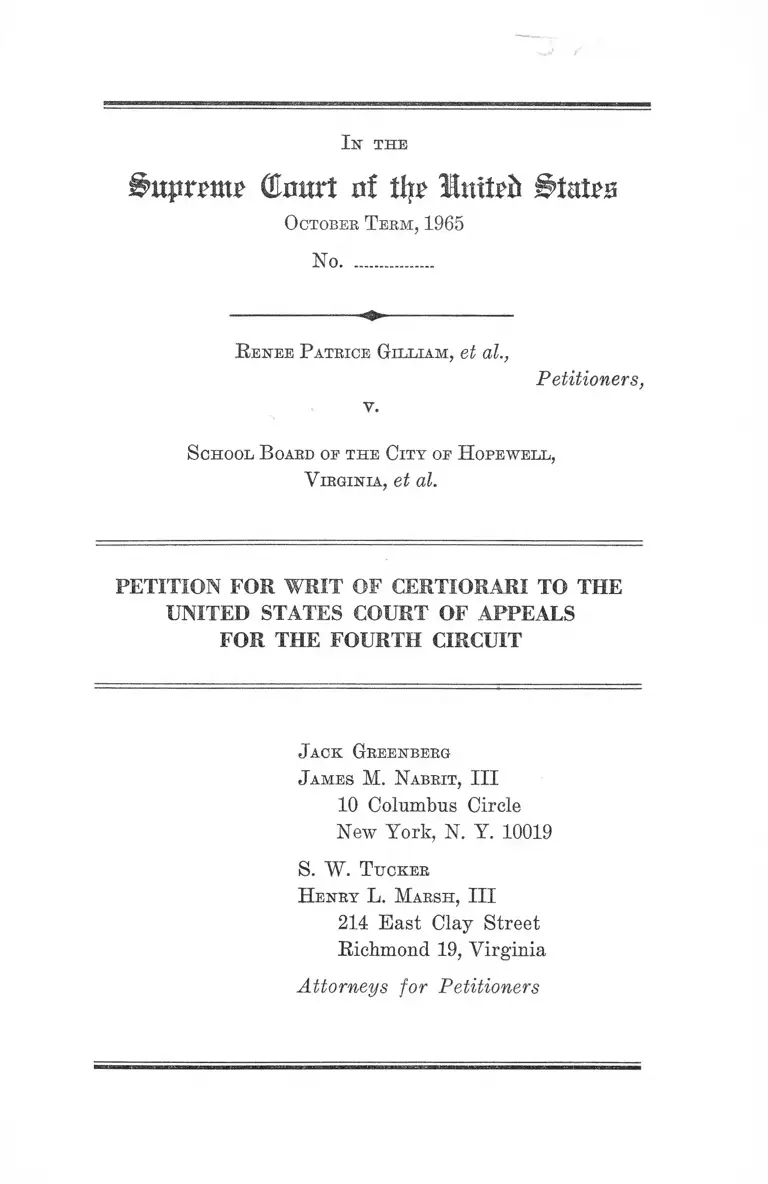

Gilliam v. City of Hopewell, VA School Board Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gilliam v. City of Hopewell, VA School Board Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, 1965. 304e2c65-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0da5c23a-5688-4e7f-aeb6-f4acabe43793/gilliam-v-city-of-hopewell-va-school-board-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-united-states-court-of-appeals-for-the-fourth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

(Emirt of tip Imtpft States

O ctober T erm , 1965

No.................

R e n ee P atrice G illia m , et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

S chool B oard op t h e C ity op H opew ell ,

V irg in ia , et al.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

S. W. T ucker

H enry L. M arsh , III

214 East Clay Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

Citations to Opinions Below ........................ .................. 1

Jurisdiction ................ ................................................... 2

Questions Presented............................................... ........ 2

Statutes and Constitutional Provisions Involved........ 3

Statement of the Case........ ...... ......................... ........... 3

Reasons for G-ranting the Writ ......................... .......... 17

I. The Pupil Assignment Plan Approved Below

Operates to Minimize Desegregation and Is

Not Adequate to Correct Racial Segregation

Created by Public Officials .............................. 19

II. Segregation of Public School Faculties Vio

lates the Fourteenth Amendment and Should

Be Abolished .................................................... 30

Conclusion............ 41

Appendix........................................ la

Memorandum of July 11, 1963 .......................... ....... la

Ruling of April 6, 1964 ............... ............................... 9a

Opinion Dated May 25, 1964 ................................... . 15a

Ruling of July 2, 1964 .......... ..... ................................ 22a

Order Entered July 6, 1964 ...................................... 26a

PAGE

11

Opinion Dated April 7, 1965 ....................................... 27a

Judgment of April 7, 1965 ....................................... 37a

Map ................................................. ............................ 39a

PAGE

T able oe Ca se s :

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U. S. 399 ................................ 34

Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction of Escambia

County, 306 F. 2d 862 (5th Cir. 1962) ......................... 33

Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U. S. 31 ................................ 30

Bell v. School City of Gary, Ind., 324 F. 2d 209 (7th

Cir. 1963), cert, denied, 377 U. S. 924 ......................... 27

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County v. Brax

ton, 326 F. 2d 616 (5th Cir. 1964), cert, denied, 377

U- S. 924 .............................................................. ......33, 38

Bowditch v. Buncombe County Board of Ed., 345 F. 2d

329 (4th Cir. 1965) ...................................... ............... 33

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, 345

F. 2d 310 (4th Cir. 1964) .....................15,16,17, 32, 33, 39

Brooks v. County School Board of Arlington County,

Va., 324 F. 2d 303 (4th Cir. 1963) ............................ 11

Brooks v. School District of City of Moberly, Mo., 267

F. 2d 733 (8th Cir. 1959), cert, denied, 361 IT. S. 894 33

Browder v. Gayle, 352 IT. S. 903 ................... ................ 30

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 IT. S. 483, 349 U. S.

294 ........ ............. ...............2, 6,17,19, 27, 30, 31, 34, 39, 40

Bryan v. Austin, 148 F. Supp. 563 (E. D. S. C. 1957),

judgment vacated 354 U. S. 933 ................................ 36

Calhoun v. Latimer, 321 F. 2d 302 (5th Cir. 1963), va

cated and remanded 377 U. S. 263 .....................31, 32, 33

Ill

' PAGE

Christmas v. Board of Education of Harford County,

231 F. Supp. 331 (D. Md. 1964) ............................. . 33

Colorado Anti-Discrimination Commission v. Conti

nental Air Lines, 372 U. S. 714.................................... 30

Dawson v. Baltimore City, 350 IJ. S. 877 ....... ............. 30

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City Public

Schools, 219 F. Supp. 427 (N. D. Okla. 1963) ........... 33

Franklin v. County School Board of Giles County, Civil

No. 64-C-73-R, W. D. Va., June 3, 1965 ......... .........33, 36

Griffin v. Board of Supervisors, 339 F. 2d 486 (4th Cir.

1-964) .............. 33

Griffin v. School Board of Prince Edward County, 377

U- S. 218 ................................................................... 6,30

Holmes v. Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879 ................................ 30

Jackson v. School Board of the City of Lynchburg,

321 F. 2d 230 (4th Cir. 1963) ................................. . 33

Johnson v. Virginia, 373 TJ. S. 61 ................................ 30

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 ....................................... 17

Lawrence v. Bowling Green, Ky. Board of Education,

Civil No. 819, 8 Race Rel. L. Rep. 74 (N. D. Ky. 1963) 33

Manning v. Board of Public Instruction of Hillsbor

ough County, Fla., Civil No. 3554, 7 Race Rel. L. Rep.

681 (S. D. Fla. 1962) ................................................... 33

Mapp v. Board of Education of City of Chattanooga,

319 F. 2d 571 (6th Cir. 1963) .................................... 33

IV

PAGE

Mason v. Jessamine County, Ky. Board of Education,

Civil No. 1496, 8 Race Eel. L. Rep. 75 (E. D. Ky.

1963).......................... ...... ............................. .............. 33

McLanrin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637 40

Nesbit v. Statesville City Board of Education, 232 F.

Supp. 288 (W. D. N. C. 1964), vacated 345 F. 2d 333

(4th Cir. 1965) ........................................................... 33

Northcross v. Board of Education of Memphis, 333 F.

