Kadrmas v. Dickinson Public Schools Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1987

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Kadrmas v. Dickinson Public Schools Brief Amici Curiae, 1987. 91d8ef8a-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0cab90ab-ea8b-4509-b7d5-16eb7fb55d18/kadrmas-v-dickinson-public-schools-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

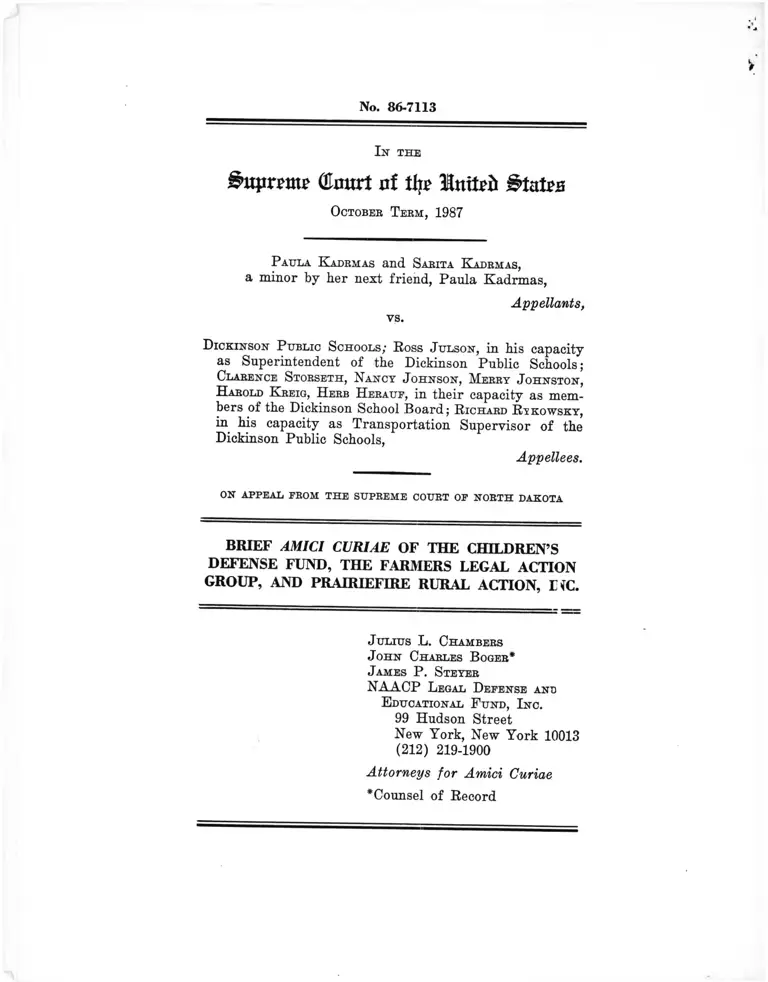

No. 86-7113

I n t h e

Glourt of % MnxUb BtnUs

October T e r m , 1987

P aula K adrmas and S arita K adrmas,

a minor by her next friend, Paula Kadrm as,

vs.

Appellants,

D ic k in so n P u b lic S ch o o ls; B oss J u l so n , in his capacity

as Superintendent of the Dickinson Public Schools;

Cla r e n c e S t o r se th , N a ncy J o h n so n , M erry J o h n st o n ,

H arold K reig , H erb H e r a u f , in their capacity as mem

bers of the Dickinson School Board; R ichard R t k o w sk y ,

in his capacity as Transportation Supervisor of the

Dickinson Public Schools,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE SUPREME COURT OF NORTH DAKOTA

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE CHILDREN’S

DEFENSE FUND, THE FARMERS LEGAL ACTION

GROUP, AND PRAIRIEFIRE RURAL ACTION, INC.

J u l iu s L . C h a m b er s

J o h n C h a r le s B oger*

J a m es P . S tey er

NAACP L egal D e f e n s e and

E ducational F u n d , I n c .

