Weber v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corporation and United Steelworkers of America, AFL-CIO Supplemental Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

April 27, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Weber v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corporation and United Steelworkers of America, AFL-CIO Supplemental Brief Amici Curiae, 1977. 8fc13ad4-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0dcc5e19-4b06-4cc1-bfec-0b39235e9b14/weber-v-kaiser-aluminum-chemical-corporation-and-united-steelworkers-of-america-afl-cio-supplemental-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

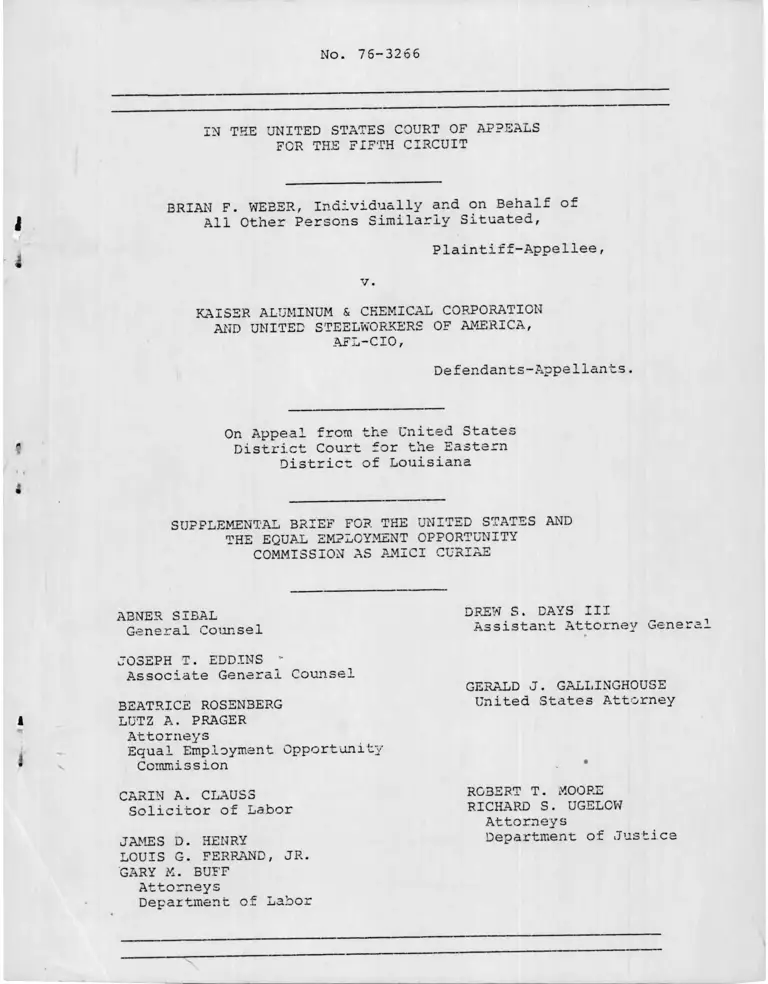

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIAN F. WEBER, Individually and on Behalf of

All Other Persons Similarly Situated,

KAISER ALUMINUM & CHEMICAL CORPORATION

AND UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA,

On Appeal from the United States

District Court for the Eastern

District of Louisiana

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AND

THE EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY

COMMISSION AS AMICI CURIAE

Plaintiff-Appellee

AFL-CIO

Defendants-Appellants.

ABNER SIBAL General Counsel

DREW S. DAYS III Assistant Attorney Gene

JOSEPH T. EDDINS “ Associate General Counsel GERALD J. GALLINGHOUSE

United States AttorneyBEATRICE ROSENBERG

LUTZ A. PRAGER

AttorneysEqual Employment Opportunity

Commission

CARIN A. CLAUSE

Solicitor of Labor

ROBERT T. MOORE

JAMES D. HENRY

LOUIS G. FERRAND, JR.

GARY M. BUFF

RICHARD S. UGELCW

Attorneys

Department of Justice

Attorneys

Department of Labor

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 76-3266

BRIAN F. WEBER, Individually and on Behalf of

All Other Persons Similarly Situated,

Plaintiff-Appellee,

v.

KAISER ALUMINUM & CHEMICAL CORPORATION

AND UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA,

AFL-CIO,

Defendants-Appellants.

On Appeal from the United States

District Court for the Eastern

District of Louisiana

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AND

THE EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY

COMMISSION AS AMICI CURIAE

INTRODUCTION

At the oral argument in this cause, held on March 28,

1977, the Court invited further discussion by briefs of the

relevance of United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh, Inc.

v. Carey, 45 U.S.L.W. 4221 (March 1, 1971), to the issues raised

herein. This supplemental brief is filed on behalf of the

United States and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in

response to that invitation. We would also like to take this

1977), and the recent decision of the Court of Appeals for the

Third Circuit in E. E.0.C. v. American Telephone & Telegraph,

Co., et al., No. 76-2217, No. 76-2281, No. 76-2285 (April 22,

1977) which we believe to be relevant.

DISCUSSION

In United Jewish Organizations, the Supreme Court sustained

the constitutionality of a race conscious reapportionment plan

enacted by the New York State Legislature in order to render cer

tain legislative districts of the State acceptable to the Attorney

General of the United States under Section 5 of the Voting Rights

Act, of 1965, as amended, 42 U.S.C. §1973.

One of the geographic areas affected by this reapportionment

was the Williamsburgh section of Brooklyn (Kings County, New York),

in which a community of some 30,000 Hasidic Jews resided. Prior

to reapportionment, the entire Hasidic community was situated

in one assembly and one senate district. To achieve a nonwhite

population goal of 65% in certain districts, the reapportion

ment plan divided the Hasidic community by placing a portion

_ vof it into each of two assembly and two senate districts. The

plaintiffs challenged the redistricting on the grounds that it

opportunity to bring to the Court's attention the Supreme Court

decision in Califano v. Webster, 45 U.S.L.W. 3630 (March 21,

1/ 65% was the non-white population figure which the Attorney

General indicated would bring the legislative districting of

Kings County into compliance with the Voting Rights Act.

2

diluted the value of their vote for the sole purpose of achiev

ing a racial quota, which it was alleged, violated the Fourteenth

Amendment. The Supreme Court rejected this challenge.

There are important similarities between United Jewish

Organizations and the instant case. Each involves the volun

tary action by a defendant to comply with efforts of the

executive branch to remedy the present effects of discrimi

nation by implementing race conscious affirmative relief.

In United Jewish Organizations, the Court noted that the appli

cation of Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act was not dependent

upon proof of past discrimination by the state. 45 U.S.L.W.

at 4225-26.

