Bullock v. Mississippi Court Opinion

Working File

August 6, 1981

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Bullock v. Mississippi Court Opinion, 1981. 2390080d-f092-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0c7595c8-eb3c-4e75-8a48-660a0ba8f930/bullock-v-mississippi-court-opinion. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

ML

WtWl+Lths

Miss. 601

' 2. Indictment and Information e=?1.4(5)

In<lictment for capital murder while

committing the crime of robbery, which al-

legedly did not set forth the essential ele-

ments of the crime of robbery and did not

refer to the proper statute to charge the

crimc of capital murder, was sufficient to

give defendant fair notice of the crime

charged in clear and intelligible language

and, therefore, the trial court correctly

overruled defendant's demurrer. Code

1972, $ 97-3-19(2)(e).

3. Criminal Law e=76411; a

Circumstantial evidence instructions /

should lle given only in a purely circumstan- |

tial evidence case. -'t

4. Criminal Law e314117;

Where there was direct evidence conl

sisting of statements made by defendant ln rtL

anrl of his own testimony adduced at trial \

on guilt phase of case, defendant was not

)

entitled to circumstantial evidence instrue.J

tions.

5. Criminal l,aw e73411;

Instruction known as "two-theory inl

struction" should not be given except in \

purely circumstantial evidence cases. )

6. Criminal Law e753.2(8)

In passing on a requested peremptory

instruction or motion for directed verdict, in

a criminal case, all evidence most favorable

to the state together with reasonable infer-

ences therefrom is considered true and evi-

dence favorable to defendant is disregard-

ed.

7. Criminal Law e753.2(5)

If evidence favorable to the state and

reasonable inferences therefrom will sup-

port a guilty verdict, the request for a

peremptory instruction must be denied as

well as any motion for directed verdict.

8. llomicide F268

In vicw of overwhclming evirlence that

defendant was present and aided and assist-

ed in assaulting and killing victim and in

removing and discarding victim's wallet and

' {:.,i

i

I

V',tr

BULLOCK v. STATE

Clte as, Mls3., 391 So.2d 601

Crawford BULLOCK, Jr.

v.

STATE of Mississippi.

No. 51937.

Supreme Court of Mississippi.

Aug. 6, 1980.

Rehcaring Denied Jan. 14, 1981.

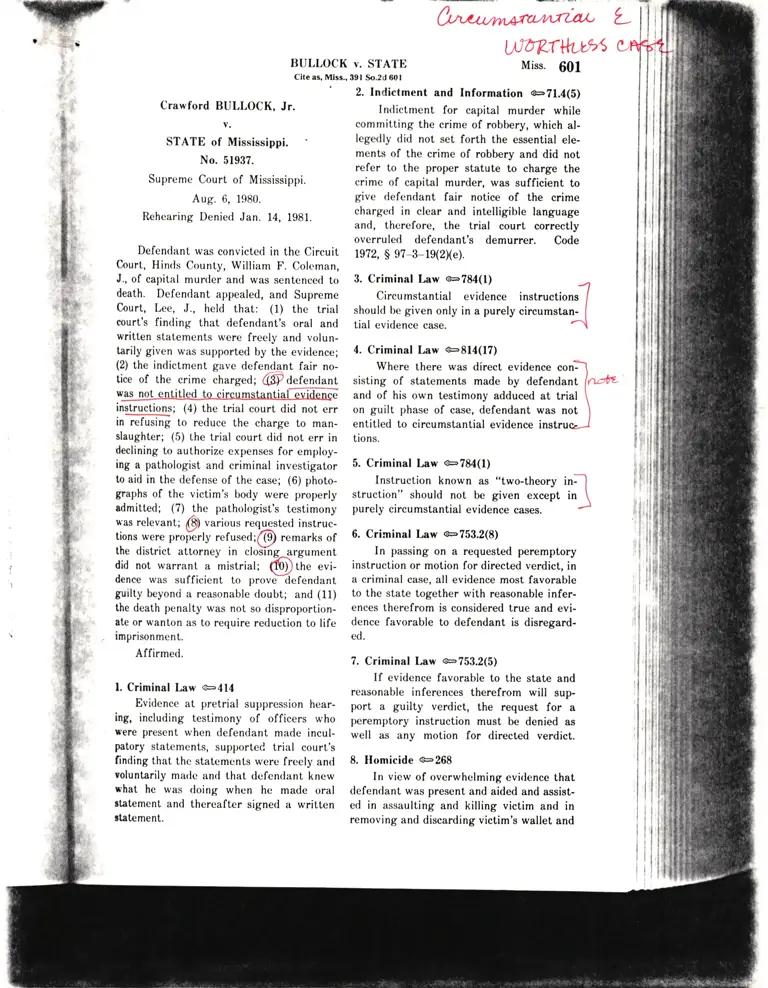

Defendant was convicted in the Circuit

Court, Hinrls County, William F. Coleman,

J., of capital murder and was sentenced t<l

death. Defen<lant appealed, and Supreme

Court, Lee, J., held that: (1) the trial

court's finding that defendant's oral and

written statements were freely and volun-

tarily given was supported by the evidence;

(2) the indictment gave defendgnt fair no-

tice of the crime charged; (!pdefendant

was not entitled to c

instructions; (4) the trial court did not err

inErusin! to reduce the charge to man-

slaughter; (5) the trial court did not err in

declining to authorize expenses for employ-

ing a pathologist and criminal investigator

to aid in the defense of the case; (6) photo-

graphs of the victim's body were properly

admitted; (7) the pathologist's testimony

uas relevant; ($) various requested instruc-

tions were profierly refused;(O remarks of

the district attorney in cloii-ng^argument

did not warrant a mistrial; (b;)ttre evi-

dence was suff icient to prove-defendant

guilty beyond a reasonable doubt; and (11)

the death penalty was not so disproportion-

ate or wanton as to require reduction to life

imprisonment.

Affirmed.

l. Criminal Law e414

Evidence at pretrial suppression hear-

ing, including testimony of officers who

rere prescnt when defendant made incul-

patory statements, supported trial court's

finding that thc statemenl.s were frcely and

roluntarily marle anrl that defcnrlant kncw

rhat he was doing when hc made oral

rtatement and thereafter signed a written

rtatement.

t.

l,

h

,

l

ii

602 Miss. 39I SOUTHERN REPORTER,2d SERIES

personal effects and in taking victim's auto-

mobile, trial court properly refused to grant

a peremptory instruction of not guilty.

9. Indictment and Information @-159(2)

Trial court committed no error when it

declined to reduce charge of capital murder

while committing crime of robbery to man-

slaughter. Code 1972, g 97-3-19(2)(e).

10. Criminal Law e.665(4)

Even if certain prosecution witnesses

violated the sequestration rule by discussing

their testimony with other witnesses prior

to trial, the court had discretion to admit

the witnesses' testimony where there was

no prejudice from doing so.

ll. Costs o-302.3, 302.4

In prosecution for murder while com-

mitting a robbery, the trial court did not

commit error when it refused to grant de-

fendant's motion for appointment of a crim-

inologist or criminal investigator and a psy-

chiatrist to assist in preparation of the de-

fense.

12. Criminal Law @438(6)

In prosecution for capital murder while

committing a robbery, trial court did not

abuse discretion when it admitted in evi-

dence black and white photographs of the

victim's body which depicted how the body

had been weighted with concrete blocks and

how a garden hose had been wound around

the body to hold the blocks so that the body

would submerge and which also corrobo-

rated pathologist's testimony concerning

the wounds on the body.

