Order Granting Motion of Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

December 9, 1987

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Chisom Hardbacks. Order Granting Motion of Amicus Curiae, 1987. 88bbe380-f211-ef11-9f8a-6045bddc4804. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0c8d5c1c-e555-4541-a057-3a9cf43850bd/order-granting-motion-of-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 05, 2026.

Copied!

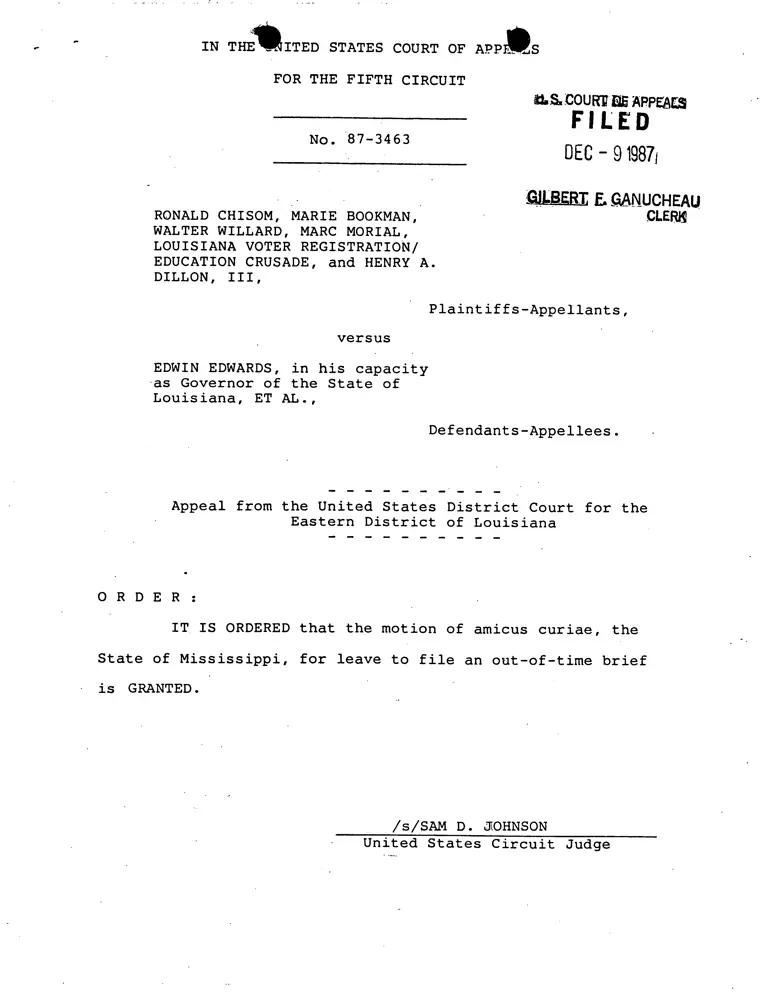

IN THE* STATES COURT OF APPAL

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 87-3463

RONALD CHISOM, MARIE BOOKMAN,

WALTER WILLARD, MARC MORIAL,

LOUISIANA VOTER REGISTRATION/

EDUCATION CRUSADE, and HENRY A.

DILLON, III,

versus

EDWIN EDWARDS, in his capacity

as Governor of the State of

Louisiana, ET AL.,

114,, COURIIIMAPPEALS

FILED

OEC - 919871

AMR" E. CANUCHEAU

CLERK

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Louisiana

ORDER:

IT IS ORDERED that the motion of amicus curiae, the

State of Mississippi, for leave to file an out-of-time brief

is GRANTED.

/s/SAM D. JOHNSON

United States Circuit Judge

LAW OFFICES

CUPIT & MAXEY

P.O. BOX 22666

30.4 NORTH CONGRESS STREET

J AC K SON, M ISSISSIPPI 39205

DANNY E. CUPIT

JOHN L. MAXEY, II

JOHN G. JONES

SAMUEL LEE BEGLEY

or COUNSEL:

JOHN L. QUINN

FEDERAL EXPRESS

December 8, 1987

The Honorable Gilbert F. Ganucheau

Clerk of the Court

United States Court of Appeals

600 Camp Street

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

Re: No. 87-3463

Ronald Chisom, et al.

