United Steel Workers of America v. Webber Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United Steel Workers of America v. Webber Brief Amicus Curiae, 1979. 97bf07ec-c79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0d3babde-9e0b-476a-88c0-b6a5ca37adff/united-steel-workers-of-america-v-webber-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

J i

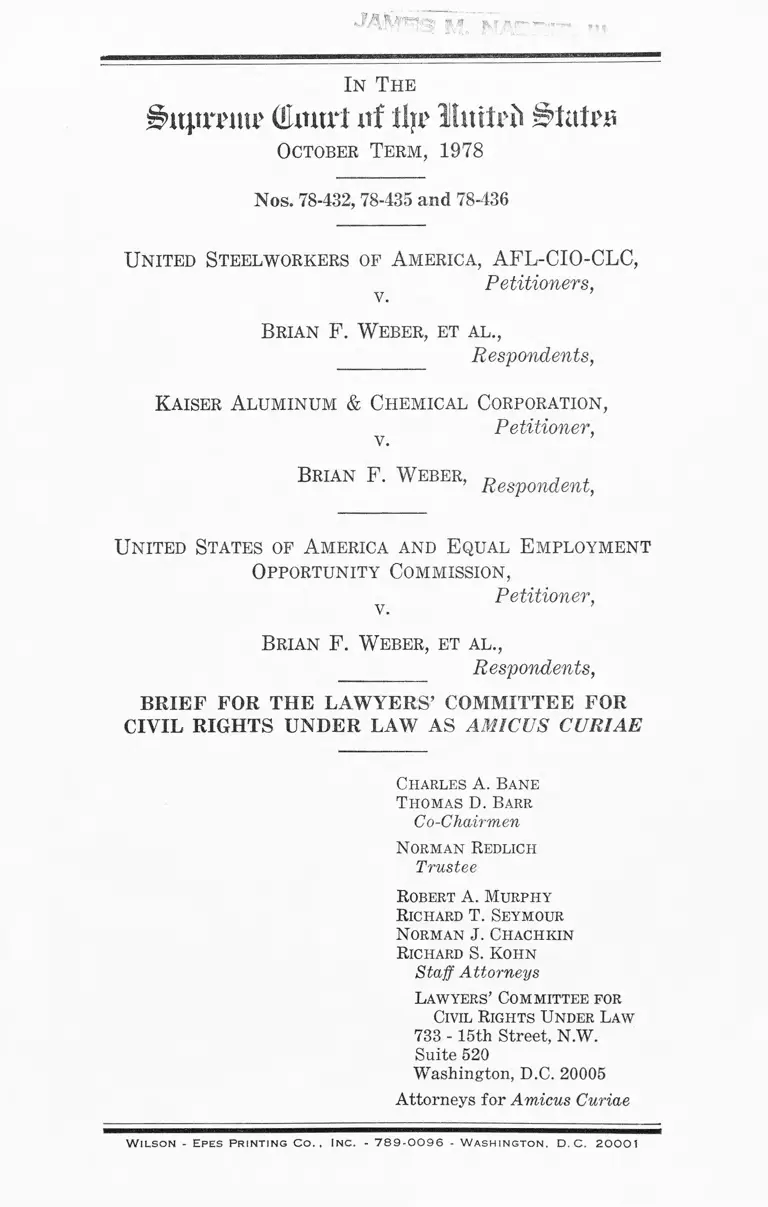

In T he

Jiutytm tu' (Eiu trl irf tl}V I m t r f t l^tatws

October Term, 1978

Nos. 78-432, 78-435 and 78-436

United Steelworkers of A merica, AFL-CIO-CLC,

Petitioners,v.

Brian F. W eber, et al .,

Respondents,

Kaiser A luminum & Chemical Corporation,

Petitioner,

Brian F. W eber, Respondent,

United States of A merica and Equal E mployment

Opportunity Commission,

Petitioner,v.

Brian F. W eber, et al.,

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ Respondents,

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS AMICUS CURIAE

Charles A. Bane

T homas D. Barr

Co-Chairmen

Norman Redlich

Trustee

Robert A. Murphy

Richard T. Seymour

Norman J. Chachkin

Richard S. Kohn

Staff Attorneys

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

733 - 15th Street, N.W.

Suite 520

Washington, D.C. 20005

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

W i l s o n - Ep e s P r i n t i n g C o . , In c . - 7 8 9 - 0 0 9 6 - W a s h i n g t o n , d . C. 2 0 0 0 1

Table of Authorities ....... .......................... ............... ...... hi

Interest of Amicus C u riae ........................... ........ ....... ......... 1

Introductory Statement............. 2

Summary of Argument........................................... ...... ._ 5

Argument ........ 7

I. FEDERAL CONTRACTORS ARE IMMUNE

FROM LIABILITY UNDER TITLE VII

WHEN THEY CREATE AFFIRMATIVE

ACTION PROGRAMS TO MEET THEIR

OBLIGATIONS UNDER EXECUTIVE OR

DER 11246 ................................................. 7

(1) Executive Order 11246_____ 7

(a) Congress knew that Executive Order

11246 expressly provided for the use of

quotas to ensure that blacks were not

excluded from jobs created by the ex

penditure of federal funds ______ ____ 8

(b) Congress did not regard the Executive

Order as conflicting with Title VII..... 12

(2) The standard of review for validating af

firmative action programs established by

government contractors to meet their obli

gations under Executive Order 11246 ......... 16

(a) Kaiser was justified in instituting a

race conscious affirmative action plan

under either the prima facie case

standard or the “ underutilization”

standard _______________ _____ _____ 18

(b) The two track seniority system used

at the Gramercy plant was the least

restrictive viable alternative ...... ........ 21

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

II

TABLE OF CONTENTS— Continued

Page

II. EXECUTIVE ORDER 11246 IS A VALID EX

ERCISE OF THE EXECUTIVE POWER

WHICH SERVES COMPELLING GOVERN

MENTAL INTERESTS ................... .................. 23

(a) Executive Order 11246 was issued pur

suant to statutory authority and has

the force and effect of law _____ ______ 23

(b) In authorizing racial quotas to increase

minority representation in the skilled

crafts, Executive Order 11246 serves a

compelling governmental interest and

does not violate the due process clause

of the Fifth Amendment...................... 25

Conclusion ...... ..... ............... ....... ................................... . 29

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Atkin V. Kansas, 191 U.S. 207 (1903) _____ ____ 26

Albemarle Payer Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405

(1975) ...................................... .................. ....... . 21

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 US 36

(1974) .......... ........ .......... .................................. . 4

Associated General Contractors of Massachusetts

V. Altshuler, 490 F.2d 9 (1st Cir. 1973), cert.

denied, 416 U.S. 957 (1974) ................... ............ 29

Berenyi v. District Director, Immigration and

Naturalization Service, 385 U.S. 630 (1967).... 4

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954) .............. . 25

Burrell v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Cory.,

Civ. Action 67-86 (M.D. La.) (consent decree

Feb. 24, 1975) ______ 2,28

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir. 1971)

on petition for rehearing en banc), cert, denied,

406 U.S. 950 (1972) .......... ...... ........ ............... . 22

Contractors Association of Eastern Pennsylvania

V. Secretary of Labor, 442 F.2d 159 (3rd Cir.

1971), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 854 (1971) .........7,23,29

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v.