13. Homicide G=175

In prosecution for capital murder while

committing robbery, trial court properly ad-

mitted pathologist's testimony that the ex-

act cause of the victim's death was a frac-

ture of the skull and not drowning.

14. Homicide e 169(8)

In lrroscr:ution f<lr calriLal murrlcr whilt'

comnritting a rohhery, no crror aroso from

fact that trial c<lurt allowed three witnesses

to testify ahout conversations they had with

the victim the night he was killed.

15. Criminal Law @.867

Fact that witness made unresponsive

referenee to defendantls bad character did

not require a mistrial where the trial court

sustained a defense objection to the ques-

tion and answer, instructed the jury to dis-

regard the answer and determined by in-

quiry to the jury that they could disregard

the answer.

16. Larceny e-32(l)

Robbery c=17(5)

An indictment charging robbery or lar-

ceny of property is properly laid in the

party having possession, whether as owner,

bailee or agent.

17. Homicide @169(2)

Where it was undisputed that murder

victim was in possession of a certain auio-

mobile on night of homicide, it was not

error for trial court to permit a witness to

testify about the ownership of the automo,

bile the victim was driving.

18. Criminal Lsw @438(2)

In prosecution for capital murder while

committing a robbery, trial court did not

abuse discrction when it admitted a high

school photograph of the victim over an

objection that the photograph was irrele-

vant and inflammatory.

19. Homicide €-289

Capital murder instruction which cor-

rectly set forth the issues that had to be

decided by the jury before the accused

could be convicted was properly given, in

prosecution for capital murder while com-

mitting a robbery.

20. Criminal Law G,829(19)

In prosecution for capital murder while

committing a robbery, it was not error for

the trial court to refuse to give the "single

juror" instruction where the principle of the

instruction was covered in another instruc-

tion.

21. Criminnl l,aw e757rr1,

An instruction which amounted to an

improper eomment on the weight and worth

of the defendant's testimony was properly

refused.

22. L,

confl i

jury t

again

fore r

woulr'

find :

to ret

was

proscr

23. H

Ir

comn)

when

jury t

al dr

Const

24. H

I

the jr

woul,.

sente;

ju.y

woulr

if serr

fuse '

25. ('

\

evidt,

that

medi,

nosis

chosi,

torntr

defer,

possl,

ted l,

26. (

I

mitt(

er or'

stat('

"Not

do 1"

antl ,

I twr

and

him.

did n

of tl,i

,t,

e

!

!

-a-

,1

l't,

tr

fr

T:

,867

rs made unresponsive

rrt's bad character did

I where the trial court

,rbjection to the ques-

rrrcted the jury to dis-

n(l determined by in-

t they could disregard

,arging robbery or lar-

I,roperly laid in the

!on, whether as owner,

(2)

rtlisputed that murder

,ion of a certain auto-

homicide, it was not

t.o 1rcrmit a witness to

rership of the automo-

lriving.

,438(2)

,r capital murder while

y, trial court did not

'n it admitted a high

i the victim over an

hotograph was irrele-

r.Y.

instruction which cor-

issues that had to be

, before the accused

'irs properly given, in

;rl murder while com-

'ft29( l9)

r caJrital murder while

.. it was not error for

rse to give the "single

,'rr the principle of the

r,rl in another instruc-

751>tlz

hich amountctl to an

tlrc weight and worth

';timony was properly

22. Criminal Law F810

Where the instruction was in direct

conflict with an instruction which told the

jury to weigh the mitigating circumstance

against any aggravating circumstances be-

fore returning a verrlict, instruction which

u'ould have told the jury that it need not

finrl any mitigating circumstances in order

to return a sentence of life imprisonment

was properly refused, in capital murder

prosecution.

23. Homicide e-3ll

In prosecution for capital murder while

committing a robl)ery, no error occurre(l

when the trial court refuscd to instruct the

jury that the dccision to afforrl an in<livirlu-

al defcnrlant mercy does not violate the

C,onstitution.

24. Homicide o=3ll

Requested instruction to thc effect that

the jury was to presume that the defendant

would spend the rest of his life in prison if

s€ntenced to life imprisonment and that the

jury was to presume that the defendant

would receive lethal gas until he was dead

if sentenced to death was calculated to con-

fuse the jury and was improper.

25. Criminal Law e720(7)

Where defendant himself introduced in

evidence a hospital record which indicated

that he had been admitted to a certain

medical center for treatment and that diag-

nosis indicated that he suffered from psy-

chosis, it was fair comment for <listrict at-

torney to state in closing argument that

defendant's problem with psychosis was a

possible explanation for his having commit-

ted homicide.

26. Criminal Law 6720(8)

In prosecution for capital mur<ler com-

mitted during a robbery, it was not improp-

er or prejudicial for the district attorney to

sfate during closing argument to the jury

"Now, look, if you see a guy on the street,

do you walk up and whop him on the hearl

and drop boulrlcrs on him anrl hit him with

a two lly four tnrl thcn you ttkc his hillfokl

an<l you takc his car, but you rlirln't rob

him. Do you llclieve that?"; thc statement

did not mislead the jury as to the elements

of the crime of robbery.

BIILLOCK v. STATE

Clte as. Mlss.. 301 so.zd 601

Miss. 603

27. Criminal Law e713

There is wide latitude for attorneys

argue cases to jury,

28. Criminal Law e=720(l)

In view of testimony that it was impos-

sible to remove a latent fingerprint from

concrete and certain other materials intro-

duced in evidence, it was not improper for

the district attorney to indicate in closing

argument that fingerprints could not be

taken from all the evidence.

29. Criminal Lsw 6720(6)

Where the statement was incrimina-

ting and connected rlefendant with the

crime anrl where, during the trial of the

case, defcndant's own counsel referred to

the statemcnt as a "confession," it was not

ohjectionable for the district attorney to

refer to the statement which defendant

made to investigating officers as a "confes-

sion."

30. Criminal Law e649111

Where defendant was not restricted in

any manner in the presentation of his de-

fense and was not prejudiced by the trial

court's procedure, it was not error for trial

court to deny defendant's motion for a re-

cess until the following morning before pro-

ceeding to the sentencing phase of capital

murder trial.

31. Homicide @=250

State's evidence, including oral and

written confessions of defendant and his

testimony at trial, was amply sufficient to

prove beyond a reasonable doubt that de-

fendant was guilty of capital murder. Code

1972, S 97-3-19(2Xe).

32' criminal Law el2l3

The death penalty statute is not uncon-

stitutional. Code 1972, $S 99-19-101 et

soq., 99-19-105.

33. Criminal Law e59(5)

Any llerson who is present, aiding and

abetting anothcr in commission of a crime,

is equally guilty with the principal offend-

.ilr;

604 Miss. 39I SOUTIII'RN REPORTER, 2d SERIES

34. Criminal La* e1206(2)

Homicide c=354

In vie w of cvirlcncc conccrning circum-

stances of crimc, inrlxrsition of dcath penal-

ty was not so tlisprolxrrtionate, wanton or

frcakish as to rcrluirc that the scntencc be

rerluccd to life imprisonment. Code 19?2,

SS 99 l9-101 et scr1.99 l9-105.

Bell & Brantlcy, Don H. Evans, Robert J.

Brantley, Jr., Jackson, for appellant.

Bill Allain, Atty. Gen. by Marvin L.

White, Jr., Sp. Asst. Atty. Gen., Edward

Peters, Dist. Atty., Jackson, for appellee.

En Banc.

