Carey v. Klutznick Brief of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

February 9, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Carey v. Klutznick Brief of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund as Amicus Curiae, 1981. 8a2a1ac4-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0cf7d71c-9df1-474e-ac68-d9ab627f6beb/carey-v-klutznick-brief-of-the-naacp-legal-defense-and-educational-fund-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

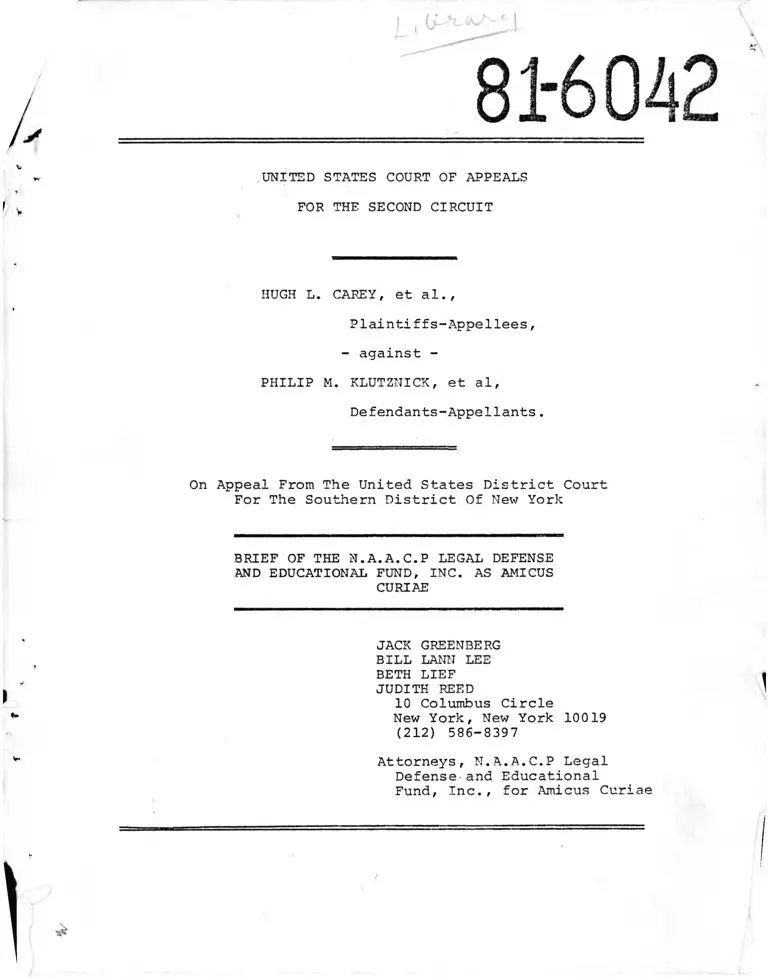

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

HUGH L. CAREY, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

- against -

PHILIP M. KLUTZNICK, et al,

Defendants-Appellants.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Southern District Of New York

BRIEF OF THE N.A.A.C.P LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. AS AMICUS

CURIAE

JACK GREENBERG

BILL LANN LEE

BETH LIEF

JUDITH REED

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Attorneys, N.A.A.C.P Legal

Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., for Amicus Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Interest of Amicus ............................... .. 1

Summary of Argument ................... ,........... 2

Argument

I. An Accurate Census Count, Particularly of

Blacks and Other Minorities, Is Crucial to

the Vindication of Civil Rights .......... 4

1. Jury Discrimination Cases ............ 5

2. Employment Discrimination Cases ..... 7

3. Challenges to Voluntary Affirmative

Action Plans .......................... 11

4. Housing Discrimination Cases ........ 13

II. The Census Undercount Directly and Indirectly

Imperils Enforcement of The Voting

Rights Act ................................ 16

Conclusion .......................................... 19

- l -

'i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Afro American Patrolmens League v. Duck,

503 F .2d 294 (6th Cir. 1974) ................

Alabama v. United States, 304 F.2d 583

(5th Cir. 1962 ), a f f 'd per curiam,

371 U.S. 37 (1962) .............................

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405

(1975) ............................................

Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625

(1972) ...........................................

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

Corp. , 429 U.S. 252 (1977) ................... 6 #

Baker v. City of Detroit, 483 F. Supp.

930 (E.D. Mich. 1979) .........................

Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v. Members of

Bridgeport Civil Service Comm.,

482 F .2d 1333 (2d Cir. 1973 ) ................

Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Company,

457 F .2d 1377 (4th Cir. 1972) ...............

Bush v. Kentucky, 107 U.S. 110 (1883) .........

Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482 (1977) ....6,7,

City of Hartford v. Hills, 408 F. Supp.

889 (D. Conn. 1976 , rev 1d on other

grounds sub n o m . City of Hartford v. Towns

of Glastonbury, 561 F.2d 1032 (2nd Cir. 1977)

(en banc) cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1034 (1978)...

