Pullman Standard Incorporated v. Swint Respondent's Brief in Opposition

Public Court Documents

October 6, 1980

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Pullman Standard Incorporated v. Swint Respondent's Brief in Opposition, 1980. 19aca4a5-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0cb0d428-4715-49b1-8581-30fbc216b3e9/pullman-standard-incorporated-v-swint-respondents-brief-in-opposition. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

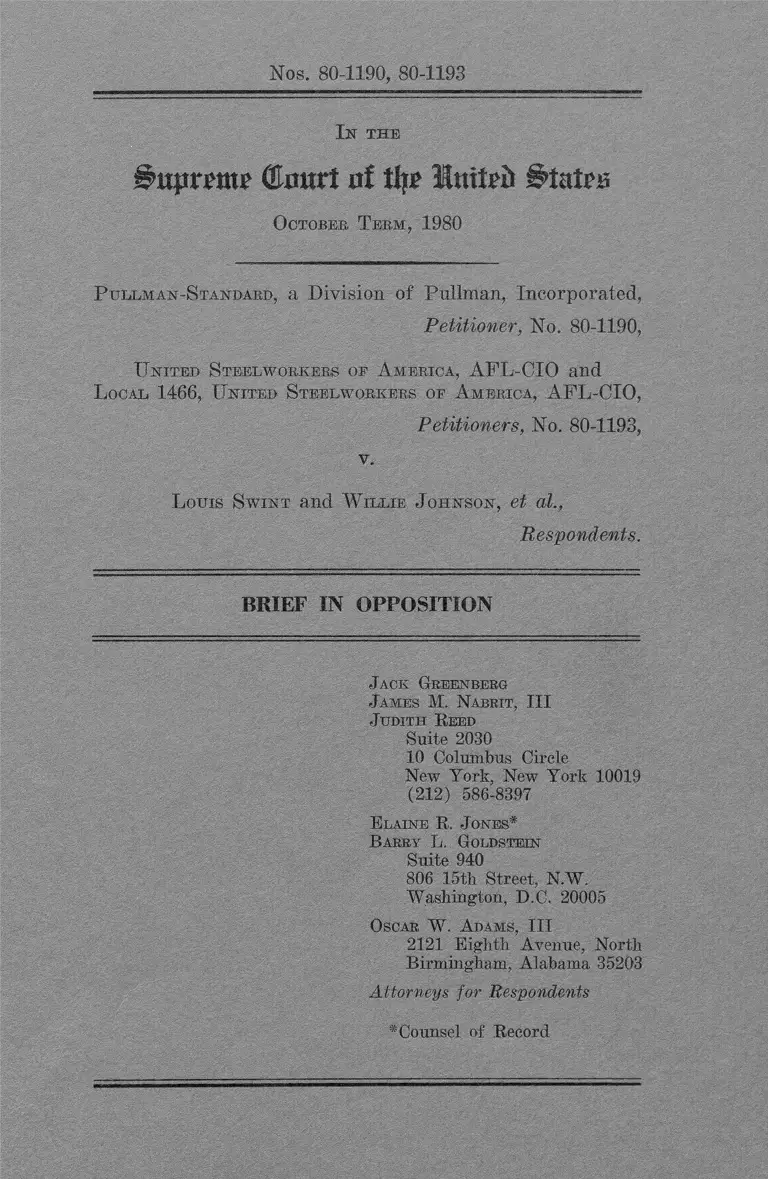

Nos. 80-1190, 80-1193

1st the

l$>u$jrpmp (Enurt of tty Intfpft £>tate

October T erm, 1980

P ullman-Standard, a Division of Pullman, Incorporated,

Petitioner, No. 80-1190,

Dotted Steelworkers of A merica, APL-CIO and

L ocal 1466, Dotted Steelworkers of A merica, AFL-CIO,

Petitioners, No. 80-1193,

Loins Sw int and W illie Johnson, et al.,

Respondents.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Judith Reed

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Elaine R. Jones*

Barry L. Goldstein

Suite 940

806 15th. Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

Oscar W. A dams, III

2121 Eighth Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Attorneys for Respondents

* Counsel of Record

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ......................................... i i

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ........................................ 1

REASONS FOR DENYING THE WRIT ........................... 6

ARGUMENT

I. IN HOLDING THAT THE SENIORITY SYSTEM

WAS UNLAWFUL, THE FIFTH CIRCUIT PRO

PERLY APPLIED THIS COURT'S DECISION

IN TEAMSTERS v. UNITED STATES ............... 8

Page

I I . IN REVIEWING THE DISTRICT COURT'S

DECISION, THE FIFTH CIRCUIT PROPERLY

DISCHARGED ITS FUNCTION UNDER RULE

52(a) IN A MANNER CONSISTENT WITH

THE DECISIONS OF THIS COURT AND WITH

THE DECISIONS OF OTHER CIRCUITS ........... 21

H I . IN CONCLUDING THAT THE COMPANY UNLAW

FULLY DISCRIMINATED IN THE SELECTION

OF SUPERVISORS, THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

FOLLOWED THE PRINCIPLES ESTABLISHED

BY THIS COURT IN A MANNER CONSISTENT

WITH THE APPLICATION OF THESE PRINCI

PLES BY OTHER CIRCUITS ........................... 29

CONCLUSION 34

- i i -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Asbestos Workers Local 53 v. Volger,

407 F.2d 1047 (5th Clr. 1969)...........

Baumgartner v. United States, 322 U.S.

665 (1943) ...........................................

Bostic v. Boorstin, 617 F.2d 871 (D.C.

Cir. 1980) ...........................................

Causey v. Ford Motor Co., 516 F.2d 416

(5th Cir. 1975) .................................

Dayton v. Bd. of Educ. v. Brinkman, 443

U.S. 526 (1976) ..................................

Duckett v. Silberman, 568 F.2d 1020

(2nd Cir. 1978) ..................................

East v. Romine, Inc., 518 F.2d 332

(5th Cir. 1975) ..................................

EEOC v. Chesapeake & Ohio Ry. Co., 577

F.2d 229 (4th Cir. 1978) ..................

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424

(1971) .................................................

International Brotherhood of Teamsters

v. United States, 431 U.S. 324

(1977) ..................................................

Kelley v. Southern Pacific Co., 419

U.S. 318 (1974) ..................................

33

22

29

22

24,27

28

22

28

7,33

passim

Page

25

- i i i -

Page

Keyes v. School District No. 1,

Denver, 413 U.S. 189 (1973) ................ 17

Kunda v. Muhlenberg College, 621 F.2d

532 (3rd Cir. 1980) ............................... 28

Mt. Healthy City Bd. of Educ. v. Doyle,

429 U.S. 274 (1977) ............................... 20

National Labor Relations Board v.

Pittsburgh S.S. Co., 337 U.S.

656 (1949) ............................................... 27

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1934)... 23

Pack v. Energy Research & Development

Administration, 566 F.2d 1111

(9th Cir. 1977) ...................................... 28

Silberhorn v. Gen. Iron Works Co.,

584 F.2d 970 (10th Cir. 1978) ............. 29

Sweeney v. Board of Trustees of

Keene State College, 604 F.2d

106 (1st Cir. 1979) ....................... 28

United States v. Board of School

Comm’rs, 573 F.2d 400 (7th C ir . ) ,

cert, denied, 439 U.S. 824 (1978) . . . . 17

United States v. General Motors, 384

U.S. 127 (1966) .................................... 23,25,26

United States v. Johnston, 268 U.S.

220 (1925) .............................................. 7

United States v. Oregon State Medical

Society, 343 U.S. 326 (1952) ................ 26

United States v. Parke, Davis & Co.,

362 U.S. 29 (1960) .................................. 25

United States v. U.S. Gypsum Co.,

333 U.S. 365 (1948) ............................ 7,22

United States v. Yellow Cab Co., 338

U.S. 341 (1949) ....................................... 26,27

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metro

politan Housing Development Corpora

tion, 429 U.S. 252 (1977) ...................... 17

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976).. 11

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Civil Rights Act of 1866, U.S.C. §1981 . . . 2

Rule 52(a) Fed.R.Civ.P. 6,23,25

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, 42 U.S.C. §2000e 2,8,14

- i v -

Page

Nos. 80-1190, 80-1193

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1980

PULLMAN-STANDARD, a Division of

Pullman, Incorporated,

Petitioner, No. 80-1190,

UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA, AFL-CIO

and LOCAL 1466, UNITED STEELWORKERS OF

AMERICA, AFL-CIO,

Petitioners, No. 80-1193,

v.

