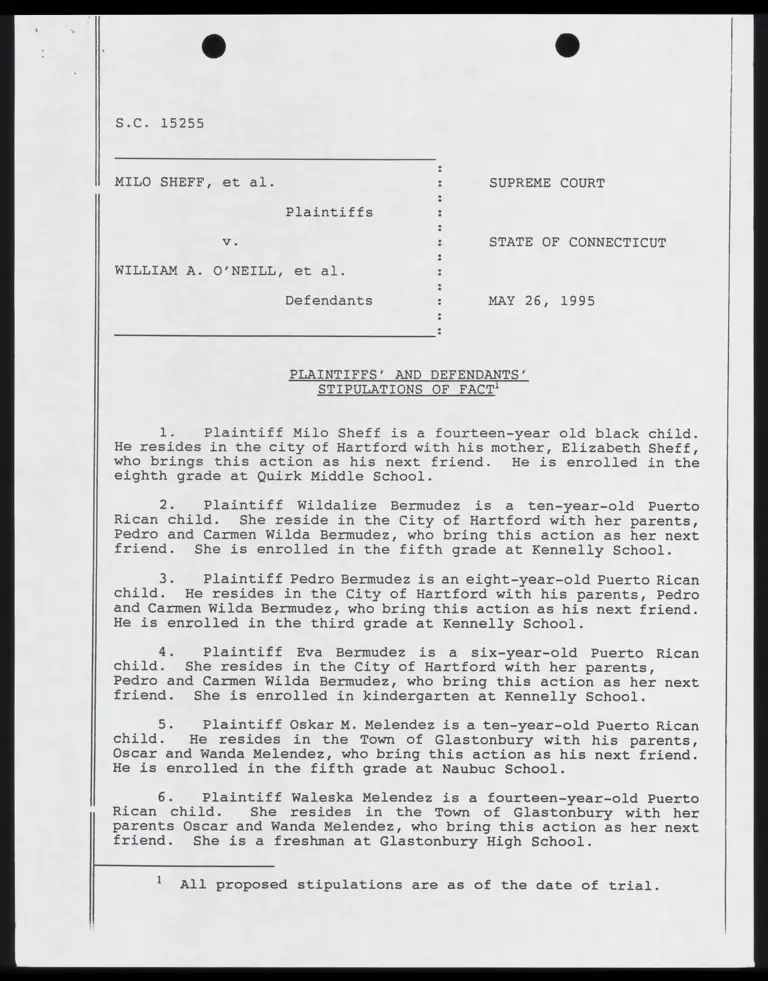

Plaintiffs' and Defendants' Stipulation of Fact

Public Court Documents

May 26, 1995

24 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Plaintiffs' and Defendants' Stipulation of Fact, 1995. 3c1eb399-a146-f011-877a-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0c70cdcd-cab6-4a8d-b551-01096b6e15eb/plaintiffs-and-defendants-stipulation-of-fact. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

§.C.:15255

MILO SHEFF, et al. SUPREME COURT

Plaintiffs

yo STATE OF CONNECTICUT

WILLIAM A. O'NEILL, et al.

Defendants MAY 26, 1995

PLAINTIFFS’ AND DEFENDANTS’

STIPULATIONS OF FACT!

1. Plaintiff Milo Sheff is a fourteen-year old black child.

He resides in the city of Hartford with his mother, Elizabeth Sheff,

who brings this action as his next friend. He is enrolled in the

eighth grade at Quirk Middle School.

2. Plaintiff Wildalize Bermudez is a ten-year-old Puerto

Rican child. She reside in the City of Hartford with her parents,

Pedro and Carmen Wilda Bermudez, who bring this action as her next

friend. She is enrolled in the fifth grade at Kennelly School.

3. Plaintiff Pedro Bermudez is an eight-year-old Puerto Rican

child. He resides in the City of Hartford with his parents, Pedro

and Carmen Wilda Bermudez, who bring this action as his next friend.

He is enrolled in the third grade at Kennelly School.

4. Plaintiff Eva Bermudez is a six-year-old Puerto Rican

child. She resides in the City of Hartford with her parents,

Pedro and Carmen Wilda Bermudez, who bring this action as her next

friend. She is enrolled in kindergarten at Kennelly School.

5. Plaintiff Oskar M. Melendez is a ten-year-old Puerto Rican

child. He resides in the Town of Glastonbury with his parents,

Oscar and Wanda Melendez, who bring this action as his next friend.

He is enrolled in the fifth grade at Naubuc School.

6. Plaintiff Waleska Melendez is a fourteen-year-old Puerto

Rican child. She resides in the Town of Glastonbury with her

parents Oscar and Wanda Melendez, who bring this action as her next

friend. She is a freshman at Glastonbury High School.

1 All proposed stipulations are as of the date of trial.

-iD

7. Plaintiff Martin Hamilton is a thirteen-year-old black

child. He resides in the City of Hartford with his mother, Virginia

Pertillar, who brings this action as his next friend. He is

enrolled in the seventh grade at Quirk Middle School.

8. Plaintiff Janelle Hughley is a 2 year-old black child.

She resides in the City of Hartford with her mother, Jewell Hughley,

who brings this action as her next friend.

9. Plaintiff Neiima Best is a fifteen-year old black child.

She resides in the City of Hartford with her mother, Denise Best,

who brings this action as her next friend. She is enrolled as a

sophomore at Northwest Catholic High School in West Hartford.

10. Plaintiff Lisa Laboy is an eleven-year-old Puerto Rican

child. She resides in the City of Hartford with her mother, Adria

Laboy, who brings this action as her next friend. She is enrolled

in the fifth grade at Burr School.

11. Plaintiff David William Harrington is a thirteen-year-old

white child. He resides in the City of Hartford with his parents

Karen and Leo Harrington, who bring this action as his next friend.

He is enrolled in ‘the seventh grade at Quirk Middle School.

12. Plaintiff Michael Joseph Harrington is a ten-year-old

white child. He resides in the City of Hartford with his parents

Karen and Leo Harrington, who bring this action as his next friend.

He is enrolled in the fifth grade at Noah Webster Elementary School.

