always been, is to assess

the effectiveness of a proposed plan in achieving desegregation.”

(emphasis added)

25 Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board o f Education further explicated

the duty of federal courts in cases involving remedies for Constitutional

violations, holding that:

No. I, Denver, 413 U.S. 189 (1973);26 Columbus Bd. o f Educ. v.

Penick, 443 U.S. 666 (1979);27 and, Dayton Bd. o f Educ. v.

Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526 (1979.28

In all of these cases, the Court was addressing remedies

where either de jure segregation had existed in violation of the

14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause (Green, Swann,

Keyes, Penick, Brinkman), or where racially discriminatory stat

utes violated the Fifteenth Amendment (Louisiana v. United

States).

This Court has repeatedly stressed the obligation of the

federal courts to assure that racial discrimination is effectively

eliminated, and to guard against those actions which might make

more difficult the task of elimination. The Opinion challenged by

this Petition completely disregarded the City of Detroit’s unmet

affirmative duty to dismantle, “root and branch”,29 the unconsti

tutional dual system created by its racially discriminatory

employment practices.

“The task is to correct. . . the condition that offends the

Constitution.”

26 In Keyes v. School District No. I . Denver, Colorado, the Court had held

that remoteness in time between the segregative intent and the actions

complained of does not make the actions less intentional when “segrega

tion resulting from those actions continues to exist.”

27 Columbus Board o f Education v. Penick held that:

“Each instance of a failure or refusal to fulfill this affirmative duty

continues the violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.”

28 In Dayton Board o f Education v. Brinkman, this Court held that:

“Part of the affirmative duty imposed by our cases, as we decided in

Wright v. Council o f City o f Emporia, 407 U.S. 451,92 S.Ct. 2196

(1972) is the obligation not to take any action that would impede the

process of disestablishing the dual system and its effects . . .

“The measure of the post Brown l conduct of a school board under

an unsatisfied duty to liquidate a dual system is the effectiveness, not

the purpose, of the actions decreasing or increasing the segregation

caused by the dual system.”

29 Green, supra.

1 2

The Opinion also conflicts in principle with decisions of this

Court concerning the scope of Title VII. On several occasions,

the Supreme Court has addressed the role that Title VII plays in

this nation’s effort to eradicate employment discrimination. Con

sistently, Title VII’s purpose has been defined as providing an

additional remedy for invidious employment discrimination. The

decisions of this Court have made it clear that the Congress did

not intend to force aggrieved employees to look to the provisions

of Title VII as their sole vehicle for attacking discriminatory

employment practices.30

By holding that the restrictions of §703(h) of Title VII must

be applied to an Equal Protection claim being prosecuted via

§1983, the Opinion below ignores that Petitioners have every

right, under the precedents of this Court, to pursue a §1983

claim in addition to, and wholly separate from, p. Title VII claim.

Thus, even if the Petitioners below had filed formal complaints

with the EEOC, they would not have been precluded from

making Equal Protection claims and pursuing them under § 1983.

That no such complaints were ever filed with the EEOC is an

30 In Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Company, 415 U.S. 36, 48-50 (1974),

this Court held that petitioner’s pursuit of a grievance through arbitra

tion under the collective bargaining agreement, resolved adversely to

him, did not preclude a suit against his employer under Title VII. In

discussing the origin and purposes of Title VII, the Court stated:

“Legislative enactments in this area have long evinced a general

intent to accord parallel or overlapping remedies against

discrimination . . .

“ Moreover, the legislative history of Title VII manifests a congres

sional intent to allow an individual to pursue independently his

rights under both Title VII and other applicable state and federal

statutes. The clear inference is that Title VI1 was designed to

supplement, rather than supplant, existing laws and institutions

relating to employment discrimination.” (emphasis added)

In Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S. 454, 459-462

(1975), the Court said:

“Despite Title VII’s range, . . . the aggrieved individual clearly is not

deprived of other remedies he possesses and is not limited to Title VII

in his search for relief.”

13

absolute jurisdictional bar to invoking the statutory remedies,

and limitations, built into Title VII.

