Houston Independent School District v. U.S. Memo in Opposition to Motion for Stay

Public Court Documents

February 18, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Houston Independent School District v. U.S. Memo in Opposition to Motion for Stay, 1971. 44e99079-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0bfb7dd7-7764-4882-8f78-cb3405f3d5cf/houston-independent-school-district-v-us-memo-in-opposition-to-motion-for-stay. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

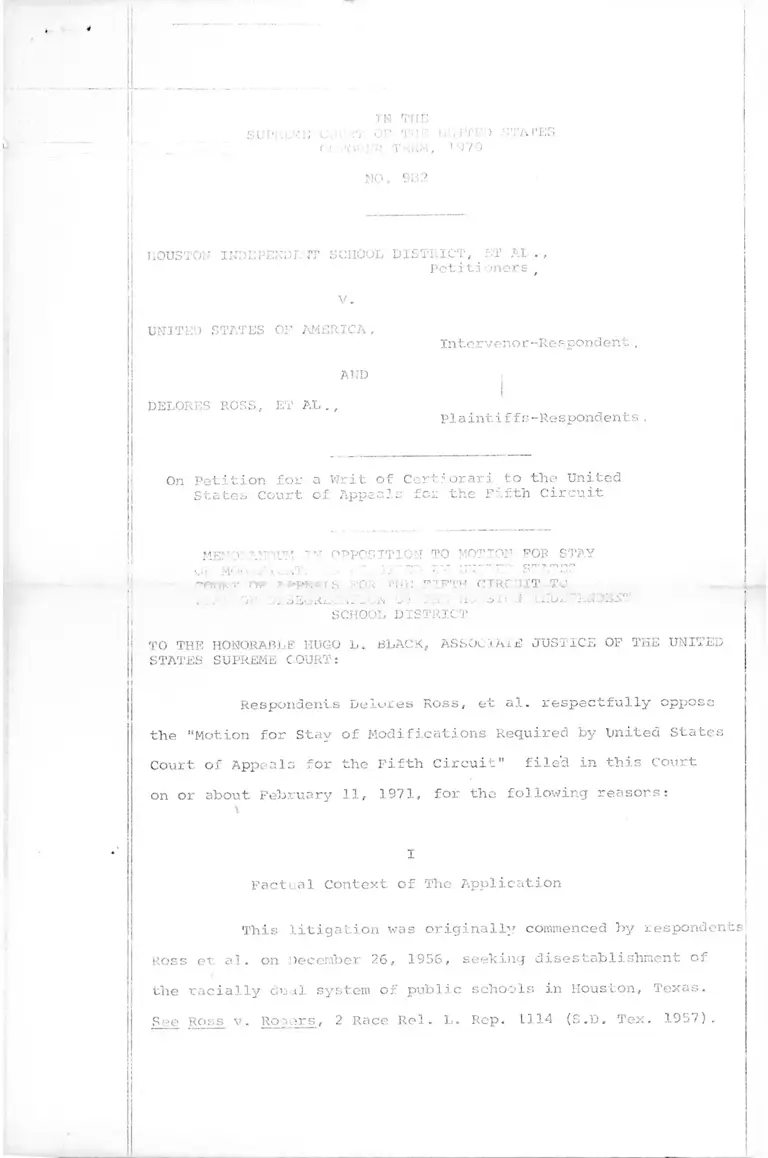

IN THE

SUPREEE COUNT OF THE UNITED STAPES

OCTOBER TERM, 1970

NO, 982

HOUSTON INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT, F;T AL . ,Petitioners ,

V.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ,

AND

Intcrvenor-Respondent,

DELORES ROSS, ET A.L . , Pi a int i f f s -Respondent s

On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

MTv ••'V . v.t OPPOSITION TO MOTION FOR STAY

Or ’.} v... i i . • > * j • *. 1 U"n •. ». ■ . •

-OUK.-P OF T np'.: :S FOR n-V. FIFTH CIRCUIT TO

. .. - -i>J 1 Jx-- i O i ' -V ••

SCHOOL DISTRICT

i TO THE HONORABLE HUGO L. BLACK, ASSOCIATE JUSTICE OF THE UNITED

STATES SUPREME COURT:

Respondents Deloies Ross, et al. respectfully oppose

the "Motion for Stay of Modifications Required by United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit" filed in this Court

on or about February 11, 1971, for the following reasons:

\

I

Factual Context of The Application

i

This litigation was originally commenced by respondents;

i

Ross et al. on December 26, 1956, seeking disestablishment of

the racially dual system of public schools in Houston, Texas.

Pee Ross v. Rogers, 2 Race Rel. L. Rep. LI14 (S.D. Tex. 1957).

■

Throughout the period since initiation of the litigation, there

have been numerous proceedings toward the objective of creating

a constitutional unitary school system. (This Court has pre

viously denied a similar application to stay desegregation of

the Houston schools. Houston Independent School Dist. v. Ross,

364 U.S. 803 (I960)). The United States intervened as a

plaintiff for this purpose in July, 1967, pursuant to Section

902 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §20001i-2.