Edwin Edwards, et al.

Dear Mr. Ganucheau:

TELEPHONE

(601) 355-1553

TELECOPIER

(60)) 355-1571

Enclosed for filing in the above styled cause are

the original and three copies of the motion of the State of

Mississippi to file an amicus curiae brief and the original

and six copies of the brief in the event leave of the Court

is granted.

It is our understanding that this case is set for

oral argument on December 10, 1987, and, of course, the

State of Mississippi does not seek to participate at oral

argument. We would, however, appreciate your immediate

attention to this matter so that the Court will be aware of

the interest the State of Mississippi has in the outcome of

the subject matter.

By copy of this letter, a copy of the motion and

two copies of the brief are being served on all counsel of

record.

Please give me a call if you have any questions.

Yours sincerely,

CUPIT & MAXEY

BY

JLM:lah

Enclosures

cc: All counsel of record

•

NO. 87-3463

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

RONALD CHISOM et al.,

V .

EDWIN EDWARDS, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

Defendants-Appellees.

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF

ON BEHALF OF THE STATE OF MISSISSIPPI'

Comes the State of Mississippi through counsel to

request leave of the Court to file a brief as amicus curiae

on behalf of the State of Mississippi pursuant to Rule 29 of

the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure. As a state, the

State of Mississippi is given a presumptive right to file

such mnicus brief. Since this brief is filed out of the

normal schedule, the State of Mississippi requests that the

Court permit this brief to be filed and considered, without

oral argument.

The brief in proper form and required number is

attached to this motion.

This day of December, 1987.

Respectfully submitted,

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI

AMICUS CURIAE

Stephen J. Kirchmayr

Deputy Attorney General

Post Office Box 220

Jackson, Mississippi 39205

601-359-3680

Hubbard T. Saunders, IV

Crosthwait, Terney . & Noble

Post Office Box 2398

Jackson, Mississippi 39205

(601) 352-5533

nj axey, II •

if' o P Maxey Office Box 22666

Jackson, Mississippi 39205

COUNSEL FOR AMICUS CURIAE

CERTIFICATE

The undersigned hereby certifies that on the date

set forth hereinafter, a true and correct copy of the above

and foregoing Brief of Amicus Curiae, State of Mississippi,

in support of Defendants-Appellees was caused to be served

upon the following counsel of record:

THE HONORABLE WILLIAM J. GUSTE, J

Attorney General

KENDALL L. VICK, ESQUIRE

Assistant Attorney General

EAVELYN T. BROOKS, ESQUIRE

Assistant Attorney General

Louisiana Department of Justice

234 Loyola Avenue, 7th Floor

New Orleans, Louisiana 70112

-2-

• -'

M. TRUMAN WOODWARD, JR., ESQUIRE

110 Whitney Building

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

BLAKE G. ARATA, ESQUIRE

210 St. Charles Avenue

Suite 4000

New Orleans, Louisiana 70170

A. R. CHRISTOVICH, ESQUIRE

1900 American Bank Building

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

MOISE W. DENNERY, ESQUIRE

21st Floor, Pan American Life Center

601 Poydras Street

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

WILLIAM P. QUIGLEY, ESQUIRE

631 St. Charles Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

PAMELA S. KARLAN, ESQUIRE

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

This kfrit the day of December, 1987.

