Davis v. Mobile County Board of School Commissioners Motion to Advance and Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Davis v. Mobile County Board of School Commissioners Motion to Advance and Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1970. a4b1001c-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0d403f11-466f-4a79-97b7-7683df9662e0/davis-v-mobile-county-board-of-school-commissioners-motion-to-advance-and-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

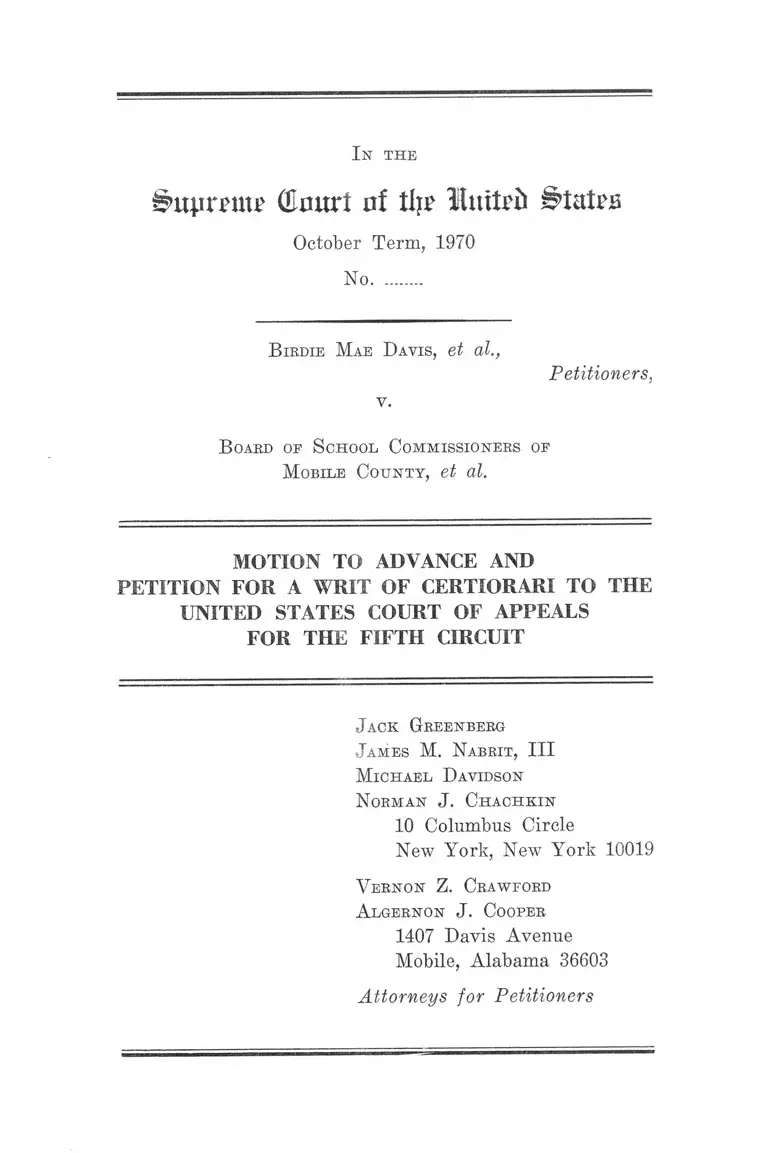

I n the

CUouri of tljp ^tatrs

October Term, 1970

No..........

B irdie M ae D avis, et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

B oard oe S chool C ommissioners oe

M obile C o u nty , et al.

MOTION TO ADVANCE AND

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

M ichael D avidson

N orman J. Ch a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

V ernon Z. Crawford

A lgernon J. Cooper

1407 Davis Avenue

Mobile, Alabama 36603

Attorneys for Petitioners

Opinions Below

Jurisdiction ....

I N D E X

PAGE

1

2

Question Presented ..................................-.................. ..... 2

Constitutional Provision Involved ------- ------ - ..... -....... - 3

Statement:

1. A Brief Overview of the School System.... - .... 3

2. Summary of Proceedings in the Courts Below 4

3. The Techniques of Segregation —..................... 12

Reasons for Granting the W rit:

I. The Decision Below Conflicts With Rulings

Both of This Court Since Brown and of Other

Courts of Appeals. It Absolves School Boards

of Responsibility to Provide Equal Educational

Opportunity to Black Students Contained in

Segregated Schools by “Neighborhood Resi

dential Patterns” Which Are Themselves the

Result of State Action Combined With Private

Discrimination ....................................................... 15

II. This Court Should Grant Certiorari in Order

to Insure Petitioners’ Due Process Right to an

Evidentiary Hearing in the District Court .... . 28

Conclusion 31

11

Appendix :

Order of District Court of January 31, 1970 ........ . la

Opinion of Court of Appeals dated June 8, 1970 .... 8a

Judgment of Court of Appeals dated June 8, 1970 2-3a

Orders of Court of Appeals on Rehearing dated

June 29, 1970 ......... ....... ........................................ 25a

Orders of Court of Appeals Denying Rehearing

dated June 29, 1970 ................................................. 26a

Tables of Cases:

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396

U.S. 19 (1969) .........................................................17,27,30

Anthony v. Marshall County Board of Education, 419

F.2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1969), rev’d on other grounds,

sub. nom, Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School

Board, 396 U.S. 290 (1970) ........ ..... ............................ 16

Bradley v. Board of Public Instruction of Pinellas

County, No. 28639 (5th Cir., July 1, 1970) _______16,29

Brewer v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 397 F.2d

37 (4th Cir. 1968) ............................. ........................-21, 24

Brewer v. School Board of City of Norfolk, No. 14,544

(4th Cir., June 22, 1970), cert, denied, 38 U.S.L.W.

3522 (June 29, 1970) ......... ........ ............................... 15,25

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).... 15

Calhoun v. Cook, Civ. No. 6298 (N.D. Gra., Feb. 19,

1970) ..................................... .............. .......... .................. 16

Calhoun v. Latimer, 377 U.S. 263 (1964) ..................... . 15

Carr v. Montgomery County Board of Education, No.

29521 (5th Cir., June 29, 1970) .................... ............. 16

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board, 396

U.S. 290 (1970) ..........................................1,4,6,17,19,29

Clark v. Board of Education of the Little Rock School

District, No. 19,795 (8th Cir., May 13, 1970) ............. 23

PAGE

I ll

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) .............................. 15

Crawford v. Board of Education of City of Los

Angeles, No. 822-854 (Super. Ct. Cal., February 11,

1970) ..... -...... .................................................................... 25

PAGE

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, 414 F.2d 609 (5th Cir. 1969) ................... -12, 28

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, 364 F.2d 896 (5th Cir. 1966) ...............-.... . 17

Davis v. School District of City of Pontiac, 309 F.

Supp. 734 (E.D. Mich. 1970) ......... ..... ....................... 25

Dove v. Parham, 282 F.2d 256 (8th Cir. 1960) ........... . 15

Ellis v. Board of Public Instruction of Orange County,

Florida, 423 F.2d 203 (5th Cir. 1970) ...........10,16,19, 25

Gross v. Board of Education of Knoxville, 373 U.S. 683

(1963) 15, 20

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968) ..................... -......... -.... -.15,16,19,21

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer & Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1969).... 21

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction of Hills

borough County, No. 28,643 (5th Cir., May 11,

1970) ....... ......... ......... -...... -----..................................... ..10,16

McFerren v. Fayette County Board of Education, Civ.

No. C-65-136 (W.D. Tenn., December 24, 1969) ....... 16

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of Jackson, No.

19720 (6th Cir., June 19, 1970) ...............-..................

Northcross v. Board of Education of Memphis, 397

U.S. 232 (1970) ................................-............................

Ross v. Eckels, Civ. No. 10,444 (S.D. Tex., June 1,

1970) ...................... -......................................................... 16

IV

PAGE

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, No. 26285 (5th Cir., Jan. 15, 1970) ....... ............. 29

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 419 F.2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1969) ....................... 1, 6

Spangler v. Pasadena City Board of Education, Civ.

