City of New York Board of Education v. Harris Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

December 18, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. City of New York Board of Education v. Harris Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae, 1979. a45cd970-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0dc73601-6f3f-4103-b27f-9d53448d0ac3/city-of-new-york-board-of-education-v-harris-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

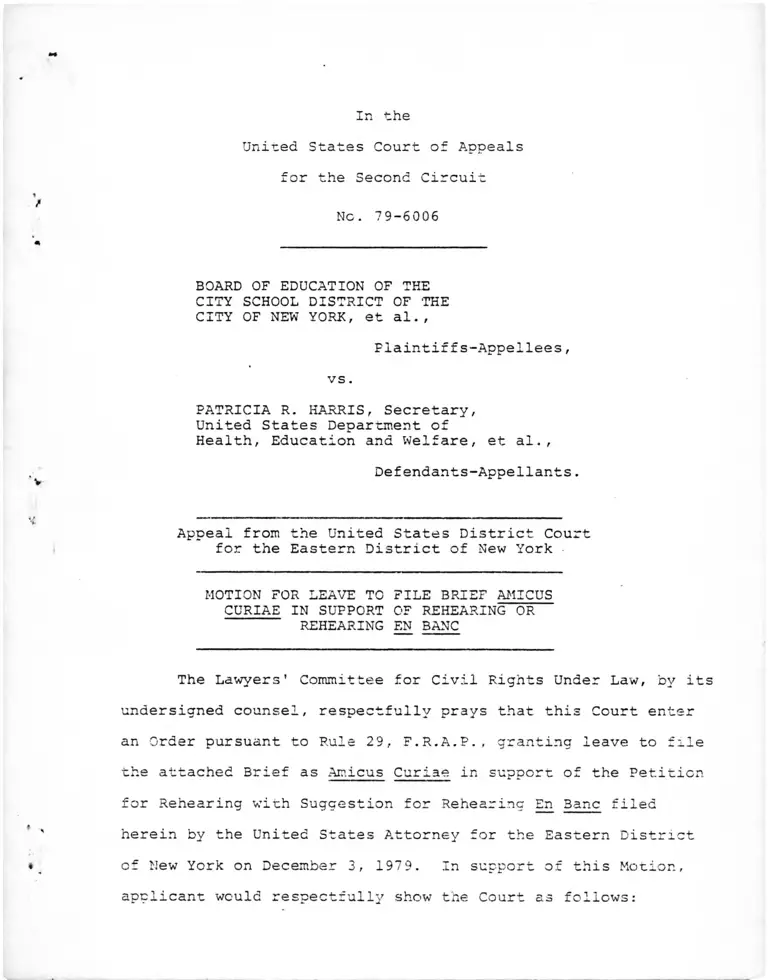

In the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Second Circuit

No. 79-6006

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE

CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT OF THE

CITY OF NEW YORK, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

vs.

PATRICIA R. HARRIS, Secretary,

United States Department of

Health, Education and Welfare, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

%

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of New York -

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICUS

CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF REHEARING OR

REHEARING EN BANC

The Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, by its

undersigned counsel, respectfully prays that this Court enter

an Order pursuant to Rule 29, F.R.A.P., granting leave to file

the attached Brief as Amicus Curiae in support of the Petition

for Rehearing with Suggestion for Rehearing En 3anc filed

herein by the United States Attorney for the Eastern District

« of New York on December 3, 1979. In support of this Motion,

applicant would respectfully show the Court as follows:

1. The Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

was organized in 1963 at the request of President John F.

Kennedy to involve private attorneys throughout the country in

the national effort to assure civil rights to all Americans.

The Committee's membership today includes former Attorneys

or Solicitors General, past Presidents of the American Bar

Association, law school deans, and many of the nation's leading

lawyers. Through its national office in Washington, D.C., and

its offices in Jackson, Mississippi and eight other cities, the

Lawyers' Committee over the past 16 years has enlisted the

services of over a thousand members of the private bar in

addressing the legal problems of minorities and the poor in

education, employment, voting, housing, municipal services, the

administration of justice, and law enforcement.

2. Historically, the Lawyers' Committee has strongly

endorsed vigorous action by the Executive and Legislative

branches to support school desegregation. We believe that federal

grant-in-aid programs like the Emergency School Aid Act (ESAA),

which specify conditions of effective integration which must

be satisfied if a recipient is to be eligible for funds, are

proper and desirable mechanisms to implement the national policy

favoring desegregation. In 1970, the Lawyers' Committee, with

the help of hundreds of volunteer attorneys, worked with other

civil rights groups to investigate the operation of the federal

desegregation grant scheme which preceded ESAA: the Emergency

School Assistance Program (ESAP). That effort documented

administrative failure to enforce provisions of the ESAP

-2 -

regulations which had been designed, on paper, to insure that

school districts receiving funds were meeting desegregation

* /requirements.— The inclusion of specific ineligibility

conditions and the strict requirements for a waiver of

ineligibility written into the ESAA statute were, in part, a

Congressional response to that study.

3. In the Committee’s view, these features have made the

ESAA program a particularly effective vehicle for ending racial

isolation and discrimination within school districts which seek

funds — as most districts with minority student populations do.

Our interest in maintaining this aspect of the program led the

Committee to file a Brief Amicus Curiae in the Supreme Court of

the United States in Board of Education of New York v. Harris,

48 U.S.L.W. 4035 (November 28 , 1979) ("ESAA I") , to support this

Court's ruling, 584 F.2d 576 (2d Cir. 1978), that the specific

ineligibility language of the statute does not incorporate

constitutional standards requiring a showing of intentional

discrimination.

4. The same concern prompts our participation in this

appeal. The November 19 ruling of the panel majority not only

conflicts with the rationale of the Supreme Court's decision

in ESAA I; it also vitiates the scheme of the statute by

requiring the Office of Education to grant waivers of ineligi

bility whenever a recipient agrees in principle to cease a

V Washington Research Project, et al., THE EMERGENCY SCHOOL

ASSISTANCE PROGRAM: AN EVALUATION (1970). See also,

Washington Research Project, et al., THE STATUS OF SCHOOL

DESEGREGATION IN THE SOUTH, 1970 (1970).

-3-

discriminatory practice or policy, even if complete elimination

of the illegal conduct throughout a school system will not

occur for several years.

5. This Motion and Brief could not be filed within the

period allowed by Rule 40, F.R.A.P. for the filing of a timely

Petition for Rehearing. The staff of the Lawyers' Committee did

not learn of the panel's decision until the afternoon of

November 30. Under the organization's procedures, no amicus

brief may be filed unless the approval of a subcommittee of its

Trustees (which was promptly sought) is first obtained. No

prejudice will result to appellees, however, since applicant's

counsel is advised that as of the date this Motion is being

prepared, no response to the Petition for Rehearing has been

requested and "a petition for rehearing will ordinarily not be

granted in the absence of such a request." F.R.A.P. 40(a).

WHEREFORE, for these reasons, the Lawyers' Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law respectfully prays that the Court grant

leave to file the attached Brief Amicus Curiae.

Respectfully submitted,

JOHN B. JONES, JR.

NORMAN REDLICH

Co-Chairmen

BURKE MARSHALL

Trustee

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

Director

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

Staff Attorney

LAWYERS' COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL

RIGHTS UNDER LAW

520 Woodward Building

733 - 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

n the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Second Circuit

No. 79-6006

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE

CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT OF THE

CITY OF NEW YORK, et al.,

Plaintiff s-Appellees,

vs.

PATRICIA R. HARRIS, Secretary,

United States Department of

Health, Education and Welfare, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of New York

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE LAWYERS'

COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW IN

SUPPORT OF PETITION FOR REHEARING OR

REHEARING EN BANC

JOHN B. JONES, JR.

NORMAN REDLICH

Co-Chairmen

BURKE MARSHALL

Trustee

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

Director

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

Staff Attorney

LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL

RIGHTS UNDER LAW

520 Woodward Building

733 - 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

INDEX

Page

Interest of Amicus Curiae ............................. 1

Statement of Facts .................................... 2

REASONS FOR GRANTING REHEARING

Introduction....................................... 4

I The Issue on Rehearing is of Critical

Significance to the National Effort to

Eliminate Racial Discrimination from

Public School Systems........................ 4

II The Ruling of the Panel Conflicts with the

Subsequent Supreme Court Decision in

Board of Education v. Harris.................. 8

III The Interpretation of the Panel Majority

Misconstrues the Relevant Legislative

History......................................

