Garner v. Memphis Police Department Brief for Plaintiff-Appellant on Remand from the Supreme Court of the United States

Public Court Documents

June 14, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Garner v. Memphis Police Department Brief for Plaintiff-Appellant on Remand from the Supreme Court of the United States, 1985. c7e1e3d3-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0d7991c8-bb3f-4882-b06f-cd29c3902522/garner-v-memphis-police-department-brief-for-plaintiff-appellant-on-remand-from-the-supreme-court-of-the-united-states. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

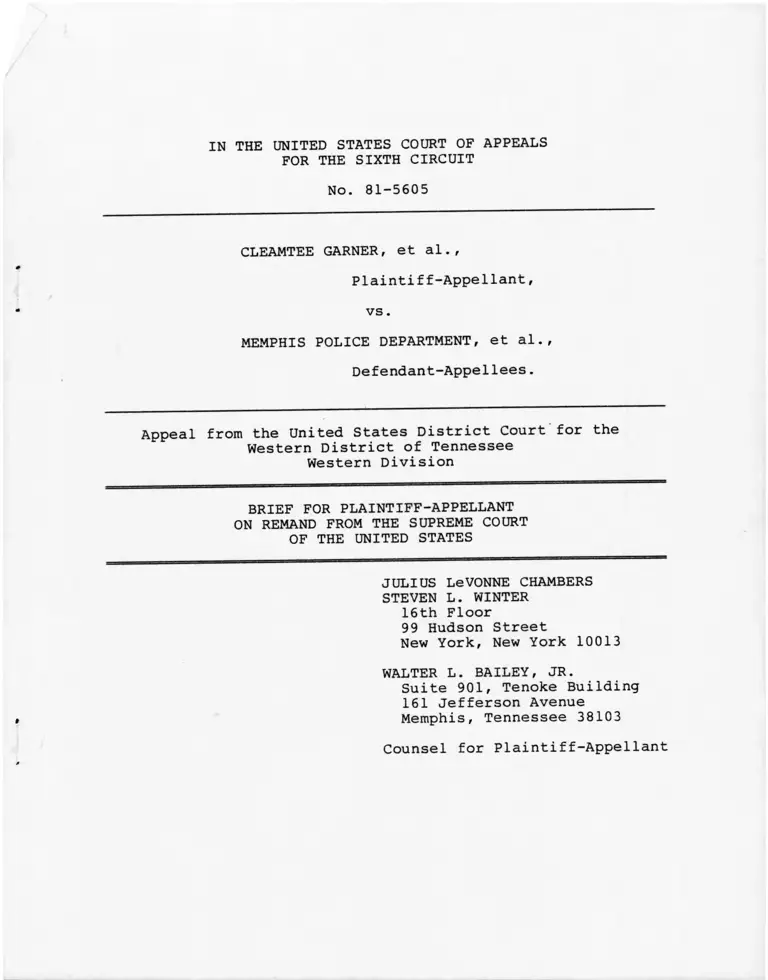

No. 81-5605

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

CLEAMTEE GARNER, et al.,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

vs.

MEMPHIS POLICE DEPARTMENT, et al.,

Defendant-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Western District of Tennessee

Western Division

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT

ON REMAND FROM THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE UNITED STATES

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

STEVEN L. WINTER

16th Floor

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

WALTER L. BAILEY, JR.Suite 901, Tenoke Building

161 Jefferson Avenue

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Counsel for Plaintiff-Appellant

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Cases....................................

Question Presented ............................. .

Statement of the Case .......................... .

Summary of Argument ............................

Argument ........................................

The City of Memphis Is Liable under Monell

Because the Shooting Death of Edward Eugene

Garner by a Memphis Police Officer Was

Merely the Execution of an Explicit

Policy of the Police Department ...........

A. A City Is Liable under § 1983

when Its Official Policy Directs

an Unconstitutional Act ..........

B. Mr. Garner Is Entitled to Judgment

Against the City Because the Facts

Already Found Establish that the

Unconstitutional Shooting Death

of his Son Was Merely the Execution of an Official, Unconstitutional

Policy of the City of Memphis ....

Conclusion ......................................

Certificate of Service .........................

Appendix ........................................