Despite these attempts throughout the lawsuit to

eliminate racially discriminatory practices in the operation

of Houston's public schools, the Court of Appeals found that

as of December 1969 . . .

77% of the Negro students in

the entire system still attended

schools that had student bodies

composed of more than 90% Negros.

Ross v. Eckels, No. 30080 (5t.h Cir., Aug. 25, 1970) (typewritten

slip opinion at pp. 4-5)."*

Following the filing of motions for supplemental

relief in the district court in 1968 and 1969, and after an

evidentiary hearing in July, 1969, the district court applied

the standards announced in this Court's decision in Green v.

County School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1.968) and

held that the district's then operative freedom-of-choice plan

failed to'meet constitutional requirements. Ross v. Eckels,

Civ. No. 10444 (S.D. Tex., July 23, 1969) (oral opinion).

Subsequently, several different proposed plans of desegregation

were submitted to the district court by the parties. On June

1, 1970, the district court approved one of the plans submitted

by the school district; both the private plaintiffs and the

i

* The Court of Appeals' opinion has not yet been reported. A

copy of the typewritten slip opinion is attached to petitioners'

motion as Exhibit "A."

2

UnitecT States appealed to the Fifth Circuit. The appeals

court’s ruling is the subject of petitioner's stay motion.

II

The Order Sought to be Stayed

On August 25, 1970, the Court of Appeals reversed

the district court's decision in part. The Court concluded

that the district judge had erroneously applied the Circuit

Court s standards in an earlier decision [Ellis v. Board of

Public Instruction of Orange County, 423 F.2d 203 (1970)]

to Houston without consideration of the factual distinctions

between the school systems involved:

rne district ^udge adopted the equidistant zoning

plan. The opinion of the district court demonstrates

that this case received learned, thorough detailed con

sideration. The court analyzed the general geographic,

student and teacher racial compositions of the Orange

County, Florida, and the Houston Districts and found

them to bo legally comparable. It adjudicated the plan

as applied m Houston to be fair and impartial in its

resultant operation and that such racial segregation

as did result was inherent in the city's residential

patterns. in light of the other features incorporated

m its order concerning teacher integration, majority

to minority transfer privilege and precise faculty

^n . a 1 1 schools, the district court concluded s he equidistant zoning plan was a permissible

means of achieving the conversion of the Houston Indepen

dent School District from a dual to a unitary system.

APPLICABLE LEGAL STANDARDS

In the Orange County case, supra, we were careful

to emphasize that, under the facts of that case,

a neighborhood assignment system was adequate to

convert the school from a dual to a unitary system.

But m the same sentence we stated that, in the

final analysis, each case had to be judged on al]

facts peculiar to the particular system. This is

but another way of expressing what is implicit in

every school decision and explicit in many in the I

present state of the lav/ in this area -- school cases

are unique. Each school case must turn on its own facts.

Ross v. Eckels, .supra, typewritten slip opinion at pp. 12-13

3

Applying this test, the Court held that there

were "reasonably available other ways" fGreen, supra, 391

U.S. at 441] which would further desegregate the Houston

elementary schools:

We direct that the equidistant plan be used as

a base for elementary school assignment but with

the modifications hereinafter set out. These

modifications which involve contiguous school zones

are well within any reasonable definition of a

neighborhood school system. See Mannings v. Board

of Public Instruction of Hillsborough County, 5 Cir.,

427 F.2d 874.

Id. at 13-14.

However, the Court of Appeals left the door open

for further changes and improvements of the modifications it

suggested so long as they were consistent with the school board's

obligation to act affirmatively to disestablish the dual school

system:

The district court is directed to implement

the foregoing modifications as to the elementary

school, zones or alternatively the court may adopt

any other plan submitted by the school board or

other interested parties, provided, of course, that

such alternate plan achieves at least the same

degree of desegregation as that reached by our

modifications. See Pate v. Dade County School

Board, 5Cir., 1970, ____ F .2d ____ [Nos. 29,038 and

29,179, slip opinion dated August 25, 1970].

AFFIRMED in part, REVERSED in part, REMANDED with directions,

Id. at 14 *

Proceedings Subsequent to the Court

of Appeals 1 Decision

On December 8 , 1970, the Court of Appeals denied the

motion made to that Court by present petitioners to stay its

mandate insofar as the pairing of certain elementary schools was

4

required. See Exhibits "B" and "C" to the "Motion for Stay of

Modifications" filed in this Court. However, despite that action

~ond"despite'the language of the original decision by the Court

of Appeals that " [t]he mandeite in this cause shall issue forth

with; no stay will be granted pending petition for rehearing

or application for writ of certiorari," no order on remand has

ever been entered by the district court. No alternatives to

the pairings which petitioners complain of have been presented

to the district court which achieve at least as much desegre

gation in the Houston public schools. In sum, the school system

is still being operated essentially under the same plan which

the Fifth Circuit held on August 25, 1970, failed to meet the

requirements of the United States Constitution.