13. Plaintiff Rachel Leach is a ten-year-old white child. She

resides in the Town of West Hartford with her parents Eugene Leach

and Kathleen Frederick, who bring this action as her next friend.

She is enrolled in the fifth grade at Whiting Lane School.

14. Plaintiff Joseph Leach is a nine-year-old white child. He

resides in the Town of West Hartford with her parents Eugene Leach

and Kathleen Frederick, who bring this action as his next friend.

He is enrolled in the third grade at Whiting Lane School.

15. Plaintiff Erica Connolly is a nine-year-old white child.

She resides in the City Hartford with her parents Carol Vinick and

Tom Connolly, who bring this action as her next friend. She is

enrolled in the fourth grade at Dwight School.

16. Plaintiff Tasha Connolly is a six-year-old white child.

She resides in the City Hartford with her parents Carol Vinick and

Tom Connolly, who bring this action as her next friend. She is

enrolled in the first grade at Dwight School.

17. Michael Perez is a fifteen-year-old Puerto Rican child. He

resides in the City Hartford with his father, Danny Perez, who bring

this action as his next friend. He is enrolled as a sophomore at

Hartford Public High School.

18. Dawn Perez is a thirteen-year-old Puerto Rican child. She

resides in the City Hartford with her father, Danny Perez, who bring

this action as her next friend. She is enrolled in the eighth grade

at Quirk Middle School.

19. Among the plaintiffs are five black children, seven Puerto

Rican children and six white children. At least one of the children

lives in families whose income falls below the official poverty

line; five are limited English proficient; six live in single-parent

families.

20. Defendant William O'Neill or his successor is the

Governor of the State of Connecticut.

21. Defendant State Board of Education of the State of

Connecticut (hereafter "the State Board" or the State Board of

Education") is charged with the overall supervision and control

of the educational interest of the State, including elementary and

secondary education, pursuant to C.G.S. §10-4.

22. Defendants Abraham Glassman, A. Walter Esdaile, Warren

J. Foley, Rita Hendel, John Mannix, and Julia Rankin were, at one

time, the members of the State Board of Education and these

individuals have been succeeded by others as members of the State

Board of Education.

23. Defendant Gerald N. Tirozzi or his successor is the

Commissioner of Education for the State of Connecticut.

24. Defendant Francis L. Borges or his successor is the

Treasurer of the State of Connecticut.

25. Defendant J. Edward Caldwell or his successor is the

Comptroller of the State of Connecticut.

26. Ninety-two percent of the students in the Hartford schools

are members of minority groups. (Tables 1 and 2, Pls’ Ex. 163 at

31, 38; Natriello p. 82; Pils’ Ex. 85 p. vii)

27. African Americans and Latinos together constitute more

than 90%, or 23,283, of the 25,716 students in the Hartford public

schools (Pls’ Ex. 219 at 2).

28. In an average Hartford class of 23.4 students, 21.6 will

be members of minority groups. (Table 2, Pls’ Ex. 163 at 38)

29. Hartford has the highest percentage of minority students

in the state. (Natriello p. B82; Table 1, Pls’ Ex. 163 at 31)

30. In 1991-92, fourteen of Hartford's twenty-five elementary

schools had less than 2% white enrollment. (Defs’ Exs. 23.1-23.25)

31. As of 1990, eighteen of the surrounding suburbs had less

than 10% minority population, ten of the surrounding suburbs have

less than 5% minority population, 18 out of the 21 suburbs have less

than 4% Black population, and 12 towns have less than 2% Black

population. (Pls’ Ex. 137 atl, 7; Pls’ Ex. 138; Steahr pp. 99-101)

32. Some of Connecticut's school districts, including

Hartford, serve higher percentages of African American and Latino

students than others.

33. In 1986, 12.1% of Connecticut’s school age population was

black and 8.5% was Hispanic.

34. 1987-88 figures for total school population and percent

minority for the towns listed below are:

Total School Pop. ¥ Minority

Hartford 20,058 90.5

Bloomfield 2:55%5 69.0

Avon 2,068 3.8

Canton 1,18° 3.2

East Granby 666 2.3

East Hartford 5,905 20.6

East Windsor 1,267 8.5

Ellington 1,855 2.3

Farmington 2,608 7.7

Glastonbury 4,463 5.4

Granby 1,528 3.5

Manchester 7,084 11.2)

Newington 3,801 6.4

Rocky Hill 1,807 5.9

Simsbury 4,039 6.5

South Windsor 3,648 9.3

Suffield 1,772 4.0

Vernon 4,457 6.4

West Hartford 7,424 15.7

Wethersfield 2,997 3.3

Windsor 4,235 30.8

Windsor Locks 1,642 4.0

35. Sixteen suburbs have less than 3% Latino enrollment.

(Pls’ Ex. 85 pp. 18-21)

36. As of 1991-92, two districts, Hartford and Bloomfield, had

more than five percent African Americans and Latinos on their

professional staffs. (Defs’ Exs. 14.1-14.22)

37. During the 1980s, Hartford experienced the largest

increase of the non-white population -- an increase of 21,499

persons -- of all the towns in the Hartford metropolitan area.

(Defs’ Ex. 1.3)

38. In 1992, there were seven suburban school districts with

a minority enrollment in excess of 10%, namely:

% minority enrollment % increase between 1980 & 1990

1. Bloomfield 83.5% 32.4%

2. East Hartford 38.1% 27.3%

3. Windsor 36.9% 15.7%

4. Manchester 19% 12.8%

5. West Hartford 17.2% 10.7%

6. Vernon 11.6% 7.8%

7. East Windsor 10.3% 4.1% oe

(Calvert pp. 33-35; Defs’' Ex. 2.6 Rev., 2.7 Rev.).