Page

ii

1

1

7

8

8

9

12

15

17

18

-l-

TABLE OF CASES

Page

Bennett v. City of Slidell, 728 F.2d 762

(5th Cir. 1984) 11

Brandon v. Holt, 469 U.S. ____, 83 L.Ed.2d 878

( 1985) ......................................... 15

City of Atlanta v. Gilmere, 737 F .2d 894

(11th Cir. 1984) ..............................* 11

Garner v. Memphis Police Dept., 600 F.2d 52

(6th Cir. 1979) ................................ 2' 3' 14' 15

Garner v. Memphis Police Dept., 710 F.2d 240

(6th Cir. 1983) ................................ 2' 4' 6

Languirand v. Hayden, 717 F .2d 220

(5th Cir. 1983) ................................ 11

Monell v. Department of Social Services,

436 U.S. 658 (1978) Passim

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 ( 1961) .............. 2

Oklahoma City v. Tuttle, 53 U.S.L.W. 4639

(June 3, 1985) ................................. 8' 9' 1 1 '12, 15

Owen v. City of Independence, 445 U.S. 662

(1980) ......................................... 4

Rymer v. Davis, 754 F .2d 198 (6th Cir. 1985) ..... 11

Tennessee v. Garner, 471 U.S. ____,

85 L .Ed. 2d 1 ( 1985) ........................... 2' 6, 14

Thayer v. Boston, 36 Mass. 511 ( 1836) ............ 12

Turpin v. Mailet, 619 F.2d 196 (2d Cir. 1980) .... 12

Statutes

Tenn. Code Ann. 39-901 ........................... 33

Tenn. Code Ann. 40-808 ........................... 3 • 33

-ii-

No. 81-5605

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

CLEAMTEE GARNER, et al.,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

vs.

MEMPHIS POLICE DEPARTMENT, et al.,

Defendant-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Western District of Tennessee

Western Division

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT

ON REMAND FROM THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE UNITED STATES

QUESTION PRESENTED

1. Is the City of Memphis liable under Monel1 v.

Department of Social Services, 436 U.S. 658 (1978), for the

unconstitutional shooting death of appellant's son by a

Memphis police officer who was merely executing an explicit,

official policy of the Memphis Police Department?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This case is before the court on remand from the

Supreme Court, which affirmed the judgment of this court

that the shooting of a fleeing burglary suspect without

piobable cause to believe that he is dangerous or has com-

mitted a violent crime violates the fourth amendment.

Tennessee v. Garner, 471 U.S. ____, 85 L.Ed.2d 1 (1985),

aff'q 710 F.2d 240 (6th Cir. 1983). The basic facts are

summarized in this court's first opinion:

On the night of October 3, 1974 a fifteen

year old unarmed boy broke a window and entered

an unoccupied residence in suburban Memphis to

steal money and property. Two police officers,

called to the scene by a neighbor, intercepted

the youth as he ran from the back of the house

to a six foot cyclone fence in the back yard.

Using a 38-calibre pistol loaded with hollow-

point bullets, one of the officers shot and

killed the boy from a range of 30 to 40 feet as

he climbed the fence to escape. After shining

a flashlight on the boy as he crouched by the

fence, the officer identified himself as a

policeman and yelled "Halt." He could see

that the fleeing felon was a youth and was

apparently unarmed. As the boy jumped to get

over the fence, the officer fired at the upper

part of the body, as he was trained to do by

his superiors at the Memphis Police Department.

He shot because he believed the boy would elude

capture in the dark once he was over the fence.

The officer was taught that it was proper to

kill a fleeing felon rather than run the risk

of allowing him to escape.

Garner v. Memphis Police Dept., 600 F.2d 52, 53 (6th Cir.

1979).

* /The complaint was filed in April 1975. A. 2 .—

In a pretrial ruling, the district court dismissed the case

against the Memphis Police Department and the City of Memphis

under § 1983, relying on Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961).

*/ Citations are to the Joint Appendix filed on appeal in

No. 81-5605. Because of multiple use and repaginations, the

page numbers of the Joint Appendix are underlined and can be

found at the bottom center of the Joint Appendix pages.

-2-

After a bench trial the court ruled for the defendants on

all issues. A. 35.

