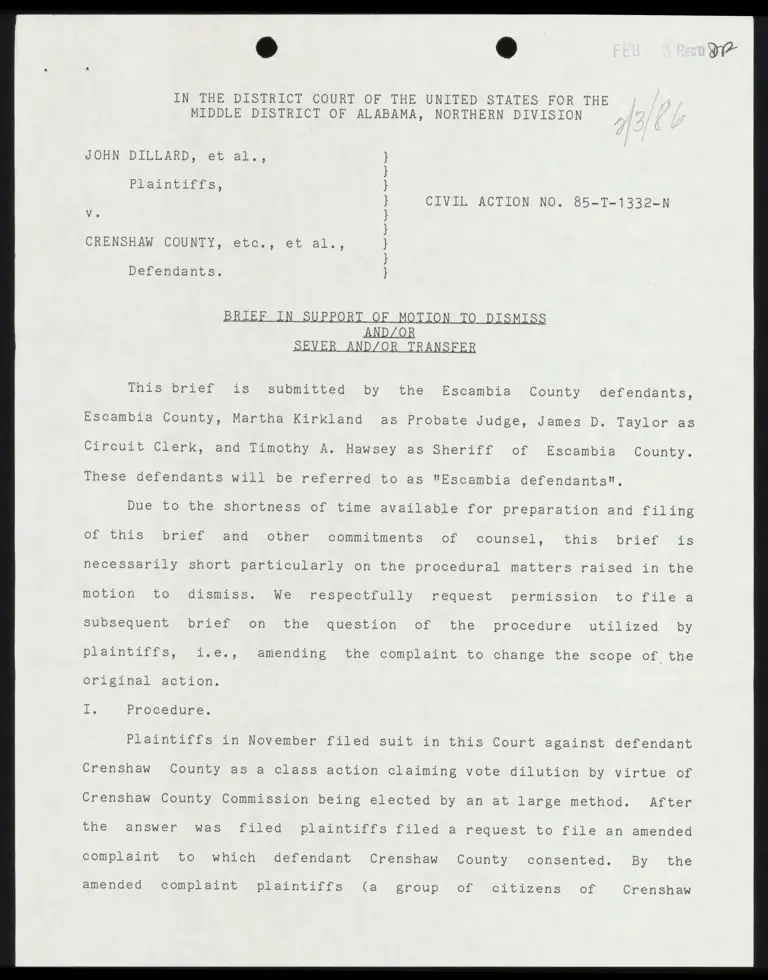

Brief in Support of Motion to Dismiss, Sever or Transfer

Public Court Documents

February 3, 1986

10 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Brief in Support of Motion to Dismiss, Sever or Transfer, 1986. 562676c0-b7d8-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0c986f14-2db0-46da-80fe-02827850ffe2/brief-in-support-of-motion-to-dismiss-sever-or-transfer. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES FOR THE

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA, NORTHERN DIVISION

JOHN DILLARD, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

CIVIL ACTION NO. 85-T-1332-=N

Yo

CRENSHAW COUNTY, etc., et al.,

r

d

e

d

N

d

C

d

C

d

A

d

N

d

C

d

A

d

Defendants.

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF MOTION TO DISMISS

AND/OR

SEVER AND/OR TRANSFER

This brief is submitted by the Escambia County defendants,

Escambia County, Martha Kirkland as Probate Judge, James D. Taylor as

Circuit Clerk, and Timothy A. Hawsey as Sheriff of Escambia County.

These defendants will be referred to as "Escambia defendants".

Due to the shortness of time available for preparation and filing

of this brief and other commitments of counsel, this brief “is

necessarily short particularly on the procedural matters raised in the

motion to dismiss. We respectfully request permission to file a

subsequent brief on the question of the procedure . utilized by

plaintiffs, i.e., amending the complaint to change the scope of the

original action.