39. In 1963, 36.3% of the students in the Hartford public

schools were African-American. (Pls’ Ex. 19, p. 30 (Table 4.1.14))

40. In 1992, African-American students in the Hartford public

schools made up 43.1% of the total student population, an increase

of 6.8% from 1963. {(Defs’ Ex. 2.6 and 2.12))

41. In 1963, there were 599 Latino students in the Hartford

public schools. (Pls’ Ex. 19, p. 30 (Table 4.1.14)

42. By 1992, there were 12,564 Latino students in the

Hartford public schools -- an increase of 1,997.5%. (Defs’ Ex. 2.15)

43. From 1963 to 1992, the African-American student population

in the Hartford public schools increased from 9,061 to 11,201, an

increase over that period of 23.6%. (Defs’ Ex. 2.12)

44. From 1980 to 1992, the African-American student population

in the Hartford public schools decreased from 12,393 to 11,201, a

decrease of 9.6% over that period. (Defs’ Ex. 2.12)

45. The Harvard Study correctly projected the decline in

Hartford's African-American student population, the only significant

minority group in Hartford in 1965, but failed to predict the

massive influx of Latino students, primarily of Puerto Rican

ancestry. (Defs’ Ex. 13.2, p. 2; Gordon pp. 98-99)

46. From 1980 to 1992, African-American student population in

the 21 suburban towns increased by 62.5% from 3,925 to 6,380. (Defs’

BX. 2.12)

47. During the 1980s, Hartford experienced the greatest out

migration of white residents, with a net out migration of 18,176.

{Defs’ Ex. .1.3)

48. According to a study prepared for the Governor's

Commission between 1985 and 1990, there was a "significant increase

in the percentage of minority students in the five major

metropolitan areas studied: Bridgeport, New Haven,

Bloomfield/Hartford, Norwalk/Stamford, New London, and the towns

nearby.” (Pls! Ex. 73 at 4)

49. Sixty-three percent of the students in the Hartford school

system participate in the free and reduced lunch program. (Pls’ Ex.

219; Table 2, Pils’ Ex. 163 at 38)

50. In an average Hartford class of 23.4 students, 14.8 will

be participating in the free and reduced lunch program. (Table 2,

Pls’ Bx. 163 at. 38)

51. Thirteen percent of all children born in the city of

Hartford are at low birth weight, 13% are born to drug-addicted

mothers, and 23% are born to mothers who are teenagers. (Table 2,

Pls’ Ex. 163 'at 38)

52. In an average Hartford class of 23.4 students, 3 will have

been born at a low birthweight, 3 will have been born to drug

addicted mothers, and 5.4 will have been born to teen mothers.

(Table 2, Pls’ Ex. 1563 at 38)

53. More than sixty-four percent of the parents of Hartford

school age children with children under eighteen are single parent

households. (Table 2, Pls’ Ex. 163 at 38)

54. In an average Hartford class of 23.4 students, 15.1 will

come from single parent households. (Table 2, Pls’ Ex. 163 at 38)

55. A single parent home is an indicator of a disadvantage for

students. (Natriello p. 71)

56. In an average Hartford class of 23.4 students, 9.5 will

come from families where the parents have less than a high school

education. (Table 2, Pls’ Ex. 163 at 38)

57. Fifty-one percent of Hartford students are from a home in

which a language other than English is spoken. (Table 2, Pls’ Ex.

163 at 38)

58. In an average Hartford class of 23.4 students, 12 will

come from a home in which a language other than English is spoken.

{Table 2, Pls’ Ex. 163 at 38)

53. Students with limited English proficiency have more

difficulty succeeding in school. (Natriello p. 84)

60. Fifteen percent of the Hartford population and 41.3% of

the parents with school age children have experienced crime within

the year. (Table 2, Pls’ Ex. 163 at 38)

61. In an average Hartford class of 23.4 students, 3.6 will

have been a victim of crime and 9.7 will live in a household that

has experienced crime within the year. (Table 2, Pls’ Ex. 163 at

38)

62. Twenty-eight percent of Hartford elementary students do

not return to the same school the next year. (Natriello p. 78; Pls’

Ex. 163 at 27)

63. Fifteen of the 21 surrounding districts have less than 10%

of their students on the free and reduced lunch program. (Pls’ Ex.

163 p. 153)

64. Hartford’s rate of poverty is greater than the rate among

students in any of the twenty-one surrounding districts. (Pls’ Ex.

163 at 152 and Figure 33, at 153: Rindone p. 121)

65. Hartford found itself last in comparison to the twenty-one

surrounding communities in 1980 on every single socio-economic

indicator, and it remained in last place ten years later in 1990.

(Rindone p. 110; Defs’ Ex. 8.1 and 8.2)

66. The median family income of every suburb of the combined

suburban area, except East Hartford and Windsor Locks, has more than

doubled during that ten year period from 1980-1990 and the median

income of a Hartford family increased 42% during that period.

(Defs’ Exs. 8.1 & 8.2)

67. The percentage of students in Hartford who live in homes

where a language other than English is spoken is higher than in any

surrounding community. (Figure 34 (as modified, see Natriello, p.

177), Pls’ Ex. 163 at 154)

68. The Hartford Public Schools serve a greater proportion of

students from backgrounds that put them "at risk" of lower

educational achievement than the identified suburban towns and, as

a result, the Hartford Public Schools have a comparatively larger

burden to bear in addressing the needs of "at risk" students.

69. "At risk" children have the capacity to learn and "at

risk" children may impose some special challenges to whichever

school system is responsible for providing these children with an

education.

70. Some Of the indicia of "at risk” students include (i)

whether a child's family receives benefits under the Federal Aid to

Families with Dependent Children program, (a measure closely

correlated with family poverty); (ii) whether a child has limited

english proficiency (hereafter "LEP"); or (iii) whether a child is

from a single-parent family. (Defs’ Revised Answer 137)

71. There are some differences between Hartford Public School

students taken as a whole and suburban students as a whole in some

of the surrounding communities in terms of the number who drop out

before graduation, who enter four year colleges and other programs

of higher education, and the number of others who obtain full-time

employment within nine months of graduation.

