Avent v. North Carolina Oral Arguments 2

Public Court Documents

November 7, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Avent v. North Carolina Oral Arguments 2, 1962. 0844fc78-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0c3458e7-3da3-4671-98f3-cf2f52915248/avent-v-north-carolina-oral-arguments-2. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

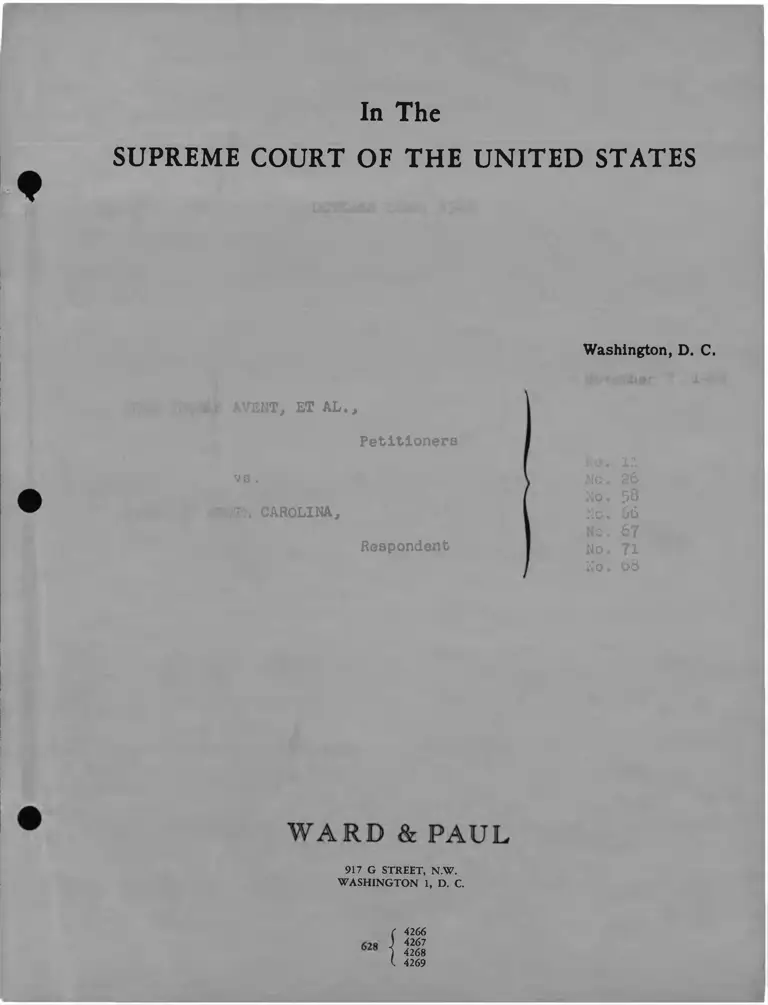

In The

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Washington, D. C.

;i.k A VENT, ET AL.,

Petitioners

vs.

?H CAROLINA,

Respondent

No. XX

No . 26

No. 58

No. 66

No. 67

No. 71

No. 68

917 G STREET, N.W.

W ASHINGTON 1, D. C.

( 4266

) 4267

) 4268

(. 4269

C O B T E N T S

le Court

/62

PAGE

ARGUMENT OH BEHALF OF CITY OF GREENVILLE, RESPONDENT

By Theodore A, Snyder — resumed 324

REBUTTAL ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF JAMES RICHARD

PETERSON, ET AL., PETITIONERS,

By Matthew J. Perry 330

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF NATHANIEL WRIGHT, ET A L .,

PETITIONERS,

Bv James. M. Nabrit, III 337

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF STATE OF GEORGIA, RESPONDENT,

By Sylvan A. Garfunkel 351

REBUTTAL ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF NATHANIEL WRIGHT,

ET AL., PETITIONERS,

By James M, Nabrit, III 388

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF THE UNITED STATES,

By Archibald Cox 393

AFTER RECESS - p. 403

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF THE UNITED STATES,

By Archibald Cu Cox — - resumed 403

REBUTTAL ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF THE STATE OF

MARYLAND, RESPONDENT,

By Joseph S. Kaufman 427

REBUTTAL ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF CITY OF

BIRMINGHAM, RESPONDENT,

By J. M. Breckenridge 438

Firsheira #1

et 1

321

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED

OCTOBER TERM, 1962

JOHN THOMAS AVERT, ET AL.,

Petitioners

VS,

STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA,

Respondent

*“* "* *“ ** “*

WILLIAM L. GRIFFIN, ET AL. Q

Petitioners

vs.

STATE OF MARYLAND,

Respondent

RUDOLPH LOMBARD, ET AL.,

V S .

STATE OF LOUISIANA.

Petitioners

Respondent

" X

JAMES GOBER, ET AL.*

vs.

CITY OF BIRMINGHAM.

Petitioners,

Respondent

STATES

HO. 11

NO. 26

HO. 53

No. 66

322

F. L. SKUTTLESWORTH, ET AL.,

Petitioners,

vs.

CITY OF BIRMINGHAM,

Respondent

Ho. 67

JAMES RICHARD PETERSOH, ET ALa,

Petitioners,

vs.

CITY OF GREENVILLE,

Respondent :

?

..................................X

NATHANIEL WRIGHT, ET AL.,

vs.

STATE OF GEORGIA,

Petitioners,

170. 71

170. 68

Respondent„ , „ „ x

Washington, D. C.

Wednesday, November 7, 1962

Oral argument in the above~entifcled matters was resumed

at 10:05 a.m

323

PRESENT:

The Chief Justice, Earl Warren, and Associate

Justices Black, Douglas, Clark, Harlan, Brennan, Stewart, White

and Goldberg.

APPEARANCES:

On behalf of Respondent City of Greenville:

Theodore A. Snyder, Jr. Esq.

On behalf of James Richard Peterson, et al., petitioners

Matthew J. Perry, Esq..

On behalf of Nathaniel Wright, et al., petitioners:

James M. Naforit, III, Esq-

On behalf of Respondent State of Georgia:

Sylvan A. Garfunkel, Esq.

On behalf of the United States:

Archibald Co::, Esq., Solicitor General

On behalf of Respondent State of Maryland:

Joseph S. Kaufman, Esq.

On behalf of Respondent City of Birmingham:

J. M. Breckenridge, Esq.

324

O 5 C E E D I N G S

The Chief Justice: No. 71, James Richard Peterson, et al.,

petitioners, versus City of Greenville.

Mr. Snyder, you may continue your argument.

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF CITY OF GREENVILLE,

RESPONDENT,

BY MR. THEODORE A. SNYDER, JR. resumed

Mr. Snyder: May it please the Court, one of the chief

issues in this case, as well as the other cases which has been

briefed before you gentlemen is the question of freedom of

speech, whether or not these petitioners were exercising any

right of freedom of speech when they staged this sit-in demon

stration.

We submit that they were not.

First of all, in considering the question of freedom of

speech, you have to consider where the traditional area for

speech in public speaking has taken place in this country, and

you will find on looking at the cases that the traditional area

of speech where you have people, to be begin with, who are not

speaking with each other as between associations and friends in

private discussion, is that they have to meet in the public

places for their discussion, that is, on the streets and in the

parks, in the places where ordinary people will come together

who had something that they wished to talk about, and we think

it is proper that people should have freedom to speak co each other

325et5

and try to convince others of their views when they meet in

public places, in a place like that, and we think they have a

right to go there to try to convince others of their thoughts

and of their ideas*

You go a step further, however, when you have a person

who wishes to try to convince someone else of his thoughts and

ideas when he goes on that man's private property to do so,

and chat is what you have in this case.