IV The Decision of the Panel Rests Upon A

Fundamental Misconception Regarding the

Process of Faculty Assignment............... 13

Conclusion ............................................. 15

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Adams v. Califano, 430 F. Supp. 118 (D.D.C. 1977)...... g

Adams v. Richardson, 351 F. Supp. 636 (D.D.C. 1972),

aff'd 480 F.2d 1159 (D.C. Cir. 1973) (en banc).... g

Adams v. Weinberger, 391 F. Supp. 269 (D.D.C. 1975).... g

Board of Education v. Califano, 584 F.2d 576

(2d Cir. 1978), aff'd 48 U.S.L.W. 4035

(November 28, 1979)................................ I4

Board of Education v. Harris, 48 U.S.L.W. 4035

(November 28, 197 9)................................ 8, 9, 10,

14 *Brown v. Weinberger, 417 F. Supp. 1215

(D.D.C. 1976) 2

Cases (continued) Pa^e

Cannon v. University of Chicago, 60 L. Ed.

2d 560 (1979)....................................... 6

Kelsey v. Weinberger, 498 F.2d 701 (D.C. Cir.

1974)............................................... 6

United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate

School Dist., 406 F.2d 1086 (5th Cir.),

cert, denied, 395 U.S. 907 (1969).................. 14

Statutes and Regulations:

20 U.S.C.S. §1605(d) (1) (Supp. 1978)................. 3

20 U.S.C.S. §§1605(d)(1)(A) - (D)(Supp. 1978)............ 7

20 U.S.C.S. §1605(d) (1) (B) (Supp. 1978)................... 2

20 U.S.C.S. §§3191-3207.................................. 2

42 U.S.C. §2 00 0d........................................ 2

45 C.F.R. §185.44 (d) (3) (1978)........................... 3

Other Authorities: * S.

- 118 CONG. REC. 5983 (February 29, 1972).................. 12

117 CONG. REC. 10759 (April 19, 1971).................... 12

H.R. REP. NO. 95-1137, 95th Cong., 1st Sess. (1971),

reprinted in [1978] U.S. CODE CONG. & ADM.

NEWS................................................ 13

S. REP. NO. 92-604 , 92d Cong., 2d Sess. (1972)......... 12

Part 4: Emergency School Aid Act, Hearings on

H.R. 15 Before the Subcommittee on Elementary,

Secondary and Vocational Education of the

House Comm, on Education and Labor, 95th Cong.,

1st Sess. (1977).................................... 5

Washington Research Project, et al., THE EMERGENCY

SCHOOL ASSISTANCE PROGRAM: AN EVALUATION (1970)... 11

-ii-

In the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Second Circuit

No. 79-6006

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE

CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT OF THE

CITY OF NEW YORK, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

vs.

PATRICIA R. HARRIS, Secretary

United States Department of

Health, Education and Welfare, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of New York

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE LAWYERS'

COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW IN

SUPPORT OF PETITION FOR REHEARING OR

REHEARING EN BANC

Interest of Amicus Curiae

The interest of the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights

Under Law in the instant matter is set forth in the attached

Motion for Leave to File this Brief.

Statement of Facts

Following an investigation into the New York City school

system's compliance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d, the Office of Civil Rights, HEW,

notified the district in 1976 that there was reason to believe

that the system had, inter alia, assigned faculty members on

the basis of race. Negotiations with school officials

resulted in a 1977 "Memorandum of Understanding" pursuant to

which all schools were by 1980 to have faculties whose respective

racial compositions did not vary by more than five percentage

points from the systemwide faculty racial makeup. This agree

ment averted formal Title VI enforcement proceedings to

terminate all federal financial assistance to the district.

See Brown v. Weinberger, 417 F. Supp. 1215 (D.D.C. 1976) .

In the spring of 1978, the district applied for funds

under the Emergency School Aid Act of 1972 (ESAA). Relying

upon the results of the Title VI investigation, it was held

ineligible because it had, after the passage of the Act,

. . . engaged in discrimination based

upon race, color, or national origin

in the hiring, promotion, or assignment

of employees of the agency . . . .

20 U.S.C.S. §1605 (d)(1)(B) (Supp. 1978) (emphasis added)

1/ In November, 1978, ESAA was reauthorized in the Education

Amendments of 1978 without material change. It is now codified

at 20 U.S.C. §§ 3191-3207. Citations in this Brief are to the

codification in effect at the time of the events in question.

- 2 -

New York accordingly applied for a waiver pursuant to the

statutory provision that an ineligible district

. . . may make application for a

waiver of ineligibility, which applica

tion shall . . . contain such information

and assurances as the Secretary [of HEW]

shall require by regulation in order to

insure that any practice, policy, or

procedure, or other activity resulting in

the ineligibility has ceased to exist or

occur . . . .

20 U.S.C.S §1605 (d)(1) (Supp. 1978) (emphasis added). HEW has

adopted regulations under this section which require that an

applicant held ineligible because of faculty assignments which

make its schools racially identifiable must complete the

process of reassignment, so that faculty racial composition at

every school is between 75% and 125% of the system-wide ratio,

in order to qualify for a waiver. 45 C.F.R. §185.44(d)(3)(1973).

The New York City waiver request was denied because the

"Memorandum of Understanding" would not result in faculty

reassignments within the limits permitted by the waiver regula

tion until 1980. Thus, according to HEW, the disqualifying

"practice, policy, or procedure, or other activity resulting in

the ineligibility" could not be said to have "ceased to exist

or occur."

The school district brought suit to challenge HEW's

rulings and the government appealed a decision invalidating

the waiver regulation to this Court. On November 19, 1979, a

divided panel (Oakes, J., dissenting) affirmed the district

court. The majority opinion holds that the waiver regulation,

-3-

as interpreted by HEW, is invalid and inconsistent with the

statute which, in the majority's view, requires only that an

applicant rescind a formal policy of discrimination and

commence corrective action in order to qualify for a waiver.

The government new seeks rehearing or rehearing en banc of

that determination.

REASONS FOR GRANTING REHEARING

Introduction

The government's Petition sets out in detail the errors

upon which the panel majority's decision rests. Amicus will

not rehearse all of the arguments here, nor address the

questions of jurisdiction or basis for issuance of an

injunction by the district court. Our participation at this

stage of the litigation is a consequence of the great public

importance of the issue of statutory construction — a charac

terization which we make on the basis of our nationwide

perspective and experience.

I

The Issue of Rehearing Is of

Critical Significance to the

National Effort to Eliminate

Racial Discrimination from

Puolic School Systems_______

The Lawyers' Committee believes that ESAA has proved to

be an effective instrument and incentive for school desegre

gation, primarily because the law establishes conditions of

eligibility for funding which are specific and which can be

verified rapidly in pre-grant reviews of applicants. The

-4-

Director of the Office for Civil Rights, HEW, testified in

1977 that

[i]n requiring compliance with specific

civil rights provisions as a precondition

to the award of Federal financial assistance,

the ESAA program has had a significant role

in the prevention and elimination of unlawful

discrimination. In each of the funding cycles

subsequent to the enactment of the statute,

significant numbers of students have been

reassigned from racially identifiable classes

(including racially isolated classes) and

racially identifiable special education

programs determined to be educationally un

justified. A number of comprehensive plans

have been adopted to provide equal services

to national origin minority children. Several

thousand teachers have been reassigned to

eliminate racially identifiable school staffs

and a number of affirmative action employment

programs have been adopted where dispropor

tionate demotions or dismissals of minority

faculty took place during the desegregation

of school systems. 2/

For example, during Fiscal Year 1976, 23 applicants for ESAA

funding were initially declared ineligible because of teacher

assignment problems; four determinations of ineligibility

based on applications processed for Fiscal Year 1977 as of

3 /June 8, 1977 related to faculty assignment.— Most of the

districts were able to take swift corrective action and obtain

2/ Part 4: Emergency School Aid Act., Hearings on H.R. 15

Before the Subcommittee on Elementary, Secondary and Vocational

Education of the House Comm, on Education and Labor, 95th Cong.,

1st Sess. 31-32 (1977).

3/ Id. at 29-31

-5-

. . . 4/waivers of ineligibility.—

These results have been achieved because HEW has, almost

steadfastly since the inception of the program,—^ interpreted

the language of the statute to require complete elimination

of the disqualifying condition in order for an applicant to

obtain a waiver of ineligibility. This left no room for

protracted negotiations, extended time schedules for implementa

tion of a remedy, or diversionary tactics similar to the pro

blems which have attended the Department's Title VI enforcement

6 /efforts.—' Rather than "irrevocably" barring applicants from

receiving funding, as the panel majority's opinion suggest

(typewritten slip op. at 19), the waiver requirements have

prompted immediate changes and have thus contributed to the

eradication of racial discrimination. See note 4 supra.