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

*Counsel of Record

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.............. ii

STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF

AMICI CURIAE .................. 2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.................. 5

ARGUMENT ........................... 11

I. Impoverished Families

Like the Kadrmases Are

Forced To Make Impossible

Choices Regarding The

Needs if Their Children ... 11

A. An Explanation of How

Poverty Is Measured ... 13

B. The Rate of Poverty

Has Increased Signi

ficantly in the Past

Decade, Particularly

Among Children ....... 15

C. Increasingly, Rural

Families Have Fallen

Into Poverty ......... 19

D. Poverty Demands Extra

ordinary Sacrifices

From Families Like the

Kadrmases ............. 23

E. Poor Families Like the

Kadrmases Lack Finan

cial Flexibility ..... 30

11

I

F. Conclusion ............ 32

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page 1

Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U.S. 483 (1954) ............ 34 l

Coleman v. Lyng, 663 F.Supp. 1315

(D.N.D. 1987) ........ ’........ 4 1

Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202

(1982) ......................... 29 i

1

Other Authorities

D. Caplovitz, The Poor Pay More

(1967) ......................... 30,31

*

Census and Designation of Poverty

and Income: Joint Hearing Before

t

)

the Subcomm. on Census and Popu- i

lation of the Comm, on Post

Office and Civil Service, and

the Subcomm. on Oversight of the

*

♦

Comm, on Wavs and Means. House

of Representatives, 98th Cong.,

2nd Sess. (1984) ............... 13 , 14

f

1

•

Center on Budget and Policy

Priorities, Gap Between Rich

and Poor Widest Ever Recorded.

(1987) ......................... 19

.

i

Center on Budget and Policy

Priorities, Smaller Slices of

*

1

ill

the Pie. (1985) ...............

Children's Defense Fund,

A Children's Defense Budget:

FY 1988 An Analysis of Our

Nations Investment in Children

(1987) ..........................

Physicians Task Force on Hunger,

Physician Task Force on Hunger

in America. 1985 ...............

R. Plotnick and F.S. Kidmore,

Progress Against Poverty: A

Review of the 1964-1974 Decade

(1975) ..........................

U.S. Department of Commerce,

Bureau of the Census, Money

Income of Households. Families

and Persons in the United States

(Series P. 60) 1984, 1986,

1987 ...........................

16,18

26,28

25

14

passim

I

?

t

No.86-7113

IN THE

UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT

October Term, 1987

PAULA KADRMAS and SARITA KADRMAS,

a minor by her next friend, Paula

Kadrmas,

Appellants,

vs.

DICKINSON PUBLIC SCHOOLS; ROSS JULSON,

in his capacity as Superintendent of the

Dickinson Public Schools; CLARENCE

STORSETH, NANCY JOHNSON, MERRY JOHNSTON,

HAROLD KREIG, HERB HERAUF, in their

capacity as members of the Dickinson

School Board; RICHARD RYKOWSKY, in his

capacity as Transportation Supervisor

of the Dickinson Public Schools,

Appellees.

On Appeal From The Supreme

Court of North Dakota

BRIEF FOR AMICI CURIAE

The Children's Defense Fund, the

Farmers Legal Action Group, and Prairie

Fire Rural Action, Inc. respectfully

submit this brief as amici curiae. upon

2

consent of the parties, pursuant to Rule

36.2 of the Rules of the Court.

STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

The Children's Defense Fund (CDF) is

a national public charity that for nearly

20 years has served as an advocate for

America's children and their families,

especially poor, minority and handicapped

children. CDF's goal is to educate the

nation about the needs of poor children

and to encourage preventive investments

which will promote their full and healthy

development. CDF's work spans a broad

range of public policy issues, including

family income, education, health care,

child care and other services essential

to the well-being of the next generation

and to the future of the nation. CDF

works for policies which will ensure that

children from low-income families develop

sound academic skills through effective

3

preschool, elementary and secondary

school programs.