No. 64-1438-R (C.D. Cal., March 12, 1970) ............... 25

Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Educa

tion, 333 F.2d 55 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 379 U.S.

933 (1964) ........................... ............ ...................... .......... 15

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

No. 281, O.T. 1970, cert, granted, June 29, 1970, 38

U.S.L.W. 3522 ................................................................ 25

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

300 F. Supp. 1358 (W.D. N.C. 1969) ...................20,24,31

United States v. Lincoln County Board of Education,

301 F. Supp. 1024 (S.D. Ga. 1969) ............................. . 16

Valley v. Rapides Parish School Board, Civ. No. 10,946

(W.D. La., July 5, 1970) ........................... .................. 16

Statutes:

Fair Housing Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C.A. §§ 3601 et seq. 21

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) ............................................................ 2

Other Authorities:

Abrams, Forbidden Neighbors (1955) .......................... 21

Racial Isolation in the Public Schools, A Report of the

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights (1967) .................. 21

Weaver, The Negro Ghetto (1948) ................................ 21

Weinberg, Race and Place—A Legal History of the

Neighborhood School (U.S. Gov’t Printing Office,

Catalogue No. FS 5.238:38005, 1967) ........................ 19

I n the

(Emtrt nf Hit United States

O ctober T erm 1970

No..........

B irdie M ae D avis, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

B oard oe S chool C ommissioners oe

M obile C ou nty , et al.

MOTION TO ADVANCE

Petitioners, by their undersigned counsel, respectfully

move that the Court advance its consideration and disposi

tion of this case, which presents issues of national im

portance about which the court below and other United

States Courts of Appeals are divided in their interpretation

of Green v. County School Bel. of New Kent County, 391

U.S. 430 (1968), Alexander v. Holmes County Bd of Educ.,

396 U.S. 19 (1969) and Carter v. West Feliciana Parish

School Bd., 396 U.S. 296 (1970). These issues require

prompt resolution by this Court for the reasons stated in

the annexed Petition for Writ of Certiorari.

W herefore, petitioners pray that the Court:

1. Consider this motion immediately;

2. shorten the time for filing respondents’ response to

the annexed petition and

2

3. consider the annexed petition at the Court’s earliest

possible opportunity.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J am es M. N abbit, III

N orman J. C h a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

V ernon Z. Crawford

A lgernon J. Cooper

1407 Davis Avenue

Mobile, Alabama 36603

Attorneys for Petitioners

I n the

i§>ttprm£ Glmtrt of tip Htufrfc States

October Term, 1970

No..........

B irdie M ae D avis, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

B oard of S chool Commissioners of

M obile C o u nty , et al.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit, entered in the above entitled case on

June 8, 1970. Petition for rehearing was denied June 29,

1970.

Opinions Below

The opinions of the courts below directly preceding this

petition1 are as follows:

1 Earlier proceedings in this case are reported as Davis v. Board

of School Comm’rs of Mobile County, 318 F.'2d 63 (5th Cir. 1963);

J^322 F.2d 356 (5th Cir.), stay denied, 11 L.Ed.2d 26 (Mr. Justice

Black, Circuit Justice), cert, denied, 375 U.S. 894 (1963), rehear

ing denied, 376 U.S. 898 (1964) ;L333 F.2d 53 (5th Cir.), cert, de

nied, 379 U.S. 844 (1964) ;(364 F.2d 896 (5th Cir. 1966) ; 393 F.2d _ ^

690 (5th Cir. 1968); 414 F.2d 609 (5th Cir. 1969); sub mina.

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dist., 421 F.2d

1211 (5th Cir.), interim relief ordered, 38 U.S.L.W. 3220 (1969),

rev’d sub nom. Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd., 396

U.S. 290 (1970).

2

1. Opinion and order of the District Court filed Janu

ary 31, 1970, unreported (la-7a).

2. Opinion of the Court of Appeals filed June 8, 1970,

not yet reported (8a-22a).

3. The judgment of the Court of Appeals (23a-24a).

4. Orders of the Court of Appeals on the petition for

rehearing (8a-22a).

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

June 8, 1970 (24a). The jurisdiction of this Court is in

voked under 28 U.S.C. §1254(1).

Question Presented

Upon request from the courts below, the United States

Department of Health, Education, and Welfare developed

several plans to desegregate public schools in Mobile

County, Alabama. One plan integrated each school in the

system by establishing a number of school pairings and

clusters which necessitate the incidental transportation of

both black and white students. This technique of student

assignment—the use of school attendance zones with non

contiguous parts and the transportation of students—had

long been used in the Mobile school system to maintain

segregated schools. In spite of this history and without

any evidentiary hearing in the District Court, the Court

of Appeals rejected this H.E.W. plan and ordered the

implementation of a plan which leaves 7,725 black students

in eight all-black schools. The rejection of the H.E.W.

plan was based solely on the Court’s deference to a hypo

thetical “neighborhood school concept” (13a) which Mobile

had not theretofore had.

3

The fundamental question presented to this Court is

whether black students are denied the equal protection of

the laws when they continue to be assigned to segregated

black schools despite the availability of an alternative

method of student assignment which would desegregate

every school in the system and which is proved feasible

by the school board’s past use of the same assignment

techniques.

Constitutional Provision Involved

This case involves the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

Statement

1. A Brief Overview of the School System.

Mobile has a combined rural and metropolitan school

system serving the whole of Mobile County. It is the

largest school system in Alabama; 91 schools in the sys

tem served 73,504 students during 1969-70. The total

number of white students is 42,620, or 58% of all students,

and the total number of black students is 30,884, or 42%

of all students.

Throughout the litigation to desegregate Mobile’s schools,

the rural and metropolitan portions of the system have

been treated separately. Since September 1969 the rural

portion of the system has been desegregated adequately

and this petition concerns only the metropolitan area com

prised of the contiguous cities of Mobile, Pritchard and

Chickasaw. Within the metropolitan area there are 65

schools serving 54,913 students, of whom 27,769 or 50.5%

are white and 27,144 or 49.5% are black.

4

In addition to the rural-metropolitan division, another

division has more recently been advanced in this litigation.

This newer division is between the eastern and western

parts of the metropolitan area with Interstate Highway

1-65 used as a north-south divider. The western part is

predominantly white with 17 schools serving 13,875 stu

dents, of whom 12,172 or 88% are white and 1,703 or

12% are black. The eastern part is majority black with

48 schools serving 41,038 students, of whom 15,597 or

38% are white and 25,441 or 62% are black.

The controversy which led to this Court’s decision in

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board, 396 U.S.

290 (1970), concerned the decisions of the courts below

to treat separately the predominantly white and majority

black parts of metropolitan Mobile by permitting the for

mulation of separate plans for each, and to delay desegre

gating the majority-black part until 1970-71. It is the

continuing effort by the school board and the courts below

to subdivide the metropolitan area which necessitates action

by this Court.

2. Summary of Proceedings in the Courts Below.

This action by black parents and students to desegregate

Mobile County’s public schools began in 1963. The United

States intervened in 1967 and successive groups of white

parents intervened in 1968 and earlier this year. The cur

rent phase of this litigation began with the Court of Ap

peals’ June 3, 1969 decision.

The main issue before the Court of Appeals at that time

was whether the School Board and the District Court had

complied with a previous decision of the Court of Ap

peals2 by establishing school attendance zones for elemen-

2 The June 3, 1969 decision is reported at 414 F.2d 609; the

previous decision is reported at 393 F.2d 690.

5

tary and junior high schools, and maintaining freedom of

choice for high school students in metropolitan Mobile.

A second issue was retention of freedom of choice for all

students in rural Mobile County. The Court of Appeals

found that the District Court had “ignored the unequivocal

directive to make a conscious effort in locating attendance

zones to desegregate and eliminate past segregation.”

