Brown v. A. J. Gerrard Manufacturing Co. Brief of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

May 6, 1983

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v. A. J. Gerrard Manufacturing Co. Brief of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund as Amicus Curiae, 1983. f32374c3-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0c491ad4-8cbf-43d3-b405-f6a363fd2a96/brown-v-a-j-gerrard-manufacturing-co-brief-of-the-naacp-legal-defense-and-educational-fund-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

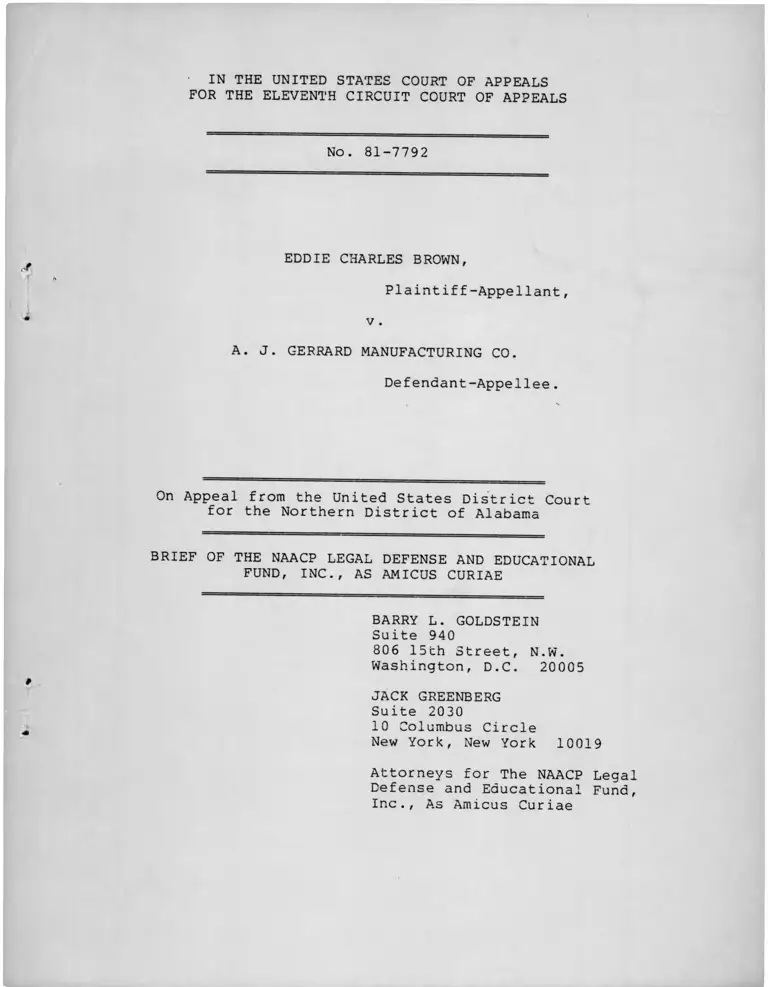

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT COURT OF APPEALS

No. 81-7792

EDDIE CHARLES BROWN,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v .

A. J. GERRARD MANUFACTURING CO.

Defendant-Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States District Court for the Northern District of Alabama

BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC., AS AMICUS CURIAE

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN Suite 940

806 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

JACK GREENBERG

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for The NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., As Amicus Curiae

CERTIFICATE REQUIRED BY LOCAL RULE 13(a)

The undersigned counsel of record for the plaintiff-appellant

certifies that the following listed persons have an inerest in the

outcome of this case. These representations are made in order that

the judges of this Court may evaluate possible disqualifications or

recusal pursuant to local Rule 13(a):

1. Eddie Charles Brown, plaintiff.

2. A. J. Gerrard Manufacturing

Company, defendant

3. NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., amicus curiae.

Attorney For AMICUS CURIAE

t

l

Page

i

i ii

1

4

4

4

6

12

16

INDEX

Certificate Required by Local Rule 13(a)

Table of Authorities

STATEMENT OF INTEREST

ARGUMENT

As a Victim of the Company's Discriminatory

Discharge, Plaintiff Brown Is Entitled to

Receive as Back Pay All Wages Which He Lost

as a Result of the Company's Discrimination;

As a Lawbreaker the Company May Not Have the

Government Benefit, Unemployment Compensation, Received by Brown Used to Reduce its Leqal Liability.

A. Issue and Factual Statement.

B. The Language of Title VII and the

the Legislative History Bar the

Deduction of Unemployment Compen

sation in the Calculation of an Award of Back Pay.

C. The Deduction of Unemployment

Compensation Benefits from Back

Pay Awards Conflicts with the

Principles for Application of

Title VII Established by the Courts.

CONCLUSION

Attachment A: "Significant Provisionsof State Laws (July 6, 1980), Appendix

13.4 to National Commission on Unemploy

ment Compensation, Unemployment Compen- sation; Final Report (1980) .

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

/

w«

$

Cases :

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975)....

Bernard v. Gulf Oil Co., 619 F.2d 459 (5th Cir. 1980) (en banc), aff'd, 452 U.S. 89 (1981 )..............

Bernard v. Gulf Oil Co., 452 U.S. 89 (1981).........

Brown v. A. J. Gerrard Mfg. Co., 643 F .2d 273(5th Cir. 1981).................................

Brown v. A. J. Gerrard Manufacturing Co., 695 F.2d

1290 (11th Cir. 1983) (rehear, en banc granted)....

Brown v. Bd. of Education, 347 U.S. 438 (1954)......

EEOC v. Ford Motor Company, 645 F .2d 183 (4th Cir.

1981), rev1d on other grounds, 50 USLW 4937 (1982).

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976)....................................

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971).......

James v. Stockham Valves & Fittings, Inc., 559 F .2d

310 (5th Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1034 (1978).............. ......7 7 7 :—

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire Co., 491 F .2d 1364 (5th Cir. 1974)...........................

Kauffman v. Sidereal Corp., 695 F.2d 343 (9th Cir .

Marks v. Prattco, Inc., 607 F .2d 1153 (5th Cir. 1979)

Marshall Field & Co. v. NLRB, 318 U.S. 253 (1943)___

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973)

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 426 F.2d 534 (1970)...................................

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963)...........

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. v.

Campbell, 504 F.Supp. 1365 (D.D.C. 1981)..........

