Shipp v TN Department of Employment Security Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

March 7, 1977

131 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Shipp v TN Department of Employment Security Brief for Appellants, 1977. 95ddfc35-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0c3c3b78-751f-4920-a0fd-d13942515518/shipp-v-tn-department-of-employment-security-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

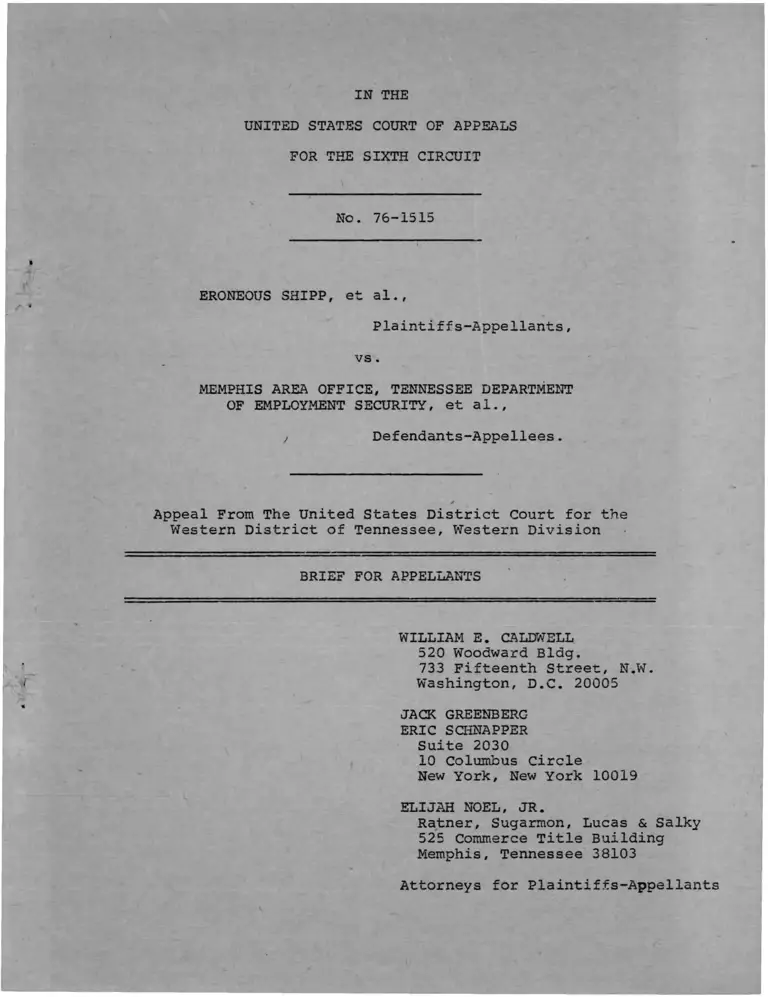

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

No. 76-1515

ERONEOUS SHIPP, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

MEMPHIS AREA OFFICE, TENNESSEE DEPARTMENT

OF EMPLOYMENT SECURITY, et al.,

y Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal From The United States District Court for the

Western District of Tennessee, Western Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

WILLIAM E. CALDWELL

520 Woodward Bldg.

733 Fifteenth Street:, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

JACK GREENBERG

ERIC SCHNAPPER

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

ELIJAH NOEL, JR.

Ratner, Sugarmon, Lucas & Salky

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

INDEX

Questions Presented ................................. 1

Statement of the Case ............................... 3

Summary of Argument ................................ 7

ARGUMENT ............................................ 10

I. The Defendants Engaged In Unlawful

Discrimination In Their Treatment

of Applicants for Referrals, Placement,

and Other Services ...................... 10

(1) Plaintiff's Prima Facie Case ...... 11

(2) The Evidence in Rebuttal .......... 36

(3) The Opinion of the District Court .. 49

II. The Defendants Engaged In Unlawful

Discrimination In The Hiring and

Promotion of Employees At The

Memphis Area Office of TDES ............. 53

III. The District Court Erred In Failing

To Direct The Defendants To Take

Effective Action To Discover, And

Withhold Service From, Employers Which

Engage In Racial Discrimination ........ 78

IV. The District Court Erred in Dismissing

Plaintiff's Individual Claim ............ 86

(1) The Absence of Specific Findings ... 86

(2) The Class-wide Discrimination ..... 93

CONCLUSION .......................................... 95

Page

-l-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Page

Adams v. Richardson, 480 F.2d 1159 (D.C. Cir.

1973) ............................................ 85

Afro-American Patrolmen's League v. Davis, 503

F .2d 296 (6th Cir. 1974) ................ 30, 31, 59, 64, 74

Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody, 432 U.S.

40 5 (19 7 5) ....................................... 50 , 61, 69, 76

Bridgeport Guardians v. Members of Bridgeport

Civil Service Commission, 482 F.2d 1333

(2d Cir. 1973) ................................... 59

Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co.,

457 F .2d 1377 (4th Cir. 1972) ................... 36

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir.

1971) ............................................ 36

Causey v. Ford Motor Co., 516 F.2d 416

(5th Cir. 1975) .................................. 52

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Flaherty, 11 EPD

fl 10,624 (W.D. Pa. 1975) ........................ 66

Douglas v. Hampton, 512 F.2d 976 (D.C. Cir. 1975) .. 74

E.E.O.C. v. Detroit Edison Co., 515 F.2d 306

(6th Cir. 1975) .................................. 34, 35, 64

Franklin v. Troxel Manufacturing Co., 501 F.2d

1013 (6th Cir. 1974) ............................ 10, 49, 94

Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285

(1969) ........................................... 47

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968) .............................. 25

Griggs v. Duke Power Company, 401 U.S. 424 (1971) .. 46, 50, 61,

74, 76

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co., 491

F .2d 1370 (5th Cir. 1974) ....................... 66

-ii-

92

63

92

94

35

47

69

51

66

31

55

35

74

67

92

59

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, 421 U.S.

454 (1975) .......................................

League of United Latin American Citizens v.

City of Santa Ana, 11 EPD f 10,818

(C.D. Cal. 1976) .................................

McClanahan v. Mathews. 440 F.2d 320

(6th Cir. 1971) ..................................

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792

(1973) ...........................................

Meadows v. Ford Motor Co., 510 F.2d 939

(6th Cir. 1975) ..................................

Northcross v. Board of Education of Memphis

City Schools, 466 F.2d 890 (6th Cir. 1972) .....

Officers for Justice v. Civil Service

Commission, 11 EPD 5 10,618 (N.D. Cal. 1975) ....

Palmer v. General Mill, Inc., 513 F.2d 1023

(6th Cir. 1975) ..................................

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co.,

494 F .2d 211 (5th Cir. 1974) ....................

Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457 F.2d 348

(5th Cir. 1972) ..................................

Rolfe v. County Board of Education, 391 F.2d 77

(6th Cir. 1968) ..................................

Senter v. General Motors Co., 11 EPD «[ 10,741

(6th Cir. 1976) ................. ................

Sims v. Sheet Metal Workers, 489 F.2d 1023

(6th Cir. 1973) ........................ 28, 51, 53,

Stamps v. Detroit Edison Co., 365 F.Supp. 87

(S.D. Mich. 1973) ................................

United States v. Claycraft Co., 408 F.2d 366

(6th Cir. 1969) ..................................

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d

906 (5th Cir. 1973) ..............................

