Griggs v. Duke Power Company Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Griggs v. Duke Power Company Brief for Petitioner, 1970. 573ebcd1-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0c8e2a90-f5f0-4578-b58c-8143054d73c4/griggs-v-duke-power-company-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

113 ^

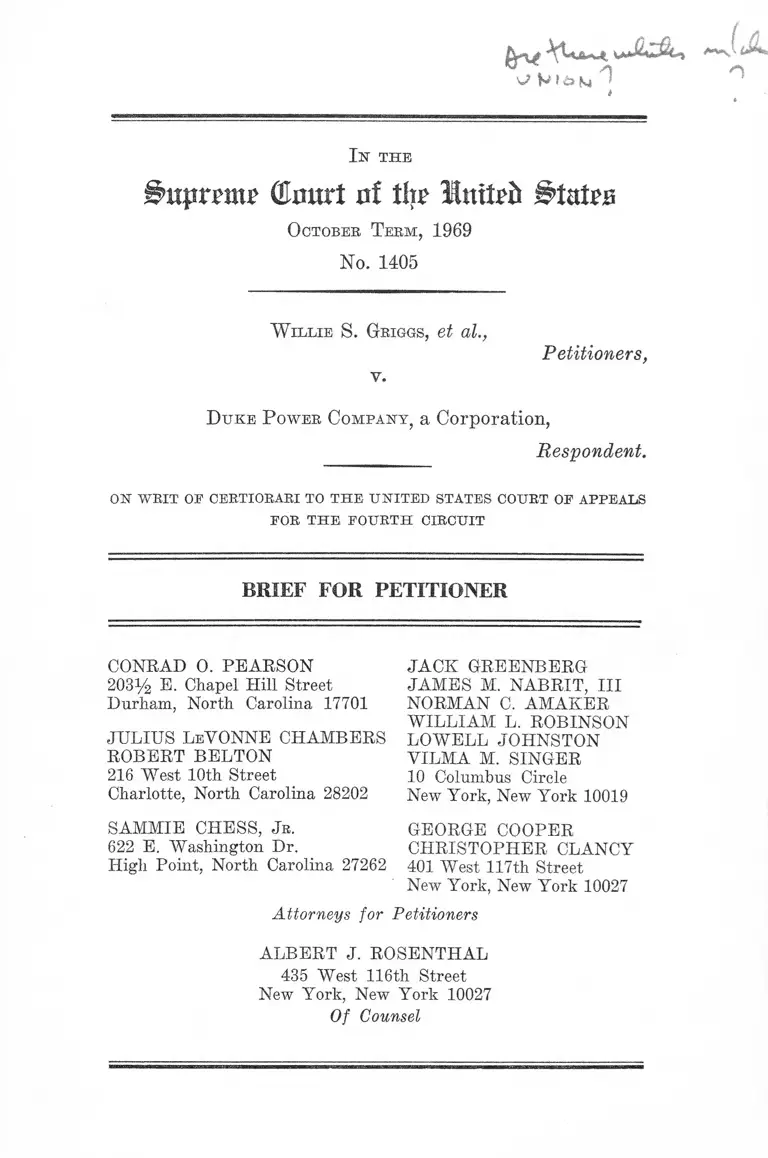

I n th e

l^upmu? (Enurt rtf tlî WnxUb &M?b

October T erm , 1969

No. 1405

W il l ie S. Griggs, et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

D u k e P ower C ompany , a Corporation,

Respondent.

ON W RIT OE CERTIORARI TO T H E U N ITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR T H E FO U R TH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN C. AMAKER

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

LOWELL JOHNSTON

VILMA M. SINGER

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

GEORGE COOPER

CHRISTOPHER CLANCY

401 West 117th Street

New York, New York 10027

Attorneys for Petitioners

ALBERT J. ROSENTHAL

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

Of Counsel

CONRAD O. PEARSON

203% E. Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina 17701

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

ROBERT BELTON

216 West 10th Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

SAMMIE CHESS, J r .

622 E. Washington Dr.

High Point, North Carolina 27262

I N D E X

Jurisdiction .................................................................... 1

Questions Presented ...................................................... 2

Statutory Provisions Involved ..................................... 2

Statement of the Case .................................................. 4

Summary of Argument ................................................ 9

A rgum ent ...................................................................... 16

PAGE

I. Title VII Requires That Tests and Diploma

Requirements Be Related to Job Performance

Needs Where Such Requirements Unequally Ex

clude Blacks Prom Employment Opportunities.

In Failing To Insist Upon Such Job Related

ness, The Decision of the Court Below Invites

Evasion of Title VII ......................................... 18

A. Tests and Diploma Requirements Have A

Vast Discriminatory Potential ................... 18

B. The Established Method of Guarding

Against Discriminatory Test and Educa

tional Requirements, While Protecting the

Reasonable Needs of an Employer, is to

Insist that Such Requirements be Related to

Job Performance Needs .............................. 22

II. The Record Below Offers No Basis for Finding

That the Diploma/Test Requirement Meets this

Job-Relatedness Standard .................................. 30

A. The Diploma/Test Requirement Clearly

Has a Prejudicial Effect on Black Workers 31

11

PAGE

B. It Cannot Be Assumed Without Supporting

Evidence That the Continuation of This

Prejudicial Requirement is Related to

Duke’s Job Performance Needs ................. 32

C. Duke Has Made No Study or Analysis or

Introduced Any Evidence At All That the

Diploma/Test Requirement is Related to Its

Job Performance Needs .............................. 39

1. The High School Diploma Requirement 41

2. The Test Requirement ............................ 44

III. Duke’s Discriminatory Practices Derive No Pro

tection Prom Section 703(h) of Title VII ........ 46

C onclusion ..................................................................................... 51

B r ie f A p p e n d ix :

Decision of EEOC, Dec. 2, 1966, CCH, Employ

ment Practices Guide, fll7,304.53 ......................Br. Ap. 1

Decision of EEOC, Dec. 6, 1966, CCH, Employ

ment Practices Guide, Tfl7,304.5 ........................Br. Ap. 3

EEOC, Guidelines on Employee Selection Proce

dures, 35 Fed. Reg. 12333 (1970) ..................... Br. Ap. 8

Mitchell, Albright & McMurray, Biracial Valida

tion of Selection Procedures in a Large South

ern Plant, in Proceedings of 76th Annual Con

vention of American Psychological Association,

Sept., 1968 ................................. ................ ..........Br. Ap. 6

Ill

T able of A utho rities

Cases:

PAGE

Arrington v. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Au

thority, 306 F.Supp. 1355 (D. Mass. 1969)..............11,24

Choate v. Caterpiller Tractor Co., 402 F.2d 357 (7th

Cir., 1968) .......... ........................................................ 16

Colbert v. H.K. Corporation, C.A. No. 11599 (N.D.

Ga. July 6, 1970) (appeal noticed August 3, 1970).... 24

Dobbins v. Local 212, IBEW, 292 F.Supp. 413 (S.D.

Ohio 1968) .................................................................24,26

Fawcus Machine Co. v. United States, 282 U.S. 375

(1931) ................................ ........ ................................. 29

FTC v. Colgate Palmolive Co., 380 U.S. 374 (1965)..... 29

FTC v. Mandel Bros., 359 U.S. 385 (1959)................. 29

Gaston County, North Carolina v. United States, 395

U.S. 285 (1969) .......... ...............................................11, 21

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960)................ . 25

Gregory v. Litton System, Inc., —— F.Supp.------; 63

Lab. Cas. 1J9485 (C.D. Calif. July 28, 1970).............. 27

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 420 F.2d 1225 (4th Cir.

1970) ............................................................ ........17,27,28

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 292 F.Supp. 243 (M.D.

N.C. 1968) ............................................................... 5

Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347 (1915) .................. 25

Hansen v. Hobson, 269 F.Supp. 401 (D.D.C. 1967)....... 34

Lane v. "Wilson, 307 U.S. 268 (1938)............................ 25

Local 53, International Assoc, of Heat & Frost Insula

tors and Asbestos Workers v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047

(5th Cir., 1969) ............................................................ 26

PAGE

Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers v.

United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir., 1969), cert.

denied, 397 U.S. 919 (1970) ................................16,26,

Louisiana Financial Assistance Comm’n v. Poindexter,

389 U.S. 571 (1968), affirming 275 F.Supp. 833 (E.D.

La. 1967) ....................................................................