72. The drop out rate for Hartford schools is greater than for

Connecticut public schools in general. (Pls’ Ex. 163 at 142-145)

73. In 1988, fewer than 30% of Hartford students attended four

year colleges in the October following graduation while over 52% of

students statewide did. For 1991, 31% of Hartford students did

while 51% of students statewide did. {Pls’' ‘Ex. 163 at 146, 147;

Natriello p. 172)

74. In 1988, statewide, 71.9% of students attended college

following graduation while 57% of Hartford students did so. (Pls’

Ex. 163 at 146)

75. The negative impact of poverty on student achievement is

acknowledged and controlled for by social-scientists in their

studies on student achievement. (Crain pp. 102-103, Vol. 35, p. 76)

76. Hartford schools serve a greater proportion of students

from backgrounds that put them "at risk" of lower educational

achievement than the identified suburban towns. (Defs’ Revised

Answer 35)

77. As a result, Hartford has a comparatively larger burden to

bear in addressing the needs of "at risk" children. (Defs’ Revised

Answer 35)

78. Social problems more common to students in Hartford than

to students in the suburbs, which have been shown to have a direct

negative impact on student development, are children with low

birthweight, children born to mothers on drugs, children born to

teenage mothers, children living in poverty, children from single

parent households, children with parents with limited formal

‘education, children living in substandard housing, children from

homes where little English is spoken, children exposed to crime and

children without an employed parent. (Pls’ Ex. #163, Table 2, p. 28)

79. When Hartford children who are afflicted by poverty enter

kindergarten, many of them are already delayed one and one-half to

two years in educational development. (LaFontaine p. 132; Cloud p.

86; Montanez-Pitre pp. 11, 41; Negron p. 81)

80. Socio-economic status (SES) encompasses many factors

relating to a student’s background and family influences that affect

a child’s orientation toward and skill in learning. (Armor I pp.

138-140; Armor II pp. 11-12)

81. The gap between the SES of children who live in Hartford

and the SES of children who live in the 21 suburbs has been

increasing, (Natriello, pp. 114-116; Defs’ Ex. 8.1,'8.2)

82. By 1909, all but fifteen school districts in the state

were consolidated at the town level so that school district

boundaries except for the fifteen districts were contiguous with

town boundary lines. (Collier pp. 28, 39, 66)

83. The consolidation of school boundaries in 1909 had nothing

to do with the race of Connecticut students. (Collier, p. 66)

84. With the exception of regional school districts which have

been created by the voluntary action of towns pursuant to Chapter

164 of the General Statutes or predecessor statutes, and the fifteen

school districts mentioned above, no school district boundary has

been materially changed since 1909. (Aff. of Gerald Tirozzi

attached to Defs’ Motion for Summary Judgment ("Tirozzi Affidavit"),

1 4)

85. Since 1909, public school children have been assigned to

particular school districts on the basis of their residence.

(Tirozzi Affidavit, YY 5; Collier, p.. 22, 28, 32)

86. By 1941, the public school districts boundaries for

Hartford students had become by law co-terminous with the Hartford

town boundaries. (Collier, p. 29)

87. By 1951, all public school districts boundaries except for

regional districts in the state were co-terminous with town

boundaries. (Collier, p. 29)

88. No child has been intentionally assigned to a public

school or to a public school district on the basis of race, national

origin or socioeconomic status or status as an "at risk" student

99. In 1969, the General Assembly passed a Racial Imbalance

Law, requiring racial balance within, but not between, school

districts. Conn. Gen. Stat. §10-226a et seq. The General

Assembly authorized the State Department of Education to promulgate

implementing regulations. Conn. Gen. Stat. §10-226e. The General

Assembly approved regulations to implement the statute in 1980.

100. The number of children participating in Project Concern

has declined over time. In 1969, the Superintendent of Schools in

Hartford called for an expansion of Project Concern. (Defs’ Rev.

Answer 157)

101. At the direction of the General Assembly, Connecticut has

developed a statewide testing program, the Connecticut Mastery Test

("CMT"), and a statewide system of school evaluation, the Strategic

School Profiles ("SSP"). (Rindone pp. 80-81; Nearine p. 65; Conn.

Gen. Stat. §10-14n and §10-220(c))

102. The CMT was first administered in the fall of 1985. (Pls’

Ex. ..290)

103. The State Board of Education has stated that the goals of

the CMT are:

a. earlier identification of students needing remedial

education;

b. continuous monitoring of students in grades 4, 6, and

8;

C. testing of a more comprehensive range of academic

skills;

d. higher expectations and standards for student

achievement;

e. more useful achievement data about students, schools,

and districts;

f. improved assessment of suitable equal educational

opportunities. (Defs’' Ex. 12.13)

104. The CMT measures mathematics, reading and writing skills

in the 4th, 6th, and 8th grades. (Pls’ Ex. 290-309)

105. The CMT is one measure of student achievement in

Connecticut.

106. Standardized test scores alone do not reflect the quality

of an education program. (Natriello pp. 11, 189; LaFontaine p. 140;

Nearine p. 16; Negron pp. 15-16; Shea p. 140)

107. The differences in the performance between two groups of

students cannot solely be attributed to differences in the quality

of education provided to those groups without taking in account

- 30 a

except for very brief period in 1869 when the City of Hartford

attempted to assign students to schools on the basis of race, which

practice was halted by the General Assembly. (Collier p. 48; Tirozzi

Affidavit, )

89. There was no significant Latino population of primarily

Puerto Rican ancestry in Connecticut until the late 1960's. (Morales

pp. 29-30)

90. At the start of this century, the African-American

population was approximately 3% of the state’s total population and

remained at or below that level for the first half of this century.

(Steahr pp. 78-79)

91. By 1940, African-Americans had declined to 1.2% of the

state’s population. (Collier p. 41; Steahr pp. 78-80.)

92. Each town in the 21 town area surrounding Hartford, as

described by the plaintiffs in their amended complaint has

experienced an increase in non-white population since 1980. (Steahr

P. 29)

93. Since 1980, total student enrollment in the combined 21

suburban school districts has declined. (Defs’ Ex. 2.4)

94. The greatest percentage increase in Hartford's African-

American population was between 1950-1960. (Steahr p. 79)

95. Since 1970, the African-American population has been

increasing in many towns around Hartford, particularly in

Bloomfield, Manchester, Windsor and West Hartford. (Steahr Pp. 38)

96. In Hartford, there has been a numerical increase in the

African-American population, which is due to an increase in births

over deaths and not to in-migration. (Steahr p. 61)

97. State officials have, for some time, been aware of a trend

by which the percentage of Latino students in the Hartford public

schools has been increasing while the percentage of white and

African American students has been decreasing. (Defs’ Revised

Answer 150)

98. According to a 1965 study commissioned by the Hartford

Board of Education and the Hartford City Council and prepared by

consultants affiliated with the Harvard School of Education (the

"Harvard Study"), the rapid increase of non-white student population

in Hartford in the 1950's and early 1960's would not continue.