Moreover, in both United Jewish Organizations and the pre

sent case, the affirmative remedy adopted included a specific

numerical goal which was representative of the population

characteristics of the relevant community. Finally, as the

Supreme Court noted, the use of numerical goals to achieve

specific objectives in the context of the Voting Rights Act

has been ratified by the Congress and sanctioned by the

courts. 45 U.S.L.W. at 4225. Likewise, the use of numerical

goals as an important element of affirmative actions plans

under Executive Order 11246, as amended, has also been rati

fied by the Congress and sanctioned by the courts (see pages

19-30 of our principal brief).

3

The Supreme Court in Califano v. Webster, supra, recently-

sustained a statute which granted females reaching age 62 prior

to 1972 an economic advantage over males in the computation of

social security entitlements. The Supreme Court referred to

the historic job discrimination which put women at an economic

disadvantage and held that the Congress may, as it did, enact

remedial legislation to compensate women for economic disabili

ties suffered by them as a result of that societal discrimination.

As we have emphasized in our principal brief, we believe

that the United States has a compelling interest in redressing

historic job discrimination by the use of remedial programs.

The Congressional use of social secuirity benefits to compen

sate "... women for past economic discrimination" is but one

example. 45 U.S.L.W. at 3630. The remedial policies embodied

in Executive Order 11246 and other employment discrimination

programs serve the equally important government objective of

remedying the effects of society's disparate treatment of

minorities and females.

Lastly, we attach for the Court's consideration the

slip opinion in E.E.O.C. v. American Telephone & Telegraph,

Co., et al., supra. We believe that this decision is rele

vant to the discussion in our principal brief regarding the

4

differences between relief under Title VII and affirmative

action under the Executive Order program (see slip op. pp.

15-16).

ABNER SIBAL

General Counsel

JOSEPH T. EDDINS

Associate General Counsel

BEATRICE ROSENBERG

LUTZ A. PRAGER

Attorneys

Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission

CARIN A. CLAUSS

Solicitor of Labor

JAMES D. HENRY

LOUIS G. FERRAND, JR.

GARY M. BUFF

Attorneys

Department of Labor

DREW S. DAYS III

Assistant Attorney General

GERALD J. GALLINGHOUSE

United States Attorney

RICHARD S. UGELOW

Attorneys

Department of Justice

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I, Robert T. Moore, hereby certify that a copy of the

the foregoing Supplemental Brief of the United States and

the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission was on this 27th

day of April, 1977, mailed, first class, postage prepaid,

to the following counsel of record:

Michael Gottesman, Esquire Bredhoff, Cushman, Gottesman

& Cohen

1000 Connecticut Avenue, N.W.

Washington, DC 20036

Robert J. Allen, Jr., Esquire

Legal Department

Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical

Corporation

300 Lakeside DRive Oakland, CA 94612

Cloyd R. Mellott, Esquire

Eckert, Seamans, Cherin &

Mellot

600 Grant Street

Pittsburgh, PA 15219

Burt A. Braverman, Esquire

Cole, Zylstra & Raywid

2011 Eye Street, N.W.

Washington, DC 20006

John W. Finley, Jr., Esquire

Brashich and Finley

501 Madison Avenue

New York, NY 10022

Arnold Forster, Esquire

315 Lexington Avenue

New York, NY 10016

Michael R. Fontham, Esquire Stone, Pigman, Walther,

Whittmann & Hutchinson

1000 Whitney Bank Building

New Orleans, LA 70130

Frank W. Middleton, Jr., Esquire

Taylor, Porter, Brooks & Phillips P.O. Box 2471

Baton Rouge, LA 70821

Jerome A. Cooper, Esquire

Cooper, Mitch & Crawford

409 North 21st Street

Birmingham, AL 35203

Joseph P. Fischer, Esquire

Law Department

ALCOA Building

Pittsburgh, PA 15219

Austin Graff, Esquire

6601 West Broad Street

Richmond, VA 23261

Gene E. Voigts, Esquire

Shook, Hardy & Bacon

Mercantile Tower Building

1101 Walnut Street

Kansas City, MO 64106

ROBERT T. MOORE

Attorney

U.S. Department of Justice

Washington, DC 20530

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

NOS. 76-2217, 76-2231 and 76-2285

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION, JAMES D. HODGSON,

Secretary of Labor, United States Department of Labor and

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

vs.

AMERICAN TELEPHONE AND TELEGRAPH COMPANY, NEW ENGLAND

TELEPHONE AND TELEGRAPH COMPANY, THE SOUTHERN NEW ENGLAND

TELEPHONE COMPANY, NEW YORK TELEPHONE COMPANY, NEW JERSEY

BELL TELEPHONE COMPANY, THE BELL TELEPHONE COMPANY OF

PENNSYLVANIA AND THE DIAMOND STATE TELEPHONE COMPANY,

THE* 0-ESAPEAKE AND POTOMAC TELEPHONE COMPANY, THE

CHESAPEAKE AND POTOMAC TELEPHONE COMPANY OF MARYLAND,

THE CHESAPEAKE AND POTOMAC TELEPHONE COMPANY OF VIRGINIA,POTOMAC TELEPHONE COMPANY OF WESl

BELL TELEPHONE AND TELEGRAPH COMPANY,

TELEPHONE’COMPANY, THE OHIO BELL

'ATI BELL INC., MICHIGAN BELL •BELL

COMPANY CINCINNa.

THE CHESAPEAKE AND

VT.RGINIA, SOUTHERN

SOUTH CENTRAL

TELEPHONE COMPANY, INDIANA BE CL TELEPHONE COMPANY^,

INCORPORATED WISCONSIN TELEPHONE COMPANY, ILLINOIS

BELL TELEPHONE COMPANY, NORTHWESTERN BELL TELEPHONE

COMPANY, SOUTHWESTERN BELL TELEPHONE COMPANY, THE

MOUNTAIN STATES TELEPHONE AND TELEGRAPH COMPANY,

PACIFIC NORTHWEST BELL TELEPHONE COMPANY, THE PACIFIC

TELEPHONE AND TELEGRAPH COMPANY AND B^LL rELEPHONii

COMPANY OF NEVADA

COMMUNICATIONS WORKERS OF AMERICA AFL-CIO (CWA)

(intervening defts.)

TELEPHONE COORDINATING COUNCIL TCC-1 (national^Bell

Council), IBEW ("IBEW"Council) and THE ALLIANCE OF

INDEPENDENT TELEPHONE UNIONS - intervening defts.

