Ford v. United States Steel Corporation Reply Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

October 11, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ford v. United States Steel Corporation Reply Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1974. ed0be933-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0c2c98b3-d5c5-4ebd-a032-2e7276e53b7e/ford-v-united-states-steel-corporation-reply-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

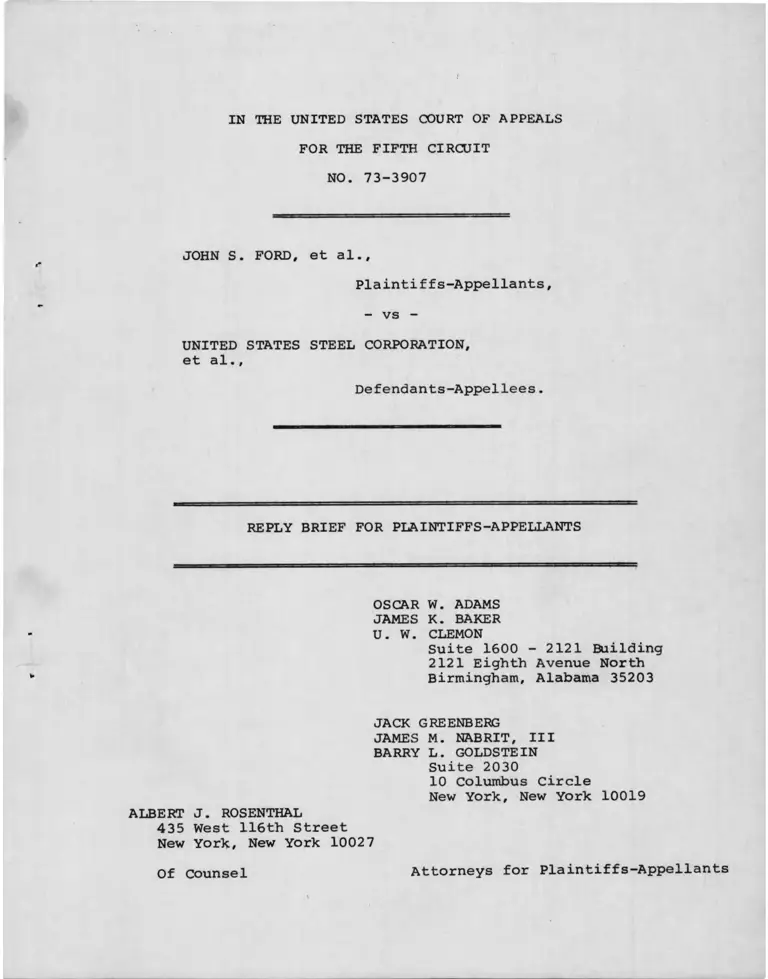

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 73-3907

JOHN S. FORD, et al..

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

- vs -

UNITED STATES STEEL CORPORATION,

et al.,

Defendants-Appellees. * 10

REPLY BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

OSCAR W. ADAMS

JAMES K. BAKER

U. W. CLEMONSuite 1600 - 2121 Building

2121 Eighth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

ALBERT J. ROSENTHAL435 West 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

Suite 203010 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Of Counsel Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

I N D E X

Note on Form of Citations ii

Table of Authorities iii

INTORDUCTION...................................... 1

I. THE DEFENDANTS ENGAGED IN A GENERALPATTERN AND PRACTICE OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION

WHICH RESULTED IN BLACK WORKERS BEING

EXCLUDED FROM HIGHER-PAYING JOBS AND FROM TRAINING OPPORTUNITIES................... 3

(a) Promotion and Training for Trade and

Craft Positions........................ 4

(b) Selection for Supervisory Positions.... 5

(c) Discriminatory Establishment of Seniorityand Promotional Systems in the 1960's... 5

(1) Line of Progression ("Unit" or

"LOP") 308, Ensley Steel Plant... 5

(2) Pratt City Car Shop............. 7

(3) Plate Mill, Fairfield Steel..... 7

(4) The Establishment of Labor Pools.. 8

II. THE DISCRIMINATORY PRACTICES OF THE

DEFENDANTS RESULTED IN SUBSTANTIAL LOST

EARNINGS TO THE AFFECTED CLASS... 10

III. IN LIGHT OF THE PLAINLY UNLAWFUL PRACTICESOF THE DEFENDANTS WHICH RESULTED IN SUB

STANTIAL ECONOMIC HARM TO THE AFFECTED CLASS,

THIS COURT SHOULD REVERSE THE LOWER COURT1S

DENIAL OF BACK PAY............... 15

IV. THE CONSENT DECREES DO NOT PROVIDE ANYBASIS FOR DENYING BACK PAY TO THE AFFECTED

CLASS..................................... 19

V. THIS APPEAL IS PROPERLY BEFORE THIS COURT-- 23

APPENDIX A, X189

APPENDIX B, Tr. Vol. 50, Nov. 30, 1972, pp. 162-165, 239-

239-243.

APPENDIX C, Tr. Vol. 50, Nov. 30, 1972 pp. 23-25,192-199

Page

- l

Note on Form of Citations

The following citations are frequently used in this brief:

"A. II pages of the "Joint Appendix"filed in

this appeal, as numbered therein

"X. II exhibit introduced at trial as

designated therein.

"G Br. Brief filed by the United States in the

appeal consolidated with this appeal.

”U. Br. Brief filed by the defendants-appellee United Steelworkers of America

"c. Br. Brief filed by the defendant-appellee

United States Steel Corporation.

"PI . Br. Brief filed by the plaintiffs-appellants

Ford, et al.

"Tr II Transcript of the trial testimony,

designating the date of the testimony,

the volume of the transcript and the

page number (s).

11

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

PAGE

Cases

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Corporation, 39L.Ed.2d147 (1974).................................... 22

Arkansas Education Assn. v. Bd. of Education of

Portland, 446 F.2d 763 (8th Cir. 1971)........ 28

Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refining Corporation,

495 F. 2d 437 (5th Cir. 1974).................. 3,12,16,22

Bell v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 226 (1964)............... 4

Bush v. Lone Star Steel Corporation, 373 F.Supp.

526 (E.D. Tex. 1974)......................... 19

Carey v. Greyhound Bus Co., Inc., No. 73-3133

(5th Cir. Sept. 26, 1974).................... 16

Duhon v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company, 494

F .2d 817 (5th Cir. 1974).................... 16

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Company, 495

F.2d 398 (5th Cir. 1974).................... 16

Gonzales v. Cassidy, 474 F.2d 67 (5th Cir. 1973).... 25

Griggs v. Duke Power Company, 401 U.S. 424

(1971)...................................... 3, 18

Griggs v. Duke Power Company, 420 F.2d

112 5 (4th Cir. 1970)........................ 18

In the Matter of Bethlehem Steel Corporation,

Decision of the Secretary of Labor,

Docket No. 102-68, January 15, 1973

EPD K 5128................................... 19

Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 28 (5thCir. 1968).................................. 28

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company, 491

F. 2d 1364 (5th Cir. 1974)................... 3,15-17

Moody v. Albemarle Paper Company, 471 F.2d

134 (4th Cir. 1973)......................... 18

- i n

Statutes and Other Authorities

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

Rule 23....................................... 26

Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure

Rule 4 (a)..................................... 24

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

(as amended 1972) 42 U.S.C. §§2000e et seq.... passim

Wright & Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure...... 26,18

29 U.S. C. §§151 et seq.............................. 18

42 U.S.C. §1981...................................... 17

Page

v

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES [Cnnl- ’H]

Page

Pettway v. American Cast Iron

494 F.2d 211 (5th Cir. Pipe Company, 1974).......

Rowe v. General Motors Corporation, 457 F.2d 348 (5th Cir. 1972)............

Sprogis v. United Air Lines, 444 F.2d 1194

(7th Cir. 1971) cert, denied 404 U <5 991 (1971).... 7777.7..... ........

Sprogis v. United Air Lines, 56 F.R d 420 (N.D. 111. 1972)............. '.....

Taylor v. Armco Steel Corporation, 8 EPD H9550 (S.D. Tex. 1973).......................

Taylor v. Armco Steel Corporation, 429 F.2d498 (5th Cir. 1970)............. ).....

United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corporation446 F.2d 652 (2nd Cir. 1971)........ ' ̂

United States v. Georgia Power Company, 471

F • 2d 906 (5th Cir. 1973)................