The petitioners, who claim they have been exercising the

right of freedom of speech, have left the traditional areas of

speech, which are out in the public, out in the open, and have

gone inside a store where they now seek to speak not to the

other public in general, not to someone who may, by chance, be

coming down the street, but they seek to speak to the owner or

operators or manager of this particular premises, so they have

narrowed down in two ways: one, they have moved away from the

traditional area of speech and, second, they have moved in and

they have narrowed their design to speak to a particular person,

and not to speak to anyone in general, anyone who may happen to

be present.

Now, they might have that right, and we do not deny they

have a right, to go to this store to attempt to speak to the

manager or to anyone who may be there. They have at least the

right to make an attempt to go there and begin a conversation.

But we submit that they do not have a right to stay there

I

326

and force the person they found there, whether he might be the

manager or someone else, to stay and listen to their ideas.

They have no right to force him to listen on his own

property when he does not desire to listen to them. If they do,

they take av/ay from that person his right of speaking himself.

He has no chance to do anything else.

The .lav/, even in the public places, as it has concerned

freedom of speech heretofore, has given the right of the person

who is spoken to either to refuse to listen or to require the

person who speaks to move away.

For example, in Cantwell against Connecticut, you had a

speech problem of persons where they would be listeners after

they had heard all that they desired to hear, required the

speaker to move on, or they could have moved on themselves

because they did not want to hear any more, and they had that

right.

You have the same question in the doorbell cases where,

on the ground of freedom of religion, a person has the right to

ring a doorbell to summon the householder, but the householder

is not required to stand there and listen to whatever the speaker

may have to say.

He has the right, if he dees not agree with the person, to

require him to move on. He is not required by any measure of

the freedom of speech to engage in a conversation with that

person if he does not desire tou That is what you have in this

327

case.

Here the manager, after he had heard the sound of the

argument presented co him by the petitioners, did not desire

to negotiate with them, did not desire to discuss the question

with them any further and he asked them to proceed about their

ovm business somewhere else; that was his right. He did not

have to sit there and listen to their demands hour by hour, and

when he had told them that, their duty was then to proceed and

take their conversation somewhere else.

Justice Goldberg: Mr. Snyder, would you mind at this point,

if it does not disturb the course of your argument, saying a

word about whether in connection with whether, the manager was

operating under his own steam, as it were, in this area, about

the propriety of the trial judge's action in refusing to permit

Mr. Perry to inquire into the question of whether or not there

had been prearrangement with the police to cake action in con

nection with the sit-in?

Mr. Snyder: I think in that connection, Your Honor, that

the petitioners would have had a right to prove, if they could

have, the fact that there was a prearrangement with the police

in which the police had directed the store manager or the store

owners to take the course of action that he did.

Justice Goldberg: You think it was foreclosed by this

ruling of the trial judge?

Mr. Snyder: I do not, sir, for several reasons.

etS 328

First of all, after the first objection v/as made and sus

tained, the witness, Mr. West, the manager, v/as asked for v/hat

reason did he then exclude the petitioners. And his answer

was not because of some prearrangement but because of the custom

and the ordinance which had been discussed, which v/as the ordin

ance, v/e submit, which prohibited trespass after notice.

Justice Goldberg: Would it not have been appropriate in

connection v/ith that answer to pursue the question of whether

the police had, in effect, asserted the ordinance with him,

because, as I read the record, and starting on page 22, where

that offer v/as made, Mr. Perry v/as foreclosed by the Judge,

unless he were to persist after a Judge's ruling, which he could

not very well, from pursuing that line of inquiry.

Mr. Snyder: We would not require him to persist after his

objection had been overruled. But under our procedure, Your

Honor, the man who has been foreclosed in this manner may, if

he desires and if he wishes to perfect and sustain his objection

there, he should have made an offer of proof into the record,

which he had a right co do.

In other words, he could have stated for the record at that

point, by way of an offer of proof, v/hat the testimony of the

manager was anticipated to be on that point, and he could have

done that had he so desired. But he did not. The fact that

he did not shows to us the fact that the manager could not be

expected to have testified as to any such arrangement.

et9 329

Justice Goldberg: Would you not read his comment af ter

the objection was sustained as being equivalent to an offer

o£ proof when he stated what he purported to bring out in this

line of questioning?

Mr. Snyder: No, sir? I do not read it that way. I under

stand what he was stating that his objection was that he desired

to attempt to show by cross-examination. But he did not state

that he expected the manager to testify to that effect, which

he would have had to have done if he wanted to make an offer

of proof in the case.

In conclusion, just let me say that we have here under the

14th Amendment the question of whether or not you are going to

have to balance two things really. You have a property right

on the one hand, in the hands of the property owner there.

On the other hand, you have the asserted right of these

petitioners to a portion of their liberty.

The Court, as I see this, has got to draw the line between

those two rights, which are both equally protected and, as I

read the amendment in the decisions, they are co-equal rights.

The Court has got to decide whether one right would give

way to the other in the circumstances.

We submit that in the case that is presented here, and

under the facts, that the Court should decide that the property

right of the owner of this property is paramount to the right

of petitioners to have their liberty on these premises for the

etlO 330

purpose for which they were present. Thank you.

The Chief Justice: Mr. Perry.

REBUTTAL ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF JAMES RICHARD

PETERSON, ET AL. t PETITIONERS,

BY MATTHEW J. PERRY

Mr. Perryj Mr. Chief Justice, may it please the Court,

Mr. Snyder, in his remarks on yesterday, referred to the inn

keeper doctriner and stated that the innkeeper doctrine was not

applicable in this situation.

We respectfully call to the attention of the Court that

in the City of Greenville, South Carolina, a Negro traveling

through the City of Greenville or in the City of Greenville on

business or for whatever his purpose might be, cannot obtain

a meal on Main Street in the City of Greenville, and this policy

or custom is generated by state lav/, and most especially by the

ordinance which the store manager in this case testified he was

acting upon.

Justice Goldberg: Are there any restaurants in Greenville

v/here a Negro can get meals, do you know, Mr. Perry?

Mr. Perry: There are a few restaurants which cater only

to Negroes.

Justice Goldberg: But not in the main section of town,

is that what you are telling us?

Mr. Perry: That is correct, sir.

Justice Harlan: Under your statute or under your lav/, the

til 331

ordinance is properly in this record, is it not?

Mr. Perry: We contend that ic is, Mr. Justice Harlan and,

as I understood the remarks of Mr. Snyder on yesterday, the

City of Greenville concedes that it is properly before this

Court.

Justice Harlan: And the Supreme Court or Court of Appeals

declined to consider the effect of the ordinance, as I read its

Opinion?

Mr. Perry: That is correct, sir.

Justice Douglas: If a white man went into a Negro restau

rant would he be arrested?

Mr. Perry: There have been many contentions in this particu

lar regard that a white man would be so arrested.

Justice Douglas: Have there been any incidents of that

kind?

Mr. Perry: Not to my knowledge. Not in the whole state

of South Carolina. I believe, of course, as these cases will

demonstrate, the demonstrations in soma of the other cases

involved interracial groups,but none of the demonstrations in

South Carolina which involved, I believe, more than 1200 young

people, involved interracial groups.

Justice Douglas: How many cases are awaiting trial of

this kind?

Mr. Perry: A number of them are still awaiting trial. I

would not hazard a guess as to the exact number, but I think

G tl2 332

that I can answer your question, sir, by stating that more chan

1200 young people were arrested, and this case, of course, was

sec down for hearing.

There are a number of other cases in which petitions for

writs of certiorari are now pending, and a number of cases are

still to ?oc argued before the South Carolina Supreme Court, I

believe, on next week. We have some nine cases set down for

argument in the South Carolina Supreme Court. Some of them

have not yet been tried. They seem to be awaiting the outcome

of this class of litigation before this Court.