. (Defs’ Ex. 13.2, p. 2; Defs’ Rev. Answer 152)

2:12

differences in performance that are the product of differences in

the socioeconomic status of the students in the two groups. (Defs’

Ex. 10.1; Flynmnipp. 151-153, 183; Armor p. 21; Crain pp. 78-79;

Natriello pp. 22-23)

108. In addition to poverty, among other reasons, Hartford

students may score lower on the CMT than the state average (1)

because many Hartford students move among Hartford schools and/or

move in and out of the Hartford school district, and (2) because

many Hartford students are still learning the English language.

(Shea p. 140; Nearine pp. 68-69; Negron pp. 15-16)

109. Hartford Public Schools students as a whole do not

perform as well on the Connecticut Mastery Test ("CMT) as do the

students as a whole in some surrounding communities. (Defs’ Rev.

Answer 913)

110. The following figures concerning reading scores on the

1988 CMT are admitted to the extent that they are identical to

figures found in Pls’ Ex. 297, 298 and 299:

% Below 4th Gr. % Below 6th Gr. Below 8th Gr.

Remedial Bnchmk Remedial Bnchmk Remedial Bnchmk

Hartford 70 59 57

*kkkkkkhkkkk

Avon 9 6 3

Bloomfield 25 24 16

Canton 8 10 2

East Granby 12 4 9

East Hartford 38 30 36

East Windsor 17 10 15

Ellington 25 14 13

Farmington 12 3 10

Glastonbury 15 i3 11

Granby 19 14 17

Manchester 22 15 17

Newington 8 15 12

Rocky Hill 13 10 24

Simsbury 9 5 3

South Windsor 9 13 16

Suffield 20 10 15

Vernon 15 18 20

West Hartford 19 15 11

Wethersfield 18 12 14

Windsor 26 17 23

Windsor Locks 25 16 17

3, Sy by IM

111. The following figures concerning mathematics scores on

the 1988 CMT are admitted to the extent that they are identical as

figures found in Pls’ Ex. 297, 298 and 299:

% Below 4th Gr. % Below 6th Gr. % Below 8th Gr.

Remedial Bnchmk Remedial Bnchmk Remedial Bnchmk

Hartford 41 42 57

Avon 4 2 3

Bloomfield 6 21 18

Canton 3 8 5

East Granby 10 7 6

East Hartford 14 19 19

East Windsor 2 9 19

Ellington 10 8 4

Farmington 3 5 3

Glastonbury 6 8 2

Granby 3 12 11

Manchester 8 15 1

Newington 3 6 7?

Rocky Hill 5 4 14

Simsbury 5 5 3

South Windsor 8 10 8

Suffield 11 13 8

Vernon 8 9 12

West Hartford 8 9 7

Wethersfield 6 8 6

Windsor 12 13 26

Windsor Locks 2 7 14

112. Public school students in Bloomfield, a middle class

town with an 85.5% minority population, produced CMT test scores

that were higher than several other suburban towns. (Crain pp. 90-

91; Pls’ Ex. 297-299)

113. Levels of performance on the Mastery Test are accurately

described in Plaintiffs’ Exhibits 290-308. (Defs’ Revised Answer

141)

114. Defendants are not satisfied with the performance of

Hartford school children as a whole or of any children who perform

below the mastery level. (Defs’ Revised Answer 145)

115. Hartford fourth graders mastered an average of 16.5

objectives on the CMT math test while fourth graders in the 21

E

E

—

--14 =

surrounding communities averaged from 21.3 to 23.3. (Figure 59,

Pls’ Bx. 163 at 198)2

lls. Hartford sixth graders mastered an average of 17.1

objectives on the CMT math test while sixth graders in the 21

surrounding communities averaged from 23.7 to 30.7. (Figure 60,

Pls’ Bx. 183 at 199)

117, Hartford eighth graders mastered an average of 17.8

objectives on the CMT math test while eighth graders in the 21

surrounding communities averaged from 24.2 to 32.5. (Figure 61,

Pls’ Ex, 163 at 201)

118. Hartford fourth graders mastered an average of 3.3

objectives on the CMT language arts test while fourth graders in the

21 surrounding communities averaged from 5.9 to 7.7. (Figure 62,

Pls’ Bx. 163 at 203)

119. Hartford sixth graders mastered an average of 4.8

objectives on the CMT language arts test while sixth graders in the

21 surrounding communities averaged from 7.5 to 9.8. (Figure 63,

Pls’ Ex. 163 at. 204)

120. Hartford eighth graders mastered an average of 5.3

objectives on the CMT language arts test while eighth graders in the

21 surrounding communities averaged from 7.6 to 9.8. (Figure 64,

Pls’ Bx. 163 at 206)

121. Hartford fourth graders mastered an average of 37

objectives on the CMT DRP test while fourth graders in the 21

surrounding communities averaged from 46 to 56. (Pigure 65, Pls’

Bx. 163 at. 207)

122. Hartford sixth graders mastered an average of 46

objectives on the CMT DRP test while sixth graders in the 21

surrounding communities averaged from 55 to 67. (Figure 66, Pls’

Ex. 163 at 208)

123. Hartford eighth graders mastered an average of 53

objectives on the CMT DRP test while eighth graders in the 21

surrounding communities averaged from 60 to 74. (Figure 67, Pls’

Bx. 163 at 209)

124. Hartford fourth graders mastered an average of 4.1

objectives on the CMT holistic writing test while fourth graders in

2 Stipulations numbers 115-26 are based on 1991-92 mastery

test scores. Stipulations numbers 127-32 are based on 1992-93

mastery test data.

gy

the 21 surrounding communities averaged from 4.7 to 5.5. (Figure

68, Pls’ Ex. 163 at 211)

