Rose v. Lundy Court Opinion

Working File

March 3, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Rose v. Lundy Court Opinion, 1982. 8d2a2543-f092-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0bd65031-ec68-4e1c-bf66-8c5f28070db8/rose-v-lundy-court-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

l1l_11\: 1il? __ r'he t|nitetr .srrrrts r,Aw wriuK :t-z-tJz

pal. ciet'k. agent or. servunt to slll an,v itcms. effect,

lrarapher.nulia, itc(,essor.\' or thing u hich is rkrsignerl or

rnlrketerl Ii.'r.use sith illegal c:rnlurbis or rlrugs, as rle,-

finerl b,l' Illinois Rer.iserl Statutes, u-ithr,rut obtaining a Ii-

cense therefor. Such licenses shall be in acltlition to any

or all other licenses held by applicant.

B. Application:

Application to sr:ll arr.v item, efl'ect, parapher.nrrlia, acces_

sory or thing rvhich is tlesignetl or ntarketed for use with

illegal cannabis or drugs shall, in acldition to require-

ments of Article &1, be accompanied by affidavits b.v ap-

plicant and each and ever1, emplo.vee authorizecl to sell

such items that such pefson has ner.er been convictec.l of

a rlrug-related offense.

C. Nlinols:

It shatl be unlarrful to sell or give items as desctibecl in

Section 8-7-I(iA in an.r' form to an1' male or female chilcl

under eighteen years of age.

D. Records:

Everl' licensee must keep a recor(l of er.erf item, effect,

paraphernalia, accessorv or thing s.hich is clesigner.l or

marketed lor use u'ith illegal cannabis or cin:gs *hich is

sold and this recorrl shall be open to the inspection of any

police officer at anv time dur.ing the houls of business.

Such record shall contain tlie name ancl adclress of the

purchaser, the name ancl quantit.v of the procluct, the

date and time ofthe sale. and the licensee oragent ofthe

licensee's signature. such recortls shall be retainecl for

not less than trvo (2) years.

E. Regulations:

The applicant shall comply rvith all applicable regulations

of the Department of Health Services ancl the police

Department.

Scctiorr l: Th:,rt the Hoflnran Estates )Iuncipal Cocle be

anrenrlerl b1'arlrling to Sec. li-2-l Fees: llerchanis (proclucts)

the arlditional language as follou.s:

Itenrs rlesignecl ur marketed for use t-ith illegal cannabis

or drugs $150.00

Spr'lir.rrr .i: Penalt-,-. An.v ;ter.son violati.g an;' provision of

this orclinance shall be finetl not less than ten clolLrs ($10.00)

n()r mol'e than five hundred dollars ($500.00) for the first of-

fense and succeeding offenses during the sarne calendar ),ear,

and each da1' that such r.iolation shall continue shall be

deemed a separate and distinct offense.

Secliorr j: That the Village Clerk be ancl is hereby authorized

to publish this orclinance in panrphlet form.

Scclir.rrr 5: That this orrlinance shall be in full force and effect

Mal' I, l9?8, after its passage, appr.or.al ancl publication ac-

coxling to larv.

Jusrtcu Wrrrre , concurring in the judgment.

I agrere that the jurlgment of tle Courl of Appeals nrust be

reverserl. I do not, horvever, believe it necessary to riiscuss

the overbreatlth problem in order to t.cach this result. The

Court ofAppeals hekl the ordinance to be void for vagueness;

it dir.l not discuss any problem of overbreadth. That opinion

should be reversed simpty because it errerl in its analysis of

the vagueness problem presentecl bl,the <lrrlinance.

I agree u'ith the nrajorit.r' that a facial valfucness challenge

to an eeononric regulation must denronstrate that "the enact-

ment is irnpermissibly vague in all rtf its applications." In/'ro,

at l-r. I also agree with the majority's statemerlL that the

"nrarketed for use" standard in the orrlinance is "sufficiently

clear." There is, in my vierv, no nee,l tt.r go any further: lf it

is "transparently clear" that some particular contluct is re-

stricterl liy thc orrlinanr:e, thc ordinance survives a facial

challenge on vagueness groun(ls.

'fechnically, overbreatlth is a standing rirrctrine that per-

nrits parties in cases involving First Amendnrent challeriges

t(, government restr.ictions on noncommercial speech to argue

that the regulation is invalirt because of its effect orr ,he First

Amendment tights of others, nr.rt pr.c,sently before the Clourl,

['troaLlick v. Oklahonur, 4ll] U. S. d0l, (il:]-6lir Og?B).

Whether the appellees may make use of thc overbrearlth rloc-

trine depends, in the first instance, on u,hether or not they

have a colorable claim that the ordinance infringes un .on-

stitutionaily protected, noncommercial speech of others. Al-

though appellees claim that the ordinance does have such arr

effect, that argument is tenuous at best and should be left to

the lower courts for an initial determination.

Accordingly, I concur in the juclgment reversing the deci-

sion below.

RICIIARD n\. WII.LIAMS. Holfnran fisratcs, lll., for appcltrnrs; Ml-C-'llAIi l_. pRtTZKt:R. Chicago, Iil. (R. BRF.Ni o,rxlUf_ iia lutntrx t..SULLIVn N, with him on rhc b;ief) for appcllec.

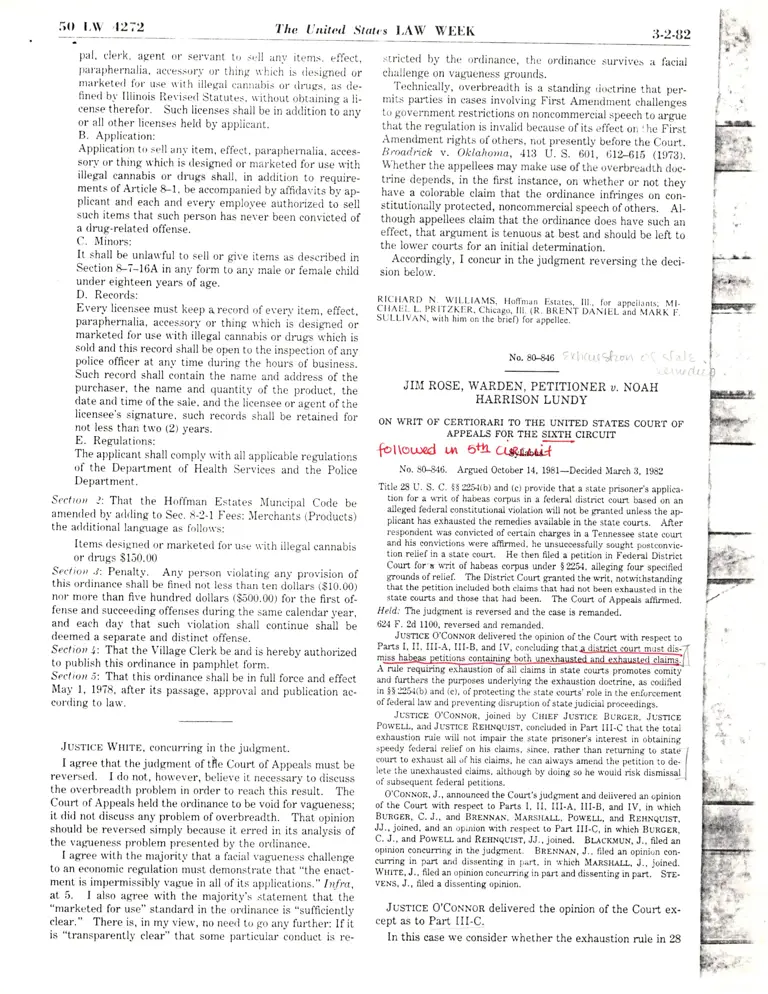

No.8G&16 r rr

JII,I ROSE, WARDEN, PETITIONER u. NOAH

HARRISON LUNDY

ON WRIT OF CERTTORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

fottouxd Lr otlr c,45&,r-

No.80-846. Argued October 14, l98t-Decided March B, 1982

Title 28 U. S. C. {$ 25.1(b) and (c) provide that a srate prisoner's applica-

tion for a srit of habeas corpus in a fetleral distnct court ba^sed on an

alleged federal constitutional violation *ill not be gr.anted unless the ap-

plicant has exhausted the remedies available in the state courts. A-ft,er

respondent was convicted of cenain charges in a Tennessee state coun

and his convictions were affirmed, he unsuccessfully sought postconvic-

tion relief in a stare court. He then filed a petition in Federal District

Coun for-a writ of habeas corpus under $ 225.1. alleging four specified

grounds ofrelief. The District Court granted the writ, norwithstanrling

that the petition included both claims that had not been exhausted in the

state coufts and those thar had been. The Court of Appeals aflirmed.

Held; The judgment is reversed and the case is remanded.

624 F. 2d 1100, reversed and remanded.

JusTIcE O'CoHNon delivered the opinion of the Court $ith respect io

Parts I, II, III-.q,, III-B, and IV, concluding that.ir disrrict court rrtqst dis-7

ii=,!"rut*+:tttt"PA rule requiring exhaustion of all claims in state courts promotes comity-

and furthers the purposes underlfing the exhaustion doctrine, as corlified

in S$225{(b) and (c), ofprotecting the state courts,role in the enforcement

of federal larv and preventing disruption of state judiciai proceedings.