American Telephone & Telegraph Co., 556 F.2d

167 (3rd Cir. 1977) .......... ....... ........ ................. . 8, 16

Ellis v. United States, 206 U.S. 246 (1907) ...... . ’ 26

Farkas V. Texas Instruments, Inc., 375 F.2d 629

(5th Cir. 1967), cert, denied, 389 U.S. 977

(1967) _____ ______________ ____________________ 23

Farmer v. Philadelphia Electric Co., 329 F.2d 3

(3rd Cir. 1964) __________ _____ ______ _____ 23

Green v. McDonnell Douglas Cory., 411 U S 792

(1973) .............................. .................................. 19

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971).... 21

In re Griffiths, 413 U.S. 717 (1973) ....................... 25

Lochner v. New York, 198 U.S. 45 (1905) _______ 26

Northeast Construction Co. v. Romney, 157 U.S.

App. D.C. 381, 485 F.2d 752 (1973) .............. . 24

Parson v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Cory., 575

F.2d 1374 (5th Cir. 1978) .................................2,21,28

IV

Perkins V. Lukens Steel Co., 310 U.S. 113 (1940).. 26

Regents of the University of California V. Bakke,

57 L. Ed.2d 750 (1978) ........... ....... .................. . 18,25

Rhode Island Chapter, Association of General Con

tractors v. Kreps, 450 F. Supp. 338 (D.R.I.

1978) ........................ ......................... ............... . 28

Rossetti Contracting Co. v. Brennan, 508 F.2d 1039

(7th Cir. 1974) ________ _____ ______ __________ 24

Stevenson V. International Paper Co., 516 F.2d 103

(5th Cir. 1975) .................. .................... .............. 17

Swint V. Pullman-Standard, 539 F.2d 77 (5th Cir.

1976) ............ ..... ................. .......... .... ............ .... 17

United States V. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries,

Inc., 517 F.2d 826 (5th Cir. 1975), cert, denied

sub nom. National Organization for Women, Inc.

V. United States and Harris v. Allegheny-Ludlum

Industries, Inc., 425 U.S. 944 (1976) ................. 28

United States V. Darby, 312 U.S. 100 (1941) ........ . 26

United States V. New Orleans Public Service, Inc.,

553 F.2d 459 (5th Cir. 1977)........ ....................... 23

Statutes and Regulations:

Executive Order 11246, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e (1970) ..passim

Executive Order 8802, June 25, 1941, 6 Fed.

Reg. 3109 (June 1941), U.S. Code Cong. Ser

vice 1941 .......... ....... .... ............... ....... ....... ......... 7

Executive Order 10925, 26 Fed. Reg. 1977, 3 C.F.R.

1959-63 Comp. 448 .............................. ......... ....... 7

Section 703(d) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-

2(d) (1970) __________________ _____________ 8

40 U.S.C. § 486(a) ........... ............... ......................... 24

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-2 et seq. (1970) ___________ _____ ____ passim

H.R. 1746, P.L. 92-261 _______ _________ _______ 8

41 C.F.R. 60 ............................ ......................... ....... 16, 17

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—-Continued

Page

V

Books and Articles: Page

I. Berlin, Slaves Without Masters: The Free

Negro in the A ntebellum South (Vintage

Ed. 1976) ______ 26

E. Genovese, Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World

the Slaves Made (1974) ......... ......... — ..... .— 26

R. Kruger, Simple Justice (Vintage Ed. 1977).... 26,27

R. Logan, The Betrayal of the Negro (Collier

Ed. 1965).......... 27

Comment, The Philadelphia Plan: A Study in the

Dynamics of Executive Power, 39 U. Chi. L.

Rev. 723 (1972) _________ ......7,14,25,27

Note, Developments in the Law— Employment Dis

crimination and Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 84 Harv. L. Rev. 1109 (1971) ...... 24, 26

Miscellaneous:

United States Bureau of the Census, Census of

Population: 1970, General Social and Economic

Characteristics, Louisiana...... ......... ............. -..... 20

Subcommittee on Labor of the Senate Committee

on Labor and Public Welfare, Legislative His

tory of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act

of 1972 ............... ....................... ...... ........... ......... passim

115 Cong. Rec. 40,018-40,019 (1971) ____________ 9

117 Cong. Rec. H. 8540 (daily ed. Sept. 16, 1971).. 12

118 Cong. Rec. S. 691 (daily ed. Jan. 28, 1972)..... 14

118 Cong. Rec. S. 2275 (daily ed. Feb. 27, 1972).... 14

H. Rep. 92-238, 92nd Cong. 1st Sess. 68 (1971)..... 9

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE *

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

was organized in 1963 at the request of the President of

the United States to involve private attorneys in the

national effort to assure civil rights to all Americans.

The Committee membership today includes two former

Attorneys General, ten past Presidents of the American

Bar Association, a number of law school deans, and many

of the nation’s leading lawyers. Through its national

office in Washington, D.C., and its offices in Jackson,

Mississippi, and eight other cities, the Lawyers’ Commit

tee over the past fifteen years has enlisted the services of

over a thousand members of the private bar in addressing

the legal problems of minorities and the poor in voting,

education, employment, housing, municipal services, the

administration of justice, and law enforcement.

Our extensive litigation program against employment

discrimination is conducted through our privately funded

Government Employment Project (providing representa

tion to federal, state, and local government employees

claiming unlawful employment discrimination), through

our Equal Opportunity Employment Project (which pro

vides representation to private-sector plaintiffs), and

through the general litigation activities of our Mississippi

and Washington offices and other local affiliates. In this

case, Kaiser and the USWA have sought through volun

tary action to come to terms with the gross underrepre

sentation of minorities in the skilled crafts in Kaiser’s

plants by providing for access to a newly created training

program by white and black workers on a one-for-one

basis. If the attack on this system is successful, we be

lieve, as Judge Wisdom said in his dissent, that the ulti

mate effect will be the end of voluntary compliance with

Title VII. 563 F.2d at 230.

* The parties’ letters of consent to the filing of this brief

being filed with the clerk pursuant to Sup. Ct. Rule 42(2).

are

2

We have previously addressed the issue of race-con

scious affirmative action programs, in the context of

higher education, in our amicus briefs filed in DeFunis v.

Odegaard, 416 U.S. 312 (1974), and Regents of the Uni

versity of California v. Bakke, 57 L,Ed.2d 750 (1978).

Because the issues presented by this case are vitally im

portant to the realization of the goal of equal employment

opportunity for blacks, the Committee files this brief urg

ing reversal of the judgment below.

INTRODUCTORY STATEMENT

The agreement reached by Kaiser and the United Steel

workers of America (USWA) in this case was taken as a

“ ‘remedial’ measure in response to pending litigation

concerning minority and female employment” 1 and in

response to threats by the Office of Federal Contract

Compliance (OFCC) concerning Kaiser’s affirmative ac

tion obligations. The agreement called for the establish

ment of training programs at Kaiser’s 15 plants to train

current employees for crafts positions. At the time the

agreement was consummated in 1974, Kaiser’s plant at

Gramercy, Louisiana was approximately 85% white and

14.8% black. Black representation in the crafts was only

2-2.5%. Because the area from which the work force was

hired was about 40% black in population, a goal of 39%

minority representation was established for each of the

crafts families.

1 The court of appeals’ statement that the collective bargaining

agreement was entered into to avoid future litigation, 563 F.2d at

218, is wrong. Supplemental Agreement to Collective Bargaining

Agreement, Art. IX ff 1 (Feb. 1, 1974). See Complaint If 5 and

Answers of Kaiser and USWA (f 5. At the time of the agreement,

Kaiser was defending Title VII litigation involving its two> other

plants in Louisiana located at Chalmette and Baton Rouge. Parson

V. Kaiser Alum. & Chem. Corp., 575 F.2d 1374 (5th Cir. 1978);

Burrell V. Kaiser Alum. & Chem. Corp., Civ. Action 67-86 (M.d '.