COMMUNICATIONS WORKERS OF AMERICA,

Appellant in No. 76-2217

THE TELEPHONE COORDINATING COUNCIL, TCC-1,

IBEW - Appellant in No. 76-2281

ALLIANCE OF INDEPENDENT TELEPHONE UNIONS,

Appellant in No. 76-2285

Of Counsel:

JAMES A. DeBOIS

AMERICAN TELEPHONE L

TELEGRAPH COMPANY

195 Broadway

New York, New York j.0036

BERNARD G. SEGAL

BARRY SIMON

SCHNADER, HARRISON, SEGAL

6c LOUTb

1719 Packard. Building

Philadelphia, Pa. 19102

Of Counsel:

CHARLES V. KOONS

MATTHEW A. KANE

KANE 6c KOONS

1100 - 17th St. N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

THOMPSON POWERS

JANE MeGREW

MORGAN D. HODGSON

SYEPTOE 6c JOHNSON

1250 Connecticut Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

Attorneys for American Telephone

6c Telegraph Company, et al.

RICHARD H. MARKONJ.TZ

MIRIAM L. GAFNI

MARKOWITZ ; 6c KIRSCHNER

1500 Walnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 19106

Attorneys for Communications

Workers of America

ELI HU I. LEI FEE.

SHERMAN, DUNN, COHEN 6c LEiFER

1125 Fifteenth Street, N.W.

Suite 801

Washington, D.C. 20005

LOUIS H. WILDERMAN

MERANZE, KATZ, SPEAR & WILDERMAN

21st Floor, Lewis Tower Building

15th and Locust

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19102

Attorneys for IBEW Council

ABRAHAM WEINER

^AUL M . LEVINS ON

MAYER, WEINER <S LEVINSON

19 West 44th Street

Nev7 York, New York 10036

Attorneys for Allrance oj-

Independent Telephone Unions

4

GIBBONS, Circuit Judge

This is an appeal by three labor unions: the Communica-

cions Workers of America (CWA), the Telephone Coordinating Council

TCC-1, International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (I3EW),

and the Alliance of Independent Telephone Unions (Alliance)

(hereinafter referred to collectively as the intervening

defendants). The order below denied their motions to modity

a consent decree, dismissed the motion of CWA for a preliminary

injunction against continued implementation of an affirmative

action override provided for by Che decree, and granted the

motion of the plaintiffs and the original defendants for the

entry of a supplemental injunctive order. The plaintiffs are the

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), the Secretary ot

labor, and the United States. Their complaint, filed on January

18, 1973, charged violations of the Fair Labor Standards Act,

of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act or 1964, and of Executive

Order 11246. The defendant is the American Telepp.one and

Telegraph Company (AT&T) , appearing-' for itself and on behalf

of its associated telephone companies in the Bell System. On

the same day that the complaint was fried AT&T answered, deny u p

the violations alleged. However, it simultaneously approved and

1

consented to a decree which embodied and was designed to

enforce a negotiated agreement under which AT&T undertook to

implement a model affirmative action program. That program .

was designed to overcome the effects of past employment dis

crimination in the Bell System with respect to women, blacks,

and other minorities. The intervening defendants contend that

the consent decree, as originally agreed to and as supplemented,

conflicts with provisions of collective bargaining agreements

, f-spn and AT&T and otherwise unlawfully invades rightsbetween Lnem ana eicc-L, ^

c- r onoetitive seniority in transferof their members respecting competi.iv

1

and promotion. hTe aa.firm.

I. The Consent Decree

in November 1970, AT&T filed with the Federal Communica

tions Commission (FCC) a proposed tariff which would increase

interstate telephone rates. Before that filing was acted on,

t The decision a p p e a l e d ^

Opportunity Commission . 1 * prior history of this pro-

419 F.Supp. 1022 (E.D.Pa. 1976). ? Employment Opportunitytreated litigation may be gl*aned ^omjCquaL 506 F .2d 735

Commission v. American Telephon^ & J in part 356 F.Supp.

(3d Cir. 1974) affirmin&j£^a£ — T ^ T ^ Z ^ n l z e d that CWA would

1105 (E.D. Pa. 1973). In that case we ^ â rotect its existing

have standing to intervene as a dei^ eafter CWA, IBEW and Alliance

collective bargaining agreement . . e e as defendants formoved for and were granted leave to ^terven

the purpose of seeking modification of the consent

- 2 -

H-v. -CC-» W>T *> M1 ' i .r-̂L.1 ' l-' ̂ wv • - - - —— ->• ~-- • - - •' *..

... ___ ‘4 . . y . . t /.V -t r: *v * '* » * * • >

EEOC filed with the FCC a petition requesting that the increase

be denied because AT&T's operating companies were engaged in

systemwide discrimination against women and minorities. The

FCC initiated a special proceeding to consider the charges,

holding 60 days of hearings in 1971 and 1972. A number of

organizations intervened in support of the EEOC. While the

hearings progressed, settlement negotiations took place between

AT&T and the government parties, w m c n eventually led

termination of the FCC special proceeding and the entry of the

Consent Decree. Although the Alliance of Independent Telephone

Unions did not participate in negotiating the Consent Decree, tea

A rvTA invited to do so but remainedIBEW did participate, and CWA was rnvitec uo

deliberately aloof. 365 F.Supp. at 1108, 1109.

The Bell System is one of the largest employers in the

United States. Traditionally, its operating companies have

been organized along departmental lines. The plant department

has been responsible for installation'and maintenance of physical

facilities such as central office equipment, transmission lines,

and subscriber telephones. The traffic department has been

responsible for putting calls through, operator assistance,

information, and related services. The commercial department

has handled subscriber sales and Dilling. The accou

department has performed the bookkeeping and accounting runctions

3

Until at least the late 1960's, Bell System hiring practices

generally followed departmental lines. The plant department,

in which craft jobs predominated, was traditionally a male

preserve, while female employees were generally employed as

operators, bookkeepers, or in other clerical occupations in

the traffic and commercial departments. Pay scales at both

entry and higher levels in the plant department were, and

remain,higher than for employees with comparable length of

service in the other departments. Transfers from the traffic

or commercial departments were possible, but there was a general

policy of slotting a transferred employee in at the next higher

pay rate than that last enjoyed in the previous position.

Since traffic and commercial employees had lower starting

rates and lower rates at each step of the wage progression

schedule, that policy resulted in a transferee to the plant-

department receiving a lower rate of pay than would an employee

performing the same job who had been hired on the same date,

but who had started in the plant department. These hiring

practices resulted in a concentration of males and females m

certain classifications. Moreover there was an imbalance

between the racial and ethnic composition of the work forces,

of many operating companies and the racial ^nd e<_hnic makeup

4

their available labor markers. The intervening defendants

do not dispute that past patterns and practices were dis

criminatory, nor do they dispute that the present work force

in many Bell System departments still reflects those past

patterns and practices.

