Annotated Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae Supporting Appellants

Working File

September 8, 2000

46 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Annotated Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae Supporting Appellants, 2000. 09bae61f-d90e-f011-9989-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0dbdf44d-f5cf-4c14-86e0-152497d9eb11/annotated-brief-for-the-united-states-as-amicus-curiae-supporting-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

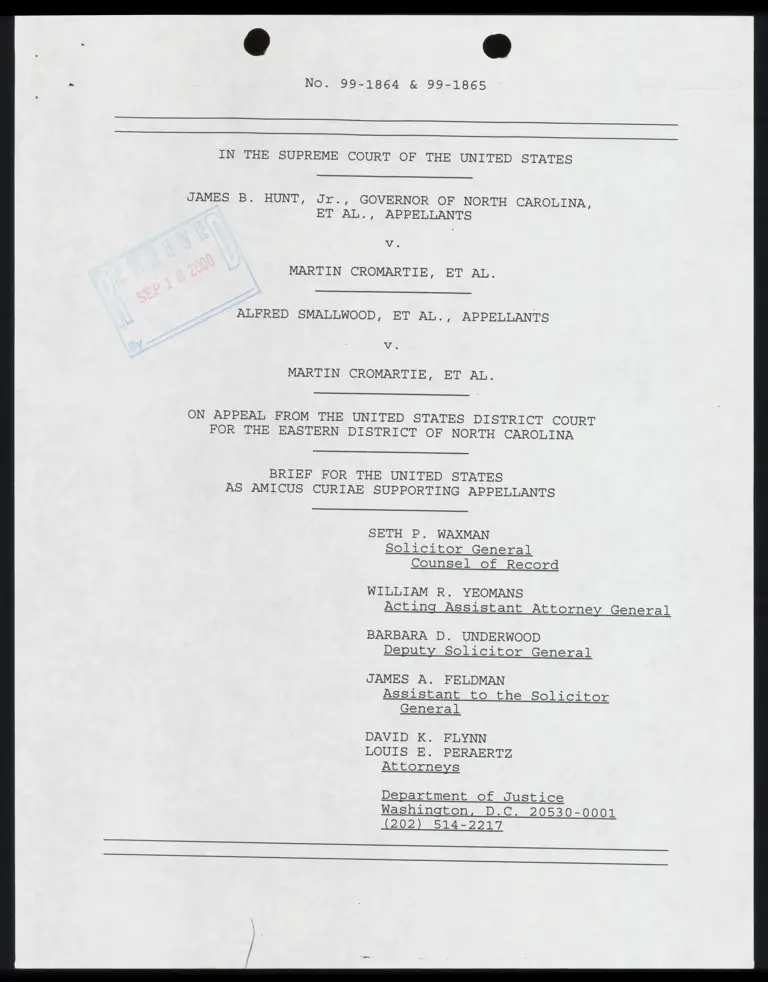

No. 99-1864 & 99-1865

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

JAMES B. HUNT, Jr., GOVERNOR OF NORTH CAROLINA,

ET AL., APPELLANTS

Vv.

MARTIN CROMARTIE, ET AL.

ALFRED SMALLWOOD, ET AL., APPELLANTS

Vv.

MARTIN CROMARTIE, ET AL.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES

AS AMICUS CURIAE SUPPORTING APPELLANTS

SETH P. WAXMAN

Solicitor General

Counsel of Record

WILLIAM R. YEOMANS

Acting Assistant Attorney General

BARBARA D. UNDERWOOD

Deputy Solicitor General

JAMES A. FELDMAN

Assistant to the Solicitor

General

DAVID K. FLYNN

LOUIS E. PERAERTZ

Attornevs

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530-0001

1302) 514.2017

QUESTION PRESENTED

The United States will address the following question:

Whether the district court applied the correct legal

standards in finding that race was the predominant factor in the

drawing of District 12 of North Carolina's 1997 congressional

redistricting plan.

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 99-1864

JAMES B. HUNT, :Jr., ET AL., APPELLANTS

Vv.

MARTIN CROMARTIE, ET AL.

No. 929-1865

ALFRED SMALLWOOD, ET AL., APPELLANTS

Vv.

MARTIN CROMARTIE, ET AL.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES

AS AMICUS CURIAE SUPPORTING APPELLANTS

INTEREST OF THE UNITED STATES

This case concerns a district court's finding that a state

election districting plan was drawn predominantly on the basis of

race, in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment. The United States enforces Sections 2 and

5. of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (42 U.S.C. 1973, 1973¢c), which

require, in part, that States and political subdivisions not

engage in voting practices that deny citizens an equal

opportunity to elect representatives of their choice on account

of their race. Those statutes sometimes require States to take

the racial consequences of their districting decisions into

account. The United States has an interest in ensuring that

2

States have reasonable leeway to design districts that comply

with both the Voting Rights Act and the Equal Protection Clause.

The United States has participated in all three prior appeals in

related litigation. The United States was a party-defendant in

Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993), and filed briefs as amicus

curlae in Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. 899 (1996), and in Hunt v.

Cromartie, 526 U.S. 541 (1999).

STATEMENT

1. In Shaw'v. Hunt, 517 U.S. 899 (1996) (Shaw I1),ithis

Court struck down North Carolina's 1992 congressional district

plan under the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. The Court held that District 12 in that plan had been

drawn predominantly on the basis of race, 517 U.S. at 207, and

that it did not satisfy strict Scrutiny, id. at 910-918.

After this Court's decision, the North Carolina General

Assembly attempted to enact a new districting plan. The state

Senate had a Democratic majority and the House had a Republican

majority. State Senator Roy A. Cooper, "111, and State

Representative W. Edwin McMahan, the chairmen of the Senate and

House redistricting committees, provided affidavits and testimony

detailing the goals and purposes of the committees. J.S. App.

8la-87a, J.A. 179-230 (Cooper); J.8. App. 137a-154a, J.A. 231-244

(McMahan). Among the avowed goals of the committees were "curing

the constitutional defects of the 1992 Plan by assuring that race

was not the predominant factor in the new plan" and "drawing the

plan to maintain the existing partisan balance." . J.S. App. lla.

3

To achieve that partisan goal, "the redistricting committees drew

the new plan (1) to avoid placing two incumbents in the same

district and (2) to preserve the partisan core of the existing

districts to the extent consistent with the goal of curing the

defects in the old Plan." Ibid.

District 12 din the 1997 Plan is different from the district

found unconstitutional in Shaw IT in important respects. As this

Court noted in its prior decision in this case, Hunt v. Cromartie

(Hunt 1), 526 ‘U.S. 541, 544 (1999), District 12 splits six

counties, as opposed to ten in the unconstitutional plan. The

distance between its farthest points has been reduced from 160

miles to 95 miles. Ibid. African-Americans are no longer a

majority in the district, constituting approximately 43% of its

voting age population, 46% of registered voters, and 47% of its

Population. ' Ibid. District 12 is also fully contiguous and,

unlike the unconstitutional District 12 in the 1992 plan, it does

not employ artificial devices such as "crossovers" to achieve

contiguity. : Id. at 83a.

The 1997 Plan was enacted by the legislature on March 31,

1997, despite an earlier belief by many that the party division

between the two houses of the legislature would make such

agreement impossible. J.S. App. 2a, 82a, 138a; J.A. 240. Twelve

of the 17 African-American members of North Carolina's House of

Representatives voted against the plan. Id. at 140a.