414 F.2d at 611. Freedom of choice in metropolitan high

schools and all rural schools was also held to be unac

ceptable. Accordingly, the Court of Appeals ordered the

prompt formulation of a plan “to fully and affirmatively

desegregate all public schools in Mobile County, urban

and rural . . and directed the District Court to request

the Office of Education of the United States Department

of Health, Education, and Welfare to collaborate with the

School Board and submit its own desegregation plan if

agreement with the Board was not possible. Ibid.

H.E.W. and the School Board could not agree on a plan

and H.E.W. submitted its own county-wide desegregation

plan on July 10, 1969. The plan provided for zoning all

schools in rural and metropolitan Mobile (some schools

would be paired within zones), closing four black schools

in eastern Mobile, and transporting 2,000 black students

from the closed schools to white schools in the western

and southern parts of the metropolitan area. Petitioners

sought implementation of the plan with amendments to

correct two deficiencies: (1) the plan retained five large

all-black elementary schools serving 5,500 students because

H.E.W. was unwilling to recommend the transportation

of white students in addition to the transportation of

black students; and (2) the plan deferred desegregation

in eastern metropolitan Mobile, where 85% of the system’s

black students live, until 1970-71. On August 1, 1969, with

out a hearing, the District Court ordered the implemen-

6

tation of H.E.W.’s plan for rural and western metropoli

tan Mobile, as modified by the Court to eliminate the

H.E.W. proposal to transport 2,000 black students from

eastern to western metropolitan Mobile. The District Court

did accept H.E.W.’s plan to defer desegregation in eastern

metropolitan Mobile until 1970-71.

Petitioners appealed the delay, the Court of Appeals

affirmed,3 Mr. Justice Black ordered the School Board to

prepare for desegregation by February 1, 1970,4 * and this

Court reversed the delay.6 The case returned to the Dis

trict Court in late January 1970 for second semester im

plementation of a plan to complete the desegregation of

Mobile’s schools.

In the meanwhile, H.E.W. had submitted two additional

plans to the District Court on December 1, 1969.6 Using

the July 10, 1969 plan as a base (and labelling it Plan B),

H.E.W. proposed one modification (Plan B Alternative)

which totally eliminated the transportation of students

by continuing in operation the four black schools which

the July, 1969 plan closed. Plan B Alternative would

leave nine all-black schools serving 7,971 students (15a).

The second modification (Plan B-l Alternative) recom

mended closing two black schools, and pairing or clustering

all other black schools in eastern Mobile with white school

in western or southern Mobile. Transportation of both

3 Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District, 419

F.2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1969).

4 38 TJ.S.L.W. 3220 (1969).

6 Garter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board, 396 U.S. 290

(1970).

6 These additional H.E.W. plans were submitted in accordance

with the District Court’s August 1, 1969 decision which established

December 1, 1969 as the time for submitting plans for the 1970-71

school year.

7

black and white students would be required and all schools

in the system would be integrated (Ibid.).7

The same day, the School Board submitted its own plan

for eastern Mobile. It assigned 18,832 black students to

21 all or nearly all black schools.8

The District Court called attorneys for all parties to a

“pre-trial conference” in chambers on January 23, 1970

(2a). At the conference the following positions were taken:

(1) petitioners contended that the elementary school pro

visions of H.E.W.’s Plan B-l Alternative and the junior

and senior high school provisions of H.E.W.’s Plan B

should be implemented forthwith, but if the transportation

proposals made immediate relief impossible and the Dis

trict Court selected another plan pendente lite, then a

hearing should be promptly set to determine a permanent

plan; (2) the United States proposed that the H.E.W.

plan involving no transportation (Plan B Alternative) be

implemented pendente lite while discovery and hearings on

a permanent plan proceeded; (3) the School Board argued

against any changes in its operations; and (4) the District

Court stated it would not consider the plans petitioners

supported and that the School Board’s December 1, 1969

plan was unacceptable without modifications.

The District Court concluded the conference by asking

the School Board for modification of its December 1, 1969

plan and the United States “ for [a] revision of the H.E.W.

plan which the government thought should be followed

for the remainder of the present school year” (2a). The

7 Plan B-l Alternative involved only elementary schools. For

junior and senior high schools it proposed to incorporate the pro

visions of Plan B.

8 Petitioners, despite repeated requests, were not served with a

copy of the Board’s plan and had to move on January 2, 1970 for

an order compelling service which was not made until the District

Court granted the motion February 27, 1970.

8

School Board failed to respond to the court’s request.9 The

United States submitted a revision of H.E.W.’s no-trans

portation alternative (Plan B Alternative) “as a plan

which could be implemented immediately to remain in

effect only for the present school year.” 10 Then, despite

its own characterization of the January 23 conference as

a “pretrial conference” and both petitioners’ and the United

States’ clearly stated position that plaintiffs sought only

mid-year relief pending hearings on a permanent deseg

regation plan, the District Court without an evidentiary

hearing entered an order on January 31, 1970 which pur

ported to finally disestablish the dual system in Mobile

(la-7a).

Mindless of its expressed view at the January 23, 1970

conference that the Board’s proposals were unacceptable,

the District Court’s order adopted the School Board’s De

cember 1, 1969 plan with only several modifications. The

order left 18,623 black students, or 60% of the system’s

black students, in IS all- or nearly all-black schools (18a-

22a). The court dismissed H.E.W.’s Plan B-l Alternative,

which would establish pairings and clusters of non-con-

tiguous zones and require transporttion of students, by

making the general observation that it “would require

busing of children from areas of the city to a different

and unfamiliar area” (3a) and by singling out one11 of

9 In its January 31, 1970 order the District Court commented

on the Board’s failure:

“ The school board and its staff of administrators and profes

sional educators, who know the Mobile Public School System

best, who have all the facts and figures which are absolutely

necessary for a meaningful plan, have not assisted or aided

the Court voluntarily. Consequently, the plan which is by

this decree being ordered is not perfect . . (2a-3a).

10 Brief for the United States in the Court of Appeals, p. 22.

11 The one elementary arrangement which the court singled out

involved three schools, two white and one black, in a cluster. All

9

the sixteen H.E.W. proposed pairs or clusters, presumably

to illustrate the court’s conclusion that H .E W .’s proposal

was “motivated for the sole purpose of achieving racial

balance” (4a). Similarly, the court dismissed H.E.W.’s

Plan B for junior high schools by citing but one atypical

proposal to establish a cluster of three junior high schools,

stating that in the court’s view “the Supreme Court has

not held that such drastic techniques are mandatory for

the sole purpose of achieving racial balance” (4a).

Petitioners, the United States, and the School Board

appealed. Petitioners challenged both the failure of the

District Court to conduct an evidentiary hearing before

ordering a final plan and the court’s failure to require the

School Board to implement H.E.W.’s plan to establish non

contiguous pairings and clustering and transport both

black and white students to achieve complete desegregation.

The United States, while acknowledging that the School

Board’s past practices indicate that any of H.E.W.’s plans

would be feasible, asked the Court of Appeals to require

the implementation of H.E.W.’s sole no-transportation plan

for the negative reason that “no argument can be made

that plan B Alternative, which is the most modest plan,

students in the cluster would attend one of the white schools for

the first and second grades, the second white school for the third

grade, and the black school for grades four through six (4a). Of

the remaining fifteen elementary school arrangements in H.E.W.’s

Plan B-l Alternative, only one other was similar. Eleven involved

only two schools with all students attending either the black or

white schools for two or three years and then attending the other

school for the remaining elementary school grades. Three other

arrangements involved three schools but required attendance at

only two schools. Under these arrangements all students: in the

cluster would attend one school for grades one and two and then

divide, with one-half attending the second school in the cluster

for grades three through five and the other half attending the third

school for the same grades. Neither the simple pairing of two

schools serving non-eontiguous black and white zones nor this latter

type of clustering were discussed by the District Court.