On appeal, this court affirmed the dismissal of the

case against the individual defendants based on their qualified,

good faith immunity in relying on Tenn. Code Ann. § 40-808,

which had not been held unconstitutional. It reversed and

remanded the case against the city for reconsideration in

light of Monell v. Dept, of Social Services, 436 U.S. 658

(1978). It listed four specific questions to be included in

the district court's consideration of the case.

1. Does a municipality have a similar qualified

immunity or privilege based on good faith

under Monell?

2. If not, is a municipality's use of deadly force

under Tennessee law to capture allegedly

nondangerous felons fleeing from nonviolent

crimes constitutionally permissible under

the fourth, sixth, eighth and fourteenth

amendments?

3. Is the municipality's use of hollow-point

bullets constitutionally permissible under

these provisions of the Constitution?

4. If the municipal conduct in any of these respects violates the Constitution, did the

conduct flow from a "policy or custom" for

which the City is liable in damages under

Monell?

600 F.2d at 54-55 (footnotes omitted).

On remand, the district court answered "yes" to the

first three questions: that the city is protected by a good

faith immunity defense; that the use of deadly force under

these circumstances is constitutionally permissible; and

3-

that the use of hollow-point bullets is constitutionally

permissible. Order of July 8, 1981, Slip op. at 7-8; A. 61-

62. On that basis, it answered "no” to the last: "There was

demonstrated no constitutionally impermissible 'custom or

practice' in the record." Slip op. at 8; A. 62.

On appeal, this court reversed. With regard to the

first question, this court held that the decision in Owen v.

City of Independence, 445 U.S. 662 (1980), "precludes a

municipality's claim of good faith immunity under § 1983

altogether." Garner v. Memphis Police Dept., 710 F.2d 240,

248 (6th Cir. 1983). With regard to the second, it held

that the application of the Tennessee law to authorize the

shooting in this case violated the fourth amendment and the

due process clause. Id. at 246. Accordingly, it did not

reach the third question or any of Mr. Garner's alternative

constitutional t h e o r i e s . T h i s court remanded for further

proceedings in the district court without any discussion of

the question of municipal liability under Monell in light

of the constitutional holding. Id.

The Supreme Court granted certiorari and noted probable

jurisdiction of the state's appeal. In the Supreme Court,

Mr. Garner argued the fourth amendment and due process clause

theories in support of this court's ruling. He also argued

1/ In the district court and on appeal in this court, Mr.

Garner also argued that: 1) the killing of unarmed, nondangerous

fleeing suspects amounts to punishment in violation of the

due process clause; 2) the Memphis policies and customs

encourage the excessive and unconstitutional use of deadly

force; 3) the use of hcllow-point bullets violates the Consti

tution; and 4) the Memphis policy of shooting nondangerous,

fleeing property crime suspects is racially discriminatory.

Arguments 2) and 4) are the alternative grounds, discussed

below, that Mr. Garner also raised in the Supreme Court.

-4-

two alternative grounds in support of this court's judgment,

only one of which is relevant at this time.—/ He argued

that, even if the common law fleeing felon rule were con

stitutional, the judgment could be affirmed on the basis of

the Memphis policies and customs that "encourage and in

sulate the excessive and unnecessary use of deadly force in

situations, such as the instant case, where the officer has

failed to exhaust reasonable alternatives." Brief for

Appellee-Respondent, Nos. 83-1035 & 83-1070, at 33.

In support of this ground, Mr. Garner cited both the

record of the original 1976 trial and material from the

extensive 1980 offer of proof assembled on remand to the

district court. This evidence established both a pattern

and practice of excessive use of deadly force and several

policies and customs that indicate "a police department that

arms and trains its officers to shoot to kill, encourages

them to rely on their revolvers rather than to exhaust other

alternatives, and assures them that they may do so without

guidelines and with impunity." Id. at 13. It is not neces

sary to canvass this material because this question is not

relevant to the question now before this court. Suffice it

to say that Mr. Garner marshalled the relevant evidence and

asked the Court to rule on the excessiveness issue "despite

the record and the lack of findings below." I_d. at 14.

2/ The second alternative ground was the race discrimination

claim that Mr. Garner raised on the previous appeal in this

court. See n. 1, supra. That claim was premised on evidence

contained only in the offer of proof.

