United States v. Scotland Neck City Board of Education Brief for Respondents

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Scotland Neck City Board of Education Brief for Respondents, 1971. f8299ed0-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0d3cf365-6fb9-4294-870a-87ffe7b4ec5f/united-states-v-scotland-neck-city-board-of-education-brief-for-respondents. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

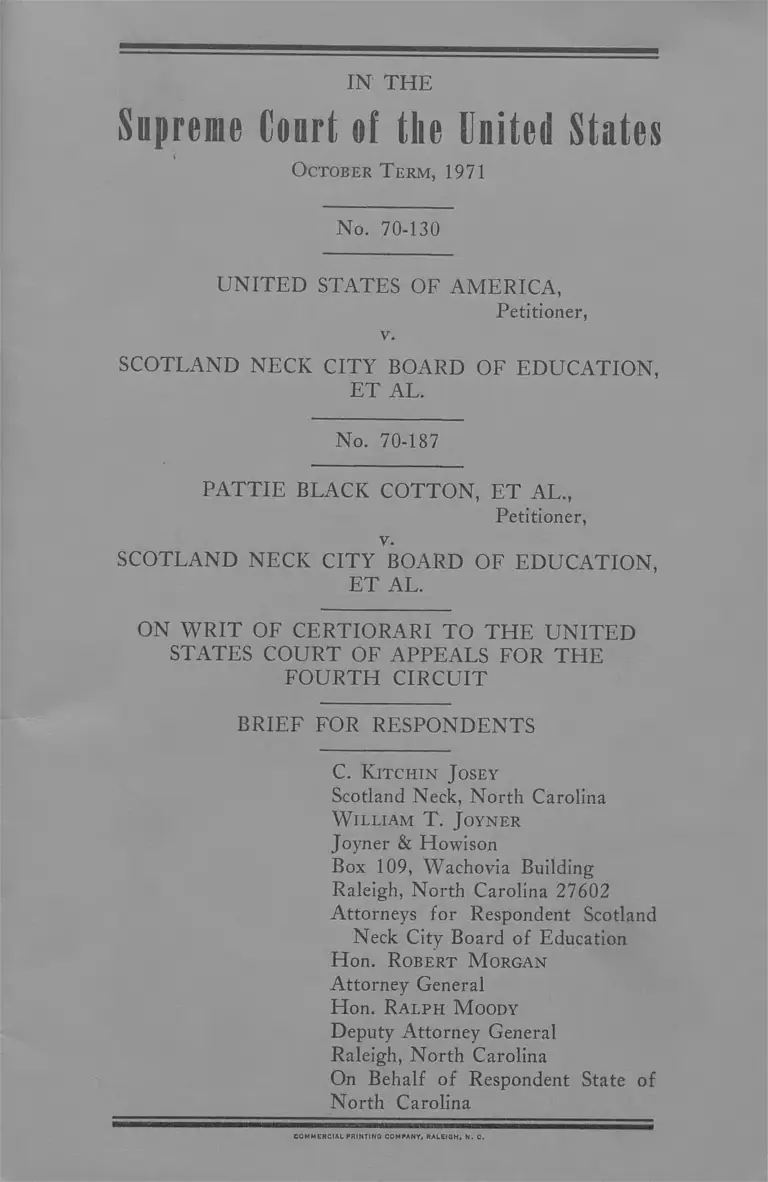

IN T H E

Supreme Court of the United S tates

October T erm, 1971

No. 70-130

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Petitioner,

v.

SCOTLAND NECK CITY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

ET AL.

No. 70-187

PATTIE BLACK COTTON, ET AL.,

Petitioner,

v.

SCOTLAND NECK CITY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

ET AL.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED

STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

C. K itc h in J osey

Scotland Neck, North Carolina

W illiam T. J oyner

Joyner & Howison

Box 109, Wachovia Building

Raleigh, North Carolina 27602

Attorneys for Respondent Scotland

Neck City Board of Education

Hon. R obert M organ

Attorney General

Hon. Ra lph M oody

Deputy Attorney General

Raleigh, North Carolina

On Behalf of Respondent State of

North Carolina

COMMERCIAL PRINTING COMPANY, RALEIGH, N. C.

I N D E X

Question Presented______________________________ 1

Statement______________________________________ 2

A. Three Determinative F acts___________________ 2

B. The Background______________________ 4

C. Chapter 31, 1969 Session Laws of North Carolina 5

D. The Vote ________________________________ 7

E. The Preliminary Injunction___________________ 8

F. The First Further Answer___________________ 9

G. The Advertisement for Contributions_________ 11

H. The Hearing on the Merits and the Decision of

the District Court ________________ :______ 13

I. The Hearings and the Decision in the Court

of A ppeals_______________________________ 15

J. The Decline in School Enrollment Following

the Injunction_____________________________ 16

Introduction and Summary of Argument______________ 17

Argument_______________________________________ 20

I. Four Leading Cases on Dismantling Control Dis

position of This Case and Those Cases Support

the Majority Opinion of the Fourth Circuit___ 20

A. The Brown Cases_____________________ 20

B. The Green C ase______________________ 21

C. The Swann C ase______________________ 22

II. The Jurisdictional Prerequisite for the Assign

ment of Pupils to a School Because of Race is the

PAGE

( i )

PAGE

Finding of Fact That There is a Remaining Vestige

of Segregation in the Situation___ ___________24

III. The Only Vestige of Segregation to be Dismantled

Here Is An Attitude, a Reluctance To Exercise

Freedom of Choice; and Both White Flight and

Black Flight Must Be Deterred in Order to Cor

rect This A ttitude__________________________ 25

IV. The Statute Does Not Deter Dismantling. In

Fact it Has Unique Merits As a Tool For Dis

mantlement, Namely Overcoming The Mental

Attitude Which Obstructs Freedom of Choice__ 29

V. The Plan By the District Court Does Not Meet

the Requirement of Reasonableness and Real

ism -------------------------------------------------------_ 31

VI. Reply To Some Special Points In The Briefs

of Petitioners______________________________ 35

Conclusion ______________________________________ 37

Appendix A _____________________________________ 39

Appendix B ---------------------------------------------------------40

Appendix C ---------------------------------------------------------45

Appendix D ___________________________________ 52

Appendix E ____________________________________ 55

CITATIONS

Cases :

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954) (Brown I) 17, 20, 22

PAGE

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 298

(1955) (Brown I I ) ___________________ 17,20,22

Davis v. Board of Commissioners of Mobile

County, 402 U.S. 33 (1 9 7 1 )______________ 16,32

Green v. New Kent County Board of Education,

391 U.S. 439 (1968) ___________ 5, 6,17,20,21,

22, 26, 27, 30

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S.

450 (1968) _______________________________ 5

Raney v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 443

(1968) ___________________________________ 5

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of

Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) _______ 17,20,22,23,

24, 25, 35, 37

U. S. v. Scotland Neck City Board of Education,

442 F. 2d 575 (4th Cir. 1971)_______ 2, 4, 5, 15

U. S. v. Scotland Neck City Board of Education,

314 F. Supp. 65 (E.D.N.C. 1 9 7 0 )_________ 4, 14

Statutes :

1969 Session Laws of North Carolina, Chapter

31 ------------------------------------------ 5, 6, 7, 9, 14

1969 Session Laws of North Carolina, Chapter

579 ______________________________________ 5

1969 Session Laws of North Carolina, Chapter

628 5

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United S ta tes

O ctober T erm , 1971

No. 70-130

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

v.

Petitioner,

SCOTLAND NECK CITY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

ET AL.

No. 70-187

PATTIE BLACK COTTON, ET AL.,

v.

Petitioner,

SCOTLAND NECK CITY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

ET AL.

ON W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED

STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

We accept the Petitioners’ statement of Opinions below,

Jurisdiction and Constitutional and Statutory provisions in

volved.