I. Procedure.

Plaintiffs in November filed suit in this Court against defendant

Crenshaw County as a class action claiming vote dilution by virtue of

Crenshaw County Commission being elected by an at large method. After

the answer ‘was filed plaintiffs riled a request to file an amended

complaint to which defendant Crenshaw County consented. By the

amended. complaint plaintiffs (a groups of "citizens of Crenshaw

County) proceeded to add other parties plaintiff, citizens of seven

other political subdivisions, (counties), and as parties defendant the

Officers of those seven other political subdivisions. Five of the

seven political subdivisions are located in the Northern District of

Alabama. One (Escambia) is located in the Southern District of Alabama

and only one of the added county political subdivisions (Coffee) is

located in the Middle District as'will be ‘discussed later in this

brief. This suit in effect amounts to eight separate and distinct

class actions which have been joined by the method of amended

complaint into one class action before this Court in the Middle

District of Alabama which Escambia defendants respectfully insist is a

violation of federal procedure.

Alls relevant {est 'factors for voter dilution, as will be

discussed in more detail in this brief, involve each political

subdivision separately. There is no way that a single trial or single

set of facts can be deveoped that would cover all eight political

subdivisions as a group. Further, each group of plaintiffs, and there

are eight ‘individual "groups by. virtue of their residence, have

alleged in common only one factor, i.e., the color of their skin. We

respectfully insist that what is involved is not a single class action

but rather eight individual class actions against eight individual

political subdivisions, each with its own separate factual

considerations and circumstances.

There are several rules of civil procedure covering the addition

of.< parties, such. as: Rules 14, 19, ‘and 20, F,.R.C.P. however, none

appear to cover the procedure utilized “in this ‘particular. case,

Normally a ‘party plaintiff 1s added by a motion to intervene, c.f.

American Pipe & Construction Co, v. Utah, #414 U.S, 538, 945 S.Ct... 756

(1974) ‘and Stull v. Bayard, 424 F. Sopp.“ 937 (S.D.N.Y,.1977), Afrf'd 561

F.2d 429, (2d Cir. 1977). We recognize however, that an amendment has

been allowed in certain instances particularly where the parties to be

added as parties plaintiff have consented in writing to such an

amendment. "See Osturo _v, _Psn Am, 378 F.Supp.-80:(D.C. Ha. 19 9)

However, by eifher procedure, such parties should have a commonality

with the original action brought. In this particular instance Escambia

defendants respectfully insist there is no such commonality. The

parties added both as plaintiffs and defendants neither reside in,

vote in, nor have any apparent interest or alleged interest in the

political process of Crenshaw County. The addition of such parties

would appear to be a total misjoinder of parties such as noted by Rule

21, F.R.CiP, Escambia defendants could not possibly offer any relief

to the original party plaintiffs. They reside, vote and apparently are

otherwise totally interested in only the political process of Crenshaw

County. Those original plaintiffs could not possibly have standing to

bring a class action against the Escambia defendants, by amendment or

otherwise. For these reasons we respectfully submit that there has

been a total breakdown of proper procedure in this case.

What the plaintiffs have attempted to do by a piggyback type

amendment with the consent of Crenshaw defendants is bring eight

separate voter dilution suits, eight distinct class actions, into one

Court proceeding without regard to the procedures of multi district

litigation prescribed by Congress, 28 U.S.C. Section 1407. At least

one political subdivision, has indicated it 1s presently in another

Court. Removal by amendment simply is not the proper procedure.

Il. Venue,

28 U.S.C. 1391(b) would require. a voter ‘dilution suit

against Escambla defendants to be brought. in the United States

District Court for the Southern District of Alabama, and if Escambia

defendants. are correct, this Court should either dismiss or

sever ‘and in’ the ‘interest: of Justice transfer this case to the

Southern District of Alabama under Section 1406(a). In the alternative

the Court should sever and transfer the case under Section 1404(a) for

the convenience of the parties and witnesses and in the interest of

Justice. The only parties plaintiff that could possibly have standing

to bring suit against Escambia County are those residing in that

political subdivision, namely McBride, White, McGlasker, America and

McCorvey (hereinafter referred to as "Escambia plaintiffs"). Even the

principal attorneys for the Escambia plaintiffs are located in the

Southern District of Alabama.

The Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals in United States v. Dallas

County Commission, 739 F.2d 1529 (1984), reiterated and approved the

test factors previously set by the Court in United States Vv. Marengo

county commission, 731 F.2d 1546 (11th Cir. 1984). In each instance

the: Court has stated that it interprets Section 2 of the Voting

Rights. Act ‘of 1965, as amended, 42 U.3.C., Sections 1973(a){(b), as

* ®

requiring a test of "results" rather than a Lest of "intent", The

Court further considered the nine typical factors established by the

Senate Committee on the Voting Rights Amendment of 1982 {Senate Report

Number 417, "97th Cong., 2d Sess, 2 (1982). In applying these

principles this Court of necessity must consider and plaintiffs must

prove a "totality of circumstance" in each separate distinct political

subdivision. A mere finding of totality of circumstance indicating

voter dilution in Crenshaw County or Pickens County, Lawrence County

or Coffee County, is not going to be a finding of voter dilution in

Escambia County. There will unquestionably be some prior acts not

committed in "modern" (post 1965) times applicable to all counties of

the State of Alabama and indeed to all political subdivisions of any

state in the old south. However, there would not necessarily be

factors common at the present time to each of the eight

political subdivisions. Judge Godbold in Dallas case, supra, (at page

1547) approved the 1965 date as "modern times" for other factors to

support or deny a finding of dilution.

The test factors that this Court must consider in finding a

voter dilution will of necessity involve different findings as to each

political subdivision; the extent ©0 ‘which voting in ‘elections is

racially polarized; voting practices or procedures that may enhance

the opportunity for discrimination; the candidate slating process; the

extent to which members of the minority group bear the effects of

discrimination, such as education, employment and health hindering

their ability to participate; whether political campaigns are overt or

subtle racial appeals; the extent fo which members of the minority

group. have ‘been elected to public office; whether there is =

significant lack of responsiveness and whether there is any voter

disqualification or pre-requisite to voting. Other factors considered

Would be lingering hostility, fear of the county courthouse,

Participation in the 'elecforial process, registration of voters,

deputy registers, convenience to rural areas, such as approved in

Dalles, supra. Of: ithe Senate Committee factors, only (wo could

conceivably be common in proof. Eaeh of the above factors we

respectfully submit necessitates a separate hearing for each political

subdivision, ‘The finding ‘by the Court "as {oo dilution or lack of

dilution on any particular political subdivision would not affect the

finding as to any toutes political subdivision.

in addition to ithe lack of commonality as to proof of factors

required for voter dilution this Court in the event it finds dilution

to exist in a particular political subdivision must order a remedy.

That remedy of necessity is going to be different in each political

subdivision. For example, in many counties the probate judge is

chairman of the county commission and it probably has four districts.

In other counties, however, there will be a more or less number of

districts and the chairman may either be appointed or elected by the

county at large. The geography and demography of each county will of

necessity be different as will the area location of the minorities to

be + protected, The ‘availability of maps and census data as to areas

within the county will be different. The census for example in rural

counties will not necessarily specify the number Of citizens in a

particular area. Other problems to be considered by the Court in

drafting of ‘district lines is other minorities to be protected.

Escambia County has a large Indian population and =a growing Asian

population.

All of these factors we respectfully submit to this Court should

show that this case is not a single voter dilution class action but

rather eight separate class actions, The majority of those eight

separate cases would normally have been brought in the Northern

District of « Alabama. Only two of the political subdivisions involved

are located in the Middle District and Escambia is the lone county in

the Southern District.

This! writer: is reminded. of the prison and jail suit pending in

this Court in 1976, Adams, et al, and United States, Intervenor wv,

Mathis, ef al,, Civil Action Number T4-70-S, in that case plaintiffs

and the United States as Intervenor attempted to broaden the class

aspect of the 'getion so as to bring in as a defendant class other

political subdivisions, counties and municipalities and thereby effect

one reform order setting forth standards in local Jails. This Court

(Judge Johnson presiding) entered an order on May 10th, 1976 denying

the defendant class and in so doing recognized the divergent problems

of each political subdivision involved. The Court noted the vast

differences in size, population, function and condition of the various

municipal and county jails throughout the state of Alabama. It . noted

that each: municipal and county governing body had considerable

autonomy in the operation of its jails. Thus conditions established by

the evidence with respect to the jails operated would not establish

that. such conditions exist. in Jjalls operated by the absent class

members. The test applied by the Court was that of a "totality of

conditions! of confinement which is virtually the same ‘test that must

be =applied in this Court under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act,

