Muntaqim v. Coombe Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

March 30, 2005

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Muntaqim v. Coombe Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 2005. 4c1356f1-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0cc5d4b1-618e-4a3c-942e-9774bb20a106/muntaqim-v-coombe-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

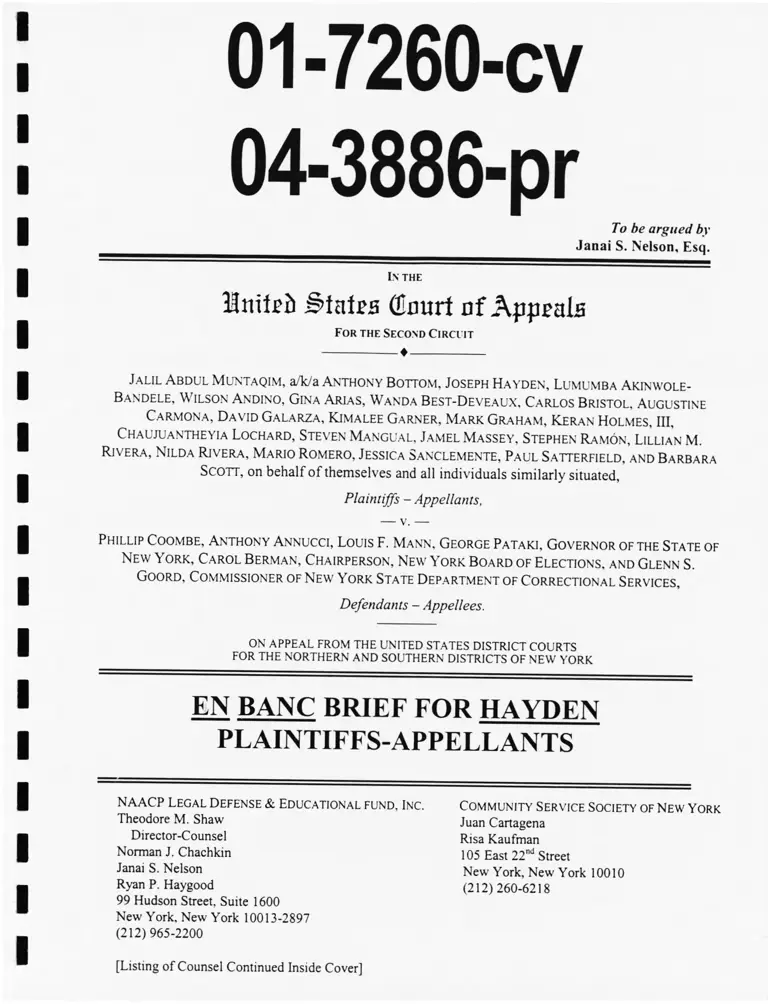

01 -7260-cv

04-3886-pr

To be argued by

_______________________ Janai S. Nelson, Esq.

In the

IniieZ) Bialw (fnurt nf Appealfi

For the Second Circuit

Jalil A bdul Muntaqim, a/k/a Anthony Bottom, Joseph Hayden, Lumumba A kinwole-

Bandele, W ilson A ndino, Gina Arias, Wanda Best-D eveaux, Carlos B ristol, Augustine

Carmona, David Galarza, Kimalee Garner, Mark Graham, Keran Holmes, III,

Chaujuantheyia Lochard, Steven Mangual, Jamel Massey, Stephen Ramon, Lillian M.

Rivera, N ilda Rivera, Mario Romero, Jessica Sanclemente, Paul Satterfield, and Barbara

Scott, on behalf o f themselves and all individuals similarly situated,

Plaintiffs - Appellants,

Phillip Coombe, Anthony Annucci, Louis F. Mann, George Pataki, Governor of the State of

N ew York, Carol Berman, Chairperson, N ew York Board of Elections, and Glenn S.

Goord, Commissioner of N ew York State Department of Correctional Services,

Defendants - Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURTS

FOR THE NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN DISTRICTS OF NEW YORK

EN BANC BRIEF FOR HAYDEN

PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

NAACP Legal Defense & Educational fund, Inc.

Theodore M. Shaw

Director-Counsel

Norman J. Chachkin

Janai S. Nelson

Ryan P. Haygood

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013-2897

(212) 965-2200

Community Service Society of New York

Juan Cartagena

Risa Kaufman

105 East 22nd Street

New York, New York 10010

(212) 260-6218

[Listing of Counsel Continued Inside Cover]

Center for Law and Social Justice

at Medgar Evers College

Joan P. Gibbs

Esmeralda Simmons

1150 Carroll Street

Brooklyn, New York 11225

(718)270-6296

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Pursuant to Rule 26.1 of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, the NAACP

Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc., Community Service Society of New York,

and the Center for Law and Social Justice at Medgar Evers College, by and through

the undersigned counsel, make the following disclosures:

Counsel for Plaintiffs-Appellants, all not-for-profit corporations of the State

of New \ ork, are neither subsidiaries nor affiliates of a publicly owned corporation.

— -

Janai S. Nelson, Esq.

Director of Political Participation

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New' York, NY 10013

(212) 965-2237

jnelson@naacpldf.org

mailto:jnelson@naacpldf.org

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT............................................................

TABLE OF CONTENTS................................................................................................j,

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES........................................................................................ jv

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT.....................................................................................1

STATEMENT OF SUBJECT MATTER AND APPELLATE JURISDICTION.... 1

STATEMENT OF QUESTION PRESENTED............................................................ 2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE...................................................................................... 3

STATEMENT OF RELEVANT FACTS......................................................................8

STANDARD OF REVIEW.......................................................................................... 14

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT....................................................................................14

ARGUMENT................................................................................................................ j 7

I. Congress Has the Authority to Enforce the Reconstruction Amendments by

Applying Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act to New York’s Felon

Disfranchisement Scheme, Which Disqualifies Certain People with Felony

Convictions from Voting on the Basis of Race (En Banc Question No. 1)

................................................................................................................................17

II. The “Plain Meaning Rule” of Statutory Interpretation Establishes that

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act is Applicable to New York’s Felon

Disfranchisement Regime, and the “Clear Statement Rule” Has No

Application to this Case (En Banc Question No. 2 )........................................24

n

III. Proof Required to Establish a Challenge to §5-106(2) Pursuant to a Vote

Dilution Theory under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (En Banc

Question No. 3).............................................................................................. 29

A. Disparate Impact of New York Election Law §5-106...........................30

B. Totality' of the Circumstances Test..........................................................3 1

Evidence of Discrimination in the Criminal Justice System.... 33

a. Type of Evidence (Court's En Banc Question No. 3(a))

.............................................................................................33

b. Quantum of Proof (Court’s En Banc Question No. 3(b))

.............................................................................................36

c. Relevance of Evidence of Discrimination in Federal and

State Criminal Justice System (Court’s En Banc Question

No- 3 (c))............................................................................ 36

ii. Other Senate Factors.................................................................... 36

IV. Hayden Appellants are Proper Representatives of Their Respective Proposed

Subclasses and Satisfy all Requirements for Bringing Claims on Their Own

Behalf as Well as on Behalf of the Proposed Subclasses They Represent... 39

A. Hayden Community-Member Appellants are Appropriate

Representatives of Their Respective Proposed Subclasses and Satisfy

All Requirements of Fed. R. Civ. P. Rule 23...................................... 40

B. Hayden Prisoner-and Parolee- Subclass Representatives Are Not

Required to Demonstrate Individualized Discrimination that Resulted

in Their Incarceration or That a Similarly Situated White Person

Necessarily Would Have Been Treated Differently............................44

iii

CONCLUSION 46

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

FEDERAL CASES

Allen v. Ellisor.

664 F.2d 391 (4th Cir. 1981), vacated as moot 454 U S 807 (1981) ...................... 25

Amchem Products Inc., v. Windsor.

521 U.S. 591 (1997)................................................................................................ 43

Aslandis v. United States Lines. Inc..

7 F.3d 1067 (2d Cir. 1993)...................................................................................... ]4

Baffa v. Donaldson. Lufkin. Jenrette Sec. Cnrp..

222 F.3d 52 (2d Cir. 2000)...................................................................................... 43

Bd. of Trustees v. Garrett.

531 U.S. 356 (2001)............................................................................................... 19

Caridad v. Metropolitan-North Commuter R.R..

191 F.3d 283 (2d Cir. 1999).................................................................................... 40

Chisom v. Roemer.