JusrrcE O'CoNNoR, joined by CrrrEF JusrrcE BuRcER, JusTrcE

PowELL, a:rd Jusrrcs Rruxqursr, concluded in pan III-C that the total

exhaustion r.rle rvill not impair the state pnsonels interest in obtaining

speedy federal r.elief on his claims, since, rather than returning to state i

court to exhausr all uf his claims, he can always amend the petitir_rn to de- [

Iete the une.rhausted claims. aithough by tloing so he wouid risk rlismissal

lof subsequent federal petitions.

O'CoNNoR, J., announced the Court's judgment and delivered an opinion

of the Court with respect to Parts I, II, III-A, III-B, and IV, in u'hich

BURGER, C. J., and BRENNATv, IIARSIIALL, powELL, and RrHxqursr,

JJ., joined, and an opinion uith respcct to Part IU-C, in which BuRcER,

C. J., and Poweu- end Renrqursr, JJ., joined. BL^oLyuN, J., filed an

opinion concurring in the judg'rnent. BRENNAN, J.. filed an opiniun con-

curring in prrt an(l dissenting in J,art, in l.hich Melsruu.t, J., joined.

Wtltte, J., filed an opinion concurring in part and dissenting in part. Sre-

vuxs, J., liled a disscnting opinion.

Jusucr O'CoNxon delivered the opinion of the Court ex-

cept as to Part [II-C.

ln this case we consider whether the exhaustion rule in 28

I,

tr

[: *]t ,! r ..i'

t'

I

;

L.:t--

[':l ,l

I

I

tl

I

f-.r-

:!-2-1il 'l'he llnitetl Strrtes LAW W[DI( s0 t,w 4.27:l

f..

. cl\.

any c

l('l 'n

lht P'

U. S. C. $$225a(bHc) requires a fetleral district court to

dismiss a petition for a writ of habeas corpus containing any

claims that have not been exhausted in the staLe courts. Be-

cause a rule requiring exhaustion of all claims furthers the

purposes underlying the habeas statute. we hold that a dis-

trict court must dismiss such "mixed petitions," leaving the

prisoner with the ehoice ofreturning to state court to exhaust

his elaims or of amending or resubmitting the habeas petition

to present only exhausted claims to the district court.

I

Following a jury trial, respondent Noah Lundy was con-

victed on charges of rape and crime against nature, and sen-

tenced to the Tennessee State Penitentiary.' A-fter the

Tennessee Court of Criminal Appeals afflrmed the conrric-

tions and the Tennessee Supreme Court denied review, the

respondent filed an unsuccessful petition for post-conviction

relief in the Knox County Criminal Court.

The respondent subsequently filed a petition in federal Dis-

trict Court for a writ of habeas corpus under 28 U. S. C.

$2254, alleging four grounds for relief: (1) that he had been

denied the right to confrontation because the trial court lim-

ited the defense counsel's questioning of the victim; (2) that

he had been denied the right to a fair triai because the pros-

ecuting attorney stated that the respondent had a violent

character; (3) that he had been denjed the right to a fair trial

because the prosecutor improperly remarked in his closing

argument that the State's evidence was uncontradicted; and

(4) that the trial judge improperly instructed the jury that

every witness is presumed to swear the truth. After re-

'viewing the state court records, horvever, the District Court

concluded that it could not consider claims three and four "in

the constitutional framework" because the respondent had

not exhausted his state remedies for those grounds. The

court nevertheless stated that "in assessing the atmosphere

of lhe cause taken as a whole these items may be referred to

collaterally. "'

Apparently in an effott to assess the "atmosphere" of the

trial, the District Court reviewed the state trial transcript

and identified l0 instances of prosecutorial misconduct, only

five of which the respondent had raised before the state

coutts.r In addition, although purportedly not ruling on the

'The court sentenced the respondent to consecutive terms of 120 years

on the rape charge and from five to l5 years on lhe crime against nature

charge.

'The Tennessee Criminal Court of Appeals had ruled specifically on

grounds one and two, holding that although the trial court erred in restrict-

ing cross examination of the victim and the prosecuting attorney improp

(l) misrepresented that the defense attorne)'rvas guilty of illegal and

unethical misconduct in interviewing the victirn before trial.

(2) "testified" that the victim wa| telling the tnrr.h on the stand.

(3) stated his view of the proper method for the defense attorney lo in-

terview the victim.

({) misrepresented the law regarding interviewing government

rvitnesses.

(5) misrepresented that the victim had a right for both private counsel

and the prosecutor to be present when inten'ieu'ed by the tlefense counsel.

(6) represented that because an attorney was not present, [he defense

counsel's conduct was inexcusable.

(7) represented that he could validly file a grievance u'jth the Bar Asso-

ciation on the basis of the defense counsel's conduct.

(8) objtcted to defense counsel'g cross e-ramination of the rrctim.

(9) conrmented that the defendant had a violent narure.

( l0) gave his personal evaluation of the State's proof.

'l'he petitioner concedes that the state appellate court considered in-

stances 1,3, {. 5, and 9, but states without contradiction that the respond-

respondent's fourth ground for relief-that the state trial

judge improperly charged that "every witness is presumed to

srvear the truth"-the coutt nonetheless held that the jury

instruction, coupled with both the restriclion of counsel's

cross examination of the victim and the prosecutoy's "per-

sonaj testimonv" on the weight ofthe State's evidence, see n.

3, su,pra, violated the respondent's right to fair trial. In con-

clusion, the District Court stated:

"Also, subject to the qqestion ofexhaustion ofstate rem-

edies, where there is added to the trial atmosphere the

comment of the Attorney General that the only story

presented to the jury was by the state's witnesses there

is such mi-xture of violations that one cannot be sepa-

rated fi'om and considered independently of the others.

Under the charge as given, the iimitation of cross exami-

nation of the victim, and lhe flagrant prosecutorial mis-

conduct this court is compelled to find that petitioner did

not receive a fair trial, his Slxth Amendment rights were

violated and the iurv ooisoned bv the Drosecutorial

mrsconouct."'

ln ,t oilIiltrict Court considered several instances of

prosecutorial misconduct never challenged in the state trial

or appellate courts, or even raised in the respondent's habeas

petition.

In an unreported order, the Sifih Circuit affirmed the

judgment of the District Court, concluding that the couft

properly found that the respondent's constitutional rights

had been "seriously impaired by the improper [mitation of

his counsel's cross-examination of the prosecutrlx and by the

prosecutorial misconduct." The court specifically rejected

the State's argument that the District Court should have dis-

missed the petition because it included both exhausted and

unexhausted claims.

II

The petitioner urges this Court to apply a "total exhaus-

tion" n:le requiring district courts to dismiss e@taEEIs

See

and

corpus petition that contains both exhausted and unex-

hausted claims.i The petitioner argues at length that such a

ent did not object to the prosecutors statement that the victim \vas telling

the truth (#2) or to any of the several instances where the prosecutor, in

summation, gave his opinion on the weight ofthe evidence (#10). The pe-

titioner also notes that the conduct identified in #6 and #7 did not occur in

front of the jur"v, and that the conduct in #8, which was only an objection to

cross examination, can hardly be labelled as misconduct.

'The court granted the writ and ordered the respondent discharged

from custody uniess within 90 days the State initiated steps to bring a new

triai.

s adopted a "total exhaustion" rule

1978) (en banc

the courts of appeals, however, have permitted the district courts to re-

view the exhausted claims in a mixed petition containing both exhausted

and unexhausted claims. See. e. o., Katzv. King,627 F. 2d568, 574 (CAl

1980\; Cameron v. Fasto.lf ,5.13 t'. 2d 971, 976 (CA2 1976); United States ex

reL. Tratino v. Hatrack,563 F. 2d 116, 9l-95 (CAB 1977). cert. denied, 435

U. S. 928 (197$; Hetcett v. North Carolina,4It F. 2d l31ti, 1320 (CA4

1969); .}feeics v. Jago,548 F. 2d l3^1, 137 (CA6 1976), cert. denied, .134

U. S. &14 (1977"); Brou,n v. lf iscorrsirr State Dep't of PubLic Welfare, 157 F .

2d 25i, ?59 (CA?), cen. denied, .109 U. S. 862 (19i2): Tyler v. Srtenson,

{83 F. 2d till. 6l{ (CA8 l9?3); Whiteley v. Meacham,4f6 F. 2d 36, 39

(CAl0 1969), rev'd on other grounds, 401 U. S. 5{j0 (1971).

In Gooding v. iVilsoz, {05 U. S. 518 (19?2), this Court reviewed the

merits of an exhausted claim after expressly acknowledging that the pris-

oner had not e.x}austed his state remedies for all of the claims presented in

his habcas petition. Crtoding does not control the present case, however,

since the question of total exhaustion was not before the Court. Trvo

years later, in Francisco v. Gathright, {19 U. S. 59, 63-6.1 (1974) (per

cunom), the Court expressly resen'ed the question of whether $ 2254 re-

quires total exhaustion of claims.

erly alluderl to the

prejudiced by these

's violent nature, the respondent was not

v. Slole, 521 S.W-zd 591, 59L5fti

(Tenn. Crim. Aoo. 1974).

rict Court found that the prosecutor improperly:

5l) l,W .l'27,1 'I'ho llnitctl Srarr,.,r l,AW WIiIiK :l.Z-ll2

nrle furthers the policy of comily underlying the e.xheus[ion

doctrine because it gives the state courts the first opportu-

nity to correct fetleral constitutional errors and minimizes

federal interference and dismption of state judicial proceed-

ings. The petitioner also believes that uniform adherence to

a total exhaustion mle reduces the amount of piecemeal ha-

beas litigation.