10

is either educationally unsound or administratively in

feasible.” 12 The School Board, although cross appealing,

sought affirmance of the District Court’s order.

The Court of Appeals, after remanding for further find

ings of fact,13 decided the appeal on June 8, 1970. The

court defined its judicial task in these words:

We have examined each of the plans presented to

the district court in an effort to determine which would

go further toward eliminating all Negro or virtually

all Negro student body schools while at the same time

maintaining the neighborhood school concept of the

school system (13a).

In the court’s view the neighborhood assignment system

allows two alternatives. One alternative requires the as

signment of each student to the school nearest his home

with such assignments limited only by the capacity of the

schools. Ellis v. Board of Public Instruction of Orange

County, Florida, 423 F.2d 203, 207 (5th Cir. 1970). The

other alternative is the establishment of attendance zones

“ on a discretionary basis as distinguished from a strict

neighborhood assignment. . . . ” Mannings v. Board of

Public Instruction of Hillsborough County, Florida, No.

28643 (5th Cir., May 11, 1970) (Slip Op., p. 6). Mobile, the

12 Brief for the United States in the Court of Appeals, p. 47.

13 The remand was required by the District Court’s failure to

determine how the School Board’s plan, which it adopted, would

affect the racial composition of any of the system’s schools. The

remand also directed the District Court to make findings on the

extent of desegregation of faculty, transportation and extracur

ricular activities. Petitioners moved in the District Court on

April 6, 1970 to establish a procedure whereby after the Board

submitted proposed findings of fact an evidentiary hearing would

be held. The School Board submitted an affidavit which the Dis

trict Court accepted in toto “ excluding self-serving declarations

and speculative opinions.” Order of April 14, 1970. Petitioners’

motion for a hearing was denied the same day.

11

court concluded, had itself chosen not to use “the strict

neighborhood assignment system” but instead uses “discre

tionary zones lines” (13a). As Mobile had made that deci

sion for itself, the Court ruled that the desegregation plan

“can be greatly improved by pairing some schools located

in proximity to each other . . . [and] also be improved by

recasting the grade structure in some of the buildings but,

at the same time, maintaining the neighborhood school

concept” (Ibid.).

The plan which found favor with the court was the

plan submitted by the United States as a modification of

H.E.W.’s no-transportation Plan B Alternative. The plan

left 8,515 black students in all-or nearly all-black schools

(Ibid.) ; the court required modifications of the plan to

reduce the number of black students in all-black schools to

7,725 students in 8 elementary schools, which it noted

amounted to 25% of Mobile’s black students being assigned

to all-black schools (24a). In terms of elementary school

students in metropolitan Mobile, the plan results in the

assignment of 58% of black elementary school students

to all-black schools.

These results were justified by the court in four ways:

(1) “ every Negro child would attend an integrated school

at some time during his education career” (13a); (2) “ the

all Negro student body schools which will be left after the

implementation of the Department of Justice plan, as

modified, are the result of neighborhood patterns” (15a-

16a); (3) the remaining segregation can be “alleviated”

through a policy allowing black students to transfer to

white schools with transportation provided (16a); and (4)

the situation may be further alleviated by the establish

ment of a bi-racial committee to serve in an “ advisory

capacity” to the School Board (Ibid).

12

The Court of Appeals remanded the case to the District

Court with instructions to implement a new plan by July 1,

1970. On remand the District Court ordered the implemen

tation of the plan submitted by the United States except

for amendments to two school districts which the Court

will make.

3. The Techniques of Segregation.

Although the District Court has not permitted any evi

dentiary hearings on a desegregation plan since the sum

mer of 1968, the record of the extensive hearing that sum

mer and in previous years fully documents the various

techniques used by the School Board to segregate Mobile’s

schools.14

a. Grade Structures. The Mobile school system has used

an extraordinarily wide variety of grade structures, in

cluding schools serving grades 1-5, 1-6, 1-7, 1-8, 1-9, 1-12,

2-5, 6-7, 6-8, 6-9, 6-10, 6-12, 7, 7-8, 7-9, 7-11, 7-12, 8-12,

9-12, 10-11, 10-12. By selectively decreasing or increasing

the number of grades served at particular schools, the

School Board has increased or decreased the area served

by the school to coincide with racial residential patterns

(R- 26,886 Vol. V, pp. 1527-1534). For example, the

School Board established the Hillsdale School as the only

metropolitan school serving grades 1-12 in order to restrict

its attendance area to a small black community in the

western part of the metropolitan area. In downtown Mo

bile, the School Board between 1962 and 1967 candidly re

organized grade structures, and assigned portables and

closed schools, to maintain segregated schools in the face

of rapidly shifting racial residency patterns (R. 26,886

14 This portion of the petition is a summary of a longer analysis

of these techniques contained in the Brief for the United States

in the Court of Appeals, pp. 4-18. Citations to R. 26,886 axe to the

record before the Court of Appeals in Davis v. Board of School

Commissioners of Mobile County, 414 F.2d 609 (5th Cir. 1969).

13

Yol. VI, pp. 25-35). School segregation was also the ob

jective in arranging grade structures at four white schools

surrounding a black school in northern metropolitan Mo

bile to enable white students to attend one white school for

grade 6, a second for grades 7 and 8, a third for grade 9,

and a fourth for grade 10, all in order to prevent their

attendance at a nearby black school (R. 26,886 Vol. IV, pp.

1331-32).

b. Zones. The splitting of school attendance zones (i.e.,

non-contiguous zones) has been a common method of school

assignment in Mobile. As many as nineteen non-contiguous

zones were used in one year, 1964-65, including one split

zone in which the parts were separated by over 11 miles.15

Transportation between split zones was provided by the

School Board (R. 26,886 Vol. I, pp. 5-6).

c. Portable Classrooms. The selective assignment of

portable classrooms in order to expand the capacity of

black schools as a way of avoiding the assignment of black

students to under-utilized nearby white schools has been

a method of maintaining segregated schools (R. 26,886

Vol. I, pp. 90-93).

d. Transportation. Busing has not been limited to the

rural parts of the school system. During 1966-67 the School

Board bused 7,116 students daily in the metropolitan area.

Approximately 2,350 of these students were bused because

of non-contiguous zoning (R. 26,886 Vol. I, pp. 5-6) A

considerable amount of busing was designed to maintain

segregation. As an example, 582 black students were bused

over 6 miles from rural Saraland and Satsuma to a black

school in metropolitan Mobile to prevent integration at

white schools in their communities (Ibid).

15 The facts were culled from numerous exhibits and appear in

summary form in the Brief of the United States in the Court of

Appeals, pp. 7-9 and Appendix C.

14

e. Construction. New schools in Mobile have been lo

cated in order to serve only selected racial groups. For

example, although population movements in downtown Mo

bile left unused classrooms in white schools, the Board

embarked on a plan during the 1966-67 school year to

construct four schools for black students in order to avoid

the reassignment of blacks at overcrowded black schools

to available space at white schools (R. 26,886 Vol. VI, pp.

25-35). A few years earlier, in 1963, the School Board

sought to justify to this Court its failure to even begin

desegregation by pointing to its ongoing construction of

“colored schools.” Justice Black’s opinion in chambers

recited the Board’s contentions:

Yet this record fails to show that the Mobile Board

has made a single move of any kind looking towards

a constitutional public school system. Instead, the

Board in this case has rested on its insistence that

continuation of the segregated system is in the best

interests of the colored people and that desegregation

would “ seriously delay and possibly completely stop”

the Board’s building program “particularly the im

provement of and completion of sufficient colored

schools which are so urgently needed.” In recent years,

more than 50% of its building funds, the Board pointed

out to the parents and guardians of its colored pupils,

had been spent to “build and improve colored schools,”

and of eleven million dollars that would be spent in

1963, over seven million would be devoted to “colored

schools.”