Coalition for Block Grant Compliance v. HUD,

450 F. Supp. 43 (E.D. Mich. 1979) .........

Detroit Police Officers Association v.

Young, 608 F.2d 671 (6th Cir. 1979) ....... 2,

Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321 (1977) .... 9,

Erie Human Relations Comm. v. Tullio, 493

F .2d 371 (3rd Cir. 1974) .....................

Cases: Page

10

5

15

6

14

12

10

9

6

14

14

14

12

10

10

1 1

Cases: Page

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.,

424 U.S. 747 (1976) ........................... 15

Fullilove v. Klutznick, _____ U.S. _____,

65 L. Ed. 2d 902 (July 2 , 1980) ............ 12

Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S.

285 (1969) 18

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339

(1960)............................................. 7

Gore v. Turner, 563 F.2d 159 (5th Cir. 1978). .2,21

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S.

424 (1971) 10,14

Hazelwood School District v. United States,

433 U.S. 299 (1977) 10,15

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 (1954) ...... 2,6

Hills v. Gautreaux, 425 U.S. 284 (1976) 14

International Brotherhood of Teamsters

v. United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977). .2,8,9,10

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber,

491 F. 2d 1372 (5th Cir. 1974) 10

Jones v. Lee Way Motor Freight, Inc. ,

431 F. 2d 245 (10th Cir. 1970) 9

Jones v. Mayer, 392 U.S. 268 (1939) 13

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268 (1939) 19

League of United Latin American Citizens

v. City of Santa Ana, 410 F. Supp. 873

(C.D. Cal. 1976) 11

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145

(1965) 15

Marquez v. Omaha District Sales Office,

Ford Division, 440 F.2d 1157

(8th C i r . 1971) 9

NAACP v. Allen, 493 F.2d 614 (5th Cir.

1974) 11

Otero v. New York City Housing Authority,

484 F . 2d 1122 (2d Cir. 1973 ) ............ 13,14

- i i i -

Cases: Page

Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone

Co., 433 F . 2 d 421 (8th Cir. 1970) ........................ 9,10

Patterson v. Newspaper & Mail Del. Union

of N.Y. & Vicinity, 514 F.2d 767

• (2d C i r . 1975) ............................................... 10,15

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe

Company, 494 F.2d 211 (5th Cir. 1979) ................. 9,10

Quon v. Stans, 309 F. Supp. 604

(N.D. Cal. 1970) ............................................ 18

Resident Advisory Board v. Rizzo, 564

F . 2 d 1 2 6 (3rd Cir. 19 77).................................. 13

Rios v. Enterprise Ass'n Steamfitters,

Loc. U. No. 638 of U.A., 501 F.2d 622

(2d Cir. 1974) 11,15

Rose v. Mitchell, 443 U.S. 545 (1979) ..................... 5,6

Shannon v. HUD, 436 F.2d 809 (3rd Cir.

1970) 14

Sims v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 538 (1967) ....................... 6

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940) 7

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S.

301 (1966) 17

Stamps v. Detroit Edison Co., 365 F. Supp.

87 (E. D . M i c h . 1973 ) ..................... ................. 11

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S.

303 (1880) 6

Torres v. Sachs, 381 F. Supp. 309

(S.D.N.Y. 1974) 16

Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life

Insurance Company, 409 U.S. 205 (1972) ................. 13

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970) ...................... 6

United Jewish Organizations v. Carey, 430

U.S. 144 (1977) ............................................ 2 ,16,18

United States v. City of Black Jack,

508 F . 2 d 1179 (8th Cir. 1974) .......................... 13

V

iv

Cases: Page

United States v. City of Buffalo, 457

F. Supp. 612 (W.D.N.Y. 1978) .............................. 11

United States v. City of Buffalo,

_____ F .2d _____, 24 FEP Cases 313

(2nd C i r . 1980) ................................ ............. 11

United States v. City of Miami, Fla., 614

F . 2d 1322 (5th Cir. 1980) ................................. 2,11

United States v. Hayes I n t '1 Corp., 456

F . 2 d 112 (5th Cir. 1972) .................................. 10

United States v. Ironworkers Local 86

443 F .2 d 544 (9th Cir. 1971), ce r t .

denied 404 U.S. 984 (1971) ............................... 8

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Company

451 F . 2 d 442 (5th Cir. 1971) ............................. 9

United States v. Pelzer Realty Company,

Inc., 484 F . 2d 438 (5th Cir. 1973) ..................... 13

United States v. Youritan Construction

Company, 370 F. Supp. 643 (N.D. Cal.

1973), aff ' d 509 F.2d 623 (9th Cir.