Under the petitioner's approach, a clistrict court rvould dis-

miss a petition containing both exhausted and unexhausted

claims, giving the prisoner the choice of returning to state

court to litigate his une.xhausted claims, or of proceeding

with only his exhausted claims in federal courl. The petii

I tioner believes that a prisoner would be reluctant to ch-oose

j the latter route since a district court could, in appropriate cir-

/cumstances under Habeas Corpus Rule g(b), 2g U. S. C.

I $2254. dismiss subsequent federal habeas petitions as an

Gbuse of the writ.' In other words, if the prisoner amended

the petition to delete the unexhausted claims or immeriiately

refiled in federal eourt a petition aileging only his exhausted

claims. he could lose the opportunity to litigate his presently

unexhausted claims in federal court. This argument is ad-

dressed in Part C, infra, of this opinion.

In order to evaluate the merits of the petitioney's argu-

ments, we Lurn to the habeas sta tive history,

and the polici "'

crl,ly applied the e.xhaustion doctrine to habeas petitions con-

taining both exhausted and unexhausted claims.

In 1948, Congress codified the exhaustion doctrine in 2g

Y S 9. 9?254: citing Or parte Hawk as correcly staring

the principle of exhaustion.s S_ection 22b4,, horvei.er, doei

not directly address the problem of mixetl Jretitions. To be

sure, the provision states that a remeciy is-rri:c exhausted if

there e-dsts a state procedure to raise ,,the question pre-

sented," but we believe this phrase to be too arnbiguous t<.,

sustain the conclusion that Congress intende<.I to either per-

mit or prohibit review of mixed petitions. Because the legis-

lative history of,9D54, as well as lhe pre-1g48 cases, contiins

no referencg to the problem 9f mixed Le.!i!i9"n-s_,0 in all lik_eli-

hood Congress never thought of thg prqblemJ"^ Conse-

quently, we must analyze tle policies underlying the statu-

tory provision to determine its proper qcope. philbrook v.

Glodgett, 42L U. S. 707, 713 (19TS) (,,,[i]n expounding a srat-

ute, we must. . .look to the provisions of the rvhole larv, and

to its object and poliey.' [citations omitted],'): United States

v. Bacto-Unidisk,394 U. S. 78.1, ?99 0969) (,,where the stat-

ute's language seem[s] in-sufficiently precise, the ,naturai

way' to draw the line 'is in light of the statutory purpose' [ci-

tation omitted)"); United Stotes v. Sisson, Bgg U- S. 267,

297-298 (i970) ("[t]he axiom that courts should endeavor to

give statutory language that meaning that nurtures the poli-

rpj bar relief where the state remedies are inadequate or fail to ..atTord

a

full and fair adjudication of the federal conrentions raised." E,t parte

Hauk,32l U. S. 114, 118 (1944).

"The Revisey's Notes in the appendlx ofthe House Repoft states: ,,This

new section [$ 25a] is declaratory of eristing law as affirmed by the Su-

preme court. (see Etparte Horu&, 19.14, 0l s. ct. 4.t8,321 u. s. 114. gg

L. Ed. 572.)." H.R. Rep. No. 808,80th Cong., lsr Sess., Al80 (1947).

See also Donv. Burford. 339 U. S. 200, 210 (1950) (,.1n !2&i4 of the l94t]

recodification of the Judicial Code, Congress gave legislative recognitron to

lhe Ha**k ru.le for the exhaustion of remedies in the state courts and this

Coun."); Brou,tr. v. Allen, SM U. S. 44i], 44HS0 0953); {gC.-". l'r.lS.!!guE rgl"-l&t (1e60.

'Section 325{ in part provides:

"(b) .{n appiication for a writ of habeas corpus in behalf of a person in

custody pursuant to the judgment of a State court shal.l not be granted un-

Iess it appears that the applicant has exhausted the refrEdies available in

the courts of the Stare. gI that there is either an absence of available State

correctlve process or th'e e.ristence of circumstances rendering such pro-

cess ineffective to prot€cr the rights of the prisoner.

(e) Ar applicant shall not be deemed to have exJiausred rhe remedies

avai.lable in the courts of the State, within the meaning of this section. if he

has the right under the law ofthe State to raise, by an_,- available proce-,/

dure, the question presented." v

'o Section 2*1 u'as one small par.t of a comprehensive revision of the Ju- \

dicial Code. The o.ng11al veplo1of $ 22Sf , as passed b1r the House, pro- I

vided that:

"ila appl.ication for a *rit of habeas corpus in behalf of a penon in custody

pursuanr to the judgment of a State cowt or authority of a Sute officer I

shall not be granted unless it appears that the applicant has exhausted the

remedies available in the courts ofthe State, or that there is no adequateA

Lellggy syal]&l:. in such courts or that such couts have denled irim i-fE'

'

adjudication of the lega[ty of his detention under the Constitution and laws

of the United States."

Thc Senatc amended the House bill. changrng the House version of 0 21|54

to its prcsent form. The Senate Report accompanying the bill states that

one purpose of the amendment was ,'to substitute detailed and specific lan-

guage for the phrase 'no adequate remedy available.' That phrase is not

sufficiently specific and precise. and its meaning should, therefore. be

spelled out in more detail in rhe section as is done by the amendment.,, S.

Rep. No. 1559, 8fth Cong., 2d Sess., l0 0948). The House accepted rhe

Senate version of the Judicial Code without further amendment.

In 1966, Congress amended the $2254 to adcl subsection (a) and rerjes-

ignate the existing paragraphs as subsecLions (b) and (c). See pub. L.

E9-7r1, $ 2 (e), 80 Stat. 1105.

" See Note, Habeas Petitions rvith Exhausted and Unexhausted Claims:

Speedy Release, Comity and Judicial Eticiencl., J7 B.U.L. Rev. g6{. 36?

n. 30 (1977) (suggesting that before lg{8 habeas peritions did not contain

multiple claims).

IA

III

A

The exhaqqtion doctrine existed lons before its codification

Uy Congr-ffi-f5lE-ii7 r parte Roiatt.ltT U. S. Z4t,ZSt

(1886), this Court wrote that as a matter of comity, federal

courts should not consider a claim in a habeas corpus petition

until after the state courts have had an opportunity to act:

"The injunction to hear the case summarily, and there-

upon 'to dispose of the party as law and justice require'

does not deprive the court of discretion as to the time

and mode in which it will exert the powers conferred

upon it. That discretion should be exercised in the light

of the relations existing, under our system of govern-

ment, between the judicial tribunals of the Union anci of

the States, and in recognition of the fact that the public

good requires that those relations be not disturbed by

unnecessary conflict bettveen courts equally bound to

guard and protect rights secured by the Constitution."

Subsequent cases refined the principle that state remedies

must be exhausted except in unusual circumstances. See,

e. 9., United States, ex rel. Kennedy v. Tyler,269 U. S. 18,

17-19 (1925) (holding that the lower court should have dis-

missed the petition because none of the questions had been

raised in the state courts. "In the regular and ordinaqv

course of procedure, the porver of the highest state court in

respect of such questions should frst be exhausted."). In

Et parle Hawk,'321U. S. 114, fiZ tt9++1, this Court reit-

erated thatlggiin@as the basis for the exhaustion doctrine:

"it is a priniiple c()ntrolling all habeas corpus petitions to the

federal courts, that those courts will interfere with the ad-

ministration ofjustice in the state courts only 'in rare cases

where exceptional circumstances of peculiar urgency are

shown to exist."'? None of these cases, horvever, specifi-

'Rule 9 (b) provides that:

"A second orsuccessive petition may be dismissed ifthejudge finds that it

fails to allege new or different grounds for relief and the prior determina-

tion was on the merits or, if new and different grounds are alleged, the

judge finds that the failure of the petitioner to assert those grounds in a

prior petition constituted an abuse of the srit."

'The Court also made clear, however, that the exlaustion doctrine does

^

I

:t-2.tt2 'I'lut llnitetl Srrrles LAW WIitiK lr0 LW 4'275

^r\

any c

l( l Tlr

llrr l1r.

eics underlying the legislation is o,re that guides us when cir-

cumstances not plainly covered by the terms of the statuto

are subsumed by the underlying policies to which Congress

was committed"); Llnercell,ed Chemical Crtrp. v. United

States,345 U. S. 59, 64 (1953) ("[a]rguments of policy are rel-

evant when for example a statute has an hiatus that must be

filled or there are ambiguities in the legislative language that

must be resolved").

B

The exhaustion doctrine is principally designed to protect

the state courts' role in the enforcement of federal Iaw and

prevent disruption of state judicial proceedings. See

Braden v. 30th Judicial Circuit Cou,tl of Kentucky, 410

U. S. 4&1, 490-191 (1973)." Under our federal system, the

fetleral and state "courts [are] equally bound to guard and

protect rights secured by the Constitution." Ea parte Roy-

all, su,pra, aL 251. Beeause "it would be unseemly in our

dual system of governntent for a federai district court to

upset a state court conviction without an opportunity to the

state courts to correct a constitutional violation," federal

courts apply the doctrine of comity, which "teaches that one

court should defer action on causes properly within its juris-

diction until the courts of another sovereignty with concur-

rent powers, and already cognizant ofthe litigation, have had

an opportunity to pass upon the matter." Darr v. Bzr,rford,

339 U. S. 200, 204 (1950). See Du.ckworth v. Senano, 451

U. S.

-

(1987) (per uriam.) (noting that the exhaustion re-

quirement "serves to minimize friction between our federal

and state systems of justice by alloutng the State an initial

opportunity to pass upon and correct alleged violations of

prisoners' federal rights").