-5-

The Supreme Court reached neither of the alternative

grounds — and, thus, did not need to consider the "uncertain

record" — because it affirmed this court's ruling under the

fourth amendment. The Court held that the Tennessee statute

is unconstitutional as applied to this case, 85 L.Ed.2d at

10, and that the use of deadly force by Officer Hymon against

Edward Eugene Garner violated the fourth amendment. Id. at

15-16. In reaching the latter conclusion, the Court echoed

this court's determination that Hymon shot without probable

cause to believe that Garner was dangerous or had committed

a violent crime. Compare 85 L.Ed.2d at 15—16 with 710 F.2d

at 246. It further rejected the notion that probable cause

to believe that Garner had committed a burglary was sufficient

to authorize the use of deadly force to prevent his escape.

Id. In light of these holdings, the Court remanded for further

proceedings. It noted that there was a question of the

city's liability under Monel1, but declined to consider the

question because of "the absence of any discussion of this

issue by the courts below" and because of "the uncertain

state of the record." Id.

When the Supreme Court issued its judgment, Mr. Garner

asked this court for leave to file a brief on remand, which

was granted. The purpose of this brief is to set out why

this court should rule for Mr. Garner on the remaining Monell

issue and then remand to the district court to determine the

amount of damages and enter a final judgment.

-6-

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Monell issues come in different sizes and shapes, and

different levels of difficulty. Some Monell issues require

the court to infer a municipal policy or custom from a course

of conduct or series of incidents. Other, similar Monell

claims ask the court to assess the existence of a municipal

policy or custom on the basis of actions not taken, such as

failure to discipline or to train adequately municipal police

officers. Then, there are Monell claims that concern only

the question of policy simpliciter: when a city has an

official policy that explicitly directs the unconstitutional

act. In its current posture, this case presents only the

last, easiest Mone11 question of policy simpliciter.

In the Supreme Court and on the prior appeal, Mr.

Garner raised a Mone11 claim of the inferential sort as a

lesser constitutional ground that would support a judgment

for plaintiff even if the common law fleeing felon rule had

been upheld. That claim was based on the hybrid record of

the 1976 trial and the 1980 offer of proof. In that claim,

Mr. Garner asked the courts to infer a policy of excessive

use of deadly force, beyond that authorized by the common

law rule.

Now that the Supreme Court has affirmed this court

and held that the common law rule is unconstitutional as

applied to this case, however, the nature of the Monell

issue is simplified; it is a case of policy simpliciter.

-7-

On the basis of the district court findings rendered after

the 1976 trial as affirmed by this court in 1979, it is

indisputable that the Memphis deadly force policy, General

Order No. 5-74, explicitly authorized this unconstitutional

shooting. Accordingly, this case is controlled by Monell

itself, where there was an explicit municipal policy direct

ing the very unconstitutional act. Here, as in Monell, the

municipal policy was "the moving force of the constitutional

violation." Monell, 436 U.S. at 694. Mr. Garner is thus

entitled to judgment against the City of Memphis.

ARGUMENT

THE CITY OF MEMPHIS IS LIABLE UNDER MONELL

BECAUSE THE SHOOTING DEATH OF EDWARD EUGENE

GARNER BY A MEMPHIS POLICE OFFICER WAS MERELY

THE EXECUTION OF AN EXPLICIT POLICY OF THE

POLICE D E P A R T M E N T _____________________

Decision in this case does not depend upon "the full

range of questions, and subtle factual distinctions, that

arise in administering the 'policy' or 'custom' standard..."

required by Monell. Oklahoma City v. Tuttle, 53 U.S.L.W.

4639, 4642 (June 3, 1985). Rather, in its current posture,

this case presents the relatively simple question that was

decided in Monell itself: whether a city is liable for an

unconstitutional act by one of its employees during the

course of his employment when an official, explicit policy

made by a municipal policymaker directs precisely that

conduct. In the sections that follow, we first discuss

-8-

the standards that control decision of that question. We

then turn to the findings made by the district court, as

affirmed by this court on the first appeal, that conclusively

demonstrate the city's liability in this case.