Farmers' Legal Action Group (FLAG)

is a nonprofit corporation organized to

provide legal education, assistance and

support to financially distressed family

farmers and their attorneys. In the

course of their work, FLAG staff

attorneys , and legal assistants have

p r o v i d e d l e c t u r e s , w o r k s h o p

p j _ , seminars and consultation

on rural poverty issues in more than 30

states. FLAG'S staff meets with and

e x p l a i n s l e g a l r i g h t s a n d

responsibilities affecting farmers in

financial distress. FLAG also publishes

a monthly newsletter that is circulated

nationally and has published numerous

educational books and materials.

In addition, Farmers' Legal Action

Group represents farmers in numerous

4

class action lawsuits which seek to

enforce federal statutes and regulations.

In one case, Coleman v. Lvna. 663 F.

Supp. 1315 (D.N.D. 1987), FLAG attorneys

represent all 250,000-plus borrowers from

Farmers Home Administration throughout

the country. FLAG seeks the permission

of this Court to appear as amicus curiae

on behalf of the farmers and ranchers it

represents in the Coleman v. Lvna

litigation.

Prairiefire Rural Action, Inc. is an

independent, non-profit, education,

r e s e a r c h and c o m m u n i t y action

organization based in Des Moines, Iowa.

Since 1982, it has been actively involved

in developing a regional and national

grassroots response to the economic and

social crisis in American agriculture and

rural life.

5

The organization's principal

objectives include keeping small and

medium-size family farms in operation and

farm families on the land; revitalizing

family farm agriculture in the U.S.; and

building strong coalitions in support of

family farm agriculture.

Prairiefire has worked directly with

farm and rural families adversely

affected by the current economic crisis

and has engaged in public policy research

and legal advocacy. Increasingly,

Prairiefire staff have been called upon

to educate and train the leaders and

staff of farm, rural and religious

organizations responding to the crisis in

their respective states and regions.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

This is a case grounded in the

realities of poverty and what it means to

be poor in America today.

6

Beneath the arguments about the

proper scope of the equal protection

clause lies the dilemma of a poor,

working -class family forced to make

untenable choices concerning the health

and well-being of their children. It is

not just a case about mandatory school

busing fees imposed upon a small

percentage of North Dakota school

children, who are penalized for living in

non-reorganized school districts. It is

also a case about blue collar families

trapped in the grip of poverty, and a

s t a t e f i n a n c i n g s c h e m e w h i c h

unconstitutionally fails to take account

of their plight.

To assist the Court in evaluating

this case, amici hope to place the matter

in its proper context. This case is

7

played out at the "poverty line,"1 below

which 32.4 million Americans currently

manage to survive. For a family at 100

percent of the poverty line - which

permits approximately 85 cents a meal per

household member - $97 in school bus fees

can pose a major financial dilemma.

The case involves a working poor

family, one of more than two millions in

America like the Kadrmases with one or

more members employed fulltime in the

workforce who still live at or below the

margins of poverty. Including

1 For a family of four, the

official poverty threshold in 1986 was

$11,203 a year. This standard is based

on the United States Department of

Agriculture's measure of the cost of a

temporary, low-budget diet, which by 1986

figures amount to approximately $2.55 per

person per day in a family of four. This

figure is then multiplied by a factor of

three to reflect the assumption that food

typically represents one-third of the

total expenses of a low-income family, an

assumption many feel is significantly

outdated.

8

dependents, these families represent 6.4

million people, or 19 percent of the

poor.2 Working poor families have become

commonplace in rural, farm-belt states

such as North Dakota, where the energy

and agricultural sectors have been

buffeted by the economic downswings of

the past decade. For many Midwestern

families like the Kadrmases, poverty has

become the dominant fact of life in the

1980s.

Coping with poverty has forced

parents like Paula Kadrmas to make trade

offs in their children's lives that would

be inconceivable to most Americans.

There is simply not enough money for all

the basic necessities of life, let alone

any luxuries. Young children like Sarita

2 United States Department of

Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Money

^ lcotne------ Households. Families anH

Persons_in the United States 33 (1984

Apr. 1986) (Series P. 60 No. 151).

9

i

>

»

Kadrmas need adequate food and nutrition;

they need clothes; they need decent

shelter; they need adequate health care;

and, of course, they need access to a

decent education, which represents their

best hope for lifting themselves out of

poverty.