United States v. Hayes International Corp. 456 F.2d 112, 121 (5th Cir. 1972)................. *

United States v. H.K. Porter Corporation, 296F.Supp. 40 (N.D. Ala. 1968)...............

United States v. H.K. Porter Corporation 491 f 2d 1105 (5th Cir. 1974)...................

Williamson v. Bethlehem Steel Corporation, 468 F•2d 1202 (2nd Cir. 1972) cert.denied 411 U.S. 973 (1973)......7777.77.....

Whitfield v. United Steelworkers, 267 F.2d 546 (5th Cir. 1959)...............

3, 15-18, 20-22

5

26

26

19

18, 19

19

18

25

18

19

25-26

17, 19

IV

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 73-3907

JOHN S. FORD, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

- vs -

UNITED STATES STEEL CORPORATION,

et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

REPLY BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

I N T R O D U C T I O N

The defendants—appellees, United States Steel Corporation

("U.S. Steel" or the "Company") and the United Steelworkers of

America ("Steelworkers" or the "Union"), rely in their briefs on

several events which took place since the lower court entered its

opinion: (1 ) the consent decrees between the government, nine

major steel companies and the Steelworkers, and (2) the effect of

1/ On April 12, 1974, the Department of Justice, Department

of Labor and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission filed a

Complaint in the Northern District of Alabama against nine major

steel companies, including U.S. Steel, and the Steelworkers,

the remedial order of the district court. Neither the consent

decrees, see section XV, nor the purported effect of the remedial

order, see section II, provide any basis for denying back pay to

the affected class.

The Company questions in its brief the authority of the

plaintiffs to represent the affected class. Even though this issue

is not properly before the Court, since U.S. Steel did not appeal

from the lower court's conclusion of law that the plaintiffs were

appropriate class representatives, the plaintiffs—appellants briefly

respond to this argument, Section V.

Finally, the plaintiffs-appellants respond to the defendants'

assertions concerning the scope of their discriminatory practices,

Section I, the economic effect of those practices, Section II, and

the application of this Circuit's standard for the exercise of

district courts' discretion to deny back pay, section III.

1/ [Cont'd .]alleging, inter alia, unlawful racial discrimination in the terms

and conditions of employment. United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum

Industries, Inc., et al., Civil Action No. 74-P-339. On that same

day the parties presented two consent decrees which purported to

resolve all issues "between the plaintiffs [i.e., the Government]

and the defendants". U.S. Steel's Appendix, p. 4, para. C. The

district court also signed the consent decrees on the day they were

presented, April 12, 1974.

Twenty—nine black steelworkers sought and were granted the

right to intervene for the limited purpose of challenging certain allegedly illegal provisions. (Several female steelworkers, who

challenged the lawfulness of the consent decrees, were allowed to

intervene as well). The intervenors have appealed the district

court's refusal to vacate the consent decrees; the appeal is

presently pending with this Court, No. 74—3056.

2

THE DEFENDANTS ENGAGED IN A GENERAL PATTERN AND

PRACTICE OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION WHICH RESULTED

IN BLACK WORKERS BEING EXCLUDED FROM HIGHER-PAYING

JOBS AND FROM TRAINING OPPORTUNITIES______________

The district court explicitly found that the defendants

engaged in unlawful practices which perpetuated the discriminatory

effects of the previous system of racial segregation of job oppor

tunities. [A. 159-61; see Pi. Br. 14-21] These unlawful practices

coupled with the clear showing of lost earning suffered by Blacks

establishes a clear requirement for back pay. Pi. Br. 31-34,

section IV, infra.

The thrust of Title VII is directed to the consequences,

in this case economic loss, of discriminatory practices, not to the

motivation or intent of the employers. Cf. Griggs v. Duke Power

Company, 401 U.S. 424, 432 (1971). However, the defendants, in

their brief, have argued that the practices "only" continued the

effects of past discrimination and continually congratulated them

selves on their "good faith" attempts to terminate discrimination.

Since the defendants rely on their supposed good faith in a number

of their arguments, the plaintiffs-appellants, in order to afford

some balance to the evidence of discrimination, cite several in

stances of blatant discrimination which resulted in lost earnings

1/to black workers. 2

I.

2 / The Union recognized the clear law of this Circuit that "good

faith" efforts by defendants is not a valid defense to claims for

back pay. Union Br. 21. Johnson v, Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company,

491 F .2d 1364, 1376 (5th Cir. 1974); Pettway v. American Cast Iron

Pipe Company, 494 F.2d 211, 253 (5th Cir. 1974); Baxter v. Savannah

Sugar Refining Corporation, 495 F.2d 437, 443 (5th Cir. 1974).

3

The selection for apprentices, craft jobs, and supervisors,a

traditional "whites only" preserves, is/good indication of the con

tinued resistance to equal employment by the Company.

(a) Promotion and Training for Trade and Craft Positions

The continued limitation on the promotion of black

steelworkers to trade and craft positions or to training programs

3/after 1963 reveals the intransigence of U.S. Steel. Blacks, his

torically had been almost totally excluded from the trade and craft

4/positions, which include a larger number of the better-paying jobs.

The Company changed its policy from total exclusion to nothing more

than tokenism: during the pay period ending February 6 , 1972 there

5/were 1,392 whites and 20, or only 1.4% blacks working in the 23

crafts at Fairfield Works. [X106, para. 12]

From July, 1964 through June 3, 1970, 154 employees became

journeymen; only 8 of these employees were Black. [Id. para. 8]

During this period 27 whites and 1 Black completed the Company's

6/apprentice program. para. 9] * * * *

3/ Judge Pointer offered some praise for United States SteelCorporation's limited revision of its segregationist practices in

1963. [A. 160] For a contrary appraisal, see Bell v. Maryland,

378 U.S. 226, 270 n.3 (concurring opinion) (1964)

4/ Prior to October 1, 1963, journeymen classifications were re

stricted to whites by formal Company policy, except for one unit of

black pipefitters and one unit of black painters. [X106, para. 2]

5/ Of the 20 black craftsmen, 12 were working in the traditional

all-black pipefitter and painter units. See n. 4 , supra. Also the four black Mobile Equipment Mechanics had their status changed

to craftsman as a result of an agreement which defined their job

as a craft job. [X106, paras. 1, 13]

6/ The Company had complete discretion, unfettered by anycollective bargaining contract, to select apprentices from October

1, 1963 to August 1, 1968. During this period 48 whites were

selected and 5 Blacks. [X106, para. 18]

4

(b) Selection for Supervisory Positions

As of November, 1971, there were 1,047 managerial

employees at Fairfield Works; 928 of these supervisors were serv

ing at the general foreman and lower supervisory positions. [X36]

Only 16 or 1.7% of the 928 supervisors at the general foreman level

or below were Black. [X36] In fact prior to July 1, 1966 not one

Black had ever worked in a supervisory position. [X36]

\

The Company regularly promotes employees from their hourly

Vworkforce to supervisory positions. Since the effective date of

Title vil, July 1, 1965, and December 31, 1970, 295 employees were

promoted to supervisory positions; only 16 or 5.6% of the promotions

were afforded to Blacks, who comprise approximately 27% of the

workforce. [X36]

(c) Discriminatory Establishment of Seniority and

Promotional Systems in the 1960's___________

The defendants under the guise of integrating jobs at

Fairfield Works established practices which were blatantly dis

criminatory.