501 U.S. 380 (1991)..........................................................................................passim

City of Boeme v, Flores.

521 U.S. 507 (1997).......................................................................................... 19.20

DeMuria v. Hawkes.

328 F.3d 704 (2d Cir. 2003).................................................................................... 14

In re Drexel Burnham Lambert Group. Inc..

960 F.2d 285 (2d Cir. 1992).................................................................................... 42

East Texas Motor Freight Svs.. Inc, v. Rodriguez.

431 U.S. 395 (1977).......................................................................................... 4 j 43

Farrakhan v. Locke.

987 F. Supp. 1304 (E.D. Wash. 1997), affd. Farrakhan v. Washington

338 F.3d 1009 (9th Cir. 2003) ................................................................................ 21

Fla. Prepaid v. College Sav. Bank.

527 U.S. 627(1999)................................................................................................ 19

Goosbv v. Town of Hempstead.

180 F.3d 476 (2d Cir. 1999), cert, denied. 528 U.S. 1138 (2000) ........................... 37

Green v. Bd. of Elections.

380 F.2d 445 (2d Cir. 1967).................................................................................... 22

IV

Gregor\' v. Ashcroft.

501 U.S. 452 (1991)........................................................................................ 2. 26-27

Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections.

383 U.S. 663 (1966)................................................................................................ 22

Herron v, Koch.

523 F. Supp. 167 (S.D.N.Y. 1981)........................................................................... 37

Houston Lawyers’ Ass’n v. Attorney General.

501 U.S. 419(1991)................................................................................................ 27

Hunter v. Underwood.

471 U.S. 222 (1985)............................................................................................ 20-21

Johnson v. Gov, of Fla..

353 F.3d 1287 (11th Cir. 2003) .............................................................................. 28

Katzenbach v. Morgan.

384 U.S. 641 (1966)................................................................................................ 19

Marisol A. v. Guiliani.

126 F.3d 373 (2d. Cir. 1997)................................................................................... 40

Mitchum v, Foster.

407 U.S. 225 (1972)................................................................................................ 27

Muntaqim v. Coombe.

366 F.3d 102 (2d Cir. 2004)..............................................................................passim

Nevada Dep’t of Human Res, v. Hibbs.

538 U.S. 721 (2003)................................................................................................ 19

New Rochelle Voter Def. Fund v. City of New Rochelle

308 F. Supp. 2d 152 (S.D.N.Y. 2003)...................................................................... 37

Pa. Dep’t of Corr. v. Yeskev.

524 U.S. 206(1998)................................................................................................ 26

Rossini v. Qgilvv & Mather. Inc..

798 F.2d 590 (2d Cir. 1986).................................................................................... 42

Salinas v. United States.

522 U.S. 52 (1997).................................................................................................. 26

Schick v. Schmutz (In re Venture Mortgage Fundi.

282 F.3d 185 (2d Cir. 2002).................................................................................... 24

Schlesinger v. Reservists Comm, to Stop the War.

418 U.S. 208 (1974)................................................................................................ 43

v

South Carolina v. Katzenbach.

383 U.S. 301 (1966)........ 19

Tennessee v. Lane.

541 U.S. 509, 124 S. Ct. 1978 (2004)

Thornburg v. Gingles.

478 U.S. 30(1986)...........................

Trop v. Dulles.

356 U.S. 86 (1958)............................

United States v, Morrison.

529 U.S. 598 (2000)..........................

Vargas v. Citv of New York.

377 F.3d 200 (2d Cir. 2004)..............

DOCKETED CASES

Havden v, Pataki.

No. 00 Civ. 8586, 2004 WU 1335921 (S.D.N.Y. June 14, 2004)............................

Havden v. Pataki.

No. 04-3886-pr (2d Cir. Feb. 24, 2005)(order consolidating Havden v, Pataki with

Muntaqim v. Coombe. No. 01-7260-cv)(“En Banc Consolidation Order”) ........ 1,

FEDERAL STATUTES

42U.S.C. §1973 ............................................................................................................ 44

42 U.S.C. § 1973(a) .............................................................................. 15,24,25,30,44

42 U.S.C.§ 1973(b) ....................................................................................................... 44

42 U.S.C. §§ 1973(f)..................................................................................... j

28 U.S.C. §§ 1331 and 1343 .............................................................. ]

Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(c) ............................................................................................. ]4

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23 .................................................................................................... ]6,40

S. Rep. No. 97-417 (1982), reprinted in 1992 U.S.C.A.A.N. 177, 179 ................... 32, 45

vi

STATE STATUTES

N.Y. Const, art. II, § 2 (amended 1894)

N.Y. Const, art. II, § 3 .........................

N.Y. Election Law § 5-106...................

.. 12-1

......... 8

passim

MISCELLANEOUS

Anthony Thompson, Stopping the Usual Suspects. 74 N.Y.U L Rev 956

(1999) .................................................................

Becky Pettit & Bruce Western, Mass Imprisonment and the Life Course:

Race and Class Inequality in U.S. Incarceration. 69 American Sociological Review

151 (2004) .......................................................................................... .. 35

Brief for the Association of the Bar of the City of New York as Amicus Curiae in

Support of Appellant (“City Bar Amicus Br.”) ...................................... 21, 22, 24, 27

Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae Supporting Appellee in Part

and Urging Affirmance...................................................................................... 27 28

Brief of the United States as Amicus Curiae in Support of Defendants-Appellees

at 25-33, Muntaqim (Nos. 01-7260-cv, 04-3886-pr)(“Brief of United States”).....27

Compl., U.S. v. Brown, et ah. (S.D. Miss. 2005)(No. 4:05- cv-33 TSL-AGN) ............ 28

Cong. Globe, 40th Cong., 3d Sess. 1012-13 (1869)......................................................... 23

Dorothy E. Roberts, The Social and Moral Cost of Mass Incarceration in

African American Communities.

56 Stan. L. Rev. 1271 (2004) ............................................................................. 32 35

En Banc Brief in Support of Plaintiff-Appellant Jalil-Abdul Muntaqim, a/k/a Anthony

Bottom, and in Support of Reversal, on Behalf of Amici Curiae NAACP Legal

Defense & Educational Fund, Inc., Community Service Society of New York, and

Center for Law and Social Justice at Medgar Evers College (“Hayden Counsel

Amicus Brief T................................................................................................ 21 45

En Banc Brief of Amici Curiae the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law,

People for the American Way Foundation, National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People, and National Black Law Students Association Northeast Region

in Support of Appellant and in Support of Reversal (“Lawyers’ Committee Amicus

Br ”) ................................................................................................................... 26-27

En Banc Brief of the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law

and the University of North Carolina School of Law Center for Civil Rights as Amici

Curiae Supporting Plaintiff- Appellant Jalil Abdul Muntaqim and In Support of

Reversal (“Brennan Amicus Brief”) .................................................... ->7

Invisible Punishment: Collateral Consequences of Mass Imprisonment (Marc Mauer and

Meda Chesney-Lind eds. 2002)........................................................................... 33

James P. Lynch & William Sabol, Effects of Incarceration on Social Control

in Communities, in The Impact of Incarceration on Families and

Communities........................................................................................................... 35

Jeff Fagan, et ah, Reciprocal Effects of Crime and Incarceration in New

York Citv Neighborhoods. 30 Fordham Urb. L.J. 1551 (2003) .............................. 34

Jeff Fagan & Garth Davies, The Effects of Drug Enforcement on the Rise

and Fall of Homicides in New York City. 1985-95. Final Report, Grant

No. 031675, Substance Abuse Policy Research Program, Robert Wood

Johnson Foundation (2002)................................................................................. 33-34

Jeff Fagan & Tom R. Tyler, Legal Socialization of Children and Adolescents. Social

Justice Research (forthcoming 2005) ................................................................... 34

Joan Moore, Bearing the Burden: How Incarceration Policies Weaken

Inner-Citv Communities, in The Unintended Consequences of

Incarceration ....................................................................................................... 35

John Hagan & Ronit Dinovitzer, Collateral Consequences of Imprisonment

for Children, Communities, and Prisoners, in 26 Crime and Justice A

Review of Research: Prisons ................................................................................... 35

Office of the Attorney General of the State of New York, Civil Rights Bureau, The New

York Citv Police Department’s “Stop & Frisk” Practices (19991 ...................... 33-34

Reply Brief for the United States .................................................................................. 28

Todd R. Clear, et ah, Coercive Mobility and Crime: A Preliminary Examination

of Concentrated Incarceration and Social Disorganization. 20 Justice

Quarterly 33 (2003).................................................................................................. 35

viii

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

This appeal is from an unreported decision and judgment of the United States

District Court for the Southern District of New York (McKenna, J.), granting

Defendants’ Motion for Judgment on the Pleadings and dismissing Plaintiffs-

Appellants’ (“Hayden Appellants” or “Appellants”) action in its entirety. The

decision is set forth in the Hayden Appellants’ Supplemental Appendix (“ASA”) at

00001 - 00179. On July 13, 2004, Hayden Appellants filed their notice of appeal to

this Court. By order dated February 24, 2005, this Court consolidated this case with

Muntaqim v, Coombe. which was already designated to be heard en banc, on the

common question of law as set forth in the Statement of Question Presented, infra.1

STATEMENT OF SUBJECT MATTER

AND APPELLATE JURISDICTION

Hayden Appellants’ claims for declaratory and injunctive relief arise under the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution and under

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. Thus, the district court had subject matter

jurisdiction over those claims pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331 and 1343, and 42 U.S.C.