Miller v. International Paper Co., 408 F.2d 283 (5th

Cir. 1969) ....................................................................

Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., -----

F.Supp. — , 60 Lab. Cas. U9297 (W.D. Ark. 1969)

(appeal noticed, 8th Cir., No. 1969) ................. .......24,

Penn v. Stumpf, 308 F.Supp. 1283 (N.D. Calif. 1970)....

Porcelli v. Titus, 302 F.Supp. 726 (N.D.J. 1969) ...........

Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 279 F.Supp. 505 (E.D.

Va. 1968) .................................................. ..................

Ranjel v. City of Lansing, 293 F.Supp. 301 (W.D.

Mich. 1969) ................................ ................................

Robinson v. Lorillard Co., 62 Lab. Cas. 1J9423 (N.I).

N.C. 1970) ...................................................................

Udall v. Tallman, 380 U.S. 1 (1965) ....................... .....

United States v. American Trucking Assn., 310 U.S.

534 (1940) .....................................................................

United States v. Hays Int’l Corp., 415 F.2d 1038 (5th

Cir. 1969) ........ ............................................................

United States v. H.K. Porter Co., 296 F.Supp. 40

(N.D. Ala. 1968) (appeal noticed, 5th Cir., No.

17703) .................................................................... 24,

United States v. Public Utilities Comm., 345 U.S. 295

(1953) ................................................................. .........

United States v. Sheetmetal Workers, Local 36, 416

F.2d 123 (8th Cir., 1969) ....................................16, 24,

28

25

16

30

24

24

26

18

16

29

29

26

26

29

26

V

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) ......................................................... 1

42 U.S.C. §2G00e et seq., Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 ................................................................... 2, 3

Section 703(a) (1), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a) (1)........ 18

Section 703(a) (2), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a) (2)........ 28

Section 703(c)(2), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(c) (2)........ 28

Section 703(f), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(f) ................. 50

Section 703(g), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(g)................... 50

Section 703(h), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(h)...... 28, 46, 48, 50

Section 706(g), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g)................... 28

Federal Regulations on Testing:

EEOC, Guidelines on Employment Testing Procedures

(1966) ................................. 22,47

EEOC, Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures,

35 Fed. Reg. 12333 (August 1, 1970) ............20, 23, 30, 35

U.S. Department of Labor, Validation of Employment

Test by Contractors and Subcontractors Subject to

the Provisions of Executive Order No. 11246, 33 Fed.

Reg. 14391 (1968) .................................................... 21,35

Other Authorities:

110 Cong. Rec. 9024-42 (1964) .................................... 49

110 Cong. Rec. 13492 (1964) ......................................... 49

110 Cong. Rec. 13503-05 (1964) ........................... 49-50

110 Cong. Rec. 13724 (1964) .......................................... 50

PAGE

VI

PAGE

88th Cong., 1st Sess. 2-3, H.R. Rep. No. 570 (1963) .... 18

88th Cong., 1st Sess. 138-41, H.R. Rep. No. 914 (1963) 18

88th Cong., 1st Sess., Hearings on Equal Employment

Opportunity before the Subcomm. on Employment

& Manpower of the Senate Comm, on Labor & Public

Welfare (1963) ............................................... ........... 18

88th Cong., 1st Sess., Hearings on Equal Employment

Opportunity before the General Subcom. on Labor

of the House Comm, on Education & Law (1963) ..... 18

Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment and Earnings,

Table A-3 Unemployment Indicators, June 1970 ...... 28

Blumrosen, Seniority and Equal Employment Op

portunity: A Glimmer of Hope, 23 Rutgers L. Rev.

268 (1969) ........... .................................................... 28

California, Pair Employment Practices, Equal Good

Employment Practices, in CCH Employment Prac

tices Guide 1(20,861 ................................. .................... 23

Coleman, J., Equality of Education Opportunity (1966) 19

Colorado Civil Rights Commission Policy Statement on

the Use of Psychological Tests, in CCH, Employ

ment Practices Guide 1(21,060 ......... 23

Cooper & Sobol, Seniority and Testing Under Fair Em

ployment Laws, 82 Harv. L. Rev. 1598 (1969) ....19, 27, 28

1 Cronbach, Essentials of Psychological Testing (2d ed.

1960) ................................................. 36

Education and Jobs: The Great Train Robbery (1970),

summarized in Berg, Rich Man’s Qualifications for

Poor Man’s Jobs, Trans-Action, Mar. 1969 ............... 37

EEOC Decision No. 70-630, Case No. AT 68-3-824E

(Mar. 17, 1970), in CCH, Fair Employment Practices

Guide 1(6136 ........................... 30

vn

EEOC Decision No. 70-501, YAT-633 (Jan. 29, 1970),

in CCH, Fair Employment Practices Guide H6112 .... 30

EEOC Decision Case No. N06809-327E (June 18,1969),

in CCH, Pair Employment Practices Guide H8516 .... 22

EEOC Decision 70-552 (Feb. 19, 1970), in CCH, Fair

Employment Practices Guide H4239 .......................22, 30

EEOC Decision (Dec. 6, 1966), in CCH, Employment

Practices Guide, *117,301.58 ....................................... 22, 23

EEOC Decision (Dec. 2, 1966), in CCH, Employment

Practices Guide, TT17,304.54 ....................................... 19, 22

Freeman, Theory and Practice of Psychological Test

ing (3rd ed. 1962) ........................................................ 36

Ghiselli and Brown, Personnel and Industrial Psy

chology (1955) ................... - ....................................... 36

Ghiselli, E., The Generalization of Validity, 12 Person

nel Psychology 397 (1959) ................... ........... .......... 34

Ghiselli, E., The Validity of Occupations Aptitude

Tests (1966) ...................... ...... ......................... ..... ....32,33

PAGE

Hearings before the United States Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission on Discrimination in White

Collar Employment, New York City, Jan. 15-18, 1968 38

Kirkpatrick, J., et al., Testing and Fair Employment

(1968) .......................................................................... 19

Lawshe and Balma, Principles of Personnel Testing

(2nd ed. 1966) ............................................................. 36

Mitchell, Albright & McMurry, Biraeial Validation of

Selection Procedures in Large Southern Plant, in

Proceedings of 76th Annual Convention of the Ameri

can Psychological Association, Sept. 1968 ............. 32

V l l l

Motorola Decision, reprinted in 110 Cong. Rec. 9030-

9033 (1964) .......................... .................. .................... 49

Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission, Affirma

tive Action Guidelines for Employment Testing’, in

CCH, Employment Practices Guide U17,195 ....... . 23

Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil

Disorders (Bantam ed. 1968) ....................................19, 28

Ruch, Psychology and Life (5th ed. 1958) ................. 36

Science Research Assoc., Inc., A Subsidiary of IBM,

Business And Industrial Education Catalog (1968-

69) ................................................................................ 35

Siegel, Industrial Psychology (1962) .............................. 36

Super and Crites, Appraising Vocational Fitness (Rev.

ed. 1962) ...................................................................... 33

Thorndike, Personnel Selection Tests and Measurement

Techniques (1949) ...................................................... 36

Tiffin and McCormick, Industrial Psychology 119 (5th

ed. 1965) ................................................. 36

U.S. Bureau of the Census, U.S. Census of Population:

1960, Vol. 1, Part 35, Table 47, p. 167......................... 20

Wall St. J., Feb. 9, 1965, at 1, Col. 6 ............................ 21

Wonderlic Personnel Test Manual 2 (1961) ................ 37

PAGE

In t h e

(Eourt at tip? Mnitrii £?iaipa

O ctober T erm , 1969

No. 1405

W il l ie S. Griggs, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

D u k e P ower C ompany , a Corporation,

Respondent.

ON W R IT OF CERTIORARI TO T H E U N ITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE, FO U R TH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

O pinions Below

The opinion of the Court of Appeals and accompanying

dissent of Judge Sobeloff is reported at 420 F.2d 1225

(1970). The opinion of the District Court for the Middle

District of North Carolina is reported at 292 F. Supp. 243

(1968). All opinions are reprinted in the Appendix.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit was entered January 9, 1970 and petition for a writ

of certiorari was filed in this Court on April 9, 1969 and

was granted on June 29, 1970. This Court’s jurisdiction

rests on 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

2

Questions Presented

Whether the intentional use of psychological tests and

related formal educational requirements as employment

criteria violates the race discrimination prohibition of

Title VII, Civil Eights Act of 1964, where:

(1) the particular tests and standards used exclude Ne

groes at a high rate while having a relatively minor

effect in excluding whites, and

(2) these tests and standards are not related to the em

ployer’s jobs.