-in-

Page

United States v. Hazlewood School District,

11 EPD 5 10,854 (8th Cir. 1976) ................. 31

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co.,

451 F.2d 418 (5th Cir. 1971) .................... 52

United States v. Masonry Contractors Ass'n

of Memphis, 497 F.2d 871 (6th Cir. 1974) ....... 34

Wade v. Mississippi Cooperative Extension

- Service, EPD J 10,770 (5th Cir. 1976) .......... 28, 52

Walston v. County School Board of Nansemond

County, 492 F.2d 919 (4th Cir. 1974) ............ 64

Watkins v. Scott Paper Co., 530 F.2d 1159

(5th Cir. 1976) .................................36, 63, 65, 66

I

i

Statutes:

i

42 U.S.C. § 1981 .................................... 6, 92

42 U.S.C. § 1988 .................................... 6

42 U.S.C. § 2000d ................................... 7, 7g

42 U.S.C. § 2000e- (5) (f) ........................... 6

42 U.S.C. § 4700 ...... ............................. 71

Tenn. Code Anno. §8-3208 ........................... 62

Tenn. Code Anno. §8-3209 ........................... 62

Regulations:

5 C.FoR. § 900 ...................................... 72

29 C.F.R. § 1607.11 ................................. 66

29 C.F.R. part 31 ................................... 7g

-iv-

Page

Other Authorities:

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 52(a) ...... 51# 92

5A Moore's Federal Practice «[ 52.06 [2] ............. 92

U.S. Civil Service Commission, Guidelines for

Evaluation of Employment Practices (1974) ...... 72

U.S. Civil Service Commission, Guidelines for

Affirmative Action (1972) ....................... 72*

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, The Federal

Civil Rights Enforcement Effort — 1974

V. 5, To Eliminate Employment Discrimination .... 74

4

j

1

J

-V-

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

No. 76-1515

ERONEOUS SHIPP, et al..

Plaint if fs-Appe Hants,

vs.

MEMPHIS AREA OFFICE, TENNESSEE DEPARTMENT

OF EMPLOYMENT SECURITY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal From The United States District Court for the

Western District of Tennessee, Western Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Questions Presented

1. (a) Did plaintiff demonstrate a prima facie case

of unlawful discrimination in referrals, etc., by the

defendant employment service?

(b) If so, did the defendants adequately rebut that

prima facie case?

2. Did the District Court err in failing to enjoin use

of the tests relied on by the defendants in hiring and

promotion?

3. Did the District Court err in failing to require

the defendants to take additional steps to assure they did

not serve employers who engage in unlawful discrimination?

4. Did the District Court err in dismissing plaintiff's

individual claim?

-2-

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Plaintiff is a black citizen who on several occasions

in the 1960's sought the assistance of the Memphis Area

Office of the Tennessee Department of Employment Security

("TDES") in obtaining employment. TDES is the Tennessee

state agency affiliated with and wholly funded by the

_L_/United States Employment and Training Administration and

provides a free employment referral service to Tennessee

residents. In the spring of 1969 plaintiff filed a timely

charge with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

alleging that TDES had unlawfully engaged in discrimination on

the basis of race. After an investigation the Commission found

there was probable cause to believe TDES had engaged in discrimina

2Jtion in violation of Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

In August 1971, the Commission issued to plaintiff a right

to sue letter.

This class action was commenced on September 16, 1971, in

the United States District Court for the Western

District of Tennessee. Jurisdiction over this action was

alleged to exist under 42 U.S.C. § 1988 to enforce 42 U.S.C.

§§ 1981-85, and under 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f). The latter

provision, contained in the 1964 Civil Rights Act, applied

to state employment services the strictures of Title VII

1 / Formerly the United States Employment Service.

_2_/ Complaint, 5 IV; Answer, 51V; 7a, 16a.

-3 -

prohibiting discrimination on the basis of race, sex and

national origin. On September 12, 1973, the complaint

was amended to allege with greater specificity the

forms of systematic discrimination in which plaintiff claimed

TDES had engaged, and to join as defendants the Tennessee

Department of Personnel and the Commissioner of Personnel of

Tennessee. On March 20, 1974, the complaint was further

amended to allege jurisdiction under Title VI of the 1964

Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d.

Extensive discovery was conducted in 1972 and 1973,

_3/including depositions of numerous employees of TDES. The

defendants furnished to plaintiff's counsel computer tapes

containing certain data on referrals between 1972 and 1973.

These tapes were subject to computer analysis and the results4_yembodied in a number of print-outs. On March 20-22, 1974,

a hearing was held before the Hon. Harry W. Wellford on

plaintiff's individual claim; plaintiff also presented his

case-in-chief in support of the class action claim. The

hearing was then recessed to permit the defendants to prepare

their response to the class action aspect of the case. At

the conclusion of this March, 1974 hearing the Court indicated

that Shipp's individual claim would only be resolved after

completion of evidence regarding and in the context of the

_5_/class action issues. On June 13, 1974, the District Court,

Exhibits 80-92; 574a-726a.

Exhibits 59-69.

Hearing of March 22, 1974, pp. 129-130.

-4-

in declining to grant a defense motion for a directed verdict,

indicated that it would "consider entering a judgment in the

Shipp case". On June 18, 1974, counsel for plaintiff wrote

Judge Wellford reiterating their understanding and desire

that the individual claim be decided only after and in the

context of the decision on the class action. As a precaution

counsel expressly asked:

If the Court should determine, prior

to presentation of the defendants 1 case

in-chief on the class action allegations,

to decide the individual plaintiff's

claim, we would appreciate an opportunity

to present a supporting brief and/or pro

posed findings of fact and conclusions of

law. 6/

The District Judge never responded to this letter,

and the defendants made no subsequent request that the in

dividual claim be decided prior to the class action claim.

On December 20, 1974, without any subsequent proceedings or

filings, the District Court entered sua sponte a 5 page

udecision dismissing Shipp's individual claim.

On April 23, 1975, another hearing was held before

Judge Wellford on the merits of the class action. The

defendants presented their case-in-chief, consisting of

the testimony of a single expert and two exhibits, and

plaintiff offered additional evidence in rebuttal. There

after both parties submitted proposed findings of fact and

also

conclusions of law. Plaintiff/moved for reconsideration of

6 / See Motion to Reconsider Order of December 24, 1974 ; 988a.

7 / Order of December 20, 1974; 740a-744a.

_5_

the December 20, 1974, order dismissing the individual

claim. On September 25, 1975, the District Court entered

a Memorandum Opinion ruling for the defendants on all class

action issues, and awarding costs against plaintiff. The

Distri-ct Court also reaffirmed its dismissal of the in

dividual claim. A timely notice of appeal was filed on

October 23, 1975.

Because of the complexity of the evidence in this

case, the relevant facts are set out in the appropriate

parts of the Argument.

-6-

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I. The defendant TDES was shown to refer white applicants

to jobs averaging 38 cents an hour more than the jobs to which

blacks were referred. Among applicants with the same occupa

tion, such as carpenter or secretary, whites were consistently

referred to higher paying jobs. This wage disparity existed

among referrals to trainee jobs requiring no experience. There

was a substantial number of jobs, all with low wages, to which

virtually all referrals were black. White applicants were

generally referred in disproportionate numbers to high paying

industries, while blacks were referred in disproportionate

numbers to low paying industries. The defendants' practice

of referring women to lower paying jobs than men had an adverse

impact on blacks because of the large number of black female

applicants. These patterns of disparities were the result of

the subjective and often standardless discretion exercised

by interviewers at TDES, almost all of whom were white. The

evidence was clearly sufficient to establish a prima facie

case of discrimination in referral.

The defendants attempted to rebut this evidence by

urging that half of the disparity was due to the fact that

the group of black applicants included more women and more

persons with limited education. They also urged that the

remaining wage disparity occurred because blacks had less

skill and experience. The record, however, contained no

substantial evidence of differences in skill and experience

sufficient to explain the pervasive pattern of disparities.

-7-

Blacks were referred to lower paying jobs than equally

educated whites, and there was no evidence as to the

job relatedness of education requirements. -The defendants'

practice of discrimination against women could not be relied

upon to explain away apparent discrimination against blacks.

II. Black employees at TDES remain largely confined to

lower paying positions such as interviewing clerk, employ

ment agent, and typist; the higher paying positions which

control the pattern of referrals, interviewers,managers,

and employer relations representatives, are virtually all

white. This is the result of tests administered by the

Department of Personnel, which were conceded to have an

adverse impact on blacks. No evidence was offered that

these tests were job related.

TDES now requires a cut-off score on the tests

substantially higher than that applied to whites in the past.

The practice of naming most interviewers from within the

agency, employed when the lower level jobs were predominantly

white, was discontinued when the lower level jobs became pre

dominantly black. The Department of Personnel acknowledged

that the cut-off scores eliminated applicants who were in fact

qualified for the jobs at issue. These practices all violate

Title VII.