QUESTION PRESENTED

We do not accept the statement of the issue in the brief

of either petitioner. Each assumes a conclusion that the

Scotland Neck plan of December 1969 would impair required

desegregation. That is a question which is in issue here.

Our Statement of Question Presented is this:

Does the North Carolina statute, which the District Court

and the Court of Appeals found to be an honest effort to

achieve quality education, meet the requirements of this

Court as a realistic “Interim Corrective Measure” to dis

mantle the remaining vestige of law imposed segregation

in the Scotland Neck Area?

STATEMENT

A. THREE DETERMINATIVE FACTS

We find it necessary to make a statement of what we

think are determinative facts.

At the threshold of such statement we call special attention

to three key facts, the first of which was the subject of a

mere casual reference and the second and third of which

were not mentioned at all in the Statements of the petitioners.

Those three key facts are:

1. The full intent and plan of operations of the Scot

land Neck City Board of Education is set forth in its

First Further Answer and in its published advertisement

soliciting contributions to finance the defense of this

lawsuit. Those papers are so important that we have put

them in an Appendix to this brief. (App. A and B.).

2. The Court of Appeals found “there is nothing in

the record to suggest that the greater percentage of white

students in Scotland Neck is a product of residential

segregation resulting in part from state action.” U.S. v.

Scotland Neck City Board of Education 442 F. 2d 575

at page 582. (App. 1115). Neither brief for the peti

tioners mentioned that quotation.

3. The record shows that, in the 26 months following

the temporary injunction of the District Court of Au

2

3

gust 26, 1969, 46.7 % of the white students left the public

schools of the Halifax County District; thereby increas

ing the black ratio in the district from 77.7% to 85.8%.

(See Table I, App. E ). Because of the importance of

this fact we have placed in an appendix to this brief a

copy of three affidavits of W. Henry Overman dated

September 15, 1970, December 2, 1970, and October 14,

1971 (App. D).

They show school attendance in the Halifax County District

by race for the school year 1970-71 and for October 1971.

Again neither brief for the petitioners mentions this signifi

cant experience.

The original injunction was sought and the reversal of the

Court of Appeals is now sought on the theory that by making

the Black-White ratio in Scotland Neck nearly even there

would be left available less white Scotland Neck students for

distribution among the other schools of the district; namely

that the district ratio would become 80% under the Scotland

Neck plan, an increase less than 3 percentage points in the

Black ratio in that remaining portion of the district.

As said above, the Halifax County district ratio in the

twenty-six month period following the injunction was increased

from 77.7% Black in 1968-69 to 85.8% in 1971-72. (See

Table I, App. E).

The District Court erred in not making a realistic ap

praisal of the prospective student flight.

We submit that the impact of those three facts is strong.

Hereafter in the argument portion of this brief, (infra,

p. 20), we shall point out that the law heretofore declared by

the Supreme Court supports rather than invalidates the

North Carolina Statute.

In the following statement it will be necessary to repeat

some of the facts in Statements for the Petitioners in order

that the facts which we think are so important may be under

4

stood in their proper context. We will attempt to hold

repetition to a minimum.

B. THE BACKGROUND

We have adopted the statement of facts in the District

Court opinion 314 F. Supp. 65 at 67 (E.D. N.C. 1970),

(App. 1062) and in the majority opinion in the Court of

Appeals 442 F. 2d 575 (4th Cir. 1971) (App. 1104). We

will call attention to some additional facts and will present

them argumentatively.

The District Court found: “Scotland Neck, a small town

with a population of approximately 3,000, is located in the

southeastern corner of Halifax County, a rural and agricul

tural region of North Carolina which has a predominantly

black population. The population of the town itself is approxi

mately 50% white and 50% black.” 314 F. Supp. 65 at

67. (App. 1063).

The people, black and white in the area have cooperated

closely and have enjoyed and are enjoying excellent racial

relations. (App. 436).

The residential patterns of Scotland Neck and of the

surrounding territory have not been caused by State action.

The Court has so found. The majority of the Court of Ap

peals said in its opinion “There is nothing in the record to

suggest that the greater percentage of white students in

Scotland Neck is a product of residential segregation re

sulting in part from State action.” 442 F. 2d 575 at 582.

(App. 1115.)

With its economic and geographic attributes it appears

certain that Scotland Neck must achieve and must maintain

two objectives, one, good schools, and two, good racial re

lations.

That background lends meaning to all that was done by

the people of Scotland Neck as recorded in this case, by the

5

Legislature of North Carolina and by the Scotland Neck

City Board of Education.

C. CHAPTER 31, 1969 SESSION LAWS OF NORTH

CAROLINA

The Majority Opinion in the Court of Appeals describes

carefully and accurately the struggle of the people in Scot

land Neck to get a better school and their frustration at the

hands of the County School Board and of the Legislature.

Those efforts antedated the decisions of this Court in

Green v. School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S.

430 (1968), Rainey v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 443

( 1968) and Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S.

450 (1968). The Majority Opinion says “Local control and

increased taxation were thought necessary to increase the

quality of education in their schools. Previous efforts to up

grade Scotland Neck schools had been frustrated.” 442 F.

2d 575 at 580. (App. 1104).

Early in the 1969 Session of the North Carolina Legisla

ture the legislative act here in question was enacted (March 3,

1969, Chapter 31, 1969 Session Laws). That statute was

not a part of a package. It stood alone. It antedated the

Warrenton School Bill enactment (May 23, 1969, Chapter

579, Session Laws of 1969) and the Littleton-Lake Gaston

Laws (May 26, 1969, Chapter 628, Session Laws of 1969).

Both the Scotland Neck proponents and the Legislative en

actors of the bill must have been familiar with the Green case

and its companion decisions. They must have concluded that

the Scotland Neck bill met the requirements of those decisions.

They knew that the Supreme Court of the United States in

a unanimous opinion in the Green case had said “There is no

universal answer to complex problems of desegregation;

there is obviously no one plan that will do the job in every

case . . . Moreover, whatever plan is adopted will require

evaluation in practice, and the Court should retain jurisdic

tion until it is clear that state imposed segregation has been

completely removed.” 391 U.S. 430 at 440-41 (1968).

6

Further they knew that the Green case said “Where it

offers real promise of aiding a desegregation program to

effectuate conversion of a state-imposed dual system to a

unitary, nonracial system there might be no objection to allow

ing such a device to prove itself in operation. On the other

hand, if there are reasonably available other ways, such for

illustration as zoning, promising speedier and more effective

conversion to a unitary, nonracial school system, ‘freedom

of choice’ must be held unacceptable,” 391 U.S. 430 at 442,

and “The Board must be required to formulate a new plan,

and, in light of other courses which appear open to the

Board, such as zoning, fashion steps which promise realisti

cally to convert promptly to a system without a ‘white’ school

and a ‘negro’ school, but just schools.” 391 U.S. 430 at

442.

The proponents and the legislative enactors also knew

that as a footnote to the quotation last given above the Court

had said “In view of the situation found in New Kent County,

where there is no residential segregation, the elimination of the

dual school system and the establishment of a ‘unitary, non

racial system’ could be readily achieved with a minimum of

administrative difficulty by means of geographic zoning—

simply by assigning students living in the eastern half of the

county to the New Kent School and those living in the west

ern half of the county to the Watkins School.” 391 U.S. 430

at 442, N. 6.

The proponents and the enactors knew that an authorita

tive spokeswoman for the Federal Department of Flealth,

Education and Welfare had made public announcement,

which was in the press and was put into this record, that the

Department had no interest in the Halifax County bill if it

treated Blacks and Whites alike. (App. 776.)