Statutory Provisions Involved

jT

K

United States Code, Title 42:

§ 2000e-2(a) [703(a) of Civil Rights Act of 1964]

(a) It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an

employer—

(1) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any indi

vidual, or otherwise to discriminate against any

individual with respect to his compensation, terms,

conditions, or privileges of employment, because of

such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or na

tional origin; or /"'"'X

I

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify brs\<miployees in any

way whicFi would depVWe^or to deprive any

individual of ' employment op^rtunitieT'oTTther-

wise x d v e r s e l O ^ Tm^status as an employee,

because, ofjsnch individual’s race, color, religion, sex,

or national origin.

3

§ 2000e-2(h) [§ 703(h) of Civil Rights Act of 1964]

(h) Notwithstanding any other provision of this title,

it shall not be an unlawful employment practice for

an employer to apply different standards of com

pensation, or different terms, conditions, or priv-

, f ileges of employment pursuant to a bona fide senior-

J i£ ~ i^ A tta d l^ te m , or a system which measures

earnings by quantity or quality of production or to

employees who work in different locations, provided

that such differences are not the result 01 an inten

tion to discriminate because of race, color, religion,

sex, or national origin, nor shall it be an unlawful

employment practice for an employer to give and to

act upon the results of any professionally developed

ability tejjt provided that such test, its admimstra-

tion or action upon the results is not designed, in-

tended or used to discriminate because of race, color,

religion, sex or national origin. It shall not be an un

lawful employment practice under this title for any

employer to differentiate upon the basis of sex in

determining the amount of the wages or compensa

tion paid or to be paid to employees of such em

ployer if such differentiation is authorized by the

provisions of section 6(d) of the Fair Labor Stan

dards Act of 1938, as amended (29 U.S.C. 206(d)).

§2000e-5(g) [§ 706(g) of Civil Rights Act of 1964]

(g) If the court finds that the respondent has inten

tionally engaged in or is intentionally engaging in

an unlawful employment practice charged in the

complaint, the court may enjoin the respondent from

engaging in such unlawful employment practice,

and order such affirmative action as may be appro

priate, which may include reinstatement or hiring

4

of employees, with or without back pay (payable

by the employer, employment agency, or labor or

ganization, as the case may be, responsible for the

unlawful employment practice). Interim earnings

or amounts earnable with reasonable diligence by

the person or persons discriminated against shall

operate to reduce the back pay otherwise allowable.

No order of the court shall require the admission or

reinstatement of an individual as a member of a

union or the hiring, reinstatement, or promotion of

an individual as an employee, or the payment to

him of any back pay, if such individual was refused

admission, suspended, or expelled or was refused

employment or advancement or was suspended or

discharged for any reason other than discrimination

on account of race, color, religion, sex or national

origin or in violation of section 704(a).

against their employer, the Duke Power Company (herein

after Duke). The petitioners claim that various aspects

of Duke’s promotional policies effectively deny them equal

opportunity to jobs above the laborer category. The action

was commenced following proceedings before the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission (hereinafter some

times “EEOC”) in which reasonable cause was found to

believe that the company was engaging in gross practices

of racial discrimination (A. 2b-4b).

All the petitioners are employed at Duke’s Dan River

Steam Station, a power generating facility located at

Draper, North Carolina (A. 55a). The employees at this

Statement o f the Case

This is a class action under Ti

Act of 1964 brought by a group o:

the Civil Rights

imbent black workers

5

plant are divided into five departments: Operations, Main

tenance, Laboratory and Test, Coal Handling, and Labor.

(Because employees in all departments except Coal Han

dling and Labor work inside the plant these other depart

ments will be referred to collectively as the “inside” depart

ments).1 n / o A a'

Black workers have been employed at this plant for a

number of years. There are now 14 blacks out of 95 total

employees (A. 19b). However, these blacks have been

tightly controlled. The District Court found,

“at some time prior to July 2, 1965, Negroes were rele-

gated J ^ J h e J L la te 'F lD J egarEneiff and prevented

"access to other, departments by reason of their race.”

(A. 32a).

( <

As might be expected, the Labor Department is the least

desirable one in the plant and is the lowest paid. Moreover,

blacks have even been denied the better paying jobs in that

department. The maximum wage ever earned by a black

worker in the Labor Department, including some with al

most 20 years seniority, is $1.645 per hour (A. 109b). This

maximum is less than the minimum ($1,875) paid to any

white in the plant (A. 105b-108b). It is drastically less than

the wages paid to whites with comparable seniority in the

other departments where top jobs pay $3.18 or more per

hour (A. 72b).2

The first breach in this practice of relegating black work

ers to low level positions in the Labor Department did not

occur until August 6, 1966 (more than a year after the July

2, 1965 effective date of Title VII) when a black laborer

1 There are also a few non-departmental jobs at the plant, all

of which are located inside except the watchmen (A. 58a).

2 These pay scales are based on 1967 data in the record; but

the same disparity continues to exist today.

6

with a high school diploma and almost 13,.yjears of seniority

was promoted to a “learner” position in the Coal Handling

Department paying $1.95 per honr (A. 83b, 109b, 126b).

At, this time, whites with similar seniority and less educa-

lSon were eSrHiJig' 126b).

By the time of trial, Duke had apparently relented from

its formal practice of restricting all black workers to low

level jobs in the Labor Department. However, the effect of

that practice was largely maintained by a company policy

precluding anyone ..from transferring to Coal Handling or

J-p oae.oi.the"inside denartment&JMilfigs he erffier (1) had a

high school diploma, or (2) achieved a particular score on

each of two quickie “intelligence” tests—the 12-minute

Wonderlic Test and the 30-minute Bennet (sometimes re

ferred to as the “Mechanical AA”) (A. 20b-22b). Only 3

or 4 of the 14 black workers at Dan River could satisfy

these requirements.3 The other 10 or 11 black workers were

destined to a permanent low paid laborer status.

In contrast to its effect on black workers, these high

school and test requirements had no application to anyone

already in the Coal Handling Department or an inside de

partment, either as a requirement for maintaining his

present position within his departmental area (A. 102a)

or for securing promotion to jobs paying $3.18 per hour

or more (A. 72b). All of the white workers in the plant were

in these better departments.

3 Three of the black workers had high school diplomas (A. 109b,

126b). The Court of Appeals found that a fourth black worker,

Willie Boyd, had acquired an equivalency diploma which the com

pany would accept in lieu of the regular diploma. Willie Boyd’s

status is not entirely clear on the record. However the situation

as to him was mooted by the partial relief granted in the Court

of Appeals. See pp. 7-8, infra.

7

Thus, for example, Clarence M, Jackson, a "black with

7th grade education hired in 1951 as a laborer, remained

one in 1967 (at $1,645 per hour) and was unable to transfer

to a better job (A. 109b). By contrast, Jack O’Dell, a white

with 5th grade education, hired in 1951 as a helper, had

gained promotion to Coal Handling Operator by 1967 (at

$2.79 per hour) (A. 106b-126b). Jady Martin, a white with

7th grade education hired in 1956 as a helper, had worked

his way to Mechanic “B” in 1965 and was able to gain pro

motion to Mechanic “A” in 1966 (at $3.41 per hour) (A.