III. Although TDES is forbidden by law to provide service

to employers who engage in unlawful discrimination, TDES has

only refused service to 2 or 3 employers. TDES does not seek

from E.E.O.C. or other agencies information about discriminatory

-a-

employers, and makes no effort to solicit complaints from

applicants rejected by employers. TDES maintains an

official policy of not inquiring whether the tests used

by employers violate Title VII.

IV. TDES officials refused to refer plaintiff to a

job although they had previously referred two less qualified

whites. The District Court made no express findings as to

why they had done so, although it apparently believed that,

unknown to TDES at the time of the initial refusal, the job

was already filled. In view of the conflicting evidence,

the court's failure to make such findings was reversible

error. Even if the job had in fact been filled at the time,

the defendants would still be liable for punitive damages

under 42 U.S.C. § 1981. The individual claim must be re

manded for specific findings in light, inter alia of the

pattern of class wide discrimination in referrals.

-9-

ARGUMENT

I. THE DEFENDANTS ENGAGED IN UNLAWFUL DISCRIMINATION

IN THEIR TREATMENT OF APPLICANTS FOR REFERRALS,

PLACEMENT, AND OTHER SERVICES

The complaint in this action alleges that the

Memphis Office of TDES discriminated on the basis of race

in the services it provided to applicants seeking assistance

in finding jobs. The complaint charged specifically that

the defendants had, inter alia, (a) classified and referred

black applicants for badly paid menial jobs regardless of

their actual abilities, (b) applied a more stringent standard

to blacks than to whites in making referrals to well paid

or interesting jobs, (c) given preference to less skilled,

experienced or recent white applicants over blacks who were

more skilled or experienced or who had made application for

referral at an earlier date, (d) referred only blacks to

certain poorly paid menial jobs. Despite the length and

complexity of the record before him, Judge Wellford failed

to make with regard to the controlling issues the specific

findings of fact and conclusions of law required by Rule

52(a), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, or to analyze

that evidence in the manner prescribed by McDonnell Douglas

Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973); Franklin v. Troxel

Manufacturing Co., 501 F.2d 1013 (6th Cir. 1974). Accordingly

it is necessary to review the evidence in substantial detail.

-10-

(1) Plaintiff's Prima Facie Case

(a) TDES was first established in 1936 in the wake of

the Depression. From the outset it operated on a racially

segregated basis. In 1938 the Memphis branch of the service

operated three referral offices. There were two white offices

on Union Street, one housing the Industrial Division and

another the Commercial and Professional Division. A "Colored

Office" was established on South Second Street, and housed

the Negro Men's Division and the Domestic Service. Racially

identified job orders were accepted during this period.

Although the South Second Street office was operated exclusively

for blacks, TDES did not employ blacks to work at that office

10 /

until about 1950. In 1958 the white offices were moved to a

new building at 1295 Poplar Avenue, which TDES continues to

operate. In 1960 the Colored Office was moved to South Main

Street, and its name changed to the "Domestic and Labor Office."

That office handled orders for casual and domestic labor,

which in the Dictionary of Occupational Titles ("DOT") are

coded as service jobs (DOT 3); farm jobs were subsequently

added (DOT 4

8 / Exhibits 1A, IF.

9 / See Exhibit 1 F, p. 24.

10/ Exhibit 83, Deposition of Jessie Webb, pp. 3-4 Exhibit

84, Deposition of Cecil McDonald, p. 5; Exhibit 87, Deposition

of George Murphy, pp. 3, 12; 628a-629a, 640a, 697a, 698a.

11/ Exhibit 77, Deposition of Edna Flynn, p. 9-10; 549a-550a.

_L/

- l l -

On June 1, 1962, a month prior to scheduled hearings

regarding TDES by the United States Commission on Civil Rights,

TDES announced that it was ending its policy of discrimination.

Under the reorganization plan explained to the Commission,

clerical, managerial and professional jobs, as well as skilled

and semi-skilled industrial jobs, were to be handled only at

the Poplar Avenue office, as in the past, although blacks

could now use this service. White unskilled workers, however,

could be referred only by the Poplar Avenue office, and Plack

unskilled workers only by the Main Street office. The Main

Street office was to handle "labor and domestic job orders."

There were no plans to change the office staff assignments,

pursuant to which no blacks (other than a janitor and a maid)

worked at Poplar Avenue, and the Main Street office was staffed

12/

in part by blacks but supervised by whites. In 1967 the

Domestic and Casual Labor Office moved to Monroe Street,

where it remained until 1969. Despite the 1962 announcement,

and the adoption of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, that office

11/

continued to serve the "great portion of the black traffic."

In 1969 the office on Monroe Street was closed and its functions

and employees moved to the Poplar Avenue office.

12/ Exhibit 26 ; 496a-507a.

13/ Exhibit 79, Deposition of Edna Flynn, p. 13; 551a.

-12-

Prior to 1970 the staff at TDES specialized in

particular occupations and jobs. When an employer called

to place a job order, he would be referred to the inter

viewer who handled that type of position. Similarly, an

applicant seeking referral would be sent to the interviewer

responsible for the type of position sought. The applicant

would give the interviewer a written application, and the

interviewer filed the application and later searched his files

of job orders for an appropriate vacancy. Then, as now, both

applicants and job orders were given a six digit number (e.g.

608.281) corresponding to a particular job description in

the Dictionary of Occupational Titles, and these numbers

could be used to match applicants to appropriate vacancies.

This first digit of the DOT code signified a general occu

pational classification (e.g. 2 is clerical and sales, 3

is service).

In 1970 this procedure was substantially altered.

The job order-taking was separated from the interviewing

and referral process. Orders were thereafter taken by an

employer relations representative, and placed in a computer,

known as a Job Bank. Interviewers, who had access to the

information on the computer, ceased to specialize in particu

lar occupation and dealt with any applicants in their office

regardless of what position the applicant was seeking. In

addition the list of available jobs was made directly avail

able to applicants in the Poplar Avenue office, first in

the form of a book of computer print-outs, and, later, on

-13-

microfiche cards that were used with a viewer. The print

out and cards were organized by DOT code, which the applicant

could use to find a vacancy in which he might be interested.

Once an applicant has filled out an application and received

a DOT code based on his skills and experience, he can either

go directly to the Job Bank viewers to look at available

openings or seek assistance from a counselor or interviewer.

If an applicant finds a job for which he wishes to apply, he

goes to an interviewer and asks to be referred to that job.

If the applicant is referred to a job he is given a job Bank

referral slip to present to the employer. The employer indicates

on the slip what action he took on the referral and returns

it to TDES.

(b) A systematic analysis was made of all referrals

made by TDES from July 1972 through June 1973. Because

of the volume and complexity of this data a series of tables

summarizing the information therein is set out in the appendix

to this brief. A total of 51,955 referrals were made by the

defendant during this period; of those 35,358, or 68.1%, were

JA/

black. The average hourly wage of the jobs to which blacks

and women were referred was substantially below those of the

jobs to which whites and men were referred.

Average Wage of Job

To Which Referred 15/

Type of Applicant Average Wage

Whites

Blacks

Difference

$2.47

2.09

.38 '

White Males

Black Males

Difference

2.56

2.25

.31

White Females

Black Females

Difference

2.25

1.77

.48

Men

Women

Difference

2.35

1.89

.46

This 38 cents an hour overall disparity between black and

white applicants was the result of four specific disparities.

14/ Exhibit 39, p. 2. Since some applicants were referred

to more than 1 job, and there were cases in which more than

one applicant was referred for a single vacancy, the number

of applicants seeking the assistance of TDES during this

period, and the number of job orders received by TDES, was

substantially less than 51,955; 517a.

15/ Exhibit 39, p. 3; 519a.