£/ See id. at 54:

Mr. JENNINGS. With your first point, don't you think,

even though the numbers which ultimately don't qualify

seem to be small, just the existence of these provisions

in the law causes school administrators to become

discouraged from approaching for pre-integration types

of activities. Therefore, the existence of these

things probably scares people away.

Mr. TATEL. I don't know. What I see there are 800

applications that seem to me to be a lot. When I look

at the fact that virtually all the districts we find

ineligible virtually always obtain eligibility [that]

would lead me to believe they can surmount these problems.

5/ 3ut see Kelsey v. Weinberger, 498 F.2d 701 (D.C. Cir. 1974)

6/ See Adams v. Richardson, 351 F. Supp. 636 (D.D.C. 1972),

aff1d 480 F.2d 1159 (D.C. Cir. 1973) (en banc) Adams v.

Weinberger, 391 F. Supp. 269 (D.D.C. 1975); Adams v. Califano,

430 F. Supp. 118 (D.D.C. 1977); see also, Cannon v. University

of Chicago, 60 L. Ed. 2d 560, 581-82 nn. 41-42 (1979).

-6-

The ruling of the panel, to the effect that KEW must

grant waivers of ineligibility once an applicant has agreed to

renounce the discriminatory policy and has begun the process

of eliminating discriminatory practices within its school

system, will thus have a significance far beyond the borders

of New York City, or of this Circuit. Since the statutory

waiver language applies equally to all four ineligibility

clauses,—^ the ruling cannot be confined to the area of

teacher assignment. Moreover, because the ESAA program

involves annual applications for funds, districts outside

this Circuit will inevitably seek to have HEW apply the panel's

ruling with respect to their own applications for waiver. If

HEW gives the panel's decision nationwide application, in our

view it will cripple the efficacy of the ESAA program as a

device to bring about a timely end to the discrimination

prohibited by the ineligibility clauses. Even if the government

decides to follow the ruling only within this Circuit, additional

litigation by other applicants and injunctions freezing expendi

ture of varying amounts of ESAA funds are a virtual certainty.

These events likewise will severely disrupt the progress toward

full integration which has been brought about through ESAA.

This petition, therefore, involves far more than a mistake of

concern only to private parties litigant, and the Court should

grant rehearing or rehearing en banc.

7/ 20 U.S.C.S. §§1605(d) (1) (A) - (D)(Supp. 1978).

-7-

II

The Ruling of the Panel Conflicts

With the Subsequent Supreme Court

Decision in Board of Education v.

Harris

Nine days after the panel's ruling on this appeal was

announced, the Supreme Court affirmed this Court's earlier

determination that the ESAA statutory requirements for eligi

bility did not require a showing of intentional discrimination

in order to justify denial of funds. Board of Education v.

Harris, 48 U.S.L.W. 4035 (November 28, 1979). The panel did

not have the benefit of the Supreme Court's decision in its

consideration of the current appeal. Because the majority's

reasoning is inconsistent with the opinion of the Supreme

Court, rehearing is appropriate.

The government's Petition for Rehearing sets forth the

major points of conflict between the panel's opinion and that

of the Supreme Court (see Petition at pp. 3-7), and amicus

concurs in these arguments. Additionally, we believe that a

fair reading of the panel majority's opinion reveals substantial

concern about possible inconsistency between Title VI of the

1964 Civil Rights Act and ESAA. For example:

. . . HEW's view is quite simply that

notwithstanding its approval of the

Memorandum of Understanding, its

warranty that the adoption and effectua

tion of the agreement would constitute

compliance with Title VI of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, and Title IX of the

Education Amendments of 1972, and the

Central Board's partial performance

thereof, the Central Board is not entitled

to a waiver of ineligibility during the

interim period, [typewritten slip op. at 13].

-8-

It would seem, therefore, that if the

Central Board has adopted a policy of

eliminating discrimination in a manner

approved by HEW, as demonstrated by its

commitment to the Memorandum of Under

standing, then "practices" "procedures"

and "other activities," undertaken in

furtherance of that policy cannot logi

cally be described as having resulted in

the ineligibility. Simply put, they are

not part of the problem, but part of

the cure. . . .Although this alone would

be sufficient ground on which to reject

appellant's construction there are other

reasons supporting the same result.

[Id. at 15-16; see also, id. at 19-20.]

Possible inconsistency between ESAA and Title VI, however, is

no longer an appropriate consideration supporting the majority's

construction of the ESAA statute. In Board of Educ. v. Harris,

supra, the Supreme Court dealt with the argument that ESAA and

Title VI standards were the same:

. . .Consideration of that issue would be

necessary only if there were a positive

indication either in Title VI or in ESAA

that the two Acts were intended to be

coextensive. The Board stresses the fact

that a desegregation plan approved by HEW

as sufficient under Title VI is expressly

said to satisfy the eligibility require

ments of §706(a)[20 U.S.C. §1605(a)].

The ineligibility provisions of §706(d)

[20 U.S.C. §1605(d)], however, contain

additional requirements, and there is no

indication that mere compliance with

Title VI satisfies them. Nor does the

fact that a violation of Title VI makes a

school system ineligible for ESAA funding

mean that only a Title VI violation

disqualifies.

It does make sense to us that Congress

might impose a stricter standard under

ESAA than under Title VI of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964. A violation of Title

VI may result in a cutoff of all federal

-9-

funds, and it is likely that Congress

would wish this drastic result only

when the discrimination is intentional.

In contrast, only ESAA funds are

rendered unavailable when an ESAA

violation is found. And since ESAA

funds are available for the furtherance

of a plan to combat de facto segregation,

a cutoff to the system that maintains

segregated faculties seems entirely

appropriate. . . .

48 U.S.L.W. at 4040 (emphasis in original). Thus, this Court

should reconsider its decision in this case free from any

concern about a difference in standards under ESAA and Title VI.

Ill

The Interpretation of the Panel

Majority Misconstrues the Relevant

Legislative History_______________

The opinion of the panel majority states that the legis

lative history which it reviewed shed no light on the proper

interpretation of the waiver language in §1605(d). However,

the opinion indicates—7 that only a fragment of the relevant

history was examined by the court. Its references are to one

1971 debate in the House of Representatives, and one set of

1970 hearings in each body. We believe that the panel majority

may have overlooked additional indications of the legislative

intent which are available, and which should be considered on

rehearing.

In our brief amicus curiae in the Supreme Court in

Board of Educ. v. Harris, supra, we set out the legislative

8/- Typewritten slip op. at ii n 8 and accompanying text.

-10-

history of ESAA from its conception in 1970 through its

ultimate passage in -1972. Although we did not focus on the

waiver issue, the waiver language and the four ineligibility

clauses are part of the same statutory section; hence, we

believe that reference to that discussion could be of material

assistance to this Court. The appropriate pages from our

Supreme Court brief are reproduced as an appendix to this

document

Without attempting to recapture the detail of that

presentation, at least the following is clear from the

legislative history; The regulations for the predecessor

Emergency School Assistance Program (ESAP) established in

1970 required, as a condition of eligibility for funding, that

the racial composition of teaching staffs at each school in a

system be substantially similar to the system-wide faculty

racial composition (see infra pp. 4a-5a n. 32 and accompanying

text). Nevertheless, as the program was actually implemented,

these regulations were not enforced. This lapse was

documented in a study conducted by civil rights groups— ̂

which was referred to in the Congressional debates, as well

as in reports of the General Accounting Office (see infra

pp. 6a-7a, 9a and nn. 35, 37, 43 and 44), When hearings

on the ESAA legislation were held in 1971, authors

9/ See pp. la-25a infra.

10/ Washington Research Project, et al., THE EMERGENCY SCHOOL

ASSISTANCE PROGRAM; AN EVALUATION (1970). The Lawyers'

Committee participated in the conduct of this study.