Ae

t , J9gN MAXEY, II

ft(.1

NO. 87-3463

In The

United States Court of Appeals

for the

Fifth Circuit

RONALD CHISOM, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

V0

EDWIN EDWARDS, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE STATE OF MISSISSIPPI

IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANTS-APPELLEES

Stephen J. Kirchmayr

Deputy Attorney General

P. 0. Box 220

Jackson, MS

601-359-3680

Hubbard T. Saunders, IV

Crosthwait, Terney & Noble

P. O. Box 2398

Jackson, Mississippi 39255-2398

(601) 352-5533

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

John L. Maxey, II

Special Counsel

P. O. Box 22666

39205 Jackson, MS 39205

601-355-1553

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTERESTS OF AMICI CURIAE 1

STATEMENT OF CASE 2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT 2

ARGUMENT 1

1. SECTION TWO OF THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT APPLIES

ONLY TO "REPRESENTATIVES", WHICH JUDGES BY

DEFINITION ARE NOT 3

2. THE LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF SECTION 2 OF THE

VOTING RIGHTS ACT DOES NOT SUPPORT THE CONCLUSION

THAT IT SHOULD BE APPLIED TO JUDICIAL ELECTIONS 11

CONCLUSION 13

TABLE OF CASES

Baker v. Carr, 369, U.S. 186, 82 S. Ct. 1691,

72 L.Ed. 2d 663(1962) 7,8

Buchanan v. Rhodes, 249 F. Supp. 860, 865

(N.D. Ohio 1966). appeal dismissed, 385 U.S. 3,

87 S. Ct. 33, 17 L.Ed.2d 3 (1966) 9,10

Chishom v. Edwards, 659 F.Supp.183 (E. D. La. 1987) 2

City of Mobile, Alabama v. Bolden, 446 U.S .55 (1980) 11

Consumer Products Safety Commission v. GTE Sylvania,

Inc. 447 U.S. 102, 108, 100 S. Ct.2051, 2056,

64 L. Ed. 2d 766 (1980) 5,12

Director v. Perni North River Associates,

459 U.S. 297, 319-20, 103 S. Ct. 634, 648,

74 L. Ed. 2d 465, 482 (1983) 11

Escondido Mutual Water v. La Jolla, 466 U.S.765, 772,

104 S. Ct. 2105, 2110, 80 L. Ed. 2d 753 (1984) 5

New York State Association of Trial Lawyers v.

Rockefeller, 267 F. Supp. 148(S.D.N.Y. 1967) 9,10

Piper v. Chris-Craft Industries, Inc. 430 U.S. 1,

97 S. Ct. 926, 51 L. Ed. 2d 124 (1977) 12

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 84 S. Ct. 1362,

12 L.Ed.2d 506 (1964) 8

Stokes v. Fortson, 234 F. Supp. 575, 577

(N. D. of Ga. 1964) 8,9

Thornberg v. Gingles, 106 S. Ct. 2752 (1986) 11

Touche Ross and Company v. Redington 442 U.S. 560,568,

99 S. Ct. 2479, 61 L.Ed.2d 82 3,4

Wells v. Edwards, 347 F. Supp. 453, 454-55

(M.D. La. 1972) (three-judge court), aff'd mem.,

409 U.S. 1095, 93 S. Ct. 904, 34 L. Ed. 2d 679 (1973) 10

Martin v. Allain, United States District Court for the

Southern District of Mississippi, Civil Action No.

J84-0708(B) 1,2

Martin v. Allain, 658 F.gupp. 1183,1200 (1987) 2

11

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act,

as amended in 1982, 42 U.S. §1973 1 2,3,4,5,8,10,11,12

Alexander Hamilton, Federalist, No. 78 7

Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America (1835) 7

Commentaries on the Laws of England.

(Chicago: Callaghan and Company, 1871) 1. 69-70 5,6

Fifteenth Amendment, U. S. Constitution 10

Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause

U. S. Constitution 10,11

111

'NO. 87-3463

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE

FIFTH CIRCUIT

RONALD CHISOM et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

V .

EDWIN EDWARDS, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE, STATE OF MISSISSIPPI,

IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANTS _APPELLEES

INTERESTS OF AMICI CURIAE

William A. Allain is the Governor of the State of

Mississippi, Edwin Lloyd Pittman is the Attorney General,

and Dick Molpus the Secretary of State. They comprise the

Election Commission of the State of Mississippi. They have

been named as defendants in a case filed in the United

States District Court for the Southern District of

Mississippi, Martin v. Allain, Civil Action No. J84-0708(B).