-15-

First, black applicants with a particular 6 digit

DOT code were consistently referred to jobs which paid less

than the jobs to which whites with the same DOT code, and

skills, were being referred. Typical examples of differing

wage rates for males with the same occupation included the

following:

Average Wage of Referrals 16J

Selected Major Male Occupations

Applicant Occupation

Shipping and Receiving Clerk

Commodities Salesmen

Arc Welder

Carpenter

Trash Collector

Loader

White

Males

Black

Males Difference

$2.53 $2.36 $ .17

3.06 2.61 .45

3.37 3.06 .31

3.21 2.79 .42

2.44 2.25 .19

2.41 2.26 .15

the same DOT code:A similar pattern existed among women with

Average Wage of Referrals 17/

Selected Major Female Occupations

White Black

Applicant Occupation Females Females Difference

Secretary $2.62 $2.25 $ .37

Key Punch Operator 2.42 2.23 .19

Record Clerk 2.17 2.02 .15

Char Woman 1.98 1.56 .40

Hand Packer 2.05 1.81 .14

Electrical Unit Assembler 2.42 2.10 .32

Since under the TDES system an applicant could not be given the

18/

DOT code for loader, etc. unless "fully experienced," no legiti

mate explanation for these differences is readily apparent.

16/ See Table 6 .

17/ See Table 8 .

18/ See Exhibit 82, Deposition of Evelyn Ryan. pp. 20-23. An

applicant who lacked the requisite experience would be given a

different code with an X in it. 6l9a-622a.

-16-

No comparable gap exists nationally between black and white

females in the same occupation. See Table 10.

There were 16 occupations involving over 40 referrals each in

which the average hourly wage for white males exceeded

19/

that for black males by more than $.50. There were no such

occupations in which the wages of black males enjoyed such

an advantage. The few instances in which black wages were

higher were generally poorly paid jobs to which over 90%

20/

of the referrals were black.

A similar pattern emerged when a comparison was

made of blacks and whites who worked in the same industry.

21/

In virtually every major industry the wages of the jobs

to which blacks were referred was lower than that of white

jobs.

Average Wage of Referrals

Selected Major Industries ̂

Amount By Which Average White

Wage Exceeded Average Black Wage

Industry Males Females

Building Construction $ .33 $ .48

Other Construction .15 .38

Food Manufacturing .31 1.02

Chemical Manufacturing .48 .22

Wholesale trade .17 .28

Retail - General .01 .16

Retail - Restaurants .16 .04

Business Services .42 .20

19/ See Table 11.

20/ E.g. porter (410 blacks, 12 whites), janitor (206 blacks,

10 whites), waitress (819 blacks, 88 whites) and hotel maid

(177 blacks, 4 whites). The average wage for all of these

jobs was under $2.00 an hour.

21/ The sole exceptions were maids and, inexplicably, female

truck drivers. "Major" denotes over 1000 referrals.

22/ See Table 25. The industries are those listed

in the Standard Industrial Classifications.

-17-

A similar pattern existed with the 10 major DOT occupation

23/

groups. Such disparate treatment of blacks and whites with

the same skills and occupations is among the -practices for-

24/

bidden by the Department of Labor.

25/

Second, there are 13 major jobs to which over 90%

of the referrals were black. These included domestic worker

(100% black), laundress and laundryman (99.73% black), clothes

presser (98.27% black), hotel maid (97.86% black), short order

cook (97.33% black) and janitor (95.41% black). Approximately

1 out of every 6 black applicants was referred to one of these

26/

black jobs. The average wage of the vacancies in these jobs

23/ Table 1.

24/ The Solicitor's Analysis of 29 C.F.R. part 31 cites as

an example of impermissible "Discrimination in Selection

and Referral to Job Openings": "Minority Applicants are

referred to auto mechanic's jobs paying $4.50 an hour whereas

white applicants are referred to auto mechanic's jobs paying

$5.75 an hour." Exhibit 18, p. 9; 459a. At TDES the average re

ferral rates for auto mechanics (DOT 620,281) was $2.50

for white males, $2.42 for black males, and $2.17 for black

females. Exhibit 67, p.090.

25/ i.e., involving at least 40 referrals.

26/ Among the 18,155 black applicants with DOT codes 3,619

were referred to these 13 jobs. The referral rate among

applicants without DOT codes is not known. See Table 14.

Only 1 in 65 white applicants was referred to any of these

jobs.

-18-

to which blacks were referred was a mere $1.60 an hour.

The handful of whites referred to these jobs, however, were

22/sent to jobs averaging $1.92 an hour.

Third, whites were referred in disproportionate

numbers to highly paid jobs and occupation groups, and

blacks were referred in disproportionate numbers to poorly

paid jobs and occupation groups. Among men the two highest

paid occupation groups are structural work ($2.69 an hour)

and professional, technical and managerial ($3.21 an hour);

35.7% of all white men were referred to jobs in these occu

pations, compared to only 13.6% of black men. Conversely,

14.7% of black men but only 4.8% of white men are referred

to the worst paid occupation group, service jobs ($2.00 an

hour). A majority of all jobs to which women were referred

were either service jobs ($2.14 an hour) or clerical and

sales jobs ($1.53 an hour). 68.3% of white women were

referred to clerical and sales jobs, compared to only 21.4%

of black women; 57.5% of black women were referred to service

28/

jobs, but only 11.7% of white women. A similar pattern of re

ferral exists among high and low paid jobs within the same

2_9/

occupation groups.

27/ Table 14. 207 blacks were referred to general cook jobs

averaging $1.73 an hour; the 15 whites referred to such jobs

averaged $2.19 an hour. Forty blacks were referred to jobs as

car wash attendants averaging $1.67 an hour; the 3 whites re

ferred to such jobs averaged $2.02 an hour. Fifty-seven blacks

were referred to jobs as clothes pressers averaging $1.71 an

hour; one white was referred to such a job at $2.00 an hour.

2 8/ See Tables 3, 4, 5 7, 9.

See Table 25.

-19-

Fourth, there is a clear pattern of discrimination

against women which, because of the proportionally larger

number of black women, has a particularly adverse impact on

blacks. As was noted, supra, average male wages exceed

average female wages by $.46 an hour. Out of 64 DOT jobs

in which more than 40 referrals were made, men received a

30/

higher average wage in 58. The most important occupation

groups for women are service, clerical and sales, which

account for 79.2% of all female referrals. Among the 17

jobs in these categories with over 100 referrals, the

average wage rates for men are more in every category.

The jobs in which men were referred to higher paying posi

tions included the following:

Average Wage of Referrals 31/

Selected Service, Clerical and Sales Jobs

Description

Average Male

____Wage____

Average Female

____Wage______ Difference

Secretary $3.08 $2.50 $ .58

Typist 2.77 2.11 . 66

File Clerk 2.90 2.52 .38

Clerk Typist 2.47 2.00 .47

Salesperson - general 2.86 1.89 .97

Cashier-checker 2.80 1.87 .93

Waiter-Waitress 1.74 1.51 .23

Cook - general 2.18 1.59 .59

Switchboard Operator 2.43 2.05 .38

Similarly, among industrial jobs where a majority of the appli

cants referred were women, men consistently were referred to

30/ See Exhibit 67.

Table 12.

-20-

better paying jobs. As the defense expert witness noted,

this disparate treatment of women has the effect of widen

ing the gap between black and white wages because of the

disproportionate number of blacks who are women.

32/ Thus male sewing machine operators were referred to

jobs averaging $2.22 an hour, and women were referred to

jobs averaging $1.71 an hour. Table 13.

33/ see p. 30, n. 66, infra. Among applicants with DOT

codes 38.4% of the blacks were women, but only 22.9% of

the whites were women. See Table 1.

-21-

(c) This pattern of disparate treatment was directly-

related to the structure and procedures at the TDES office.

(i) The 1969 merger of black and white offices

was neither complete nor permanent. In the Poplar Avenue

office the old distinctions reemerged as a separation of the

office into three functional divisions: (1) Casual, Domestic

and Farm Labor, which handles the jobs that were the traditional

34/responsibility of the black office on Main and Monroe Streets,—

(2) Commercial, Professional and Technical, which handles the

jobs that were traditionally the exclusive province of the

35/white Poplar Avenue office,— and (3) Industrial, which

handles the remaining jobs. Functional divisions soon became

physical. The Casual, Domestic and Farm Labor section was

36/

located in a separate building known as the Poplar Annex.

The 1969 merger, which for the first time brought large numbers

of black and white applicants into the same office, was followed by

37/

a "noticeable loss of white applicants." And in 1973 the

Commercial, Professional and Technical division was moved out

of the Poplar Avenue office to a new office on North Cleveland

34 / This apparently corresponds, roughly, to DOT codes 3 and 4.