A rigorously enforced total e.xhaustion rule will encourage

state prisoners to seek full relief first from the state courts,

.. thus giving those courts the first opportunity to review all

claims of eonstitutional error. As the number of prisoners

who exhaust all of their federal claims increases, state courts

may become increasingly famiiiar with and hospitabie toward

federal constitutional issues. See Braden v. 30th Judicial

Circuit Court of Kentucky, supra, at 490. Equally as impor-

tant, federal claims that have been fully exhausted in state

courts will more often be accompanied by a complete factual

record to aid the federal courts in their review. Ct. 28

U. S. C. $ 2254 (d) (requiring a federal court reviewing a ha-

beas petition to presume as correct factual flndings made by a

state court).

The facts ofthe present case underscore the need for a rule

encouraging exhaustion of all federal claims. In his opinion,

the district court judge wrote that "there is such mlrture of

violations that one cannot be separated from and considered

\ independently of the others." Because the trvo unexhausted

I claims for relief were intertwined with the exhausted ones,

I the judge apparently considered all of the claims in ruling on

the petition. Requiring $ismissal of petitions containing

both exhausted and unexhausted claims will relieve the dis-

trict courts of the difficult if not impossible task of deciding

rvhen claims are related, and will reduce the temptation to

eonsider unexhausted claims.

In his dissent, JUSTtcr Srevrus suggests that the District

Court properly evaluated the respondent's trvo exhausted

clainrs "in the context of the entire trial." Post, al 4. Un-

, questionably, however, the District Court erred in consicler-

I ing unexhausted claims, for $2251(b) expressly requires the

I prisoner to e.xhaust "the remedies available in the court of

I the State." See n. 9, supro. Moreover, to the extent that

''Ste alsu l)evclopments. l.'crloral Il:rbca-s Corpus, 33 Huv. L. Rcv.

l0lJ8, 109.1 (1970) (cited favorably in Bratlenl.

exhausted and une.xhauste<l claims are interrelaled,

efal ruleJ.mons the ?u.ts,of apleg.ls is,to.dismiss

beaqg4ilt-qgq_for exhLustion of all such claimsj

r ri6tn : Ifr n"i c k. 549 F. ffi tm3-i9mi :mi

oea!_Lel]:ll-9nlror elnw bee €. 9.,

rriFt;tn : Ifri"ick, 54s F. ffileIF-lf,fiiffiiter v. Hiu,

536 F. 2d 967 (CAl l9i6); Hewett v. North CaroLina, 4L5 F.

2d 1316 (CA4 1969).

Rather than an "adventure in unnecessary lawmaking"

(StnveNs, J., post, at 1), our holdings today reflect our inter-

pretation of a federal statute on the basis of its languago and

legislative history, and consistent u'ith its uncierlying poli-

cies. There is no basis to believe that today's holdings will

"compiicate and delay" the resolution of habeas petitions

(Srnvoxs, J., post, at 13), or uill serve to "trap the unwary

pro se prisoner." (BlacxltuN, J., post, at g). 0n the con-

to use t machinery, so too should lhey

be able to master this stlaightfonilald e$gslion__Iggilg-

menL Those prisoners rvho misunderstand this requirement /

and submit mixed petitions nevertheless are entitled to re- [

submit a petition with only e.xhasuted claims or to exhaust I

the remainder of their claims.

Rather than increasing the burden on federal coufts, strict

enforcement of the exhaustion requiremenl u'i1l encourage

habeas petitioners to

and to present the feder

To the e.xtent that the exhaustion requirement reduces piece-

meal litigation, both the courts and the prisoners should ben-

efit, for as a result the distlicl court u'ill be more likely to

review all of the prisoner's claims in a single proceeding, thus

providing for a more focused and thorough revierv.

C

The prisoner's principal interest, of course, is in obtaining

speedy federal relief on his claims. See Braden v. J?th J tLdi-

cial Cirutit Court of Kentucky, supra, at 490. A total ex-

haustion rule will not impair that interest since he can always

amend the petition to delete the unexhausted claims, rather

than returning to state court to exhaust ail ofhis claims. By

invoking this procedure, however, the prisoner would risk

forfeiting consideration of his unexhausted claims in federal

court. Under 28 U. S. C. $2254 Rule 9(b), a district court

may dismiss subsequent petitions if it finds that "the failure

ofthe petitioner to assert those [new] grounds in a prior peti-

tion constituted an abuse ofthe wdt." See n. 6, szpro. The

Advisory Committee to the Rules notes that Rule 9 (b) incor-

porates the judge-made principle governing the abuse of the

writ set forth in Sanders v. United States,373 U. S. 1, 18

(1963), where this Court stated that

"if a prisoner deliberately withholds one of two grounds

for federal collateral relief at the time of flIing his first

application, in the hope of being granted two hearings

rather than one or for some other such reason, he may be

deemed to have rvaived his right to a hearing on a second

application presenting the withheld ground. The same

may be true if, as in ll/otg Doo, the prisoner deliberately

abandons one of his grounds at the first hearing. Noth-

ing in the traditions of habeas corpus requires the fed-

eral courts to lolerate needless piecemeal litigation, or to

entertain collateral proceedings rvhose only purpose is to

vex, harass, or delay."'r

'' ln lfrrrro Doo v. United Sla/r.r, 2li5 U. S. 239 (192{), the petitioner

brought trvo hubra.r co4rus petitions to obtain release from the custo(ly oft

deportation order. The ground for relief contained in the second petition

/

claims to)lalms to Ieoeral coun, De sure [nal you nrst have taken

one to state coq4l11Just as pl'o se petitioners have man-

I->0 LW ,1.27(r Tlrc linitctl Srarcs LAW WEIIK 3-2-82

See Advisory Committee Note to Habeas Corpus Rule 9(b),

28-U. S. C., p. 273. Thus a prisoner rvho decides to proceed

only u'ith his exhausted claims and deliberatelv sets aside his

unexhausted claims risks dismissal of subsequent federal

petitions.

IV

In sum, because a total e.rhaustion rule promotes comity

and does not unreasonably impair the prisoner,s right to re-

Iief. we hold that a district court must dismiss habeas peti-

tions containing both unexhausted and exhausted claims.,n

Accordingly, the judgment of the Court of Appeals is re-

versed and the case remanded to the District Court for pro-

ceedings consistent with this opinion.

/t is so ordered.

Jusncr BlecxuuN, concurring ln the judgment.

The important issue before the Court in this case is

whether the conservative "total exhaustion" rule espoused

norv by t'wo Courts of Appeals, the Fifth and the Ninth Cir-

cuits, see ante, at 4. n. 5, is required by 28 U. S. C.

$$ 2254(b) and (c), or whether the apprygg.!_qg!-o,plsdhfeielt

A

The Courl correctly observes, ante, aL ?-8, that neither

the language nor the legislative history ofthe exhaustion pro- ,

visions of $$ 2251(b) and (c) mandates dismissal of a habeas

petition containing both e.xhausted and unexhausted claims.

Nor does precedent dictate the resuit reached here. In pi. j

card v. Connor,404 U. S. 270 (1971), for example, the Court

ruled that "once the federal clairn has been fairly presented

to the state courts, the exhaustion requirement is satisfied.,'

Id., at 275 (emphasis supplied). Respondent complied with

the direction in Picard with respect to his challenges to the

trial court's limitation of cross-examination of the victim and

to at least some of the prosecutoy's ailegedly improper

comments.

ate treatment of mixed habeas petitions, thei' plainly suggest

that state courts need not inevitably be given every opportu-

nity to safeguard a prisoner's constitutional rights and to pro-

vide him relief before a federal court may entertain his ha-

beas petition.'

B

In reversing the judgment of the Sixth Circuit, the Court

focuses, as it must, on the purposes the exhaustion doctrine

is intended to serve. I do not dispute the importance of the

exhaustion requirement or the validity of the policies on

rvhich it is based. But I cannot agree that those concerns

rvill be sacrificed by permitting district courts to consider er-

lnusted habeas claims.

The first interest relied on by the Court involves an off-

shoot of the doctrine of federal-state comity. The Court

hopes to preserve the state courts' role in protecting con-

stitutionai rights, as well as to afford those courts an op-

portunity to correct constitutional errors and-somewhat

patronizingly-to "become increasingly familar with and

hospitabie toward federal constitutional issues." Ante, at

10. My proposal, however, is not inconsistent with the

Court's concern for comity: indeed, the state courts have oc-

casion to rule first on every constitutional challenge, and

have ample opportunity to correct any such error, before it is

considered by a federal court on habeas.