Justice Black: I do not quite understand. Do I under

stand you to say it is your belief that this ordinance should

not be against white people who went into a restaurant set

apart for Negroes?

Mr. Perry: Ho, I did not say that.

Justice Black: I did not think you had.

Mr. Perry: Mr. Snyder says here that the ordinance in

this case did not punish the petitioners, but would punish the

manager had che manager sought to serve both whites and Hegroes.

May we answer that by pointing out that the ordinance in

this case was not a mere abstract exhortation to the manager,

but was obligatory in its terms. The manager was left without

a choice, and acted, in asking these petitioners to leave his

premises, according to his testimony, pursuant to the mandate

of the ordinance

et!3 333

Mr. Snyder said on yesterday that textile mills are not

acting in accordance with the state statute which prohibits the

employment of whites and Negroes in the same room at the same

time.

In answer to that, may we point out that the statute is

still in effect on the books in South Carolina, and were we

permitted to go outside the record in this case, we could prove

that the statute is still followed all over the State of South

Carolina. We understand, however, that I may not make such a

comment.

Mr. Snyder pointed out in his remarks on yesterday that

the Greenville Airport in Greenville, South Carolina, is desegre

gated.

May we comment on that in the following manner: the

Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals required the Greenville Airport

Commission to desegregate that airport, and the same counsel

in this case before this Court today were counsel in that case.

Mr. Snyder has alluded to whac he believes to be the

primary issue in this case, namely, whether the proprietor of

a business establishment has the right to select its customers

on the ground of race.

We respectfully say that whatever right of personal choice

a proprietor has to make personal distinctions, the limit of

that privilege certainly seems to be reached when the person

exercising it turns to the state for assistance.

etl4 334

This seems to be what happened in this case. The store

manager, acting not upon his personal choice but upon the man

date or pursuant co the mandate of the City of Greenville and

of the State of South Carolina, in following its broad plan of

keeping the races separated in every area of life in South

Carolina, chose to tell this man to segregate white and Negroes

seeking to eat in the premises of his business.

In Shelley versus Kraemer, this Court said:

"The Constitution confers upon no individual the

right to demand action by the state which results in the

denial of equal protection of the laws to ocher individuals."

We respectfully say to this Court that this is what has

happened in this case, chat whatever right of personal choice

the manager of Kress1 had in this case, he did not use it. He

turned to the state to enforce its, the state's policy of

racial segregation.

Justice Black: Does your argument, chat particular argu

ment, go to this particular point, that if a man goes into an

other man1s property, store, anything, and the man does not

want him there, and he has a perfect legal right to tell him

so, that the state could not protect him in that right by police

officers?

Mr. Perry: Well, Mre Justice Black, may I suggest respect

fully that the record in this case does not show that the manager

did not want -

etl5 335

#3

Justice .black: I am asking you about the argument you

have just made.

Mr* -|3errY : I believe, sir, that the Constitution would

not confer upon him the right to demand of the state action

which would —

Justice Black: Demand? The idea of the law, the right

of the Court co have lav/, is to keep things from being settled

by force and violence, all personal differences settled by

force and violence.

Here is a citizen v/ho has a right under the law, a perfectly

valid right, to do something, that the state can come in and

protect that right with its officers, that has usually been the

case. Are you saying that is not the case?

Mr. Perry: I certainly would not go that far, sir. But

in a case like this one, where the manager of Kress, the Kress

Company has opened its entire premises to the public and has

said to the public, "Come one, come all. We have for sale here

more than 10,000 items. You, white, black, red and yellow, are

invited to come here and purchase."

Justice Black: Then you are denying that they have a

legal right — I understand that argument and I understand the

other one, I think, or I thought I did. But I just wanted to

know if that was your position, that the state is without power

through its police force and its officials to protect people,

people!s rights, on the assumption that they have the rights.

et!6 336

Mr. Perry: I would not go that far, sir.

Thank you very much.

337

The Chief Justice: No. 68, Nathaniel Wright, et al.,

petitioners, versus Georgia.

The Clerk: Counsel are present.

The Chief Justice: Mr. Nabrit.

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF NATHANIEL WRIGHT, ET AL.,

PETITIONERS,

BY JAMES M. NABRIT, III

Mr. Nabrit: Mr. Chief Justice, may it please the Court,

this case is somewhat unlike the si:: cases which have preceded

it this week in that here arrests have been made for conduct

on city property, city park property managed by a city depart

ment, but it is similar to chose other six cases in that here

again the police are engaged in enforcing segregation customs

as if they were an extension of or part of the lav/.

This case is before the Court on writ of certiorari to

the Supreme Court of Georgia brought by six young Negro men

from Savannah who were convicted of the crime of unlawful

assembly under Section 26-5301 of the Georgia Code.

That statute, which appears on page two of our brief,

punishes any two or more persons who assemble, and this is the

key language, "assemble for the purpose of disturbing the public

peace or committing any unlawful act," and fails to disperse

on the command of peace officers, et cetera.

The petitioners were charged under an accusation filed

substantially in the statutory language in assembling at Baffin

ecl8 338

Park in Savannah, Georgia, for the purpose of disturbing the

public peace. No reference was made in the accusation to the

second clause relating to committing any unlawful act, and

petitioners were convicted in the city Court of Savannah by a

jury, and sentenced to fines or to imprisonment in default of

payment of the fines.

On appeal their convictions were affirmed by the Supreme

Court of Georgia.

In the courts below and here we contend the petitioners

have asserted due process claims that they were convicted with

out evidence of their guilt, convicted under a vague statute

which denied them due process.

Nov/, I think it is important to look at the facts in some

detail because of the no evidence claim.

Four witnesses testified at the trial in the state court.

Two of them were, only two of them were, witnesses to the inci

dent which led to the arrest. They were the two arresting

officers.

The other two people who testified were a police sergeant

who came upon the scene after the arrests had been made, and

the head of the City Park Department who was not there at all

and had no contact with petitioners, was not a witness to the

incident, did not know about it until after.

So that the facts I am giving you are the arresting officer's

version of what transpired, and I submit that it demonstrates

339ecl9

completely that petitioners1 guilt is of no criminal act of

any kind.

On January 23, 1961, at about 2 o*clock in the afternoon,

police officers Thompson and Hillis were on duty in Baffin Park,

which is a 50-acre recreational park which, as I have said, is

managed and operated by the City of Savannah. They were in

there apparently —

Justice Black: Owned and operated by the City of Savannah?

Mr„ Nabrit: I understand that is the fact, Your Honor,

and there is no dispute about that. The testimony of the Park

Manager at page, beginning at the bottom of page, 42, indicates

chat he is the Superintendent of the Recreational Department

of the City, and that as superintendent he has overall juris

diction of the playgrounds, aid later on he lists them, and

mentions Daffin Park. There is no explicit statement about

ownership, but I am sure that the city attorneys will confirm it.

Now, Officers Thompson and Hillis were approached by a

person who is identified in the record only as a white lady

and she is, according to Officer Thompson's testimony, supposed

to have told them there were colored people playing basketball

in the park, and Officer Thompson made it clear that as soon as

he heard this, he and his fellow officer proceeded immediately

to che basketball court.

He said, "I did not ask this white lady how old these

people were. As soon as 1 found out these were colored people

et20 340

I immediately went there."

When Officers Hillis and Thompson got to the basketball

court they found the six petitioners playing basketball. Both

officers agreed that that was all chat was going on.

Officer Hillis! testimony at page 50 says, "When I arrived

the defendants were playing basketball. They x;ere not necessarily

creating any disorder* they were just shooting ac the goal*

that is all they were doing, they wasn't disturbing anything."

And Officer Thompson’s testimony at page 41 is the same.