35 / This apparently corresponds, roughly, to DOT Codes 0,

1 and 2 ,

36 / This apparently occurred in 1970.

37/ Exhibit 88, Deposition of Raymond Neal, p.53, 706a.

-22-

Street. The three divisions, thus separated, serve clientels

of differing racial composition. The North Cleveland office

serves an applicant group which is equally divided between whites

and blacks, and which includes about three-fourths of all white

38/

females and one third of all white males who come to TDES. The

Poplar Annex serves a group that is 99% black, including one

3 9/

half of all black females. The main Poplar office is about

two-thirds black.

This physical separation has a critical impact on referral

patterns. Despite the basic purpose of the Job Bank system, to

make all jobs readily available to all applicants, the three

offices maintain separate lists of jobs. Orders for Casual, Domestic

and Farm labor go directly to the Poplar Annex, and information

about their jobs are not sent to the Job Bank computer "until all

,,40/the people have been referred and the order is closed or filled"

The Annex does not have a viewer which would permit applicants

there to consider jobs served by the other offices. The TDES

Equal Employment Opportunity representative asked that a viewer

with commercial, professional and technical jobs be kept at Poplar

42/

Avenue when that division moved to North Cleveland Street/

38/ Exhibit 91, Deposition of Charles Rudford, 733a. Of 1407

white females with DOT codes, 1035 are in DOT codes 0, 1 and 2.

39/ Exhibit 91, Deposition of Charles Radford, 734a. Of 6981

black females with DOT codes, 4022 are in DOT codes 3 and 4.

See Table 4.

40/ Exhibit 88, Deposition of Raymond Neal, p.62. This is

done solely for record keeping purposes. 707a.

41/ Exhibit 84, Deposition of Cecil McDonald, p.28, 641a.

42/ Exhibit 88, Deposition of Raymond Neal, p.29, 705a.

-23-

but the Poplar Avenue office did not in fact have coDies

of the microfiche cards describing those jobs. Since

each office keeps its own applications there are thus three

sets of job orders and three sets of applications.

The referral patterns described supra, pp.18-19,

stem in large measure from this division of offices, orders,

and applications. if a black woman goes to the Poplar Annex

she is not referred to a clerical or sales job because that

office has no such orders. If a white woman goes to North

Cleveland Street she knows she will not be referred to a

job as a maid or a laundress because that office has no such

orders. Blacks who file applications at the Poplar office

or Annex are not considered for commercial, professional

or technical jobs that may subsequently arise because the

interviewers at North Cleveland Street do not have those appli-

tions. The job bank system functions only within the main

office for industrial jobs; otherwise the system remains

as segregated as it was prior to the 1969 merger. Although

there is evidence suggesting that TDES officials may steer

black and whites to the Annex and North Cleveland offices,

A2/ Exhibit 82, Deposition of Evelyn Ryan, p. 42, 626a.

-24-

AA'

respectively, those officials are no less culpable if

applicants are merely following the patterns established

in years of overt segregation or choosing to mix with the

applicant group of their own color. In either case TDES

has failed to establish a unitary employment service.

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S.

430 (1968) .

(ii) If a black applicant at the Poplar Avenue

office finds on a microfiche card a job order in which he

is interested, he cannot simply apply to the employer in

volved. The microfiche card available to applicants does

not disclose the identity or address of the employer who

placed the order; that information is found on a separate

set of cards to which only the interviewers,virtually all

of whom are white, have access. The applicant must there

fore ask an interviewer to tell him the identity of the

employer and refer him to the job.

The interviewers, however, do not refer to a vacancy

all applicants who want to apply. On the contrary, the

general practice is to refer only those applicants whom the

44/ See testimony of Emma Batchlor, March 22, 1974, pp.

4-8, 336a-340a.

-25-

Thus the inter-interviewer believes are "qualified",

viewer has a veto over who will and will not be able to

apply to an employer for a particular job. In exercising

that control the interviewer is, as a practical matter,

free to apply the standards strictly to one applicant

and to decide for another applicant to disregard a re

quirement or call the employer and try to persuade him to

45/

45/ Hearing of March 20, 1974, p. 172, 154a; Hearing of March

21, 1972, pp. 110-111, 244a-245a; Exhibit 81, Deposition of

Leland Dow, pp. 20, 23, 603a, 606a; Exhibit 88, Deposition of

Raymond Neal, p. 20, 703a; Exhibit 91, Deposition of Charles

Radford, pp. 65, 70-71, 708a. Jessie T. Webb, an employment

counselor, testified she tried to persuade applicants that they

should not seek referrals to jobs for which they were un

qualified. She indicated she would refer an applicant

she believed unqualified if he insisted on it despite

her attempted persuasion, but she could recall no in

stance in which this actually occurred. Exhibit 83,

pp. 20-24, 630a-634a.

-26-

waive it. In some cases, such as a requirement of

experience, the interviewer exercises broad and un

reviewed subjective judgment as to whether a previous

job is sufficiently recent and similar to the vacancy

to qualify. In plaintiff's individual case, for example,

the interviewer referred to twowhites who did not meet

the age or education requirements and then refused to

refer Shipp on the ground his experience in shipping did not

include knowledge of local shpping rates. See pp. 86-87 ,

infra.

Analysis of the TDES referral data revealed that

employer education requirements were in fact being applied

in an unequal manner. Interviewers chose to disregard

those requirements and refer undereducated whites in far

greater proportions than they did for blacks. Thus,

approximately 7.0% of whites with less than ninth grade

education were referred to jobs requiring 9-11 years, com

pared to only 2.7% of blacks. About 15.0% of whites who

4 6 /

46/ See e.g. Hearing of March 22, 1974, pp. 23-25, 363a-365a.

had not graduated from high school were referred to

jobs requiring a high school diploma, compared to only

6.2% of the blacks without degrees. Conversely, the

proportion of blacks referred to jobs for which they

had more education than required was several times greater

47/

than the proportion of whites so referred. Such unequal

application of job requirements is clearly unlawful.

Sims v. Sheet Metal Workers. 489 F.2d 1023, 1026 (6th Cir.

1973); Wade v. Mississippi Cooperative Extension Service,

11 EPD 510,770, p. 7236 (5th Cir. 1976).

(iii) An applicant can only use the Job Bank

system to pick a possible job if there is a vacancy in his

field on the day he visits TDES. Some jobs or industries

place such a large number of job orders that there is

likely to be one on a microfiche card when the applicant

is at the office. For other jobs and industries this is

not the case; the applicant leaves his application form

on file in the hope that an appropriate order will be

received. Each interviewer spends a certain amount of

47/ See Tables 17-21.

-28-

time each week conducting file searches, trying to locate

an applicant who has or approximates the qualifications

48/

for hard to fill or less common jobs. The assistant

manager of the Memphis office conceded there was a "possibility

49/

for discrimination in this situation." That is partic

ularly so because there is no standard for determining

which of the qualified applicants an interviewer will con

tact about or refer to the job. One official said the

interviewer would "try to match up the best applicant"

50/

but that there was "no standard procedure'.' Other witnesses

48/ Hearing of March 20, 1974, pp. 110- 176-78, 129a, 155a-

157a; Hearing of March 22, 1974, Testimony of Emma Batchlor,

pp. 22, 40-43, 351a, 353a-356a; Exhibit 81, Deposition of

Leland Dow, pp. 23-27, 30-34, 606a-610a, 613a-617a; Exhibit

82, Deposition of Evelyn Ryan, pp. 29-31, 623a-625a; Exhibit

87, Deposition of Lois B. Farmer, pp. 29, 30-31, 699a, 700a-

701a.

49/ Exhibit 91, Deposition of Charles Redford, p. 129, 737a.

50/ Exhibit 81, Deposition of Leland Dow, p. 30, 613a.

- 2 9 -

said they believed the practice would be to give

priority to someone the interviewer had seen personally

11/

and remembered. This Court has repeatedly condemned

selection processes which thus place the critical decision

in the hands of a largely white group bound to apply no

fixed standard. Afro American Patrolmens League v. Davis.