LOUIS SWINT and WILLIE JOHNSON, et a l . ,

Respondents.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The respondents, on their own behalf and on

the behalf of other black employees, fi led this

suit against Pullman—Standard (the "company ), the

2

United Steelworkers of America and its Local

1466 ("Steelworkers" or "USW") and the Interna

tional Association of Machinists ("IAM")— asser

ting violations of Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 (as amended 1972), 42 U.S. C. § 2000e

and the Civil Rights Act of 1866 U.S.C. § 1981.

Pullman-Standard and the Steelworkers have each

filed a petition for a writ of certiorari.

The d is t r ic t court found that there was a

"segregation of jobs [at the Bessemer plant of

Pullman-Standard] prior to March 1965 - which

certainly must be taken as an employment practice

and policy, whether or not ever formally approved

by company and union .... If all the jobs of a

department wre 'consigned1 to employees of the

same race, the department was, of course, totally

2 /segregated...." A 197.— Both courts below held

that racial segregation was practiced in every

conceivable aspect of employment at the Bessemer

1/ By pretrial order, leave was granted to add

YAM as a defendant for the purpose of enabling the

court to fashion a fu l l remedy. See App. A, one

of two apprendices to this Brief.

2/ "A" refers to the "Appendix to Petition for

Writ of Certiorari" submitted by Pullman-Standard.

plant.— The Fifth Circuit also ruled that

"racial segregation was extensively practiced at

Pullman-Standard [and] in the union h a l l . . . . " A

168. The pre-1965 discrimination covered assign

ments to jobs "in varying degrees [in] virtually

4/

every department." A 106-107.—

The major issues l i t ig a ted in the lower

courts concerned whether the discriminatory

- 3 -

3 /

3/ The district court made the following find

ings :

Bathhouses, locker rooms, and toilet fa c i l i

t ies were rac ia l ly segregated. Company

records - including employee rosters, in

ternal correspondence, records of negotiation

sessions, l i s t s of persons picketing -

included racial designations. In 1941 some

of the 'mixed' jobs even had different wage

sca le s fo r whites and b lacks . A l l of

the Company's o f f i c i a l s , supervisors and

foremen were white. Union meetings were

conducted with different sides of the hall

for white and black members, and social

functions of the union were also segregated.

(A 142.)

4/ In its petition (p. 6), the company misrepre

sents the district court's finding on discrimi

natory assignments by re ferr ing to its 1974

opinion. In i t s later opinion, which is the

subject of this proceeding, the court reversed its

position, see A 106-97.

assignments to production and maintenance jobs—

and discriminatory supervisory selection proce

dures continued during the period covered by this

lawsuit and whether the seniority system was

unlawful. T r ia l proceeded on three separate

occasions. The init ia l 1974 tr ia l lasted 16 days.

The district court concluded that the company and

unions had not engaged in unlawful practices A

1-44), but the Fifth Circuit vacated the decision

and remanded the case for further tr ia l proceed-

5/ Neither the company nor the union raise the

Tssue of post-Act discriminatory assignments in

their statement of questions presented. Neverthe

less, the company, in i t s statement of facts,

maintains that the Fifth Circuit wrongly concluded

that assignments were made on a discriminatory

basis after 1965. Co. Pet. 18-20. This is in

f l a t contradiction to i t s own admission that

during this period 47 whites and 3 blacks were

assigned to the Die and Tool (IAM) department, Co.

Pet 18. These statistics demonstrate the dis

crimination even more c lear ly than those upon

which the Fifth Circuit relies.^ They also

i llustrate the correctness of the Fifth Circuit's

holding that the district court, in the company's

own words, erred "in counting." Co. Pet. 20.

Compare A 108-09 with a 162-63; see also PX 2-8,

which support the Fifth Circuit's conclusion that

there was discrimination in assignment.

ings. A 45-99. A second t r i a l was held over

two days in February 1977. The district court

delayed ruling until after this Court rendered its

decision in International Brotherhood of Teamsters

v. United States, 431 U.S. 324 ( 1 9 7 7 ) , and then,

once again held that no unlawful pratices had been

committed. A 100-23. The plaintiffs moved for a

new tr ia l because Teamsters had altered the legal

standard for determining the validity of a sen

iority system and, accordingly, there had been no

evidence presented in the prior two trials rela

ting to the bona fides of the seniority system.

The d i s t r ic t court agreed (A 134-27), and an

evidentiary hearing was held. The hearing

on the Teamsters issue lasted less than a day

and oral testimony was presented by only two

6/witnesses.— The oral testimony was limited, but

extensive documentary evidence was presented

covering the institution, development and main

tenance of the seniority system from 1941 to the

present.

The district court found that the system was

"bona fide" and lawful even though it adversely

- 5 -

6/ See, infra, Argument, Pt. I I .

6

affects the employment opportunities of black

workers. A 128-52. The Fifth Circuit reversed

because " [ a ]n analysis of the to ta l i ty of the

facts and circumstances surrounding the creation

and continuance of the departmental system at

Pullman-Standard leaves us with the definite and

firm conviction that a mistake has been made"

[footnote omitted], A 170. The Fifth Circuit

also held that the lower court erred in concluding

that the company had not discriminated in the

assignment of employees and in the selection of

supervisors. A 153-79.

REASONS FOR DENYING THE WRIT

The questions presented by the Steelworkers

and Pullman-Standard challenge the Fifth Circuit's

ruling on sen io r ity .—̂ The company also chal

lenges the Fifth Circuit's ruling on the selection

of supervisors. The petitions are not due to be

granted because they present no conflict of

7/ One of the questions presented by the Steel

workers is cast in terms of Rule 52(a), Fed. R.

Civ. P.

7

decisions among the circuits— and because they

present no confl ict with decisions of this

9/Court.— Moreover, the decision of the Fifth

Circuit reaches a proper result on the facts

of this case. In any event, the Fifth Circuit

opinion raises no important or new issues of law

but rather applies this Court's decisions in

Teamsters v. United States, supra, and Griggs v .

Duke Power Co. , 401 U.S. 424 (1971), to a complex

factual situation (Sections I and I I I , i n f r a ) ^

8/ The company does not even assert that the

case presents a conflict of decisions. The

Steelworkers erroneously assert that the Fifth

Circuit's application of Rule 52(a) conflicts with

the application of the Rule by other circuits.

The Fifth Circuits's decision not only is consis

tent with decisions of other circuits but also

expressly follows a seminal decision of this

Court, United States v. U.S. Gypsum Co., 333 U.S.

364 (1948), interpreting Rule 52(a). See Section

II , infra.

9J As described in the Argument, the asserted

conflicts disappear when this Court's opinions are

properly applied to this case.

10/ Essentially petitioners ask this Court to

perform the appellate court function of "review-

ting] the evidence and discuss [ ing] specific

facts." United States v. Johnston, 268 U.S. 220,

227 (1925).

- 8 -

ARGUMENT

I.

IN HOLDING THAT THE SENIORITY SYSTEM WAS

UNLAWFUL, THE FIFTH CIRCUIT PROPERLY APPLIED

THIS COURT'S DECISION IN TEAMSTERS v. UNITED

STATES.

This Court in International Brotherhood of

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977),

neither condemned nor condoned a l l seniority

systems which perpetuate the effects of pre-Act

discrimination. I d . at 353-55. "To be sure,

§703(h) does not immunize a l l seniority systems,"

i d . at 353. Section 703(h) covers only "bona

fide" systems; it specifically excludes any system

in which differences in treatment are "the

result of an intention to discriminate because of

race____" 42 U.S.C §2000e-2(h) In ruling that

the system in Teamsters was protected by § 703(h)

the Court examined several factors: whether

the system "applies equally to a l l races," whether

i t is " in accord with the industry practice

and consistent with National Labor Relations

Board precedents," whether it had "its genesis in

rac ia l discrimination, " and whether " i t was

negotiated and has been maintained free from any

i l lega l purpose." 431 U.S. at 355-56; 346 n.28.