In some respects, the Cour!'s ruiing appears more destruc-

tive than soiicitous of federal-state comity. Remitting a ha-

beas petitioner to state bourt tr-r e.xhaust a patently frivolous

claim before the federai court may consider a serious, ex-

hausted ground for relief hardly demonstrates respect for the

state courts. The state judician/s time and resources are

'ln Brou'n v. Allen,3J4 U. S. 4,{.3, 147 (1953), the Court made clear that

the eiFausiiofrfl6tiffi'e does not foreclose federal habeas relief rvhenever a

state remL,dy is available; once a prisoner has presented his claim to the

highcst state cou-rt on direct appeal, hlneed not seek colleterel ralial fren

the State. Additionallffi-Fidai v. ,toth Jrtdicial Ctrcuit Court of Ky.,

{ l0 U. S. .184 ( 1973). the Court permitted consideration of a $ 25.1 petition

seeking to force the State to afford the prisoner a speedy trial. Although

the defendant had not 1'et been conlicted, and therefore obviously had not

utilized all available state procedures, and although he could have raised

his Sixth Amendment claim as a defense at trial. the Coun found the inter-

ests underlfing the exhaustion doctrine satisfled because the petitioner

had presented his existing constitutional claim to the state courts and be-

cause he \\'as no! attempting to aboft a state proceeding or disrupt the

Statesjudicial process. See id.. ar.l9I. Finally, in Rohertsv. LaVallee,

&-'t9 U. S. -10 (I967). t)re Courl held that an inren'ening change in the rele--]

vrnL state larr'. whtch ha<l occurred subseouent to the orisoner's e-rhaustion /

of state remerlies anrl rrhiclr suggesrefiFf-[h-8.,.," .or*. rvoul<l look fa- |

vorably on the request tbr relief, (lid not necessitate a return to strte coun. /

I

other Courts o!l@ mar:eyierr:

the erhau.sted claims of a m!5ed-petilio.ru-isthe ploper int_ej-

prititi6n ofttra r1-atute. dThis ba.i. issue, i-flrmtv agree

Ao nofdi6F'uitthe value of comlty rvTren it is applicable

and prodl.rctive of harmony betrveen state and federal couns,

nor do I deny the principle of exhaustion that 992254(b) and

(c) so elearly embrace. What troubles me is that the "tdtal

exhaustion" rule. now adopted by this Court, can be read into

the statute, as the Court concedes, ante, at 8, only by sheer

frrrce; that it operates as a trap for the uneducated and indi-

gent pro se prisoner-applicant; that it delays the resolution of

claims that are not fi'ivolous: and that it tends to increase,

rather than to alleviate, the caseload burdens on both state

anrl federal courts. To use the old e.xpression, the Court,s

ruling seems to me to "throw the baby out with the

bathrvater. "

Although purporting to rely on the policies upon rvhich the

exhaustion requirement is based, the Court uses that doc-

trine as "a blunderbuss to shatter the attempt at litigation of

constitutional claims without regard to the purposes that un-

derlie the doctrine and that called it into existence." Braden

v. J}tlt JudiciaL Circuit Couri of Ky.,4L0 U. S. 484, 490

(1973). Those purposes do not require the result the Court

reaches; in fact, they support the approach taken by the

Court of Appeals in this case and call for dismissal of only the

unexhausted claims of a mixed habeas petition. Moreover,

to the extent that the Court's ruling today has any impact

rvhatsoever on the workings of {ederal habeas, it will alter, I

fear, the litigation techniques of'very few habeas petitioners.

was also contained in the first petition. but had not been pulsued in the

first habeas proceetling. The Court held that because the petitioner "had

full opponunity to offer proof in the first hearing, the lorver court should

not consider the second petition. Itl., at 2lL. The present case, rtf

course. is not controlled by Wong Doo because the respondent could not

have litigated his unexhaustetl claims in federal coun. Nonetheless, the

case provirles some guidance for the situation in tvhich a pnsoner deliber-

ately decides not to exhaust his claims in state court before filing a habeas

corpus petition.

'' Because of our disposition of this case, we do not reach the petitioner's

claims that the grounds offered by the respondent do not men! habeas

relief.

Coq{ fails to note, moreover, thal

utilize everv a

e.xhaustion rement. Although this

n

:t-2-tt2 'Ilrc lirtit?tJ st(tte.s l,AIir WI,ltlK .50 r.w 4277

a-

then spent rc,jecting the obviously meritless unexhausttd

claim, rvhich doubtless will receive littie or no attention in the

subsequent fer-leral proceeding that focuses on the substantial

e.xhausted claim. I can "conceive of no reason why the State

would wish to burden its judicial calendar with a narrow issue

the resolution of which is predetermined by established fed-

erul principles." Roberts v. LallaLlee, 369 U. S. 40, J3

( 1967).'

The second set of interests relied upon by the Court in-

volves those of federal judicial administration--ensuring that

a $2254 petition is accompanied by a complete factual record

to facilitate review and relieving the district courts of the

responsibility for determining.when e-xhausted and unex-

hausted claims are interrelated.'jJf a prisoner haS presented

a particulai challenge ln lhe stite .ourts, howevei, the ha-

beas court will have before it the complete factual record re-

lating to that claim.' And the Court's Draconian approach is

hardly necessary to relieve district courts of the obiigation to

consider exhausted grounds for reiief when the prisoner also

has advanced interrelated claims not yet reviewed by the

state courts. When the district court believes, on the facts

of the case before it, that the record is inadequate or that full

consideration of the exhausted claims is impossible, it has _a]-

wqyp_been free to dismiss the entire_heb*s pqlilr_ql pgndgg

resolution of unexhausted ciaims in the state courts. Cer-

tainly,itmakesieniii'GTarnmrTlfe-stddEGlons1o-ttrediscre-

tion of the lower federal courts, which will be familiar with

the specific factual context of eactllase*

The federal courts that have addressed the issue of inter-

relatedness have had no dfficulLy distinguishing related from

unrelated habeas claims. Mixed habeas petitions have been

dismissed in toto when "the issues before the federal court

logically depend for their relevance upon resolution of an un-

exhausted issue." Miller v. Hall, 536 F. 2d 967, 969 (CAl

1976), or when consideration of the exhaustecl claim "wouid

necessarily be affected . . ." b)' the unexhausted claim,

United Stales er rel. tllcBride v. Fay,370 F. 2d 547, 5.18

(CA2 1966). Thus, some of the factors to be considered in

determining rvhether a prisoner's g:r"ounds tbr collaterai relief

are interrelated are whelLher the claims are based on the

sameconstitutional-1.,gtGfi-Cfrglt*^rg,_qndrvhetherthey

rqqqire an underslanrtingof.lhe _totality_oI fhe_cireumstances

e4 qg!@of-t he.eqtile record.

C o m pari 7o /r,t s o n v .

-dfr E dS t a t;{ Di'sli.i;l e ifu,rt, ffia

738. 740 (CAS 1975) (prisoney's challenge to the voluntariness

of his guilty plea intertrvined with his claims that at the time

of the plea he was mentally incompetent and rvithout effec-

tive assistance of counsel); United States ex rel. DeFlumer v.

JIanutsi,380 F. 2d 1018, 1019 (CA2 1967) (dispute regarding

'The Court fails to mention trvo related state interests relied upon by

the petitioner warden-ensuring finality of conr-ictions and avoiding the

mooting of pending state proceedings. The finality of a conviction in no

rvay depends, horvever. on a feileral court's treatment of a mixed habeas

petition. If a State is concemed with finality, it may adopt a rule directing

defendants to present all their claims at one time; a prisoner's failure to

adherc to that proeedural requirement, absent cause and prejudice, would

bar suhsequent federal habeas relief on arlditional grounds. See Wnin-

unight v..Sir/res, 43:l U. S. 72 (1977): .I/rrrclr v. ,lloltxnn, {09 U. S. {l

( l1)?ll). As long as the State permits a prisoner to continue challengrng his

conviction on alternative grounds, a federal court's (lismissal ofa mi-red ha-

beas petition rvill provide no particular incentive for consolidation of all po-

tential claims in a single state proceeding.

A pending state proceeding involving claims not included in the prison-

ers federal habeas petition rvill be mooted only if the federal coun grants

the applicant relief. Even in those cases, though. the state couns rnll be

saved the trouble of undenaking the useless exercise of ruling on unex-

hausted claims that are unnecessar), to the disposition of the case.

'The distnct court is free, ofcourse. to order expansion oithe record.

See 23 U. S. C. I 225{ Rule 7.

the voluntariness of the prisoney's guilty plea "'would neces-

sarily affect the consideration ofthe coerced confession claim,

because a voluntary guilty plea entered on advice of counsel

is a rvaiver of ail non-jurisdictional defects in any prior stage

of the proceedings"); United States er rel. McBritle v. Fay,

370 F. 2d. at 548; and United States ex rel. f,Iartin v.

McMann,,ll.l8 F. 2d 696, 898 (CAz 1905) (defendant's chal-

lenge to the voluntariness of hie confecsion reisted to his

ciaim that the confession was obtained in violation of his right

to the assistance of counsel and without adequate warnings),

with Miller v. HaLl,536 F. 2d, at 969 (no problem of interre-

lationship when exhausted claims involved allegations that

the police lacked probable cause to search defendant's van

and had no justification for failing to secure a search warrant,

and unexhausted claim maintained that the arresting officer

had committed perjury at the suppression hearing); and

United States er reL. Leug v. McilIantt,394 F. 2d 402,404

(cAz 1968).