Yet each of these bare essentials

exacts a monetary cost. When added

together, the sum total of such

necessities can overwhelm a family living

at the margin of poverty (not to mention

40 percent of indigent households with

incomes which are less than half the

official poverty standard).2 For such

families, $97 a year for school bus fees

represents food out of a child's mouth,

clothing off her back, or heat turned

down low in che bone-chilling winters of

3 United States Census Bureau, 1987

poverty data.

I

10

North Dakota. North Dakota's mandatory

fee, in short, can force poor

families like the Kadrmases to make

bitter choices between the State's

educational demands and their child's

need for food, health care, and adequate

shelter.

The statutes under challenge in the

case are arbitrary and irrational. They

exact no bus fees at all from 85% of

North Dakota's families — whether rich

or poor who happen to live in

reorganized school districts. At the

same time, they allow mandatory bus fees

in districts that have not reorganized,

without providing any waiver at all, even

for the most desperately poor of

families. These statutes thus cast the

heaviest financial burden on an

arbitrary minority of North Dakota

families like the Kadrmases, who are poor

11

and whose voice cannot be heard in the

politie^x prnrp’js. By so burdening the

right of these indigent children to

education, these statutes violate the

Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

ARGUMENT

IMPOVERISHED FAMILIES LIKE THE

KADRMASES ARE FORCED TO MAKE

IMPOSSIBLE CHOICES REGARDING THE

NEEDS OF THEIR CHILDREN *

To those like the Kadrmases who are

poor, poverty is neither a statistical

nor a sociological matter. Their

condition demands a daily struggle for

survival. The deprivation they confront

is real, not a trick of rhetoric or

statistical analysis. Thus any

consideration of the constitutionality of

a $97 bus fee must begin by reflecting

both upon the definition of poverty and

upon what that definition means in human

terms.

12

The Kadrmas family consists of the

appellants, Paula and Sarita, Paula's

husband and two pre-school children. Mr.

Kadrmas was intermittently employed as a

motorman for an oil drilling company at

the time of this action. The trial court

found that the Kadrmas family had a gross

(pre-tax) income at or near the federal

poverty level for a family of five. The

Kadrmases received no federal housing

subsidies, no Medicaid, and no Food

Stamps. Paula Kadrmas indicated that she

and her husband offered shelter and food

to several of her relatives for five

months during the year of the trial,

making a total of up to nine persons

living off an income which barely met the

federal poverty line for a family of

five.4

4 Former co-plaintiff, Marcia

Hall (who is not an appellant in this

Court because she has moved out of North

13

A. An Explanation of How Poverty

Is Measured

The poverty "line" was initially

established by taking the cost of what

the United States Department of

Agriculture in 1959 called the "economy

food plan" (itself a lower-cost diet than

the Agriculture Department's definition

of a "minimum standard diet") and

multiplying it by three.5 * A few years

Dakota) had an income substantially below

the federal poverty standard for a family

of three. Ms. Hall held two jobs in an

attempt to support her two young

children; she received no government

benefits other than some Food Stamps.

and

- censor jnd Designation of Poverty

Income: Joint Hearing Before the

Subcomm. on Census and Population of the

Comm, on Post Office and Civil Service,

and the Subcomm. on Oversight, of the

Comm. on Wavs and Means. House of

Cong., 2nd Sess.

[hereinafter Joint

Income! (testimony

The factor of 3

Representatives. 98th

pp. 8, 11, 14 (1984)

Hearing on Poverty and

of Mollie Orshansky).

was based on surveys by the Bureau of

Census done in 1955 which showed that the

"economy food plan" would cost

approximately one-third of the median

household budget for a family of three.

14

later the number was indexed to annual

changes in the rate of inflation instead

of to annual recalculation of the cost of

the economy food plan.6 The level of

income necessary to escape poverty was

thus deliberately understated at the

Ms. Orshansky testified that "in choosing

the lowest food plan that the Agriculture

Department_had, . . . as in choosing the

so-called multiplier that I did and that

X. got approved. I thought ... that it was

better to maybe understate the need."