The Fifth Circuit applied these Teamsters factors

to the particular employment context presented at

, 12 /the Bessemer plant.—

1. Neutra l i ty . The undisputed evidence

establishes that the trad it iona l ly a l l -b lack

departments have the lowest median job classes at

the Company; the traditionally white departments

(with two exceptions) have among the highest

median job classes. The district court recognized

that the "No transfer with seniority carryover"

rule has the l ike ly e f fect of discouraging a

disproportionate number of black employees from

- 9 -

11/ Application of these factors by the Fifth

Circuit necessarily required a careful review of

the record. While respondents are reluctant to

burden this Court with a factual recital, both

petitions were riddled with statements that are

direct ly contrary to the record. Respondents,

therefore, are constrained to set forth the

record facts on the seniority system, which

appear in Appendix B to this b r ie f (App. B).

12/ The Steelworkers claim the the Fifth Cir

cuit's decision "robs § 703(h) .. of the content

which this Court . . . found that Congress meant to

give i t . " USW Pet. 23. On the contrary, the

Fifth Circuit followed the balanced approach which

this Court applied in Teamsters.

10

transferring, i f the relative economic desira

bi l ity of the departments is considered. A 134.

However, the Court f e l t i t "inappropriate" to

consider economic d e s i r a b i l i t y , and found the

system to be neutral because in effect, it locks

white employees out of the lower-paying black

departments to the same extent that it locks black

employees out of the higher-paying departments.

It disregarded the distinction that in Teamsters,

the employees who were "discouraged from transfer

ring . . . [were] not a l l Negroes and Spanish-

surnamed Americans [but] the overwhelming majority

[were] white." 431 U.S at 356.

Here the evidentiary facts are not in dis

pute and the Court of Appeals properly reversed

the district court, which committed legal error in

fail ing even to consider the inference of inten

tional racial discrimination raised by the fact

that the seniority system excluded blacks from

13/higher-paying departments.---- A 165-166, see

13/ The Steelworkers distort the Fifth Circuit's

statement that blacks were excluded by the first

Steelworkers' contract from "better jobs." USW

Pet. 16 n.9. The Fifth Circuit was referring to

the fact that the departmental system was estab

lished by the contract and that there were several

11

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S 229, 242 (1976)

( " I n ] ece s sa r i ly , an invidious discriminatory

purpose may often be inferred from the totality

of the relevant facts, including the fact, i f

true, that the law bears more heavily on one race

than another").

2. Rat iona l ity . I t is undisputed that

unionization and creation of the seniority system

resulted in the separation of two racially mixed

operational departments, the Die and Tool Depart

ment and the Maintenance Department, into four

separate seniority units, including three one-race

departments, A 136, A 166; App. B 9. The lower-

paying jobs consigned to blacks were included in

the Steelworkers unit while the higher-paying

13/ continued

all-white departments. The requirement that an

employee fo r f e i t seniority upon transferring

departments (A 131, 158), served as a bar to

transfer and thus excluded blacks from the better

paying jobs in the all-white departments. The

Steelworkers further erroneously criticize the

Fifth Circuit in stating that it wrongly referred

to a "no transfer rule." USW Pet. 17 n.9. The

Fifth Circuit did not "substitute" its judgment

for that of the district court, but rather ex

pressly adopted the lower court 's appropriate

characterization of the seniority for fe iture

provision. Compare A 134 to A 158.

12 -

jobs were included in the IAM unit. The district

court fa i led to consider the i r ra t iona l i ty of

dividing operational departments into separate

units because this "separation into d i f fe r in g

bargaining units was not merely, as in Teamsters,

'consistent with National Labor Relations Board

precedents, it was rather required by a

specific decision of the NLRB and the outcome of

the elections." A 140. The Fifth Circuit ruled

that the district court had once again erred as a

matter of law by refusing to consider whether the

division of these operational departments into

racially segregated seniority units was motivated

by race. A 166, A 169. Teamsters did not state,

as the d i s t r i c t court in fers , that whenever a

unit-system is certified by the NLRB it has an

14/imprimatur of rac ia l neutra l i ty . ---- Moreover,

14/ Teamsters did not involve, as this case does,

tFe development of separate bargaining units in a

specific plant. Teamsters involved the division

of jobs, over—the-road and city drivers, into

separate seniority units in a manner which was

consistently applied throughout the industry. In

this case, the IAM with the cooperation of the

Steelworkers and the company entered into a series

of maneuvers designed to accomplish one goal ■

the establishment at the Bessemer plant of a

one-race unit. App. B 6-8.

13 -

the company's and unions' creation of numerous

one- race departments was not justifiable by any

business reason; the only consistent thread

passing through the development of these depart

ments was race. App. B 9, 13.

3. Genesis. The seniority system had its

genesis in 1941 and 1942 when the IAM and the

Steelworkers sought and obtained bargaining

units. In its petition to the NLRB the IAM sought

to exclude Blacks from its bargaining unit. App.

B 4-5. As an example, the IAM petitioned for

inclusion of jobs such as crane operator, machine

operator and handyman when staffed by whites but

did not seek those jobs when staffed by blacks.

Moreover, immediately after certification the IAM

and the USW traded jobs along racial lines through

a 1941 inter-union agreement. Having completed

these rac ia l maneuvers, which resulted in an

all-white IAM bargaining unit, the unions, then

entered into collective bargaining agreements with

the company, which established a departmental

seniority system.— The district court erred as

15/ For evidence in the record which details the

racially motivated agreement, or "clarification,

between the USW and the IAM, see App. B 6-9; cf.

Co. Pet. 12. In what we believe to be an irres

ponsible manner,— "the 'A l ice in Wonderland'

14 -

a matter of law by ignoring the motives of the IAM

.16 /

in establishing an all-white bargaining unit——

and by failing to consider properly the 1941-42

genesis of the system. A 130, 142. The Fifth

15/ continued

quality of the Court of Appeals' inferences" - -

the Steelworkers criticize the Fifth Circuit's

conclusion regarding the 1941 transfer of jobs.

USW Pet. 18 n .11. The Steelworkers, however, do

not then refer to the 1941 trading of jobs

between the unions, but to a wholly separate 1944

transfer. App. B 7, 10.

16/ The district court found it "unnecessary" to

determine the motives of the IAM because "the

[steelworkers and the company] cannot be charged

with rac ia l bias in its response to the IAM

situation." A 145. The company and the Steel

workers make the same error. Co. Pet. 16; USW Pet.

8 n.3. The issue tried in the district court is

simply whether the seniority at the Bessemer plant

is bona fide, or more particularly, whether an

intent to discriminate entered into its creation

and development. 431 U.S. at 346 n.28.

I f the system had its genesis in discrimina

tion, then the protection of §703(h) does not

apply and thus a court properly may order the

removal of the adverse racial consequences of the

system. Teamsters v. United States, . supra, 431

U.S. at 349 (absent the protection of §703(h) the

seniority system f a l l s "under the Griggs ra

tionale") .

15

Circuit correctly stated that the "motives and

intent of the IAM in 1941 and 1942 are significant

in consideration of whether the seniority system

has its genesis in racial discrimination." A 169.

The Fifth Circuit properly relied upon the 1941

racially motivated agreement, in concluding that

The I AM manifested an intent to selec

t ive ly exclude blacks from its bargaining

unit NLRB ce r t i f ic a t ion considerations

notwithstanding.. . .That goal was u l t i

mately reached when maneuvers by the IAM

and USW resulted in an all-white

IAM unit. A 69-70. 17/

The unionization and the establishment of

a contractual departmental seniority system in

1941-42 not only resulted in the establishment

of the "seniority forfeiture" obstacle to transfer

to the then existing four all-white departments,

17/ Although stating that the "objective facts

are not greatly in dispute" (A 145), as they could

not be since the facts are set forth in NLRB and

company documents, the district court failed to

consider this racially directed transfer because

of its view of the applicable law. This inter

union swapping and maneuvering of jobs based on

the race of employees in those jobs regardless of

their functional relationship, contradicts the

assertion of the company that the unions had

no real choice". Co. Pet. 22.

