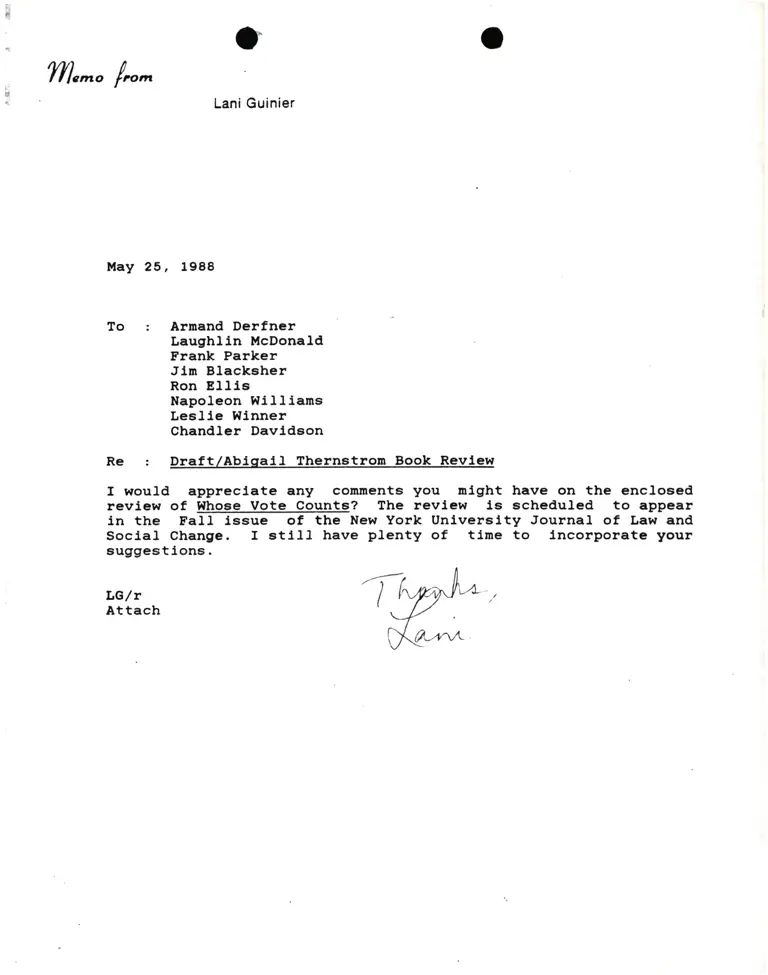

Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Derfner, McDonald, Parker, Blacksher, Ellis, Williams, Winner, and Davidson Re Draft/Abigail Thernstrom Book Review

Correspondence

May 25, 1988

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Derfner, McDonald, Parker, Blacksher, Ellis, Williams, Winner, and Davidson Re Draft/Abigail Thernstrom Book Review, 1988. 2b34217b-ec92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0d9e4b43-2d87-4cd5-ad90-d31530c02bc6/correspondence-from-lani-guinier-to-derfner-mcdonald-parker-blacksher-ellis-williams-winner-and-davidson-re-draftabigail-thernstrom-book-review. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

Tl1",no /-^

Lani Guinier

May 25, 1988

To : Arnand Derfner

Laughlln McDonald

Frank Parker

Jln Blackeher

Ron Bllle

Napoleon t{llllans

Leelle Wlnner

Chandl.cr Davl.deon

Re:

I would appreclate any connents you ntght have on the encloeed

revlaw of Whoae Vote Counte? The revlew ls echcdufcd to appcar

ln the Fall lssue of the New York Unlverelty Journal of Law and

Soclal Change, I atll.l have plenty of tlme to incorporate your

euggestlon6.

LG/r

Attach Tg,J'*,

*4-'""