X d ., at 11.(Emphasis added). see

Plotnick & Skidmore, Progress Against

Poverty. 32-33 (1975).

/Z •Joint Hearing on Poverty and

Income (testimony of Mollie Orshansky),

supra, at 15. The indexing of the

poverty rate to the Consumer Price Index

was a compromise made in 1969. At that

time, Ms. Orshansky and the head of her

g r o u p in the S o c i a l S e c u r i t y

Administration, Mrs. Marion, decided that

the poverty line should be raised to

compensate for changes in food budget

patterns reflected in a 1965 survey

conducted by the Census Bureau. They

first asked the permission of the Office

of Management and Budget and the Council

of Economic Advisers and were told, "You

can't change it [the poverty line]; it is

no longer yours." The indexing was a compromise.

15

start;7 thereafter that understatement

was locked in by indexation.8 * *

W o r k i n g families like the

Kadrmases, who receive virtually no

government benefits, thus bear the full

brunt of poverty's impact.

B. The Rate of Poverty Has

Increased Significantly in the

Past Decade. Particularly Among

Children

From 1959, when this nation began

keeping poverty statistics, the

percentage of Americans who were poor

dropped rather steadily until 1973, from

' See note 4, supra.

8 Even if the original poverty line

in 1959 was realistic, its counterpart

today is, if anything, too low, since

shelter, home heating and health care

costs to the poor have increased at rates

exceeding the rate of inflation. Center

on Budget and Policy Priorities, Smaller

Slice of The Pie. 16 (1985); Joint

Hearing On Poverty and Income (testimony

of Mollie Orshansky), at 14.

16

22.4 percent to 11.1 percent.9 Over the

next five years, changes were mainly

cyclical, reflecting the severe recession

of 1974-75, but ending with a 1978

poverty rate of 11.4 percent.-1-0 After

1978, however, the rate of Americans

living in poverty began a steady upward

trend, peaking at 15.3 percent in 1983.

While the national rate has declined

slightly since 1984, poverty figures in

the rural Midwest have remained high.

Even the national total of 32.4 million

impoverished citizens in 1986 represents

nearly 8 million more poor Americans than

9 Bureau of the Census, United

States Department of Commerce. Monev

lncgme_and Poverty Status of Familjer ~ ^

Persons— in— the_United States; 1986 21

(Series P.-60, No. 178 July 1987) '

10 Id.

17

in 1978, and more than nine million more

than in 1973 (a 40% increase).11

Equally significant, a major shift

has occurred in the composition of the

poor. With the indexing of Social

Security and the enactment of the

Supplemental Security Income program

(SSI), poverty has decreased among the

eiHpriv. At thp> same time, however, it

has sharply increased for American

children like Sarita Kadrmas. Among

families with children, especially

single-parent families like Marsha Hall

and her two youngsters, poverty has

soared to epidemic proportions in the

1980s. More than one out of every five

American children is now poor.12 *

11 Id.

12 Id. as revised by the Bureau of

the Census in 1987. In North Dakota, the

latest figures reveal that nearly one out

of five children (18.2%) live in poverty

today.

18

Census figures reveal another

disturbing trend about American poverty

in the 1980s: the poor are becoming

poorer, not just more numerous.^

Over- all, the average poor family in

1986 had an income $4,394 below the

official federal poverty level — the

third worst of any year since 1963. The

poor have grown poorer even though a

record 41.5% of all poor people, like the

Kadrmases and Marsha Hall, were working

13 Virtually two out of five poor

Americans (40 percent) lived in families

with income below half the poverty line

in 1986, compared to one-third in 1980

and less than 30 percent in 1975. That

means that nearly 13 million Americans

are now living with incomes below half

the poverty line. For a family of four,

existing with an income below half the

poverty line meant living on less than

$5600 for the entire year of 1986? for a

family of three this meant existing on

less than $4,550. Center on Budget and

Policy Priorities, supra, at 14.

19

at least part-time in 1986, equal to the

highest percentage since 1968.14

C. Increasingly, Rural Families

Have Fallen Into Poverty

The sharp increase in American

poverty has taken a heavy toll among

farmers and energy workers in North

Dakota and in rural America generally.