-1 1 -

of the civil rights groups' report testified extensively

about the administration's failure to carry out the regulations

(see infra pp. 8a-9a and accompanying notes). Specific

eligibility conditions were written into S 1557, a direct

predecessor of the ESAA law,— ^ according to Senator Mondale

(one of its sponsors) because of this failure to adhere to the

regulations of the prior program. 117 CONG. REC. 10759

(April 19, 1971). These same eligibility conditions and waiver

12/provisions were subsequently added to the House bill— and

this language, ultimately included in the statute, was

retained in all successive versions of the legislation.— ^

Rather than seeking to "penalize" districts (see typewritten

slip op. at 17). therefore, the desire of the Congress which

passed ESAA was, as reflected by the complete legislative history

11/ See S. REP. No. 92-604, 92d Cong., 2d Sess. 2 (1972).

12/ See infra p. 17a n. 65 and accompanying text.

— ^ When the bill was again considered by the Senate in 1972,

the ineligibility section was amended with respect to the

prohibition against transfers of property to private, segregated

schools (see infra pp. 18a-19a). Senator Chiles, who sponsored

the change, announced that he was acting in response to a

determination of ESAP ineligibility affecting Broward County,

Florida, which (after the public criticisms of ESAP's initial

implementation) had been rejected for funding both because of

(an apparently mistaken) transfer of property to a private

school, and also because of imbalanced school faculties.

Sen. Chiles stated that "[s]ince the board has taken steps to

eliminare this [latter] complaint, it assumes this will no

longer be an issue." 118 CONG. REC. 5983 (February 29, 1972).

He sought no amendment with respect to the clause creating

ineligibility by virtue of imbalanced teacher assignments nor

did any other legislator. Thus the Congress was satisfied

to resolve this kind of ineligibility by requiring reassignments

to eliminate the imbalance.

-1 2 -

history, to restrict the discretion of the Secretary to ignore

or dilute the specific eligibility requirements of the law in

the same manner as the SSAP regulations had been ignored.

One final piece of legislative history is also relevant:.

As noted by the Supreme Court in the passage from its recent

opinion quoted at pp. 6-7 of the government's Petition for

Rehearing, the House of Representatives in 1978 sought to amend

the statute to authorize the granting of waivers on the same

basis as is contemplated by the opinions of the district court

and the panel majority in this case. Not only does the failure

of the Congress to adopt this provision in the legislation it

passed suggest, in the Supreme Court's words, "that Congress

acquiesced in HEW's interpretation of the statute," but it

also reflects a recognition that a'statutory change was necessary

14/to accomplish the result sought.—

IV

The Decision of the Panel Rests

Upon a Fundamental Misconception

Regarding the Process of Faculty

Assignment_______________________

Much of the panel majority's opinion is devoted to charac

terizing HEW's interpretation of the ESAA waiver provision as

requiring that the "effects” of discriminatory faculty assign

ment practices be eliminated in order to obtain a waiver. This

discussion rests upon a conception of the assignment process

as a static, one-time event which establishes a pattern that

endures unless altered by an affirmative reassignment. But

this conception is fundamentally in error.

14/ See H.R. REP. No. 95-1137, 95th Cong., 1st Sess. 95-96

(1978). reprinted in [1978] U.S. CODE CONG. & ADM. NEWS

5065-66.

-13-

Teaching assignments in New York City, while constrained

by state law and collective bargaining agreements, etc.,— '/

16/are made on an annual basis.— ■ Thus each year that schools

with seriously racially imbalanced faculties are maintained

represents not merely a year in which the effects of a prior

discriminatory policy and practice are felt, but actually the

continuation of that policy and practice. The Chancellor

of the New York City school system is vested with the

authority necessary to alter the discriminatory practice at

17 /any time. — ■

These realities of the assignment process make it illogical

to pretend that annual maintenance of segregated faculties

is a mere "effect" of prior discrimination rather than the

renewed practice of discrimination. Compare Board of Educ. v.

Harris, supra, 48 U.S.L.W. at 4040. Only by requiring that the

reassignments necessary to eliminate racially identifiable

schools take place as a precondition to funding can HEW

15/ The provisions of state law or union contracts cannot, of

course, take precedence over the provisions of the Constitution

or of federal laws. Cf. United States v. Greenwood iMunicipal

Separate School Dist., 406 F.2d 1086 (5th Cir.), cert, denied,

395 U.S. 907 (1969).

16/ The panel majority recognizes this fact early in its

opinion (typewritten slip op. at 6) but ignores it thereafter.

17/ Board of Education v . Califano, 584 F.2d 576, 582

(2d Cir. 1978), aff1d 48 U.S.L.W. 4035 (November 23, 1979).

-14-

remain faithful to the statutory mandate that waivers be

granted only when the

practice, policy, or procedure, or other

activity resulting in the ineligibility

has ceased to exist or occur. . . .

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, amicus respectfully suggest

that the Petition for Rehearing or Rehearing En Sane should

be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

JOHN B. JONES, JR.

NORMAN REDLICH

Co-Chairmen

BURKE MARSHALL

Trustee

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

Director

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

Staff Attorney

LAWYERS' COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL

RIGHTS UNDER LAW

520 Woodward Building

733 - 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

By

Attorneys for Amicus' Curiae

-15-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 18th day of December, 1979,

I served two copies of the foregoing Motion for Leave to File

and Brief Amicus Curiae of the Lawyers' Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law in Support of Petition for Rehearing or

Rehearing En Banc upon counsel for the parties to this appeal,

by depositing same in the United States mail, first class

postage prepaid, addressed as follows:

Hon. Joseph F. Bruno

Office of the Corporation Counsel

City of New York

100 Church Street

New York, New York 10007

Hon. Richard P. Caro

Assistant United States Attorney

Eastern District of New York

225 Cadmen Plaza East

Brooklyn, New York 11201

/a) iJ L uXia

Attorney fori Proposed Amicus

B. The Legislative History

The course of ESAA was extraordinarily tortuous.

First proposed by the President in 1970, it was passed

in different versions on several occasions by each House

of Congress before ultimate enactment in 1972. Peti

tioners’ discussion of the legislative background (Br. at

19-40) barely plumbs the surface of this process, and

omits entirely consideration of the earliest legislative

efforts, which settled some of the basic issues carried

forward in later versions of the bills. In order to pre

sent the history of the statute as a whole, and to assist

the Court in tracing the background, we describe it in

some detail.

1. Spring and Summer, 1970

The concept of ESAA emerged on March 24, 1970,

when the President of the United States issued a state

ment discussing school desegregation and busing, and

outlining the policies which the national administration

would follow. Although President Nixon had strong per

sonal reservations about busing, he favored faculty inte

gration.20 “In order to give substance to these commit-

20 I have instructed the Attorney General, the Secretary of Health,

Education and Welfare, and other appropriate officials of the

- l a -

17

ments,” the President said, he would propose legislation

to make Federal funds available to school systems which

were desegregating.21

The President sent his legislation to the Congress on

May 21, 1970;22 shortly thereafter, a bill embodying his

program was introduced in the House of Representa

tives 28 It did not contain any conditions of eligibility or

specific requirement for faculty integration. Two weeks

later, in the initial hearings on the proposal, there was

skepticism about the administration’s motives and con

cern that most of the funds would go to school districts

which had resisted court decrees, without any require

ment that meaningful integration occur or that discnmi-

Government to be guided by these basic principles and policies:

Segregation of teachers must be eliminated. To this end, each

school system in this Nation, North, South, East and West,

must move immediately, as the Supreme Court has ruled, to

ward a goal under which “in each school the ratio of white to

Negro faculty members is substantially the same as it is

thoughout the system.”

1970 Pub. Papers 315 (1971).

2 il will ask Congress to divert $500 million from my previous

budget requests for other domestic programs for fiscal 1971, to

be put instead into programs for improving education m racially

impacted areas, North and South, and for assisting school

districts in meeting special problems incident to court-ordered

desegregation. For fiscal 1972, I have ordered that $1 billion

be budgeted for the same purposes.

\d. at 317.

22 Id, at 448, reprinted in Emergency School Aid Act of 1970,

Hearings on H.R. 17816 and Related Bills Before the General Sub

committee on Education of the House Comm, on Education and

Education and Labor, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. 21 (1970) [hereinafter

i (I'M TJmiqp Rp.n/ri/nas 1.

23 H.R. 17846. 91st Cong., 2d Sess. (1970), reprinted in 1970

House Hearings at 2-17.

-2a-

18

natory practices be ended.24 Although the Secretary of

HEW indicated that the Department was in the process

of preparing program criteria,25 he and other witnesses

were repeatedly asked whether Congress ought not to

include restrictions on eligibility within the legislation

itself. There was agreement that such limitations should

be contained either in the statute or in regulations.-6

Similar testimony was given before the Senate Select

Committee on Equal Educational Opportunity,-1 and was

considered by the Senate committee to which the Presi

dent’s bill had been referred.28

Congress was unable to complete action on the measure

in time for the opening of school in the Fall of 1970.