503 F.2d 294, 303 (6th Cir. 1974); Senter v. General Motors

Corp., 11 EPD 510,841, p. 7094 (6th Cir. 1976).

The danger of this system is well illustrated by

plaintiff's first visit to TDES in 1964, when all orders

were filled by file search. Plaintiff had completed several

years as an Air Force officer, had several years' experience

managing a large air cargo terminal and supervising a score

of employees, and had just received a Masters degree in

Business Administration from Columbia University. His

education alone put him in the top 1% of all TDES applicants.

Had plaintiff been white, his degree, combined with his mana

gerial experience, would have made him one of the most

sought after and easily placed applicants in TDES' files.

Plaintiff was never referred to a single job.

_5J/Exhibit 82, Deposition of Evelyn Ryan, p. 30, 624a; Exhibit

87, Deposition of Lois B. Farmer, p. 30, 700a.

-30-

(iv) Even if a file search, or approval of

request for referral, is handled in a non-discriminatory

manner, they both depend for their fairness on the accuracy of

the DOT code assigned to the applicant. If a black em

ployee with skill and experience was mistakenly coded for

a job below his actual abilities, his application would not

be picked out on a file search and an interviewer would

conclude he was unqualified for work which he was in fact

able to do. The DOT classification which the white inter

viewers gave to black applicants was thus critical to the

integrity of the entire referral process; given the sub

jective and unreviewed nature of that classification decision,

it was also one fraught with potential for discrimination.

See Afro American Patrolmens League v. Davis, 503 F.2d 294,

300 (6th Cir. 1974); Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457 F.2d

348, 358-59 (5th Cir.); United States v. Hazelwood School

District. 11 EPD 510,854, p. 7577 (8th Cir. 1976).

The pattern of classifications clearly suggested that

this subjective discretion had been misused. Among car

penters, for example, 76.6% of the blacks were classified

as "carpenter helpers" compared to 53% of the whites.

Similarly, 52.6% of blacks with experience in sheet metal

working were classified as helpers, compared to only 27.2%

- 31 -

of the whites. Maintenance men employed in buildings

earn substantially less than maintenance men in

factories; of black maintenance men only 25% were

classified for factory maintenance work, compared to 46%

§2/

of whites. Only about half of all applicants were

assigned DOT codes, and the use of those codes tended to

increase the disparity in referral wages. Blacks with

DOT codes were referred to jobs paying $.54 an hour less

than whites with DOT codes, a differential substantially

53/

greater than the differential for all applicants.

52/ Table 15.

53/ Compare Table 1 with Exhibit 39, 518a.

(d) Plaintiff also introduced evidence showing that

these disparities could not be explained in terms of either

education or training requirements.

The difference between black and white wages re

mained even when education was taken into account.

Differences in Average Wage of Referral

By Education54/

Education White Males v.

Black Males

White Females v.

Black Females

Males v

Females

0-8 years $ .23 $.10 .54

9-11 years .34 .23 .47

High School

Graduate .23 .52 .39

Over 12 years .03 .13 .45

Total .31 00•si*• .46

Although whites on the average had more years of education

than blacks, the wage disparity existed at every level.

Moreover an increase in education did not necessarily guarantee

55/

a significant increase in wages. Although females had, on56/

the average, more education than males, they earned less, and

the disparity existed at all levels of education. Females

with more than 12 years of education averaged about the same

57/

referral wage as males of the same race with 0-8 years.

54/ Exhibit 39

55/ Black males with 0-8 years of education averaged only

$.05 an hour less than black males with 9-11 years. White

males who had more than 12 years of education averaged only

$.04 more than white male high school graduates. And

white females who had more than 12 years of education averaged

less than white female high school graduates. Id.

56/ See Exhibit 66.

57/ Exhibit 39, p. 3. White females over 12 years averaged

$2.20, compared to $2.25 for white males with 0-8 years. Black

females with over 12 years averaged $2.07, compared to $2.02

for black males with 0-8 years, 519a.

-33-

There were 21 jobs to which whites with 0-8 years of education

wgje referred to higher paying positions than black high school

graduates. See Table 23.

Plaintiff also showed that the referral wage dis

parity between blacks and whites existed even among appli

cants to jobs for which no experience of any kind was

required. Exhibit 43 revealed the average wage rates for

trainee jobs requiring no experience in 11 major DOT occu

pation groups. The average referral wage for whites was

$.31 higher than for blacks, only slightly less than the

difference/referrals to all jobs. Moreover the same pattern

of referring whites to better paying industries emerged.

56.2% of all white females were referred to trainee jobs

58/

in stenography, typing and filing, compared to only 17.0% of

black females. 47.3% of black females were referred to trainee jobs

53/

in food and beverage preparation and service, compared to

60/

only 14.6% of white females.

This evidence was far more than required to establish

a prima facie case of discrimination. The $.38 an hour dif

ference in average black and white referral rates might alone

have been sufficient to meet plaintiff's burden. United

States v. Masonry Contractors Ass'n of Memphis, 497 F.2d

8 71, 875 (6th Cir. 1974); E.E.O.C. v. Detroit Edison, 515

F . 2d 301, 313 (6th Cir. 1975). "An employee is at an inherent

58/ DOT 20, average female wage $2.13 an hour.

sq/ DOT 31, average female wage $1.28 an hour.

60/ Exhibit 43, 526a-527a.

-34-

disadvantage in gathering hard evidence of employment dis

crimination, particularly when the discrimination is plant

wide in scope. It is for this reason that we generally

acknowledge the value of statistical evidence in establishing

a prima facie case." Senter v. General Motors Co., 11 EPD

5 10,741, p. 7093 (6th Cir. 1976). In this case plaintiff

not only proved this overall wage difference, but unearthed

a detailed and systematic pattern of disparities in the type

of jobs to which blacks and whites were referred and in the

wages of jobs for blacks and whites in the same occupation,

pp. 16-21 , supra, explained the various opportunities for

discrimination which had been used to produce this pattern,

pp. 22-32 , supra, and showed that the disparities could

not be explained by possibly legitimate considerations. In

the face of this showing the District Court had no choice

but to hold the defendants guilty of discrimination unless

they could, by clear and convincing evidence, rebut in all

relevant particulars this palpable violation of Title VII.

E.E.O.C. v . Detroit Edison Co., 515 F.2d 301 (6th Cir. 1975)

Meadows v . Ford Motor Co., 510 F.2d 939 (6th Cir. 1975).

-35-

(2) The Evidence In Rebuttal

Plaintiff having established a prima facie

case of discrimination, the burden of persuasion shifted

to TDES to demonstrate that there were nondiscriminatory

reasons for the observed disparity. Watkins v. Scott

Paper Co., 530 F.2d 1159, 1192 (5th Cir. 1976). To meet

that burden an employer (or referral service) must show

(1) that the disparity was due to differences in skills,

experience, or other criterion, (2) that the criterion was

job related, and (3) that the use of these criterion in

no way perpetuated the effects of past discrimination.

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211, 225

n.34 (5th Cir. 1974); Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine

Co., 457 F.2d 1377, 1382 (4th Cir.) cert. denied 409 U.S.

982 (1972); Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir.

1971) cert, denied 406 U.S. 950 (1972) .

TDES1 defense consisted of the testimony of Dr.

Bernard Siskin, an associate professor of statistics at

Temple University. That testimony, accompanied by a written6ly

statement and several tables, consisted of his own explana

tion of some of the data introduced by plaintiff, a commen

tary on the testimony of plaintiff's expert, and a statistical

analysis of some of the plaintiff's data. Dr. Siskin never

61/ Exhibits 94 and 95, 892a-900a.

-36-

visited the TDES office, did not examine the original

individual records of referrals, and made no inquiry into

62/

the history of TDES itself. He was offered and accepted

only as "an expert in the area of the statistical analysis

63/

and inferences that may be drawn from statistical data."

Siskin's testimony dealt with three major issues.