Briefly, the plaintiffs in Martin have alleged, inter alia,

that the method of electing circuit, chancery and certain

county judges in Mississippi violates Section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act, as amended in 1982, 42 U.S. §1973. On

April 1, 1987 the district court in its memorandum opinion

accepted the position of the Martin plaintiffs that Section

2 of the Voting Rights Act covers judicial elections.

Martin v. Allain, 658 F Supp. 1183, 1200. The Mississippi

district court's ruling in Martin opposes the decision

reached by the Louisiana district court below. Accordingly,

the amicus curiae have a strong interest in the decision to

be rendered by the court in the instant appeal. It is

submitted that if this court affirms the decision of the

district court below that Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act

does not apply to the election of judges, it will curtail

the continuing litigation in the Martin case now before the

Mississippi district court.

STATEMENT OF CASE

The amici curiae will refer to the findings of

fact and conclusions of law contained in the memorandum

opinion of the district court below. Chishom v. Edwards,

659 F. Supp.183 (E. D. La. 1987).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act does not

contemplate the regulation of elections of state judicial

officers. They are not representatives, as the statute

specifically applies, and Congress gave no indication that

it intended to extend its scope to state judges. There are

important policy reasons that injoin the application of

statutory voting rights standards to the election of the

judiciary while representatives to the legislative or

executive branches of government seek to balance the

interests of their constituents, the judiciary must apply

-2-

the law to the individual interests before it and

irrespective of the general interests of those who elected

the judge. The judiciary must treat all litigants fairly

and impartially regardless of where they live;

representatives are to advance the interests of the district

from which they are elected. These differences are

substantive and deeply imbedded in the foundations of our

system of jurisprudence.

Amicus will not attempt to address the arguments

made by the parties in this appeal. The purpose of this is

to raise the policy issues in an historical context as some

possible aid to this court's deliberations and because of

the possible impact of this decision on the pending

litigation in Mississippi.

ARGUMENT

1. SECTION TWO OF THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT APPLIES

ONLY TO "REPRESENTATIVES", WHICH JUDGES BY

DEFINITION ARE NOT.

The amicus submits that Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act does not apply to the election of state court

judges. The plain wording of Section 2, bolstered by

analogous precedents from other areas of civil rights law

removes the judiciary from the scrutiny of the Voting Rights

Act imposed on the elections of officers in the legislative

and executive branches of government.

In undertaking the task of providing a correct

interpretation of Section 2, the court should begin by

reading the language of the statute itself. Touche Ross and

-3-

Company v. Redington 442 U.S. 560, 568, 99 S. Ct. 2479,

61 L. Ed. 2d 82. Section 2 as written in full follows:

(a) No voting qualification or

prerequisite to voting or standard,

practice, or procedure shall be imposed

or applied by any State or political

subdivision in a manner which results in

a denial or abridgment of the right of

any citizen of the United States to vote

on account of race or color, or in the

contravention of the guarantees set

forth in section 1973(f)(2), as provided

in subsection (b) of this section.

(b) A violation of subsection (a) of

this section is established if, based on

the totality of the circumstances, it is

shown that the political processes

leading to nomination or election in the

State of political subdivision are not

equally open to participation by members

of a class of citizens protected by

subsection (a) of this section in that

its members have less opportunity than

other members of the electorate to

participate' in the political process and

to elect representatives of their

choice. The extent to which members of

a protected class have been elected to

office in the State or political

subdivision is one circumstance which

may be considered: Provided, that

nothing in this section establishes a

right to have members of a protected

class elected in numbers equal to their

proportion in the population.

42 U.S.C. § 1973 (emphasis supplied).

In the language of Section 2 above, a substantial

operative term is "representatives". It is submitted that a

"representative" as ordinarily used in describing political

officials does not include state court judges. Accordingly,

since state court judges are not "representatives" of the

citizenry, the elections for judicial offices are not

covered under Section 2.