LEE, Justicc, for the Court:

Crawfor<l Bullock, Jr. was indicted at the

November 1978 Term of the Circuit Court,

First Jurlicial District, Hinds County, for

the capital murder of Mark Dickson, while

committing the crime of robbery against

Dickson. A bilurcated trial was held dur-

ing the May 1979 Term of said court, Hon-

orable William F. Coleman presiding, and

the jury returned a guilty verdict of capital

murtler at the conclusion of the first phase

of thr: trial. A scparate sentencing phase

was held following the guilty verdict, and,

after deliberation, the jury returned a ver-

dict imlrcsing the rlcath sentence as punish-

ment for the crimc. Bullock has appealed

hcre anrl has assigned and argucd twenty-

eieht (28) errors in the trial below.

On the evening of September 21, 1978,

Crawford Bullock, Jr. and Rickey Tucker

went to Town Creek Saloon, where they

rlrank alcoholic bcvcrages <luring the night.

Whcn Bullock and Tucker deciderl to lcave

in the early morning of September 22, Lhey

<liscovered that the person, with whom they

had ridden there, ha<l left them. Mark

Dickson was leaving the place and he of-

fcred to givc them a ri<le home in thc gray

Thunrlcrlrirrl :rutonr<llrilc hc was rlriving.

On thc wty hotne, Ilullock httl Dicksrln

stoll at a convenience store in order for him

to buy some bread. Dickson gave Bullock

thirty-five cents (35c) for that purpose, but

the m<lney was returnetl when it was found

the store had no bread.

Dickson drove on at his riders' instruc-

tions. Bullock asked him to stop the auto,

mobile in order that he could answer a call

of nature. Upon returning to the vehicle,

Bullock overheard an argument between

Tucker and Dickson and heard Tucker say,

"[)on't make me Jrull this gun," and he

heard Dickson say that he did not have any

money but that they could have the auto-

mobile. All three re-entered the vehicle,

the argument continued, and Dickson

stopped on Byrd Drive near a construction

site where blows were exchanged between

Tuckcr and Dickson. Tucker told appellant

to grab Dickson, which he did. Dickson

broke away and left the vehicle. Tucker

got out with a whiskey bottle, using it as a

club, and advanced toward Dickson who

fled with Tucker in pursuit. Tucker tack-

led Dickson; appellant caught up with

them and grabbed Dickson by the head.

Tucker struck Dickson on the head with the

whiskey bottle which also hit Bullock's

hand, broke and cut it. Tucker beat Dick-

son with his fists, knocked him to the

ground, kicked him in the head as he lay on

the ground and then repeatedly struck him

with a concrete block on the head which

resulted in his death. Appellant went

across the street to an automobile agency

an<l tried to start one of the vehicles on the

outside of the building to no avail.

Tucker suggested that they burn the

bo<ly and the car, but appellant told him

that he knew of a lake near Byram where

the body could be disposed of. Dickson's

body was loaded into the car, and they

<lrove to a car wash, where the blood was

washed away. Tucker removed Dickson's

wallet from the body, went through it,

found no money and disposed of it in a

garbage can. Appellant drove the vehicle

to his home, where they cleaned up, obtain-

c<l a garrlen hose and then drove to the lake

ncur Ilyram. I)ickson's outer clothing was

rcmoved, concrcte blocks were placed in his

T-shirt and sh<lrts, the garden hose was

wrapped around the body and the weights,

and Tucker pulled the body out into the

i:F

{(

',,1r::rit'

q]

f;'r:

t>?r4+

T.

rr+'t

t

.*

rl when it was found

t.

t his riders' instruc-

rirn to stop the auto-

, could answer a call

rning to the vehicle,

argument between

irl heard Tucker say,

t.his gun," and he

hc <lirl not have any

ould have the auto-

cntered the vehicle,

r ucd, and Dickson

' near a construction

' cxchanged between

i'ucker toltl appellant

h he did. Dickson

the vehicle. Tucker

bottle, using it as a

,rward Dickson who

rrsuit. Tucker tack-

rt caught up with

'ckson by the head.

,rn the head with the

also hit Bullock's

Tucker beat Dick-

nocketl him to the

he head as he lay on

'1rcatedly struck him

on the head which

r. Apllellant went

automobile agency

I the vehicles on the

to no avail-

irat they burn the

appellant told him

near Byram where

'oscd of. Dickson's

the car, and they

here the blood was

removed Dickson's

, went through it,

,lisposed of it in a

t rlrove the vehicle

cleaned up, obtain-

r,n drove to the lake

outcr clothing was

, rvore pluccrl in his

garrkln hosc was

ly and the weights,

body out into the

t

1

i

BULLOCK v. STATE

Cite as, Mlss..30l So.2d 60l

lake and submergcd it. Aplrcllant also nine (9) hours after his arrest and at the

went into the lake, felt of the body with his end of that period, he was questioned by

feet, making sure that it w:rs submergetl Detective Fondren and Officer Jordan

and stuck in the mud at the bottom of the about the homicide. Appellant executed a

lake. written waiver of his constitutional rights,

Appellant and Tucker returned to Jack- and afterwards, gave an oral statement to

son and to appellant's home, again cleane6 the officers setting out his involvement in

up, antl appellant took Tucker home, then the crime. The statement was reduced to

went to the Univcrsity Merlical Centcr writing and was signed by the appellant. A

where hc obtaincrl metlical attcntion for his pre-trial suppression hearing was conduct-

hand. The next day Tucker and he drove in ed, the officers present when the state-

the Dickson automobile to McComb for the ments were made testified that appellant

purpose of visiting appellant's grandfather. was advised of his constitutional rights pri-

Thcy failerl to find him and returned to or to making the statement, that he ac-

Jackson. Appellant retained possession of knowledged understanding them and exe-'

the automobile. cutcd a written waiver thereof. The oral

Miss. 605

.l

i

a

t

T

I

C

$t

l;

t

J

t.

i

During the early morning hours of sep- statement made to the officers was typed

tember ?s, 1978, "pp"tt"ni't,"il ; ffi up by Detective Fondren' was read by the

pain in his hand, and he returned to univer- appellant' and was then signed by him'

sity Medical Center, driving the Dickson Appellant denied that the statements

automobile, where he obtained prescriptions were freely and voluntarily made and con-

for his injury. On his way home from the tends that the officers withheld medical

hospital, he rvas stopped by officers of the treatment for his injured hand until he

Jackson Police Department, was arrested, gave the statements. The officers testified

and was taken to the police station. On that appellant did not complain of pain with

being stopped and asked about the automo- his hand until they had completed the inter-

bile he was driving, appellant responded rogation' They offered medical assistance

that he had borrowed the automobile from to him, but appellant insistred on getting

a friend. While Dickson was driving the through with the statement first, and that

vehicle on the night of his death, the regis- he then go to the doctor. The officers

tration tag was on the back seat of the car testified that appellant was alert and coher-

and when Bullock was stopped, it had been ent, and that he was not under the influ-

placed on the tag mount outside the car. ence of medication or pain. After the offi-

At the police station, appellant made in- cers received the statements' appellant was

culpatory oral and *.iir"r- .t"i;;;;;- taken to the hospital' His temperature was

. ";--;, --;--'.'-.-;-" 103", he was treated, and remained in thea00ut l.he commrsslon oI the homlclde,

which subsranrially set r"ril, ti" r".;.;;i;;- hospital for one week'

ed hereinabove. Detective Fondren visited appellant while

he was in the hospital and, after again

GUILT PHASE being advised of his constitutional rights,

l. appellant told Detective Fondren that on

tu Did the court err in finrring rhat r;"''r!li :: *i*'il;i""JTff";Ji,x;

appellant's oral and written statements explanaiion he could give for killing Dick-

were freely and voluntarily given? son was that Tucker was trying to rob him.

