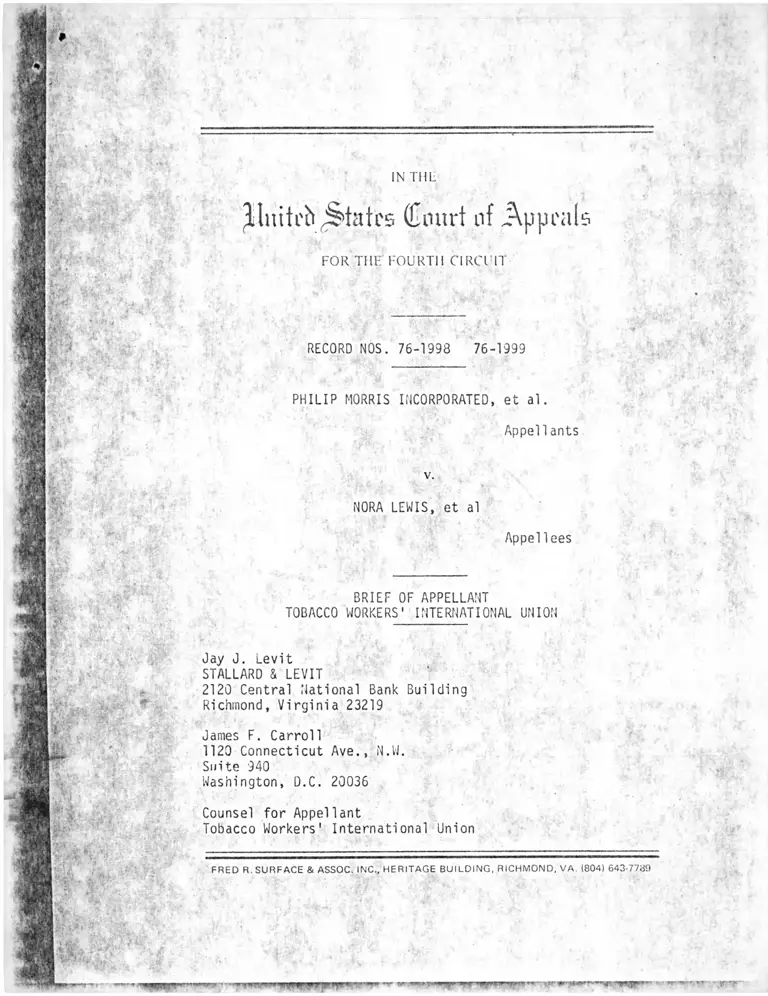

Philip Morris Incorporated v. Lewis Brief of Appellant

Public Court Documents

December 15, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Philip Morris Incorporated v. Lewis Brief of Appellant, 1976. cd71a7c0-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0c3ccca0-3c86-46d4-879d-f0c4b45c04bd/philip-morris-incorporated-v-lewis-brief-of-appellant. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Copied!

^ lu itcb S t a t e s (Gintrt nf A p p e a ls

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

RECORD NOS. 76-1998 76-1999

PHILIP MORRIS INCORPORATED, et al.

Appellants

NORA LEWIS, et al

Appellees

BRIEF OF APPELLANT

TOBACCO WORKERS' INTERNATIONAL UNION

Jay J. Levit

STALLARD & LEVIT

2120 Central National Bank Building

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Janies F. Carroll

1120 Connecticut Ave., N.U.

Suite 940

Washington, D.C. 20036

Counsel for Appellant

Tobacco Workers' International Union

FRED R. SU RFA CE & ASSOC. INC., HER ITAGE BU ILD IN G , RICHMOND, VA. (804) 643-7789

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

STATEMENT OF ISSUES I

STATEMENT OF THE CASE 2

District Court's Orders and Defendants'

Appeals Therefrom 2

The District Court's Definition of the

Class 4

The Substantive Issues at Trial 4

The District Court's Ruling With Respect

to the Quarles Decision 5

The District Court's Finding of Local

Union Liability 6

The District Court's Finding of Inter

national Union Liability 8

The District Court's Theory That the

Plaintiff Class Was Ignorant of the

Long-Standing, Non-Discrimination Employ

ment Policy d

ARGUMENT 10

1. The International Union Can Not Be

Held Liable In Any Event Because The

Evidence And Stipulations At Trial

Show That The International Union Was

Not The Collective Bargaining Agent For

Members Of The Plaintiff Class, And There

Is No Basis To Predicate International

Union Liability Simply Upon Local Union

Liability 10

CONCLUSION 17

age

9

12,

12

12

12

12

12

12

12

12

12

12

12

12

AUTHORITIES CITED

(Cases)

Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 279

F. Supp. 505 (E.D. Va., 1968)

United Mine Workers v. Gibbs, 383

U.S. 715 (1966)

Coronado Co. v. United Mine Workers,

268 U.S. 295, 299 (1925)

United Mine Workers v. Coronado Co.,

259 U.S. 344, 393 (1922)

United Construction Workers v. Ha is lip

Baking Company, 223 F. 2d 872 (CA 4),

cert, denied, 350 U.S. 847 (1955)

Di Giorgio Fruit Corporation v. NLRB,

191 F. 2d 642 (D.C. Cir.), cert. denied,

342 U.S. 869 (1951)

Pennslyvania Mining Co. v. United Mine

Workers, 28 F. 2d 851 (CA 8), cert. denied

279 U.S. 841 (1928)

Axel Newman Co. v. Sheet Metal Workers,

37 LRRM 2038 (D. Minn. 1955)

SIU (Upper Lake Shipping), 139 NLRB 216

(1962)

Int'l. Longshoremen (Sunset Line and Twine

Company), 79 NLRB 1487 (1948)

National Union of Marine Cooks (Irwin-Lyons

Lumber Company), 87 NLRB 54 (1940)

General Electric Company, 94 NLRB 1260

(1951), modified sub nom.,

NLRB v. Local 743, Carpenters, 202 F. 2d

516 (CA 9, 1953)

Bay counties District of Carpenters (United

Slate, Tile & Composition Roofers, 117 NLRB

958 (1957)

- " T " " T H P T » y ) | V

Page

Coronado Coal Co., 259 U.S. at

395-96 13

Coronado Coal Co. v. United Mine Workers

268 U.S. 295, 304-05 (1925) 13

United Construction Workers v. Haislip

Baking Co., 223 F. 2d 872 (CA 4, 1955)

cert, denied 350 U.S. 847 (1955) 13

International B otherhood of Electri

cal Workers (Franklin Electric Construction Co.)

121 NLRB 143, 42 LRRM 1301, (1958) 13

Amalgamated Meat Cutters (Iowa Beef Packers,

Inc.,), 188 NLRB 5, 6, 76 LRRM 1273 (1971) 14

Gray v. Asbestos Workers, Local 51,

416 F. 2d 313 (CA 6, 1969) 14

Morgan Drive-A-Way, Inc. v. Teamsters,

268 F. 2d 871 (CA 7, 1959) cert.

denied, 361 U.S. 896 (1959) 14

Baisfoot v. International Brotherhood of

Teamsters, 424 F. 2d 1001 (CA 10, 1970) 14

Le Beau v. Libbey-Owens-Ford Company, 484 F 2d

798 (CA 7, 1973) 15

Jamison v. Olga Coal Co., 335 F. Suppl 454

(S.D. W. Va., 1971) 15

Butler v. Local 4 and Local 269, Laborers’

International Union, 308 F. Supp„ 528

(N. D. 111. 1969) 15

Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co., 271 F.

Supp. 27 (E.D. N.C., 1967) 15

United Mine Workers (Blue Diamond Coal Co.)

143 NLRB 795, 797, 798 (1963) 15

Associated Builders v. NLRB, 532 F. 2d 749

(No. 75-1716, January 27, 1976, 78 LC Para.

11,312 16

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 76-1998 -- 76-1999

NORA LEWIS , et al. Appellees, •

v .

PHILIP MORRIS INCORPORATED, et al. Appellants.

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF APPELLANT

TOBACCO WORKERS' INTERNATIONAL UNION

Statement of Issues

1. Can the International Union be held liable even though

it was not the collective bargaining agent for members of the

plaintiff class; can International Union liability simply be pre

dicated upon Local Union liability?

2. Can the International Union be held liable when the

District Court has found exclusive and fair representation of

the plaintiff class by the Local Union?

3. Can the International Union be held liable when the

record is devoid of International Union knowledge, authorization,

or ratification of Local Union acts or omissions?

1 ...

- 2-

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

District Court's Orders and Defendants' Appeals Therefrom.