16

but more importantly resulted in doubling the

18/

number of one-race departments. —

4. Maintenance. The racial consequences of

the seniority system were maintained and indeed

expanded by the parties to the collective bargain

ing agreements. Under those agreements, an

employee foreits accumulated seniority when he

voluntarily transfers from the bargaining unit of

one union to the bargaining unit of another. The

criterion used for seniority within the Steel-

. . . 19/workers bargaining unit---- was "departmental"

form 1942 through 1947, then "occupational" from

1947 through 1954, and then once again "depart

mental" after 1954. The 1954 seniority system at

18/ As a result of unionization and the sub

sequent inter-union agreement, five additional

one-race departments were created. Once again

the Steelworkers rely upon invective rather

than upon a review of the record when they

state that the Fifth C ircu i t ' s ruling that "a

substantial number of one-race departments

were established upon unionization" is "sheer

invention." USW Pet. 16 n.9. The court below

is correct. App B 8-9.

19/ As a result of the racial maneuverings by the

IAM and USW in the creation of their respective

bargaining units, and the negotiation of the

"no-transfer rule", App. B 3-9, n. 13, supra, a l l

the blacks at Pullman were concentrated in the

USW unit.

17

the Bessemer plant remained "virtually unchanged

throughout the next eighteen years of collective

bargaining." A 131, 158; App. B 15.

The Fifth Circuit properly concluded that the

"creation of the new departments in the years

subsequent to unionization involved continued

separation of the races." A 167. In examining

the "gestalt of the system" the district court

erroneously failed to examine the racial conse

quences of the departmental changes. A 140-41.

In an employment context where race receives

constant consideration in the allocation of jobs,

employee badge numbers, etc., when a series of

acts, such as the creation of new one-race depart

ments, adds to the discriminatory consequences

of the system then there is created an inference

of segregative intent. See, Village of Arlington

Heights v. M etropo l itan Housing Development

Corporation, 429 U.S. 252, 266-67 (1977); Keyes v .

School D istr ict No. 1, Denver, 413 U.S. 189,

207-08 (1973); United States v. Board of School

Comm1 r s , 573 F.2d 400, 412 (7th C i r . ) , c e r t .

denied, 439 U.S. 824 (1978).

The departmental changes which occurred in

1954 at the time of the switch from occupational

to departmental seniority show a clear pattern of

18

discrimination.— When the departmental struc

ture once again, in 1954, became c r i t i c a l in

establishing a worker's employment opportunity, as

in 1942-47, f ive brand new, one-race depart-

. • • 21 / *ments were created within the USW unit.— App.

B 13-14.

20/ Contrary to the representations of the union

and the company, respondents have not challenged

"departmental service,. . . as the measure of senior

ity", USW Pet. 5, nor a departmental system per

se, Co. Pet. 23-25. What respondents have chal

lenged on the facts of this case is the manner in

which the seniority system was established and

maintained at Pullman. Considerations of race

permeated the establishment of the bargaining

units, the creation of the departments and the

genesis and maintenance of the system.

21/ One of the five was the Janitor Department.

The Steelworkers assert that the separation of the

job of janitors, a "black" job, from the job of

watchman, a "white" job, occurred in 1952 (USW

Pet. 9), concluding therefore that the separation

did not harm the employment opportunities of

blacks, since an occupational seniority system was

in effect in the years 1947 to 1954. In fact, the

separation occurred, as the Fifth Circuit con

cluded (A 167), in 1954, just prior to and in

comtemp1 ation of, a sh i ft to a departmental

seniority system. See PX 2-7 which show the jobs

in the Safety department for 1947-52, PX 8

which shows the jobs in the Plant Protection

department in 1953 and PX 9 which shows the

janitors in an all-black Janitors Department and

the watchmen in an a l l -wh ite Plant Protection

department in 1954.

19

In conclusion, the Fifth Circuit correctly

determined that the district court had wrongly

applied the law, had failed to consider relevant

facts, and had made clearly erroneous findings of

fact. In applying Teamsters to the particular

22/facts at the Bessemer plant,— the Fifth Circuit

reached the proper legal conclusion — the sen

iority system was discriminatory and unlawful:

We consider s ignif icant in our decision

the manner by which the two s en io r i t y

units were set up, the creation of the

various a l l -white and a l l -b lack depart

ments within the USW unit at the time of

certification and in the years thereafter,

conditions of rac ia l discrimination which

affected the negotiation and the renegotia

tion of the system, and the extent to which

the system and the attendant no-transfer rule

locked blacks into the least remunerative

positions within the company. (A 171).

The company also asserts that a question

presented by this case is whether resolution of

the issue on bona fides of a particular seniority

system includes application of a "but for" test.

22/ Contrary to the St-eelworker' s assertions that

this case has affected the "seniority expectation

of over 2,000 employees . . . " (USW Pet. 26), this

plant was closed permanently in January 1981.

20

Co. Pet. 23. Nothing in Teamsters requires such a

test. Teamsters held that a court must inquire

into whether an intent to discriminate entered

into the adoption and maintenance of a seniority

23/

system.—"

In any event, the question presented —

"whether . . . a departmental seniority system would

have been adopted . .. even i f there had been no

racial aspect involved," Co. Pet. 25 — is not

posed by the instant case. The Fifth Circuit's

opinion and the position of the respondents, (see

n.20, supra), do not depend upon any per se

criticism of "departmental" seniority but rather

depend upon the specific application of seniority

23/ In Mt. Healthy v. Doyle, 429 U.S. 274 (1977),

this Court articulated "a rule of causation" that

had been utilized in "other areas of constitu

tional law [where] this Court ha[d ] found i t

necessary to distinguish between a result caused

by a constitutional v io la t ion and one not so

caused." Id . at 286. The Mt. Healthy standard,

developed for an individual case involving an

a l legat ion of a F irst Amendment v io lat ion is

inapposite to the analysis of whether a seniority

system is lawful under Title VII. This Court has

set forth the applicable standard in Teamsters and

the Fifth Circuit followed that standard. ~

- 21

to the gerrymandered departmental and unit struc

ture at the Bessemer plant.

24/

II.

IN REVIEWING THE DISTRICT COURT'S DECISION,

THE FIFTH CIRCUIT PROPERLY DISCHARGED ITS

FUNCTION UNDER RULE 52(a) IN A MANNER CONSIS

TENT WITH THE DECISIONS OF THIS COURT AND

WITH THE DECISIONS OF OTHER CIRCUITS.

The Court of Appeals, a fter reviewing the

record before it , concluded that:

24/ The company suggests that this Court grant

certiorari to consider the question of whether

T it le VII requires a showing of causality,

because there is a "current controversy" over this

question. Co. Pet. 25 n.24. In support of this

contention, the company cites three circuit court

decisions, i d . These cases, one involving a

"no-beard" policy, another involving an individual

a l leg ing reverse discrimination and a third

involving the alleged discriminatory discharge of

an individual who had lied on his application, are

inapposite. The question of whether those

courts applied proper Title VII standards to the

facts of those cases is not before this Court. In

any event, those opinions present no conflict

with the Fifth Circuit's opinion, nor are they even

related to the issue of whether the seniority sytem

is lawful.

- 22

An analysis of the totality of the facts and

circumstances surrounding the creation and

continuance of the departmental system at

Pullman-Standard leaves us with the definite

and firm conviction that a mistake has been

made.

A 170. This standard of review, articulated in

the seminal decision of this Court in United

States v. U.S. Gypsum Co., 333 U.S 365 (1948), is

the one used.

The Steelworkers attempt to convince this

Court that the Fifth Circuit's reasoning was based

on the standard articulated in East v. Romine,

Inc. , 518 F. 2d 332, 339 (5th Cir. 1975). It is

clear from the decision of the Court of Appeals

that this is not so. The Court of Appeals cites

East for the proposition, established long ago by

this Court, that the ultimate conclusion of

whether the entirety of the facts establishes a

statutory violation is an appropriate determina

tion for an appellate court to make. Baumgartner

v. United States, 322 U.S 665, 670-71 (1943),

followed in Causey v. Ford Motor Co. , 516 F.2d

416, 420 (5th Cir. 1975); cf. USW Pet. 21 n. 14.

Thus the Court of Appeals properly notes that

while appellate courts can overturn subsidiary

facts only under the clearly erroneous standard,

- 23 -

they can, and indeed are under a duty to, make an

independent determination of whether a violation

25/

of Title VII has been established.---- * As this

Court has recently noted, "the ultimate conclusion

by the tr ia l judge, [of violation of the Sherman

Act ] , is not to be shielded by the 'c lea r ly

erroneous' t e s t . . . . " United States v. General

Motors, 384 U.S. 127, 142 n. 16 (1966)— ^

Not only did the Court of Appeals follow the

correct standards under Rule 52(a) , but the

d is t r ic t court here made numerous errors of

25/ See, Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S 587, 589-90

(1934): "That the question is one of fact does not

relieve us of the duty to determine whether in

truth a federal right has been denied."