Instead, $75 million was made available for an “Emer

gency School Assistance Program” (ESAP) in the 1971

Office of Education Appropriation Act, P.L. 91-380,29

which passed both Houses over the President’s veto on

August 18, 1970. In order to have the program opera

tional when school opened, HEW on August 22, 1970

issued regulations without a prior public comment period.

35 Fed. Reg. 13442 (August 22, 1970).

-4 E.g., 1970 House Hearings at 36-37 (Rep. Hawkins), 64-65

(Rep. Ford).

25 1 9 70 House Hearings at 43.

~6 E.g., 1970 House Hearings at 66 (HEW Secretary Finch), 125

(Dr. James S. Coleman), 256 (Prof. Alexander Bickel).

^ Equal Educational Opportunity, Hearings before the Senate

Select Committee on Equal Educational Opportunity, 91st Cong.,

2d Sess. 992, 1282-83, 1462, 1518, 1528 (1970) [hereinafter cited

as Select Committee Hearings].

28 “Senator PELL. The Mondale committee and this subcommittee

are working very closely. The material furnished to the Mondale

committee will be sifted out and given to us. I wouldn’t want to

duplicate it." Emergency School Aid Act of 1970: Hearings on

S. 3888 and S. 4167 Before the Subcommittee on Education of the

Senate Comm, on Labor and Public Welfare, 91st Cong., 2d Sess.

121 (1970).

29 84 Stat. 800, reprinted in [1970] U.S. Code CONG. & Adm.

N ews 942.

-3a-

19

Those initial ESAP regulations, 45 C.F.R. Part 181

(1971), reflected both the President’s design and the

Congressional concerns which had been expressed during

the 1970 hearings and the debates on the appropriations

measure.30 The regulations contained specific eligibility-

requirements disqualifying school systems which had en

gaged in the discriminatory practices condemned in the

hearings.31 The regulations also made fully integrated

faculty assignments a precondition for assistance.32

The first attempt to establish the program took place when the

Senate amended H.R. 17399, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. (1970), the Second

forPan p S p Appropna£ ° n bllJ- to include a $150 million allocation

. ^ ESAP Program. When the bill was debated, Senator Mondale

oiced worries that these funds may be wasted in desegregated

schools which: . Have discriminatorily fired or demoted black

faculty ° r m other ways have abused and circumvented the goal

?97n f Ay in êgrf te<? ^ c a t io n .” 116 Cong. Rec. 19930 (June 16

S t BuI m/ ê A P * * * t0 prevent thisresult. But all ESAP provisions were stricken from H R 17399 in

1970?nSt h On " P?/nt ? 0rder‘ 116 C0NG- t e . 10818 (June ^ 1970) Subsequently, Senator Javits introduced them— incorpo

rating the Mondale amendments—as an amendment to HR

s r - " 970)’ the 0ffi« a pp^ Sbill, l lo Cong. Rec. 21218 (Jun6 24 t

was added to the bill the next day id \ t 21485 J d 7 ? pr0posal

was passed by the Senate, id. at 21509 (June 25 1970) The Confer!

ence Committee recommended adoption of the Senate ESAP version

h u reductl°n in funds to $75 million, which was accented hv

rqSeS- /f - v l 4581 (July 16' 1970) [House], 26215 u X 28 l ™ 1 [Senate], Followins: the President's veto, C onfess enacted

( A u S t T S 1V 5 5 S S S S ? 7 A u ^ tr i m i ? S e n , S T

53S' M5' 1166-53, 1517. 1836-37, The l e g i s u S

to r a c i a l p ,d i s S E a E ^ r i ™ " s’c h S j E * K ' E d n f j i a S

" a a s i s E U l t d e r T h e ^ E s h d i - ' W *>'

-4a-

20

The twin themes of avoiding discriminatory practices

and assuring that funds were awarded only to systems

m which effective desegregation took place continued to

be sounded throughout the subsequent Congressional de

liberations leading up to eventual adoption of ESAA.

-• r aii ana w inter, 11)70

tim® the Congress returned to its consideration

ot EbAA, substantially more information about the oper

ation of ESAP, and the need for strengthened civil

rights provisions ̂in ̂the legislation, was available. In

late 1970, six civil rights organizations released a ioint

study of ESAP’s first funding cycle.33 Their report was

highly critical of the program’s administration. Because

V ' ' 4) Contain assurances satisfactory to the Commis

sioner accompanied by such supportive information as he

may require:

‘ ~ ‘ ,(.vi) Tbat xthe local educational agency will take

effective action to ensure the assignment of staff mem-

bers who work directly with children at a school so

that the ratio of minority to nonminority group

teachers in each school, and the ratio of other staff

f* 0.1?’ are s^bstantially the same as each such ratio

» £ e t h X i “ [dJ0th' r ^

S L S ^ 1t£ i ‘ & (4 )W ) <1971)- S181-2 »f ESAP regula*

purpose of the emergency assistance to be made available

under the program described in this part is to meet sprciai

needs incident to the elimination of racial segregation ^ id

discrimination among students and faculty in elementarv and

secondary schools by contributing to the costs of new or “

o f S r 68 t0 be out b>’ l0^al educational agenciesor other agencies, organizations, or institutions and designed

fo™s* of H SUCCeSSfdese9regation and the elimination of all

forms of discrimination in the schools on the basis of students

s ^ S f bein? members 0f a ^oup. [emphasis

33 Washington Research Project, et al

Assistance Program, An E valuation

-. T he E mergency School

(1970).

-5a-

21

of the desire to distribute funds by the beginning of the

fad semester, it charged, money had been practically

given away without either an evaluation of contemplated

program quality or adequate civil rights protections.34

ihese allegations figured prominently in the next round

of hearings and debates on the proposed (authorizing)

legislation.35 6

A new version of the bill had been introduced in the

House of Representatives on September 24, 1970 H R

19446, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. (1970) at that time con

tained no conditions of eligibility similar to those now

part of ESAA. However, as knowledge of the ESAP

fiasco spread, modifications were made by the subcom

mittee to which the bill had been referred. See H.R. R e p .

No 91-1634, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. 8 (1970). When the

bill was reported to the floor, Representative Pucinski

stated this explicitly.36 During the debates which pre

ceded passage of the measure on December 21 1970 116

Cong . R ec . 43145, other members of the House exhibited

34 Id. at 14-17. See also, Washington Research Project et al. The

Status of School Desegregation in the Sooth, 1970 '(1970)'.

s r ^ ubuc wet̂ ^ S : vM 2r s £

1917\ Senate Hearings]-, 116 Cong. Rec 42218

S K rpeP' P,UCmSkl ’ 42222’ 42223 ,ReP- Hawkins), 42222 42224

w n ’ 42231 (Rep- Reid> D ecem ber 17,’ 48143 (Rep. Ryan) (December 21, 1970).

36 Mf- PUCINSKI. . . . a task force has made a study of the $7t»

million and the task force was in many ways critical of thp

” iffior' was P“‘ a e t h e r with p ^ r dips

fP?*? chewl”e with no guidelines, n,P criteria

spiec,lfic requirements, covering five different programs

This legislation now pending before us, I ask my colleague from

Michigan to carefully review it and he will find S we h a -

carefully written into law the kind o f e have

lines and standards which will preclude the recurrence o f f h '

criticism that was leveled at the first $75 million. 6

116 Cong. Rec. 42218 (December 17, 1970).

- 6a-

22

familiarity with the substance of the civil rights groups’

report.37 H.R. 19446 (as reported to the floor) responded

to these problems by requiring a civil rights assurance

covering assignment of faculty.38 Although, as noted, the

37 For example:

Mr. RYAN. . . .

In voting for the Emergency School Aid Act of 1970, therefore,

I do so cognizant that the Congress must exercise a stringent

oversight function to assure that its provisions are not mis

used, because the administration’s record is dismal. In fact, the

very program authorized by this bill has already been abused.

In August, $75 million was appropriated for the progenitor

of the program authorized by the bill before us today. By

virtue of this appropriation, $71.4 million has been distributed.

And an evaluation released on November 24 by the same groups

which published “The Status of School Desegregation in the

South, 1970” reveals the misuse of those funds.

Let me briefly run down the list of defects which the No

vember 24 report, entitled “The Emergency School Assistance

Program: An Evaluation,” detailed with regard to the ad

ministration of the emergency school assistance program, whose

promise the report describes as having “been broken.”