§§ 1973(f) and §1983. The final judgment and order dismissing the claims was

entered on June 14, 2004, and on July 13, 2004, Havden Appellants filed their notice

of appeal to this Court. 1

1 Hayden v. Pataki, No. 04-3886-pr (2d Cir. Feb. 24 ,2005)(order consolidating

Havden v. Pataki with Muntaqim v, Coombe. No. 01-7260-cv)(“En Banc

Consolidation Order”).

1

STATEMENT OF QUESTION PRESENTED

The Court’s En Banc Consolidation Order expressly states that the question

presented in this consolidated appeal is whether, on the pleadings, a claim that New

York Election Law §5-106, which disfranchises persons currently incarcerated or on

parole for a felony conviction, results in unlawful vote denial and/or vote dilution can

be brought under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, as amended. Havden Appellants

respectfully submit that this threshold question is the only issue before the Court at

this time.2 * 1

The Court’s En Banc Consolidation Order also sets forth the following

questions for the parties to address in their briefs:

(1) Whether Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act can constitutionally be

applied to New York Election Law §5-106 in light of the Supreme Court’s recent

jurisprudence regarding Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment;

(2) Whether the Supreme Court’s “clear statement rule,” articulated in

Gregory v. Ashcroft, 501 U.S. 452, 460-61 (1991), requires Congress to have clearly

stated that the Voting Rights Act was intended to infringe upon the states’ discretion

to deprive persons currently incarcerated as felons and parolees of the right to vote

and, if so, whether Congress had made that intent clear;

(3) What proof of racial bias in the criminal process is relevant to

assessing a Section 2 vote dilution claim, including the type and quantum of statistical

proof and the data and variables of such statistical proof, whether there are relevant

distinctions in the federal and state criminal justice systems and whether a finding of

discrimination in one and not the other affects the determination of the vote dilution

claim, and how evidence of racial disparity in the criminal process factors into the

Voting Rights Act’s “totality of the circumstances” test;

(4) Whether certain Hayden Appellants are proper class representatives

for the proposed subclass they seek to represent and whether those appellants alleging

vote denial must prove that his or her particular incarceration was the result of

discrimination and that a similarly situated white person would have been treated

differently.

2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The instant appeal is the consolidation of two voting rights cases, Muntaqim

vJToombe and Hayden v. Pataki, that challenge New York’s felon disfranchisement

scheme on the ground that New York Election Law §5-106 (“New York’s felon

disfranchisement statute or §5-106 ) unlawfully denies Blacks and Latinos in prison

or on parole for a felony conviction the right to vote on account of their race under

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, as amended (“Voting Rights Act,” “VRA” or

“Act”). Hayden Appellants also challenge §5-106 on the ground that it has a

disparate impact on and dilutes the voting strength of New York State’s Black and

Latino communities in violation of Section 2 of the VRA. In both cases, Appellants

rely on the broad scope of the VRA to provide a remedy for the palpable effects of a

punitive voting qualification that is rooted in racial discrimination and yields

discriminatory results today.

Muntaqim v. Coomhe

On September 26, 1994, pro se inmate Jalil Abdul Muntaqim filed Muntaqim.

challenging New York Election Law §5-106 under the Voting Rights Act, on the

ground that it prohibits him from voting on account of his race. No significant

discovery had taken place when appellees in Muntaqim3 moved for summary

See En Banc Consolidation Order, at 2-3.

Muntaqim filed this action against Philip Coombe, Commissioner, New York

State Department of Correctional Services, Anthony Annucci, Deputy Commissioner

New York State Department of Correctional Services, and Louis Mann’

Superintendent of the Shawangunk Correctional Facility (“Muntaqim Appellees”)’

3

judgment, and on January 24, 2001, the district court granted their motion in its

entirety, holding that New York State’s felon disfranchisement scheme is immune

from challenge under the Voting Rights Act. Judgment was entered against Muntaqim

on January 25, 2001. A panel of this Court affirmed the district court’s decision on

April 23, 2004. Muntaqim filed a petition for a writ of certiorari to the United States

Supreme Court on July 21, 2004. On October 1, 2004, this Court issued an order

indicating that a sua sponte poll as to whether to rehear the case en banc had failed.

The Supreme Court denied Muntaqim’s petition for a writ of certiorari on November

8, 2004. Muntaqim then moved for rehearing en banc, and, by order dated December

23, 2004, this Court agreed to rehear his appeal en banc. On December 29, 2004, the

Court issued an amended scheduling order in the Muntaqim appeal, requesting that

the parties address four specific issues in their briefs. The order set forth a briefing

schedule and an April 7, 2005 oral argument.4

Hayden v. Pataki

Hayden v. Pataki was originally filed pro se by Plaintiff-Appellant Joseph

Hayden on September 13, 2000, in the Southern District of New York, alleging that

§5-106, which prohibited him from voting in New York State solely because of his

felony conviction and incarceration, violated his rights under the Voting Rights Act

and the U.S. Constitution. Hayden’s pro se complaint was docketed on November 9,

Per this Court’s Second Amended Scheduling order, on January 28 2005

Muntaqim filed a brief responding to this Court’s order to address the four specific

issues that are nearly identical to those set forth in the En Banc Consolidation Order.

Alter these cases were consolidated, oral argument was rescheduled for June 22,2005.

4

2000. Defendant Carol Berman, Chairperson of the New York State Board of

Elections (“Berman”), and Defendants George Pataki (“Pataki”), Governor of the

State of New York, and Glenn Goord, Commissioner of the New' York State

Department of Correctional Services (“Goord”), filed answers on January 5,2001, and

on February 28, 2001, respectively.

On January 15, 2003, Joseph Hayden, on parole but nonetheless disfranchised

by operation of New York’s felon disfranchisement laws, moved (by and through

undersigned attorneys), for leave to file an amended complaint for declaratory and

injunctive relief (“First Amended Complaint” or “FAC”). District Court Judge

McKenna granted this motion on February 21, 2003. The First Amended Complaint

added new appellants, including representatives for three plaintiff subclasses,5 and

expanded the claims in this action against Defendants Pataki and Berman in their

official capacities (“Hayden Appellees” or “Defendants”).6 The First Amended

Complaint includes detailed allegations in support of the constitutional and Voting

Rights Act claims of intentional discrimination in the original enactment of New

D. additional plaintiffs may be grouped within three separate subclasses: 1)

Blacks and Latinos eligible to vote but for their incarceration for a felony conviction-

2) B acks and Latinos eligible to vote but for their parole for a felony conviction; 3)

Black and Latino voters who reside in specific communities in New York City whose

collective voting strength is unlawfully diluted because of New York’s

disfranchisement laws. Appellants filed a motion to certify these subclasses on

November 3, 2004, which the district court denied as moot in its June 14 2004

judgment and order granting Defendants’ motion for judgment on the pleadings

Hayden v. Pataki, No. 00 Civ. 8586, 2004 WL 1335921 (S.D.N.Y. June 14, 2004).

6 Goord was not named as a defendant in the First Amended Complaint and is

no longer a party to this action.

5

York’s felon disfranchisement laws,7 and of the Voting Rights Act claim arising out

of the disparate impact of §5-106, as well as claims under the First Amendment, the

Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and

1960, and customary international law. Defendants Berman and Pataki answered this

amended pleading on April 8, 2003, and April 14, 2003, respectively.