He said in the middle of the page:

"I observed the conduct of these people, when they

were on the basketball court and they were doing nothing

besides playing basketball," and he goes on to say, "They

were just normally playing basketball, and none of the

children from the schools were there at that particular

time."

Justice Black: No what?

Mr. Mabrit: There were no children around.

At an earlier point in his testimony, Mr. Justice Black,

he had mentioned chat there were schools in the neighborhood,

that the schools let out at about 2:30 in the afternoon, and

that at that time the children usually came to this area to play,

but that this was about 2 o'clock.

Justice Black: The City claimed that playing basketball

was against the rules of the City to play basketball in the park?

t2l 341

Mr, Nabrit: Per se, no, sir? no, sir. This facility

was obviously designed for playing basketball.

Justice Black: There was no claim by the City that it

was not available for and used for playing basketball, is that

correct?

Mr.Nabrit: Mo, that is correct. But the City in its

brief in this Court makes an argument about the Park rule, a

claimed argument, that this facility was for children and not

for adults. This was something that was never relied on by

the arresting officer.

Again on page 41 the officer expressly disclaimed any re

liance on this.

At the end of that first paragraph that starts on the page,

Officer Thompson said:

"I have never made previous arrests in Baffin Park

because people played basketball there, I don't have any

knowledge myself if any certain age group is limited to

any particular basketball court, I don't know the rules

of the City Recreational Department."

Officer Thompson —

The Chief Justice: Were any rules presented to the court

in this case, any written rules?

Mr. Nabrit: Mo, Your Honor, there were no written rules.

There was some testimony by the Park Superintendent as to

certain preferences and priorities that he had in his own mind.

et22 342

#4

I submit that these are very vaguely defined and, in part,

contradictory* But the important thing is that there is no

reason at all to think that petitioners had any notice of what

was in the Park Superintendent's mind or any reason to or

opportunity to know about it.

Justice Black: Was there any finding of fact —

Mr. Nabrit: Your Honor, there was a general finding of

guilty.

Justice Black: I am not talking about a breach of the

peace by colored. Was there any general finding of fact that

persons playing basketball in the Park were prohibited by the

City, and applied to everybody in the same way?

Mr. Nabrit: No, there is no indication of anything of

that kind.

Justice Black: No finding of that kind?

Mr. Nabrit: There is only a general finding of guilty by

the jury. There were no court findings in the record.

Justice Black: Was there anything in the charge to the

jury?

Mr. Nabrit: The charge — no, sir. The charge to the jury

contained no discussion of the evidence, no definition of the

offense, beyond a reading of the statute to the jury, and a

statement to them that these police officers were peace officers

within the meaning of the statute. That was the only explanation

of the statute that the jury drew.

343

Nov/, turning again to the scene when the officers arrived,

they proceeded immediately upon arriving to order these peti

tioners to leave the basketball court.

/Vc that point, one petitioner asked the officer, Officer

Thompson, who ordered him to come out here, what his authority

was to come out here and order them off.

Officer Thompson responded he didn't need any authority,

he didn't need any orders.

Another petitioner began to write down the officer's badge

number, and when they didn’t leave in a few minutes they were

all placed under arrest.

Justice Harlan: Was there any physical resistance to the

officers?

Mr. Nabrit: Ho, sir; no indication of that at all. In

fact, the state attempts to make something of the fact that

these — I don't quite understand how this helps the state's

case — but they attempt to argue something from the fact that

petitioners were cooperative with the officers and got in his

car without any urging when they were placed under arrest.

When Officer Thompson testified at the trial he stated

in language that is as clear as day on page 41, that he had a

racial reason for these arrests. Right in the middle of the

page thsre at the beginning of the paragraph he said;

"I arrested these people for playing basketball in

Daffin Park. One reason was because they were Negroes."

344

And everything about his conduct confirms that that was — is

consistent with that reason in that he said that he went immedi

ately to the scene when he found out that colored people were

playing in the Park, and there is additional testimony in the

record that this Park v/as one which customarily had been used

only by white people; that the City of Savannah establishes its

parks in colored and white neighborhood, as such; that the P a r k

Superintendent testified that it was customary co use these

parks separately for the different races at page 45.

Officer Thompson also mentioned another reason which is,

if it means anything, related to race, but is completely un

substantiated ,

He said at another point on page 40 that the purpose of

asking them to leave was to keep down trouble which appeared

to him might start, and he referred to the fact there were five

or six cars driving around the park with white people in them.

And at another place on cross-examination he acknowledged

that these cars were on a driveway which passed the court, the

basketball court, and that this v/as not unusual traffic for

the time of day.

A curious thing about the testimony is that there is nothing

at all to give us any information about the conduct, the demeanor,

of these people in the cars.

There is nothing to even indicate that they observed the

petitioner or the petitioners observed them. There is no

345

indication that they slowed down, that they drove by repeatedly.

There is nothing at all to connect this up as a justification

or substantiation for the officer's expressed, professed fears

that trouble might start.

There was no one else around. There was no one else

present in the area at all.

Justice Black: Is it your contention that the charge v/as

based on such assumption?

Mr. Nabrit: The charge to the jury or the accusation?

Justice Black: Yes,the charge to the jury.

Mr. Nabrit: The charge to the jury which just appears —

Justice Black: I just read it, and I have looked —

Mr. Nabrit: I do not think so.

Justice Black: And they were there, and the officer ordered

them to leave, and they had to leave.

Mr. Nabrit: That is right. That is how I view it, Your

Honor.

But in any event, this is one of the things e::pressed by

the officer during the trial. Beyond this there is nothing.

Beyond this completely unsubstantiated fear of trouble, and his

positive statement, that his other reason was because they were

Negroes, that is the state’s proof.

Justice Black: The statute is broad enough to cover what

was shown to be done here, is it not, because it says "assemble

for the purpose of disturbing the public peace, or committing

346

any lawful act," must move 021 as ordered by a Judge, Justice,

Sheriff, Constable, Coroner, or any other peace officer.

Mr. Nabrit: X do not know whether Your Honor misread that

or not. It is unlawful act.

Justice Black: : I am reading from page 53.

Mr. Nabrit: Committing unlawful act.

Justice Black: It says here "lawful act." It is probably

a misprint.

Mr. Nabrit: You are reading from the Judge's charge.

Justice Black: Page 63.

Mr. Nabrit: That is a misquotation of the statute as it

appears in the Code. Whether that represents what he said to

the jury or not, Your Honor, I do not know. We have no we

only have the court reporter's certificate.

Justice Black: Under the statute it is assemble for the

purpose of disturbing the public peace or committing any unlawful

act.

Mr. Nabrit: That is correct. The correct statute appears

at page 2 of our brief.

Justice Black: I wonder if in his charge to the jury he

charged "committing an unlawful act"?

Mr. Nabrit: Well, I do not believe that he charged them

anything. And I point out again, as I attempted to earlier,

that the accusation itself never relied on chat part of the

statute, "committing any unlawful act."

et27 347

#5

This is something which the court below also observed

when it, in its Opinion, it said, "The only thing involved was

the phrase 'disturbing the public peace6 or 'for the purpose of

disturbing the public peace.1"

In answer to Youa: Honor’s original question about whether

this statute covered this conduct, I state that this statute

is probably so vague and indefinite that it could cover almost

any type of lawful conduct.

This statute has been authoritatively construed by the

Georgia Court of Appeals to cover acts which I consider beyond

the common law meaning of this type, to go beyond the common

lav; concept of unlawful assembly, and the only appellate decision

construing this statute in a prosecution of it, State against

Samuels, this statute was applied to sit-in demonstrators on

facts substantially the same as those in two of the cases in

Garner against Louisiana.

These were people who had not been ordered out of the

store by any proprietor, people who were there at the sufferance

of the proprietor, ordered out by a police officer, and that,

in that Opinion, it seems to me evident, that the court took

this statute beyond any common law concept of disturbing the

peace, and applied it to the area of liberty protected by the

due process clause.