2d 661 (6th Cir. 1964) ................ .............................. 33

Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U. S. 244 ............................ 30

Price v. The Denison Independent School District,

----- F. 2 d ----- (5th Cir. No. 21,632, July 2, 1965) 18

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U. S. 479 .................................... 36

Taylor v. Board of Education, 191 F. Supp. 181 (S. D.

N. Y. 1961), aff’d 294 F. 2d 36 (2nd Cir. 1961), cert.

denied, 368 U. S. 940 .......................................... ........ 28

Tillman v. Board of Instruction of Volusia County,

Florida, Civil No. 4501, 7 Race Rel. L. Rep. 687 (S. D.

Fla. 1962) ..................................... ............................... 33

Turner v. Memphis, 369 U. S. 350 ................................ 30

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education,----- F.

2d----- (4th Cir. No. 9630, June 1, 1965) ......... ........... 33

Statutes:

Ala. Acts 40, 41, 1956 1st Sp. Sess.................................. 36

Ala. Acts 239, 361, 1957 Sess.......................................... 36

Ala. Acts 249, 383, 443, 1961 Sp. Sess........................... 36

V

Code of Va., 1950 (1964 Replacement Vol.), §22-205 32

Code of Ya., 1950 (1964 Replacement Vol.), §22-207 32

F. R. Civ. Proc., Rule 23(a) ......... 3

La. Acts 1956, Acts 248, 249, 250, 252 ............................ 36

S. C. Acts 1956, Act 741, repealed by Act 223 of 1957 .... 36

U. S. Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment, Sec. 1.......2,10

28 U. S. C. §1254(1) ...................................................... 2

28 IT. S. C. §1331 .............................................................. 3

28 U. S. C. §1343 .................................. 3

42 IT. S.C. §§1981, 1983 .................................................. 3

42 IT. S. C. A. §2000d.............................................. 18, 37, 38

PAGE

Other Authorities:

Brief of United States as Amicus Curiae, Calhoun v.

Latimer, 377 U. S. 263 ........... ................................... 31, 32

1960 Census of Population, Vol. 1, “Characteristics of

the Population,” Part I, U. S. Summary Table 230 36

110 Cong. Rec. 6325 (daily ed. March 30, 1964) .......... 18, 38

Fiss, “Racial Imbalance in the Public Schools: The

Constitutional Concepts”, 78 Harv. L. Rev. 564 (1964) 28

General Statement of Policies Under Title VI of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 Respecting Desegregation

of Elementary and Secondary Schools, HEW, Office

of Education, April 1964 ..................... ..........18,19, 37, 38

Lamanna, Richard A. “The Negro Teacher and Deseg

regation”, Sociological Inquiry, Vol. 35, No. 1, Winter

1965 ........................................ ..................................... 36

Y1

PAGE

Southern Education Reporting Service, “Statistical

Summary of School Segregation-Desegregation in

the Southern and Border States”, 14th Rev., Nov

1964........................................................................... - ...................................................................... .. .................................................................................... 35

Southern School News, May 1965 ................ ............... 18

Isr the

irtprpmp (Hmtrt 0! % IttiM States

O ctober T erm , 1965

No.................

R en ee P atrice G illia m , et al.,

Petitioners,

—v.—■

S chool B oard op t h e City of H opew ell ,

V irg in ia , et al.,

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit entered in the above-entitled cause on

April 7,1965.

Citations to Opinions Below

The memorandum opinion of the District Court of July

11, 1963 (R. 1-43)1 is unreported and is printed in the

1 The record contains Volumes I to VI. Each volume begins with

a page numbered 1. Thus record citations herein are to the volume

and page number; the text above indicates Volume I, page 43.

There is an additional transcript of a hearing March 23, 1964

(Testimony of Charles W. Smith) which is cited herein as “Smith

Tr.” (see Note 13, infra).

2

appendix hereto, infra, p. la. The opinion of the Court of

Appeals issued May 25, 1964 (E. 1-77), printed in the ap

pendix hereto, infra, p. 15a, is reported at 332 F. 2d 460.

Further unreported oral opinions of the District Court on

April 6, 1964 (R. IV-23) and July 2, 1964 (R. V-42),

appear in the appendix below at pages 9a and 22a, re

spectively. The second opinion of the Court of Appeals

dated April 7, 1965 (R. VI-5), printed in the appendix,

p. 27a, infra, is reported in 345 F. 2d 325.

J u r is d ic t io n

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

April 7, 1965 (R. VI-16; appendix, p. 37a, infra). Mr. Jus

tice Goldberg on June 28, 1965 extended the time for filing

the petition for certiorari until August 1, 1965. The juris

diction of this Court is invoked under 28 U. S. C. Section

1254(1).

Q u estio n s P re se n te d

1. Whether the Hopewell, Virginia school assignment

plan based on geographic attendance areas is inadequate

under Brown v. Board of Education, on the ground that it

substantially preserves a segregated situation which was

created by racial gerrymandering and related practices,

and was not remedied by the board’s inadequate pupil

transfer rule? 2

2. Whether Negro pupils seeking desegregation of a

public school system under Brown v. Board of Education

are entitled to relief against a practice of segregating

teachers on the basis of the race of pupils ?

3

Statutes and Constitutional Provisions Involved

This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

Statement of the Case

This case involving racial segregation in the public schools

of the City of Hopewell, Virginia, was filed October 17,

1962, by petitioners, a group of Negro parents and children,2

who invoked the jurisdiction of the United States Distinct

Court for the Eastern District of Virginia seeking equitable

relief pursuant to 28 U. S. C. §1343 and 42 U. S. C. §§1981

and 1983.2 3 Petitioners sought an injunction against the

city school board and superintendent and against the Vir

ginia Pupil Placement Board, a state agency with statutory

responsibilities concerning the assignment of pupils. Peti

tioners here seek review of the adequacy of a school board

desegregation plan which was approved below after nu

merous hearings in the trial court and two appeals.

The complaint, brought as a class action under Rule

23(a), P. R. Civ. Proe., alleged inter alia that the school

board “maintains and operates a bi-racial school system in

which certain schools .. . are designated for Negro students

only and are staffed by Negro personnel and . . . certain

schools . . . are designated for white students and are

staffed by white personnel” ; that the defendants had not

2 The original plaintiffs were 9 children attending the public

schools and their parents. Fifteen other pupils and their parents

subsequently joined as intervenors.

3 The complaint also alleged “federal question” jurisdiction

under 28 U.S.C. §1331.

4

devoted efforts to initiate desegregation or made a start

to effectuate a transition to a racially nondiscriminatory

school system; that children were routinely assigned to

schools on a racial basis; and that Negro children, includ

ing plaintiffs, who applied to white schools were refused

enrollment on a discriminatory basis (R. 1-2-12).

The complaint requested an order requiring admission

of the 9 minor plaintiffs in specified all-white schools and

more generally applicable injunctive relief against the seg

regated system and discriminatory practices. It included a

request that the court enjoin defendants “from operating

a biracial school system” or require them to submit a plan

for “reorganization of the schools on a unitary nonracial

basis” (R. 1-11). The school authorities generally denied

that the Negro children were entitled to relief (R. 1-15, 17).

The case was tried before Hon. John D. Butzner4 * and on

July 11, 1963, Judge Butzner filed an opinion (R. 1-45) and

entered an injunction requiring admission of the 9 pupils

as requested, and enjoining further use of racially dis

criminatory criteria including the established attendance

areas (R. 1-54). The order invited the local authorities to

submit a desegregation plan to the Court and stated that

the general injunction would be suspended upon approval of

a plan (ibid.).

At trial it was established that Hopewell’s 905 Negro

students and 40 Negro teachers were completely segregated

from the 3,530 white pupils and 133 white teachers in the

8 schools of the system. The white pupils and staff were

assigned to three elementary schools and one high school

4 The transcript of this first hearing on June 10, 1963, is Vol. I l l

of the record.

5

and the Negroes were assigned to three different elementary

schools and a high school as indicated in the margin.5 Negro

pupils who sought admission to white schools in 1960 and

in 1962 were denied transfers.6 Pupil assignments were

made on the basis of a geographical attendance area map

adopted in 1942 and occasionally modified thereafter.7

The map designated 6 attendance areas for the 6 ele

mentary schools; three areas were all-white and three were

all-Negro. Superintendent Smith testified that the boun-

5 The following chart was furnished by the school board Decem

ber 4, 1962, in response to an interrogatory (R. 1-25) :

No. No. No. No.