(1) Line of Progression ("Unit" or "LOP")

308, Ensley Steel Plant

Prior to September 22, 1963, jobs in LOP 308 were

staffed solely by white employees, and the jobs in LOP 310 solely

by black employees. [X108, para. 2] Effective September 22, 1963# 7

7 / The selection procecure for supervisors is within the dis

cretion of management. There are no written guidelines or bid pro

cedure; the selection is left to the determination, and accordingly to the subjective judgment, of management personnel. [Tr. Vol. 2,

June 20, 1972, at 133-34, 150] See Rowe v. General Motors

Corporation, 457 F.2d 348 (5th Cir. 1972)

5

the two lines were redesignated 308 and 308A respectively. However,

the two lines were not merged; rather the employees in LOP 308

(who were white) were able to "bump" employees in LOP 308A (who

were Black) during a reduction-in-force on the basis of their LOP

308 seniority. But Blacks in LOP 308A were only able to promote

into a vacancy in LOP 308 after all the white incumbents in that

LOP, including those with recall rights, had the option to move

into the vacancy, even if black employees had greater seniority in

LOP 308A than the white employee had seniority in LOP 308. If a

black employee was finally able to promote into LOP 308 he did not

carry with him his seniority from LOP 308A; his seniority in LOP

308, for purposes of promotion and regression within that line was

limited to the date he first was permanently assigned to a job in

8/LOP 308. [X108, paras. 4-7]

The 1963 Agreement also provided that LOP 308A would have a

preference over all other employees or hirees for vacancies in LOP

308. [.Id. para. 8] Despite this preference at least 8 white em

ployees were either directly hired or transferred into LOP 308 be

fore any black employee was able to promote into LOP 308. None of

8/ A similarly egregious situation occurred in LOP 222, Ensley

Steel Plant. The effect of this particular merger was, on the one hand, to allow whites who had less seniority in the particular

LOP to "bump" Blacks from the formerly all-black switchmen

positions, and on the other hand to prevent Blacks who were formally qualified as engineers from promoting to engineering

vacancies which were filled by whites who were junior to the

qualified black engineers. Tr. Vol. 51, December 1, 1972 at

149-67, 179-85, 197-221, 218-21; Tr. Vol. 28, August 31, 1972,

at 6 6-6 8, 81-85.

6

these white employees worked in LOP 308A before they

2/entered LOP 308. [Id., para. 9]

(2) Pratt City Car Shop.

In 1964 the Steelworkers and U.S. Steel abrogated a

1963 agreement which would have afforded blacks in the Car Shop

the opportunity to move to their rightful place within a year by

permitting them to "carry" their seniority in the all-black Car

Shop LOP to the all-white Car Shop LOP. Under the 1964 Agreement

10/

there was no carry-over seniority. [See Pi. Br. 21-24; X105,

paras. 6-1 0]

(3) Plate Mill, Fairfield Steel.

The union placed a white grievanceman on the stand,

Robert Jones, who testified that in 1962-63 he canvassed black

hookers in the plate mill department as to whether they wanted their

hooker jobs merged with crane operator positions or retained in the

9/ X191 is a general approximation of the economic harm sufferedby Blacks in LOP 308A. The white employees who moved into LOP 308

averaged gross earnings of $10,552.67 in 1970 while the black employees who were passed over in LOP 308A averaged $9,512.30 for a difference of $1,043.37 per man for the year. See Tr. Vol.

54, December 6 , 1972 at 103-06 for a discussion of some of the

limitations of the exhibit.

10/ The sequence of events concerning LOP 107 of Ensley Steel plant was similar to the abrogation of the agreement in the

car shop.

In March, 1963 LOP 107 (which was all-white) was merged

with LOP 108 (which was all-black) to form one continuous LOP;

this merger would have allowed Blacks an opportunity to reach their

rightful place. [X133; Tr. Vol. 28, August 29, 1972, at 107-110]

Six months after the merger the LOPs were re-separated. [Id.*]

7

i i_ ythe all-black LOPs. [Tr. Vol. 24, August 25, 1972, at 50-59]

Mr. Jones stated that a majority of Blacks did not want their

hooker jobs merged with the crane job. [Id.] In fact, the Blacks

in the plate mill, just like Blacks throughout Fairfield Works,

were not consulted during the period when the defendants made some

changes in the segregationist employment structure; over thirty

black workers, a majority of those working as hookers at the time#

testified that Mr. Jones had never asked them about merging the

12/hooker job with the crane operator job.

There are numerous additional examples of discriminatory

practices being purposely incorporated into the changes in the system

of segregated job structure in the 1960s. See PI. Br. 17-20.

(4) The Establishment of the Labor Pool.

U.S. Steel argues that appellants' brief gives a mis

taken impression concerning the creation of the labor pools; the

11/ It was during that period that the Company and the Union

agreed to "merge" some lines of promotion. Prior to this time

all the jobs at Fairfield Works were segregated. [A.159-61]

There were three hooker jobs in the plate mill department.

A hooker in essence works as an assistant or helper for a craneman.

Hooker jobs were staffed by Blacks, and craneman jobs by whites.

The "merging"of the jobs, hooker and craneman, would have allowed

Blacks to transfer to the craneman job without the loss of their

seniority as a hooker.

12/ The following is a list of these witnesses .and the Volume

and page on which their testimony begins: Vol. 53, December 5, 1972 -

Ard. 6 6, Richardson, 73, Thomas, 80, Peavy, 84, Jordan, 89, Hunter, 106, Dorsey; 116; Rambo, 119, Carter, 130, Suttle, 137, Davis, 144

O'Neal, 163, Jordan, 166, Watkins, 168, Thomas, 182, Lockett, 214,

Lavender, 223, Harper, 228, Mims, 234, Gaines, 240, Gilmore, 245,

Steele, 253, Birchfield, 255, Gadsden, 263, Henderson, 289, Wyatt,

315, Martin, 318, Skipworth, 334; Vol. 54 — Hardy 15; Dees, 44, Austin, 49.

8

Company further argues that the establishment of the pools did not

have any discriminatory effect on Blacks and that the government

13/agreed that the pools were a "good thing". [c. Br. 47-8]

The position of the government is fully set forth in their

brief; the brief clearly establishes the discriminatory effect of

the method in which the pools were established in Fairfield Works;

14/a method practically unique in the steel industry.

The adoption of the pool concept was industrywide and, as the district court indicated, the

Government has not challenged the concept itself or

the reason behind its adoption (App. 153, fn. 11).

What we do point out, however, is that because blacks at the Fairfield Works were confined to the

lowest Job Class rated jobs, it was primarily black-

only jobs which were placed in the pool. Further

more, the pool jobs were severed from the portions

of the lines of promotion which were above the Job

Class 4 or pool level. This was a feature of the

Fairfield pools which was not followed industry

wide, but in fact represented a violation of the

industry-wide Basic Steel P&M agreements which specifically provided for the continuation of the

lines unsevered (App. 113-114).— '

10/ The 1964, 1968 and 1971, industry

wide Basic Steel P&M Agreements each spe

cifically provided (in Subsections 13-L-l and 13-L-3) that employees who were on jobs which were placed in the pool were to re

tain their seniority rights to progression into the jobs in the line of promotion above the pool to which their jobs were

to remain in part, irrespective of whether they had "regularly worked" in jobs above

the pool prior to the creation of the pool

(App. 113-114; Ex. 45).

13/ The position of the United States is grossly misrepresented by

the Company's taking a statement of a government attorney out of context

14/ The plaintiffs take the liberty of quoting extensively from

the government's brief because the brief of the government may not

be before the Court if the government withdraws its appeal.See C. Br. 49.

9

As a result, the blacks in the pool jobs retained

no promotional rights above the pool and thus, for

many of them, the mergers of the following year

meant nothing because they were in jobs which no longer were part of the remnant of the all-black

line which was merged with a white line (App. 89-93).

The magnitude of this latter advese effect is

best demonstrated by statistics. Of the 1,156

jobs within the Works which prior to 1963 were limited exclusively to whites, only 1 0, or less than

one percent, were placed in the pools. On the other

hand, of the 751 jobs to which blacks had access

prior to 1963, 385, or better than 51%, were placed

in the pools (Exs. 7-15). The effect of this was

still very evident as of the time of trial. The

following set forth for all P&M employees at Fair-

field Works as of February 6 , 1971, the total

numbers who: (1 ) had established seniority in a

line of promotion above the pool; (2 ) had only

seniority in the pool; and, (3) the percentage who

had only pool seniority (Ex. 39, p. 635):

LOP Sen. Pool Sen. % Pool Sen. Only

White 5,247 647 11.0

Black 1,571 1,495 48.0

The percentage of white P&M employees who only

had pool seniority (1 1%) was as high as it was only

because since 1963, pool jobs had served as the

initial jobs for nearly all new P&M employees, regardless of race. Thus, as of 2/6/71, the

median plant seniority date of the 647 white pool

employees was only 2/18/69, or 2 years, while the

median plant seniority date of black pool employees

was 6/29/50, or more than 20 years (Ex. 107 1(5).

G. Br. 13-15.

II.