Justice Goldberg: Mr. Nabrit, let me see if I understand

what you are saying. Are you saying that this statute, which

et28 348

is a fairly common statute, isn't of this type, on its face

is vague —

Mr. Nabrit: I am arguing —

Justice Goldberg: (continuing) — or are you saying there

wasn't evidence to warrant a conviction under the statute?

Mr. Nabrit: I am making both of those arguments, and a

third argument which I have not expressed yet, that the statute

did not give them fair warning that their particular acts were

prohibited.

Justice Goldberg: What was argued in the Georgia Court as

the Federal basis for relief in the Supreme Court?

Mr. Nabrit: Yes, sir.

Justice Goldberg: Would you, in the course of your argu

ment, point out which of these was directed to the Georgia

Supreme Court?

Mr. Nabrit: Your Honor has, perhaps, observed that the

Georgia Supreme Court's Opinion does not at all discuss the

facts.

Justice Goldberg: That is correct.

Mro Nabrit: And this is a curious thing which has undoubtedly

attracted the attention of the Court.

It is our contention that the no evidence issue, the vague

ness, and the vagueness of the statute in all of the applica

tions of that term, were properly argued and preserved at every

stage of the proceeding in the state court.

ec29 349

The due process vagueness question was first raised in a

demurrer. It was again raised in a motion for a new trial, as

was the claim chat there was no evidence upon which the defendants

could be convicted.

The assignments of error contended that the court did err

in overruling that motion for a nev; trial which embodied a no

evidence claim and due process vagueness claim.

Justice Goldberg: Was the no evidence claim buttressed

upon the Federal Constitution?

Mr. Nabrit: The no evidence claim — I think it is inherently

a federal issue. Your Honor. It appears at page 17 of the

record. There were six identical motions for a new trial.

This was the first one, and paragraph one says chat the verdict

is contrary to evidence and without evidence to support it.

There was no particular reference at that point to the

due process clause, but I believe that Thompson against the

City of Louisville stands for the proposition that a conviction

without evidence is inherently a due process matter.

Justice Goldberg: Does it stand for the proposition that

an allegation of this type or a complaint of this type is suffi

cient to direct the attention of che Court to the Federal

question involved?

Mr. Nabrit: Well, I don’t believe that Thompson indicates

anything on that one way or another. However, I submit that

this Court, the Georgia Supreme Court's attention was directed

et30 350

to the problem which you are attempting to raise here, and I

will try to tell you why.

The basis upon which the Georgia Supreme Court determined

apparently not to consider the evidence was the theory that the

petitioners, defendants there, had impliedly abandoned their

claim that there was error in overruling the motion for a new

trial by their brief in the Georgia Supreme Court.

When the record and the petition for certiorari were filed

here, certified copies of all of those briefs were deposited

with the Clerk here, so they are available for the Court to

inspect.

Now, we submit that chat brief on behalf of these petitioners,

filed in the court below, while it did not say in the section-

labeled ’'Argument", while there was no subsection saying, "We

are now arguing our motion for a new trial," nevertheless, did

argue these due process issues and that it did argue the facts

of the case, it did argue that petitioners were convicted for

innocent acts. It did argue that the officers’ conduct was

arbitrary and capricious.

There was a long quote from language in the Yick Wo case

about arbitrary application of statutes, and I might point out

that when the Court decided Thompson against Louisville, it

cited in support of the holding that a conviction without

evidence was a denial of due process, and one of the cases that

was cited was Yick Wo.

et31 351

Justice Harlan: Had Thompson been decided at the time

this brief in the state court had been written?

Mr. Nabrit: I am inclined to think that it was. I do not

know the respective dates off hand, Your Honor. But 1 know

that the date of decision in the State Supreme Court was

November a year ago.

Justice Harlan: November '61?.

Mr. Nabrit: Yes. But 1 have no knowledge as to when the

briefs were filed. The copies deposited with the Clerk may

very well indicate that.

I would like to reserve —

Justice Harlan: Was Thompson cited in that brief?

Mr. Nabrit: 1 believe not, Your Honor.

I would like to reserve the balance of my time.

The Chief Justice: You may.

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF STATE OF GEORGIA,

RESPONDENT.

BY MR. SYLVAN A. GARFUNKEL

Mr. Garfunkel: Mr. Chief Justice and Associate Justices,

I should like to state at the beginning that the State of

Georgia — and we are not city attorneys, we are the District

Attorneys office, they call us solicitors general, and I am

Chief Assistant Solicitor General in the Circuit, which is

Savannah — we admit this was a city operated park.

We further admit that it would be unconstitutional to

352

practice segregation in such a park.

We further admit and feel that if this statute was being

used in a manner to preserve segregation in this park as a

subterfuge to preserve segregation, then under the facts in this

case this case should be reversed and sent back and the defendants

acquitted.

However, we ask the Court to look at the record in this

case and study the facts that were developed.

As I heard argument yesterday —

The Chief Justice: Are those issues before us to determine?

Mr. Garfunkel: Yes, sir. That is what I was coming to now.

The Chief Justice: Yes.

Mr. Garfunkel: As I heard the arguments yesterday, the

Court several times referred to the question of what was the

policy and, as Mr. Nabrit referred to the Pari; Superintendent

having testified in the development of this case on cross-

examination, it was understood that the Court was being told

that these people were being arrested because of being Negroes.

We, therefore, put the Park Superintendent on the stand to

outline for the jury and the court below and the Court of

Appeals and before this Court to understand the policy of the

park, park playgrounds, in Savannah, and I, therefore, would

like to refer the Court to page 42 of the record, which is the

testimony of the playground superintendent, in which he outlined

the way the park3 were set up in Savannah.

et33

#6

353

He said he tried to put them in areas, in white areas and

in colored areas, although v/e have several which are now in

mixed areas, Park Extension and Wells Park because in certain

areas they play together.

He says it has occurred from time to time that colored

children would play in the Daffin Park area and in the Park

Extension area, but no action has been taken because it is

legal, it is allowed and nobody has said anything about it.

That is in the middle of page 43 of the record.

Justice Douglas: This is Mr. Hager?

Mr. Garfunkel: This is Mr. Hager, the Park Superintendent.

He said then further on at the bottom of the page:

"The playground areas" — in further explanation —

"the playground areas are basically for young children,

say 15 through 15 and under, along that age group, v/e

give priority to the playground to the younger children

over the grownups, it made no difference as to whether

they were white or colored."

He continued:

"Any time that v/e requested anyone to do something and

they refused we would ask the police to scop" — - that is

a misprint, it should be "step in, if we would ask them

to leave and they did not v/e would ask the police to step

in. We have had reports that colored children have played

in the Park Extension, but they were never arrested or told

to leave."

He further referred earlier, of course, to the fact that

they had played in the Daffin Park area and had not been

arrested.

The facts in this case show that these defendants were

grown wen, the youngest of which was 23 years of age, and

the oldest of which was 32 years of age; that they went upon

this playground around 1:30 or 2 o'clock in the afternoon during

a school day.

At that time they were dressed not for playing basketball

but dressed more for business purposes, that is, they had on

hard shoes, they had on shirts, jackets, and I think some of

them might even have had ties on, I am not sure. The police

officer —

The Chief Justice: Is that against the rules?

Mr* Garfunkel: Ho, sir; but it was to go into the question

of the bona fide., the purpose of the question of intent, that

came into the intent, because the defendants constantly said

they were just merely there for the purpose of playing basket

ball, and we said the intent v/as not to play basketball, and

although they denied this all the way down up to this Court in

their brief in this Court, they say that, perhaps, it v/as not

to play basketball but to make a profound non-verbal expression

against segregation in public parks. That is the way they put

it in order to come into the question of free speech.