White Colored White Colored

School Capacity Pupils Pupils Teachers Teachers

Patrick Copeland

Elementary

Harry E. James

740 770 0 26 0

Elementary 330 0 167 0 7

Arlington Elementary 270 0 195 0 10

Dupont Elementary 870 832 0 29 0

Woodlawn Elementary

Carter G. Woodson

720 649 0 24 0

Elementary

Carter G. Woodson

300 0 286 0 9

High School 350 0 257 0 14

Hopewell. High School 1075 1279 0 54 0

The school board’s chart shows not only the pattern of student

and faculty segregation, but also that the uniformly smaller Negro

schools were under-utilized as compared to the large white schools

which were either overcrowded or almost filled.

6 Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 8 lists seven 1960 applicants. With respect

to 1962 applicants see complaint, para. 12 and schedule “A” (R.

1-8, 13-14.),; Answer of Pupil Placement Board (R. 1-17, 18); and

Testimony of E. J. Oglesby (R. III-46-53).

7 The board asserted that for many years pupils were assigned

on the basis of attendance areas (R. 1-26). A map showing these

areas as then established is marked as Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 7

(R. III-6).

6

daries had not ever been fixed to permit Negro and white

children to attend the same schools (R. III-12). All high

school pupils living in the areas of the 3 Negro elementary

schools (Arlington, Woodson and James) were assigned to

the all-Negro Woodson High School and all pupils in the

3 white elementary zones (Woodlawn, Dupont and Cope

land) were assigned to Hopewell High School (R. III-32-

33).

All eight school buildings were constructed or acquired

during this period of complete segregation.8 The trial

court’s injunction against the continued use of this set of

attendance areas was based upon findings that the boun

daries had been, for the most part, established prior to

Brown; that the prescribed areas “follow the distribution

of Negro and white residences in the city” ; that some areas

had “natural boundaries” but “in others there is no dis

tinction other than the racial composition of the neighbor

hoods” (R. 1-45) ; and that the school capacity and atten

dance figures provided “no rational criterion for the boun

daries” (R. 1-47). No Negroes lived in any of the white

school zones. The few white children living in the area of

a Negro school had in the past been granted transfers to a

white school in another area (R. III-35-36, 40-41).

8 Virginia’s massive resistance laws purported to require com

plete segregation and the closing of any desegregated schools until

1959. See a brief discussion of the massive resistance program in

Griffin v. School Board, 377 U. S. 218, 221. The most recently

constructed schools in Hopewell are the all-Negro Woodson Ele

mentary and Woodson High Schools occupied in 1958 (R. III-1Q-

11). The principal area served by Woodson Elementary School

was a white residential neighborhood until about 1957 when Wood-

son School was begun and the whites moved away (R. IV-18-19).

Before Woodson was constructed white children in the area at

tended the Dupont School across the railroad tracks to the north

(ibid.).

7

No one appealed the July 11, 1963 injunction. However,

on September 4, 1963, fifteen more Negro pupils moved to

intervene and for further injunctive relief asserting that

they had been refused admission to white schools in viola

tion of the injunction (R. 1-56-64). The Court heard evi

dence September 12, 1963,® and ruled that since no de

segregation plan had been presented or approved the 15

intervenors wTere entitled to the requested transfers (R.

IT-41-48).

Thus, the first desegregation of regular classes in Hope-

well took place in September 1963 when 26 or 27 Negro

children entered two white schools.9 10 The group included

24 petitioners (plaintiffs and intervenors) and 2 or 3 others

living in the same neighborhoods (R. IY-12). The racially

segregated pattern of school staffing continued unchanged

(ibid.).

The school authorities appealed the September 13, 1963,

order requiring admission of the 15 intervenors to white

schools (R. 1-66).11 The trial court had set dates for the

filing of a desegregation plan, objections to the plan, briefs

and a hearing (R. 1-67). Proceedings relating to the de

segregation plan continued in the trial court while the

appeal was being considered. On May 25, 1964, the .Court

of Appeals, voting 4-1, dismissed the appeal as moot on

9 See Record Volume IT.

10 Two of the plaintiffs had attended summer school at Hopewell

High School in 1963 (R. 11-19-20, 23-24). In September 1963

plaintiffs enrolled at Hopewell High and Copeland Elementary

schools.

11 The hearing was conducted as one for a temporary restraining

order (R. II-2), but a permanent order was entered upon, agree

ment that the court could finally decide the matter (R. 1-66).

the ground that the academic year was nearly ended and

that assignments for future years could be governed by the

plan being considered in the trial court or a further interim

order (R. 1-77-81; 332 F. 2d 460).12

Meanwhile, during this appeal, the school board filed its

first “Plan for Operation of Schools” and a motion to dis

solve the injunction on October 21, 1963,13 14 and the Court

held a hearing on March 23“ and April 6, 1964,15 and re

jected the proposed plan (R. IV-23-29).

The October 21, 1963, plan provided basically for assign

ments of pupils on the basis of a new attendance map (De

fendant’s Exhibit l )16 which made three changes of the

boundaries on the prior map (Pi’s Exhibit 7).17 First, the

boundary between the Patrick Copeland (white) and Harry

“ Judge Bryan dissented arguing that the rejection of the 15

requests on residential and procedural grounds was “entirely

lawful” (R. 1-82).

13 The motion and plan as well as the attached map of proposed

school zones may be found in that portion of the record on file

in this Court which contains the exhibits. They are all marked

Defendants’ Exhibit 1 (DX-1). The school zone map (DX-1), is

the one now in use. (The original map on file with this Court may

be found folded flat with the other exhibits; it is not one of the

rolled maps in the file.) A black and white photographic reproduc

tion of this large multi-color map is at the end of the appendix

hereto, infra.

14 The March 23, 1964, transcript (Testimony of Charles W.

Smith) was printed in Appellee Appendix in the Court of Appeals,

but the original was by error omitted from the record. It has been

filed in this Court by stipulation. It is cited as “Smith Tr.”

' 15 Record Volume IV.

16 See Note 13 supra; also the map at appendix hereto infra.

17 Transcript of hearing on March 23, 1964, “Testimony of

Charles W. Smith” (hereinafter cited as “Smith Tr.”), pp. 13-16.

9

E. James (Negro) elementary schools was altered to con

form to a railroad line placing about 51 Negro children in

the Copeland area (Smith Tr. 14).18 Second, the board

changed a short portion of the boundary between Woodlawn

(white) and Arlington (Negro) schools. This change was

said to have incorporated three white homes into the Arling

ton zone (R. IV-14-15), but the Superintendent did not

know whether this placed any white school children in the

Negro school area (Smith Tr. 15). Third, the boundary was

changed between the Dupont (white) and Woodson (Negro)

schools to add a small triangular shaped enclave containing

white homes (area bounded by railroad tracks in two direc

tions and 15th Avenue) to the Woodson zone (Smith Tr.

16). The five white children in this area either moved or

went to private schools -when placed in the Negro zone (R.

IV-13).

The plan continued the same pattern of high school as

signments based on elementary school zones; pupils in the

two all-white zones (Woodlawn, Dupont) and one predomi

nantly white zone (Copeland) were assigned to Hopewell

High and those in the 3 all-Negro zones (James, Arlington

and Woodson) to Woodson High. The plan had two trans

fer provisions. One stated that transfers would be granted

for “some specific reason,” giving as an example the trans

portation convenience of a handicapped child, and that race

would not be a factor in granting or refusing such transfers.

The second, an explicitly racial provision, allowed transfer

18 The earlier boundary between Copeland and James was a

winding line between Negro and white residences which made

approximately 20 turns and moved back and forth, across a rail

road line. Compare the first map, Pi’s Ex. 7, with the second map,

DX-1.

10

of “any colored child, assigned by reason of residence to a

school in which he is in the racial minority” to an all-Negro

school if both his parents and the board thought the non-

segregated assignment was “detrimental” to the child. This

latter provision was made severable in the event that the

court thought it unconstitutional.