Throughout rural areas of the country,

increasing numbers of once-productive

residents find themselves without work,15

14 Center on Budget and Policy

Priorities, Washington, Gap Between Rich

and Poor Widest Ever Recorded , August

17, 1987.

15 U n e m p l o y m e n t has ri s e n

dramatically in recent years in the non

metropolitan counties of the United

States. In 1979, among the 2,400 non

metropolitan counties, only 300 had

unemployment rates higher than 9%, By

1985, that number had risen to 1,100,

nearly half the total.

20

without food16 and often without their

land.

The accelerated loss of farms in

1986 is easily documented using

Department of Agriculture (USDA) data.

Over the course of 1985, some 43,000

farms were lost, according to the

National Agricultural Statistics Service

count — 117 farms per day, or one every

10 minutes. Between the end of 1985 and

the end of 1986, an additional 60,000

farms vanished from the count, increasing

the average rate of loss to more than 165

farms per day, or one farm every 7

minutes — a staggering 40% increase over

the number of farms lost in 1985.

16 A 1986 study by Public Voice for

Food and Health Policy confirmed that a

growing number of rural Americans fail to

receive food stamps even though they are

eligible. From 1979 to 1983, the number

of rural poor not receiving food stamp

assistance increased by 32 percent, from

5.67 to 7.51 million persons.

Like the Kadrmases, these rural

families are most often hardworking,

formerly middle-class Americans who have

fallen into poverty as a result of

broader eccnomir conditions beyond their

individual control. These conditions are

reflected by traditional indicators:

declining net worth and land values,

declining prices for farm products,

increasing numbers of forced land

transfers, and swollen debt loads. The

impact has been felt across the board,—

in rural banks, small town retail

businesses and the agricultural implement

manufacturing industry. With one of

every five jobs in America related to

food production and distribution, the old

adage that economic downswings are both

22

farm-led and farm-fed has its roots in

economic reality.17

The crisis has been particularly

severe in the Middle West — in states

like the Dakotas, Iowa, Minnesota, Kansas

and Missouri — where agricultural and

energy workers have been hard hit. In

North Dakota alone, an estimated 36,000

children (or slightly less than one out

of five) now live in families with

incomes below the federal poverty

standard.18 * This is true despite the

fact that almost 60 percent of mothers

with children ages six to seventeen

17 In 1983 the median family income

for farm families was no more than three-

fourths that of non-farm families. The

farm resident poverty rate of 24 percent

far exceeded the poverty rate of 15

percent found for non-farm residents.

United States Census Bureau, Money Income

and Poverty Status of Families and

Persons in the U.S. 1983 (issued 1984)

(Series p. 60).

18 Children's Defense Fund, 1987

Data.

23

follow the pattern of Marsha Hall and

work outside the home.1^

Despite their growing numbers, the

rural poor have not become a potent

political force. Families like the

Kadrmases are a minority within the

Dickinson School District, unable through

the political process to alter the bus

fees which are an insignificant issue for

many of their more prosperous neighbors.

D. Poverty Demands Sacrifices From

Families like the Kadrmases

The foregoing poverty figures, while

disturbing in absolute terms, cannot

reveal the daily reality in which poor

families like the Kadrmases must survive.

A faiuxiy Iv^r.g at or below the poverty

level must do without many things which

families with an average income consider

to be "necessities " — a bed for each

19 Id.

24

family member, adequate clothing and

shoes, school supplies, or an occasional

movie. Technically, an income at the

official federal poverty level should

enable families to purchase the bare

necessities of life, since that was the

basis upon which the standard was

originally conceived. Yet an itemized

family budget drawn at that level falls

far short of adequacy. Poverty forces

families to make untenable choices among

their children's basic needs — for food,

for shelter, for health care, for a

minimally adequate education.