106b-126b). Rollins, a white with 7th grade education, is

the labor foreman; he is responsible for supervising blacks,

several of whom have more formal education. Neither

O’Dell, Rollins nor Martin was ever called upon to take a

test.

rN.nl The first of Duke’s transfer requirements (high school

\Jr J ' diplomSr)“had been in effect for a number of years "prior "to

tins" action (A. 20b). The second (passing a test battery)

"") was newly adopted in September, 1965, in response to a

request from a number of white non-high school graduates

'%S / in the Coal Handling Department who wanted an alterna-

>|̂ V tive chance for promotion to inside jobs (A. 85a-87a). Both

c ~A # requirements were challenged by petitioners on the grounds

^ ! th a t j l) they imposed a special burden on black employees

.at Dan River not similarIy~fi^osM'.dnTwliHe'employees.

and (2) even if similarly imposed that they cnnstituted dis-

criminatory requirements which are not related to the job

npeds of Duke. ^

\ i A

\ IThe District Court denied relief on either ground. The

f V w Court oJ3^ea^Jb^»w^mj^aqcegted petitioners’ claim that

\ ‘̂ ^requirem ents were not_similarlyH&posh<3 insofar as

Elites hired prior Jo either requirement were free to be

^omoted without ever jgom^y^g wMS c^ex^ranS ously

jk / TimeRblachs were not T h rc o T ^ p ro p e r ly ^ e ^ M .'B a ^ 'A

- hired prior_ln. either requirement must be given the same

promotional opportunities as..contemporaneously hired

whites—i.e., freed of the burden of either having- a diploma

or passing a test. This aspect of the Court of Appeals deci-

sion, on which Supreme Court review has not been sought,

provided full relief to 7 of the 11 black workers who could

not meet the diploma/test requirement. The problem of the

remaining 4 blacks, as to whom the Court of Appeals de

nied relief with Judge Sobeloff dissenting, is now before

I this Court.

M These four black workers were hired between

h av a^ ^ plant since then (A.

^ 109b). Their formal educations range from "3pTgradeTb

10th grade, and one has also received special training in

auto mechanics’ school (A. 126b). All four are in laborer

positions paying $1.53 to $1,645 per hour (A. 109b). Duke

has conceded TKaF^eseTaEorers might perform well in

better paid departments such as Coal Handling, if given

the chance (A. 124b); and that many of the black laborers

have worked with the Coal Handling Department for many

years and thereby gained experience and familiarity with

the operations of the department (A. 106a, 124b). The

company’s job descriptions prepared in connection with this

case indicate that the functions of Coal Handling employees

are similar in many respects to those of laborers (A. 48b-

49b, 65b-66b). However, Duke has made no attempt to

assess the job performance, work experience or other quali

fications of these four longtime laborer employees to assess

their potential for advancement (A. 104a).

Bather, the sole reason given for freezing them in the

labor category is their failure to meet the diploma/test

requirement. This requirement has no sound basis in fact

or experience. It was adopted without any study, evalua

tion or analysis of either the abilities needed on the jobs

9

or the qualities measured by the requirement (A. 93a, 103a-

104a, 19b, 57b-71b, 85a-86a, 115b-116b, 199a-200a). The

Wonderlie test in particular has a heavy cultural orienta

tion seemingly unrelated to most job functions at the plant

(A. 101b).

Summary o f Argument

This is the first Title VII race discrimination case to come

before this Court on the merits. It follows five years of

experience under this landmark remedial statute during

which lower courts have generally sought to give it a broad

and flexible interpretation. This case thus presents the

Court with the first opportunity to affirm or reject the

general course taken by the great majority of lower courts

and will fundamentally affect the future direction of litiga

tion under the Act.

I.

TITLE VII REQUIRES THAT TESTS AND DI

PLOMA REQUIREMENTS BE RELATED TO JOB

PERFORMANCE NEEDS WHERE SUCH REQUIRE

MENTS UNEQUALLY EXCLUDE BLACKS FROM

EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITIES. IN FAILING! TO

INSIST UPON SUCH JOB RELATEDNESS, THE DE

CISION OF THE COURT BELOW INVITES EVASION

OF TITLE VII.

A. Tests and Diploma Requirements Have a Vast

Discriminatory Potential.

Petitioners challenge here the use of the diploma/test

requirement as prerequisites for jobs where such require

ment unequally excludes blacks from employment oppor

tunities and is not related to job performance. Petitioners

contend that Title VII requires that the diploma/test

requirement be related to job performance where such re-

10

quirement unequally excludes blacks from employment op

portunities.

Title VII, potentially a remedial milestone in civil rights

legislation, bars not only outright refusals to hire blacks;

but it also makes unlawful subtle or superficially neutral

forms of racial discrimination in employment. “Objective”

criteria such as the diploma/test requirement is a potent

tool for reducing black employment opportunities, to the

extent of frequently excluding blacks. In one typical case,

the EEOC has found that a battery of tests (including the

Wonderlic and Bennett used by Duke Power) excluded a

disproportionate number of Negroes. Similarly, the Com

mission has found, confirmed by various studies, a great

racial disparity in test scores and receipt of a high school

diploma.

The gross differences between test scores achieved by

blacks and whites are directly attributable to race because of

the differences in education because of segregated schools

and differences in cultural environments. This is largely

true today and overwhelmingly true for petitioners who

completed their education before Brown began its erosion

of the pervasive practices of segregation and discrimina

tion. Such discrimination on the basis of education and

test taking ability was well recognized by this Court in

Gaston County, North Carolina v. United States, 395 U.S.

285 (1969).

The facts regarding the disparity between black/white

educational opportunities make a salient point. If require

ments such as passage of “intelligence” tests and a high

school diploma could be imposed without regard to job

relatedness almost every employer in the South could

create a substantial and unjustifiable job preference in

favor of whites. This possibility is particularly under-

11

scored by the increased use of tests since the passage of

Title VII.

B. The Established Method of Guarding Against

Discriminatory Test and Educational Require

ments, While Protecting the Reasonable Needs

of an Employer, Is to Insist That Such Require

ments Be Related to Job Performance Needs.

The established method of guarding against discrimina

tory test and educational requirements while protecting the

reasonable needs of an employer is to insist that such re

quirements be related to job performance needs. This

means that the tests and educational requirements must

fairly measure the knowledge of skills required by the par

ticular job which the applicant seeks. Both the Equal Em

ployment Opportunity Commission and the office of Fed

eral Contract Compliance require that test and educational

requirements be job related. Several United States District

Courts have issued decisions in accord with the view of

EEOC and OFCC, notably Arrington v. Massachusetts

Bay Transportation Authority, 306 F. Supp. 1355 (D. Mass.

1969).

In looking to job relatedness as the touchstone of the

fair use of test and educational requirements, the courts,

federal and state employment agencies are merely carry

ing forward a Title VII principle established in a series of

cases challenging other unlawful employment requirements,

which though objective in form have the effect of system

atically reducing Negro job opportunity. For example,

courts have struck down nepotic and seniority rules which

although adopted for nmTracTaf reasons had a racially dis

criminatory effect and were not job related.

The rationale of the job relatedness doctrine is clear.

If a test, education (or other objective requirement) is job

12

related, employees are hired or promoted on the basis

of their ability to perform, which is fair. But where a test

or educational requirement is not job related, hiring and

promotion is done on the basis of educational and cultural

background which given the facts about schooling, housing

and other factors affected by race is only thinly veiled

racial discrimination.

By failing to insist on a reasonable relationship be

tween the diploma/test requirement and job performance

needs, both the Court of Appeals and the District Court

have rejected the established standard for preventing un

fair use of test and educational requirements—job related

ness—and have opened the door to evasion of Title VII.

This Court should reverse and adopt the job relatedness

standard.

II.

THE RECORD BELOW OFFERS NO BASIS FOR

FINDING THAT THE DIPLOMA/TEST REQUIRE

MENT MEETS A JOB RELATEDNESS STANDARD.

The method of determining whether a diploma/test re

quirement is reasonably related to job performance needs

will vary from case to case. Many factors will influence this

determination, including the extent to which the require

ment is prejudicing black workers. The diploma/test re

quirement used in the instant case is clearly one which has t

a serious prejudicial effect on black workers. The record j

in this case is devoid of any meaningful showing by Duke j

that this requirement is related to job performance needs, i

If the court below had made any inquiry beyond merely

looking for an affirmative showing of racial animus, the

practice of the respondent would have been found to be

unlawful.

13

A. The Diploma,/Test Requirement Clearly Has a

Prejudicial Effect on Black Workers.

In addition to general statistics which firmly establishes

the prejudicial effect of the Duke’s diploma/test, require

ment the effect of this requirement can he seen in the

specific impact on black workers at Duke, j The only persons

burdened by this requirement are the four black petitioners

Tere* involved; they are frozen

partment where the top pay is $1,895 per hour.»All of the

“white workers are in departments with promotional ex

pectancies leading to substantially higher pay levels

B. It Cannot Be Assumed Without Supporting Evidence

That the Continuation of This Prejudicial Require

ment Is Related to Its Job Performance Needs.