La.) (consent decree, Feb. 24, 1975).

3

Entrance into the training program depended almost

exclusively on seniority, but since there were far more

whites with greater seniority than blacks, without some

equalizing mechanism, few blacks if any would have

gained entrance into the program. Since this would have

defeated the whole purpose of the program, the parties

agreed in a Memorandum of Understanding that vacan

cies would be filled by selecting the white and black

applicants with the greatest seniority on a one-to-one

basis. The court of appeals held that this two-track sys

tem violates Title VII.

This Court’s decision in Bakke teaches that, in de

termining the validity of race-conscious affirmative action

programs, important distinctions must be drawn based on

the statutes involved and the context of the particular

case. The parties to this action disagree as to the scope

of the question presented. We suggest that the narrow

issue before the Court is whether Executive Order 11246

and its implementing regulations authorize government

contractors to implement race-conscious affirmative action

programs, involving quotas when necessary, to increase

minority representation in the skilled trades, and, if so,

whether the Executive Order conflicts with Title VII or

is otherwise invalid.

The nub of the court of appeals’ ruling is that, because

past discrimination at the Gramercy plant was not proven,

the “remedial” program devised by Kaiser and the USWA

became a “ racial preference” in violation of Title VII

which even a court could not have ordered. 563 F.2d at

224. This holding utterly ignores the most singular aspect

of this litigation— that none of the parties involved had

the slightest interest in establishing the existence of past

discrimination. It blinks reality to apply the same stand

ards applicable to other Title VII litigation to this set of

circumstances. The law must be flexible enough to devise

standards that are meaningful so as not to result in self

4

fulfilling prophesies concerning proof of issues concerning

which the parties lack adversity.2

The purpose of this brief is to suggest a framework for

analysis for determining the validity of racial quotas in

cases such as this. Whatever standard is adopted should

further the clear Congressional purpose of facilitating

voluntary compliance in assuring equality of employment

opportunity. Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 US

36, 44 (1974).

We propose the following standard: a race-conscious

affirmative action plan should be immunized by Executive

Order 11246 from violating Title VII if a government

contractor shows either (1) a reasonable belief that a

prima facie case of racial discrimination against blacks

can be established, or (2) a reasonable belief that part of

his work force underutilizes minorities and women and

that, unless corrective action is taken, he may be subject

to sanctions by the OFCC. If either of these is met, then

2 The only witnesses to testify at trial were two white workers and

two Kaiser officials. The USWA put on no witnesses. Considering

that neither party could benefit by a showing that past racial dis

crimination had occurred, it is remarkable that the record contains

as much information as it does. Amicus believes that the statistical

evidence before the Court in fact constitutes a prima facie case of

racial discrimination. On this record we believe it unnecessary for

the Court to determine the minimum threshhold of evidence required

to permit a federal contractor to implement an affirmative action

plan of the Kaiser design to claim the protection of Executive Order

11246.

We believe that the “ two-court” rule should not be applied in this

case because there was “obvious and exceptional” error in the lower

courts assessment of the facts concerning prior discrimination.

Berenyi v. District Director, Immigration and Naturalization Ser

vice, 385 U.S. 630, 635 (1967). This error is exemplified by the

court of appeals’ treatment of discrimination in the limited training

program in effect until 1974 as de minimis; in its failure to mention

the five years’ experience requirement previously used to hire crafts

men; and in its failure to consider 1970 census data showing that

blacks accounted for 21.3% of the craftsmen, foremen, and kindred

workers in the two parishes from which Kaiser drew its work force.

5

the contractor must show that the means chosen to in

crease the number of minorities in the work force is the

least onerous alternative available. If he meets this

burden, then the contractor is immune from liability

under Title VII.®

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I.

1. Executive Order 11246 exempts a government con

tractor from liability under Title VII when he imple

ments a race conscious affirmative action plan designed

to increase minority representation in the skilled crafts

which have historically excluded blacks. The Executive

Order permits the use of quotas and the legislative history

of the 1972 amendments to the Civil Rights Act of 1964

demonstrates conclusively that Congress was aware of,

and approved, the use of preferential treatment, including

quotas, under the Executive Order.

2. Past discrimination need not be shown in order for

a government contractor to qualify for the exemption. It 3

3 If a race-conscious affirmative action plan were attacked by a

white employee, at trial the contractor would establish his immunity

under Executive Order 11246 by proving the required elements as

described in the text. Once these elements were established, he

would be entitled to a dismissal of the complaint. He need not

establish a compelling need for the program, for as we argue, infra,

the Executive Order itself shows a compelling governmental inter

est in affirmative action by government contractors.

Since non-government contractors are not covered by Executive

Order 11246, their burden would be different. Obviously, the second

part of our suggested standard—underutilization of minorities—

would not apply: a non-government contractor is not aided by the

powerful government interests underlying the Executive Order that

all share equally in the jobs generated by the federal government’s

spending. As a defense to a Title VII suit, a non-government con

tractor must show some link to past discrimination in his plant to

justify an affirmative action plan. A reasonable belief that a prima

facie case of racial discrimination against blacks could be estab

lished should be sufficient.

6

is sufficient that he have a reasonable belief in the exist

ence of a prima facie case of racial discrimination or

that he is out of compliance with OFCC requirements

concerning minority representation, and that the means

chosen are the least restrictive alternative available. The

record in this case amply demonstrates that Kaiser’s pro

gram meets that standard.

II.

Because the Executive Order throws a mantle of pro

tection over government contractors in creating race

conscious affirmative action programs, it must be shown

to be a valid exercise of Executive authority, and, in

addition, to comply with equal protection principles of the

Fifth Amendment. We assume, arguendo, that the most

exacting judicial scrutiny is required. Executive Order

11246 and its predecessors have repeatedly been upheld

as a valid exercise of the Executive power and the 1972

amendments to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 show Con

gress’ express ratification of the federal contract com

pliance program including the use of quotas. The govern

mental interest that minorities not be excluded from jobs

created by federal expenditures is compelling and the

quota system used by Kaiser to admit blacks to the skilled

crafts is necessary to promote this interest.

7

ARGUMENT

I. FEDERAL CONTRACTORS ARE IMMUNE FROM

LIABILITY UNDER TITLE VII WHEN THEY CRE

ATE AFFIRMATIVE ACTION PROGRAMS TO

MEET THEIR OBLIGATIONS UNDER EXECUTIVE

ORDER 11246.

(1) Executive Order 11246.

In 1941, President Roosevelt, at the behest of civil

rights forces, issued the first in a series of Executive

Orders designed to put an end to employment discrimi

nation by government contractors. Executive Order 8802,

June 25, 1941, 6 Fed. Reg. 3109 (June 1941), U.S. Code

Cong. Service 1941, p. 860. For 20 years, a succession

of Executive Orders carried forward the policy of non

discrimination in government procurement and in the

defense industry.4 After 1943, the Executive Orders re

quired all government contracts to include a clause obli

gating employers not to discriminate on the basis of race,

color, creed, or national origin. Due to the ineffective

ness of this approach, in 1961 President Kennedy ex

tended this requirement to include affirmative action.

Executive Order 10925, 26 Fed. Reg. 1977, 3 C.F.R.

1959-63 Comp. 448. The obligations of governmental

contractors are currently set forth in Executive Order

11246.5 The Executive Order has been upheld as a “valid

4 The successive Executive Orders are described in Contractors

Ass’n of Eastern Pa. v. Secretary of Labor, 442 F.2d 159, 168-70

(3rd Cir. 1971), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 854 (1971). See also, Com

ment, The Philadelphia Plan: A Study in the Dynamics of Executive

Power, 39 U.Chi.L.Rev. 723, 725 n.25 (1972).