The Consent Decree directs the Bell System Companies

to establish goals and intermediate targets to promote the

full utilization of all race, sex, and ethnic groups in

each of fifteen job classifications. The intermediate targets,

set annually, reflect the representation of such groups in the

external labor market in relevant pools for each operating

company’s work force. The intermediate targets are the

major prospective remedies in the Consent Decree. When any

Bell Company is unable to achieve or maintain its intermediate

target,-applying normal selection standards, it is required by

the decree to depart from those standards in selecting candidates

for promotional opportunities. Ityeust then pass over candidates

with greater seniority or better qualifications in favor of

members of the underrepresented group who are at least ’"oasically

. - ffiVmflrive action override, the greater qualified.” Without tars afrrrmatrv

time in title of incumbent members of the over-represented race,

sex, or ethnic group would inevitably reduce the opportunity

for advancement of the under-represented groups and would perpetuat

5

the effects of the former discrimination. The' affirmative action

override applies, however, only to minority promotional oppor

tunity. A promotion under the override does not result in any

increase in competitive seniority for purposes of layoff or

rehire, as to which the collective bargaining agreements

control.2 The life of the decree is sin; years, ending on

January 17, 1979. It provides that AT&T may bargain collectively

with collective bargaining representatives for alternative pro

visions which would also comply with federal law. No such

alternative provisions have been presented to. the district court.

II. The Supplemental Order .

In an interim report on compliance with the Consent

Decree it appeared that in a number of specific categories

the Bell Companies fell short of attaining intermediate targets

promulgated for 1973. The government plaintiffs and AT&T jointly

moved for the entry of a supplemental order aimed .at remedying

2 The consent decree, Part A § 1II-C ter_Met credited service shall be used ior deter

to in in®6 layoff and related force adjustments and

recall to jobs where nonmanagement female and

minority employees would otherwise be laid orf,

Effected or not recalled. Collective bargaining

agreements or Bell Company practices snail govern

the confines of the group of employees being

sidered. Provided, however, vacancies created

bv layoff and related torce adjustments shall

not be considered vacancies for purpose

fer and promotion under thrs Section.

6

thase deficiencies and assuring future achievement of

targets and goals. The supplemental order provides that

unmet targets' shall be carried forward in certain establish

ments and job classifications. For a two month period ending

on October 24, 1976 some Bell Companies were required to make

all placements in affected job classifications from groups

as to which their targets had not been met. The supplemental

order also provides for the creation or a Bell System Affirma

tive Action Fund and its expenditure on projects which will

advance the objects of the decree. It also articulates tne

understanding of the parties that while the original Consent

Decree was not intended to supplant the collective bar

gaining agreements, to the extent that any provisions of the

latter would prevent the achievement of the affirmative action

targets and goals, the decree controlled. The^carry-forward

provisions of the supplemental order do hot enlarge the Bell

companies' total affirmative action obligations under the

Consent Decree, nor do they extend its life.

III. Bell System Promotional Seniority

Since the only alleged conflict between the collective

bargaining agreements and the Consent Decree and supplemental

order relates to promotional seniority, our sta-trn0

r , ^aoinpd-for promotional practices point is a description of bargained for P _______________

The contracts between AT&T and each of the intervening defendants

are not identical. As to each intervening defendant there are

also variations, in contracts v i * specific operating com

panies, negotiated locally to reflect local conditions and

practices. However, a common feature of all tne agreements is

that seniority for all purposes is determined by "net credited

service" in any department in the Bell System. It is also com

mon to provide that in selecting employees for promotion, other

factors being equal, the Company will promote the employee with

the greatest net credited service. However, it is clear that

the company has not bargained to the union any role in the

determination of employee qualifications. Soma ag cent

to "the employee whom Company rinds is best qualified,

speak of "ability, aptitude, attendance, physical fitness

the job, and proximity to the assignment." Some agreements even

qualify the seniority-equal qualification language by language

to the effect that "[Nothing in this paragraph shall be con

strued to prevent Company from promoting employees for unusually

meritorious service or exceptional ability. nlmough their

approach to the alleged conflict between the Consent Decree and

8

i *

their collective bargaining agreements is not identical the

intervening defendants agree -that the bargained-for promotional

system is a merit selection system. Management determines the

employee best qualified in its judgment, but seniority decides

the issue where two employees are considered by management to

, Th^ effect or the affirmative action be equally qualified. ihe ei^ecc

« . . . « . « - - ■ “ < r ° " a

«... “ “ ‘

under pre-decree practice. The decree provides for selecting,

f nprqonS those who in the judgment from the under-utilized group of persons,

. . r- j »' Although the briefs of the<- ''basically qualified. AiUlUU5of management are oasicao-^y h

„ ..V,- issue of competitive seniority, tb intervening defendants stress the xssu

.. T tjM ch under the contracts woulc roal dispute is less over seniority, which

• eases of equal qualification, as overo-ily be determinative in cases

. Rifled" oriterioh. The continued the departure from the "best qualified

operation of that criterion would,^of course, significantly

confine promotions within departmental lines, as ha, b

p3st practice, since experience in the department will always

be a significant factor in an employee's qualification level.

,T rT hlS agreed, in the instances _. i l. ronsent Decree AT&T has a0x. >Bv executing the vonsem

il which the affirmative action override applies, to limit its

- 9 -

T

bargained-for management prerogative or determining the

employee best qualified for promotion, so long as it promotes

a basically qualified applicant from an under-represented group.

The unions urge that it may not do so without illegally

breaching their collective bargaining agreements and the

rights of some of the employees they represent.

The Union Contentions

Claiming standing as representatives of their members

and by virtue of the conflict between the affirmative action

override and the collective bargaining agreements, the inter

i o r unions attack the Consent Decree on a number of grounds.

Some of those grounds transcend tne issue of purport

conflict between the decree and the collective bargaining

agreements. They recognize that in making tneir Droad 0au=

challenge they may oe acting inconsistently with

interests of some of the persons whom they represent in the

collective bargaining process, but joint W that this potential

• • . the collective bargaining relationship,conflict is innerent in tne l u u

See Caoweil Co. v .. W ^ ^ n ^ d d i r i ^ t u n . i t ^ a n i g a t i o n .

420 U.S. 50 (1975). Since the anions object to tne claimed m

, decree and the promotional seniorityconsistency between the aecree anu f

provisions of their contracts, they have standing to assert all

grounds of invalidity of the decree which would result in the

10

elimination of that conflict. Moreover they are appropriate

representatives of their members within the standing test of

c<.~. n „ h v. Morton. 405 U.S. 727 (1972). Thus we will con-

. f statutory and constitutional challenges,s icier eacn or tnerr staiutui^

ant-rv of the decree was an abuse as well as the contention that entry

of the district court's discretion.