It has been demonstrated in dozens of studies that there

is commonly little or no relationship between test scores

and job performance. Aptitude tests may predict academic

performance rather well. But industrial testing involves a

range of skills and abilities entirely divorced from a pristine

test room setting. Because of the frequency with which tests

show little or no relation to job performance, it cannot be

assumed in any particular case that a test is making a use

ful prediction without supporting evidence. In view of the

low validity and reliability of tests and education require

ments in assessing job performance abilities, no require

ment that grossly prefers whites over Negroes can be as

sumed to be based on job performance unless supported by

proper study and evaluation. Absent such study and evalu

ation, the use of these requirements constitutes an un

justified exclusion of Negroes in violation of Title VII.

14

C. Duke Has Made No Study or Analysis or Introduced

Any Evidence at All That the Diploma/Test Require

ment Is Related to Its Job Performance Needs.

The record in this case shows that Duke’s diploma/test

requirement is not based on business needs and was adopted

without proper study and evaluation. This case does not

involve persons unknown to Duke; it involves only four

persons, each of whom has worked i(m Duku-lox at.least-

~seveiT~years7j~'The Company is equipped to evaluate not

only the general reliability and performance of these men,

but also their specific abilities to learn and perform in other

jobs. Indeed, Duke concedes that these men might perform

well if given a chance. A lack of the need for the diploma/

test requirement is clearly demonstrated by the readiness

of Duke to permit present white employees in the better

departments to stay and be promoted without meeting this

requirement. In face of the undisputed evidence that the

diploma/test requirement is not essential and data showing

the serious racially prejudicial effect on black workers,

Duke’s persistence in maintaining this requirement is but

a feeble attempt at rationalization for the continuation of

this practice.

1. The High School Diploma Requirement—Company of

ficials testified that this requirement was adopted without

study or evaluation and without any particular evidence

that it would serve the employment needs of Duke. It was

adopted on the basis of what can be charitably described

as blind hope. If Duke is permitted to adopt a high school

diploma requirement on the flimsy basis set out on this

record any employer in the country would also be abso

lutely free to adopt such a requirement or some other

educational requirement which would have the same effect

of grossly preferring whites over Negroes.

15

2. The Test Requirement—The situation regarding the

tests is even less justifiable than that regarding the high

school diploma requirement. This requirement was adopted

to protect a group of white employees in Coal Handling

from the burdens of the high school diploma requirement.

As in the case of the high school diploma requirement it

was adopted without study, evaluation or analysis. At

tempts by Duke at relating test scores to job success have

been unsuccessful. Its only justification is as a substitute

for the high school requirement and if that falls the test

requirement must fall.

III.

DUKE’S DISCRIMINATORY PRACTICES DERIVE

NO PROTECTION PROM SECTION 703(h) OF TITLE

VII.

Section 703(h) provides that an employer may rely upon

a “professionally developed ability test” which is “not

designed, intended or used to discriminate.” This provi

sion applies only to tests.

whatsoever to the high school diploma requirement which

clearly violates Title VII for the reasons set out above.

While section 703(h) could have relevance to the test re

quirement, it does not apply because Duke’s tests are, not

“professionally developed” within the meaning..of the

Vtatiiter.are'’'‘fihtended” to discriminate. and are being

"“used” to discriminate even if not so intended.

16

ARGUMENT

This is the first Title VII race discrimination case to

come before this Court on the merits. It follows five years

of experience under this landmark statute during which

courts have been enlightened and perceptive in giving it a

broad and flexible interpretation.4 This judicial approach

is consistent with the remedial role which Title VII was

designed to play in countering employment discrimination.

It has given Title VII the potential for becoming an effec

tive force for fair employment in contrast to the many

state fair employment laws which languished under re

strictive applications. This case thus presents the Court

with the first opportunity to affirm or reject an important

general course which the lower courts have taken. The

decision in this case will therefore fundamentally deter

mine the future direction of Federal fair employment law.

Judge Sobeloff eloquently stated this point in his dissent

below:

“This decision we make today is likely to be as

persuasive in its effect as any we have been called

upon to make in recent years.

# # #

This case presents the broad question of the use of

allegedly objective employment criteria resulting in

the denial to Negroes of jobs for which they are poten-

4 See, e.g., Local 189, Papermakers and Paperworkers v. United

States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 397 U.S. 919

(1970) ; United States v. Sheet Metal Workers, 416 F.2d 123 (8th

Cir. 1969) ; Miller v. International Paper Co., 408 F.2d 283 (5th

Cir. 1969) ; Choate v. Ca,terpiller Tractor Co., 402 F.2d 357 (7th

Cir. 1968) ; Robinson v. Lorillard Co., 62 Lab. Cas. 9423 (M.D.N.C.

1970).

17

tially qualified. . . . On this issue hangs the vitality

of the employment provisions (Title VII) of the. 1964

Civil Rights Act: whether The Act shall remain a

potent tool for equalisation of employment opportunity

or shall he reduced to mellifluous but hollow rhetoric

420 F.2d at 1237 (Emphasis added.)

The decisions of the Court of Appeals and the District

Court interpret Title VII so as to offer virtually no protec

tion against such arbitrary use of diploma/test require

ments, even where, as in this case, the requirements are

of such nature as to have a discriminatory impact on black

workers. Petitioners contend that this interpretation of

Title YII is unnecessarily narrow and that it led the courts

below to sustain a practice which would have been found

unlawful under a proper interpretation of Title VII.

18

I.

Title VII Requires That Tests and Diplom a Require

ments Be Related to Job Perform ance Needs W here Such

Requirements Unequally Exclude Blacks From Em ploy

m ent Opportunities. In Failing to Insist Upon Such

Job Relatedness, the D ecision o f the Court Below Invites

Evasion o f Title VII.

A. Tests and Diploma Requirements Have a Vast

Discriminatory Potential.

Title VII was a legislative milestone6 designed to be a

powerful force in alleviating the oppressed employment

situation of black workers.6 As such it was framed in broad

terms, barring not only outright refusals to hire blacks,

but also making it unlawful “otherwise to discriminate

against any individual with respect to his compensation,

terms, conditions or privileges of employment,” 7 or to

“classify . . . employees in any way which would, tend to

deprive "any' l^Sividnal of emplQyment.-npport.unitias or

_ otherwise adversely affect his status,,.as, an employee,” 8

because of race. With this sweeping language Congress

made it clear that Title VII was to reach all deterrents

to full black employment opportunity.

6 Ranjel v. City of Lansing, 293 F. Supp. 301, 309 (D. Mich.

1969).

6 See, e.g., H.R. Rep. No. 570, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. 2-3 (1963) ;

H.R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. 138-41 (1963) (concurring

report of Congressman McCulloch and others) ; Hearings on Equal

Employment Opportunity before the General Subeomm. on Labor

of the House Comm, on Education & Labor, 88th Cong., 1st Sess.

passim, (1963) ; Hearings on Equal Employment Opportunity be

fore the Subeomm. on Employment & Manpower of the Senate

Comm, on Labor & Public Welfare, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. passim

(1963).

7 Section 703(a)(1), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(a) (1).

8 Section 703(a)(2), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(a) (2).

19

There is no doubt that “objective” criteria, such as tests

and educational requirements, are potent tools for substan

tially reducing black job opportunities, often to the extent

of wholly excluding blacks. The National Advisory Com

mission on Civil Disorders (the Kerner Commission) put

it bluntly:

“Racial discrimination and unrealistic and unnecessarily

high minimum, qualifications for employment or promo

tion often have the same prejudicial effect.” 9

In one typical case, the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission found that use of a battery of tests, including

the Wonderlic and Bennett tests used by Duke Power

Company, resulted inJIg% of whites passing the tests but

only 6% of blacks.10 11 The EEOC' has recently ruled:

| JTt is now well settled that the use of the Wonderlic, /

^Bennett and certain other preemployment tests result in ‘

reject ion of a disproportionate number of Negro job ap

plicants.” ii flooH"of otlier' studies confirm a great racial

disparity in test scores, especially in the South where the

disparity in educational opportunity has been the greatest.12

9 Commission Report at 416 (Bantam Books ed. 1968).

10 Decision of EEOC, Dee. 2, 1966, reprinted at p. Br. Ap. 1,

infra.

11 EEOC decision 70-552 (Feb. 19, 1970) in CCH Fair Emp.

Prac. Guide j[6139.