5 Executive Order 11246 provides, in pertinent part:

The contractor will not discriminate against any employee or

applicant for employment because of race, color, religion, sex

or national origin. The contractor will take affirmative action to

ensure that applicants are employed, and that employees are

treated during employment, without regard to their race, color,

religion, sex or national origin. §202(1).

8

effort by the government to assure utilization of all seg

ments of society in the available labor pool for government

contractors, entirely apart from Title VII.” Equal Em

ployment Opportunity Commission v. American Telephone

& Telegraph Co., 556 F.2d 167, 175 (3rd Cir. 1977).

Without any consideration of the legislative history,

the court of appeals in this case held that Executive Order

11246, insofar as it mandates racial quotas for admission

to on-the-job training programs, cannot be harmonized

with § 703(d) of Title VII and is therefore invalid. An

examination of the legislative history of the 1972 amend

ments to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 demonstrates that

the Congress (1) knew that the Executive Order man

dated the use of quotas, and (2) did not regard the Exec

utive Order as being in conflict with the terms of Title

VII.

(a) Congress knew that Executive Order 11246

expressly provided for the use of quotas to

ensure that blacks were not excluded from jobs

created by the expenditure of federal funds.

It is clear from the legislative history of the 1972

amendments that Congress was fully aware that quotas—

in the strict sense of the word— were mandated by the

Executive Order. One of the major procedural questions

which the Congress addressed was whether to transfer

all the authority, functions, and responsibilities of the

Secretary of Labor pursuant to the Executive Order re

lating to contract compliance to the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission. Section 717(f) of H.R. 1746,

P.L. 92-261. A major issue that emerged in the debates

was whether, if the amendment were approved, Title VII

would prohibit affirmative action, including the use of

racial quotas, which was authorized by the Executive

Order. Much of the discussion in the debates focused on

the Philadelphia plan, whereby the OFCC had imposed

affirmative action requirements utilizing goals for hiring

9

minorities as a precondition for federal assistance for

certain construction projects.’6

In opposing the transfer of the OFCC’s functions to the

EEOC, Rep. Green expressed her concern that, if the

transfer occurred, the EEOC might decide that it had

authority to impose racial quotas, which it was forbidden

to do by Title VII. Her understanding of Title VII was

that “ [ujnder Title VII, (Sec. 703 ( j ) ) EEOC is expressly

prohibited from imposing racial quota requirements. Un

der the Executive Order, there is authority to require an

affirmative action plan including the imposition of racial

quotas.” She regarded “the Philadelphia Plan [as] such

a quota plan.” H. Rep. 92-238, 92nd Cong. 1st Sess. 68

(1971) (Separate views of Rep. Green of Oregon).7

To ensure that the EEOC would not misinterpret the

extent of its authority in the event that the federal con

tract compliance program was transferred to its juris

diction, Rep. Dent introduced an amendment that defined

6 In 1969, a preliminary skirmish had been fought over the quota

issue. _ The Comptroller General objected to the Philadelphia plan as

violating Title VII because it approved quotas. He refused to ap

prove expenditures for projects approved under it. The Attorney

General issued a contrary opinion and directed the Secretary of

Labor to administer the plan. The Comptroller General then sought

to have a rider attached to a pending appropriations bill to limit

“ the use of funds to finance any contract requiring a contractor or

subcontractor to meet, or to make every effort to meet, specified

goals of minority group employees.” 115 Cong. Rec. 40,018 - 40,019

(1971). The rider, known as the Fannin rider, was defeated. The

episode is described in 39 U.Chi.L.Rev., supra, at 747-50. As the

comment points out, because the measure was a rider attached to an

appropriations bill, it would be overstating the case to regard this

as ratification by Congress of the Philadelphia Plan. No such

ambiguity attends the debates on the 1972 Amendments.

7 Reprinted in Subcommittee on Labor of the Senate Committee on

Labor and Public Welfare, Legislative History of the Equal Em

ployment Opportunity Act of 1972 (hereafter Legislative History),

at 128. Rep. Green had submitted an amendment in committee which

would have made Title VII take precedence in case of conflict. That

amendment had been rejected.

10

the EEOC’s powers in enforcing the Executive Order.

His amendment would have prohibited the Commission

from imposing or requiring quotas or preferential treat

ment in the administration of the federal contract com

pliance program.8 Legislative History 190. He explained

that:

Such a prohibition against the imposition of quotas

or preferential treatment already applies to actions

brought under Title VII. My amendment would, for

the first time, apply these restrictions to the Federal

contract-compliance program.

Legislative History 190.

Rep. Quie, in discussing the transfer of power to the

EEOC, emphasized that “ the OFCC does not operate un

der the provisions of the Civil Rights Act and its pro

cedures and sanctions are completely different from those

of the Act, . . .” Legislative History 202. He anticipated

great difficulties arising “ from the fact that the OFCC

has imposed requirements on Federal Government con

tractors which it is questionable may be imposed under

the statute.” Id.

Rep. Green stated that Title VII “had always pro

hibited the establishment of quotas” , Legislative History

209, but that ’ ’Executive Order 11246 under which the

Philadelphia Plan was put into effect, in my judgment

clearly did establish quotas.” Legislative History 210.

She then stated that it would be impossible for her to

support the committee bill without some amendments,

including a “ Congressional prohibition against establish

8 The amendment read:

The Commission shall be prohibited from imposing or requir

ing a quote [sic] or preferential treatment with respect to

numbers of employees, or percentages of employees of any

race, color, religion, sex or national origin. Legislative History

189.

11

ing any quota system— a prohibition against preferential

treatment for some at the expense of others, a prohibition

against ‘reverse discrimination’, if you will.” Ibid. After

describing how the OFCC had, in a highhanded manner,

imposed quotas in a plant in Portland, she then stated

that the purpose of the amendment was

to give this House the right to decide whether or not

we want to amend the Civil Rights Act and to say

whether we are going to establish quotas by law.

H.R. 1746, the committee bill, on page 29, freezes

Executive Order 11246 into the law. If this were

passed without amendment, we would be giving our

approval to the quota system.

Legislative History 210, 211.

In an exchange between Rep. Pucinski and Rep. Dent,

the latter made clear that in his mind there was no dis

tinction between the word “goal” and the word “quota”

and that under his amendment any preferential treatment,

including quotas, would be forbidden:

Mr. Pucinski. And, this amendment would bring

Title VII into this Commission’s activities? In other

words, if this amendment is adopted, the Commission

cannot claim it as exempt from Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act nor can the Commission require

quotas or goals in assigning job distribution?

Mr. Dent. Right; it cannot require quotas.

Legislative History 235.

As a final example, Rep. Steiger stated that he was

“ absolutely appalled” at the Dent amendment, “which is

aimed at subverting the Philadelphia plan and the Office

of Federal Contract Compliance’s effort to carry forward

an affirmative action program.” Legislative History 222.

He went on to say, with particular relevance for this case:

12

I think an effort has been made to end the other

program [i.e., the federal contract compliance pro

gram] designed to ensure an increase in the abiilty

of the minority people to gain some place in those

trades in which the salaries are high and in which

they have a certain opportunity to be skilled crafts

men in the society. Ibid. (Brackets and emphasis

added.)

The Dent amendment was defeated. 117 Cong. Rec.

H. 8540 (daily ed. Sept. 16, 1971).

This is but a small sampling of statements made during

the debate in the House and Senate demonstrating that

Congress understood that the Executive Order authorized

affirmative action, including quotas, and that Title VII

did not in the absence of prior discrimination.9

(b) Congress did not regard the Executive Order

as conflicting with Title VII.