A. The Consent Decree and Third Party Interests

The unions contended in the district court, and contend

somewhat less vigorously here, that it was improper in a Consent

Decree to award relief affecting third party rights. That

objection is meritless. To the extent that third party rights

in which the unions are interested have been affected, they were

allowed to intervene and be heard hr this case. They do not

dispute the factual predicate of the decree, the prior patterns

and practices of discrimination. If this were a litigated

judgment the fact that they and their members did'not cause

the discrimination would not prevent relief affecting tnrrd

parties. franks v. Bowman Transth-£°-,424 U.S. 747, 778

(1975). At best, in a fully litigated case, they would be

entitled to be heard only on the appropriateness of the

remedy. They have been heard on that aspect or the case.

Class actions frequently affect the interests of persons

who are before the court only by virtue of the opting out

- 11 "

. • * tj Civ P 23(c) . We have approved theprovisions of Fed. K. trv. . v )

settlement of those actions even over the objection of class

members who think additional r'elief should have been granted. E ^ . ,

V. Pittsburgh Pla t e j n a s ^ . 494 F.2d 799 (3d Cir.),

cert, denied. 419 U.S. 900 (1974); Acs Heating & Plumbi£S.

v. Crane Company. 453 F.2d 30 (3d Cir. 1971).

These cases hold that approval of such a settlement,

arrived at after negotiations between the defendant and the

* ,4 t i i-.a s£d. only If ths courtclass rcprcsonC3.tIvo, will -

abused its discretion in approving it. There is, of course,

a difference between approving a settlement benefiting a

plaintiff class whose representative negotiated it, and

approving a settlement imposing burdens on an unrepresented

class of defendants. The recognition of that difference

was the very reason why in E H u a l & g o l o f f i ^ ^

.... .. V American Teleoho j ^ & J S ^ ^ E k ^ B ^ .

506 F.2d at 741-42, we held that C17A could move to intervene

as a defendant. Following intervention the unions were per-

_ mnvince the court that the relie^ mitted a full opportunity lo conv_nce

, j /-'—ot- eauired to remedy .-heAT-ST had agreed to went beyond tnat a equ

jp r u p case before us is, for all practica violation. The posture of the case o

- 12 -

—--,— -7 '■■'T'1■ r* •: mzi: *. '• VJmrt.v z. ur*: • .* ♦* ■* v

purposes, that of a fully litigated decree.

B. The § 703 Contention

Advancing essentially-the same argument that we

expressly rejected in United States v. Inc'1 .Union .of

Elevator Const.. 533 F.2d 1012, 1019 (3d Cir. 1976), the

intervening defendants urge that §s 703(a), 703(h) and 703(j)

of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. §5 2000e-2(a),(h),(j), prohibit the

district court from providing for an affirmative action plan

containing interim targets and goals, and prohibit an affirma

tive action override. As we noted in Elevator Constructors,

that argument is foreclosed by j ^ o h s j J ^ owTian Transp. Co..,

supra, 424 U.S. at 757-62. Even the Justices who wrote separately

in Franks acknowledged that 5 703 is not a statutory limitation

upon the remedial authority conferred on the district courts by

5 706(g), 42 U.S.C. § 2000s-5(g).

C. The § 706(g) Contentions ' •

The intervening defendants jaiso urge several separate

challenges to the decree, based on their interpretation of i 706(g).

The first of these is that the section prohibits quota remedies,

and that the interim targets and goals of the Consent Decree

amount to such a remedy. That challenge is also foreclosed

by Elevator Constructors, supra, and we will not repeat the

analysis of the legislative history of the 1972 amendments

13

3

to Title VII upon which w« « U « d in rejecting it.

The unions contend that Elevator Constructors is ars-

• u vt fi,,f it d<d not deal with competitive senioritytin^uishable in that n u-u° ̂- .

out only with new hires. In one sense that is true, for the

case dealt with a remedy in an industry where employers relied

upon a hiring hall and a transitory work force. But the blunt

fact is that the union membership quota remedy we approved in

r1o„.for Constructors did involve competitive seniority with

respect to referrals from a hiring hall. 53S,F.2d at 1017-18.

More significant than our decision in the hiring hall context,

however, is the Supreme Court's holding in Tranks v f B.q g aa

TransO, Co., suora, Chat- a change in competitive seniority rs

, , s , Tjr, orP not free to reconsidera permissible § 706(g) remedy. We are not

. r „ _ . ™ wa do not think if is appropriatelythe issue. Even rr we

a ■ this case since the decree actually preserves presented rn thrs case, oiul - . .,

- • i. _ ond only - modiries tiVislayoff and rehire competitive senro

method of selection for promotion W transfer. It affects

cot all seniority rights, but only some. And among two equally

basically qualified under-represented group applicants, for

example, the seniority provisions would still operate, even with

respect to promotion and transzer.

3 538 F.2d 1012, 1019-20

14

The unions’ najor challenge Co the decree, however,

is that in all our prior Title VII remedy cases, and in those

in the Supreme Court as well,'the remedy provided relief only

in favor of identifiable victims of specific past discrimination.

They contend that § 706(g) proscribes any decree, even in a

class action, which would permit relief to a minority group

member who could not so identify himself.

The intervenor defendants misread our prior authority.

Nothing in the decree which we approved in Elevators Constructors

limited its applicability to blacks who had applied and been

rejected for membership in the union. The decree ran to the

benefit of the class of persons found to have been underutilized

by virtue of a discriminatory pattern or practice. Moreover,

the contention ignores the fact that in this case the Unit

States sued to enforce Executive Order No. 11246.. _ In Contractors

Ass'n of Eastern Pa. v. Secretary of Labor, 442 F.2d 159 (3d Cix.

1971), we held that the Executive 6rder was a valid effort by

the government to assure utilization of all segments of society

in the available labor pool for government contractors, entirely

apart from Title VII. Certainly that broader governmental

interest is sufficient in itself to justify relief directed at

15

classes rather than individual victims of d i s c r e t i o n . It

is undisputed that the Bell System is a major governmental

contractor. -

W e could rest on Flavor or Constructors and Contractors.

_ i ] a n a ■ni'ccscsnts in this Circuit. How of Eastern ?a. as conuroxlxng preceaen

. _p Seens Hkely that review will be sought in the ever, since il seens — ^ J

• ,-ur we discuss the merits ofSupreme Court it is appropriate that we ai

the unions' contention that 5 706(g) proscribes class relief

to classes which may contain persons who are not identifiable

victims of specific discrimination..