To summarize, the net effect of the plan was to permit

a total of 51 Negro children to attend Copeland Elementary

School or Hopewell High School and to leave the racial

composition of the two other white schools and the four

Negro schools unchanged.

Petitioners objected to the plan as inadequate and in

valid under the Fourteenth Amendment on various grounds,

including an objection to the map asserting that it was “an

attempt to continue the discrimination previously enjoined”

(E. 1-74-75). This pleading also asserted that “the plan as

a whole is inadequate in that it fails to make provision for

the assignments or reassignments of teachers and other

professional personnel on a nonracial basis” (R. 1-75).

As previously noted the trial court rejected the plan

April 6, 1964 (R. IV-23-29). The court noted that all pupils

in the 3 white elementary zones were assigned to Hopewell

High and all in the Negro zones to Woodson High; that

the Hopewell enrollment exceeded its capacity while the

Woodson enrollment did not ;19 and that white children from

the Woodlawn zone “have to go a considerable distance

19 The finding was based on Plaintiffs’ Exhibit la indicating in

part:

September 1963 Capacity Enrollment

Hopewell High 1,075 1,358

Woodson High 350 277

11

farther to Hopewell High School than if they were assigned

to the Carter G. Woodson High School” and also “have to

cross more railroad tracks and highways” (E. IV-26-27).

The Court also criticized the Arlington and Woodlawn

boundary stating (R. IV-27):

The area adjacent to the Arlington School zone,

which presently feeds into the Woodlawn School, is

predominantly white. The line has been drawn sep

arating the predominantly white neighborhood from

the predominantly Negro neighborhood.

= » # # # #

The primary responsibility is, the Court recognizes

for the School Board to draw these lines. But when

it ends up, as it does, with a completely segregated

school system, the Court is of the opinion that the

language of the Court of Appeals in the Brooks case

is pertinent. [Court then read from Brooks v. County

School Board of Arlington County, Va., 324 F. 2d 303,

308 (4th Cir. 1963).]

Two months later (June 4, 1964) the board filed an

amended plan using the very same attendance areas which

had been filed with the first plan and rejected on April 6,

1964 (E. 1-84-86). But the new plan provided that elemen

tary pupils in the Woodlawn and Arlington zones might

transfer if “their residence is nearer an elementary school”

outside their zone of residence (R. 1-85). The plan also

stated that high school students could transfer out of their

zones if their “residence is nearer a high school other than

the one to which” they are initially assigned (E. 1-85). The

racial minority transfer rule for Negro children was omitted

12

from the amended plan. Petitioners objected to the plan,

basically adopting their exceptions to the first plan (E.

1-95).

An examination of the attendance area map (Defendants’

Exhibit 1 ; see appendix infra) shows at a glance that no

part of the Negro Arlington area is nearer to the white

(Woodlawn) school than to Arlington, although white resi

dences in the Woodlawn zone are closer to Arlington than

to Woodlawn since a portion of the Woodlawn zone is

within 1 block of Arlington school.20 Similarly, parts of

Woodlawn zone are closer to the Negro Woodson High

School than to Hopewell High but the Negro school zones

are all closer to Woodson High than to Hopewell High

(R. IV-26-27).

At a hearing on the amended plan (July 2, 1964; E.

Volume V) the board filed the affidavit of Superintendent

Smith (R. 1-89) stating that the boundaries were the same

as those previously submitted and that a survey showed that

boundary changes suggested by petitioners’ counsel to the

school board would Overcrowd Arlington and Woodson

schools.21 The affidavit also reported “expected enroll

ments” for several schools in September 1964 and some

20 See Def’s Ex. 1. See also, testimony at the original trial at

R. III-31.

_ “ Petitioners did not propose any boundaries to the Court. They

did suggest to the school board possible modifications of zones to

include white pupils in 3 under-capacity Negro school zones, but

did so tentatively without benefit of any survey of pupil residences.

The school board did not present any data relating to the feasibility

of any intermediate boundaries between its proposals and plain

tiffs’ suggestions.

13

new arrangements of classes.22 No evidence other than the

affidavit was offered at the hearing on the new plan (R.

Volume V).

22 In order to make the enrollment, and capacity figures more

readily available and comprehensible, the following data is ex

tracted from various exhibits, affidavits, etc.:

a. 1962-63 school year, see note 5, supra;

b. 1963-64 school year (September 1963); from plaintiffs’ ex

hibit 1-A (4-6-64) (same document also marked Def’s Exhibit

5):

Pupil-Teacher

School Capacity Attendance Ratio

Woodlawn 720 667 27.8

Dupont 870 858 30.1

Copeland 720 780 30.0

Hopewell High 1,075 1,358 31.5

Woodson High 350 277 19.7

James 300 150 15.0

Arlington 270 190 21.1

Woodson Elementary 300 280 28.0

c. Estimates for 1964-65 school year; from Smith affidavit (R.

1-89-94) indicating “expected” enrollments:

School Capacity “Expected Attendance”

Woodlawn 720 712

Dupont 870*** 858***

Copeland 720 780***

Hopewell High 1,250* 1,440

Woodson High 400** 250

James 300 ■ 150***

Arlington 270 234

Woodson Elementary 240** 220

* Capacity increased by use of increased number of teaching

periods; no new classrooms.

** Shift of 2 rooms from elementary to high school use changed

capacities,

*** Figure based on previous year; no newer data supplied.

14

After hearing arguments23 the trial court approved the

school board’s amended plan24 stating:

The chief difference between the situation that now

exists and that which existed at the hearing this spring

when the Court declined to approve the plan is that the

new plan submitted by the Board provides for transfer

of Arlington or Woodlawn Elementary pupils to any

school nearer a pupil’s residence. It also provides that

high school students may transfer from the Hopewell

High or Woodson High, as the case may be, to the

high school which is nearer their residence.

# # # # #

The Court finds that the School Board has attempted

in good faith to create zones consistent with the capac

ity and attendance of the schools, and the Court be

lieves that the plan which has been suggested is con

sistent with the suggestion made by the Court of Ap

peals pertaining to some other assignment method in

the unsettled zones (R. V-44-45).

The Court ruled that the 24 Negro children assigned to

white schools by prior court order could continue in those

schools notwithstanding the fact that they lived in all-

Negro zones, and entered an order approving the plan, dis

solving the injunction and retaining the cause on the docket

(R. 1-97-98).

Petitioners appealed the order approving the plan and

dissolving the injunction and the School Board cross-

23 The faculty desegregation issue was argued by plaintiffs (R.

V-33-36).

24 The oral opinion is at R. V-42-45.

appealed the order allowing the Negro litigants to continue

in the white schools (R. 1-99,101).

The Fourth Circuit, en banc, affirmed on both appeals

(345 F. 2d 325). The opinion of the Court by Judge Hayns-

worth said the trial court was justified in concluding that

the boundaries were “reasonably drawn in accordance with

natural geographic features and not on racial lines,” that

“de facto segregation” resulted from the residential pat

terns and that assignment by fair zones was constitutional.

The Court affirmed the failure of the District Court to enter

an order against faculty segregation citing its contempo

raneous decision in Bradley v. School Board of the City of

Richmond, 345 F. 2d 310 (4th Cir. 1964), where it said that

pupils have standing to raise the issue to the extent it in

volved an asserted denial of their rights, but that the issue

was ignored below and there was “no inquiry as to the pos

sible relation, in fact or in law, of teacher assignments to

discrimination against pupils” or of the impact of such an

order. It said that the District Court had “a large measure

of discretion” concerning “whether and when” to make an

inquiry into faculty desegregation (345 F. 2d at 320).

The Fourth Circuit upheld the order permitting plain

tiffs to remain in the schools they had entered under the

earlier court orders notwithstanding this was inconsistent

with the zoning plan saying that the trial court had a dis

cretion to make such exceptions “as fairness and justice

seem to it to require.” Judge Bryan dissented in part argu

ing that the plaintiffs should be retransferred to the schools

in their zones (345 F. 2d at 329).

Judges Sobeloff and Bell concurred separately agreeing

that zone boundaries drawn without racial discrimination

16

may be accepted, bat noting that “the size and location of

a school building may determine the character of the neigh

borhood it serves” and that the school board “must keep in

mind its paramount duty to afford equal educational oppor

tunity to all children without discrimination; otherwise

school building plans may be employed to perpetuate and

promote segregation” (345 F. 2d at 329). Judges Sobeloff

and Bell also stated that their concurrence was subject to

the views expressed in their separate opinion of the same

date in Bradley v. School Board of the City of Bichmond,

345 F. 2d 310, 321.

In that case they dissented from the failure of the court

to order desegregation of teaching staffs:

The composition of the faculty as well as the com

position of its student body determines the character

of a school. Indeed, as long as there is strict separa

tion of the races in faculties, schools will remain

“white” and “Negro,” making student desegregation

more difficult. The standing of the plaintiffs to raise

the issue of faculty desegregation is conceded. The

question of faculty desegregation was squarely raised

in the District Court and should be heard. It should

not remain in limbo indefinitely . . . (345 F. 2d at 324).

17

Reasons for Granting the Writ

The approval of Hopewell’s desegregation plan by the

courts below presents questions of general public im

portance bearing on the extent to which the principle of

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 349 TJ. S. 294,

will be implemented in the states which have required public

school segregation.

First, the case involves the adequacy of a school board’s

arrangements to satisfy its duty to disestablish a segregated

school system which it created over the years by racially

gerrymandering school attendance districts and related

practices. It is important that this Court deal with this

issue, even though it involves details of local assignment

practices, in order to guide and encourage the lower federal

courts to deal with the important detailed problems that

ultimately determine whether Brown is implemented in

any meaningful fashion vdiere a school board is recalci

trant. As some districts retreat from massive resistance

they may believe that segregation can be maintained by

“sophisticated” rather than “simple minded” (cf. Lane v.

Wilson, 307 U. S. 268, 275) techniques. To them it must

be shown that their ingenuity should be directed at achiev

ing compliance, not in avoiding it.

Second, there is a question on the level of principle rather

than that of implementation. Faculty segregation is a

matter of widespread concern in thousands of school sys

tems. The teacher segregation problem, also presented in

the companion petition for certiorari filed in Bradley v.

The School Board of the City of Richmond, supra, is a

18

matter which cries out for prompt resolution by this Court.

As we argue below, faculty segregation preserves the seg

regated all-Negro schools and prevents the creation of truly

nondiscriminatory school systems. The United States Com

missioner of Education in implementing Title VI of the

Civil Eights Act of 1964 (42 U. S. C. A. §2000d) has an

nounced in a general policy statement that “all desegrega

tion plans shall provide for the desegregation of faculty and

staff,” 25 but only a few courts have taken unequivocal

action. The Commissioner of Education is faced with the

problem of passing upon thousands of school district de

segregation plans within a very brief period of time. To

this end, he has established procedure whereby school

boards may qualify for aid by filing with his office either

an “Assurance of Compliance” (HEW Form 441), or a

final court order requiring desegregation, or an acceptable

plan for desegregation (General Policy Statement, supra,

II).

The failure of the school board herein to act with respect

to teachers apparently violates HEW requirements. More

over, if HEW were to review the desegregation plan in

operation in Hopewell it might disapprove of it. But the

25 General Statement of Policies Under Title VI of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 Respecting Desegregation of Elementary and

Secondary Schools, HEW, Office of Education, April 1964. The

document, hereinafter cited as “General Policy Statement” is re

printed in the appendix to Price v. The Denison Independent

School District,----- P. 2 d ------ - (5th Cir. No. 21632, July 2, 1965),

and in Southern School News, May 1965, pp. 8-9.

The Commissioner’s action is clearly in accord with the intent of

the legislative proponents of the Act. See the speech of Vice

President (then Senator) Humphrey introducing Title VI in the

Senate, clearly stating that the Commissioner can require “elimina

tion of discrimination in employment or assignment of teachers”

(110 Cong. Eec. 6325 (daily ed. March 30, 1964)).

19

“final court order” rule which HEW has adopted apparently

insulates Hopewell from its scrutiny. Moreover, the gen

eral policy of HEW has been to impose requirements com

parable to those required by the federal judiciary in the

area. It is in the national interest that a uniform rule be

announced by this Court.

I.

The Pupil Assignment Plan Approved Below Operates

to Minimize Desegregation and Is Not Adequate to Cor

rect Racial Segregation Created by Public Officials.

When this case commenced Hopewell’s public school

children were completely segregated by race in eight schools

established on a racial basis by the use of school attendance

areas adopted for the purpose of separating Negroes from

whites. After prolonged litigation the courts below ap

proved a plan sanctioning minimal changes. The approved

plan employs school zones only slightly different from those

used before, with the result that one formerly white ele

mentary school and one formerly white high school have

a few Negro pupils and the other schools remain as they

were before the suit.

The trial court ultimately approved a plan based on

attendance zones which it found were established on the

basis of race prior to Brown v. Board of Education, supra,

on the mistaken ground that a pupil transfer provision in

the plan would alleviate the situation in the “unsettled

zones” established for Woodlawn and Arlington Elemen

tary Schools and for Hopewell and Woodson High Schools.

Although the trial court had relied on the earlier Fourth

20

Circuit suggestion of some nongeograpliic assignment

method in these areas (see 332 F. 2d at 462), the Fourth

Circuit approved the plan on a different ground. It held

(we believe erroneously) that the trial court had found the

zones fair and nonracial, and added its own conclusion that

this was so. Both courts employed the term de facto seg

regation to describe the results of the plan, thus ignoring

the school board’s role in creating and continuing the seg

regated situation and excusing its failure to ameliorate the

situation it created.

The approved plan employed the very same school zones

which the trial court denounced three months before as

based on race resulting in segregation.26 The trial court

referred to the pupil transfer rules in the amended plan,

which were only applicable to the specific areas previously

criticized, as “the chief difference” between the plan ap

proved and the plan rejected earlier (R. V-44).

However, this difference in the form of the plan made

absolutely no difference in the results of the plan. The

transfer rule, applicable only to elementary pupils in the

Woodlawn and Arlington areas, and to high school pupils,

allowed transfers out of attendance areas only for pupils

who lived closer to a school outside their areas. The reality

—-as a glance at the map reveals—is that only white pupils

26 On April 6, 1964, Judge Butzner criticized the high school

zones and the Arlington-Woodlawn elementary zones. He specifi

cally said that the Arlington-Woodlawn boundary “line has been

drawn separating the predominantly white neighborhood from the

predominantly Negro neighborhood” (R. IY-27). Actually, the

Woodlawn zone was “entirely,” rather than “predominantly,”

white and there was no testimony that there w'ere any white school

children in the Arlington zone (Smith Tr. 15).

21

were so situated and no Negro pupils lived in areas where

they could use this transfer rule. If white pupils were

attempting to get transfers out of all-white schools to

attend schools with Negro pupils and all-Negro faculties,

the provision would indeed promote desegregation. But,

as is well understood, that situation does not exist in Hope-

well. Negroes were the ones who are seeking to end the

segregated pattern in Hopewell. Thus, it was totally un

reasonable to expect that any change in the racial composi

tion of the schools would occur because of this transfer rule.

The rule was meaningless because the Negroes who wanted

transfers could not get them and the whites who could get

transfers did not want them.

Considering the realities, it is not at all surprising that

the Court of Appeals barely mentioned the transfer rule

and placed little if any reliance on it to sustain the plan.

But there is considerable irony in this because although the

trial court had rejected the plan in the absence of the trans

fer feature, the Fourth Circuit approved the plan on the

ground that the zones were fair and nonracial and asserted

that the trial court supported this view.

There is no persuasive indication that the trial court on

July 2, 1964, modified its April 6, 1964, finding that the

zones were drawn on a racial basis to separate the Negro

and white residential areas. The later opinion expressly

embraced the earlier findings modifying them only to the

extent to mentioning new data estimating school enroll

ments for the affected schools in the forthcoming (Septem

ber 1964) term. There was no enrollment change which

could be thought to have supported a different conclusion,

since neither Arlington nor Woodlawn school was over

22

crowded at any time during the litigation, while the pattern

of overcrowding in the white high school and under-utili

zation of the Negro high school also continued throughout.27

It cannot be gainsaid that Judge Butzner repeatedly indi

cated that the transfer feature of the new plan, which he

conceived as consistent with the suggestion made by the

Court of Appeals in its first opinion, was the principal basis

for his approval of the plan. The one sentence in his oral

opinion which lends any support to the view that he ap

proved the zones was one in which he said that he thought

the board was trying in good faith to create zones con

sistent with school capacity and attendance. Yet in this

very sentence Judge Butzner again referred to the “un

settled zones” and the Fourth Circuit suggestion for

another assignment method in those areas.

In any event, there are a variety of reasons why the zones

should not have been approved by either the Fourth Circuit

or the trial court (if it did approve them). The controversy

focuses on the Woodlawn-Arlington Elementary boundary

and also on the high school attendance pattern. We shall

discuss them in that order, before reviewing several more

general problems relating to the obligation of a school board

to correct an unlawful system which it has created.

Throughout the case the Arlington-Woodlawn boundary

has effectively separated the Negro and white pupils living

on each side of the boundary between the two completely

segregated schools. The boundary was drawn for this pur

pose at a time when segregation was mandated by Virginia

27 See statistics for 3 consecutive school years bearing this out in

notes 5 and 22, supra.

23

law. Arlington, a small school at the western edge of the

City has served the small Negro population in that area.

Woodlawn, a larger school, serves the larger white popula

tion in the nearby area which comes within one block of

Arlington School. Arlington, like all of the Negro schools,

is much smaller than the white schools. None of the Negro

schools has enrolled or is built to accommodate even half

as many pupils as the smallest white school.

Although the Arlington area was based on race, the

boundary accomplished this without any ingenious classical

gerrymander. This boundary just ran along ordinary

streets that separated the Negro and white pupils’ resi

dences. True to its purpose, the boundary did zone white

pupils living just one block from the Negro school into a

white school more than a dozen blocks away (R. III-31).

But the racial residential pattern was such that there was

no need for a meandering line forming a classical gerry

mander with a grotesque shape.

Such a flagrant and obvious gerrymander in the classic

sense had been used in Hopewell to separate the James and

Copeland schools; the line meandered through 20 or more

turns back and forth across a railroad track to separate

Negro and white homes (see P i’s Ex. 7, the first zone map).

The change of this gerrymander was the only alteration of

the prior zones which has produced any actual desegrega

tion of a school. The only Negro pupils in Hopewell entitled

to attend a white school are approximately 51 children at

the eastern side of the City who live in the area changed

from James to Copeland. The high school pupils among

this group of 51 are in the Hopewell High School zone ac

counting for the only high school desegregation under the

plan.

24

The school board did make a slight change of the Arling-

ton-Woodlawn boundary; it straightened one portion of the

line which wound between Negro and white houses without

affecting the school population (Smith Tr. 15). This change

moved a short segment of the line from Arlington Road

one block west to Wall Avenue (ibicl.).

As noted, Judge Butzner condemned the boundary before

and after it was altered (R. 1-45; IV-27). But the Court

of Appeals said that the boundary was logical and rea

sonable because the court said it followed “a main arterial

highway” (345 F. 2d at 327). This determination that the

line followed a highway is obviously based on a misunder

standing of the testimony. The school board never really

claimed this, and the only trial court finding on the sub

ject tends to show the contrary, as does the testimony. At

the first trial, June 10, 1963, the superintendent, when

asked if there was any barrier between Arlington and

Woodlawn, replied: “No. There is no gully, ravine, that

soft of thing. There is a street” (R. III-43). There was

a finding to this effect (R. 1-47). After the new map was

adopted Superintendent Smith gave a great deal of testi

mony about this boundary in hearings on March 23 (Smith

Tr. 20-26) and April 6, 1964 (R. IV-2-8, 14-18, 19), and an

affidavit (R. 1-92). In all of this testimony there was no

claim that the boundary followed a main traffic route and

there is testimony to the contrary.28 There is a major road

28 Some of the streets which constitute the boundary are Old

Courthouse Road, Berry Street, Wall Avenue and Wall Street.

Superintendent Smith said Old Courthouse Road “is not a major

traffic artery, but it is used sometimes in getting to Route 36.. . .

for people who live in this area” (Smith Tr. 22). There was.no

testimony that Berry Street was a major traffic artery. At one

25

in the area, a four lane highway along Palm Street and

Plant Street (R. IV-16-17) which runs across the Wood-

lawn attendance area and across a small portion of the

Arlington area but does not serve as a boundary at all.

The school board in arguing the ease below has made

much of the fact that a boundary change proposed to the

board by petitioners would overcrowd Arlington School.

But the fact remains that large numbers of white pupils

do live closer to the Negro school, some of them within a

block of Arlington and more than a dozen blocks from

Woodlawn. The school board continues to assign them to

the white school, the Superintendent saying: “Woodlawn

School could hold them. There was no point taking them out

of there” (R. IV-19). While Arlington could not accom

modate every white pupil in the nearby area so long as the

present number of Negroes are assigned there it could

accommodate some of them. The number obviously de

pends on the number of Negroes living greater distances

from Arlington than the whites who are assigned to Arling

ton. The present number of Negroes at Arlington also

relates to the fact pupils in grades 6 and 7 in the Arlington

area were recently returned to Arlington from the Wood-

son School (Superintendent’s Affidavit, R. 91). The sum

of the matter is that the school board, faced with a variety

of courses of action, has consistently chosen the course of

point the Superintendent said he thought Wall Street was going

to be connected to Palm Street, an “arterial throughway” (Smith

Tr. 23-24). But he acknowledged that there was no existing

connection between Wall and Palm (Smith Tr. 24), subsequently

retracted the original statement by saying that Wall and Palm

would not connect (R. TV-3-4), and filed an affidavit that the con

nection might be at High Street and Palm (R. 1-92). So Wall

Street is not a highway, or connected to a highway, or even a

through street (Smith Tr. 25-26).

26

action which maintains Arlington and Woodlawn Schools

completely racially segregated. Petitioners submit that

something more than this is necessary to satisfy the board’s

constitutional duty to undertake to reform the segregated

situation which it deliberately created in the first place.

The high school attendance plan is even more patently

designed to maintain racial segregation. All pupils in the

areas of the three Negro elementary school zones are as

signed to Woodson High and all pupils in the two all-white

and one predominantly white elementary zones are assigned

to Hopewell High. The Fourth Circuit upheld the zones

based on the following reasoning: (1) The elementary

zones are reasonable; (2) the high school zones are com

binations of the elementary zones; ergo, (3) the high school

zones are reasonable. The court’s reasoning ignores the

critical facts that the secondary schools have different en

rollments, capacities, and locations than the various ele

mentary schools.

The result of the high school zoning is shocking. The

large white high school has been overcrowded consistently

and remains overcrowded even with the school program

altered by a special extended day operation to increase the

capacity of the building without adding more rooms. The

small all-Negro high school (about one-third the size of

the white school) is significantly under-utilized operating

on a regular school day basis.29 This pattern is not com

pelled by any topographic features and residential pat

29 The overcrowding at Hopewell High and under-utilization of

Woodson High has existed at least since 1960. See enrollment

statistics for November 1960 (Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 11) and September

1962 (Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 17c). The more recent enrollment data

appears in notes 5 and 22, supra.

terns. Large numbers of white pupils live closer to the

Negro high school than they do to Hopewell High. Some

of these white pupils traveling to Hopewell High from the

Woodlawn attendance area not only live closer to AVood-

son, but have to cross more railroad tracks and highways

to get to Hopewell. Judge Butzner so found (R. IV-26-27).

The school board, before the suit was filed, maintained

segregation by assigning all white children to Hopewell and

all Negroes to Woodson. Hopewell High School was built

in 1925 and expanded over the years to serve the white

high school population (R. III-ll). Carter G. Woodson

High School was planned, located and built for Negroes

during Virginia’s massive resistance e ra ; it opened in 1958

as an all-Negro school (R. I II- ll; IV-18-19). Woodson

was built to accommodate approximately one-fourth of the

pupils in a system where almost one-fourth are Negro,

and assigned an all-Negro staff. It was located on the edge

of the Negro ghetto, and white families in the area moved

away during its construction (R. IV-18-19). Thus, the

school segregation policy may have had a direct impact on

the residential pattern. Certainly, it is true that the segre

gation system at the high school level was reenforced and

concretized subsequent to the Brown decision by the erec

tion of a new all-Negro high school. The school’s location

and size facilitates segregation. The court-approved plan

allows a small number of Negro children living at the edge

of the ghetto (Copeland area) to attend the white high

school and leaves the pre-existing situation otherwise intact.