The Court's interest, in efficient administration of the fed-

eral courts therefore does not require dismissal of mired ha-

beas petitions. In fact, that concern militates against the

approach taken by the Court today. In order to compiy with

the Court's ruling, a federal court now will have to review the

record in a $ 254 proceeding at least summarily in order to

deterznine whether all claims have been exhausted. In many

cases a decision on the merits will involve only negligible ad-

ditional effort. And in other cases the court may not realize

thal one of a number of claims is unexhausted until after sub-

stantial rvork has been done. If the district court must nev-

ertheless dismiss the entile petition until all grounds for re-

Iief have been exhausted, the prisoner wiil likely retunl to

federai court eventually, thereby necessitating duplicative

examination of the record and consideration of the exhausted

claims-perhaps by another district judge. See Justlcp

SrevBNs' dissenting opinion, post, at7-3. Mo-reover, whery

the $ 2254 petition does find its rvay back to federal court, thd

record on the exhausted grounds for relief malllye[ be" stale

and resolution of the merits more difficult.' 1-

The interest of the prisoner and of society in "preserv[ing]

the writ of habeas corpus as a 'swifb and imperative remedy

in all cases of illegal restraint or confinement,"' Braden v.

30tlr Ju.dicial CirctLit Court of Ky.,410 U. S., at 490, is the

final policy consideration to be weighed in the balance.

Compelling the habeas petitioner to repeat his journey

through the entire state and federal legal process before re-

ceiving a ruling on his exhausted claims obviously entails sub-

stantial delay.' And if the prisoner must choose between

undergoing that delay and forfeiting unexhausted claims, see

ante, aL 11-13, society is likewise forced to sacrifice either

the swiftness of habeas or its availability to remedy all uncon-

'A related federal interest mentioned by the Court is avoiding piece-

meal litigation and encouraging a prisoner to bring all challenges to his

state court conviction in one $ 22.lil proceeding. As discussed in part II,

irr/io, however, the Court's approach cannot promote that interest because

Congress has expressly permitted successive habeas petitions unless the

suhsequent pctitions constitute "an abuse of the writ." 28 U. S. C. $ 2254

Rule 9(bt.

'ln [.]nited. States ex rel. lning v. Cossc/es, .148 F. 2d 711, 712 (CA2

l97l), cert. denied. .ll0 U. S. 925 (1973), and United States er rel.

DeFlurner v. .l/onarsi, 380 l'. 2d 1018, l0l9 (CA2 1967), for example,

mixed habeas peritions wcre tlismissed because the exhausted and unex-

hausted cla.ims rvere interrelated. In each case, the prisoner rvas unable

to obtain a federal court judgment on the merits of his e.xhausted claims for

5'ears. See United States et rel. ln'ing v. Henderson,37l F. Supp. 1266

(SDNY 197{): L'nited States et rcI. DeFLu.mer v. )lanaLsi,4.i3 F. 2d 940

(CA2). cert. denied. .104 U. S. 9l{ (1971).

any (

ll('l:i'n

llte P'

I t,

5t) t,\\/ ,l27tB T'hc lJnitetl Srarcs l,A\v WIIEK :t-2-82

stitutional imprisonments., Dismissing only une.rhausted

grounds for habeas relief, while ruling ori'the rnerits of all un_

related exhausted claims, will diminlih neither the prompt-

nes.s nor the efficacy of-the remecly and, at the same tirie,will serve the state and federal interesis described by the

Court.T

II

.

Thc (lourt's misguided approach appears to be premised onthe spectre of ,,the sophijticated hiigiou, prisoner intent

upon a strategy of piecemeal litigation . . . ,"ivhose aim is to

have more than one day in couit. Galtieri v. Wainwright,

582 F'. 2d 348, 369 (CAS l9Z8) (en banc) (dissenting opinion).

Even if it could be said that the Courtis vierv accurately re_

flects realit;r, its ruling today will not frustrate the perry Ma-

sons of the. prison populations. To avoid dismissai, they will

simply include only exhausted claims in each of many suc-

cessive habeas petitions. Those subsequent petitions may

be disnrissed, as Justtcp BRrurseN ob."*.., only if thlprisoner has "abused the. rwit,, by deliberately choosing, for

purposes of delay, not to include all his craims in one petition.

See posl, at 4-5 (opinion concurring in par! and dissenting inpaft). And successive habeas petiiions that meet the ,,ab"use

of the writ" standard have ahviys been subject to dismissal,

irrespective of the Court,s treaiment of mi.xed petitions to_day. The Court's ruling in this case therefore provides no

additional incentive whatsoever to conso[date all groutrds forrelief in one $ 2254 petition.

,Insteld of deterring the sophisticated habeas petitioner

u'ho understands, and wishes to circumvent, the rules of ex-

haustion, the Court,s mling will serve to trap the unwary pro

se prisoner who is not knorvredgeable about the intricaciei ofthe exhaustion doctrine and rv-hose only aim is to secure a

new trial or release from prison. He will consoiidate all con-

ceivable grounds for reiiefin an attempt to accelerate review

and minimize costs. But, under the iourt,s approach, if he

unwittingly includes in a g 2254 motion a claim not yet pre_

sented to the state courts, he risks dismissal oftne entlre pe_

tition and substantial cielay before a ruling on lhe mer.its ofhis e.xhausted claims.

'The petitioner warden insists, however, that improved judicial effi-

ciency will benefit those prisoners u'ith meritoriou.

"1"i.. because theirpetitions will not be lost in the floorl of fivolous $ 22&l petitions. Even ifthe court's approach were to contributerto the emci*i aaministration ofjustice, the contours of the exhaustion doitrine have no relationship to the

merits of a habeas pet ltion: a prisoner with one substantial exhaustetl claimwill be forcerl to return to state court to litigate his ramatning challenges,

rvherears a petitioner with frivolous, but exhaustetl, claims will ieceive, it isto be hoped. a prompt ruling on the merits from the fer.rerar court, See

STEYENS. J., rlissenting, pdsr, at g.

'Even the Fifth and Ninth Circuits, rvhich require rlismissal of mixed

habeas petitions in the tl.pical crse, rlo not follorv itu o*ii.rn" position the

c-ourt tnkes to(lay. The Ninth circuit permits <ristric! courts to consi(rer

the exhausterl grounds in a mixed petition if the p,i.or". h". a reasonable

explanation for failing to exhaust the other claiins or if the state cou.rts

have delayed in mling on those claims. See Gortzalts rl. Storr. 546 F. 2d807, 810 (CAg 1976). The t'ifth Circuit rvill revierv the menrs of ex-

hausted claims contained in a mixed petition if the District Court has con-

sideretl those claims. See Galtiei v. V,ainmgltt,;SZ i. :a 3.1g, 3rjl_J62(CA5 1978) (en bancr.

t:ourt itself to djsmiss une.xhausterl grountls tbr rel.iet.I fear, howcver, that prisoners-who mistakeniy-g1r[ryft

rdxed pelirions mav nor be_trsrr,ed_udforinly. e pionJ,

opportunity to amend a $ 2251 petition may depenci on his

awareness of the existence of that alternatir e or on a sympa_

th.etic.district judge who informs him of the option

"rd

p"r_

mits the amendrnent. See Fed. Rule Ctu. giog.&Grj if

lfe prisoner-is re$rired roffi;lhE-peurror mr ffikncttsge,.t *gted .!4q!s, hL r_nar_t eyglsi%I" Ib;iffi

3-YiE-Jhus encounter suhst;ii;i eJ,y1"r^"" ht"

-""*

plaint agai! comes to ,the district court,s attention. See

STEVENS, J., post, at &9, n. lb.

Aclopting a ruje that will afford knowledgeable prisoners

more favorable treatment is, I believe,

"nlith"ti.ul to the

purposes of the habeas writ. Instead of requiriag a habeas

petitioner to be familiar with the nuances of the Jxhaustion

doctrine and the process of amending a complaint, I tvould

simply permit the district court t; dismiss unexhaustecl

grounds ior relef and consider exhausted claims on the

qeritsr..

III

. Although I would affirm the Court, of Appeals, ruiing that

the exhaustion doctrine requires dismissal of only theinex-

hausted claims in a mi-xed habeas petition, I u,ouid remand

the case for reconsideration of the merits of'.e*p-61-- ,il

stitqlionel -qrgrrment5. As the Court notes, the bistr.ict

Court erred in considering both exhausted and unexhausted

claimsrvhen ruling on Lundy's $2254 petition. See ante, a,t

?j. .

Th: Court of Appeals artempted to recharacterize theDistrict Court's grant of reijef as premised on only the ex_

h.austed claims and ignored the District Court,s conclusionthat the exnausted and unexhausted claims were interre_lated. See App. 95-96.r

Even were the Court of Appeals, recharacterization accu-

rate, that cout affirmed the District Court on the ground

that reipondent's constitutional rights t"J Uu.n ,.seriously

impaired by the improper limitation of his counsel's cross-

examination of the prosecutrlx and by the prosecutorial mis-

conduct." Id., at g6. The court does not appear to have

specified rvhich allegations of prosecutorial misconduct it con-

sidcred in reaching this conciusion, and the record does not

reflect rvhether the court improperly took into account in_

stanres of purported misconduct that respondent has never

challenged in state court. See ante, at 2 n. B. ,This ambigu-

ity is of some importance because the court's general sta-te-

ment does not indicate whether the court would*have granted

habeas relief on the confrontation claim aione, or whether its

judgment is based on the combined effect of the limitation of

cross-examination and the asserted prosqcutoriai miscon{,ucl.I therefore would remand the case, directing tfraf'lfre

courts below dismiss respondent,s unexhausted claims and

examine those that have been properly presented to the state

courts in order to determine whether they

"re

interrelated

with th.e unexhausted grounds and, if not, *h.th"" they war_

rant collaterai relief.

Jusrrcp BneNxeru, u'ith whom Jusuce MensHell joins,

concurring in part and dissenting in part.

