Baston v. Kentucky Slip Opinion

Public Court Documents

April 30, 1986

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Baston v. Kentucky Slip Opinion, 1986. 301ed2f3-c29a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0c592340-f3e4-4a09-ab75-2a4d4ecc81fa/baston-v-kentucky-slip-opinion. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

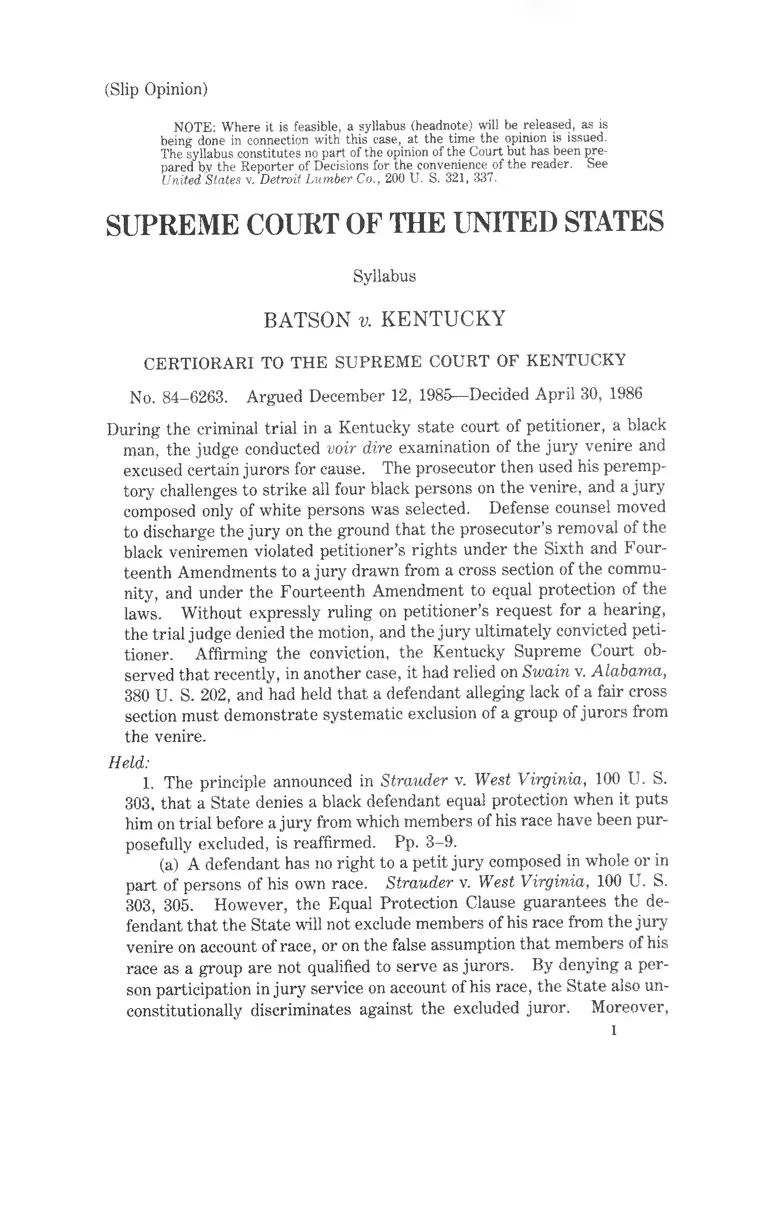

(Slip Opinion)

NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is

being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued.

The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been pre

pared bv the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See

United States v. Detroit Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Syllabus

BATSON v. KENTUCKY

CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF KENTUCKY

No. 84-6263. Argued December 12, 1985—Decided April 30, 1986

During the criminal trial in a Kentucky state court of petitioner, a black

rpan, the judge conducted voir dire examination of the jury venire and

excused certain jurors for cause. The prosecutor then used his peremp

tory challenges to strike all four black persons on the venire, and a jury

composed only of white persons was selected. Defense counsel moved

to discharge the jury on the ground that the prosecutor’s removal of the

black veniremen violated petitioner’s rights under the Sixth and Four

teenth Amendments to a jury drawn from a cross section of the commu

nity, and under the Fourteenth Amendment to equal protection of the

laws. Without expressly ruling on petitioner’s request for a hearing,

the trial judge denied the motion, and the jury ultimately convicted peti

tioner. Affirming the conviction, the Kentucky Supreme Court ob

served that recently, in another case, it had relied on Swain v. Alabama,

380 U. S. 202, and had held that a defendant alleging lack of a fair cross

section must demonstrate systematic exclusion of a group of jurors from

the venire.

Held:

1. The principle announced in Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S.

303, that a State denies a black defendant equal protection when it puts

him on trial before a jury from which members of his race have been pur

posefully excluded, is reaffirmed. Pp. 3-9.

(a) A defendant has no right to a petit jury composed in whole or in

part of persons of his own race. Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S.

303, 305. However, the Equal Protection Clause guarantees the de

fendant that the State will not exclude members of his race from the jury

venire on account of race, or on the false assumption that members of his

race as a group are not qualified to serve as jurors. By denying a per

son participation in jury service on account of his race, the State also un

constitutionally discriminates against the excluded juror. Moreover,

1

II BATSON v. KENTUCKY

Syllabus

selection procedures that purposefully exclude black persons from juries

undermine public confidence in the fairness of our system of justice.

Pp. 4-7.

(b) The same equal protection principles as are applied to determine

whether there is discrimination in selecting the venire also govern the

State’s use of peremptory challenges to strike individual jurors from the

petit jury. Although a prosecutor ordinarily is entitled to exercise pe

remptory challenges for any reason, as long as that reason is related to

his view concerning the outcome of the case to be tried, the Equal Pro

tection Clause forbids the prosecutor to challenge potential jurors solely

on account of their race or on the assumption that black jurors as a group

will be unable impartially to consider the State’s case against a black de

fendant. Pp. 7-9.

2. The portion of Swain v. Alabama, supra, concerning the eviden

tiary burden placed on a defendant who claims that he has been denied

equal protection through the State’s discriminatory use of peremptory

challenges is rejected. In Swain, it was held that a black defendant

could make out a prima facie case of purposeful discrimination on proof

that the peremptory challenge system as a whole was being perverted.

Evidence offered by the defendant in Swain did not meet that standard

because it did not demonstrate the circumstances under which prosecu

tors in the jurisdiction were responsible for striking black jurors beyond

the facts of the defendant’s case. This evidentiary formulation is incon

sistent with equal protection standards subsequently developed in deci

sions relating to selection of the jury venire. A defendant may make a

prima facie showing of purposeful racial discrimination in selection of the

venire by relying solely on the facts concerning its selection in his case.

Pp. 9-15.

3. A defendant may establish a prima facie case of purposeful dis

crimination solely on evidence concerning the prosecutor’s exercise of pe

remptory challenges at the defendant’s trial. The defendant first must

show that he is a member of a cognizable racial group, and that the pros

ecutor has exercised peremptory challenges to remove from the venire

members of the defendant’s race. The defendant may also rely on the

fact that peremptory challenges constitute a jury selection practice that

permits those to discriminate who are of a mind to discriminate. Fi

nally, the defendant must show that such facts and any other relevant

circumstances raise an inference that the prosecutor used peremptory

challenges to exclude the veniremen from the petit jury on account of

their race. Once the defendant makes a prima facie showing, the bur

den shifts to the State to come forward with a neutral explanation for

challenging black jurors. The prosecutor may not rebut a prima facie

showing by stating that he challenged the jurors on the assumption that

BATSON v. KENTUCKY in

Syllabus

they would be partial to the defendant because of their shared race or by

affirming his good faith in individual selections. Pp. 15-18.

4. While the peremptory challenge occupies an important position in

trial procedures, the above-stated principles will not undermine the con

tribution that the challenge generally makes to the administration of jus

tice. Nor will application of such principles create serious adminis

trative difficulties. Pp. 18-19.

5. Because the trial court here flatly rejected petitioner’s objection to

the prosecutor’s removal of all black persons on the venire without re

quiring the prosecutor to explain his action, the case is remanded for fur

ther proceedings. Pp. 19-20.

Reversed and remanded.

Powell, J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which Brennan,

White , Marshall, Blackmun, Stevens, and O’Connor, JJ., joined.

White and Marshall, JJ., filed concurring opinions. Stevens, J., filed

a concurring opinion, in which Brennan, J., joined. O’Connor, J., filed

a concurring opinion. BURGER, C. J., filed a dissenting opinion, in which

Rehnquist, J., joined. Rehnquist, J., filed a dissenting opinion, in

which Burger, C. J ., joined.