Pages :

2-3, 7,

12-13, 16

1

1

4

7

2

7-8, 16

2

2

2, 13

2, 8, 12, 14

8, 16

13

11

7

1

1

i i i

2

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (Continued)

Cases :

NLRB v. Gullett Gin Co., 340 U.S. 361 (1951)....... .

Northcross v. Board of Ed., 611 F .2d 624 (6th Cir.

1979), cert, denied, 447 U.S. 911 (1980)...... !...

Parson v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp.,575 F . 2d 1374 (1978)..............................

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F 2d 211 (5th Cir. 1974)....................................

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948)...............

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977).....

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d 906 (5th Cir. 1973)..................................

United States v. N. L. Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d 354 (8th Cir. 1973)...............................

United States v. United States Steel Corporation,

520 F .2d 1043 (5th Cir. 1975), cert, denied,

429 U.S. 817 (1976)........... 77777 .777777___

Statutes and other authorities:

National Labor Relations Act, 29 U.S.C. §§151 et seq.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (as amended 1972), 42 U.S.C. §§2000e et seq...................

J * (198^ & P * Nutman' Understanding the Unemployed

National Commission on Unemployment Compensation,

Unemployment Compensation: Final Report (1980).__

« Note, The Deduction of Unemployment Compensation

for Back-Pay Awards Under Title VII, 16 U. Mich.J. L. Ref. ______. (Issue 3, 1983) (To bepublished)...............................

United States Unemployment Insurance Service, Depart

ment of Labor, Comparison of State Unemployment Insurance Law. §§220.01-04............ ............

110 Cong. Rec. 7214 (1964)..................

iv

Pages :

8-11, 15

1-2

13

2 , 6 , 8 , 12

2

7

2 , 8 , 12

13

2

passim

passim

14

9-11, 14-15,

Attachment A

6

7

11

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT COURT OF APPEALS

No. 81-7792

EDDIE CHARLES BROWN,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v .

A. J. GERRARD MANUFACTURING CO.

Defendant-Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States District Court for the Northern District of Alabama

BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC., AS AMICUS CURIAE

STATEMENT OF INTEREST

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., is a

nonprofit corporation whose principal purpose is to secure the

civil and constitutional rights of black persons through litiga

tion and education. The NAACP Legal Defense Fund has been praised

for its legal work in support of civil and constitutional rights

by the Supreme Court, N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 421-22

(1963) ( Defense Fund lawyers [have] a corporate reputation for

expertness in presenting and arguing the difficult questions of

law that frequently arise in civil rights litigation"), by the

Fifth Circuit, Bernard v. Gulf Oil Co., 619 F.2d 459, 470 (1980)

(en banc), affM, 452 U.S. 89 (1981), Miller v. Amusement Enter

prises, Inc., 426 F .2d 534, 539 n.14 (1970), and by other courts,

e • 9 • • Northcross v. Board of Ed., 611 F.2d 624, 637

(6th Cir. 1979), cert, denied, 447 U.S. 911 (1980), NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc, v. Campbell., 504 F.Supp. 1365,

1368 (D.D.C. 1981) .

Legal Defense Fund lawyers have been counsel in many landmark

cases establishing basic constitutional and statutory rights for

black Americans. See, e.g., Brown v. Bd. of Education, 347 U.S.

438 (1954); Shelley v . Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948). Moreover,

Legal Defense Fund lawyers have been counsel in many of the cases

establishing the basic principles of fair employment law. See,

§■•9-' 21199s v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971); Albemarle

Co- v - Moody> 422 U.S. 405 (1975), Franks v. Bowman Transpor

tation Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976). In particular, Legal Defense

Fund lawyers have been counsel in cases establishing fundamental

principles for application of the back pay remedy in the Supreme

Court, Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody, supra, and in the Fifth

Circuit, see, e.g., United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d

906 (1973), Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491 F.2d 1364

(1974) ; Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211 (1974),

United States v. United States Steel Corporation, 520 F.2d 1043

(1975) , cert, denied, 429 U.S. 817 (1976), James v. Stockham

Valves & Fittings, Inc., 559 F.2d 310 (1977), cert. denied,

434 U.S. 1034 (1978) .

Amicus believes that the Court's decision in the case at bar

may affect its representation of minorities in future cases.

Amicus further believes that its experience in employment litiga

tion will assist the Court in this case.

2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The district court without stating any reason reduced the

back pay liability of the defendant Company by more than one-

third by deducting from the back pay award the unemployment

compensation benefits received by the victim of the Company's

illegal racial discrimination.

The plain meaning of Title VII precludes the deduction of

unemployment benefits from back pay awards. Moreover, the legis

lative history makes clear that the Title VII provision was

modeled upon the back pay provision of the National Labor Relations

Act and that decisions under that Act are entitled to "great

weight." The Supreme Court has stated that unemployment compen

sation benefits received by the victims of unfair labor practices

should not be deducted from their back pay awards. The same rule

should apply to Title VII.

The deduction of unemployment compensation benefits from

back pay awards conflicts with the law of this Circuit that

Title VII should be given a "wide scope ... in order to remedy, as

much as possible, the plight of persons who have suffered from

discrimination...." Finally, the deduction of unemployment compen

sation benefits undercuts the achievement of the purposes of

I'itle VII as set forth by the Supreme Court in Albemarle Paper

Company v . Moody.

3

ARGUMENT

AS A VICTIM OF THE COMPANY'S DISCRIMINATORY DISCHARGE,

PLAINTIFF BROWN IS ENTITLED TO RECEIVE AS BACK PAY ALL

WAGES WHICH HE LOST AS A RESULT OF THE COMPANY'S

DISCRIMINATION; AS A LAWBREAKER THE COMPANY MAY NOT

HAVE THE GOVERNMET BENEFIT, UNEMPLOYMENT COMPENSATION,

RECEIVED BY BROWN USED TO REDUCE ITS LEGAL LIABILITY.

A . Issue and Factual Statement.

Seven weeks after he was hired by the Company plaintiff

Brown, a black worker, was injured on the job. He was examined

by a physician who found evidence of a concussion. The physician

excused Brown from work for one week. Brown returned to work a

day early but was promptly fired by a Company foreman allegedly

because he failed to advise the Company of his status. Brown was

not given any warning by the Company; he was peremptorily fired.

"Uncontroverted evidence showed numerous instances in which white

employees were given extensive warnings for precisely [the conduct

for which the Company fired Brown]: failing to show up for work,

for extended periods, without prior notice by the employee."