2.a. Appellees filed an amended complaint alleging that

District 12 under the 1997 Plan is, like its predecessor, an

4

unconstitutional gerrymander. See Hunt I, 526 U.S. at 544. The

parties filed competing motions for summary judgment and, in

April 1998, the district court, by a 2-1 majority, granted

appellees’ motion. Id. at 545; gee J.S. App. 243a-282a.

b. On May 17, 1999, this Court in Hunt I unanimously

reversed the order granting summary judgment to appellees. The

Court noted that "[t]lhe task of assessing a jurisdiction's

motivation * * * is an inherently complex endeavor" and that it

"requir [es] the trial court to perform a sensitive Inquiry. into

such circumstantial and direct evidence of intent as may be

available." 526 U.S. at 546 (citation omitted). Assessing the

summary judgment record, the Court noted that appellees had

offered "circumstantial" evidence consisting of geographic and

demographic data, id. at 547, which, "[v]iewed in toto, * * *

tends to support an inference that the State drew its district

lines with an impermissible racial motive -- even though they

presented no direct evidence of intent." Id. at 548-549. The

Court also noted, however, that appellants had produced testimony

by the legislators who drew the plan that their intent was "to

make District 12 a strong Democratic district," and what the

Court described as "[m]ore important" expert testimony examining

the demographics and the entire boundary of the district. Id. at

549. That testimony tended to show "a high correlation between

race and party preference," id. at 552, because "in precincts

with high black representation, there is a correspondingly high

tendency for voters to favor the Democratic party" and vice

5

verga, id. at 550. The expert, Dr. David W. Peterson, concluded

that "the data as a whole supported a political explanation at

least as well as, and somewhat better than, a racial explanation"

for the configuration of District 12. Ibid.

The Court noted that a political explanation for District 32

would make the district constitutional, since "a jurisdiction may

engage in constitutional political gerrymandering, even if it so

happens that the most loyal Democrats happen to be black

Democrats and even if the State were conscious of that fact."

526 U.S. at 551. To reject that political explanation, the

district court had necessarily "either credited appellees’

asserted inteveriing over those advanced and supported by

appellants or did not give appellants the inference they were

due." Id. at 552. In either event, "it was error in this case

for the District Court to resolve the disputed fact of motivation

at the summary judgment stage." Ibid.

3. On remand, the three-judge district court held a three-

day trial. On March 7, 2000, the court ruled by a 2-1 margin

that District 12 "continues to be unconstitutional." J.S. App.

35a,

a. The majority initially repeated, virtually verbatim,

many of the same facts regarding the racial composition, party

registration, and statistical measures of compactness that it had

relied on in granting summary judgment to appellees. That

evidence tended to show that cities and counties were divided

such that the portions within District 12 had substantially

6

higher percentages of African-Americans than the portions outside

District 12, see J.S. App. 1l2a-1l4a, and that the boundary of

District 12 excluded certain precincts in which 54-69% of the

voters had registered as Democrats, see id. at 13a-14a. It also

showed that District 12 scored relatively low on statistical

measures of compactness. Id. at 15a-17a. Compare J.S. App.

247a-253a {district court opinion at summary judgment stage).

The majority also referred to evidence presented by

plaintiffs' expert, Dr. Ronald Weber. According to the court,

Dr. Weber "showed time and again how race trumped party

affiliation in the construction of the 12th District and how

political explanations utterly failed to explain the composition

of the districl." «J.S.. App.. 26a. The majority also stated that

Dr. Weber had "presented a convincing critique" of the "boundary

segment" analysis presented by the State's expert, Dr. David

Peterson, and discussed by this Court in its opinion in Hunt

and that Dr. Weber had found that Dr. Peterson's study "'has

been appropriately done,' and was therefore 'unreliable' and

relevant." Id. at 27a. The majority did not itself specify

particular respects in which Dr. Peterson's analysis was

deficient.

The majority finally referred to two other items of evidence

to support its conclusion that race, and not politics, was the

predominant factor underlying the creation of District 12.

First, the majority referred to the testimony of Senator Cooper.

The majority stated that " [tlhe conclusion that race predominated

5

was * * * bolstered by" an allusion by Senator Cooper to a desire

to achieve "racial and partisan balance" as factors underlying

the redigtricting.plan. J.A. App. 27a. The majority found

"simply not credible" Senator Cooper's contention that "he did

not mean the term 'racial balance' to refer to the maintenance

a ten-two balance between whites and African-Americans." ItLid.

Second, the court referred to an e-mail to Senator Cooper that

had been written by Gerry Cohen, the legislative employee who had

been responsible for technical aspects of drawing the 1997 and

earlier state plans. See id. at 8a. The e-mail discussed the

racial composition of a different district -- District 1 --and

then added that "I [Cohen] have moved Greensboro Black community

into the 12th, and now need to take [al]bout 60,000 out of the

12th. I await your direction on this." Ibid.; see J.A. 369

(full text of e-mail). The majority stated that the e-mail

"clearly demonstrates that the chief architects of the 1997 Plan

had evolved a methodology for segregating voters by race, and

that they had applied this method to the 12th District." J.S,

App. 27a.

The majority concluded that the legislature had "eschewed

traditional districting criteria such as contiguity, geographical

integrity, community of interest, and compactness in redrawing

the District," but instead had "utilized race as the predominant

factor in drawing the District." J.s8. App. 29a. 'The court

entered an injunction against use of District 12 in this year's

elections. Id. at 35a.%

b. Judge Thornburg dissented from the panel's holding that

District 12 is an unconstitutional racial gerrymander. J.S. App.

37a-68a. In his view, appellees -- who had the burden of proving

that race was the predominant factor -- had "failed to carry

their burden through either direct or circumstantial evidence."

Id. at 45a. He stated that the State had "produced ample and

convincing evidence which demonstrates that political concerns

such as existing constituents, incumbency, voter performance,

commonality of interests, and contiguity, not racial motivations,

dominated the process surrounding the creation and adoption of

the 1997 redistricting plan." Id. at 45a-46a. He noted that the

12997 Plan's drafters "recognized the necessity of creating a plan

which would garner the support of both parties and both houses"

by "protect [ing] incumbents and thereby maintain [ing] the then

existing 6-6 partisan split amongst North Carolina's

congressional delegation." Id. at 46a. Since District 12 had a

Democratic incumbent, "common sense as well as political

experience dictated ascertaining the strongest voter performing

Democratic precincts in the urban Piedmont Crescent." Id. at

YZ *# The district court also held that District 1 was subject to strict scrutiny, but it found that the State had satisfied that standard. J.S. App. 30a-35a. Appellees did not perfect their appeal from that ruling, and the district court granted appellants' motion to dismiss appellees' appeal on August 3, 2000 (Docket No. 178). Accordingly, although the district court's ruling that District 12 is unconstitutional is now before this Court, the district court's ruling that District 1 is constitutional is no longer at issue, and will not be further addressed herein.

9

47a. The fact "[t]hat many of those strong Democratic performing

precincts were majority African-American, and that the General

Assembly leaders were aware of that fact, is not a constitutional

violation." : Ibid.

Judge Thornburg addressed Dr. Weber's testimony that

District 12 was drawn on a predominantly racial, and not

political, basis, because the District failed to include some

Democratic precincts that had relatively low African-American

populations. Judge Thornburg noted that "there is no dispute

that every one of the majority African-American precincts

included in the Twelfth District are among the highest, if not

the highest, Democratic performing districts in that geographic

region." J.S. App. 50a. He noted that to include other well-

performing Democratic precincts identified by Dr. Weber would

have meant excluding "the highest performing Democratic

precincts." Ibid. He also explained that "few of the strong

Democratic precincts to which Dr. Weber referred could have

easily been included in the Twelfth District" because few of them

"actually ‘abutted" the District. Id. at 50a n.2l1. Judge

Thornburg also noted Dr. Weber's testimony that he had

"considered no hypothesis other than race as the legislature's

predominant motive" because he had believed, mistakenly, "that

the person drawing North Carolina's districts could only see

racial data" on his computer screen. id. at 5la. Finally, Judge

Thornburg noted that Dr. Weber had also "specifically failed to

inquire about real world political or partisan factors which

10

might have influenced the process." Ibid.

With respect to the Cooper-Cohen e-mail, Judge Thornburg

explained that it "does little more than reinforce what is

already known, and what is not constitutionally impermissible:

North Carolina's legislative leaders were conscious of race,

aware of racial percentages, on notice of the potential

constitutional implicationg of their actions, and generally very

concerned with these and every other political and partisan

consideration which affected whether or not the redistricting

plan would pass.” » J.S. App. 48a 'n.18. Those facts "contribute

little to [appellees'] efforts to show that racial motives

predominated." Ibid.

4. On March 16, 2000, this Court entered an order staying

the district court's injunction. 1120'S. Ct. 1415.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

This case presents the Court with what is likely to be its

final opportunity to clarify the legal standards governing a

racial gerrymandering claim before state legislatures begin the

redistricting process triggered by the decennial census. Both in

the Shaw context and elsewhere, this Court has frequently

emphasized the extraordinary sensitivity of redistricting and

high costs of unnecessary federal court intrusion into the

primary authority of the States in this area. For those reasons,

it is crucial that the "predominant factor" test that governs a

racial gerrymandering claim not be interpreted to give district

courts a free-ranging license to substitute their judgments for

il

those of state legislatures in the quintessentially political

determination of how appropriately to draw electoral districts.

This Court's decisions have established that a district is

subject to strict scrutiny when it is drawn with race as the

predominant factor; the plaintiff must prove that traditional

race-neutral districting principles were subordinated to race --

not to some other factor -- before strict scrutiny applies. As

the Court has repeatedly explained, the "predominant factor" test

is a demanding one. It does not license a district court to

intrude in the core state function of redistricting merely

because the State has drawn a district that is majority-minority

or that has a higher minority population than neighboring

districts. Nor does it permit a district court to intrude in

state redistricting merely because racial considerations were a

factor among others in drawing a particular district or in making

some of the subsidiary districting decisions that go into a

districting plan. Rather, a district court may intrude in

districting in this context only if the State's dominant and

controlling rationale was race.

Under that standard, the district court in this case erred

in concluding that the predominant factor in drawing District 12

was racial. First, the district court relied substantially on

evidence that was incompetent to distinguish between race and

politics as a factor responsible for the configuration of

District 12. The crucial and uncontroverted fact is that in

North Carolina African-Americans reliably vote overwhelmingly --

32

90% or more -- for Democratic candidates. Accordingly, any

district that, like District 12, is drawn to concentrate reliable

Democratic voters will tend as well to concentrate African-

American voters. The evidence on which the district court relied

that District 12 is unusually shaped in a way that tends to

correspond with race thus tends only to frame the question --

whether the district was drawn with race or political motives as

predominant -- but not to answer it. The district court also

relied on evidence showing that District 12 fails to include some

precincts with high Democratic registration figures. But in a

State like North Carolina, in which registered Democrats

frequently vote Republican, that evidence is entirely consistent

with the legislature's professed desire to create a district that

would be solidly Democratic on election day, and it provides no

basis for doubting the State's professed political motive.

Second, the district court committed clear error in

inferring from certain evidence presented by appellees' expert,

Dr. Ronald Weber, that race was the predominant motive underlying

District 12. For example, the district court relied on Dr.

Weber's testimony that precincts that had voted for Democratic

candidates in past elections were omitted from District 12. The

evidence on which the court relied would have been sufficient to

tend to disprove the State's partisan objective of creating

District 12 as a solidly Democratic district only if appellees

had shown that including the omitted precincts would have

resulted in a District 12 witha higher overall Democratic voting

13

strength. Omitting precincts with Democratic voting patterns in

favor of precincts with even more solidly Democratic voting

patterns is entirely consistent with the State's professed

objective. It cannot support an inference of predominant racial

motive.

Third, the district court, based in large part on the faulty

inferences discussed above, inferred a predominant racial motive

from statements by Senator Cooper and legislative employee Gerry

Cohen. Insofar as the district court's inferences in this regard

were based on its earlier errors, the court's conclusions should

be disregarded. In any event, however, the inferences the

district court drew from these statements showed at most that

race was a factor underlying District 12. The district court

thus failed to distinguish between a State's mere desire to

achieve a racial objective in districting as one factor among

others and the desire to achieve a racial objective as a

predominant motive underlying District 12; only the latter is

subject to strict scrutiny. Where there is as close a

coincidence of race and politics as in this case, a district

court may not conclude that race was the predominant factor based

solely on isolated findings that in particular respects the

process or result of the State's districting shows that the State

was aware of the racial consequences of its actions or that race

was a factor; to do so would leave States that engaged in

entirely constitutional districting at risk of a district court's

inference that, because they had some racial knowledge or

14

motivation, it must have been predominant.

ARGUMENT

THE PREDOMINANT FACTOR TEST REQUIRES A DISTRICT COURT TO

ENGAGE IN A PARTICULARLY SENSITIVE INQUIRY INTO A STATE'S

INTENT IN DRAWING A DISTRICT, AND IT REQUIRES PROOF NOT

MERELY THAT RACE WAS A FACTOR IN DRAWING A DISTRICT, BUT

THAT IT WAS THE PREDOMINANT FACTOR

A. A Shaw Claim Requires Proof That Race Was The State's

"Predominant Factor"

Shaw v.: Reno, 509 U.S. 630° (1993). (Shaw Lx, this Court

first recognized a claim for racial gerrymandering in violation

of the Equal Protection Clause. In Miller v. Johneon, 515 U.S.

900 (1995), the Court articulated the governing standard: strict

scrutiny is triggered only when "race for its own sake, and not

other districting principles, was the legislature's dominant and

controlling rationale in drawing its district lines." Id. at

913. Race must thus be shown to be "the predominant factor

motivating the legislature's [redistricting] decision." Bush Vv.

Yeia, 517 U.S. 952, 959 (1996) (plurality opinion) (emphasis in

original); see also Shaw Vv. Hunt (Shaw II), 517 U.S. 899, 905

(1996) ; Lawyer v. Department of Justice, 521 U.S. 567, 582

(1957); Hunt v. Cromartie, 526 U.S. 541, 547.(1999) (Hunt 1).

The "predominant factor" test is not the same inquiry

applicable "in cases of 'classifications based explicitly on

race, '" Bush, 517 U.S. at 958, or in cases in which facially

neutral practices are challenged on the ground that race is a

"motivating factor in the decision," Village of Arlington Heights

Vv. Metropolitan Housing Dev. Corp, , 429 U.S. 252, 266 (19777) "5 A

necessary consequence of the Court's holding that a district is

15

subject to strict scrutiny only when race was the State's

"predominant factor" in drawing it is that a Shaw claim is not

made out when race is merely one of the motives or factors

considered -- but not the predominant one -- in drawing the

district. Indeed, the plurality in Bush made that point

expressly, rejecting the view "that it suffices [in making out a

Shaw claim] that racial considerations be a motivation for the

drawing of a majority-minority district." Bush, 517 U.S. at 959

(emphasis in original). In short, "[s]trict scrutiny does not

apply merely because redistricting is performed with

consciousness of race," jd. at 958, "[nJor * * * is the decision

to create a majority-minority district objectionable in and of

itself,” jd. at 962. ‘As Justice O'Connor hae explained, under

the "predominant factor" test, "States may intentionally create

majority-minority districts, and may otherwise take race into

consideration, without coming under strict scrutiny.” Id: at 993

(O'Connor, J. concurring) .

B. The Predominant Factor Test Is A Demanding One

1. This Court has frequently noted, both in Shaw cases and

in other redistricting cases, that "redistricting and

reapportioning legislative bodies is a legislative task which the

federal courts should make every effort not to pre-empt." Wise

Vv. Lipgcomb, 437 U.8. 535, 539 (1978). Of course, federal courts

serve a "customary and appropriate backstop role," Bush, 517 U.S.

at 985, when a state redistricting plan "runs afoul of federal

law,” Lawyer, 521'U.8, 577. But because "reapportionment is

16

primarily the duty and responsibility of the State," Chapman v.

Meier, 420 U.S. 1, 29 (1975), and is "a most difficult subject

for legislatures,” Miller, 515 U.S. at 915, "the States must have

discretion to exercise the political judgment necessary to

balance competing interests, " ibid. "The task of redistricting

is best left to state legislatures, elected by the people and as

capable as the courts, if not more so, 1n balancing the myriad

factors and traditions in legitimate districting policies."

Abrams v. Johnson, 521 U.S. 74, 101 (1997). See also Growe Vv.

Emigon, 507 U.8.:25, 34 (1993). Because of the serious

consequences of federal judicial intrusion into this most

sensitive of state legislative tasks, "[tlhe courts, in assessing

the sufficiency of a challenge to a districting plan, must be

sensitive to the complex interplay of forces that enter a

legislature's redistricting calculus.” Milley, 515 °'U.8. at 915-

916. See also id. at 916 ("[Tlhe sensitive nature of

redistricting and the presumption of good faith that must be

accorded legislative enactments * * =* requires courts to exercise

extraordinary caution in adjudicating claims that a State has

drawn district lines on the basis of race."); id. at 915 ("the

good faith of a state legislature must be presumed").

2. The extraordinary sensitivity of the redistricting

process, coupled with the high costs of undue federal court

intrusion into that process, demands that a district court

scrupulously observe the substantive requirements of the

"predominant factor" test before finding a Shaw violation. In

17

some cases, of course, " [t]he evidentiary inquiry is

relatively easy.” '‘Miller,: 515 U.8. at 913." For example, "[i]ln

some exceptional cases, a reapportionment plan may be so highly

irregular that, on its face, it rationally cannot be understood

as anything other than an effort to 'segregat[e] . . . voters' on

the basis of race." Shaw 1,509 U.S. atc 646-647: Similarly, the

redistricting record or the subsequent litigation may disclose

the relevant State officials making clear that their "overriding

Purpose was * * * to create * * * congressional districts with

effective black voting majorities." Shaw IZ, 517-U.8. at 906;

Miller, 515 U.S. at 918 (State was "driven by its overriding

desire to comply with [racial] maximization demands"). These are

mere examples; other facts can also demonstrate that race was the

predominant factor in a particular case.

In other cases, it cannot so readily be inferred that race

was the predominant factor. For example, when (as is true in

this case) race correlates highly with partisan voting behavior,

it is predictable that a State that wants to create a district

whose borders tend to concentrate members of a particular

political party will, as a byproduct, create a district whose

borders tend to concentrate members of a‘particular race. If

that alone were sufficient to support a finding that strict

scrutiny applies (and that the district is unconstitutional

absent a compelling interest), a State would have to forego its

otherwise lawful option of forming districts on the basis of

partisan choices. Indeed, it would have to do so only in one

-18

category of cases -- where race correlates highly with partisan

voting behavior. That contravenes the settled principles that

"incumbency protection, at least in the limited form of 'avoiding

contests between incumbent [s],' [is] a legitimate state goal,"

and that "political gerrymandering" should not be subjected to

Strict scrutiny... Bush, 517 U.S. at 964.2

Even if the State has taken race into account to some extent

in drawing the district in such a case, that is still not

sufficient to show that the "predominant factor" underlying the

district is racial. As discussed above, strict scrutiny is not

triggered where race is merely "a motivation, " Bush, 517:U.S. at

959, in drawing a district; a Shaw claim requires proof that race

was the predominant factor. Therefore, where race and partisan

voting behavior correlate highly, and a State draws a district

with mixed political, racial, and other motivations, a district

court may not merely seize on isolated evidence tending to show

the State's racial motivation in drawing the district to conclude

that race was the predominant factor in drawing the district. To

permit that inference would paradoxically hamstring state

legislatures in achieving their political objectives in any State

where race correlates highly with partisan voting behavior. For

r

o

’ ‘See Bugh, 517 U.S. at 968 ("If tha State's goal is otherwise constitutional political gerrymandering, it is free to use * * x political data * * * -- precinct general election voting

patterns, precinct primary voting patterns, and legislators’

experience -- to achieve that goal regardless of its awareness of its racial implications and regardless of the fact that it does so in the context of a majority-minority district.") (citations omitted) .

19

even if a legislature paid no attention whatever to race, its

politically motivated districting decisions would likely be

susceptible of a racial interpretation. And if the State

exercised its lawful authority to take race into account to some

extent, it would inevitably risk the finding of predominant

racial motive that was made here. That result would be

inconsistent with bedrock principles recognizing that state

legislatures -- and not federal courts -- have primary

responsibility for the politically highly charged task of drawing

districts, and that federal courts must be particularly cautious

before intruding into state prerogatives in this area. To

trigger strict scrutiny, the party challenging the district must

satisfy the heavy burden of proving that "[r]ace was the

criterion that, in the State's view, could not be compromised."

Shaw II, 517 U.S. :at 907.

Bush v. Vera illustrates these principles. The plurality in

Bush initially noted findings "that the State substantially

neglected traditional districting criteria such as compactness,

that it was committed from the outset to creating majority-

minority districts, and that it manipulated district lines to

exploit unprecedentedly detailed racial data." 517 U.S. at 962,

The plurality stated, however, merely that those factors

"together weigh in favor of the application of strict scrutiny"

-- not that they required its application. Ibid... The plurality

explained that it must therefore "consider what role other

factors played in order to determine whether race predominated."

20

Id. at 963. As the plurality explained, "[b]ecause it is clear

that race was not the only factor that motivated the legislature

to draw irregular district lines, we must scrutinize each

challenged district to determine whether the District Court's

conclusion that race predominated over legitimate districting

considerations, including incumbency, can be sustained." Id. at

965. Only after concluding that there was exceptionally strong

evidence sufficient to show not merely that race was a factor,

but that it was the predominant factor, did the plurality

determine that the districts in question should be subject to

strict scrutiny.?’ The same inquiry was required here.

II. THE DISTRICT COURT IMPROPERLY INFERRED A PREDOMINANT RACIAL

MOTIVE IN THIS CASE

As this Court noted in its decision in Hunt I, the lines of

District 12 correlate highly with race. District 12 contains

portions of six counties; in each of them, the portion of the

county within District 12 has a substantially higher African-

American population than does the portion of the county outside

¥: gee Bugh, 517 U.S. at 969 (evidence that the State itself explained the district "in exclusively racial terms"), 970

(evidence that "districting software * * * provided only racial data at the block-by-block level," and that district lines were in fact determined at that level), 970 (evidence of use of "race as a proxy"), 971 (evidence that shape of district "was far from the shape that would be necessary to maximize the Democratic vote in that area"), 972-973 ("intensive and pervasive use of race both as a proxy to protect the political fortunes of adjacent incumbents, and for its own sake in maximizing the minority

population of District 30 regardless of traditional districting principles"), 975 ("racial demographics and voting patterns * * * belie[] any suggestion that party politics could explain" two adjoining districts, because " [t]he district lines correlate almost perfectly with race, while both districts are similarly solidly Democratic") (citation omitted) .

