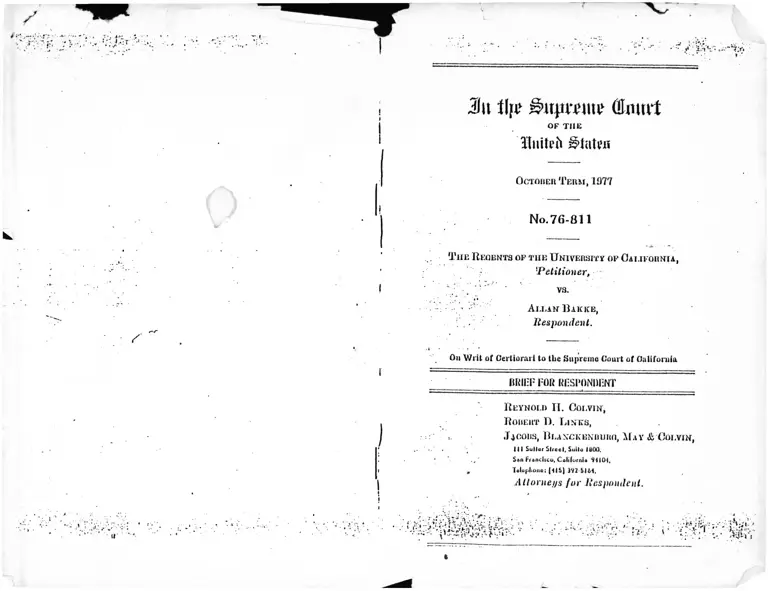

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke Brief for Respondent

Public Court Documents

October 3, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Regents of the University of California v. Bakke Brief for Respondent, 1977. 77d81bef-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0e05c963-a5cc-4bba-a50e-a49c4213a727/regents-of-the-university-of-california-v-bakke-brief-for-respondent. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

J l l % ^ I tJ U T H tV (U x u if t

OF THE

llu ite ft 0 J a tim

O ctoiier T erm , 1977

I

N o.76 -8 1 1

T h e R egents of t u e U niversity of C aeifqhnia,

’ 'Petitioner,

I •• vs.

A m ,AN B akice,

; . Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supremo Court of California

HRIFF FOR RnSl'ONIlFNT

R eynoer I I. CJoevin,

Rorert B. L inks,

.TjCOllS, B e a NCKENRURO, i f AY & UOEVIN,

111 Sutler Street. Suita 1800.

San franciico, California 94104,

Tolopltone; (416) 392 5164.

Attorneys for Respondent.

•V:

f t - #

-f s

i

/

Subject Index

Pages

Opinions below ........................................................................ j

Jurisdiction ............................................................................... g

Question presented.................................................................... 2

Constitutional provision involved ........................................... 2

Statement of the caso ........................................ 2

Baldm's Application for admission to the medical school 3

Admission to tho Davis Medical School............................ 5

Tho regular admission procedure ................................... g

•

Bakko’s interview and rating ........................................... 7

Tho special admission program ....................................... 9

Tho discriminatory results of the special admission

program .......................................................................... 72

Proceedings in the trial court ......................................... 75

Proceedings on appeal ..................................................... jg

Summary of argument ............................................................. 22

Petitioner violated Allan Bokkc’s right to ctpial pro

tection ........................................................................... 22

Tho California Supreme Court correctly decided this ease 25

Argument ................................................................................... ’ 26

Introduction ...................................................................... og

I

Tho special admission program violates Allan Bakko’s

right to tho equal protection of the law s.................... 27

A. The nature of the special admission program___ 27

1. The program is a racial ipiota ......................... 27

2 Petitioner’s quota uproots individual constitu

tional freedoms and replaces them with a de

structive system of group rights ................... 30

3. There is a distinction between petitioners quota

and the concept of “ affirmative action” .......... 35

•1. The constitutionality of petitioner’s quota is

subject to judicial review ............................. 39

11 Suiui-CT In dux

, Pape

Ii. The .special admission program deprives Allan

Bakkc of equal protect ion ..................................... ,|j

1. The rights (panted liy tins Fourteenth Amend

ment arc personal in nalnro ............................ ,jj

2. Allan Bakko's personal right to equal protec

tion lias keen violated ....................................... j5

II

The California Supremo Court correctly decided this ease 53

A. The court below properly considered this action

to he u case of racial discrimination .................... 53

II. The court below correctly applied the appropriate

judicial standards in judging the constitutionality

of petitioner's quota .............................................. 5;j

0. The decision below docs not require a return to

all while" professional schools ............................ go

I). 1 he court below rejected the use of a racial quota

to govern admission to professional school ......... fii

Conclusion ............................................................. 83

r r

/

Tabic of Anfliorilies Cifed

Cases Pages

A levy v. Downslalc Medical Center, 30 X V °d 3‘»C .318

N.I5.2d 537, 381 N.Y.S 2d 82 (|07f.) .................... ". ..21,27,58

Alexander v. Louisiana, ‘105 U.SJ. 025 (1072) 21

Anderson v. San Francisco Unified School District 357 P

Supp. 218 (N.D.Cnl. 1072) ................................. ' 37 38

nosou v. Hippy, 285 F.2d 13 (5lh Cir. 1000) .................... 50

Broidriek v. Lindsay, 30 N.V.2d (ill, 350 X E.2d 505 385

N.V.S.'Jd 205 (1070) ......................................................... .. C2

Ilrown v. Board of Education. 317 II.S. 183 (1051) . ! ! ! . . 45

Caiter v. Hallagher, 152 P.2d 315, modified on rch en hanc

•152 F.2d 327 (8th Cir. 1072) .......................................... ’ 3fl

Chance v. Board of Examiners, 531 F.2d 003 (2d Cir. 1070) 38

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. (Hickman, 370 PSunn

721 (W.D.Pa. 1071) ................................................ 3fl

Day-Briln Lighting, Inc. v. Missouri. 312 US. 121 (1052) 45

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman, 15 U S L W 1010

(US. June 27. 1077) ......... ............................................. 5a

DoFunis v. Odegmird, 82 Wash.2d 11, 507 P.2d 1100 (1073),

eert. granted, 111 US. 1038 (1073), vacated as moot 110

U S. 312 (1071) ........... 21, 20, 27, 20, 30,32,10, 13, -1 I, -19, 57 58

Dunn v. Blumxtcin, 105 U S. 330 (1072) .......................... 1G 50

EEOC v. Sheet Metal Workers Local 28 53° p 0.1 s°l

(2d cir. 1070 ................................... ■ 38

Flanagan v. President and Directors of Ocorgelown College,

lit 1* .Supp. 3/7 (D.D.C 10/0) .......................... ‘>.| 3j 38 pi

Pranks v. Bowman Transportation Co., Inc., 121 U.S. 717 ' 21

Urif/in v. Illinois, 351 I'.S. 12 (1050) ...............................