355

Now, however, Mr. Hager further on in his testimony said,

he further testified that, if there were a conflict between

the younger people and the older people using the park facilities

the preference would be for the younger people to use them.

"But we have no objection to older people using the facilities

if there are no younger peop.le present or if they are not

scheduled to be used by the younger peop.le."

He said, and this is on further direct examination:

"It has been the custom to use the parks separately

for the different races. I couldn't say whether or not a

permit would or would not be issued to a person of color

if that person came to the office of the Recreational

Department and requested a permit to play on the courts,

but I am of the opinion that it would have been, we have

never refused one, the request never has been made."

In other words, he said if they came "we would grant them,"

but nobody has ever come and "asked us, so I can11 say we have

done it because nobody has requested it."

Justice Harlan: What does the record show as to whether

there were younger people who wanted to play basketball?

Mr. Garfunkel: I am coming to that right now, Your Honor.

Further, I would like to go on to Mr, Hager's point and

then I will come back to the actual facts.

Cn school days, and this was a school day, these courts

and the playground area are at Baffin Park available only for

356

certain age groups, and they are only used at that time of day

by the schools in that vicinity.

It is more or less left available for them. That is the

way we have our recreation set up.

In other words, at this time, this park, this playground,

was reserved, and the evidence shows there v/e re two schools right

across the street, it was reserved for the use of these schools,

and he further said all during the day these people came from

various schools to play, not just recess, but they had physical

education activities in which they would come out and play on

this playground, and all during the day, even though at that

particular moment they might not be there, they momentarily

might come in the next five minutes, and the policemen knew

definitely that the school would be out at 2:30, and at that

time he knew the children would be coming across to play on

the playground, and this was — and this policeman so testified

in court that he knew these children would come.

Justice Black: Were there indications of this kind sub

mitted before the jury?

Mr. Garfunkel: Yes, sir. This is all evidence.

Justice Black: I am not talking about evidence. Did the

Court charge the jury on the issues?

Mr. Garfunkel: Mr. Justice 31ack, in the Georgia pro

cedure we have what is locally known as che dumb act, and that

is the judge is not able to comment on the evidence. He cannot

et37 357

comment one way or the other on the evidence. He merely charges

the jury on the lav;.

Justice Black: That is what he said, "I am now charging

you fully on the lav;." But he charged on the lav; as well as

some rules that they had that these people had violated —

Mr. Garfunkel: Well, the rule —

Justice Black: (continuing) — a practice of custom?

Mr. Garfunkel: They had violated — what he charged them

was they had violated the order of the police officer.

Justice Black: Order of the police officer?

Mr. Garfunkel: That is right.

Justice Black: But is it the law, as you understand it,

in Georgia that a man charged with the offense of doing some

thing that is unlawful and a police officer thereafter orders

him to leave, that when he is tried they do not submit any

issue except and other chan as to whether he had to move when

an officer told him?

Mr. Garfunkel: It is only a general verdict.

Justice Black: I understand the general verdict. But does

the state have to prove its case?

Mr. Garfunkel: The state attempted to prove its case.

Justice Black: Is it part of its case, what you have been

arguing to us here, that these people were violating the rules

in that they were playing at the time that children should play?

Mr,. Garfunkel: No, The Court did not go into detail as

358

to violation of the rule.

Justice Black: He did not even mention it, did he?

Mr. Garfunkel: Ho, he did not. He mentioned only that

they would be charged with going on for the purpose — and

there was a question of whether this v/as an intent co disturb

the peace? all this was taken into consideration.

Justice Black: Maybe it does not affect the argument you

are making here, but so far as the charges concerned, nothing

like this was contained in the charge?

Mr. Garfunkel: Of the trial judge?

Justice Black: He is supposed to charge what the law is

and what they violated.

Mr. Garfunkel: The usual trial, the judges in the courts

below, the Georgia Courts —

Justice Black: He didn’t charge them what would be — on

what they would have to pass as being lawful or unlawful except,

as you say, they disobeyed a policeman.

Mr. Garfunkel: They were not charged with doing something

unlawful, Your Honor. They were charged with going on the play

ground for the purpose of disturbing the peace.

Justice Black: Disturbing the peace or some other unlawful

acto

Mr. Garfunkel: Ho, sir? disturbing the peace.

Justice Black: Disturbing the peace, Did he charge them

as to what amounted to a disturbance of the peace?

et39 359

Mr* Garfunkel: Wot in detail, Your Honor.

Justice Black: Did he charge them ac all?

Mr. Garfunkel: He charged them — and I will have to get

his charge, sir.

Justice Black: It would not disturb the peace, \;ouid it,

if they were there not violating any rules, not violating any

rules of the city?

Mr. Garfunkel: Not genericallv. This is the case, this

is the statute, and the way we are arguing to the Court.

The statute becomes violated not by disturbing the peace

but by two or more people assembling for the purpose of dis

turbing the peace, not that the purposes of die peace have to

be disturbed.

Justice Black: They wouldn't have been determined to have

disturbed the peace, would they, if they attempted to do a

lawful act on the park?

Mr. Garfunkel: But it became unlawful when they refused

to obey the police officer's request to leave.

Justice Black: We finally get back to the fact you are

saying that under your Georgia statute the policeman has the

complete power, and one of their contentions was, 7. believe,

that this vests them with arbitrary power, they have complete

power to determine whether they have already done something

for the purpose of violating the peace.

Mr. Garfunkel: Then it is up to the jury to so determine,

360

and the j udge *

Justice Black: Yes, if they are charged with what would

he their —

Mr. Garfunkel: If they thought the policeman was correct.

That question has not been raised very much, but there is a case

that is very interesting, from the Court of Appeals of Hew York,

People versus Galpin, and in that case, one in a million case,

Mr. I. Sylvan Galpin was a member of the Bar of New York, and

the reference is made in my brief and I won't give you the

citation, and he had come out of a restaurant and was standing

on the sidewalk talking to some friends of his, and a policeman

came along and said, "Would you please move," and he said, "I

don't have to move. I am on the public sidewalk," and the

policeman arrested him for, under a somewhat similar statute

in the State of New York.

He was convicted. This went all the way up to the Court

of Appeals in New York, and they were faced with a somewhat

similar situation because there he says he was validly on the

sidewalk and the Court said that the policeman had a right to

believe that he might block the sidewalk, and if the policeman

felt in his mind and he bona fide made a request in his mind that

there was that chance, that refusing to obey the police officer

at that time could very well be and was a disturbance of the

peace for which a jury or a judge sitting as jury could convict,

and they affirmed his conviction.

361

The record showed that there was no disorder, it was all

talk, very friendly„ There were no harsh words or anything

else, just a request made by a policeman.

Justice Black: I understand your citation of that case

as a justification of what was done, because there- maybe the

way the jury was charged, I think that was the only thing per

mitted to them. Did the policeman order them to go away and

did they stay? I see no other issue except chat, and that case

which you referred to may be wholly irrelevant on that issue.

Mr. Garfunkel: And then we have the further question of

the Supreme Court of Georgia construing a statute in which, I

think, this Court held in Garner versus Louisiana, that it was

up to the highest court to construe the meaning of its own

statute and when it was violated.

The question that I see to be presented to this Court

would be twofold: first, was this statute used as a vehicle to

preserve segregation and, second, was there any evidence what

soever to justify the police officer to believe that a breach

of the peace was imminent or might happen to cause him to ask

them to leave. Was he in a bona fide manner asking them to leave.

Justice Goldberg: General, what in this record would

lead the police officer to believe that?

Mr. Garfunkel: That is what I was coming to.

Justice Goldberg: Were you coming to that?