In discussing both high schools and elementary schools

the court below uses the term de facto segregation and

cites Bell v. School City of Gary, Indiana, 324 F. 2d 209

(7th Cir. 1963), cert, denied 377 U. S. 924, a case involving

distinct issues in a northern community. Whatever may

be the constitutional obligation of school systems with

racially imbalanced schools caused by varied conditions and

policy decisions (see generally, Fiss, “Racial Imbalance in

the Public Schools: The Constitutional Concepts,” 78

Harv. L. Rev. 564 (1964)), this case presents the signifi

cantly different problem of a segregated school system

which was carefully and deliberately established as such

over a period of years under Jim Crow laws compelling

segregation. The issues here relate to the duty of a school

system to take the action necessary to eliminate the effects

of its own deliberate and long sustained deliberate segrega

tion policies. Segregation in Hopewell was actively fostered

by locating schools of particular sizes on particular sites

to accommodate Negro pupils (and only Negro pupils) and

by drawing school zones to embrace the Negro population.

Hopewell’s case is much like that of New Rochelle, New

York, where the courts required steps to undo the effects

of past racial gerrymandering and transfer policies. Taylor

v. Board of Education,. 191 F. Supp. 181 (S. D. N. Y.

1961), aff’d 294 F. 2d 36 (2nd Cir. 1961), cert, denied 368

IJ. S. 940. The differences are that Hopewell’s segrega

tionist practices were open, compelled by law and much

more recent than the gerrymandering in New Rochelle

which was covert and occurred many years before the law

suit.

Whatever might be said of Hopewell’s geographic zoning

plan for assigning pujuls if it were appraised hypothetically

in another context where there was no history of compul

sory segregation, this case should be decided in its factual

context against the background of school planning and

manipulation to foster segregation. Against that back

ground it is reasonable to judge the plan by its results. A

plan which leaves the four all-Negro schools completely

segregated, and allows only about 50 Negro pupils to attend

two of four white schools, plainly has not been adequate

to eliminate the segregated situation created by past prac

tices. Hopewell has exerted every effort to keep desegre

gation to a minimum, including twice appealing to the

Court of Appeals to remove Negroes from white schools.

The courts below have allowed Hopewell’s board to succeed

in minimizing desegregation by giving approval to the plan

of geographic areas organized on a racial basis around

schools located for Negroes. The artificiality of the present

system is made entirely plain when one contemplates the

fact that not one of the Negro schools has even one-half

as many pupils as the smallest white school. The continu

ance of segregation cannot be justified by topography or

alleged natural barriers such as railroad tracks which were

ignored frequently in constructing zones to accomplish seg

regation prior to the lawsuit. Nor can school segregation

be passed off as an inevitable consequence of residential

patterns where schools have been deliberately established

so as to conform exactly to the segregated housing pattern;

30

II.

S e g reg a tio n o f P u b lic S choo l F a c u ltie s V io la tes th e

F o u r te e n th A m e n d m e n t a n d S h o u ld B e A b o lish ed .

We submit that the courts below have erred in refusing

to require Hopewell’s public school authorities to end the

practice of assigning all white teachers to white schools

and all Negro teachers to Negro schools. Petitioners’ view

is that this segregationist practice of hiring and placing

public school teachers on a racial basis is unconstitutional

per se and has not the slightest justification under the

Constitution. In a long series of cases since Brown this

Court has invalidated state requirements of segregation in

every context in which they have appeared.30

The only possible justification for withholding relief in

this case is that petitioners who are public school pupils

are not entitled to invoke the aid of the courts to halt the

admittedly unlawful practice. Petitioners submit that the

30 In a unanimous opinion this Court said:

“ . . . [U]nder our more recent decisions any state or

federal law requiring applicants for any job to be turned away,

because of their color would be invalid under the Due Process

Clause of the Fifth Amendment and the Due Process and

Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.”

Colorado Anti-Discrimination Commission v. Continental Air Lines,

372 U. S. 714, 721.

See also, Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U. S. 61 (courtroom); Bailey

v. Patterson, 369 U. S. 31 (transportation) ; Peterson v. Greenville,

373 U. S. 244 (restaurant) ; Turner v. Memphis, 369 U. S. 350

(airport restaurant) ; Browder v. Gayle, 352 U. S. 903 (buses);

Griffin v. School Board of Prince Edward County, 377 U. S. 218

(schools) ; Dawson v. Baltimore City, 350 U. S. 877 (municipal

beaches) ; Holmes v. Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879 (municipal golf

courses).

31

unlawful practice is closely linked to their right under

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 297, to have the

district courts supervise the effectuation of “a racially non-

diseriminatory school system” (349 U. S. at 301, emphasis

added). The Court in deciding the second Brown case,

supra, pointed to administrative problems related to “the

physical condition of the school plant, the school transpor

tation system, personnel, revision of school districts and

attendance areas into compact units to achieve a system of

determining admission to the public schools on a nonraeial

basis, and revision of local laws and regulations . . . ”, as

matters to be considered in appraising the time necessary

for good faith compliance (emphasis added). We believe

that the Court plainly regarded the task as one of ending

all discrimination in school systems, including “personnel”

as well as discrimination in the transportation system, at

tendance districts or the other factors mentioned. The de

lay countenanced by the “deliberate speed” doctrine was

predicated on the assumption that dual school systems

would be reorganized.

The brief of the United States, as amicus curiae, in

Calhoun v. Latimer, 377 U. S. 263, argued in this Court

that:

Obviously, a public school system cannot be truly non-

discriminatory if the school board assigns school per

sonnel on the basis of race. Full desegregation can

never be achieved if certain schools continue to have

all-Negro faculties while others have all-white faculties.

Schools will continue to be known as “white schools”

or “Negro schools” depending on the racial composi

tion of their faculties. It follows that the school au

thorities must take steps to eliminate segregation of

32

personnel as well as pupils. (Brief of the United

States, pp. 39-40.)

The Court in Calhoun vacated the judgment without dis

cussion of this issue. We submit that this case presents an

appropriate occasion to consider this question.

Faculty segregation was an integral part of the segre

gated school systems maintained under the separate but

equal doctrine. It was the well-known general practice that

Negroes taught only Negroes and whites taught only whites.

Virginia law encourages teacher segregation by providing

that teachers may terminate their contracts when pupils

are desegregated “or both white and Negro teachers shall

have been employed in the school to which the contracting

teacher is assigned.” 31

An all-Negro faculty is as sure an indicator that a school

is a “Negro” school as a racial sign over its door. Judges

Sobeloff and Bell were plainly right in their dissent in the

Richmond school case32 where they said that “composition

of the faculty as well as the composition of its student body

determines the character of a school,” and that with “strict

separation of the races in faculties, schools will remain

'white’ and ‘Negro,’ making student desegregation more

difficult.” 33

31 Code of Va., 1950, §22-207 (1964 Replacement Vol.). The

above-quoted provision encouraging faculty segregation was

adopted in 1962. (Va. Laws 1962, c. 183.) Under Virginia law

division school superintendents have authority to assign and re

assign teachers. Code of Va. 1950, §22-205.

32 Bradley v. School Bd. of City of Richmond, Va., 345 F 2d

310, 324 (4th Cir. 1965).

33 Id. at 324.

33

But the Fourth Circuit has not stated its clear disap

proval of faculty segregation in any of the cases in which

it has considered the matter34 and apparently has adopted

the view that faculty desegregation must depend upon some

kind of evidentiary showing by plaintiff Negro pupils that

34 Faculty segregation was first considered by the Fourth Circuit

in Jackson v. School Board of the City of Lynchburg, 321 F. 2d

230, 233 (4th Cir. 1963), where it held that a complaint asking

for desegregation of a school system was sufficient to raise the

question. See also, Griffin v. Board of Supervisors, 339 F. 2d 486,

493 (4th Cir, 1964) ; Bowditch v. Buncombe County Board of Ed.,

345 F. 2d 329, 332, 333 (4th Cir. 1965) ; Wheeler v. Durham City

Board of Education,----- F. 2 d -------(4th Cir. No. 9630, June 1,

1965), and, of course, the Bradley ease, supra, and the instant case.