THE DISCRIMINATORY PRACTICES OF THE DEFENDANTS

RESULTED IN SUBSTANTIAL LOST EARNINGS TO THE

_______________AFFECTED CLASS_______________

It is clear, as the district court found, that the defendants

engaged in discriminatory practices which resulted in Blacks being

assigned to and unlawfully restricted to lower-paying jobs and

10

conversely to their being excluded or limited in their opportunity

to receive training for and promotion to the better-paying jobs

at the Company. [See Pi. Br. 14-16, A. 159-71, Section I, supra]

It is also clear that Blacks earned appreciably less than whites

15/with comparable seniority. The 3,404 black production and

maintenance ("P&M") workers who earned more than $3,500 for the

year 1970 averaged for that year $8,150.09 in gross earnings;

whereas, the 6,236 white P&M workers who earned more than $3,500

for the year 1970 averaged for that year $9,940.09, or $1,790 or

16/22% more than black workers. [X189, attached hereto as

Appendix "A"]

The Company attempts, by various methods, to demonstrate

that the clearly inferior earnings of black employees at Fairfield

Works since July 1, 1965 has little or nothing to do with the

discriminatory practices. It may well be that some of the marked

difference in average hourly or gross earnings between black and

white workers is not due to the discriminatory practices at

17/

Fairfield Works, but rather to other factors. [See A. 160]

However, the question presently before this Court is not the specific

15/ The enormous disparity in earnings is graphically demon

strated by X189 which is attached hereto as Appendix "A".

See also X101.

16/ The disparity in average hourly earnings is just as

startling. [X 102]

17/ Of course, the reverse is also true. An individual black employee, given equal opportunity, may well have out-earned his

white contemporary, rather than just equaling his earnings.

11

\

amount due the class of affected employees, or to a specific

employee, but rather whether the defendants are liable to the

affected class for economic loss suffered as a result of dis

crimination. See Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refining Corporation,

495 F .2d 437, 443-44 (5th Cir. 1974).

Nevertheless, it is necessary, for the sake of clarity and

accuracy, to respond to some of the statements made by the Company

concerning the statistical evidence, even though the relevancy

of those statements, if they in fact are relevant at all, goes to

18/questions of mitigation and not the question of liability.

The company primarily relies on the testimony of Dr. Gwartney,

an economist, who testified as an expert witness, and whose find

ings are incorporated in X1013. [C. Br. 11-19) U.S. Steel pre

sents Dr. Gwartney's testimony, including his charts, to this

Court, as if the testimony went unrebutted and as if the district19/

court relied on Dr. Gwartney's testimony in denying back pay.

18/ The Company admits to some disparity in earnings between

Blacks and whites. It is unnecessary on this appeal to argue

that the greater disparity demonstrated by the exhibits of the

plaintiffs are more accurate.

However, one gross inaccuracy should be clarified. The

Company states that 246 pattern makers and transportation workers

were erroneously included in the plaintiffs' statistics because

these groups were not represented by the Steelworkers and were

thus not involved in any of the consolidated actions. [C. Br. 9, n. 11] The "pattern and practice" suit was brought against United

States Steel for discriminating against black employees, not just

those represented by the Steelworkers. [A. 18-22] Similarly, the

Ford class involves all black employees, not just those represented

by the Steelworkers. [A. 128]

19/ The district court does not mention either Dr. Gwartney

or his charts [X1013] anywhere in its decision denying back pay.

[A. 147-75]

12

Dr. Gwartney's testimony, as described by the Company,

essentially purports to explain the earnings difference between

Blacks and whites in terms of "productivity factors": several

factors were quantified in terms of effect on earnings such as

2education and "freezes", i.e., the refusal of employees to promoteT

It is incredible that the Company represents Dr. Gwartney's

testimony on "freezing" as unrefuted when the district court

specifically ruled that the testimony of Dr. Gwartney on "freezing"

was so riddled with error that it had to be excluded from evi-

21/dence. [Tr. Vol. 50, Nov. 30, 1972, at 164-65, 239-243]

While the district court did not exclude Dr. Gwartney's

conclusions, as set forth in X1013, concerning education, the

Court stated that these conclusions of course were dependent upon

20/ Dr. Gwartney also compared the earnings of Blacks at U.S.Steel with the earnings of Blacks in the Birmingham area, the South,

and the United States. [C. Br. 13-14, 37-40] This evidence is of no probative value.

Clearly the disparity in earnings between Blacks and whites

in various labor markets was partly the result of discrimination

within firms and partly the result of the fact that the black

unemployment rate is almost twice that of whites. U.S. Census

Bureau, Statistical Abstract of the United States (Washington, D.C., 1972), p. 221. Only the first type of discrimination is revealed

in the comparison of earnings of Blacks and whites at Fairfield Works.

At most, Dr. Gwartney's method of comparison may be interpreted to mean that the economic results of discrimination is some

what less severe at U.S. Steel than at other firms. This Court

has plainly held that even if an employer in "good faith" intended a policy of no discrimination if, in fact, the practices dis

criminated, then the employer violated Title VII and is responsible for back pay. The argument advanced by U.S. Steel is not even one of

good faith" — just that they may be a little less guilty than some.

2_1/ Pages 162-165 and 239-343 of Vol. 50, have been attached

as Appendix "B" hereto for the convenience of the Court.

13

the data used to make the study. [Tr. Vol. 50, Nov. 30, 1972,

at 240-41] On rebuttal the plaintiffs clearly demonstrated that

the educational level of Blacks had been consistently underre-

22/

presented in the data used by Dr. Gwartney.

In addition to the unreliability of the statistics used in

X1013, Dr. Gwartney in attempting to establish the "cause" of the

disparity in earnings between Blacks and whites, simply ignored

important factors of discrimination. For example, he used "craft

training" as a variable but did not examine the current dis

criminatory effect of the discriminatory exclusion of Blacks from

23/training for or for promotion to craft jobs. Finally, Dr.

Gwartney, even though he was aware that up until 1962-63 Blacks

and whites were segregated into separate jobs and LOPs with Blacks

generally in the lower-paying jobs, made no attempt to study the

continuing economic impact of this discriminatory practice.

[Tr. Vol. 50, November 30, 1972, at 202-09] Dr. Gwartney's refusal

to consider the major discriminatory practice of the defendants, the

lock-in effect of the seniority system of a past segregated job

assignment system, makes the study, X1013, irrelevant at best.

22/ Approximately fifty witnesses were put on by the plaintiffs

who testified that their educational level was higher than represented

in the statistics used to compile X1013. Tr. Vol. 52, December 4,

1972, 135-177, 247-8, 256-269; Vol. 53, December 5, 1973, 56-65, 124-

128, 190-201; Vol. 54, December 6 , 1972, 2-6, 59-64, 237-41.

23/ See the district court's examination of Dr. Gwartney on this

point, Vol. 50, Nov. 30, 1972, at 23-25 and also cross-examination,

Vol. 50 at 192-199. These pages are attached hereto as Appendix "C".

14

The Company also relies on "post-trial statistics re

quested by the Decree". [C. Br. 20-8] These statistics are not

before this Court; the Court cannot properly evaluate evidence which

is over a thousand miles away and is only referred to in the form24/

of conclusory statements in defendant U.S. Steel's brief. More

importantly, any evidence of post-trial promotions or refusals to

promote cannot have any relevance to the question of liability, the

only question before this Court; if such evidence has any relevance

at all it is for the question of mitigation. On remand the dis

trict court may properly decide if the evidence has relevance for

25/

the question of mitigation.

III.

IN LIGHT OF THE PLAINLY UNLAWFUL PRACTICES OF

THE DEFENDANTS WHICH RESULTED IN SUBSTANTIAL

ECONOMIC HARM TO THE AFFECTED CLASS, THIS COURT

SHOULD REVERSE THE LOWER COURT'S DENIAL OF BACK PAY

The Union argues that the district court's denial of back

pay may be affirmed by this Court as a sound exercise of the court's

discretion under the principle of law enuniciated by the Court in

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Company, supra, and in Johnson v.

2 4/ As discussed in the section on Dr. Gwartney's testimony

some of the statistical evidence presented by the Company at

trial was not always reliable.

25/ Plaintiffs do not in any way admit the sweeping generali-

i^tion drawn by the defendants from the post-trial reports. The validity, accuracy and interpretation of these reports may properly

be explored at a remand hearing on the calculation of back pay.