The Opinion below does exactly what this Court has warned

against in its decisions on the scope of Title VII. It holds that

plaintiffs’ employment discrimination remedies are necessarily

defined by Title VII, whether the plaintiff has chosen to bring his

suit under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, §1981 of the

Civil Rights Act of 1870, or §1983 of the Civil Rights Act of

1871 to vindicate a Constitutional or federal right. In so holding,

the Court below has ignored this Court’s repeated holdings that

Title VII is only a supplement to, not a replacement for, the pre

existing remedies for employment discrimination.3'

The Opinion held that the doctrine of in pari materia

dictates §703(h)’s application here. The court reasoned that

§703(h) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, being a later and more

specific statute, must control the earlier and more general provi

sions of §1981 and §1983. NAACP v. DPOA, 900 F.2d, @ 911-

912. Petitioners believe this reasoning conflicts with the prior

holdings of this Court. The doctrine of in pari materia applies

only when two statutes conflict; it has no applicability where, as

in this case, a mere statute collides with the Constitution.31 32

31 Supporting Petitioners’ request for review is the recognition by the Court

of Appeals that:

“the Supreme Court has recognized that Congress did not, with the

passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and its 1972 Amendments,

intend to repeal existing statutes in the civil rights field, or make

Title VII the exclusive remedy in all employment discrimination

contexts”. NAAC P v. DPOA, 900 F.2d, @ 9 1 3 ___

“the Supreme Court has yet to address directly the relationship

between §703(h) and the earlier Civil Rights Statutes”

Despite these disclaimers, the Court of Appeals proceeded to misapply

the doctrine of in pari materia as its rationale for holding that Title

VII strictures apply to 1981 claims even where no Title VII complaints

were filed, and no Title VII claims were specifically pleaded below.

32 The court of appeals Opinion simply ignores the fact that the violation

here was a constitutional one, and that 42 U.S.C. §1983 is simply a

procedural device by which plaintiffs may prosecute violations of the

federal Constitution and statutes. As discussed supra, the actual violation

14

Thus, even though an Equal Protection Clause violation

might be forced to take on the appearance of a statute because it

is prosecuted pursuant to §1983, a federal court need not look to

Title VII for enforcement power because the precedents of this

Court have already provided it with such power. Equal Protec

tion remedies are naturally broader than those of Title VII,

which has a more limited role in the fight against invidious

discrimination.

In McDonnell-Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 800

(1973) the purpose of Title VII was held to be:

“to assure equality of employment opportunities and to

eliminate those discriminatory practices and devices which

have fostered racially stratified job environments to the

disadvantage of minority citizens.”

To achieve this result, the Congress not only made intention

ally discriminatory employment conduct a violation of Title VII,

but it also proscribed neutral employment practices with a dis

criminatory effect.™ §703(h) was added to make clear that not

all seniority systems were violative of Title VII, under the ratio

nale of Griggs v. Duke Power, §401 U.S. 424 (1971). The Equal

Protection Clause, on the other hand, has the larger, more

important goal of eradicating discrimination any time the state

actor is purposefully discriminating on the basis, inter alia, of *

alleged by Petitioners and found by District Judge Gilmore was that the

City had intentionally discriminated against its Black police officers, in

violation of the Equal Protection Clause. As such, the Opinion at issue in

this Petition erroneously applied principles of in pari materia. Further

more, the doctrine of in pari materia is also inapplicable because there is

no conflict between Equal Protection remedies and §703(h) of Title VII.

This Court stated, with regard to specific statutes governing more general

ones:

“The courts are not at liberty to pick and choose among congres

sional enactments, and when two statutes are capable of coexistence,

it is the duty of the courts, absent a clearly expressed congressional

intention to the contrary, to regard each as effective.” Morton v.

Mancari, 417 U.S. 535, 552 (1974)

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 350 (1977)33

15

race.34 The Equal Protection Clause is not limited to simply

employment discrimination, while Title VII cannot be applied to

any other form of discrimination.

The two provisions thus serve very different purposes. As a

result of the heightened importance of eradicating intentional

discrimination, once it has been found, the remedial scheme this

Court devised for violations of the Equal Protection Clause is one

of broad, flexible remedies, as discussed above. Because it deals

only with intentional discrimination, the Equal Protection Clause

has no need for the limitations placed on Title VII remedies. The

remedies under both these provisions are perfectly capable of

coexistence. As such, they are not subject to being read in pari

materia.

III.

The Sixth Circuit’s Opinion Raises Important Issues

Re: 42 U.S.C. §1983 that Need Resolution by this Court

The court of appeals below held that a federal statute,

§703(h) of Title VII, precludes a federal district court from

imposing an Equal Protection remedy which the Supreme Court

of the United States has held it not only has the power, but the

duty, to impose. The decision raises issues of Supremacy and

Constitutional rights which are of vital importance to other

circuits as well as this Court.

In Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cranch 137 (1803), this Court

established that the Constitution is the paramount law of the

land, and that it is this Court’s duty to interpret the Constitution.

It follows that even a congressional enactment does not have the

power to put constraints on this Court’s constitutional remedies.

The Opinion below, by holding that a constitutional claim being

pursued by means of 42 U.S.C. §1983 is limited by §703(h), has

attempted to affix just such constraints on the remedies this

Court has fashioned for violations of the 14th Amendment’s

Equal Protection Clause.

34 Washington v. Davis. 626 U.S. 229 (1976).

16

In Louisiana v. United States, supra, this Court held that

the district court had a duty to render a decree that would

eliminate the effects of past discrimination as well as bar future

discrimination. Louisiana v. U.S., 380 U.S., @ 154. In Missouri

v. Jenkins, 110S. Ct. 1651, 109 L. Ed.2d 31, 58 U.S.L.W. 4480

(1990), this Court recently made clear that neither the district

court’s duty nor its power were suspended, either because its

order to remedy constitutional violations might cause fiscal hard

ship, or because it might require the state to make payments

contrary to state law and otherwise prohibited by the Tenth

Amendment.35

35 In Missouri v. Jenkins , this Court rejected the argument that the district

court order impermissibly ignored state laws which governed the amount

and methods by which funds could be raised to meet otherwise valid

obligations:

“ Here, the KCMSD may be ordered to levy taxes despite statutory

limitations on its authority in order to compel the discharge of an

obligation imposed on KCMSD by the Fourteenth Amendment. To

hold otherwise would fail to take account of the obligations of local

governments, under the Supremacy Clause, to fulfill the require

ments that the Constitution imposes on them. . . . '[I]f a state-

imposed limitation on a school authority’s discretion operates to

inhibit or obstruct the operation of a unitary school system or

impede the disestablishing of a dual school system, it must fall; state

policy must give way when it operates to hinder vindication of

federal constitutional guarantees.’ North Carolina S ta te Bd. o f

Education v. Swann , 402 U.S. 43, 45 (1971).”

This Court also swept aside the state’s argument that the 10th Amend

ment shielded it from having to make desegregation payments ordered by

the district court:

“The Tenth Amendment’s reservation of nondelegated powers to the

states is not implicated by a federal court judgment enforcing the

express prohibitions of unlawful state conduct enacted by the Four

teenth Amendment.”

It seems obvious that, if neither state laws nor the Tenth Amendment are

permitted to block a district court’s remedial orders to repair constitu

tional violations in Kansas City, then the provisions of §703(h) cannot be

distorted as below to effect a barrier to prevent the district court’s

remedial order from reaching the continuing vestiges of intentional,

unconstitutional, racial discrimination in Detroit.

17

The Sixth Circuit’s Opinion, by holding that a federal stat

ute may control and shape the contours of a constitutional right,

is an effort at rewriting the system of checks and balances set

forth as early as Marbury v. Madison, supra.36

The Opinion below raises compelling issues regarding the

interpretation of §703(h) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The

Court below has given that Section a meaning that neither this

Court nor Congress ever intended.

As stated in Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 344

(1977):

“The unmistakable purpose of 703(h) was to make

clear that the routine application of a bona fide senior

ity system would not be unlawful under Title VII. As

the legislative history shows, this was the intended

36 This Court has had previous reason to determine the breadth of its

mandate to remedy Equal Protection violations when it seemingly con

flicted with a federal statute. In Drummond v. Acree, 409 U.S. 1228

(1972), a district court order adopting a plan to desegregate 29 elemen

tary schools in August was challenged as conflicting with §803 of the

Education Amendments of 1972. This statute purported to postpone

transportation of any student for the purpose of achieving racial balance,

until all appeals had been exhausted. The Court found that, since the

district court order to transport children was part of a proper plan to

remedy 14th Amendment violations, citing Swann , supra, the statute

must have meant to refer only to de facto segregation which did not

violate the Equal Protection Clause:

“The statute requires that the elfectiveness of a district court order

be postponed pending appeal only if the order requires the 'transfer

or transportation’ of students 'for the purposes of achieving a racial

balance among students with respect to race.’ It does not purport to

block all desegregation orders which require the transportation of

students.” Drummond , at 1230.

To reach that result, this Court reasoned that §803 could not be read to

render meaningless the mandate in Swann whenever transportation was

involved in the remedy.

Similarly, the federal statute in this case, §703(h), cannot be read to

render meaningless the affirmative duty to eliminate intentional employ

ment discrimination whenever the prevention of layoffs is involved.

18

result even where the employer’s pre-Act discrimina

tion resulted in whites having greater existing seniority

rights than Negroes.”

The “unmistakable purpose” has been reiterated by this

Court on several later occasions, when plaintiffs complained that

Title VII violations should be remedied by methods abridging

seniority rights.37 As the Sixth Circuit points out, §703(h) has

also been applied to protect seniority systems where the underly

ing violation was brought under 1981. However, this is still a

federal statutory right, as distinguished from a constitutional

right. The cases hold only that employers need not go so far as to

abrogate a valid seniority system in order to comply with Title

VII.

The Opinion below distorts this line of cases, asserting that

§703(h) of Title VII has established “an exception to liability for

employment discrimination based on race.” NAACP v. DPOA,

900 F.2d, @ 907. By applying this distorted notion, the Opinion

interprets its “exception” as applying to constitutional violations

as well as to other practices defined by statute as racially discrim

inatory. The court below has taken what Congress and this Court

created as a shield, to protect seniority systems from being

viewed as per se Title VII violations, and transmogrified it into a

sword, which exempts from liability all job discrimination, even

if intentional, so long as there is a seniority system in place. Yet,

neither Congress nor this Court ever suggested, much less held,

that §703(h) could immunize intentional racial discrimination in

employment from constitutional remedy.

37 See, Trans World Airlines, ltic. v. Hardison, 432 U.S. 63 (1977),

(Employer not required to abrogate seniority system of a collective

bargaining agreement in order to remedy violation of 703(h)(1) of the

Act); American Tobacco Company v. Patterson, 456 U.S. 63 (1982),

(Employer need not depart from seniority system to remedy seniority,

promotion, and job classification practices which violated Title VII); and

Firefighters Local Union No. 1784 v. Stotts, 467 U.S. 561, 582-583, and

fn 16 (1984) (No departure from seniority system required to comply

with Title VII remedial order.)

19

IV.

The Opinion Below on Union Liability Conflicts

In Principle with Applicable Rulings of this Court

District Court Findings On DPOA Liability

The district court’s 1984 decision concluded that the DPOA

had violated its Duty of Fair Representation. This conclusion was

based on the DPOA’s “failure to adequately represent the inter

ests of its black members in the layoffs of 1979 and 1980.”

Based on the full trial record before it, including the

thousands of trial transcript pages and more than one dozen

witnesses, the district court made extensive findings about the

DPOA’s racially discriminatory conduct. Stating that

“The DPOA’s breach of the duty of fair representation

flows not merely from any reliance upon a seniority

system, or a simple refusal to make concessions in the

interests of minorities. The DPOA’s liability is pre

mised on more than this. . . . ”

the district court found “A history of racial hostility and indiffer

ence to the rights and needs of black officers”; a “total absence of

black representation in the leadership levels of the union”;

“totally perfunctory and passive behavior of the union leader

ship” in the face of layoffs which would wipe out 50% of the

DPOA’s black membership; a “present day failure to make any

serious efforts to assist these black officers”; and, “A history of

concessions and prompt union action to avert layoffs in 1975 and

1981 when the jobs of white officers were at stake.”

On this basis, the district court concluded that it was “only

concerned with activity that is arbitrary, racially discriminatory,

and not in good faith, and this court finds that, in its representa

tion of its black members, the DPOA’s perfunctory and passive

behavior in 1979 and 1980 breached the duty of fair

representation.”38

38 NAACP v. DPOA, 591 F. Supp. 1194 (E.D. Mich. 1984).

2 0

Having concluded that the DPOA had breached its Duty of

Fair Representation, and that the scope of relief for that breach

was essentially the same as would be available for violation of 42

U.S.C. 1981, the district court said that it had “no reason to

consider the claim under 42 U.S.C. §1981, in light of the result

reached here.”39

In the first appeal, the court of appeals reversed the district

court ruling on the Duty of Fair Representation, on the grounds

that layoffs were not mandatory subjects of bargaining pursuant

to Local 1277, AFSCM E v. City o f Centerline, 414 Mich. 642,

685, 327 NW 2d 822, 831 asserting that no liability could be

found for DPOA failure to act on issues as to which it was not

required to act in the first place.40 Noting, however, that the

district court had explicitly declined to rule on the claim under

42 U.S.C. §1981, the court of appeals remanded the matter with

instructions that Plaintiffs be permitted to prosecute this claim.

NAACP v. DPOA, 821 F.2d 328 (6th Cir. 1988).

On remand, the district court, denied the DPOA’s motion

for summary judgment, NAACP v. DPOA, 676 F. Supp., @ 796-

97, noting that:

“ [it is] impossible to fairly read this court’s findings

concerning the DPOA’s history and conduct before,

during, and after the 1979 and 1980 layoffs, without

concluding that the DPOA was indeed guilty of inten

tional discrimination. . . . ”

39 In its decision awarding fees to Plaintiffs, NAAC P v. DPOA, 629 F. Supp.

1173, 1180 (E.D. Mich. 1985), the district court further addressed the

nature of the claim against the DPOA when it said that:

“The court did not reach plaintiff’s claim under §1981 because that

claim was mooted by the finding of the breach of the duty of fair

representation. Plaintiffs’ §1981 claim and duty of fair representa

tion claim arose out of a common nucleus of operative facts, i.e., the

DPOA’s action as a whole with regard to the 1979 and 1980 layoffs

of black officers.”

40 NAACP v. DPOA, 821 F.2d 328, 332 (6th Cir. 1987). The court also

based its reversal on its conclusion that the district court had made no

finding of improper motivation in the bargaining which produced the

seniority provision of the collective bargaining agreement.

21

The court held that its findings “with respect to the violation

of the Duty of Fair Representation were tantamount to a finding

of intentional discrimination under 42 U.S.C. §1981 when it

awarded attorneys fees and costs against the DPOA” . NAACP v.

DPOA, 676 F. Supp., @ 797.

On appeal of the mootness decision, the court agreed with

Petitioners that the district court erred when it dismissed the case

against the DPOA on mootness grounds:

“ First, the fact that the district court has accomplished

the goals of its own injunctive order, later reversed as

having no basis in law, dees not render a case moot.

Second, assuming for the moment that the plaintiffs

had viable §1983 claims against the city or the union

for the 1979-1980 layoffs, the appropriate remedy

would require more than mere recall and retroactive

seniority. It would include the determination of other

benefits such as back pay and out of pocket costs

incurred by the laid off police officers . . . Third, minor

ity police officers' majority membership in the union

does not 'without more’ translate into the ability to

protect themselves against discriminatory action by the

leadership. Rather, their ability to protect themselves

depends on factors such as the union’s organizational

structure and could not be evaluated in the abstract

without further inquiry. In light of these factors includ

ing the Supreme Court’s holding in Stotts , we conclude

that the controversy was not moot.” NAACP v. DPOA,

900 F.2d, @ 906.

The Opinion's Dismissal o f the 1981 Claim Conflicts With

This Court’s Holding in Johnson v. Railway Express

Agency

Just as it had concluded that the City was immunized from

challenge via §1983 by operation of §703(h) of Title VII, the

court of appeals held that the §1981 claim against the DPOA

was barred by §703(h). NAACP v. DPOA, 900 F.2d, @ 912,

fn. 10.

2 2

Petitioners’ discussion of, and authorities cited concerning,

the inapplicability of the doctrine of in pari materia to Title

V11/§ 1983 claims, applies equally to Title V11/§ 1981 claims.

The court below claims support for its position from this Court

and other Circuit Courts, mistakenly citing Johnson v. Railway

Express Agency, 421 U.S. 454 (1975). However, as this Court

found in Johnson, 424 U.S., @ 459-462, the Opinion below

conflicts with Congressional intent, with respect to the ability of

claims under Title VII to coexist with those brought under

§ 1981.41

The Opinion below cited Brown v. G.S.A, 425 U.S. 820, 828

(1976), for the proposition that this Court has prevented “artful

pleading to avoid both the requirements and consequences of a

Title VII action by any other name.” Even a cursory reading of

Brown v. G.S.A., however, underscores that it was inapposite to

the case below, and miscited by the court to support its conclu

sions, when it more properly should be read to support the

position of the Petitioners.41 42 The Opinion below similarly mis

construes the holdings of this Court in Great American Federal

Savings & Loan Association v. Novotny, 442 U.S. 366, 375-76

41 A reading of Johnson, reveals that it explicitly allirmed the separate

nature of §1981 claims and those brought under Title VII. Johnson held

that tiling a Title VII charge does not toll the statute of limitations for

claims brought under §1981.

42 Brown v. G .S.A. addressed the question of whether federal employees

were limited to Title VII as the vehicle for redressing claims of invidious

employment discrimination. After analyzing the legislative history of the

1972 amendments to Title VII which extended coverage to federal

employment, this Court concluded that, since there were no prior federal

statutes providing such employment discrimination relief to federal

employees, the Congress must have intended Title VII to be the exclusive

remedy for federal employee claims of workplace discrimination. The

Court specifically contrasts the situation faced by federal employees with

that prevailing with respect to private employees and to other public

employees. The Court found statutory remedies which pre-existed Title

VII as to the non-federal employees, and specilically noted that the

Congressional intent, when Title VII coverage was extended to these

workers, was to add a new and independent basis to these pre-existing

remedies.

23

(1979),43 and of the 5th Circuit in Watkins v. United Steel

Workers, 516 F.2d 41, 49-50 (5th Cir. 1975).44

The Opinion also wrongly notes, in footnote 10, that the

Supreme Court’s recent decision in Patterson v. McLean Credit

Union, 109 S. Ct. 2263 (1989), would likely require dismissal of

the case against the DPOA, asserting that the union conduct

challenged below is “post-formation” conduct which Patterson

said was not vulnerable to §1981.45

In Novotny, this Court held that §1985(3) may not be read to provide a

substantive right, per se, but rather is a vehicle for addressing conspiracy

to violate the substantive rights created by other statutes. In the instant

case, however, the Court of Appeals below ignored the independent

substantive rights which are created by §1981.

44 In Watkins, the 5th Circuit held that where the fact and vestigial effects

of past hiring discrimination had ceased for 10 years before the claim

challenging a current layoff was brought, the employer could permissibly

use a long-established seniority system for determining who would be laid

off and/or rehired, without fear of violating cither Title VII or §1981.

This contrasts sharply with the instant case, in which the district court

explicitly found that vestigial effects of the prior explicit racially discrim

inatory hiring had not yet been extirpated at the time of the layoffs here

challenged. Watkins explicitly held that the failure of Title VII to

“proscribe an employment practice docs not foreclose an attack under 42

U.S.C. 1981”, and specifically refused to make a finding as to whether or

not §703(h) applied to 42 U.S.C. §1981, on the ground that the absence

of discrimination made irrelevant any applicability §703(h) might other

wise have.

45 The opinion below directly conflicts with this Court’s decision in Patter

son, with respect to union misconduct. Patterson is properly quoted for

the proposition that:

racial harassment relating to conditions of employment is not

actionable under §1981 because that provision does not apply to

conduct which occurs after the formation of a contract and which

does not interfere with the right to enforce established contract

obligations.”

However, the Court of Appeals failed to note that Patterson also held:

“ It [the phrase about enforcing contracts] also covers wholly private

efforts to impede access to the courts or obstruct non-judicial meth

ods of adjudicating disputes about the force of binding obligations,

24

The Duty o f Fair Representation Claim

The Opinion’s resolution of the Duty of Fair Representation

issue provides an additional basis for granting the instant Peti

tion for Certiorari.

In the original Duty of Fair Representation decision by this

Court, Steel v. L & N Railway, 323 U.S. 192 (1944), the union

was found liable for having permitted an employer to set up

separate black and white bargaining units, with provisions

requiring that any lay off would necessarily include blacks before

any whites could be reached. While this Court has consistently

affirmed the wide latitude unions have in deciding which com

plaints to grieve, Hines v. Anchor Motor Freight, Inc., 424 U.S.

554 (1976), this Court and other federal courts have not hesi

tated to hold liable union conduct which expediently sacrificed

minority members in order to protect white members.46

Citing Local 1277 AFSCM E v. City o f Centerline, 414

Mich. 642, 665 (1982), the Opinion held that the DPOA could

not legally be found liable for a failure of its Duty of Fair

as well as discrimination by private entities, such as labor unions, in

enforcing the terms of a contract. Following this principle and

consistent with our holding in Runyon that 1981 applies to private

conduct, we have held that certain private entities such as labor

unions, which bear explicit responsibilities to process grievances,

press claims, and represent members in disputes over the terms of

binding obligations that run from the employer to the employee, are

subject to liability under §1981 for racial discrimination in the

enforcement of labor contracts. See, Goodman v. Luckens S teel Co.,

482 U.S. 656 (1987).”

Patterson, thus, rejected the notion that racially-motivated union miscon

duct is immunized from attack under §1981. Goodman v. Luckens Steel,

supra, squarely contradicts the Court of Appeals reasoning below, hold

ing that §1981 may properly be used to prosecute a racial discrimination

claim against a union which ignored and failed to pursue adverse racial

treatment by an employer.

46 See, e.g., Vaca v. Sipes, 386 U.S. 171 (1967); Em m anuel v. Omaha

Carpenters District Council. 535 F.2d 420 (8th Cir. 1976); Jennings v.

American Postal Workers Union, 672 F.2d 712 (8th Cir. 1982); Wyatt v.

Interstate & Ocean Transport Co., 623 F.2d 888 (4th Cir. 1980); Alvey

v. General Electric, 622 F.2d 1279 (7th Cir. 1980).

25

Representation, because an employer’s decision to effect a lay off

is a permissive subject of bargaining, under Michigan law. A

reading of Local 1277, however, makes clear that the Opinion

below misconstrued it as badly as it did the holdings of this Court

discussed above. Local 1277 stands for the proposition that, while

the initial decision to lay off is not one over which the employer

must bargain, the impact of any such layoff is a mandatory

subject of bargaining.

The Michigan Supreme Court held in Local 1277, at p. 664,

the impact of the layoff

“on the safety of the remaining forces, seniority rights,

‘bump’ rights, and even the motive behind the layoff

decisions are all subjects of the collective bargaining

agreement. Thus, we do not foreclose bargaining or the

issuance of an arbitration award covering such issues.

We only hold that the initial decision is a management

prerogative and that the arbitration panel cannot man

date a clause on the initial layoff decision.”47

47 The Petitioners below challenged, precisely, the impact of the 1979 and