125. Hartford sixth graders mastered an average of 3.9

objectives on the CMT holistic writing test while sixth graders in

the 21 surrounding communities averaged from 4.5 to 6.2. (Figure

69, Pls’ Bx. 163 at 212)

126. Hartford eighth graders mastered an average of 5.1

objectives on the CMT holistic writing test while eighth graders in

the 21 surrounding communities averaged from 5.1 to 6.7. (Figure

70, Pls! ‘Ex. 163 at 213)

127. Hartford fourth graders mastered 15.8 math objectives

while children in surrounding communities mastered from 20.9 to

23.5. (Pls’ Reply Brief Ex. G)

128. Hartford sixth graders mastered 16.7 math objectives

while children in surrounding communities mastered from 23.7 to

30.4. (Pls’ Reply Brief Ex. H)

129. Hartford eighth graders mastered 18.1 math objectives

while children from surrounding communities mastered from 20.6 to

31.6. (Pls’' Reply Brief Ex. I)

130. Hartford fourth graders mastered 3.1 language arts

objectives while children in surrounding communities mastered from

5.8. t0 72.7. (Pls’ Reply Brief Bx. J)

131. Hartford sixth graders mastered 4.7 language arts

objectives while children in surrounding communities mastered from

7.3 t0. 9.7. (Pls' Reply Brief Ex. XK)

132. Hartford eighth graders mastered 5.4 language arts

objectives while children from surrounding communities mastered from

5.6 0 8.7. (Pls' Reply Brief Ex. IL)

133. From 1987 to 1991, Hartford fourth graders mastered from

15.9 to 16.5 of the 25 mathematics objectives while the statewide

average was from 20.4 to 21.2 objectives. (Figure 1, Pls’ Ex. 163

at 85)

134. From 1987 to 1991, Hartford sixth graders mastered from

16.9 to 18.3 of the 325 mathematics objectives while the statewide

average was from 23.7 to 24.7 objectives. (Figure 2, Pls’ Ex. 163

at 87)

135. From 1987 to 1991, Hartford eighth graders mastered from

17.6 to 19.3 of the 35 mathematics objectives while the statewide

average was from 25 to 25.8. (Figure 3, Pls’ Ex. 163 at 89)

136. From 1987 to 1991, Hartford fourth graders mastered from

3.2 to 3.5 of the 9 language arts objectives, while the statewide

average was from 6.2 to 6.3. (Figure 7, Pls’ Ex. 163 at 97)

137. From 1987 to 1991, Hartford sixth graders mastered from

4.4 to 5.3 of the 11 language arts objectives, while the statewide

average was from 7.4 to 8.1. (Figure 8, Pls’ Ex. 163 at 99)

138. From 1987 to 1991, Hartford eighth graders mastered from

4.7 to 5.4 of the 11 language arts objectives while the statewide

average was from 7.7 to 8.4. (Pigure 9, Pls’ Ex. 163 at 101)

139. In 1991, Hartford students took the SAT test at a lower

rate than students elsewhere in the state -- 56.7% of Hartford

students, compared to a statewide average of 71.4% (Pls’ Ex. 163 at

141).

140. Hartford students score the lowest on the SAT when

compared to the performance of students in the surrounding

districts. (FPigures 79 and 80, Pls’ Ex. 183 at 225-226; Natriello

1X p. 32)

141. In 1991, the average math score of Hartford graduates on

the SAT was 354 out of 800 and the average score of graduates in the

next lowest scoring district, Bloomfield, was 411; (Pls’ Ex. 163 at

225, Fig. 79); in the verbal section, the average score of Hartford

graduates was 314 out of 800 and the average score of graduates in

the next lowest scoring district, East Hartford was 390.

142. The purpose and effect of the state’s principal formula

for distributing state aid to local school districts (the Education

Cost Sharing formula ("ECS") embodied in Conn. Gen. Stat. §§10-

262f, 10-262g, 10-262h) is to provide the most state aid to the

neediest school districts. (Brewer pp. 37, 85, 157-162; Defs’ Ex.

7.1, pp. 716-78; 7.23, p. 83A; 7.18, 7.19;.7.20)

143. Under the ECS formula, the Hartford public schools

received for the 1990-91 school year $3,497-per pupil in state

funds; the average per pupil grant to the 21 suburban school

districts was only $1,392 in state funds. (Brewer p. 85; Defs’ Ex.

7.21, pp. 83-833)

144. Under the ECS formula, the Hartford public schools

received for the 1991-92 school year $3,804 per pupil in state

funds; the average per pupil grant to the 21 suburban school

districts was only $1,321 in state funds. (Brewer p. 85; Defs’ Ex.

7.21, pp. 83-83A)

145. The increase in state aid to Hartford under the ECS

formula from 1990-91 to 1991-92 was $307 per pupil; the decrease in

the average ECS formula grant to the 21 suburban school districts

from 1990-91 to 1991-92 was $71 per pupil. (Brewer p. 85; Defs’ Ex.

7.21, pp. 83-834)

146. In terms of total state aid for the 1990-91 school year

(the sum of all state education aid including the ECS formula aid),

Hartford received $4,514 per pupil; the average amount of total

state aid to the 21 suburban school districts was $1,878 per pupil.

(Brewer p. 37; Defs’' Ex. 7.21, pp. 11-113)

147. In terms of total state aid for the 1991-92 school year,

Hartford received $4,915 per pupil; the average amount of total

state aid to the 21 suburban school districts was $1,758 per pupil.

(Brewer p.37; Defs! Ex. 7.21, p. 11-113)

148. The increase in Hartford's total state aid from 1990-91

to 1991-92 was $401 per pupil; the decrease in average total state

aid to the 21 suburban school districts was $120 per pupil (Brewer

Pp. 37; Defs’! Ex." 7.21, pp. 11-11iA)

143. Hartford received 2.4 times as much total state aid per

pupil as the 21 suburban school districts in 1990-91 and 2.8 times

48 much total state aid per pupil in 1991-92. (Defs’ Ex. 7.1, p.l}1;

Defs’ Fx. 7.21, Dp. 113)

150. In 1990-91, the Hartford school district received 57.6%

of its total funding from state aid and 60.49% thereof in 1991-92.