First, he explained he had performed a "regression analysis"

on the referral data to determine what applicant characteristics

correlated significantly with differing levels of wages. This

was done by (a) computing, with all other characteristics fixed,

the difference in wage rate associated with a given variable

characteristic,e.g., how much more men's rate was than women's

among white, college educated, 25-30 year old non-veterans;

and then (b) averaging this difference for all combinations of

the fixed characteristics. The resulting figure represented,

loosely speaking, how much the wages varied with the variable

characteristic, all other (specified) things being equal. The

analysis could not, of course, explain why there was a correlation

64/

between the varying characteristic and referral wages.

Plaintiff's data had showed that, on the average, white

applicants had been referred to jobs paying $.38 an hour more than

62/ Hearing of April 23, 1975, p.152, 756a.

63/ id., p. 159, 763a.

64/ See Exhibit 95, "Wage Rates of Referrals;" Exhibit 94,

Hearing of April 23, 1975, pp. 252-258, 856a-862a.

-37-

those to which blacks were referred. Siskin testified his

analysis yielded the following results:

Effects of the Given Variables

65/

Upon the Wage of Referrals

Variable Effect

Sex -$.41

Education +$.14 per year of education

Veteran +$.12

Age -+$.06 per year old

-$.0008 per year old squared

Race -$.18

Siskin explained this meant that, with the other variables held

constant, referral wage rates were higher for men than for

women (by $.41 an hour), for whites than for blacks (by $.18

an hour), for veterans than for non-veterans (by $.12 an hour),

and for the better educated (at a rate that rose with education).

Wage rates rose with age until the applicant reached 38, and then

declined.

Siskin urged that real difference is wages between blacks

and whites was really only $.18; blacks did worse than that,

overall, not because they were black, but because they had "less

education, they are more likely to be female and less likely 66 /

to be veterans."11" Siskin concluded that it was "reasonable"

65/ Exhibit 94, 893a; Exhibit 95, Wage Rates of Referrals, 898a,

66/ Hearing of April 23, 1975, 793a; Exhibit 95, "Wage Rates

of Referrals," 897a-899a.

-38-

and "logical" to conclude that the remaining $.18 differ

ential was due, not to discrimination, but to differences

67/

in skill and experience.

Second, Siskin reviewed the wages differences

in Exhibits 40-43, pertaining to referrals to trainee

jobs, and .argued that these differences as well were

probably due to differences in "education, experience,

veterans benefits," and the other variables noted above.

He explained that, statistically speaking, the wage dif

ferences of from $.11 to $.41 an hour revealed by these

tables, was not significant. And he argued that, even

though these were jobs for which no experience was required,

68 /

the employees would "really prefer" an experienced applicant.

Third, Siskin emphasized that plaintiffs data had

showed that, for the year in question, the referral-to-

placement ratio for blacks, the number of blacks referred

out compared to the number who got jobs, was higher than

for whites. Siskin offered two conflicting explanations,

that blacks are given greater exposure

to employment possibilities or opportu

nities by the Employment Service than

are whites ;69 /

or that

blacks referred to jobs by the Employment

Service are rejected by employers at a dis

proportionate rate relative to whites and

67/ Hearing of April 23, 1975, 794a, 795a, 860; Exhibit

95, "Wage Rates of Referrals, p. 7.

68/ Hearing of April 23, 1974, 772a-794a; Exhibit 95, pp. 3-5.

69/ Exhibit 95, p. 2-4.

-39-

racial disparity evidently exists

in the occupation structure of the

Memphis labor market. These facts

suggest that the employers may be

practicing racial discrimination

. . . .70 /

Siskin insisted, however, that such discrimination by

11/employers was none of the defendants' concern.

This evidence was insufficient to rebut plaintiff's

prima facie case for several distinct reasons.

(1) The evidence adduced by defendants purported

to explain only disparate treatment in the types of jobs

to which blacks and whites were referred. Siskin's testimony

neither bore on nor offered any defense to the fact that blacks

and whites with the same DOT code, and skill, were being referred

to jobs with different wage levels. See pp. 16-18, supra. While

Siskin argued that a randomly selected black was less likely

to be qualified for a skilled job such as a shipping clerk or

carpenter, he never suggested that those blacks who were ship

ping clerks and carpenters would be less skilled or experienced

72 /

than whites. The evidence revealed that whites were better

paid than blacks in the same DOT category regardless of whether

the category was predominantly white (e.g. professional, technical

and clerical) or predominantly black (e.g. service). The evidence

70/ Id., "Wage Rates of Referrals,” pp. 8-9, 899a-900a.

71/ Id., see also Hearing of April 23, 1975, pp. 166-67,

220-21, 242-48,. 700a-701a, 824a-825a, 846a-852a.

72/ Indeed, given the historic barriers that have existed

to minority entry into these jobs, it would be reasonable

to expect those blacks who had entered them to be unusually

skilled and motivated.

-40-

adduced by defendants suggested no legitimate explanation

for this disparity. Nor did the defendants offer any

legitimate explanation for a variety of other discrimina

tory practices, including referring only blacks to certain

types of jobs, referring disproportionate numbers of whites

to jobs for which they were educationally ungualifed, re

ferring disproportionate numbers of blacks to jobs for

which they were educationally over qualified, etc. See

pp. 18, 27-28, supra.

(2) There was no substantial evidence that black

applicants at TDES actually had a lower level of skills and

experience than white applicants. Siskin suggested this might

be the case if one assumed the distribution of skills and

experience among black and white applicants was exactly the

same as among the Memphis labor force as a whole. But as

Siskin himself recognized, that assumption is without founda

tion. Siskin noted that professionals and managers, the major

high skill white category, are "considerably less likely to

73/

use Employment Security" than others. Equally important,

proportionally speaking blacks are over 7 times as likely as

74/whites to use TDES, and thus the sample of the workforce doing

so is skewed in some unknown manner. Beyond his hypothesis

concerning the Memphis work force Siskin could offer no reason

for believing black applicants were less skilled or experienced;

TkJ Exhibit 95, p. 1, n.l, 894a.

74/ Non-whites constitute approximately 30% of the work force

in the Memphis area, and 69.8% of the TDES applicants. Exhibit

39. Black females are over 10 times as likely to apply to TDES

as white females.

-41-

he had deliberately refrained from conducting any studying

of the defendants 1 records to see if there were actual dif

ferences in skills or experience.

If the composition of the regional work force were

accepted as proof of the skills of actual applicants, it would

constitute a defense to every case of discrimination in hiring.

There is not a major city in the country in which blacks as

a whole are not significantly less trained and experienced

than whites. No court has ever suggested that an employer

could justify or explain disparate treatment of black applicants

on such a flimsy basis.

(3) Siskin's explanation of Exhibits 41-43 was pre

mised on the assumption that jobs for which experience was

helpful would be better paid, and that this difference in

wage level accounted for the difference in the wages of the

jobs to which blacks and whites were referred. If that were

so wages for trainee jobs requiring no experience would be

far lower than wages for all jobs, since the latter group

includes large numbers of jobs which are not open to trainees

21/and for which experience is necessary. And, if the proportion

of blacks without experience is lower than among whites, the

difference between black and white wages should be far smaller

among trainees than among total referrals. In fact, however,

neither hypothesis is supported by the data.

75/ Trainee jobs requiring no experience accounted for only

40% of the jobs in the 11 DOT categories which are covered

by Exhibits 43 and 55.

-42-

76/

Average Wage Rates

Selected DOT Codes

All Referrals

Trainee Jobs

No Experience

Required

White Males $2.40 $2.41

Black Males 2.16 2.17

Difference .24 .24

White Females 2.13 2.05

Black Females 1.64 1.64

Difference .49 .39

All Whites 2.34 2.33

All Blacks 2.01 2.03

Difference .33 .30

Contrary to Siskin's assumption, inexperienced trainee wages

were equal to or greater than ordinary referral rates

for all groups other than white females, and removing ex

perience requirements had only a marginal effect on the gap be

tween black and white wages.

(4) In explaining the substantial wage difference

for whites and blacks referred to trainee jobs requiring no

experience, Siskin hypothesized that, although the employers

involved did not require experience, large numbers of the

77/

employers involved in fact desired experience. Although

76/ Exhibits 43, 55, 526a-527a.

21/ Exhibit 95, p. 5; Transcript of Hearing of April 23, 1975, p. 174, 778a.