The Senate was also fully informed as to the remedial

differences between Executive Order 11246 and Title VII.

Sen. Javits explained how the OFCC had interpreted the

concept of affirmative action “as something more than

just the duty not to engage in active discrimination in

hiring.” Legislative History 648.

Under this concept of affirmative action OFCC has

been able to promulgate plans, such as the Phila

delphia plan, and numerous similar plans in other

cities throughout the country, under which contrac

9 The relevant debates in the House appear in Legislative History,

pp. 128, 209-211, 260-261, 287 (remarks of Rep. Green) ; 190, 255,

234-235 (remarks of Rep. Dent) ; 202 (remarks of Rep. Quie); 208-

209, 230-231, 283-34 (remarks of Rep. Erlenborn) ; 208-209 (re

marks of Rep. Hawkins); 222, 224 (remarks of Rep. Steiger); 234-

235 (remarks of Rep. Pucinski); and 259 (remarks of Rep. Gerald

R. Ford).

In the Senate, the relevant debate is found at: 515 (remarks of

Sen. Allen) ; 648-649, 1046-1048 (remarks of Sen. Javits) ; 915-917

(remarks of Sen. Saxbe); 921 (remarks of Sen. Williams) ; and

1042-1045, 1101, 1714-1717 (remarks of Sen. Ervin).

13

tors agree to undertake good faith efforts to increase

the utilization of minority group employees and wom

en without reference to whether they are actually

guilty of illegal discrimination. Ibid, (emphasis

added)

He went on to point out that Title VII “ is strictly a non

discrimination law. Affirmative action may be ordered,

but only as a remedy in a case of proven discrimination.”

Legislative History 649. He continued that, if OFCC’s

powers were transferred to the EEOC, “ [t]he result might

be confusion in the agency and confusion in the minds of

Federal contractors in dealing with the agency, or a

watering down of the Executive Order program so that

it and the Title VII program become indistinguishable.”

Id.

Sen. Saxbe gave emphasis to the point:

The Executive Order program should not be con

fused with the judicial remedies for proven discrimi

nation which unfold on a limited and expensive case-

by-case basis. Rather, affirmative action means that

all Government contractors must develop programs

to insure that all share equally in the jobs generated

by the Federal Government’s spending. Proof of

overt discrimination is not required, (emphasis

added)

Legislative History 915. In opposing the transfer of func

tions to the EEOC, Sen. Saxbe stated: “ The affirmative

action concept as innovatively and successfully employed

by the OFCC has been challenged as a violation of Title

VII— the courts have responded by stating that the Exec

utive Order program is independent of Title VII and not

subject to some of its more restrictive provisions.” Id.

916. He foresaw that placing the Executive Order pro

gram under Title VII would give rise to renewed chal

lenges. Id. 917.

The failure of the effort to merge the OFCC program

into the EEOC was the prelude to a major battle in the

14

Senate— orchestrated by Senator Ervin—to subject the

Executive Order to Title VII’s anti-discrimination pro

visions and annihilate the affirmative action program. The

conflict has been described in Comment, The Philadelphia

Plan: A Study in the Dynamics of Executive Power, 39

U.Chi.L.Rev., supra, at 754-757, and will not be repeated

in depth here.

Briefly, an amendment offered by Sen. Ervin would

have provided that: “No department, agency or officer of

the United States shall require an employer to practice

discrimination in reverse by employing persons of a

particular race, or a particular religion, or a particular

national origin, or a particular sex in either fixed or vari

able numbers, proportions, percentages, quotas, goals or

ranges.” 118 Cong. Rec. S. 691 (daily ed. Jan. 28, 1972).

This amendment was decisively rejected. Because, in

addition to attacking the Philadelphia Plan, the amend

ment could be read to deprive even courts of power to

remedy proven cases of discrimination by quota relief,

its defeat arguably is not a clear-cut statement of support

for the Executive Order affirmative action program. Any

uncertainty on this score was soon resolved.

Sen. Ervin introduced another amendment which would

have amended § 703 (j ) of Title VII to proscribe com

pletely the OFCC’s affirmative action program.1'15 This 10

10 The amendment provided:

Nothing contained in this title or in Executive Order No. 11246,

or in any other law or Executive Order, shall be interpreted to

require any employer, employment agency, labor organization,

or joint labor-management committee subject to this title or to

any other law or Executive Order to grant preferential treat

ment to any individual or to any group because of the race,

color, religion, sex, or national origin of such individual or

group on account of an imbalance which may exist with respect

to the total number or percentage of persons of any race, color,

religion, sex or national origin employed by any employer, re

ferred or classified for employment by any employment agency

or labor organization, admitted to membership or classified

by any labor organization, or admitted to, or employed in, any

15

was to be accomplished by extending § 703 (j) to cover

explicit remedies devised under the Executive Order Pro

gram. In describing the amendment, Sen. Ervin said:

Anyone who is desirous of understanding this amend

ment can read the amendment in the light of sub

section (j) of § 703 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

and understand what it would do. It is designed to

make the prohibition upon preferential treatment

created by this subsection of the original act ap

plicable not only to the EEOC, but also to the Office

of Contract Compliance and to every other executive

department or agency engaged, either under the

statute or under any Presidential directive, in en

forcing the so-called equal employment opportunity

statute.

Legislative History 1714. Sen. Javits responded by saying

that it would make plans like the Philadelphia Plan un

lawful and by including the Executive Order, preclude the

federal government as an employer from putting such a

plan into effect. Legislative History 1715. The amend

ment was decisively defeated. Legislative History 1716-17.

The rejection of this amendment conclusively demon

strates (1) that the affirmative action provisions of the

Executive Order are neither governed by nor in conflict

with § 703(j) of Title VII and 11 (2) that programs of

preferential treatment, including quotas, are a permiss

ible means of enforcing the Executive Order.

apprenticeship or other training program, in comparison

with the total or percentage of persons of such race, color,

religion, sex, or national origin in any community, State, sec

tion, or other area, or in the available work force in any com

munity, State, section, or other area.

118 Cong. Rec. S. 2275 (daily ed., Feb. 27, 1972).

11 The court of appeals held that the Executive Order conflicts

with § 703(d) of the Civil Rights Act relating tô admissions to on-

the-job training. 563 F.2d at 227. There is absolutely nothing in the

legislative history that suggests Congress intended to ratify the

authority of the OFCC to implement affirmative action plans to the

exclusion of on-the-job training programs.

(2) The Standard of Review for validating affirmative

action programs established by government con

tractors to meet their obligations under Executive

Order 11246.

While Executive Order 11246 exempts race-conscious

affirmative action plans created to satisfy OFCC require

ments, that does not mean that employers are without

any constraints whatsoever in setting up such a plan.

What is required is a standard that makes sense in the

special context of the Executive Order.12

We believe that a government contractor who can

demonstrate either a reasonable belief that a prima facie

case of discrimination against blacks could be made out

against him or that he might incur sanctions from the

OFCC because of low utilization of minorities in his work

force (or skilled crafts as here) should be able to create

a race conscious AAP if he demonstrates that the particu

lar plan adopted is necessary under the circumstances.

This standard satisfies the policies underlying the Execu

tive Order and protects the rights of white workers by

requiring that the plan be carefully tailored.

Executive Order 11246 does not require proof of overt

past discrimination to justify an affirmative action pro

gram— rather, it looks at the composition of the employ

er’s work force. See Legislative History 648 (Remarks

of Sen. Javits); 915 (remarks of Sen. Saxbe); 921 (re

marks of Sen. Williams). Cf. E.E.O.C. v. A.T.&T., supra

(consent decree denying violations). Under 41 C.F.R.