A. A City Is Liable under § 1983 when Its Official

Policy Directs an Unconstitutional Act

While the Court has not yet defined "the full

contours of municipal liability under § 1983...," Oklahoma

City v. Tuttle, 53 U.S.L.W. at 4639 (quoting Monel1, 436

U.S. at 695), it has recently taken some "small but neces

sary step[s] toward defining those contours." Id. In Tuttle:

"Respondent did not claim ... that Oklahoma City had a 'custom'

or 'policy' of authorizing its police force to use excessive

force in the apprehension of suspected criminals...." Id.

at 4642. Rather, she premised her claim of municipal liability

for the shooting death of her husband on the allegedly inadequate

training and supervisory policies of the Oklahoma City police

department. Id. The Tuttle Court reversed the jury verdict

against the city because of an incorrect instruction that

allowed the jury to infer a municipal policy from "a single,

unusually excessive use of force [which] may be sufficiently

out of the ordinary to warrant an inference that it was

attributable to inadequate training or supervision...." Id.

at 4640, 4642. This holding was supported by a seven-member

majority.

In a plurality opinion, Justice Rehnquist then

turned to the standards governing the ascertainment of a "policy"

-9-

under Monell. He distinguished between the case where the

plaintiff proves an "incident of unconstitutional activity

... that ... was caused by an existing, unconstitutional

municipal policy, which policy can be attributed to a muni

cipal policymaker ..." and that "where the policy relied

upon is not itself unconstitutional...." Id. at 4643. In

the latter case: "There must be an affirmative link between

the ... inadequacies alleged, and the particular constitutional

violation at issue." Id. at 4643 n. 8. In the former

case, he affirmed the holding in Monell: When a "policy in

and of itself violated the [Constitution ..., it requires

only one application ... to satisfy fully Monell1s require

ment that a municipal corporation be held liable only for

constitutional violations resulting from the municipality's

official policy." Id. at 4643.

The plurality opinion also discussed some of the

parameters governing claims of municipal policy on the basis

of omissions, such as inadequate training. It suggested

that "'policy' generally implies a course of action con

sciously chosen from among various alternatives...." Id.

Thus, in addition to the "affirmative link" of causation, a

plaintiff must show "that the inadequacies resulted from

conscious choice...." Id.

The plurality opinion did not attempt to sketch

out all varieties of the Mone11 question, although it cited

with apparent approval three court of appeals decisions that

further develop the Monell standard. Id. at 4642. (citing

-10-

Bennett v. City of Slidell, 728 F.2d 762 (5th Cir. 1984);

City of Atlanta v. Gilmere, 737 F.2d 894 (11th Cir. 1984),

rehr'q en banc pending; Lanquirand v. Hayden, 717 F .2d 220

(5th Cir. 1983)). In Gilmere, the Eleventh Circuit discussed

the imposition of "liability on municipalities for deprivations

of constitutional rights visited pursuant to municipal policy,

whether that policy is officially promulgated or authorized

by custom." 737 F.2d at 901. In the latter case, there may

be municipal liability "even though such custom has not

received formal approval through the body's official decision

making channels." Monell, 436 U.S. at 691; Gilmere, 737

F.2d at 901. "Custom" comprises "those practices of city

officials that are 'so permanent and well settled' as to

'have the force of law.'" G i lmere, 7 37 F. 2d at 901 ((quoting

Monell 436 U.S. at 691).

Thus, the case law makes clear that there are

Monell claims of different kinds and levels of complexity,

subject to different standards of proof. There are cases

where an informal "policy" or "custom" must be inferred from

a pattern and practice. There are cases premised on an

official municipal policy that is not itself unconstitutional,

where a close causal connection must be shown. There are

claims premised on omissions, where the Tuttle plurality

would require that a deliberate policy choice be proved.

See, e,q., Rymer v. Davis, 754 F.2d 198 (6th Cir. 1985)

(municipal liability premised on decision not to require

-11-

pre-employment training of police force). Municipal liability

may also be premised on an unconstitutional act later adopted

or ratified by the city. Cf. Turpin v. Mailet, 619 F.2d

196, 201 (2d Cir. 1980) (dicta).-7

Despite these varied permutations spawned by the

Monel1 standard, it is important not to lose sight of the

Monel1 holding: It imposed municipal liability under § 1983

when "the action that is alleged to be unconstitutional

implements or executes a policy statement, ordinance, regu

lation, or decision officially adopted or promulgated by

that body's officers...." Monell, 436 U.S. at 690. In that

case, a city is liable because of its policy simpliciter.