26/ The Steelworkers criticize a number of the

conclusions reached by the Court of Appeals, see,

e.g., USW Pet. 21 nn.9, 10, and 11. As we have

shown earlier, their criticisms, based on distor

tions of the record, are totally unwarranted, as

each of the Fifth C ircu i t ' s conclusions had

abundant factual support in the record and was

reached through an application of the correct

lega l pr incip les . See supra nn.13, 21, 23,

26.

- 24 -

law 27/ and, as the Court of Appeals correctly

27/ The d is t r ic t court 's erroneous view of

controlling legal principles manifested itse lf in

several distinct ways, including the following:

( i ) The d is t r ic t court 's f a i lu re , indeed

refusal, to consider the motives of the IAM with

regard to either genesis or maintenance, see supra,

p .13-17, and n .16;

( i i ) the district court's determination that

whether the 1941-42 or 1954 period of time was

selected for consideration of the genesis factor

was inconsequential. See A 142; cf. App. B 3-9, 13;

( i i i ) the district court's apparent view that

NLRB certification somehow insulated the system

from a finding of irrationality; see supra, p. 12;

( iv ) the district court's failure to consider

the seniority system's exclusion of blacks from

higher-paying departments, see supra p. 10 and n.13

(v) the district court's failure to consider

the creation and maintenance, through the collec

tive bargaining process, of an ever-increasing

number of one-race departments, see supra pp. 15,

18;

(v i ) the district court's failure to consider

the racial consequences of later changes to the

seniority system, see supra, 16-18;

As did the district court in Dayton v. Bd. of

Educ. v. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526, 535-36 (1979),

the district court "ignored the intentional main

tenance" of a discriminatory seniority system.

25

noted, Rule 52(a) has no application "where

findings are made under an erroneous view of

controlling legal principles, the clearly erro

neous rule does not apply, and the findings

may not stand." A 178 n.6. See United States v .

Parke, Davis & Co. , 362 U.S. 29, 44 (1960);

United States v. General Motors, supra, 384

at 142; Kelley v. Southern Pacific Go. , 419 U.S.

318, 323 (1974).

In an attempt to bo lster their argument,

petit ioners claim that the d is t r ic t court 's

conclusion was reached only after listening to

"weeks of testimony." USW Pet. 16. As discussed

in the Statement of the Case, the district court

granted p la inti f fs ' motion for a new trial limited

to the Teamsters issue. A 126. The hearing on

that issue lasted less than three hours, during

which time the district judge heard the testimony

28/of only two witnesses.---- In other words, i t

28/ These witnesses were called by respondents.

Mr. Samuel Thomas, a black employee at the company

since 1946, testified as to segregation in seating

at the union hiring hall and at union sponsored

social ac t iv i t ie s (Tr. 18-19), and the rac ia l

composition of union o f f ice rs and negotiating

groups (Tr. 23-24). The other witness, Mr. Willie

James Johnson, also a long-time black employee,

testified regarding the segregated seating (Tr.30),

segregated faci l it ies at the company and union

- 26 -

"was essentially a 'paper case.'" United States v.

29/General Motors, supra, 384 U.S at 142 n.16——

The Steelworkers' reliance, therefore, on United

States v. Yellow Cab Co., 338 U.S. 341 (1949) and

United States v. Oregon State Medical Society, 343

U.S. 326 (1952) is misplaced. In both of those

cases the resolution of issues of intent turned

"peculiarly upon the credit given to witnesses by

those who see and hear them." 338 U.S. at 342.

This Court reaffirmed this view in Oregon State

Medical Society, cited by the Steelworkers, who

chose to eliminate a very relevant portion of the

quote, which it reads in fu l l as follows:

28/ continued

ha l l (Tr. 30-31), r ac ia l identity of various

International representatives (Tr. 30), as well as

the handling of grievances regarding rac ia l

discrimination. (Tr. 32-33). Neither witness was

subjected to extensive cross-examination and

neither petitioner attacks the c red ib i l i ty of

these witnesses.

29/ The documentary evidence consisted of over

TOO exhibits for plaintiffs (respondents) and 27

for defendants (petitioners).

- 27

There is no case more appropriate for ad

herence to [Rule 52 (a ) ] than one in which

the complaining party creates a record of

cumulative evidence as to long-past trans

actions, motives, and purposes, the effect

of which depends largely on credibility of

w i t n e s s e s . 341 U. S . at 332 ( emph as i s

added).

Unlike the "ordinary lawsuit" that "depends for

its resolution on which version of the facts in

dispute is accepted by the trier of fact." U.S.

v. Yellow Cab Co. , 338 U.S at 341, quoting from

National Labor Relations Board v . v, Pittsburgh S.S

Co., 337 U.S. 656 (1949), this case depends upon

the correct application of Teamsters principles

30/to facts culled from documentary evidence.----

Here, the Court of Appeals performed "its unavoid

able duty . . . and concluded that the Distr ict

Court had erred. Dayton v. Bd. of Educ■ v .

Brinkman, supra 443 U.S. at 534 n.8.

30/ The Fifth Circuit has not held that the

standards of Rule 52(a) do not apply to a review

of findings on discrimination purpose, as the

Steelworkers assert. USW Pet. 22. Further,

there is no conflict between the Fifth Circuit and

- 28

30/ continued

any other circuit over the applicable standards,

as the Steelworkers imply. Id . Here, the dis

trict court failed to consider properly documen

tary evidence because of its erroneous view of

controlling legal principles, and the Court of

Appeals correctly reversed. The cases cited by

the Steelworkers ( id . ) did not involve crucial

errors of law. In addition, those cases concerned

individual discharge and promotion claims, that

revolved around the testimony of witnesses,

thereby invoking particularly the requirement of

Rule 52(a) that "due regard shall be given

to the opportunity of the tr ia l court to judge the

credibility of witnesses." See EEOC v. Chesapeake

& Ohio Ry. 577 F.2d 229, 233 (4th Cir. 1978) (de

pended on credibility of witness' testimony and

the inference to be drawn from sharply conflicting

evidence); Kunda v. Muhlenberg College, 621 F.2d

532, 544 (3rd C ir. 1980) (d is t r ic t judge had

opportunity to observe principal w itnesses);

Duckett v. Silberman, 568 F.2d 1020, 1023 (2nd

Cir. 1978) (credibility a major factor) and re

viewing court noted, t r ia l judge was there, "we

were not"); Sweeney v. Board of Trustees of Keene

State Co llege . 604 F .2d 106, 109 n .1 ( " . . . t h e

opportunity for first-hand observation may be

especially important in [a case] such as this,

. . . " but court goes on to note it would attempt to

"detect infection from legal error . . . . " ) ; Pack v.

Energy Research & Development Admininstration, 566

F.2d 1111, 1113 (9th Cir. T9TT) (involving opinion

29

III .

IN CONCLUDING THAT THE COMPANY UNLAWFULLY

DISCRIMINATED IN THE SELECTION OF SUPERVISORS,

THE FIFTH CIRCUIT FOLLOWED THE PRINCIPLES

ESTABLISHED BY THIS COURT IN A MANNER CONSIS

TENT WITH THE APPLICATION OF THESE PRINCIPLES

BY OTHER CIRCUITS.

The district court found that respondents had

made out a prima facie case of discrimination with

respect to promotions to supervisory positions,

based on the s ta t is t ic s presented at t r i a l :

At the time of t r ia l only some 10% of

Pullman's sa laried foremen were black, a

figure which is substantia lly below that

expected from the labor market - which ranges

from 25 to 35% black, depending on the age

group and area selected — or from Pullman's

own work force - which ranges from approxim

ately 45 to almost 50% black, depending upon

the time selected.

30/ continued

testimony of p la in t if f 's qualifications; Bostic v.

Boorstin, 617 F.2d 871, 875 (D.C. C i"r"! 1980)

(d istrict court required to resolve conflict in

expert testimony); Silberhorn v. Gen. Iron Works

Co. , 584 F . 2d 970 (10th Cir. 1978) (d is t r ic t

court required to evaluate testimony of co-workers

and supervisors regarding p la in t if f 's behavior).