60-2.11, non-exempt employers must undertake a utiliza

tion analysis which must be filed with the OFCC.13 A

12 Judge Wisdom suggests in his dissent that, if an affirmative

action program adopted in a collective bargaining agreement is a

reasonable remedy for an arguable violation of Title VII, it should

be upheld. 563 F.2d at 230.

13 “ ‘Under-utilization’ is defined as having fewer minorities or

women in a particular job group than would reasonably be expected

by their avialability.” 41 C.F.R. 60-2.11(b). Factors to be con

sidered are:

16

[Footnote continued on page 17]

17

federal contractor who implements an affirmative action

plan because minorities are under-utilized is motivated

by the desire to protect all its employees against loss of

jobs. If the company is “ debarred” or incurs other sanc

tions, all employees, white and black, suffer. (Tr. 130).

A reasonable program designed to prevent this from

happening should be upheld.

Alternatively, as Judge Wisdom pointed out, an em

ployer should not have to wait to be sued by black em

ployees before taking affirmative action. If he has a

reasonable belief that a prima facie case of liability could

be established, this, too, should justify the creation of a

reasonable program.14

In either case, the utilization analysis should provide

the basis for determining whether the employer could

form such a reasonable belief. * 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

13 [Continued]

(1) The minority population of the labor area surrounding the

facility;

(2) The size of the minority unemployment force in the labor

area surrounding the facility;

(3) The percentage of the minority work force as compared

with the total work force in the immediate labor area;

(4) The general availability of minorities having requisite

skills in the immediate labor area;

(5) The availability of minorities having requisite skills in an

area in which the contractor can reasonably recruit;

(6) The availability of promotable and transferable minorities

within the contractor’s organization;

(7) The existence of training institutions capable of training

persons in the requisite skills;

(8) The degree of training which the contractor is reasonably

able to undertake as a means of making all job classes

available to minorities.

14 Of course, the existence of an OFCC agreement does not provide

a company with a defense to a Title VII action which demonstrates

that the AAP is ineffective and fails to eliminate present effects of

past discrimination. Swint v. Pullman-Standard, 539 F.2d 77, 95

n.44 (5th Cir. 1976); Stevenson v. International Paver Co 516

F.2d 103, 106 (5th Cir. 1975).

18

It is also appropriate, in the ease of a government con

tractor, to impose a requirement that he demonstrate

that his plan is necessary to the accomplishment of a

legitimate and substantial governmental interest.5 * * * * * * * * * 15

(a) Kaiser was justified in instituting a race con

scious affirmative action plan under either the

prima facie case standard or the “underutiliza

tion” standard.

The record amply demonstrates that Kaiser agreed to

the training program and the two-track seniority system

at least in part to comply with threats by the OFCC

conditioning federal contracts on appropriate affirmative

action. 563 F.2d at 218. This in itself should justify the

creation of an affirmative action plan to train minorities

in the skilled crafts.

Furthermore, evidence introduced at trial and which is

available as a matter of public record demonstrate that

Kaisei could reasonably have believed that a prima facie

case of past racial discrimination could have been

established.

First, statistical evidence demonstrated a primai facie

case of discrimination against blacks in hiring for un

5 the Executive Order exempts race conscious affirmative action

plans from the operation of Title VII, the constitutionality of the

Executive Order itself is called into question. In Balcke, Justices

Brennan, Marshall, White and Blackmun held that racial classifica

tion designed to further remedial purposes “must serve important

governmental objectives and must be substantially related to achieve

ment of those objectives,” 57 L. Ed. 2d at 814. Mr. Justice Powell

held that a rape conscious program must be subjected to the most

exacting scrutiny under the Constitution. Since we believe that race

conscious programs under the Executive Order serve a compelling

governmental interest and that the particular plan used by Kaiser is

the least restrictive alternative under the circumstances, we analyze

the issue using the more rigorous standard of review. If Kaiser’s

program meets the standard applied to “suspect” classifications a

fortiori it would meet the “substantial relationship” test.

In Section II we take up the questions of whether the Executive

Order is constitutional and whether affirmative action using quotas

serves a compelling governmental interest.

19

skilled jobs. The production force in 1974 was only

14.8% black as compared with the area work force of

39% black. Tr. 94-95. Even this figure was up sharply

from 1969 when Kaiser began hiring on a one-to-one

black-white ratio under pressure from the OFCC. From

1958 to 1969, Kaiser hired off the street on a “ best quali

fied” basis. The disproportionately low number of blacks

hired could have been the result of using “non-validated”

tests or improperly subjective processes. Discrimination

in these hires could naturally affect the ability of blacks

to enter the training program instituted in 1974 because

fewer blacks would have the necessary seniority to make

them competitive with whites. 563 F.2d at 231.

Secondly, until 1974, Kaiser had a limited training pro

gram for two crafts: carpenter-painter and general re

pairman. (Tr. 101-102). Eligibility for these programs

required experience as well as seniority. (Tr. 110) Out

of 28 trainees in the two programs only two were black.

Thus, with two exceptions, the prior experience require

ment kept blacks out of the training program. (Tr. 135)

Nothing in the record suggests that Kaiser attempted to

recruit blacks for the training program. Its post-1970

recruiting of blacks—the only recruiting it ever under

took— extended only to blacks who were fully qualified

craftsmen. (Tr. 99)

The court of appeals seems to acknowledge that, but

for the small numbers involved, a prima facie case of

discrimination was made out. The court concluded that,

in view of the limited scope of the program, the prior

experience requirement could not be regarded as an un

lawful employment practice. 563 F.2d at 224 n.13.

However, the size of the program does not immunize it.

Green v. McDonnell Douglas Corp., 411 U.S. 792 (1973).

Indeed, in this very case the majority found Title VII

violated because it gave preference to seven blacks.

Thirdly, Kaiser required five years’ (subsequently re

duced to three) experience to be hired into the “ journey

man top paying standard rate craftsman classification”

(Tr. 111). Prior to 1974, only five blacks were in all

the crafts combined; two of the blacks had gone through

the limited training program (Tr. 112). Until 1974, the

company was unable to hire a black journeyman off the

street (Tr. 112). There was no showing that the experi

ence requirement was necessary and, indeed, the fact that

it was shortened from five to three years suggests that it

was not.

Fourth, Kaiser maintained that the reason more black

craftsmen were not hired prior to 1974 (there were five

out of 290 craft workers at the Gramercy plant) was due

to the lack of black craftsmen in the area. Kaiser’s in

dustrial relations expert testified at trial that the great

majority of all employees at the plant were hired from

St. James and St. John the Baptist parishes. 415 F. Supp.

at 764. And it was the population of these two parishes

that was used to establish the goal of 39% minority for

each of the craft families at the Gramercy plant. (Tr.

95).

Census figures show that in 1970, 432 of 2,029 or

21.3% of workers in those two parishes classified as

Craftsmen, Foremen, and Kindred Workers, were black.16

“ OCCUPATION OF EMPLOYED PERSONS

16 Years of Age and Over

1970

Craftsmen, Foremen,

20

and Kindred Workers Total Black Black %

Louisiana: 167,860 25,901 15.4%

New Orleans SMS A : 49,641 8,897 17.9%

Baton Rouge SMSA: 15,884 2,703 17.0%

St. James Parish: 783 179 22.9%

St. James and St. John the Baptist: 2,029 432 21.3%

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, Census of Population: 1970

General Social and Economic Characteristics, Louisiana.

State data: Table 54

SMS A data: Table 86 (totals)

Table 93 (blacks)

Parish data: Table 122 (totals)

Table 127 (blacks)

21

The black craft population at Gramercy was only 2-2.5%

in 1974. 415 F. Supp. at 764.