Second, making ESAP grants to districts engaged in these

discriminatory practices amounts to HEW’s acquiescence in

fraud perpetrated by local school officials. The ESAP regula

tions were carefully drafted to require that each applicant

guarantee that it would not engage in the practices prohibited

by those regulations—among them racial discrimination in the

hiring, firing, promotion, and demotion of staff; the racially

imbalanced assignment of staff within the school system; . . . .

116 Cong. Rec. 43143 (December 21, 1970). See also other com

ments in note 35 supra.

38 Applicants were required to sign an assurance that

staff members of the applicant who work directly with children,

and professional staff of such applicant who are employed on

the administrative level, will be hired, assigned, promoted, paid,

demoted, dismissed or otherwise treated without regard to

their membership in a minority group, except that no assign

ment pursuant to a court order, plan approved under title VI

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, or a plan determined to be

acceptable by the Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights

-7a-

23

bill passed the House of Representatives on December

21, it was never approved by the Senate. Accordingly,

new legislation was introduced, and new hearing's held

in the 92d Congress.

3. Spring, 1971

Ruby G. ̂Martin, a former Director of HEW’s Office

for Civil Rights and one of the report’s authors, testified

before both House and Senate subcommittees. In this

testimony, the major problems with ESAP were identified;

they included faculty segregation:

We found cases of segregation within schools, class

rooms and other facilities; cases of segregation and

discrimination in bus transportation; cases where

faculty and staff had not been desegregated in ac

cordance with applicable requirements; . . . ,39

As Marian Edelman, another Washington Research Proj

ect official, put it, the ESAP regulations were strongly

worded but they had not been enforced.40

These complaints were met with sympathy and concern

by figures who would play major roles in the enactment

of the new legislation. For example, during the hearings

following a notice of complaint pursuant to section 407(a) of

such Act will be considered as being in violation of this sub

section [.]

§ 8(a) (10), H.R. 19446, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. (1970)

116 Cong. Rec. 42225, 42226 (December 17, 1970).

reprinted at

39 Emergency School Aid Act: Hearings on H.R. 2266 Before

the General Subcommittee on Education of the House Comm, on

Education and Labor, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. 24 (1971) [emphasis

!o~?hcdj [ he êinafter cited as 1971 House Hearings^; see also

19:1 Senate Hearings at 121-70. And see, Washington Research

Ax? ^ Ct' et a " JHE E mergency School Assistance Program:

An Evaluation oO-ol (1970); Washington Research Project, et al.

( 1970)TATUS °F School DESEGREGA,noN in the South, 1970 97-100

40 1 971 Se7Ulte Hearings at 143; 1971 House Hearings at 36.

-8a-

24

Senator Mondale asked about the eligibility of a county

system in which three all-black schools had faculties 70%,

73% and 100% black while nine majority-white schools

had majority-white faculties.41 On the House side, Rep

resentative Pucinski made clear the subcommittee’s in

terest in writing into the legislation adequate safeguards

to prevent the violations listed in the report.42 Both sub

committees were also presented with another study on

ESAP, this one prepared by the General Accounting Of

fice, which criticized the lax administration of the pro

gram.43 While GAO studied only a small sample of ap

proved applications, it confirmed that districts in which

faculty assignments did not meet the standards of the

ESAP regulations nevertheless were granted assistance.44

In the spring of 1971, the Senate Committee reported

out (and the Senate passed) an ESAA proposal which

411971 Senate Hearings at 365.

421 might say to the committee that we are very privileged to

have before us two very distinguished spokesmen in the cause

of better education in this country. Mrs. Ruby Martin, who is

here as head of the Washington Research Project Action

Council. The Action Council has done substantial work in

evaluating the method in which the original $75 million was

spent by the administration in schools undergoing desegre

gation. . . .

It had been our hope when we put together the Emergency

School Aid Act of 1970 and worked it through this committee

that we could write into the legislation sufficient standards and

sufficient safeguards to assure against the very abuses and

shortcomings which the witnesses on this occasion and on

previous occasions have properly pointed out. . . .

1971 House Hearings at 17, 18.

43 General Accounting Office, Heed to Improve Policies and Pro

cedures for Approving Grants Under the Emergency School Assist

ance Program (1971), reprinted in 1971 House Hearings at 89-162;

see also, 1971 Senate Hearings at 171-74.

44 See 1971 House Hearings at 134; 1971 Senate Hearings at 174.

The Commissioner of Education promised better enforcement of

the regulations in districts “where serious faculty assignment

problems exist.” 1971 Senate Hearings at 229.

-9a-

25

combined features of several bills. S. 1557, 92d Cong.,

1st Sess. (1971), the “Emergency School Aid and Quality

Integrated Education Act of 1971,” had bipartisan sup

port led by Senators Mondale and Javits. It contained

the language of current clause (B) and also laid especial

stress on faculty integration. In order to qualify for

assistance under this proposal, a school system would

have been required to establish at least one “stable,

quality integrated school” with a faculty which was

representative” either of the community at large or of

the ̂ system’s total faculty if the system was seeking

to increase the proportion of minority group members

m its employ.45 According to the committee report, this

requirement was based on acceptance of testimony that

true integration and equality of educational opportunity

demanded “a climate of interracial acceptance” and con

ditions _ which were “far easier to achieve if tokenism

is not involved, if faculty as well as students are sub

stantially mixed . . . The bill’s primary sponsor,

Senator Mondale, specifically declared that eligibility con

ditions had been written into the legislation because of

the failure to enforce the ESAP regulations, the civil

rights groups’ study, and the GAO report. 117 Cong

Rec. 10759 (April 19, 1971). Its standards, he added!

went beyond the Fourteenth Amendment:

. . . And may I say that this measure is not limited

to what might be termed the minimum judicially

declared standards for desegregation under the 14th

amendment. We go beyond that. This is a measure

which bases its conclusions on what children need,

on what makes educational sense, and on what the

,, ^ No- 92’61> 92d ConE" 1st Sess. 12 (1971). Ultimately,

the Conference Committee which reconciled the House and Senate

versions of ESAA limited this requirement to applicants for “pilot

program” funds. See 38 Fed. Reg. 3451 (February 6, 1973). 48

48 S. Rep. No. 92-61, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. 13 (1971).

-10a-

26

country needs, whether the 14th amendment requires

it or not.

There may well be many school districts which have

desegregated in a minimum way under some court

order, which falls far short of the standard that we

think is necessary and that has been proven to be

necessary for good, stable, quality integrated edu

cation, and this proposal is designed to be of help

in that area. F

117 C o n g . R ec . 10762 (April 19,1971).47

Thus, although the bill did not define the term ‘‘dis

crimination which appeared at several places within it

(see Pet. Br. 27-29), there is ample indication that its

sponsors did not intend merely to replicate constitutional

standards.48 Rather, they desired to have HEW deny

47 See also, 117 Cong. Rec. 10764 (“This is an education bill. It

goes farther than the minimum constitutional requirement”), 10956

u™ Pr0ud ^ at Proposal is a creative proposal incorporating

all the hopeful strategies we have been aware of and it does not

stop with any legal remedies, but is bottomed on what is good for

the schoolchildren of this country").

48 This was the holding of Board of Educ. V. HEW. 396 F Sudo

203, 230-35 (S.D. Ohio 1975), rev'd in part on other grounds 532

F.2d 1070 (6th Cir. 1976), cited by Petitioners (Br a t^ 7 ) In

^ athews’ Civ- No- 3095-70 (D.D.C., Order of June' 14

1976) the district court held that an HEW determination of ineligi

bility for ESAA funding created only a “presumption of non-

compliance with Title VI” and directed HEW to proceed to inve«-

“ d eaf°rae Civil Rights Act in all such cases. Bradley

v. Milhken, 432 F. Supp. 885, 886-87 (E.D. Mich. 1977), also cited

by Petitioners, avoided a binding construction of the statute bv

leaving the matter to HEW. See also, Bradley v Milliken 460 T

S„pp 299, 317 (E.D. Mich. 1978, ("The problem S t S ’pr“ em

faculty distribution is that schools with a predominance of black

students also have a predominantly black faculty, while schools

which were traditionally white by student enrollment have a pre-

faculty”)- Robinson v. Vollert, 411 F. Supp. 461

(S.D. Tex 1976). discussed at Pet. Br. 42-43, involved a different

S a ! ° fvt§ 1J05(d).f l) and a wholly different question: whether

ESAA extends so far beyond the constitutional minimum as to

-11a-

27

funding to districts which did not carry out thorough

and effective desegregation plans without any of the

abuses that characterized the first year of the ESAP

program.49 This history distinguishes the ESAA legisla

tion from Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which

a majority of this Court in Regents v. Bakke, supra,

found was intended only to incorporate constitutional

standards of “discrimination.” See id., 57 L. Ed. 2d at

767-68 (opinion of Powell, J .), 795-800, 801-02 (opinion

of Brennan, White, Marshall and Blackmun, JJ .).