- 30 -

A 110. The district court had also previously

found that " [ s ] elect ion of foremen has been

largely a matter of subjective evaluation by an

all-white group of supervisors, A 26. The

Court of Appeals, in its earlier opinion, agreed

with the district court, holding:

The appointment of supervisory personnel at

Pullman-Standard is done to ta l ly subjec

tively. There are no established criteria

for selection of new foremen. . . . . In 1966,

the first black was promoted to one of the

431 existing sa lar ied foreman positions.

Four years later, there were only nine black

salaried foremen while there were 151 white

foremen. At the time of t r ia l , there were 13

departments in which blacks had never been

offered either salaried or temporary forman

positions. Since 1966 and until the time of

this tr ia l there were at least 59 salaried

formen vacancies. Only 12 of those were

f i l led by blacks.

The company recognizes that classwide dis

crimination in promotion for foremen has been

shown Co. Pet. 25; however, the company contends

that the Court of Appeals erred in concluding that

the company had failed to rebut the prima facie

case. The company does not assert that the

decision of the Court of Appeals conflicts with the

decisions of this Court or with those of other

circuits; rather, the company asserts that the

Court of Appeals erred in two ways. First, by

"refusing" to take into account evidence regarding

- 31

black refusals of supervisory positions. Second,

by inquiring into whether the company had justi

fied its practices under the business necessity

doctrine. Co. Pet. 25-29. The company's petition

is not due to be granted on either of these

issues, because the firs t is not presented by the

decision of the Court of Appeals, or the record in

this case, and the second is already settled by

decisions of this Court.

The F ifth Circuit did not state, as the

company maintains, Co. Pet. 26, that refusals by

black workers of company promotional offers could

not be taken into account in rebutting a prima

facie case of discrimination. In fact, the Fifth

Circuit considered this evidence and concluded

that, under the circumstances of this case, since

black refusals of promotions were closely tied to

the "very discrimination which the class members

seek to eliminate," the defendant had failed to

rebut the prima facie case. A 176.

The evidence established, and both courts

found, that the company's practice was to make

promotions to temporary foremen of any given

department from employees already within that

department. A 113 and A 171. The company now,

for the f i r s t time, terms such a practice an

- 32 -

"imaginary requirement." Co. Pet. 29. Yet the

company admits that only 3% of the promotions for

31/

foremen are not from the same department. Id .

Both courts below then considered whether this

practice was ju s t i f ie d by business necessity

32/

(A 113 and A 173).— The Court of Appeals held

31/ This figure may be compared to the finding

of the district court that " [o ]f the 415 monthly

promotions reported from January 1969 through May

1974, 403 - or 97% - were appointments of a

person when in the department." A 122 n.18.

Apparently the company would require a finding

that a l l , or 1 0 0%, of the promotions were from

within the department, before it would be appro

priate to use the term, "practice."

32/ The district court held that " [t ]he restric

t ion of such temporary promotions to persons

working in the department is a bona fide occupa

tional qua li f ica t ion , ju s t i f ie d by business

necess ity ." A 113. Because of the d is tr ic t

court's intermingling of two separate and very

distinct Title VII defenses, the Court of Appeals

discussed the distinction between the two, cor

rectly concluding that the bona fide occupational

qua li f ic a t ion exception was not applicable to

cases involving race discrimination. A 174.

33

that in order for the company to rely on a proce

dure having a disparate impact on blacks, it must

show that the procedure is justified by business

necessity. A 174. In so holding, the Court of

Appeals was following the principles enunciated by

this Court in Griggs v. Duke Power Co. , 401 U.S

424 (1971). 33/

33/ See also Teamsters, supra, 431 U.S. at 349.

The company asserts that the business neces

sity defense is applicable only in cases involv

ing a "test or screening device." Co. Pet. 29.

This assertion is plainly wrong. As this Court

noted in Teamsters "[o]ne kind of practice

' f a i r in form, but discriminatory in operation'

is that which perpetuates the effects of prior

discrimination." 431 US. at 349, citing as an

example the nepotism requirement at issue in

Asbestos Workers Local 53 v. Vogler, 407 F. 2d

1047 (5th Cir. 1969). Id at n.32. Similarly, the

requirement, at issue in the courts below, that a

person have worked in the department prior to

being promoted — in effect a kind of "grandfa

ther clause" — automatically precluded the

consideration of blacks who but for past d is

crimination, would have worked in a greater

number of departments.

- 34 -

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the petitions for

a writ of certiorari should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, I I I

JUDITH REED

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

ELAINE R. JONES*

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

806 15th Street, N.W.

Suite 940

Washington, D.C. 20005

OSCAR W. ADAMS, I I I

2121 Eighth Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Attorneys for Respondents

*Counsel of Record

APPENDIX A

COURT: U.S. District Court, N.D. Ala., Sou. Div.

CASE : Swint, et al. v. Pullman-Standard, et al., CA 71-P-955

ORDER: Supplemental pre-trial conference held June A, 197^.

1. Counsel. The following counsel were present: For

plaintiffs, U.'W. Clemon; for defendant Company, C. V. Stelzenmuiler;

a n d for defendant Steelworkers Union, John C. Falkenberry.

2. Class Action. The parties have made known certain facts

to the court and have agreed that such facts may be considered by

the court without formal hearing otherwise required under Rule 23.

On the basis thereof, the court finds and concludes that the

prerequisites of Rule 23(e) and 23(b)(2) are satisfied and that

this action may hereafter be maintained on behalf of all black

persons who are now or have (within one year prior to the filing

of any charges under Title VII) been employed by defendant

Company a3 production or maintenance employees represented by the

United Steelworkers. The court concludes that individual notifica

tion of class members is unnecessary in this action under Rule

23(b)(2) but that it would be appropriate for a general notification

of the pendency of this litigation to be posted at the premises of

the Company. Counsel for the parties shall attempt to draft such

a notification and in the event of disagreement the same shall be

presented to the court for its approval.

3. Parties. Leave is hereby granted to the plaintiffs to _

add as additional party defendant (insofar as the relief requests-

may involve or infringe upon the provisions of such Union's

collective bargaining agreement with the Company, it being noted

however that no request for monetary relief is being sought against

said Union) the aDpropriate entity of.the International Association

of Machinists. Leave is also granted for the Intervention as a

party plaintiff of an employee by the name of Humphrey for the

presentation of his claim under Section 1981 with respect to his

discharge and subsequent reinstatement without back pay.

It. Issues. The following charges are made by the plaintiffs

as violations of either Title VII or of Section 1981:

(a) That a system of departmental seniority, even with

changes made pursuant to a corrective action program with

the Department of Labor, nevertheless perpetuates the effects

of past discrimination in the assignment of black employees

to generally less desirable departments. This issue subsumes

the following assertions by the plaintiffs:

The transfer provisions under the agreement with the

Department of Labor apply to only four departments;

the transfer rights which are granted under such plan

are inadequate by reason of the failure to provide red-

circle rates and by reason of the restriction to a

single exercise of such rights; and such rights of

transfer do not apply to Jobs In the machine shop

represented by the IAM. (The issue relative to the

machine shop may have to be severed for subsequent

trial depending upon the Joinder, service, and availa

bility and readiness of the IAM with respect to the

trial date already scheduled.)

( b ) The Company has dlscrlmlr.atorily made assignments

of functions to persons serving in the same Job ciassirica-

tlon based on race and has discrimlnatorily assigned p

on the basis of race to "lateral'' Job classifications having

the sam e J o b c l a s s . FILED IN CLERK'S OFFICE

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

JUH5 1974

W ILLIAM . E. DAVIS

CLERK, U. S. OISTRICT COURT

■v.------7 OlFUTT CUXMtf

(c) The Company has dlserimlnatorily failed to

promote black production and maintenance employees to

supervisory and managerial positions.

(d) As individual, non-systemic, claims, the Company

has discharged the plaintiff Swlnt in violation of Title VIZ

or Section 1981 and has discharged (without giving back pay

on reinstatement) the potential Intervenor Humphrey in

violation of Section 1981.

The plaintiffs seek back pay or other monetary relief incident

to the foregoing claims of discrimination; but such issue is

severed for trial, if necessary, at a subsequent date. The plain

tiffs, in view of proposals made by the defendants in conference,

do not intend to challenge the practice by which dally assignments

and vacancies have not been publicly posted; but reserve the right

to present such an issue at trial if the conference proposals by

the defendants prove to be unsatisfactory.

The defendants deny the several charges of discrimination set

out above and in addition assert defenses in part based upon

applicable statutes of limitation and the effect of arbitration

awards.

5. Discovery ■ The parties are given leave to proceed with

further discovery provided the same be completed at least ten days

prior to trial. The parties shall at least ten days prior to trial

exchange a list of witnesses and documents which they anticipate

utilizing at trial.

Done this the V _ ■ day of June, 1971•

APPENDIX B

APPENDIX B

THE SENIORITY SYSTEM IN

EFFECT AT PULLMAN-STANDARD

INTRODUCTION

The seniority system at Pullman involves the

Company and two bargaining units - one represented

by the IAM and the other represented by the USW.

The system at Pullman-Standard was part and parcel

of the rac ia l discrimination practiced at the

Bessemer plant; it was negotiated, adopted and

maintained with an intent to discriminate.

At the time Pullman-Standard was organized in

1941, considerations of race permeated the manner

by which the two bargaining units were set up.

With the active cooperation of the USW and the

agreement of the company, the IAM sought and

achieved an a ll-w h ite bargaining unit. The

efforts of the parties to the collective bargain

ing process resulted in substantially increasing

the number of one-race departments that had

existed at the plant prior to unionization. With

the negotiation of the "no-transfer" rule, the IAM

was able to maintain its all-white status, with

blacks being concentrated in the USW bargaining

unit.

- 2 -

The departments in the USW bargaining units

were thereafter manipulated so that even the

potential for blacks to move into better jobs in a

given department was removed, these manipulations

occurring s ign if ican t ly enough, on the eve of

changes in the seniority criteria. The evidence

in the record demonstrates that when the seniority

cr ite r ion was broadened, i . e . "departmental,”

departments were less racially mixed, due to the

creation of one-race departments, and therefore

less likely to offer even potential opportunities

for blacks to exercise seniority rights vis-a-vis

whites in higher paying jobs or whites with less

seniority. Similarly, when the seniority c r i

terion was narrowed, i . e . , "occupational" (1947-

54), departments were likely to be more racially

mixed, the limitation of opportunities for blacks

to exercise seniority rights in better jobs was a

fait accompli since an employee held seniority

only within the occupation in which he worked. It

is clear, then, that the structure of the opera

tional departments was manipulated along racial

lines, depending on how broad or restrictive the

seniority criterion.

The seniority system in effect at Pullman-

Standard' s Bessemer plant may be viewed as having

three distinct phases: the 1941-42 in it ia l organ

3

ization of the company and negotiation of the

system; the 1944-54 changes in the system and

departmental structure; and the 1954 return to

departmental sen iority . The discussion that

follows details the actions taken by the parties

to the collective bargaining process during each

of those time periods.

1941-42: UNIONIZATION AND GENESIS

OF THE SENIORITY SYSTEM

Pullman commenced operations in Bessemer,

Alabama in 1929. At that time, and for the

next 12 years, there were no recognized unions at

Pullman. Prior to unionization, the company was

divided into 20 departments: 5 one-race depart

ments (4 of which were all-white)- and 15 were

1/ These figures, based on the record, stand

in stark contrast to those set forth by the

Steelworkers, see, e .g , USW Pet. 7 n.2. The

Steelworkers' analysis of departmental changes

during the period from 1941-1954 (USW Pet. 6 - 8 ),

rests in large part upon a chart created by the

district court for the purpose of describing the

departmental structure in 1965. The 1965 chart,

earlier criticized for other reasons by the Fifth

Circuit (A 55-58), just cannot explain departmen

tal changes which occurred over the preceeding 20

years and reliance on that chart resu lts in

numerous errors in the Steelworkers' analysis.

- 4 -

racially racially mixed.— PX 1, 109.

The NLRB c e rt i f ic a t io n and subsequent " c la r i f i

cation"

In 1941, the IBEW, I AM, and USW, a l l of

which had filed representation petitions, jointly

participated in a representational hearing. PX 13

A151, 178.

The I AM, while claiming to represent a unit

consisting only of machinists and their helpers

and apprentices at Pullman, in fact sought recog

n ition on behalf of employees in occupations

which cannot properly be regarded as "machinist"

occupations, e .g . , cranemen, welders, wheel

2/ The four all-white departments were: Lumber

Yard, Welding, Template, and Plant Protection

(job of "Janitor", not included in this department

but in racially mixed "Superintendent" Depart

ment). The a l l -b la ck department was the Truck

Department. A-150 n.12; PX 109. The racially

mixed departments included the following: Die and

Tool, Forge, Maintenance, Paint, Press,Punch and

Shear, Shipping Track, Steel Construction, Steel

Erection, Steel Miscellaneous, Stores, Superin

tendent, Wheel and Axle, Wood Erection, and Wood

Mill.

f i t t e r s , tool grinders, ax le -f in ish e rs , and

pipefitters. Moreover, the IAM did not seek to

include in their unit machinist-related occupa

tions (e .g ., machine operators, punch and shear

operators) in ra c ia l ly mixed departments. PX

13, 14, 112. In its petition to the NLRB the IAM

sought to exclude blacks from its bargaining

3/unit.—

- 5 -

3/ For example, the IAM petitioned for inclusion

of the job of handyman in the racially mixed Die

and Tool department, where it was staffed by

whites, but not in the racially mixed Maintenance

Department where it was staffed by blacks; peti

tioned for inclusion of crane operators in the Die

and Tool Department and racially mixed Wheel and

Axle department, where the job was staffed by

whites, but not in the ra c ia l ly mixed Steel

Miscellaneous department where it was staffed by

blacks; and petitioned for machine operator jobs

in departments where the job was staffed by

whites, but not in departments where i t was

sta ffed by blacks. PX 1, 13, 109. Moreover,

in the racially mixed Die and Tool Department, the

IAM sought recognition on behalf of every single

production and maintenance job except those

occupied by blacks. Id.

. • 4/On November 19, 1941 the Board cert i f led—-

the I AM as the bargaining agent for a particular

group of workers in the Die and Tool department,

Welders, Wheel and Axle, and Truck departments,

and Air Brake department; and USW Local 1466 as

the co llec t ive bargaining agent for a l l other

production and maintenance employees of the

Company. PX 14, 15. However, as a resu lt of

the NLRB November 1941 certification of the IAM

unit, several jobs staffed by blacks were included

within the jurisdiction of the IAM. For example,

the November certification of the IAM unit in

cluded the all-black Truck department, and the

all-white Wheel and Axle departments, because the

evidence demonstrated that these departments

performed a coordinated function and were opera

tionally treated as one department. PX 13, pp.

29-30, 89, 144-48.-/

- 6 -

4/ The IBEW was certified to represent elec

trical workers and powerhouse operators. PX 15.

5/ Also included in the IAM unit at the time of

T n it ia l c e r t i f ic a t io n in November 1941 were

jobs staffed by blacks in the racially mixed Die

and Tool departments and the racially mixed Wheel

and Axle Department. PX 15, 109.

7

However, the racial integration of the I AM

unit was "corrected," and a "clarification" made,

by a letter agreement, dated December 19, 1941,

reached by the IAM, the Steelworkers and the

6 /company.— A 151 n. 13 By this agreement be

tween the parties , entered into immediately

a fter NLRB c e rt i f ic a t io n , the a l l -b lack Truck

Department and a l l other jobs staffed by blacks,

certified by the NLRB to be in the 1AM unit, were

given to the USW. As a further provision of the

agreement the USW ceded to the I AM the jobs held

by two white employees which had been certified in

it s bargaining un it.—■ (Compare PX 1, 15, 17

pp. 14-16, 109, CX 14.)

6 / The agreement provides that the NLRB s

Tecision "is . . . in minor respects inadvertent in

the c la s s i f ic a t io n of employees as has been

recognized both by the company and by the respec

tive bargaining agencies."PX 17, pp. 14-16.

7/ In total, the IAM swapped 24 black employees

Tor 2 whites from the USW. The I AM gave up no

whites. PX 1, 15, 17, 109.

- 8 -

In short, the IAM gave its black members to

the USW and the USW, in turn, gave two of its

white members to the IAM, with the acquiescence of

the company and of the Board, thereby maintaining

the al 1-white—/ nature of the IAM despite the

NLRB certification.

The increase in the number of one-race depart-

ments after unionization

Efforts to exclude blacks from the IAM unit

and the subsequent swapping of jobs between the

bargaining units (USW and IAM) in December of 1941

resulted in doubling the number of one-race

departments which existed prior to unionization.

81/ The evidence in this record f lat ly contra

dicts the company's contention that blacks were

included in the IAM at the time of unionization

in 1941-42. Co. Pet. 12. In support of this

contention, the company makes reference to the

welder-helper job, a job in the IAM unit. This

record shows 3 blacks in the position of welder

helper in 1944. PX 2, 63. There were no blacks

in the job when the company was organized and the

seniority system was adopted. PX 1, 13, 15, 17,

109. The uncontroverted evidence is that the IAM

unit was an all-white unit upon unionization of

the company, and subsequent c la r i f ic a t io n , in

1941-42. PX 1, 17, 109.

- 9 -

As a resu lt of unionization and the subse

quent inter-union agreement, see p. 7, supra, five

. . 9/

additional one-race departments were created.—

In addition to dividing ra c ia l ly the Die and

Tool department leaving the all-black remnant in

the USW, as well as carving out an an all-white

segment from the ra c ia l ly mixed Maintenance

department, the IAM and USW also converted a

racially mixed department, Wheel and Axle, into a

one-race all-white department, by their December

1941 agreement or "c larification ."— ^

9J The five departments were as follows: ( i ) The

all-black Die and Tool (CIO) department repre

sented by the Steelworkers; the all~white IAM

departments, including ( i i ) Die and Tool (IAM),

( i i i ) Maintenance (IAM), ( iv ) Wheel and Axle, and

(v) Air Brake. PX 1, 13, 17, 109.

10/ Prior to unionization and even after the

in it ia l NLRB certification in November 1941, PX

15, the Wheel and Axle department had been ra

cially mixed. PX 109. However, the inter-union

agreement caused the Wheel and Axle department to

become an a ll-w h ite department within the IAM

unit. PX 1, 13, 15, 17, 109.

- 10 -

1944-54: THE MAINTENANCE OF A DISCRIMINATORY

SENIORITY SYSTEM

The 1944-46 manipulations

In 1944 the IAM ceded to the USW the depart

ments in its bargaining unit, with the exception

of the all-white Die and Tool (IAM) and all-white

Maintenance (IAM), two departments which have

remained in the IAM since unionization. The

all-white Wheel and Axle-^-^ all-white Air Brake

12/

Pipe—- and the recently racially mixed Welding

11/ Although racially mixed prior to unioniza

tion, the Wheel and Axle department continued to

be all-white upon its return to the USW unit. PX

2, 15, 17, 109.

12/ The history of the a ll -w h ite A ir Brake

department is instructive when looking at this

particular department system. Prior to union

ization the three jobs which comprised this

department were located in two ra c ia l ly mixed

departments. PX 13, p. 85; PX. 17, pp. 14-15.

In 1941, these jobs were assigned to the IAM

where they formed an all-white department. Then

in 1944, the department was transferred back to

the Steelworker unit, PX 19, pp. 23-24, disbanded,

and its jobs, pipefitter and pipefitter helper,

were placed in the racially mixed Steel Erection

department where they remained during the period

when occupational seniority was used. Finally,

in 1954, when departmental seniority returned to

Pullman, the white-only Air Brake department was

re-established. PX 9.

11

departments were ceded by the IAM to the USW in

13/

1944.—

An all-white Powerhouse department, which had

been created and represented by IBEW at the

organization of the company, was disbanded in

1946; those jobs were then placed in a racially

mixed department represented by the USW, A

14/151, PX 2.—

13/ Regarding the rac ia l composition of the

1944 transfer of employees from the IAM to the

USW unit, the USW states categorically "SO were

white and 20 were black." USW Pet. 11, 18 n . l l .

This assertion is not supported by the evidence in

this case which is that 3 blacks, not 20, were

assigned to jobs in the IAM unit in 1944. PX 2,

63, CX 5. Apparently, the Steelworkers relied

upon the company's brief in the Court below rather

than the record for these statistics. The company

admitted in the Court of Appeals that these

statistics were based on mere speculation: "The

inference might possibly be drawn that as many as

20 of the 100 lost were black . . . although there

is an element of conjecture in this ". Co. Brief

at 2 1 .

14/ During the occupational seniority system

TT947-54), the all-white Powerhouse jobs remained

in the racially mixed department. A new all-white

Powerhouse department was created within the USW

unit in 1954 upon the return to a departmental

system.

- 12 -

The imposition of occupational seniority (1947-54)

During this seven-year period, there was an

occupational seniority system in effect at Pull

man. Under the occupational seniority system an

employee could hold seniority in only one occupa

tion, except that at the discretion of management

an employee could be transferred and hold sen

io r ity in two occupations. PX 47, pp. 13-14

(1947 agreement). At this time, many of the one-

race departments and the sp linter departments

15/created at unionization were re-merged— into

the racially mixed departments, represented by the

USW, from which they had been separated at the

time of unionization. During this period there

was a decrease in the number of one-race depart

ments, an increase in the number of racially mixed

departments, and the configuration of the depart

ments was broadened. Two all-white departments

in the IAM and IBEW units, which were ceded to the

USW in 1944 and 1946, respective ly , were d is -

15/ /The all-White Powerhoue and Air Brake Pipe

departments were merged into ra c ia l ly mixed

departments during this time frame. PX 2-7.

13 -

banded; those jobs were then placed in the ra

cially mixed departments where they had been prior

to unionization. See, supra, p. 11, nn.12, 14.

The Return to departmental seniority and concom

itant changes in departmental structure (1954 to

t r ia l )

A company-wide agreement was negotiated with

the Steelworkers in August of 1954 which included

a ll Pullman-Standard plants, and in 1956 for the

f irs t time the seniority was used for promotional

purposes. A 131.— As a result of the 1954 nego

tiations, Bessemer returned to the departmental

17/

seniority system.---- However, the system was

not imposed upon the departmental configuration

16/ Previously, seniority, whether departmental

or occupational, was used only for purposes of

layoff and recall.

17/ Under the departmental system an employee

who transfers from one department to another

"shall relinquish seniority in the department from

which he is transferred and shall start as a new

employee in the department to which he is trans

fe rred .. . . " See e.g ., PX 35, p. 25 (1944

agreement) PX 34 (1954 agreement).

14 -

which obtained at the Bessemer plant during the

period of occupational seniority (1947-54).

Instead, when the departmental seniority

system returned to Pullman (1954-1972), again

the racial composition of the departments within

the USW unit was altered. More one race depart

ments were created, including some one-job depart

ments, were carved from racially mixed depart

ments, In June 1954, two months prior to the

negotiation of, and return to, the departmental

system at Bessemer, five brand new, one-race

18/departments were created within the USW unit.—

Compare PX 8 with PX 9.

18 / The Steelworkers misstate the facts regard

inĝ the establishment of these one-race depart

ments. The Steelworkers assert that the depart

ments were created during the period when occupa

tional seniority was in effect and thus conclude

that the creation of the departments did not harm

the employment opportunities of the black workers.

USW Pet. 8-10, 17 n.9. In fact, these departments

were created just prior to the shift to departmen

tal seniority. PX 8 , 9.

15

The increase in one-race departments

19/ .The five one-race departments---- included

the establishment of one all-black department,

Janitors, and four a l l white departments: Plant

Protection, (see Brief, n.21), Boiler House, Power

House, and the Air Brake Department. See nn.12,

14,supra; PX 8, 9. The 1954 seniority system at

the Bessemer plant remained "virtually unchanged

throughout the next eighteen years of collective

bargaining." A 131, 158.-^^

19/ In 1954 another department, Railroad, was

created which, except for the highest paying job,

was all-black, PX 8, 9.

20/ In 1972 under the direction of the Labor

Department an alteration in the system was made

to-allow a limited opportunity for some of the

black employees to promote to formerly white-only

jobs without forfeiting their seniority. See A

131-32, 159.

ME11EN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. *»’