12 See J. Kirkpatrick, et al., Testing and Fair Employment 5

(1968) ; J. Coleman, Equality of Educational Opportunity 219-20

(1966) ; authorities collected in Cooper & Sobol, Seniority and

Testing under Fair Employment Laws, 82 Harv. L. Rev. 1598,

163,9-41 nn. 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17.

The Wonderlic test is a mixture of questions on vocabulary,

mathematics, and other subjects, with a heavy emphasis on vocab

ulary and reading ability. A testee is expected to answer questions

such a.s:

“No. 11. ADOPT ADEPT—Do these words have

1. Similar meanings,

2. Contradictory,

20

The same disparate effect also results in the South when

a high school diploma requirement is imposed. As of the

last census, only 12% of North Carolina Negro males had

completed high school, as compared to 34% of North

Carolina white males.13

These gross differences between blacks and whites are

directly traceable to race. The petitioners, who were born

black, received a different education in segregated schools

and grew up in a different cultural environment than they

would have had they been born white. They were forced

to drop out of school earlier because of economic necessity

produced by discrimination and because discrimination led

them to conclude that they could not make use of further

education. These facts are largely true even for the Negro

child born today. They are overwhelmingly true for peti-

3. Mean neither same nor opposite?”

“No. 19. REFLECT REFLEX—Do these words have

1. Similar meanings,

2. Contradictory,

3. Mean neither same nor opposite?”

“No. 24. The hours of daylight and darkness in September are

nearest equal to the hours of daylight in

1. June

2. March

3. May

4. November”

(See A. 101b-103b) The ability to answer such questions is ob

viously related to formal schooling and cultural background. The

vocabulary questions call for an appreciation of subtle differences

in word meanings and parts of speech; the question of hours of

daylight cannot be answered reliably without knowledge of the

vernal equinox.

13 EEOC Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures, 35 Fed.

Reg. 12333, at §1607.1 (b) (August 1, 1970). U.S. Bureau of the

Census, U.S. Census of Population: 1960, Vol. 1, P art 35, at Table

47 p. 167.

21

tioners, most of whom finished their schooling before the

1954 Brown decision began the erosion of pervasive prac

tices of segregation and discrimination. The resulting in

ferior education and a tendency to earlier dropping out

of school are racial characteristics of petitioners just as

clearly as is living in a ghetto. This point—that discrimina

tion on the basis of education and test-taking ability is

a form of racial discrimination—was recognized by this

Court in Gaston County, North Carolina v. United States,

395 U.S. 285 (1969). There the appellant had sought to

institute a literacy test for voter registration. The United

States opposed this test under the Voting Rights Act of

1965, contending that use of the test had “the effect of

denying or abridging the right to vote on account of race

or color” because of the inferior educations blacks had

received; and this Court sustained the Federal government

contention.

These facts regarding black/white education disparities

make a very salient point, which numerous courts and

governmental equal employment agencies have recognized.

If requirements such as a high school diploma or passage

of an “intelligence” test could freely be imposed, every

employer in North Carolina and throughout the South

could create a racially discriminatory promotional pre

ference of three to one, or better, in favor of whites. Such

a practice could result in a closing of the decent employ

ment market to all but a handful of blacks. This is not an

idle fear; since the enactment of Title VII there has been

an upsurge in use of tests, often as the sole basis for

making employment or promotion decisions.14

14 U.S. Dep’t. of Labor, Validation of Employment Tests by Con

tractors and Subcontractors Subject to the Provisions of Executive

Order 11246, at §§1 (d), (e), 33 Fed. Reg. 14392 (1968); Wall St.

J., Feb. 9, 1965, at 1, col. 6.

22

On the other hand, courts and equal employment agencies

have also recognized that Title YII does not go so far as

to guarantee a job to every black citizen. It is an unfor

tunate fact of life in America that a heritage of discrimina

tion has left many blacks with insufficient skills for many

of the better jobs in the economy. The disparity in black-

white test scores and education levels is to some extent a

reflection of the same deprivation as this lack of skills.

B. The Established Method of Guarding Against Dis

criminatory Test and Educational Requirements,

While Protecting the Reasonable Needs of an Em

ployer, Is to Insist That Such Requirements Be Re

lated to Job Performance Needs.

The universal response of those courts and agencies con

cerned by this dilemma has been to insist on job-related-

ness as the sine qua non of fair use of tests and educational

standards. This does not mean that.a test must. ha..a .sample.

ac,IIal -iol) 'dd’1'0'1 for or tIu>t etnployefs cannot con.

..aider reasonable future promotional possibilities in estab-

, lifihing.aiggt^A8 defined by the Equal Employment Oppor

tunity Commission, the agency charged with enforcement

of Title VII, it means merely that tests must:

^.M riY-.measure the knowledge or skills required by the

particular job or class of jobs which the applicant

' seeks or which fairly affords Iho employer a chance to

measure the applicant’s ability to perform a particular

job or class of jobs.-’, EEOC Guidelines on Employ

ment Testing Procedures (1966), reprinted at A. 129b,

130b.15

_15 For decisions applying these guidelines, see, e.g., EEOC De

cision 70-552 (Feb. 19, 1970), in CCH Fair Employment Prae.

Guide 116139: EEOC Decision Case No. NO6809-327E (June 18,

1969), in CCH Fair Employment Prac. Guide 8516; EEOC Deci

sion, Dec. 6, 1966, reprinted at p. Br. Ap. 3, infra; EEOC Decision

Dec. 2, 1966, reprinted at p. Br. Ap. 1, infra.

23

The EEOC takes a similar position regarding educational

requirements.16 Most recently the EEOC position has been

elaborated in its new Guidelines on Employee Selection

Procedures, 35 Fed. Beg. 12333 (August 1, 1970). These

Guidelines which specifically cover intelligence and aptitude

tests and educational requirements, id. at § 1607.2, demand

that employers using tests have available

“data demonstrating that the test is predictive of or

signiBcantly correlated with iii,;H>i -anl.''efements of _

"work "iseEaviOT1 comprising or relevant to the job or

joloVTdr wFicBGuidelines are being evaluated.” Id. at

~fliief:4tc)':'' ’.....

Virtually the identical requirement is imposed by the Office

of Federal Contract Compliance (OFCC) enforcer of Ex

ecutive Order 11246 against discrimination by government

contractors. Validation of Tests by Contractors and Sub

contractors subject to the Provisions of Executive Order

33 Fed. Reg. 14392, §2(b) (1968). The same principles of

job relatedness have also been adopted by the several state

fair employment agencies which have spoken on the

subject.17

In the courts, although no other Court of Appeals has

dealt at length with issues of testing and educational re

quirements, at least two District Courts in other circuits

16 See EEOC Decision, Dec. 6, 1966, reprinted at p. Br. Ap. 3,

infra. Contrary to assertions made in respondent’s opposition to

certiorari, a careful reading of this EEOC decision will show that

it involved an educational requirement (8th grade) as well as tests.

17 California, Fair Employment Practices Equal Good Employ

ment Practices, in CCH Employment Practices Guide 1}20,86i;

Colorado Civil Rights Commission Policy Statement on the Use of

Psychological Tests in CCH Employment Practices Guide ^21,060;

Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission, Affirmative Action

Guidelines for Employment Testing, in CCH Employment Prac

tices Guide j[27,295.

24

have done so, and have resolved the issue in favor of a job-

relatedness requirement. Most explicit is Arrington v.

Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, 306 F. Supp.

1355 (D. Mass. 1969):

“ [I]f there is no demonstrated correlation between

scores on an aptitude test and ability to perform well

on a particular job, the use of the test in determining

who or when one gets hired makes little business sense.

When its effect is to discriminate against disadvantaged

minorities, in fact denying them equal opportunity for

public employment, then it becomes unconstitutionally

unreasonable and arbitrary.” 30 F. Supp. at 1358.

This was a decision based on the Fourteenth Amendment.

But the same view was adopted under Title VII in United

States v. E. K. Porter Co., 296 F. Supp. 40 (N.D. Ala.

1968), appeal noticed, 5th Cir. No. 27703. There the court

reasoned:

“the court agrees in principle with the proposition that

aptitudes which are measured by a test should be rele

vant to the aptitudes which are involved in the per

formance of jobs.” 296 F. Supp. at 78 (dictum).