On July 7, 1976, the District Court entered its judgment order and

memorandum (Tt. App. , 112 et sea.) giving judgment to the plaintiffs

against the defendants. Defendant Local Union No. 203 filed its no

tice of appeal therefrom on August 6, 1975 (Jt. App., 140), as did

defendant Tobacco Workers' International Union (Jt. App., 141). On

September 2, 1976, the District Court entered an order adopting plain

tiffs' back pay and injunctive relief guidelines (which were attached

thereto) (Jt. App., 142 et seg.), and both defendant Unions filed amended

notices of appeal therefrom on Ocotober 1, 1976 (Jt. App. , 153-154) . The

defendant Company also filed a timely notice of appeal from the District

Court's said September 2, 1976 order on September 29, 1976 (Jt. App., 8).

On September 27, 1976, plaintiffs filed their motion with the District

Court for supplemental findings of fact and conclusions of law to support

plaintiffs' back pay and injunctive relief guidelines which the District

Court had already adopted in its September 2, 1976 order (Jt. App., 8).

On October 6, 1976, the defendant Unions filed their opposition with the

District Court to the plaintiffs' said motion, on the grounds that the

said motion was untimely and the defendants had perfected their appeals

(Jt. App., 8). The defendant Company filed its memorandum inqoposition

to the plaintiffs' said mctLon on October 5, 1976 (Jt. App., 8).

iJ jW Pj W W ' . .... . W I I I I I P . I .P-HW..UI i. p y j m .............................. .. I . -----

-3-

On October 5, 1976, the defendant Company also filed its oppo

sition with the District Court to plaintiffs' motion for award of inter

im attorned fees, and the defendant Unions filed their opposition to said

motion on October 6, 1976, (Jt. App. , 3). On November 17, 1976, the

District Court entered an order vacating its said September 2, 1976, order

which had adopted plaintiffs' back pay and injunctive relief guidelines

(Jt. App.., 159). Two cays prior thereto, on November 15, 1976, the Dis

trict Court entered an order awarding attorneys' fees to the plaintiffs

(Jt. App 157). On or about November 29, 1976, the defendant Company

transmitted to counsel for the plaintiffs the Company's check in t *̂ie

amount of $50,000 as payment of the attorneys' fees pursuant to the

Court's said November 15, 1976, order. This payment was accepted by

plaintiffs' counsel. On or about November 17, 1976, the District Court's

order dated October 12, 1976, was filed with the District Court clerk,

and copies were mailed to counsel for the parties on November 17, 1976.

The District Court's said October 12, 1976, order, which, was not filec

with the District Court clerk until on or about November 17, 1976, stayed

the District Court's said September 2, 1976, order adopting plaintiffs

back pay and injunctive relief guidelines, as well as all other proceed

ings in the District Court during the pendency of the appeal (Jt. App.,

9, 139).

Although the District Court stated that it had had second thoughts

about the plaintiffs' guidelines for back pay and irrpnetive relief pre

viously adopted and thereafter vacated by the District Court pending the

mwmm mmmm

appeal, the District Court stated to counsel for the parties in open

court that this did not necessarily mean the District Court would make

changes to the said guidelines (Jt. App. , 181). On this same date

in open court, November 3, 1976, the District Court advised counsel

for the parties that it would stay the case (Jt. App., 181). On or

about October 29, 1976, plaintiffs filed with this Court their motion

to dismiss the appeal as being premature, defendants thereafter filed

their respective oppositions thereto, and as of the writing of this

brief the Court has not ruled on plaintiffs' said motion. In their

opposition to plaintiffs' said motion to dismiss the appeal, among

ether things defendant Unions advised this Court that the defendant Com

pany had already partially complied with a portion of the back pay and

injunctive relief guidelines subsequent to the District Court's adop

tion thereof, and prior to the District Court's order vacating its order

adopting said guidelines (cf. the September 28, 1976 District Court

docket entry, Jt. App., 8).

The District Court's Definition of the Class. For purposes of

the trial below, the District Court had certified the class as consist

ing of the named plaintiffs and all females and black males, whether

currently employed or no longer employed for any reason, who were em

ployees of the defendant Company's Green Leaf Stemmery on or after

July 2, 1965 (Jt. App., 116).

The Substantive Issues at Trial. On April 17, 1975, an agree

ment between the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and the defen

dant Company was filed with the District Court clerk in Civil Action

•5-

No. 181-73-R, in settlement of the Commission's suit which had been

brought against the Company only, alleging Title VII discrimination

by the Company gainst black and female employees and prospective

employees because of their race and sex. In the settlement agreement,

the Company expressly denied any discrimination on its part (Jt. App., 209) .