Fifth, assuming the alleged lack of available black

craftsmen was caused by discrimination by craft unions,

and, as Kaiser claims, not by its own hiring policies,17 the

company’s failure to institute a large-scale training pro

gram to reduce its dependency on so discriminatory a

source of craftsmen, is itself a prima facie violation of

Title VII. Because the requirement of prior experience

tended to exclude blacks at such a high rate, it was un

lawful unless justified by “business necessity” . Griggs v.

Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971); Albemarle Paper

Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 425-26 (1975). No such

justification has been offered.

Finally, the two documents lodged with the clerk by the

United States in this case demonstrate (1) that craft

employment practices at the Gramercy plant were out of

compliance with OFCC anti-discrimination requirements

(1971 Compliance Report) and (2) that prior experience

requirements for transfer to maintenance crafts were not

validated and had been waived for whites but not for

blacks.

(b) The two-track seniority system used at the

Gramercy plant was the least restrictive viable

alternative.

The problem confronted by Kaiser and the USWA was

that as of 1974, of the 290 craftsmen at the Gramercy

plant, only five, or approximately 2%, were black. The

17 But see Parson v. Kaiser Alum. & Chem. Corp., supra, 575 F.2d

at 1381-1382, 1389-1390. In a footnote, the court distinguished the

Weber case with the statement that “ Kaiser went too far . . . by

imposing a hiring quota of a minimum number of blacks in a plant

where no prior discrimination could be shown.” 575 F.2d at 1374

n.35 (emphasis added). As discussed above, we consider it dis

ingenuous to equate what the parties to that lawsuit were interested

in showing and what might have been shown if their interests had

been truly adverse on that particular issue.

22

two-track system based on seniority was not only reason

able under the circumstances, but was necessary if blacks

were to have any real chance of being able to participate

in the training program.

First, it cannot be argued in the present context that

application of a quota in any way interferes with merit-

based hiring. All the applicants were equally well quali

fied to participate in the training program. For all in

tents and purposes, the only measure of selection was

seniority. (Tr. 105, 114)

Second, a Kaiser official testified that in the absence

of a race conscious program “very few blacks . . . would

get into any of the crafts for quite a while.” (Tr. 113).

Third, unlike the situation in higher education, this

would be an inappropriate situation to consider race as

one of several relevant factors. Unlike a university, an

industrial employer has no justifiable interest in a diverse

work force. Selection for crafts training has traditionally

been based on seniority under collective bargaining agree

ments.

Fourth, in view of the fact that Kaiser claims that it

had exhausted the supply of skilled blacks in the area,

the only way to increase minority representation in the

crafts families was through the implementation of a train

ing program.

Fifth, the system aided both whites and blacks because

both groups had an opportunity to enter the crafts which

they did not have previously.

Sixth, the quota agreed upon was not an absolute quota

in the sense that it reserved all the spaces in the training

program for blacks. See Carter V. Gallagher, 452 F.2d

315, 327 (8th Cir. 1971) (on petition for rehearing en

banc), cert, denied, 406 U.S. 950 (1972).

23

Seventh, a lesser ratio such as 1 black to 2 whites would

not have been effective. Even using the 1-1 hire ratio, it

was estimated by a Kaiser official that it would take a

minimum of 10 years to achieve the 39% figure and

possibly never, depending upon Kaiser’s needs and turn

over. (Tr. 108-109).

Eighth, using a random sampling, given the racial com

position of the labor force, would have produced few, if

any, blacks.

Ninth, the 1-1 ratio was temporary. Under the agree

ment it was understood that once the goal of 39% was

achieved, Kaiser would revert to the ratio needed to keep

minority representation equal to the representation in the

community work force population. (Tr. 109-110).

Given the particular facts of this case, the 50-50 hiring

ratio for acceptance into the training program was the

least restrictive viable alternative.

II. EXECUTIVE ORDER 11246 IS A VALID EXERCISE

OF THE EXECUTIVE POWER WHICH SERVES

COMPELLING GOVERNMENTAL INTERESTS.

(a) Executive Order 11246 was issued pursuant to

statutory authority and has the force and

effect of law.

The authority of the President to issue Executive Order

11246 and its predecessors has repeatedly been upheld.

United States v. New Orleans Public Service, Inc., 553

F.2d 459 (5th Cir. 1977) (NOPSI) ; Contractors Ass’n

of Eastern Pennsylvania v. Secretary of Labor, supra;

Farkas v. Texas Instruments, Inc., 375 F.2d 629 (5th

Cir. 1967), cert, denied, 389 U.S. 977 (1967) (Exec.

Order 10925); Farmer v. Philadelphia Electric Co., 329

F.2d 3 (3rd Cir. 1964) (Exec. Order 10925 and prior

orders). The authorization has variously been, found in

Art. II of the Constitution, which commands the President

24

to “ take care that the laws be faithfully executed” , the

due process clause of the Fifth Amendment, explicit Con

gressional authorization in 40 U.S.C. § 486(a), and im

plied Congressional ratification in Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 and the debates surrounding the 1972

amendments. Note, Developments in the Law— Employ

ment Discrimination and Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 84 Harv.L.Rev. 1109, 1275-80 (1971);

United States v. New Orleans Public Service, Inc., supra.

In NOPSI, supra, the court isolated three sources of

legislative authority for Executive Order 11246: the

President’s express statutory authority concerning federal

procurement; the Civil Rights Act of 1964; and the de

bates over the 1972 amendments.

40 U.S.C. § 486(a) authorizes the President to issue

orders to implement the Federal Property and Adminis

trative Services Act of 1949. The procurement power may

be used by the President and Congress to achieve social

and economic objectives. Rossetti Contracting Co. v.

Brennan, 508 F.2d 1039, 1045 n.18 (7th Cir. 1974) ;

Northeast Construction Co. v. Romney, 157 U.S. App.

D.C. 381, 485 F.2d 752, 760 (1973). As the Court said

in NOPSI, supra, “ Those cases stand for the proposition

that equal employment goals themselves, reflecting impor

tant national policies, validate the use of the procure

ment power in the context of the Order.” 553 F 2d at

467.

Moreover, Congress has ratified the Executive Order

program, including the use of quotas, to implement the

affirmative action aspect. What was implicit in 1964

when Congress indicated that Title VII would not be the

exclusive remedy for employment discrimination and per

mitted the Executive Order program to continue, was

made explicit in 1972 when it turned back attempts to

consolidate the OFCC with the EEOC and eliminate the

use of quotas as a tool for achieving affirmative action

25

on the part of government contractors. NOPSI, supra,

553 F.2d at 467. Congress’ action compels the conclusion

that it intended the Executive Order program to continue

and that it was concerned that the OFCC should continue

to be the instrument for carrying out the Executive policy.

Whatever doubts that may have existed concerning the

validity of the Executive Power to implement the pro

gram were cured by Congress’ action in 1972. 39 U.Chi.

L.Rev., supra, at 723.

(b) In authorizing racial quotas to increase minor

ity representation in the skilled crafts, Execu

tive Order 11246 serves a compelling govern

mental interest and does not violate the due

process clause of the Fifth Amendment.

Recognition of the fact that Executive Order 11246

permits Kaiser to use a racial quota to increase minority

representation in the skilled crafts gives rise to the ques

tion of whether the Executive Order itself violates equal

protection principles contained in the Fifth Amendment.

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954). We assume that

because Kaiser’s two-track seniority system uses race as

a factor, the governmental purpose must be both legiti

mate and substantial and that the program’s racial classi

fication must be necessary to promote this interest.