Other Courts of Appeals and District Courts have also in

dicated adherence to a similar point of view. See United

States v. Sheetmetal Workers Local 36, 416 F. 2d 123, 136

(1969); Bobbins v. Local 212, IBEW, 292 F. Supp. 413,

433-34, 439 (S.D. Ohio 1968); Penn v. Stumpf, 308 F. Supp.

1283 (N.D. Calif. Feb. 3, 1970); cf. Porcelli v. Titus, 302

F. Supp. 726, 60 Lab. Cas. 1J9302 (D. N.J. 1969); Colbert

v. H.K. Corporation, C.A. No. 11599 (N.D. Ga, July 6,

1970) appeal noticed August 3, 1970.18

18 In Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., —— F. Supp.

— , 60 Lab. Cas. j[9297 (W.D. Ark. 1969), appeal noticed, 8th

25

In looking to job relatedness as the touchstone of fair

use of educational and test requirements, these courts are

merely carrying forward a Title VII principle firmly estab

lished in a series of cases challenging other objective em

ployment requirements. The use of tests and educational

requirements is but one example of a new breed of racial

discrimination. While outright and open exclusion of

Negroes is passe, the use of various forms of neutral, ob

jective criteria which systematically reduce Negro job op

portunity are producing much the same result. As this

Court has long recognized in other contexts of racial dis

crimination, those rules which are objective and neutral in

form may well be racially discriminatory in substance and

effect. Under this principle, the Court has, for example,

struck down grandfather clauses for voter registration,19

the use of tuition grant arrangements which foster segre

gated schools,20 and the use of a gerrymander which under

cuts Negro voting power.21 Under Title VII, as well as in

these other contexts, it is essential that “sophisticated as

well as sim ple minded modes of discrimination” 22 be out

lawed.

The initial Title VII case challenging an objective cri

terion that caused racial discrimination was directed at the

practice of nepotism. In the context of a white dominated

Cir. No. 19969, a series of preemployment tests were sustained

without specifically inquiring into job-relatedness. However, since

the court found that the tests were “simple”, that “plaintiff himself

did well on them”, and that the tests were not operating as a serious

barrier to black employment, it was hardly necessary to look to job

relatedness. Id. at 6746.

19 Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347 (1915).

20 Louisiana Financial Assistance Comm’r v. Poindexter, 389

U.S. 571 (1968), affirming 275 F. Supp. 833 (B.D. La. 1967).

21 Gomillion v. Ligktfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960).

22 Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268, 275 (1938).

26

work force, nepotism, even though primarily motivated by

racially innocent familial purposes, has a highly discrim

inatory effect. A nepotic practice was therefore struck

down in Local 53, International Assoc, of Heat & Frost

Insulators and Asbestos Workers v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047

(5th Cir. 1969). !As the Fifth Circuit later explained, the

nepotic practice violated Title VII because “it served no

purpose related to ability to perform the work in the as

bestos trade,.? Local 189, United Paper-makers and Paper-

workers v. United States, 416 F.2d 980, 989 (5th Cir. 1969),

cert, denied, 397 TT.S. 919 (1970). In other words, the prac

tice was not job related.

The court in the Papermakers Local 189 case went on to

extend this job-relatedness principle to strike down certain

seniority rules. These rules preferred white workers over

their black contemporaries on the basis of seniority ac

quired when the black workers had been openly excluded

from desirable jobs. Even though these seniority rules were

adopted innocently for nonracial reasons, the court con

cluded that such rules could not be sustained where they

had the effect of barring black workers from jobs they were

capable of performing. Id. at 988. The same application

of the job-relatedness principle to strike down discrimina

tory seniority rules has been made by the Eighth Circuit

and by District Courts in the Sixth and Fourth Circuits.

United States v. Sheet Metal Workers, Local 36, 416 F.2d

123 (8th Cir. 1969); Dobbins v. Local 212, IBEW, 292

F. Supp. 413 (N.D. Ohio 1968); Quarles v. Philip Morris,

Inc., 279 F. Supp. 505 (E.D. Va. 1968). See also United

States v. Hays Int’l Corp., 415 F.2d 1038 ( 5th Cir. 1969).23

23 There is one District Court decision contra in the Fifth Cir

cuit, United States v. H. K. Porter Co., 296 F. Supp. 40 (N.D.

Ala. 1968) appeal noticed 5th Cir. No. 27703. However, this deci

sion preceded the Court of Appeals decisions in Papermakers Local

189 and Hayes In t’l. Corp., cited above, and is plainly overruled

by them.

27

And in a very recent case, the principle was applied to strike

down the discriminatory use of arrest records. Gregory v.

Litton Systems Inc., ----- F. Supp. ----- ; 63 Lab. Cas.

91 9485 (C.D. D. Calif. July 28, 1970).

As Judge Sobeloff’s dissenting opinion below explained,

the teaching of these seniority and nepotism cases is that:

“the statute interdicts practices that are fair in form, but

discriminatory in substance . . . The critical inquiry is

business necessity and if it cannot be shown that an

employment practice which excludes blacks stems from

legitimate needs the practice must end.” 420 F.2d at

1238.

Judge Sobeloff went on to observe that this principle ap

plies to discriminatory tests and educational requirements

as well as to seniority and nepotism. Where such require

ments are not job-related they are not justified by business

necessity and must be struck down.24 *

The rationale of those courts and agencies in insisting

upon job-relatedness is clear. If a test, educational stan

dard (or other objective requirement) is job-related, em

ployees are hired or promoted on the basis of their ability

to perform, which is fair. But where a test or educational

requirement is not job-related, hiring and promotion is

done on the basis of educational and cultural background,

which given the facts about schooling, housing and other

factors affected by race, is only thinly veiled racial dis

crimination. This racial discrimination in some cases may

be a product of naked racism. In other cases, it may simply

be motivated by a commitment to what some may perceive

as middle class values and certain personal life styles. But

in either case, the result is the same—seriously reduced

24 See generally Cooper and Sobol, Seniority and Testing Under

Pair Employment Laws, 82 Harv. L. Rev. 1593, 1669-73 (1969).

28

black job opportunity and gross employment preference

for whites over blacks26—and it is this discriminatory re

sult which Title VII declares unlawful.26

The decision below stands out in bold relief against the

virtually unanimous endorsement of the job-relatedness

principle by other courts and agencies. This principle was

openly rejected by the court below. Specifically, as to the

test requirement, the Court of Appeals recognized:

“The [District Court! held that the tests . given by ̂

T Duke were not job-related. . . . 420 F.2d at 1234. k

But the court went on to conclude:

“We agree with the district court that a test does not

have to be job-related in order to be valid under [Title

VII].” 420 F.2d at 1235.

26 Black unemployment, has run at roughly double the white rate

for the past two decades and continues at that rate even today.

See National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, Report

253 (Bantam Ed. 1968) ; Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment

and Earnings, June 1970, Table A-3, Major Unemployment Indi

cators.

26 The emphasis or result rather than motive is clear in sections

703(a)(2) and 703(c)(2) of Title V II which define unlawful

practices as those which “tend to deprive” or “adversely affect”

because of race, without reference to the employer’s*'^reasdM'“TOr'

the practices. The only reference to intent in the general provi

sions of Title VII is in a remedial provision, section 706(g), which

is designed only to assure that employers are not subjected to in

junctions for accidental events. Any knowing and purposive act,

such as the intentional adoption and continuation of test and edu

cational requirement with full knowledge of its effects is covered

by this provision. Papermakers Local 189 v. United States, 416

F.2d 980, 995-97 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 397 U.S. 919 (1970).

See Blumrosen, Seniority and Equal Employment Opportunity:

A Glimmer of Hope, 23 Rutgers L. Rev. 268, 280-84; Cooper &

Sobol, Seniority and Testing Under Fair Employment Laws, 82

Harv. L. Rev. 1598, 1674-76 (1969). “Intent” is also referred in a

special section dealing with tests, section 703(h), which is dis

cussed at pp. 46-51, infra.

29

As to tlie diploma requirement, the court was less explicit,

but it plainly did not ask, as do the EEOC and other courts

and agencies, that the requirement be shown to “fairly

measure knowledge or skills” needed on jobs at Dan River.

Moreover, since Duke’s own testimony established that the

tests and the diploma requirement measure the same thing

(A. 181a), if the tests are not job-related presumably the

diploma requirement also is not. Instead of evaluating job

relatedness, the Court of Appeals seemed to be searching

for some affirmative evidence of racial animus—some show

ing of a motive to discriminate in adopting the challenged

requirements. If this is to be the standard, then Title VII

will be rendered largely ineffective in pursuing the goal

of full fair employment. The record in this case indicates

how easily any employer can justify even the most arbitrary

and discriminatory use of tests under the standard applied

by the Court of Appeals. See pp. 39-44, infra.