On March 17, 1975, counsel for the defendant Company and the plaintiffs

(but not Union counsel) entered into an agreement limiting the issues of

the trial below (Jt. App., 90). The issues thus framed for trial by plain

tiffs and the Company were as follows:

(a) Whether the members of the class were hired into the Stem-

mery rather than into permanent employment as a result of racial or sexual

d iscriminati on;

(b) whether the transfer, promotion, seniority, initial job

assignment and wage rate policies discriminated against class members on

the basis of race or sex, except in the selection of supervisory and

craft personnel; and

(c) if discrimination were found, the appropriate injunctive re

lief, back pay, costs, expenses, and attorneys' fees would be determined.

Further, all claims for affirmative relief sought on the basis of alleged

discriminatory working or disciplinary conditions were withdrawn, and the

maternity leave issue was expressly reserved. The District Court so

found (Jt. App. , 118) .

The District Court's Ruling With Respect to the Quarles Decision.

The District Court ruled that its prior decision in ftusrles_ v. P h i p

-6-

MSEiLlLSi_IiiG.• « 279 F. Supp. 505 (E.D.VA., I960) , was not dispositive of

the race discrimination claims asserted at trial. The District Court

conceded that in Quarles the class did include Green Leaf Stemmery em

ployees (dt. App. , 1?.].) , but the District Court ruled that in Quar3.es

the failure to enter an order directing all class members to be noti

fied of the action so that they could champion their own interests

violated due process standards, so that the Stemmery employees were not

parties in any meaningful sense in the Quarle3 action, and were not

bound by that decree (Jt. App., 125-126). The District Court made this

ruling notwithstanding the fact that in Quarles, then District Court

Jugge Butaner found no evidence of discrimination in tlie Stemmery in

initial or additional job assignments, pay, transfer and promotion

policies, or selection of employees for craft, skilled and supervisory

positions. Counsel for the plaintiffs in Quarles were the same as

counsel for the plaintiffs in the case at bar.

The District Court's Finding of Local Union Liability. The Dis

trict Court conceded that the defendants produced evidence indicating

that blacks are more willing to accept employment at the Seasonal faci

lity (Stemmery), and that the permanent departments have a substantial

proportion of black workers (Jt. App., 129). However, the District

Court apparently found Company and Union liability based on the testi-

mo, y of one single witness who testified for plaintiffs in part that

"if you want to get hired, you know, being black, your best chance would

be to go through the Stemmery and then transfer to permanent employment

later" (Jt. App., 132). The District Court further conceded that it

could not find the Company * a 'bxcessive assignment of blacks to the Stem-

mery was purposefully undertaken by the Company to covertly continue its

historical system of segregated departments" (Jt. App., 133). However,

the District Court found that the Company, even though it assigns new

hires without regard to their race, "has unfortunately done nothing to

dispel the belief, founded on its past acts of discrimination, and held

by 3 substantia 1 number of black applicants, that it still assigns to de

partments new hires on the basis of race. Such a belief has translated

itself into a set of circumstances that has continued to place blacks

at a disadvantage when seeking employment at Philip Morris" (Jt. App., 133

The District Court thereafter concluded that "all those class members that

were not so informed when they were hired into the Stemmery, and that be

lieved that their race substantially limited their initial employment to

the Stemrnery are entitled to recover for their losses" (Jt. App., 134).

The District Court then further concluded that "it is the duty

and the burden of the defendants to inform all potential applicants for

the various openings of said openings a3 they develop and that these

openings would be filled without regard to sex or race. Those appli

cants in the class that were not so informed and that would have applied

for any such openings if informed, are entitled to recover" (Jt. App., 135)

Referring to it3 rationale aa "theories" (Jt. App., 136) , the District

Court then held the Local Union liable along with the Company under the

District Court's said theories. The District Court stated that the Local

Union had to "share the responsibility for informing its members that

' 1 W W W " T

-8-

all jobs are open in all departments without regard to race or sex so

as to mollify members' present understandings as based on past history.

Its failure to perform this function makes it jointly liable with the

Company to those plaintiffs entitled to recover” (Jt, App., 136). The

District Court further made the following additional findings with res

pect to Union liability:

(a) there is no evidence of Union arbitrary action or bad

faith conduct toward class members in the handling of class members'

grievances (Jt. App., 136);

(b) there is no evidence of Union arbitrary action or bad

faith conduct toward class members in the collective bargaining pro

cess with the Company (Jt. App., 136);

(c) collective bargaining contract seniority, transfer, and

promotional provisions need not be changed (Jt. App., 135)7 and

(d) there has been no breach of the Union statutory duty of

fair representation (Jt. App., 136).