Further the proponents and the legislators knew (and

acted on that knowledge) that the thrust of the Halifax

County bill, its scope and its certain effect, was to set up a

7

school district with about a 57% white pupil residence and

43% black pupil residence. They knew that they were to

be treated precisely alike, that there would be no discrimina

tion. They knew that the structure of state-imposed segrega

tion within the borders of Scotland Neck would be totally and

completely demolished.

The Legislators also knew that the operation under the

Halifax County Bill and all matters of administration such

as the making of transfers in and out of the Scotland Neck

School would be under the certain and careful supervision

of the Federal District Court for the Eastern District of

North Carolina. They knew that no child could be trans

ferred from the Scotland Neck School to a Halifax District

School against the wishes or requirements of the Court.

So, the Legislators stopped at the establishment of the

district. Thereafter, transfers and other administrative mat

ters were problems between the Scotland Neck City Board

of Education and the Halifax District Board of Education

and the District Court for the Eastern District of North

Carolina.

The intent of the Legislature was plain. It was the enact

ment of the bill, which speaks for itself. That bill accom

plished the purpose of the Legislature completely. In a later

section (infra p. 13) we will discuss “Motivation”, includ

ing a desire to deter the withdrawal of students from the

public school system.

D. THE VOTE

Following the passage of the statute there was held a

vote of the people. They approved and accepted the terms

and conditions of the bill and authorized a special school

tax of 50c on the $100 of property valuation within the

boundaries of Scotland Neck.

There are three things which we underscore about that

vote which occurred on April 8, 1969:

8

1. More people voted than had ever voted before in a

Scotland Neck election (Deposition of Henry L. Harrison,

p. 16).

2. The affirmative majority was very unusual — 71%.

(App. 1062).

3. It is a matter of general knowledge that any approval

of a special school tax in North Carolina is very rare these

days.

After the resounding approval by the voters the Scotland

Neck City Board of Education proceeded to prepare for the

opening of its school.

E. THE PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

On June 16, 1969, complaint was filed in the District

Court of the United States by the United States Department

of Justice against the Halifax County Board of Education.

That complaint sought relief on three grounds stated es

sentially as follows:

12. The enactment and implementation of Chapter

31 commands, encourages and fosters segregation based

on race or color in the operation of the public schools

of Halifax County.

13. Chapter 31 sets up a separate school system which,

on grounds of its size and pupil enrollment, has no edu

cational justification.

14. The enactment and implementation of Chapter

31 . . . denies equal protection of the laws to Negro

children of school age residing in the jurisdiction of the

Halifax County Board, outside the boundaries of Scot

land Neck, in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the United States Constitution. (App. 29).

On July 17, 1969, petitioner for the first time filed motion

for preliminary injunction. (App. 39). The Scotland Neck

9

City Board of Education (hereinafter called the School

Board) was not made a party at the time of the filing of

the Complaint. On August 16, 1969, the School Board and

its members were notified that they had been made parties

and that a preliminary answer must be filed by August 20,

(App. 60), and that a hearing on a motion for a preliminary

injunction would be held in Raleigh, North Carolina on

August 21. (App. 60). On August 21 those defendants found

that they faced a two Judge District Court, composed of

Chief District Judge Algernon L. Butler and District Judge

John D. Larkins (in whose division Scotland Neck lies).

After hearings on August 21, 22 and 23 the two Judge Court,

on August 25, entered a preliminary injunction against the

School Board, stopping all of its activities. (App. 788-89).

The August 25th Order establishing the Preliminary Injunc

tion made it clear that the District Court was not declaring

the statute unconstitutional. Rather it condemned the effect

of the operation of the transfer provision. The District Court

said in its memorandum opinion pursuant to the order, “with

out determining the constitutionality of Chapter 31 of the

1969 Session Laws of North Carolina, the act in its applica

tion creates a refuge for white students and promotes segre

gated schools in Halifax County.” (App. 792).

F. THE FIRST FURTHER ANSWER

On September 3, 1969, the City Board of Education, with

permission by the Court filed an Amended Answer, suf-

planting the answer which it had hurriedly prepared and

filed on four days requirement by the District Court. We

submit that the allegations of that Answer and the filing

of that Answer are so important in determining the issues

in this appeal that we included in an appendix to our brief, for

ready reference, t&it First Further Answer (App.

A). We call to the special attention of this Court paragraph 8

and the prayers of that Answer which read as follows:

10

8. It is the present intention of this Defendant, and

this Defendant makes this continuing representation,

that, if and when there is removed the temporary in

junction barrier preventing operation under the Statute,

Defendant will confine its student body to those students

residing within the geographical limits of the Town of

Scotland Neck, plus or minus such student transfers as

may be in conformity to the law and/or Court order or

orders applicable to Defendant, and in conformity to a

plan of limitation of transfers to be prepared by De

fendant and submitted to this Court.

WHEREFORE, this Defendant respectfully prays

that:

1. The Court declare to be constitutional Chapter

31 of the 1969 Session Laws of North Carolina;

2. The Court dissolve the temporary injunction here

tofore issued in this cause on the 25th day of August,

1969;

3. The Court retain jurisdiction of this cause for the

receipt of a plan of transfer to be submitted by the De

fendant to the Court and for the hearing of any objec

tion that may be filed thereto.

We submit that, by such filing and such commitment by

the Defendant Board, it severed the question of the possi

bility of contaminating performance from the question of the

constitutionality of the statute. Thereafter transfer perform

ance was not to be made by the Board first and subject to

attack if opponents desired, but, rather, was to be made only

after approval by the Court of what was to be done. That

is a unique and distinctive feature in this case.

Furthermore, we submit that by that action the City

Board fortified its contention with respect to the intent of

the proponents of the statute, namely that the improvement

11

of the quality of education was the central dominant moti

vating factor of the proponents of the bill. The Board, in

essence, was saying plainly and convincingly that we will

take as the basis of a new and better school the residents

within the borders of Scotland Neck together with special

tax money and local control; these will be our prime work

ing tools for school betterment; beyond those basic essentials

we will proceed only in such manner as shall receive the prior

approval of the Court.

We submit that, when this matter was presented to the

District Court for determination on its merits in December

1969, there was presented only the question of the constitu

tionality of the statute.

G. THE ADVERTISEMENT FOR

CONTRIBUTIONS

The Temporary Injunction had tied the hands of the City

Board in every respect, including the denial of the use of

any of the tax money to defend this suit. Defense had to be

financed, if at all, by public contributions. On October 10,

1969, the Scotland Neck City Board caused to be printed

in the newspaper published in that community, The Scotland

Neck Commonwealth*, an advertisement soliciting contribu

tions in aid of defense of the pending suit. That advertise

ment was signed by the Chairman and each other member

of the Board. It was evidence of the publicly proclaimed in

tent of the Board. It was offered and received in evidence

in the District Court. (App. 964). We think that the con

tents of that advertisement are so important with respect

to motive, intent and future operations that they are worthy

of special attention. We have included a copy of that ad

vertisement in Appendix B to this Brief. We here call the

Court’s special attention to the language as follows:

1. The special act sets up a special school district

with lines which are just the same as those of the long

existing city limits. There is no change in the lines.

12

2. The district embraces all children of school age

living in our Scotland Neck Community. It is contem

plated by the Statute, it is required by law, it is the in

tent of this Board that every child living in this com

munity shall be treated just the same, regardless of race,

creed or color. There will be no segregation under our

operation.

3. The basic school population of our community,

would be approximately 57% white and 43% negro. We

do not know of any complaint which has ever been made

anywhere of such a ratio.

4. Transfers out of or into the Scotland Neck Schools

would be made in accordance with a plan or plans of

transfer to be prepared by our board and filed with the

Court, in order that any objections to such plans could be

made to the Court and heard by it.

5. Every operation of our Board would be in the

plainest kind of a spotlight, in the spotlight of public

opinion and the spotlight of Court observation.