Mr. Garfunkel: I am glad, Mr. Justice Goldberg, you

et42 362

brought that up. because there are several issues.

First, that these children were there, they were coming,

and he expected them there. Ee testified, Officer Killis

testified, and that is in the record or rather, Officer Thompson,

1 believe —

Justice Goldberg: 41.

Mr. Garfunkel: Right.

Justice Goldberg: He said he made these arrests around

2 o'clock, and the schools let cut around 2:30, and it would

have been at least 30 minutes before any children would have

been in this particular area.

Mr. Garfunkel: That is true. But, Your Honor, at what

point would it be necessary for him to tell them to leave this

playground? Under the rules of the. Playground Commission, the

playground was available for these school children all during

the day.

Justice Goldberg: But that is not what the Superintendent

said precisely. You read part of it. Did he not also say on

page 48:

"If that basketball court was not scheduled it would

be compatible with our program for them to use ic, and

we would not mind them using it*"

And didn1t he further say on page 47:

"I dont know whether or not w e had a planned program

arranged for the day that these arrests were made, I would

have to check my records."

Mr. Garfunkel: But earlier, above that, Your Honor, he

said, and this was in answer to a hypothetical question, and

this is tha total question and answer:

"If your planned program did not have the 23rd of

January, 1961 set aside for any particular activity

would it have been permissible to use this basketball

court in Daffin Park in the absence of children?"

And his answer said:

"I can:t very well answer that question because you

have several questions in one. First, 1 would like to

say that normally we would not schedule anything for that

time of the day because of the schools using the totals

area there," so at that time it was reserved, according to

the first part of his testimony.

Then, in going to try to help the answer in this hypothetical

question, he said:

"If we had not had something scheduled at that time

' of day then we would have granted them permission. But

at that time the total area was reserved for the school

children."

The Chief Justice: Whose witness was this man?

Mr. Garfunkel: This man was the state's witness, when

the defense started to develop the fact that they were arrested

solely because of the fact they were Negroes.

et44 364

The Chief Justice: Aren't you bound by his cross-examina

tion?

Mr. Garfunkel: Yes, sir. Eut this was — what Mr. Justice

Goldberg asked me was, he quoted the first part, I should say

he quoted the last part, and this was the first part of the

same answer chat he was asked. In other words, this answer goes

on for almost half a page, and he said at first at that time of

day this playground was reserved for the schools.

Then, in going along further he said, "You have asked me

several questions in one. If they had not been reserved," he

said, "if that basketball court was not scheduled ic would be

compatible with our program for them to use it, and we would

not mind them using it. If there was a permit issued there

would be no objections as to race, creed or color." In ocher

words, that is the last part of the answer.

The Chief Justice: Then he also said, didn’t he, that

he didn’t know whether there was anything scheduled or not?

Didn1t he?

Mr. Garfunkel: He says, "We never know when they are

coming," in one part? that is, the parochial schools use it

during recess and lunch periods and also for sport? and also

the Lutheran schools and the public schools bring their school

children out there by bus, and at various times during school

hours all day long. He said*"We never know when they are

coming, and they use Cann Park the same way, I might add."

et45 365

Cann Park is a park area in the colored section, and I

think what the interpretation of his answer is, that he per

sonally does not know if the schools are going to bring some

body around at 10 o'clock or 12 o'clock or 1 o'clock, but as

far as the playground, as far as the playground department is

concerned, those playgrounds are exclusively for the use of

the schools during those hours for whenever they want to use it.

#8 Justice Goldberg: But this was not embodied in any regula

tion known to anybody, is that correct, General, because as I

read his testimony on page 46 he says there is no regulation

for playing on a court when it is not in use, and there is no

one around.,

Mr. Garfunkel: That is correct,sir. There was no printed

regulations, and there was no — but we state this, sir, Mr.

Justice Goldberg, that the going, merely going, upon the park

grounds and playing the basketball is not criminal, and if

they had walked up, the policeman had walked up to him and

said, “I am arresting you, we are going to charge you with a

misdemeanor," there is a basic unfairness in such a statute,

because obviously no one would know that he had violated or was

violating something.

But it becomes, the fairness in this is, that it does not

become a misdemeanor until he is asked to leave and refuses to

leave, and asked to leave by a peace officer, who is a policeman,

a police officer wearing a uniform.

et46 366

Justice Goldberg: So is your contention, in substance,

this, there being no regulation against the use when ic is

not being used by anybody else, there being no children evident

in the vicinity since they were not out of school until 2:30,

that it becomes a disturbance of the peace if a group of men

are there, using an empty court, it becomes a disturbance of

the peace if you do not obey a police officer when he says,

"While you are here legally and properly and not against any

regulation, I tell you now to move on," is that a disturbance

of the peace?

Mr. Garfunkel: The police officer did not actually tell

them, "While you are here legally and properly."

Justice Goldberg: But 1 mean the superintendent said

they were there legally and properly.

Mr. Garfunkel: Mo. I think the superintendent said if

they had not been scheduled. But at that time of day they

would not have been allowed.

Justice Goldberg: DidnJt we both agree a moment ago that

there is no regulation for playing on a court when it is not

in use and there is no one around?

Mr. Garfunkel: There is no printed regulation, but there

is a regulation of the park. I mean, that is the way they

regulate the parks. If you put it, chat is the way the park

superintendent regulates the park. If they had printed — if

you are saying are there printed regulations that are posted

367

and all of that, I would say, no. But there is this regulation

in the sense that chat is the way the parks are run.

Justice Goldberg: General, then would you define what

constituted the disturbance of the peace under the circumstances.

Mr. Garfunkel: Yes, sir. The disturbance of the peace

under the circumstances, Your Honor, was that they had gone

there, we feel, and 1 think the record shows, because they

went there to what they thought was to test segregation.

The police officer —

Justice Goldberg: Is that illegal?

Mr*. Garfunkel: Ho, sir? it is not illegal. But the

police officer said, "On other occasions I have seen colored

children in Daffin Park and I have not arrested them0 But in

these circumstances I did."

I think what we are faced with is the police officer was

exercising a question of judgment. Did he bona fide feel that

there could be a disturbance of the peace, not that they were

disturbing the peace, but by their actions cause others to

disturb the peace.

Justice Harlan: - Could I put this question to you?

Mr. Garfunkel: Yes, sir,

Justice Harlan: Taking this question as you say it

should be taken, namely, that the offense is disobeying a

proper action of — a proper request of a police officer, what

do you do about the sta tement that seems to be undisputed that

et48 368

r

the arresting officer himself said that one of the considerations

that led to the command was that this man was a Negro?

Mr. Garfunkel: Yes, sir.

Justice Harlan: Is that a valid Constitutional consideration?

Mr. Garfunkel: If that was the overriding consideration

for the man's arrest, I would say that this case should be

reversed*

Justice Harlan: And you do not get to any question of

the sufficiency of the evidence or anything else, do you, on

that premise?

Mr. Garfunkel: The question —

Justice Harlan: I wish you would deal with that point.

Mr. Garfunkel: The question presented by and in the briefs,

the question presented by the petitioners and the way the

question is presented by the respondent, expressly states that

because in our brief we have put the question in this manner.

We feel that the evidence shows this:

"Whether the conviction of petitioners for unlawful

assembly denied them due process of lav/ under the 14th

Amendment when they were convicted on evidence which showed

that they were grown Negro men who took over a playground

in a predominantly white neighborhood at a time when the

playground was reserved for and was to be used by school

children and they refused to leave when requested by the

police."

et49 369

Now, the reason he said he asked them to leave was because

he expected the children.

Now, he said he knew the children would be there by 2:30.

He knew they were going to be there by 2:30. They could have

come earlier. He asked them to leave. Nov; here we are in a

predominantly white area —

Justice Black: What does that mean?