In it3 written motion to dismiss filed prior to trial (Jt. App.,

43), the Local Union in part relied upon the District Court's prior de

cision in Quarles, and the Local Union at trial also moved to dismiss

the complaint as against it because there was no evidence to show a

breech of the Local Union's duty to faidy represent the members of the

plaintiff class (Jt. App., 961-962).

The District Court's Finding of International Union Liability.

Noting that the International Union was not served with notice of the

EEOC charges, nor approached by the EEOC in conciliation negotiation

i .m li p . . , mi I i m P m i — H -Li i . ' . ■ ■ n n n u i in i - . m m " iyn i ' np i iin . i . n ■ p ji. - n m i i w n m i ^ w ip m » M > n - i p j in ) mi n i i. i y ■

-9-

(Jt. App., 119), the District Court found International Union liability

because "the International was an active advisor to the Local, and sat

in on most of the Local's negotiations with the Company for collective

bargaining agreements" (Jt. App., 139). The District Court so ruled not

withstanding its finding that the employees involved were represented

by the Local Union only (Jt. App., 114-115), and that counsel for the

parties had so stipulated in stipulations numbers 8, 52 and 53, to the

express effect that the collective bargaining agreements involved were

entered into and negotiated by and between the Company and the Local

Union only (Jt. App., 96, 108). In its written motion to dismiss filed

prior to trial (Jt. App., 45), the International Union relied in part

upon the District Court's prior decision in Quarles, and at trial the

International Union relied upon the said stipulations of the parties

(Jt. App., 962-964) .

The District Court's Theory That the Plaintiff Class Was Ignoram

of the Loni-Standing, Non-Discrimination Employment Policy. The District

Court adhered to its liability theory that the plaintiff class was igno

rant of the long-standing, non-discrimination employment policy, not

withstanding the stipulation of counsel for the parties that since 1963

"the bargaining committee of Local 203 has included both wnite and black

employees" (Jt. App., 97).

-10-

Argument

It is submitted that the District Court's finding of lia

bility on the International Union's part is erroneous for the

same reasons advanced by the Local Union in its brief concerning

the District Court's finding of liability on the Local Union's

part. Additionally, as follows hereinafter, the District Court

erred with respect to the International Union.

1. The International Union Can Not Be Held Liable In

Any Event Because The Evidence And Stipulations At Trial Show

That The International Union Was Not The Collective Bargaining

Agent For Members Of The Plaintiff Class, And There Is No Basis

To Predicate International Union Liability Simply Upon Local

Union Liability.

The District Court correctly found that Local Union No. 203

was the duly designated exclusive collective bargaining agent

for the plaintiffs and the class they represent (Jt. App., 114-

115). In stipulations Nos. 8, 52 and 53 (Jt. App., 97, 108),

counsel for the parties stipulated at trial that the pertinent

collective bargaining agreements and negotiations therefor were

by and between defendant Company and Local Union No. 203. Stip

ulation No. 53 expressly states that "labor rates . . . are estab

lished exclusively by negotiation between the Company and the

Local Union . . . since before 1960." Union witnesses Mergler

(Jt. App., 887-888), and Pearce (Jt. App., 906), so testified,

and the recognition clauses of the collective bargaining agree

ments in evidence which define the parties thereto so state. As

both Mergler and Pearce testified, and their testimony was not

11-

contradicted, the International Union assisted the Local Union

in negotiations only at the request of the Local Union, and the

negotiated contract provisions were approved by the Union mem

bership. Final contract approval by the International Union

was only for the purpose of assuring that there were no vio

lations of law incorporated therein (Jt. App., 867, 906)„ As

Mergler's uncontradicted testimony showed, "all Local Unions

are self-autonomous, and only the membership themselves can

reject or accept any contract. And this is done with or with

out the approval of any of the officers of the International

Union" (Jt. App., 867).

Accordingly, the District Court's finding of International

Union liability soley because the International Union "sat in

on most of the Local's negotiations with the Company" (Jt. App.,

139), is clearly erroneous and it is not supported by the record.

This is especially so in view of the District Court's correct

conclusion that at all material times Union representation of

the plaintiffs' and the class they represent was fair and proper,

and that collective bargaining contract provisions concerning

seniority, transfer, and promotion need not be changed (Jt. App.,

135-136).