1975) ......................................................... 13

United Steelworkers of America v. Weber,

443 U.S. 193 (1979) ....................................... 8,12

University of California Regents v. Bakke,

438 U.S. 265 (1978) ....................................... 18Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976)................ 6,7

West End Neighborhood Corp.v. Stans, 312

F. Supp. 1066 (D.D.C. 1970) ............................. 18

Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967)................... 6

Williams v. Matthews Company, 499 F.2d

819 (8th Cir. 1974) , c e r t . denied

419 U.S. 1021 (1974) ..................................... 13

Zuch v. Hussey, 394 F. Supp. 1028

(E.D. Mich, 1975) ......................................... 13

v -

Page

STATUTES

42 U.S.C § 1971 , 1973 et se q ........................... 4

42 U.S.C. § 1973(a) & (b) 2, 16

42 U.S.C. § 1973b(f) (3) 17

42 U.S.C. § 2000a et s e q ................................ 5

42 U.S.C. § 2000d et s e q .................................. 5

42 U.S.C. § 2000e et s e q .................................. 4, 15

42 U.S.C. § 3601 et s e q ................................... 4, 14

42 U.S.C. § 3601 et seq. (Supp. V 1975) 14

42 U.S.C. § 3 7 6 6 (c)(1) ................................... 4

42 U.S.C. § 5304 (a) (4) 14

OTHER AUTHORITIES

110 Co n g . R e c ............................................... 8

Schlei and Grossman, Employment Discrimination

Law (BN A 1976) ......................................... 8

- vi -

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

No. 81-6042

HUGH L. CAREY, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

PHILIP M. KLUTZNICK, et al,

Defendants-Appellants.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Southern District Of New York

BRIEF OF THE N.A.A.C.P. LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AS AMICUS

CURIAE

Interest of Amicus

The N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., is a non-profit corporation established under the laws of

the State of New York. It was founded to assist black persons

to secure their constitutional and statutory rights by the pro

secution of lawsuits. Its charter declares that its purposes

include rendering legal services gratuitously to black persons

suffering injustice by reason of racial discrimination. For

many years attorneys of the Legal Defense Fund have represented

parties in litigation before this Court, the Supreme Court and

other courts involving a variety of race discrimination cases.

The success of many of the claims in these cases have been de

pendent upon use of census statistics. See, e.g. United Jewish

Org. of Williamsburgh v. Wilson, 510 F.2d 512 (2nd Cir. 1975),

aff'd sub. nom. United Jewish Org. of Williamsburgh v. Carey,

430 U.S. 144 (1977)(voting rights); Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. 424 (1971)(employment discrimination); Detroit Police

Officers Assn, v. Young, 608 F.2d 671 (6th Cir. 1979)(challenge

to voluntary affirmative action plan); Gore v. Turner, 563 F.2d

159 (5th Cir. 1978)(housing discrimination). The Legal Defense

Fund believes that its experience in such litigation and the

research it has performed will assist the Court in this case.

The parties have consented to the filing of this brief and

letters of consent have been filed with this Court.

Summary of Argument

The use of census figures has been central to proof of

discrimination in the areas of jury discrimination, employment

and housing discrimination. See, e.g., Hernandez v. Texas, 347

U.S. 475 (1954) and Int'l Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977). Courts have also relied upon census

figures in shaping affirmative remedies for discrimination. Se^

e.g. United States v. City of Miami, Fla., 614 F.2d 1322 (5th

Cir. 1980). An accurate census count is, therefore, crucial to

the enforcement of the various civil rights laws and the inte

grity of the judicial process.

2

Any mismanagement of the census count directly and

indirectly imperils enforcement of the Voting Rights Act of

1965. The provisions of the Act require a determination of

voter registration and participation, by race. That deter

mination is made by the Director of the Census. 42 U.S.C.

§1973(a) & (b). Effective enforcement of the Act is, to some

extent dependent upon the accuracy of that determination. In

a separate but related way, the methodology employed in the

1980 census, specifically the "mail out - mail back" alternative

is tantamount to utilizing a literacy test — something clearly

forbidden by Section 4 of the Act.

3

ARGUMENT

I.

An Accurate Census Count, Particularly of Blacks

And Other Minorities, Is Crucial to The

Vindication of Civil Rights

The briefs and opinions in this action have focused

the importance of an accurate census count on two uses to which

the tabulations are put, a state's representation in Congress

and its receipt of federal funds. Although not discussed by

either the parties or the district court, the impact of the

census is not limited, to these admittedly important areas. An

accurate census count, particularly of blacks, Hispanics and

other minorities, is crucial to the preservation of consti

tutional and statutory guarantees of equality, the enforcement

of basic civil rights, and the integrity of our judicial system.