The term "representative" is not specifically

defined in the Voting Rights Act. Nor does the legislative

history present any specific attempt to define the term

"representative". As a consequence, the court must employ

recognized methods of statutory construction to arrive at a

suitable definition of "representative" under Section 2. In

construing Section 2, it should generally be assumed that

Congress expresses its purpose through the ordinary meaning

of the words its selects. Escondido Mutual Water v. La

Jolla, 466 U.S.765, 772, 104 S. Ct. 2105, 2110, 80 L. Ed'. 2d

753 (1984). Moreover, "absent a clearly expressed

legislative intention to the contrary, statutory language

must ordinary be regarded as conclusive." Consumer Products

Safety Commission v. GTE Sylvania, Inc. 447 U.S. 102, 108,

100 S. Ct.2051, 2056, 64 L. Ed. 2d 766 (1980).

In our system of government, judges simply are not

"representatives". The term "representatives" is typically

applied to elected members of legislative bodies, i.e. the

United States House of Representatives, and to elected

executive officers. Judges, on the other hand, have been

traditionally viewed as above partisan and political frays

and, therefore, generally not considered to be conducting

their duties in a representational capacity. As Sir William

Blackstone stated in his Commentaries of the Law, judges are

"the depositories of the law; the living oracles who must

-5-

decide in all cases of doubt and who are bound by an oath to

decide according to the law of the land". Consequently,

judges are not supposed to give credence to popular opinion

or the political winds of the day.

Moreover, judges are not free to make policy as

they see fit. As Blackstone said, "for it is an established

rule to abide by former precedents, where the same points

come again in litigation....[the judge] being sworn to

determine, not according to his own private judgment, but

according to the known customs and laws of the land, not

delegated to pronounce a new law, but to maintain and expand

the old one". Commentaries on the Laws of England.

(Chicago: Callaghan and Company, 1871) 1. 69-70. What

Blackstone was of course referring to is the special

responsibility of judges to follow the principle of stare

decisis. The principle of stare decisis is a unique and

overriding restriction placed on the judicial branch of

government. In a fundamental way, it prevents judges from

considering what a majority of the citizens may want in a

particular matter or what the judge personally thinks is

best. In other words, it prevents a judge from exercising a

representative function.

In our system of government, representatives are

those who can express or effectuate the will of the

citizenry and can convert that will into public policy,

programs and other forms of action. Legislators and

executive officers have broad powers in which to perform

-6-

these representatives functions. On the other hand, the

judge's powers are extremely limited. One of our founding

fathers, Alexander Hamilton, expressed it best in

Federalist, No. 78.

The executive not only dispenses honors,

but hold the sword of the community.

The legislature not only commands the

purse, but prescribes the rules by which

the duties and rights of every citizen

are to be regulated. The judiciary, on

the contrary, has no influence over

either the sword or the purse; no

direction either of the strength or of

the wealth of the society; and can take

no active resolution whatever. It may

truly be said to have neither FORCE NOR

WILL, but merely judgment.

Alexander Hamilton, Federalist, No. 78.

Unlike the legislative and executive branches of

government the judiciary cannot on its awn initiative

undertake to tackle issues of public importance. "As long,

therefore, as a law is untested, the judicial authority is

not called upon to discuss it." Alexis de Tocqueville,

Democracy in America (1835). Moreover, the judiciary

"pronounces on special cases and not upon general

principals." "...[A] characteristic of judicial power is its

inability to act unless it is appealed to, or until it has

taken cognizance of an affair.. ..the judicial power is by

its nature devoid of action; it must be put in motion in

order to produce a result." Democracy in America.

The United States Supreme Court decisions

establishing the principle of one person, one vote, e.g.,

Baker v. Carr, 369, U.S. 186, 82 S. Ct. 1691, 72 L.Ed. 2d

-7-

663(1962); Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 84 S. Ct. 1362,

12 L. Ed. 2d 506 (1964) are based upon the concept of the

rights of citizens to be fairly "represented" through the

election of public officials. These one man, one vote cases

in their application should be helpful to the Court in

reaching a resolution as to whether the term

"representative" under Section 2 should be applied to

judges. In particular, it should be noted that none of

these one man, one vote, precedents have ever been applied

by a court to the election of state judges. In fact, the

cases reported have rejected this application. For

instances, in 1964 a three judge court refused to apply the

one person, one vote doctrine of Baker v. Carr to the

election of state court judges in Georgia. Stokes v.

Fortson, 234 F. Supp. 575, 577 (N. D. of Ga. 1964). Finding

that judges were not "representatives" the court opined the

following:

The one man-one vote doctrine,

applicable as it now is to selection of

the legislative and executive, does not

extend to the judiciary. Manifestly,

judges and prosecutors are not

representatives in the same sense as are

legislators or the executive. Their

function is to administer the law, not

to espouse the cause of a particular

constituency. Moreover there is no way

to harmonize selection of these

officials on a pure population standard

with the diversity in type and number of

cases which will arise in various

localities, or with the varying

abilities of judges and prosecutors to

dispatch the business of the courts. An

effort to apply a population standard to

-8-

the judiciary would, in the end, fall on

its own weight.

Stokes v. Fortson, supra, at 577. Clearly, the Stokes

decision turned on the premise that judges are not

"representatives" when compared to legislators or executive

officers.

The court in Buchanan v. Rhodes, 249 F. Supp. 860,

865 (N.D. Ohio 1966). appeal dismissed, 385 U.S. 3 87 S. Ct.

33, 17 L. Ed. 2d 3 (1966), took the same approach as Stokes

in rejecting a one man one vote challenge to the election of

state court judges in Ohio. As in Stokes, the notion 'that

judges were not "representatives" of the people was an

important factor in the Buchanan court reaching its

resolution: "One glaring distinction between the functions

of legislators and the functions of judges: judges do not

represent people, they serve people."

On the heels of Stokes and Buchanan a district

court in New York dismissed a law suit seeking

reapportionment of judicial districts in the State of New

York, again on the theory that judges and the judiciary are

not "representatives". New York State Association of Trial

Lawyers v. Rockefeller, 267 F. Supp. 148(S.D.N.Y. 1967).

The state judiciary, unlike the

legislature, is not the organ

responsible for achieving representative

government. Nor can the direction that

state legislative districts be

substantially equal in population be

converted into a requirement that a

state distribute its judges on a per

capita basis.

-9-

* * * *

Plaintiffs' attempt to pattern judicial

apportionment after legislative

apportionment ignores the obvious truth

that the administration of a state's

judiciary, unlike the apportionment of a

legislative body, cannot be governed by

simple arithmetic.

Id. at 153 & 154.

In Wells v. Edwards, 347 F. Supp. 453, 454-55

(M.D. La. 1972) (three-judge court), aff'd mem., 409 U.S.

1095, 93 S. Ct. 904, 34 L. Ed. 2d 679 (1973), a three-judge

court held that that one-man, one-vote apportionment

doctrine did not apply to the judicial branch of government

and agreed with the statement in Buchanan that "judges do

not represent people, they serve people." The Supreme Court

affirmed. 409 U.S. 1095 (1973).

The appellants attempt to make little of these

cases above which rejected one-man, one-vote standards to

elections for judicial posts. The appellants attempt to

distinguish these cases because they were brought under the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and not

under the 15th Amendment or the Voting Rights Act. However,

it is submitted that the functional analysis and the factual

definition employed by the courts in the one-man one-vote

cases along, is a valid approach to be employed in looking •

at the term "representative" as it is used in Section 2 of

the Voting Rights Act. Thus, it is clearly established that

prior to 1982, when Congress amended Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Acts, and included the word "representative" the

-10-

case law had established the proposition that one person,

one-vote dilution analysis under the Fourteenth Amendment's

Equal Protection Clause did not apply to the election of

judges and that judges did not represent people. By using

the term "representatives in Section 2 of the Voting Rights

Act, Congress was using a term of art that had already been

employed in the one-man one vote cases. Of course, it

should be presumed by this court that when enacting new

legislation Congress is well aware of the existing law.