As the Court reaffirmned in Tuttle: "To establish the con

stitutional violation in Monell no evidence was needed other

than a statement of the policy by the municipal corporation,

and its exercise...." 53 U.S.L.W. at 4643.

B. Mr. Garner Is Entitled to Judgment

Against the City Because the Facts

Already Found Establish that the

Unconstitutional Shooting Death of

his Son Was Merely the Execution of

an Official, Unconstitutional Policy

of the City of Memphis

The Monell claim previously raised as a lesser

alternative ground, that the Memphis policy was one of excessive

use of force beyond that authorized by the common law, was

3/ in Tuttle, the plurality opinion cited "the famous case

of Thayer v. Boston, 36 Mass. 511, 516-517 (1836)," as "in

harmony with the limitations on municipal liability expressed

in Monell." 53 U.S.L.W. 4642 n. 5. Thayer approved municipal

liability for officials' acts later "adopted and ratified by

the corporation." Id.

-12-

an inferential claim of policy and custom. It was premised

on a pattern and practice, on omissions in discipline and

training, and on various deliberate policy choices by the

Memphis Police Department. There were no findings by this

court or the district court on these points; the factual

material was, in the main, contained in the "uncertain record"

of the 1980 offer of proof. But the Monell claim now confront

ing this court in light of the Supreme Court's affirmance is

one of policy simpliciter. On that claim, the record is

clear and the requisite findings have already been made.

After trial on the merits in 1976, the district

court found that: "Memphis Police instructors ... taught

police to fire at the largest target present, usually the

trunk or torso area, the 'center mass.' Police were given

instruction also by legal advisors on the Tennessee law with

respect to the use of lethal force." Memorandum Opinion

of September 29, 1976, Slip op. at 6-7; A. 27—28. "Under

TCA 40-808 and under regulations of the Memphis Police Depart

ment issued thereunder lethal force may be used by police

officers to apprehend persons fleeing from the commission of

certain felonies.... Burglary of a residence is one of the

felonies covered under this statute and under Tennessee law,

TCA 39-901. Lethal force may be resorted to in order to

apprehend a person fleeing from the commission of a burglary

such as that in which deceased Garner was involved...." Slip

op. at 9-10; A. 30-31 (citations omitted). Indeed, the

official policy promulgated by the Memphis Police Department

-13-

and signed by the director of police, General Order No. 5—

74, instructed that to apprehend a suspect "DEADLY FORCE is

authorized in the following crimes.... (h) Burglary in the

1st, 2nd, or 3rd degree___" General Order No. 5-74 at 2;

A. 1009. (For the court's convenience, a copy of General

Order No. 5—74, which is already in the record, is attached

as an appendix to this brief.)

On the first appeal, this court affirmed the

relevant findings: that "the officer fired at the upper part

of the body, as he was trained to do by his superiors at the

Memphis Police Department ...," that the officer "shot because

he believed the boy would elude capture," and that the officer

"was taught that it was proper to kill a fleeing felon rather

than run the risk of allowing him to escape." 600 F .2d at

53.

In affirming this court, the Supreme Court held

both that this particular shooting was unconstitutional, 85

L.Ed.2d at 15-16, and that a shooting premised solely on

probable cause to believe that the fleeing suspect had com

mitted a nighttime burglary is unconstitutional. Id.

If one assembles the rulings at all three levels,

the result of this case is entirely clear. The Memphis

policy authorized the shooting and killing of fleeing burglary

suspects without probable cause to believe that they are

dangerous. That policy is unconstitutional. Tennessee v.

Garner, 85 L.Ed.2d at 15-16. In shooting and killing Edward

Eugene Garner, Officer Hymon was merely executing that municipal

-14-

policy; he shot and killed Garner, a fleeing suspected felon,

as he "was taught." 600 F.2d at 53. Memphis is liable for

the act of its police officer, which "implements or executes

a ... regulation ... officially adopted or promulgated by

that body's officers...." Monell, 436 U.S. at 690 (emphasis

a d d e d ) . M r . Garner is entitled to judgment against the

City of Memphis because as "in Monell no evidence is needed

other than a statement of the policy by the municipal cor

poration, and its exercise ...." Tuttle, 53 U.S.L.W. at

4643.