Befofe doing so, we note that even if we were to

accept the unions' position on § 706(g), 1:his decr3e v'OUld

have a large scope of valid operation. The chief charge

is that for years Bell System hiring practices steered

certain classes of persons into certain departments. Any

member of the affected class who became a Bell System employee

during the time the practices operated w'as affected by them,

at least to the extent that he or she was not informed that

emoloyment opportunities might exist in other departments,

we do not think that Congress, in enacting Title VII, intended

that § 706(g) remedies be available only to those .uiowl

enough and militant enough to have demanded and been refused

- 16 -

„ . ’ T " y H ... c • w . 1 s . .

- w _ * r ££. a... 7 .. t V *

what was not in fact available. All who became employees

while the Challenged employment practices operated were

individual victims of the practice. Thus the unions'

objection only'goes to the possibility that some minority

group members,hired after the offending practices ceased,

might be able to take advantage of the affirmative action

override. Ho record was made in the district court, by the

intervening defendants or anyone else, to establrsh whetner

there is a significant number of such parsons. Recognizing

that there are thousands of class members who could validly

be protected, even on the unions' construction of § 705(g),

we would find it extremely difficult to set aside the decree

in the absence of such a record. The district court in framing

a remedy could certainly balance the possibility that some

recent hires who were not affected by the offending prior

practices might be advantaged against the practicality that

the decree had to be simple enoughvin operation to achieve its

main purpose. Thus, we would not reverse even if we agreed

with the intervening defendants', interpretation of § 706(g).

That interpretation rests upon the last sentence of

that subsection:

17

,l0 order of the court shell require the admission

reinstatement of an individual as a member o.

"union or the hiring, reinstatement, or pro-

n H n . Q C an individual as an employee, or the

oav^ent to hLm of any bade pay, if such individual

was11 refused admission, suspended, or expelled,jr

was refused employment or advancemen dis_

pended or discharged for_any re,sson sex>

or National % £ £ T £ vSlation o l section 2000.-

3(a) of this title.

The unions urge that any relief going beyond class members

who can show that they, rather than the class to which they

belong,have been discriminated against is proscribed.

must be'read in light The last sentence an 3 706(gj muse u

r ,.,,p rest of the section. That of the settled construction 01- 1

settled construction is that once a Pri,a facie showing is

made that an employer has engaged in a practice w m e n violates

Title VII,the burden shifts to it to^prove that there is a

t i--nn The last sentence of § 706(g) benign justification or explanation.

snysVecisely that. Obviously, an employer can.meet an individual

V • „ rhar although that individual was a member charge by showing that aitnou0a

_ _ _ -t-Vvip'f or a drunk.,. , pices he was also a ttnsi.,of the disadvantaged cia^s nc

, ' e qiirh a reason denied employmentor an incompetent, and was for suen a

— ■----7 . T.,rM Union of Elevator Const., 538Unitea States v. pg-g) see pranks v. Bowman

F .2d 1012, 1017 & n.8 (3a Cir 19• •> • -gj Albemarle Paper to.

< « , . . .

Green, 441 U.S. 792, 302 (1973).

18

or promotion. But the sentence does not speak at all to the

showing that must be made by individual suitors, or class

representatives on behalf of elass members, or the EEOC on

behalf of class members.' The sentence merely preserves the

employer's defense that the non-hire, discharge, or non-promotion

.as for a cause other than discrimination. Nothing in the Consent

Decree prevents AT6cT from asserting that defense with respect

to individual applicants for promotion, and it is difficult to

see what interest the unions have in it.

The sparse legislative history available on the bills

which became Title VII confirm our interpretation of the sentence.-

In H.R. 7152,what is now § 706(g) appeared as § 707(e). A section-

- * -i r-i T4 t? No 914. 88th Cong. 1stby-section analyses contained _n H.R. x P*

Sess. (1964) , states of the latter.

"bio order of the court m a y _ ^ ’oire_tjge admission

Fii^Ttemant of an individual as a memoer

of the union or the hiring, reinstatement, o.

was

refused admission, suspended, or separated,^or

^TTiflised employment or advancement^., or was

suspended or discharged Joj ^EO ,

Legislative History of Titles Vil and ^

Civil'Rights Act of 1964 (hereinafter

to as "Legislative History ), P* 20-9 ( •?

supplied).

- 19 -

. k k T * J

»-■ err. :• ! t

"For cause H.R. 7152h dearly refers to an employer's derense.

went directly to the floor of.the Senate, where major changes

were made. Hone, however, substantively affected § 707(e)

except that sex was included among the proscribed bases of

discrimination, and the section was renumbered to § 706(g).

Confirming the Senate's understanding that the last sentence

merely preserved the employers' defense is the comparative

analysis of the Senate and House bills printed in the Con-

gressional Record-on June 9, 1964:

House Version

11. No order of court shall re

quire the admission or reinstate

ment of an individual_to a labor

organization or the hiring, ̂ t a in

statement, promotion of an indiv

idual by an employer if the laoor

organization or employer took

action for any reason other than

discrimination on account of race:

color, religion, or national

origin.

Senate Version

11. Same, except "sex" was

included. (This had oeen unin

tentionally omitted in House biu.

Also, court action in this regar

was prohibited where an indiv

idual opposed, made a charge,

testified, assisted,^or parti

cipated in an. investigation,

hearing or proceeding of an un

lawful employment practice o- ai

employer, employment agency, or

labor organization.

Legislative History at 3027.

The intervening defendants rely on what they consider

to be contrary indications in an explanatory memorandum on

§ 707(e) by Senators Clark and Case. Legislative History at

3044. He place no reliance on this ambiguous reference, since

the section-by-section analysis quoted above is a o,ore authoritativ

n n

indication of congressional understanding. We also note that in

considering the 1972 amendments to Title VII, Congress rejected

the Ervin no-quota amendment to the 1972 Act. It did so af^er

.specific discussion ,of United States v. Ironworkers Local .86, 443

F.2d 544 (9th Cir.), cert, denied. 404 U.S. 9S4 (1971). T'ne

"ironworkers remedy, like that in our Elevator Constructors case, * *

supra, included a new membership provision not limited to iden

tifiable victims of specific past discrimination. As we pointed

out in the latter case, the solid rejection of the Ervin amendment

confirmed the prior understanding by Congress that an affirmative

action quota remedy in favor of a class is permissible. 538 F.2d

* at 1019-20. We are reinforced in our conclusion that class relief,

without regard to the victim status of every class member, is

appropriate by the firm consensus in the courts of appeals upon

the lawfulness of class-based hiring preferences and membership

5

goals.