Mr. Garfunkel: Your Honor, because he asked the question,

he said they asked on cross-examination was one of the reasons

"you arrested them was because they were Negroes," and he said,

"Partly one of the reasons was." But the overriding reason.

Justice Black. Why should we include that in your question

there unless it was based on color, "in a predominantly white

neighborhood?"

Mr. Garfunkel: Because the evidence showed it was in a

predominantly white area.

Justice Black: Why?

Mr. Garfunkel: Because he felt —

Justice Black: The law is all right if you provided parks

located in a predominantly white neighborhood, that people

should be excluded because of their color?

Mr„ Garfunkel: No.

Justice Black: What does chat have to do with it?

Mr. Garfunkel: Because the question was asked the police

officer, and that was asked on cross-examination. He said if

370

these were white adult men they still would have to he asked

to leave. But the fact that they were Negroes added to the

fear of the police officer that here they were on a playground

that was at that time reserved for these children, and the

park superintendent said, "We keep them separate as to groups

because it is not gocsfl park policy to have grown people on a

playground which is reserved for children."

He said, "We donct want it" and that is in the record.

Here were these people who, if they had been adult white men,

would still have been requested to leave.

But the question on cross-examination was asked, and he

said, "That was part of the reason, wasn't it?" He said,

"Partly."

Of course, in the policeman's eyes, it is a fact, and I

cannot deny the fact that they were on this because there was

a further chance of a disturbance of the peace — and they

were asked to leave, there would be a disturbance of the peace,

the fact they were Negro. And that is not the overriding con

sideration.

Justice Black: Bo you think everyone on the grounds would

have been excluded?

Mr. Garfunkel: Which ones?

Justice Black: The ones who were colored, and that this

park was predominantly white?

Mr. Garfunkel: No, sir. That was not the overriding —

et51 371

that would not have been sufficient, and if that was the over

riding reason, and if it was, this case should be reversed.

But the overriding reason — the fact they were colored, had

nothing to do

Justice Black: Suppose it was one of the reasons. Would

that make any difference?

Mr. Garfunkel: Well now, we feel if the fact that one

of the reasons the police officer says, if there is a legitimate

reason for reversal, if there is a legitimate reason for a

police officer to ask them to leave without regard to color,

the fact that color might incidentally be a part of it, should

not say that you would not be guilty.

For instance, suppose white adult men went on the play

ground and they asked him to leave, and this case came up on

the record of the same type, they went there and played in the

same way, then would the fact that these people were white,

would that mean that they should be acquitted when colored in

the same category would be convicted — when colored in the

same category would be acquitted?

The Chief Justice: If these people had been white people,

would you have put in your question, as you read it to us, the

fact that this was in a predominantly white neighborhood?

Mr. Garfunkel: No, sir? I would not. The only reason I

mentioned that was because in the record it shows on cross-

examination, in answer to one of the defense attorney's question

372

was one of the reasons you asked, “That you arrested them

because they were Negro or did you arrest them because they were

Negro," and in response to the question it was, "Yes", and that

is why it was put in the question because it had been put into

the case by the defense counsel.

The Chief Justice: Why do you say chat the predominant

reason for the arrest was ocher than because they were Negroes?

Mr. Garfunkel: Because the facts that the State proved

showed that colored children had played in that park other

times and had never been arrested.

The undisputed testimony of the Park Superintendent was

that they had a right to play and it was legal? that the Park

Superintendent was aware of the fact that colored children had

played in that Park and had not been arrested.

The arresting officer himself testified that he had seen

colored children playing in that Park, and they had not been

arrested.

So that in this instance, I would say, one swallow wouldn!t

make a summer, one arrest of these people does not show a pro

gram of segregation, but this feeling that this would be a

legitimate area of inquiry by this Court and by any of the

higher appellate courts, the State showed by putting it in that

this was not the reason because af it were the reason, if this

were the true reason, then it also would have been applicable

to all of the other instances, and they should have been arrested

et53 373

to sho.7 that .

The Chief Justice: Then to the extent that he was motivated

by the fact that they were Negroes, the arrest would be illegal.

Mr. Garfunkel: If that was the sole, if that was the

proper or overriding reason, and by that I mean if that was his

motivating reason —

The Chief Justice: You say the other is the overriding

reason. I understood Mr. Nabrit to say that one of these

officers testified that he didn't know anything about the rules,

didn't knew if they had any rules, didn't know what they were

and, in effect, he didn't arrest them because of a violation of

the rules.

Mr. Garfunkel: He arrested them, he said —

The Chief Justice: Is that true?

Mr. Garfunkel: That is correct in this respect that he

didn't know about the rules of the park, but he did know of

the fact that the cli ldren would be there. He knew this every

day. He rides this beat, and he knew every day that children

played in the park during the recess, as he put it, during the

physical education period.

The Chief Justice: But he didn't know there were any

rules about anybody else being there.

Mr. Garfunkel? No, sir? he knew chat park was reserved

for the children.

The Chief Justice: Where does he say chat?

374

Mr. Garfunkel: He says, "I knew that within a half hour"

— Officer Hillis or Officer Thompson —

Justice Goldberg: 4l.

Mr. Garfunkel: "Under ordinary circumstances I would not

arrest boys for playing basketball in a public park. I made

these arrests around 2 o'clock; and the schools let out around

2:30 o'clock, and it would have been at least 30 minutes before

any children" — that \/as on cross-examination — "the children

from the schools" — this is page 40, the middle of the page —

"children from the schools would have been out there shortly

after that. The purpose of asking them to leave was to keep

down trouble, which looked like to me might start."

And up at the top, "There is a school nearby this basket

ball court, ;.c is located at Washington Avenue and Bee Road,

I mean at Washington Avenue and Waters." This is just across

the street.

"There is another school on 44th Street — there are two

schools nearby; I believe they are both 'grammar' schools. I

patrol that area and the children from these schools play there,

they come there every day I believe, I believe they come there

every afternoon when they get out of school, and I believe they

come there during recess."

The Chief Justice: But he also said, "I don't have any

knowledge myself if any certain age group is limited to any

particular basketball court. I don't know the rules of the

375

City Recreational Department."

Mr*. Garfunkel: That is right, sir.

The Chief Justice: And still he arrested them presumably

for violation of those rules, plus the fact they were Negroes»

Mr. Garfunkel: No, sir. He arrested them for failing to

leave when he made this request, Your Honor.

The Chief Justice: But if they weren!t doing anything

illegal, and they were doing something they had no knowledge of,

did they have any right to ask them to move along — did he

have the right as a police officer just to move them along?

Mr. Garfunkel: That is the main issue, as v/e see it, in

this case.

The Chief Justice: Well, does he have chat right as a

police officer?

Mr. Garfunkel: We believe as a police officer he has

the right to ascertain from the facts that he can tell from

what is happening to determine whether he should make the

request to leave; chat is a question of judgment. That there

might be a question of whether, if you or I or someone else

was there, whether we think v/e should have asked them to leave.

But when a police office, acting on the best available

evidence in the way he observes it, makes this request to leave,

if there is any evidence whatsoever to sustain him to show chat

this was a bona fide request, that he was trying to keep down

trouble in the parks, then that should be obeyed, and he would

et56 376

for failure to obey it, be in a position of where you are

doing it at your peril. You might be right or you might be

wrong.

in other words, you say. "I didnct leave and I was right,"

just like sometimes a man says, "Go ahead and violate that law,

it is unconstitutional," you violate it at your peril.

The Chief Justice: But if these people -- that is true —

but if these people were doing nothing out of the way, which

he said, he said they were just playing there and doing nothing

else, and if that is true, and if it is true that he had no

knowledge of a violation of any rules of the park, what is

there in this case to indicate that these people were doing

something unlawful for which they could be moved along by a