6. It is the firm intent of our Board, and the firm

intent of the people of Scotland Neck, to make our new

School District Work, to make ours an outstanding

school, not a “segregated school,” not an “integrated

school,” but just a school “for all of our children with

out regard to race, creed or color.”

7. It is our firm conviction that the successful opera

tion of “just a school” would be good for our community

of Scotland Neck, good for our County of Halifax,

good for our State and good for our Nation. The wel

fare of Scotland Neck, and possibly its survival, depend

upon the success of just such a school.” (App. B.)

13

H. THE HEARING ON THE MERITS AND THE

DECISION OF THE DISTRICT COURT

Approximately three months after the filing of the First

Further Answer and approximately two months after the

advertisement soliciting defense funds, the matter was heard

on the merits in the District Court on December 17-18,

1969. At that hearing there were presented exhibits, deposi

tions and witnesses as appear in the record. We call special

attention to one phase of that record. It shows that the de

fendant City Board of Education presented as a witness and

examined Chairman Shields of the Scotland Neck City Board

of Education. His testimony is set forth in App. 961-965

and is reproduced as Appendix C to this brief. Mr. Shields

covered the subjects of the statements made by his board in

its First Further Answer and in the Advertisement for Con

tributions. He testified as to the quality of the community

support. At the conclusion of his testimony he was tendered

for cross examination. Counsel for plaintiffs said “No ques

tions, your honor.” (App. 965). Immediately after the testi

mony of Mr. Shields the other four members of the Scot

land Neck City Board of Education were sworn and pre

sented as witnesses. They were requested to raise their hands

if they agreed with the testimony given by Mr. Shields. The

record (App. 966) (reproduced here as Appendix C to this

brief) shows that “each member of the board held up his

hand.” That page of the record shows that those four wit

nesses were tendered for examination by the Court and for

cross examination. The record shows that counsel for plain

tiffs stated “No questions.” It further shows on that same

page that no question was asked by either member of the

Court.

In addition to that most convincing acknowledgment of

the sincerity of the members of the Board and of the truth

of their expressions, we call attention to the next impressive

fact; that at the hearing on December 17-18, 1969, the

plaintiffs did not produce one witness who questioned the

14

honesty of those Board members or the truth of anything

that they had said in either of those important documents or

on the stand at the hearing.

We call attention to the fact that at no time did plaintiffs

produce even one witness who was a resident of Scotland

Neck and who questioned the sincerity of the objective to

achieve a better school or who complained about either the

enactment of the statute or any contemplated operation un

der it.

The District Court excepted, from its consideration of the

constitutionality of the Statute, the performance matters

which occurred prior to the filing of the First Further Answer.

It did find that the Statute “. . . interferes with the de

segregation of the Halifax County School System, in accord

with the plan adopted by said board to be implemented on

or before June 1, 1970,” 314 F. Supp. at 78. (App. 1083).

Necessarily, operation under the Statute would require a

change of the plan made for a district which embraced Scot

land Neck. The District Court made no effort to compare

the quality of the “interim corrective measure” presented by

the plan which had theretofore been adopted for the whole

district and the desegregation which would occur under the

Statute.

The District Court made very plain what was the sole

basis for its decision. It said:

Therefore, this Court’s findings of fact that the legis

lative bill creating the district was at least partially mo

tivated by a desire to stem the flight of white students

from the public schools, the Court must find that the

act is unconstitutional and in violation of the Equal Pro

tection Clause of the 14th Amendment and must enter

permanent injunctive relief for the plaintiff. 314 F. Supp.

at 78. (Emphasis added.) (App. 1084).

15

I. THE HEARINGS AND THE DECISION IN THE

COURT OF APPEALS

In due course the appeal from the District Court was heard

on September 16, 1970, by a panel of the Court of Appeals

consisting of Judges Boreman, Bryan and Craven. Subsequent

ly by order of the Court there was an oral argument on De

cember 7, 1970, before the full Court sitting en banc.

On March 23, there was a decision by the majority of the

Court, 442 F. 2d 475 (4th Cir. 1971) (App. 1104). The

opinion was by Judge Craven. Dissents were filed by Judges

Sobeloff and Winter. 442 F. 2d at 588. (App. 1126).

We think it would serve no useful purpose to repeat in

any detail the points of the opinions. The differences of

opinion between the majority and the dissenters were made

clear.

The majority speak of desegregation.

The dissenters speak of integration.

The majority speak of flexibility in handling the prob

lems of dismantling.

The dissenters speak of rigidity of treatment and of fixed

ratios.

The majority speak of danger of flight of students to

private schools.

The dissenters do not speak at all about the danger of

flight of students to private schools.

The opinions of the majority are more persuasive and

more realistic than are the dissents. The majority looked

toward peace and cooperation, progress and better educa

tion.

16

J. THE DECLINE IN SCHOOL ENROLLMENT

FOLLOWING THE INJUNCTION

The enrollment figures for the Halifax County School Dis

trict for the school year 1968-69 were Black 8196 (77.7%)

and White 2357 (22.3%). (Overman deposition—App. 219)

(Table I, App. E ) .

The enrollment figures for the Halifax County District

for the school year 1970-71 and for the school year 1971-72

were furnished by affidavits of Superintendent Overman.

They are three in number dated September 15, 1970, (App.

1100), December 2, 1970, (App. 1102), October 14, 1971,

(App. 1153). The first two were put into the record before

the Court of Appeals without objection. The third was added

to the record of the Court of Appeals by consent and Stipu

lation of Counsel, (as appears in footnote App. 1153). The

admission and consideration of these three affidavits appears

to be in accord with the language and action of the Court

in Davis v. Board of Commissioners of Mobile County, 402

U.S. 33 (1971) at page 37 where the Court said: “These

figures are derived from a report of the school board to the

District Court; they were brought to our attention in a

supplemental brief for petitioners filed on October 10, 1970,

and have not been challenged by respondents.” Thereafter

the Court said, page 37, “The measure of any desegregation

plan is its effectiveness.”

Because of the significance of these three affidavits in our

presentation of our case we have attached them to this brief

as Appendix D.

The enrollment figures for that same district on Sep

tember 15, 1970, were Black 7716 (84.3%) and White

1446 (15.7%). (Overman affidavit—App. 100). The en

rollment figures for the same district on October 14, 1971,

were Black 7585 (85.8%) and White 1255 (14.2%). (Over

man affidavit App. 1153) (Added to record by stipulation of

the parties). In the 26 months from the signing of the injunc

17

tion to October, 1971, 1102 white pupils (46.7%) and 611

black pupils (7.5 % ) had disappeared from the district schools

(computation from Table I, App. E).

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The law decisive of the issue here is declared in the Brown

cases, the Green case, and the Swann case. The Brown cases

(1954, 1955) struck down all laws requiring segregation in

the public schools.

The Green case (1968) required that there be dismantled

every identified remaining vestige of law imposed segrega

tion. It spoke of the uprooting of the causes for the failure of

freedom of choice to work. It warned of the variety of condi

tions to be and of their complexity. It ordered flexi

bility of treatment and the exercise of discretion and realism.

The Swann case (1971) reflected experience under the

Green case. It declared that the jurisdiction of the Court in

this vestige uprooting process was equitable in nature; that

jurisdiction in a specific case must be based on the identifica

tion of the vestige; that any Court-directed pupil assign

ment, made on the basis of race is “ . . . an interim corrective

measure.” It was made plain that such interim corrective

measure was to be directed to the uprooting or removal of

the causes of such remaining vestige.

The only identification, in this case, of a remaining vestige

of law imposed segregation was that nearly all of the black

pupils resident in the Scotland Neck City limits had failed

to exercise a choice to go to the Scotland Neck school and

that many white pupils residing in rural areas outside of

Scotland Neck had chosen to attend the Scotland Neck school.