CONCLUSION

Ten years and nine months ago, a Memphis police

officer acting pursuant to an officially promulgated order

and regulation of the Memphis Police Department shot and

killed Mr. Garner's son. The Supreme Court's ruling makes

clear that both the shooting and the municipal policy which

explicitly authorized it violate the fourth amendment.

4/ General Order No. 5-74 was an order issued by the Director

of Police, Director Hubbard, and later "incorporated into

the department's Manual, of Policies, Procedures and Rules

and Regulations." Id. at 3; A. 1010. As such it was a

"regulation ... officially adopted." Monell, 436 U.S. at

690. The policy decisions of the Memphis Director of Police

are, in Tuttle's terms, "attribut[able] to a municipal policy

maker." 53 U.S.L.W. at 4643. See Brandon v. Holt, 469 U.S.

, 83 L.Ed.2d 878 (1985) (judgment against Director of

Memphis Police in his "official capacity" for supervisory

policies he adopted confers liability on City of Memphis).

-15-

policy; he shot and killed Garner, a fleeing suspected felon,

as he "was taught." 600 F.2d at 53. Memphis is liable for

the act of its police officer, which "implements or executes

a ... regulation ... officially adopted or promulgated by

that body's officers...." Monell, 436 U.S. at 690 (emphasis

a d d e d ) . M r . Garner is entitled to judgment against the

City of Memphis because as "in Monell no evidence is needed

other than a statement of the policy by the municipal cor

poration, and its exercise ...." Tuttle, 53 U.S.L.W. at

4643.

CONCLUSION

Fourteen years and nine months ago, a Memphis police

officer acting pursuant to an officially promulgated order

and regulation of the Memphis Police Department shot and

killed Mr. Garner's son. The Supreme Court's ruling makes

clear that both the shooting and the municipal policy which

explicitly authorized it violate the fourth amendment.

4/ General Order No. 5-74 was an order issued by the Director

of Police, Director Hubbard, and later "incorporated into

the department's Manual, of Policies, Procedures and Rules

and Regulations." Id. at 3; A. 1010. As such it was a

"regulation ... officially adopted." Monell, 436 U.S. at

690. The policy decisions of the Memphis Director of Police

are*, in Tuttle's terms, "attribut [ able] to a municipal policy

maker." 53 U.S.L.W. at 4643. See Brandon v. Holt, 469 U.S.

, 83 L .Ed.2d 878 (1985) (judgment against Director of

Memphis Police in his "official capacity" for supervisory

policies he adopted confers liability on City of Memphis).

-15-

Accordingly, Mr. Garner is entitled to judgment against

the city. The judgment of the district court for the City

of Memphis should be reversed and the case remanded for the

assessment of damages, the award of attorneys' fees under

§ 1988, and the entry of final judgment.

Respectfully submitted,

J. LeVONNE CHAMBERS

STEVEN L. WINTER

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

WALTER L. BAILEY, JR.Suite 901, Tenoke Building

161 Jefferson Avenue

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

(901) 521-1560

Counsel for Plaintiff-Appellant

-16-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that copies of the foregoing Brief

for Plaintiff-Appellant on Remand have been served by placing

same in the United States mail, postage prepaid, addressed

to Henry L. Klein, Esquire, 770 Estate Place, Memphis, Tennessee

38117, Clifford D. Pierce, Jr., City Attorney, 314-125 N.

Mid America Mall, Memphis, Tennessee 38103, this )^_th day of

June, 1985.

Counsel for Plaintiff-Appellant

NUMBER: 5_74 □atsi 5 February 1974

SUBJECT. USE OF FIREARMS AND DEADLY FORCE

1. PURPOSE.

To define circumstances under which DEADLY FORCE and

FORCE may be used to prevent the commission of an

effect an arrest.

NON-DEA-OLY

offense an^ to

2. BACKGROUND.

a. Definitions.

the discharge

calculated toAs used 1n this order, DEADLY FORCE means

a firearm; or the use of force by other means

Inflict serious bodily Injury or death.