International Union liability predicated simply upon a fin

ding of Local Union liability is likewise clearly erroneous. Here,

the District Court found the Local Union liable because it sup

posedly did not advise its membership of the long-standing, non

discrimination employment policy applicable to the membership,

and because the membership was supposedly ignorant of that fa

vorable employment policy. The condemned omission of the Local

Union which the District Court found was a failure to advise,

* — ........ . ................— — — ■*— ■--------------------------------— ■— — ---------- ------ --— ■— — — — -------------------------

-12-

rather than some actual misconduct. Since there is no question

in the record below that the Local Union was in charge of the

day-to-day collective bargaining affairs of its membership and

the bargaining unit which it represented, clearly the Interna

tional Union can not be held liable for having incited or en- ^

couraged the Local Union's supposed failure to advise its mem

bership. United Mine Workers v. Gibbs, 383 U.S. 715 (1966).

The Local Union, as the evidence showed, was self-autonomous,

an entity separate from the International Union, self-governing

and independent thereof. Under these circumstances, it is firmly

established Court and National Labor Relations Board law that

the International Union can not be held responsible for the acts

or omissions of the Local Union. Coronado Co. v. United Mine

Workers, 268 U.S. 295, 299 (1925); United Mine Workers v. Coro

nado Co., 259 U.S. 344, 393 (1922); United Construction Workers

v. Haislip Baking Company, 223 F. 2d 872 (CA 4), cert. denied,

350 U.S. 847 (1955); Pi Giorgio Fruit Corporation v. NLRB, 191

F. 2d 642 (D.C. Cir,), cert. denied, 342 U.S. 869 (1951); Pen-

nsiyvania Mining Co. v. United Mine Workers, 28 F. 2d 851 (CA

8), cert. denied, 279 U.S. 841 (1928); Axel Newman Co. v. Sheet

Metal Workers, 37 LRRM 2038 (D. Minn. 1955); SIU (Upper Lake

Shipping), 139 NLRB 216 (1962); Int’1■ Longshoremen (Sunset Line

and Twine Company), 79 NLRB 1487 (1948); National Union of Marine

Cooks (Irwin-Lyons Lumber Company),87 NLRB 54 (1940)| General

Electric Company, 94 NLRB 1260 (1951), modified sub nom., NLRB

v. Local 743, Carpenters, 202 F. 2d 516 (CA 9, 1953); cf. Bay

counties District of Carpenters (United Slate, Tile & Composition

Roofers), 117 NLRB 958 (1957).

i . . ’■’" q M P M M ^ * * **** ....i' J ■■■I'.tWJ' —---

- L3-

A local union is not, per se, an agent of its parent inter

national union. In the leading decision in United Mine Workers

v. Coronado Coal Co., supra, an action under the Sherman Anti-

Trust Act against an international union, several local unions,

and various individuals was taken. Noting that it was faced

with a question of the agency of the local unions to act for the

international union, the Supreme Court examined the union con

stitution and determined that no such agency existed and that

the motion of the international union for a directed verdict

should have been granted. Coronado Coal Co., 259 U.S. at 395-96.

See also Coronado Coal Co. v. United Mine Workers, 268 U.S. 295,

304-05 (1925).

The fact that local unions are separate entities from their

parent international organizations was recognized by this Court

in United Construction Workers v. Iiaislip Baking Co., 223 F. 2d

872 (CA 4, 1955), cert. denied 350 U.S. 847 (1955), a suit under

Sec. 301(a) of the Labor Management Relations Act, 29 USC Sec.

185(a), to recover damages for the alleged breach of a collective

bargaining agreement.

Likewise, the National Labor Relations Board, the agency

most familiar with the operations of labor organizations, has

consistently ruled that, except in cases where an international

union's constitution grants it substantial control over its af

filiated local unions, each local union is a separate entity, and

therefore, the parent international union is not responsible for

the unlawful conduct of the local without a specific showing of

some agency or participation by the international union. In Inter-

11,

-14

national Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (Franklin Electric

Construction Co.), 121 NLRB 143, 42 LRRM 130] (1958), the Board

refused to find a violation by an international union since the

local union which engaged in a secondary boycott was a legal en

tity in itself, stating:

"The overwhelming weight of judicial authority,

including the Supreme Court of the United States, is

that a local union is a legal entity apart from its

international and that it is not a mere branch or arm

of the latter. That too has been the position of the

Board.

* * *

"An international union's constitution regulates

and controls the operations of its constitutent locals.