On April 10, 2003, Judge McKenna denied Havden Appellees’ motion to stay

discovery until this Court adjudicated Muntaqim v. Coomhe. 366 F.3d 102 (2d Cir.

2004). Discovery by all parties commenced pursuant to a scheduling order issued by

Magistrate Judge Henry Pitman on May 19, 2003. While the Muntaqim appeal was

pending before a panel of this Court, Hayden Appellees filed a motion for judgment

on the pleadings on July 10, 2003. Appellants filed a brief in opposition on

September 9, 2003. All parties actively engaged in discovery through June 14, 2004,

at which time District Court Judge McKenna issued a final Memorandum and Order

granting Defendants’ Motion for Judgment on the Pleadings in its entirety. The

district court held that Appellants’ VRA claims must be dismissed in light of the

ruling by a panel of this Court in Muntaqim. holding that the Voting Rights Act does

not apply to felon disfranchisement laws. The court below further held as a matter of

law that Appellants had not alleged facts sufficient to state claims against Appellees

under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.

In the First Amended Complaint, Havden Appellants outline over one

hundred years of constitutional history in New York and include allegations of

specific acts of intentional discrimination denying the franchise to Blacks (ASA

00045-49 [FAC 39-57]).

6

On July 13, 2004, Hayden Appellants filed a notice of appeal to this Court.

They subsequently filed their brief in support of appeal on September 27, 2004.

Appellees filed an opposition brief on November 24, 2004, and Havden Appellants

filed a reply brief on December 8, 2004. In their briefs, Havden Appellants argued

that the district court applied the incorrect standard in dismissing their claims under

the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, and that they had, in fact, pled sufficient

facts to withstand a motion for judgment on the pleadings. Havden Appellants also

sought to preserve their Voting Rights Act claims pending final resolution in

Muntaqim.

Consolidation of Muntaqim and Havden

On February 24, 2005, this Court ordered that Havden be consolidated with

Muntaqim and adjourned the previously scheduled April 7, 2005 argument date in

^ ta(lim' In a separate order of the same date, the Court ordered that the Voting

Rights Act claims in Hayden be heard en banc and consolidated with Muntaqim and

requested that Appellants address a series of questions identified by the Court. The

order set a March 23, 2005 deadline for Havden Appellants’ brief.

On March 1, 2005, Appellees filed a motion for consolidated briefing in

Muntaqim and Hayden, which Muntaqim opposed on March 9, 2005, and which

Hayden Appellants opposed on March 10,2005. Along with their opposition, Havden

Appellants filed a motion for a one-week extension of time in which to file their brief.

On March 11, 2005, this Court issued an order granting Appellees’ motion to

consolidate briefing, and granting Havden Appellants’ motion for a one-week

7

extension of time. The March 11, 2005 order sets forth March 30, 2005, as the date

by which briefs of appellants and amici in support of appellants in both Muntaqim and

Hayden are due,8 with a consolidated appellees’ brief for both appeals due on April

27, 2003. Reply briefs for appellants are due on May 13, 2005, and oral argument is

scheduled for June 22, 2005.

STATEMENT OF RELEVANT FACTS

New York’s Felon Disfranchisement Laws

N.Y. Const, art. II, § 3 provides that “[t]he Legislature shall enact laws

excluding from the right of suffrage all persons convicted of bribery or any infamous

crime. 9 Icf New York Election Law §5-106 provides:

No person who has been convicted of a felony pursuant to the laws of the state,

shall have the right to register for or vote at any election unless he shall have

been pardoned or restored to the rights of citizenship by the governor, or his

maximum sentence of imprisonment has expired, or he has been discharged

from parole. The governor, however, may attach as a condition to any such

pardon a provision that any such person shall not have the right of suffrage

until it shall have been separately restored to him.

The First Amended Complaint

While Hayden Appellants have not yet had the benefit of full discovery, their

First Amended Complaint sets forth numerous allegations in support of their claims

for vote denial and vote dilution actionable under the Voting Rights Act.

Per this Court s order, dated March 14, 2005, Appellant Muntaqim has the

option of filing a new brief, or, in the alternative, may rely upon his brief filed

February 1, 2005.

9 The term “infamous crime” has come to mean felony under New York State

law. (ASA 00047 [FAC f 49]).

8

A. Racial Disparities

In their First Amended Complaint, Hayden Appellants included numerous

allegations regarding the racial disparities that result from the operation of §5-106.

Specifically, in New York State, Blacks and Latinos are prosecuted, convicted, and

sentenced to incarceration at rates substantially disproportionate to Whites. Although

Blacks make up approximately 15.9% of New York’s overall population (as reported

in the 2000 U.S. Census), they make up 54.3% of the current prison population and

50% of the current parolee population in New York State. (ASA 00049 [FAC ^ 62]).

Although Latinos make up approximately 15.1% of New York State’s overall

population (as reported in the 2000 U.S. Census), they make up 26.7% of the current

prison population and 32% of the current parolee population in New York State.

(ASA 00050 [FAC If 63]).

Collectively, Blacks and Latinos make up 86% of the total current prison

population and 82% of the total current parolee population in New York State, while

they approximate only 31% of New York State’s overall population. (ASA 00050

[FAC Tf 64]). By contrast, Whites make up approximately 62% of New York States’

overall population (as reported in the 2000 Census) and only 16% of New York

State’s current prisoners and parolees, respectively. (ASA 00050 [FAC If 65]).

Blacks and Latinos are sentenced to incarceration at substantially higher rates

than Whites, and Whites are sentenced to probation at substantially higher rates than

Blacks and Latinos. For example, in 2001, Whites made up approximately 32% of

felony convictions, yet comprised 44% of those who received probation and only

9

21.4% of those incarcerated for felony convictions. (ASA 00050 [FAC ̂66]). By

contrast, Blacks made up 44% of those convicted of a felony, but only approximately

of those sentenced to probation and 51% of those sentenced to incarceration.

(ASA 00050 [FAC 66]). Latinos comprised 23% of those convicted of a felony, yet

only 19% of those sentenced to probation and 26.5% of those sentenced to

incarceration. (ASA 00050 [FAC ^ 66]).

In addition, Blacks make up 30% and Latinos make up 14% of the total current

population of persons sentenced to probation in New York State, while Whites make

up 51% of such persons. (ASA 00050 [FAC U 67]). Nearly 52% of those currently

denied the right to vote pursuant to §5-106, are Black and nearly 35% are Latino.

Thus, collectively, Blacks and Latinos comprise nearly 87% of those currently denied

the right to vote pursuant to §5-106. (ASA 00050 [FAC ̂68]).

B. Vote Dilution

Hayden Appellants First Amended Complaint also contains allegations of

minority vote dilution resulting from operation of §5-106, including the specific claim

that the disproportionate rates of prosecution, conviction, and incarceration of Blacks

and Latinos (and the resulting disproportionate rates of disfranchisement among these

groups) has a disparate impact on the ability of Blacks and Latinos in New York State

to participate in the political process on an equal basis as Whites. (ASA 00051 [FAC

U 69]). A majority of New York State’s prison population consists of Blacks and

Latinos from New York City communities in the following areas: Harlem,

Washington Heights, the Lower East Side, the South and East Bronx, Central and East

10

Brooklyn, and Southeast Queens. (ASA 00051 [FAC | 70]). As a result of the

disproportionate disfranchisement of Blacks and Latinos, the voting strength of Blacks

and Latinos, as separate groups and collectively, is diluted in violation of Section 2

of the Voting Rights Act. (ASA 00051 [FAC f 71]).

C. Intentional Discrimination

In eighteen separate allegations in their First Amended Complaint (ASA 00045

[FA.(2 H 39 — 57]), Hayden Appellants outlined over one hundred years of

constitutional history in New York and made allegations of specific acts of intentional

discrimination to deny the franchise to Blacks.10

The allegations of the First Amended Complaint detail how the framers of the

New York State Constitution in 1777 intentionally excluded Blacks from the polls by

limiting suffrage to property holders and free men, (ASA 00046 [FAC ^ 43]),

requirements that disproportionately disfranchised Blacks. Id Further, when in 1801

the legislature removed all property restrictions from the suffrage requirements for the

election of delegates to New York’s first Constitutional Convention, at the same time

it expressly excluded Blacks from participating in this election. (ASA 00046 [FAC

145]).