Admittedly some “interim corrective measure” was indi

cated if the requirements of this Court were to be met.

Any such measure must be fashioned in a manner to tend

to correct the causes of failure of the pupils of each race to

exercise normal and race-oblivious choice of schools.

18

Before fashioning any such corrective measure there must

be a careful search for those causes.

Here is the heart of this case.

Obviously the most proximate cause of the failure of

pupils resident in the Scotland Neck area to exercise freedom

of choice was the reluctance of those pupils, of each race,

to attend a school in which the pupils of another race are

heavily predominant in numbers.

So, a search must be made for the causes of such re

luctance.

The readily apparent cause is the feeling or fear that a

small minority group of students, black or white, would face

isolation, hostility, danger of physical injury, and an educa

tion not fashioned properly for that small minority group.

Any realistic interim corrective measure must be directed

toward removing or abating those fears on the part of the

people of each race.

The Scotland Neck Plan would have the following favor

able forces working for it:

1. The school attendance zone follows a natural resi

dential patern.

2. The students resident in that district are very nearly

evenly divided racially.

3. There would be special tax money for the making

of a better school.

4. There would be strong neighborhood support for

the well balanced school.

5. The balanced condition of the races would tend to

deter flight from the public schools of the district ^

by both whites and blacks.

19

6. The Scotland Neck school has the realistic aspect

of working now and of being permanent.

7. A successful school in Scotland Neck could become

an observed success and tend to abate racial distrust

through the local area, through the Halifax District and

beyond.

On the other hand, the Court enforced plan which it put

into effect would have marked disadvantages in each of those

seven fields.

1. It does not follow a natural residential patern.

2. It does not achieve one school in which there would

be a nearly even white-black ratio.

3. There would not be generated any additional

money for the improvement of any school.

4. It weakens rather than strengthens the neighborhood

support.

5. It would tend to increase both white and black

flight from the schools.

6. It does not reflect a realistic approach and does not

have any aspect of permanence.

7. It could not succeed and its failure would increase

racial distrust in the whole district rather than abate it.

The experience of the Court-adopted plan proves the

defects which we have listed above. In the 26 months follow

ing the August 26, 1969, injunction issued by the District

Court 46.7% of the white pupils and 7% of the black pupils;

disappeared from the Halifax County School District. (Com

putation made from the figures taken from Table I,

App. E).

20

ARGUMENT

I .

FOUR LEADING CASES ON DISMANTLING CON

TROL DISPOSITION OF THIS CASE AND THOSE

CASES SUPPORT THE MAJORITY OPINION OF

THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

This case is unique on its facts. We know of no other

similar case which has been decided by this Court.

It is our contention that the issues in this case are controlled

by what this Court has said in the four leading cases on

dismantling and that those cases indicate an affirmation of

the opinion of the Court below. Those cases are:

Brown v. Board of Education,. 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

(Brown I)

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 298 (1955)

(Brown II)

Green v. School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S.

430 (1968)

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (April 20, 1971)

A. THE BROWN CASES

The Brown cases struck down the bar of all state-imposed

racial discrimination, discussing at length the problem of

desegregation of the public schools. Much was said about

the complexity of the desegregation problem, the equitable

nature of the remedy and the need of flexibility in the ap

plication of the equitable remedy. It was made clear that

there was no rigid formula for desegregation and that dis

cretion should be left to the decision of the administrative

21

bodies and the lower courts. The Brown cases made it clear

that the Court had jurisdiction to desegregate but that it

had no jurisdiction to integrate, to mix the races for the sole

purpose of achieving some desired balance. The Court was

very careful in those two decisions to confine its opinion and

mandate to desegregation. It spoke only of desegregation.

B. THE GREEN CASE

Green v. School Board of New Kent County, 391

U.S. 430 (1968), marked the pronouncement of a new and

difficult concept. The Court said that Freedom of Choice

had failed to accomplish the desired desegregation in many

instances. The Court held that it was not sufficient to

destroy the laws requiring or supporting segregation. It

held that the Court had the duty and that it had the equitable

power to require that discriminatory conditions caused by

law imposed segregation be undone.

Again the Court made it very plain that the jurisdiction

of the Court was founded on illegal segregation, and that

its action was limited to requiring the correction of conditions

resulting from illegal segregation. The Court described spe

cifically its field of action as the undoing of the remaining

vestiges of condemned segregation.

Again the Court emphasized the variety of possible reme

dies, the necessity of flexibility, the discretion to be left to

local administrative authorities and to the lower courts. It

even spoke of trial and error methods. It strongly com

manded realism in judgment and the search for a plan “that

promises realistically to work, and promises realistically to

work now.” 391 U.S. at 439.

The Court said at page 439 :

The obligation of the District Court, as it always has

been, is to examine the effectiveness of a proposed plan

22

in achieving desegregation. There is no universal answer

to complex problems of desegregation; there is obviously

no one plan that will do the job in every case . . . More

over, whatever plan is adopted will require evaluation in

practice, and the Court should retain jurisdiction until

it is clear that state-imposed segregation has been com

pletely removed.

In footnote 6 at page 442 the Court pointed out that the

Kent County problem could be solved by geographic zoning.

In that respect the facts of Green are similar to the facts

in the Scotland Neck case.

The Court in Green, as in Brown I and Brown II, was

careful to speak of desegregation rather than of integration.

C. THE SW ANN CASE

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (April 20, 1971) applied, with elaboration, the

pronouncements of the Brown cases and of the Green case.

It applied those principles to reasonable busing of students

to achieve the dismantling of a law imposed segregated struc

ture. Again the Court spoke carefully of desegregation and

avoided the term integration. It adhered to and emphasized

the pronouncement that jurisdiction was founded on the need

for dismantling a remaining vestige of law imposed segrega

tion.

With respect to flexibility of a remedy the opinion in

the Swann case quoted from Brown I as follows:

In fashioning and effectuating the decrees, the Courts

will be guided by equitable principles. Traditionally,

equity has been characterized by a practical flexibility in

shaping its remedies and by a facility for adjusting and

reconciling public and private needs. 402 U.S. 1 at 12.

23

On page 15 the Court said “ . . . the scope of a district court’s

equitable powers to remedy past wrongs is broad, for breadth

and flexibility are inherent in equitable remedies.”

In the Swann decision the Court said:

The District Court held numerous hearings and received

voluminous evidence. In addition to finding certain

actions of the school board to be discriminatory, the

Court also found that residential patterns in the city

and county resulted in part from federal, state,, and local

government action other than school board decisions.

(emphasis added) 402 U.S. 1 at 7.

Again we think it important here to emphasize the fact

that the District Court in the Scotland Neck case did not

make any such finding. Furthermore the Court of Appeals

majority found “there is nothing in the record to suggest

that the greater percentage of white students in Scotland

Neck is a product of residential segregation resulting in part

from state action”, 442 F. 2d 575 at 582. (App. 1115).

The Court in the Swann case approved the order of the

District Court requiring busing of students to achieve a dis

mantling result as action within the sound discretion of the

District Court. It is most important here, we think, to point

out that that approval was reached on the basis of a District

Court Finding of Fact that the Charlotte residential patterns

had resulted in part from state-imposed segregation.

On page 28 the Court made this important and entirely

clear statement, “absent a constitutional violation there would

be no basis for judicially ordering assignment of students on

a racial basis.”

The Court said:

The District Judge went on to acknowledge that vari

ation from that norm may be unavoidable. This contains

24

intimations that the “norm” is a fixed mathematical

racial balance reflecting the pupil constituency of the sys

tem. If we were to read the holding of the District Court

to require, as a matter of substantive constitutional right,

any particular degree of racial balance or mixing, that

approach, would be disapproved and we would be obliged

to reverse. The constitutional command to desegregate

schools does not mean that every school in every com

munity must always reflect the racial composition of the

school system as a whole. 402 U.S. 1 at 23-24.