15

Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., supra. The union candidly admits

that the lower court's reasons for denying back pay, e.g., the

"good faith" of the defendants, difficulty of calculation, and

"equitably determining the true balance of interests", have been

declared by this court to be invalid reasons for denying com

pensation for economic harm suffered by Blacks as a result of dis-

27/

criminatory employment practices. However, the Union attempts

to recast, at least in part, the district court's rationale for

denying back pay in terms of the "special circumstances" standard:

Once a court has determined that a plaintiff

or complaining class has sustained economic loss from a discriminatory employment practice, back pay should normally be awarded unless

special circumstances are present.

(footnote omitted).

* * *

The 'special circumstances' where an unjust

result has prevented an award of back pay

have been narrow.

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Company, supra 252-54.

In particular, the Union argues that the "unique litigation

history" involving the steel industry creates a special exemption

26/

26/ U.S. Steel as set forth, supra, argues that the evidence does

not support a finding of discrimination or alternatively that the

discriminatory conduct did not result in economic harm. The Union

does not deny that discriminatory practices at Fairfield Works

resulted in economic harm to the affected class.

27/ Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company, 3upra; Pettway

v. American Cast Iron Pipe Company, supra; Franks v. Bowman

Transportation Company, 495 F.2d 398, 421-22 (5th Cir. 1974);

Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refining Company, 495 F.2d 437, 442-44

(5th cir. 1974): Duhon v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company, 494 F.2d

817, 819 (5th Cir. 1974); Carey v. Greyhound Bus Co., Inc.,

No. 73-3133 (5th Cir. Sept. 26, 1974).

16

from judicial awards of back pay. (Union Br. 21-27) This argument

is totally inconsistent with this Court's standard for awarding

back pay which is firmly based on the fundamental purpose for such

an award - to compensate the victims of discrimination.

The Court had made plain that the "unsettled" state of the

law is no defense to a valid claim for back pay. Johnson y.

Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company, supra; Pettway v. American Cast

Iron Pipe Company, supra; see also Pi. Br. 48-49. However, the

Union proposes an imaginative expansion of the holding in Johnson

that liability for back pay under 42 U.S.C. §1981 should not

extend beyond the effective date of Title VII, July 2, 1965.

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber company, supra at 1378. The

Court founded this ruling on two grounds: (1) it was not until the

effective date of Title VII that "employers clearly became aware

that they would be held accountable for employment discrimination",

and (2 ) uniformity in the application of back pay is necessary.

Id. 1378-79.

On July 2, 1965 the steel companies just like other industries

received notice that they would be responsible for their unlawful

practices of discrimination . Furthermore, to establish different

dates by industry, on the basis of district court interpretations

of Title VII, for when back pay could be awarded would create a

crazy quilt pattern: Blacks might be able to receive compensation

for economic harm for example, after 1970 in the steel industry,

after 1971 in foundry operations, after 1972 in the petro

chemical industry, etc.

The gist of the Union position is that on the basis of

Whitfield v. United Steelworkers, 267 F.2d 546 (5th Cir.1959),

17

an action brought pursuant to the duty of fair representation,

29 U.S.C. §§151 et seq., the United States v. H.K. Porter Corp

oration . 296 F.Supp. 40 (N.D. Ala. 1968), U.S. Steel and the

Steelworkers had a reasonable basis for believing that seniority

systems in the steel industry were not in violation of the law.

It should be noted that this defense is closely analogous

to the defense of American Cast Iron Pipe company ("ACIPCO") with

respect to the use of the Wonderlic Test: ACIPCO argued thatp the

use of a professionally developed test, such as the Wonderlic, had

28/been held by various courts to be lawful. Of course, the Supreme

Court rejected this argument in April, 1971. Griggs v. Duke Power

Company, 401 U.S. 424 (1971) Shortly after the Supreme Court's

decision ACIPCO ceased employment testing; yet the Court held ACIPCO

liable for all back pay discriminatory practices, including testing.

lPettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Company, supra. See also

United States v. Georgia Power company, 471 F.2d 906 (5th Cir. 1973)

Moody v. Albemarle Paper Company. 474 F.2d 134 (4th Cir. 1973).

Similarly, the unsettled law concerning steel seniority systems

under Title VII may not be used as a defense to back pay claims.

Furthermore, this Court made it clear, years ago, contrary

to the Union's assertion, that there was no exemption from Title VII

for the seniority system in the steel industry. In Taylor v. Armco

Steel Corporation, 429 F.2d 498 (5th Cir. 1970), which involved

28/ See Griggs'v. Duke Power Company, 420 F.2d 1125

(4th Cir. 1970).

18

the same facility as the Whitfield action, the Court stated that

seniority practices lawful under the duty of fair representation,

2 9 U.S.C. §§151 et_ seq., were not necessarily lawful under Title VII.

Moreover, when United States v. H.K. Porter Company, Inc.,

297

was argued, on April 21, 1970, the Court indicated from the bench

"that major changes in the seniority and other systems at the plant

were required in order to achieve compliance with Title VII"; the

Court directed the parties to confer towards the purpose of pro

viding the Court with a proposed decree. United States v. H.K.

Porter Company, Inc., 491 F.2d 1105 (1974).

Finally, the district court did not consider that the

"unique" history of Title VII litigation in the steel industry pre

cluded an award of back pay, since the court in fact awarded such

relief to sixty-one black workers. [A. 142-45] See also Bush v.30/

Lone Star Steel Company, 373 F.Supp. 526 (E.D. Tex. 1974)

IV.

31/THE CONSENT DECREES DO NOT PROVIDE ANY BASIS FOR

DENYING BACK PAY TO THE AFFECTED CLASS___________

The defendants have incorrectly relied on the consent decrees

in their briefs. The Company maintains that assuming back pay is

2 9/ The Union was a defendant in that action.

3 0/ in fact, seniority systems in the steel system have been re

peatedly found to have been in violation of Title VII. [A. 159-61];

United States v. H.K. Porter Company, supra; United States v. Beth

lehem Steel Corp.. 446 F.2d 652 (2nd Cir. 1971); Bush v. Lone Star

Steel Company, supra; Taylor v. Armco Steel Company, & EPD 1(9550 (S.D.

Tex. 1973); In the Matter of Bethlehem Steel Corporation, Decision

of the Secretary of Labor, Docket No. 102-68, January 15,1973 EPD 1(5128

31/ See 1-2, n.lr supra.

19

appropriate or required in this case, then the Court should simply

approve the back pay awarded in the consent decrees. The Company

represents to the court that "back pay has now been awarded by

subsequent mofification of the trial court's decree". [C. Br. 67-68]

This is not true. The defendants' motion, joined by the EEOC, to

amend the Fairfield Decree to include the back pay provision in

the consent decrees was denied by the district court at hearing on

October 3, 1974. The plaintiffs-appellants argued, and the district

court agreed, that it would be inappropriate, as well as beyond the

authority of the district court, to incorporate the back pay pro

visions of the consent decrees in the Fairfield Decree at this

time with appeals pending before this Court concerning both the

Fairfield Decree and the consent decrees.

The Company further maintains that the method utilized by

the trial court to determine the award of "back pay in the Consent

Decrees" is consistent with the guidelines established by this

Court in Pettway. This argument distorts the carefully designed

suggestions for calculating back pay set forth in Pettway.

The Court established a basic principle - the award of back

pay should be calculated in order to restore the Blacks who

suffered from discrimination to the economic status which they would

have attained but for the unlawful practices of the defendants.

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Company, supra at 252, 263.

The court also established two corollary principles to insure the

award of full back pay:

20

Therefore, in computing a back pay award

two principles are lucid: (1 ) unrealistic

exactitude is not required, (2 ) uncer

tainties in determining what an employee

would have earned but for the discrimina

tion, should be resolved against the dis

criminating employer, (footnotes omitted)

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Company, supra at 260-61, see

also Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refining Corporation, 495 F.2d 437,

32/

445 (5th Cir. 1974).

The Company does not mention any of these principles in

asserting that the settlement of back pay in the consent decrees

was consistent with Pettway; rather, the Company relies on the

single fact that the EEOC participated in the consent decrees and

approved the back pay provision. In Pettway the Court, among other

suggestions, proposed that the district court in determining back

pay may want to refer the matter to a Special Master or to use the

EEOC to 11 supervise settlement negotiations" or to aid in determining

the amount of the award." (emphasis added) Id. at 258. Certainly,

the Court did not mean to suggest the approach followed in this

action. The EEOC, reached an agreement, after plaintiffs had

filed their brief on appeal, with nine steel companies and the

Steelworkers which provides a lump sum of back pay to all black,

female and Spanish-surnamed Americans in the steel industry. The

trial court did not in any meaningful sense approve the calculation

of that award for the simple reason that the calculation of that

award remains a total mystery. To this date there is no record

32/ See Pi. Br. 38-46.