Since enactment of the Fourteenth Amendment, the

Constitution of the United States has guaranteed the right to be

free from discrimination by the State on the basis of race. From

the years immediately following the Civil War until the present'

Congress has extended the prohibition against race discrimination

1/ 2/ 3/

to cover, among other areas, voting, employment, housing, public

1/ E.g., Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1971, 1973,

et seq.

2/ E.g., Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e et seq., Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of

1968 as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 3766(c)(1).

3/ E.g., Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C.

§ 3601, et seq.

Experience

4/ 5/

accommodations and the dispersal °f federal funds.

has taught, however, that the passage of new laws does not

automatically marshall change in behavior. As a consequence,

vindication of basic civil rights has consistently been,and

remains largely,the task of the judiciary. In cases alleging

a violation of civil rights laws and constitutional guarantees,

6/

as the "Statistics often tell much, and Courts listen." Indeed,

discussion below demonstrates, census figures have been

the key to judicial enforcement of civil and constitutional

rights. Inaccurate census figures, especially where inaccura

cies undercount blacks and other minorities, not only makes

proof of violations more difficult; it undermines the judicial

fact-finding process in such cases,

1. Jury Discrimination Cases

The Supreme Court has repeatedly recognized that

"Discrimination on the basis of race, odious in all aspects, is

especially pernicious in the administration of justice , . .

[because it] destroys the appearance of justice and thereby casts

doubt on the'integrity of the judicial process." Rose v, Mitchell,

443 U.S. 545, 555-56 (1979). For over 100 years the Supreme

Court has held that the exclusion from grand jury service of

members of a particular race violates the Fourteenth Amendment.

4/ E.g., Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C,

§ 2000a et seg.

5/ Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C, § 2000d

et seg.

6/ Alabama v. United States, 304 F .2d 583, 586 (5th Cir, 1962),

aff1d per curiam, 371 U.S. 37 (1962),

5

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880) . While the early

jury exclusion cases were challenges to the explicit exclusion of

7/

blacks, more recent cases have challenged the virtual absence in

8/

fact of blacks, and other minorities from grand jury service.

These later cases "established the principle that substantial

underrepresentation of the [minority] group constitutes a con

stitutional violation . . . if it results from purposeful

discrimination." Castenda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482, 493 (1977),

The abandonment of explicit statutory exclusion has made the use

of census figures central to proof of discrimination in the

selection of grand and petit juries. Thus, in Hernandez v. Texas,

347 U.S. 475, 480 (1954) the Court focused on a comparison of

the proportion of Hispanics in the total population to the

proportion called to serve as grand jurors. See also Turner v.

Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970), Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625

(1972), Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967), and Sims v, Georgia,

385 U.S. 538 (1967). Notwithstanding a requirement that a

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment must be tied to a finding of

2/purposeful discrimination, the Supreme Court has held that a

comparison of census figures to grand jury lists which showed a

substantial underrepresentation of a particular minority group

7/ E.g., Bush v. Kentucky, 107 U.S. 110 (1883); Strauder v.

West Virginia, 100 U.S, 303 (1880).

8/ E.g., Rose v. Mitchell, 443 U.S. 545 (1979); Sims v. Georgia,

385 U.S. 538 (1967); Alexander v, Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625 (1972);

Castenada v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482 (1977); Turner v', Fouche, 396

U.S. 346 (1970); Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967); Hernandez

v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 (1954).

9/ Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976); see Arlington

Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Corp,, 429 U.S, 252. 264-265 (1977).

- 6 -

constituted a prima facie case of discriminatory purpose.

Castenada v, Partida, supra, 430 U.S. at 494-495. Thus,

although discrimination in the selection of jurors "is at

war with our basic concepts of a democratic society and a

10/

representative government," without an accurate count of blacks,

Hispanics and other minorities, plaintiffs and the courts lack

the weapons to battle this evil.

In cases involving other alleged violations of the

Equal Protection Clause, the use of statistics may be equally

crucial. Although the Supreme Court has held that proof of

discriminatory impact alone is insufficient to establish a

violation of the equal protection clause „ the Court

has made clear that discriminatory impact is often the touch

stone to a finding of invidious purpose. Washington v. Davis,

426 U.S. 229, 241-242 (1976); Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan

Housing Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 266 (1977). If a disparate or

adverse racial impact is sufficiently large that it is unlikely

that it is due solely to chance or accident, and in the absence

of evidence to the contrary, the Court may conclude that racial

or other class related factors entered into the decision-making

process. Id. That impact is often, if not usually, demon

strated by resort to census figures. See, e .g ., Gomillion v.

Liahtfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (I960) (reapportionment in violation of

Fifteenth Amendment)

2. Employment Discrimination Cases

The prohibition in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

10/ Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S, 128, 130 (.1940) ,

7

of 1964 against race discrimination in employment was Congress'

attempt to remedy the plight of the black person in this

country's economy. 110 Cong. Rec. 6543 (Remarks of Sen. Humphrey);

id. at 7204 (Remarks of Sen. Clark) id. at 7379-7380) (Remarks

of Sen. Kennedy). As of 1964, the rate of Black unemployment had

gone up consistently as compared with white unemployment for the

previous 15 years. Id. at 7220 (Remarks of Sen. Clark). As the

Supreme Court recognized:

Congress feared that the goals of the

Civil Rights Act — the integration

of Blacks into the main stream of

American society — could not be

achieved unless this trend was re

versed. And Congress recognized

that that would not be possible unless

Blacks were able to secure jobs "which

have future."

United Steelworkers of America v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193 (1979), 202-

203. The successful use of Title VII as a vehicle to open employ

ment opportunities for blacks and other minorities has been tied

directly to the use of census figures. Indeed, as one commentator

has noted, "Perhaps the most significant development in employment

discrimination law has been the dominant role that statistics have

come to play in the trial of virtually all class actions." Schlei

and Grossman, Employment Discrimination Law, 1161. Indeed, in

many cases, " [T]he only available avenue of proof is the use of

racial statistics to uncover clandestine and covert discrimination

by employer or union involved." International Brotherhood of

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 339, n. 20 (1977) citing

United States v. Ironworkers Local 86, 443 F .2d 544, 551 (9th Cir.

1971), cert, denied 404 U.S. 984 (1971). See also, e .g ., Pettway

- 8 ~

v. American Cast Iron Pipe Company, 494 F.2d 211, 225, n. 34

(5th Cir. 1974); Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Company,

457 F.2d 1377, 1382 (4th Cir. 1972); United States v. Jacksonville

Terminal Company, 451 F.2d at 442 (5th Cir. 1971); Parham v.

Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., 433 F.2d 421, 426 (8th Cir. 1970);

Jones v. Lee Way Motor Freight, Inc., 431 F.2d 245, 247 (10th Cir.

1970). Such evidence is often "the only available avenue of proof"

since discrimination "will seldom be admitted by any employer."

Marquez v. Omaha District Sales Office, Ford Division, 440 F.2d

1157, 1162 (8th Cir. 1971). As the Supreme Court has explained,

statistics are crucial because

Absent explanation, it is ordinarily to be

expected that non-discriminatory hiring

practices will in time result in a work

force -more--or less representative of the

racial and ethnic composition of the

population in the community from which

employees are hired.

Teamsters v. U.S., supra, 431 U.S. at 340, n. 20. Although courts

in employment discrimination cases have looked to statistics other

than those based upon census figures (for example, statistics of

actual applicants to a job), the Supreme Court has made clear that

there is no requirement that a statistical showing of dispropor

tionate impact be based on an analysis of the characteristics of

actual applicants. Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321, 330 (1977).

Indeed, if actions by the employer have had the effect of lowering

artificially the number of minority applicants to a job, resort

to census figures may well be the best basis for analysis. I d .

Thus, the Supreme Court has repeatedly sanctioned the use of census

figures to make out a prima facie case. See, e .g ., Teamsters v.

9

u.s., supra, Dothard v. Rawlinson, supra,, Griggs v. Duke Power

Co., 401 U.S. 424, 430 (1971). In cases alleging discrimination

by private employers and unions, the Supreme Court has speci

fically approved comparisons between an employer's workforce and

the general population, stating that such comparisons can pro

vide "significant" proof of discrimination. Teamsters v. U.S.,

supra , 431 U.S. at 337, n. 17 and 339-40, n. 20 (1977). Accord,

Hazelwood School District v. United States, 433 U.S. 299, 308,

n. 13 (1977); Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491 F.2d 1372

11/

(5th Cir. 1974). This Court has held that a discrepancy "between

a minority community population and employment population" at the

very least will "invite inquiry." Bridgeport Guardians Inc, v.

Members of Bridgeport Civil Service Comm., 482 F .2d 1333, 1335 n.

4 (2d Cir. 1973). See also Patterson v. Newspaper & Mail Del.

Union of N.Y. & Vicinity, 514 F.2d 767, 772 (2d Cir. 1975). Other

circuits have similarly recognized that data demonstrating adverse

impact often is founded upon population statistics. Pettway v .

American Cast Iron Pipe Company, 494 F. 2d 211, 225 n. 34 (5th Cir

1974). Erie Human Relations Comm, v. Tullio, 493 F.2d 371, 373

n. 4 (3d Cir. 1974); United States v. Hayes Int'l Corp,, 456 F.2d

112, 120 (5th Cir. 1972); Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co

433 F .2d 421, 426 (8th Cir, 1970),

11/ Use of census figures is a key element to Title VII cases

regardless of whether the case is brought as a disparate treatment

or adverse impact case. A showing of a disparity between the

percentage of minorities in the general population and the per

centage of minorities in the workforce may in itself be sufficient

to establish plaintiffs' prima facie case, e .g ., Griggs v. Duke

Power, supra. In a disparate treatment case, or cases based on

intentional discrimination, statistical evidence based on census

figure may be highly probative and virtually prove a prima facie

case. Teamsters v. U.S., supra.