As we view the Swann case it held plainly that the con

stitution does not require the same ratios in all areas of a

district and the constitution does not require assignments

out of a residential area in the absence of a distortion of

residential patterns caused by state-imposed segregation. As

we understand it, the principal point in the Swann case is

that the constitutional powers of assignment out of residen

tial areas cannot be supported by a mere desire for mixing;

it can only be supported by the necessity to dismantle some

remaining part of a segregated structure.

Since residential patterns in Scotland Neck were not

caused in any respect by state-imposed segregation, no vestige

of the segregated structure would remain in the Scotland

Neck District.

II.

THE JURISDICTIONAL PREREQUISITE FOR

THE ASSIGNMENT OF PUPILS TO A SCHOOL

BECAUSE OF RACE IS THE FINDING OF FACT

THAT THERE IS A REMAINING VESTIGE OF

SEGREGATION IN THE SITUATION

At the very outset of the consideration of the merits of

the issue in this case we are faced with a confusing paradox.

The wrong to be remedied was school segregation based

only on race.

25

So there is the appearance of correcting one wrong by the

imposition of another wrong.

About this situation the Court said this in Swann under its

subheading “ (3) Remedial Altering of Attendance Zones.”

“As an interim corrective measure, this cannot be said to be

beyond the broad remedial powers of a Court. Absent a

constitutional violation there would be no basis for judicially

ordering assignment of students on a racial basis.” 402 U.S.

at 27-28 (1971).

So, we look to see what, in the Scotland Neck case is a

remaining vestige of law imposed segregation which must

be corrected.

III.

THE ONLY VESTIGE OF SEGREGATION TO BE

DISMANTLED HERE IS AN ATTITUDE, A

RELUCTANCE TO EXERCISE FREEDOM OF

CHOICE; AND BOTH W HITE FLIGHT AND

BLACK FLIGHT MUST BE DETERRED IN ORDER

TO CORRECT THIS ATTITUDE

Before the statute in this case was enacted there was

visible a remaining vestige of law imposed segregation in the

Scotland Neck District. With a residential black student

population of about 299 only 40 had chosen to go to the

Scotland Neck school. (App. 732). Further, a large number

of white students living beyond the borders of Scotland Neck

had seen fit not to attend the rural school near to them, but

had chosen to attend the Scotland Neck school.

To correct that situation temporarily would be simple, by

assigning all students resident in Scotland Neck to the Scot

land Neck School and to control the transfers of nonresident

white students seeking to enter the Scotland Neck School.

Whether that would be acceptable as a proposed dis

26

mantling would seem to necessitate inquiry as to the root

cause of the situation to be corrected. That raises the question

why Freedom of Choice had failed to work in that area.

To discuss that question with clarity it is necessary to

take a long, hard and realistic look at the situation in order

to try to find what remnant or root of segregation is the

focal point for the dismantling procedure.

We look closely at the controlling case, Green v. School

Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968). What

was the root cause of the situation which gave the Court

such concern there? It was a mental attitude.

In New Kent County as in Scotland Neck, it had been

made plain that Black students were not going to exercise

their freedom of choice to go to a heavily predominant

white school. It is just as plain that white students were

not going to exercise their freedom of choice to go to a

heavily predominant black school. So, Freedom of Choice

failed to work effectively because of the mental attitude of

people, the black and white students and their parents, be

cause of their reluctance to exercise that freedom.

We have not found that this Court has ever undertaken

to make any statement as to precisely what was the feeling

concerning that reluctance.

Neither the District Court nor the Court of Appeals nor

the petitioners in this case have undertaken to analyze the

causes of that mental attitude, the causes of that reluctance

to exercise Freedom of Choice.

However, the Green case approached the problem in a

footnote (Green v. School Board of New Kent County, 391

U.S. 430 at 440 N. 5). That footnote indicated the nature and

some possible causes of that reluctance.

We do not undertake, and we are not qualified to under

27

take, a thorough analysis of mental attitudes. However some

significant conclusions seem to be clear.

We submit that it is demonstrated by the record in this

case and by the opinion in the Green case that both the Black

students and the White students, and their parents, hold the

following firm mental apprehensions or fears, whether justi

fied or not:

That a small minority group of students, Black or White,

would face isolation, hostility, danger of physical injury

and an education not fashioned properly for that small

minority group.

It is certain, we submit, that each of those fears or

thoughts has been created or intensified by the law imposed

segregation of the past.

To be realistic, we submit that those mental conditions or

fears constitute a plank or a rafter or a root of segregation

structure which the Green case and this case seek to dis

mantle.

An attitude cannot be changed by mandate or by compulsion

to action. Either provokes resistance. A change of attitude

can come only from experience and/or observation.

So, the courts in the Green case and its companion cases

have gone to the extreme length of assigning children to

schools because of their race in order that experience and

observation may correct the mental attitude, may eliminate

the reluctance to exercise Freedom of Choice.

The dissolving of the fears we have mentioned can be

accomplished only by experience and/or observation. The

students, of each race must learn that whites and blacks can

associate in schools with profit, that they can achieve mutual

respect and dignity and a desire to cooperate in securing

quality education.

28

We submit that “any interim corrective measure” directed

toward resolving those fears or prejudices, must be directed

to the children and parents of both races. The “reluctance”

which we have mentioned is as objectionable in the mind of

the white child as it is in the mind of a black child. To

attempt to correct it in the black mind without giving any

consideration to correction in the white mind will certainly

cause the corrective measure to fail of its purpose.

We submit that in any realistic appraisal of the chances

for success of a proposed corrective measure, consideration

must be given the potential result of such corrective measure

on white or black flight from the schools.

The “flight” from the public schools for a substantial

number of white or black students to avoid the impact of

a proposed corrective measure, will augment rather than

diminish the racial distrust which constitutes the “remaining

vestige of law imposed segregation” in the Scotland Neck

area.

The massive flight of white students from a school is

certainly going to cause an increase of racial fears, distrust

and animosities. That will surely threaten the achievement

of the desired dismantling and impair the quality of the edu

cation.

A consideration to deter threatened white or black flights

is a good consideration and not an evil consideration. If

there is a realistic threat of any such “flight” it cannot be

ignored.

In the District Court it was not ignored. It was the basis

for the erroneous condemnation of the statute by that District

Court. We submit, as the Court of Appeals found, that that

basis was entirely unsound. That was the crucial error made

by the District Court.

In the opinion of the majority of the judges on the

29

Court of Appeals the prospective “white flight” was not

ignored. It was a cause for great concern to that majority.

In the dissenting opinions in the Court of Appeals the

white flight was ignored.

In the briefs for both the petitioners the negative effects of

white flight on dismantling and on quality education have

been ignored.

Each petitioner takes completely inconsistent positions.

In both briefs the petitioners applaud the dissenting opinions

of the Court of Appeals Justices who condemned the statute

because it would keep approximately 400 white students in

their home school in Scotland Neck (a 50% white ratio)

rather than distributing approximately 300 of those white

Scotland Neck students to “black schools” to raise the ratio

in those schools about 3 points. They spent scores of pages

on that argument. They base their whole case upon the

prospective, corrective effect on the district, of assigning

300 white students to schools beyond the borders of Scotland

Neck. Their total argument is based on the value to the

unitary movement which will come from the addition of those

300 white students to the Halifax County School District.

With complete inconsistency they shut their eyes to the

loss from the Halifax County District schools of 1,102

white students who fled from the district schools following

the preliminary injunction and later the permanent injunction,

a loss which increased the black ratio in the district to

85.8%. (Table I, App. E).

IV.