21

of (1 ) how the award was calculated, (2 ) what period of time the

award purports to cover, (3) the amount of the award which is de

signated for black workers at Fairfield Works, or (4) the amount

of money which any individual will receive at Fairfield Works.

Pettway does not empower the EEOC to totally usurp the authority

of the district court to determine what is an appropriate award,

by an in camera negotiation procedure to which the real parties

in interest, the black employees, are excluded, and reached by a

method of calculation which is not revealed to the court nor to

33/the plaintiffs. * 1 2 3

3 3/ it should also be noted that the $30.9 million settle

ment figure for over 60,000 Black, female and Spanish—surnamed

Americans appears on its face to be inadequate to provide full back pay. The consent decree figure provides for approximately $500 per person; whereas, the sixty-one employees who

received back pay in these consolidated actions received over

$200,000 in back pay or almost $3,300 per man. [A. 142-45]

Moreover, the consent decrees provide that in orderfor

an employee to receive back pay he must execute a release which

purports to waive, inter alia, certain prospective rights:

1. The right to sue for additional injunctive

relief if the Decree does not eliminate the

continuing effects of past discrimination.

2. The right to sue to enforce the Decreesif the defendants fail to comply with their

provisions.

3. The right to sue for back pay or damages which

may arise in the future by reason of the defendants' failure to eliminate the con

tinuing effects of past discrimination.

The intervenors-appellants argue that such a waiver of pro

spective rights is unlawful. Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Company.

39 L.Ed.2d 147, 160 (1974). In any case plaintiffs,if they

prevail on this appeal# are entitled to full back pay without

having to waive their rights to prospective relief.

22

Finally, the Company neglects to mention that the class

of black employees represented by Ford is broader thatn the class

of black employees entitled to back pay under the consent decrees

in three respects: (1) the Ford class includes all those Blacks

hired at the plant prior to January 1, 1973, whereas the consent

decrees provide back pay for only those employed prior to January

1 , 1968; (2 ) the consent decrees award back pay only to those

Blacks who were working at Fairfield Works on April 12, 1974 or

who retired since 1971 (3) on pension, while the Ford class does

not exclude those who retired before April 12, 1972 or who did not

retire on pension. /

V.

THIS APPEAL IS PROPERLY BEFORE THIS COURT

U.S. Steel challenges the propriety of the action of the

court below in expanding the class represented by the appellants

Ford et al. to include also those black employees whose interests

had been represented at the trial by the United States and who were

not also members of any of the other private action classes.

34/

(C. Br. 52-59).

We respectfully submit that these objections — whether char

acterized as relating to standing, to the creation of an invalid "felse'1

class, or to an alleged conflict of interest -.are utterly specious.

34/ The Union expresses doubt as to this question but urges

that these considerations not be allowed to serve as a barrier to

the disposition of this appeal on the merits. (U. Br. 29, n.ll).

23

1 . First of all, the issue is pot before this Court,

The defendants could, of course, have appealed that portion of the

decree of the court below that expanded the Ford class (A. 128),

either before or within 14 days after service of appellants' notice

on appeal. Rule 4(a), Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure. They

elected not to do so. The correctness of the decision of the dis

trict court with respect to the definition of the class may

therefore not be raised in this court.

2. Even if the issue was properly here, this aspect of

the decree, far from constituting reversible error, was a wise

exercise of judicial discretion.

The decree came at the end of a consolidated trial, in which

there were joined a number of private class actions and a govern

ment "pattern and practice" action, all alleging racial discrimina

tion in employment at United States Steel's Fairfield Works. The

trial was conducted under a rule that evidence introduced in any

part of the trial could be used where relevant in connection with

any of the actions consolidated. The government case alleged

plant-wide racial discrimination and asked for back pay for all

victimized Blacks, as well as plant-wide injunctive relief. (A.

18 et seq.) Evidence was introduced relating to the loss of

earnings by all black employees, not merely by those who were

members of the classes represented in the private actions. See

Section II, supra.

The district court decreed back pay for certain members of

three private classes, while denying it to those employees repre —

24

sented only by the government. At the same time, the lower court

took measures which would have the effect of ensuring that the

latter group would have an opportunity to test on appeal its denial

35/of relief to them. Since it was not certain whether the govern

ment would continue to assert their rights on appeal and with

the benefit of hindsight we can see how justified these doubts in

fact were — the court expanded the Ford class so that these

employees would continue to receive adequate representation.

This procedure served the important interests of judicial

economy and speed. The affected employees could probably have still

instituted an independent action for relief, even at that late

date. Williamson v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 468 F.2d 1202 (2d Cir.

1972), cert, denied, 411 U.S. 973 (1973). But the issues had al

ready been tried; to require their retrial would have been onerous

and wasteful.

The Company makes the inconsistent contention, in another

part of its brief (pp. 77-87) that the decision denying these

employees back pay is res judicata, although they were not, tech

nically, parties. This is a dubious proposition. Cf. Gonzales

v. Cassidy, 474 F.2d 67 (5th Cir. 1973); Williamson v. Bethlehem

35/ The district court recognized the importance of a full deter

mination of appropriate relief for discrimination ; accordingly, t

Tiwer cSu?t insured the right of the affected class to appeal

similarly in United States v. Hayes International Corp., 456 F.2d 119 121 *(5th Cir 1972) the court considered that back pay was suchai integril^ert of a Title VII remedy that it required the issue to

be fully determined on remand even though the question of back

pay "was not specifically raised until the post-trial stage of

litigation".

25

Steel Corp., supra. But if it is correct, it would be all the

more reason to ensure that this group of employees be given the

opportunity to test on appeal the correctness of the decision

adverse to them. The Company would make the adverse decision on

back pay binding upon these employees and at the same time deprive

them of their only effective opportunity to obtain its reversal.

While adjustment of the membership of a class at the end of

a litigation is unusual, it is not unique. See, e.g., Sproqis v.

United Air Lines. Inc.. 444 F.2d 1194, 1202 (7th Cir. 1971) cert

36/

Honied 404 U.S. 991 (1971); 7 Wright & Miller, Federal Practice

and Procedure §1754 (1972). Orders in the conduct of class actions

"may be altered or amended as may be desirable from time to time."

37/Rule 23(d), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure ("FRCP"). "This

passage emphasizes the judicial flexibility that characterizes

the entire subdivision". 7A Wright & Miller, supra, §1791 (1972).

The defendants in the instant case suffered neither surprise nor

prejudice. In the context of this litigation, this exercise of

judicial flexibility was entirely appropriate.

The arguments advanced by the Company as to Ford's standing

(Brief, pp. 52-55) are not in point. Ford was and is a black

36/ It should be noted that on remand the district court deter

mined that a class action was not appropriate; however, the court

relied on the fact that the claims of the class members were not

presented at trial - a rationale which is plainly inappropriate to

this appeal. Sproqis v. United Air Lines. 56 F.R.D. 420, 423

(N.D. 111., 1972).

3 7/ it may also be sustained independently as "a class action

with respect to particular issues". Rule 23(c)(4)(A), FRCP.

26

employee at the Fairfield Works of U.S. Steel, seeking redress

for racial discrimination in employment. There is nothing .in

appropriate in his representing a class of black employees at the

Fairfield Works of United States Steel who also seek redress from

racial discrimination in employment. Whehter the class represented

by Ford should be only those in the Pratt City Car Shop, or should

also include all or most of those in the rest of the Fairfield

Works, involves only questions of discretion relating to efficient

judicial administration — not questions of standing. And there

is nothing inherently inappropriate in a plant-wide class involv

ing large numbers of employees. Cf. Pettway v. American Cast—Iroii

Pipe Co.. 494 F.2d 211 (5th Cir. 1974).

The fact that back pay was awarded by the district court to

some of those in the Car Shop did not disqualify Ford from repre

senting on appeal both the Car Shop employees — in the event that

they wished to appeal for greater relief or in the event that they

were faced with an appeal by the defendants — as well as other

black employees with parallel claims for back pay. He was, as

noted above, a member of the class of black employees at Fairfield

claiming employment discrimination. And the question whether his

claims were "typical of the claims . . . of the class (Rule 23(a))

is similar to the question which he raises on the merits in this

appeal - that those employees are equally entitled to back pay.