NOTICE: This opinion is subject to formal revision before publication in the

preliminary print of the United States Reports. Readers are requested to

notify the Reporter of Decisions, Supreme Court of the United States, Wash

ington, D. C. 20543, of any typographical or other formal errors, in order

that corrections may be made before the preliminary print goes to press.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 84-6263

JAMES KIRKLAND BATSON, PETITIONER

v. KENTUCKY

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF KENTUCKY

[April 30, 1986]

J ustice Powell delivered the opinion of the Court.

This case requires us to reexamine that portion of Swain v.

Alabama, 380 U. S. 202 (1965), concerning the evidentiary

burden placed or a criminal defendant who claims that he has

been denied equal protection through the State’s use of pe

remptory challenges to exclude members of his race from the

petit jury .1

1 Following the lead of a number of state courts construing their state’s

constitution, two federal Courts of Appeals recently have accepted the

view that peremptory challenges used to strike black jurors in a particular

case may violate the Sixth Amendment. Booker v. Jabe, 775 F. 2d 762

(CA6 1985), cert, pending, No. 85-1028; McCray v. Abrams, 750 F. 2d

1113 (CA2 1984), cert, pending, No. 84-1426. See People v. Wheeler, 22

Cal. 3d 258, 583 P. 2d 748 (1978); Riley v. State, 496 A. 2d 997, 1009-1013

(Del. 1985); State v. Neil, 457 So. 2d 481 (Fla. 1984); Commonwealth v.

Soares, 377 Mass. 461, 387 N. E. 2d 499, cert, denied, 444 U. S. 881 (1979).

See also State v. Crespin, 94 N. M. 486, 612 P. 2d 716 (App. 1980). Other

Courts of Appeals have rejected that position, adhering to the requirement

that a defendant must prove systematic exclusion of blacks from the petit

jury to establish a constitutional violation. United States v. Childress,

715 F. 2d 1313 (CA8 1983) (en banc), cert, denied, 464 U. S. 1063 (1984);

United States v. Whitfield, 715 F. 2d 145, 147 (CA4 1983). See Beed v.

State, 271 Ark. 526, 530-531, 609 S. W. 2d 898, 903 (1980); Blackwell v.

State, 248 Ga. 138, 281 S. E. 2d 599, 599-600 (1981); Gilliard v. State, 428

So. 2d 576, 579 (Miss.), cert, denied, 464 U. S. 867 (1983); People v.

McCray, 57 N. Y. 2d 542, 546-549, 443 N. E. 2d 915, 916-919 (1982), cert,

denied, 461 U. S. 961 (1983); State v. Lynch, 300 N. C. 534, 546-547, 268

2 BATSON v. KENTUCKY

I

Petitioner, a black man, was indicted in Kentucky on

charges of second-degree burglary and receipt of stolen

goods. On the first day of trial in Jefferson Circuit Court,

the judge conducted voir dire examination of the venire, ex

cused certain jurors for cause, and permitted the parties to

exercise peremptory challenges.2 The prosecutor used his

peremptory challenges to strike all four black persons on the

venire, and a jury composed only of white persons was se

lected. Defense counsel moved to discharge the jury before

it was sworn on the ground that the prosecutor’s removal of

the black veniremen violated petitioner’s rights under the

Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments to a jury drawn from a

cross-section of the community, and under the Fourteenth

Amendment to equal protection of the laws. Counsel re

quested a hearing on his motion. Without expressly ruling

on the request for a hearing, the trial judge observed that the

parties were entitled to use their peremptory challenges to

“strike anybody they want to.” The judge then denied peti

tioner’s motion, reasoning that the cross-section requirement

applies only to selection of the venire and not to selection of

the petit jury itself.

S. E. 2d 161, 168-169 (1980). Federal Courts of Appeals also have dis

agreed over the circumstances under which supervisory power may be

used to scrutinize the prosecutor’s exercise of peremptory challenges to

strike blacks from the venire. Compare United States v. Leslie ,----- F.

2d —— (CA5 1986) (en banc), with United States v. Jackson, 696 F. 2d

578, 592-593 (CA8 1982), cert, denied, 460 U. S. 1073 (1983). See also

United States v. McDaniels, 379 F. Supp. 1243 (ED La. 1974).

2 The Kentucky Rules of Criminal Procedure authorize the trial court to

permit counsel to conduct voir dire examination or to conduct the examina

tion itself. Ky. Rule Crim. Proc. 9.38. After jurors have been excused

for cause, the parties exercise their peremptory challenges simultaneously

by striking names from a list of qualified jurors equal to the number to be

seated plus the number of allowable peremptory challenges. Rule 9.36.

Since the offense charged in this case was a felony, and an alternate juror

was called, the prosecutor was entitled to six peremptory challenges, and

defense counsel to nine. Rule 9.40.

BATSON v. KENTUCKY 3

The jury convicted petitioner on both counts. On appeal

to the Supreme Court of Kentucky, petitioner pressed,

among other claims, the argument concerning the prosecu

tor’s use of peremptory challenges. Conceding that Swain

v. Alabama, supra, apparently foreclosed an equal protec

tion claim based solely on the prosecutor’s conduct in this

case, petitioner urged the court to follow decisions of other

states, People v. Wheeler, 22 Cal. 3d 258, 583 P. 2d 748

(1978); Commonwealth v. Soares, 377 Mass. 461, 387 N. E.

2d 499, cert, denied, 444 U. S. 881 (1979), and to hold that

such conduct violated his rights under the Sixth Amendment

and Section 11 of the Kentucky Constitution to a jury drawn

from a cross-section of the community. Petitioner also con

tended that the facts showed that the prosecutor had en

gaged in a “pattern” of discriminatory challenges in this case

and established an equal protection violation under Swain.

The Supreme Court of Kentucky affirmed. In a single

paragraph, the court declined petitioner’s invitation to adopt

the reasoning of People v. Wheeler, supra, and Common

wealth v. Soares, supra. The court observed that it recently

had reaffirmed its reliance on Swain, and had held that a de

fendant alleging lack of a fair cross-section must demonstrate

systematic exclusion of a group of jurors from the venire.

See Commonwealth v. McFerron, 680 S. W. 2d 924 (1984).

We granted certiorari, 471 U. S. ----- (1985), and now

reverse.

II

In Swain v. Alabama, this Court recognized that a

“State’s purposeful or deliberate denial to Negroes on ac

count of race of participation as jurors in the administration

of justice violates the Equal Protection Clause.” 380 U. S.,

at 203-204. This principle has been “consistently and re

peatedly” reaffirmed, id., at 204, in numerous decisions of

this Court both preceding and following Swain.3 We re-

3 See, e. g., Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 (1880); Neal v.

4 BATSON v. KENTUCKY

affirm the principle today.4

A

More than a century ago, the Court decided that the State

denies a black defendant equal protection of the laws when it

puts him on trial before a jury from which members of his

race have been purposefully excluded. Strauder v. West

Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 (1880). That decision laid the foun

dation for the Court’s unceasing efforts to eradicate racial

discrimination in the procedures used to select the venire

from which individual jurors are drawn. In Strauder, the

Court explained that the central concern of the recently rati

fied Fourteenth Amendment was to put an end to govern-

Delaware, 103 U. S. 370 (1881); Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587 (1935);

Hollins v. Oklahoma, 295 U. S. 394 (1935) (per curiam); Pierre v. Louisi

ana, 306 U. S. 354 (1939); Patton v. Mississippi, 332 U. S. 463 (1947);

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U. S. 559 (1953); Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U. S. 475

(1954); Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U. S. 545 (1967); Jones v. Georgia, 389

U. S. 24 (1967) (per curiam); Carter v. Jury Commission of Greene

County, 396 U. S. 320 (1970); Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U. S. 482 (1977);

Rose v. Mitchell, 443 U. S. 545 (1979); Vasquez v. Hillery, 474 U. S. ——

(1986).

The basic principles prohibiting exclusion of persons from participation

in jury service on account of their race “are essentially the same for grand

juries and for petit juries.” Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U. S. 625, 626,

n. 3 (1972); see Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587, 589 (1935). These prin

ciples are reinforced by the criminal laws of the United States. 18

U. S. C. §243.

4 In this Court, petitioner has argued that the prosecutor’s conduct vio

lated his rights under the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments to an impar

tial jury and to a jury drawn from a cross-section of the community. Peti

tioner has framed his argument in these terms in an apparent effort to

avoid inviting the Court directly to reconsider one of its own precedents.