THE STATUTE DOES NOT DETER DISMAN

TLING. IN FACT IT HAS UNIQUE MERIT AS A

TOOL FOR DISMANTLING, NAMELY OVERCOM-

30

ING THE MENTAL ATTITUDE W HICH OB

STRUCTED FREEDOM OF CHOICE

To support the validity of the Statute it is only necessary

to find that the statute does not go beyond the limits of the

sound discretion vested in the initial administrative policy

making body, here the Legislature.

We do not contend that the dismantling of segregation

was a primary motive behind the Legislative action.

In actual fact the primary motive of the Legislature was

better schools, to be secured by more money, local super

vision and support, and the deterring of the movement of

students to private schools.

But the Legislature, necessarily reached a conclusion that

the Statute did meet the requirements announced in the Green

case. So, we take a close look at the statute in the light of

the Green case.

Possibly the best way to prove the acceptability of the

statute is to compare its dismantling features with those of

the District Court plan put into effect after operation under

the statute was enjoined.

First we set forth what we submit are the major points of

dismantling found in the Scotland Neck Statute.

a. The statute follows the lines of a natural residential

pattern. The basic natural preference of a child is to

attend a school in the neighborhood in which he lives,. An

unnatural reluctance to attend such local school can be

overcome more quickly and more permanently if the

effort is made in the home neighborhood. The attack

should be concentrated locally.

b. A nearly even division of students between blacks

and whites avoids any possible contention that such a

31

division embraces any assertion of superiority of either

race. Such even division would lessen the fears of bodily

harm by a small minority and would overcome the in

evitable reaction of a small minority toward aggressive

and violent self-assertion.

c. The school in Scotland Neck will receive unusually

strong neighborhood support. That will help to assure

the success of the dismantling process.

d. The Scotland Neck District offers the opportunity

of a helpful demonstration of the achievement of peace

and educational progress by cooperation in school work

between blacks and whites.

e. The Scotland Neck District tends to deter the

movement of students to private schools.

f. The Scotland Neck District has an aspect of per

manence.

We compare the District Court Plan in the light of features

stated above.

V.

THE PLAN ADOPTED BY THE DISTRICT COURT

DOES NOT MEET THE REQUIREMENT OF REA

SONABLENESS AND REALISM

a. The District Court Plan departs radically from a

natural residential pattern. Of the 400 white school chil

dren resident in Scotland Neck the District Plan and the

petitioners would assign approximately 250 students out

side of the Scotland Neck limits (if those students did not

move out of the public school system). (App. 681, &&2).

They would be so assigned solely on the basis of race.

That would be a cause of continued discontent, dissention

and rebellion as long as it lasts.

32

b. The District Court Plan of assignment out of a

residential neighborhood against the wishes of the as

signed students would be a continual emphasis of race.

The objective of increasing to 22% the ratio of white

students in outlying districts invites the charge that it is

an assertion of racial superiority. It adds fuel to the

fire of racial antagonism.

c. The District Court Plan would not assure neigh

borhood support of schools. It would alienate that sup

port.

d. The District Court Plan would offer no opportunity

for any school in the district to demonstrate the achieve

ment of peace and better education by cooperative effort.

There would be only heavily dominant black schools.

There would be no proof of satisfactory cooperation

between blacks and whites in a district school. There

would be no real working together on even terms.

e. The District Court Plan would not deter the move

ment of students to private schools. In fact it would

accelerate and stimulate that movement, as experience

has shown (See Tables I & II, App. E). Such a continued

movement of white students to private schools will

greatly intensify racial and class animosities.

f. The District Court Plan has no aspect of perma

nence. Rather, it has an open and plain aspect of a tem

porary unrealistic expedient.

This Court said on April 20, 1971, in Davis v. Board of

School Commissioners of Mobile County, 402 U.S. 33

at 37.

“The measure of any desegregation plan is its effec

tiveness.”

33

When so measured, the District Court plan is proved in

effective. We point to the actual experience.

We compare below the enrollment record in the Halifax

County School District for the school year immediately preced

ing the August 26, 1969 District Court temporary injunction

with the enrollment of 1971. The figures for 1968-69 are

taken from the Overman deposition, (App. 219-220), and

from plaintiff’s Exhibit #13 (App. 727-745). The figures

for October 1971 are taken from the Overman affidavit,

(App. 1153) (App. D). Both sets of figures reflect actual

enrollment.

ENROLLMENT IN HALIFAX COUNTY SCHOOL

DISTRICT 1968-69 AND OCTOBER 1971

White Black % Black

1968-69 2357 8196 77.7

1971-72 1255 7585 85.8

In that total Halifax County District the Black ratio rose

8.1 points in 26 months.

From that District, 1102 (46.7%) of the white pupils

had disappeared.

From that District, 611 (7%) of the black pupils had

disappeared.

The Petitioners center their attack on a geographical area

in the Southeastern portion of Halifax County winch they

call District I. They refer to it as the^^Sm ^B rfw ley at

tendance zone. In that smaller area, chosen for discussion

by the Petitioners, the flight experience of both white and

black pupils was much worse than in the district as a whole.

That is shown by the actual enrollment figures taken from

the Overman deposition and the Overman affidavit of

October 1971. Those figures are as follows:

34

ENROLLMENT IN THE SO-CALLED DISTRICT I

OF THE HALIFAX COUNTY SCHOOL

DISTRICT 1968-69 and OCTOBER 1971

White Black % Black

1968-69 786 2516 76.0

1971-72 322 2261 87.5 .

In that Southeastern section (so-called District I) of the

Halifax County School District the black ratio had risen

during the 26 months experience period by 11.5 points.

From that sub-district, 464 (59%) of the white pupils

had disappeared.

From that sub-district, 255 (10.1 % ) of the black pupils had

disappeared.

The white pupil disappearance in that sub-district was

45.7% greater than in the remaining Districts II and III,

namely a disappearance of 59% rather than 40.5%.

In that sub-district the black pupil disappearance was

60.3% greater than in the remaining Districts II and III,

namely a disappearance of 10.1% rather than 6.3%.

A substantial disappearance of the white pupils was pre

dictable. Such disappearance had been predicted as was shown

by the record in this case. In fact the District Court an

ticipated substantial disappearance but erroneously observed

that it could not give it consideration as a factor in a de

segregation plan.

• w " H

It was also predictable that the disappearance in the

immediate Scotland Neck area would be more severe than

in the remaining Halifax County District.

Experience has now added a factor which was not pre

dicted by any witness, that is, the substantial disappearance

35

of black pupils. That could be a very significant matter.

The fact that the black pupil disappearance was 60.3%

greater in the Scotland Neck area than in the remaining

Halifax County School District (consisting of Districts II

and III) plainly points to the influence of the injunction

on the black pupil disappearance. It must be true that the

black pupil disappearance was caused in large part by a

loss of confidence in the prospective quality of the education

under the court plan.

It seems clear that a prospective flight of both white and

black students is an element which must be considered in

fashioning a plan for the correction of the reluctance of

black and white pupils to exercise their freedom of choice.

VI.

REPLY TO SOME SPECIAL POINTS IN THE

BRIEFS OF PETITIONERS

The foregoing brief is the primary reply to briefs of the

petitioners. There are only a few special features to which

we reply additionally.

Petitioners deal with integration rather than desegrega

tion, with mixing rather than with dismantling an identified

remaining vestige of law imposed segregation. They seek

forced assignments by race, in order to remove “substantial

disproportion” in the racial composition of the several schools

in the district. They would make substantial racial dis

proportion between schools a condition which must be cor

rected, regardless of the natural racial composition of the

neighborhoods in which the schools are located. We under

stand the Swann decision to condemn such an objective.

We note in each brief for petitioners the strong emphasis

on what they call the pre-Brown Scotland Neck-Brawley Uni

ty. They argue that where law imposed segregation was

36

made easier by such unity (they call it disregard of lines)

that unity should be continued in the desegregating process.