New York’s felon disfranchisement provisions originated in this historical

period, specifically at the Constitutional Convention of 1821 — a convention

10 In addition to being the crux of Hayden Appellants’ constitutional intentional

discrimination claim currently pending before a panel of this Court without argument,

evidence that §5-106 was specifically enacted with the intent to discriminate against

Blacks should be considered in the “totality of the circumstances” analysis under

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act by the district court on remand. See, infra, note

11

dominated by an express, racist purpose to deprive the vote from “men of color.”

(ASA 00047 [FAC 1148]). Delegates expressed their conviction that Black New

Yorkers were unequipped and unfit to be part of the democratic process, (ASA 00046-

47 [FAC til 46-47]), and crafted new voting requirements that were aimed at stripping

Blacks of their previously held, albeit severely restricted, right to vote. Id. Race-

based suffrage requirements, such as heightened property requirements applicable

only to Blacks, were written into Article II of the New York State Constitution. (ASA

00047 [FAC H 48]). The discriminatory effect of these measures was evident; only

298 out of 29,701 Blacks, or less than 1% of the Black population of New York State,

met these new requirements. Id. New citizenship requirements were also devised and

applied in a racially discriminatory manner. Ich

The delegates to the 1821 Constitutional Convention also adopted a provision

that permitted the legislature to exclude from the franchise those “who have been, or

may be, convicted of infamous crimes.” (ASA 00047 [FAC 1f 49, quoting N.Y.

Const. (1821), art. II, § 2]). In 1826 the New York State Constitution was amended

to expand White male suffrage without any alteration of either the onerous property

requirements for Black males, or the felon disfranchisement provision. (ASA 00047

[FAC If 50]).

Delegates to New York’s 1846 Constitutional Convention made explicit

references to their belief that Blacks were unfit to vote. (ASA 00047 [FAC If 51]).

They adopted a new Constitutional provision expanding the Legislature’s

authorization to deny the franchise to “all persons who have been or may be convicted

12

of bribery, of larceny, or of any infamous crime.” (ASA 00047 [FAC ^ 52, quoting

N.Y. Const, art. II, § 2 (amended 1894)]). As in 1821, the delegates to the 1846

Constitutional Convention acted with knowledge that felon disfranchisement would

disproportionately reduce the numbers of Black voters, (ASA 00048 [FAC t 53]).

One speaker, for example, noted that “the proportion of ‘infamous crime’ in the

minority population was more than thirteen times that in the white population.” (ASA

00047 [FAC Tf 51]). The delegates were, therefore, aware of the racially

discriminatory impact of the felon disfranchisement law. (ASA 00048 [FAC ̂53]).

In the aftermath of the Civil War and the advent of Reconstruction, another

Constitutional Convention was convened in New York from 1866-67. At this

Convention, again the issue of equal manhood suffrage for Blacks was considered but

rejected. (ASA 00048 [FAC 1 54]). And the felon disfranchisement provision was

not removed or altered. JcL

It took the power of the federal government finally to bring equal manhood

suffrage to New York with the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870.

(ASA 00048 [FAC 1 55]). But two years after the passage of the Fifteenth

Amendment, an unprecedented committee convened to amend the New York State

Constitution s disfranchisement provision to require the State Legislature, at its

following session, to enact laws excluding persons convicted of infamous crimes from

the franchise. (ASA 00048 [FAC U 56], see N.Y. Const, art. II, § 2 (amended 1894)).

Until that point, enactment of such laws had been permissive. (ASA 00048 [FAC f

13

56]). This new mandate for felon disfranchisement was reaffirmed at a Constitutional

Convention in 1894, (ASA 00048 [FAC f 57]), and persists today.

STANDARD OF REVIEW

The standard of review by an appellate court in these consolidated appeals is

similar. In the instant case an appellate court reviews the ruling on a Fed. R. Civ. P.

12(c) motion for judgment on the pleadings de novo, Vargas v. City of New York. 377

F.3d 200, 205 (2d Cir. 2004), and accepts as true all factual averments made by the

plaintiffs including any inferences to be drawn therefrom. DeMuria v. Hawkes 328

F.3d 704, 706 (2d Cir. 2003). Similarly, in Muntaqim. a de novo review on appeal of

the district court’s grant of summary judgment is warranted and the appellate court

must review the evidence in a light most favorable to the non-moving party and draw

all reasonable inference in his favor. Aslandis v. United States Lines. Inc.. 7 F.3d

1067, 1072 (2d Cir. 1993). Accordingly, the standard of review in this consolidated

appeal is de novo for the similar claims they each raise.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The Voting Rights Act s application to laws intended to discriminate or result

in discrimination on account of race is unequivocal. Accordingly, laws like New York

Election Law §5-106 that disproportionately deny voting rights to racial and ethnic

minorities on account of their race fit squarely within the VRA’s scope. Not only

does §5-106 disproportionately deny voting rights to African Americans and Latinos

more than any other racial or ethnic group, this law exacts a punitive toll on Black and

14

Latino communities within New York State which suffer most acutely from racial

disparities in the criminal justice system.

Congress’s authority to stamp out discriminatory voting practices is rooted

firmly in the Constitution via the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. Both

amendments provide separate and reinforcing bases for Congress’s power in this

regard. Moreover, this authority is fully consistent with recent Supreme Court

jurisprudence regarding Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment. Indeed, the VRA

is the legislative embodiment of Congress’s force in this area and any aversion to

expanding the franchise to citizens with felony convictions should not result in a

distortion of the text and spirit of this important law, especially where the disparate

racial impact of the challenged practice is incontrovertible.

In addition, because of Congress’s unmistakable authority to legislate against

racially discriminatory voting practices and the unambiguous text of Section 2 of the

VRA, the clear statement rule does not apply and has no place in the determination of

the VRA’s application to felon disfranchisement laws. The “plain meaning” of

Section 2 demonstrates that its scope reaches any “voting Qualification or prerequisite

to voting” that results in vote denial or vote dilution on account of race. See 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973(a). Moreover, assuming, for the sake of argument, that the clear statement rule

does apply, Congress’s intent that Section 2 reach felon disfranchisement laws is

established by, among other things, the Act’s broad and expansive construction.

To prove a vote dilution claim under Section 2, the proof of racial disparities

or bias in the criminal justice system is no different than that for a vote denial claim.

15

There are several relevant measures concerning the criminal process that can inform

an analysis of such disparities which are discussed below. Similarly, the structure and

parameters of the “totality of the circumstances” test is the same for both vote dilution

and vote denial claims. Vote dilution claims, however, require the court to consider

more closely factors that bear directly upon the ability of the minority groups at issues

to participate in the electoral process on an equal basis as Whites. Factors that can

provide this perspective are discussed in Section III.

Finally, the named Hayden Appellants, through the three proposed subclasses

they seek to represent, are each valid class representatives. In particular, the persons

representing the subclass of persons alleging vote dilution under Section 2 not only

have standing to bring claims on their own behalves, but meet the requirements of

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23, which provide their authority to serve a class representatives. The

named Hayden Appellants who represent the subclasses of persons with felony

convictions unlawfully denied voting rights on account of their race are also proper

class representatives and are not required to show that their individual convictions

were the result of discrimination and that a similarly situated white person necessarily

would have been treated differently to pursue a claim under Section 2.

For these reasons and those set forth below, this Court should reverse the ruling

of the panel in Muntaqim, reverse the district court in Havden to the extent that it

relies on Muntaqim for any part of its holding, and remand these cases to the district

court for further proceedings.

16

ARGUMENT

In the interest of not burdening the Court with repetitive argument, Havden

Appellants, in response to questions Nos. 1 and 2 in this Court's En Banc

Consolidation Order do not restate, but rather summarize, adopt and incorporate by

reference the analyses in the Brief for Plaintiff-Appellant In Banc (“Muntaqim

Opening Br. ) and certain briefs of amicus curiae filed in support of Muntaqim

pursuant to this Court's En Banc Order, dated December, 29, 2004. Similarly, in their

response to Question 3 of the En Banc Consolidation Order, Hayden Appellants rely

in large part on the En Banc Brief in Support of Plaintiff-Appellant Jalil-Abdul

Muntaqim, a/k/a Anthony Bottom, and in Support of Reversal, on Behalf of Amici

Curiae NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc., Community Service Society

of New York, and Center for Law and Social Justice at Medgar Evers College

(“Hayden Counsel Amicus Brief’) and supplement the arguments in that brief within

the context of the vote dilution claim raised in Havden. I.