(Brewer p. 37; Defs’ Ex. 7.1, pp. 11-11A)

151. In 1990-91, the 21 suburban school districts received an

average of 25.8% of their total funding from state aid and 23.99%

thereof in 1991-92. (Brewer p. 37; Defs’ Bx. 7.1, pp. 11-113)

152. In 1990-91, overall per pupil expenditure in Hartford

were $7,837 and $7,282 per pupil in the 21 combined suburban school

districts. (Defs!' Ex. 7.1, pp. 3a, 11)

153. In 1991-92, the overall per pupil expenditure in Hartford

was $8,126 compared to an average of $7,331 per pupil in the 21

combined suburbs. (Defs’ Ex. 7.1, pp. 33, 11)

154. Under the category of "net current expenditures per need

student," a calculation in which the Hartford public school student

count is increased by an artificial multiplier of one-quarter

student for each Hartford public school student on Aid to Families

with Dependent Children (AFDC) and by one-quarter student for each

Hartford public school student who in the preceding school year

tested below the remedial standard on the CMT, i.e., each AFDC

student and CMT remedial student is counted as 1.25 students and

each student who is both on AFDC and a CMT remedial student is

18 -

counted as 1.5 students, Hartford’s per pupil spending for the 1990-

"1991 school year was fifteenth among the school districts in the

twenty-two town area. (Natriello, Vol. 93-94; PX 163, pp. 158-162)

155. During the 1390-91 school year, the total professional

staff per 1,000 students was 89.4 in Hartford and 88.8 in the

combined 21 suburban school districts. (Defs’ Ex. 8.5)

156. During the 1991-92 school year, the total professional

staff per 1,000 students in Hartford was 86.5 and 85.1 in the 21

combined suburb school districts. (Defs’ Ex. 8.5)

157. During the 1990-91 school year, Hartford had 77 classroom

teachers per 1,000 students and the 21 combined suburban school

districts had 75.9. (Defs’ Ex. 8.8)

158. The Hartford public schools have high quality classroom

teachers and administrators. (Pls’ Ex. 163 (table 4); Keaveny p. 15;

LaFontaine p. 131; Wilson pp. 9, 28-29; Negron p. 7; Pitocco p. 70;

Natriello p. 35)

159. Hartford teachers are dedicated to their work. (Haig pp.

113-114; Neumann-Johnson p. 18)

160. In 1991, 94% of Hartford administrators had at least

thirty credits of education beyond their masters degrees. (Keaveny

p. 14)

161. Hartford teachers have been specially trained in

educational strategies designed to be effective with African-

American, Latino, inner city and poor children. (Haig p. 94;

LaFontaine p. 132; Wilson p. 10)

162. Hartford's elementary schools have a curriculum that is

standardized from school to school designed to ameliorate the

effects of family mobility, which affects Hartford children to a

much greater extent than suburban children. (LaFontaine p. 162)

163. Hartford schools have some special programs for enhancing

the education of poor and urban children. (Haig p. 63; LaFontaine

pp. 134-135)

164. Hartford has an all-day kindergarten program in some of

its elementary schools for children who may be at risk of poor

educational performance. (Calvert pp. 10-13; Negron p. 68; Montanez-

Pitre pp. 34, 48; Cloud pp. 79, 88, 113)

165. Hartford has a school breakfast program in each of its

elementary schools. (Senteio p. 50; Negron p. 66; Montanez-Pitre P-.

4-2; Morris p. 158; Neumann-Johnson p. 24)

166. Hartford offers eligible needy students in all its

schools a free and reduced-price lunch program. (Senteio p. 22)

167. Hartford's school breakfast and school lunch programs are

paid for entirely by state and federal funds. (Senteio p. 22)

168. The Hartford school district has several special programs

such as the Classical Magnet program, which the first named

plaintiff attends, and the West Indian Student Reception Center at

Weaver High School. (E. Sheff p. 194; Pitocco pp. 88-89)

169. Hartford’s school buildings do not meet some requirements

regarding handicapped accessibility, but no buildings are in

violation of health, safety, or fire codes. (Senteio p. 44)

170. In 1992, Hartford voters approved the issuance of

$204,000,000 in bonds for school building expansion and improvement.

{(Senteio p. 37)

171. Under 1991-92 state reimbursement rates, the state will

reimburse Hartford for more than 70% of the cost of its school

building expansion and improvement project. (Defs’ Ex. 7.21, p. 3A)

172. From 1980 to 1992, Hartford spent approximately $2,000

less per pupil on (a) pupil and instructional services, (b)

textbooks and instructional supplies, (c) library books and

periodicals, and (d) equipment and plant operations than the state

average for these items. (Defs’ Ex. 7.9; Brewer p. 142)

173. From 1980 to 1992, the Hartford school district paid its

employees $2,361 more per pupil in employee benefits than the state

average. (Defs’ Ex. 7.9; Brewer p. 143)

174. From 1988-91, Hartford spent $240 more per pupil than New

Haven and $300 more per pupil than Bridgeport on employee fringe

benefits. (Brewer p. 143)

175. When demographic conditions continued to change in the

1980s, the General Assembly passed diversity legislation such as the

Interdistrict Cooperative Grant Program, Conn. Gen. Stat. §10-

74d, and several special acts designed to promote diversity by

funding interdistrict magnet school programs. (Defs’ Ex. 3.2 - 3.7,

3.9; 7.1, pp. 36-40; 7.2, p. 404)

176. The Interdistrict Cooperative Grant Program began in 1988

with a $399,000 appropriation, which by 1992 had increased to

$2,500,000. (Williams pp. 76-77)

177. The state intervened to save Project Concern, a program

in which minority Hartford children attend suburban schools, when

“50 -

the Hartford Board of Education voted to withdraw from the program

‘in early 1980s. (LaFontaine pp.,124-125; Calvert p. 128)

178. During the 1980s, the State Department of Education was

reorganized to concentrate on the needs of urban school children and

on promoting diversity in the public schools. Defs’ Ex. 3.1, 3.8)

179. The State Board of Education administers a grant program

pursuant to Conn. Gen. Stat. §10-17g to assist school districts

including Hartford which are required by law to provide a bilingual

education program. (Defs’ Ex. 7.1, pp. 28-35; 7.21, p. 35a)

180. The State Board of Education administers under Conn.

Gen. Stat. §§10-266p - 10-266r a Priority School District program

for towns in the state with the eight largest populations, including

Hartford, to improve student achievement and enhance educational

opportunities. (Defs’ Ex, 7.1, pp. 154-160; 7.21, p. 1603)

131. The General Assembly provides substantial financial

support to schools throughout the State to finance school

operations. See §§10-262f, et seq.

182. The General Assembly provides reimbursement to towns for

student transportation expenses. See §10-273a.

183. The State Board of Education prepares courses of study

and curricula for the schools, develops evaluation and assessment

programs, and conducts annual assessments of public schools. See

§10-4.

184. The State Board of Education prepares a comprehensive

plan for elementary, secondary, vocational, and adult education

every five years. See id.

185. The General Assembly has established the ages at which

school attendance is mandatory throughout the State. See §10-184.

186. The General Assembly has determined the minimum number of

school days that public schools must be in session each year, and

has given the State Board of Education the authority to authorize

exceptions to this requirement. See §10-15.

187. The General Assembly has set the minimum number of hours

of actual school work per school day. See §10-16.

188. The General Assembly has promulgated a list of holidays

and special days that must be suitably observed in the public

schools. See §10-29a.

WELT, J

189. The General Assembly has promulgated a list of courses

‘that must be part of the program of instruction in all public

schools, see §10-16b

190. The General Assembly has directed the State Board of

Education to make available curriculum materials to assist local

schools in providing course offerings in these areas. See id.

191. The General Assembly has imposed minimum graduation

requirements on high schools throughout the State, see §10-221la.

192. The General Assembly directed the State Board of

Education to exercise supervisory authority over textbooks selected

by local boards of education for use in their public schools. See

§10-221.

193. The General Assembly has required that all public schools

teach students at every grade level about the effects of alcohol,

tobacco, and drugs, see §10-19.

194. The General Assembly has directed local boards of

education to provide students and teachers who wish to do so with an

opportunity for silent meditation at the start of every school day.

See §10-16a.

155. The General Assembly has directed the State Board of

Education to set minimum teacher standards, and local board of

education to impose additional such standards. See §10-145a.

196. The General Assembly has directed the State Board of

Education to administer a system of testing prospective teachers

before they are certified by the State. See §10-145f.

197. Certification by the State Board of Education is a

condition of employment for all teachers in the Connecticut public

school system. See §10-145.

198. All school business administrators must also be certified

by the State Board of Education. See §10-145d.

199. The General Assembly has directed the State Board of

Education to specify qualifications for intramural and

interscholastic coaches. See §10-149.

200. The General Assembly has promulgated laws governing

teacher tenure, see §10-151, and teacher unionization, see §10-153a.

201. The General Assembly has created a statewide teachers’

retirement program. See §10-183b, et seq.

- 23.

202. The General Assembly has directed the State Board of

‘Education to supervise and administer a system of proficiency

examinations for students throughout the State. See §10-14n.

203. Mastery examinations annually test all students enrolled

in public schools in the fourth, sixth, eighth and tenth grades.

See id.

204. The General Assembly promulgated procedures setting forth

the process by which local and regional boards of education may

discipline and expel public school students under their jurisdic-

tions. See §10-233a et seq.

205. Except as provided in §§10-17a and 10-17f, the General

Assembly has mandated that English must be the medium of instruction

and administration in all public schools in the State. See §10-17.

206. The General Assembly has required local school districts

to classify all students according to their dominant language, and

to meet the language needs of bilingual students. See §10-17f.

207. The General Assembly has required each local and regional

board of education to implement a program of bilingual education in

each school in its district with 20 or more students which dominant

language is other than English. See id.

208. The General Assembly has required all local and regional

school boards to file strategic school profile reports on all

schools under their jurisdiction. (§10-220(c).

209. Improved integration of children by race, ethnicity and

economic status is likely to have positive social benefits. (Defs’

Revised Answer 149)

210. The defendants have recognized that society benefits from

racial, ethnic, and economic integration and that racial, ethnic,

and economic isolation has some harmful effects.

211. Integration in the schools is not likely to have a

negative effect on the students in those schools. (Defs’ Revised

Answer 149)

212. Poor and minority children have the potential to become

well-educated. (Defs’ Revised Answer 13)

213. The Defendants have announced that they would pursue a

"voluntary and incremental approach toward the problem of de

facto socioeconomic, racial and ethnic isolation in urban schools,

including the Hartford Public Schools.

- 23

Respectfully Submitted,

| oN hoa Stora

Martha Stone #61506

Connecticut Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

32 Grand Street

Hartford, CT 06106

(203) 247-9823

ar of J

Wesley W[,/ = 738478

Moller, seus & Shields, P.C.

90 Gillett Street

Hartford, CT 06105

(203)-522-8338

BY:

82d Brittaim™%103 153

University of Connecticut

oe School of Law

65 Elizabeth Street

Hartford, CT 06105

(203) 241-4664

BY: Pho Jege (eps

Philip D. Tegeler #102537

Connecticut Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

32 Grand Street

Bartford, CT 06106

(203) 247-9823

- 24 a

Theodore Shaw

Dennis Parker

Marianne Lado

NAACP Legal Defense Fund

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Sandra Del Valle

Puerto Rican Legal Defense Fund

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

Christopher Hansen

American Civil Liberties Union

132 West 43rd Street

New York, NY 10036

(212) 944-9800

Wilfred Rodriguez #302827

Hispanic Advocacy Project ~

Neighborhood Legal Services

1229 Albany Avenue

Hartford, CT 06112

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

FOR THE DEFENDANTS

RICHARD BLUMENTHAL

ATTORNEY GENERAL

BY:

Befnard Mc@ovérn

Martha Wat/ts/Prestley

Assistd Attorney General

MacKenzie Hall

110 Sherman Street

Hartford, CT 06105

(203) 566-7173