Appellant moved to suppress all state- Security Officer King was outside the hos-

ments marle lly him whilc in custorly of thc pital room anrl he could see Dctective Fon-

officcrs, conl"cnrling that thc stttcmcnts rlrcn talking to appcllant, but he could not

werc inarlmissible because thcy wcrc not hcar what was bcing said. They both testi-

freely and voluntarily given. He was held fied that his statement was given freely

in the Jackson City Jail for approximately and voluntarily.

]tr

606 Miss.

After appellant tcstifietl, thc officers

were placed on the stantl in rebuttal, and

testified that the Miranda rights wcre giv-

en, the statements were frecll' antl volun-

tarily made, and that the allllellant knew

what he was doing when he made the state-

ments and executed them. The Jrrocedure

outlined in Agee v. State, 185 So.Zd 671

(Miss.1966) was strictly followetl, and the

trial judge held that the statements ma<le

by appellant were freely and voluntarily

given. The court's fin<ling was supported

by the evidence, and we cannot ovcrrule or

disturb that finding. Clemons r'. State, 316

So.2tl 252 (M iss. 1975).

Appellant testified in his own tlcfense at

both phases of the trial. His tcstirnony was

practically identical with that of his statc-

ments, and reiterated and enlarged upon

those statements.

II.

12) Did thc trial court err in refusing to

sustain defendant's demurrer to the indict-

ment?

Appellant contends that the indictment

here was faulty and subject to <lemurrer for

the reasons that it did not set lorth the

neccssary and essential elements of the

crime of robbery, and dirl not refer to the

proper statute [Mississippi Code Annotatetl

S 9? 3- l9(2)(e) (Su1rp. 1979)1, to charge the

cr ime of capital murder.

The same question was raisetl in Bell v.

State, 360 So.2<l 1206, 1208 09 (Miss.l978),

wherein the Court held that the inrlictment,

such as here, was sufficient to give the

accused fair notice of the crime charged in

clear and intelligible language. Sce a/so

Culberson v. State,379 So.2d 499 (Miss.

1979); Bel/ v. State,353 So.2tl 1141 (Miss'

19??). The trial court properly overruled

the demurrer.

III.

Did the trial court err in rcfusing to

grirnt itgrpcllitn['s rt't1ut'stctl t:ircutttstttn[ittl

cvirlence instructions?

[3,4] Appellant contends that the trial

court should have granted the circumstan-

39I SOIITHERN REPORTER, 2d SERIES

tial evidence instructions requested by him.

Such instructions should be given only in aJ

purely circumstantial evi<lence case. Do)

Priesl r'. State, 377 So.2d 615 (Miss.l9?9).\

The case sult judicetloes not come un(ler that/

classification because there was direct evi-

dence consisting of the statements made by

appellant and his own testimony adduced in

the trial ,n the guilt phase of the case. See

McCray v. State,320 So.2d 806 (Miss.1975).

t5] The trial court granted an instruc'

tion known as the "two-theory instruction"

which should not be given, except in purely

circumstantial evidence cases. Thus, even

though appellant was not entitled to cir-

cumstantial evidence instructions, he re'

ceived the benefit of the principle by the

two-theory instruction granted by the

court.

IV.

Did the trial court err in refusing to

grant appellant's requested peremptory in-

struction and in refusing to reduce the

charge to manslaughter?

[6,7] In passing upon a requested per-

emptory instruction, or motion for directed

verdict, in a criminal case, all evidence most

favorable to the State, together with rea-

sonable inferences, are considered as true

and evidence favorable to the appellant is

disregarded. If such evidence will support

a guilty verdict, the request for peremptory

instruction must be denied, as well as the

motion for directed verdict. Warn v. State,

349 So.2d 1055 (Miss.1977); Toliver v. State,

337 So.2d 1274 (Miss.19?6).

t81 In the case sub judice, appellant ar-

gues that there was no evidence of intent to

rob Dickson and that appellant was an un'

willing participant in the robbery-homicide.

The evidence is overwhelming that appel-

lant was present, aiding and assisting in the

tssrult u1xrn, anrl sltying of, Dickson and in

rcrrroving untl rliscur<ling hin wtllet antl pcr-

sonal cffccts therein, and in the taking of

the T-bird automobile, which was in the

lawful possession and use of Dickson.

:

,i

,

a

I

'-,

t),

{r(lues[ed by him.

c given only in a

'Icncc' casc. De-

I 615 (Miss.1979).

,t come under that

r, was direct evi-

tr:ments marle by

imony ad<luced in

of the case. See

,l 806 (Miss.1975).

rrnted an instruc-

rcory instruction"

,, cxcept in purely

:rscs. Thus, even

t cntitled to cir-

[ructions, he re-

principle by the

granted by the

in refusing to

peremptory in-

to reduce the

a requested per-

,otion for directed

. :rll evidence most

,)gether with rea-

,rnsidered as true

,r the appellant is

'krnce will support

,st for peremptory

,.d, as well as the

't. Warn v. State,

t; Toliver v. State,

;).

rrlice, appellant ar-

irlence of intent to

:,ellant was an un-

robbery-homicide.

lming that appel-

,nrl assisting in the

of, Dickson and in

his wnllct antl llcr-

,l rn thc taking of

which was in the

, of Dickson.

V

I

i

i

r_

I

t:

t

$

J

{

t

l.

I

rf

,:tl

rg

BULLOCK v. STATE

Clte as, Mls3.,39l So.2d 60t

t9] Thc trial court rli<l not r:rr in re- chological examinations aL the Jackson

fusing to grant thc lrcrcmptory instruction Mental Health Center. The motion was

of not guilty. Likewise, the court commit- granted and an examination was conducted.

ted no error in declining to reduce the Appellant then requested that another psy-

charge from capital murder to manslaugh- chiatrist examine him; the court heard the

ter. Evcn so, the qucstion of manslaughter motion and granted same. The record does

was submitted to the jury upon a proper not indicate whether the examination was

instruction. conducted.

v.

tl0l Did the trial court err in refusing

to exclude the testimony of certain State's

witnesscs on the ground that the witnesses

discusse<l their testimony with other wit-

nesses prior to trial and violated the scques-

tration rulc?

Appellant contcnds that Officer Jackson

changed hcr testimony between the tirne of

the sul4rression hearing and the date of

trial, that at the pre-trial hearing, she testi-

fied appellant was handcuffed after his ar-

rest, and, at the trial, she was not sure

whether he had been handcuffed. Appel-

lant claims that the change in Officer Jack-

son's testimony was the result of talking

with other officers subsequent to the pre-

liminary hearing.

An examination of the record does not

support the argument of appellant on this

matter, and indicates that any difference in

Officer Jackson's testimony resulted from

the manner in which questions were

phrased to her. There is no indication of

prejudice resulting to the appellant, and, if

there was a violation of the sequestration

rule, the court has discretion in admitting

the witness's testimony, particularly where,

as here, there was no prejudice. Ford v.

State,2X So.2d 454 (Miss.1969).

VI.

tlll Did the trial court err in refusing

to grant appellant's motion for appointment

of a criminologist or criminal investigator

and a psychiatrist to assist in preparation of

the defensc?

Aplrcllant says thal he was rlenicrl a fair

trial because thc lower court ovcrruled his

motions to employ various experts. Appel-

lant filed a motion for psychiatric and psy-

Miss. 607

Appellant also filed a motion requesting

that the court pay for the expenses of hig

own pathologist, which was substituted for

a motion to employ a criminal investigator.