Moreover, to satisfy that test it is not necessary that Ford's

claims to back pay be identical in every particular with those of

all members of his class; varying fact patterns or differences in

27

damages claimed are not barriers to serving as class repre

sentative. See Arkansas Education Assn, v. Board of Education

of Portland, 446 F.2d 763, 767 (8th Cir. 1971); 7 Wright & Miller,

supra. §1764. Nor is the case one in which there is the slightest

semblance of conflict of interest; back pay for one group of

employees will not result in a reduced award to others, and the

interests of all can be consistently and vigorously protected. The

ffact that Ford and some others from the Car Shop have now been paid

in full - stressed by the Company at p. 58 of its brief - does not

mean th^bhe is incapable of continuing to represent other members

of the class whose rights are still in dispute. Jenkins v. United

38/

Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 28 (5th Cir. 1968).

38/ Ford's intervention in the entirely separate matter of

united States v. Alleaheny-Ludlum. Industries. Inc,. No. 74-3056,

is entirely irrelevant in the instant case. Moreover, there is no inconsistency between his positions in the two cases. In

Allegheny-Ludlum he is opposing a settlement, which violates the

rights of black employees to full relief from employment dis

crimination. His objective in both cases is identical - to secure

for black employees all of their legal rights.

28

The added members of the class represented by Ford need

more vigorous representation than the government apparently

intends to accord them. The Court below felt that representation

by Ford, and Ford's attorneys, would serve their interests

best.

Respectfully submitted,

OSCAR W. ADAMS

JAMES K. BAKER

U. W. CLEMON

Suite 1600 - 2121 Building

2121 Eighth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

JACK GREENBERG JAMES M. NABRIT, III

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

ALBERT J. ROSENTHAL New York, New York 10019435 West 116th Street

New York, N.Y. 10027

Of Counsel

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

29

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 11th day of October,

1974, I served two copies of the foregoing Plaintiffs-

Appellants1 Reply Brief upon each of the following counsel

of record by depositing copies of same in the United States

mail, adequate postage prepaid.

James R. Forman, Jr., Esq.

Thomas, Taliaferro, Forman, Burr & Murray

1600 Bank for Savings Building Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Jerome A. Cooper, Esq.Cooper, Mitch & Crawford

409 North 21st Street

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Demetrius C. Newton, Esq.

Suite 1722 - 2121 Building

2121 Eighth Avenue North Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Beatrice RosenbergAssistant General Counsel

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

Office of the General Counsel1206 New Hampshire Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20506

Michael H. Gottesman, Esq.Bredhoof, Barr, Gottesman, Cohen & Peer

1000 Connecticut Avenue

Suite 1300

Washington, D.C.

S b A c k k * , __________

Attorney for Plaint iffs-Appellants

f K f f l

APPENDIX "A"

Tut following sots forth the average gross earnings in _

* ■*' V*calendar year. 1970 for all active white and Negro PS-.M

employees with gross earnings of $3*500.00 or more.

Year 8 i f V/ Avg. V/hit9

35+ ' . 92 10,727.44 •79

34- 100 10,694.39 . 114

33 -146 ■ 11,006.78 123

32 i75 11,341.94 58

31 139 10,692.24 • 55

30 183 10,848.30 180

29 313 10,517.22 198

28 322 10,411.70 • 129

iAvg. Negro Difference - ."1 11 '•."i ■

8,635.60 2,091.84 .■••j;-'.• V \ .s '

8,507.42

* 8,733.52

2,186.9? %

<0

2,268.26 '! V •

9,170.58 2,171-36 4 '

8,864.31 1,827.93;%;'

8,6o9.57 2,153.73iV;"?'

• 8,554.97 1,962.85^ _

, 8,288.27 ' f. 9 y • f* J)

. l .

•

j.• * V.v 'V1 I

■ ''iV’v

■ mw.

" i'i ;y

A - /

j

i

luaxi

2.7

iL JiL

141

2 V. V ft • Will \j V

10,206.78 1 0 5

i k v ̂

8

A.*;

,164.24‘ 2,122.54

' 1 l 26 174 . 10,527.76 100 0 ,582.59 1,945.37

1i 25 225 1 0 ,1 7 5 . 6 6 190 8 ,089.07 2,086.59

' i 24- 321 10,459.94- 282 8 ,198.58 * 2,241.56

-{' . . K 23 425 • 10,101.89 247 8 ,287.25 ' '1,814.66

i • 22 476 10,186.94- 258 8 ,117.12 5 2,069.82

21 274- 10,168.61 111 8 ,075.40 • 2,093.21

. i

r . 20 333 9,861.53 128 8 ,189.24 1,672.29

. . I * 19 299 9,826.79 157 8 ,257.01 1,589.78

• *9

i . 18 295 9,870.94 101 ' 8 ,354.07 1,516.87

ii

■■1

i

17 218 '10,119.07 75 8 ,565.53 1,555.54

16 5 8,658.85 0

I. •' • 15 1 3 2

9,852.45 .... 6 7-T530.01 . 2,302.44

• 1

- 1 14 85 10,14-1.07 40 8 ,1 5 1 . 8 5 1,989.24

i • - 13 141 9,158.61' 65 .7,5 1 9 . 1 3 1,639.48«i

•vi •ii

12 6 . 10,736.17 0

11 145 9,191.69 55 8 ,228.15 965* 56

■1. i:•)• - j

. ’ i

10 82 9,301.85 14 7 ,651.37 1,670.46

9 25 9,825.97 1 6 ,467.61 3,356.36

• •. . • i 8 30 8,801.71 1 8 ,209.75 591.96

• ■ i 7 33 9,533.01 • 2 5 ,480.67 • • 4,052.34

S- * 6 153 9,305.41 77 7 ,536.58 1,768.83

5 -166 8,525.05 141 7 ,589.79 935.24

•J

X 4 72 0,970.76 39 7 ,544.79 1,425.97

•

3 111 7,945.11 101 7 ,222.52 722.79

1 2 129 8,457.54 35 ' 7 ,286.91 1,170.63

1 278 7,825.54 181 e>,864.45 959.11

h - 2 .

p

i1

i

8

Federal Court Reporting Company

409 Federal Building

Birmingham, Alabama APPENDIX B -Trt-

l

—

Q Let me get another quealon here with re-

16Z

2 garde to, for inetance, with the freeze data.

3 It your assumption that with regard to

4 researching that data and compiling it, that the

5 company devoted equal effort to finding whites 1

6 who had frosen and identifying them, and the data

7

Jand so on and so forth, that equal effort went into j

8 '

9 A Well, the freexe data are a little bit; they

10 are a little bit like apples as compared to an

11 orange, for this reason: that the freexe data have

_ 12 to do with the individuals who were entered in

13 the court proceedings.

14 Now, whether it is true that the company I

15 q uite likely searched more diligently for black

16 freexes than white freexes, 1 think it is also

17 true that the government, including the government

18 attorneys, have a tendency to search more diligently1

19 for white freezes than black freezes.

20 T H E COURT: I don't b e l i e v e — I don't

21 believe, Mr. Moore, we need to go into any more

22 details on the freexe situation. I think you can

23x_•

move on to something else.

'B-f

t

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

Federal Court Reporting Company

409 Federal Building

Birmingham, Alabama

MR. MOORE: All right, Your Honor. I do hove;

on e more question with regard to the counting

of temporary and permanent freezes, if I could.

In this freeze data. I don't know if you have

that one before you. but one last question. I am

showing you again Exhibit 880, the Exhibit indi

cates , and it says so on it, that the nature of

the freezes, whether the offer was for a permanent

promotion, or temporary promotion, but if you

will notice here on this 880, there are people I

who are shown to have declined a temporary pro

motion; do you understand the difference between

a temporary and permanent promotion?

A No; I don't.

Well, the word "temporary", sort of implies

something. I take it that one of them is one that

would be thought of as permanent promotion, and

t emporary is one that would be altered at some

future time, designated or undesignated, and beyond

that I have no comprehension of what the technical

term means in that case.

Q Do you understand that in the freeze infor

mation supplied to you which appears in Table 15,

E - 3 -

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

Federal Court Reporting Company

409 Federal Building

Birmingham, Alabama

namely the number of employees who have frozen,

that they are both temporary and permanent freezes?