NON-DEADLY FORCE means the use of force by methods,

1ng a night stick or similar weapon, not calculated nor

to Inflict serious bodily Injury or death.

of

i nclud-

i ntended

b. AppI 1 cabU 1 ty.

The procedures defined 1n this order apply to the use of

firearms under the following circumstances-

(1) Situations Involving the use of firearms by depart

mental personnel 1n the line of duty Involving „he Preven

tion of-an offense or apprehension of an offender whethe.

or not death or a wounding occurs as a result.

(2) In any case Involving the accidental or negligent

discharge of firearms Involving departmental personnel in

the line of duty not covered under sub-paragraph (i) above.

3. ACTION.

a. Non-deadlv Force.

An officer may use NON-DEADLY FORCE when 1t is necessary to:

n n w

2

(1) Effect an arrest;

t o \ Prevent the escape from custody of a person who is

£ U . o « b ” i«p!ct“ /having committed an offense; or to

(3) Defend one's self or another 1n cases not Involving -

serious bodily Injury or death.

b. Deadly Force.

ncaniv PDRrr mav be used 1n the following circumstances only

afterEal1 otSerEreason!b" meins to apprehend or otherwise prevent

the offense have been exhausted:

(1) Self-Defense.

An officer may use DEADLY FORCE when ft Is in the

. r ... gf himself or another from serious bodily injury o

d!lth !nd thl“ hriat of serious bodily Injury or death is

real and immediate.

(2) Felonies Involving the Use or Threatened Use of Physical

Force.

An officer may use DEADLY FORCE when the offense involves

a felonyandthe suspect uses or attempts to use or threatens

the use of physical force against any person.

(3) Other Felonies Where Deadly Force is Authorized

After all reasonable means of preventing or fPPrfhending

a suspect have been exhausted, DEADLY FORCE 1s authorized

the following crimes:

Kidnapping „ J J

Murder in the 1st or 2nd degree

Manslaughter

Arson (Including the use of firebombs)

Assault and battery with intent to carnally know

a child under 12 years of age

Assault and battery with intent to commit rape

Burglary in the 1st, 2nd, or 3rd degree

Assault to commit murder 1n the 1st or 2nd d.grse

Assault to commit voluntary manslaughter

Armed and simple robbery

c. Use* of Deadly Force Prohibited.

The use of DEADLY FORCE 1s prohibited when:

(1) Arresting a person for any misdemeanor offense; or

100:)

- J -

\

(2) Effecting an arrest of any person for escape from

the commission of any misdemeanor offense.

d. Use of Firearms Prohibited.

(1) As warning shots;

(2) From any moving vehicle or to stop any fleeing vehicle,

except 1n cases of self-defense or cases Involving:

(a) Murder 1n the 1st or 2nd degree

(b) Rape

(c) Assault and battery with Intent to carnally know

a child under 12 years of age

(d) Armed or simple robbery

(3) In any case where an officer does not have a clear field

of fire and cannot be reasonably certain that only the sus

pect will be hit and that the potential for harm to innocent

persons or their property is minimal.

e. Notification Procedures.

(1) Once the situation 1s under control, any member who dis

charges a firearm 1n the line of duty will Immediately report the

fact to the Dispatcher who will have the cognizant watch or

squad commander notified. The latter will Inform the precinct

or bureau commander of the event,without delay. As soon as

practicable, the officer who fired a weapon will submit a written

narrative of the circumstances, via the chain of command, to the

Chief of Police, with copies to the Senior Member of the Firearms

Review Board and to the Commanding Officer of the Firing Range.

In addition, Form F2100.149 shall be filled out and forwarded to

the Firing Range.

(2) In any case resulting in death or wounding, the cognizant

watch or squad commander,or h1s designated representative, will

proceed to the scene and will relieve the offlcer(s) concerned

pending completion of the Inquiry that will be conducted by the

Firearms Review Board. In addition, the Dispatcher will notify

the Homicide Squad and the Internal Affairs Bureau as rapidly

as possible. Preservation of the scene will be the responsibility

of the senior commander present.

4. SELF-CANCELLATION.

This order shall remain in effect until its provisions have been

incorporated into the department's Manual of Policies, Procedures *nd

Rules and Regulations.

Distribution: A