The appellant did not outline any specific

costs for such an investigator, and did not

indicate to the court in any specific terms

as to the purpose and value of such an

individual to the defense. We are of the

opinion that the lower court committed no

error in declining to authorize expenses for

employing such expert and investigator.

Davis v. State, 374 So.2d 1293 (Miss.1979);

Laughter v. State, 235 So.2d 468 (Miss.

19?o).

VII.

tl2l Did the lower court err in admit-

ting photogtaphs of the deceased during

trial?

The State offered in evidence, and the

lower court admitted, black and white pho-

tographs of the victim after he had been

slain. Appellant claims that the pictures

were inflammatory and had no probative

value. The photographs showed how the

body was weighted with concrete blocks

and how the garden hose was wound

around it to hold the blocks in the body for

the purpose of submerging it. The condi-

tion of the body, as reflected by the photo-

graphs, corroborated the tcstimony of the

pathologist, particularly concerning the

wounds upon the body.

The trial judge has wide discretion in

admitting photographs into evidence, and

we are of the opinion that he did not abuge

his discretion in admitting the photographs

of the victim. Irving v. State, 361 So.2d

1360 (Miss.1978); Mallette v. State, 349

So.2d 546 (Miss.197?).

l;,r

rl,l

ili

'l .l

:i,j

t'. 'l

l,,il

i;,i,

iii:

i ,:

I

liir

i

li

,ll

i

I

l,

i

i,l

I

I

i

:i

I

l

I

I

I

I

I

I

*

)

608 Miss. 39I SOUTHERN REPORTER,2d SERIES

VIII.

tlSl Did the trial court err in admitting

the testimony of Dr. Galvez and in refer-

ring to a photograph introduced by his tes-

timony?

Appellant argues that the evidence of the

pathologist, Dr, Galvez, was cumulative and

was not necessary to prove the corpus <le-

licti, since the crime had bcen established

by previous witnesses. Appellant relies

upon Jack.son v. State, BBT So.2d 1242 (Miss.

19?6) for the principle that the State's use

of a pathologist's testimony is unnecessary

to prove corpus delicti where the deceased

was found in an unusual place under un-

usual circumstances. However, Jackson

does not support his argument on this point.

The pathologist's testimony was proper and

beneficial to establish the exact cause of

death, which resulted from a fracture of the

victim's skull. It further reflected that ab-

sence of water in the lungs indicated death

to be due to the head injury rather than

drowning. The testimony and evidence

were properly admitted.

IX.

tl4l Did the trial court err in allowing

certain witnesses to testify and in violating

the bifurcated trial principle mandated by

Jackson v. State?

Allpellant contends that the court erred

in allowing Larry Keen, W. L. Moss and

James Jones to testify about conversations

they had with Mark Dickson the night he

was killed. Appellant says that such testi-

mony, together with the photographs,

should not be introduced during the guilt

phase of the trial, and, if at all, only during

the sentencing phase. The testimony of

such witnesses was to the effect that Dick-

son stated he was not in the mood for

drinking and that he was going home be-

cause he did not have any money on him.

Appellant's attorney conducted a rigid

cross-cxamination of those witnesses con-

cerning what Dickson had told them. Thc

dircct examinati<ln antl the cross-examina-

tion were not prejudicial to appellant, and

the re is no merit in the assignment.

Stringer v. State,279 So.2d 156 (Miss.19?3);

Fielder v. State,235 Miss. 44, 108 So.2d 5g0

(195e).

x._xr.

Did the trial court err in not permitting

appellant to cross-examine witnesses as to

Mark Dickson's character and did it err in

refusing to grant a mistrial?

Did the trial court err in allowing Larry

Keen and James Jones to testify to the

good character and habits of Mark Dickson

and in not declaring a mistrial when Larry

Keen mentioned the bad character of appel-

lant and in not allowing defense counsel Co

cross-examine those witnesses as to the bad

character of Mark Dickson?

[15] Assignments of error IX, X and XI

involve substantially the same question(s).

The witnesses mentioned above testified 0o

statements made by Dickson, which have

been covered in Assignment IX and which

do not constitute reversible error.

Appellant contends that the Statc at

tacked the character of appellant by the

following question and answer:

a. Did Mark Dickson, to your knowl-

edge, know either Rickey Turner or

Crawford Bullock?

A. I think he knew Bullock. He knew

Bullock because Bullock was raised in

our neighborhood and we had seen him

before out. I was with Mark at the

Zodiac Lounge and Crawford [Bullock]

was engaged in a fight there and we

saw him there, you know.

BY MR. EVANS:

Your Honor, I am going to object to

this and move for a mistrial-ask that

that be stricken from the record and

move for a mistrial. This is absolutely

irrelevant. The testimony is inadmissi-

ble, it's prejudicial and it's just not sup

posed to be in this case.

BY THE COURT:

Members of the jury, disregard the last

statement that the witness made. Do all

of you tell me that you can disregard the

last statement?

(Jurors nodding affirmative).

The tr

jection

instruct,

and ask,

ir. The

reply.

the Stat

the jur.r

gwer, ar

error.

(Miss.19

174 So

13? Mis

Did t'

nesses I

automol

night ol

116, I'

court t,

testify

T-bird .

night o

Dickson

mobile.

larceny

party t

bailee ,

So.2d '

State, li

ment is

tl8I

introdu

of Mar

ApP,'

the gr

flamm.

his dis,

Voyles

May v

tlel

Instrur

murder

App,

signme

rt

,:

Ir

44, 108 So.2d 590

in not permitting

re witnesses as to

,' and did it err in

'irrl?

in allowing LarrY

to testify to the

s of Mark Dickson

ristrial when LarrY

character of appel-

defense counsel to

,csses as to the bad

,ln?

rrrror IX, X and XI

r same question(s).

I above testified to

ckson, which have

nent IX and which

rble error.

hat the State at-

f appellant by the

rnswer:

'n, to your knowl-

Rickey Turner or

Bullock. He knew

llock was raised in

'rd we had seen him

with Mark at the

Crawford [Bullock]

fight there and we

know.

going to object to

mistrial-ask that

,rn the record and

This is absolutelY

rrnony is inadmissi-

,xl.it's just not sup

r', rlisregard the last

ilncss mttle. Do all

,ru can disregard the

rnative).

IltlLLOCK v. STATE

Cite as. Mlss.. 391 So.2d 0Ol

The trial judge sustainerl appellant's ob- erroneously given for the reason that there

jection to the question and answer, and was no requirement for the jury to find

instructed the jury to disregard the answer, Mark Dickson was in fact killed. The perti-

and askc<l the jury if they could disregard nent part of the instruction follows:

it. The jury gave the judge an affirmative "[A]nd, if the Jury further finds from the

rcllly. The answer was not responsive to evidence in this case, beyond a reasonable

the State's question, the trial ju<lge directed doubt, that on said date aforesaid, while

the jury to disregard the question and an- engaged in the commission of the afore-

swer, and it rloes not constitute reversible said robbery, if any, that the said Craw-

error. Ilotifiekl v. State, 2?5 So.2d 851 ford Bullock, Jr., did alone, or while act-

(Miss.l9?3); Hughes v. State, 1?9 Miss. 61, ing in consert [sic] with another, while

l?4 So. 557 (193?); Dabbs v. Richardson, present at said time and place by consent-

13? Miss. 789, 102 So. 769 (1925).

XII.

Did the trial court err in permitting wit-

nesses to testify as to the ownership of the

automobile driven by Mark Dickson on the

night of the homicide?