4. The Stennis Amendment

The Court of Appeals drew support for its interpreta

tion of § 1605(d) (1) (B) from the language of §1602

(a), which was originally added to S. 1557 by the

“Stennis amendment” on April 22, 1971,50 and which

was retained in all succeeding versions of the bill. See

584 F.2d at 588-89. Petitioners argue that the court be

low misconstrued the intent of the amendment as it re

lates to ESAA.51 They contend that the Stennis amend-

authorize HEW to conclude that a pupil assignment plan approved

under the Fourteenth Amendment by a federal district court was

nevertheless “discriminatory” under ESAA. The Robinson court’s

negative response to this question was heavily influenced by sepa

ration of powers concerns which simply do not arise in this case. See

411 F. Supp. at 472-77. Indeed, the Robinson court recognized that

§ 1605(d) did not merely incorporate constitutional standards but

“was aimed at specific forms of discrimination that may occur

even in perfectly proportioned systems.” Id. at 477.

49 S. 1557 was the lineal ancestor of ESAA. See S. Rep. No. 92-

604, 92d Cong., 2d Sess. 2 (1972).

50117 Cong. Rec. 11520 (1971).

51 The Stennis amendment applied (a) to Title VI of the 1964

Civil Rights Act and Section 182 of the Elementary and Secondary

Education Amendments of 1966; and (b) to ESAA. See Pet. Br.

at 33-34 (quoting language). The Conference Committee which

drafted the final ESAA wording in 1972 effectively split the amend-

-12a-

2S

ment was designed only as precatory language, simnly

descriptive of the

policy that ESAA funding is available to all segre

gated school systems attempting (voluntarily or

otherwise) to desegregate, notwithstanding whether

their segregated conditions were caused by officia1

or non-official factors.

Pet. Br. at 33. On its face, this is a remarkable con

struction of legislative language which states the national

policy to be that all “guidelines and criteria established

pursuant to this chapter” shall be applied uniformly “in

dealing with conditions of segregation by race in the

schools . . . without regard to the origin or cause of such

segregation.” ̂ It would have been totally unnecessary to

amend the bill for this purpose. Section 5 (a )(1 )(A )

of the bill already made districts eligible whether they

planned to “desegregate” or to “reduce racial imbal

ance.” 52 Even without the Stennis amendment, Senator

Mondale said, “ [t]he legislation before us today estab

lishes a nationwide Federal standard for the elimination

of racial isolation and for the establishment of integrated

schools wherever such isolation exists.” 117 Co n g . R e c .

10760 (April 19, 1971). See also, id. at 10953 (April 20*

1971) (Sen. Javits). P ’

Moreover, Petitioners’ construction of § 1602(a) so

enervates the provision as to make a rational observer

wonder why Senator Stennis sought to have it included

in the law at ail. A more informed consideration of the

legislative history than is given by Petitioners demon

strates the soundness of the Court of Appeals’ reading.

ment s provisions into two distinct sections without anv substantive

modification. See Pet. Br. at 34 n.*. Only the effect of the proviso

on ESAA is at issue here.

92d. Cong" lst Sess- (1971). reprinted at 117 Cong.

Rec. 1 .̂020 (.April 26, 1971). See also, S. Rep. No. 92-61, 92d Cone

ls t Sess. 2, 6. 35-37 (1971).

-13a-

29

For several years, Senator Stennis had sought not

merely to “encourage” (Pet. Br. at 36) federal officials

to attack northern, so-called de facto segregation, but to

require them to do so. For example, at his initiative,

language similar to that of § 1602(b)53 was included in

the Senate bill which became P.L. 91-230.54 However,

the Conference Committee on the latter bill amended the

provision by adding an explanation that it required uni

form national application of one policy with respect to

“de jure” segregation and uniform national application

of another policy with respect to “de facto” segregation.55

This was not what Senator Stennis had in mind, as he

sought to make clear in the amendment he proposed to

S. 1557.

Insofar as that amendment covered Title VI and Sec

tion 182 (see note 50 supra), Senator Stennis wished to

mandate enforcement, and it was this portion of his

amendment (and only this portion) which the sponsors of

S. 1557 opposed. Senator Mondale feared that

[ajlthough it can be read to ask for a uniform policy

against discrimination in public education—a policy

I vigorously support—many will read the amend

ment to excuse enforcement of title VI against offi

cial discrimination, North and South alike, until

such time as the courts declare purely adventitious

segregation unconstitutional. This would be a tragic

result.56

53 Senator Stennis’ amendment to S. 1557 was “identical to the

amendment passed by the Senate last year, with the addition of

three words which make it apply to this bill.” 117 Cong. Rec. 11508

(April 22, 1971). See text at note 54 infra,.

54 84 Stat. 121, reprinted, in [1970] U.S. Code Cong. & Adm.

N ews 133.

55 See id., §2, [1970] U.S. Code Cong. & Adm. N ews 134, 2939.

56 117 Cong. Rec. 10760 (April 19, 1971). See also, id. at 10764

(Sen. Mondale); id. at 11516 (Sen. Javits) (April 22, 1971). It was

-14a-

30

This was hardly idle speculation, as illustrated by a

b e fo T - B^eew l f f at0r%RibiCOfr and Allen a f™ days

Tiri. trr hatever the t™ or feared impact on

I, application of the Stennis amendment to ESAA

was straightforward. Senator Stennis warned to be s ^

gate nu°ndtrrthe1StriCtS w.T !.actuaI|y squired to desegre- gate, under the same guidelines and criteria as southern

districts, m order to receive funds.1' This application of

the amendment to the ESAA program was a“ b,e to

m eit^thTfsTnTtor^f ^ amendment’s effect on Title VI enforce-

in Pet Br at 36 W“ respondin* in * * statements quoted

Senator Ribicoff was seeking to amenH <5 ikkv jj

requiring nationwide planning and implementation ofw proVls'ons

™ b“ iS within a

percent balance. year ^ lod to reach a 50-

117 Cong. Rec. 10945 (April 20, 1971).

arL S“ S t b ? S ^ hif,,cS rathto„e”1, ,he ESAP p-

to the second Supplemental Appropr J ™ , S 5 T & “ £ £ % £

£ said defi-

£ £ e * a t l hether they - t o ^ „ t n h2 " s = 2

S never'said S a t he wM ^ e ^ S f ^ President

be “ - v r r s j s x

116 Cong. Rec. 20809 (June 22 197m Tn iq- i o

supported the Stennis amendment h 1 19/1’ Senator Eastland

standards would be applied fa irly to north ° aSSUf thai eligibility

districts by HEW emPp U s ^ J ^ r ^ di S ; ? h “

-15a-

31

its sponsors,30 as Petitioners recognize (Pet. Br. at 39-

40). Their contention that it was intended only to clarify

that “de facto” districts could apply for funds under

ESAA, however, is supported by neither the language nor

the history of the S tennis provision.

5. Fall, 1971

The House of Representatives failed to act upon an

ESAA bill in time for the 1971-72 school year. Anticipat

ing the extension of ESAP, HEW during the summer

promulgated revised regulations which relaxed the re

quirement of individual school assignments reflecting

“substantially the same ratio that exists in . . . the sys

tem as a whole” 60 to cover only full-time faculty mem

bers.61 Through continuing resolutions, and over some

objections from the sponsors of S. 1557, ESAP was ex

tended until October, 1971;62 however, because no new

authorizing legislation was enacted, Congress appropri

ated no additional funds for the program during Fiscal

Year 1972.63

50 In addition to the Javits statement quoted in Pet. Br. at 39,

see 117 Cong. Rec. 11517 (Sen. Javits) (April 22, 1971):

. . . if this kind of approach were confined to this bill, I would

see a great deal of merit in it. That is what we purport to do

with this bill. We want this money used to combat all types of

segregation, whether de facto— racial isolation—or de jure.

60 See 45 C.F.R. § 181.6(a) (4) (vi) (1971), note 32 supra.

81 36 Fed. Reg. 12984 (July 7, 1971) [proposed]; 36 Fed. Reg.