A I did not put that data together; the discus

sion never came up with me.

Q Well, with regard to Table 21, and the im

pact of freeses, can you tell us whether or not in

your opinion that Impact would be affected by

whether or not the freezes which were counted,

and went into the data that determined the ratio

of white freeses to black freeses, that that data

had situations in it where persons were declining

simply on a one day temporary step up?

MR. MURRAY: Judge, he already asked this

question several times, and the witness has

already answered it; that is the first question

he asked.

MR.MOORE: I haven't asked about temporary

and permanent.

THE COURT: You have asked about it, and Mr.

Moore, I am not going to allow or receive the

portion of Tab£e, 21 relating to freezes.

Now, if you want to keep hammering on it,

you awy, but I am going to rule in your favor on

" B - 3

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

Federal Court Reporting Company

409 Federal Building

Birmingham, Alabama

the freeze pert of Table 21.

MR. MOORE: Yes, sir.

:

I

I

!I

' B - V

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

Federal Court Reporting Company

409 Federal Building

Birmingham, Alabama

Mr. Moor* 1* In error when he talk# about being an

i /

lapaet on*70 earnInga; he hao misstated the caae.

MR. MOORE: Table 20 earning*.

THE COURT: Are there other particular table*f

that you are referring to in that contest?

MR. MOORE: Of course, that i* in a — in

Table 21, the information that goes into Table 21,

of course, came from Table 17, which says estimate

impact of days in pool and missing bids amt of

pool on annual earnings la 1970. ,

THE COURT: All right. i

MR. MOORE: And this is by testimony, la the iIfootnotes, in the exhibit connection to those,

of course, I think — well, that item, we would move

that that be stricken; I think that the reliability■

of these figures, that of course other testimony

and other evidence goes much to the weight, but I

believe — or with regard to the testimony of an

expert concerning a hypothetical that the reliablllt:

of the information going into it, and that it is

the end product goes also to really its tieslblilt

and therefore, we object to t o o that ground, to

the admissibility of 1013.

"B - S ’

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

Federal Court Reporting Company

409 Federal Building

Birmingham, Alabama

THE COI»T: Of course, you have other objections

going to weight, which ere aot strictly objections

but trgusests egnlast the weight.

MR. MOORE: Yes, sir.

THE COURT: Do private plaintiffs have ob

jections In addition to those stated by the

Goveraaent? /

MR. COAR: Your Honor, we object to Exhibit

Table 4, 5, and 7 on the grounds of relevancy and

aaterlallty.

MR. MOGRE: We would, of course, object to

It on the grounds of relevancy and aaterlallty

In light of particularly the testlnony which bears

on the weight of it.

THE COURT: I aa going to overrule objections

as to reIsrancy and aaterlallty as stated by the

parties.

I sustain the objection as to the part of

Table 21 dealing with Job freeses for the reason

that the coaparable figures in Table 15 which are

used to support that are factually froo two dif

ferent types of salsa Is, that is, the freeses,

so to speak, blacks, and the freeses of whites, as

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

Federal Court Reporting Company

409 Federal Building

Birmingham, Alabama

derived from the record in the cose, that ore

|arrived at In two different ways; this court per

mitted evidence of black freezing, whether or not

they were passed by blacks or whites, but only

in essence allowed evidence of white freezing,

If they were passed by blacks.

Furthermore, there was a difference la the

cot-off date for the two categories, and to soae

degree a difference In the effort at eempleteness

of number of freezes, the end result being that

the line one dealing with job freezes la attempting

there to make measurements that go back to the

guestions of number of blacks freezing, and number

of whites freezing, simply cannot be compared based

on the data upon which they are based.

Bow, I overrule the objections as to all the

other items Insofar as data base Is concerned. As

far as the educational data, of course, and the

possibility the government may have other evidencev

at a later point to dispute the accuracy of the data

about education that appears on the cards, employ

ment record cards, even though It may be premature

•t this time, nevertheless, what I see that this

T - 7

Federal Court Reporting Company

409 Federal Building

Birmingham, Alabama

•tody does isatteapt to Mtaare a correlation

between educational data as shown on these euploy-

•eat records versus earnings oa those — versos

earnings rather than showing a correlation between

actual educational levels and earnings. Hew, if

there is a variance between actual education and«

the educational level shown on the euployaeat cards;'

this will go to the weight, but as far as this

study is concerned, it can only be taken, as I

see it, as a Measure of correlation between the

. ‘ (

data given to the witness and that which he arrived

at. It can't be given wore than that. How, insofar

ias the use of post-1970 data, for exaaple, in the

refusals to bid, I do not see this as a reason to

elininate the study aade; it would, for exaaple,

be possible to look at earnings in 1970 and see if

there is a correlation between that and refusals

to bid that took place solely after 1970. How,

if there is a correlation that nay have sene signi

ficance, enough to prove that poet *70 refusals

to bid were a cause of difference in earnings,

because obviously they couldn't be a cause, but the

post 1970 refusals to bid could be a result of name

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

Federal Court Reporting Company

409 Federal Building

Birmingham, Alabama

other factor which in turn woo a cease for the

earning differential that Is involved*

The study, as I see it, that is being pre

sented, is not ultimately a study that is being

presented in causation, but a study of correlation

between the factors.

It is up to the court after hearing argument

and hearing a 11 the evidence to make such deter

minations as are needed to causation.

Furthermore, as an example, that this wit

ness has found some statistical significance -in

correlation between quantity of schooling and

earning# does not mean that that indicates, or at

least to that extent, a lack of discrimination on

the part of the employer for the reason that school

requirements in essence cannot be, at this point

in time, used as a determinant of earnings by a

company, that is, a qualification unless there is

a violation of such a requirement to the extent then

that any educational requirements, for example,

may have contributed to a difference in earnings.

This may be so, but it doesn't indicate whether it

is discriminatory or non-dlscrlmlnatory. I am

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

Federal Court Reporting Company

409 Federal Building

Birmingham, Alabama

saylug all of this to indicate th« limitations I

its opon the study; 1 think it is of soma value,

but it doas not ultimately answer the question,

even assuming the probative value of the statistics

as to causation, or whether there is dlscriainatlon

that now is prohibited by law; I should say this:

that as I see the study made and educational

measurement, for example, may have aa Influence,

for example, on an employee *s perceived ability

or capability to do a job, it may have a bearing

on the esq»loyee*s attitude and motivation, and

it nay have other iaqpacts. So, that although the

study attempts to look at measurable

14 Is not necessarily the same criteria that

the court is going to have to look at.

How, with that rather lengthy explanation of

the ruling, 1 do receive the balance of Exhibit

1013 into evidence with the exception of the

part dealing with job freuses.

T i - i o

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

federal Court Reporting Company

409 Federal Building

Birmingham. Alabama APPENDIX "C"

plumber. He works perhaps as an a p prentice,

then wor k s his way up from the a p p r e n t i c e to a

skilled carpenter an d acqu i r e s skill. And that

this takes place for a period of ten years Just

as a h y p o t h e t i c a l — I could have used two.

It di d n ' t make that much difference. But ifwe

look at these two i n dividuals ten years later

while the firm has followed this d i s c r i m i n a t o r y

policy, ten years later these i n d ividuals in

terms of p r o d u c t i v i t y c h a r a c t e r i s t i c s and their

c u r rent p r o d u c t i v i t y c h a r a c t e r i s t i c s a r e d i f f e r e n t

individuals. One individual is hi g h e r skilled

than the other, even though had the first

individual, A, been g i v e n the same e m p l o y m e n t

o p p o r t u n i t i e s that tfen years later he very well

would have had the same skill level ad the

individual B. No w --

THE COURT: Let me stop y o u there. Isn't

that a p r e s e n t ef f e c t of past d i s c r i m i n a t i o n

rather than past effect of past disc r i m i n a t i o n ,

the e x ample y o u have just used?

A Wel l , it will h a v e a present e f f e c t on

product i v i t y , but in terms of its impact on

earnings, the impact on earnings is because of

the past discrimination. So I'm talking about

the impact pf earnings.

THE COURT: The past d i m i n u t i o n in

earnings is a past effect, but viewed let's

say at this mo m e n t the empl o y e e A is still let's

say the janitor.

A Uh h u h .

THE COURT: N o w is the current income

level, is a c u r r e n t e f f e c t a present effect?

A That's right.

THE COURT: It may be caused by the