On the other hand, the State has insisted that petitioner is claiming a de

nial of equal protection and that we must reconsider Swain to find a con

stitutional violation on this record. We agree with the State that resolu

tion of petitioner’s claim properly turns on application of equal protection

principles and express no view on the merits of any of petitioner’s Sixth

Amendment arguments.

BATSON v. KENTUCKY 5

mental discrimination on account of race. Id,., at 306-307.

Exclusion of black citizens from service as jurors constitutes

a primary example of the evil the Fourteenth Amendment

was designed to cure.

In holding that racial discrimination in jury selection of

fends the Equal Protection Clause, the Court in Strauder

recognized, however, that a defendant has no right to a “petit

jury composed in whole or in part of persons of his own race.”

Id., at 305.5 “The number of our races and nationalities

stands in the way of evolution of such a conception” of the de

mand of equal protection. Akins v. Texas, 325 U. S. 398,

403 (1945).6 But the defendant does have the right to be

tried by a jury whose members are selected pursuant to non-

discriminatory criteria. Martin v. Texas, 200 U. S. 316, 321

(1906); Ex parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339, 345 (1880). The

Equal Protection Clause guarantees the defendant that the

State will not exclude members of his race from the jury ve

nire on account of race, Strauder, supra, at 305,7 or on the

false assumption that members of his race as a group are not

qualified to serve as jurors, see Norris v. Alabama, 294

U. S. 587, 599 (1935); Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370, 397

(1881).

5 See Hernandez v. Texas, supra, at 482; Cassell v. Texas, 339 U. S.

282, 286-287 (1950) (plurality opinion); Akins v. Texas, 325 U. S. 398, 403

(1945); Martin v. Texas, 200 U. S. 316, 321 (1906); Neal v. Delaware,

supra, at 394.

6 Similarly, though the Sixth Amendment guarantees that the petit jury

will be selected from a pool of names representing a cross-section of the

community, Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U. S. 522 (1975), we have never held

that the Sixth Amendment requires that “petit juries actually chosen must

mirror the community and reflect the various distinctive groups in the

population,” id., at 538. Indeed, it would be impossible to apply a concept

of proportional representation to the petit jury in view of the heteroge

neous nature of our society. Such impossibility is illustrated by the

Court’s holding that a jury of six persons is not unconstitutional. Wil

liams v. Florida, 399 U. S. 78, 102-103 (1970).

7 See Hernandez v. Texas, supra, at 482; Cassell v. Texas, supra, at

287; Akins v. Texas, supra, at 403; Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S., at 394.

6 BATSON v. KENTUCKY

Purposeful racial discrimination in selection of the venire

violates a defendant’s right to equal protection because it de

nies him the protection that a trial by jury is intended to se

cure. “The very idea of a jury is a body . . . composed of the

peers or equals of the person whose rights it is selected or

summoned to determine; that is, of his neighbors, fellows, as

sociates, persons having the same legal status in society as

that which he holds.” Strauder, supra, at 308; see Carter v.

Jury Commission of Greene County, 396 U. S. 320, 330

(1970). The petit jury has occupied a central position in our

system of justice by safeguarding a person accused of crime

against the arbitrary exercise of power by prosecutor or

judge. Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U. S. 145, 156 (1968).8

Those on the venire must be “indifferently chosen,”9 to se

cure the defendant’s right under the Fourteenth Amendment

to “protection of life and liberty against race or color preju

dice.” Strauder, supra, at 309.

Racial discrimination in selection of jurors harms not only

the accused whose life or liberty they are summoned to try.

8 See Taylor v. Louisiana, supra, at 530; Williams v. Florida, supra,

at 100. See also Powell, Jury Trial of Crimes, 23 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 1

(1966).

In Duncan v. Louisiana, decided after Swain, the Court concluded that

the right to trial by jury in criminal cases was such a fundamental feature

of the American system of justice that it was protected against state action

by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. 391 U. S., at

147-158. The Court emphasized that a defendant’s right to be tried by a

jury of his peers is designed “to prevent oppression by the Government.”

Id., at 155, 156-157. For a jury to perform its intended function as a

check on official power, it must be a body drawn from the community.

Duncan v. Louisiana, supra, at 156; Glasser v. United States, 315 U. S.

60, 86-88 (1942). By compromising the representative quality of the jury,

discriminatory selection procedures make “juries ready weapons for offi

cials to oppress those accused individuals who by chance are numbered

among unpopular or inarticulate minorities.” Akins v. Texas, 325 U. S.,

at 408 (Murphy, J ., dissenting).

9 4 W. Blackstone, Commentaries 349 (Cooley ed. 1899) (quoted in Dun

can v. Lousiana, supra, at 152).

BATSON v. KENTUCKY 7

Competence to serve as a juror ultimately depends on an as

sessment of individual qualifications and ability impartially to

consider evidence presented at a trial. See Thiel v. South

ern Pacific Co., 328 U. S. 217, 223-224 (1946). A person’s

race simply “is unrelated to his fitness as a juror.” Id,., at

227 (Frankfurter, J ., dissenting). As long ago as Strauder,

therefore, the Court recognized that by denying a person

participation in jury service on account of his race, the State

unconstitutionally discriminated against the excluded juror.

100 U. S., at 308; see Carter v. Jury Commission of Greene

County, supra, at 329-330; Neal v. Delaware, supra, at 386.

The harm from discriminatory jury selection extends be

yond that inflicted on the defendant and the excluded juror to

touch the entire community. Selection procedures that pur

posefully exclude black persons from juries undermine public

confidence in the fairness of our system of justice. See

Ballard v. United States, 329 U. S. 187, 195 (1946); McCray

v. New York, 461 U. S. 961, 968 (1983) (Marshall, J., dis

senting from denial of certiorari). Discrimination within the

judicial system is most pernicious because it is “a stimulant to

that race prejudice which is an impediment to securing to

[black citizens] that equal justice which the law aims to se

cure to all others.” Strauder, supra, at 308.

B

In Strauder, the Court invalidated a state statute that pro

vided that only white men could serve as jurors. 100 U. S.,

at 305. We can be confident that no state now has such a

law. The Constitution requires, however, that we look be

yond the face of the statute defining juror qualifications and

also consider challenged selection practices to afford “protec

tion against action of the State through its administrative of

ficers in effecting the prohibited discrimination.” Norris v.

Alabama, 294 U. S., at 589; see Hernandez v. Texas, 347

U. S. 475, 478-479 (1954); Ex parte Virginia, 100 U. S., at

346-347. Thus, the Court has found a denial of equal protec-

8 BATSON v. KENTUCKY

tion where the procedures implementing a neutral statute op

erated to exclude persons from the venire on racial grounds,10

and has made clear that the Constitution prohibits all forms

of purposeful racial discrimination in selection of jurors.11

While decisions of this Court have been concerned largely

with discrimination during selection of the venire, the prin

ciples announced there also forbid discrimination on account

of race in selection of the petit jury. Since the Fourteenth

Amendment protects an accused throughout the proceedings

bringing him to justice, Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400, 406

(1942), the State may not draw up its jury lists pursuant to

neutral procedures but then resort to discrimination at “other

stages in the selection process,” Avery v. Georgia, 345 U. S.

559, 562 (1953); see McCray v. New York, supra, at 965, 968

(Marshall, J., dissenting from denial of certiorari); see also

Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U. S. 625, 632 (1972).

Accordingly, the component of the jury selection process at

issue here, the State’s privilege to strike individual jurors

through peremptory challenges, is subject to the commands

of the Equal Protection Clause.12 Although a prosecutor or-

nE. g., Sims v. Georgia, 389 U. S. 404, 407 (1967) (per curiam); Whitus

v. Georgia, 385 U. S., at 548-549; Avery v. Georgia, 345 U. S., at 561.

11 See Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S., at 589; Martin v. Texas, 200 U. S.,

at 319; Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S., at 394, 397.

12 We express no views on whether the Constitution imposes any limit on

the exercise of peremptory challenges by defense counsel.

Nor do we express any views on the techniques used by lawyers who

seek to obtain information about the community in which a case is to be

tried, and about members of the venire from which the jury is likely to be

drawn. See generally J. Van Dyke, Jury Selection Procedures: Our Un

certain Commitment to Representative Panels, 183-189 (1977). Prior to

voir dire examination, which serves as the basis for exercise of challenges,

lawyers wish to know as much as possible about prospective jurors, includ

ing their age, education, employment, and economic status, so that they

can ensure selection of jurors who at least have an open mind about the

case. In some jurisdictions, where a pool of jurors serves for a substantial

period of time, see J. Van Dyke, supra, at 116-118, counsel also may seek

to learn which members of the pool served on juries in other cases and the

BATSON v. KENTUCKY 9

dinarily is entitled to exercise permitted peremptory chal

lenges “for any reason at all, as long as that reason is related,

to his view concerning the outcome” of the case to be tried,

United States v. Robinson, 421 F. Supp. 467, 473 (Conn.