But that regulation is rarely so complete as to make

the local merely a branch of the international. 'In

the main these provisions (of international's consti

tution and local's by-laws) delineate the jurisdiction

of the confederation and the affiliated units with ref

erence to collective bargaining, membership and discip

line, assessments for the common cause, participation

of the local units in the affairs of the association,

and the regulation of the locals . . . . These provi-

sions lay restraints upon the activities of the local

union, but they do not deny its separate existence and

make of its a mere "administrative arm" of National'."

See also Local No. P-575, Amalgamated Meat Cutters (Iowa

Beef Packers, Inc,,), 188 NLRB 5, 6, 76 LRRM 1273 (1971).

In numerous contexts, the courts have held that local unions

are not the agents of their parent international organizations.

For example, officers of local unions are not agents of inter

national unions for receipt of service of process. See, e .g .,

Gray v. Asbestos Workers, Local 51, 416 F. 2d 313 (CA 6, 1969);

Morgan Drive-A-Way, Inc, v. Teamsters, 268 F. 2d 871 (CA 7, 1959)£ert.

denied, 361 U.S. 896 (1959); Barefoot v. International Brother

hood of Teamsters, 424 F. 2d 1001 (CA 10, 1970).

Many Courts in actions brought under Title VII have dismissed

-tr ......."W i w w r w " f g - - "

•15-

rt *

international or other labor organizations superior to local

unions when the local, but not the parent organization, was

named in the charge filed with the EEOC. See e .g ., Lo Beau v.

Libbey-Owens-Ford Company, 484 F. 2d 798 (CA 7, 1973); Jamison

v . Olga Coal Co., 335 F. Supp. 454 (S.D. W. Va . , 1971); Butler

v. Local 4 and Local 269, Laborers' International Union , 308 F .

Supp. 528 (N.D. 111. 1969); Moody v. Albermarle Paper Co., 271

F. Supp. 27 (E.D. N.C., 1967). In Jamison and Butler, the Courts

specifically rejected the plaintiff's claim that it should be

relieved of the requirement of naming the international union in

the charge filed with the EEOC since the local was named. Plain

tiff's agency argument was rejected.

Finally, it is submitted that important policy considerations

underlay the necessity for preserving the present law of agency

as it relates to international-local union relationships. In

United Mine Workers v. Gibbs, 383 U.S. 715, 738, 739 (1966), the

Court set forth the proposition that national labor policy --

whether in a Norris-LaGuardia or National Labor Relations Act

context — encourages international unions to conduct normal

union functions even in explosive situations. In order that par

ent organizations would not be "chilled" in exercising their re

straining and mediating influences, the Court recognized that

"it would be inconsistent with national labor policy to infer

ratification" of a local union's activities from the mediating

efforts of its international. However, the Court further recog

nized that this beneficial and salutary international presence woulc

be unlikely if the parent union were required to repudiate or dis

avow the acts of its local. Accord, United Mine Workers (Blue

Diamond Coal Co.), 143 NLRB 795, 797, 798 (1963).

— M m — 1 l’» 1 D. m w > U w n ww m M T ......... T *"~

-16-

This is precisely the rationale of this Court as shown in

its decision in Associated Builders v. NLRB, unpublished decision

listed in table at 532 F. 2d 749 (No. 75-1716, January 27, 1976),

78 L C Para. 11,312, For the convenience of the Court a copy

of the Associated Builders decision is reproduced at the back of

this brief. Agreeing with the above-stated rationale of the

National Labor Relations Board, and citing the Board's 1958

Franklin Electric decision, this Court in Associated Builders-

found that "the International Union did not have knowledge of the

unlawful activities of the two Locals and that it did not autho

rize or ratify them. Legally, the relationship between the Inter

national Union and the Locals was not such that the conduct of

the Locals should be attributed to the International short of

knowledge, authorization or ratification."

In the case at bar, the Local Union's supposed wrongful

failure to advise its membership of a long-standing, non-discrimi

nation employment policy applicable to the membership, of which

the membership supposedly was unaware pursuant to the novel theory

of the District Court, can not be attributed to the International

Union short of knowledge, authorization, or ratification. The

record below is devoid of any evidence thereof, and the District

Court should have granted the International Union's motion to

dismiss.