-43-

there were 11,748 referrals to such jobs the only evidence

offered in support of this hypothesis was a sample print

out showing 2 instances in which such a desire had been

23/

expressed. The defendants offered no testimony by TDES

employees with personal knowledge as to the frequency of

such requests. Although the records of the job orders in

question were in the defendants' possession, TDES did not

offer into evidence either the records themselves, a sum

mary of their content, or a computer analysis thereof.

Such a selective presentation was clearly insufficient

to meet the defendants' burden of establishing that experience

or skill was actually desired by the employers.

(5) Siskin speculated that the difference in the

referral ratio revealed by plaintiff's study might have

been caused by a systematic TDES practice of trying to

assist blacks by referring them to high paying jobs for

which they were not qualified. He hypothesized that a black

applicant would receive a series of progressively less attrac

tive referrals until a position was found for which the appli-

79/

cant's qualifications were adequate. On this hypothesis, it

was noted, the wages of the jobs in which blacks were placed

would be substantially lower than the average rate for the

positions to which they were referred, and the gulf between

black and white placement wages significantly greater than

that for referral wages. Not a shred of evidence was introduced

ip/ Exhibits 72 (A) and (B) . The two trainee jobs involved

were for a janitor (DOT 382.884) and a security guard (DOT

372.868). Blacks constitute 95.4% of the referrals to the

jobs with the former code and 76.9% of the referrals to jobs

with the latter. See Exhibit 67, pp. 067, 068.

JJL/ Hearing of April 23, 1975, pp. 166-67, 220-21 * a a'

ST5a. _ 4 4 _

to support this hypothesis, and the defendants did not produce

from their files a single instance in which a black had re

ceived a series of referrals in the manner theorized.

Documents in the possession of the defendants belied

80/

this speculation. The TDES computerized report for the year

ending January 31, 1972, showed that well educated applicants

required more referrals than the uneducated, that welfare clients

sent to TDES were placed very easily, and that applicants

classified as lacking minimal amounts of education, skill or

experience required fewer referrals than ordinary clients.

Although plaintiff's study showed blacks had a lower referral

to placement ratio for the year ending June 1973, the TDES

report showed whites had a higher ratio for the year ending

81/

January, 1972; the variation suggesting the difference is

of little significance. The difference between the wages

of blacks and whites actually placed was slightly smaller

than the difference in the rates of the jobs to which they

82/

were referred.

(6) The regression analysis prepared by Dr. Siskin

was legally inadequate for several reasons.

80/ The report in question was disclosed to plaintiffs as

part of discovery and is reprinted as Table 26.

81/ See Table 27.

82/ The difference in the average placement wage, as revealed

by Table 26, was approximately $.34. The difference in the

average referral wages, as revealed by Exhibit 39 was $.38.

The change may be due to inflation, since the first figure is

for the year ending in January, 1972, and the latter for the

year ending in June, 1973.

-45-

(a) The major independent variable used by Siskin

to reduce the difference between black and white applicants

was sex. Siskin's analysis showed that, all other things

being equal, female applicants were referred to jobs paying

$.41 an hour less than males. Since there was a dispropor

tionate number of black females, this "explained" a large

part of the apparent difference between blacks and whites.

While this exercise was statistically interesting, from a

legal perspective it was simply an assertion that the de

fendants were really discriminating on the basis of sex

rather than race, and that this merely happened to have an

adverse impact on blacks. That is not a defense cognizable

under Title VII.

(b) The second variable relied on by Siskin was

education, which his analysis suggested increased referral

wages at the rate of $.18 per year of education. Since, as

Siskin stressed, black applicants tended to be less well

83/

educated than whites, this also helped to "explain" the

lower wages paid to blacks. That explanation is precisely

the adverse impact which under Title VII triggers a require

ment that the defendant prove the use of an education standard

is job-related. Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971).

Dr. Siskin expressly noted that his analysis,

83/ Exhibit 95, p. 5, 898a.

-46-

does not imply validity to the

education requirement. However,

the employment Service simply

makes referrals to employers it

does not hire. The question of

the validity of education must fall

on the employer not the Employment

Service which tries to fill a job

order.

There was, however, no evidence that less educated applicants

were referred to poorly paid jobs due to employer requirements

rather than criterion formulated by TDES employees. Even if

that were the case, Siskin was wrong in his assumption that

TDES could serve with impunity employers which used education

requirements that violated Title VII. See pp. 78-85, infra.

The reliance of this state agency on the inferior education

of blacks must be considered in light of the role of other

arms of the state in maintaining a segregated and inferior

black school system throughout most of this century. See

Northcross v . Board of Education of Memphis City Schools,

466 F .2d 890 (6th Cir. 1972); Gaston County v. United States,

395 U.S. 285 (1969). Similarly, in view of the defendant's

admitted past discrimination, and of its importance to the

black community in Memphis, it would at the least be difficult

for TDES to establish it was in no sense responsible for the

allegedly lower levels of black skills and experience. The

sole defense witness conceded he had no idea what role TDES

might have had "in the past in perpetuating or establishing

discrimination [or a] discriminatory pattern in the labor

85/

market."

Id., n.Hearing 9.of April 23, 1975, pp. 261-62, 865a-866a.

-47-

(c) The regression analysis was able to "explain"

only half of the $.38 an hour wage difference between black

and white referrals. It still revealed that, even holding

constant sex, education, veteran status, and age, blacks

still were referred to jobs paying $.18 an hour less than

whites. Although Siskin believed this difference was due to

differences in skill, experience, and "special education,"

there is nothing in the record to support such a belief.

The evidence offered by TDES in defense of this

action was palpably inadequate to meet its burden of per

vasion that there were nondiscriminatory reasons for the

observed disparity.

-48-

(3) The Opinion of the District Court

The Memorandum Opinion of the District Court

failed to resolve the controlling factual and legal issues,

or to make the structured analysis of the evidence required

by McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973),

The only reference to the possible existence of a prima

facie case was the following statement:

There was a significant dispute between

sincere experts who testified in this

cause as to the effect of statistical

studies and analysis and not only whether

they indicated a prima facie case of

employment discrimination, but also

whether they indicated racial discrimina

tion at all as to the effect of TDES

services when factors of skill, education

and experience were taken into account.86/

The opinion is devoted largely to an incomplete and not

87/

entirely consistent summary of the evidence. Compare Franklin v

Troxel Mfg. Co., 501 F .2d .1013 (6th_ Cir .. 1974) .

The limited findings of the District Court were

equivocal, inconsistent, and tangential to the central issues

of the case. The court noted there had been some "good faith"

86/ Memorandum Opinion, September 25, 1975, pp. 15-16, 1008a-09a

87/ The opinion, at page 12, relies on Dr. Siskin for the

proposition that "it is almost three times more likely that

a white applicant is high-skilled than a black is high-

skilled." Two pages later the opinion states, "whites who

apply at the Memphis Office of TDES are almost twice as

likely to have high skill experience than blacks." P. 14.

The record in fact contained no evidence as to the actual

skills and experience of black and white applicants.

Compare 1005a with 1007a.

-A9-

efforts by management "although not entirely effective, to

alleviate effects of past discrimination within the internal

structure of the office and in its impact on the Memphis

employment community," and "to eradicate past effects of

88/

segregation and discrimination." Manifestly the existence

of such ineffective good faith efforts was not a defense

to the underlying cause of action. See Griggs v. Duke Power

Co. , 401 U.S. 4 2 4 , 4 3 2 - 33 (1971); Albemarle Paper Co. v.

Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975). Paradoxically, having thus

noted the existence of past discrimination by TDES and its

impact on the community, the court also stated it could "not

find any basis to attribute to the Memphis Office of TDES

a realistic causative force" in the alleged differences in

experience and education, which the court blamed instead

on "the community itself, and the private sources of em-

89/

ployment." The impact of TDES1s discrimination on community

employment patterns, noted on page 14 of the opinion, was

forgotten by page 15. And the widespread private discrimina

tion relied on at p. 15 was forgotten when the court, con

fronted by evidence that TDES had terminated service to only two

or three employers in recent memory, failed to compel TDES to

comply with its statutory duty not to do business with dis

criminatory employers. See pp. 78-85, infra.