10

The use of census figures has been no less crucial in

cases which challenge employment discrimination by governmental

agencies. Courts have looked to comparisons of the percengage

of minority residents in the service area and the percentage of

minorities employed when considering discrimination claims

involving municipal police and fire departments. See, Afro

American Patrolmens League v. Duck, 503 F.2d 294, 299 (6th Cir.

1974). United States v. City of Buffalo, 457 F. Supp. 612, 621

(W.D.N.Y. 1978), aff'd_____ F.2d ____, 24 FEP Cases 313 (2d Cir.

1980). League of United Latin American Citizens v. City of Santa

Ana, 410 F. Supp. 873, 896-98 (C.D. Cal. 1976).

Similarly, courts of this and other circuits which have

ordered affirmative action relief to remedy employment dis

crimination have looked to census figures which show the minority

population in the community in order to determine appropriate

quotas and goals. E.g., United States v. City of Buffalo, ____F.2d

_____ f 24 FEP Cases 313 (2d Cir. 1980); United States v. City of

Miami, Fla., 614 F.2d 1322, 1339 (5th Cir. 1980) (proper goal to

"obtain percentages of [minorities] generally consistent with their

percentages in the community."); NAACP v. Allen, 493 F.2d 614,' 617,

n. 3 (5th Cir. 1974); Stamps v. Detroit Edison Co., 365 F. Supp.

87, 122, n. 4 (E.D. Mich. 1973); Rios v. Enterprise Ass'n Steam-

fitters, Loc. 638, U. No. of U.A., 501 F.2d 622, 633 (2d Cir. 1974)

(". . . the court should be guided by the most precise standards

and statistics available . . . .").

3. Challenges to Voluntary Affirmative Action Plans

Accurate census count of the minority population has

T 11

become crucial in cases where private and governmental employers

face challenges to affirmative action plans. In United Steel

workers of America v. Weber, supra, the Supreme Court upheld the

right of a private employer to institute a voluntary race

conscious affirmative action plan “to eliminate traditional

patterns of racial segregation,"' supra, 443 U.S, at 201. The

legality of a particular affirmative action plan can be directly

related to the extent to which the goals of the plan reflect the

composition of the relevant labor force. Id, at 208-209, 214

(Blackmun, j., concurring). Thus, in Weber, the Supreme Court

upheld a preferential program related to the percentage of blacks

in the general population in the community, as determined by

census data. See 415 F. Supp. 761, 764 (E.D. La, 1976). Where

voluntary affirmative action plans are established in the govern

mental sector, the justification for such plans, past dis

crimination, has been determined in large part by the statistical

disparity between the percentage of black employees and both the

percentage of blacks in the labor pool and the general population

in the community, Detroit Police Officers Association v. Young,

608 F.2d 671 (6th Cir. 1979). Baker v. City of Detroit, 483 F.

Supp. 930 (E.D. Mich, 1979). , Census data was both the direct and

indirect method by which the legality of affirmative action

plans in these cases was analyzed. The constitutionality of

Congressional actions which include race-conscious attempts to

remedy past discrimination are dependent upon resort to census

data. Fullilove v. Klutznick, ____ U.S. ____, 65 L.Ed.2d 902,

916 (July 2, 1980).

12

4. Housing Discrimination Cases

As the Supreme Court stated in Trafficante v.

Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, 409 U.S. 205 (1972) Title

VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, which bans discrimination

in the sale and rental of housing, must be generously construed

in order to carry out a policy to which Congress accorded "the

12/ 13/

highest priority." As this Court and other circuits and the

14/Supreme Court have recognized, the fair housing laws are the

critical vehicle for removing the scourge of slavery,and for

securing the equal right to rent or buy housing for all persons,

whatever the color of their skin. As in employment discrimination

cases, actual enforcement of the rights guaranteed by the fair

housing laws often depend upon comparisons between the percentage

of minorities in the population, as given in census data, and the

percentage of minorities in the particular housing at issue. Thus,

census data has been crucial to challenge involving the refusal

to build public housing, e .g ., United States v. City of Black Jack,

508 F .2d 1179, 1183 (8th Cir. 1974), Resident Advisory Board v.

Rizzo, 564p .2d 126 (3rd Cir. 1977), the relocation of public

12/ Otero v. New York City Housing Authority, 484 F .2d 1122,

TI33 (2d Cir, 1973),

13/ E.g., Zuch v. Hussey, 394 F. Supp, 1028 (E.D, Mich. 1975),

aff1 d~, 547 F . 2d 1168 (6th Cir. 1977); United States v. Youritan

Construction Company, 370 F, Supp, 643 (N.D. Cal, 1973), aff1d

509 F.2d 623 (9th Cir. 1975); Williams v, Matthews Company, 499

F .2d 819 (8th Cir. 1974), cert, denied 419 U.S. 1021 (1974);

United States v. Pelzer Realty Company, Inc., 484 F.2d 438 (5th

Cir, 1973),

14/ E.g., Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Insurance Company,

supra; Jones v. Mayer, 39.2 U.S, 26 8 (.1939) (.42 U.S.C, § 1982).