I " " ' .......... .............. ....... — --- -

-3 7-

Conclus ion

The District Court's finding of International Union lia

bility is clearly erroneous for the following reasons:

1. For the reasons that the District Court's finding of

Local Union liability is clearly erroneous;

2. Further, because the International Union was not the

collective bargaining agent for the plaintiffs or the class

they represent, the Local Union being the exclusive collective

bargaining agent; and

3. The Local Union was not the agent of the International

Union; further, the supposed omission (failure to advise member

ship) of the Local Union, upon which the District Court theorized

Local Union liability, was not attributable to the International

Union.

Jay J. Levit

STALLARD & LEVIT

2120 Cen. Natl. Bank Bldg.

Richmond, VA 23219

James F. Carroll

1120 Connecticut Ave., N.W.

Suite 940

Washington, D.C. 20036

Counsel for Tobacco Workers'

International Union

Respectfully submitted

TOBACCO WORKERS' INTERNATIONAL

UNION

Cbunsel

-- ’— 1 -r’- r.

-18-

CERTIFICATE

In accordance with Rule 25 of the Rules of the U.S. Court

of Appeals, Fourth Circuit, I hereby certify that I have this

15th day of December, 1976, filed the required copies of the

Brief of Appellant Tobacco Workers' International Union in the

Clerk’s office, and have served the required copies of the said

brief on Lewis T. Booker, Esq., Company counsel, 707 E. Main Street

P. 0. Box 1535, Richmond, Virginia 23212; and Plaintiffs' counsel,

Henry L. Marsh, III, Esq., 214 East Clay Street, P. 0. Box 27363,

Richmond, Virginia 23261.

Jay J . Levit

▼"I. -

ASSOCIATED BUIi,' ERS v. NLRB

U.S. Court of Appeals,

(Richmond)

ASSOCIATED BUILDERS AND

CONTRACTORS, INC. v. NATIONAL

LABOR RELATIONS BOARD and

LABORERS’ INTERNATIONAL UN

ION OF NORTH AMERICA, AFL-CIO,

Intervenor, No. 75-1716, January 27,

1976

LABOR MANAGEMENT RELATIONS

ACT

—Restra in t or coercion — Unlaw

ful conduct of local unions — Re-

_spons^U ^tv of in ternational iTHTSTT

NLRB held warran ted in not hold

ing international union jointly re

spond Me with two local unions for

their coercive picketing activities in

violation of Section 8 1 b > 11' < A) of

LMRA, since (1) in ternational did not

have knowledge of locals’ unlawful

activities and it did not authorize or

ra tifv them; and (2) relationship

between International and its locals is

not such th a t locals’ conduct should

lie a ttr ibu ted to international short of

knowledge, authorization, or ra t if ica

tion

Petition for review' of an NLRB

order (90 LRRM 1126, 219 NLRB No.

23' Dismissed

N. Pete: i.areau (A. Samuel Cook,

Joseph H Kaplan and Venable.

Baetjet. and Howard, on briefs),

Baitimoie, Md., for petitioner associa

tion

Robert G. Sewell (John C. Miller,

Acting General Counsel, John S. I rv

ing, Deputy General Counsel, Elliott

Moore, Deputy Associate General

Counsel, and Thomas A. Woodley,

with him on brief), for respondent

NLRB.

Arthur M Schiliei (Robert J. Con

tie; (on, Jules Bernstein, and T heo

dore T. Green, on brief), Washington.

D C . for intervenor union

Before WINTER, CRAVEN, and

BurZNER, Circuit Judges,

91 L R R M 25G0

Full Text of Opinion

PER CURIAM:—Associated Build

ers and Contractors, Inc. seeks to set

aside the Board's order declining to

find responsibility on the p a r t of L a

borers' In te rna tiona l Union of North

America, AFL-CIO, for the coercive

picketing activities of two local u n

ions found to be In violation of 5 8

(b)(1)(A) of the Act.

From our review of the record and

a f te r hear ing argum ent and consid

ering the briefs, we conclude th a t the

B oard’s order is unassailable and the

petition to set it aside should be dis

missed. There is substantial evidence

to support the Board's factual de

term ination th a t the In te rna tiona l

Union did not have knowledge of the

unlawful activities of the two locals

an d th a t it did no t authorize or ra tify

them. Legally, the relationship be

tween the In te rna tiona l Union and the

locals was not such th a t the conduct

of the locals should be a ttr ibu ted to

the In te rna tiona l short of knowl

edge, authorization or ratification. See

I.B.E.W. (Franklin Electric), 121

NLRB 143, 42 LRRM 1301 (1958),

PETITION DISMISSED.