I. CONGRESS HAS THE AUTHORITY TO ENFORCE THE

RECONSTRUCTION AMENDMENTS BY APPLYING SECTION

2 OF THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT TO NEW YORK’S FELON

DISFRANCHISEMENT SCHEME, WHICH DISQUALIFIES

CERTAIN PEOPLE WITH FELONY CONVICTIONS FROM

VOTING ON THE BASIS OF RACE (En B a n c Question No. 1)

Congress is clearly vested with authority to enforce the Reconstruction

Amendments by prohibiting New York State from disfranchising people with felony

convictions on the basis of race. Indeed, Congress acted at the height of its powers,

and in a manner that was consistent with the spirit and purpose of the Reconstruction

17

Amendments when it enacted Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act to remedy racial

discrimination in voting. As the Muntaqim panel recognized in its discussion of

Congress’s enforcement power under Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment,

Supreme Court precedent “stands broadly for the proposition that Congress may

enforce the substantive provisions of the Reconstruction Amendments by regulating

conduct [through the “results test” of Section 2 of the VRA] that does not directly

violate those provisions.” (ASA 00170 rMuntaqim. 366 F.3d at 119 (“Panel Op,.” at

119)]). In this case, there is no constitutional impediment to Appellants’ claims,

where, as members of protected racial minority classes, Appellants seek relief under

the Voting Rights Act to enjoin the operation of §5-106, which unlawfully prevents

them from exercising a fundamental right on the basis of race.

To foreclose Appellants’ claims, the panel placed New York’s felon

disfranchisement law out of Section 2’s reach on the ground that the established

Supreme Court precedent failed to “delineate the outer boundaries of Congress’s

authority. (ASA 00170 [Panel Op., at 119]). The panel instead relied upon a

misinterpretation of more recent Supreme Court jurisprudence to conclude that,

though Congress’s authority to enact Section 2 was not in question, (ASA 00171

[Panel Opu, at 121]), Section 2 could not be constitutionally applied to New York’s

felon disfranchisement statute. (ASA 00174 [Panel Ojx, at 124]). In reality, the

Supreme Court s recent Fourteenth Amendment jurisprudence, particularly the

“congruence and proportionality” test, reinforces the constitutionality of Section 2’s

application to New York’s felon disfranchisement statute. In nearly every one of

18

these recent cases, the Supreme Court has regarded the Voting Rights Act as an

exemplar of appropriate enforcement legislation, and the standard for measuring all

other statutes. Tennessee v. Lane. 541 U.S. 509, 124 S. Ct. 1978, 1985 n.4 (2004);

Nevada Dep’t of Human Res, v. Hibbs. 538 U.S. 721, 736 (2003); Bd. of Trs. v.

Garrett, 531 U.S. 356, 373-74 (2001); United States v. Morrison. 529 U.S. 598, 626

(200°); Ha. Prepaid v. Coll. Sav. Bank. 527 U.S. 627, 638 (1999); CitvofBoeme v

Flores, 521 U.S. 507, 518, 526 (1997). Though the panel recognized these cases, it

nevertheless was “doubtful that § 1973 [could] be constitutionally applied to §5-106,”

(ASA 00175 [Panel Op., at 125]), and proffered several bases for constitutional

concern. None of the panel’s concerns, however, survive scrutiny or represent a

constitutional impediment to Appellants’ claims, id at 122-23.

First, enjoining the operation of §5-106, which denies the vote to people with

felony convictions on account of their race and color, is clearly a “congruent and

proportional response to the enduring legacy and continuing persistence in the

modem day of racial discrimination in voting. See, e ^ , Tennessee. 541 U.S. at 1988-

1992. As the Supreme Court recognized one year after the passage of the VRA,

Congress is vested with the authority to “use any rational means to effectuate the

constitutional prohibition of racial discrimination in voting,” South Carolina v.

Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 324 (1966), and is entitled to enact aggressive legislation

to achieve those ends. Katzenbach v. Morgan. 384 U.S. 641, 651 (1966). Applying

Section 2 to New York s racially discriminatory felon disfranchisement regime is

19

entirely consistent with the purpose of the VRA, and does not exceed Congress’s

enforcement power.11

Second, the panel applied an unreasonably restrictive interpretation of the

Supreme Court’s recent Fourteenth Amendment cases, requiring Congress, in order

to prohibit felon disfranchisement laws that were not enacted with a discriminatory

purpose, to compile a record of intentional voting rights discrimination that could be

deterred or prevented by invalidating those laws.” (ASA 00175 [Panel Q&, at 125]).* 12

Congress, however, is required only to make findings on broad categories of unlawful

racial discrimination, not to develop a practice-specific record, as the panel mistakenly

believes, and the Supreme Court has not required such findings. See CitvofBoem e.

521 U.S. at 531 (Court focused on the lack of a “widespread pattern of religious

discrimination in this country, not on the allegedly discriminatory zoning practices

at issue). The Supreme Court has also recognized that Congressional enforcement

legislation can be supported by findings outside of the Congressional Record. See

Tennessee, 541 U.S. at 1988-90 (Court relied on numerous sources outside of the

For further elaboration on these points, Appellants adopt and incorporate by

reference the Muntaqim Opening Br„ at 30-39, and Brief for the Association of the

Am'0* 1B t>23^25 ̂ ^ A™CUS Curiae in SuPPort of Appellant (“City Bar

12 Ironically, in its discussion of Hunter v, Underwood 471 U.S. 222 (1985)

the panel minimized the significance of Hunter’s substantial findings of Alabama’s

practice-specific intentional racial discrimination as support for Congress’s authority

to reach felon disfranchisement law through Section 2 holding that though such

evidence rnight be sufficient to support the regulation of disenfranchisement laws

m Georgia [§ic] it would not support regulation of felon disfranchisement in all fifty

states. (ASA 00176 [Panel Op., at 126]). y

20

Congressional record to determine that the ADA’s Title II is congruent and

proportional legislation).

Notwithstanding that Appellants have alleged — with ample evidentiary

support that New York’s felon disfranchisement scheme was enacted with

discriminatory intent, the panel’s reading of the Supreme Court’s enforcement

authority precedent to require geographically-targeted evidence of discriminatory

felon disfranchisement is unreasonably narrow.13

Third, Congress s authority to prohibit New York from disfranchising people

with felony convictions from voting on the basis of race is not precluded by the “other

crime” provision in Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment. Indeed, because the

other crime provision did not foreclose the Equal Protection challenge to Alabama’s

felon disfranchisement law in Hunter v. Undemood. 471 U.S. 222 (1985), it cannot

now be used to bar Appellants from challenging §5-106 under Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act. See Farrakhan v. Locke. 987 F. Supp. 1304, 1310 (E.D. Wash. 1997)

(ruling that, after Hunter, it “necessarily follows, then, that Congress also has the

power to protect against discriminatory uses of felon disenfranchisement statutes

through the VRA”), affd , Farrakhan v. Washington 338 F.3d 1009 (9th Cir. 2003).

Fourth, the panel’s suggestion that penological justifications, (ASA 00172

[Panel Op,, at 122]), and “the longstanding practice in this country of disenfranchising

felons, (ASA 00173 [Panel Op,, at 123]), can exempt §5-106 from Section 2 review

13

r„ , F° r ["rther elaboration on this point, Appellants adopt and incorporate by

reference the Muntaq.rn Opening Br„ at 39-43, and City Bar Amicus Br„ at 25-27

and Hayden Counsel Amicus Brief, at 26-29.

21

is also misplaced. For one thing, with respect to an earlier version of §5-106, this

Court recognized in Green that New York’s felon disfranchisement law is a

“non-penal exercise of the power to regulate the franchise.” Green v. Rd. of Elections,

380 F.2d 445, 449 (2d Cir. 1967)(quoting Trop v. Dulles. 356 U.S. 86, 97 (1958)).

In addition, the mere fact alone that §5-106 is deeply rooted in tradition does not

protect it from Voting Rights Act scrutiny.14 It is worth noting that the enslavement

of Africans, poll taxes and literacy requirements, too, are rooted in this nation’s

tradition and yet have been found unconstitutional and antithetical to its current

values. See generally Harper v. Virginia State Bd. of Flections 383 U.S. 663, 669

(1966)(Courts are “not shackled to the political theory of a particular era[,]” and are

not confined to historic notions of equality” or “what was at a given time deemed to

be the limits of fundamental rights.”).15

Finally, the constitutionality of applying Section 2 of the VRA to §5-106 must

also be evaluated in light of Congress’s authority vested by the Fifteenth Amendment.

The panel s exclusive reliance on §2 of the Fourteenth Amendment to preclude

Section 2’s application to felon disfranchisement laws is insufficient because the

primary purpose of the VRA is to “enforce the fifteenth amendment to the

For further elaboration on these points, Appellants adopt and incorporate by

reference the Muntaqim Opening Br., at 43-50, and City Bar Amicus Br., at 26-31

filed in support of Muntaqim.

15 It is important to note here that Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act must be

interpreted in a way that is true to its purpose and spirit as envisioned by Congress,

and interpreted by the courts, and that the integrity of this interpretation cannot be

compromised by an actual or perceived reluctance to expand the franchise to citizens

with felony convictions.

22

Constitution of the United States.” Chisom v. Roemer 501 U.S. 380, 383 (1991)

Designed to provide greater protection than the Fourteenth Amendment by enacting

a broad prohibition on any disfranchisement on account of race, the Fifteenth

Amendment does not exempt felon disfranchisement. In fact, the legislative history

of its enactment reveals that Congress considered, but repeatedly rejected, proposed

versions of the Fifteenth Amendment that would have explicitly permitted states to

disfranchise persons convicted of felonies. Cong. Globe, 40th Cong., 3d Sess. 1012-

13, 1041 (1869)(rejecting by a wide margin two versions of Fifteenth Amendment

proposed by Representative Warner that sought to incorporate felon disfranchisement

language). The text of the Fifteenth Amendment that finally passed both Houses of

Congress made no reference to felon disfranchisement. With the Fifteenth

Amendment, Congress created a express ban on disfranchisement on account of race,

without importing expressly, or implicitly, the exemption of felon disfranchisement

contained in Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment. Accordingly, Congress’s power

to enforce the Fifteenth Amendment includes the ability to require New York to

discontinue enforcing §5-106, which discriminates against people with felony

convictions on the basis of race.16

For further elaboration on this point, Appellants adopt and incorporate by

reference the Muntaqim Opening Br., at 47-49, and En Banc Brief of the Brennan

Center for Justice at New York University School of Law and the University of North

Carolina School of Law Center for Civil Rights as Amici Curiae Supporting Plaintiff-

at 2 22 ^ 11 AbdUl Muntaqim and in SuPPort of Reversal (“Brennan Amicus Br.”),

23

II. THE “PLAIN MEANING RULE” OF STATUTORY

INTERPRETATION ESTABLISHES THAT SECTION 2 OF THE

VOTING RIGHTS ACT IS APPLICABLE TO NEW YORK’S

FELON DISFRANCHISEMENT REGIME, AND THE “CLEAR

STATEMENT RULE” HAS NO APPLICATION TO THIS CASE

(E n B a n c Q u e s t io n N o . 2)

On its face, the plain language of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which

expressly prohibits, without exception, any “voting qualification or prerequisite to

voting or standard, practice or procedure,” if it “results in a denial or abridgement of

the right to vote on account of race or color,” 42 U.S.C. § 1973(a), clearly applies to

§5-106. Under the “plain meaning rule,” the plain meaning of a statute controls its

interpretation, and “judicial review must end at the statute’s unambiguous terms.”

Schick v. Schmutz (In re Venture Mortgage Fund) 282 F.3d 185, 188 (2d Cir. 2002).

Applying the plain meaning rule to the unambiguous language of Section 2, it is clear

§5-106 is within its scope. As a matter of strict textual interpretation, it is indisputable

that §5-106, which prohibits certain individuals with felony convictions from

registering to vote, falls squarely within the purview of Section 2 as a “voting

qualification or prerequisite to voting” imposed by New York State. Although the

panel recognized that, “on its face, §1973 extends to all voting qualifications,” it

nevertheless, against the rules of statutory construction, concluded that the “clear

statement rule” was applicable, and precluded Appellants’ Voting Rights Act claims.

(ASA 00178 [Panel Op., at 129]).17

For further elaboration on these points, Appellants adopt and incorporate by

reference the Muntaqim Opening Br., at 9-15, and City Bar Amicus Br at 11-14

filed m support of Muntaqim.

24

In the face of nearly a century of systematic resistance to the Fifteenth

Amendment, Congress utilized expansive and aggressive language to define the scope

of the VRA and its amendments in order to achieve the Act’s ambitious remedial

purpose: to rid the country of racial discrimination in voting. The broad terms of

Section 2’s language, which extend the Act to cover any “voting qualification or

prerequisite to voting or standard, practice, or procedure,” 42 U.S.C. § 1973(a), is

identical to Section 5 s language, giving the Sections the same scope of coverage. See

Chisom, 501 U.S. at 401-02. Significantly, covered jurisdictions under the Voting

Rights Act have considered their felon disfranchisement laws to be within the scope

of Section 5, thereby requiring pre-clearance from the Attorney General for any

changes with respect to the same. See, e ^ , Allen v. Ellisor. 664 F.2d 391,399 (4th Cir.

1981), vacated as moot, 454 U.S. 807 (1981). There is simply no logical basis to

include felon disfranchisement laws within the scope of Section 5, while excluding

them from coverage under Section 2.18

Indeed, nothing in the plain language or legislative history of Section 2 indicates

that it cannot reach felon disfranchisement laws. The basic principle of the plain

meaning rule — that courts will not resort to legislative history to confuse clear

statutory text requires a recognition that, on its face, Section 2 is applicable to felon

disfranchisement laws. The panel, however, improperly relied on the legislative

For further elaboration on this point, Appellants adopt and incorporate by

reference the Muntaqim Opening Br., at 14-16, and En Banc Brief of Amici Curiae

the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, People for the American Way

Foundation, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and

National Black Law Students Association Northeast Region in Support of Appellant

and in Support of Reversal (“Lawyers’ Committee Amicus Br.”), at 11-12.

25

history of Section 4 of the Act, which is distinguishable by its language, operation and

purpose, from Section 2. (ASA 00177 [Panel Op., at 128]).19

Although the panel recognized that, “on its face, § 1973 extends to all voting

qualifications,” it nevertheless disregarded the established rules of statutory

construction and relied upon the “clear statement rule.” (ASA 00177-78 [Panel Op,,

at 128-29]). The panel s application of the clear statement rule is entirely inconsistent

with Supreme Court case law, which has held that statutory ambiguity is an absolute

prerequisite to the application of the clear statement rule. Pa. Dep’t of Corrs. v.

Yeskey, 524 U.S. 206, 210-212 (1998); Salinas v. United States. 522 U.S. 52, 60

(1997); Gregory, 501 U.S. 470. Remarkably, the panel, rather than declaring that

Section 2 was ambiguous, affirmatively acknowledged that “Section 1973, while

vague, does not seem ambiguous.” (ASA 00178 [Panel Op,, at 128 n.22]).

Accordingly, based on the panel’s own reasoning, the clear statement rule simply does

not apply.

The clear statement rule is inapplicable to §5-106 for yet another reason:

applying Section 2 to this state law does not alter the existing balance of federal and

state power, another prerequisite to the application of the rule. As the Supreme Court

noted, the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments “were specifically designed as an

expansion of federal power and an intrusion on state sovereignty.” Gregory. 501 U.S.

at 468. Thus, to the extent that the balance of power between the states and federal

For further elaboration on this point, Appellants adopt and incorporate by

reference the Muntaqim Opening Br., at 17-19, and Lawyers’ Committee Amicus Br.,

at 14 n.3, filed in support of Muntaqim.

26

government has been shifted, that shift occurred more than one century ago when the

Reconstruction Amendments were enacted. See generally Mitchum v. Foster 407 U.S.

225,238 & n.28 (1972)(recognizing the “basic alteration in our federal system wrought

in the Reconstruction era through federal legislation and constitutional amendment,”

and referring specifically to the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments).

Moreover, the Supreme Court refused to apply the clear statement rule to

Section 2 in Chisom, 501 U.S. 380, and Houston Lawyers’ Ass’n v. Attorney General.

501 U.S. 419 (1991), both of which were decided on the same day as Gregory. 501

U.S. 452, a case in which the Court applied the rule in a non-VRA context. To date,

the Supreme Court has not applied the clear statement rule to any section of the VRA

in any context.20 Accordingly, this Court’s application of Section 2 to New York’s

felon disfranchisement regime is in no way dependent upon a clear statement from

Congress.21

For further elaboration on these points, Appellants adopt and incorporate by

reference the Muntaqim Opening Br., at 19-26, and City Bar Amicus Br., at 16-22,

Brennan Amicus Br., at 22-30; and Lawyers’ Committee Amicus Br., at 14-25, filed

in support of Muntaqim.

21 Though its latest position represents a significant departure from both its well

settled and recent interpretations of Section 2, the United States Department of Justice

has long argued that the plain language of Section 2 prohibits the use of voting

standards, practices, or procedures that abridge the exercise of the vote on racial

grounds. Brief of the United States as Amicus Curiae in Support of Defendants-

Appellees at 25-33, Muntaqim (Nos. 01-7260-cv, 04-3886-pr)(“Brief of United

States”). Far from suggesting that the clear statement rule applies to the Voting Rights

Act, the United States has assumed that certain voting practices are squarely within

the scope of the Act where Congress did not expressly state that such practices were

excluded. It its brief in Chisom v. Roemer. for example, the United States explicitly

recognized that since “[n]othing in the legislative history states that amended Section

2 does not apply to the election of state judges, or that the results test of Section 2(b)

does not apply to such elections[,]” the “text of amended Section 2 is therefore

controlling.” Brief for the United States at 19-20, Chisom (Nos. 90-757, 90-

27

Finally, even if the clear statement rule applied here, Section 2 satisfies the clear

intent requirement. Short of specifically including felon disfranchisement laws in the

text or legislative history, which would be inconsistent with the general construction

of Section 2, Congress could not have expressed its intent more clearly. Congress used

expansive language in Section 2 with the intent that it would reach all voting practices

that result in discrimination on the basis of race. The panel struggles mightily to

obscure this fact, arguing that the clear statement rule is not satisfied because there is

no explicit mention of disfranchisement laws in the text or legislative history of

Section 2, (ASA 00167, 176-177 [Panel O ^, at 115, 127-28]), but the Supreme Court

has not required Congress to list every conceivable law to which Section 2 applies. It

is sufficient to recognize that Section 2 prohibits any state voting restriction, including

1032)(emphasis added). In fact, the United States argued its reply brief in Chisom

that the clear statement rule was simply inapplicable, noting that “Congress passed the

Voting Rights Act for the express purpose of regulating the States’ electoral rules and

process and that “the Act should be read broadly so that it can achieve its remedial

purposes.” Reply Brief for the United States at 5-6, Chisom (Nos. 90-757 90-1032)

More significant for purposes of the instant appeal and consistent with its position in

v.hisQm, the United States has assumed that the Voting Rights Act applies to felon

disfranchisement Jaws challenged in Johnson v. Gov, of Fla, and applied the “totality

of circumstances” test to Florida’s law before concluding that “plaintiffs failed as a

matter of law to demonstrate discrimination that interacts with provisions that affect

the right to vote.” Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae Supporting Appellee

m Part and Urging Affirmance at 15. Johnson v. Gov, of Fla 353 F.3d 1287(11th Cir

2003)(No. 02-14469-CC). Similarly, the United States has simply been inconsistent

m its treatment of the relevance of legislative history in determining the scope of the

wo â̂ s coverage. Finally, though the United States now attempts use the

VRA s legislative history to narrow the Act’s scope to preclude application to New

York s felon disfranchisement statute, see Brief of United States, at 11 , the United

States recently mounted a VRA challenge that clearly was not expressly contemplated

S K eAAct’; legislative history. See Compl., U.S. v. Brown, et al.. (S.D. Miss.

2005)(No. 4:05- cv-33 TSL-AGN) (alleging, under the VRA, that Whites are

subjected to discrimination in voting on the basis of race).

28

New York’s felon disfranchisement law, which results in the denial or abridgement of

the right to vote on account of race or color. To hold that Congress intended to

exempt felon disfranchisement statutes from Section 2 scrutiny is to hold that Congress

intended to permit certain forms of racially discriminatory voter disfranchisement.

That surely was not Congress’s intent.22

III. PROOF REQUIRED TO ESTABLISH A CHALLENGE TO

§5-106(2) PURSUANT TO A VOTE DILUTION THEORY UNDER

SECTION 2 OF THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT (En B a n c Q u e s t io n

No. 3)

In their pre-consolidation amicus brief in support of appellant Muntaqim.

counsel for the Hayden Appellants answered specific questions posed by this Court

about the proof required to support a challenge to felon disfranchisement laws under

Section 2 of the VRA. Because Muntaqim withdrew his vote dilution claim, the

Hayden Counsel Amicus Brief limited its analysis to the theory of vote denial only.

However, because of the overlap in the substance of the analyses of both vote denial

and vote dilution claims, Hayden Appellants incorporate by reference the analysis of

the proof required to support a Section 2 challenge to felon disfranchisement laws, as

specified below. Hayden Appellants submit that the analysis required for a vote

dilution claim necessarily includes the same proof as a vote denial claim, in addition

to evidence that directly relates to the impact of the challenged voting procedure on the

ability of Blacks and Latinos to participate on an equal basis in the electoral process

as Whites. Accordingly, the following arguments supplement the analysis contained

For further elaboration on this point, Appellants adopt and incorporate by

reference the Muntaqim Opening Br., at 27-29.

29

m the Hayden Counsel Amicus Brief with respect to the claim of vote dilution

specifically raised in Hayden:

A. Disparate Impact of New York Election Law §5-106

Hayden Appellants incorporate by reference page 8 of the Havden Counsel

Amicus Brief and further state as follows:

Section 2 s application in both vote denial and vote dilution claims is triggered

upon sufficient allegations of disparate impact, and relief under the statute is

appropriate upon a showing that the electoral mechanism at issue is either intentionally

discriminatory or has a discriminatory result on account of race. See 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973(a). Hayden Appellants have alleged facts and statistical evidence of the racially

disparate impact of §5-106 sufficient to trigger application of the “results” test of

Section 2. In their First Amended Complaint, the Havden Appellants allege that

“[njearly 52% of those currently denied the right to vote pursuant to §5-106 are Black

and nearly 35% are Latino. Collectively, Blacks and Latinos comprise nearly 87% of

those currently denied the right to vote pursuant to New York State Election Law

§5-106(2).” (ASA 00050 [FAC [̂68]). They further allege that disparities in

sentencing exacerbate the disparities in disfranchisement rates that flow from the

disproportionate incarceration of Blacks and Latinos:

66. Blacks and Latinos are sentenced to incarceration at substantially

higher rates than whites, and whites are sentenced to probation at

substantially higher rates than Blacks and Latinos. For example, in 2001

whites made up approximately 32% of total felony convictions, yet

comprised 44% of those who received probation and only 21.4% of those

incarcerated for felony convictions. By contrast, Blacks made up 44% of

those convicted of a felony, yet approximately only 35% of those

sentenced to probation and over 51% of those sentenced to incarceration.

30

Latinos comprised 23% of those convicted of a felony, yet only 19% of

those sentenced to probation and over 26.5% of those sentenced to

incarceration.

67. In addition. Blacks make up 30% and Latinos make up 14% of the

total current population of persons sentenced to probation in New York

State, while whites make up 51% of such persons.

14 (ASA 00050 [FAC 66-67]).

As a result, “[although Blacks make up approximately 15.9% of New York

State s overall population (as reported in the 2000 Census), they make up 54.3% of the

current prison population and 50% of the current parolee population in New York

State.” 14 (ASA 00049 [FAC f 62]). Similarly, “[although Latinos make up

approximately 15.1% of New York State’s overall population (as reported in the 2000

Census), they make up 26.7% of the current prison population and 32% of the current

parolee population in New York State.” 14 (ASA 00050 [FAC f 63]). Together,

Blacks and Latinos make up 86% of the total current prison population and 82% of

the total current parolee population in New York State, while they approximate only

31% of New York State’s overall population.” Id (ASA 00050 [FAC ]J 64]). These

allegations adequately establish the disparate impact of §5-106 on Blacks and Latinos

in New York State.

B. Totality of the Circumstances Test

Hayden Appellants incorporate by reference pages 8-29 of the Havden Counsel

Amicus Brief and further state as follows:

Like vote denial claims, the theory of vote dilution requires an analysis of

evidence of racial disparities in the criminal justice system as part of the totality of

31