16546 (August 21, 1971) [final], reprinted at 45 C.F.R. Part 181

(1972).

82 H.R.J. Res. 742, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. (1971), P.L. 92-38, 85

Stat. 89, reprinted in [1971] U.S. Code Cong. & Adm. N ews 98-

H.R.J. Res. 829, 92d Cong.. 1st Sess. (1971), P.L. 92-71, 85 Stat’

182. reprinted in [1971] U.S. Code Cong. & Adm . News 198. See

117 Cong. Rec. 22703-04 (Sen. Mondale), 22704-08 (Sen. Javits)

(June 29. 1971) ; id. at 30430 (Sen. Javits) (August 6, 1971).

See Office of Education and Related Agencies Appropriations

Act, 1972,” H.R. 7016, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. (1971), P.L. 92-48, 85

-16a-

32

reportedT ^ nf 1912 ’ 3 n6W ESAA bil1 was favorably

Uves -* £ L l C°mmitt/ ! , t0 1116 House of Eapresenta- lives As in the case of the 1970 House bill, H R *266

included specific eligibility conditions, this time' in “lan

guage identical to that of S. 1557.65 On the same dav

Representative Pucinski sought to have the House con-

d- th* ™ fter under a suspension of the rules.00 Most

°f the debate now concerned the question whether the

anti-busing provisions of the bill were acceptable The

motion to suspend the rules failed.” P ble’ The

!ater’ Ŵ le the House was debating H.R. <248 (a bill to reauthorize the Higher Education Act)

Representative Pucmski announced that he would offer

the substance of H.R. 2266 as a floor amendment to that

tegslation.'’ He did so on the following day09 and after

additional debate about the anti-busing provisions t t h

e amendment,0 and the bill were passed.71 The text

1 NEws l l 5 =

10 , 1971) [Senate]; id. at 23033 (JunL SO ^ign) V conf218

a REP- N a 92-145’ 92d C o i* . L t s i 7 ( W71 ‘‘w t *mental Appropriations Act, 1972,” H.R. 11955 q<M ’ i ^

Cong. 4 ADU9n ! S 7 0 S S U t ~ 627, " v H n t e d “ [19713 u l Cote

as'h ^ p a^ seT lh eeHousenjn^December lV“ ^ “ “ b‘“

117 CONG. Rec. 38483 (November 1 , 19 71).° PP‘ ‘' ° '23 SMpra)-

05 § 5 (d )(1 ), H.R. 2226, 92d Cong., 1st Sess n q 7i i

117 CoNG- Rec. 38480 (November 1 19 7 1) T hl^ h repnnted at

W i “ 7„ ~ s x s z *

S“ r s in 1972 h0~ ppU3S 1X :117 Cong. Rec. 38479 (November 1 , 19 71)

07 Id. at 38493.

08 Id. at 39068 (November 3 ,19 71).

m Id. at 39323 (November 4, 19 71)

70 Id. at 39339.

71 Id,, at 39354.

-17a-

33

of H.R. 7248, including ESAA, was then substituted as

a House amendment for the text of a Senate-passed

higher education reauthorization measure, S. 659 72 and

that bill was returned to the Senate.73

6. Winter and Spring, 1972

On February 22, 1972, S. 659, as amended by the

House, reached the Senate floor for the first time. On

behalf of the Committee on Labor and Public Welfare,

Senator Pell moved that the Senate concur in the House

amendment to S. 659 with a substitute of its own.74

This substitute included ESAA, together with the con

ditions of eligibility which had been included in both S.

1557 and H.R. 2266 in the previous session. During the

debates, many anti-busing amendments were offered and

considered. In addition, two proposed amendments to

ESAA, including one to the eligibility conditions, are rele

vant to the matters in dispute.

On February 29, 1972, Senator Chiles introduced an

amendment to what became clause (A) of § 1605(d) (1),

concerning transfer of property to private schools.75 The

amendment added the words “which it knew or reason

ably should have known to be,” in order to insure that a

school system which transferred property without knowl

edge that the recipient was a segregated private school

would not be penalized. Senator Chiles explained:

[I] t would provide that it has to be knowingly made

or made with some kind of intent, because that was

the purpose of Congress originally. I think this

72 Id. at 39374.

73 Thus, the 1971 House bill (H.R. 2266) became, successively, a

part of H.R. 7248 and then S. 659, under which number it was

ultimately enacted.

74 118 Cong. Rec. 4974 (February 22, 1972).

78 Id. at 5982 (February 29, 1972).

-18a-

34

would take care of instances where the school board

is doing a valuable job in trying to accomplish de

segregation but because they sell some property at

public auction or through clerical assistance a sale

is inadvertently made by the school district, they

find they are in danger of losing all funds and have

to pay back funds under the program. That is not

what Congress intended.78

The Chiles amendment was prompted by the experience

of Broward County, Florida under the ESAP program.

See 118 Cong . Rec. 5982-84 (February 29, 1972). In

Senator Chiles’ view, the district had been ruled in

eligible for ESAP because of an inadvertent transfer

of property to a private school pursuant to language in

the appropriation bill which did not include an explicit

requirement of intent77 (even though, in the Senator’s

opinion, that is what Congress had meant). To avoid a

repetition of the problem, Senator Chiles proposed to

amend clause lA) to state such a requirement in the

legislation. This was acceptable to the bill’s sponsors78

and the amendment was adopted.79

Significantly, Broward County had also been ruled in

eligible because of imbalanced faculty assignments,80 but

Senator Chiles proposed no similar amendment to clause

78 Id. at 5983.

77 The language of P.L. 91-380, 84 Stat. 800, reprinted at [1970]

U.S. Code Cong. & Adm. N ews 944-45 w as:

Provided further, That no part of the funds contained herein

shall be used (a) to assist a local educational agency which

engages, or has unlawfully engaged, in the gift, lease or sale of

real or personal property or services to a nonpublic elementary

or secondary ̂ school or school system practicing discrimination

on the basis of race, color, or national origin; . . . .

78 118 Cong. Rec. 5982 (February 29, 1972).

79 Id. at 5992.

89 Id. at 5983.

-19a-

35

(Bi even though he suggested that the situation result

ing in ineligibility had occurred because of practical,

nonracial circumstances similar to those described by Pe

titioners in this case.81

The second suggested amendment which is relevant to

this case was also proposed by Senator Chiles. It would

clearly have established that only constitutional standards

were to apply to at least some classes of applicants by

providing that school districts subject to court orders

would be exempt from any additional eligibility determi

nations by HEW.82 Senator Mondale opposed the amend

ment on the ground that it would, for example, permit

transfers to segregated private schools83 or, in other

words, eliminate the statutory conditions of eligibility.

Senator Javits summarized the issue as follows:

The precise issue is: The Senator from Florida says

that when we have a court order, whatever the

court order says, we do, and then we qualify for the

money.

The Senator from Minnesota (Mr. MONDALE), the

Senator from Rhode Island (Mr. PELL) and I say

that, in addition to complying with the court order,

we have got to comply also with some of the ele

mentary precautions, to prevent the trimming of the

desegregation process which may be outside the ju

risdiction of the court in that case. That is the real

issue. We ran into the situation where property was

being transferred to freedom academies, and so forth,

so we took the precaution of giving the right to ad

minister what will be done with the money to the

governmental department in charge, rather than

8! I d . at 5984.

82 I d . at 6269 (March 1, 1972).

ss I d . at 6270.

-20a-

36

automatically saying that if we comply with a court

order we get the money.84

S?® Chjles ‘f le»dment was defeated.85 The Senate sub

stitute for the House amendment of S. 659 was then

noSmdt 6 aiid T t0 a Conference Committee, which made

no material changes m the conditions of eligibility. The

Conference Committee’s report was passed 8T and became

P.L. 9--318 (Education Amendments of 1972) 86 Stat

tT vtt i7! [ 1972] U -S- C0DE C0NG- & N ews 278. Title VII of that act is ESAA.

7. The Pucinski-Esch Colloquy

The critical legislative history upon which Petitioners

^ 5 f exchange between Representatives

Pucinski and Esch on the House floor when Pucinski

introduced the contents of H.R. 2266 as an amendment

to the higher education bill (see p. 32 supra) The ex

change is set out in Pet. Br. at 30-31. There is no doubt

that it conveys Rep. Pucinski’s view that ESAA would

not authorize use of the Singleton rule as an eligibility

requirement. We submit, however, that this “isolated