13

housing, e .g ., Hills v. Gautreaux, 425 U.S. 284 (1976); Shannon

v. HUD, 436 F.2d 809 (3rd Cir. 1970), the selection of tenants

for public housing, Otero v. New York City Housing Authority,

supra, and the zoning for low income housing, Arlington Heights

v. Metropolitan Housing Corp., supra.

The ability of a locality to receive federal funds

under the Housing and Community Development Act of 1974, 42 U.S.C.

§ 3601 et seq. (Supp V 1975), is also keyed to an accurate census

count. In order to receive a Community Development Block Grant,

a governmental applicant must prepare a Housing Assistance Plan

(HAP) to demonstrate how it will provide, inter alia, suitable

low-income housing for persons residing and "expected to reside"

in the area. 42 U.S.C, § 5304(a)(4). An undercount of the

population distorts the validity of the HAP, frustrating the

Congressional intent to insure the provision of housing for those

needing it. See, in general, City of Hartford v. Hills, 408 F.

Supp. 889, 893-94, 902 (D. Conn, 1976), rev*d on other grounds sub

nom- City of Hartford v. Towns of Glastonbury, 561 F.2d 1032

(2d Cir. 1977) (en banc) , cert, denied 434 U.S. 1034 (1978) ;

Coalition for Block Graht Compliance v. HUD, 450 F. Supp. 43

(E.D. Mich. 1978).While many findings of discrimination are

based on gross disparities between,for example, minority em-

, 15/

ployees and minority population figures findings of discrimina

tion can hinge on a 5-10% difference in the proportion of

minorities as counted in the census. Thus, in

15/ E .g ., Griggs v. Duke Power Co., supra (employment);

Castenada v. Partida, supra (voting); Arlington Heights v.

Metropolitan Housing Authority, supra (zoning).

14

Hazelwood School Dist. v. United States, supra, a dispute arose

as to whether the proper percentage of minority school teachers

in the labor force was 5.7% or 15.4%. The Supreme Court noted

that this difference "may well be important" in determining

whether a Title VII violation exists. 433 U.S. at 311.

Similarly, an undercount of blacks and other minorities, by even

five to ten percentage points, can dramatically affect the scope

of relief ordered by a court and the legitimacy of a particular

voluntary affirmative action plan. Cf., Patterson v. Newspaper

& Mail Del. Union of N.Y. & Vicinity, 514 F,2d 767, 772 (2d Cir.

1975) (court ordered goal had adequate basis in refined census

figures); Rios v. Enterprise Ass'n Steamfitters, Loc. U. No. 638

of U.A. , 501 F.2d 622, 633 (.2d Cir. 1974). Thus, misrepresenta

tion in the census of the actual number and percentage of minori

ties impedes the ability- of plaintiffs to establish the violations

of civil rights laws and of courts consistent with constitutional

and Congressional mandate, to "fashion the most complete relief

16/

possible"-in order to "eliminate the discriminatory effects of

17,/

the past as well as bar like discrimination in the future."

16/ Franks v. Bowman Transp, Co., 424 U.S. 747, 764 (1976).

17/ Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S, 405, 418 (1975),

quoting from Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145, 154 (1965)

15

I I .

The Census Undercount Directly And Indirectly

Imperils Enforcement of The Voting

Rights Act

The undercount found by the district court directly

imperils enforcement of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as

amended, 42 U.S.C. § 1973b (Supp. 1980), in New York State.

See, United Jewish Organizations v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144 (1977)

(application of the Act to Kings, New York and Bronx counties of

New York State); Torres v. Sachs, 381 F. Supp. 309 (S.D.N.Y.

1974) (application of bilingual provisions of the Act to New York

City). Section 4 of the Act provides, inter alia, that: "To

assure that the right of citizens of the United States to vote is

not denied or abridged on account of race or color, no citizen

shall be denied the right to vote in any Federal, State, or Local

election because of his failure to comply with any test or device

in any State [or any political subdivision of a State] with

respect to which . . .