Brown v. A. J. Gerrard Mfg. Co., 643 F.2d 273, 276 (5th Cir. 1981).

Brown was the victim of racial discrimination; he received different

and much harsher treatment because he was black.

Having determined that Brown was discharged illegally, the

Court remanded the case to the district court for a determination

of appropriate attorneys' fees and back pay. ^d. The issue of

attorneys' fees is not before the Court.

The essential facts concerning back pay are not in dispute.

Mr. Brown was unemployed for 34 weeks after he was discriminatorily

4

discharged and before he was hired as a regular employee by

another Company. The district court determined that he lost

$2,930 in wages during this period. " [l]n its discretion" but

without giving any reason, the district court reduced the

plaintiff s actual loss for amounts received as unemployment

compensation." Opinion, August 26, 1981. Since the plaintiff

had received $962 in unemployment compensation, the district

court reduced the lost wages, $2,930, to $1,968. The lower

court then calculated 7% simple interest—^ and concluded that

Mr. Brown was owed $3,074.67.

The issue before this Court is whether the district court

had discretion to reduce the award by approximately one-third

by deducting from the back pay the money paid through an Alabama

unemployment compensation program. Alternatively, to state the

issue from the perspective of the Company, did the district court

properly provide the Company a "windfall" by reducing its back

pay liability by one-third because the State of Alabama paid

Mr. Brown unemployment compensation

_1/ The plaintiff had requested a rate of 8% compounded annually.

The plaintiff argued that this rate "is justified because of the sub

stantial amount of inflation that has occurred since the plaintiff

was denied wages in 1972 and early 1973." Motion for Entry of Judg

ment. The plaintiff did not appeal from the district court's application of 7% simple interest.

2/ The bottom-line view of the Company's "windfall" is dramatic

Mr. Brown lost $2,930 in 1972 and 1973 dollars because of the Company's

invidious discrimination. In 1981 when the district court rendered

its decision $1.97 was required to buy consumer goods that cost $1.00

in 1972. Motion for Judgment. Accordingly, Mr. Brown's award of

$3,074.67 was worth $1,568.08 in 1972 dollars. Thus the Company had

to pay Mr. Brown in constant dollars only slightly more than one-half

of the amount which ne lost due to the Company's discrimination.

5

B .

A

The Language of Title VII and the Leqislative Historv

Bar the Deduction of Unemployment CoiiinpnsaHnn in

Calculation of an Award of Back Pay .j/' ~

The relevant provision of Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 (as amended 1972), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(g) reads in

pertinent part:

If the court finds that the respondent has

engaged in ... an unlawful employment

practice ... the court may ... order such

affirmative action as may be appropriate,

which may include ... back pay.__ Interim

earnings or amounts earnable with reasonable

-*-9ence by the person or persons discriminated against shall operate to reduce the

back pay otherwise allowable.

Back pay" includes not only "straight salary" lost as a

result of the unlawful practice but also "[i]nterest, overtime,

shift differentials, and fringe benefits---" Pettway v. Ameri

can Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d, at 263. The statute provides

for only two deductions from back pay — "interim earnings" and

"amounts earnable with reasonable diligence."

Of course, the Congress could have included "unemployment

compensation" or other government benefits among those items to

be deducted from back pay. However, Congress did not include

unemployment compensation as an item to be deducted from back pay.

There is no support in the statutory language for the deduction of

unemployment compensation from back pay. In enacting Title VII,

Congress had a far-reaching public policy: "The language of

Title VII makes plain the purpose of Congress to assure equality

of employment opportunities and to eliminate those discriminatory

„Sef generally, Note, The Deduction of Unemployment Comoensatinn for Back-Pay Awards Under Title VII, 16 uT Mich. J L Rif' pen5atl°n

(TO bi-pubTTshedT7~ The Journ ha agreed't^iiSTThe final draft to counsel for all parties.

6

practices and devices which have fostered racially stratified job

environments to the disadvantage of minority citizens...."

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 u.S. 792, 800 (1973). in

applying a statute with a broad congressional purpose the courts

should not unnecessarily create limitations to the application of

the statute.

The legislative history of Title VII supports the plain

meaning of the statute — unemployment compensation may not be

deducted from back pay. See e.g., Brown v. A. J. Gerrard Manu

facturing Co., 695 F .2d 1290 (11th Cir . 1983) (rehear, en banc

granted); EEOC v. Ford Motor Company, 645 F.2d 183 (4th Cir. 1981),

rev on other grounds, 50 USLW 4937 (1982).

The Title VII back pay provision "was expressly modeled on

the backpay provision of the National Labor Relations Act."

(Footnote omitted). Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405,

4 /419 (1975).- Moreover, as the Fifth Circuit has ruled, since

1

— / t*le Supreme Court stated, "[t]he framers of Title VII stated

!rafc Were using the NLRA provision as a model." Albemarle PaperCo_̂ , 422 U.S., at 419 n.ll. The "bipartisan captains," Senators ̂

Clark and Case, responsible for Title VII during the Senate debate

placed an interpretative memorandum in the Congressional Record.

The Supreme Court has determined that the comments in this document

are authoritative indications of [conqressional] purpose." Team

sters v United States, 431 U.S. 324, 352 (1977). The interpFetative memorandum states that

[t]he relief sought in such suits would be

an injunction against future acts or prac

tices of discrimination, but the court

could order appropriate affirmative relief,

such as hiring or reinstatement ... and the

payment of back pay. This relief is similar

to that available under the National Labor

Relations Act in connection with unfair labor practices ....

110 Cong. Rec. 7 214 (1964).

7

" [t]he relief provisions in Title VII were modeled after a

similar provision in the National Labor Relations Act ... great

weight should be given to interpretations under the latter act."

(Emphasis added). Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.,

491 F.2d, at 1377 n.37; see also Pettway v. American Cast Iron

Pipe Co., 494 F.2d, at 252; United States v. Georgia Power Co.,

474 F . 2d, at 921 n.19.

As set forth in the panel opinion, 695 F .2d, at 1292, the

leading case interpreting the application of back pay under the

National Labor Relations Act is NLRB v. Gullett Gin Co.. 340 U.S.

361 (1951). As the panel decision determined and as two other

Circuits agree, the authoritative decision in Gullett Gin and

Congress' intent to apply NLRA law to Title VII make clear that

"unemployment benefits received by a successful plaintiff in

an employment discrimination action are not offsets against a

backpay award." (Footnote omitted). Kauffman v. Sidereal Corp..