IV

Argument

This brief recitation of rhe facts should suffice to

demonstrate that the thrust of petitioners1 Motion is to seek

the sanction of this Court permitting it to continue unconstitut

ional practices of segregation in its ptfblic schools.

Whatever the lack of justification for the failure

of the district court to act pursuant to the mandate of the

Court of Appeals, since last August, that delay has equally been

occasxoned by the school district's refusal to comply with the

plain terms of the Fifth Circuit's decision. The district has

no one to blame but itself, therefore, for the prospect which it

now claims to face of "disruption of the educational process

necessarily entailed in student transfers which occur during

the term."

Alexander v. Holmes County B i. of Educ.. 396 U.S. 19

(1969); Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd .. 396 U.S.

5

290 (1970); Dowell v. Board of Educ. of Oklahoma City, 396 U.S.

269 (1969); and Northeross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis, 397

U.S. 232 (1970), all make clear the constitutional imperative

that schools be desegregated "at once" pending further litigation

concerning remaining contentions of the parties. That these

mandates have thus far been ignored furnishes no reason for count

enancing further evasion of the school district's constitutional

obligations.

Nor does the pendency of school desegregation cases

before this Court alter the constitutional command. Obviously

this Court did not intend to vitiate the rule of Alexander when

it granted review in the cases presently awaiting decision (Swann

v. Char1otte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ. et al). See, e .g ., Swann

v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., No. 281 O.T. 1970 (unre

ported order of full Court, August 25, 1.970, denying requested

stays, pending this Court's decision, of school desegregation

in Charlotte, Winston-Salem, Fort Lauderdale and Miami);

Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ. of Nashville and Davidson

County v. Kelley (unreported order of February 3, 1971 by Mr.

Justice Stewart, denying application for stay, pending certiorari,

of requirement that proceedings in school desegregation case

continue); Watson Chapel School Dist. No. 24 v. United States

(unreported order of February 10, 1971 by Mr. Justice Blackmun,

denying stay pending certiorari of district court order requiring

immediate implementation of desegregation plan).

These denials of stays of course merely continue this

Court's consistent history of refusing to postpone school

l

6

desegregation by issuing stays or declining to vacate such stays

jwlYfZrn "grunted - by~ 1 ower courts. See, c . g •, Lucy v. Adams, 350

U.S. 1 (1955); Houston Independent School Dist. v. Ross, 364

U.S. 803 (1960); Danner v. Holmes, 364 U.S. 939 Race Rel. L.

Rep. 1092 (1961) (refusing to reinstate a stay dissolved by Chief

Judge Tuttle of the Fifth Circuit in Holmes v. Danner, 5 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 1091 (1961)); Boomer v. Beaufort County Bd. of Educ.

(August 30, 1968) (unreported order of Mr. Justice Black, vacat

ing stays granted by the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit).

Finally actions taken by the Court of Appeals in

other school desegregation cases do not support issuance of a

stay in this case. Since the Court of Appeals' decision allows

district court hearings on alternatives to the pairing, which

may be litigated in the district court, this case is not in the

same posture as Allen v. Board of Public Instruction of Broward

County, 5th Cir. No. 3003*;, wherein the Court of Appeals gianted

a stay of a district court order implementing its decision an

nounced August 18, 1970, 432 F.2d 362. And while the Court of

Appeals did issue a press release on October 1 announcing that

it would render no further school desegregation decisions until

this Court rules in the Charlotte and Mobile cases, there is

presently pending before the Fifth Circuit a Motion for Decision

in twelve such cases sub now. Calhoun v. Cook, 5th Cir. No. 2960.J,

30357. Since the press release announcement was made ex parte,

and without any communication whatsoever to counsel in these

cases, and until the Court of Appeals has ruled upon the Motion

for Decision, this case is inappropriate to review the validity

l 7

the

Stray-

Fifth Circuit's

Irrth ±s~ma t:or.

practice especially by way of issuing

WHEREFORE, respondents Delores Ross et al. respect

fully pray that the requested stay order be denied.

^Respectfully suijmi tte

(JLD'ON II. BERRY, ESQ.

711 Main Street, Suite 620

Houston, Texas 77002

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Respondents

Ross, et al.

8

I

CriRTTF'j CATE OF- SERVICE

This is to certify that on this 10th day of February,

197]., I served a copy of the foregoing Memorandum in Opposition

to Motion for Stay of Modifications Required by United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit to Plan of Desegregation

of the Houston Independent School District upon the attorneys

for the petitioners and respondent intervenor, William Key

Wilde, Esq., Bracewell and Patterson, 1808 First City National

Bank Building, Houston, Texas 77002; Ernest II. Cannon,Esq.,

500 Houston First Savings Ruilding. 711 Fannin Street, Houston,

Texas 77002; lion. Jerris Leonard, Assistant Attorney General,

Civil Rights Division, Unit 0H si-ci Lcs rtiucrit of ticc ^

Washington, D.C. 20530; and Hon. Anthony Farris, United States

Attorney, 515 Rusk Avenue, Houston, Texas 77002, by United

States mail, air mail postage prepaid.

\

9

l