It would seem that precisely the contrary should be sought.

The best way to uproot the racial reluctance fostered by the

old Scotland Neck-Brawley “unity” is to dismantle that unity

“root and branch”. The Scotland Neck Statute severs all

unity with Brawley by adopting the natural residential lines

of the city limits. The Scotland Neck black and white students

would be held in the Scotland Neck school. The petitioners’

plan would force about half of the Scotland Neck black

pupils and nearly all of the Scotland Neck white pupils into

the Brawley school. Such perpetration of the Scotland Neck-

Brawley “unity operation” would increase rather than abate

racial discord.

Petitioners speak of the “hole in the doughnut”, even

though there is such a situation wherever there are city

schools and county schools. Surely the division between

municipal and rural schools is not of itself discriminatory.

Petitioners’ briefs refer again and again to the Scotland

Neck plan as creative of a “dominant white majority”. That

is a misuse of that word dominant. As a matter of fact the

realistic prediction for the Scotland Neck plan is a practically

even division between blacks and whites. However, even if

there should be a 57% white resultant proportion that would

be a majority but surely not a dominant one. To dominate

means to rule, to govern. Domination could and probably

would be achieved by a 80% racial ratio. Surely 57% school

pupils could not be called dominant.

Again and again the briefs of petitioners speak of the

creation of the Scotland Neck District as a secession. We

do not see fit to answer that mischievous charge. We do

deplore it as not being conducive to an atmosphere which

must be sought if the turmoil in our schools is to be resolved.

We note the argument made by petitioners that the statute

invites whites to move into Scotland Neck. We had under

37

stood the Swann decision to refuse to consider speculation as

to future residential patterns. However, it is clear that it

would be the strong objective of the defendant Scotland

Neck City Board of Education and of the community of

Scotland Neck to achieve such a high quality school that it

would attract new residents to the city, blacks and whites;,

and not only from the County of Halifax but from abroad.

It is possible, even probable, that the Scotland Neck school

operation would attract as many new black residents as new

white residents.

CONCLUSION

The most significant feature of this case is this: starting

with the promotion of the Statute and running through its

enactment, through the December 1969 announced plan of

the Scotland Neck City Board of Education, through portions

of the opinion of the District Court, and through the opinion

of the majority of the Court of Appeals, there is a current

of concern about the quality of education in the public

schools. A definite part of that concern for quality education

is anxiety about the prospective flight of white students to

the private schools and the consequent impairment of public

education.

Those concerns carry with them the hopeful thought that

the public and the courts are now recognizing that the dis

mantling of remaining vestiges of law imposed segregation

is a matter in which whites as well as blacks have a vital

interest and that both will be considered in the planning

of schools for all of our children.

The next moslt important feature of this case is the en

visioned potential of achieving federal, state and local co

operation in the process of providing interim corrective

measures for the dismantling of the racial reluctance to

exercise freedom of choice.

Without that hope and without that potential of coopera

38

^ j ip F tu c tr T,it. b ortion the path ahead would look very dtfAmnt. For the

foregoing reasons, the judgment of the Court of Appeals

should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted.

C. K itc h in J osey

Scotland Neck, North Carolina

W illiam T. J oyner

Joyner & Howison

Box 109

Raleigh, North Carolina 27602

Attorneys for Respondent Scotland

Neck City Board of Education

Hon. R obert M organ

Attorney General

Hon. Ra lph M oody

Deputy Attorney General

Raleigh, North Carolina

On Behalf of Respondent State of

North Carolina

A P P E N D I X

39

FIRST FURTHER ANSWER OF DEFENDANT

SCOTLAND NECK CITY BOARD OF EDUCATION1

8. It is the present intention of this Defendant, and this

Defendant makes this continuing representation, that, if and

when there is removed the temporary injunction barrier pre

venting operation under the Statute, Defendant will confine

its student body to those students residing within the geo

graphical limits of the town of Scotland Neck, plus or minus

such student transfers as may be in conformity to the law

and/or Court order or orders applicable to Defendant, and

in conformity to a plan of limitation of transfers to be pre

pared by Defendant and submitted to this Court.

WHEREFORE, this Defendant respectfully prays that:

1. The Court declare to be constitutional Chapter 31 of

the 1969 Session Laws of North Carolina;

2. The Court dissolve the temporary injunction hereto

fore issued in this cause on the 25th day of August, 1969;

3. The Court retain jurisdiction of this cause for the

receipt of a plan of transfer to be submitted by the De

fendant to the Court and for the hearing of any objection

that may be filed thereto.

APPENDIX A

C. Kitchin Josey

William T. Joyner

Walton K. Joyner

Attorneys for the defendant,

Scotland Neck City Board of

Education, a body corporate.

JT a k e n f ro m A pp. 796.

40

ADVERTISEMENT APPEARING IN SCOTLAND

NECK COMMONWEALTH

October 10, 1969

Defendant’s Exhibit #4

THE SCOTLAND NECK CITY BOARD OF EDU

CATION REQUESTS FINANCIAL AID IN

DEFENDING ITS POSITION IN COURT

We are defendants in a lawsuit which seeks to destroy

our Board. Under order of the Federal Court we may not

use any public funds for the conduct of our defense. We

are here requesting from the citizens of Scotland Neck

donations of money for the conduct of our defense in the

Court case and to refund tuition fees.

We shall state here facts of interest to you.

THE PRESENT POSTURE OF OUR LAWSUIT

On the 3rd day of March, 1969, the Legislature of

North Carolina responded to the expressed desires of the

people of Scotland Neck for a special school district and

a special school tax to permit achievement of better schools.

The Legislature created a special school district confined

to the boundaries of the City of Scotland Neck and to be

come effective only if and when the people of Scotland

Neck approved the formation of the special district and

the special tax of 50 cents on the $100.00 of property

valuation in the City.

On April 8, 1969, in a special election the people voted

for both the special district and the special tax.

This Board was formed and engaged a superintendent

APPEN D IX B

41

of schools and an expanded staff of teachers and made

plans for the conduct of schools which, because of the

availability of special funds, promised to be better than

the schools heretofore afforded to the City.

On Saturday, August 16, 1969, our Board was notified

that it had been made a party to a suit then pending in

the Federal District Court before Judge John D. Larkins,

Jr. That suit was brought by the Department of Justice

of the United States on behalf of the United States. The

suit challenged the constitutionality of the Statute under

which our school board was created and expected to oper

ate.

Preliminary the suit sought a temporary stay of all of

our operations until there could be a final determination of

the merits of the case. On August 21, 22, and 23, 1969, a

hearing was held on the temporary injunction, together with

a Warrenton School case and a Littleton School case before

Judges Algernon L. Butler and John D. Larkins, Jr.

On Monday, August 25, 1969, both judges entered or

ders granting the temporary restraining order sought by the

plaintiff, but did not rule on the constitutionality of the

Statute. The order in our case restored the status which had

existed prior to the adoption of the Statute, suspending the

effectiveness of the Statute until the case could be finally

determined on its merits. Precisely the order in our case said

“that the defendant Scotland Neck City Board of Education

and its officers, agents, employees and successors are hereby

enjoined from giving any force or effect to the provisions

of Chapter 31 and from taking any action pursuant to the

provisions of Chapter 31 pending a final determination on

the merits of the issues raised in the present action; . . .”

Under the interpretation by the court we may not use any

public funds, not even the proceeds of the special tax, for

the defense of our case. However, we are permitted to de

42

fend the case with funds contributed by individuals for that

purpose.

So, we are here asking for contributions for our defense.

There is contemplated a defense in the trial yet to be held

before the Federal District Court. If we lose there, it is con

templated that we would appeal the case to the Circuit

Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. If we lost there,

it is contemplated that we will appeal the case to the Su

preme Court of the United States. We are convinced that