Richards v Vera Appeal Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1994

34 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Richards v Vera Appeal Jurisdictional Statement, 1994. 2845a031-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0bd15e5f-2b96-415e-ab74-2033614ad1b4/richards-v-vera-appeal-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

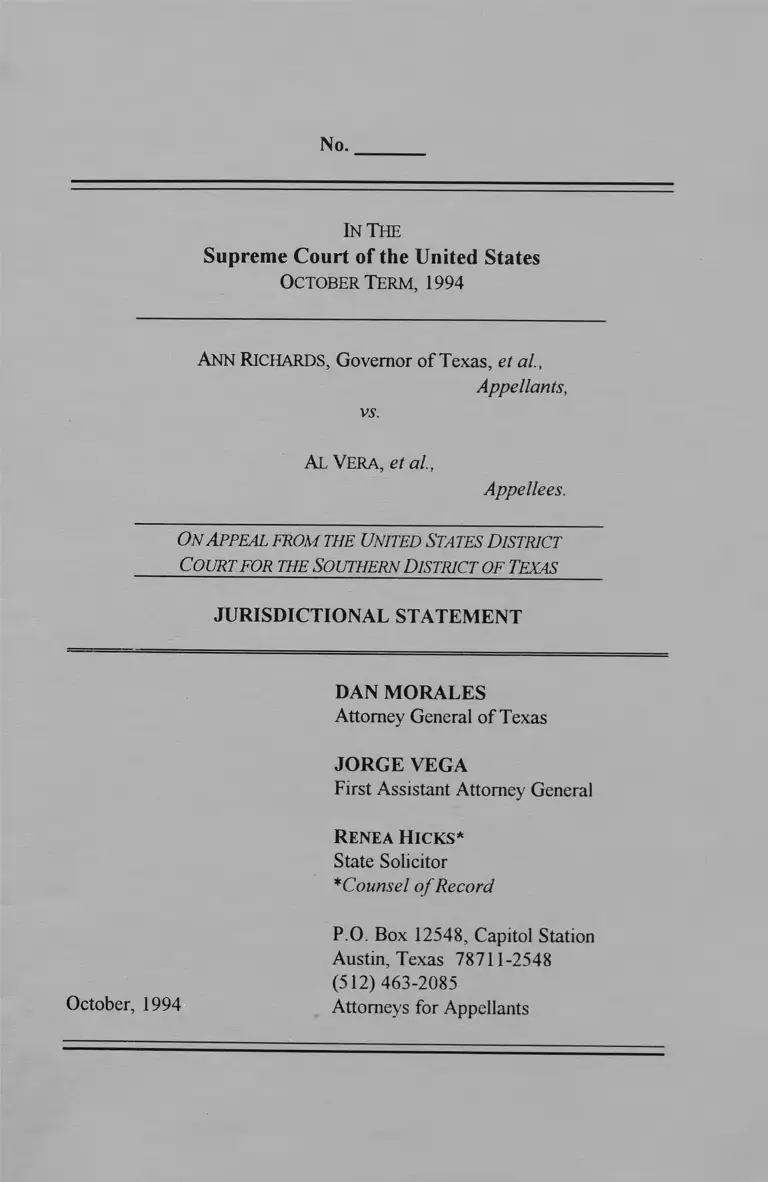

No.

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term , 1994

ANN RICHARDS, Governor of Texas, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

Al Vera, et al.,

Appellees.

On A p p e a l f r o m t h e Un it e d S t a t e s D is t r ic t

C o u r t f o r t h e S o u t h e r n D is t r ic t o f Te x a s

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

DAN MORALES

Attorney General of Texas

JORGE VEGA

First Assistant Attorney General

Renea H ic k s* *

State Solicitor

*Counsel o f Record

P.O. Box 12548, Capitol Station

Austin, Texas 78711-2548

(512)463-2085

October, 1994 Attorneys for Appellants

1

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether the configurations of three Texas minority opportunity

districts created to comply with the Voting Rights Act are explainable on

grounds other than race, thereby making strict scrutiny improper, when

parallel, more compactly shaped minority opportunity districts

demonstrably could have been drawn in the same vicinity but were not for

non-racial state policy reasons?

2. Whether narrow tailoring to meet the compelling interest of

compliance with the Voting Rights Act requires Texas to set aside other

non-racial traditional districting principles, ignore politics, and draw only

those minority opportunity districts conforming to the most idealized

possible version of compact shape?

3. Whether Texas congressional districts 18, 29, and 30 — all

localized, essentially single-county urban districts and all minority

opportunity districts under the Voting Rights Act - fall outside Shaw v.

Reno’s threshold test of bizarreness?

4. Whether the statewide redistricting plan creating Texas

congressional districts 18, 29, and 30 is consistent with the Equal

Protection Clause as interpreted in Shaw v. Reno?

5. Whether a consistent state tradition of incumbency protection in

congressional redistricting is within the category of traditional districting

principles which make strict scrutiny inappropriate under Shaw v. Reno if

observed in a redistricting plan?

6. Whether the injury-in-fact element of constitutional standing is

satisfied in an equal protection redistricting case by plaintiffs who do not

claim vote dilution, who are not the object of invidious discrimination by

the challenged plan, and whose only identified harm is not living in a state

whose congressional redistricting plan is designed wholly without race

consciousness?

7. Protectively, based on a cautious interpretation o f remedial

order language, whether a district court exceeds its equitable powers by

ordering a state legislature to enact remedial legislation by a specific date?

11

LIST OF PARTIES

Plaintiffs

A1 Vera

Edward Chen

Pauline Orcutt

Edward Blum

Kenneth Powers

Barbara L. Thomas

Defendants

Ann Richards, Governor of Texas

Bob Bullock, Lieutenant Governor of Texas

Pete Laney, Speaker of the Texas House of Representatives

Dan Morales, Attorney General of Texas

Ron Kirk, Secretary of State of Texas

Defendant-Intervenors

United States

Rev. William Lawson

Zollie Scales, Jr.

Rev. Jew Don Boney

Deloyd T. Parker

Dewan Perry

Rev. Caesar Clark

League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) of Texas

Robert Reyes

Angie Garcia

Robert Anguiano, Sr.

Dalia Robles

Nicolas Dominguez

Oscar T. Garcia

Ramiro Gamboa

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

QUESTIONS PRESENTED............................................................... j

LIST OF PARTIES....................................................... ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS................................................................... iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.............................................................. v

OPINION BELOW.............................................................................. 1

JURISDICTION.................................................................................. i

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED 2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE.......................................................... 2

THE QUESTIONS PRESENTED ARE SUBSTANTIAL.............. 12

I. Whether the lower court erred: (i) in holding that proof that more

compact, regularly shaped minority opportunity districts could

have been drawn but were not because of non-racial politics is

irrelevant to demonstrating that race is not the sole or overriding

reason for the irregular shape of minority opportunity districts;

and (ii) in holding that, on the contrary, such proof demonstrates

an inability to meet the narrow tailoring requirement of strict

scrutiny?................................................................................. 13

II. Whether, in a statewide redistricting, localized, single-county

urban minority opportunity districts with a lesser degree of single

race dominance than every other district in the state can be

deemed so facially irregular that Shaw's threshold test is

satisfied?................................................................................. 15

III. Whether an unquestioned state tradition of incumbency protection

(and the related tradition of furthering senatorial aspirations) may

be judicially excluded from the realm of traditional districting

principles which, if followed, overcome a Shaw challenge? . 17

IV. Whether the lower court erred in applying Shaw to invalidate the

three minority opportunity districts?..................................... 19

IV

V. Whether plaintiffs who do not claim harm from a diluted vote,

who have not been invidiously discriminated against, and who

otherwise point to no concrete injury have standing to press an

equal protection claim?.......................................................... 20

VI. Whether the court exceeded its equitable powers and encroached

on the state’s domain by exposing the legislature and its members

to possible civil contempt and impermissibly confining the state’s

remedial options to formal legislative enactments (protectively,

based on a cautious interpretation of the lower court’s order)? 23

CONCLUSION................................................................................... 23

ATTACHMENTS A and B

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Page(s)

Allen v. Wright, 468 U.S. 737 (1984) ....................... 21

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962) ......................... 22

Brown v. Board o f Education, 347U S 483

(1954) 22

Burns v. Richardson, 384 U.S. 73 (1966) ................ 23

Compare Palmore v. Sidoti, 466 U.S. 429 (1984) .... 22

DeWitt v. Wilson, 856 F.Supp. 1409

(E D. Cal. 1994) 15

Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651 (1974) .................. 20

Growe v. Emison, 113 S.Ct. 1075 (1993) ................. 14

Hays v. Louisiana, 1994 WL 477159

(W.D. La. July 29, 1994) .................................... 16

Johnson v. Miller, 1994 WL 506780

(S.D. Ga. Sept. 12, 1994) ................................... 15

Karcher v. Daggett, 462 U.S. 725 (1983) ................ 18

Lujan v. Defenders o f Wildlife, 112 S.Ct. 2130

(1992) 21

McDaniel v. Sanchez, 452 U.S. 130 (1981) ............. 23

Northeastern Florida Chapter o f the Associated

General Contractors o f America v. City o f

Jacksonville, 113 S.Ct. 2297 (1993) 21

Regents o f the University o f California v. Bakke,

438 U.S. 265 (1978) 21

Shaw v. Reno, 113 S.Ct. 2816 (1993) .......................passim

Spallone v. United States, 493 U.S. 625 (1990) 23

Strauderv. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1879) 21

Terrazas v. Slagle, 789 F.Supp. 828

(W.D. Tex. 1991) 3

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986) .............. 14

Worth v. Seldin, 422 U.S. 490 (1975) ............. 21

White v. Weiser, 412 U.S. 783 (1973) ............. 18

Wise v. Lipscomb, 437 U.S. 535 (1978) .................... 23

VI

Statutes Pagels)

28U.S.C. § 1253 ...................................................... 2

42 U.S.C. § 1973 ...................................................... 2

42 U.S.C. § 1973c ...................................................... 2

Ch. 7, 72nd Tex. Leg., 2nd C.S. (Aug. 29, 1991) ......... 2

Miscellaneous

Karlan, All Over the Map: The Supreme Court's

Voting Rights Trilogy, 1993 Sup.Ct.Rev. 245 .... 20

No.

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1994

ANN RICHARDS, Governor of Texas, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

Al Vera, et ah,

Appellees.

On A p p e a l f r o m t h e Un it e d S t a t e s D is t r ic t

C o u r t f o r t h e S o u t h e r n D is t r ic t o f Te x a s

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

The Governor, Lieutenant Governor, Speaker of the House,

Attorney General, and Secretary of the State of Texas (Ann Richards,

Bob Bullock, Pete Laney, Dan Morales, and Ron Kirk, collectively termed

“the state”) appeal from the injunction of the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Texas, prohibiting use of the state’s 1991

congressional redistricting plan for the 1996 elections.

OPINION BELOW

The unreported opinion of the three-judge district court is

reproduced in the separately bound appendix to this jurisdictional

statement (“J.S. A pp”) at 5a-84a.

JURISDICTION

The opinion declaring the unconstitutionality of three Texas

congressional districts was entered on August 17, 1994. J.S. App. 5a-

84a. The subsequent remedial order of the district court, permitting use of

the current congressional redistricting plan to complete the 1994 elections

but enjoining its use for the 1996 elections, was entered on September 2,

1994, and amended nunc pro tunc on September 14, 1994. J.S. App. la-

2

4a. The state’s notice of appeal was filed on September 22, 1994. J.S.

App. 85a. The Court has jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1253.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution provides that “[N]o State shall . . . deny to any

person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” The

relevant federal statutory provisions are sections 2 and 5 of the Voting

Rights Act of 1965 as amended, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1973, 1973c, the pertinent

parts of which are reproduced at J.S. App. 87a-88a. The state statute

creating the congressional redistricting plan at issue is Ch. 7, 72nd Tex.

Leg., 2nd C.S. (Aug. 29, 1991).

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

HB1 ’s enactment and the first litigation wave

The national reapportionment of Congress following the 1990

census increased the number of Texas congressional seats from twenty-

seven to thirty. In a second called session in the summer of 1991, the

overwhelmingly white Texas legislature (the House is 78% white, the

Senate, 77%) then enacted a congressional redistricting plan known as

HB1, and the Governor signed it on August 29, 1991.

HB1 created two black and seven Hispanic opportunity districts

under the Voting Rights Act. Black opportunity districts constitute 7% of

the Texas congressional seats, while the black population in Texas equals

12% of Texas’s nearly seventeen million people. Hispanic opportunity

districts constitute 23% of the Texas congressional seats, and the

Hispanic population in Texas is 23% of the total population.1 The

national body ~ the 103rd Congress of the United States House of

Representatives — of which the Texas congressional delegation is but a

part is comprised of 8.7% black members and 3.9% Hispanic members

St. Ex. 73 f2.

l Five members (17%) of the Texas congressional delegation are Hispanic.

3

Because HB1 established precise mathematical equality -

566,217 people each — among the districts, it was insulated from any

possible one person, one vote constitutional challenge under the Equal

Protection Clause. It cleared the hurdle of section 5 of the Voting Rights

Act when it was administratively precleared by the Department of Justice

on November 18, 1991.

Republican plaintiffs, however, did challenge HB1 as violative of

the racial antidiscrimination prohibitions of the Equal Protection Clause

and section 2 of the Voting Rights Act and of the partisan gerrymandering

prohibition of the Equal Protection Clause. All these challenges failed

before a three-judge federal court, both at the preliminary injunction phase

and upon entry of summary judgment for the state. See Terrazas v.

Slagle, 789 F.Supp. 828, 833-35 (W.D. Tex. 1991), and 821 F Supp

1162, 1172-75 (W.D. Tex. 1993).

Shaw-Aa.veii litigation

Successfully clearing three different equal protection hurdles and

two statutory voting rights hurdles did not insulate the state’s 1991

congressional plan from further constitutional challenge. In late January

of 1994, following the Court’s decision in Shaw v. Reno, 113 S.Ct. 2816

(1993), another set of Republican plaintiffs challenged HB1. When the

case went to trial only five months later, no vote dilution claims remained;

the challenge was premised solely on the Equal Protection Clause as

framed under Shaw and was leveled at twenty-four of the thirty districts.

The three-judge district court sustained the Shaw challenge as to

three districts (CDs 18, 29, and 30), rejected it as to the other twenty-one

districts, and ordered the Texas legislature to come back with a remedial

congressional plan by March 15, 1995 (while letting the 1994

congressional elections be completed under HB1). This appeal is of the

district court s declaration that CDs 18, 29, and 30 are unconstitutional

and the associated injunction against using HB1 for Texas’s 1996

congressional elections.

4

Targeted minority opportunity districts

Each invalidated district is a minority opportunity district

originally conceived to comply with sections 2 and 5 of the Voting Rights

Act, Two of the districts (CDs 18 and 29) lie wholly within Harris

County in the Houston metropolitan area. The other district (CD 30) lies

wholly within the Dallas metropolitan area (known as the Metroplex) and

nearly 99% within the single county of Dallas.2 The longest axis for each

of these districts is 39 miles for CD 18, 43 miles for CD 29, and 42 miles

for CD 30. All parts of CDs 18 and 29 may be visited in any direction in

less than one hour; CD 30 is similarly accessible. Each district is served

by a single television, newspaper, and job market.

These three localized urban districts are highly integrated racially.

In fact, they are the three Texas districts least dominated by any single

racial voter group. Each of the 27 other Texas districts has a higher

voting age percentage of some racial group than the three invalidated as

the product of racial gerrymandering. In the face of this undisputed fact,

the district court nonetheless characterized the three districts’ makeup as

“exclusively racial.” J.S. App. 76a.

Two of them (CD 18 and 30) have no racial majority in voting

age population, with CD 18 having a plurality of 48.6% black voting age

population and CD 30, 47.1%. Dr. Chandler Davidson explained that CD

30 has the smallest black population of any of the seventeen black

opportunity districts in the eleven-state South. CD 29 has an Hispanic

voting age population of 55.4% and lies in a county with a total Hispanic

population of 644,935, nearly 80,000 larger than the population of a

Texas congressional district and enough to form a majority in two

districts. It is represented by an Anglo (white) incumbent who defeated an

2

Only 1.6% of CD 30’s total population lies outside Dallas County itself. About

three quarters of these few are in Collin County, adjoining Dallas County to the north,

and the remaining quarter are in Tarrant County (whose major city is Fort Worth),

adjoining Dallas County to the west. Only 29% of the 1.6% of CD 30’s population

lying in the two counties is black. To ease discussion, the state takes the liberty in the

ensuing text of sometimes lumping CD 30 with CDs 18 and 30 in describing the three

invalidated districts as “single-county” districts.

5

Hispanic opponent (who also was the preferred candidate of Hispanic

voters) in the first Democratic primary held in the district.

A more concrete aesthetic sense of the three invalidated single

county Texas districts comes from comparing them with the congressional

district which was Shaw’s focus, North Carolina’s District 12.3 The first

attachment (Att. A) at the back of this jurisdictional statement is a map

drawn to scale and comparing Texas CDs 18, 29, and 30 with North

Carolina District 12. The second attachment (Att. B) depicts a to-scale,

identically-oriented comparison of the three invalidated minority

opportunity districts with three other Texas congressional districts (CDs

6, 19, and 21), all overwhelmingly Anglo in voting age population (at

88.8%, 80.5%, and 84.2%, respectively), all encompassing both urban

and rural areas, and all upheld by the district court.

While there had been a black opportunity district, originally held

by Barbara Jordan, in Harris County for twenty years before the 1991

redistricting, there had been neither a black opportunity district in Dallas

County nor an Hispanic opportunity district in Harris County. Thus, CDs

29 (in Harris County) and 30 (in Dallas County) were new districts

coming with Texas’s gain of three congressional seats.

Politics, voting rights, and shaping the districts

The politics of adding the two new minority opportunity seats to

the existing 1980’s congressional alignment had a profound effect on the

ultimate shapes acquired by the new seats themselves and by CD 18.

Independent of political forces and other pressures for maintenance of

preexisting districts, more compact and idealized districts could have been

drawn for a black opportunity district in Harris County, an Hispanic

Each of the three Texas districts is fully contiguous; none relies on the kind of

double-point contiguity device used for North Carolina District 12. The origin of the

district court’s description of these districts as lacking contiguity, J.S. App. 62a, 71a-

72a n.54, is a mystery. It certainly is not in the record which carries not a whisper about

a lack of contiguity.

6

opportunity district in Harris County, and a black opportunity district in

Dallas County.4 The district court acknowledges this fact. J.S. App. 70a.

That such districts could have been drawn, and that the Voting

Rights Act required minority opportunity districts in the two counties

ultimately receiving them, was widely conceded. State Representative

Grusendorf, one of the plaintiffs’ two principal witnesses at trial and a

Republican member of the 1991 House Redistricting Committee, testified

that the Voting Rights Act, as well as fairness, required the drawing of a

new black opportunity district in Dallas County and a new Hispanic

opportunity district in Harris County and that more compact ones than

were drawn could have been drawn. Tr. 1:99-101.

The legislative and public record reveals no critical voice of

dissent on the creation of three minority opportunity districts in the two

counties in question at the time the legislature considered and enacted

HB1. Section 5 and its non-retrogression standard appeared to compel

maintenance of CD 18 as a black opportunity district, independent of

what section 2 might require.

Section 2 also seemed to compel creation of an Hispanic

opportunity district in Harris County and a black opportunity district in

Dallas County.5 The previous decade’s Hispanic population growth in

Harris County had been phenomenal, accounting for 67.5% of the overall

population growth in that, the most populous of Texas’s 254 counties.

The state’s long history of discrimination against Hispanics, seared into

the legislative consciousness by Congress’s 1975 extension of section 5

coverage to Texas and through numerous section 5 objections and section

4 The state drew such districts, and their pictures and demographics are in evidence

as St. Exs. 12A, 12B, and 12C, respectively.

5 Looming over the legislature from nearly the beginning of its work on

congressional redistricting and continuing through completion of the task was the

Terrazas v. Slagle lawsuit, pre-filed in the Western District of Texas, under the

legislature’s noses in the state capital. One of the three targets of that suit was Texas’s

congressional redistricting plan, and one of the central claims was that section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act required the creation of three minority opportunity districts in the

vicinity and roughly similar to those ultimately created by the legislature.

7

2 litigation successes by Hispanic voters at all levels of Texas

government, marked a path toward Voting Rights Act invalidation if an

Hispanic congressional district were not created when it reasonably could

be. Moreover, the legislators were intimately familiar with the racially

polarized voting in Harris County which the state’s expert at trial, Dr.

Lichtman, documented in a fashion unrefuted by the plaintiffs’ expert.

Drawing a reasonably compact version of such an Hispanic opportunity

district could be done within the meaning of the first factor in the Gingles

framework, as the State’s Exhibit 12B later showed and as other maps

such as one prepared by State Representative Roman Martinez

contemporaneously demonstrated. Against this backdrop, the legislature

began work on a Harris County Hispanic opportunity district that

culminated in CD 29.

The question of whether section 2 required creation of a black

opportunity district in Dallas County followed a similar pattern. Major

voting rights efforts, first in the 1970’s and then during the 1980’s round

of congressional districting, to create a black opportunity district in Dallas

had fallen short. With the strengthening of section 2 through the 1982

amendments to the Voting Rights Act and the availability of an additional

congressional seat as a result of the post-1990 census reapportionment,

the success of a section 2 suit should there be no black opportunity district

created was foreordained. This, coupled with the existence of racially

polarized voting in the Dallas area of the degree confirmed by Dr.

Lichtman s analysis and the fact that a reasonably compact black

opportunity district clearly could be created in the area, left no room for

debate about the Voting Rights Act compulsion to create such a district.

Thus, the state drew three minority opportunity districts in the

two counties to comply with an uncontested understanding that the Voting

Rights Act compelled it. The state conceded from the beginning that it

had been race-conscious in its decision to draw three minority opportunity

districts, two in Harris County and one in Dallas County. It did not

concede that the configuration and precise location of the districts

ultimately denominated CDs 18, 29, and 30 were the products solely,

primarily, or even substantially of race-consciousness. The idealized

districts drawn for State’s Exhibit 12 were the product of race-

8

consciousness and compactness. The real districts were the product of

much more.

While holding to the need to meet Voting Rights Act

requirements, the state had to draw real districts by taking into account

other powerful historical, political, and legal factors, including the one

person, one vote constitutional rule, the felt necessity (or desire) of

protecting all congressional incumbents, and the closely related,

historically-based principle of drawing new districts with an eye towards

the interest of state senatorial aspirants for congressional office. These

forces, especially incumbency protection and aiding senatorial aspirants,

drove the idealized minority opportunity districts from their cores and into

the shapes and configurations ultimately assumed by CDs 18, 29, and 30.

Overall, as the district court found, the state succeeded nearly

perfectly in realizing its related goals of incumbency protection and aiding

senatorial aspirants. No congressional incumbent of either party was

paired with another, despite the addition of three new congressional

districts, two in Texas’s two most populous counties and one anchored in

the state’s third most populous county. In the 1992 election following

redistricting, every incumbent save one (who had been the object of highly

publicized criminal inquiries) ran and won reelection. Three former state

senators ran for the three new congressional seats, and all three won.

Accomplishing this goal, however, significantly perturbed the

configuration (though not the demographics) of the idealized minority

opportunity districts in Harris and Dallas counties. In Harris County, two

state legislators, Senator Green and Representative Martinez, were the

prime aspirants for any new Harris County Hispanic opportunity district

that was to be created. Their state legislative political bases lay in slightly

different sectors of the county, and each began to tug and pull at the

idealized district, trying to move as much of it as possible into his home

territory (while still maintaining its integrity as an Hispanic opportunity

district). Their tug-of-war, fired by personal political ambitions,

significantly distorted the idealized district. Further complicating their

effort was the two decade-old black opportunity district, CD 18.

Incumbency protection compelled its maintenance, but so did voting rights

law, which required it to remain a black opportunity district. Incumbency

9

protection blocked CD 18’s movement to the south and east of its core,

into the territory of CD 25, because a Democratic incumbent there wished

to maintain his Democratic base. That base would be severely eroded

were black voters (who vote Democratic to the order of 97%) moved into

CD 18 to maintain its legal integrity as a minority opportunity district.

These largely non-racial forces, combined with strict adherence to the one

person, one vote rule and numerous idiosyncratic political factors, led to

CD 18 and CD 29 entwining each other.

The shaping of CD 30 in Dallas primarily resulted from the

efforts of two powerful Anglo Democratic incumbents, one to the east of

the core of the idealized district (in what became CD 24) and one to the

west (in what became CD 5), trying to hold onto as much of their

Democratic political bases as they could, while still permitting CD 30’s

creation. The reason for this dynamic was that the idealized black

opportunity district and the core of CD 30 effectively worked as a wedge

driven directly into the middle of the old CD 5 and the old CD 24.

As CD 5’s incumbent successfully peeled Democratic voters from

the east and CD 24’s incumbent did the same thing in the east, the state

senatorial aspirant (then-Senator, now-Congresswoman Johnson) for what

became CD 30 had to move into other Dallas territory, largely to the

north, to find population for the one person, one vote rule and Democratic

voters for political viability, all the while maintaining the district so as to

avoid running afoul of section 2. Just as numerous idiosyncratic factors

played on the shape of the Harris County minority opportunity districts,

so they did in Dallas. A desire to have part of the Dallas-Fort Worth

International Airport in the district led Senator Johnson to extending an

arm of the district into that comparatively remote and unpopulated

territory. Another arm of CD 30 extended to Grand Prairie, a primarily

white Metroplex city sitting astride the Dallas/Tarrant county line, where

Senator Johnson and CD 24’s incumbent forcefully contended for what

each viewed as friendly territory. (CD 30’s Grand Prairie portion is 59%

white and only 14.7% black.) Yet another loop, first to the north then

back to the east, reached for two areas, one of white Jewish voters who,

though not in her senatorial district, had been supportive of Senator

Johnson during her political career and one of middle-class black voters

with religious and social ties to the district’s core.

10

Maps introduced by the state broke the three districts into cores

and fingers in order to analyze the population and demographic make-up

of the district. St.Exs. 33 (CD 30), 61A (CD 18), & 61B (CD 29). They

show that the district cores are primarily minority, while the extensions

from the cores are primarily Anglo.

The story of how these districts acquired their shape is complex

and highly nuanced. Race was a factor, but only one among many. The

districts’ idealized shapes, found in State’s Exhibit 12, reveal what their

shape would have been had race and compactness been the only factors.

Lower court’s decision

In holding CDs 18, 29, and 30 unconstitutional under the Shaw

framework, the district court did not reject all the state’s arguments. It

accepted that the state successfully protected incumbents of both parties

and furthered the interests of state senatorial aspirants. It accepted that

these kinds of objectives had regularly informed, indeed driven, earlier

Texas congressional redistricting efforts. The court also accepted that

race-conscious redistricting is not in itself unconstitutional.

The court, however, held that each of the three invalidated

districts was of a bizarre shape, notwithstanding their confinement to a

one-county urban locale in a 254-county state which is the second largest

territorially in the nation. In connection with that conclusion, the court

held that the shapes of district boundaries are part of the “essence” of a

Shaw claim. J.S. App. 53a n.40.

The court s opinion is not entirely clear on whether it requires

Shaw-type plaintiffs to establish that race is the only factor explaining the

shape of a district. Instead, it posits two poles between which lie a Shaw

claim. At one pole is the circumstance in which the governmental entity

has drawn irregularly shaped districts in an obvious effort to exclude

voters based on race; at the other is the circumstance in which racial

classifications of voters are made but the court’s definition of “traditional”

districting principles are used to make the classification. The latter is

constitutionally acceptable and the former is not. J.S. App. 52a-53a. The

11

court places the state’s efforts in CDs 18, 29, and 30 in the former,

unacceptable category. In the course of reaching this conclusion,

however, the court expunged incumbency protection from the approved

list of traditional districting principles, J.S. App. 56a,6 and further stated

that racial gerrymandering was an essential part of incumbency

protectionf.]” J.S. App. 65a.

Based upon the foregoing analysis, the court subjected the state’s

redistricting plan to strict scrutiny. The court begins this level of inquiry

by reading Shaw to hold “that compliance with the Voting Rights Act

might be a compelling state interest that, if narrowly tailored, would

withstand . . . strict scrutiny[.]” J.S. App. 69a. The court then holds that

the state satisfies strict scrutiny only if it proves that the minority

opportunity districts actually drawn in the redistricting plan were required

by section 2 or section 5 of the Voting Rights Act. J.S. App. 70a-72a. It

holds:

[T]o be narrowly tailored, a district must have the least

possible amount o f irregularity in shape, making

allowances for traditional districting criteria.

J.S. App. 72a (emphasis added).

The court never addresses whether the Voting Rights Act

reasonably could have been read by the legislature to require the drawing

of three minority opportunity districts of some sort in the two counties. It

makes no firm conclusions as such about the Voting Rights Act’s

requirements or whether they required (or reasonably could have been

read to require) that three minority opportunity districts be drawn in the

vicinity where they were.^ Instead, the court skips any conclusion about

Tliere, the court states that Shaw nowhere refers to incumbent protection as a

traditional districting criterion.”

'J

The court does treat avoiding Voting Rights Act liability as a compelling

governmental interest. J.S. App. 76a. While it is not entirely clear, there are hints in

the decision that the legislature reasonably could have concluded that sections 2 and 5

of tlie Voting Rights Act required the creation of minority opportunity districts in Harris

and Dallas counties. The plaintiffs must have read the facts, the law, and these hints

12

compelling governmental interest and finally concludes that CDs 18, 29,

and 30, as actually drawn in the plan, are not narrowly tailored and points

to the “dispositive fact that alternative plans for Districts 18, 29, and 30

were all much more geographically and otherwise logical[.]” J.S. App.

73a.

THE QUESTIONS PRESENTED ARE SUBSTANTIAL

The Court in Shaw v. Reno countenanced a new, “analytically

distinct” claim in the equal protection law of redistricting and voting

rights. Under S/tow:

[R]edistricting legislation [is unconstitutional if it] is so

extremely irregular on its face that it rationally can be

viewed only as an effort to segregate the races for

purposes of voting, without regard for traditional

districting principles and without sufficiently compelling

justification.

113 S.Ct. at 2824. The Court termed this racial gerrymandering and

defined it as “the deliberate and arbitrary distortion of district boundaries .

. for [racial] purposes.” Id. at 2823. The Court held that a complaint

against the North Carolina district stated a claim and sent the case back to

the district court for trial.

Shaw has left much uncertainty in its wake. Questions abound

about the standards for determining whether a configuration is so irregular

that it implicates the Shaw doctrine; about the constitutional effect of the

play of non-racial factors on a district’s shape; about the burdens of

persuasion and proof for the different Shaw elements; about the interplay

of sections 2 and 5 of the Voting Rights Act with the Shaw elements; and

about what constitutes narrow tailoring.8

similarly to the state for tire remedial plans they proffered to the court purported to

create two minority opportunity districts in Harris County and one in Dallas County.

g

There are no settled expectations as a result of Shaw. The decision itself was on a

case brought up from a dismissal for failure to state a claim. The decennial redistricting

avalanche that follows the census was completed before Shaw and will not be repeated,

except as a product of Shaw and lingering Voting Rights Act challenges, until half a

13

Lower courts have been flooded with Shaw challenges and have

interpreted Shaw in fundamentally different ways. In the congressional

redistricting sphere alone, decisions in Texas (Vera v. Richards),

Louisiana (Hays v. Louisiana), Georgia (Johnson v. Miller), North

Carolina (Shaw v. Hunt), and California (DeWitt v. Wilson) have varied

not only in their facts, but in their analysis of Shaw* 9

The decision in the Texas case differs from the others in

significant ways. It is the only case involving the invalidation of localized

urban districts. It is the only case in which incumbency protection is

expressly excluded from the category of traditional districting principles.

It is the only case in which a preexisting minority opportunity district (CD

18) is invalidated. It is the only case in which a legislatively developed

plan received neither a threatened nor actual section 5 objection and was

explicitly upheld as consistent with section 2 and the Equal Protection

Clause’s strictures against racial discrimination and partisan

gerrymandering. It is the only case invalidating more than one district.

I. Whether the lower court erred: (i) in holding that

proof that more compact, regularly shaped minority

opportunity districts could have been drawn but were not

because of non-racial politics is irrelevant to demonstrating

that race is not the sole or overriding reason for the irregular

shape of minority opportunity districts; and (ii) in holding

that, on the contrary, such proof demonstrates an inability to

meet the narrow tailoring requirement of strict scrutiny?

The largely uncontradicted facts establish that the state would

have been in violation of section 2 of the Voting Rights Act had it not

drawn a black opportunity district in the Dallas area and an Hispanic

opportunity district in the Houston area and of section 5 of the Act had it

not maintained a black opportunity district in the Houston area.

decade from now. Tlnis, now is the time to correct misunderstandings that Shaw may

have created.

9 Die Court already has docketed appeals in three of these cases: Hays as No. 94-

558; Johnson as No. 94-631; and DeWitt as No. 94-275.

14

Hypothetical districts sufficient to meet the first threshold factor of

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986), were possible.

The facts also establish that, while adhering to Voting Rights Act

requirements, the state abandoned the ideal configurations of the

hypothetical districts and drew what became the very real CDs 18, 29,

and 30 because of raw redistricting politics. The central tenet of that

politics was in 1991 what it had been throughout Texas congressional

redistricting history: the protection of incumbents and the related tenet of

aiding state senatorial aspirants for Congress.

Thus, non-racial real politics changed the legal ideals of Gingles

minority opportunity districts into carefully crafted, actual districts well

within the historical mainstream of Texas redistricting. The state’s

understanding was that it has constitutional breathing space under Shaw

to let political reality shape legal ideals as long as the political reality is

not racial.

The district court saw things differently, not so much on the facts,

but in terms of Shaw's constitutional constraints. In fact, its reading of

Shaw is the virtual antithesis of the state’s. Resolution of this difference

is a necessity if states are ever to have any sense of their constitutional

obligations while drawing congressional districts that comply with their

own traditions and federal voting rights and one person, one vote

requirements. If redistricting is to remain what it always has been,

“primarily the duty and responsibility of the State through its legislature,”

Growe v. Emison, 113 S.Ct. 1075, 1081 (1993), states must be apprised

of the degree to which they are constitutionally compelled to adhere to

non-constitutionally based federal judicial views about what is a legitimate

traditional districting criterion, what district shapes are acceptable, and

the degree to which idealized minority opportunity districts are unalterable

by state policy choices.

The lower court’s rationale flies in the face of Shaw. Shaw held

that racial gerrymandering is the distortion of district boundaries to a

degree that is explainable only on the basis of race. The lower court, on

the other hand, found redistricting unconstitutional if reasons other than

race, and outside the court’s own definition of traditional districting

15

principles, distorted boundaries that could have been drawn for racial

reasons.

Other courts have rejected this expansive reading of Shaw and

taken the Court at its word. In the Georgia case, the court ruled that there

is no racial gerrymander, and thus no occasion for strict scrutiny, “[i]f

race, however deliberately used, was one factor among many of equal or

greater significance” in the plan. Johnson v. Miller, 1994 WL 506780

(S.D. Ga. Sept. 12, 1994), slip op. at 14. In the California case, the court

read Shaw as condemning redistricting based “solely” on race. DeWitt v.

Wilson, 856 F.Supp. 1409, 1412 (E.D.Cal. 1994).

The question thrown into relief by contrasting the lower court’s

reading of Shaw with the California and Georgia courts’ reading is critical

and calls for resolution by this Court. Is a state that is under Voting

Rights Act compulsion to draw minority opportunity districts

simultaneously under constitutional compulsion to adhere to supposedly

non-constitutional but nonetheless judicially imposed criteria in drawing

the districts, even though non-racial, state-developed criteria permit the

drawing of differently shaped districts? Shaw’s words and other court

rulings interpreting them answer “no;” only the lower court here has

answered “yes.” Whether the law of redistricting has become so rigidified

“ the state’s choices so constricted — in the wake of Shaw needs

clarification.

II. Whether, in a statewide redistricting, localized, single

county urban minority opportunity districts with a lesser

degree of single-race dominance than every other district in

the state can be deemed so facially irregular that Shaw ’s

threshold test is satisfied?

The contours of Shaw’s threshold test of shape remain

undeveloped and one of the decision’s most puzzling aspects. This case

presents a unique circumstance to the Court. All three challenged Texas

districts are different in kind from the districts challenged in the three

other states whose cases are either at the Court or on their way here.

North Carolina District 12 is 160 miles long and passes through

10 of the state’s 100 counties. Shaw v. Reno, 113 S .Ct. at 2820-21. The

current version of Louisiana District 4 covers 15 parishes, divides four of

16

the state’s major cities, and is served by four media markets. Hays v.

Louisiana, 1994 WL 477159 (W.D. La. July 29, 1994). Georgia District

11 splits 8 counties and 5 municipalities and covers four discrete, widely

spaced urban centers. Johnson v. Miller, supra.

The Texas districts are fundamentally different. Each is a

localized, single-county10 urban district, served by a single economy and a

single media market. They are the three least segregated congressional

districts in Texas, taking racial segregation in its popular sense of single

race dominance. These characteristics are set against the backdrop of a

state geographically much larger than the other three states and racially

more complex because of its tri-ethnic makeup.

With resolution set at state-level, the appropriate setting for a

statewide redistricting plan, CDs 18, 29, and 30 do not give the

appearance of being vastly distorted, either in isolation or in comparisons.

See, e.g., Att. B (end of statement).

Viewed historically, the three challenged districts are not

extraordinary either. In the 1960’s, in the redistricting following after the

advent of the one person, one rule, the Texas legislature created a district -

- old District 6, sometimes termed the Tiger Teague district — running in a

narrow strand of counties from southeast of Houston through rural east

Texas into bits at the southern ends of both Tarrant and Dallas counties.

When compared at scale, it dwarfs CDs 18, 29, and 30 and reduces

whatever in their shapes that was distasteful to the lower court to

insignificance.11

The Court appears in Shaw to have rejected the position of one of

the two testifying plaintiffs in this case, Mr. Chen, who stated that he

10 Recall that barely over 1% of CD 30’s population falls outside Dallas County.

11 As explained through the evidentiary trial statement of a former state senator and

state Supreme Court justice, this Texas district of 30 years ago was the original spur for

the comment that one could drive down the district with both doors open and kill half

the people in the district. Contemporary computer technology provides the tools for

more precise work in the modem era. Still, controlling for technological capability, old

District 6 is a standard-setter.

17

views these kinds of assessments about shape as “personal judgment” as

to which “[tjhere is no right or wrong.” Tr. 1:41. Under Shaw, the shape

takes on constitutional significance. Nonetheless, content now must be

given to this seemingly critical matter.

Shape is a contextual matter. The interplay of historical and

contemporary comparisons, the degree of resolution of the viewing

microscope, comparative technologies, and community location affect the

description. Here, all those factors point toward a conclusion that, in any

meaningful constitutional sense, the three minority opportunity districts

here are not bizarre within Shaw }s meaning. Holding otherwise threatens

to enmesh the Court in redistricting inquiries from which it can never

disentangle itself and for which it can never offer constitutional guidance

to the trial courts.

Shaw did describe the archetype of a distorted district. It is a

construct that includes individuals who belong to the same race, but who

are otherwise widely separated by geographical and political

boundaries.” 113 S.Ct. at 2827 (emphasis added). Not one of the three

districts invalidated by the trial court fits the Shaw archetype.

While the question of what is irregular enough to pass the Shaw

threshold is important and needs definitive resolution, the districts

involved in this case fall far enough short of the threshold of bizarreness

that summary disposition is possible. The comparative pictures attached

to this statement, combined with both the highly integrated nature of the

districts and their single-county urban character, are enough to answer

that these districts do not raise a Shaw issue.

III. Whether an unquestioned state tradition of

incumbency protection (and the related tradition of furthering

senatorial aspirations) may be judicially excluded from the

realm of traditional districting principles which, if followed,

overcome a Shaw challenge?

That Texas has a long, unbroken tradition of protecting

incumbents in congressional redistricting goes unquestioned by the lower

court. That Texas succeeded in honoring that tradition in its 1991

congressional redistricting also goes unquestioned by the lower court.

18

This Court recognized and refused to “disparage” this Texas

tradition over two decades ago, noting the state’s interest in “maintaining

existing relationships between incumbent congressmen and their

constituents and preserving the seniority the members of the State’s

delegation have achieved” in Congress. White v. Weiser, 412 U.S. 783,

791 (1973). More broadly, the Court has recognized avoidance of

contests between congressional incumbents and “preserving the cores of

prior districts” as legitimate redistricting objectives. Karcher v. Daggett,

462 U.S. 725, 740 (1983).

The lower court, however, saw things differently. In the context

of a Shaw challenge, the court removed incumbency protection from the

approved list of traditional districting principles. This unprecedented step

had major constitutional consequences. The court read Shaw to permit

distorted district boundaries if they honored traditional districting

principles. The court also knew that incumbency protection was a Texas

redistricting tradition and that the evidence established that the prime

determinant of the actual boundaries of the ultimately invalidated districts

was incumbency protection. Thus, the only way to find a Shaw violation

would be to excise incumbency protection as a legitimate state

consideration. This the court did.

Its exclusion of incumbency protection was both fatal to Texas’s

defense and contrary to the decision in Georgia’s Shaw congressional

redistricting case, Johnson v. Miller, which specifically lists protecting

incumbents as a traditional districting principle. Slip op. at 12. More

fundamentally, it raises the troubling specter that traditional districting

principles, explicitly acknowledged in Shaw to be a non-constitutional

concept, is an infinitely manipulable judicial concept. This approach

carries Shaw far afield from its constitutional base, and the Court should

take up this question to return Shaw to its proper home.

Because Shaw makes clear that the traditional districting

principles it employs as part of its constitutional framework are not

constitutional in origin, and because redistricting is fundamentally a

matter of state sovereignty, the only permissible source for discerning

traditional districting principles is the state and its traditions and laws.

The lower court disregards this fundamental tenet and converts the

19

concept of traditional districting principles into a highly manipulate

federal judge-made rule. Wielded this way, Shaw’s scope is vastly

broadened, and the discretion given to local federal district courts is

widened far outside heretofore confined constitutional banks. Nothing in

Shaw, nothing in this Court’s redistricting precedents, and nothing in the

doctrine of federalism justifies the step taken by the district court.

It is crucially important to the states that the non-constitutional

concept of traditional districting principles be reconfined to its origin: the

histories, political traditions, and laws of the states themselves. The lower

court’s approach is an unjustified, unprecedented narrowing of state

redistricting prerogatives.

IV. Whether the lower court erred in applying Shaw to

invalidate the three minority opportunity districts?

This jurisdictional statement repeatedly points to the confusion

the district courts have drawn from Shaw. Their widely varying

interpretations necessarily leave conscientious state legislators adrift in

trying to comply with Shaw's dictates in drawing congressional districts.

Even within the district court decision brought before the Court in this

case, the analysis is sufficiently fluid and ambiguous that the logical

progression of holdings and subholdings is frequently lost.

Furthermore, the plaintiffs failed to establish much of the racial

gerrymandering claim that Shaw assumed in the procedural posture of that

appeal. They did not show that creation of the minority opportunity

districts exacerbated racial bloc voting. See 113 S.Ct. at 2827. Nor did

they show that elected representatives of the districts ignored their polity

as a whole while focusing nearly exclusive attention on the minority group

given an equal electoral opportunity through the district’s creation. See

id. The evidence, in fact, points in precisely the opposite direction.

To avoid the pitfalls of focusing too narrowly on what the lower

court said, instead of looking at what it actually did, the state notes the

importance of the situation- and fact-specific question raised by the lower

court’s action. Does the Equal Protection Clause prohibit a state from

reacting to racially polarized voting patterns and the associated demands

of sections 2 and 5 of the Voting Rights Act by drawing minority

opportunity districts that are localized, single-county, and urban in

20

character, and that are the most racially integrated in the state, even if

more idealized compact minority opportunity districts could have been

drawn but were not for such non-racial reasons as incumbent protection?

Shaw raises this question but does not answer it. Answering it

would be a tremendous step toward clarifying Shaw’s ambiguous reach.

V. Whether plaintiffs who do not claim harm from a

diluted vote, who have not been invidiously discriminated

against, and who otherwise point to no concrete injury have

standing to press an equal protection claim?

Standing is a threshold issue, a kind of constitutionally compelled

docket control. Shaw did not address the issue of constitutional standing,

and, inasmuch as implicit pronouncements on constitutional issues do not

settle them, cf. Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651, 671 (1974), standing

remains both open and important.12

Despite Shaw’s apparent premise that individualism matters in

redistricting, the plaintiffs did not identify a single concrete harm which

they would suffer from HB1 and the configurations of the districts in

which they lived and voted. They testified to nothing indicating that HB1

subjected them to a comparative disadvantage with some real or

hypothesized other person.

Blum, who lives in CD 18, indicated that “more than anything

else the abandonment of the “idea of a color-blind society” that he

perceived in HB1 was the “moral reason” for his involvement. His most

specific statement was that white voters are injured by such redistricting

because it polarizes us from our neighbors [and] segregates us by race.”

Chen, who does not live in one of the invalidated districts, testified about a

series of related beliefs in equality.' Orcutt, a resident of CD 30, testified

to her desire to live in the adjoining district, CD 3, which is represented by

a Republican congressman more aligned with her political views but

emphasized that CD 30 was not a segregated district. Vera, a resident of

19 Shaw’s failure to substantively treat the standing issue has been described as a

remarkable departure.’ Karlan, All Over the Map: The Supreme Court’s Voting

Rights Trilogy, 1993 Sup.Ct.Rev. 245, 278.

21

CD 29, testified that he found it offensive when race is used as a

redistricting factor. Thomas, a resident of CD 29, expressed “concem[]”

about confusion, but later agreed that hers is a “theoretical concern” and

that she does not feel personally discriminated against in the congressional

redistricting process. Powers’ testimony was of a similarly vague nature.

One of the three essential elements of the constitutional law of

standing is that plaintiffs must establish “injury in fact,” meaning that

they must demonstrate some harm that is “concrete and particularized”

instead of merely “conjectural or hypothetical.” Lujan v. Defenders o f

Wildlife, 112 S.Ct. 2130 (1992). Generalized grievances are insufficient

for standing, and the mere claim of a right to a particular type of conduct

falls short of constitutional minimums. Allen v. Wright, 468 U.S. 737

(1984).

In Northeastern Florida Chapter o f the Associated General

Contractors o f America v. City o f Jacksonville, 113 S.Ct. 2297 (1993),

the Court explained that, when the claim is a denial of equal protection,

plaintiffs show harm by demonstrating that they face higher hurdles.

Under Northeastern Florida, equal protection standing does not require

plaintiffs also to establish that, once the hurdles were lowered, they would

have cleared them and won. Critical to the Northeastern Florida

outcome, however, was the fact that the plaintiffs there were complaining

of higher hurdles in competing for a concrete benefit: municipal

construction contracts. Otherwise, nothing would have differentiated the

Northeastern Florida contractors from the contractors in Worth v. Seldin,

422 U.S. 490 (1975), who failed to establish that they were competing for

anything.13

The plaintiffs in this case do not complain of higher hurdles — or

any other comparative disadvantages — which deny them an equal

opportunity to compete for something concrete. They specifically eschew

any claim of vote dilution, which would be a concrete harm. They

13 Allan Bakke’s goal in Regents o f the University o f California v. Bakke, 438 U.S.

265 (1978), was as concrete as the contractors in Northeastern Florida', he wanted a

medical education at the Medical School at the University of California at Davis but

arguably faced higher hurdles to admission. The palpability of his goal was an essential

element imparting standing. Id. at 280 n. 14.

22

presented no evidence that HB1 somehow stamps them with the kind of

badge of inferiority that marked plaintiffs in the Court’s historic equal

protection cases. See, eg., Brown v. Board o f Education, 347 U.S. 483,

493 (1954); Strauderv. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303, 308 (1879).

Striking at the public corrective (minority opportunity districts)

for private discrimination (racially polarized voting), they claim harm

from not living in a color-blind society and point to public reactions not

private origins as the cause of their harm. Compare Palmore v. Sidoti,

466 U.S. 429, 431 (1984) (‘[p]rivate biases may be outside the reach of

the law, but the law cannot, directly or indirectly, give them effect”).

Nothing differentiates these plaintiffs from any other voter in the state

except their highly developed sensitivity. Nothing in HB1 places the

plaintiffs at a comparative disadvantage.14

Whether such abstract harm is enough to impart standing in the

Shaw context is an important question with far-reaching implications. It

can expose states to redistricting challenges from virtually any quarter at

any time on the grounds that the redistricting plan is not color-blind

enough to suit the tastes of a given voter. It carries the potential of

converting the three-judge courts hearing these cases into virtual open

forums for public debate on the meaning of democracy and color

blindness, untethered to the case or controversy foundation governing

other kinds of cases.

This ironic result, for a function more at the center of the state’s

policy control than most other governmental functions, would stretch

standing further than ever before. It would so divorce standing from

normal understandings of the injury in fact requirement that in the thirty

years since Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962), redistricting law would

have advanced from lying wholly outside federal judicial consideration to

being an area only loosely bound by traditional federal jurisdictional

restraints.

Comparative disadvantage is an equal protection concept. The Fifteenth

Amendment might embody a different standing concept friendlier to the plaintiffs;

however, they expressly abandoned their Fifteenth Amendment claim prior to trial.

23

Offended sensibilities were not enough for standing in Allen v.

Wright, where the reality was racial discrimination; whether they are

enough for standing under Shaw, where the ideal is color-blindness, will

further determine Shaw’s scope.

VI. Whether the court exceeded its equitable powers and

encroached on the state’s domain by exposing the legislature

and its members to possible civil contempt and impermissibly

confining the state’s remedial options to formal legislative

enactments (protectively, based on a cautious interpretation of

the lower court’s order)?

The district court ordered that “the Texas legislature shall develop

on or before March 15, 1995, a new Congressional redistricting plan”

consistent with the court’s opinion invalidating three congressional

districts established by HB1. J.S. App. 2a. A cautious interpretation of

this language makes it an injunction to enact legislation instead of a

typical remedial scheduling order giving the state an opportunity to correct

a constitutional defect. This appellate point is a provisional one, premised

on the precautionary reading.

As so read, the order has two basic flaws. First, it disregard

voting rights precedents permitting legislative bodies to offer proposed

remedial plans, to which judicial deference is owed, without using formal

legislative enactments. See, e.g., Wise v. Lipscomb, 437 U S. 535 (1978),

and Burns v. Richardson, 384 U.S. 73 (1966). Second, it disregards this

Court’s direction in Spallone v. United States, 493 U.S. 625 (1990), to

federal district courts to exercise extreme caution in deploying their civil

contempt powers to force governments to pass legislative enactments.

By rigidifying what constitutes a legislative remedial proposal in

voting rights and redistricting litigation, and by converting a rule of

opportunity, see, e.g., McDaniel v. Sanchez, 452 U.S. 130, 150 n.30

(1981), into a rule of compulsion, the district court strayed beyond

federalism’s equitable bounds, and a corrective is warranted.

CONCLUSION

The Court should note probable jurisdiction. Summary reversal

is appropriate on the question of whether the three districts are so

irregularly shaped that further inquiry is necessary under the Shaw

24

framework; otherwise

consideration.

October, 1994

the appeal should be set down for plenary

Respectfully submitted,

Dan Morales

Attorney General of Texas

Jorge Vega

First Assistant Attorney General

Renea Hicks*

State Solicitor

*Counsel o f Record

P-0. Box 12548, Capitol Station

Austin, Texas 78711-2548

(512) 463-2085

Attorneys for State Appellants

Attachment A

District 19

District 21

District 6

District 18

D istrict 30

District 29

COMPARISON (TO SCALE) OF SELECTED CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICTS

PLANC657 DISTRICTS 6, 18, 19, 21, 29, & 30

i i f i f i u i r

I* *I n r i i i M t i i t i i t

Attachment B