I join the opinion of the Court (parts I, II, III-A, III-B,

.'This Coun implies approval of the District Court,s finding ofinterrelat-

eclness, see ante, at l(). but I arn not convinced that the District Court,s

conclusion rvas compelleti. Conceivably, habeas relief couid be justified

only on the basis ofa determrnation that the cumulative impact ofihe four

alleged errors so inl'ecred the rrial as to violate respondeni,s clue process

rights' But Lundys four elaims. on rheir face, are <iistinct in terms of the

factua.l allegations and legal conclusions on rvhich they depend.

3-2-lt2 'l'ho llrtitetl ,5/arcs LA\V WliUl( .50 t.\\/ 427.)

6

anrl IV, arlr1, l;ut I rlo not join in the opinion of the plurali'.y

(l'art III-C, rur/e). I:rgree rvith the Crrurt's holding that the

exhaustion requireme-nt of 28 U. S. C. $?251(b)-(c) obliges a

tbrleral rli-.stricl court to dismiss, without consideration on the

merits, a habeas corpus petition from a state prisoner rvhen

that petition contains clainrs that have not been exhausted in

the state coults, "leaving the prisoner with the choice of re-

turrring t() state coult to e.xhaust his claims or of amending or

resubmitting the habeas petiti.on to present only exhausted

claims to the district court." Arte, at L. But I disagree

rvith the plurality's vierv. in Patt III-C, that a habeas peti-

tioner nrust "risk forfeiting consideration of his unexhaus[etl

claims in iederal court" if he "decides to proceed only r.rith his

exhausted claims and deliberately sets aside his unexhausted

claims" in the face of the district court's refusal to consider

his "mixed" petition. Ante, at 12. The issue of Rule 9(b)'s

proper application to successive petitions brought as the re-

sult of our tlecision today is nol bofore us-it was not itlnollll

the tlucstions presented by pc.titioner, nor was it brieletl anrl

argued b1' the parties. Therelirre, the issue should not be

adch'essed until u'e have a case plesenting it. In any event,

I rlisagree rvith the pluralit.,-'s proposed clisposition of the

issue. In my view, Rule 9(b) cannot be reacl to permit clis-

, missal of a subsequent petition uncler the circumstances de-

r scribed in the plurality's opinion.

I

The pluralitl' recognizes, as it must. that in enacting Rule

9(b) Congless explicitly adopt-gd the-'labusq of the ri'rit" stan-

rlard announced in falrlers v. L'rrited Slnles'\ 373 U. S. I

( 1963). Ante, at 12. T&--ie.ru.la!-ir:e histqryrof Rule 9(b) il-

lustrates the meaning of that standard. As transmitteti b1'

this Court to C-onetress, Rule 9(b) read

-as

follou's:

"succrsstve PeurIous. A seconcl or successive pe-

tition may be dismissed if the judge fincls that it fails to

allr.,ge nerv or different pp'ounrls for relief and the prior

rletermination \\'as on the merits g, if new and different

glounrls are alleged, the judge firids that the failure of

the petitioner to assert those glounds in a prior petition

is rrol e.r'crrsob/e." H. Rep. No. 94-1471, p. I (1976) (em-

phasis arlcled).

The interpretive gloss placed upon proposed Rultl 9(b) by

this Court's Advisorl' Committee on the Rules Governing

$ 225.1 Cases in the United States District Courts rvas that:

"With reference to a successive application assefting a

ruerv ground or one not previously decicled on the merits,

the court in Snrrders noted:

In either case, fqll consideration of the merits of the

new application can be avoiclecl only if there has

been an abuse of the utit {< 'i 'j3 and this the Govern-

ment has the burrlert t,f pleatting. :k :! *

Thus, for exaryrple, if a prisoner rleliberately lvith-

Itokls one of tu'tigrrrun,l.s lbr fecleral collateral relief

at the time of filing his tirst application. * 'k * he

mav be deemetl to have rvaived his right to a hearing

qri'i second appliEation presentint the rvithlield

gt'ound., 373 U. S., at 17-18'

Subdivision tb) [of Rule 9] has incorporated this principle

anrl rerluires that the judge find petitioner's failure to

have asserted the neru g1'ounds in the prior petition to be

inercusablei' Advisory Committee Note to Rule 9(b),

* u. s. C., p. 273 (emfihasis atltlecl).

But Congress tlid not believe that this Court's trallsmitte(l

language, and the Advisory Llomnrittee Note explaining it,

rvent far enough in protecting a state prisoner's right to gain

habeas relief. In its Report on proposetl Rule 9(b), the

House Judiciary Conrmittee stated that, in its view, "the 'not

excusable' Ianguage Iof the proposed Rule] created a nerv and

untleflned standard thttt 11uL'e a judyle too bt'otttl a tLiscretion to

disrliiss a second ot' slcce,ssiue peti.tir-tn." H. Rep. No.

94-1.171, srr2rc, al p. 5 (emphasis arlded). The Judiei4ry

Cpmmittee thus recommencled that the w'ords, "is not excus-

able," be replaced b1'the rvords, "constitutetl an abuse ot'the

\\1jt.\. Id., at 5, 8. This change, the Committee believed,

rvould bring Rule 9(b) "into conformity rvith existing larv."_

1d., at 5. It rvas in the Jucliciarl' Committee's revised/

form-employing the "abusive" stanclarcl for clismissal-that I

Rule 9(b) became latr'. \

II

It is plain that a proper consttuction of Rule 9(b) must be

consistent rvith its legislative history. This necessitt'il1' en'

tails an accurate interprctation of the Srrtrdar,s stanrlarrl, on

rvhich thc Ilule is basetl. It also rctlttires cotrsitlerlliotr of

the explanalor."- language of the Advisorl' Conrniittee, :rnd

Congtess' subsequent strengthening amenilment to the text,

of th"e Rule. Bui tne pluraliiy. entirell' rnisreacling Sutrcletsl]

embraces an interpretation of the Rule 9(b) standard that is I

manifestlf incou'ect, ancl patentlf inconsistent uith the Ad- |

visory Committee's exposition and Congress' expressed

I

expectations. ---l

The relevant language from Scirdels, quoted by the plural-

ity, ante, at 12, is as follorvs:

"[I]f a prisoner cl-ellbgIalg-ly rvithholds one of two

grounds ior reae.aiEl]lIE-uirelief at the tiile of filing

his first application, in the hope of being gtanted trvo

hearings rather than one or for some other such reason,

he may be tleemed to have rvaivecl his right to a hearing

oB a second application plesenting the withheld gqou4-cl.

The same may be true if, as in l1'orrg Doo, the prisoner

deliberatel.v abandons one of his grouncls at the first

hearing. Nothing in the traditions of habeas corpus.lg

quires the fetleral coulls to tolerate neetlless piecemeal

---ii[[ation, or to enLertain collateral proceetlings whose

only purpose is to vex, harass, or delay." 373 U. S. 1,

18.

From this language the plurality conclucles, "Thus a prisoner

rvho decicles to proceed only rvith his exhausteil claims and

deiiberately sets aside his unexhausted claims ttls -d!S-qts-s-al

o*l;glSgquent fecleral petitions." Ante, at 13.

The plurality's conclusion simply distorts the meaning of

the quoled language. Sarrders rvas plainly concerned with "a

prisoner dLljLqrSlglu withholdtingl one of two grounds" for

relief "in the hope of being glanted tu'o hearings rather than

one or for some-other,such reason.'l Sartders also notes that

"6i*r mlght bE lnibrrecl rvhere "the prisoner tleliberatelu

abundons one of his grouncls at the first heat'ing." Finally,

Snrrrlers states that dismissal is appropriate either rvhen the

court is facetl rvith "neetlless piecemeal litigation" or rvith

"collateral proceedings tt'ltose ottlry pttt"pose is to t'e'r, ltct'n.ss,

or delay." Thus Scrrrrlels matle it crystal clear that dismissal

flrrr "abuse of the rrrit" is rrrrlrl appropliate s'hen a pt'isotter

lvas free to include all of his claims in his first petition, but

ktrott'ingly and deiiDertrtely chose not to do so in order to get

more than "<lne bite at the apple." The plurality's interpre-

tation obviously rvould allorv dismissal in a much broader

class of cases than Sanrlers permits,

This Court is free, of course, to overrule Snrrders. But'

even that course u'oulcl not support the plurality's conclusion.

For Congrless incotltoratetl the "judge-made" .Soltiers princi'

ple into positive larv u'hen it enacted Ilule 9(b). That princi-

ple, as explained b."- the Advisory Conrmittee's Note, ot leasl

50 Lw ,1.280 Thc lJnited Stares LAW WEEK 3-2-82

"requires that the thabe4sl igllge firrrl petitioner,s failure rohave ass.er-ted_ttre nffi?1iTn the p.i,o-p.iirion to be iri-e.r'ez.so61e.'\ Indeerl, Congress u,ent

'be1,oncl -ih"

Adui.o.,

Committee's- langrage. believing rt

"t't-i,u'

;;il;;l;';

standard made the dismissal of.su-ccessive puiition. too easy.Congress instead requirecl the habeas'.,,,i"t to find asuccessive. pg i-EgheJ&L.,abusive" before the drasticremed]' ol rlrsmissal coukl be emlllol.edo That is horv Con-gress understood the Sorrtiers principle,"ancl ihe plurality issimply

1ot.fre9 to ignore that'unde;stanaing,-Uecause it isnow embeddecl in the statutory language of frule 9(b).

q.uent incorporation of the higher, ,,abusive,, standard intothe.Rule. The plurality,s conciusion, in ;;;;;, has no sup_

111| yllTl:r from any of these sources. Nor, of course,

ooes tt have the support of a majority of the Court.*

*,rusrlcE WHITE rejects the plurality's conclusion in parl III-C, ante,

see p. l, posl, as does Justtce Bl,rcx.rtux, see pp. g_9, poo-t. JusrIcE

Sruvr:Ns does not reach this issue.