5 £ e. United States v. Elevator Constructors^Local 5,

supra; Rios'v.’stearafitters Local 638, 5 0 1 FM2d 622 (2d Cir 97’);

United States v. Hood Lathers Local 46, 471 r.2d 408 (2d Car ),

cert, denied, 412 U.'S. 939 (1973); United States v. N.L Indus ;nc.,

470_F.2dl54 (8th Cir. 1973); NAACP v. Eeec.ner, 50a F.2d 1017 (1st

Cir 1974) cert, denied, 421 U.S. 910 (1975); United States v. 13EW

Local 38, 428 F.2d 144 (6th Cir.), c^._d£niedi 400 U.S. 943(1970);

Morrow v. Crisler, 491 F.2d 1053 (5th Cir.), cer£. 419 U.S

895 (1974); Southern Illinois Builders Ass n v. Ogilvie 471 F.-

(7th Cir. 1972); United States v. Ironworkers „ocal 86, >4. F._ 5

qth Cix 1 cert denied, 404 U.S. 984 (1971); Patterson v. American

Tobacc^Coh^ 4 3 1 ^ 5 7 (4th Cir.), cert, denied, 45 U.S.L.W. 3350

(U.S. Nov. 2, 1976)(Nos. 76-46, 76-56). Cf. Albemarle Paper Co. v.

Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 414 n.8 (1976):

1St®

1

21 -

r.je find meritless the proposal that we distinguish,

for purposes of the availability of class action relief, between

nev7 hires and those already employed. Noth m g m the language

of the last sentence of § 706(g), upon which the intervening

defendants base their individualized remedies argument, suggests

such a distinction. Class action relief is equally available

to both new hires and employees. The only distinction between

the two classes is that in considering a seniority or promotion

remedy, a court of equity must take into account expectations

of other incumbent employees. But those incumbent employees

will be affected identically by a remedy in favor of identifiable

victims of specific discrimination as by a remedy which includes

employee members not so identifiable. The impact on meumoent

5 (continued) , .The petitioners also contend that no packpay can be

awarded to those unnamed parties in the plaintifr class

who have not themselves filed charges with the ^EOC We

reject this contention. The Courts of Appeals^that have

confronted the issue are unanimous in_recognizing that

backpay may be awarded on a class basis under Tiuie y5 * * * * * 11

without exhaustion of administrative procedures by the _

unnamed class members. See, e.g., Rosen ,v. Public Seuice

Electric 0 Gas Co., 409 F.2d 775, 780 (CA 3 1969 , and

477 F.2d 90, 95-96 (CA3 1973); Robinson v. Lorillard Corp.

444 F 2d 791, 802 (CA 4 1971); United States v. Georgia

Power * Co., 474 F.2d 906, 919-921 (CA5 1973); Head v

Timken Roller Bearing Co., supra, at 876; Bowe v. Colgate-

Palmolive Co., 416 F.2d 711, 719-721 (CA7 1969); United

States v. N.L. Industries, Inc. 479 *.2d 354,^378-379

(CAS 1973). The Congress plainly ratified this construc

tion of the Act in the course of enacting the Equal employ

ment Opportunity Act of 1972, Pub. L. 92-261, 86 Stat. 103

employees goes to the scope rather than the availability of

6

class relief.

Summarizing, none of the interveners’interpretations

of § 706(g), urged upon us as prohibitions against the inter

mediate targets, the employment goals, or the affirmative

action override, persuade us.

D. Abuse of Discretion

We turn then to the contention that even assuming

the existence of statutory authority,the district court abused

its discretion in refusing to grant the unions' motions to modify

the Consent Decree, and in entering the Supplemental Order. As

with equitable remedies generally, the scope of relief is a matter

entrusted in the first instance to the trial court. As tua Supreme

Court has made plain, however

" that discretion imports not the courts

■‘"inclination, but . . . its judgment; an.d its

judgment is to be guided by sound legal prrn-

cioles Discretion is yes ted.not for pur-

poses if •'limit[ing] appellate review of trial

courts or . . invit[ing] inconsistency and

caprici * but rather to allow the most complete

achievement of the objectives o£ ™ ^

is attainable under the facts and circumstances

of the specific case. 422 U.S at 421 Ac

cordingly the District Court's denial o- any

~ see e.g., Ostapowiczv. Johnson, 541 F.2d 394 (3d Cir.

1976), cert, denied, 45 U.S.L9. 3463 1974)! Com-

r ^ r t h “ HCe“ i D?2d 1029 (3d'cir. 1973) (per curiam) ( £

banc); Kirkland v. New York State Dept. of Correction tpt p ’ (tt.S .

■ O d 420, 430 (2d Cir. 1975), cert, denied, 45 U.S.L.J. 3ZA9 fu

October 5, 1976).

form of seniority remedy must be reviewed rn

terms of its effect on the attainment of the

Art's obiectives under the circumstances pre

sented by this record." Franks v, bowman Treasg,

Co , suoL, 42^ U.S. at 770-71.

in Franks, thf Court reviewed the denial rather than the award

of relief, but it is equally relevant to the scope of appellate

review of the award of relief as well. As we pointed out in

Part IV A,supra this case comes to us after actual litigation

by the intervening defendants over Lne scope of reli

it is closer, procedurally, to IsajSLV.,, gotten, suora, than

to Brvan v. Pittsburgh Plate Glass Co ,̂ supra,, and noo_r .

bouse Electric Cprpu, 680 F.2d 240, 247-50 (3d Cir.

1973), in which we reviewed settlements objected to by plaintiff

class members. But whether we apply the standard of appellate

review for litigated Title VII cases or that for review of settle

ments , considerable deference must be accorded the decision of

the trial judge as to remedy.

The intervening defendants ydo not dispute tha p

hiring practices violated the law, that the makeup of the work

force in many Bell System departments reflects the present

effects of those past practices, or that continuance of the

"best qualified" criterion for promotion,by rewarding experience

in a given department,would tend to perpetuate those effects.

- 24 -

rm r c t--: .. -

j re,.CPpt in their general attacks against Nor have they urged (e^c_p„ -

-r*-ion targets and goals) tnat -3--ting the all affirmative ^caon -ara

rv-representation in the available targets and goals to minority -ep.

-,JC force ,as'error. They do contend that other means of at

taining those goals might have been resorted to, and might be

. preserves for the unions theequally effective. But tne decree pres .