supra. The Court distinquished the case of Washington v. Lee, 263

F.Supp. 327 (M.D. Ala. 1966) by noting the single issue before the

Court in the Washington case was the constituiionality of racial

segregations in state penal facilities. Unlike Washington, Adams

presented a miriad of complex legal and factual issues. The defendants

separately disputed the exsitence of the alleged conditions and

consequently the interest of each defendant in controlling his or her

defense out weighed the possible convenience of the class action

device,

Admittedly, Adams presented the immediate question of a defendant

class, however, the underlying question of commonality and diversity

is present in both Adams and instant case. Commonality is a big

factor in deciding whether the venue should remain in this Court. It

would appear that this Court faces an even more complicated

evidentiary problem than that faced by the Court in Adams, supra.

What could be more diverse than responsiveness of elected officials to

minority voters or political campaigns involving racial appeals.

vst 2D

would submit that none of the above factors will be found to exist in

Escambia County, however, we cannot and would not pretend to speak for

the conditions in other counties.

Following the denial of the defendant class by the order of May

10th, 1976 the Court in Adams, supra on July 1st, 1976 denied the

Plaintiff.

CONCLUSION.

Based on the above and other factors raised in the motions,

Escambia defendants respectfully move the Court to dismiss the

complaint as amended or alternatively to sever the complaint: as to

these defendants and/or transfer venue to the Southern District of

Alabama. In view of the Court's order directing the briefs to cover

the dismissal feature and venue feature of the motions we did not

address the alternative motion to deny the class certification. This

motion 1s probably premature, however, of necessity it involves many

of the same factors raised in the above motions and will be addressed

at a future time.

CRA

dames W. Webb

Attorney for Escambia County

OF COUNSEL:

WEBB, CRUMPTON, McGREGOR, SCHMAELING & WILSON

166 Commerce Street, P.O. Box 238

Montgomery, Alabama 36101

(205) 834-3176

\ ] fpr

Yl dd 74

Lee Ofts

Attorney for Escambia County

OF COUNSEL:

Otts & Moore

P.O. Box 467

Brewton, Alabama 36427

(205) 867-7724

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify . that. copies’ of the foregoing brief in

support of motion to dismiss and/or sever and/or transfer have been

mailed to Larry T. Menefee, Esquire, James U. Blacksher, Esquire and

Wanda J. Cochran, Esquire, Blacksher, Menefee & Stein, 405 Van Antwerp

Building, P.O. Box 1051, Mobile, Alabama 36633, . ‘Terry G, Davis,

Esquire, Seay ~“& Davis, 732 Carter Hill «Road, =PJ0, Box 6125,

Montgomery, Alabama 36106, Deborah Fins, Esquire and Julius L.

Chambers, Esquire, NAACP Legal Defense Fund, 1900 Hudson Street, 16th

Floor, New York, New York, 10013, Jack Floyd, Esquire, Floyd, Kenner &

Cusimano, 816 Chestnut Street, Gadsden, Alabama 35999, Alton Turner,

Esquire, Turner & Jones, P.O. Box 207, Luverne, Alabama 36049, D.L.

Martin, Esquire, 215 3. Main Street, Moulton, Alabama 35650, David R.

Boyd, Esquire, Baleh %& Bingham, P.O. Box 78, Montgomery, Alabama

36101, «W.0. Kirk, Jr., Esquire, Curry & Kirk, Phoenix Avenue

Carrollton, Alabama 35447, Barry D. Vaughn, Esquire, Proctor & Vaughn,

1217 N. Norton Avenue, Sylacauga, Alabama 35150, H.R. Burnham, Esquire,

Burnham, Klinefelter, Halsey, Jones & Cater, 401 SouthTrust Bank

Building, P.O. Box 1613, Anniston, Alabama 36202, Warren Rowe,

Esquire, Rowe, Rowe & Sawyer, P.O. Box 150, Enterprise, Alabama 36331,

Edward Still, Esquire, 714 .South 29th Street, Birmingham, Alabama

35233-2510, ‘Reo. Kirkland, ‘Jr., Esquire, P.0. Box 646, Brewton,

Alabama 36427, and all defendants not represented by counsel by

placing copies of the same in the United States Mail, postage prepaid

this the 27th day of January, 198%.

4

Geb 27

FEY W. "Webb