1976), mandamus granted sub nom. United States v. New

man, 549 F. 2d 240 (CA2 1977), the Equal Protection Clause

forbids the prosecutor to challenge potential jurors solely on

account of their race or on the assumption that black jurors as

a group will be unable impartially to consider the State’s case

against a black defendant.

III

The principles announced in Strauder never have been

questioned in any subsequent decision of this Court.

Rather, the Court has been called upon repeatedly to review

the application of those principles to particular facts.18 A re

curring question in these cases, as in any case alleging a

violation of the Equal Protection Clause, was whether the

defendant had met his burden of proving purposeful dis

crimination on the part of the State. Whitus v. Georgia, 385

U. S., at 550; Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U. S., at 478-481;

Akins v. Texas, 325 U. S., at 403-404; Martin v. Texas, 200

U. S. 316 (1906). That question also was at the heart of the

portion of Swain v. Alabama we reexamine today.14

outcome of those cases. Counsel even may employ professional investiga

tors to interview persons who have served on a particular petit jury. We

have had no occasion to consider particularly this practice. Of course,

counsel’s effort to obtain possibly relevant information about prospective

jurors is to be distinguished from the practice at issue here.

13 See, e. g., Vasquez v. Hillery, 474 U. S .----(1986); Rose v. Mitchell,

443 U. S. 545 (1979); Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U. S. 482 (1977); Alexan

der v. Louisiana, 405 U. S. 625, 628-629 (1972); Whitus v. Georgia, 385

U. S. 545, 549-550 (1967); Swain v. Alabama, supra, at 205; Coleman v.

Alabama, 377 U. S. 129 (1964); Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587, 589

(1935); Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S., at 394.

“ The decision in Swain has been the subject of extensive commentary.

Some authors have argued that the Court should reconsider the decision.

E. g., J. Van Dyke, Jury Selection Procedures: Our Uncertain Commit-

10 BATSON v. KENTUCKY

A

Swain required the Court to decide, among other issues,

whether a black defendant was denied equal protection by

the State’s exercise of peremptory challenges to exclude

members of his race from the petit jury. 380 U. S., at

209-210. The record in Swain showed that the prosecutor

had used the State’s peremptory challenges to strike the six

black persons included on the petit jury venire. Id., at 210.

While rejecting the defendant’s claim for failure to prove pur

poseful discrimination, the Court nonetheless indicated that

the Equal Protection Clause placed some limits on the State’s

exercise of peremptory challenges. Id., at 222-224.

The Court sought to accommodate the prosecutor’s histori

cal privilege of peremptory challenge free of judicial control,

id., at 214-220, and the constitutional prohibition on exclu

sion of persons from jury service on account of race, id., at

222-224. While the Constitution does not confer a right to

peremptory challenges, id., at 219 (citing Stilson v. United

States, 250 U. S. 583, 586 (1919)), those challenges tradition

ally have been viewed as one means of assuring the selection

of a qualified and unbiased jury, 380 U. S., at 219.15 To pre-

ment to Representative Panels 166-167 (1977); Imlay, Federal Jury Re,

ormation: Saving a Democratic Institution, 6 Loyola (LA) L. Rev. 247,

268-270 (1973); Kuhn, Jury Discrimination: The Next Phase, 41 S. Cal. L.

Rev. 235, 283-303 (1968); Note, Rethinking Limitations on the Peremptory

Challenge, 85 Colum. L. Rev. 1357 (1985); Note, Peremptory Challenge—

Systematic Exclusion of Prospective Jurors on the Basis of Race, 39 Miss.

L. J. 157 (1967); Comment, Swain v. Alabama: A Constitutional Blueprint

for the Perpetuation of the All-White Jury, 52 Va. L. Rev. 1157 (1966).

See also Johnson, Black Innocence and the White Jury, 83 Mich. L. Rev.

1611 (1985).

On the other hand, some commentators have argued that we should ad

here to Swain. See Saltzburg & Powers, Peremptory Challenges and the

Clash Between Impartiality and Group Representation, 41 Md. L. Rev.

337 (1982).

15 In Swain, the Court reviewed the “very old credentials” of the pe

remptory challenge system and noted the “long and widely held belief that

BATSON v. KENTUCKY 11

serve the peremptory nature of the prosecutor’s challenge,

the Court in Swain declined to scrutinize his actions in a par

ticular case by relying on a presumption that he properly ex

ercised the State’s challenges. Id., at 221-222.

The Court went on to observe, however, that a state may

not exercise its challenges in contravention of the Equal Pro

tection Clause. It was impermissible for a prosecutor to use

his challenges to exclude blacks from the jury “for reasons

wholly unrelated to the outcome of the particular case on

trial” or to deny to blacks “the same right and opportunity to

participate in the administration of justice enjoyed by the

white population.” Id., at 224. Accordingly, a black de

fendant could make out a prima facie case of purposeful dis

crimination on proof that the peremptory challenge system

was “being perverted” in that manner. Ibid. For example,

an inference of purposeful discrimination would be raised on

evidence that a prosecutor, “in case after case, whatever the

circumstances, whatever the crime and whoever the defend

ant or the victim may be, is responsible for the removal of

Negroes who have been selected as qualified jurors by the

jury commissioners and who have survived challenges for

cause, with the result that no Negroes ever serve on petit ju

ries.” Id., at 223. Evidence offered by the defendant in

Swain did not meet that standard. While the defendant

showed that prosecutors in the jurisdiction had exercised

their strikes to exclude blacks from the jury, he offered no

proof of the circumstances under which prosecutors were re

sponsible for striking black jurors beyond the facts of his own

case. Id., at 224-228.

A number of lower courts following the teaching of Swain

reasoned that proof of repeated striking of blacks over a num

ber of cases was necessary to establish a violation of the

peremptory challenge is a necessary part of trial by jury.” 380 U. S., at

219; see id., at 212-219.

12 BATSON v. KENTUCKY

Equal Protection Clause.16 Since this interpretation of Swain

has placed on defendants a crippling burden of proof,17 pros

ecutors’ peremptory challenges are now largely immune from

constitutional scrutiny. For reasons that follow, we reject

this evidentiary formulation as inconsistent with standards

that have been developed since Swain for assessing a prima

facie case under the Equal Protection Clause.

B

Since the decision in Swain, we have explained that our

cases concerning selection of the venire reflect the general

equal protection principle that the “invidious quality” of gov

ernmental action claimed to be racially discriminatory “must

ultimately be traced to a racially discriminatory purpose.”

Washington v. Davis, 426 U. S. 229, 240 (1976). As in any

equal protection case, the “burden is, of course,” on the de

fendant who alleges discriminatory selection of the venire “to

prove the existence of purposeful discrimination.” Whitus

v. Georgia, 385 U. S., at 550 (citing Tarrance v. Florida, 188

16E. g., United States v. Jenkins, 701 F. 2d 850, 859-860 (CA10 1983);

United States v. Boykin, 679 F. 2d 1240, 1245 (CA8 1982); United States v.

Pearson, 448 F. 2d 1207, 1213-1218 (CA5 1971); Thigpen v. State, 49 Ala.

App. 233, 270 So. 2d 666, 673 (1972); Jackson v. State, 245 Ark. 331, 432

S. W. 2d 876, 878 (1968); Johnson v. Maryland, 9 Md. App. 143, 262 A. 2d

792, 796-797 (1970); State v. Johnson, 125 N. J. Super. 438, 311 A. 2d 389

(1973) (per curiam); State v. Shaw, 284 N. C. 366, 200 S. E. 2d 585 (1973).

17 See McCray v. Abrams, 750 F. 2d 1113, 1120, and n. 2 (CA2 1984),

cert, pending, No. 84-1426. The lower courts have noted the practical dif

ficulties of proving that the State systematically has exercised peremptory

challenges to exclude blacks from the jury on account of race. As the

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit observed, the defendant would have

to investigate, over a number of cases, the race of persons tried in the par

ticular jurisdiction, the racial composition of the venire and petit jury, and

the manner in which both parties exercised their peremptory challenges.

United States v. Pearson, 448 F. 2d 1207, 1217 (CA5 1971). The court be

lieved this burden to be “most difficult” to meet. Ibid. In jurisdictions

where court records do not reflect the jurors’ race and where voir dire pro

ceedings are not transcribed, the burden would be insurmountable. See

People v. Wheeler, 22 Cal. 3d 258, 583 P. 2d 748, 767-768 (1978).

BATSON v. KENTUCKY 13

U. S. 519 (1903)). In deciding if the defendant has carried

his burden of persuasion, a court must undertake “a sensitive

inquiry into such circumstantial and direct evidence of intent

as may be available.” Village of Arlington Heights v. Met

ropolitan Housing Development Corp., 429 U. S. 252, 266

(1977). Circumstantial evidence of invidious intent may in

clude proof of disproportionate impact. Washington v.

Davis, 426 U. S., at 242. We have observed that under

some circumstances proof of discriminatory impact “may for

all practical purposes demonstrate unconstitutionality be

cause in various circumstances the discrimination is very dif

ficult to explain on nonracial grounds.” Ibid. For example,

“total or seriously disproportionate exclusion of Negroes

from jury venires,” ibid., “is itself such an ‘unequal applica

tion of the law . . . as to show intentional discrimination,’”

id., at 241 (quoting Akins v. Texas, 325 U. S., at 404).

Moreover, since Swain, we have recognized that a black

defendant alleging that members of his race have been imper

missibly excluded from the venire may make out a prima

facie case of purposeful discrimination by showing that the

totality of the relevant facts gives rise to an inference of dis

criminatory purpose. Washington v. Davis, supra, at

239-242. Once the defendant makes the requisite showing,

the burden shifts to the State to explain adequately the racial

exclusion. Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U. S., at 632. The

State cannot meet this burden on mere general assertions

that its officials did not discriminate or that they properly

performed their official duties. See Alexander v. Louisi

ana, supra, at 632; Jones v. Georgia, 389 U. S. 24, 25 (1967).

Rather, the State must demonstrate that “permissible ra

cially neutral selection criteria and procedures have produced

the monochromatic result.” Alexander v. Louisiana, supra,

at 632; see Washington v. Davis, supra, at 241.18

18 Our decisions in the context of Title VII “disparate treatment” have

explained the operation of prima facie burden of proof rules. See McDon

nell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U. S. 792 (1973); Texas Department of

14 BATSON v. KENTUCKY

The showing necessary to establish a prima facie case of

purposeful discrimination in selection of the venire may be

discerned in this Court’s decisions. E. g., Castaneda v.

Partida, 430 U. S. 482, 494-495 (1977); Alexander v. Louisi

ana, supra, at 631-632. The defendant initially must show

that he is a member of a racial group capable of being singled

out for differential treatment. Castaneda v. Partida,

supra, at 494. In combination with that evidence, a defend

ant may then make a prima facie case by proving that in the

particular jurisdiction members of his race have not been

summoned for jury service over an extended period of time.

Id., at 494. Proof of systematic exclusion from the venire

raises an inference of purposeful discrimination because the

“result bespeaks discrimination.” Hernandez v. Texas,

supra, at 482; see Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Hous

ing Corp., supra, at 266.

Since the ultimate issue is whether the State has discrimi

nated in selecting the defendant’s venire, however, the de

fendant may establish a prima facie case “in other ways than

by evidence of long-continued unexplained absence” of mem

bers of his race “from many panels.” Cassell v. Texas, 339

U. S. 282, 290 (1950) (plurality opinion). In cases involving

the venire, this Court has found a prima facie case on proof

that members of the defendant’s race were substantially un

derrepresented on the venire from which his jury was drawn,

and that the venire was selected under a practice providing

“the opportunity for discrimination.” Whitus v. Georgia,

385 U. S., at 552; see Castaneda v. Partida, supra, at 494;

Washington v. Davis, supra, at 241; Alexander v. Louisi

ana, supra, at 629-631. This combination of factors raises

the necessary inference of purposeful discrimination because

Community Affairs v. Burdine, 450 U. S. 248 (1981); United States Postal

Service Board of Governors v. Aikens, 460 U. S. 711 (1983). The party

alleging that he has been the victim of intentional discrimination carries the

ultimate burden of persuasion. Texas Department of Community Affairs

v. Burdine, supra, at 252-256.

BATSON v. KENTUCKY 15

the Court has declined to attribute to chance the absence of

black citizens on a particular jury array where the selection

mechanism is subject to abuse. When circumstances sug

gest the need, the trial court must undertake a “factual in

quiry” that “takes into account all possible explanatory fac

tors” in the particular case. Alexander v. Louisiana, supra,

at 630.

Thus, since the decision in Swain, this Court has recog

nized that a defendant may make a prima facie showing of

purposeful racial discrimination in selection of the venire by

relying solely on the facts concerning its selection in his case.

These decisions are in accordance with the proposition, artic

ulated in Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Corp.,

that “a consistent pattern of official racial discrimination” is

not “a necessary predicate to a violation of the Equal Protec

tion Clause. A single invidiously discriminatory govern

mental act” is not “immunized by the absence of such dis

crimination in the making of other comparable decisions.”

429 U . S., at 266, n. 14. For evidentiary requirements to

dictate that “several must suffer discrimination” before one

could object, McCray v. New York, 461 U . S., at 965 (M a r

s h a l l , J . , dissenting from denial of certiorari), would be in

consistent with the promise of equal protection to all.19

C

The standards for assessing a prima facie case in the con

text of discriminatory selection of the venire have been fully

articulated since Swain. See Castaneda v. Partida, supra,

at 494-495; Washington v. Davis, supra, at 241-242; Alexan

der v. Louisiana, supra, at 629-631. These principles sup

port our conclusion that a defendant may establish a prima

facie case of purposeful discrimination in selection of the petit

“ Decisions under Title VII also recognize that a person claiming that he

has been the victim of intentional discrimination may make out a prima

facie case by relying solely on the facts concerning the alleged discrimina

tion against him. See cases at supra, n. 19.

16 BATSON v. KENTUCKY

jury solely on evidence concerning the prosecutor’s exercise

of peremptory challenges at the defendant’s trial. To estab

lish such a case, the defendant first must show that he is a

member of a cognizable racial group, Castaneda v. Partida,

supra, at 494, and that the prosecutor has exercised peremp

tory challenges to remove from the venire members of the

defendant’s race. Second, the defendant is entitled to rely

on the fact, as to which there can be no dispute, that peremp

tory challenges constitute a jury selection practice that per

mits “those to discriminate who are of a mind to discrimi

nate.” Avery v. Georgia, supra, at 562. Finally, the

defendant must show that these facts and any other relevant

circumstances raise an inference that the prosecutor used

that practice to exclude the veniremen from the petit jury on

account of their race. This combination of factors in the

empanelling of the petit jury, as in the selection of the venire,

raises the necessary inference of purposeful discrimination.

In deciding whether the defendant has made the requisite

showing, the trial court should consider all relevant circum

stances. For example, a “pattern” of strikes against black

jurors included in the particular venire might give rise to an

inference of discrimination. Similarly, the prosecutor’s

questions and statements during voir dire examination and in

exercising his challenges may support or refute an inference

of discriminatory purpose. These examples are merely illus

trative. We have confidence that trial judges, experienced

in supervising voir dire, will be able to decide if the circum

stances concerning the prosecutor’s use of peremptory chal

lenges creates a prima facie case of discrimination against

black jurors.

Once the defendant makes a prima facie showing, the bur

den shifts to the State to come forward with a neutral

explanation for challenging black jurors. Though this re

quirement imposes a limitation in some cases on the full pe

remptory character of the historic challenge, we emphasize

that the prosecutor’s explanation need not rise to the level

BATSON v. KENTUCKY 17

justifying exercise of a challenge for cause. See McCray v.

Abrams, 750 F. 2d, at 1132; Booker v. Jobe, 775 F. 2d 762,

773 (CA6 1985), cert, pending 85-1028. But the prosecutor

may not rebut the defendant’s prima facie case of discrimina

tion by stating merely that he challenged jurors of the de

fendant’s race on the assumption—or his intuitive judg

ment—that they would be partial to the defendant because of

their shared race. Cf. Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S., at

598-599; see Thompson v. United States, ----- U. S. -------,

----- (Brennan, J., dissenting from denial of certiorari).

Just as the Equal Protection Clause forbids the States to ex

clude black persons from the venire on the assumption that

blacks as a group are unqualified to serve as jurors, supra, at

5, so it forbids the States to strike black veniremen on the

assumption that they will be biased in a particular case sim

ply because the defendant is black. The core guarantee of

equal protection, ensuring citizens that their State will not

discriminate on account of race, would be meaningless were

we to approve the exclusion of jurors on the basis of such as

sumptions, which arise solely from the jurors’ race. Nor

may the prosecutor rebut the defendant’s case merely by de

nying that he had a discriminatory motive or “affirming his

good faith in individual selections.” Alexander v. Louisi

ana, 405 U. S., at 632. If these general assertions were ac

cepted as rebutting a defendant’s prima facie case, the Equal

Protection Clause “would be but a vain and illusory require

ment.” Norris v. Alabama, supra, at 598. The prosecutor

therefore must articulate a neutral explanation related to the

particular case to be tried.20 The trial court then will have

20 The Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit observed in McCray v.

Abrams, 750 F. 2d, at 1132, that “[t]here are any number of bases” on

which a prosecutor reasonably may believe that it is desirable to strike a

juror who is not excusable for cause. As we explained in another context,

however, the prosecutor must give a “clear and reasonably specific” ex

planation of his “legitimate reasons” for exercising the challenges. Texas

Dept, of Community Affairs v. Burdine, 450 U. S. 248, 258 (1981).

18 BATSON v. KENTUCKY

the duty to determine if the defendant has established pur

poseful discrimination.21

IV

The State contends that our holding will eviscerate the fair

trial values served by the peremptory challenge. Conceding

that the Constitution does not guarantee a right to peremp

tory challenges and that Swain did state that their use ulti

mately is subject to the strictures of equal protection, the

State argues that the privilege of unfettered exercise of the

challenge is of vital importance to the criminal justice

system.

While we recognize, of course, that the peremptory chal

lenge occupies an important position in our trial procedures,

we do not agree that our decision today will undermine the

contribution the challenge generally makes to the administra

tion of justice. The reality of practice, amply reflected in

many state and federal court opinions, shows that the chal

lenge may be, and unfortunately at times has been, used to

discriminate against black jurors. By requiring trial courts

to be sensitive to the racially discriminatory use of peremp

tory challenges, our decision enforces the mandate of equal

protection and furthers the ends of justice.22 In view of the

21 In a recent Title VII sex discrimination case, we stated that “a finding

of intentional discrimination is a finding of fact” entitled to appropriate def

erence by a reviewing court. Anderson v. Bessemer City, 470 U. S .------

(1985). Since the trial judge’s findings in the context under consideration

here largely will turn on evaluation of credibility, a reviewing court ordi

narily should give those findings great deference. Id., a t ----- .

22 While we respect the views expressed in J ustice Marshall’s concur

ring opinion, concerning prosecutorial and judicial enforcement of our hold

ing today, we do not share them. The standard we adopt under the fed

eral Constitution is designed to ensure that a State does not use

peremptory challenges to strike any black juror because of his race. We

have no reason to believe that prosecutors will not fulfill their duty to exer

cise their challenges only for legitimate purposes. Certainly, this Court

may assume that trial judges, in supervising voir dire in light of our deci

sion today, will be alert to identify a prima facie case of purposeful dis

crimination. Nor do we think that this historic trial practice, which long

BATSON v. KENTUCKY 19

heterogeneous population of our nation, public respect for our

criminal justice system and the rule of law will be strength

ened if we ensure that no citizen is disqualified from jury

service because of his race.

Nor are we persuaded by the State’s suggestion that our

holding will create serious administrative difficulties. In

those states applying a version of the evidentiary standard

we recognize today, courts have not experienced serious ad

ministrative burdens,23 and the peremptory challenge system

has survived. We decline, however, to formulate particular

procedures to be followed upon a defendant’s timely objection

to a prosecutor’s challenges.24

V

In this case, petitioner made a timely objection to the pros

ecutor’s removal of all black persons on the venire. Because

the trial court flatly rejected the objection without requiring

the prosecutor to give an explanation for his action, we re

mand this case for further proceedings. If the trial court de

cides that the facts establish, prima facie, purposeful dis

crimination and the prosecutor does not come forward with a

has served the selection of an impartial jury, should be abolished because of

an apprehension that prosecutors and trial judges will not perform con

scientiously their respective duties under the Constitution.

23 For example, in People v. Hall, 35 Cal. 3d 161, 672 P. 2d 854 (1983),

the California Supreme Court found that there was no evidence to show

that procedures implementing its version of this standard, imposed five

years earlier, were burdensome for trial judges.

24 In light of the variety of jury selection practices followed in our state

and federal trial courts, we make no attempt to instruct these courts how

best to implement our holding today. For the same reason, we express no

view on whether it is more appropriate in a particular case, upon a finding

of discrimination against black jurors, for the trial court to discharge the

venire and select a new jury from a panel not previously associated with

the case, see Booker v. Jahe, 775 F. 2d, at 773, or to disallow the discrimi

natory challenges and resume selection with the improperly challenged ju

rors reinstated on the venire, see United States v. Robinson, 421 F. Supp.

467, 474 (Conn. 1976), mandamus granted sub nom. United States v. New

man, 549 F. 2d 240 (CA2 1977).

20 BATSON v. KENTUCKY

neutral explanation for his action, our precedents require

that petitioner’s conviction be reversed. E. g., Whitus v.

Georgia, 385 U. S., at 549-550; Hernandez v. Texas, supra,

at 482; Patton v. Mississippi, 332 U. S., at 469.25

It is so ordered.

25 To the extent that anything in Swain v. Alabama, 380 U. S. 202

(1965), is contrary to the principles we articulate today, that decision is

overruled.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 84-6263

JAMES KIRKLAND BATSON, PETITIONER

v. KENTUCKY

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF KENTUCKY

[April 30, 1986]

J ustice White , concurring.

The Court overturns the principal holding in Swain v.

Alabama, 380 U. S. 202 (1965), that the Constitution does

not require in any given case an inquiry into the prosecutor’s

reasons for using his peremptory challenges to strike blacks

from the petit jury panel in the criminal trial of a black

defendant and that in such a case it will be presumed that

the prosecutor is acting for legitimate trial-related reasons.

The Court now rules that such use of peremptory challenges

in a given case may, but does not necessarily, raise an infer

ence, which the prosecutor carries the burden of refuting,

that his strikes were based on the belief that no black citizen

could be a satisfactory juror or fairly try a black defendant.

I agree that, to this extent, Swain should be overruled. I

do so because Swain itself indicated that the presumption

of legitimacy with respect to the striking of black venire per

sons could be overcome by evidence that over a period of time

the prosecution had consistently excluded blacks from petit

juries.* This should have warned prosecutors that using

peremptories to exclude blacks on the assumption that no

*Nor would it have been inconsistent with Swain for the trial judge to

invalidate peremptory challenges of blacks if the prosecutor, in response to

an objection to his strikes, stated that he struck blacks because he believed

they were not qualified to serve as jurors, especially in the trial of a black

defendant.

2 BATSON v. KENTUCKY

black juror could fairly judge a black defendant would violate

the Equal Protection Clause.

It appears, however, that the practice of peremptorily

eliminating blacks from petit juries in cases with black

defendant remains widespread, so much so that I agree that

an opportunity to inquire should be afforded when this oc

curs. If the defendant objects, the judge, in whom the

Court puts considerable trust, may determine that the pros

ecution must respond. If not persuaded otherwise, the

judge may conclude that the challenges rest on the belief that

blacks could not fairly try a black defendant. This, in effect,

attributes to the prosecutor the view that all blacks should be

eliminated from the entire venire. Hence, the Court’s prior

cases dealing with jury venires rather than petit juries are

not without relevance in this case.

The Court emphasizes that using peremptory challenges to

strike blacks does not end the inquiry; it is not unconstitu

tional, without more, to strike one or more blacks from the

jury. The judge may not require the prosecutor to respond

at all. If he does, the prosecutor, who in most cases has had

a chance to voir dire the prospective jurors, will have an

opportunity to give trial-related reasons for his strikes—

some satisfactory ground other than the belief that black

jurors should not be allowed to judge a black defendant.

Much litigation will be required to spell out the contours of

the Court’s Equal Protection holding today, and the signifi

cant effect it will have on the conduct of criminal trials cannot

be gainsaid. But I agree with the Court that the time has

come to rule as it has, and I join its opinion and judgment.

I would, however, adhere to the rule announced in

DeStefano v. Woods, 392 U. S. 631 (1968), that Duncan v.

Louisiana, 391 U. S. 145 (1968), which held that the States

cannot deny jury trials in serious criminal cases, did not

require reversal of a state conviction for failure to grant a

jury trial where the trial began prior to the date of the

announcement in the Duncan decision. The same result was

BATSON v. KENTUCKY 3

reached in DeStefano with respect to the retroactivity of

Bloom v. Illinois, 391 U. S. 194 (1968), as it was in Daniel v.

Louisiana, 420 U. S. 31 (1975)(per curiam), with respect to

the decision in Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U. S. 522 (1975),

holding that the systematic exclusion of women from jury

panels violated the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 84-6263

JAMES KIRKLAND BATSON, PETITIONER

v. KENTUCKY

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF KENTUCKY

[April 30, 1986]

J ustice Marshall, concurring.

I join J ustice Powell’s eloquent opinion for the Court,

which takes a historic step toward eliminating the shameful

practice of racial discrimination in the selection of juries.

The Court’s opinion cogently explains the pernicious nature

of the racially discriminatory use of peremptory challenges,

and the repugnancy of such discrimination to the Equal Pro

tection Clause. The Court’s opinion also ably demonstrates

the inadequacy of any burden of proof for racially discrimina

tory use of peremptories that requires that “justice . . . sit

supinely by” and be flouted in case after case before a remedy

is available.1 I nonetheless write separately to express my

views. The decision today will not end the racial discrimina

tion that peremptories inject into the jury-selection process.

That goal can be accomplished only by eliminating peremp

tory challenges entirely.

I

A little over a century ago, this Court invalidated a state

statute providing that black citizens could not serve as ju

rors. Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 (1880).

State officials then turned to somewhat more subtle ways of

1 Commonwealth v. Martin, 461 Pa. 289, 299, 336 A. 2d 290, 295 (1975)

(Nix, J ., dissenting), quoted in McCray v. New York, 461 U. S. 961, 965,

n. 2 (1983) (Marshall, J., dissenting from denial of certiorari).

2 BATSON v. KENTUCKY

keeping blacks off jury venires. See Swain v. Alabama, 380

U. S. 202, 231-238 (1965) (Goldberg, J., dissenting); Kuhn,

Jury Discrimination: The Next Phase, 41 S. Cal. L. Rev. 235

(1968); see also J. Van Dyke, Jury Selection Procedures

155-157 (1977) (hereinafter Van Dyke). Although the means

used to exclude blacks have changed, the same pernicious

consequence has continued.

Misuse of the peremptory challenge to exclude black jurors

has become both common and flagrant. Black defendants

rarely have been able to compile statistics showing the extent

of that practice, but the few cases setting out such figures are

instructive. See United States v. Carter, 528 F. 2d 844, 848

(CA8 1975) (in 15 criminal cases in 1974 in the Western Dis

trict of Missouri involving black defendants, prosecutors pe

remptorily challenged 81% of black jurors), cert, denied, 425

U. S. 961 (1976); United States v. McDaniels, 379 F. Supp.

1243 (ED La. 1974) (in 53 criminal cases in 1972-1974 in East

ern District of Louisiana involving black defendants, federal

prosecutors used 68.9% of their peremptory challenges

against black jurors, who made up less than one quarter of

the venire); McKinney v. Walker, 394 F. Supp. 1015,

1017-1018 (SC 1974) (in 13 criminal trials in 1970-1971 in

Spartansburg County, South Carolina, involving black de

fendants, prosecutors peremptorily challenged 82% of black

jurors), affirmance order, 529 F. 2d 516 (CA4 1975).2 Pros

ecutors have explained to courts that they routinely strike

black jurors, see State v. Washington, 375 So. 2d 1162,

1163-1164 (La. 1979). An instruction book used by the pros

ecutor’s office in Dallas County, Texas, explicitly advised

prosecutors that they conduct jury selection so as to elimi

nate “ ‘any member of a minority group.’”3 In 100 felony

2See also Harris v. Texas, 467 U. S. 1261 (1984) (Marshall, J., dis

senting from denial of certiorari); Williams v. Illinois, 466 U. S. 981 (1984)

(Marshall, J., dissenting from denial of certiorari).

3 Van Dyke, supra, at 152, quoting Texas Observer, May 11, 1973, p. 9,

col. 2. An earlier jury-selection treatise circulated in the same county in-

BATSON v. KENTUCKY 3

trials in Dallas County in 1983-1984, prosecutors perempto

rily struck 405 out of 467 eligible black jurors; the chance of a

qualified black sitting on a jury was one-in-ten, compared to

one-in-two for a white.4

The Court’s discussion of the utter unconstitutionality of

that practice needs no amplification. This Court explained

more than a century ago that “ ‘in the selection of jurors to

pass upon [a defendant’s] life, liberty, or property, there

shall be no exclusion of his race, and no discrimination against

them, because of their color.’” Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S.

370, 394 (1881), quoting Virginia v. Rives, 100 U. S. 313, 323

(1880). J u s t ic e R e h n q u is t , dissenting, concedes that ex

clusion of blacks from a jury, solely because they are black, is

at best based upon “crudely stereotypical and . . . in many

cases hopelessly mistaken” notions. Post, at 5. Yet the

Equal Protection Clause prohibits a State from taking any ac

tion based on crude, inaccurate racial stereotypes—even an

action that does not serve the State’s interests. Exclusion of

blacks from a jury, solely because of race, can no more be jus

tified by a belief that blacks are less likely than whites to con

sider fairly or sympathetically the State’s case against a black

defendant than it can be justified by the notion that blacks

lack the “intelligence, experience, or moral integrity,” Neal,

supra, at 397, to be entrusted with that role.

II

I wholeheartedly concur in the Court’s conclusion that use

of the peremptory challenge to remove blacks from juries, on

the basis of their race, violates the Equal Protection Clause.

I would go further, however, in fashioning a remedy ade

quate to eliminate that discrimination. Merely allowing de-

structed prosecutors: “Do not take Jews, Negroes, Dagos, Mexicans or a

member of any minority race on a jury, no matter how rich or how well

educated.” Quoted in Dallas Morning News, March 9, 1986, p. 29, col. 1.

4 Dallas Morning News, March 9, 1986, p. 1, col. 1; see also Comment, A

Case Study of the Peremptory Challenge: A Subtle Strike at Equal Protec

tion and Due Process, 18 St. Louis U. L. J. 662 (1974).

4 BATSON v. KENTUCKY

fendants the opportunity to challenge the racially discrimina

tory use of peremptory challenges in individual cases will not

end the illegitimate use of the peremptory challenge.

Evidentiary analysis similar to that set out by the Court,

ante, at 17, has been adopted as a matter of state law in

States including Massachusetts and California. Cases from

those jurisdictions illustrate the limitations of the approach.

First, defendants cannot attack the discriminatory use of pe

remptory challenges at all unless the challenges are so fla

grant as to establish a prima facie case. This means, in those

States, that where only one or two black jurors survive the

challenges for cause, the prosecutor need have no compunc

tion about striking them from the jury because of their race.

See Commonwealth v. Robinson, 382 Mass. 189, 195, 415

N. E. 2d 805, 809-810 (1981) (no prima facie case of dis

crimination where defendant is black, prospective jurors in

clude three blacks and one Puerto Rican, and prosecutor ex

cludes one for cause and strikes the remainder peremptorily,

producing all-white jury); People v. Rousseau, 129 Cal. App.

3d 526, 536-537, 179 Cal. Rptr. 892, 897-898 (1982) (no prima

facie case where prosecutor peremptorily strikes only two

blacks on jury panel). Prosecutors are left free to discrimi

nate against blacks in jury selection provided that they hold

that discrimination to an “acceptable” level.

Second, when a defendant can establish a prima facie case,

trial courts face the difficult burden of assessing prosecutors’

motives. See King v. County of Nassau, 581 F. Supp. 493,

501-502 (EDNY 1984). Any prosecutor can easily assert fa

cially neutral reasons for striking a juror, and trial courts are

ill-equipped to second-guess those reasons. How is the court

to treat a prosecutor’s statement that he struck a juror be

cause the juror had a son about the same age as defendant,

see People v. Hall, 35 Cal. 3d 161, 672 P. 2d 854 (1983), or

seemed “uncommunicative,” King, supra, at 498, or “never

cracked a smile” and, therefore “did not possess the sensitiv

ities necessary to realistically look at the issues and decide

BATSON v. KENTUCKY 5

the facts in this case,” Hall, supra, at 165, 672 P. 2d, at 856?

If such easily generated explanations are sufficient to dis

charge the prosecutor’s obligation to justify his strikes on

nonracial grounds, then the protection erected by the Court

today may be illusory.

Nor is outright prevarication by prosecutors the only dan

ger here. “[I]t is even possible that an attorney may lie to

himself in an effort to convince himself that his motives are

legal.” King, supra, at 502. A prosecutor’s own conscious

or unconscious racism may lead him easily to the conclusion

that a prospective black juror is “sullen,” or “distant,” a

characterization that would not have come to his mind if a

white juror had acted identically. A judge’s own conscious

or unconscious racism may lead him to accept such an ex

planation as well supported. As J u s t ic e R e h n q u is t con

cedes, prosecutors’ peremptories are based on their “seat-of-

the-pants instincts” as to how particular jurors will vote.

Post, at 5; see also the C h i e f J u s t ic e ’s dissenting opinion,

post, at 12-13. Yet “seat-of-the-pants instincts” may often

be just another term for racial prejudice. Even if all parties

approach the Court’s mandate with the best of conscious in

tentions, that mandate requires them to confront and over

come their own racism on all levels—a challenge I doubt all of

them can meet. It is worth remembering that “114 years

after the close of the War Between the States and nearly 100

years after Strauder, racial and other forms of discrimination

still remain a fact of life, in the administration of justice as in

our society as a whole.” Rose v. Mitchell, 443 U. S. 545,

558-559 (1979), quoted in Vasquez v. Hillery, 474 U. S .----- ,

The inherent potential of peremptory challenges to distort

the jury process by permitting the exclusion of jurors on ra

cial grounds should ideally lead the Court to ban them en

tirely from the criminal justice system. See Van Dyke, at

167-169; Imlay, Federal Jury Reformation: Saving a Demo-

6 BATSON v. KENTUCKY

cratic Institution, 6 Loyola (LA) L. Rev. 247, 269-270 (1973).

Justice Goldberg, dissenting in Swain, emphasized that

“[wjere it necessary to make an absolute choice between the

right of a defendant to have a jury chosen in conformity with

the requirements of the Fourteenth Amendment and the

right to challenge peremptorily, the Constitution compels a

choice of the former.” 380 U. S., at 244. I believe that this

case presents just such a choice, and I would resolve that

choice by eliminating peremptory challenges entirely in crim

inal cases.

Some authors have suggested that the courts should ban

prosecutors’ peremptories entirely, but should zealously

guard the defendant’s peremptory as “essential to the fair

ness of trial by jury ,” Lewis v. United States, 146 U. S. 370,

376 (1892), and “one of the most important of the rights se

cured to the accused,” Pointer v. United States, 151 U. S.

396, 408 (1894). See Van Dyke, at 167; Brown, McGuire, &

Winters, The Peremptory Challenge as a Manipulative De

vice in Criminal Trials: Traditional Use or Abuse, 14 New

England L. Rev. 192 (1978). I would not find that an accept

able solution. Our criminal justice system “requires not only

freedom from any bias against the accused, but also from any

prejudice against his prosecution. Between him and the

state the scales are to be evenly held.” Hayes v. Missouri,

120 U. S. 68, 70 (1887). We can maintain that balance, not

by permitting both prosecutor and defendant to engage in ra

cial discrimination injury selection, but by banning the use of

peremptory challenges by prosecutors and by allowing the

States to eliminate the defendant’s peremptory as well.

Much ink has been spilled regarding the historic impor

tance of defendants’ peremptory challenges. The approving

comments of the Lewis and Pointer Courts are noted above;

the Swain Court emphasized the “very old credentials” of the

peremptory challenge, 380 U. S., at 212, and cited the “long

and widely held belief that peremptory challenge is a neces

sary part of trial by jury.” Id ., at 219. But this Court has

BATSON v. KENTUCKY 7

also repeatedly stated that the right of peremptory challenge

is not of constitutional magnitude, and may be withheld alto

gether without impairing the constitutional guarantee of im

partial jury and fair trial. Frazier v. United States, 335

U. S. 497, 505, n. 11 (1948); United States v. Wood, 299 U. S.

123, 145 (1936); Stilson v. United States, 250 U. S. 583, 586

(1919); see also Swain, supra, at 219. The potential for ra

cial prejudice, further, inheres in the defendant’s challenge as

well. If the prosecutor’s peremptory challenge could be

eliminated only at the cost of eliminating the defendant’s

challenge as well, I do not think that would be too great a

price to pay.

I applaud the Court’s holding that the racially discrimina

tory use of peremptory challenges violates the Equal Protec

tion Clause, and I join the Court’s opinion. However, only

by banning peremptories entirely can such discrimination be

ended.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 84-6263

JAMES KIRKLAND BATSON, PETITIONER

v. KENTUCKY

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF KENTUCKY

[April 30, 1986]

J u s t ic e S t e v e n s , with whom J u s t ic e B r e n n a n joins,

concurring.

In his dissenting opinion, T h e C h i e f J u s t ic e correctly

identifies an apparent inconsistency between my criticism of

the Court’s action in Colorado v. Connelly, 474 U. S . -----

(1986) (memorandum of B r e n n a n , J., joined by S t e v e n s ,

J.), and New Jersey v. T. L. 0 ., 468 U . S. 1214 "(1984) (S t e

v e n s , J., dissenting)—cases in which the Court directed the

State to brief and argue questions not presented in its peti

tion for certiorari—and our action today in finding a violation

of the Equal Protection Clause despite the failure of petition

er’s counsel to rely on that ground of decision. Post, at 4-5,

nn. 1, and 2. In this case, however—unlike Connelly and

T. L. 0 .—the party defending the judgment has explicitly

rested on the issue in question as a controlling basis for af

firmance. In defending the Kentucky Supreme Court’s

judgment, Kentucky’s Assistant Attorney General empha

sized the State’s position on the centrality of the Equal Pro

tection issue:

“Mr. Chief Justice, and may it please the Court, the

issue before this Court today is simply whether Swain

versus Alabama should be reaffirmed. . . .

. .W e believe that it is the Fourteenth Amendment

that is the item that should be challenged, and presents

2 BATSON v. KENTUCKY

perhaps an address to the problem. Swain dealt pri

marily with the use of peremptory challenges to strike

individuals who were of a cognizable or identifiable

group.

“Petitioners show no case other than the State of Cali

fornia’s case dealing with the use of peremptories

wherein the Sixth Amendment was cited as authority for

resolving the problem. So, we believe that the Four

teenth Amendment is indeed the issue. That was the

guts and primarily the basic concern of Swain.

“In closing, we believe that the trial court of Kentucky

and the Supreme Court of Kentucky have firmly em

braced Swain, and we respectfully request that this

Court affirm the opinion of the Kentucky court as well as

to reaffirm Swain versus Alabama.” 1

In addition to the party’s reliance on the Equal Protection

argument in defense of the judgment, several amici curiae

also addressed that argument. For instance, the argument

in the brief filed by the Solicitor General of the United States

begins:

“PETITIONER DID NOT ESTABLISH THAT HE

WAS DEPRIVED OF A PROPERLY CONSTITUTED

PETIT JURY OR DENIED EQUAL PROTECTION

OF THE LAWS

“A. Under Swain v. Alabama A Defendant Cannot Es

tablish An Equal Protection Violation By Showing

Only That Black Veniremen Were Subjected To Pe

remptory Challenge By The Prosecution In His

Case”2

>Tr. of Oral Arg., 27-28, 43.

2 Brief for United States as Amicus Curiae 7.

BATSON v. KENTUCKY 3

Several other amici similarly emphasized this issue.3

In these circumstances, although I suppose it is possible

that reargument might enable some of us to have a better in

formed view of a problem that has been percolating in the

courts for several years,4 I believe the Court acts wisely in

resolving the issue now on the basis of the arguments that

3 The argument section of the brief for the National District Attorneys

Association, Inc., as amicus curiae in support of respondent begins as

follows:

“This Court should conclude that the prosecutorial peremptory challenges

exercised in this case were proper under the fourteenth amendment equal

protection clause and the sixth amendment. This Court should further de

termine that there is no constitutional need to change or otherwise modify

this Court’s decision in Swain v. Alabama." Id., at 5.

Am ici supporting the petitioner also emphasized the importance of the

equal protection issue. See, e. g., Brief for NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, American Jewish Committee, and American Jewish

Congress as Amici Curiae, 24-36; Brief for Lawyers’ Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law as Amicus Curiae, 11-17; Brief for Elizabeth Holtzman

as Amicus Curiae, 13.

4 See McCray v. New York, 461 U. S. 961 (1983) (opinion of Stevens,

J ., respecting denial of certiorari); id., at 963 (Marshall, J., dissenting

from denial of certiorari).

The eventual federal habeas corpus disposition of McCray, of course,

proved to be one of the landmark cases that made the issues in this case

ripe for review. McCray v. Abram.s, 750 F. 2d 1113 (CA2 1984), petition

for cert, pending. See also Batson’s cert, petition, 5-7 (relying heavily on

McCray as a reason for review). In McCray, as in almost all opinions that

have considered similar challenges, the Court of Appeals for the Second

Circuit explicitly addressed the equal protection issue and the viability of

Swain. Id., at 1118-1124. The pending petition for certiorari in McCray

similarly raises the equal protection question that has long been central to