■ ^^lectwely for such alternative mean* . opportunity to bargain collectively _ ,

_ careful consideration to all the union s The district court gave Carerui cons

objections, and struck an appropriate balance between the integrity

o£ the collective bargaining process and the necessity for eefectiv

relief. The affirmative action override was not applied across

the board, but only when necessary to bring particular worm units

into compliance. The intermediate targets and the goals remain

subject to oeriodic review and adjustment. The decree is short

lived. It makes no intrusion- upon competitive seniority for ^

. .-e'-inres we cannot say that the layoffs or rehires. In the circumscanoes w .

court abused its discretion. 4

E. Constitutional Challenges

Finally, the intervening defendants cnallen0

decree on the ground that any court-imposed remedy requiring a

_ cp-v race or national.i ap'f'Ttieci "’ll terms or -*■> quota, target or goal de^inec _n

-p +-Va’P fifth amendment., j „ „r(V,PcS clause of tne inuiorigin violates the due process

- 25 r

i T -rrr« r t » V .‘S-w’wT

If. its broadest reach, this argument is that any class action

remedy for discrimination against minor-ities is unconstitutional,

for any such remedy cf necessity dennes the prot-c.ed

„c are not asked to go quite that far. The unions do not object

to the provisions of the deer*; prohibiting employment district-

ination in the'future. Their objection is to the provisions

for overcoming the effects of past practices. We have rejected

the same constitutional arguments against affirmative action

r erne dies in the past. United Spates v. i n ^ ----------------

Const., supra, 538 F.2d at 1018; Erie Human Relations Coma’n v ^

Tullio, supra; Contractors Ass’n qf_Eastem Pa.-v. Secretary

of Labor, supra, 442 F.2d at 176. See Oburn v. Shapn, 521 F.2d

142, 149 (3d Cir. 1975)(Garth, J.). The intervening defendants would

have us distinguish these cases because they didrot involve compet

itive seniority, and thus did not involve contractual interests of

other employees. We pointed out above that Elevatpr_Constractors

did involve competitive seniority. But in any event the proposed

distinction is unavailing. Franks v. BowmanTrang^^Co^ sugra,

holds that the contractual interest of an employee in competitive

seniority must yield to an appropriate Title VII remedy.

26

See 424 U.S. at 778. Federal statutory remedies need not be

color blind or sex unconscious.

He recognize that the remedy adopted by the district ,

court can operate to the disadvantage of members of groups

which have-not previously been discriminated against compared

to members of sex or racial groups previously subject to dis

crimination who have not themselves been discriminated against.

The remedy thus constitutes federal action which classifies

by membership in a sex or racial group, and must be held invalid

under the equal protection guarantee inherent in the due process

clause of the Fifth Amendment unless it can be shown that the

interest in making the classification is sufficiently great.

The standard applied by the Court in evaluating that

interest has differed somewhat for sex as opposed to racial

classifications. Racial classifications are subject to strict

scrutiny: the federal "purpose or interest" must be 'both con

stitutionally permissible and substantial,^ and the use

classification" must be"’necessary . . to the accomplishment'

~ 7 i cn* or, strengthened by the Supreme Court'sOur conclusion is s t ^ „ o£ Will^m.sburgh,

recant decision w 4221 (U.S. March I, 1977). There,

In% V - that'racial quotas could permissibly be usee

tne ieetsia^ve^apportionment pursuant to a constl-to efiecL^^i:s .at p Fhe claims of discrimination oytutional peueral statut . , reapportionment

petitioners were unavailing where the ™ * f ^ * * * taation.

was designed to remedy the ef_ect j. P- 424 u>s_ at 775

See also Franks v. Bowman Transp •> - ' ^ 446 F>2d 652,

United States v. Beth^ t̂ cC°r^ [ F 2d 1236,663 (2d Cir. 1971); Vogler v. McCarty, Inc.,

1238-39 (5th Cir. 1971).

27

of [Che] purpose or the safeguarding of [the] interest." In

re Griffiths, 413 U.S. 717, 721-2 (1973)(footnotes omitted).

On the other hand, "classifications by gender must serve •

i

important governmental objectives and must be su d stantially

related to achievement of those objectives." Craig v. Boren,

45 U.S.L.W. 4057, 4059 (U.S. December 20, 1976). The present

classifications are permissible in the case of race, and are

thus permissible a fortiori with respect to sex.

federal interest in the present case is that of

remedying the effect of a particular pattern of employment

discrimination upon the balance or sex and racial groups

would otherwise have obtained -- an interest distinct from

that of seeing that each individual is not di.sadvantaged by

discrimination, since it centers on the distribution of benefits

among groups. This purpose is "substantial" within the meaning

8

of In re Griffiths, supra, where the Supreme^Court said that

"a State does have a substantial interest in the qualifications

of those admitted to the practice of law . . 413 U.S. at 725.

8~The Court said in footnote 9 of its opinion that: '̂ The

state interest required has been characterized as overriding,

[McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 1S4, 196 (1964)]; Loving Y-

Virginia, 388 U.S. 1, 11 (1967); 'compelling,' Graham v. Richardson^

[403 U.S. 365 , 375 (1971) ];' important, 1 Dunn v .. B_l_umstein, 405 U.S.

330, 343 (1972), or "substantial," ibid. We^attribute no particular

significance to these variations in diction.

28

The governmental interest in having all groups fairly repre

sented in employment is^at least as substantial, and since that

interest is substantial the adverse effect on third parties

is not a constitutional^ violation. Moreover, the same exclusic

of such members could conceivably result from remedies afforded

to individual victims of discrimination. This remedy operates

no differently. Furthermore, as we noted above, the affrrmativ

action override is necessary to the practical accomplishment of

the remedial goal.

It will doubtless be possible to detail, and thus to

employ remedies other than quotas, for many individual instance

of discrimination. But it is also true that much discriminatic

cannot be proved through evidence of individual cases, even tnc

a prima facie case can be made out on the basis of statrstrcal

other evidence. It will, for example, be nearly impossible to

show that individuals were deterred from applying for hiring o:

promotion, or from attempting to meet the.prerequisites for

advancement, because of their well-founded belief that a partic

employer would not deal fairly with members of their particular

sex or racial group. Moreover, even apart from problems of

9 See findings in House Judiciary Committee Report on

• i j < — 1? ■p n p T e^islative History of TitleH.R. 7152, reprinted m E.E.O.C., he ^ia

VII and XI of Civil Rights Act of 19o4 at 2018.

- 29 -

. * - 'f t / * • ■

proof, goals and quotas are necessary to counteract the effects

of discriminatory practices because some victims or discriminate:

no longer seek the job benefits which they were discriminatorily

denied. '.In such cases, quotas are needed to counteract the erfec

of discriminatory practices upon the balance or sex and racral

groups that would otherwise have obtained.

The use of employment goals and quotas admittedly involve

tensions with the equal protection guarantee inherent in the due

process clause of the Fifth Amendment. But the remedy granted

by the district court is permissible because it seems reasonably

calculated to counteract the detrimental effects a particular,

identifiable pattern of discriminatron has had upon.t..- P ?

Of achieving a society in which the distribution of jobs to

basically qualified members of sex and racial groups is not

affected by discr initiation.

The judgment appealed from will be affrrned.

TO THE CLERK OF THE COURT

please file the foregoing opinion,

Circuit Judge

30