It is quite apparent from these statements that Mobile

County’s program for the future of its public school

system “lends itself to perpetuation of segregation”

. . . Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, 11 L. Ed. 2d 26, 28 (1963)

15

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

The Decision Below Conflicts With Rulings Both of

This Court Since Brown and of Other Courts of Ap

peals. It Absolves School Boards of Responsibility to

Provide Equal Educational Opportunity to Black Stu

dents Contained in Segregated Schools by “ Neighbor

hood Residential Patterns” Which Are Themselves the

Result of Slate Action Combined With Private Discrimi

nation.

Since Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954), this

Court has consistently invalidated subterfuges by which

school districts have sought to maintain racially separate

and identifiable schools, whether such devices relied upon

school board or private initiative to produce the desired

result. E.g., Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) (delay

sought due to community opposition); Goss v. Board of

Educ. of Knoxville, 373 U.S. 683 (1963) (minority-to-

majority transfer allowing avoidance of integration);

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County, 391 U.S.

430 (1968) (free transfer plan permitting same result) ;

cf. Calhoun v. Latimer, 377 U.S. 263 (1964) (grade-a-year

desegregation). Lower courts have done the same. E.g.,

Dove v. Parham, 282 F.2d 256, 258 (8th Cir. 1960) (pupil

placement); Brewer v. School Bd. of City of Norfolk, No. 14,

544 (4th Cir., June 22, 1970) (en lane) (assignments based

on social class); Monroe v. Board of Comm’rs of Jackson,

No. 19720 (6th Cir., June 19, 1970) (same); Stell v.

Savannah-Chatham County Bd. of Educ., 333 F.2d 55, 62

(5th Cir.), cert, denied, 379 U.S. 933 (1964) (assignment

based on purported intelligence differences among races),

compare Anthony v. Marshall County Bd. of Educ., 419

16

F.2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1969), rev’d on other grounds sub nom.

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd., 396 U.S. 290

(1970) (assignment by achievement test scores); United

States v. Lincoln County Bd. of Educ., 301 F. Supp. 1024

(S.D. Ga. 1969) (same); McFerren v. Fayette County Bd.

of Educ., Civ. No. C-65-136 (W.D. Tenm, December 24,

1969) (sex segregation).

The progress so far been realized in converting dual

school systems into unitary ones from which all vestiges

of discrimination have been extirpated, Green v. County

School Bd. of New Kent County, supra, is severely jeopar

dized by the decision below and others like it which have

seized upon a justification for continued segregation in the

so-called “neighborhood school concept.” 16

This concept, whatever it means—imprecision is one of

its characteristics, compare Ellis v. Board of Public In

struction of Orange County, supra, with Mannings v. Board

of Public Instruction of Hillsborough County, supra—has

been advocated in the past as in the present by those seek

ing to preserve segregation. As former Chief Judge Tuttle

observed earlier in this very litigation, the “neighborhood

school is a euphemism for separation.”

Both in the testimony and in the briefs, much is said

by the appellees about the virtues of “neighborhood

schools.” Of course, in the brief of the Board of Educa

tion, the word “neighborhood” doesn’t mean what it

usually means. When spoken of as a means to require

Negro children to attend a Negro school in the vicinity

16 E.g., EUis v. Board of Public, Instruction of Orange County,

supra; Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction of Hillsborough

County, supra; Carr v. Montgomery County Bd. of Educ., No.

29521 (5th Cir., June 29, 1970) ; Bradley v. Board of Public In

struction of Pinellas County, No. 28639 (5th Cir., July 1, 1970) ;

Boss v. Eckels, Civ. No. 10,444 (S.D. Tex., June 1, 1970) ; Calhoun

v. Cook, Civ. No. 6298 (N.D. Ga., Feb. 19, 1970) ; Valley v. Rapides

Parish School Bd., Civ. No. 10,946 (W.D. La., July 5, 1970).

17

of their homes, it is spoken of as a “neighborhood”

school plan. When the plan permits a white child to

leave his Negro “neighborhood” to attend a white

school in another “neighborhood” it becomes apparent

that the “neighborhood” is something else again. As

every member of this court knows, there are neighbor

hoods in the South and in every city of the South

which contain both Negro and white people. So far as

has come to the attention of this court, no Board of

Education has yet suggested that every child be re

quired to attend his “neighborhood school” if the neigh

borhood school is a Negro school. Every board of edu

cation has claimed the right to assign every white child

to a school other than the neighborhood school under

such circumstances. And yet, when it is suggested that

Negro children in Negro neighborhoods be permitted

to break out of the segregated pattern of their own race

in order to avoid the “ inherently unequal” education of

“ separate educational facilities,” the answer too often

is that the children should attend their “neighborhood

school.”

So, too, there is a hollow sound to the superficially ap

pealing statement that school areas are designed by

observing safety factors such as highways, railroads,

streams, etc. No matter how many such barriers there

may be, none of them is so grave as to prevent the white

child whose “ area” school is Negro from crossing the

barrier and enrolling in the nearest white school even

though it be several intervening “areas” away.

Davis v. Board of School Comm’rs of Mobile

County, 364 F.2d 896, 901 (5th Cir. 1966).

It is only now, after the decisions of this Court in Alex

ander, Carter and Northeross have made unmistakable the

18

requirement of integration, that the “neighborhood school”

is offered as an inviolate principle of student assignment.

Like its predecessors—pupil placement and similar schemes

—its purpose is obvious: to provide a superficially neutral

gloss to the maintenance of racially separated schools.

Manipulating the “neighborhood school concept” today,

as many school boards seek to have it applied, and as the

Court of Appeals used it, means in almost every instance

(except in small, rural districts) that a significant segment

of a school district’s black student population will continue

to be assigned to all-black schools. This departure from the

clear mandates of this Court from Brown to Northcross is

offered as justifiable because of “neighborhood residential

patterns.”

Nowhere is this new rule more anomalous in result than

in Mobile. The district court had before it a number of

different desegregation plans for the Mobile school system,

submitted under court order because freedom of choice

had failed to change Mobile’s dual school system. Yet

neither the district court nor the Court of Appeals chose

the plan which would integrate every school and destroy

racial identifiability in the school system. Instead, both

courts left black students and white students alike in

segregated schools to preserve what they erroneously per

ceived to be Mobile’s “neighborhood school system.”

But we do not deal here, as Judge Tuttle recognized four

years ago, with a school system in which the neighborhood

school concept has a long, hallowed or neutral history.

Mobile never considered the neighborhood school concept

a bar to its efforts to prevent the attendance of black and

white students at the same schools. The extensive record

and prolonged proceedings in this case show that the pair

ing of non-contiguous attendance zones, the transportation

of students from one school zone to another, the closing

19

and conversion of schools, and the manipulation of grade

structures—techniques proposed by HEW to completely

dismantle Mobile’s dual system by desegregating every

school—were all established techniques of school adminis

tration when the objective was segregation.

This Court held in Green that school districts must con

sider proposed desegregation plans not in isolation and

abstraction but in “ light of any alternatives which may be

shown as feasible and more promising in their effective

ness.” 391 U.S. at 439. In Mobile, there is an alternative

plan to test the effectiveness of that approved below.17 The

appropriate allocation of burdens requires the School Board

to demonstrate its unworkability beyond question. That

task has not been undertaken because the Court of Appeals

saw fit to create, on its own, a new and absolute principle—

Under the neighborhood assignment basis in a unitary

system, the child must attend the nearest school whether

it be a formerly white school or a formerly Negro

school. Ellis v. Board of Public Instruction of Orange

County, 423 F.2d 203, 207 (5th Cir. 1970)

—and then excuse the board from burdens it must carry

under decisions of this Court. The fashioning by the Court

of Appeals of the neighborhood school concept in absolute

terms is as new a judicial invention as it is a principle of

school administration in Mobile.18 Invoking this concept

17 Where, as here, the alternative was formulated with the ex

pertise of the United States Department of Health, Education and

Welfare at the request of the district court, the “school districts are

to bear the burden of demonstrating beyond question, after a hear

ing, the unworkability of the proposals. . . . ” Carter v. West Feli

ciana Parish School Bd., 396 U.S. 290, 292 (1970) (concurring

opinion).

18 See generally, Weinberg, Race and Place—A Legal History of

the Neighborhood School (U.S. Gov’t Printing Office, Catalogue No.

FS 5.238:38005, 1967).

20

as an absolute bar to considering feasible alternatives in

a process which requires the examination of individual

circumstances of individual districts is plainly contrary to

the decisions of this Court.

The absoluteness of the neighborhood school concept

employed by the Court below cannot be overstated. Only

the pupil assignment techniques of contiguous single-school

zoning or contiguous pairing have been held permissible;

any segregated school remaining after these two techniques

have been exhausted is judicially sanctioned on the ground

that it results solely from “neighborhood residential pat

terns.” Yet the Court overlooks the vital role played by the

school system itself in creating and defining the “neighbor

hoods” which are now held to be beyond the pale of school

board corrective action. As Judge McMillan has said, re

ferring to Charlotte, “Putting a school in a particular loca

tion is the active force which creates a temporary com

munity of interest among those who at the moment have

children in that school,” Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Bel. of Educ., 300 F. Supp. 1358, 1369 (W.D.N.C. 1969)

(emphasis omitted). We have pointed out above that the

record in this case vividly demonstrates the degree to which

the Mobile school board has in the past been able to main

tain white and black school “ neighborhoods” through ma

nipulation of attendance boundaries, grade structures, port

able classroom placement and the pupil transportation

system.

Like the minority-to-majority transfer disapproved in

Goss v. Board of Educ. of Knoxville, supra, the “neighbor

hood school concept” permits private action which results

in the maintenance of segregated schools. To begin with,

there is a historic and pervasive pattern of housing segre

gation caused by discrimination against black people

throughout the Nation. In the past, the policy of discrimi-

21

nation received the blessing of the federal government.

Racial Isolation in the Public Schools, A Report of the U.S.

Commission on Civil Rights 254 (1967). See also, Abrams,

Forbidden Neighbors 233 (1955) and Weaver, The Negro

Ghetto 71-73 (1948). In 1968, recognition of the problem

led the United States to take affirmative steps to make

housing available to minorities with the passage of the

Fair Housing Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C.A. §§ 3601 et seq.

(Supp. 1970); see also, Jones v. Alfred II. Mayer & Co.,

392 U.S. 409 (1969). But even if active housing discrimina

tion were to cease, its residual effects persist. See Racial

Isolation in the Public Schools, supra, at 201-02, Legal Ap

pendix at 255-56.

Furthermore, the record in this case shows that the pres

ent residential patterns in Mobile result to a substantial

degree from discriminatory policies of the federal, state

and local governments. For example, there has been a close

relationship between the school board and the public hous

ing authorities in the Mobile area regarding location of

racially identifiable housing projects and the concommitant

nearby location of school facilities which have traditionally

been, and which continue to be racially identifiable. E.g.,

PI. Int. Ex. 87 (July 1967 hearing).

Making pupil assignment merely reflective of housing

patterns will therefore often but mirror community segre

gation and discrimination; it ignores the affirmative duty

of school boards formerly operating dual systems to bring

about integration. Green v. County School Bd. of New

Kent County, supra.

The Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit has recog

nized the problem. In Brewer v. School Bd. of City of

Norfolk, 397 F.2d 37, 41-42 (4th Cir. 1968), that Circuit

held that

2 2

Assignment of pupils to neighborhood schools is a

sound concept, but it cannot be approved if residence

in a neighborhood is denied to Negro pupils solely on

the ground of color.

Other Courts have likewise measured the “neighborhood

school concept” as a permissible desegregation device by

examining the alternatives available and the results of its

application.

The United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth

Circuit recently considered the mandates of this Court in

a challenge to Little Rock, Arkansas’s continuing failure

to desegregate its schools. At issue in this urban school

system was the acceptability of a geographic zoning plan

in light of several alternative plans involving the pairing

of schools and transportation of students. The Eighth

Circuit reviewed the results of Little Rock’s geographic

zoning plan against this statement of the law:

Thus, as of this date it is not enough that a scheme

for the correction of state sanctioned school segrega

tion is non-discriminatory on its face and in theory. It

must also prove effective. As the Court observed in

Green-.

“In the context of the state imposed pattern of long

standing, the fact that in 1965 the Board opened

the doors of the former ‘white’ school to Negro

children and of the ‘Negro’ school to white children

merely begins, not ends, our inquiry whether the

Board has taken steps adequate to call for the

dismantling of a well-entrenched dual system.”

391 U.S. at 437.

We believe that geographic attendance zones, just as

the Arkansas pupil placement statutes, “freedom of

choice” or any other means of pupil assignment must

23

be tested by this same standard. In certain instances

geographic zoning may be a satisfactory means of de

segregation. In others it alone may be deficient.

Always, however, it must be implemented so as to

promote desegregation rather than to reinforce segre

gation [citations omitted]. Clark v. Board of Educa

tion of the Little Rock School District, No. 19,795 (8th

Cir., May 13, 1970) (en banc) (Slip op., pp. 14-15).

Applying this test to the results of Little Rock’s geographic

zoning plan the Eighth Circuit found that the plan retained

racially identifiable schools in the face of at least one alter

native which would eliminate the racial identifiability at

several such schools. The court held that the record could

not sustain a holding that the geographical zoning plan

“ is the only ‘feasible’ means of assigning pupils to facilities

in the Little Rock School System” (Ibid.) and while declin

ing to decide on an absolute basis whether “geographical

zoning or the neighborhood school concept are in and of

themselves either constitutionally required or forbidden”

the Court held “that as employed in the plan now before

us they do not satisfy the constitutional obligations of the

District” (Id. at 19-20).

The Eighth Circuit also declined to establish an absolute

rule of transportation:

Lastly, we do not rule that busing is either required

or forbidden. As Judge Blackmun stated in Kemp III,

“Busing is only one possible tool in the implementation

of unitary schools. Busing may or may not be a useful

factor in the required and forthcoming solution of

the . . . problem which the District faces.”

Kemp III, the El Dorado, Arkansas school case, focused on

the feasibility of transportation as a technique of deseg

regation :

24

It may or may not be feasible to use it [busing], in

whole or in part, for Fairview-Watson-Murmil Heights

and it may or may not be feasible to use it, in whole

or in part, elsewhere in the system. Busing is not an

untried or new device for this District. Kemp v. Beas

ley, No. 19,782 (8th Cir., March 17, 1970) (Slip op.,

p. 14).

Similarly in Little Rock the Court took occasion to note

“that busing is not an alien practice” and had been used

by the District “ to preserve segregation” (Slip op. p. 20).

Following its 1968 decision in Brewer, supra, the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit has refused

to make the neighborhood school concept an inviolate prin

ciple in the way the Fifth Circuit believes it is. The Fourth

Circuit, although observing that “ [busing] is not a pana

cea,” has held that “busing is a permissible tool for achiev

ing integration.. . . ” Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board

of Education, No. 14,517 (4th Cir., May 26, 1970) (Slip op.,

p. 18). The court specifically condemned the School Board’s

rejection of a variety of legitimate techniques of desegre

gation.

The district court properly disapproved the school

board’s elementary school proposal because it left

about one-half of both the black and white elementary

pupils in schools that were nearly completely segre

gated. . . . The consultants that the board employed

were undoubtedly competent, but the board limited

their choice of remedies by maintaining each school’s

grade structure. This, in effect, restricted the means

of overcoming segregation to only geographical zon

ing, and as a further restriction the board insisted on

contiguous zones. The board rejected such legitimate

techniques as pairing, grouping, clustering, and satel

lite zoning (Slip op., pp. 22-23).

25

On remand, the Court held that “ every method of deseg

regation, including rezoning with or without satellites,

pairing, grouping, and school consolidation” should be ex

plored, and that “undoubtedly some transportation will be

necessary to supplement these techniques” (Slip op., p.

25). Nowhere is there any suggestion that the neighbor

hood school concept is an absolute bar to a plan entailing

the transportation of students.19 20

See also, Davis v. School Dist. of City of Pontiac, 309 F.

Supp. 734 (E.D. Mich. 1970); Spangler v. Pasadena City

Bd. of Educ., Civ. No. 64-1438-R (C.D. Cal., March 12,

1970); Crawford v. Board of Educ. of City of Los Angeles,

No. 822-854 (Super. Ct. Cal., February 11, 1970).

Ellis v. Board of Public Instruction of Orange County,

Florida, supra, suggests that the objectives served by

neighborhood schools are “ to eliminate transportation costs

and to permit the student to remain as near home as pos-

19 Petitioners wish to make clear that noting the conflict between

the Fourth and Fifth Circuits does not in any way constitute an

endorsement of the Fourth Circuit’s limitation of remedial power

by its “ reasonableness” doctrine. See Petition for Writ of Certi

orari, Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., No. 281, O.T.

1970, cert, granted, June 29, 1970, 38 U.S.L.W. 3522. 20

20 In a concurring opinion in Brewer v. School Bd. of City of

Norfolk, No. 14,544 (4th Cir., June 22, 1970), cert, denied, 38 U.S.

L.W. 3522 (June 29, 1970), Judges Sobeloff and Winter wrote:

The District Court should not tolerate any new scheme or

“principle,” however characterized, that is erected upon and

has the effect of preserving the dual system. This applies to

the “neighborhood school” concept, a shibboleth decisively re

jected by this court in Swann (Judge Bryan dissenting), as

an impediment to the performance of the duty to desegregate.

The purely contiguous zoning plan advanced by the Board in

that case was rejected by five of the six judges who partici

pated. A new plan for Norfolk that is no more than an overlay

of existing residential patterns likewise will not suffice. (Slip

op. at pp. 1-2)

2 6

sible” . Ibid. The absoluteness of the principle prevents

any inquiry into the extent to which alternative assignment

methods may in fact or law counteract these objectives.

If the saving of transportation costs is a legitimate objec

tive then the actual impact of a plan on these costs must

be appraised. Yet the Court of Appeals’ formulation of the

neighborhood school concept bars any determination of

these increased costs, the school board’s ability to bear

them, and the availability' of state assistance to defray a

portion of the costs. Mobile is a school district which en

gages in extensive busing (during 1967-68 207 buses trans

ported 22,094 students daily)21 and by examining its past

operation and present financial situation it would be pos

sible to determine the actual impact of an order requir

ing the transportation of additional students. Furthermore,

the court’s formulation permits no consideration of the

savings which transportation might enable in the system’s

school construction program. The School Board has been

enjoined since 1969 from constructing two additional schools

in Mobile’s black ghetto. 414 F. 2d at 610. The use of

presently unused capacity in white schools would eliminate

the need to construct these facilities and the use of trans

portation to better utilize existing* facilities might actually

save the school system money. Finally, if the facts show

that Mobile’s transportation expenditures must actually

increase beyond state assistance and savings in school con

struction costs, then the absoluteness of the court’s neigh

borhood school concept forecloses judicial consideration

whether the saving of money is a legitimate basis for main

taining racially separated schools.

The other objective which the neighborhood school con

cept is said to serve is allowing students to remain as close

21 The average round trip was 31 miles. (H.E.W. Report, July

10, 1969, p. 61).

27

to home as possible. Again the absoluteness of the neigh

borhood school concept prevents inquiry into the extent to

which alternative assignment systems counteract this objec

tive. The non-eontiguous zoning plan proposed by the

H.E.W. does not disperse students throughout the school

system without relationships to any neighborhood schools.

What the H.E.W. plan typically proposes to do is to re

quire students and parents to relate to two neighborhoods,

one black and one white, instead of to just one racial

neighborhood. If parents living in proximity to one an

other wish to organize to act upon school problems they

may still do so, except that they would hopefully work in

concert with the parents of the paired zone to solve mutual

problems. Yet no consideration may be given to these

views given the absoluteness of the court’s ruling below.

The Court of Appeals offers three alternatives to the

desegregation of all schools: an integrated educational

experience at some point in a child’s educational career,

a transfer policy allowing black students to transfer to

white schools with transportation provided, and the estab

lishment of a bi-racial committee to advise the School Board

(16a). None of these alternatives provides a remedy for

the constitutional wrong involved in maintaining racially

segregated elementary schools.

Offering an integrated education in junior and senior

high schools merely postpones the constitutional right to an

integrated education and does not grant it “now” . Alex

ander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396 U.S. 19

(1969). It also fails to consider the damage caused by five

or six years of segregated elementary education and the

difficulties black children will face in integrated junior and

senior high schools after a segregated elementary educa

tion. The second alternative, transfers with transportation

provided, unlawfully seeks to shift the burden from the

School Board back to black children. Freedom of choice

by whatever name has never worked in Mobile. Davis v.

Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County, 393 F.2d

690 and 414 F.2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1968-69). The third “ alter

native,” a bi-racial advisory committee, while probably sal

utary is not an alternative in fact. It is just an advisory

committee to an all-white and recalcitrant school board.

Finally the Court of Appeals offers the illusion that

“ open housing, Title VIII, Civil Rights Act of 1968 . . .

[and] Jones v. Mayer, 392 U.S. 409 (1969) . . . will serve

to prevent neighborhood entrapment” (16a). To the con

trary, open housing, which is a difficult enough goal to

achieve, will probably become even more difficult now that

the Court of Appeals has provided an added inducement

for whites to maintain neighborhood segregation. If, on the

other hand, everyone realized that no matter where any

one moved in the school system his children would attend

an integrated school—and assuming that local interest in

a neighborhood school system is strong—then the more the

Mobile community integrated its neighborhoods the less it

would have to transport students.

II.

This Court Should Grant Certiorari in Order to In

sure Petitioners’ Due Process Right to an Evidentiary

Hearing in the District Court.

The instructions of the Court of Appeals to the district

court on June 3, 1969, Davis v. Board of School Comm’rs of

Mobile County, 414 F.2d 609 (5th Cir. 1969), provided for

the submission of a new desegregation plan to replace free

dom of choice in Mobile, and that

3 . . . (e) For plans as to which objections are made

. , . the District Court shall commence hearings begin

ning no later than ten days after the time for filing

objections has expired.

29

Id. at 611 (emphasis supplied). Despite this dear man

date, and petitioners’ expressed objections to provisions

of the plan filed by the Mobile school board, the district

court acted August 1, 1969 without a hearing. Similarly,

on remand from this Court (sub nom. Garter v. West Feli

ciana Parish School Bd., supra, implemented sub nom.

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dist., No.

26285 (5th Cir., Jan. 15, 1970)), the district court merely

held a “ pre-trial conference” and then entered an order

on a permanent desegregation plan without affording an

opportunity for an evidentiary hearing.

The absence of a record upon which to review the district

court’s judgment led the Court of Appeals to issue a limited

remand for fact finding by the district court on specific

issues vital to determining the propriety of the district

court’s action, such as the extensiveness of Mobile’s pupil

transportation system. Yet again, the district court denied

petitioners’ motion for a hearing and made its findings

without petitioners’ having been able to confront the board’s

version of the facts and introduce evidence contradicting it.

Petitioner’s appeal below raised the denial of an eviden

tiary hearing as one of the issues, but the Court of Appeals,

which also acted summarily,22 ignored it.

22 The last regularly scheduled oral argument in a school deseg

regation case in the Fifth Circuit was held last summer, except for

one argument held March 18, 1970 in Bradley v. Board of Public

Instruction of Pinellas County, supra. Ten cases were removed

from the regular calendar and argued together en banc November

15-16, 1969. Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dist.,

supra, rev’d sub nom. Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd.,

supra. Since that time, more than twenty decisions in such cases

have been issued, all—with the exception of Bradley—without the

benefit of oral argument. In addition, since Singleton, all school

desegregation appeals have been subject to its vastly accelerated

time schedule, see 419 F.2d at 1222, which often requires briefing

and decision without benefit of a transcript. In light of the accel

erated and summary procedures of the Court of Appeals, the dis

trict court’s refusal to hold a hearing assumes even greater signifi

cance.

30

Petitioners submit that this consistent refusal to permit

them to present their case is contrary to the most funda

mental notions of due process. Particularly in our adver

sary system, courts rely upon the vigorous presentations

of counsel to sharpen issues, focus litigation, and bring out

the facts. Yet neither the district court, which selected and

modified a plan, nor the Court of Appeals, which selected

and modified a different plan, has heard counsel in this case.

The plans do, in a limited sense, speak for themselves.

Assuming arguendo that the district court might have se

lected a plan to be implemented pendente life without a

hearing, (and we submit that under the principles of Alex

ander and Garter, this Court should require the implemen

tation of Plan B-l Alternative pendente life) the final dis

position of a case of this magnitude affecting tens of

thousands of students should not be attempted without full

exploration of the facts. If the district court was under

the impression that it had an obligation to finally dispose

of the case by February 1, 1970 at the cost of a full explora

tion of the facts at a hearing, then the court misread

Carter and Alexander.

Only after a full hearing at which all parties have the

opportunity to present their evidence should the district

court rule on a permanent plan and in so doing, make

detailed findings of fact. The findings of the district court

in its January 31, 1970 order hardly acquit the court’s

obligation. The selection of isolated facts from a com

prehensive plan to desegregate a large school district pro

vides plainly inadequate support for whatever ultimate

conclusion the court may reach. Finally, if the court by

an appropriate standard does find isolated problems with

a comprehensive plan it should require amendments rather

than reject the plan in its entirety.

31

Merely remanding to the district court for an eviden

tiary hearing will serve no purpose, however, unless this

Court also makes clear that in devising a remedy for the

state-imposed dual school system in Mobile, neither the

school board nor the district court is in any way limited

by the “neighborhood school concept” expounded by the

Court of Appeals. And, pending such hearing and the

district court’s determination, this Court should require

Mobile to implement Plan B -l Alternative pendente lite.

Cf. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., supra

note 19.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons it is submitted that the peti

tion for certiorari should be granted to review the judg

ment of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

M ichael D avidson

N orman J. Ch a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

V ernon Z. Crawford

A lgernon J. Cooper

1407 Davis Avenue

Mobile, Alabama 36603

Attorneys for Petitioners

APPENDIX

Order o f District Court

I n the

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F or th e S outhern D istrict oe A labama

S outhern D ivision

Civil A ction No. 3003-63

B irdie M ae D avis, et al .,

and

Plaintiff,

U nited S tates oe A merica, by R amsey Clark ,

Attorney General, etc.,

Plaintiff -Intervenor,

vs.

B oard oe S chool Commissioners oe M obile Cou nty , et al .,

and

Defendants,

T w ila F razier, et al .,

Intervenors.

This Court entered a decree in this case on August 1,

1969, under which the public school system of Mobile

County opened and operated through the first semester of

1969. That part of the desegregation plan devised in said

order which was to be implemented in September 1970, was

in accord with recommendations of Health, Education and

la

2a

Welfare, with alterations or modifications to meet par

ticular educational principles. This Court’s decision was

appealed and was affirmed by the Fifth Circuit Court of

Appeals sitting en banc on December 1, 1969.

On January 14, 1970, the Supreme Court of the United

States reversed the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals and

remanded the decision to the Court of Appeals for further

proceedings consistent with the Supreme Court’s opinion.

On January 21, 1970, the Court of Appeals issued its man

date to this Court, which in effect stated that there could be

no deferral of school desegregation beyond February 1,

1970.

Faced with this mammoth task, the Court on its own

motion sought the advice and professional assistance of all

the parties. On the afternoon of January 23, 1970, the

Court conducted a pretrial conference with the attorneys

representing all of the parties and at such time the Court

requested attorneys for the school board and the govern

ment to submit a revision of the plans submitted by the

school board on December 1, 1969. The Court realizing

its plan of August 1, 1969, in some respects was still a

dual system, ordered the school board to submit a plan not

later than December 1, 1969, which would disestablish such

system, which plan was to be implemented on September

1, 1970. The Court also called upon the government for

revision of the HEW plan which the government thought

should be followed for the remainder of the present school

year. These revised plans were to be furnished to the

Court by 9 o’clock A.M. on the 27th day of January. The

government furnished the requested plans. The school

board did not, and by order dated January 28, 1970, at 9 :30

A.M., the school board was ordered to submit such revised

plans. As of this date, they have not done so. The school

Order of District Court

3a

board and its staff of administrators and professional edu

cators, who know the Mobile Public School System best,

who have all the facts and figures which are absolutely

necessary for a meaningful plan, have not assisted or aided

the Court voluntarily. Consequently, the plan which is by

this decree being ordered is not perfect, but the ten day

period from January 21st to February 1st obviously allows

inadequate time to work out an ideally legal and workable

plan for educating approximately 75,000 school children,

particularly when the change comes in mid-semester. This

plan pleases no one—the parents and students, the school

board, Justice Department, NAACP, nor in fact, this Court.

The Court’s plan closes schools which the school board

wants open. It opens schools which the Justice Department

wants closed. But a decision had to be made and it was

the duty and the responsibility of this Court to make that

decision. The Supreme Court of this country has spoken,

and this Court is bound by its mandate. It is the law. It

must be followed.

The revised HEW plan which the government submitted

to the Court would require no busing of students, but ex

tensive pairing of several schools. An alternate plan sub

mitted by HEW and upon which the plaintiffs insist, would

require the busing of children from areas of the city to a

different and unfamiliar area as well as the pairing of many

schools. The distance between some of the schools by

vehicular traffic would be approximately fifteen miles. The

government plan and the HEW plan would materially

change the grade structure for approximately thirty-four

schools, and in some instances, would completely change

each school’s identity. The government asked the Court

to close many of the high schools which are attended by

90% or more of Negro pupils, among them, Central High

Order of District Court

4a

and Mobile Training. This I am unwilling to do as I think

it would be unfair to the Negro population of this city.

Many of them have graduated from one or more of these

schools. They take pride in them. In many areas, includ

ing sports, there is much rivalry between these schools and

I do not think the traditions which they have created over

the years should be destroyed.

Under one of the HEW plans it would have necessitated

a child in the Austin area to attend Austin in the fifth grade

and from the sixth through ninth grades he would have to

change three times, namely, to Phillips, Washington and

Toulminville, and in the tenth grade to Murphy, thus at

tending five different schools in six years. Under one of

the HEW plans of pairing schools, a child would have gone

to Dodge in the first and second grades, Williams in the

third grade, and Owens in the fourth, fifth and sixth grades.

The distance from Dodge to Williams is approximately 8.6

miles and from Williams to Owens approximately 7.4 miles

and from Dodge to Owens, approximately 11.4 miles.

Admittedly these material changes in grade structures

and in identity, and the pairing of schools and the necessity

of busing great distances, are motivated for the sole pur

pose of achieving racial balance. In this Court’s opinion,

the Supreme Court has not held that such drastic techniques

are mandatory for the sole purpose of achieving racial bal

ance. By the same token, the Court is of the opinion that

such techniques in certain instances, must be utilized to re

move the effect of the dual school system.. Therefore, it was

necessary to change the grade structure on a limited basis

and in one instance, the identity of a school. These altera

tions were not motivated to achieve racial balance, but to

desegregate the public school system.

Order of District Court

5a