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 57 L.

Ed.2d at 781, 786 (Powell, J . ) ; In re Griffiths, 413 U.S.

717 (1973).

During the Congressional debates on the 1972 amend

ments to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Rep. Mink de

scribed the purpose of the Contract Compliance Program

in the following terms:

Government contractors are among the largest and

most influential in the Nation and the policies and

practices which they adopt have a significant impact

on the rest of the business community. Through the

Government-wide contract compliance program, the

OFCC seeks to prevent any indirect Federal sub-

26

sidization of employment discrimination and to guar

antee that the Government’s tremendous purchasing

power operates as a force for social improvement.

Legislative History 298. Plainly, the government’s in

terest in seeing that minorities are not excluded from em

ployment opportunities which are generated by the ex

penditure of vast amounts of federal funds is sub

stantial.18 This is particularly true in this case which

concerns the exclusion of blacks from the skilled trades.

It is well-documented that the absence of blacks from the

crafts nationwide was caused by blatant racial discrimi

nation.

Kaiser’s program was designed to address a particular

problem: the absence of blacks from the craft families

in its plants. The problem is a pervasive one in American

industry and has its roots in history. Even before the

Civil War, skilled black workers were regarded as rivals

by white working men in both the North and the South.

R. Kruger, SIMPLE JUSTICE, 52 (Vintage ed. 1977).19

18 Furthermore, the government is at the height of its power in

requiring companies it does business with to help advance societal

goals: the government has the unrestricted power to decide with

whom it will deal and the terms and conditions of the agreement.

NOPSI, supra, 553 F.2d at 469. See also, Atkin v. Kansas, 191 U.S.

207 (1903); Lochner v. New York, 198 U.S. 45, 55, 64 (1905); Ellis

V. United States, 206 U.S. 246, 256 (1907) ; Perkins v. Lukens Steel

Co., 310 U.S. 113, 127-129 (1940); United States V. Darby, 312

U.S. 100, 115-116 (1941). While there are alternatives to Executive

Order 11246 by which the Executive Branch may influence policy

involving the expenditure of federal funds, each has significant

limitations. 84 Harv.L.Rev., supra, at 1276-1277.

19 Before the Civil War, there were numerous black craftsmen.

Masters often hired out their slave craftsmen to others. E. Geno

vese, Roll, Jordan, Roll : The W orld the Slaves Made, 391

(1974). White craftsmen were hostile to free black craftsmen and

attempted to drive them out of the professions. I. Berlin, Slaves

Without Masters : T he Free Negro in the A ntebellum South,

229-232 (Vintage ed, 1976); E. Genovese, Roll, Jordan, Roll,

op. cit. supra, at 389 and sources cited in n.3. 41 C.F.R. 60-2.11

states that skilled crafts is one category in which minorities are

likely to be underutilized.

27

After the war, tensions between workers of different

races mounted. Northern workers resented blacks as com

petitors in the labor market and a depressant on wage

levels: white Southern craftsmen feared competition from

blacks who had been trained as slaves to be blacksmiths,

bricklayers, or cabinet makers. Id. 52. Blacks were ex

cluded from membership in the unions, beginning a pat

tern of hostility which was to last a hundred years. See

R. Logan, THE BETRAYAL OF THE NEGRO, 147-162

(Collier ed. 1965). By World War II, “ the most unre

lenting practitioners of [racial] bias were the independ

ent craft unions and affiliates of the American Federation

of Labor, whose long standing antipathy to blacks never

died.” R. Kruger, SIMPLE JUSTICE at 228. A Kaiser

official in this case testified that the lack of black skilled

workers was “ a direct result of employment discrimi

nation over the years.” (Tr. 142).

Discrimination against blacks in the trades was well

entrenched by 1941 when, reacting to the threat of black

leaders to commence massive demonstrations, President

Roosevelt promulgated Executive Order No. 8802. 39

U. Chi. L. Rev., supra, at 725. The Executive Order,

and those which followed, sought to ensure that jobs

which were generated through expenditures of federal

money would not be denied to some because of their race.

The court of appeals held that proof of past discrimi

nation at the Gramercy plant was an essential precon

dition to upholding the validity of Kaiser’s affirmative

action program. 563 F.2d at 224. But judicial-type

findings of fact of past discrimination are not required

under Executive Order 11246.20 As Sen. Williams, who

20 Or, it appears, under the Constitution. In Bakke, this Court

held that a race conscious affirmative action program would be valid

if it meets exacting scrutiny under the equal protection clause of the

fourteenth amendment. There was no evidence that the University

of California medical school at Davis had ever practiced racial

discrimination.

28

supported transferring the functions of the OFCC to the

EEOC, said:

The key to the Office of Federal Contract Com

pliance’s approach is affirmative action. It is not a

situation, although it could well be called one, of cor

recting persisting discrimination in its most well

understood form. It involves an effort regardless of

the past history of the employer to upgrade and im

prove its minority work force. In the affirmative

action program, the concept of improving the quality

of minority employment is commendable. It is neces

sary, and it is urgent. In the Department of Labor

it has not worked well and should be transferred.

The contract compliance program is necessary and

important.

Legislative History 921. See also Legislative History 648

(remarks of Sen. Javits); 915 (remarks of Sen. Saxbe).

Cf. Rhode Island Chapter, Association of General Con~

tractors v. Kreps, 450 F. Supp. 338, 353-355 (D. R.I.

1978). Discrimination in the steel industry is well-docu

mented.21

21 United' States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries, Inc., 517 F.2d

826 (5th Cir. 1975), cert, denied sub nom. National Org. of Women

V. United States and Harris v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries, Inc.,

425 U.S. 944 (1976). Kaiser’s two other plants in Louisiana have

been the subject of successful lawsuits charging employment dis

crimination. Parson v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp., supra;

Burrell v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp., supra (consent de

cree, Feb. 24, 1975). A Kaiser spokesmen testified at trial that no

employer in the United States had been free from discrimination

against blacks prior to a given time in history. (Tr. 169). While he

did not know of specific instances of discrimination at Gramercy, it

was not his responsibility to pursue it. (Tr. 168). In his opinion,

the small statistical presence of minorities in the craft groups indi

cated that there had been discrimination in those groups. (Tr. 146).

He testified that minorities had not been permitted to participate in

certain skilled occupations and therefore they couldn’t be available in

any Quantity in the marketplace. (Tr. 146). This was no different at

any of the Kaiser facilities. (Tr. 147).

29

The constitutionality of racial quotas under Executive

Order 11246 has been consistently upheld. E.E.O.C. v.

A.T.&T., supra, 556 F.2d at 178-80; Associated General

Contractors of Massachusetts v. Altshuler, 490 F.2d 9,

16-19 (1st Cir. 1973), cert, denied, 416 U.S. 957 (1974) ;

Contractors Association of Eastern Pennsylvania v. Sec

retary of Labor, supra, 442 F.2d at 176. In requiring

government contractors to take affirmative action, through

the use of quotas if necessary, the Executive Order serves

the substantial governmental interest of correcting the

racial imbalance in the skilled crafts caused by historical

discrimination. The remaining issue is whether the quota

used is necessary to the accomplishment of this purpose,

and, as we have demonstrated in Section 1(2) (b), supra,

on the particular facts of this case, it is.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, amicus respectfully submits

that the judgment below should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Charles A. Bane

Thomas D. Barr

Co-Chairmen

Norman Redlich

Trustee

Robert A. Murphy

Richard T. Seymour

Norman J. Chachkin

Richard S. Kohn

Staff Attorneys

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

733 - 15th Street, N.W.

Suite 520

Washington, D.C. 20005

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae