Rule v International Association of Bridge, Structural, and Ornamental Ironworkers Appellants Reply Brief

Public Court Documents

March 3, 1977

35 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rule v International Association of Bridge, Structural, and Ornamental Ironworkers Appellants Reply Brief, 1977. 23bd4a5b-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0d6ac690-39a1-4101-b884-d0c059002f5b/rule-v-international-association-of-bridge-structural-and-ornamental-ironworkers-appellants-reply-brief. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

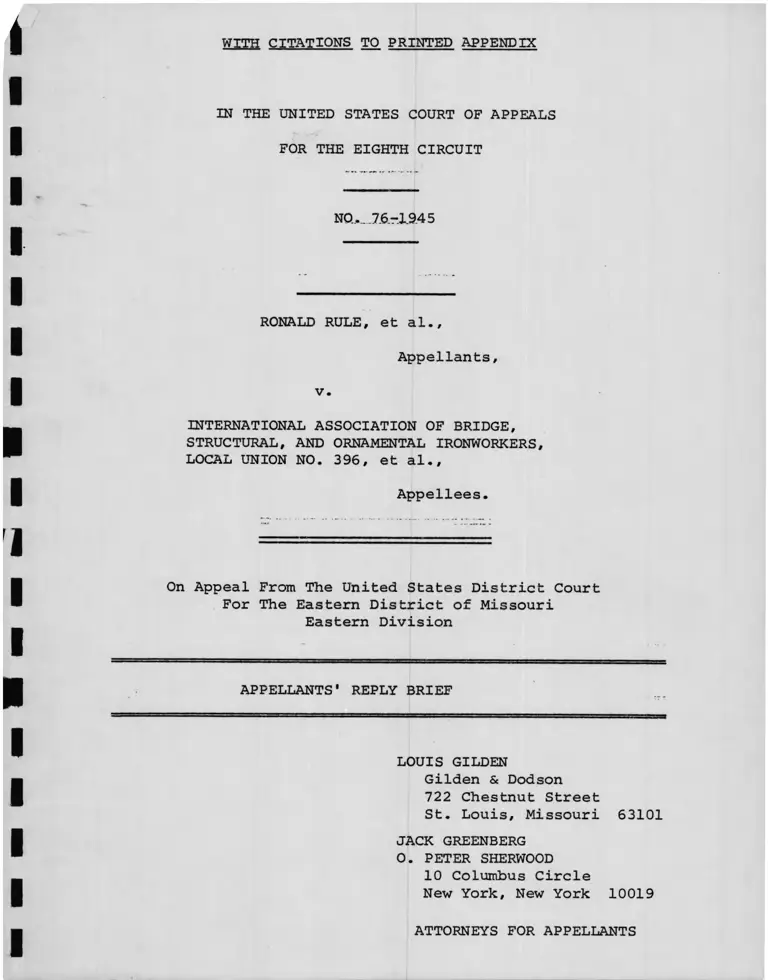

WITH CITATIONS TO PRINTED APPENDIX

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

NO., 7.6-194 5

RONALD RULE, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BRIDGE,

STRUCTURAL, AND ORNAMENTAL IRONWORKERS,

LOCAL UNION NO. 396, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Eastern District of Missouri

Eastern Division

APPELLANTS' REPLY BRIEF

■— ■■ ■i.'.a .t ".1 ■ ' .r .T .i ; . i : : ■ i ■■■j . ■ -■■■— ■■ r j . ’a ,i . „ r i.— :1 ' a : 1, .. J.. l ■ ■ i

LOUIS GILDEN

Gilden & Dodson

722 Chestnut Street

St. Louis, Missouri 63101

JACK GREENBERG

0. PETER SHERWOOD

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLANTS

INDEX

Table of Authorities ..................................... ii

I. STATEMENT OF FACTS

A. Introduction ..................................... 1

B. Current Effect Of The Consent Decree ........... 2

C. The Right To Solicit ................................. 3

D. Union Control Of Employment In The Trade ...... 4

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN DECERTIFYING THE

CLASS .............................................. 5

III. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN REFUSING TO ADMIT

PLAINTIFFS' EXHIBIT 26A ............................... 10

IV. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN REFUSING TO CONSIDER

CERTAIN EVIDENCE CONTAINED IN THE GOVERNMENT'S

CASE ................................................... 11

A. Evidence From The Government's Case Is

Admissible Under Rules 26(d) and 42(a)

F.R.Civ.P......................................... 12

B. Evidence From The Government's Case Is

Admissible Under Rule 801(d)(2), Federal

Rules of Evidence ......................... 10

V. THE DISTRICT COURTS' REFUSAL TO FIND THE

DEFENDANTS TO HAVE VIOLATED THE TITLE VII

AND SECTION 1981 RIGHTS OF THE NAMED

PLAINTIFFS WAS E R R O R .................................. 19

A. George Coe ....................................... 22

B. Lonnie R. Vanderson .................................. 22

C. Johnnie I. Brown ......................... 23

D. Willie West ...................................... 24

Page

i

Page

VI. DEFENDANTS VIOLATION OF THE CONCILIATION

AGREEMENT ......................................... 26

VII. CONCLUSION........................................ 26

Certificate of Service ................................. 27

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Afro-American Patrolman's League v. Duck, 503 F.2d

294 (6th Cir. 1974) 6

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405,

(1975) ............................................... 7,9,26

Arkansas Educational Association v. Board of

Education, 446 F.2d 763 (8th Cir. 1971) 6

Arney v. Geo. A. Hormel & Co., 53 F.R.D. 179

(D.C. Minn. 1971) .................................... 11

Baldwin-Montrose Chemical Co. v. Rothberg, 37 F.R.D.

354 (S.D. N.Y. 1967) ................................ 13,14,15

Barnett v. W. T. Grant Co., 518 F.2d 543 (4th Cir.

1975) 6

ii

Page

Carey v. Greyhound Bus Co., 500 F.2d 1372, (5th

Cir. 1975) ...................................... 6, 9

Cromwell v. County of Sac, 94 U.S. 351 ........... 25

In Re Cessna Air Distrib. Antitrust Litigation,

518 F.2d 213 (8th Cir. 1975) .................. 8

Cypress v. Newport News General & Nonsectarian

Hospital Assn., 375 F.2d 648, (4th Cir. 1967) .. 6

Demarco v. Eden, 390 F.2d 836 (2nd Cir. 1968) .... 6

Duplan Corp. v. Deering Milliken, Inc., 397 F.

Supp. 1146, (D.C.S.C. 1974) ................... 11

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 495 F.2d 398

(5th Cir. 1974) ................................ 10, 23, 24

Fullerform Continuous Pipe Corp. v. American Pipe

Construction Co., 44 F.R.D. 453 (D. Ariz.

1968) ........................................... 13, 15

Grogan v. American Brands, Inc., 70 F.R.D. 579,

(M.D.N.C. 1976) ................................ 8

Guerrino v. Ohio Casualty Insurance Co., 423 F.2d

419 (3rd Cir. 1970) ...... ..................... 15

Ikerd v. Lapworth, 435 F.2d 197 (7th Cir. 1970) ... 13, 15

In Re International House of Pancakes Franchise

Litigation, 536 F.2d 261 (8th Cir. 1976) ..... 8

Manning v. International Union, 466 F.2d 812 (6th

Cir. 1972), cert, denied 410 U.S. 946 ......... 10

Marquez v. Omaha District Sales Office, Ford Div.,

440 F.2d 1157 (8th Cir. 1971) ................. 19, 24

Miller v. Meinhard Commercial Corp., 462 F.2d 358

(5th Cir. 1972) ................................ 25

iii

Napier v. Bossard, 102 F.2d 467 (2nd Cir. 1939) ... 18

Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., 433

F .2d, 421 (8th Cir. 1970) ...................... 7, 19, 22,

24

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211

(5th Cir. 1974) ................................ 23

Philadelphia Housing Authority et al., v. American

R & S Corp., 323 F. Supp. 364 (E.D. Penn.,

1970) ........................................... 9

Reed v. Arlington Hotel Co., Inc., 476 F.2d 721

(8th Cir. 1973) ................................ 7

Resendis v. Lee Way Motor Freight, Inc., 505 F.2d

69 (5th Cir. 1974) .......................... 19

Rodriquez v. East Texas Motor Freight, 505 F.2d 40

(5th Cir. 1975) 10

Sagers v. Yellow Freight System., Inc. 529 F.2d 721

(5th Cir. 1976) 19

Salsman v. Witt, 466 F.2d 76 (10th Cir. 1972) .... 18

Shulman v. Ritzenberg, 47 F.R.D. 202 (D.D.C. 1969). 6

Sylgab Steel & Wire Corp. v. Imoco-Gateway Corp.,

62 F.R.D. 454 (N.D. 111. 1974) 11

Underwater Storage, Inc. v. United States Rubber Co.

314 F. Supp. 546 (D.D.C. 1970) 11

United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries, Inc.

517 F .2d *826, (5th Cir. 1975) ................. 25

United States v. Burr, 25 F. Cas. 30, (C.C. Va.

1807) ........................................... 7

United States v. Empire Gas Corp., 393 F. Supp. 903

(W.D. Mo.., 1975) 18

Page

iv

Page

United States v. Hayes International Corp., 456

F . 2d 112 (5th Cir. 1972) ............................ 19

Wetzel v. Liberty Mutual Insurance Co., 508 F.2d

239 (3rd Cir. 1975) ................................. 9, 10

Wilcox v. Commerce Bank, 474 F.2d 336 (10th Cir.

1973) ............................................ .... 9, 10

Wright v. Stone Container Corp., 524 F.2d 1058

(8th Cir. 1975) ...................................... 7

STATUTES AND RULES

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

Rule 23 ........................................... 6, 7, 8, 9

Rule 26(D) ........................................ 12, 15, 16,

18

Rule 32 (A) (3) ...................................... 16

Rule 42(A) ......................................... 12, 13, 15

16, 18

Federal Rules of Evidence

Rule 801 (D) 28 U.S.C.A............................ 16, 17, 18

Title vll of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42

U.S.C. §2000e, et seq................................ 25

OTHER AUTHORITIES

McCormick On Evidence §257, p. 201 .................... 12

McCormick On Evidence §257, p. 261 .................... 13

5 Wigmore, Evidence, 3d Ed 1940 § 1388 ................ 13

v

Page

See Weinsteins Evidence, 9801 (D)(2) [01]

at 1 801-115 ......................................... 17

McCormick On Evidence, §262, p. 629 ................... 17

Notes on Advisory Committee On Proposed Rules, Fed.

Rules Evid. , Rule 801 (D) (2), 28 U.S.C.A............ 17

vi

m THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

NO. 76-1945

RONALD RULE, et al.,

Appellan ts,

v.

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BRIDGE,

STRUCTURAL, AND ORNAMENTAL IRONWORKERS,

LOCAL UNION NO. 396, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Eastern District Of Missouri

Eastern Division

APPELLANTS' REPLY BRIEF

........ 1 asa— a » *~— i ■ — * n — 1 11 ■ ■ ■■- — ................ ■ ■■ ■< ■< cm ss— — 1 —

1 .

A . Introduction

Plaintiffs-appellants Ronald Rule, et al., hereby reply to the

brief filed by the defendants-appellees in this case. While the

defendants criticize the style of plaintiffs statement of the facts

there is little in their brief that either "supplement(s)" or point

to "correction of . . . errors and inaccuracies contained in

plaintiffs statement of the facts." (Defendants Brief at p. 5). To

the contrary defendants largely re-state facts set forth in plain

tiffs brief, excluding many of the material facts carefully documen

ted by plaintiffs in their opening brief.

We address here the few assertions of alleged inaccuracies

to which the defendants have referred.

B . Current Effect Of The Consent Decree

At page 3 of their brief the defendants state that "the

consent decree. . . remains in effect between all parties. . ."

Nothing in this record to~date indicates that the requirements of

the Consent Decree in No. 71-C-559 (2) would normally be effective

1/

beyond November 9, 1976. The defendants representation to this

Court that the Consent decree is still in effect does suggest that

they have failed^to achieve the goals set forth in paragraph 2 of

that court order. At page 11 of their brief

1/ Paragraph 39 of the Consent Decree states: Jurisdiction:

39. The Court shall retain jurisdiction over this action for

three (3) years from the date of its entry or until such time as

the Defendants have achieved the objective of this Decree, as set

forth in paragraph 2 above. The Defendants may apply to the Court

for termination of this Decree at any time prior to the end of the

three (3) year period and such a termination may be granted upon a

showing that the objective of this Decree has been met; the

Plaintiff will be allowed thirty (30) days to prepare its response

to any such application for termination. In the event that

Defendants fail to comply with any provision of this Decree,

Plaintiff United States shall notify Defendants, in writing, of

such noncompliance. If the Defendants have not, within fifteen (15)

days after receipt of such notification, remedied such noncompliance,

United States may apply to this Court for an order to show cause why

the provisions of this Decree should not be specifically enforced.

(A. ).

2/ As of the time of trial in April, 1975, the defendants had not

achieved compliance with that paragraph of the Consent Decree. In

1974 the Minority Training Program accepted only 13 of the 20 train

ees called for under paragraph 13 of the Consent Decree. (February

21, 1975 report to EEOC in Px-2) (A. ).

2

defendants intimate that the contractors have joined with the

union and have adopted the referral procedures set forth in

the Consent Decree. If this is the case, plaintiffs applaud

these efforts, albeit belated, to achieve equal employment

opportunity in the St. Louis ironwork trade.

C. The Right to Solicit

At pages 10-11 of their brief defendants state:

Ninety percent or more of all employment in

the ironwork industry within the local 396

jurisdiction is filled by direct hire without

referral by the union.

Prior to 1972 there was no agreement between

local 396 and the contractors regarding referral

of applicants for employment. There was no

referral system and all employees in the ironwork

trade could and did solicit their own employment

directly from contractors.

Plaintiffs have forthrightly stated that work in the

ironwork trade is obtained primarily by direct hire (Pi. Br.

p. 17). Prior to and since 1972 contractors would call the

union hall for referrals when they were unable to find a full

complement of ironworkers by direct hire. Ibid. (See also

Tr. 533-34) (A. 997) . Thus even though provision for referrals

by the union was not incorporated into the collective bargaining

agreements until 1972, the practice of referring ironworkers

from the union hall was not new (e.g. See Tr. 682, Quick depo.

at p. 19 and McGowan depo. at p. 89) (A.1145,43 0 1 and406 ) .

3/

3 / The contractors are not parties to the Consent Decree.

3

There is no dispute that permitmen did solicit work prior to

1972. Whether or not they could do so legally is in dispute.

(See PX-52 at pp. 8-9, Tr. 200, 682 and Quick depo. at pp. 19-20)

(A.251 ,6 6 4,1145, and430) . There is no dispute that ironworkers

having less than 6,000 hours of work in the trade prior to the

date of the 1972 letter agreement were prohibited by that agree

ment from soliciting work (See Johnson depo. in Government Case

at pp. 52-53) (A. 424a) and that this new requirement had a major

impact on the employment opportunities of black ironworkers,

4/

including plaintiff Rule. Further there is no dispute that prior

to 1972 journeyman ironworkers were referred for work before

permitmen. (See Johnson depo. in Government Case at p. 55 and

McGowan depo. at p. 108) (A.425,407).

D . Union Control of Employment in the Trade

At footnote 2 the defendants state:

Further, there is no evidence to support plaintiffs'

statements on pages 5 and 6 of its brief that Local

396 exercises 'exclusive control' of the ironworker

trade . . . Prior to the institution of the referral

system in 1972 no contractor was required to look

first to the union for workmen. Plaintiffs' asser

tions are unfounded and totally erroneous and mis

leading.

Plaintiffs do not claim that Local 396 exercises exclusive

control of the ironwork trade. Plaintiffs do properly assert

that the Local 396 exercises, both prior to and after 1972,

virtually exclusive control of employment in the construction

4/ In fact William Johnson, the Union's business agent admitted

that the purpose of the 1972 Letter Agreement (DX-E) (A. 273)

was to institute a seniority system to protect the older, all-

white ironworkers (See Johnson depo. at p. 87) (A. n o ) .

- 4 -

ironwork trade. As plaintiffs describe fully at pages 6-9 of

their brief that control is exercised through its authority

to admit journeymen, issue permits, indenture apprentices and

5/

enroll trainees. Both prior to and after the institution of

the referral system in 1972 any contractor having a collective

bargaining agreement with Local 396 who hired an ironworker who

was not duly indentured in the Local 396 joint Apprenticeship

Program or who did not possess a Local 396 journeyman's card or

a service dues receipt issued by Local 396, would be required

to terminate that employee on request of the union (See e.g.

PX-52 at pp. 4 and 8-9) (A. 250 , and 251 ). In short,

every contractor having a collective bargaining agreement with

Local 396 was (and is) required to hire Union approved workmen

only, except where the Union fails to supply them after reason

able notice (See e.g. PX-52 at p. 4) . (A. 250 ) .

II

THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED

IN DECERTIFYING THE CLASS

The defendants contend that the district court did not

abuse its discretion when it decertified the class herein. It

appears that the district court decertified the class on the

basis of the number of affirmative responses to the 460

notices mailed. To the extent that the district court based

5/ The Union's authority over apprentices and trainees is

shared, at least nominally, with contractor representatives.

-5-

its decision to decertify the class merely on the numbers of

responses returned, it failed to properly apply the applicable

law. The test of whether or not a class is so numerous that

joinder of all members is impracticable involves more than a

purely quantitative measurement. See e.g. Shulman v. Ritzenberg,

47 F.R.D. 202 (D.D.C. 1969); Demarco v. Eden, 390 F.2d 845

(2d Cir. 1968) . Clearly, no specific number of class members

is needed to maintain a class action under Rule 23. See

Cypress v. Newport News General & Nonsectarian Hospital Assn..

375 F.2d 648, 653 (4th Cir. 1967). Class actions consisting

of as few as 35, 23 or even 18 persons have been upheld. See

Arkansas Educational Assn, v. Bd. of Education, 446 F.2d, 763

(8th Cir. 1971); Afro-American Patrolman's League v. Duck.

503 F.2d 294 (6th Cir. 1974); and Cypress v. Newport News

General & Nonsectarian Hospital Assn., supra. The district

court's decertification of the class on the basis of failure

of plaintiffs to meet the numerosity requirement of Rule 23(a),

F.R. Civ. P., necessarily implies a finding that joinder is

practicable. Cf. Barnett v. W.T. Grant Co., 518 F.2d 543

547 (4th Cir. 1975). Here the district court did not consider

the impracticability of joinder of the minimum of 323 remaining

6/

class members.

Assuming the district court did-properly apply the

applicable law, its decision to decertify the class constitutes

a clear abuse of discretion. See Carey v. Greyhound Bus Co.,

6/ Indeed the district court limited the number of class members

that could be joined as plaintiffs to the 17 individuals who

affirmatively requested inclusion. The impracticability of

joining these few class members as plaintiffs is fully described

in plaintiffs' main brief at pp. 38-39. It appears that the

defendants recognize the impracticability of joinder in this

case given their curious silence on this question.

6

500 F.2d 1372, 1380 (5th Cir. 1975). Rule 23(c) (1) vests the

district court with the discretion to modify the class definition

and to decertify the class at any time before a decision on the

merits. That discretion is not left to the district court's

"inclination but to its judgment and its judgment is to be

guided by sound legal principles." See Albemarle Paper Co.

v. Moody, '422 U.S. 405, 416 (1975) quoting United States v.

Burr, 25 F. Cas. 30, 35 (C.C. Va. 1807). That a mere thirteen

(13%) of those who received notices requested exclusion is not

a basis for decertification of the class, particularly in the

circumstances of this case where the notice expressly advised

class members of their inclusion in the class if they chose not

to return it. The courts have long recognized that in exercising

its discretion under Rule 23(c) (1), F.R. Civ. P., the district

court should read the requirements of Rule 23 (a) liberally in

favor of class certification. This rule applies even more so

in the context of an action brought by Title VII. See e.g.

Reed v. Arlington Hotel Co., Inc., 476 F.2d 721, 723 (8th Cir.

1973) and Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., 433 F.2d

421. 428 (8th Cir. 1970). One of the very cases the defendants

cite supports this proposition:

Rule 23 should be liberally construed to

effectuate the remedial policy of Title VII

since the conduct . . . proscribed is

discrimination against a class characteristic.

Wright v. Stone Container Corp.. 524 F.2d

1058, 1061 (8th Cir. 1975).

In Wright this court upheld the district court's denial of

class certification but in doing so it stressed the "peculiar

circumstances" of that case. This Court noted not only the

plaintiffs' failure, after adequate opportunity for discovery,

7

to identify any person who was subjected to the same or similar

discriminatory treatment but also that he himself was not an

adequate•class representative because he had not applied and

was not qualified for the job in question. 524 F .2d at 1062.

Here plaintiff Rule identified literally scores of blacks who

were denied referral, admission to JAC and the MTP, were

6/

affected by the 6000 hour requirement, etc. . . (See Plain

tiff's Statement of Facts). Further Rule and the other plain

tiffs were directly affected by the very practices complained

of. (See PI. Br. at pp. 43-64.) In Grogan v. American Brands,

Inc. 70 F.R.D. 579, 581 (M.D. N.C. 1976), the only other

Title VII case cited by the defendant, the district court did

certify the class conditionally even though the record at that

time consisted of bare allegations.

A brief discussion of the other cases cited by defendant

in support of a wide Rule 23 discretionary power dispel the

notion of their applicability to this case. The case of In

Re Cessna Air Distrib. Antitrust Litigation, 518 F.2d 213 (8th

Cir., 1975), simply states that an interlocutory order granting

class standing in an action brought under the Robinson-Patman

Act is notsubject to appeal. Similarly unrelated to the issue

at hand is the case of In Re International House of Pancakes

Franchise Litigation, 536 F.2d 261 (8th Cir., 1976), involving

a claim that denial of a motion to be excluded from an anti-

6/ And of course seventeen (17) of the members of the class

affirmatively sought to be represented by plaintff Rule.

8

trust class action was an abuse of discretion, despite the fact

that appellant willfully ignored the deadline for exclusion

- the disregard of a clear deadline serving to provide the Court

with a standard for the exercise of its discretion. Appropri

ately, the denial was upheld.

Defendant also cites the case of Philadelphia Housing

Authority et al. v. American R&S Corp0, 323 F. Supp. 364 (E.D.

Penn., 1970). However, that case involved a dispute over

whether an appropriate class should have been determined before

settlement was proposed. The "wide discretion" granted the

judge under Rule 23 resulted in the original procedures being

upheld but the case again has no relevance to a Title VII action,

against which a judge's Rule 23 discretion "must be balanced with

the nature and intent of the Civil Rights Acts, whose purpose

is to provide a broad remedy for all who fit the plaintiff's

class." Carey v. Greyhound Bus Co., Inc., supra at 1380. Even

more inappropriate is defendant's citation of Wilcox v. Commerce

Bank. 474 F.2d 336 (10th Cir., 1973), which involved a denial of

class status in an action under the Truth in Lending Act, the

Court observing that "nothing in the Truth in Lending Act . . . .

suggests a Congressional intent that such cases should always,

or generally, be handled as class action." Both the courts and

Congress have recognized the class action as an appropriate

vehicle for challenges to discriminatory employment practices.

See e:.c[. Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, supra, 422 U.S. at 414

n. 8 and Wetzel v. Liberty Mutual Insurance Co., 508 F.2d 239,

250 (3rd Cir., 1975).

9

In summary, discrimination on the basis of race is

indubitably a class wrong. Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.,

495 F.2d 398 (5th Cir. 1974); Wetzel v. Liberty Mutual Insura

nce Co., supra, and a suit charging employment discrimination

is naturally "a sort of class action for fellow employees sim

ilarly situated." Rodriqez v. East Texas Motor Freight. 505

F.2d 40, 50 (5th Cir. 1974). Thus, this case presents the

instance postulated in Wilcox where "the class action procedure

is so manifestly superior . . . that an appellate Court on

review would be warranted in reversing the trial court's deter

mination to the contrary." Wilcox v. Commerce Bank, supra at

348; Manning v. International Union, 466 F.2d 812 (6th Cir.

1972) cert. denied 410 U.S. 946.

III.

THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED

IN REFUSING TO ADMIT

PLAINTIFFS1 EXHIBIT 26A

The crux of defendants' argument apropos the exclusion of

Exhibit 26A is that its disclosure of the exhibit was not

voluntary but rather compulsory pursuant to Notice to Produce at

Trial, and that the first opportunity defendants had to assert

the attorney-client privilege in relation to Exhibit 26A was at

the trial itself (Defendant's Brief at p. 23). Moreover,

defendant argues that it "could not invoke the attorney-client

privilege in regard to a document it refused to produce at

10

trial", and that it "had no choice" but to produce Exhibit

26A and object at trial (Defendants' Brief at p. 24). In so

contending defendant fundamentally misconstrues the applicable

law which is adequately set forth in plaintiffs' main brief.

We add only that if the defendants wished to protect the pri

vilege it was their obligation to object to the production of

any allegedly privileged document prior to its delivery to

plaintiffs. The district court would then have examined it in

camera and ruled on the defendants' objections. By delivering

the document to plaintiffs, without objection, any claim of

privilege was waived. Underwater Storage, Inc., v. United

States Rubber Co., 314 F. Supp. 546 (D.D.C. 1970); Puplan Corp.

v. Peering Milliken, Inc., 397 F. Supp. 1146, 1162 (D.C.S.C.

1974); Sylgab Steel & Wire Corp. v. Imoco-Gateway Corp. 62

F.R.D. 454 (N.D. 111. 1974); and Arney v. Geo. A. Hormel & Co.

53 F.R.D. 179, 181 (D.C. Minn. 1971).

IV.

THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN

REFUSING TO CONSIDER CERTAIN

EVIDENCE CONTAINED IN THE

GOVERNMENT'S CASE____________

In responding to plaintiffs' contention that the district

court judge erred in refusing to admit into evidence certain

portions of depositions and answers to interrogatories filed in

Civil Action No. 71-C-559(2)

defendant's state in a conclusory fashion that the evidence is

inadmissible for lack of "total identity of parties in both

11

actions, no substantial identity of issues and common

questions of law and fact." (Defendants' Brief at p. 26)

Furthermore, defendants' assert that plaintiffs'have not met

the standards set forth in their own cited cases. Defendants’

assertions rest on a fundamental lack of understanding of the

applicable law.

A. Evidence From The Government's Case Is

Admissible Under Rules 26 (d) and 42 (a)

F.R. Civ. P.

Defendants acknowledge that the same underlying issue of

unlawful racial discrimination is involved in both cases,

(Appellees Brief at p. 26) yet attempt to distinguish the two

actions on the ground that Civil Action No. 71-C-559(2) was

brought by the United States pursuant to Section 707 of Title

VII. While Sections 706 and 707 merely set forth separate

jurisdictional cases for suits by private parties and the

Government, the duties imposed on the defendants by Title VII

are the same regardless of who is seeking to enforce them.

2/

The remedies available are also the same. Moreover, it is

clear that "neither the form of the proceeding, the theory of

the case, nor the nature of the relief needs to be the same"

for evidence of a prior proceeding to be admissible in a

subsequent proceeding. McCormick on Evidence §257, p. 201.

Nor must the parties be identical. See Ikerd v. Lapworth,

7/ Of course, private plaintiffs but not the Government are

entitled to attorneys' fees.

- 12 -

435 F.2d 197 (7th Cir. 1970). It is generally recognized

that the test of admissibility of prior recorded testimony

is not "a mechanical one of identity or even substantial

identity of issues," but rather that "the issues in the

first proceeding must have been such that the party opponent

had adequate notice for testing the credibility of the

testimony" sought to be admitted in the present proceeding.

McCormick on Evidence, §257, p. 261; 5 Wigmore, Evidence, 3d

Ed. 1940 §1388; See Fullerform Continuous Pipe Corp. v .

American Pipe Construction Co., 44 F.R.D. 453 (D. Ariz. 1968).

Clearly, defendants had the same motive and interest to cross-

examine the deponents in the prior proceeding as they had in

the present action. In both No. 71-C-559(2) and this case,

plaintiffs alleged an across-the-board pattern and practice

8/

of racial discrimination; in both actions the defendants have

the same primary interest — disproving the existence of

racial discrimination. Compare Fullerform Continuous Pipe

Corp. v. American Pipe & Construction Co., supra. Even

assuming that different issues of law are present in this case

than in the previous proceeding, clearly this assertion is

immaterial since Rule 42 (a) merely requires a substantial

identity of either law or fact. See Baldwin-Montrose Chemical

8/ In this case plaintiffs also alleged and proved specific

unlawful discrimination. (See Plaintiffs' Brief at pp. 43-64).

13

Co v. Rothberq. 37 F.R.D. 354, 356 (S.D. N.Y. 1964).

Assuming further, as the defendants erroneously appear to,

that this case is limited to "instances of specific discrim

ination" a substantial identity of fact is present here be

cause many of the instances of discrimination about which

plaintiffs complain are the result of those same broad

discriminatory patterns and practices. See Plaintiffs Brief

at pp. 43-59.

Defendants further contend that the defendant MTP was

not a party to the prior proceeding, and that counsel for

defendants had no motive or interest in that proceeding

adequately to protect MTP's interest. This assertion dis

regards the fact that the parties in the Government's case had

no difficulty imposing substantial affirmative responsibilit

ies on the MTP even though it was not a named party (Tr. 334).

(A. 798) As this result indicates MTP's interest must

necessarily have been of concern to defendants' and MTP's

interest in cross-examination was the same as the parties'

interest who were present in that action, since the identical

issue of racially discriminatory practices was raised. Thus,

although it is generally the rule that a deposition is not

admissible as to one not having the opportunity to be present

at its taking, the presence of an adversary with the same

motive and interest to cross-examine the deponent, and a

substantial identity of issues in the two proceedings, provide

14

a well-recognized exception to the rule. See Ikerd v. Lapworth.

435 F.2d 197 (7th Cir. 1970). As is the case here, the party

in the present proceeding in Fullerform Continuous Pipe Corn.

v. American Pipe & Construction Co., supra, was not

present to cross-examine the deponents at the prior proceeding,

but the substantial identity of issues and fact as well as the

abundance of motive and interest possessed by defendants to

cross-examine the deponents, provide the guarantee of trust

worthiness sufficient to warrant admission of the relevant

portions of the prior testimony. The result in Fullerform,

supra should compel a similar finding here and thus the

district court here erred in refusing to recognize that Rules

26 (d) and 4 2 (a) when taken together authorize the use of the

depositions and interrogatories offered by plaintiffs without

a showing that the witnesses were unavailable. See Guerrino v .

Ohio Casualty Insurance Co., 423 F.2d 419, 421 (3d Cir. 1970);

Fullerform Continuous Pipe Corp. v. American Pipe & Construction

Co., supra; Baldwin-Montrose Chemical Co. v. Rothberg, supra,

at 356. In any event, the evidence in the Government's case

offered by plaintiffs in this case primarily addresses the

discriminatory practices of Local 396 and JAC, and not the MTP.

Thus, even if not admissible as to the MTP the evidence in the

Governments case remains admissible as to the other defendants.

Defendants further assert that although plaintiffs base

15

their argument on Rule 26(d) and 42 (a) F.R.C.P., the "answer

actually is found in Rule 32 (a) (3) of the Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure, which sets out the requirements for the use

of the deposition of a witness at trial" (Defendants' Brief

at p. 26). Although defendants blithely ignore those decis

ions, cited supra, which hold that availability of a witness

is immaterial under Rules 26(d) and 4 2 (a) taken together, it

is clear for yet another reason that Rule 32(a) (3) is

inapplicable.

B. Evidence From The Government's Case Is Admissible

Under Rule 801 (d) (2), Federal Rules of Evidence

It is clear that defendants Local 396 and JAC were

parties in No. 71-C-559(2) as well as in the present case.

Defendants entered into a consent order with the United States

Department of Justice in No. 71-C-559(2), based in part on an

implied admission of the facts outlined in the depositions and

answers to interrogatories. These admissions were made by

ranking officials of Local 396, JAC or the MTP acting their

capacity as agents of those entities. (See Plaintiff's Brief

at n. 66) Hence these depositions fall well within the para

meters of admissibility set forth in 801 (d) (2), Fed. Rules

9/Evid., 28 U.S.C.A.

9/ Rule 801 (d)(2) provides:

A statement is not hearsay if offered against a party and

is A) his own statement, in either his individual or a

representative capacity or B) a statement of which he has (CONT'D)

16

And such evidence is receivable whether or not the declarant

is available or appears as a witness. See Weinstein1s

Evidence, 5 8 OI (d) (2) [01] at p. 801-115.

Thus, the court below may have erred in accepting defend

ants’ characterization of the admissions of the parties as prior

recorded testimony. The admissions of a party-opponent are ex

cluded from the category of hearsay, on the theory that the

admissibility in evidence is the result of the adversary system

rather than satisfaction of the conditions of the hearsay rule."

Notes of Advisory Committee on Proposed Rules, Fed. Rules Evid.,

Rule 801 (d) (2), 28 U.S.C.A.; McCormick, Evidence, §262, p. 629.

The decision by the court below flies in the face of the intent

of the drafters of Rule 801 (d) (2), who contemplated "generous

treatment of this avenue of admissibility," Id.

Moreover, an analysis of the applicability of Rule 801(d)

(1) (A) indicates even more strongly that the depositions and

answers to interrogatories from No. 71-C-559(2) should not

have been excluded from evidence. Applying that Rule to the

instant case, even if the deponents had all appeared at the

9/ (CONT'D)

manifested his adoption or belief in its truth, or C) a state

ment by a person authorized by him to make a statement concern

ing the subject, or D) a statement by his agent or servant

concerning a matter within the scope of his authority or employ

ment, made during the existence of the relationship.

Pub. L. 93-595 §1, Jan. 2, 1975, 88 Stat. 1938.

-17-

subsequent proceeding and has been subject to cross-examina

tion, the import and relevance of the deposition for their

substantive value would not be diminished. If the

deponents on cross-examination had offered testimony-

inconsistent with their deposition (or even consistent),

the statement in the deposition would still be admissible

as substantive evidence, since under Rule 801(d) (1)(a) it

would not be hearsay.

In the face of the strong federal policy manifested in

the rules favoring the admissibility of depositions as

admissions under Rule 801(d)(1)(2) and as prior recorded

testimony under Rules 26(d) and 42(a) F.R.Civ. P. conjoined,

defendants' assertion of authority to the effect that dep

ositions are to be disfavored as evidence deserves little

credence. In the cases cited by defendants, the depositions

either were not taken under circumstances affording an

opportunity for cross-examination, or were based on a trial

involving different issues, or were "obviously based upon

hearsay and rumor," See United States v. Empire Gas Corp.,

393 F. Supp. 903 (W.D. Mo., 1975); Napier v. Bossard, 102

F.2d 467 (2nd Cir. 1939); Salsman v. Witt, 466 F.2d 76

(10th Cir. 1972). Those obvious infirmities

clearly do not obtain here. The court below committed error

in excluding the depositions from evidence.

- 18

Finally, we note defendants implicit concession that the

depositions and interrogatories in the Governments case are

judicially noticeable in this case.

V.

THE DISTRICT COURTS' REFUSAL TO FIND

THE DEFENDANTS TO HAVE VIOLATED THE

TITLE VII AND SECTION 1981 RIGHTS OF

THE NAMED PLAINTIFFS WAS ERROR______

The defendants do not appear to challenge, except in

conclusory fashion, the pervasive pattern of unlawful racial

discrimination disclosed in this record and summarized in

plaintiffs main brief. They assert that plaintiffs "have

relied exclusively on statistics as their source of proof

that defendants have engaged in racial discrimination"

(emphasis added) (Def. Br. at p. 28). While plaintiffs do

10/rely on statistics, this record is replete with non-statis-

tical evidence of unlawful racial discrimination against

blacks seeking entrance into the trade and against the

10/ See e.g., Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., 433

F.2d 421, 426 (8th Cir. 1970)? United States v. Hayes

International Corp., 456 F.2d 112,. 120 (5th Cir. 1972) and

Sagers v. Yellow Freight System Inc., 529 F.2d 721, 729

(5th Cir. 1976) as to the use of statistics in establishing

a prima facie case of unlawful racial discrimination as to

named plaintiffs in a Title VII class action. See also

Resendis v. Lee Way Motor Freight, Inc., 505 F.2d 69 (5th

Cir. 1974); Marquez v. Omaha Distr. Sales Office, Ford Div.,

440 F.2d 1157 (8th Cir. 1971) as to the application of

statistics in individual cases.

- 19

]

plaintiffs individually. That evidence includes application

of a discriminatory high school diploma requirement to

plaintiff Rule; 2) application of unlawful tests to

plaintiffs Coe and Vanderson; 3) refusal to issue service dues

receipts to plaintiffs Rule, West and Nichols even though the

Union had issued such service dues receipt to whites having no

greater qualification; 4) application of the letter agreement

to plaintiff Rule;and 5) the outright refusal to even talk to

plaintiff West when he first sought referral.

"The reasons relating to the insistence of the Union for

a referral system" (Def. Br. at p. 30) is plain enough - it

wanted to preserve job security for its older members. (See

Johnson depo. at p. 87) (A.HO). Its effect was to deprive previous

ly excluded blacks, including plaintiff Rule (See PI. Br. at

p. 32), of the opportunity to find work in the trade. Given

the undisputed proof in this record of the effects of the new

referral system on plaintiff Rule, the defendants statement

at page 31 of their brief that "plaintiffs are unable to

adduce a shred of evidence disclosing that any harm resulted

to them by reason of the institution of the referral provis

ions contained in the 1972 agreement" is mere brutum fiiinm.

At page 31 of their brief defendants suggest that

plaintiffs seek to prohibit the coordinators of JAC and the

MTP from referring trainees and apprentices. Nothing is

20

further from the fact. Plaintiffs merely seek establishment

of a procedure that would assure trainees and apprentices

an equal share of referrals. The coordinators of both

programs would continue to solicit. They would merely be

required to assure that trainees receive a fair share of all

referrals.

The defendants continue to argue that the Flanigan test

passes muster under Title VII because EEOC has registered no

protest as to its use. (Def. Br. at p. 32). The Consent

Decree prohibits use of any tests "unless the test has been

properly differentially validated. . ." (Consent Decree at

?8). JAC has never differentially validated the Flanigan

test. True, JAC informed EEOC of its intention to rein

troduce the test but JAC never complied with the precondit

ion of having the Flanigan "properly differentially validated"

and never submitted any validity study as required by the

Consent Decree (Consent Decree 5[8) (A. 447) . JAC's reliance

on its self-serving letter to EEOC is much too thin a reed on

which to base a claim for an exemption from the requirements

of Title VII.

The defendants have said nothing in their briefs as to

u /

the claims of plaintiffs Davis and Nichols and Rule not fully

11/ Defendants' assertion at page 35 of their brief that

plaintiff Rule was unavailable for any contact by the Union

or JAC between 1966 and 1972 is refuted by their own

description of his whereabouts. (See Def. Br. at p. 17).

(CONT'D)

21

anticipated in plaintiffs main brief or that warrant

reemphasis here. The claims of and entitlement to relief

of plaintiffs Coe, Vanderson, Brown, and West are

adequately discussed there as well. However out of an

abundance of caution plaintiffs add the following comments

addressed to certain factual or legal assertions made as

to them.

A. George Coe

It serves JAC little to point out that plaintiff Coe

was afforded the opportunity to be reconsidered in 1971.

(Def. Br. at p. 32). Coe was unlawfully excluded from JAC

in 1970. See Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co.,

433 F.2d 421 (8th Cir. 1970) . JAC1s offer to subject him to

the same discriminatory selection procedures in 1971 is

12/

hardly a remedy.

B . Lonnie R. Vanderson

It appears that plaintiff Vanderson was in fact denied

admission to JAC (See Def. Br. at p. 33) because of the

unlawful JAC selection procedures. Defendants misconstrue

11/ (CONT'D)

He was in St. Louis for all but one year during that entire

period. Whether or not he was available for contact would

not shield the Union or JAC from liability in any event

because they never made any attempt to reach him.

12/ The defendants' statement without citation to the record

that JAC indentured 8 or 9 blacks in 1970 (Def. Br. at p. 32)may

be inaccurate. Charles Adam, the JAC coordinator testified

(CONT'D)

- 22

the proper allocation of the burden of proof at this point. It

is JAC's burden to demonstrate by clear and convincing evidence

that plaintiff Vanderson would not have been admitted to JAC

even in the absence of these unlawful selection procedures. See

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211, 259 (5th

Cir. 1974), and Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747,

772 (1976). JAC failed to meet its burden. Accordingly Vanderson

is entitled to a remedy.

C. Johnnie I. Brown

The defendants assert that plaintiff Brown "offered no

evidence that persons equally lacking in skills were referred by

Local 396. . ." (Def. Br. at p. 34). The record is filled with

evidence of the Union issuing service dues receipts to

who were no more qualified for ironwork than plaintiff

(Tr. 197, 394, 605-06). (A. 661, 858, 1068).

students

13/

Brown.

12/ (CONT'D)

that just 2 of the 80 individuals indentured into JAC in 1970

were black (Tr. 611) (A. ). However, the JAC Admission No. 39

shows 84 whites and 8 blacks indentured that year. (A. 80 ).

13/ The following testimony in the Government case by Herman

McGowan, former Business Agent for Local 396 clearly demonstrates

that lack of qualification was no impediment to obtaining a

"permit" for„ the privileged:

Q. (By Mr. Cronin) While you have been Business Agent,

have summer employees ever been put to work by the

union, temporary employees?

A * Yes* (CONTINUED)

23

(A. ). The defendants cite to Marquez v .

Omaha Distr. Sales Office. Ford Div.. 440 F.2d 1157 (8th

Cir. 1971) is inapposite in the circumstances of this

case. Clearly Title VII does not require the union to

issue permits to or refer persons who are unqualified,

see Marquez. supra, but the Union may not use qualifications

standards to exclude minorities where it has not, as here,

consistently applied those same standards to whites. See

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., supra, 424 U.S. at 773,

n. 32.

D. Willie West

Defendants ignore the district court's finding that

plaintiff West applied in 1969. His subsequent refusal

years later to enter the MTP or accept the opportunity for

Union membership is irrelevant to the issue of liability.

See Parham, supra.

13/ (CONT'D)

* * * *

Q. Before you were Business Agent, was the same practice

prevalent then too?

A. About five years ago I was running a job and my son

was out of school and I had him work two weeks for me.

That is the only time he ever ironworked. (Emphasis

added).

(McGowan Depo. at pp. 122-23). (A. 408-409).

24

Defendants also assert that because plaintiff West was

singled out for certain relief in the Consent Decree, he is

in privity with the United States and therefore is not

entitled to relief here. In support they cite two cases;

neither is applicable. Cromwell v. County of Sac, 94 U.S.

351 was premised on a finding the former suit was brought for

the sole use and benefit of the plaintiff in the later suit.

This suit was brought under Section 706 of Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended to vindicate personal

rights guaranteed to plaintiff West thereunder. The

Government sued under Section 707 to vindicate the broad

public interest in eliminating unlawful practices. See

United States v. Alleqhenv-Ludlum Industries, Inc., 517 F.2d

826, 843 (5th Cir. 1975). Thus the Government sought to

vindicate interests different from those of the plaintiffs.

Unlike Miller v. Meinhard Commercial Corp., 462 F.2d 358

(5th Cir. 1972) , a bankruptcy case, plaintiff West was not a

part to any of the proceedings in the Government's case.

Indeed they never received any notice prior to the entry of

the Consent Decree that his rights were being compromised.

He never accepted the minimal relief offered thereunder and

certainly did not sign any waiver of his rights.

25

VI.

DEFENDANTS' VIOLATION OF THE CONCILIATION AGREEMENT

Defendants' violations of the MCHR Conciliation Agreement

and plaintiffs' entitlement to enforcement in federal court is

adequately set forth in plaintiffs main brief.

More than ten years have elapsed since plaintiff Ronald

Rule was denied the right to find a job in the St. Louis

ironwork trade. In the intervening years the defendants have

evaded or defied the clear mandate of the law and as a result

he and other similarly situated blacks, including those that

are named plaintiffs here, have suffered from its effects.

Not until late 1973 did the defendants take the first halting

steps to remedy the effects of their violations of the law.

To this day, a full remedy has not been achieved and the

district court has failed to provide one. See Albemarle Paper

Co. v. Moody, supra. This Court must at last assure plain

tiffs and similarly situated blacks their remedy.

VII

CONCLUSION

Respectfully submitted

Gilden & Dodson

722 Chestnut Street

St. Louis, Missouri 63101

26

JACK GREENBERG

0. PETER SHERWOOD

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLANTS

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this day of March,

1977, I served a copy of the foregoing APPELLANTS'

REPLY BRIEF upon counsel for defendants, Barry J. Levine, Esq.,

Gruenberg, Souders & Levine, 905 Chemical Building, 721 Olive

Street, St. Louis, Missouri 63101, by United States Mail,

Postage prepaid.

27

. - t •

• ' r •