[6, l7] Appellant contends that the

court erred in permitting Larry Keen to

testify about the ownership of the gray

T-bird automobile Dickson was driving the

night of the homicide. It is undisputed that

Dickson was in possession of the said auto-

mobile. An indictment charging robbery or

larceny of property is properly laid in the

party having possession, either as owner,

bailee or agent. Mahfouz v. State, 303

So.2d 461 (Miss.1974); Minneweather v.

State, 55 So.2d 160 (Miss.1951). The assign-

ment is without merit.

XIII.

U8l Did the trial court err in permitting

introduction of the high school photograph

of Mark Dickson?

Appellant objected to its introduction on

the ground that it was irrelevant and in-

flammatory. The trial judge did not abuse

his discretion in admitting the photograph.

Voyles v. State,362 So.2d 1236 (Miss.1978);

ilIay v. State, 199 So.2d 635 (Miss.1967).

xIv.

[9] Did the trial court err in granting

Instruction # 15, which was the capital

murtler instruction?

Appellant cites no authority on this as-

signment, but simply argues that it was

Miss. 609

ing to the killing of the said, Mark Dick-

son, and that the said Crawford Bullock,

Jr., did any overt act which was immedi-

ately connected with or leading to its

commission, without authority of law,

and not in necessary self defense, by any

means, in any manner, whether done with

or without any design to effect the death

of the said Mark Dickson,

(Emphasis added)

It may be noticed that the instruction

does require a finding that Mark Dickson

was killed, and it correctly sets forth the

issues which must be decided by the jury

before the accused could be convicted. Wil-

liams v. State, 3L7 So.%l 4?5 (Miss.1975).

AssignmenLs of Error XV through XXIV

deal with the refusal of the trial court to

grant certain instructions requested by the

appellant. Was it emor to refuse those

instructions?

xv.

t20l Instruction D-8 was the single jur-

or instruction. The appellant argues that

the instruction was "a fair and accurate

representation of the law" and should have

been granted. The principle of the instruc-

tion was covered in Instruction # 12, and,

although in different language, it was not

error to refuse the instruction. fuagan v.

State, 318 So.2d 8?9 (Miss.l975).

xvI.

t2l] Instruction D-9 was condemned in

McNamce v. State, 313 So.2d 392 (Miss.

19?5) as being an improper comment on the

weight and worth of the defendant's testi-

mony and was properly refused.

:

1

i

it

I

2'

.!

T

I

I

r

t;{

r,l

i

l,

I

I

L

i:

il

ii

il

610 Miss.

Instruction D- l0 was correctly refused

by the lower court since it should be given

only in a llurely cirOumstantial evidence

casc.

XVIII.

I22) Instruction D-30 would havc tokl

the jury that it need not find any mitigat-

ing circumstances in order to return a sen-

tcnce of Iife imltrisonment; that a life sen-

tence may be returned regardless of the

cvirlcnce. The instruction was in direct

conflict with Instruction D-20 which told

the jury to weigh the mitigating circum-

stances against any aggravating circum-

stances before returning a verdict and was

correctly refused under Jackson v. State,

supra.

xIx.

l23l Instruction D-31 would have told

the jury it was instructed there is nothing

that would suggest the decision to afford an

individual defendant mercy violates the

constitution. That statement was taken

from language set forth in the opinion of

Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 15S, 96 S.Ct.

2909, 14 L.Ed.2d 859 (1976). It is simply a

statement of the opinion, and was not in-

tended as an abstract proposition of law to

be given in jury instructions.

xx.

t24) Instruction D-.33 would have in-

structed the jury it was to presume that, if

the accused was sentenced to life imprison-

ment, he would spend the rest of his life in

prison, and the jury was to presume that, if

the accused was sentenced to death, he will

receive lethal gas until he is dead. The

instruction was improper and was calculat-

ed to confuse the jury.

xxI.

Instruction D.34 and thc sense of same,

was contained in Instruction # 14, which

was grantetl by the court, and it was not

error to refuse D-34.

39I SOUTHERN REPORTER,2d SERIES

xvil. xxrr._xxlv.

Instructions D-35, D-36 and D-B? did

not put the lower court in error for their

refusal. They were either improper in-

structions, or the proper and correct parts

were included in Instruction # 14 granted

by the court.

xxv.

125) Did the court err in failing to sus-

tain appellant's motion for a mistrial made

during the State's closing argument and in

not sustaining objections to prejudicial and

inflammatory arguments of the district at-

torney?

Appellant contends that, during closing

argument, the district attorney referred to

his problem with psychosis as being a possi-

ble explanation for committing the crime.

He objected to the remark and stated that

such remark was not supported by the evi-

dence. However, appellant himself intro.

duced in evidence the hospital record of

appellant which indicated that on May lb,

1978, he was admitted to the University

Medical Center for treatment and the diag-

nosis indicated that he suffered from psy-

chosis. Such evidence was fair comment in

the argument by the district attorney.

t26l Appellant next argues that the dis-

trict attorney gave a false impression to the

jury of the elements of the crime of roh,

bery. Part of the argument follows:

"Now, look, if you see a guy on the

street, do you walk up and whop him on

the head and drop boulders on him and

hit him with a two by four and then you

take his billfold and you take his car, but

you didn't rob him. Do you believe

that?"

I27) The trial judge overruled the objec-

tion and stated that it was final argument.

There is wide latitude for attorneys to ar-

gue cases to juries, and we do not think

that such remarks of the district attorney

were improper or prejudicial.

iZSl Appellant objects to argument of

the district attorney, which he says wan

improper because it indicated that finger-

I).

(1,

ir

fr

i

ll

t

I

cr

lr

I

I

I'

l)

,:

!

(

i'j'

I

,

$

hp

{

I

i

)

r

-6

fl

{

.,i.

,+

Il

f

.:(

:,

.l;

ri

{1

,;|

lt;

n{

I

,

i.

$rI'I

itr

4

4

t{.Y

.1

tLt

.ti,

xIv.

) 36 and D -37 did

t in error for their

'ither improper in-

r and correct parts

ction # 14 granted

rr in failing to sus-

for a mistrial made

rg argument and in

r to prejudicial and

s of the district at-

lrat, during closing

,ttorney referred to

;is as being a possi-

rmitting the crime.

trk and stated that

pported by the evi-

lant himself intro-

hospital record of

d that on May 15,

to the University

:nent and the diag-

,uffered from psy-

,rs fair comment in

t rict attorney.

,rgues that the dis-

rr impression to the

the crime of rob-

rent follows:

)iee a guy on the

, and whop him on

,rltlers on him and

four and then you

,u take his car, but

Do you believe

rerruled the objec-

;rs final argument.

,r attorneys to ar-

u'e do not think

, rlistrict attorney

,'ial.

r to argument of

rrich he says was

"tted that finger-

IIULLOCK v. STATE

Clte as, Mlss.,39l So.2d 601

Miss. 61f

l

prints coultl not be taken from all the evi- Here, appellant was not restricted in any

dence. There was testimony that it was manner in the presentation of his defense,

impossible to remove latent fingerprints the record reflects that he was not preju-

from concrete and certain other materials diced by proceeding into the sentencing

introduced in evitlence. This was fair argu- phase and that he had a fair trial' The

ment, and did not constitute error. lower court proceeded under the guidelines

of Jackson v. State, and there was no error

t29l Appellant lastly objects to the dis- in so doing.

trict attorney's refcrence to the statement

made by applllant to the investigating offi- XXVII'

cers as lr"ing " confession. t3U Was the verdict of the jury con-

rhe sratemenr was incriminaringi .on :1ffi,:: jffi;,flffl#i,J1tl:Jijl;

nectcrl appellant with the crime, and may

properly be rcrerrert ;;"; ;;;;J;. prejudice?

Also, during the trial of the case, appel- The sense and principle of this assign-

lant,s own counsel referred to the state- ment of error has been discussed in Assign-

ment as being a confession. There is no ment IV' wherein the appellant claimed

.' that the court erred in declining his request

ment ln Lne conLenllon.

for a peremptory instruction of not guilty.

As stated there, the evidence for the

xxVI' State, including the oral and written con-

t30] Did the lower court err in denying fessions of appellant, his testimony at the

appellant's motion for a recess until the trial, and the physical evidence, unless re-

following morning before procee{ing to the jected by the jury, was amply sufficient to

sentencing phase of the trial? prove beyond reasonable doubt the guilt of

The jury returned a verdict of guilty of the appellant and the verdict was not con-

capital murder in the first phase of the trial trary to the great weight of the evidence'

at approximately 8:00 p. m. The jurors had XXVIII.

eaten supper at that time. The trial judge

indicated his desire to proceed with the t32l Did the lower court err in overrul-

sentencing phase of the case, whereupon, ing appellant's motion to quash the indict'

appelanr moved rhe courr to recess until 1":::XL.:i:::lining

to declare the statut'e

the fottowing morning for that purpose' unconsllLuIlonal

'

The trial judge asked the jury whether any This Court has spoken on the constitu-

of them were too tired io proceed, they tionality of the death penalty statute and

indicated that they were not, and the judge has determined that the statute' as imple-

assured the jury ihut, if they became tired mented by the legislature and construed by

at any time, he woultl stop the proceedin* the court' is constitutional' ln Coleman v'

and retire for the evening. The trial pro- State, 378 So.2d 640 (Miss'l'979), the Court

ceeded in the sentencing ph".u and the jury said:

returned a verdict for ii" death penalty at "This contention is without merit' The

approximately 11:00 p. m. The facts of the constitutionality of the death penalty as

cuse srb judice may be distinguished from imposed under Section 99-19-101, et seq'

that of Thornton v. State,369 So.2d 505 has been firmly established' Proffitt v'

(Miss.19?9) where two of the <lefen<lant's Florida, 428 U.S. 242, 96 s'ct. 2960' 49

sttorneys, one approximately seventy (?0) L'Ed'2d 913 (1976); Washington v' State'

yu"., oid and ons in ill health, *"." not ubl" 361 So.2d 61 (Miss.1978)." 3?8 So'2d at

io properly function because of their in- ul'

firmitics. The attorneys were also rcstrict- In our opinion, there were no reversible

ed in their final argument to short periods errors in the guilt phase of the trial and the

of time. case should be, and is, affirmed'

612 Miss.

SENTENCING PHASE

Mississilrlli Corlc Annotatcrl Scction 99

l9-105 (Supp. 1979) provides thc following:

"(1) Whenever.[he death penalty is im-

posed, and upon the judgment becoming

final in the trial court, the sentence shall

be reviewed on the record by the Missis-

sipJri Supreme Court. The clerk of the

trial court, within ten (10) days after

receiving the transcript, shall transmit

the entire record and transcript to the

Mississippi Supreme Court together with

a notice prepared by the clerk and a

report prepared by the trial judge. The

notice shall set forth the title and docket

number of the case, the name of the

defendant and the name and address of

his attorney, a narrative statement of the

judgment, the offense, and the punish-

ment prescribed. The report shall be in

the form of a standard questionnaire pre-

pared and supplied by the Mississippi Su-

preme Court, a copy of which shall be

served upon counsel for the state and

counsel for the defendant.

(2) The Mississippi Supreme Court

shall consider the punishment as well as

any errors enumerated by way of appeal.

(3) With regard to the sentence, the

court shall determine:

(a) Whether the sentence of death was

imposed under the influence of passion,

prejudice or any other arbitrary factor;

(b) Whether the evidence supports the

jury's or judge's finding of a statutory

aggravating circumstance as enumerated

in section 99-19-101; and

(c) Whether the sentence of death is

excessive or disproportionate to the pen-

alty imposed in similar cases, considering

both the crime and the defendant.

(4) Both the defendant and the state

shall have the right to submit briefs with-

in the time provided by the court, and to

present oral argument to the court.

(5) The court shall include in its dcci-

sion it rcfcrence to thosc similar clscs

which it took into consideration. In a<kli-

tion to its authority regar<ling corrcction

of errors, the court, with regard to review

of death sentences, shall be authorized to:

39I SOUTHERN REPORTER,2d SERIES

(a) Affirm the sentence of death; or

(b) Sct the sentencc aside and remand

the case for modification of the sentence

to imprisonment for life.

(6) The sentence review shall be in ad-

dition to direct appeal, if taken, and the

review and appeal shall be consolidated

for consideration. The court shall render

its decision on legal errors enumerated,

the factual substantiation of the verdict,

and the validity of the sentence."

We have held in Jackson, and pursuant to

thc above section, that cases in which a

death sentence is imposed will be automati-

cally reviewed as preference cases by this

Court; that the record will be reviewed and

comllared with similar cases to determine

whether the punishment of death is too

great when the aggravating and mitigating

circumstances are weighed against each

other in order to assure that the death

penalty will not be wantonly or freakishly

imposed; and only will be inflicted in a

consistent and even-handed manner under

like or similar circumstances.

Sinee Jackson v. State, 337 So.?tJ L242

(Miss.1976), eleven (11) capital murder cases

have been decided by this Court. Seven (7)

of those cases have involved felony (rob.

bery) murder. Reddix v. State, 381 So.Zt

999 (Miss.1980); Jones v. State, 381 So.2d

983 (Miss.1980); Culberson v. St8te, 379

So.2d 499 (Miss.1979); Irving v. State, 361

So.2d 1360 (Miss.1978); Voyles v. State,362

So.2d 1236 (Miss.1978h Washington v.

State, 361 So.2d 6l (Miss.1978); Bell v.

State, 360 So.2d 1206.

We have carefully reviewed those cases

and compared them with the case and sen-

tence sub judice. Appellant contends that

the extent of his involvement in the crime

was as an accomplice, who did not strike the

fatal blow, and that Tucker was the princi-

pal, who killed the victim. He argues that

Tucker was given life imprisonment by the

jr.y, which tricd him; that appellant

should not receive I grcater or harsher pen-

alty than Tucker; and that appellant'e

death sentence should be reduced to life

imprisonment.

.l

..u n

S,,

.t. /'

1rtr

lt

,,

I.T

r,,{

,, la

,,1

\

i

L

.!,1

qiltr

' of death; or

,le and remand

,rf the sentence

shall be in ad-

taken, and the

)rc consolidated

'rrt shall render

rs enumerated,

of the verdict,

,rtence."

rnd pursuant to

;es in which a

ill be automati-

{j cases by this

,e reviewed and

s Lo determine

.f death is too

and mitigating

I against each

t.hat the death

ly or freakishly

' inflicted in a

..manner

under

'.\37 So.2d 7212

al murder cases

rurt. Seven (7)

,rl felony (rob-

Itate, 381 So.2d

llate, 381 So.2d

v. State, 379

,g v. State, 361

las v. State,362

Washingl,on v.

1978); Bell v.

lcrl those cases

c case and sen-

t contends that

nt in the crime

rrl not strike thc

was the princi-

lle argues that

ronment by the

thirt appcllant

or harsher llcn-

lrat appellant's

reduced to life

;

I

,

t

I

it

t

i

ln Coleman v, State, supra, Coleman was

found guilty by a jury in the robbery-mur-

der of one Burkett, and was given death.

He was sixteen (16) years of age and fired

the fatal shot that killed Burkett. His ac-

complice in the crime was permitted to en-

ter a guilty plea to manslaughter and was

sentenced to a term of years in the peniten-

tiary. In comparing Coleman's death sen-

tence to that of other cases heard by this

Court, we said:

"Having carefully compared the case at

bar with these cases in which the sen-

tence of death was imposed, we are of the

opinion that the sentence of death in this

case 'is excessive or disproportionate to

the penalty imposed in similar cases, con-

sidering both the crime and the defend-

ant.'

ln lrving, Washington and Bel/, the

killings were totally senseless and com-

mitted upon hapless victims unarmed and

unable to protect themselves. The cir-

cumstances in this case are strikingly dif-

ferent. Here, Harry Burkett, the victim,

upon seeing the foot of Sims protruding

from under the pickup truck, began fir-

ing his pistol. Only after being fired

upon did the 16-year-old Coleman shoot.

Again, Coleman had the opportunity to

shoot Mrs. Burkett, who was an eyewit-

ness, but did not. He fled the scene

instead.

Under the specific authorization of sub-

section (5)(b) of S 99 -19- 105, this Court

affirms the conviction but reverses and

sets aside the death sentence and re-

mands this case to the trial court for

modification of the sentence to imprison-

ment for life." 378 So.2d at 650.

ln Culberson v. State, supra, Culberson

was found guilty of robbery-murder and

was given the death penalty. The principal

evidcnce and witncss against Culberson was

an accomplice, Alvarese Pittman. His testi-

mony was substantially to the effect that

he was with Culberson, they were going to

rob the victim, that he did not know Culbcr-

son harl a pisLol until Culbcrson shot anrl

killed thc victim. On a plca of guilty, Pitt-

man was given a comparatively light sen-

tence in the penitentiary. The Court said,

in affirming the death penalty:

BULLOCK v. STATE

Clte as, Mlss.,391 So.2d 60l

Miss. 613

"This leaves the question of whether

the words in Subsection (3)(c), 'imposed in

similar cases, considering both the crime

and the defendant,' include for our re-

view and comparison the exact and there-

fore similar crime of the accomplice and

the sentence received by him for it. We

construe the language to include not only

the capital cases heretofore determined

by this Court in which the death sentence

has been imposed or rejected on the mer-

its, but also cases involving multiple de-

fendants when one participant is given

the death penalty and an accomplice less

than death. One of the questions arising

in such cases is whether a sentence of less

than death to an accomplice was a result

of prosecutorial discretion. An affirma-

tive answer raises a second question, was

the discretion abused?

We hold prosecutorial discretion was

not abused because Pittman, who did not

fire the fatal shot, was permitted to plead

guilty to manslaughter, while Culberson,

the one who fired the fatal shot, was

given the death penalty. We hold the

death penalty was not applied capricious-

ly in this case. It is a proper sentence for

the senseless and unprovoked murder

committed by Culberson, who, after first

knocking the victim down with a table

leg, then shot the victim while he was

lying on the ground begging, 'Help me,

help me."' 3?9 So.2d at 510.

ln Lockett v. Ohio,438 U.S. 586, 98 S.Ct.

n54,57 L.Ed.zd 973 (1978), Sandra Lockett

was charged with aggravated murder with

aggravating specifications. She and three

(3) others conspired to rob a pawnbroker's

shop. Lockett remained in the getaway

automobile with the engine running, the

other three entered the pawn shop and dur-

ing the robbery, Parker, one of the three,

killcrl thc proprietor. Prior to trial, Parker

lllcarlerl guilty to the murder charge, and

agreed to testify against Lockett and the

other two. In return, the prosecutor dis-

missed the aggravated robbery charge and

I

ll

rl

II

i

I

I

I

rl

I

d

I

I

1

I

t

l

I

q

1

6f4 Miss. 391 SOUTHERN REPORTER, 2d SERIES

the specifications to the murder charge

which limited the possibility that Parker

could receive the death penalty.

Two weeks before Lockett's separate tri-

al, the prosecutor offered to permit her to

plead guilty to voluntary manslaughter and

aggravated robbery, offenses which carried

a maximum penalty of twenty-five (2b)

years imprisonment. Prior to the trial, he

offered to permit her to enter a plea of

guilty to aggravated murder without speci-

fications, an offense carrying a mandatory

life penalty. These plea bargaining offers

were rcjected by Lockett; she was tried

and was given the death penalty.

Although thc case was reverserl on anoth-

er ground, the question was raised as to

whether or not Lockett's conviction as an

aider and abetter of the actual killer was

invalid on the ground that the interpreta-

tion by the Ohio Supreme Court of the

complicity provisions of the Ohio statute,

under which the defendant was convicted,

was so unexpected that it deprived her of

her due process right to fair warning of the

crime with which she was charged.

The United States Supreme Court held

that her conviction as an aider and abetter

of the actual killer was not invalid.

ln Coppola v. Commonvealth, 220 Ya.

-,

257 S.E.zd 797 (1979), the Virginia

Supreme Court held that a co-defendant is

not necessarily entitled to commutation of

the death sentence because an equally cul-

pable accomplice, on substantially the same

evidence, has been sentenced to life impris-

onment. That Court held that a determina-

tion of the proportionability of punishment

requires only that the death sentence not be

so incommensurate with his conduct, meas-

ured by other jury decisions, involving simi-

lar conduct.

t33l In the case at bar, there is no rec-

ord of the aggravating circumstances and

mitigating circumstances in the trial of

Tuckcr, antl it is not Jxlssiblc to rlutt:rrnine

whttt circurtrstonces influencurI tlrc jury in

its life venlict. The law is wcll scttletl in

this state that any person who is present,

aiding antl abctting another in the commis-

sion of a crime, is equally guilty with the

principal offender. Jones v. State, B0?

So.2d 549 (Miss.1975); Bass v. State, BL

S<r.2d 495 (Miss.l970); McBroom v. Statc,

217 Miss. 338, M So.2d 1,14 (1953).

[34] When we compare the present case

to other capital cases, which have been af-

firmed by this Court on the death penalty,

the present robbery-murder is equally as

wanton, cruel, senseless, heinous and atro-

cious as those. The evidence is overwhelm-

ing that appellant was an active participant

in the assault and homicide committed upon

Mark Dickson and, in our opinion, is not so

disproportionate, wanton or freakish when

compured to those crimes so as to require

this Court to reduce the sentence to life

imprisonment.

Therefore, the judgment of the lower

court is affirmed and Wednesday, the l0th

day of September, 1980, is set as the date

for execution of the sentence and infliction

of the death penalty in the manner provid-

ed by law.

AFFIRMED AS TO GUILT PHASE:

AFFIRMED AS TO SENTENCING

PHASE.

PATTERSON, C. J., SMITH and ROB-

ERTSON, P. JJ., and SUGG, WALKER,

BROOM, BOWLING and COFER, JJ., con-

cur.

Chester Lee COOLEY

v.

STATE of Mississippi.

No. 51807.

Supreme Court of Mississippi.

Aug. 27, 1980.

As Modificrl On Dcnial of Rehearing

I)cc. 17, 1980.

Dcfendant was convicted in the Circuit

Court of Jones County, James D. Hester, J.,

I

j

;

I

t

:

I

;

i

1.

,I,

Sti

'{t,

',h .,