.

rAt.trial, the prosecutor questioned the eyewitness conceraing ,.difficul-

ties" that her sistcr had encountered s.hile riating the respondt,nt. ln re-

sponse to an objection to the materialitl.of the inquin,, the prosecutor es_plainerl' in the presence of the jury, that "r wouitr ttrint< tne defenrlant,s

!'iolent neture \r'ould be material to this case in the light ofwhat the victim

has testified to." .{pp. l?. The trial court excuserlihe;ury to determine

the admissibility of the evidence: it rule<l that the collateral inquiry rvas"too far removed to be material antl relevant.,' App. 22. Aftei the jury

had returned. the court instructed it to tlisregard the p.osecuio"ls

remarks.

.

Ilespondent objected to the prosecutor,s statement on direct appeal.

After reciting the challenged events, the Tennessee Court of Criminai ep-

peals recognizetl that .,State,s counsel macle.orn. .urrrka in the presence

of the jury that.u'ere overll. zealous in support of this incompetent tine ofproof, and in a different case coulcl constitute prejudicial error.,, Lr,rrdy v.Slale,.l2lS.lV.2rl J9l.i9J(197.1). Thecounmled,horrerer,ttrat,,initrEl

context of the undisputed facts of this case rve hold any error io i,".." U"., Ihermless beyond a reasonable rloubt." /bid. '- - ---"-]

Jusrlce Wgnu. concurring in paft and clissenting in part.

I agree with most of Jusucr BRrxteN,s opinion; but likeJusricn BLACKMUN, I would not require , .mi.*.,i,, petition

to be dismissed in its entirety, u,ith leave to resubmit the ex-hausted claims. The triaj judge cannot rule on the unex_

hausted issues ancl shoukl cliimiss them. nuf f,. shoulcl rule

on the exhausted claims unless they are intertwined rvith

those he must dismiss or unless the habeas putiiioner prefers

to have his entire petition dismissecl. ln

"ny

.rlntl'rh[judge rules on those issues that are ripe

""J

.ii.ri.r", ti"r[

that are not, I iyoulri not ta.x the petitioner wil;il; ;'Iiiwrit if he returns with the latteri claims afler seeking staLe

rt'licf.

Jusrrcr SrBveNs, dissenting.

. I*,.,9".,u raises important questions about the authority oftecteraljudges. In ml.opinion the districtjudge properly ex_

ercised his statutory duty to consider the meriis of the claims

advanced by respondent that previously had been rejected bythe Tennessee courts. The district judge e.xceeded, how_

ever, what I regard as proper restraints dn the scope of col-

lateral reyiew of state court juclgments. Ironicalll,, instead

ofcorrecting his error, the Cout toclay fashions a new rule oflaw that _wili merely clelay the final iisposition of this case

and,, as Justlcs Btecxuux demonstrates, impose unnec-

es.sary burdens on both state ancl federal iuclees...\n

adequate e.xplanation of m1, disappr.li.ri br ilr. Court,s

adventure in unnecessary larvmaking'requires some refer_

ence to the facts of this case and to my-conception of theproper role of the writ of habeas corpus in the a<.rministration

of justice in the United States.

I

Respondent was convictecl in state court of rape and acrime against nature. The testimony of the victim u,as

cortoborated by another eyewitness rvho was present duringthe entire.^sadistic episocle. The eviclence of guitt is not

tf.rA.mfn

emouonal, controvefted. adversaiy proceedings, trial errororyL.I".0

9f those.enors-a iemark Uy tfrelrosecu-

tor' and a limitation on defense counsel's crois-e.xamination

\ar,

J

Ii

{

I-'l

/

./

Ia

i

i

I

I

I

{

t.i

I

:rtr

I

'l

:I

U

III

The_plurality,s attempt to apply its inlerpretation of Sand-ers only reinforces my concluiibn that the pluralitl. has mis_read thaL caser The .pluralit.v hypothesizes a prisoner whopresents a "mi.xed" habeas petition that is dismissecr without

any examination of its claims on the nretits, antl w,ho, alterhis exhausterl clainrs ar.e rejecterl, pr".ent, a second petition

containingthe previousll, unexhausied claims. The piurality

!h3n 9Or.1t9..the position of such a p.isoner:-ruith that of the"abusive' habeas petitioner cliscusierl in the Soride,* p".-sage.. But in my vierv, the position of the plurality,s hffi-thetical pdsoner is obviousl_r. ver1, Aiffer:ent.'' If the habeascourt refuses to entertain a ,,mixerl,' petition_as it mustundeL t!e. oluralit.v's view_then the prisoner,s ,,abanclon-

ment" of his unexhausted claims cannot in any meaningful

sense be termed ,,deliberate,"

as that term was used in Snild-ers. There can be no .,abandonment,'

rvhen the prisoner is

rtot pen_nitted to pt'oceed with his unexhaustecl ciaims. If heis t9 galn "speed."- federal relief on his claimii_to which he isentitled. as the Court recognizes u.ith its citation to gra.a-ei-,

ante, at ll-I2-then the prisoner lrrrsl proceed orrly with his

exhausted claims. Thus the prisoner i,-r .rch a case cannot

be said to possess a .,purpose to vex, harass, or clelay,,, nor

any "hope of being granted two hearings rather than one.,,

.. Moreover, the plurality's suggested ireatment of its hypo-

thetical prisoner flatll.contrariicis the nute giUl standarci asexplained by the Aclvisory Committe e, and, a fofiion contra_dicts that standarcl as strengthened anci extenclecl by Con-gres:. After the prisoner's first, ,.mixed,' petition has been

mandatorily dismissed rvithout an.r- scrutiny, after hls ex-

hausted claims have been rejectecl, and afterie has then pre-

Sgnted.

his previously unexhauste<l clairns in a second peti-tion, there is simply no u.a.v in rvhich a habeas court coulil

"find petitioner's failure to have assertecl the new grounds inthe prior petition Lobe inetcusable." On the.ont."ry, peti_

tioner's failure to have assertecl the ,.nerv,i, prevlousty'unex_

hausted claims in the prior petition couta Jnty be founcl to

have been

;e.qtrired bu the hibeas cotLrt iti:selj,'as a condition

for its considerat.ion of the e.xhaustetl claims. If the plurali-

t"v's interpretation of Rule 9tb) cannot satisfl, the Advisory

Committee's ,,inexcusable" stel(lar(l. then ii"fatts even fur-th,er sho.rt of the higher, ,,fuusive" .tan,irr.cl eventually

adoptecl by Congr.ess.

IV

I conclude that tvhen a prisoner's original, ,,mi.retl,,habeas

petition is disnrissed *'ithout an;' exarnination of its craims onthe mer.its, anrl u.hen the prisoner. 1"t",. b,ing.-a seconcl peti_

tion. based on the previousll, une.rhausterl ?t,ri*, that haclearlier been refuserl a hearing, then the ,or",li. of tlismissal

for "abuse of the rvrit" canuui be en-rplo1.",i against that sec-

ond petition, absent unusual factual clrcrmstin.es truly sug_

gesting abuse. This conclusion is to my mind ines."p"Uiy

compelled not only by S-arrders, but also by the Advisory

Committee explanation of the Rule, and by irrngress, subse-

f

:t-2,l2..--_- 'flrc llnitotl .Starcs LA$i/ WEIiK 50 LW 4,281

A

of the victim'-were recognized by the Tennessee Court of

C ri mi n a I A p p e a I s, b t{-hgl,l lS-b€--baglqle sl ia- !!e--c 9 p! e 1!.,.o-1

the entire case. - Because the state appellate court consid-.::'-

&l7_dftjected these two etrors as a basis for setting aside

his conviction, respondent has exhausted his state remedies

with respect to lhese two claims.

In his application in federal court for a writ of habeas cor-

pus, respondent alleged that these trial erors violated his

constitutional rights to confront the rvitnesses against him

and to obtain a fair trial. In his petition, respondent also al-

leged thaL lhe prosecutor had impermissibly commented on

his failure to testify' and that the triai judge had improperly

instructed the jury lhat "every u'itness is presumed to swear

the truth."' Because these trvo additional claims had not

been presented to the Tennessee Court of Criminal-Appeals,

the federal district judge concluded that he could "not con-

sider them in the constitutional framer,r'ork." App. 88. He

adrled. however, that "in assessing the atmosphere of the

cause taken as a whole these ilems 4gy-bg 1'-efetled !o

eollaterally."'

Jnlonsiiiering the significance of respondent's two ex-

hausted claims, the District Court thus evaluated them in the

conte.\t of the entire trial record. That is precisely what the

Tennessee Court of Criminal Appeals did in arriving at ils

conclusion that these claims, identified as el1'or' rvere not suf-

ficiently prejudicial to justify reversing the convictiort and or-

<lering a retrial.^ In 991;1d91ng lvhet!91 lhe etror in these

I Defense counsel cross-e-raminetl the victim concerning her prior sexual

activitl'. W'tren the victim responrled that she coukl not remember certain