695 F.2d 343, 347 (9th Cir. 1982); see EEOC v. Ford Motor Co.,

supra.

The specific issue presented in Gullett Gin was whether the

NLRB had abused its discretion in refusing to order that the

amounts received as unemployment compensation be deducted from a

back pay award. However, the Supreme Court rejects unequivocally

the arguments that have been advanced to support the discretionary

deduction of unemployment compensation benefits from back pay

awards. First, the Court dismisses the argument that the failure

to deduct unemployment benefits would overcompensate the victim

of the illegal act:

8

To decline to deduct state unemployment

compensation benefits in computing back

pay is not to make the employees more

than whole .... Since no consideration

has been given or should be given to

collateral losses in framing an order

to reimburse employees for their lost

earnings, manifestly no consideration

need be given to collateral benefits

which employees may have received.

(Emphasis in original).

Gullett Gin Co., 340 U.S., at 364. Under Title VII as under

the NLRA the victim of an illegal act may not claim recovery

for a "collateral loss" resulting from a discriminatory discharge

~ for example, from the repossession of a car or furniture or

from the foreclosure on a mortgage resulting from the loss of

regular earnings. Thus, as the Supreme Court states, "manifestly

no consideration need be given to collateral benefits...."

(Emphasis added), Id.

Second, the Court dismisses the theory that unemployment

compensation benefits are not collateral but direct benefits.

With this theory we are unable to agree.

Payments of unemployment compensation

were not made to the employees by

respondent but by the state out of

state funds derived from taxation.

True, these taxes were paid by

employers, and thus to some extent

respondent helped to create the fund.

However, the payments to the employees

were not made to discharge any liability

or obligation of respondent, but to

carry out a policy of social betterment

for the benefit of the entire state.

Gullett Gin Co., 340 U.S., at 364. Moreover, in Alabama, as well

as in Alaska and New Jersey, the unemployment insurance taxes are

levied on employees as well as on employers. National Commission on

9

Unemployment Compensation, Unemployment Compensation: Final

Report (1980), p.18.-^

Third, the Court rejects the argument that the failure to

deduct unemployment compensation imposes a "penalty" upon the

employer .

[The employer] urges that the Board's

order imposes ... a penalty which is

beyond the remedial powers of the

Board because, to the extent that

unemployment compensation benefits

were paid to its discharged employees,

operation of the experience-rating record formula ... will prevent

respondent from qualifying for a

lower tax rate. We doubt that the

validity of a back-pay order ought

to hinge on the myriad provisions of

state unemployment laws. However,

even if the ... law has the conse

quence stated ... this consequence

does not take the order without the

discretion of the Board to enter.

We deem the described injury to be

merely an incidental effect of an

order which in other respects

effectuates the policies of the

federal Act. It should be empha

sized that any failure of respondent to qualify for a lower tax rate

would not be primarily the result of

federal but of state law, designed

to effectuate a public policy with

which it is not the Board's function to concern itself.

Gullett Gin Co., 340 U.S., at 365. The state unemployment laws are

indeed "myriad." Unemployment Compensation; Final Report, supra,

5/ The cost of unemployment insurance taxes represents a labor

cost to the employer and an insurance cost to the employees. The

employee must forego higher current wages for the benefits afforded

by unemployment insurance. In effect, the employees pay indirectly

for the unemployment benefits even in states where the employers

pay all of the taxes for unemployment insurance by means of a oav- roll tax. ^ 1

10

at Appendix 13.4: "Significant Provisions of State Laws"(July 6,

1980) (Attachment A hereto). The experience-rating methods vary

widely among the states. Some states base the rating upon benefit

disbursements charged to individual employers, other states

measure the experience-rating by declines in the employer's pay

roll. United States Unemployment Insurance Service, Department

of Labor, Comparison of State Unemployment Insurance Law,

§§220.01-.04 . Moreover, if an employer pays the maximum tax rate,

which varies among the states, then additional benefit claims will

not affect his rating. The implementation of the single national

policy of ending employment discrimination should not depend upon

the peculiarities of the various state statutory schemes for pro

viding unemployment insurance.

Fourth, the Court approves its prior opinion, Marshall Field

k-Co• v * NLRB, 318 U.S. 253 (1943), which "held that the benefits

received by employees under a state unemployment compensation act

were plainly not earnings which, under the Board's order in that

case, could be deducted from the back pay awarded." Gullett Gin

Co., 340 U.S., at 363.

The decision in Gullett Gin Co. makes clear that there is

no basis for deducting unemployment compensation benefits from

Title VII back pay awards. It is contrary to the intent of Congress

to leave in place a legal standard that permits the deduction of

unemployment benefits from back pay due to Brown because he was

the victim of racial discrimination whereas there would be no

such deduction if Brown was the victim of an unfair labor practice.

11

C . The Deduction of Unemployment Compensation Benefits

from Back Pay Awards Conflicts with the Principles

for the Application of Title VII Established by the Courts.

This Court has long recognized the critical role that the

back pay remedy plays in implementing the fair employment laws:

where employment discrimination has been

clearly demonstrated ... victims of that

discrimination must be compensated if

financial loss can be established.

.... To implement the purposes behind

Title VII, a court should give "a wide

scope to the act in order to remedy, as

much as possible, the plight of persons

who have suffered from discrimination

in employment opportunities."

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491 F . 2d at 1375; United

States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d, at 921. Accordingly, the

Fifth Circuit provided that " [ojnce a court has determined

that a plaintiff or complaining class has sustained economic

loss from a discriminatory employment practice, back pay should

normally be awarded unless special circumstances are present."

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d, at 252-53.

Subsequent to these Fifth Circuit decisions which were criti

cal to the development of fair employment law, the Supreme Court

addressed the back pay issue. The Supreme Court's approach was

similar to the approach taken by the Fifth Circuit. The Court

stated the "obvious connection" between back pay and the purpose

of Title VII "to achieve equality of employment opportunity."

Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody, 422 U.S., at 417.

If employers faced only the prospect of an

injunctive order, they would have little

incentive to shun practices of dubious

legality. It is the reasonably certain

prospect of a backpay award that "provide [s]

12

the spur or catalyst which causes employers

and unions to self-examine and to self-

evaluate their employment practices and

to endeavor to eliminate, so far as possible,

the last vestiges of an unfortunate and

ignominious page in this country's history."

Id., at 417-18, quoting United States v. N. L. Industries, Inc.,

479 F.2d 354, 379 (8th Cir. 1973). The Court also stated that

it is "the purpose of Title VII to make persons whole for

injuries suffered on account of unlawful employment discrimi

nation." Albemarle Paper Company, 422 U.S., at 418. The Court

adopted the following standard:

... given a finding of unlawful discrimina

tion, backpay should be denied only for

reasons which, if applied generally, would

not frustrate the central statutory pur

poses of eradicating discrimination

throughout the economy and making persons

whole for injuries suffered through past

discrimination. (Footnote omitted).

Id. , at 421 .

After Albemarle Paper Company, the Fifth Circuit has con

tinued to hold that unless special circumstances are present

back pay should normally be awarded if a plaintiff has sustained

economic loss from a discriminatory practice. See e.g., Marks v.

Pr attco, Inc., 607 F.2d 1153, 1155 (1979); Parson v. Kaiser

Aluminum & Chemical Corp., 575 F.2d 1374, 1391 (1978); James v.

Stockham Valves & Fittings, Inc., 559 F. 2d, at 357.

There are no "special circumstances" which would justify the

denial of back pay or the partial denial of back pay by means of

the deduction of unemployment compensation benefits. A general rule

permitting the deduction of unemployment compensation benefits from

back pay is inconsistent with the long-established principle of

13

the Fifth Circuit to give "a wide scope" to the remedy of back

pay "in order to remedy, as much as possible, the plight of per

sons who have suffered from discrimination in employment oppor

tunities." Johnson, 491 F.2d, at 1375. A general rule permit

ting the deduction of unemployment benefits from back pay is also

inconsistent with each of the two purposes of back pay, "make

whole" and "prophylactic," described by the Supreme Court.

Unemployment compensation does not substitute for lost wages.

The $37 per week which Mr. Brown received in unemployment compen

sation accounted for approximately 40% of his lost weekly wage.

This proportion is consistent with the nation-wide average.

Unemployment Compensation - Final Report, supra, p.16. For the

unemployed, financial responsibilities — family expenses, rent,

car payments — remain constant, but available incoming resources

even with unemployment compensation fall sharply. Moreover,

unemployment compensation, as was the case for Mr. Brown, may

stop weeks or months before new employment is obtained. The

drain on the substantially reduced resources may cause default

on payments and additional financial loss, and frequently results

in severe anxiety and family strain. See generally, J. Hayes &

P. Nutman, Understanding the Unemployed, pp.64-82 (1981) (Describ

ing evidence of deterioration in mental and physical health as a

result of unemployment).

Neither Mr. Brown nor any other Title VII plaintiff may

recover under Title VII for these losses, pain and suffering. The

victim of a tort or a contract violation which causes him to lose

his job might recover in an action at law for losses flowing from

unemployment. But the victim of racial discrimination is limited

14

to the equitable monetary remedy provided by Title VII and may

not so recover. Unemployment compensation does not replace lost

wages, it "is an insurance system, created to provide adequate

benefits to tide workers over temporary periods of unemploy

ment---," Unemployment Compensation - Final Report, supra, p.14.

It is, as the Supreme Court stated in Gullett Gin Co., "a policy

of social betterment for the benefit of the entire state."

340 U.S., at 364.

It is anomalous for courts to deduct unemployment compensation

from back pay recovery in order to prevent excess recovery since

Title VII does not allow a plaintiff to recover all losses result

ing from sudden unemployment. To permit the deduction of unemploy

ment compensation would prevent the adequate compensation, "as much

as possible," of discrimination victims, and thwart a basic purpose

of Title VII.

In this case the deduction of unemployment compensation from

the back pay remedy reduced the liability of the defendant by

more than one-third. See p.5, supra. In fact, this deduction

combined with the delay in payment and the low interest rate

resulted in the defendant Company paying Mr. Brown in constant

dollars approximately one-half of the amount of the earnings which

Mr. Brown lost due to the Company's discrimination. See p.5 n.2,

supra. The deduction of unemployment compensation from back pay

may often, as here, significantly reduce the amount of back pay.

Thus, this deduction serves to lessen the effectiveness of the

remedy to "provide the spur or catalyst which causes employers" to

correct and eliminate discriminatory practices and to frustrate

15

the second fundamental purpose of Title VII.—^

CONCLUSION

The deduction of unemployment compensation from back pay

awards violates the fundamental "make whole" and "prophylactic"

purposes of Title VII. There is no reasoned basis for the

exercise of discretion to deduct unemployment compensation.

# Important national goals would be frus

trated by a regime of discretion that

"produce]d] different results for

breaches of duty in situations that

cannot be differentiated in policy."

Albemarle Paper Company, 422 U.S., at 417. This Court should adopt

the rule followed by the Fourth (EEOC v. Ford Motor Co.) and the

Ninth (Kauffman v. Sidereal) Circuits which precludes :the;deduction

— / ^ likely that in many states and in many circumstances the

payment of additional unemployment compensation benefits will not

even increase a company's payroll tax for unemployment insurance.See p.ll, supra .

7/ Alternatively, the decision of the district court should be revers

because the court did not properly exercise its discretion "in light of

the large objectives" of Title VII. Albemarle Paper Co., 422 U.S.. at

416. Moreover, the district court gave no reason for p’ar tially ’deny inq

the back pay requested. "it is necessary ... that if a district court

does decline to award backpay, it carefully articulate its reasons." Id., at 421 n . 1 4 .

of unemployment compensation from back pay awards

Respectfully submitted,

BAI

Suite 940

806 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005 (202) 638-3278

JACK GREENBERGSuite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

16

ATTACHMENT A

Appendix 13.4: Significant Provisions of State Laws (July 6, 1980)

U S D E P A R T M E N T O F L A B O R

V

E M P L O Y M E N T A N D T R A IN IN G A D M IN IS T R A T IO N

Unem ploym ent Insurance Service

’.W

Signif icant Provisions of State U n e m p lo ym en t Insurance Laws, JULY 6, 1980

PREPARED FOR READY REFERENCE. CONSULT THE STATE LAW AND STATE EMPLOYMENT SECURITY AGENCY FOR AUTHORITATIVE INFORMATION

BENEFITS

- ------

COVERAGE

r

TAXES

Duration in

52-week period

Size of

firm (1

worker in

specified

time and/

or size of

payroll6

State

Qualifying

wage or

employment

(number x

wba or as

indicated)*

Waiting

week2

Computation

of wba

(fraction of

hqw or as

indicated) '

Wba for

total unem

ployment ̂

Earnings

disre-

garded^

Proportion

of base-

period

wages^

Benefit

weeks for

total un

employment^

1979 Tax

rates (per

cent of awages)

Min. Max. Min? Max. Min. Max.

Ala. 1-1/2 x hqw;

not less

than $522.01

0 1/24 $15 S90 $6 1/3 11 + 26 20 weeks 91.0 94.0

Alaska $750; $100

outside HQ

1 2.3-1.1% of

annual

wages. +

$10 per

dep. up to

$30

18-29 90-120 Greater of

$10 or

1/2 basic

wba

6 34-31» 14 28 Any time 9

2.6 V i

Ariz. 1-1/2 x hqw;

$725 in HQ

1 1/25 29 95 $15 1/3 12+ 26 20 weeks 0.15 3.50

Ark. 30; wages in

2 quarters

1 1/26 up to

66-2/3% of

State aww

15 136 2/5 1/3 10 26 10 days 0.5 4.4

Calif. $900 1 1/25-1/34 30 120 Lesser of

S25 and

25% of

wages

1/2 ?12+-1! 726 Over $100

in any

quarter

9 1.3 4.8

Colo. 30 1 60% of 1/13

of claimant's

hqw up to

50% of State

aww

25 150 1/4 wba 1/3 7+-10 26 13 weeks

or $500

in CQ

0.2 4.0

Conn. 40 0 1/26, up to

60% of

State aww

♦ $5 per

dep. up to

1/2 wba

15-22 134-184 1/3 wages Uniform ?26 726 20 weeks 1.5 6.0

Del. 36 0 1/26, up to

66-2/3% o f .

State aww— /

20 150 Greater of

$10 or 30%

of wba

1/2 11-18 1/ 26 20 weeks 1.6 4.5

D.C. 1-1/2 x hqw;

not less

than $450;

$300 in 1

quarter

1/23 up to

66-2/3% of

State aww

♦ $1 per

dep. up to

$3*

13-14 4181 1/5 wages 1/2 17+ 34 Any time 1.0 5.4

Fla. 20 weeks

employment

at average

of $20 or

more

1 1/2 claim

ant's aww

10 95 55 1/2 weeks

employment

10 26 20 weeks 0.4 4.5

Ga. 1-1/2 x hqw 21 I/25+$1.00 27 90 58 1/4 4 26 20 weeks 0.07 5.71

Hawaii 30; 14 weeks

employment

101 1/25 up to

66-2/3% of

State aww

5 144 $2 Uniform ?26 ?26 Any time 91.8 94.5

-'Vv..

234

i , BEN.:fit s I COVERAGE

Duration in

Qualifying

wage or

employment

(number x

wba or as

indicated)^

52-week period

state

Waitir

week2

Computation

g of wba

(fraction of

hqw or as

indicated/'*

Wba

tota

plo

for

L unen-

^ment4

Earnings

disre

garded ̂

Proportion

of base-

period

wages ̂

Benefit

weeks for

total un

employment^

1 Sire of

• firm (1

worker in

specified

time and/

1979 Tax

rates (per

cent of

wages) 9

Min. Max. Min? Max. | payroll6 Min. Max.

Idaho 1-1/4 x hqw;

not less

them

$910.01 in

1 quarter;

wages in 2

quarters

1 1/26 up to

60% of

State aww.

S36 $132 1/2 wba Weighted

schedule

of bpw in

relation

to hqw

10 26 20 weeks or

$300 in

any quarte

90. 9

r

94.0

111. $1,400; $385

outside HQ

10 1 claimant

aww up to

50% of 13

State aww

15 135-18 0 57 Uniform 26 26 20 weeks 9 0.1 94.0

Ind. 1-1/4 x hqwj

not less

1 4.3% of high 40 84-141 20% of wba 1/4 3+ 26 20 weeks 0.3quarter Z/

than $1,500; wage credit than BP

2 quarters employer

i

Iowa 3 - l./4xhqw

$200 in qtr

0 i/ W 17-18 134-162 1/4 wba 1/3 15 26 20 weeks 90.6 Y o

other than

*

HQ

Fans. 30; wages in

2 quarters

1 4.25% of HQW

up to 60% of

34 136 $8 1/3 10 26 20 weeks 0 3.5

State aww

Ky. 1-3/8 x how; 8

x wba in ‘last

2 cuarters;

0 1/23 up to

55% of

22 120 1/5 wages 1/3 15 26 20 weeks 0.5 5.0

CSG0 in 1 quarter and

$500 in other

State aww

quarters

14/

1/20-1/25La. .30 101 10 149 1/2 wba 2/5 12 28 20 weeks 1.63 4.53Maine 2 x annual 0 1/22 up to 12-17 104-156 sio 1/3 13+-25 26 20 weeks 2.4aww in each 52% of State

of 2 qtrs. aww +$5 per

t 7 x annual dep. to 1/2

aww in HP wba

Md. 1-1/2 x hqw;

$576.01 in

0 1/24 + $3

per dep. up

25-28 *120 $10 Uniform 26 26 Any time 3.1 5.0

1 quarter;

wages in 2

quarters

to $12

Mass. 30; not less

than $1,200

1 1/21-1/26

up to 57.5%

12-16 131-197 40% not

less than

36% 9+-30 30 13 weeks 2.6 6.4

of State $10 noraww, + $6 more than

per dep. up

to 1/2 wba3

$30

Mich. 14 weeks

employment

at $25.01

0 60% of

claimant's

aww up to

416-18 97-136 Up to 1/2

wba^

3/4 weeks

employment

11 26 20 weeks or

$1,000 in

CY

1.0 8.0

or more $97 with

variable

max. for

claimants

with dep.3

Minn. L5 weeks

employment

at $50 or

101 ±3/ 30 162 $25 /10 weeks

employment

13 26 20 weeks 91.0 7.5

more

Miss. 6; $160 in

1 quarter;

1 1/26 10 90 55 1/3 12 26 20 weeks 2.6 2.7

wages in 2

quarters

1

235

BENEflTS COVERAGE TAXES

Duration in

52-week period

Qualifying

wage or Computation Proportion Benefit firm (1 1979 Tax

employment Waiting of wba Wba for Earnings of base- weeks for worker in rates (per-

State (number x week5 (fraction of total unco- dlfcre- period

wages®

total un- specified cent of

hqw or as ployroent' garded5 employment time and/ wages)

indicated^ *indicated)

Min. Max. Min? Max. payrol^6 Min. Max.

Mo. 30 x wba; |30C 101 4.5% $15 105 $10 1/3 10-13+ 26 20 weeks 0.5 3.2

in 1 quarteri

wages in 2

quarters

Mont. 20 weeks 1 1/2 wks. of

claimant's

employment

30 131 1/2 wages Weighted 8 26 Over $500 in >1.9 94.4

employment

at $50 or

more

in excess

of 1/4

wbs

schedule

of bpw in

relation

to hqw

preceding

year

Neb. $600; $200 1 1/19-1/23 12 106 Up to 1/2 1/3 17 26 20 weeks 0.1 2.7

in each of

2 quarters

wba

Nev. 1-1/2 x hqw 0 1/25, up to 16 123 1/4 wages 1/3 11 26 $225 in any 9i.i 93.5

50% of

State aww

quarter

N.H. 51,200; $600 0 1.8-1.2% of 21 114 1/5 wba Uniform 26 26 20 weeks .05 6.5

in each of annual

2 quarters wages

N-J. 20 weeks 101 66-2/3% of 20 123 Greater of 3/4 weeks 15 26 $1,000 in 9i . 2 96.2

employment claimant's $5 or 1/5 employment any year 1

»t $30 or aww up to wba

more; or 50% of

$2,200 State aww

::.Mex. 1-1/4 x hqw 1 1/26; not 22 106 1/5 wba 3/5 18+ 26 20 weeks or 90.9 * 5

less than $450 in an}

10% nor more

than 50% of

State aww

quarter

N.Y. 20 weeks 121 67-50% of 25 125 (12) Uniform 26 26 $300 in any 1.8 5.5

employment claimant * s quarter

at average

of $40 or

aww

11

N.C. 1-1/2 x hqwj 1 1/26 up to 15 130 1/2 wba 1/3 bpw 13 26 20 weeks 0.1 5.7

not less 66-2/3% of

than

$565.50;

$150 in 1

quarter

State aww

N.Dak. 40 x min. wba, 1 1/26 up to 39 143 1/2 wba Weighted

schedule 12 26 20 weeks 90.3 94.8

wages in 67% of of bpw in

2 quarters State aww relation

to hqw

Ohio 20 weeks 1°1 l/2 claimant’s 10 128-202 1/5 wba 20 x wba +• 20 26 20 weeks .9 4.6

employment aww d . a. wba for

at $20 or of $1-74 each credit

more based on week in

claimant's excess of

aww and

number of

20

dep. 1/17/

Okla. 1-1/2 x hqw; 1 1/25 up to 16 156 $7 1/3 20+ 26 20 weeks 0.6 4.7

not less 66-2/3% of

than $1,000

in BP;

$6,000

State aww

Oreg. 18 weeks 1 1.25% of bpw 38 138 1/3 wba 1/3 6 26 18 weeks or 92.6 94.0

employment up to 55% $225 in

at average

of $20 or

more; not

less than

$700

of State aww any quarter

236

1

P . R.

BENEFITS

Qualifying

wage or

*»rnp logmen t

(number x

wba or at

indicated)1

32 + -36;

$120 in HQ

and $440 in

BP; at

loast 20%

of bpw

outside HQ

21 + -30;

not lass

than $280;

$75 in 1

quarter;

wages in

2 quarters

20 weeks

employment

at $58 or

more; or

$3,480

1-1/2 x hqw;

now less

than $300;

$180 in 1

quarter

$600 in HQ;

20 x wba

outside HQ

36; $494.01

.in 1 quarter

1-1/2 x hqw;

not less

than $500 or

2/3 FICA

tax base

19 weeks

employment

at $20 or

more; not

less than

$700

26+-30; not

less than

S99 in 1

quarter and

wages in 2

quarters

20 weeks

employment

at $35 or

more

36; wages in

2 quarters

Waiting

week^

Computation

of wba

(fraction of

hqw or as

indicated) 1 , 2

10,

Wash. 680 hours

1/20-1/25 up

to 66-2/3%

of State

aww + $5

for 1 dep;

$3 for 2d

1/11-1/26;

up to 50%

of State

aww

55% of claim

ant's aww

up to 60% of

State aww, +

$5 per dep.

up to $20

1/26 up to

66-2/3% of

State aww

1/22 up to

62% of

State aww

1/26-1/31

17

Wba for

total unem

ployment4*

Earnings

disre

garded5

Min.

1/25

1/26 up to

65% of

State aww

1/23-1/25

1/2 claim

ant's aww

for highest

20 weeks up

to 60% of

State aww

1/25

1/25 of aver

age of 2

highest

quarter wages

up to 55% of

State aww

32-37

28

Max.

S162-170 Greater of

$6 or 40%

wba

130-150

114

119

n o

$5

1/4 woa

1/2 wages

up to 1/2

wba

$20

Greater of

$5 or 1/4

wba

Duration in

52-week period

Proportion

of base-

periog

wages

Benefit

weeks for

total un

employment

8

Uniform

Uniform

150 I .

90

3/10 wba

than

regular

employer

1/4 wages

in excess

of $5

3/5 weeks

employment

1/3

30

1/3

1/3

12

10

Size of

firm (1

worker in

specified

time and/

or 3ize of

payroll)16

1979 Tax

rates (per

cent ofg

wages)*

Any time

20 Any time

26

13+ 26

38 122

150

$15 + $3

for each

dep. up

to $5

Greater of

1/3 wba or

$10

$5 + 1/4

wages

Weighted

schedule

of bpw in

relation tc

hqw

1 0 -2 2

26

1/3

1/3 8+-25+

Any time

20 weeks

20 weeks

20 weeks

20 weeks

$140 in CQ

in current

or preced

ing CY

Any time

1.0

92.95 $2.

4.0

9 192.2 4.0

1.3 4.10

20 weeks

Any time

1.3

1-7 6.0

2 . 8

3.3

237

I

4

BENEFITS COVERAGE TAXES

Qualifying

waga or

employment

(number x

wba or aa .

indicated)

Duration in

52-week period

State

Waiting

veek^

Computation

of wba

(fraction of

hqw or at

indicated) '

Wba for

total unem

ployment*

Earnings

disre-5

garded

Proportion

of base-

period

wages^

Benefit

weeks for

total un- 7

employment

firm (1

worker in

specified

time and/

or size of

payroll)

1979 Tax

rate* (per

cent of^

wages)

Min. Max. Min.8 Max. Min. Max.

Vf .Va. $1,150

and wages

in 2

quarters

2i 1.5-1.0% of

annual wages

up to

70% of

State aww

18 184 $25 Uniform 28 28 20 weeks 0 3.3

Wise. 15 weaks

employment;

average of

$56.01 or

more with 1

employer

0 50% of claim

ant 's aww up

to 66-2/3%

of State aww

30 160 Up to 1/2

wba

8/10 weeks

employment

1-12+ 34 20 weeks 0.5 6.5

Wyo. 1-6/10 x hqw;

not less

than $600

in 1 quarter

1 1/25 up to

55% of Stata

aww

24 146 Greater of

$15 or

25% wba

3/10 12-26 26 $500 in

current or

preceding_ex___

0.37 3.07 1

i

eekly benefit amount abbreviated In columns and footnotes as

vba; base period* BP; base-period wages, bpw; high quarter, HQ;

hlgh-quarter wages, hqw; average weekly wage, aww; benefit year,

BY; calendar quarter, CQ; calendar year, CY; dependent, dep.;

dependents allowances, da.; minimum, min.; maximum, max.

^Unless otherwise noted, waiting period same for total or

partial unemployment. W.Va., no waiting period

required for partial unemployment. Waiting period may be

suspended if Governor declares State of emergency following

disaster, N.Y., R. I, In Ca. no waiting week if claimant

unemployed not through own fault.

^When States use weighted high-quarter, annual-wage, or average

weekly-wage formula, approximate fractions or percentages figured

at midpoint of lowest and highest normal wage brackets. When

da provided, fraction applies to basic wba. In States noted

variable amounts above max. basic benefits limited to claimants

with specified number of dep. and earnings in excess of amounts

applicable to max. basic wba. In Ind. da. paid only to

claimants with earnings in excess of that needed to qualify for

basic wba and who have 1-4 deps. In Iowa, Mich, and Ohio

claimants ray be eligible for augmented amount at all benefit

levels but benefit amounts above basic max. available only to

claimants in dependency classes' whose hqw or aww are higher than

that required for max. basic benefit. In Mass. for claimant with

aww in excess of $66 wba computed at 1/52 of l highest quarters

of earnings or 1/26 of highest quarter if claimant had no more

than 2 quarters work.

*When 2 amounts given, higher includes da. Higher for min. wba

includes max. allowance for one dep.; Mich, for 1 dep. child or

2 dep. other than a child. In D.C. and Md., same max. with or

without dep.

"*In computing wba for partial unemployment, in States noted full

wba paid if earnings are less than 1/2 wba; 1/2 wba if earnings

ars 1/2 wba but less than wba.

a

For claimants with min. qualifying wages and min. wba. When

two amounts shown, range of duration applies to claimants

with min. qualifying wages in BP; longer duration applies with

min. wba; shorter duration applies with max. possible concen

tration of wages in HQ,; therefore highest wba possible for

such BP earnings. Minimum in Del, applies to seasonal employ

ment. Vis. determines entitlement separately for each employer. |

Lower end of range applies to claimants with only 1 week of work

at qualifying wage; upper end to claimants with 15 weeks or more

of such wages,

q̂Represents min.-max. rates assigned employers in CY 1979. Ala.,

Alaska, N.J. require employee taxes. Contributions for 1980

required on wages up to $6,000 in all States except 111., $6,500;

Ala. , $6,600; JTJ. , $6,900; N.Mex. , and R.I., $7,200TTova, $7,400;

Mont., and N.Dak., $7,600; Nev., $7,900; Minn.. $8,000; Wash.,

59,600; Alaska and Oreg., $lO,000; Idaho, $10,800; Utah, $11,000:

Hawaii, $11,200; P.RT all wages.

^^Waiting period compensable if claimant entitled to 12 con

secutive weeks of benefits immediately following, Hawaii;

unemployed at least 6 weeks and not disqualified. La.; after

9 consecutive weeks benefits paid. Mo.; when benefits are

payable for third week following waiting period, N. J .;

after benefits paid 4 weeks, Tex., Va.; after any 4 weeks

in BY, Minn.; after 3d week unemployment. 111.; after

3d week of total unemployment, Ohio.

**0r 15 weeks in last year and 40 weeks in last 2 years of aww

of $40 or more, N.Y. »

12For N.Y., waiting period is 4 effective days accumulated in

1-4 weeks; partial benefits 1/4 wba for each 1 to 3 effective

days. Effective days: fourth and each subsequent day of total

unemployment in week for which not more than $125 is paid.

*^To 602 State aww if claimant has nonworking spouse;

66-2/32 if he had dep. child-, 111.; 1/19-1/23 up to 582 of State

aww for claimants with no dep. variable max., up to 702 of State

aww for claimants with dep., Iowa.; 602 of first $85,402 of next

$85, 502 of balance. Max. set at 66-2/32, Minn.

^States noted have weighted schedule with percent of benefits 14Up to 66-2/3% of State aww. La. 63% until 1981, Del.

based on bottom of lowest and highest wage brackets.

^Benefits extended under State program when unemployment in State

reaches specified levels: Calif., Hawaii, by 502; Conn, by 13

weeks. In P.R. benefits extended by 32 weeks in certain indus

tries, occupations or establishments when special unemployment

situation exists. Benefits also may be extended during periods

of high unemployment by 502, up to 13 weeks, under Federal-State

Extended Compensation Program.

^ $1,500 in any CQ in current or preceding CY unless otherwise

specified.

^Max. amount adjusted annually: by same percentage increase

as occurs in State aww (Ohio) by $7 for each $10 increase in

average weekly wage of manufacturing production workers (Texas).

O U 1 •••

238

y*.:

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on the 6th day of May 1983 I served

a copy of the Motion of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc. to File a Brief As Amicus Curiae and the Brief of

the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., As Amicus

Curiae on all parties by depositing copies of the Brief and

Motion in the United States mail, postage prepaid, upon the

following counsel:

Bryant A. Whitmire, Esquire

WHITMIRE, COLEMAN & WHITMIRE

903 City Federal Building

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Robert L. Wiggins, Jr., Esquire Suite 716

Brown-Marx Building

2000 1st Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Philip Sklover, Esquire

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION Room 2293

2401 E Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20506