Cl) the Attorney General determines main

tained on November 1, 1964 [November 1,

1968 or November 1, 1972], any test or

device, and with respect to which (2) the

Director of the Census determines that

less than 50 per centum of the persons of

voting age residing therein were registered

on November 1, 1964 [November 1, 1968 or

November 1, 1972], or that less than 50

per centum of such persons voted in the

presidential elections of November 1964

[November 1968 or November 1972]

42 U.S.C. § 1973(a) & (b) (emphasis added). In addition, the

bilingual requirements of 1973b(f) are triggered "where the

Director of the Census determines that more than five per centum

of the citizens of voting age residing in such State or political

16

42 U.S,C.subdivision are members of a single language minority,"

§ 1973b(f)(3). Section 1973k makes determination of the Acts'

procedures for federal voting examiner listing of eligible voters

in any State or political subdivision contingent, in part, on

whether "the Director of the Census has determined that more than

50 per centum of the non-white persons of voting age residing

therein are registered to vote." See, South Carolina v. Katzenbach,

383 U.S. 301 (1966).

Section 4 also provides, in pertinent part, that "[a]

determination . . . of the Director of the Census under this

section or under section . . . 1973k or this title shall not be

reviewable in any court and shall be effective upon publication

in the Federal Register." The Supreme Court upheld the provision

for nonreviewability of census determinations in part because "the

findings not subject to review consist of objective statistical

determinations by the Census Bureau," South Carolina v. Katzenbach,

supra, 383 U.S. at 333 (emphasis added). Unless the district

court's opinion is affirmed, the integrity of the Director of the

Census' determinations under §§ 1973b and 1973k for New York State

and, therefore, Voting Rights Act enforcement will come under

question.

Moreover, voting rights enforcement is frustrated in

another way. The lower court found that as a result of mismange-

ment, the census was essentially based on responses on written

English language "mail out, mail back" forms. From the beginning

of the Republic through the 1960 census, the census was taken by

17

door-to-door enumeration. In 19.7Q, the mail out, mail back

method, which included supplementary pre-rcanvassing and post

mailing safeguards, was instituted, See,NQuon v. Stans, 309

F. Supp, 604, 605 (N.D, Cal. 19701, In particular, the

Census Bureau concentrated supplementary efforts in con

gested urban areas. See, West End Neighborhood Corp, v, Stans,

312 F. Supp. 1066, 1069 CD.D.C, 197QJ, The existence of

supplementary "safeguarding procedures designed to count those

persons not counted initially by the mail-out-mail back method"

led several courts to validate the use of the mail, out mail

back method. See, e ,g ., Quon v. Stans,s supra, 309 F, Supp. at

606; West End Neighborhood Corp., supra, 312 F. Supp, at 1069,

The court below, however, found that in New York State in 1980,

the safeguarding procedures were largely unapplied or severely

mismanaged. The net result is that the census was

taken of the literate population only, This, we submit, is a

result at odds with the policy of the Voting Rights Act because

it covertly accomplishes what the Act prohibits.

Clearly, section 4 of the Act prohibits conditioning

the right to vote on any literacy test because to do so would

discriminate against black persons by perpetuating the effects of

racially segregated public education. Gaston County v. United

States, 395 U.S. 285, 293-297 Cl969}, This is true in New York

State, see United Jewish Organizations v, Carey, supra, where many

minority group members, as in California, "were born and reared

in school districts in Southern States segregated by law."

University of California Regents v, Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 372

18

(1978) (opinion of Brennan, White, Marshall and Blackmun,

J.J. concurring). Reliance on ability to read English

obviously also screens out those able to read, for example,

only Spanish or Chinese. Thus, the Census Bureau by

effectively imposing an unmitigated literacy test on census

enumeration accomplishes what the States are themselves

prohibited from doing directly under the Voting Rights Act.

The law prohibits "sophisticated as well as simple-minded

modes of discrimination." Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268,

275 (1939). While the impact of the census literacy test is

not to deprive minority persons of their right to vote,

it has invidious consequences through underrepresentation of

minority populations in apportionment and compromising the

integrity of Voting Rights Act enforcement, supra.

CONCLUSION

The judgment of the district court should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted

JACK GREENBERG

BILL LANN LEE

BETH LIEF

JUDITH REED

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2Q3Q

New York, New York 1QQ19

19

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae,

N ,A ,A ,C ,P , Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc,

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on the 9th day of February,

1981, I served the foregoing Brief of The N.A.A.C.P. Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. as Amicus Curiae by

placing three copies in the United States mail, first-class,

postage prepaid to the following counsel of record:

John S. Martin, Jr.

United States Attorney for the

Southern District of New York

One St. Andrews Plaza

New York, New York 10007

Robert Abrams

Attorney General of the

State of New York

Daniel Berger

Deputy Assistant Attorney General

Two World Trade Center

Suite 46-57

New York, New York 10047

Frederick A.O. Schwarz, Jr.

Cravath, Swaine & Moore

One Chase Manhattan Plaza

New York, New York 10005

Attorney for Amicus Curiae,

.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc.