Kirkland v. The New York State Department of Correctional Services Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Public Court Documents

December 23, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Kirkland v. The New York State Department of Correctional Services Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees, 1974. 16dd9417-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0dc58bf5-5a6f-4e9f-b8a7-085b4cc9d931/kirkland-v-the-new-york-state-department-of-correctional-services-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

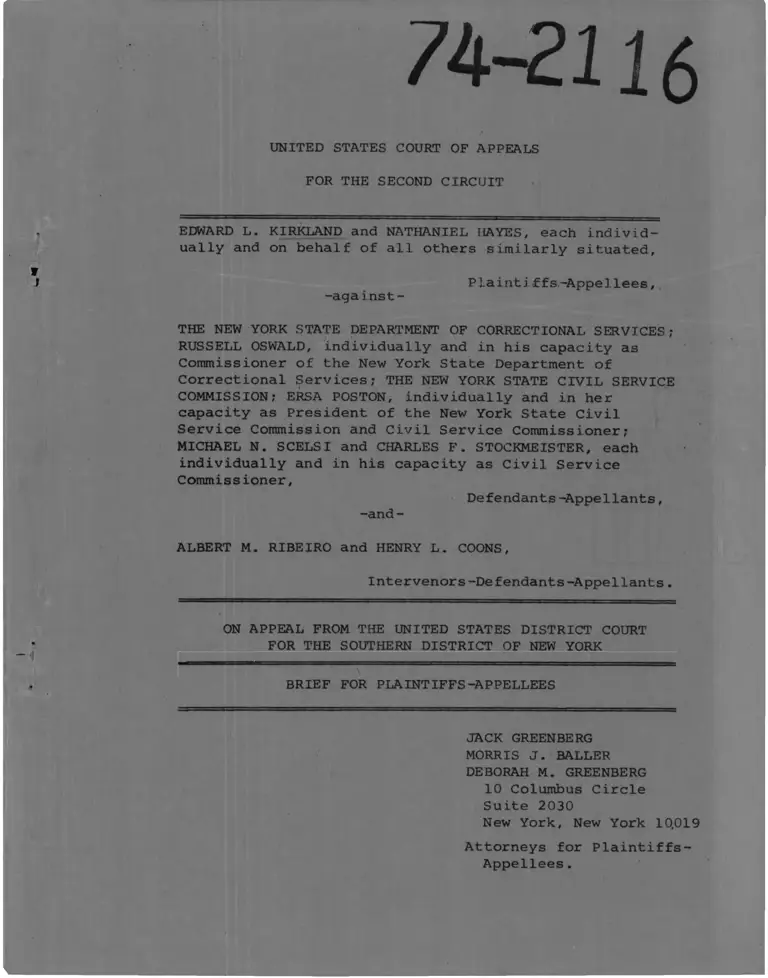

74-2116

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

EDWARD L. KIRKLAND and NATHANIEL I{AYES, each individ

ually and on behalf of all others similarly situated.

Plaintiffs-Appellees,-against-

THE NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONAL SERVICES;

RUSSELL OSWALD, individually and in his capacity as

Commissioner of the New York State Department of

Correctional Services; THE NEW YORK STATE CIVIL SERVICE

COMMISSION; ERSA POSTON, individually and in her

capacity as President of the New York State Civil

Service Commission and Civil Service Commissioner;

MICHAEL N. SCELS I and CHARLES F. S TOCKMEIS TER, each

individually and in his capacity as Civil Service

Commissioner,

Defendants-Appellants,

-and -

ALBERT M. RIBEIRO and HENRY L. COONS,

Intervenors-Defendants-Appellants.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

JACK GREENBERG

MORRIS J. BALLER

DEBORAH M. GREENBERG

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10.019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-

Appellees.

I N D E X

Page

STATEMENT OF ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW ........... 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE .............................. 2

STATEMENT OF FACTS ................................. 6

A. Absence of Blacks and Hispanics from

the Supervisory Ranks of the Depart

ment of Correctional Services ............. 6

B. The Impact of the Sergeant Examinations

On the Promotion of Blacks and Hispanics

to Supervisory Ranks ................. 8

C. Examination 34-944......................... 11

D. Previous Sergeant Examinations ............ 13

E. The Plaintiffs and Other Witnesses ........

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT WAS CORRECT IN HOLDING

EXAMINATION 34-944 UNCONSTITUTIONAL IN

THAT IT EXCLUDED MINORITIES FROM APPOINT

MENT AND WAS NOT SHOWN TO BE JOB-RELATED

A. The Applicable L a w ...... ............. 15

B. The District Court's Ruling That

Examination 34-944 Had A Dispro

portionately Impact Upon Minorities

Is Not Clearly Erroneous ............. 16

C. The District Court's Finding That

Defendants Did Not Meet Their Burden

Of Demonstrating The Job-relatedness

Of Examination 34-944 Must Be Upheld

As Not Clearly Erroneous ............. 20

1. Examination 34-944 Was Not Prepared

In A Manner Consistent With Content

Validity ......................... 21

l

I N D E X f Cont1d ]

Page

a. No job analysis was

performed .................. 21

b. The type of examination,

its scope, the weight of the

subtests and the pass-points

were not determined in a

manner consistent with content

validity .................... 26

2. Defendants Have Not Shown

Examination 34-944 To Be Job-

Related ......................... 31

II. THE DISTRICT COURT'S DEFINITION OF THE

CLASS WAS NOT CLEARLY ERRONEOUS .....

III. THE DISTRICT COURT DID NOT ABUSE ITS

DISCRETION IN ORDERING DEFENDANTS

TO PREPARE A CRITERION-VALIDATED

EXAMINATION AND IN MANDATING APPOINT

MENT RATIOS TO CURE EFFECTS OF PAST

DISCRIMINATION ......................

A. Applicable Legal Principles ....

B. The Court Below Did Not Abuse

Its Discretion In Requiring That

New Job Selection Procedures Be

Validated By Criterion-Related

Techniques .....................

C. The Provisions Of The Decree For

The Promotion Of Class Members

Were Both Proper And Necessary

As Part Of The Equitable Remedy .

IV. THE DISTRICT COURT DID NOT ERR IN

GRANTING PLAINTIFFS THEIR COSTS

INCLUDING ATTORNEYS' FEES AGAINST

DEFENDANTS ..........................

35

35

35

37

40

46

I N D E X [Cont'd]

A. The Eleventh Amendment Does

Not Bar the Award of Attorneys'

Fees Against the State Defendants... 46

B. The Award of Attorneys' Fees Was

a Proper Exercise of the Court's

Equitable Discretion .............. 50

V. THE INTERVENORS' ABSENCE FROM THIS CASE

UNTIL AFTER ISSUANCE OF THE DECISION BELOW

DOES NOT REQUIRE DISMISSAL ............... 56

A. The Intervention Proceedings

Below ............................. 56

B. Intervenors' Absence From

Pre-Decision Proceedings

Is No Reason to Dismiss

This Action ....................... 58

CONCLUSION ................................... 6 3

Page

iii

CASES CITED

Benqer Laboratories Ltd, v. R. K. Laros Co.

24 F.R.D. 450 (E.D. Pa. 1959), aff'd 317 F.2d 455

(3rd Cir. 1963), cert, denied 375 U.S. 833 (1963) . 61

Boston Chapter, NAACP, Inc, v. Beecher

No. 74-1067 (1st Cir. Sept. 15, 1974)............ 18

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond

40 L. Ed. 2d 476 (1974)............................ 52

Brandenburqer v. Thompson

494 F.2d 885 (9th Cir. 1974)...................... 55,54,55

Bridgeport Guardians, Inc, v. Bridgeport Civil Service 15,16,18,

Commission, 482 F.2d 1333 (1973) aff'd in part and 20,33,36, 37,

rev'g in part 354 F, Supp. 778 (D. Conn. 1973) . . 38,39,42,43,45

Bridgeport Guardians, Inc, v. Members of the Bridgeport

Civil Service Commission, 497 F.2d 1113 (2nd Cir. 1973)

cert, filed 43 L.W. 3282 .......................... 51, 53

Carter v. Gallagher 43, 44

452 F.2d 315 (8 th Cir. 1971 and rehearing en banc,)1972.

Castro v. Beecher,

459 F.2d 725 (1st Cir. 1972).................... 18

Chance v. Board of Examiners 15, 16,

458 F.2d 1167 (1972), aff'g. 330 F. Supp. 203 20, 21

(S.D.N.Y. 1971) ..................................

City of Detroit v. Grinnell Corp.

495 F.2d 448 (2nd Cir. 1974).................... 46

Clark v. American Marine Corp.

437 F.2d 959 (5th Cir. 1971), aff'g 320 F. Supp.

709 (E.D. La. 1970).............................. 55

Class v. Norton,

___ F.2d ___ (2nd Cir. No. 74-1702, October 10, 1974)47, 48

Page

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. O'Neill, en banc.

348 F. Supp. 1084 (E.D. Pa. 1972) aff'd in pertinent

part, 473 F.2d 1029 (1973)........................ 43

iv

Cooper v. Allen

467 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1972)...................... 53

Donahue v. Staunton

471 F.2d 475 (7th Cir. 1972), cert, denied 410

U.S. 955 (1973).................................. 53

Edelman v. Jordan,

39 L.Ed. 662 (1974).............................. 47, 48

Ex Parte Young

209 U.S. 123 (1908)............................... 49

Fairley v. Patterson 49, 53

493 F.2d 598 (5th Cir. 1974)..................... 55

Fairmont Creamery Co. v. Minnesota

275 U.S. 70 (1927)......... .................... 49

Fleischmann v. Maier Brewing Co.

386 U.S. 714 (1967)............................... 51

Fowler v. Schwartzwalder

498 F.2d 145 (8th Cir. 1974)..................... 51, 53

Gates v. Collier

489 F.2d 298 (5th Cir. 1973), reh. en banc granted 47

Gresham v. Chambers

501 F.2d 687 (2nd Cir. 1974).................... 51

Hall v. Cole

412 U.S. 1 (1973)................................ 51

Hoitt v. Vitek

495 F.2d 219 (1st Cir. 1974).................... 49, 53

Incarcerated Men of Allen County v. Fair

___ F.2d ____ (6 th Cir. No. 74-1052, November 13, 50, 53

1974)............................................ 55

International Salt Co. v. United States

332 U.S. 392 (1947)................................ 36

Ionian Shipping Co. v. British Law Ins. Co.

426 F.2d 186 (2nd Cir. 1970).................... 57

Jordan v. Fusari 48, 53

496 F.2d 646 (2nd Cir. 1974) 55

Page

v

Page

Jordan v. Gilligan

500 F .2d 701 (6th Cir. 1974), cert, filed

43 L.W. 3240 ................................ 49

Kirkland v. New York State Department of

Correctional Services, 374 F.Supp. 1361

(S.D.N.Y. 1974)................................ passim

Knight v. Auciello. 453 F.2d 852 (1st Cir. 1972) 53

T.aRaza Unida v. Volpe, 57 F.R.D. 94 (N.D. Cal. 1972)

aff’d 488 F. 2d (9th Cir. 1973).................. 54

Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corp., 444 F.2d

143 (5th Cir. 1971)............................ 51, 53

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965). . . 36, 37

Milburn v. Hueeker, 500 F.2d 1279 (6th Cir. 1974). . 49, 53

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 426 F.2d

534 (5th Cir. 1970)............................ 55

Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite Co., 396 U.S. 375

(1970)........................................ 51, 52

NAACP v. New York, 413 U.S. 345 (1973)............ 57

Named Individual Members of San Antonio Conservation

Society v. Texas Highway Dept., 496 F.2d 1017

(5th Cir. 1974), reh. en banc g r a n t e d .......... 49

National Licorice Co. v. N.LR.B., 309 U.S.

350 (1940)...................................... 62

Natural Resources Defense Council v. Environmental

Protection Agency, 484 F.2d 1331 (1st Cir. 1973). 53, 55

Natural Resources Defense Council v . Tennessee

Valley Authority, 340 F.Supp. 400 (S.D.N.Y. 1971),

rev'd on other grounds 459 F.2d (2nd Cir. 1971).. 61

vi

Page

Newman v. Piqgie Park Enterprises, Inc.

390 U.S . 400 (1968)........................ 52

Parker Rust-Proof Co. v. Western Union

Tel. Co., 105 F .2d 976 (2nd Cir. 1939) cert.

denied 308 U.S. 597 (1939).................. 61

Patterson v. Newspaper and Mail Deliverers'

Union, 8 EPD f9736 (S.D.N.Y. 1974).......... 61

Provident Bank & Trust Co. v. Patterson,

390 U.S. 102 (1968)........................ 59, 60

Rios v . Enterprise Association Steamfitters,

Local 638. 8 EPD K9558 (S.D.N.Y. 1974). . . . 36,37,38, 42,61

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791

(4th Cir. 1971), cert. dismissed 404 U.S.

100 (1971).................................. 62

Russell v. Hodges. 470 F.2d 212 (2nd Cir. 1972) 62

Schutten v. Shell Oil Co., 421 F.2d 869

(5th Cir. 1969)............................ 60

Shields v. Barrow. 17 How. 130 (1855).......... 59

S ims v. Amos, 340 F.Supp. 691 (M.D. Ala. 1972)

aff'd 409 U.S. 942 (1972).................. 49, 54

Shekan v. Board of Trustees of Bloomsburg State

College, 501 F.2d 31 (3rd Cir. 1974), cert.

filed 43 L.W. 3296.......................... 49

Sprague v. Ticonic National Bank, 307 U.S.

161 (1939)................................. 51

Stolberg v. Members of the Board of Trustees

for the State Colleges of Connecticut, 474

F .2d 485 (2nd Cir. 1973).................. 47, 48, 53

vii

Page

Taylor v. Perini, 503 F.2d 889 (6th Cir. 1974)

cert, filed 43 L .W. 3281 .................... 49, 53

United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp.,

446 F . 2 d 652 (2nd Cir. 1971)................ 62

United States v. Wood, Wire & Metal Lathers,

Local 46. 471 F.2d 408 (2nd Cir.)

cert, denied, 412 U.S. 939 (1973)............ 36,37,42

Vulcan Society of the New York Fire Department

Inc. v. Civil Service Commission of the City

of New York, 490 F.2d 387 (1973) aff'g in part 15,16,17,18,

and rev'd in part 353 F.Supp. 1092 (S.D.N.Y. 1973) 20,21,36,38,39

Wilderness Society v. Morton, 495 F.2d 1026

(D.C. Cir. en banc 1974), cert, granted

43 L.W. 3208 ................................ 54

t

viii

PaqeStatutes

Fair Housing Act of 1968

42 U.S.C. § 3612 ..................... 49

42 U.S.C. § 4321 ..................... 54

Title VII of Civil Rights Act of 1964

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 (k) ...................... 4 9 , 50

Title VII of Civil Rights Act of 1964

42 U.S.C. § 2OOOe-5 (f) .......... ............

Title II of Civil Rights Act of 1964 ............... 4 9 , 52

49 U.S.C. § 1653 ................................. 54

42 U.S.C. § 1857 ................................. 53

42 U.S.C. § 1973 ................................. 53

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ................................. 52, 53, 54

42 U.S.C. § 1982 ................................. 53, 54

42 U.S.C. § 1983 ................................. 52 , 53, 54

Emergency School Aid Act of 1972

20 U.S.C. § 1 6 1 7 .............................. 49

McKinney's New York Civil Service Law (1973)

§ 52(2) .................................. 2 7

§ 65 .................................. 62

Rules

Rule 19(a), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure . . . . 59

Rule 19(b), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure . . . . 58, 59

EEOC Guidelines on Employment Selection

Procedures, 29 C.F.R. § 1607 .................... 5

Advisory Committee Notes, 39 F.R.D. 69 (1966). . . . 57,59, 61

Other Authorities

Attica, The Official Report of the New York State

Special Commission on Attica (Bantam) (1972) . . . 3 9 , 4 5

STATUTES, RULES AND REGULATIONS CITED

IX

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

NO. 74-2116

EDWARD L. KIRKLAND, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

-against-

THE NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF

CORRECTIONAL SERVICES, et al..

Defendants-Appellants,

-and-

ALBERT M. RIBEIRO and HENRY L. COONS,

Intervenors-Defendants-Appellants.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE' SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

This case challenging state civil service examinations

as being racially discriminatory is here on appeal from a decree

of the District Court for the Southern District of New York

(Lasker, J.) entered July 31, 1974, in accordance with an opinion

dated April 1, 1974.

STATEMENT OF ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

1. Whether the District Court's finding that

examination No. 34-944 for the position of Correction

Sergeant (Male) had a discriminatory impact upon Blacks

and Hispanics must be upheld as not clearly erroneous?

2. Whether the finding below that defendants

did not demonstrate the job-relatedness of said examina

tion was not clearly erroneous?

3. Whether the definition of a class composed

of all Black and Hispanic Correction Officers or provisional

Correction Sergeants who failed examination 34-944 or ranked

too low to be appointed was not clearly erroneous?

4. Whether the District Court's grant of injunctive

relief was not an abuse of discretion in light of the dis

criminatory impact and non-job-relatedness of examination

No. 34-944 and previous examinations?

5. Whether the District Court's award of counsel

fees to plaintiffs must be upheld as not beyond its power

and not an abuse of discretion?

6 . Whether this Court should dismiss this fully

litigated action and deny relief from unconstitutional

practices because certain allegedly necessary parties were

not joined?

1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This action for declaratory and injunctive relief

was filed April 10, 1973 by Edward L. Kirkland and Nathaniel

Hayes, Black Correction Officers provisionally appointed to

1/

the rank of Correction Sergeant, against the New York State

Department of Correctional Services, its Commissioner, the

New York State Civil Service Commission and its three

Commissioners. The complaint challenged the legality, under

42 U.S.C. §§1981 and 1983 and the Fifth and Fourteenth Amend

ments to the Constitution of the United States, of Civil

Service examination 34-944 for promotion to the position of

Correction Sergeant (Male) on the ground that it had a dis

proportionately adverse impact upon Black and Hispanic

2/

candidates and could not be shown to be job-related (A. 7-24).

That day the District Court entered a Temporary Restraining

Order restraining defendants-appellants (hereafter, "defendants")

from "making any permanent appointments to the position of

Correction Sergeant (Male); and from terminating or otherwise

interfering with the provisional appointments of the named

1/ A third plaintiff, the Brotherhood of New York State Correction

Officers, Inc., withdrew at the commencement of the trial.

2 / This form of citation is to pages of the Appendix.

2

plaintiffs and those members of the class who are provisional

Correction Sergeants (Male)" (A. 33-37). By modification and

stipulation said Temporary Restraining Order was extended

until the entry of a decision on the merits (A. 6 6-6 8 , A.69-74).

Plaintiffs-appellees (hereafter "plaintiffs") filed

an amended complaint June 22, 1973 alleging that Sergeant

examinations administered prior to 1972 had a discriminatory

impact on Blacks and Hispanics and could not be shown to be

job-related (A. 28-31). Defendants answered the complaint

and amendment thereto on July 19, 1973, denying plaintiffs

allegations (A. 86-97).

After extensive discovery, the action came on for a

six-day trial before the Honorable Morris E. Lasker.

In its April 1, 1974 opinion (A. 148-200), the District

Court found that plaintiffs' showing of the differential impact

of examination 34-944 was "amply established" (A. 164), that the

construction of the examination was characterized by a "lack of

professionalism" (A. 180), that "the slavish imitation of earlier

examinations . . . indicates an alarming lack of independent

thought, about how to assure that 34-944 was job-related" (A.181-

182), and that "positive evidence of job-relatedness is con

spicuous by its absence" (A. 184). As to past examinations,

the court found that while there was evidence of discriminatory

3

impact, there was no evidence as to job-relatedness (A. 181). .

The Court found that plaintiffs had demonstrated the existence

of a class composed of all Black and Hispanic Correction

Officers or provisional Correction Sergeants who failed 34-944

or who passed but ranked too low to be appointed (A. 187). The

Court declared examination 34-944 unconstitutional and enjoined

defendants from making appointments based on its results (A.188-

89), but deferred decision on the extent of affirmative relief

to give defendants an opportunity to address themselves to

plaintiffs' recommendations (A. 189-90). The Court awarded

plaintiffs reasonable costs, including attorneys' fees, in an

amount to be determined after further documentation (A. 196).

Subsequent to rendering of the court's opinion, on

April 22, 1974, Albert M. Ribeiro and Henry L. Coons, provision

al Sergeants who would have been appointed permanent Sergeants

on the basis of their performance on examination 34-944 effect-

37

ive April 12, 1973 but for the Temporary Restraining Order,

moved to intervene as parties defendant (A. 201). They were

granted intervention on condition that they not seek to relitigate any

3/ The Temporary Restraining Order was modified April 11,

1973 to permit defendants to give provisional appointments

as Sergeants to a group of Correction Officers who were

scheduled to receive permanent appointments on April 12, 1973

(A. 6 6-6 8 ). Intervenors were appointed pursuant to said order.

4

matter which they might have theretofore litigated had they

been parties from outset (A. 230-31). Intervenors1 motions

to maintain a class action and to add as parties defendant

all persons who passed examination number 34-944 were

denied (A. 231-34).

On July 31, 1974 the District Court entered a de

cree (1 ) enjoining defendants from in any way acting upon

the results of Examination No. 34-944; (2) mandatorily en

joining defendants to develop a new selection procedure val

idated in accordance with the EEOC Guidelines on Employment

Selection Procedures, 29 C.F.R. §1607; (3) requiring that

such validation be by means of empirical, criterion-related

validation techniques insofar as possible; (4) providing for

interim appointments to the position of Correction Sergeant

(Male) upon application to the Court; (5) mandatorily enjoin

ing defendants to make all appointments on the basis of one

Black or Hispanic for each three whites so appointed until

the combined percentage of Black and Hispanic persons in

the rank of Correction Sergeant (Male) is equal to the

combined percentage of Blacks and Hispanics in the rank of

Correction Officer (Male). The Court retained jurisdiction

to supervise the decree and to determine the reasonable

value of plaintiffs' attorneys' services (A. 241-45).

5

STATEMENT OF FACTS

A. Absence of Blacks and Hispanics from

the Supervisory Ranks of the Depart-

ment of Correctional Services________

In the Correction Officer series of the New

York State Department of Correctional Services, the entry

level position is Correction Officer. Promotions are

made to successive supervisory positions of Sergeant,

Lieutenant, Captain, Assistant Deputy Superintendent,

Deputy Superintendent and Superintendent on the basis of

a series of written examinations (A. 1327-29).

Candidates for promotion from Correction Officer

to Correction Sergeant must take a written exam prepared

and administered by the New York State Department of Civil

Service. The passing score is established by the Depart

ment of Civil Service, after the examination has been

scored, at a level which will insure that an adequate num

ber of people will be available to fill vacancies (A. 578).

By state law, however, the passing score may not be set

higher than 70% (A. 760).

Those who pass are placed on a ranked eligible

list on the basis of their scores after adding seniority and

veteran's preference credits (vhere applicable). After eligibles have

6

been canvassed to ascertain acceptors for geographic areas

where correctional facilities are located, candidates are

selected from eligible lists in rank order, subject to the

One in Three rule (A.1268- 69). in the event that an eligible

list is exhausted before publication of a new list, provisional

appointment of Sergeants are made on the basis of 1 ) ability as

a Correction Officer, 2)evaluations from the superintendent and

supervisors and 3) leadership ability and empathy with the in

mate population (A. 1269-1278).

Blacks and Hispanics have been almost totally excluded

from the supervisory ranks of the Department of Correctional

Services. As of May 1, 1973 there were no Blacks or Hispanics

holding permanent appointments as Correction Sergeants (Male)

(A. 1448). Of the 237 men in the combined classifications of

Sergeant, Lieutenant and Captain, only two, Captain David

Harris, and Lieutenant Clayton Hill, were Black; none was

Hispanic (A. 286, 393-95, 1447). As of January 1, 1973

there were 85 provisionally appointed Sergeants and 122

permanent Sergeants in the Department's Correctional facilities

4/

Ten provisional Sergeants were Black; none was Hispanic (A. 1447).

4/ All ten would have been returned to the rank of Officer on

April 12, 1973 but for the Temporary Restraining Order (A. 1277-

79) .

7

While the numbers of Assistant Deputy Superinten

dents, Deputy Superintendents and Superintendents is not

in the record, persons serving in state correctional

facilities for up to twelve years could recall no Black

supervisors other than Hill and Harris (A. 268, 395, 473-

74, 533). Defendants presented no evidence to the contrary

B. The Impact of the Sergeant Examinations

On the Promotion of Blacks and Hispanics

to Supervisory Ranks _______________ _

October 14, 1972, the Department of Civil Service

administered promotional examination 34-944 for the

position of Correction Sergeant (Male). 1,432 men took the

5/

examination and 406 passed (PX-5). Of 1,263 whites who

took examination 34-944, 389 or 30.8%, received passing

6 /

scores; of 104 Blacks, 8 or 7.7%, passed; of 16 Hispanics

5/ As the trial court noted (A. 197 n.3), while the

eligible list promulgated on the basis of the results

of examination 34-944 (PX-5) which is not reproduced

in the Appendix) indicates that 1432 took the examination,

the computer display (A. 1343-48) shows a total of only

1,383 Black, Hispanic and white candidates. Presumably,

the discrepancy is attributable to "others", e.g., Asian-

Americans or Native Americans, or persons whose race/

ethnicity was unknown.

6_/ The raw passing score was 5 3 (70% of 75, the number of

items on the exam).

8

2 , or 12.5%, passed (A. 154, 736, 1343-48). Defendants

admitted the statistical significance of these differences

(A. 736-37) .

The passing score serves more to regulate the numbers

on the eligible list than to determine who is qualified to

be a Correction Sergeant (A. 578). In assessing the dis-

»

criminatory effect of the exam, far more meaningful than

pass-fail statistics is evidence of the relative numbers

of whites, Blacks and Hispanics who took the exam and the

number who scored high enough to be likely to be appointed.

In April 1973 the Department of Correctional Services made

8/

87 provisional appointments from the eligible list established

on the basis of examination 34-944. One of the appointees

was Black (A. 1279-80). On May 29, 1973 the Department in

dicated that it planned to appoint an additional 40-60

sergeants over the next two years. Thus, through May 1975

7/

7/ PX-33 (A. 1449), which shows 383 whites having received

passing scores, is in error. PX-12, pp. 1 and 2 (A. 1343-44)

were changed to reflect the fact that one candidate previous

ly recorded as white was Black, but pp. 5 and 6 (A. 1347-48)

showing test performance of whites was not changed. Therefore,

it shows that 1,264 whites took the exam, but should show 1,263

and shows that 390 passed but should show 389.

8/ See n.3 supra.

9

a maximum of 147 Sergeants would have been appointed.

Another Sergeant's exam was planned for 1974 (A. 1460)

and the eligible list from examination 34-944 would have

expired several months thereafter, in 1974 or early 1975

(A. 197-98 n.5) .

The display of the results of examination 34-944

shows that 157 whites, 2 Blacks and no Hispanics attained

scores of 57 or above (A. 1343-48). Nothing in the record

indicates that this pool of 159 eligibles would not be suffi

cient to provide the 127-147 sergeants to be appointed from

this list. Thus, while 157, or 12.4% of the whites who took

the test were likely to be appointed, only 2, or 1.9% of the

Blacks, and none of the Hispanics who took the test were

likely to be appointed. As the court below noted, these

results would lead to the appointment of whites at 6.5 times

the rate for Blacks, and completely bar the appointment of

Hispanics (A. 155).

The discriminatory impact of the 1970 Sergeants

examination, No. 34007, was even greater; indeed it was absolute.

Of the 997 whites tho took examination 34007 and were still em

ployed on January 1, 1973, at least 94 or 9.4% passed; of the

46 Blacks and Hispanics who took the examination and were still

10

employed on January 1, 1973, none received a passing score

9/

(A. 1436-43).

Although there are no data in the record with respect

to pre-1970 Sergeant examinations, the racial composition of

present supervisory personnel, taken with undisputed testimony

that the only minority supervisors in the last twelve years

were two Blacks who are still the only minority supervisors,

icreates a powerful inference that very few Blacks, and probably

no Hispanics, ever passed the examinations, or more importantly,

scored high enough to be appointed.

C . Examination 34-944

Examination 34-944 was a written examination consisting

of five subtests of 15 items each. Each subtest was designed

to test for knowledge, skills and abilities (K, S, & A's) in

one of the following areas: Laws, rules and regulations;

modern correctional methods, using good judgment, preparing

written material; and supervision (A. 1332-1336, 1353).

While there are certain areas of ambiguity, the record

indicates generally the manner in which examination 34-944

was constructed. In May, 1972, the Department of Correctional

9/ The passing score on the 1970 Sergeant examination is not in

the record. The above data is based upon the assumption that

the passing score was the maximum allowed by state law, 70% of

90 (the number of items on the exam, see PX-43, page 2) or 63.

Even if the passing score were lower,the fact remains that the

list was exhausted without any Blacks or Hispanics having been

appointed therefrom.

11

Services notified the Department of Civil Service that a

substantial number of provisional Correction Sergeants were

about to be appointed and that it would be necessary to pre

pare a new Sergeant examination (A. 1349). On June 1, a

"scope conference" was held, attended by personnel from the

two departments. It was determined that the scope of examina

tion 34-944 would be the same as for the 1970 examination,

except that a subtest on preparation of written reports

would be substituted for one on interpretation of written

materials (Id.). On July 26, 1972, three officers from

Correctional Services, (then) Lieutenants Ciuros, Sperback,

and Harris, met with personnel from Civil Service and were

asked to prepare items on rules and regulations, modern

correctional methods, and judgment (A. 1339). The three

Corrections cohsultants were directed to draft questions

from their own work experience (A. 787). The ̂ items on these

three subtests were also worked on by three examiners in Civil

Service, Kenneth Siegal, Mrs. Walters and Mr. Bouldin (A. 602).

The items on supervision and report preparation were assigned

for preparation to a group in Civil Service which prepares

such tests for a variety of occupations (Id_.) During the period

that the items were being prepared, KS&A statements (A. 1332-

36), which were supposed to serve as subtest descriptions and

12

guidelines for the preparation of test items (A. 901), were

also being prepared (A. 902). The KS&A’s for the subtests

on rules and regulations, modern correctional methods and

judgment were drafted by Mr. Siegal, Mrs. Walters and Mr. Bouldin

those for subtests on supervision and report preparation by the

special examiners who prepared those subtests (A. 602).

D . Previous Sergeant Examinations

Sergeant examinations have for many years been prepared

by the same process by which examination 34-944 was developed.

(A. 624).

The fact that (a) the scope of every examination since

1964 was virtually identical (A. 1469), (b) the class specifi

cations for Correction Sergeant were unchanged since 1962 (A.

1474-84), and (c) prior examinations were consulted in prepar

ing examination 34-944 (A. 889) lead the trial court to conclude

that pre-1972 Sergeant examinations were similar to examination

3 4 - 9 4 4 (A. 181-82).

E. The Plaintiffs and Other Witnesses

Plaintiffs Kirkland and Hayes served as Correction

Officers at Ossining from 1962 and 1961,respectively, until

August 1972, when they were provisionally appointed to Correct

ion Sergeant (A. 371, 374, 446, 449). Each has taken and failed

13

the Sergeant examination four times. According to the

Assistant Deputy Superintendent at Ossining, their perform

ance as provisional Sergeants was satisfactory and there

was no reason they were not qualified to be sergeants other

than that they failed the examination (A. 320-21). The

Superintendent wrote letters to plaintiffs commending them

for "cooperation, diligence and dedicated performance" as

provisional Sergeants, stating that he would recommend them

for permanent appointment at Ossining or any other institu

tion (A. 1454-55).

Four other black provisional Sergeants and one

Black Correction Officer testified that they had taken the

Sergeant examination as many as four times and had either

failed or had passed with grades too low to be appointed

(A. 282, 349-50, 436-37, 518, 543). There was no evidence

that they had performed their duties other than satisfactorily.

14

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT WAS CORRECT IN

HOLDING EXAMINATION 34-944 UNCON

STITUTIONAL IN THAT IT EXCLUDED

MINORITIES FROM APPOINTMENT AND

WAS NOT SHOWN TO BE JOB-RELATED

A . The Applicable Law

There is a well-defined body of law which clearly

articulates the governing standards applicable to the issues

presented in this case.

The leading cases in this Circuit are Chance v. Board

of Examiners, 458 F.2d 1167 (1972), aff'g. 330 F.Supp. 203

(S.D.N.Y. 1971) ("Chance."); Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v. Bridge

port Civil Service Commission, 482 F.2d 1333 (1973), aff'g in

part and rev'g in part 354 F.Supp. 778 (D. Conn. 1973) ("Bridge

port" ); and Vulcan Society of the New York Fire Department,Inc.

v. Civil Service Commission of the City of New York. 490 F.2d

387 (1973), aff'g in part and rev'g in part 353 F.Supp. 1092

(S.D.N.Y. 1973)("Vulcan"). The rule established by these

authorities is that in a case such as the instant one, if plain

tiffs show that an examination has had a disproportionately

adverse impact upon a racial or ethnic group, defendants must

meet a heavy burden of justifying the use of the test by estab

lishing that performance on the test bears a demonstrable re

lationship to the ability to perform the job for which it is used.

15

The District Court,in holding examination 34-944 unlawful,

expressly followed these decisions (A. 150-51) and correctly

applied the standards laid down therein.

B. The District Court's Ruling That Examination

3 4 - 9 4 4 Had A Disproportionately Adverse Impact

Upon Minorities Is Not Clearly Erroneous______

Plaintiffs proved, and the trial court found, that whites

passed examination 34-944 at a rate four times that of Blacks

and 2.5 times that of Hispanics. Defendants conceded the

statistical significance of these disparities (A. 154). More

significantly, plaintiffs demonstrated, and the court found,

that whites scored high enough to be appointed at 6^ times the

rate for Blacks and that no Hispanics scored high enough to be

appointed (A. 155). Thus, the disproportionately adverse impact

which examination 34-944 had on Blacks and Hispanics was sub

stantially greater than that held sufficient to establish a

prima facie case of discrimination in Chance, Vulcan and Bridge -

port (A . 155) .

Defendants, however, contend that although examination

3 4 - 9 4 4 was given state-wide to provide a state-wide pool of

Correction Sergeants, the District Court's reliance on state

wide pass-fail data was clearly erroneous. Instead, they argue,

the Court should have compared white and minority passing rates

facility-by-facility. Defendants reason that mean scores of both

16

whites and minorities were lower at Ossining and Greenhaven

(where the minority candidates are concentrated) than at other

facilities, indicating that the overall disparity is the result

of "facility effect," not ethnicity, and that the "variable" of

"facility effect" can only be "screened out" by comparing white-

10./

minority performance at each facility (Br. 36-46). Such a

comparison, defendants maintain, would show a "statistically

significant" difference in passing rates only between whites

and Blacks at Ossining. Judge Lasker rejected this analysis

as being premised on factually erroneous assumptions, incorrect

as a matter of law, and irrelevant (A. 155-62). He found the

analysis to be factually flawed in that (a) whites received

statistically significantly higher mean scores than Blacks and

Hispanics facility-by-facility as well as state-wide (A. 158-

59, 1934), and(b) there were "significant" disparities in the

passing rates of whites compared to Blacks and Hispanics

facility-by-facility as well as state-wide (A. 159-61, 1449).

Defendants take issue with Judge Lasker's application of the

term "significant" to passing rate disparities which, while

substantial, are not, they contend, "statistically significant"

(Br. 43). However, defendants' insistence on statistical signi

ficance is ill-founded. As Judge Friendly observed in Vulcan

10/ This form of citation is to pages of appellants' brief.

17

in holding that Judge Weinfeld's finding of the racially dis

proportionate impact of the fireman's examination was not

clearly erroneous,

It may well be that the cited figures and other more

peripheral data relied on by the district judge did

not prove a racially disproportionate impact with

complete mathematical certainty. But there is no

requirement that they should ... We must not forget

the limited office of the finding that Black and His

panic candidates did significantly worse in the

examination than others. That does not at all decide

the case; it simply places on the defendants a burden

of justification which they should not be unwilling

to assume.

490 F.2d at 393. Accord: Boston Chapter, N.A.A.C,P.,Inc. v.

Beecher, No. 74-1067 (1st Cir. Sept. 15, 1974)

[I]t can be argued that a showing of significant

disproportionality in minority employment, coupled

with even minimal proof of a higher minority failure

rate, is enough to shift to the Division of Civil

Service the burden of justification.

Slip. Op. at 5-6.

In any event, there is no dispute that the disparity in

overall pass-fail rates is statistically significant and, as

Judge Lasker held, the resulting racial/ethnic classification,

which establishes plaintiffs' prima facie case, cannot be re

butted by defendants' attempt to explain this classification

by "facility effect" (A. 161-62). The classification requires

that defendants justify the test. Bridgeport. supra, 354 F.

Supp. at 785-86; Vulcan, supra, 360 F.Supp.at 1272; Castro v.

Beecher, 459 F.2d 725, 730-31 (1st Cir. 1972).

18

Defendants also claim that the court below erred in

finding that plaintiffs had established a prima facie case

as to the examination as a vhole, and should have compared

white-minority performance subtest-by-subtest. Had it done

so, the argument goes, it would have found that as to one of

the five subtests there was no significant difference in per

formance (Br. 47). The point of this argument is puzzling

since (a) defendants reject the notion that they should re

grade the examination and make appointments on the basis of

this one subtest (Br. 30, footnote),and (b) defendants concede

that failure to prove job-relatedness on any one of the other

four subtests would invalidate the entire test (Br. 48, footnote).

Carried ^o its logical end, defendants approach would require

question-by-question comparison of white-minority performance.

Defendants, however, admit that it is "self evident" that in

terms of the impact of the disparity of scores on Blacks and

Hispanics, the only score that means anything is the score on

the test as a whole (A. 946).

As Judge Lasker correctly held, defendants' approach

is unwarranted in law and in logic (A. 162-24).

19

C. The District Court's Finding That Defendants

Did Not Meet Their Burden Of Demonstrating

The Job-relatedness Of Examination 34-944

Must Be Upheld As Not Clearly Erroneous____

The Court below devoted 23 pages of its opinion (A. 164-

87) to a detailed, carefully documented discussion of the job-

relatedness of examination 34-944. Its findings of basic fact

are amply supported by the record, and its finding of ultimate

fact, to wit, that "the probabilities in this case [of the job-

relatedness of the examination] run heavily against defendants"

and, therefore, defendants failed to meet their burden (A. 186-

87), was arrived at by the application of legal standards

approved by this Court in Chance, Vulcan, and Bridgeport.

Defendants contend that examination 34-944 met

established standards for content validity (Br. 53). The

Court below correctly summarized the relevant legal and pro

fessional standards for content validity as follows:

[T]o survive plaintiffs' challenge, 34-944 must be

shown to examine all or substantially all the critical

attributes of the sergeant position in proportion to

their relative importance to the job and at the level

of difficulty which the job demands (A. 169).

See Vulcan, supra, 360 F.Supp. at 1274 and 490 F.2d at 395;

Bridgeport, supra, 482 F.2d at 1338.

Following the approach taken by Judge Weinfeld in Vulcan,

which approach was described with approval by Judge Friendly,

490 F.2d at 395, Judge Lasker, rather than "burying himself in

20

a question-by-question analysis" of examination 34-944 to

determine if the test had content validity (id_.), placed

primary emphasis on the process by which it was created.

Concluding that "the procedures employed in constructing

examination 34-944 do not conform to professionally acceptable

and legally required standards" (A. 184), he proceeded to

inquire whether, despite the inadequacy of the procedures by

which the examination was constructed, it was in fact related

to the job of Correction Sergeant. He found that "positive

evidence of job-relatedness is conspicuous by its absence"

(A. 184) .

1. Examination 34-944 Was Not Prepared In A Manner Consistent

With Content Validity

a. No job analysis was performed.

Plaintiffs' expert testified, and the District Court

agreed, that fundamental to the construction of any examination

purporting to have content validity is a job analysis of the

position's duties which will enable examiners to formulate

questions capable of measuring the necessary characteristics

(A. 171-72, 1116, 1122). Thus, no claim of content validity

can be supported without a job analysis or detailed job des

cription giving the examination preparer adequate information

from which to select questions representing a reasonable sample

of the work required for the job. Chance, supra, 458 F.2d at

1174, Vulcan, supra, 360 F.Supp. at 1274.

21

Defendants' witnesses testified that job analysis was a

process that need not be reduced to writing but can exist in the

minds of the test constructors, that there was no job analysis

for the position of Correction Sergeant in documentary form (A.

599-600, 919-20), but that the "job audit" (A. 1516-95) KS&A

statements (A. 1332-36), class specifications (A. 1327-29) and

rule book (DX-O) constitute a job description of the job of

Correction Sergeant (A. 599). The court below rejected these

contentions. It found that these documents "do not even approxi

mate a professionally adequate job analysis", that what existed

in the minds of the test constructors was "unproven" or unimpress

ive" , that the reliance of the test constructors upon the purported

ijob analysis was "largely established" and that the "inevitable

inference, is that no adequate job analysis was performed" (A.173).

The job audits (A. 1516-95) purport to be descriptions

of what Correction Officers were observed to be doing in several

facilities (A. 174, 589). There is not a shred of evidence

about the persons who conducted the audits -- their quali

fications as either corrections experts or test construction

experts -- or about any guidelines or procedures they followed

11/

in making the audits (A. 175). The record does show that

the audits were conducted not with test construction in

mind, but rather for the purpose of determining whether various

11/ Defendants’ expert testified that the job analysis process

must be designed by a psychometric expert (A. 1046, 1048).

22

jobs in the Correction Officer series ought to be upgraded for

12/

Civil Service purposes (A. 174, 590, 1330-31).

Neither the people who took the auditors around the

facilities nor the auditors themselves wrote the examination

(A. 175, 595) .

The audits are devoted primarily to a description of

the duties of Correction Officers, not Sergeants (A. 175).

They give no indication of the relative importance of various

tasks performed by or skills required of a Sergeant, and no

hint of the degree of competency required in regard to each

skill, both essential components of job analysis (id.).

The job audits were conducted in the Spring of 1970

(A. 597-98). Kenneth Siegal, who was responsible for pre

paration of examination 34-944, testified that the job of

Sergeant changed substantially between that time and October

1972, when examination 34-944 was given (A. 174-75, 769).

Even if, in the face of all of the above, it were de

termined that the job audits did constitute evidence of an

adequate job analysis of the job of Correction Sergeant as

it existed in October 1972, defendants' contention that

12/ That the goals of a reclassification study might be incon

sistent with those of a job analysis for test construction purposes

is demonstrated by the fact that while the Sergeant's job was re

classified to the grade of 17 (A. 800), the plan for the super

vision subtest called for questions appropriate for levels 10-14,

and the plan for the report writing subtest called for questions

appropriate for an entry level investigative position (A. 199, n.

12, A . 1335) .

23

examination 34-944 was constructed in a manner consistent with

content validity must be totally disregarded for the simple

reason that, as the District Court found, defendants did not

consult the iob audits in the course of preparing the test items

(A. 175, 903-04).

The lower court found that the other documents relied

upon by defendants as parts of a job description fared no

better: the class specifications (A. 175-78) contain no

information useful for test construction (A. 175-76); the

KS&A statements (A. 1332-36) are irrelevant, both because

they are so lacking in detail and because they were not in

fact used in preparing the examination (A. 176-77, 585, 902);

the rule book (DX—0) while it contains information which

may be important to the job, is "obviously" not part of a job

analysis (A. 177).

As the District Court found, the record does not

establish that the persons who constructed the exam possessed

the kind of knowledge that would make them "living job descrip

tions" (A. 178, 599). Of the three persons from the Department

of Corrections only one, Captain Hylan Sperbeck testified.

Captain Sperback provided 14 of 75 items on Examination 34-944

(A. 982). His qualifications as a Corrections expert, or an

expert with respect to the Sergeant job, are that he started

24

as a Correction Officer in 1957, became a Sergeant in 1968,

a Lieutenant in 1972 and Captain in 1973 (A. 974). Since

March 1970, he has been head of the Training Academy (id.).

Between March, 1970 and September 1972, when preparation of

Examination 34-944 was completed, the only opportunities he

had to observe the Sergeant job, which had changed substantially

in that period (A. 769, 1460), were during five or six weekends

spent at Greenhaven and four days at Attica. The qualifications

of the other two men from the Department of Corrections, Ciuros

and Harris, are not in the record. Defendants' expert testified

however, that line officers with substantial experience in the

job would not necessarily be subject matter experts, that such

experience was highly desirable, but that such a person might

not have developed the depth of understanding that would make

him a subject matter specialist (A. 179, 1049). Plaintiffs'

expert, Dr. Richard Barrett, pointed out that people who are

too close to a job sometimes are unable to see what is truly

important, and that defendants' subject matter experts had

apparently not studied the job from the point of view of

constructing a test (A. 1134). Of the three persons from

Civil Service who worked with Corrections personnel on the

subtests on rules, correctional methods, and judgment, only

one, Kenneth Siegal, testified. His knowledge of the Sergeant

position was limited to what he might have derived from an

25

examination of job audits, class specifications, tests,

training manuals, prior examinations, and a visit to

Coxsackie, where he spent one or two hours conferring with

Sergeants (A, 179, 755-57,776-83, 8 8 8). Similarly, defendants

did not call as witnesses the persons who prepared the sub

test on supervision and preparation of written reports, which

constituted 40% of the examination, and there is no evidence

of their qualifications as either subject matter or test con

struction experts. The testimony shows, however, that the

persons who prepared these two subtests had no contact with

Corrections personnel (A. 179, 504).

The District Court found not only that the record does

not establish that the knowledge and qualifications possessed

by the test constructors constituted a job analysis, but that

"a contrary inference is warranted" (A. 180).

The conclusion of court below that defendants had not

performed an adequate job analysis (A. 180) is clearly sub

stantiated by the record.

b. The type of examination, its scope, the weight of

the subtests and the pass-point were not determined

in a manner consistent with content validity.

That examination 34-944 was not prepared in a manner

consistent with content validity is further evidenced by the

"lack of professionalism" which characterized the way in which

26

the scope of the examination, the method of evaluation (i.e.,

a written exam as the sole measure), the number of items on

each subtest, and the cut-off score were determined (A. 180).

At last since 1964, the promotional examination for

the Sergeant position has been a written multiple-choice

test (A. 1469). Kenneth Siegal testified that the decision

to give a written test was "a decision of history" (A. 933).

The Training Course Textbook used by the Civil Service Com

mission states that "[a] determination to use a written test,

however, should be based on a conscious decision that the KS&A

required on the job can best be measured by a written test (A.

1728). Plaintiffs' expert testified that very rarely is only

one procedure, such as written examination, used in selection,

and that where it is, it is inappropriate to do so (A. 1161-62).

While performance ratings may be used as part of the promotional

process (Civil Service Law §52(2); A. 907-08)/ here they were

not (A. 617-18, 908, A. 180-81).

Like the decision to rely exclusively on a written

examination, the court below found that the determination

of the scope and organization of the exam was merely a

"slavish imitation of earlier examinations which ... in

this case indicates an alarming lack of independent thought

about how to assure that 34-944 was job-related (A. 181-82).

27

For an examination to be content valid, it must

consist of a representative sampling of those knowledge and

skills which are deemed critical to successful performance

of the job being tested for (A. 1114, 1763). Despite the

fact that, as Kenneth Siegal recognized, the Sergeant's job

had changed significantly in the last ten years, indeed in

the last two years, (A. 769, 936), the fact is that the

scope of the 1972 examination was identical to that of the

1964, 1968 and 1970 tests, except that some examinations

covered interpretation of written materials in lieu of or in

addition to preparation of written reports (A. 936, 1469).

As the District Court found, this similarity was the result

of the test planners' heavy reliance on prior scope statements

(A. 182, 766-67, 895 ) .

The relative weight given to each critical element of

job performance is related to the importance of a representa

tive sampling of the various elements. The portion of the

examination devoted to measuring a particular group of

knowledges, skills and abilities must bear some relation to

their importance in performing the job. Samuel Taylor, who

has overall responsibility for the construction and validation

of Civil Service tests, assumed that the persons constructing

28

examination 34-944 made a conscious determination that each

of the five subtests was equally important (A. 613). But

in fact 15 items were used on each subtest only because

using the same number of items made it easier to do certain

types of analyses and Civil Service always works on the

basis of 15 questions per subtest (A. 802-03, 936). Indeed,

in the absence of a job analysis which states the relative

importance of various skills and knowledges, it would have

been impossible to construct the examination on any basis

other than guess-work (A. 183).

The fact that 60% of the items on the Sergeant exams

were also on the Lieutenant exam (A.771-72,13 5 3 ) further points

up defendants’ failure to tailor examination 34-944 to the job

for which it was testing (A. 183).

The District Court found that "the decision to establish

the passing score of 70% subordinates the goal of job-related-

ness to that of administrative convenience" (A. 183). The

Civil Service training course textbook states:

"We have seen that the validity of a test is

related to the pass point selected . . .

A . Objectives in Setting a Pass Point

1. We want to set the passing point so that

a high percentage of ihose who pass are

29

competent to do the job and a low percentage

of those who pass are incompetent to do the

job.

2. We also want to set the passing point so that

relatively few of those competent to do the

job fail the test and most of those who fail

are incompetent to do the job." (A.1767).

Plaintiffs' expert witness expressed the same view (A. 1118-

19, 1161-62). Samuel Taylor and Siegal both testified that

the pass point on examination 34-944 was set at the maximum

permitted by law (A. 760); and that the decision to do so was

made after the examination was scored, on the ground that such

a passing score would create a pool of passing candidates

sufficient to meet the needs of the Corrections Department

(A. 616, 760-763). Taylor admitted that the function of the

passing score was more to regulate the number of people who

would be eligible for the job than to indicate whether or

not a candidate is qualified. The court below found that

this approach "departs from the requirement, imposed by law,

that such decisions be made so as to further the paramount

goal of job-relatedness " (A. 184).

30

2. Defendants Have Not Shown Examination 34-944 To Be

Job-Related.

Having found that the preparation of examination

did not conform to professionally acceptable or legally

required standards, the court below proceeded to consider

whether the examination was nevertheless in fact related

to the Sergeant job. Far from finding convincing evidence

of job-relatedness, as required by the sliding scale approach

of Vulcan, supra, 490 F.2d at 396, Judge Lasker found that

"positive evidence of job-relatedness is conspicuous by its

absence" (A. 184).

Defendants' expert refused to testify that the exam

was job-related (A. 1046). Plaintiffs' expert gave his

opinion (1 ) there had been no showing that the test was job-

related and (2 ) there was substantial reason to doubt that

the test was in fact valid (A. 1132-33).

Witnesses for both sides testified that there were a

substantial number of questions about laws, rules and regu

lations that a Sergeant would have no occasion to apply

(A. 365-67, 369-70, 789, 1010). Dr. Barrett testified that

the subtest on laws, rules and regulations (A. 1356-58, NOs.l

-15) seemed to deal with matters that were trivial or had

nothing to do with a Sergeant's job (A. 1140-41). He also

31

testified that to the extent that a test contains items which

a person would not have to apply, it cannot be claimed to have

content validity (A. 1141-42), With respect to the subtest on

modern correctional methods(A. 1358-60, Nos. 16-30), Dr. Barrett

pointed out certain specific defects in some of the items and

possible inconsistencies between items (A. 1146-50). As to the

subtest on supervision (A. 1360-62, Nos. 31-45), Dr. Barrett

pointed out that there is no evidence that people who follow

one set of principles are better supervisors than persons who

follow another. Furthermore, the supervisor-subordinate re

lationship is so complex that it cannot be tested with the

type of items on the subtest (A. 1151). With respect to the

report preparation subtest (A. 1363-67, Nos. 46-60), five of

the items were poorly constructed in that they put the test-

wise taker at an advantage (A. 1156-58). Dr. Barrett testified

that the fifth subtest, on judgment (A. 1369-71), was poorly

constructed, principally because persons do not necessarily

act in judgment situations the way they say, on examination,

that they would act (A. 1159-60).

It was Dr. Barrett's opinion that examination 34-944

would not meet professional standards of test development

(A. 1160-61). The District Court agreed (A. 185-86).

32

Judge Lasker found of even greater import the fact

that examination 34-944 failed to test several of the traits,

skills and abilities that were identified by witnesses for

both sides as crucial for success as a Correction Sergeant.

Among these are leadership, empathy, understanding of the re

socialization process, ability to rela.te to people of different

backgrounds and to treat them fairly, and ability to function

in crisis situations (A. 311, 354, 457, 545, 938). By omitting

consideration of these essential qualities, he concluded, the

test performance does not reflect a true and fair estimate of

.12/

the overall relative qualifications of candidates (A. 186).

13/ Judge Newman, in Bridgeport, supra, held that an examina

tion which had not been shown to sample the qualities necessary

for successful performance could not meet the standard for job—

relatedness, stating:

There has been no showing that the exam measures with

proper relative emphasis all or even most of the essen

tial areas of knowledge and the traits needed for proper

job performance. Even if the exam need not be comprehen

sive as to content or constructs, the evidence does not

indicate whether the few areas of knowledge and the few

traits measured are the ones that will identify suitable

candidates for the job of patrolman. This is not to

doubt that arithmetic and reading comprehension are im

portant for policemen. But without evidence, it cannot

be determined whether this exam, in identifying those

with skill in these areas, might not screen out others,

somewhat but not seriously deficient in these areas, who

would excel as policemen because of their talents in

areas not tested for at all. An exam of this sort,which

does not attempt to be comprehensive in testing for con

tent or constructs, employs a sampling approach. Such

an exam might, in some circumstances, be shown to meet

the standard of job relatedness. But the evidence does

not establish the representativeness of the knowledge or

traits sampled by the exam used here. 354 F.Supp. at 792

33

In their brief, defendants attempt to establish the

job-relatedness of examination 34-944 by comparing various

\

Sergeants' activities that were mentioned at trial or in

individual post descriptions prepared at correctional

facilities (A. 1788-1921) with the KS&A statements (A. 1332-

36) (Br. 96-103). Such a comparison, they argue, shows that

examination 34-944 tests for all the tasks a Sergeant performs.

This argument must fail because there is no support for its

underlying premises. First, there is nothing in the record

to support the premise that the duties statements are accurate

job descriptions. Siegal testified that the identity of the

persons who prepared them was not known (A. 863). Just as with

job audits there is no evidence of any guidelines or procedures

followed in preparing them. Secondly, and more important, the

record is similarly devoid of evidence to support the premise

that the KS&A statements bear any relationship to examination

3 4-9 4 4 . To the contrary, the District Court found that the

KS&A statements were so lacking in detail as to serve no use

ful purpose and further, that they were not relied on in

preparing the test (A. 177).

In view of the above, it is difficult to see how, on

this record, the court below could have arrived at any con

clusion other than that defendants failed to meet the burden

of demonstrating job-relatedness of examination 34-944.

34

II. THE DISTRICT COURT'S DEFINITION OF

THE CLASS WAS NOT CLEARLY ERRONEOUS

Defendants' contention that the class should have

been limited to Black Correction Officers at Ossining, based

as it is on the argument that they are the only minorities

with respect to which examination 34-944 had disparate impact,

must fail with the rejection of that argument, (See pp. 16-18,

supra.).

Defendants also claim that it was error to include

in the class persons who passed the exam but scored too low

to be appointed. The District Court's finding that the

interests of such persons are identical to plaintiffs'

interests (A. 199 n.15) is not clearly erroneous. Contrary

to defendants' statements that the existence of such a class

is speculative (Br. 109), there was undisputed evidence as

to the number of persons to be appointed (see p . 1 0 , supra);

accordingly, the persons who ranked too low can be readily

identified.

III. THE DISTRICT COURT DID NOT ABUSE ITS DISCRETION

IN ORDERING DEFENDANTS TO PREPARE A CRITERION-

VALIDATED EXAMINATION AND IN MANDATING APPOINT

MENT RATIOS TO CURE EFFECTS OF PAST DISCRIMINATION

A . Applicable Legal Principles

This Court has recognized as "the basic tenet" in passing

upon relief granted by a trial court in a case of this sort that

35

"the district court, sitting as a court of equity, has wide

power and discretion to fashion its decree not only to pro

hibit present discrimination but to eradicate the effects of

past discriminatory practices", Bridgeport, supra, 482 F.2d

at 1340, citing Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145, 154

(1965) and United States v. Wood, Wire & Metal Lathers. Local

46. 471 F.2d 408, 413 (2d Cir.)> cert, denied. 412 U.S. 939

(1973) ("Lathers"). In Vulcan, this Court, quoting Inter

national Salt Co. v. United States. 332 U.S. 392, 400 (1947),

stated, "The framing of decrees should take place in the

District rather than in the Appellate Courts". 490 F.2d at

399. Most recently,in Rios v. Enterprise Association Steam-

fitters Local 638. 501 F.2d 622, 631 (1974) ("Rios"), this

Court has reiterated its determination to leave the nature

and extent of relief from past discrimination to the sound

discretion of the trial judge.

The above cited cases are ample authority for the

proposition that the determination of procedures to be used

in developing a job-related test is confided to the lower

court's sound discretion.

As to the promotional preferences mandated by the

District Court, this Court has repeatedly affirmed relief

of this type. In the private employment context, it has

held that "while quotas to attain racial balance are

36

forbidden, quotas to correct past discrimination are not",

Lathers, supra, 471 F.2d at 413. See also, Rios, supra,

501 F .2d at 629 and cases cited therein. It has noted with

full approval that"Section 1983 cases have also granted

relief by sanctioning quotas aimed at curing past discrimi

nation," Bridgeport, supra, 482 F.2d at 1340. In each of

the cited cases, this Court affirmed (in relevant part)

rigorous decrees including preferential hiring requirements

or quotas. The element that makes the affirmative pro

visions both lawful and necessary is proof of prior discri

mination or its continuing effects. Louisiana v. United

States. supra; Bridgeport, supra, 482 F.2d at 1340.

B. The Court Below Did Not Abuse Its Discretion

In Requiring That New Job Selection Procedures

Be Validated By Criterion-Related Techniques

The District Court's decree orders defendants to

develop, in the shortest practicable time, a job selection

procedure, which may include a written examination and/or

other selection instruments (A. 242). The decree requires

that before such a procedure is used for promotional purposes

it must be validated, and that to the extent feasible, such

validation studies must be performed by means of empirical,

37

criterion-related validation techniques (A. 242-43). In

arguing that this requirement constitutes error and abuse

of discretion, defendants confuse the issues of liability

and remedy. It is true that this Court has, at least in

dictum, declared that a discriminatory selection procedure

can be justified by other than a showing of criterion-related

validity. Vulcan, supra. 490 F.2d at 395. However, since

liability has been established, the trial court must fashion

that relief which, on the facts of the case, appears most

likely to right the wrong. Rios, supra. 501 F.2d at 631

14/

14/ There are two forms of criterion-related validation,

predictive and concurrent.

Predictive validation consists of a comparison

between the examination scores and the subsequent

job performance of those applicants who are hired.

If there is a sufficient correlation between test

scores and job performance, the examination is

considered to be a valid or job-related one.

Concurrent validation requires the administration

of the examination to a group of current employees

and a comparison between their relative scores and

relative performance on the job.

Vulcan, supra. 360 F. Supp. at 1273. Both forms require

the identification of criteria which indicate successful

job performance and the matching of test scores with job

performance ratings on the basis of the selected criteria

to determine the degree of correlation between the two.

Bridgeport, supra. 482 F.2d at 1337.

- 38

Decisions in this Circuit and the EEOC Guidelines

agree that cr iter ion ̂-related validation is the best method

of assuring job-relatedness of a selection procedure.

Bridgeport, supra. 482 F.2d at 1337 and 354 F.Supp. at 788;

Vulcan, supra. 360 F.Supp. at 1273; 29 C.F.R. at §1607.5(a).

While this Court has observed that this form of validation

may in some circumstances be difficult, Vulcan. supra. 490

F.2d at 395 and n.10, Judge Lasker's determination as to

its appropriateness in this case is amply buttressed by the

record.

Plaintiffs' expert, Dr. Barrett, testified that a

number of agencies are developing predictively valid select

ion instruments for law enforcement field positions (A. 1178-

80) .

He described the methods by which defendants could

begin to develop criterion-validated selection instruments

for the Sergeant position, comparing the performance of the

present provisional Sergeants with their scores on examinations

34-944 and ratings of their performance as Correction Officers

15/

(A. 1169-1173) .

15/ Cf. Attica, The Official Report of the New York State Special

Commission on Attica (1972), in a discussion of "the department

as it exists, what the problems are", at p.26:

For promotion, evaluations of an officer's performance

on the job and his ability to relate to inmates were

not considered. Written examinations were the key,

and after three years' service any Correction Officer

could take an exam for Sergeant.

39

Kenneth SiegaX indicated that if he had a free hand

l i

in developing a selection process for Correction Sergeant,

he would develop a criterion-validated procedure (A. 957).

Samuel Taylor testified that at least since early 1972 he

has believed that criterion validation of the Correction

Officers series of exams is feasible (A. 651). Indeed, the

Department of Civil Service has a grant from the federal

government under the Intergovernmental Personnel Act to

develop criterion-validated selection procedures for this

series, including the Sergeant job (A. 639-41, 1458-67).

Finally, defendants protestations of the inappropriate

ness (Br. 118) and burdensomeness (Br. 119-20) of the trial

court's order must be viewed in the light of the State's

adamant insistence on defending an examination which was

proved to be woefully inadequate, to the extent of diverting

"for well over a year" the resources of the Civil Service

Department from the preparation of a criterion-validated

selection device to the defense of this case (Br. 160,

second footnote).

C . The Provisions Of The Decree For The Promotion Of

Class Members Were Both Proper And Necessary As Part

Of The Equitable Remedy

The District Court's decree mandates that at least one

Black or Hispanic be appointed to the position of Correction

40

Sergeant (Male) for each three whites so appointed until the

combined percentage of Black and Hispanics in that rank is

equal to the combined percentage of Blacks and Hispanics in

the rank of Correction Officer (Male) (A. 243-44). This

requirement is fully justified by the facts of record and

finds ample precedent in the decisions of this Court.

There is uncontroverted evidence that at least since

1961, there have been only two Blacks and no Hispanics per

manently appointed to the rank of Sergeant or above in the

entire New York State prison system (see pp. 7-8, supra) .

There is substantial unrebutted evidence that this

startling disparity has been brought about by discriminatory,

non-job-related Civil Service examinations. Of the 46 Blacks

and Hispanics who took the 1970 Sergeant exam, not one passed

(see pp. 10-11), supra). Named plaintiffs and five other

Blacks testified they took the exam for Sergeant as many as

four times and never scored high enough to be appointed (see

pp. 13-14, supra). The record is silent as to the job-related-

ness of the previous exams except for substantial evidence that

they were cut from'the same cloth as examination 3 4 - 9 4 4 (pp.13,

27-28, supra). The trial court found that "while there is

evidence of the discriminatory impact of the earlier tests,

there is no evidence as to their job-relatedness" (A. 181-82).

41

in view of the gross underrepresentation of minorities

in the Sergeant rank brought about by past unlawful

practices, as well as by examination 34-944, it was in

cumbent upon the court below to grant relief that would

not only prohibit future discrimination but would also

eliminate the effects of past violations; anything less

would be "illusory and inadequate as a remedy." Rios.,

supra, 501 F.2d at 631.

in simple numerical terms the relief granted is

eminently reasonable and far less than other courts have

granted. In Bridgeport, this Court affirmed a quota for

hiring that required 50% of the first ten vacancies, 75%

of the next twenty, and 50% of some next subsequent

vacancies to be awarded to minority group members. 354 F

16/

Supp. 778, 798-799. In Lathe.ES. this Court upheld an

order requiring immediate issuance of 10 0 work permits to

16/ These numbers represent a hiring quota. This Cour

reversed the district judge's quota on promotions,

reversal was not based on any doubt that such a remedy,

where appropriately supported, would be lawful and necessary

Rather, the Court's holding was grounded on the fact that

the promotional examination had not been shown to be discnm

inatory. 482 F.2d at 1341

42

minority group persons, and a one-for-one quota on

issuance of subsequent permits until 1975, 408 F.2d at

412. In Carter v. Gallagher 452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir. 1971

and rehearing en banc, 1972), an absolute preference (100%)

was struck down but a one-for-two quota was substituted by

the Court of Appeals, 452 F.2d at 331. In Commonwealth of

Pennsylvania v. O'Neill, the Third Circuit upheld a one-

for-two hiring order by an equally divided Court en banc,

348 F.Supp. 1084, 1105 (E.D. Pa. 1972), aff'd in pertinent

17/

part, 473 F.2d 1029 (1973). These figures are in no way

unusual, but rather reflect typical affirmative remedial

provisions in recent decrees.

In Bridqeport this Court specifically enumerated the

factors that persuaded it to approve Judge Newman's hiring

quota. Because of the close similarity of the factual

context of that action to the case at bar, we may apply

the same factors to the present record.

First, the Court noted that

the defendants were employing an archaic

test which was not validated and which . . .

17/ The district court’s similar ratio for promotions

was vacated. As in Bridgeport, the reason was a finding

by the Court of Appeals that no promotional discrimination

had been shown, 473 F.2d at 1031.

43

was not job related. Attacks by Blacks and

other minorities upon examinations emphasizing

verbal skills and not testing the professional

skills of the vocation applied for, have been

under increasing attack, and the failure here

of the defendants to recognize the increasing

evidence that tests of this type have an innate

cultural bias, cannot be overlooked. 482 F.2d

at 1340.

Examination 34-944 and other recent Sergeant examinations were