21

District 12. See Hunt I, 526 U.S, at: 548 & n.4. Moreover, the

boundary lines of District 12 are irregular in shape. See jd. at

547-548. Plaintiffs' claim has always been that this evidence

demonstrated that District 12 was an unconstitutional racial

gerrymander.

As the Court explained in Hunt I, however, the State

advanced a different explanation for the lines of District 12.

At the time of the 1997 Plan, the North Carolina legislature was

divided between Republicans and Democrats, with the Republicans

in control of the House and the Democrats in control of the

Senate. Similarly, the State's congressional delegation was

evenly divided between six Democrats and six Republicans. The

State contended that the legislators in charge of redistricting

concluded that, inthis situation, the only way to get a

redistricting plan through the legislature would be to adopt a

plan that maintained the six-six partisan split in the

congressional delegation and that protected all of the

‘incumbents. See J.S. App. 82a-83a, 138a-139%9a; J.A. 180-182, 235,

240-241. Because District 12 had a Democratic incumbent, the

result was to craft District 12 in such a way as to solidify the

Democratic vote there. Further, it is undisputed that 90% or

more of African-Americans in North Carolina regularly vote

Democratic. See, e.g., J.A. 130 ("over 90 percent" in a series

of ‘gtudies); J.A. 139 ("95 ro 97 percent”). «Accordingly, the

State contended that the correlation between the district lines

and race was a mere by-product of the State's desire to create a

22

solidly Democratic District 12; the result of the State's attempt

to concentrate Democratic voters in the district was that the

most reliable Democratic voters -- African-Americans -- tended to

be included.

In short, this was a "mixed motive" case, like Bush v. Vera.

See 517 U.S. at 959. On remand, what remained for the district

court was to determine whether plaintiffs could carry their

burden at trial of proving that, as between the two motives, race

-- and not the kinds of partisan considerations urged by the

State -- was the predominant factor underlying the District. The

district court's conclusion that plaintiffs had carried that

burden was fatally defective, for three reasons.

A. The District Court Relied Substantially On Evidence

That Was Incompetent To Distinguish Between Race And

Politics As A Factor In Drawing District 12

Much of the district court's opinion is an almost verbatim

repetition of the court's previous opinion on summary judgment.

Compare J.S. App. 10a-17a (final judgment opinion), 23a-26a

(same), 28a-30a (same) with J.S. App. 246a-253a (summary judgment

opinion), 258a-261a (same), 262a-263a (same). The portions of

the majority's opinion repeated from its summary judgment opinion

recite findings that District 12's boundaries correspond with

¥ It is also significant that Digtrict 12 -- with a 43% African-American voting age population and a 47% total African- American population -- is not a majority-minority district. As the Court explained in Lawyer, " [tlhe fact that [the challenged district] is not a majority black district * * = supports the * * * finding that the district iz not a 'safe' one for black- preferred candidates, but one that offers to any candidate, without regard to race, the opportunity to seek and be elected to office.” 521:U.9. "at 53831 (internal quotation marks omitted) .

23

race; that District 12 splits each of the cities and counties it

enters on lines that correspond with race; and that District 12

is unusually shaped under statistical and other measures of

compactness.

The facts recited by the district court are accurate, and in

an appropriate case they could provide substantial evidence of a

predominant racial motive. In the circumstances of this mixed

motive case, however, the evidence recited above only frames the

question; it does nothing to provide an answer. It merely shows

that there must have been some motive behind this unusually

shaped district and that that motive might have been race. But

the State produced substantial evidence showing that its

predominant motives were political, and that political motives

would result in a district with the same unusual shape and the

same racial composition. The evidence that District 12's

boundaries tend to correspond with race does nothing to

distinguish between the two motives and to determine which was

the predominant one -- the primary issue that remained open for

trial after this Court's remand.

Nor is that inquiry advanced by the fact, noted by the

district court in its summary judgment opinion and repeated

verbatim after trial, that "the uncontroverted evidence demonstrates * * * the legislators excluded many heavily-

Democratic precincts from District 12, even when those precincts

immediately border the Twelfth and would have established a far

more compact district." J.8. App. 255; see ld. at 261a (summary

24

judgment opinion). It is true that District 12 excludes a number

of adjacent precincts with high Democratic registration; the

district court enumerated those precincts in its opinion. See

id. at 13a-14a; compare J.S. App. 249a-250a (summary judgment

opinion). But, as this Court noted in Hunt I, the State's

evidence "showed that, in North Carolina, party registration and

party preference do not always correspond." 526 U.S. at 851.

Indeed, the undisputed evidence showed that a large number of

registered Democrats in North Carolina regularly vote Republican.

See J.A. 397, 780% 3.5. App. 1733-1748; 213a-2358.%

Accordingly, the State asserted that it used actual election

returns by precinct -- not registration figures -- to agsess the

partisan makeup of precincts and to construct its 1997 plan. The

fact that District 12's boundaries sometimes omit precincts that

are heavily Democratic by registration does nothing to disprove

the State's contention that its predominant motive was to create

a solidly Democratic District 12, as measured by actual election

returns .¥

2/ For example, in 1996, 54% of the State's voters were registered as Democratic, while only 34% were Republicans. The Almanac of American Politics 1998 at 1056 (1997). Yet the

Republican candidates won in the 1992 and 1996 presidential elections, the State's two Senators at the time of the redistricting were both Republicans (although a Democrat defeated one of them in the 1998 election), and the State's delegation to the 105th Congress consisted of six Republicans and six Democrats

8 There is an additional defect in the district court's inference, because the district court disregarded "the necessity of determining whether race predominated in the redistricters' actions in light of what they had to work with." Bush, '517-U.8.

25

This Court stated in Hunt I that "[e]vidence that blacks

constitute even a supermajority in one congressional district

while amounting to less than a plurality in a neighboring

districtiwill not, by itself, suffice to prove that a

jurisdiction was motivated by race in drawing its district lines

when the evidence also shows a high correlation between race and

Party preference.” Hunt I, 526 U.S. at 551-552. At bottom, the

evidence repeated from the district court's former opinion did no

more than show what this Court determined would "not suffice! to

prove a racial motivation -- much less a predominant racial

motivation. Accordingly, the district court's conclusion in this

part of the opinion that "where cities and counties are split

between the Twelfth District and neighboring districts, the

splits invariably occur along racial, rather than political,

lines," 3.8. Apps 25a, must be rejected as unsupported by the

evidence.’

at 272 n.*. The fact that District 12 excludes even some adjacent precincts with Democratic voting patterns would be of little significance, unless it could be shown as well that including those precincts would make the District as a whole more Democratic. Where, for instance, the district lines tend to exclude precincts with Democratic tendencies while including precincts with more pronounced Democratic tendencies, the exclusion of the former casts no doubt on the State's claim that it was attempting to draw as highly a Democratic district as possible. The evidence in fact showed that this was precisely what happened here, whether measured by party registration or actual election returns. See Joint Exhibits 107-109; see also J.A. 140 (testimony by Dr. Weber agreeing that excluded white precincts are not "as heavily Democratic" as the precincts within District 12.)

+ The State supported its conclusion that the district was drawn along political lines by showing that Republican victories were common in precincts abutting District 12 see J. 8. App. 213a-

26

It Was Clear Error For The District Court To Infer

Predominant Racial Motive From Dr. Weber's Testimony

The district court added a brief additional portion to its

prior opinion. See J.S. App. 26a-28a. That portion purports to

address further the question whether race or partisan

considerations was the predominant factor in drawing District 12.

Some of the evidence to which the district court refers in this

portion of its opinion is essentially repetitious of the evidence

discussed above, and it is thus no more helpful in distinguishing

between racial and partisan motivations underlying District 12.

But the district court also relied on a number of portions of the

testimony of Dr. Ronald Weber, appellees' expert, which the

district court stated showed "time and again how race trumped

party affiliation in the construction of the 12th District and

how political explanations utterly failed to explain the

composition of the district." J.s. App. 26a. That conclusion,

however, was plainly wrong.

Initially, as discussed above, "Party affiliation” ~- as

opposed to actual partisan voting conduct -- is of little

relevance in this case and of no use in the analysis. See pp.

__~__, infra. It was therefore error to rely on portions of Dr.

Weber's testimony that were based on registration data. Beyond

that, however, the evidence presented by Dr. Weber on which the

district court relied was not significantly probative of race as

225a, and that the splits in counties and municipalities divided Democratic portions in District 12 from Republican portions oucside District 12, see J.3. App. 189a, 19l1a-192a. The district court did not address that evidence.

27

the predominant factor in drawing District 12. Accordingly, the

court committed clear error in relying on that evidence.

1. The district court cited a portion of Dr. Weber's

testimony in which he referred to the fact that District 12 has

more Democratic voters than adjoining Democratic District 8. He

stated that the State, had it been following its partisan

objectives, would have "want [ed] to take some of the voters in

the district that you are drawing that's overly safe and put them

into [an] adjacent district so as to make that district more

competitive.” ' Ty, 162 (J.A 91).¥

The State, however, explained the reason for this

configuration. District 12, in general, is no more solidly

partisan than are at least two Republican Districts -- Districts

6 and 10." See J.S. App. 80a (election results). The proportion

of Democrats in District 12 is therefore not suspect. And with

respect to the specific line dividing Districts 12 and 8, the

State explained that that line runs along the border between

&/ The district court referred to another portion of Dr. Weber's testimony, in which he made essentially the same Point, when it stated that "Dr. Weber showed that, without fail, Democratic districts adjacent to District 12 yielded their minority areas to that district, retaining white Democratic Precincts." J.S. App. 26a {citing Tr. 255-256 (J.A. 134-135)), The district court's misapprehension of the record is apparent from its references to "Democratic districts adjacent to District 12," since it'is undisputed that, of the five districts adjacent to District 12, only one (District 8) had a Democratic incumbent in 1997. Moreover, the district court did not specify any majority-minority precincts that had been in District 8 in a prior plan and subsequently were "yielded" to District 12, and we are unable to identify any. As the map of District 12 and its surroundings reveals, see J.A. 483, there are no majority- minority precincts near the border between Districts 8 and 12,

28

Cabarrus County (in District 8) and Mecklenburg County (in

Districts 9 and 12). See J.A. 501 (map). To put some District

12 Democrats into District 8, the State would have had to violate

two political constraints that were important to the legislature:

it would have had to move some of Mecklenburg County into

District 8, which would have divided the county into three

districts and thus violated the State's consistent policy in the

1997 Plan of placing no county in more than two districts, see

J.A. 179, 474-475, 780-782; see also J.A. 658; and it would

likely have required moving some of Cabarrus County out of

District 8 to District 12 in return, thus violating the desire of

Democratic incumbent Hefner in District 8, who lived in Cabarrus

County, to represent his entire home county, see J.S. App. 85a,

J.A. 205-206.

The district court did not discuss the State's proffered

explanation or otherwise explain why it might be deficient.?

97

£ Under Rule 52(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, a

district court "shall find the facts specially and state

separately its conclusions of law thereon." As this Court has

stated, "there comes a point where findings become so sparse and

conclusory as to give no revelation of what the District Court's concept of the determining facts and legal standard may be."

Commissioner v. Duberstein, 363 U.S. 278, 292 (1960). The courts of appeals, led by the Fifth Circuit, have required that district courts exercise special care under Rule 52 (a) in the

redistricting context, and the district court's failure to

exercise such care is itself grounds for reversal. As the Fifth

Circuit has explained, " [b]ecause the resolution of a voting

dilution claim requires close analysis of unusually complex

factual patterns, and because the decision of such a case has the potential for serious interference with state functions,"

district courts must "strictly adhere] to the [Federal Rule of Civil Procedure] 52(a) requirements" that they "find the facts specially" and must "explain with particularity their reasoning and the subsidiary factual conclusions underlying their

29

Dr. Weber admitted that he did not take into account any of the

political considerations advanced by the State. See JA. 135 ("I

don't know anything about what Congressman Hefner asked."), 136

(answering "No" to question whether he "inquired about any real

world political issues that might have been going on that might

have determined why the Legislature drew the line where it did").

Without some reason to discredit the State's explanation, Dr.

Weber's analysis does not provide significant evidence of

discrimination. Accordingly, the district court's inference of

predominant racial motive from Dr. Weber's evidence was

"illogical" and, hence, clearly erroneous. See Anderson Vv. : Clty

of Bessemer City, 470 U.S. 564, 577 (1985).

reasoning." Westwego Citizens for Better Gov't v. City of Westwego, 872 F.2d 1201, 1203 {5th Cir. 1080) (quoting Velasquez v. ity of Ahilene. 725 F.2d 1017, “1020 (5th Cir. 1984)). Other courts of appeals similarly "require a particularly definite record for voting rights cases." Cousin v. McWherter, 46 F.3d 568, 574 (6th Cir. 1995); accord Johnson v. Hamrick, 196 F.3d 1216, 1223 (11th Cir. 1999); Lee County Branch of the NAACP wv. Citv of Opelika, 748 F. 24 1473, 1480 {Iith Cir. 1984); Harvell v. Ladd, 958: F.2d 226, 229 (8th ‘Cir. 1992%.; Buckanaga v. Sisseton Ind. Sch, Dist 5" 804. 7.2d 469, 472: (8th Cir. 1986). The "bedrock rule" that a district court's findings must be "sufficiently detailed to permit a reviewing court to ascertain the factual core of, and the legal foundation for, the rulings below * * *

has particular force in cases of this genre." Uno v. City of Holyoke, 72 F.3d 973, 958 (lst Cir. 1995). That includes the requirement that "the district court must discuss 'not only the evidence that supports its decision but also all the substantial evidence contrary to its opinion. '" Ibid.; see also Velasquez, 725 F.24 at. 1021 (remanding for district court, which wrote a "long and detailed" opinion, to "take note of substantial contrary evidence presented by the appellants"). It also includes the requirement that "when the statistics are the principal evidence offered * * *, the district court must ensure that it thoroughly discusses its reasons for rejecting that evidence." Clark v. Calhoun County. 21 F.3d 82, 96 (5th Cir. 1994).

30

2. The district court also relied on Dr. Weber's testimony

that District 12 contains virtually all (76 out of 79) precincts

that are 40% or more African-American in the six counties that

comprise the district, but it does not contain as high a

percentage of precincts with Democratic tendencies, even as

measured by election results. Tr. 204-205 (J.A. 105-106) :" The

district court clearly erred in inferring a racial motive -- much

less a predominant racial motive -- from that testimony. The

question is not whether there were other precincts in the six

counties with Democratic voting patterns that were left out of

District 12; the question is whether, if there are such

precincts, including them in District 12 would have raised or

lowered the overall likely Democratic vote in District 12. If

the omitted Democratic precincts are far from the borders of

District 12, including them would frequently not have been

practical, and, even if it would, expanding the district to

include them could easily have required including or excluding

other precincts that would have resulted in an overall boost in

Republican strength in District 12. pr. Weber, however, did

not attempt to show that the omitted precincts could have

reasonably been included in District 12 or that their inclusion

would have in fact raised Democratic Strength in the district.