Director v. Perni North River Associates, 459 U.S. 297,

319-20, 103 S. Ct. 634, 648, 74 L. Ed. 2d 465, 482 (1983).

Accordingly the presumption can be made that Congress was

well aware of the prevailing Civil Rights Law as it applied

to voter dilution in one-man one-vote cases and had in mind

the previously used definition of "representatives" when it

drafted the language now found in Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act.

2. THE LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF SECTION 2 OF THE

VOTING RIGHTS ACT DOES NOT SUPPORT THE CONCLUSION

THAT IT SHOULD BE APPLIED TO JUDICIAL ELECTIONS.

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act was amended in

1982 partially in response to City of Mobile, Alabama v.

Bolden, 446 U.S 55 (1980), wherein the Supreme Court held

that Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, as it was then

written, could only be applied to voting practices adopted

or maintained for a discriminatory purpose. The U.S.

Supreme Court in Thornberg v. Gingles, 106 S. Ct. 2752

(1986) determined that the legislative purpose behind

-11-

Congress' passage of its amendment to Section 2 was "to make

clear that a violation of Section 2 could be proved by

showing discriminatory effect alone rather than having to

show discriminatory purpose and to establish as the relevant

legal standard the (results test)." Unfortunately, there is

no specific guidance in the legislative •history of the 1982

amendment to Section 2 which supplies a definition

"representatives of their choice". Nowhere in the

legislative history of the 1982 amendment is there is any

mention that judges are to be included, or excluded, from

coverage.

It has been said that the reliance on the

legislative history in divining the intent of Congress is a

step to be taken cautiously. Piper v. Chris-Craft

Industries, Inc. 430 U.S. 1, 97 S. Ct. 926, 51 L. Ed. 2d 124

(1977). Moreover, absent clearly expressed legislative

intent to the contrary, the language in the statute itself

is to be given the first consideration and that language

must ordinarily be regarded as conclusive. Consumer Product

Safety Product Commissioner v. GTE Sylvania, Inc. 447 U.S

102, 100 S. Ct. 2051, 64 L. Ed 2d 776 (1980).

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the amicus curiae

respectfully requests the Court to affirm the decision of

the district court.

Respectfully submitted,

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI

AMICUS CURIAE

Stephen J. Kirchmayer

Deputy Attorney General

Post Office Box 220

Jackson, MS 39205

601-359-3680

Hubbard T. Saunders, IV

Crosthwait, Terney & Noble

Post Office Box 2398

Jackson, Mississippi 39205

(601) 35 -5533

UI

Cup tit( ax y

Po'Office Box 22666

Jackson, Mississippi 39205

COUNSEL FOR AMICUS CURIAE

CERTIFIATE

The undersigned hereby certifies that on the date

set forth hereinafter, a true and correct copy of the above

and foregoing Brief of Amicus Curiae, State of Mississippi,

in Support of Defendants-Appellees was caused to be served

upon the following counsel of record:

THE HONORABLE WILLIAM J. GUSTE, JR., ESQUIRE

Attorney General

KENDALL L. VICK, ESQUIRE

Assistant Attorney General

EAVELYN T. BROOKS, ESQUIRE

Assistant Attorney General

Louisiana Department of Justice

234 Loyola Avenue, 7th Floor

New Orleans, Louisiana 70112

M. TRUMAN WOODWARD, JR., ESQUIRE

110 Whitney Building

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

BLAKE G. ARATA, ESQUIRE

210 St. Charles Avenue

Suite 4000

New Orleans, Louisiana 70170

A. R. CHRISTOVICH, ESQUIRE

1900 American Bank Building

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

MOISE W. DENNERY, ESQUIRE

21st Floor, Pan American Life Center

601 Poydras Street

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

WILLIAM P. QUIGLEY, ESQUIRE

631 St. Charles Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

PAMELA S. KARLAN, ESQUIRE

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

1/ 1/4# This the 0 day of December,

-14-

1987.

II