By its failure to insist on a reasonable relationship be

tween the diploma/test requirement and job performance

needs, both the Court of Appeals and the District Court

have rejected the established standard for preventing un

fair use of test and educational requirements and have

opened the door to evasion of Title VII by innocence and

design. This Court should recognize the expertise of the

EEOC87 and reaffirm the soundness of the job-relatedness

requirement.

27 See Udoll v. Tollman, 380 U.S. 1, 16 (1965) ; FTC v. Colgate-

Palmolive Co., 380 U.S. 374, 385 (1965); Fawcus Machine Co. v.

United States, 282 U.S. 375, 378 (1931) ; United States v. American

Trucking Assn., 310 U.S. 534, 549 (1940) ; United States v. Public

Utilities Comm.. 345 U.S. 295, 314-315 (1953) ; FTC v. Mandel

Bros., 359 U.S. 385, 391 (1959). This point is further developed in

the brief of the United States as amicus curiae.

30

II.

The Record Below Offers No Basis for Finding That

the D ip lom a/T est Requirem ent Meets This Job-Related-

ness Standard,

The method of determining whether a diploma/test re

quirement is reasonably related to job performance needs

will vary from case to case. In some cases the relationship

will be patent. For example, in one recent decision the

EEOC sustained use of tests of arithmetic and change-

making ability for selecting “checkers”. In so doing, the

Commission observed that the testTcoWred “specific skills

(change making and computation) which are actually per

formed by incumbents of the job classifications for which

they are administered” .28 InJfagjaasft.i)f JR»2£,

aptitude tests, the EE()fT7requently calls for more thor-

o agT stady^^nstify test use.2* Obviously many factors

—will influence this determinalion. including the extent to

which the requirement is prejudicing black workers. A re

quirement which does not result in a great preference for

whites over blacks need be subjected to little, if any, exami

nation under fair employment laws.30 However, the di

ploma/test requirement used in this case is clearly one

which has a serious prejudicial effect on blacks, and the

28 EEOC Decision No. 70-630, Case No. AT 68-3-824E (Mar. 17,

1970), in CCH Fair Employment Pract. Guide ff6136.

89 See EEOC Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures, 35

Fed. Reg. 12333 (August 1, 1970). EEOC Decision No. 70-501,

Case YAT9-633 (Jan. 29, 1970), in CCH Fair Employment Prac.

Guide Tf6112 (covering several aptitude tests including Bennett

test used by D uke); EEOC Decision No. 70-552 (Feb. 19, 1970),

in CCH Fair Employment Prac. Guide ^6139 (covering Wonderlic

and Bennett tests used by Duke).

30 See Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co.,----- F. Supp.

----- , 60 Lab. Cas. f9297 (W.D. Ark. 1969).

31

record is devoid of any meaningful showing that the re

quirement is related to job performance needs. Therefore,

if the court below had made any inquiry beyond merely

looking for an affirmative showing of racial animus, the

practices of Duke would have been found unlawful.

A. The Diploma/Test Requirement Clearly Has a

Prejudicial Effect on Black Workers.

The prejudicial effect of this requirement is firmly estab

lished by the abundant data cited earlier—̂that only Va as

many blacks as whites in North Carolina have a high school

•diploma,,..and. onb^a-iraction as m^y'^lach^ as whites will

pass the Wonderlic and Bennett tests*. Sfee pp. 19-20, supra.

But beyond these general statistics, the prejudicial effect

can also be seen in the specific impact of the requirement

at Duke. Since the requirement applies only to certain

interdepartmental transfers, its real impact is only on those

employees in departments who need to transfer for decent

promotional opportunity. The only persons thus burdened

are the four black workers involved in this petition. They

are frozen in the Dab or Department with a top pay expecta

tion of only. $1,895 /per hour (A. 72b).31 All of the white

workers are in departments with promotional expectancies

leading to substantial pay levels.

B. It Cannot Be Assumed Without Supporting Evidence

That the Continuation of This Prejudicial Require

ment Is Related to Duke’s Job Performance Needs.

The aspect of diploma and test requirements that is so

appealing and yet so deceptive to employers is a super

ficially plausible relationship to job performance. The pos

sibility of getting a more “intelligent” employee through

use of such devices is often assumed to be a means of get

31 The foreman job in the Labor Department pays per

hour, but it is not open to non-high school graduates’ (A. 63b).

32

ting more productive and more valuable employees. But

in the context of industrial jobs, such as those at Duke’s

Dan River Plant, an immense body of evidence has shown

this assumption to be unfounded.

This point has been proven time and again in careful

studies by industrial psychologists investigating the

“validity” of standard tests such as the Wonderlic and the

Bennett in predicting an individual’s ability to perform

industrial jobs. It has been demonstrated in dozens of

studies there is commonly little or no relationship between

test scores and job performance. An eminent industrial

psychologist, Dr. Edwin Ghiselli of the University of Cali

fornia, recently reviewed all the available data on the pre

dictive power of standardized aptitude tests in an effort to

develop better testing practices. Dr. Ghiselli is a strong

supporter of tests. Yet he was forced to conclude that in

trades and crafts aptitude tests “do not well predict suc

cess on the actual jobs,” 32 and that in industrial occupa

tions “the general picture is one of quite limited predictive

power.” 33 In many situations there is actually a negative

relationship between test scores and job success.34

What does this mean in practical terms'? An example,

which is by no means unusual, is contained in a report of a

study performed in a large Southern aluminum plant.35

The study showed that scores on the Wonderlic test had

no relation whatsoever to job performance ability. Black

32 B. Ghiselli, The Validity of Occupations Aptitude Tests 51

(1966).

33 Id. at 57.

34 E.g., id., at 46.

35 Mitchell, Albright & McMurry, Biracial Validation of Selec

tion Procedures in a Large Southern Plant, in Proceedings of 76th

Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association,

Sept., 1968, reprinted in Appendix hereto at pp. Br. Ap. 6-7, infra.

33

workers were scoring only half as well as whites on the

test, but there was no difference between races in job per

formance ability. If the test had been blindly used, Negroes

would have been grossly screened out without business need

and contrary to the interests of the employer. Other studies

have shown, for example, that the Wonderlie and related

tests are of no significant vaES3£-pS,3ifiiing performance

brUrfinance facp:)ry workers or radio assembly workers,36 37

workers " in the printing and publishing industry,3,7' Birth

Workers in the manufacture of finished lumber products

and transportation equipment.38 As to the Bennett and re

lated tests, studies have shown, for example, that test

scores are of no significant value in predicting job success

in occupations such as textile weaving39 and jobs in the

manufacture of electrical equipment.40

These results should not be surprising. Aptitude tests

may be expected to predict future academic performance

rather well because grades are measured by performance

on more tests. But industrial job performance involves a

range of skills and abilities entirely divorced from a pris

tine test room setting. There is an understandably low

correlation between test taking skills and job performance

skills.

This is particularly true when the test is being given to

a mixed racial group. One of the basic assumptions under

lying tests is what might be called the “equal exposure”

36 Super and Crites, Appraising Vocational Fitness 106 (Rev.

ed. 1962).

37 E. Ghiselli, The Validity of Occupations Aptitude Tests 137

(1966).

38 Id. at 135, 148.

33 I d at 132.

40 Id. at 147.

34

assumption. Because a test measures how well a person

has learned various skills and information, test scores may

sometimes make a reasonably useful prediction of perfor

mance on the job. But when this equal exposure assumption

is false—as it surely is in the case of comparisons between

Southern Negroes and whites—the already shaky basis for

test predictions is drastically undercut.41 For this reason,

as petitioners’ expert witness Dr. Richard Barrett testified

he found in his Ford Foundation study,} a test may predict

differently for one racial group than ft does for another

Of course, tests are not always so poor at predicting. In

some cases tests may be reasonably useful. The point is

that predicting job performance on the basis of tests or on

other measures of educational background is a highly pre

carious endeavor dependent on a myriad of factors.42 Be-

41 This point was made very clearly by the court in Hobson v.

Hansen, 269 F. Supp. 401, 484-485 (D.D.C. 1967) :