Cf. J.8.,) App. 50a n.21 (Thornburg, 'J., dissenting) (State's

10/

Insofar as Dr. Weber referred to precincts with Democratic voting patterns adjoining District 12, the evidence showed that those precincts were uniformly less Democratic than the precincts included in the district. See Lal, Supra,

31

evidence showed that "few of the strong Democratic precincts to

which Dr. Weber referred could have easily been included in the

Twelfth District"). Without such evidence, Dr. Weber's testimony

on this point proves nothing.’

3. The district court also relied on Page 221 of Dr.

Weber's testimony (J.A. 111) in which he argued that splitting a

single precinct in Mecklenburg County (Precinct 77, the only

split precinct in District 12, see J.S. App. 84a) showed that

race was the predominant motive. The State explained that the

purpose of splitting that precinct, located at the southernmost

tip of Mecklenburg County, was to connect the two portions of

Republican Representative Myrick's district without including

additional Democratic voters in her district. See J.S. App.

208a; J.A. 20, 617-618. ‘That in turn was in service of the

overall goal of protecting incumbents and therefore splitting

Mecklenburg County between the two incumbents who lived there --

the Democratic incumbent in District 12 and the Republican

incumbent in District 9. See J.A. 597-598. Neither the court

nor Dr. Weber addressed that explanation. Although evidence of a

single split precinct is unlikely to be significantly probative

in any event, the failure by Dr. Weber or the court to explain

“/ The district court also referred to pages 262 (J.A. 139-140) and 288 (J.A. 156-157) of the transcript. In those portions of his testimony, Dr. Weber was being cross-examined regarding his claim that Democratic precincts were left out of District 12. His testimony on Cross-examination adds nothing to the analysis. At page 251 of the transcript (J.A. 131), Dr. Weber simply states the conclusion that "[r]ace is the predomina([n]t[] factor." That too adds nothing to the analysis.

32

why the State's explanation was deficient undermines the court's

reliance on this testimony to infer predominant motive. See n.

9, 2upra.

4. Taken individually or together, none of the portions of

Dr. Weber's testimony on which the district court relied were

significantly probative even of race as a factor in drawing

District 12. Moreover, even if it were otherwise and Dr. Weber's

testimony on these points were significantly probative that race

was a factor in drawing District 12, neither a slight increase in

the percentage of Democrats in District 12, a failure to include

some isolated Democratic precincts, nor the splitting of a single

precinct would suffice to show that race was the predominant

factor. The district court committed clear error in finding Dr.

Weber's testimony sufficient to infer that the State's

predominant motive in drawing District 12 was race.

c. The District Court's Conclusions From Other Testimony

Were Infected By Its Earlier Errors And In Any Event,

Confuse Evidence That Race Was A Factor In Drawing

District 12 With Evidence That It Was The Predominant

Factor

1. The district court stated that " [t]he conclusion that

race predominated was further bolstered by Senator Cooper's

allusion to a need for 'racial and partisan balance'" in a

statement made to the state House Committee on Congressional

Redistricting. 3.25 A0n. 27a. At trial, Senator Cooper

testified that by "partisan balance," he meant "[k]eeping the 6-6

split," and by "racial balance," he meant "that African Americans

would have a fair shot to win both the First and 12th Districts,

33

and {1 think that's racially feir." J.A. 323. The district court

stated, however, that " [t]he Senator's contention that although

he used the term 'partisan balance' to refer to the maintenance

of a six-six Democrat-Republican split in the congressional

delegation, he did not mean the term 'racial balance' to refer to

the maintenance of a ten-two balance between whites and African-

Americans is simply not credible." J.S. App. 27a.

When the district court made that credibility finding

regarding Senator Cooper's testimony, it had already made the

errors recounted above in determining that the statistical and

demographic evidence in the case supported an inference of race

as the predominant motive. The district court was no doubt

influenced by those erroneous conclusions in determining that

Senator Cooper's contrary testimony was not credible. Moreover,

the district court's inference that because "partisan balance"

meant a six-six split, "racial balance" must have also meant a

fixed numerical split, is belied by the fact that Senator

Cooper's original testimony did not merely refer to "partisan and

racial balance," see J.S. App. 27a, but to "geographic, racial

and partisan balance," J.A. 460 (emphasis added). Because the

term "geographic balance" does not suggest the kind of division

into neat numerical categories that the term "partisan balance"

does, it is apparent that Senator Cooper did not consistently

mean by "balance" a fixed numerical division of the districts, as

the district court apparently believed.

For the above reasons, the district court's credibility

34

finding regarding Senator Cooper is unsupported. Even if the

district court's finding were accepted, however, it would show at

most that race was a motivation in Senator Cooper's attempt to

configure District 12. He had already testified, however, that

"we did pay attention to race," and that "[t]hat was one of the

factors that was considered," but that "it was certainly not the

predominant] factor." J.A. 222. The question in the case thus

was never whether race was considered, but whether race was the

predominant factor. Neither Senator Cooper's statement that he

was seeking "partisan and racial balance, nor his asserted

failure to explain what he meant by "racial balance" suggests

that racial balance was the predominant motive underlying the

creation of District 12 -- that "[r]ace was the criterion that,

in the State's view, could not be compromised." Shaw II, 517

U.S. at 907.

2. Finally, the district court relied on the Cooper-Cohen

e-mail, in which Gerry Cohen, the legislative employee

responsible for actually drawing the 1997 Plan on the computer,

had said "I [Cohen] have moved Greensboro Black community into

the 12th, and now need to take [a]bout 60,000 out of the 12th. I

await your direction on this." J.g. App. 8a; see J.A. 369 (full

text of e-mail). Cohen's e-mail on its face merely identified

the general characteristics of the community that had been moved

into District 12 by referring to. its.racial composition -- which,

as this Court has noted, "the legislature always is aware of

* * * when it draws district lines, just as it is aware of age,

35

economic status, religious and political persuasion, and a

variety of other demographic factors." Shaw I, 509 U.S. at 646;

see also Bush, 517 U.S. at 958 ("Strict scrutiny does not apply

merely because redistricting is performed with consciousness of

race."). Accordingly, the question presented by the e-mail is

whether the district court properly inferred from that awareness

that "the chief architects of the 1997 Plan had evolved a

methodology for segregating voters by race, and that they had

applied this method to the 12th District." J.S. App. 27a.

As with the Cooper statement, the district court made its

inference with respect to the e-mail only after having made its

erroneous findings that the statistical and demographic evidence

demonstrated a predominant racial motive. Had the district court

not made the earlier errors, it might have seen the e-mail in a

different light, and it might not have drawn the dramatic

conclusion from the e-mail that it did. Indeed, the State had

explained that the reason for moving the community into District

12 was in part to avoid splitting Guilford County into three

districts -- a goal that, as noted above, see p. aeintra, the

State followed consistently with respect to every county in the

State in the 1997 Plan -- and in part to bolster the Democratic

vote in District 12 (a goal desired by the Democratic state

Senate and Congressman Watt, the incumbent there) and to subtract

Democrats from the vote in neighboring District 6 (a goal desired

by Republican Congressman Coble, the incumbent there). See J.A.

192, 123, 195-196, 216, 264-265, 268. The district court did not

-36

specifically address or assess the State's evidence that these

were the primary motivations for moving the portion of Greensboro

into the Twelfth District. See n. 9,:8uUpr8d. Without an

explanation of the district court's reasons for rejecting the

State's proffered explanation, the district court's conclusion

from the e-mail is insupportable.

Finally, even if the e-mail were viewed as persuasive

evidence that race was a factor in moving that portion of

Greensboro into District 12, it would not provide sufficient

evidence to infer that race was the predominant factor in

constructing District 12 as a whole. In this respect, again,

Bush is instructive. In that case, the plurality noted evidence

that "the decision to create the districts now challenged as

majority-minority districts was made at the outset of the process

and never seriously questioned," 517 U.S. at 961, and that those

drawing the challenged districts made use of "uniquely detailed

racial data,” id. at 961-952. Nonetheless, the plurality viewed

that evidence merely as setting forth the question whether race

or politics predominated in drawing the challenged districts, not

as providing an answer for that question. Similarly here, even

scattered evidence that race was a factor taken into account in

determining one or another particular feature of District 12 is

insufficient to show that race was the predominant motive

underlying District 12 as a whole.

3. As is apparent from a review of the district court's

opinion, the court erred in concluding that race was the

37

predominant motive in the creation of District 12. To a

significant extent, the court relied on evidence that could not

resolve the central question before the court: whether race or

politics predominated in the construction of District 12. Even

insofar as the district court, however, relied on evidence that

had to do with racial considerations, the evidence showed at most

that race was taken into account in creating District 12 ~-- a

fact that the State conceded from the beginning. Because the

district court failed correctly to appreciate and apply the

difference between race as a factor and race as the predominant

factor, the district court's conclusion that District 12 is an

unconstitutional racial gerrymander cannot stand. To permit a

district court to find a predominant racial motive in a case like

this would put state legislatures that have acted entirely

constitutionally at risk that a district court, finding that race

was a factor in one or another feature of a districting plan,

could declare the entire plan unconstitutional. That would

threaten to immerse the district courts deeply in the highly

political thicket of redistricting, and it cannot be squared with

the kind of sensitivity toward state legislative efforts in this

field that this Court has always required.

38

CONCLUSION

The judgment of the district court should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted.

SEPTEMBER 2000

SETH P. WAXMAN

Solicitor General

WILLIAM R. YEOMANS

Acting Assistant Attorney General

BARBARA D. UNDERWOOD

Deputy Solicitor General

JAMES A. FELDMAN

Assistant to the Solicitor General

DAVID K. FLYNN

LOUIS E. PERAERTZ

Attornevs

IN . THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

NO. 99-1864 and 99-1865

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., GOVERNOR OF NORTH CAROLINA,

ET AL., APPELLANTS

V.

MARTIN CROMARTIE, ET AL.

ALFRED SMALLWOOD, ET AL., APPELLANTS

Vv.

MARTIN CROMARTIE, ET AL.

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

It is hereby certified that all parties required to be served

have been served with typewritten copy of the BRIEF FOR THE UNITED

STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE SUPPORTING APPELLANTS (to be replaced with

printed copies) by first class mail, postage prepaid, on this 8% day

of September, 2000.

SEE ATTACHED SERVICE LISTS

SETH P. WAXMAN

Solicitor General

Counsel of Record

September 8, 2000

99-1864

HUNT, JAMES B., JR., GOV. OF NC, ET AL.

MARTIN CROMARTIE, ET AL.

ROBINSON O. EVERETT

EVERETT & EVERETT

P.O. BOX 586

DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA 27702

DOUGLAS E. MARKHAM

P.O. "BOX 130923

HOUSTON, TEXAS 77219-0923

MARTIN B. MCGEE

GRADY, DAVIS & TUTTLE

708 MCLAIN ROAD

KANNAPOLIS, NORTH CAROLINA 28081

TIARE B. SMILEY

SPECIAL DEPUTY ATTORNEY

GENERAL

NORTH CAROLINA DEPT. OF JUSTICE

P.O. BOX:.629

RALEIGH, NORTH CAROLINA 27602-0629

ADAM STEIN

FERGUSON, STEIN, WALLAS, ADKINS,

GRESHAM & SUMTER, P.A.

312 WEST FRANKLIN STREET

CHAPEL HILL, NORTH CAROLINA 27516

99-1865

SMALLWOOD, ALFRED, ET AL.

MARTIN CROMARTIE, ET AL.

TODD A. COX

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE &

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

1444 EYE STREET, NW

10TH FLOOR

WASHINGTON, DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA 20005

ROBINSON O. EVERETT

EVERETT & EVERETT

P.O. BOX 586

DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA 27702

ELAINE R. JONES

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE &

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

99 HUDSON STREET

SUITE 1600

NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10013

DOUGLAS E. MARKHAM

P.O. BOX 130923

HOUSTON, TEXAS 77219-0923

MARTIN B. MCGEE

GRADY, DAVIS & TUTTLE

708 MCLAIN ROAD

KANNAPOLIS, NORTH CAROLINA 28081

EDWIN SPEAS

CHIEF DEPUTY ATTORNEY

GENERAL

P.O. BOX 629

RALEIGH, NORTH CAROLINA 27602-0629

ADAM STEIN

FERGUSON, STEIN, WALLAS, ADKINS,

GRESHAM & SUMTER, P.A.

312 WEST FRANKLIN STREET

CHAPEL HILL, NORTH CAROLINA 27516

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

NO." 99-1864 and 99-1865

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., GOVERNOR OF NORTH CAROLINA,

ET AL., APPELLANTS

Y .

MARTIN CROMARTIE, ET AL.

ALFRED SMALLWOOD, ET AL., APPELLANTS

V.

MARTIN CROMARTIE, ET AL.

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

It is hereby certified that all parties required to be served

have been served with printed copies of the BRIEF FOR THE UNITED

STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE SUPPORTING APPELLANTS (replacing typewritten

copies filed on September 8%, 2000) by first class mail, postage

prepaid, on this 13* day of September, 2000.

SEE ATTACHED SERVICE LISTS

SETH P. WAXMAN

Solicitor General

Counsel of Record

September 13, 2000

99-1864

HUNT, JAMES B., JR., GOV. OF NC, ET AL.

MARTIN CROMARTIE, ET AL.

ROBINSON O. EVERETT

EVERETT & EVERETT

P.O. BOX 586

DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA 27702

DOUGLAS E. MARKHAM

P.O. BOX 130923

HOUSTON, TEXAS 77219-0923

MARTIN B. MCGEE

GRADY, DAVIS & TUTTLE

708 MCLAIN ROAD

KANNAPOLIS, NORTH CAROLINA 28081

TIARE B. SMILEY

SPECIAL DEPUTY ATTORNEY

GENERAL

NORTH CAROLINA DEPT. OF JUSTICE

P.O. BOX. 629

RALEIGH, NORTH CAROLINA 27602-0629

ADAM STEIN

FERGUSON, STEIN, WALLAS, ADKINS,

GRESHAM & SUMTER, P.A.

312 WEST FRANKLIN STREET

CHAPEL HILL, NORTH CAROLINA 27516

99-1865

SMALLWOOD, ALFRED, ET AL.

MARTIN CROMARTIE, ET AL.

TODD A. COX

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE &

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

1444 EYE STREET, NW

10TH FLOOR

WASHINGTON, DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

ROBINSON O. EVERETT

EVERETT & EVERETT

P.O. BOX 586

DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA 27702

ELAINE R. JONES

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE &

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

99 HUDSON STREET

SUITE 1600

NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10013

DOUGLAS E. MARKHAM

P.O. BOX 130923

HOUSTON, TEXAS 77219-0923

MARTIN B. MCGEE

GRADY, DAVIS & TUTTLE

708 MCLAIN ROAD

KANNAPOLIS, NORTH CAROLINA 28081

EDWIN SPEAS

CHIEF DEPUTY ATTORNEY

GENERAL

P.O. BOX 629

20005

RALEIGH, NORTH CAROLINA 27602-0629 |

ADAM STEIN

FERGUSON, STEIN, WALLAS, ADKINS,

GRESHAM & SUMTER, P.A.

312 WEST FRANKLIN STREET

CHAPEL HILL, NORTH CAROLINA 27516