Food and nutrition is one area where

poor families are hardest hit. Because

the poverty level food budget for a

family of four is pegged at about $2.55

per person per day (85 cents per meal) ,

many poor people sometimes go hungry, or

buy their groceries at markets where day-

old bread and damaged canned foods are

sold at discounts. Yet no matter what

cost-cutting measures are adopted, a

poverty level budget can have serious

nutritional consequences, particularly

for poor children. The Physician Task

Force on Hunger in America estimated in

1985 that approximately 20 million poor

Americans experience hunger at some point

each month, and that malnutrition affects

almost 500,000 American children.20

Health care, an issue closely

related to adequate food and nutrition

standards, is another area where poor

families must make deep sacrifices.21

- 25 -

20 The Physicians Task Force on

Hunger in America. 1985 Report.

21 The record at trial revealed that

plaintiff Paula Kadrmas as well as former

plaintiff Marshall Hall had significant

debts for unpaid medical bills.

(Transcript, at 43 and 86 respectively.)

|I

26

The reason for the inadequate health care

which poor Americans so often receive is

quite simple — their lack of money. As

the unpaid medical bills of the Kadrmas

family reflect, most poor people simply

cannot afford private medical care, and

many are not covered by insurance.22

In general, then, poor families at

best have restricted access to proper

medical attention. The care they do

receive is often too late and of low

22 Our nation's employer-sponsored

health insurance system has never worked

well for millions of low-income families

or for irregularly employed workers like

Mr. Kadrmas. Thirty percent of all

employers who pay the minimum wage to

more than half their work force offer no

health insurance. Between 1979 and 1984,

the number of completely uninsured

Americans grew from 26.2 million to 35

million — a one-third increase in just

five years. Of all age groups, children

suffer most from weaknesses in the public

and private insurance systems. In 1984,

children made up one-third of America's

35 million uninsured persons. Children's

Defense Fund, A Children's Defense Budget

FY 1988: An Analysis of Our Nation's

Investment in Children (1987).

27

quality. Yet the relative need for

health care is greatest among those

groups — children and young mothers—

which form a disproportionate share of

the population in poverty. Nutritional

deficiencies in early childhood can

retard brain growth and school

performance. This early damage--

sometimes followed by frequent illness

and further malnutrition, as well as

crowded and unsanitary living conditions

— is exacerbated by a lack of regular

medical attention which may affect an

adult's ability to obtain adequate

employment.

Housing and utility costs represent

yet another complicating factor facing

poor families. The number of low-income

families paying more than one-half of

their incomes for rent and utilities rose

from 3.7 million to 6.3 million (or

nearly one-half of all low-income

households) between 1975 and 1982.23 In

the rural Midwest, where both housing and

energy costs have been rising, families

like the Kadrmases face a very difficult

time just meeting their basic shelter

needs. Plaintiff Kadrmas testified, for

example, that she paid $95 per month for

electricity and that propane fuel for

- 28 -

23 Federal poverty guidelines set

30% of income as the amount a family

should generally spend on rent or

mortgage payments. According to 1987

Census Bureau figures, however, of

families earning less than $7,000 last

year, 7 8% of them spent over this

proportion of their meager incomes on

housing. According to the same data, the

average family earning between $7,000-

10,000 a year spent 59% of its income on

housing.

According to a study conducted by

the Low Income Housing Information

Service, more than 8 million low-income

renters were in the market for the 4.2

million units at affordable prices in

1985. This gap — 4 million units — is

120 percent larger than it was in 1980.

Children's Defense Fund, A Children's

Defense Budget FY 1988 supra. 1987.

29

heat cost the family $277 every two

months. (Transcript, at 42).

"Necessities" for poor families and

their children do not end with food,

health care and shelter, however.

"Education," as this Court has noted,

"provides the basic tools by which

individuals might lead economically

productive lives to the benefit of us

aii>"24 yet to go to school costs money

— clothing, books, notebooks, pencils,

gym shoes etc. Even to go to church

costs money — some Sunday clothes,

carfare to get there, a little offering.

To belong to the Boy Scouts or Girl

Scouts costs money -- uniforms,

occasional dues, shared costs of a

picnic.

24 Plvler v. Doe. 457 U.S. 202, 221

(1982).