In the Fifth Circuit see: Board of Public Instruction of Duval

County v. Braxton, 326 F. 2d 616, 620 (5th Cir. 1964), cert, denied

377 U. S. 924 (affirming a trial court order requiring a faculty

desegregation plan). See also Augustus v. Board of Public Instruc

tion of Escambia County, 306 F. 2d 862 (5th Cir. 1962); Calhoun

v. Latimer, 321 F. 2d 302 (5th Cir. 1963), vacated and remanded

377 U. S. 263.

The Sixth Circuit has twice held that it was proper for pupils

and their parents to raise the issue of segregation of teachers.

Mapp v. Board of Education of City of Chattanooga, 319 F. 2d 571,

576 (6th Cir. 1963) ; Northcross v. Board of Education of City of

Memphis, 333 F. 2d 661, 666 (6th Cir. 1964).

Several other courts have discussed the question of segregation

of teachers with a variety of results. Brooks v. School District of

City of Moberly, Mo., 267 F. 2d 733 (8th Cir. 1959), cert, denied

361 U. S. 894 (1959); Franklin v. County School Board of Giles

County, Civil No. 64-C-73-R, W. D. Va., June 3, 1965; Christmas

v. Board of Education of Harford County, 231 F. Supp. 331 (D.

Md. 1964); Nesbit v. Statesville City Board of Education, 232 F

Supp. 288 (W. D. N. C. 1964), vacated, 345 F. 2d 333 (4th Cir.

1965); Tillman v. Board of Instruction of Volusia County, Florida,

Civil No. 4501, 7 Race Rel. L. Rep. 687 (S. D. Fla. 1962) ; Manning

v. Board of Public Instruction of Hillsborough County, Fla Civil

No. 3554, 7 Race Rel. L. Rep. 681 (S. D. Fla. 1962); Lawrence v.

Bowling Green, Ky. Board of Education, Civil No. 819, 8 Race Rel.

L. Rep. 74 (N. D. Ky. 1963); Mason v. Jessamine County, Ky.

Board of Education, Civil No. 1496, 8 Race Rel. L. Rep. 75 (E. D.

Ky. 1963) Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City Public

Schools, 219 F. Supp. 427 (N. D. Okla. 1963),

34

they are disadvantaged by the practice in the circumstances

of the particular case. That is the only reasonable expla

nation for the Fourth Circuit’s repeated statements in cases

where the existence of faculty segregation is undisputed,

that there was insufficient showing that faculty segregation

was a denial of plaintiffs’ constitutional rights. The Fourth

Circuit apparently accepts the standing of pupils to litigate

the question but demands that they prove that faculty

segregation is a discrimination against them—as opposed

to a discrimination against the teachers themselves.

But, as Judges Sobeloff and Bell have said, faculty seg

regation obviously makes student desegregation more dif

ficult. A school board decision that it is willing to assign

some Negro pupils to classes with white pupils and white

teachers but that it is unwilling to assign white pupils to

classes with Negro teachers obviously limits the range of

choices the board has when it determines pupil assignment

patterns or attendance areas. The Negro faculty school

obviously continues as a school for Negro pupils only. To

the extent that students or parents are given a choice be

tween schools, faculty segregation encourages them to make

their choice on a racial basis. The very existence of fac

ulty segregation reflects the school authorities’ judgment

that the race of teachers is significant and makes a dif

ference. Cf. Anderson v. Martin, 375 U. S. 399. This is

obvious in the context of states where school segregation

has been defended vigorously by public officials for a

decade since Brown.

Faculty segregation assures continuance of the prevail

ing trend of one-way desegregation, i.e., movement of

Negro pupils to formerly white schools without any cor

responding movement of white pupils to Negro faculty

35

schools. Throughout the southeast part of the country

there are few exceptions to this brand of desegregation

which leaves the “Negro” school intact with an all-Negro

student body and faculty.

It is estimated that there are 419,199 white teachers and

116,028 Negro teachers in 11 southern states, 6 border states

(excluding Maryland) and the District of Columbia.35 In

1963-64, Virginia public schools employed 31,443 white

teachers and 9,051 Negro teachers.36 There were 733,524

white pupils and 34,176 Negro pupils (total 967,700).37 Of

128 districts with Negro and white pupils, 81 districts had

at least one Negro pupil in school with whites in November

1964, but only five of those districts had Negroes teaching

in school with whites.38 There was no facility desegregation

in Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi and South

Carolina.39 One North Carolina district, 2 Florida districts,

and 7 Tennessee districts had some faculty desegregation,

and one Arkansas district had a Negro supervisor of ele

mentary schools but no Negro teachers in desegregated

classes.40

35 Southern Education Reporting Service, Statistical Summary

of School Segregation-Desegregation in the Southern and Border

States, 14th Rev. (Nov. 1964), p. 2.

36 Id, at 59.

37 Ibid,

38 Ibid. The summary reports: “Some Negro teachers are teach

ing in schools with whites in Alexandria and Roanoke, and in

Arlington and Fairfax Counties. In Prince Edward County, nine

of the 68 teachers in the county’s one high school and three ele

mentary schools are white.”

39 id. at 2.

40 Id. at 8, 15, 39, 50.

36

Within the Negro community Negro teachers generally

are recognized as having a leadership role with a compara

tively high economic position,41 but their potential as

leaders in efforts to promote desegregation of public facili

ties and schools is limited by the vulnerability of their posi

tion as employees of segregationist state agencies.42 Con

tinued faculty segregation, posing the danger of discharge

of Negro teachers as Negro pupils go to white schools

where no Negro teachers are assigned, threatens potentially

disastrous social consequences for one of the most impor

tant social and economic groups in Negro communities in

the South.

A recent decision by Judge Michie in the Western Dis

trict of Virginia enjoined school authorities who discharged

every Negro teacher in a small system when the schools

desegregated (Franklin v. School Board of Giles County,

----- F. Supp. ----- , W. D. Va., Civ. No. 64-C-73-K, June

3, 1965). Other cases involving Negro teachers discharged

41 According to the 1960 census the median income for the non

white family was $3,662, but the median for the non-white family

whose head was employed as an elementary or secondary teacher

was $6,400 (1960 Census of Population, Vol. I, “Characteristics

of the Population,” Part I, U. S. Summary, Table 230, pp. 1-611).

42 Lamanna, Richard A., “The Negro Teacher and Desegrega

tion”, Sociological Inquiry, Vol. 35, No. 1, Winter 1965. Alabama

has enacted 7 laws to permit firing of teachers who advocate de

segregation (1956 1st Sp. Sess., Acts 40, 41; 1957 Sess., Act 239,

361; 1961 Sp. Sess., Acts 249, 383, 443). Arkansas laws prohibited

NAACP members from holding public employment and required

teachers to list organization membership until Shelton v. Tucker,

364 U. S. 479. A series of Louisiana laws provided for dismissal

of public employees advocating integration (La. Acts 1956, Acts

248, 249, 250, 252). Until challenged in court South Carolina

barred public employment of NAACP members (S. C. Acts 1956,

Act 741), repealed by Act 223 of 1957. See Bryan v. Austin, 148

F. Supp. 563 (E. D. S. C. 1957), judgment vacated 354 U. S.

933

37

coincident with desegregation are pending in various dis

trict courts. (A partial listing of communities where such

cases were recently filed includes Morganton, N. C., Hender

sonville, N. C., Asheboro, N. C., Pitt County, N. C., Stanton,

Texas, and Wagoner, Oklahoma.)

Petitioners submit that faculty segregation per se vio

lates the constitutional rights of Negro pupils because of

its inevitable tendency to impede desegregation of pupils.

In recognition of this the United States Commissioner of

Education, implementing Title VI of the Civil Eights Act

of 1964,43 has announced the following ruling to all school

districts submitting plans for desegregation in order to

qualify for federal financial aid (General Policy State

ment, supra, Part V.B.) :

1. Facility and staff desegregation. All desegre

gation plans shall provide for the desegregation of

faculty and staff in accordance with the following

requirements:

a. Initial assignments. The race, color, or national

origin of pupils shall not be a factor in the assign

ment to a particular school or class within a school of