Criggs v. Duke Power Co., 101 U S 121 (1071) 35 3f,

Hall v. St Helena Parish School Board, 107 p.Hupp. 010

(E.D.Lu. 1001), aff'd per curiam, 808 US. 515 ( 1002) ..5|,52

Harper v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 350 P.

Supp. 1187 (M.D.Md ), moditied on other grounds and

(di d soli until., Harper v. Kloslcr, 180 P 2d 1131 ( Ith

Cir. 1073) 38

IV Table ov AuTiionmEa Cited

Pages

Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elect ions. 383 | J.Fi. 663

(10(i(i) ................................................................................. II, 17

Hernandez v. Texas. 317 U.S. 175 (1051) ............................ .jo

Hirubuyushi v. United Stales, 320 US. 8l (1013) ............. r>5

Hobson v. Hansen. 280 P.Supp. 101. n.107 (D.D.C. 1070) .. 55

llopkins v. Anderson, 218 Cal. G2, 21 l\2d 550 (1033) ___ 22

Hughes v. Superior Court, 32 Cak’ d 850 11018) ............... 55

Hughes v. Superior Court. 330 U S. ICO (1050) ................. 50

Huparl v. Board of Higher Eduention, 120 P.Supp. 1037

(S.O.N.Y. 107G) ....................................................... 21 38

Kutzcnbuch v. Morgan, 3S1 U S. Gl] (10GG) ........................ 33

Kirkland v. Uepartment of Correctional Services, 520 P.2d

120, reh. cn banc denied, 531 F.2d 5 (2d Cir. 1075), ecu

denied, 07 S.Ct. 73 (1070) .....................................’ _ 3S

Koremat.su r. United Stales, 323 U S. 211 (1011) ___7 7 55

Kramer v. Union Free Seliool District, 305 U S. G21 (10G0) 37

Can v. Nichols, 113 U.S. 5G3 (1071) ................................... 38

liigo v. Town of Montelair, 72 N.J. 5, 307 A.2d S33 ( 107G)

..................................... 21.33,38,02

Liiulsloy v. Natural G'urlmnic Oas Co., 220 IJ.S. Gl (1011) 15

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (10G7) ............................35,3G. 37

McDonald v. Santa Fo Trull Trausportalion Co. 327 U.S.

273 (1070) . . . . . ................................................................... |8

McLaughlin v. Florida, 370 U.S. 1SI (1001) ........... 7 7 7 jG37

McLanrin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 330 U.S. G37 (1050)

......... . ..........................................................................30,30. 33'

Meyer v. Nebraska, 202 U.S. 300 (1022) ............................... ;j;i

Millikcn v. Bradley, 35 U S LAV. 3873 (U.S. June 27, 1077)

....... ............................................................................. Gl

Missouri ex ivl. Gutncu v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1038) 10. 13, 50

Morlou v. Maueari, 317 U.S. 535 (1073) ................. 13, 30

12, 37Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. G33 (1018)

1‘ ugel Sound Oilliu tiers Ass’n v. Moos, 88 Wash “d G77

l‘ -*d (1077) ......................................................... ‘ jj-j

Bail way Express Agency, Inc. v. New York, 330 U.S 100

( 1010) ............................................................ ■ |5

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1001) ....................

Hollins v. Wright, 03 Cal. 305, 20 I*. 58 (1602) 7 7 7 7 7 22

Taui.e of AuTnoiiiriES Cited v

Shapiro v. Thompson, 303 U.S. G18 ( 10G0) .................... 30 3^53

Shelley v. Kraemer, 331 U.S. 1 (1018) ............. . *33 31

Shelton v. Tinker, 301 U.S. 370 ( I0G0) 7 7 7 7 7 ’ 53

Sipuel v. Board of Hegcnts, 332 L'.S. G31 (1018) ............. .30 33

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 3IG U.S. 535 (1012) ................. ‘ 4>>

Slaughlcr-IIou.se Cuscs, 83 U.S. ( 1G Wall.) 3G (1872) . .. . . 31

Stale Department of Administration v. Department of In

dustry, Labor and Human Solutions 70 Wis ‘*d 050

N.W.Jd 353 (1077) ........................ ............. ~ .. .7 ’ ~ " <j->

Swann v. Chnrloltc-Mccklenlnirg Board of Education 30'’

U-S- * U‘J7i) ..................................................... * ~40 ^

Sweatt v. Painter, 330 U.S. 620 (1050) ..........................30 33 -17

Tukahaslii v. Fish £ Game Commission, 331 U.S. 310 (1018) 37

United Jewish Organizations v. Carey, 07 S.Ct. 006 (1077) 5’

Uzzell v. Friday, 517 F.2J 801 (3th Cir. 1077) ................... 37

Washington v. Davis, 32G U.S. 220 (107G) ........................ 53 53

West Virginia Stuto Board of Education v. Burnette 310

US. G21 (1033) ....................................................... * 5J

Williamson v. Lee Oplieul Company, 318 U.S. 383 (1055) 35

Vick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 IJ.S. 356 (1880) .......................... ,j2

Constitutions

California Constitution:

Article 1, Section 21 ....................................... 3 15 17

Article IX, Section 0, Suhd. f ................................... ’ 00

United Stales Constitution. Fourteenth Amendment

................................................2, 3,15, 22. 23, 21, 26,31, 33, 35, 63

Congressional Reports

110 Cong. Bee. 7207 (10G1) .............................................. 3J

110 Cong. Bee. 7120 (10GI) ................................. 7 37

Regulations

•15 C.P.B.:

............................. .............................. 3 37

§580 1-80 13 ....................................................... .............. ^

vi T auix of A uthorities Cited

Statutes Pages

Civil Rights Act of lCli6 (12 U.S.C. § 1081) ........................ -JJ, |5

Civil Rights Act of 10G4 (12 U.S.C. § 2000a It) ................... 35

Title VI (12 IJ.S C. § 2000d) ............................. 3.15,17,37

Title VII (12 U.S.C. § 2000c) ................................. *30* 37.* I I

Title VII (42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2( j ) ) ...............................30*37

Voting Rights Act of 10G5 (12 U.S.C. § 1073) .................... 52

Texts

llickel, The Morality Of Consent ut 133 (1975) ................... 17

Ilickcl, The Original Understanding and the Segregation

Decision, GO llarv. L. Rev. 1 (1055) ............................... 75

1973-1071 nnllclin, School of Medicine, University of Cali

fornia, Davis, at 12 ............................................................. jq

Cohen, Race and the Constitution, 220 The Nation 135, 110

( 1!,7S) ............................. ,’ .20,33,-18

DeEunis Symposium, 75 Colum. L.Itev. 183 (1075) ............. 27

Dixon, The Supreme Court and Equality: Legislative Classi

fications. Dcsegyegfifion, and Reverse Diseriminalion, G2

Cornell L. Rc\( 401, 105 (1077) ............................... ‘ 75

Ely. The Constitutionality of Reverse Racial Discrimination,

41 ll.Chi. L. Rev. 723 (1074) .......................................... o(i

(1 Inzer, Affirmative Discrimination (1075) ............................ 3ti

Uart £ Is vans. Major Research Efforts of the Law School

Admission Council, Apr. 107G........................................... gp

Lavinsky, A Moment of Truth on Racially Based Admissions.

3 Hastings Const. L. Q. 870 (107G) ............................... 20,31

Lavinsky, DeEunis v. Odcganrd: The "Non Decision" With

a Messuge, 75 Colum.L.Itev. 520, 527 (1075) .................... 33,51

Law School Admissions: A Report to the Aliunnif A Is),

127 Cong. Rcc. 113530 (daily cd. Apr. 25, 1077) ........... 01

Linn. Test Bias and the Prediction of Cradcs in Law School

27 .1. Legal Kiltie. 203, 322-323 (1075) .......................... ' 30

T auix ok A uthorities Cited vii

Note. Reverse Discrimination, 1G Washburn L.J. 421 (1977/

Novick £ Ellis, Equal Opportunity in Educational and Em

ployment Selection, 32 American Psychologist 30G (1077) 10

Pastier, The D. Ennis Case and the Constitutionality of

referential Treatment of Racial Minorities, 1074 Sun Ct

Rev. 1 ......... ’ 1 • -

..................................... ........................... ......... 26

Kedish, Preferential Law School Admissions and the Equal

l rot eel ton Clause: An Analysis of the Competing Ariru-

nicnts, 22 U.C.L.A. L. Rev. 313 (1071) . . . . . . . . . . . ofi

Rostow, The Japaneso-Ainerican Cases—A Disaster 54 Vale

E L 480 (1915) ............................ * „

Scdler Racial Preference, Reality and The Constitution:

Bakke v. Regents of the University of California, 17 Santa

Clara L.Kev. 320, 350 (1077) ............................ 30

Similar, America in the Seventies at 30G (1077) 2G 33

Sowell, Black Education, Myths and Tragedies at 202 '

(1 ........................................................................

Statement of Unman Rights Commission of tho City and

County of San Francisco, .March 20, 1072 33

Suslow. (trade Inflation: End of a Trend?, Change, March

10t7 at 41-45......... * '......................................................... 5

^ 1 Jo' Vr/ **" Etierpretive History ( 10G8) at

Wilkins, The Case Against Quotas, ADL Bulletin, March ^

............................................................................. 2G

J n l ( ; t ‘ g a g m - u u ' ( l l n u r f

OK THE

l !luiU’ i> S ta te n

Octoheii Tkiim, 1977

No. 70-811

T he R egents op th e U niversity op Oalipounia,

Petitioner,

vs.

A li.an R akice,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of California

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

OPINIONS liELOW

The opinion of Die California Supreme Court is re

ported at 18 Cal.3d 31, 533 P.2d 1152, 132 Cal. Rptr.

080. The modification of the opinion is reported at

IS Cal.3d 2521». The opinions, findings of fact and con

clusions of law and judgment of the stale trial court

are contained in the Record filed with this Court* as

follows: Notice of Intended Decision (R . 280-300),

Addendum to Notice of Intended Decision (R. 331-

Mlcrcuflcr designated us “ It”.

o

385), Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law (1L

380-392) and Judgment (If. 393-395).

JURISDICTION

The jurisdictional requisites are set forth in the

Brief for Petitioner.

QUESTION PRESENTED

Is Allan Balcho denied the equal protection of the

laws in contravention of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the United States Constitution when he is excluded

from a state operated medical school solely because

of his race as the result of a racial quota admission

policy which guarantees the admission of a fixed num

ber of “ minority” persons who are judged apart from

and permitted to meet lower standards of admission

than Bailee ?

/ _____

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISION INVOLVED

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution provides in pertinent part; “ . . . nor shall

any Stale . . . deny to any person within its jurisdic

tion the equal protection of the laws.”

STATEMENT OP THE CASE

The primary issue in this case is whether the racial

quota admission procedure,employed by petitioner at

the Davis Medical School ( “ the medical school” ) de-

3

t Z a-n “ k'“ 1,(3 10 11,0 of

< » *■*"■ .o tin, M.iUcd

Alton BoLla SVadnolcd from II,e University „(

(mncbolo in 1002 will, „ Bachelor of Science dc-rea

n mechanical engineering. After receiving I,is dcnce

ho dal graduate work in mcchnnirnl „ . ̂ ’

tl*o University of Minncsoaf “ Wneenng at

servcf] fn,. e * ta for ft ye»>- and then

Corps. AVliilo'in ? fari.na

nl.ont Die ^ sih iiity of ^ ^ ^

S lm f T r 'r B l,h " ,ili" lr>' “ m ee, '"> attended Stanford University ami. in J „„e of 10 70 , received

3 " S‘ “ r S1c,c,,“ ‘ ‘ ‘ B ™ in mechanical engineer-

t,. Willie studying for liis muster's degree nnd for

“ lirse '"l;, “ » I * W "in' vnrionl

(It! S U i n ) * ""'dieiil ednention

As w 'iold r !° -'nCt,i‘;i" SC|,“ I l,US >“ l 'mnn caiy.■As lie (old the admission committee; r

“ Til 11171 my couth,,lonsly increasing interest in

^ s r s ' i i S ^ ' i r ,,eca" ’0 °

_ j ! u r « • -

„ uumpliiint n.ikke filed lvith n,,. V d r-

Com1 allowed that tl,c speejal admission

nglilfi under the Pomlecnlh A,,,em u T " ‘i, ,,is

Oonstii»uion. (he Privih-cs ami Inim., 1 V,! IhiilctJ Slaton

foniiii Constitution (Ani’cie I Section "on* C*;n'“Uof ‘ he t ’ali-

Olvil Itifjlils Act of 1004 (.,2* USC toloo Vl offoiiiut in llakkc-a filV0r us ,‘0 „ jHJOOd). 1 he trial court

Supreme Court afiirmcd, relyiiiK cxelu ' i ee lv" i*'0 1C''a,iforn‘“

lioiial grounds. (Peliiion for C'crlioriiri ' t C y °!‘ c«nslilu.

i»i» ica. ,8

i

which I believe demonstrate the strength of my

motivation and eonnnilinent to obtaining a med

ical education and becoming a physician. While

employed fnll-limo as an engineer, I undertook

a near full-time course load of medical prereq

uisites—biology and chemistry. To make up class

and commuting hours, I worked early mornings

and also evenings at my job. This was an ex

tremely taxing schedule in terms of time and

effort, and involved a significant financial com

mitment as well. My desire to become a physician

is further demonstrated by my involvement in

recent months as a hospital emergency room

volunteer. My experiences in this work have

strongly reinforced my determination to become

a physician.

Par from being wasted, I believe my engineer

ing experience would help me to approach medical

problems with insights different from those of

most physicians. I strongly believe that my hack-

ground iivfhalhemalies, computer programming,

mechanical design and analysis could he usefully

applied in medicine.” (li. 2:13)*

JOiU! of the inedieal school interviewers nolcil IhiU (iakke's en

gineering background could he n (-real asset to his potential ca

reer in medicine:

“ In the emergency room situation he |rtal.he| has become

aware of a number of instances in which a hit of expertise in

mechanical engineering might he to some advantage to im

proving health care, fo r example, Dr. Alexander, the head

of the (emergency room) complained that he had hied for

some lime to coax a hospital supply mnnfaclurer |o design a

gurney upon which un emergency patient could he X-invcd

without being moved from irurney to table. Ital.l.e has begun

to think about this and believes that he himself could come

• up with significant design if he had Iho chance ” fit ° M

5

/n m w 08 ° VtilaU ,I" ‘,‘‘l'g‘ aduftte grade point average

((HU A) was 3.51 on a scale of 1.0 (ft. 230). His

grade point average in the sciences (SOPA) was 3.45

L. Ul)0n ffi'aduatimi he was elected to Pi Tan

■gma, the national mechanical engineering honor

society (ft. 232). b 1

Bakko took the Medical College Admissions Test

(MOAT), which is divided into four sections (verbal,

quantitative, science and general information) and is

scored on a percentile basis. He scored in the Of.th

percentile (verbal), 04th percentile (quantitative),

9/th percentile (science) and in the 72nd percentile

(general information) (ft. 230).

In )073 and 1074 ftakkc duly and timely submitted

Ins application to Ihe medical school for admission to

the classes of 1077 and 1078, respectively (ft. 387).

Admission to The Davis Medical School

Petitioner, faced with the annual task of selecting

an entering class of 100 students, has established not

one, hut two, admission committees. For the most

part, the committees act independently of one another,

apply different standards to Ihe particular candidates

they judge and, ultimately, select students for Iho

tirst year class whoso qualifications differ markedly

depending upon which committee considers their

applications.

i

•IlidAo corned lax undergraduate grades before the occurrence

J ‘ o commonly referred to phenomenon of “grade inflation"

Mv I f ! l a *•*«i « i w . »E i,;

fi

Omj of these committees, the regular admission

committee, selects 81 of the 100 members of the first

year class. The other committee, known common))' as

the “ task force committee” or “ special admission com

mittee", selects the remaining 10 members and bases

its selection upon substantially lower requirements

than does the regular committee. The specific differ

ences in the standards, and the results of their use,

are discussed below.

The Regular Admission Procedure

The regular admission procedure is conducted as

follows:

(1) To be considered for admission, a candi

date must submit his application to the medical

school between July and December of the

academic year preceding the year for which

admission is sought (R. 1-10, 218).

(2) Normally the regular admission committee

reviews the'applications to select certain indi

viduals for further consideration. Once the com

mittee has conducted this initial screening, the

applicants selected are scheduled for personal

interviews. The minimum standard adopted by

petitioner provides that no student will be inter

viewed by the admission committee if he or she

has an OQPA below 2.5 on a scale of 1.0. Appli

cants for “ regular admission” who fall below the

2.f> “ cul-olf” mark are summarily rejected (It. (id,

150-151).

(3) In 1973, the interview procedure provided

for one of the faculty members of the admission

committee to interview each applicant. In 1971

applicants were interviewed twice, once by a l’ac-

7

nlty member and once by a student member of

the committee (Id.).

(4) Following the interview, each applicant

is rated by the various admission committee

members, taken into consideration for rating

purposes are the interview summary prepared by

the inlcrviewer(s), the applicant’s OQPA, SGPA

it CAT score and other biographical and back

ground information in the applicant’s file, such as

a description of extracurricular activities work

experience, a personal statement of reasons for

wanting to attend medical school, and letters of

recommendation (R. 02-03, 155-159).

Tho committee members rate each applicant on a

scale of from 0 to 100. The ratings are then added

together and the applicant’s total rating— in essence

the admission committee’s evaluation of his or her

potential ability—is used as a “ benchmark" in the

selection of students (R. 03). I „ 1973 five committee

members rated each applicant; thus, the highest pos

sible rating for that year was a score of 500. In 1974

six committee members rated each applicant and the

maximum possible total rating increased to 000 (Id.).

Uakke's Interview and Rating

In both 1973 and 197-1 petitioner considered Bakke's

application pursuant to the above-described proce

dure (R . 09, 389).

lu 1973, Dr. Theodore 11. West interviewed Bakkc

and concluded that':

“ On the grounds of motivation, academic rec

ord, potential promise, endorsement by persons

8

capable of reasonable judgments, personal ap

pearance and demeanor, maturity and probable

contribution to balance in the class I believe that

Mr. Balclce must be considered as 21 very desir

able applicant to this medical school and I shall

so recommend him.” (It. 22b)

A summary of Dr. West’s interview was circulated

among the members of the admission committee.

Bale Ice received a total rating of 168 out of a possible

500 (It. 180). Although Balclce's average rating was

92.8 out of a possible 100, petitioner rejected his

application (It. 258).

Between the rejection of his 1973 application and

his second application in 1971, Balclcc wrote to Dr.

George II. Lowrcy, Associate Dean at the medical

school and Chairman of the Admission Committee,

protesting the medical school’s admission program

insofar as it purported to grant a preferential ad

mission quota members of certain racial and ethnic

groups (It. 259).

After submitting bis 1971 application, Balclcc was

interviewed twice. One interview was with Mr. Frank

Gioia, a student member of the admission committee.

Mr. Gioia found that Balclce “ expressed himself in a

free, articulate fashion”, that he was “ friendly, well

tempered, conscientious and delightful to speak with”,

and concluded that, “ T would give him a sound

recommendation for [a] medical career.” (It. 228-29)

Mr. Gioia gave Balclce an overall rating of 91 (It. 230).

The second interview was with Dr. Lowrcy, who, by

coincidence, was the person to whom Balclce had writ-

i)

ten in protest of the special admission program. Dr.

Lowrcy and Balclce discussed many subjects during

the course of the interview, including the medical

school’s decision to grant a preferential admission

quota to certain racial groups (It. 228). Apparently,

they disagreed over the merits of that decision (Id.)!

In contrast to the two other persons who had inter

viewed Balclce, Dr. Lowrey found him “ rather limited

in his approach” to problems of the medical profes

sion and said that, “ the disturbing feature of this

was that he had very definite opinions which were

based more on his personal viewpoints than upon a

study of the total problem.” (R. 228) Dr. Lowrey

gave Balclce an overall rating of 86 (It. 230).* Other

members of the admission committee, after reviewing

these interview summaries, as well as Balclce’s overall

tile, rated him 96, 91, 92 and 87, for a total rating

of 519 out of a possible 600; Balclce’s average rating

on his second application was 91.2 (h i ) . Again, peti

tioner rejected his application (ty. 273).

The Special Admission I‘ ro(jT(un

At the same time as it administers and maintains

the regular admission procedure at the medical

school, petitioner also operates and maintains at

Davis a “special admission program’’* which, in

petitioner’s words, purports to “ increase opportuni

ties in medical education for disadvantaged citizens”

227̂ ** kouroy’s complete interview summary is found at It. 220-

, l,C|'!oirli,T'r AC-0‘fV ,> I»,0|?r«»l «■* die “Task Force Program"(Jt. 1 Do 190; Brief tor Petitioner ul 9).

10

(It. 195-90). Although the University originally dc-

clnved that the program was for disadvantaged stu

dents regardless of race (It, 01 00, 80), no definition

of the term “ disadvantaged” has ever been formulated

by the University (It. 103-01), the program Inis been

heavily staffed with minority personnel (It. 102-03),

and only minority applicants have been admitted to

the medical school through the program (It. 168, 201-23

and 388).'

The special admission program is almost as old as

the medical school itself. The school opened in 190S

and the program commenced only, one year later, in

September of 1909. Since that time, petitioner annu

ally has set aside and nllotcd to the program 10% of

the places in the first year class (It. 104, 108). On

these facts, the slate trial court concluded that the

program constituted a formal racial quota (R. 3S8).

The California Supremo Court, by a majority of 0-1,

agreed (Pet. App.-A, p. 39a; 18 Cal.thl at 01).

Petitioner administers the special admission pro

gram as follows:

(1) Applicants are asked to indicate on their

applications whether or not they wish to he

'Al trial anil in Ilia court below, petitioner ilenieil that race

was tho pivotal factor in the special admission pio«;rain (It. 30,

0a, 73, SO). In light of llie instant record, which confirms the

existence of a formal racial quota al the medical school (It. 380,

n!)0), it is interesting to note that in its 1!I73-197I IlnUi-lin,'

distributed to Ualdce and other potential applicants, petitioner

Slates without qualification that ‘'jr|cli|fions preference and race

are not considered in the evaluation of an applicant." 1073 1071

Hi.i i k t i .v , S ciigoi. or Mm ic in e , L'm vciisitv or Oai.iio u n i\ D im s

at 1*2.

11

considered for admission under the special

admission program. The 1973 application

form, prepared by the medical school,

allowed an applicant to indicate whether or

not he or she wished to he considered as

an “ economically and/or educationally dis

advantaged” applicant. On the 1971 applica

tion form, prepared by the American Medi

cal College Application Service (AMOAS),

and used by slightly more than half of the

medical schools in the country, the pertinent

question asks; “ Do you wish to be con

sidered as a minority group applicant?”

(R. 65-80, 146, 197, 232, and 292) According

to petitioner’s published admission statistics

tho word “ minority” includes “ Blacks” ’

Asians , Chicanes”, and “ American

Indians” (R. 203-205, 216-218).

(2) Once an applicant has indicated a desire to

be considered under the special admission

program, his application is evaluated by a

special subcommittee, separate from the

regular admission committee (11. 65, 1 6 1 -

16 2 , 388). This special subcommittee is com

posed of minority and non-minority faculty

members, and students from minority back

grounds only (R, 162). It conducts a separ

ate screening procedure, parallel to that of

the regular admission committee (R. 6l-6fi).

The special subcommittee, however, is not

bound by the medical school standard that

no student will be interviewed if bis OCJPA

is lower than 2.5. In 1973 and again in 1974,

minority students were interviewed and

admitted under the special admission pro-

giam even though they possessed OQPA’s

well below tho 2.ft cut-oft’ point. Minority

students admit led under the special program

possessed overall grade point averages as

low as 2.11 in 1JJ73 and 2.21 in 11171 (11. 210,

223):

(3) Following the interview, tho .special sub

committee assigns the various special appli

cants an overall personal rating, similar to

tho “ benchmark” procedure of the regular

admission committee (11. 00, 101-108). Fi

nally, the special subcommittee recommends

to the regular admission committee various

candidates for admission to the medical

school. The reconuncndultons continue to he

vuide until the pre-determined quota of It!

is filled (It, 108).

The Discriminatory llesulta of the Special Admission Program

According to^statistics puhished by petitioner, the

average applicant admitted under the special admis

sion program possesses academic and other qualifica

tions inferior to those of Gnkkc and of the average

student admitted under the regular procedure (It.

388). The following chart compares Bnkkc’s qualifica

tions with those of applicants who are regularly ad

mitted and with those of applicants admitted under

the special admission program.

Olaaa Entering In Tall, 1873

MOAT Pcrcenlilo1

x

13

SOFA* OarA'» Verb. Quan. Sci.

den.

Info.

Allan Ilakke 3.-15 3.51 05 04 07 72

Average of

Regular Admittcrs 351 3.40 81 76 63 60

Average of

Special Admittccs 2.62 2.08 46 21 35 33

Class Entering In rail. 1074

MOAT Perceutilu

sgVa OOPA Verb. Quau. Scl.

Gen.

Info.

Allan Ilakke 315 351 06 04 07 72

Average of

Regular Admittees 335 320 60 67 62 72

Average of

Special Admittccs 2.42 2.52 31 30 37̂ 18"

The above chart contains only statistics relating to

grade point averages and MOAT scores. Also consid

ered in the admission process, as previously men

tioned, is the personal interview, which provides a

further basis for the “ benchmark’’ rating given each

applicant. The benchmark rating takes into consid

eration the OGFA, SOFA, MOAT scores, the inter-

*Thc Medical College Admissions Test (MOAT), as imlcd pro-

viously, is subdivided into four sections: Verbal (Verb ), Quanti

tative (Quail ), Science (Sci), and General Information (Gen

Info).

'T'ndcrgradunlc grade point average in science courses.

'“Overall undergraduate grade point average. •

"The figures contained in this chart for the special udmitlces,

like the figures contained for the regular udmiltccs, represent

uveruye scores and do not indicate the highest or lowest achieve

ments of either group (It. 210, 223).

14

view summary and, in tuUUtion, oilier background

data in Iho applicant’s Ale, such as Hie particular

details of a “ disadvantaged” background (II. 63-66).

Even with this rating procedure, designed to

give the special applicants credit for overcoming “ dis

advantage”, applicants admitted under the special

program possessed overall ratings below those of

students rejected under the regular admission" proce

dure. Indeed, petitioner admits that some of the

special admittees received overall ratings of as much

as 30 points below Bakkc’s rating (U. 181, 388).

These facts establish that the special admission pro

gram is designed to grant, and in fact does grant, a

preferential admission quota to members of certain

racial and ethnic groups (II. 388-390). Petitioner

never has defined the term “ educationally disadvan

taged”, or the term “ economically disadvantaged" (It.

at 163-161). On the facts of this case, however, these

terms arc syntmymous with “ member of a minority

group" for, as stated above, only minority applicants,

and no non-minorilv applicants, are admitted to the

medical school under the special admission program

(11. 188, 201-223, 388).

'rims petitioner's special admission program is

based upon race. The 16% allotment to the program

of places in the first year class at the medical school

constitutes a racial quota of 16%. Under the program,

minority applicants are judged apart from and are

allowed to satisfy lower standards than Bakke and

other non-minority applicants; they are also guaran

15

teed at least 16 places in each entering class (It. 164-

168, 388, 390).

Proceedings in the Trial Court

Foljowing the rejection of his 1971 application,

Bakke instituted this action. Specifically, he alleged

that he is qualified in every respect to attend the

Davis Medical Scliopl; that petitioner, by virtue of

its maintenance and operation of the special admis

sion program, prevented him solely because of his

race from competing for all of the available places

at the medical school and thereby discriminated

against him in violation of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the United States Constitution, the Privileges

and Immunities Clause of the California Constitution

(Article I, Section 21), as well as the Civil Bights

Act of 1964 (42 U.S.O. § 2(100d); and finally, that

because of this unlawful discrimination, petitioner

denied him admission to the medical school. Bakke

prayed for the court to issue an Alternative Writ

of Mandate, an Order to Show Cause, and to

enter its judgment declaring that he is entitled to

admission to the medical school and that petitioner is

lawfully obligated to admit him (It. 1-5).

Petitioner denied the above allegations and cross-

complained for a declaration as to the legality of the

special admission program (It. 2-1-32).

On August 5, 1974 the trial court issped an Alter

native Writ of Mandate, ordering petitioner to admit

Bakke to the medical school or, alternatively, to

1G

appear ami show cause why the writ had not been

complied with; at the same time, tin: court issued an

Order to Show Cause, directing petitioner to appear

before the court and show cause why it should not he

enjoined pemhnte lite from refusing to admit Bakke

to the medical school (If. 3-1-38).

On September 27, 1971 the trial court conducted a

hearing on the Alternative Writ of Mandate and

Order to Show Cause. Counsel for both parties stipu

lated that the hearing would also constitute a full trial

of the case on the merits. Following oral argument,

the trial court ordered the case submitted fit. 282).

On November 25, 1974 the court tiled its Notice of

Intended Decision, declaring that the special admis

sion program is unlawful (Pet. App. D ; It. 280-308).

Doth parties prepared proposed Findings of Fact

and Conclusions of Law, as well as a proposed Judg

ment (It. J15-380). Following a further hearing on

the matter, held February 5, 1975, the trial court pro

ceeded to draft its own Findings and Conclusions

(It. 37G). On March 7, 1975 the trial court tiled an

Addendum to the Notice of Intended Decision (Pet.

App. Is; It. 381-381); the court also tiled its Findings,

Conclusions and Judgment (Pet. App. F, f j ; ft. 3SG-

391).

The trial court specifically found as a matter of

fnct Hinti

■ ■ • [ i special admissions program purports

to he open to ‘educationally or ceonumieallv dis

advantaged’ students. In the years in which

[Bakke] applied for admission, the medical

17

school received applications for the special ad

missions program from white students as well as

lrom members of minority races, but no white

students were admitted through this special pro

gram in either of said years. In fact no white

student has been admitted under this program

since its inception in. 19G9. In practice lhis°spe-

cial admissions program is open only to members

of minority races and members of the white race

aic barred from participation therein. In each of

the two yeors in which [Bakke] applied for ad

mission [petitioner] set a pre determined quota

ol 1 U to be admitted through the special admis

sions program. This special admissions program

discriminates in favor of members of minority

races and against members of the white race

[Bakke], and other applicants under the general

admissions program (Pet. App F n 1 1 4 ,,

115a; R. 387-388) ’ 1

Ihe ti ial court concluded and rendered judgment

that the special admission program at the Davis

Medical School violated Bakke’s rights under the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitu

tion, the Privileges and Immunities Clause of the Cali

fornia Constitution (Article I, Section 2 1 ) and the

Civil Bights Act of 1901 ( 1 2 U.S.O. $2000d) (Pet.

App. F, p. 117a; 17. 390, 391).

In paragraph 2 of the Judgment, the trial court

ruled that:

•

*‘ . . . | Bakke] is entitled to have his application

for admission lo the medical school considered

without regard lo his race or the race of any other

applicant, and [petitioner is] hereby restrained

18

ami enjoined from considering [Bakke’s] race or

Hie race of any other applicant in passing upon

his application for admission . . . (Pet. App. G,

p. 120a; It. 891)

The trial court also awarded Bakke his court costs,

hut refused to enjoin the operation of the special

admission program or to order Bale Ice’s admission to

the medical school (Id.).

Judgment was entered on March 7, 197f>. Balckc’s

counsel then requested that petitioner consider the re-

submission of Bakke’s application for admission to

the medical school pursuant to paragraph 2 of the

Judgment. Petitioner’s counsel responded that the

University would consider such an application as it

would “ an)* other such application coming in at this

late dale.” Petitioner’s counsel later added that the

medical school would only consider Bakke’s appli

cation “ in the normal course and without reference »

to Paragraph 2 pf life Judgment . . . .” (It. 108 111).

Proceedings on Appeal

On March 20, 1975 petitioner filed a Notice of

Appeal from those parts of the Judgment holding the

special admission program unlawful, requiring peti

tioner to judge Bakke’s application without regard

to his race or the race of any other person, and

awarding Bakke his costs of litigation (It. 298-399).

On April 18, t97o Bakke tiled a Notice of Cross Appeal

from that part of the Judgment denying his admission

to the medical school (17. -117-118). Finally, while this

case was pending in the California Court of Appeal

19

for the Third Appellate District, the Supreme Court

of California granted the University’s Petition for

Transfer and accepted the case for direct review (R

123-130; 13(i).

On September Ifi, 1976 the California Supreme

Court issued its opinion in (his case. The court, after

reviewing the facts of the case and the importance of

the constitutional questions presented for decision,"

concluded that where the state has imposed a classifi-

cation based upon race, “ . . . not only must the pur

pose of the classification serve a ‘compelling state

interest hut it must be demonstrated by rigid scrutiny

that there are no reasonable ways to achieve the

state’s goals by means which impose a lesser limita

tion on the rights of the group disadvantaged by the

classification. The burden in both respects is upon

the government.” (Pet. App. A, pp. 17a-18a; 18 Cal 3d

at 49).

The court assumed aryuenda that some of the

objectives of the special admission program “meet

the exacting standards required to uphold the validity

of a racial classification insofar as they establish a

compelling governmental interest.” (Pet: App. A, p.

23a; 18 Cal.3d at 53) The court, however, held that

the University had not satisfied its burden of justifv-

ing the racial means employed to achieve the goals of

the program.

. . [Ur]c are not convinced that the Uni

versity has met its burden of demonstrating that

the basic goals of the program cannot be sub-

•Tcl. App. A, pp. la-12a; 18 Cal.3d at 38 15.

20

si antially achieved by means less detrimental to

the rights of tlio majority." (Id.)

The court did not prevent the University from

formulating a special admission program based upon

other factors, such as disadvantage. Indeed, the

court's opinion encourages such a procedure:

“ In short, the standards for admission em

ployed by the University are not constitutionally

infirm except to the extent that they are utilized

in a racially discriminatory manner. Disadvan

taged applicants of all races must he eligible for

sympathetic consideration, and no applicant may

he rejected because of his race, in favor of

another who is less qualified, as measured by

standards applied without regard to race. We

reiterate . . . that we do not compel the Univer

sity to utilize only ‘the highest objective academic

credentials' as the criterion for admission." (Pet.

App. A, ji. 25a-2Ga; 18 Cal.3d at 55 (footnote

omitted)) ^ "

The court did not guarantee that alternate meas

ures would result in the enrollment of precisely the

same number of minority students as under the racial

quota (Pet. App. A, p. 2Gu-27n; 18 Cal.3d at 55-58).

The court's conclusion was that the University had not

established that the special admission program at issue

‘‘ is the least intrusive or even the most effective means

to achieve this goal." (Id. at 27a; 18 Cal.3d at 58)

The California Supreme Court also ruled that, inso

far as Bakke’s right to he admitted to the medical

school is concerned, the University hears the burden

of proving that Dakke would not have been admitted

21

had there been no racial quota (Pet. App. A, p. 38a;

lb Cal.3d at 83-81). The case was remanded to the

trial court for the purpose of determining, under the

proper allocation o f the burden of proof, whether

Ilakke would have been admitted to the medical school

absent this special admission program (Id .)."

The University filed a Petition for Rehearing,

which included a request for a stay, and it stipulated

that, given Bakke’s academic credentials and his high

“ benchmark" rating, the University could not sustain

its burden of proving that he would not have been

admitted had there been no racial quota (R. 487-488;

see generally Id. at 445-490).

The California Supreme Court denied the Petition

for Rehearing and denied the application for a stay

(Pet. App. B ; R. -191). In view of the University’s

stipulation, however, the court below modified its

initial opinion to direct that Bakke he admitted to the

medical school (Pet. App. C; R. 192-193; 18 Cal.3d

252b).“ * 11

“ Tlio court below was clearly correct on the Itunlcn of proof

issue. Once the plaintiff mates out a pinna facie case of raeiul

discrimination, the burden of justifying the discrimination, and of

explaining away the impact upon the plaintiff, shifts’ to the

defendant. As this Court noted in Pranks v. Uowinan Transpor-

lutiun to., Inc., -121 II.S. l l 7, 773, n. 32; 4<No reason appears

why (he victim rather than the perpetrator of the illegal act

should hear the burden of proof See u/so Vlcxundcr v

Louisiana. 105 IIS. C25 (1072).

111 lie 11 lit-f of the National Conference of lilack Lawyers as

Amiens Curiae argues that the decision below should he vacated

and remanded because of u recent amendment to the California

Constitution. On November 2, 1070, approximately a mouth ami

a half after the slate supreme court decided this case, the Cali

fornia Constitution was amended to provide, in part, that “ .

22

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The Fourteenth Amendment provides that no state

shall deprive any person within its jurisdiction of

the equal protection of the laws. In this ease, the

Court must decide whether Allan Bakke, a person

within the jurisdiction of the stale of California,

was denied equal protection when petitioner excluded

him from a state operated medical school solely be

cause of his race.

Petitioner Violated Allan Bakkc's Right to Equal Protection

Baklce was barred from the school ns a result of a

racial quota admission policy. The policy was im

posed by petitioner at the Davis Medical School, an

institution which had no prior history of racial dis

crimination. Pursuant to the quota policy, petitioner

set aside 1G places in the first year class for members

of certain racial antj.. ethnic groups, and thereby pre

vented Baklce, wfto was not a member of one of the

preferred groups, from competing for those places.

The persons selected by the quota were judged by a

separate admission committee which applied lower

standards than were applied to Bakke.

|N'Jd person shall he dehorn'd admission'to any department of the

University on account of race, relminn, ethnic heritage, or sex."

California Const.. Art. IX, §11, Solid, f. Amicus asserts that

"there, is now available to Respondent the possibility of stale

relief for the action he brought in slate court.” Brief of the

National Conference of Ulacl; l.awyers as Amiens Curiae at 117.

Amiens, however, ignores the. fact that Babko originally was

rejected by the medical school over three ycur.i before the

aiiu.li//iniHt ir/es mloptcil. In California, stale eonslilulional amend

ments are prospective in nature, unless a contrary intent clearly

appears. .SVc Hopkins v. Anderson. '_*|.S Cal. (i'J. lit; 87, J| |\:id

filiO, afil (lO'j't); Rollins v. Wright, ikl Cal. 305, JO I*. 58 (1802).

Thus, Amiens’ argument is not pertinent.

.23

The Supreme Court of California found that peti

tioner’s quota system discriminated against Bakke

because of his race and concluded that the quota vio

lated Bakkc’s constitutional right to equal protection.

Ibis conclusion is entirely consistent with the clear

mandate of the Fourteenth Amendment which, by its

own terms, applies to “any person".

i he previous decisions of this Court are authority

for the conclusion of the court below. On more titan

one occasion, the Court bas squarely held that the

light to equal protection is personal in nature. Be

cause slate imposed racial discrimination is constitu

tionally suspect, persons victimized by it have always

been afforded vigilant judicial protection; such

discrimination is unlawful unless the government

demonstrates that it is strictly necessary to promote

a compelling state interest. In this instance, the con

cept of a “ compelling” slate interest is not synonymous

with the recognition of an important social objective;

it connotes a degree of importance that is so pressing

as to override our traditional abhorrence of racial

discrimination. These were the principles that the

California Supreme Court applied in deciding this

case.

Petitioner, however, asserts that the judgment

below must he reversed because the protection granted

by the Fourteenth Amendment does not apply t0

any person” hut, instead, covers only ‘members of

certain “ discrete and insular” minority groups. Ac

cording lo petitioner, the instant preferential racial

quota is “ benign”, and therefore legal, because it is

designed to assist such minority groups, even tliomrh

l

24

it excludes Allan Balclcc from the medical school.

Petitioner claims that Balclcc is not entitled to judi

cial protection in this case because he is a member

of the so-called “majority".

Petitioner’s theory, if adopted, would fundamen

tally transform the right to equal protection. That

right no longer would be available lo every individual,

but would depend upon the race of the person assert

ing it. Advancement by way of individual achievement

would be replaced with the nil a that rights and bene

fits can be awarded according to ancestry. Such a

concept raises grave and troublesome questions of

policy. Who is to be preferred, and by what stand

ards are racial preferences to he judgedT*

The ultimate fact is that a racial preference is not

“benign”, but an evil heretofore recognized by the

American judicial system. The appropriate course

for this Court tpr follow in this case is lo reject peti

tioner’s quota and lo invoice the clear mandate of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

“ The instant quota grants it preference to Blacks. Cliicnnos,

Asians and American Indians. In DePunis v. Oilcgaani, S2 Wash.

2d 11, 17-18 & n.3, 507 F.2d l ISO, 1171 & n il (107.1), matted <n

moot, 110 US. 312 (l!l7lj, the special admission program favored

Black Americans, Chicnno Americans, American Indians and

Philippine Americans, hut did not prefer Asians. .S're also ilupnrt

v. Board of Higher Kducutinn. 120 F. Snpp. 10S7, JOBS £ n 31

(S.D.N.Y. 1070) (Blacks und llispanics; Asians uero not. favored

hccausc they were considered part of the “ majority” ! ; Flanagan v.

President and Directors of ticorgctown College, 117 F. Snpp. 377,

382 (D.D.U. 1!)70) jpreferred groups were Black Americans,

Native Americans, Aslan Americans and Spanish speaking Amer

icans!; Inge v. Town of Montclair, 72 N.l. :>, 13-1 1, 307 A.2d 833,

837 (11170) (Blacks were the onlv preferred group|; Alevv v.

Downslale Medical Center. 3!> X.V.Jd 320 330. 318 N.F.2.1 537,

511, 381 i\'.V.S.2d 82, 80 <1070) (Blacks, Puerto llicaus, Mexican

Americans and American Indians).

25

The California Supreme Court Correctly Decided this Case

In addressing the issues presented by this ease, the

California Supreme Court was not unmindful of the

ends sought to be achieved by petitioner. The court

below accepted ayyuciulo several of petitioner's goals,

hut rejected petitioner’s preferential racial quota as

an unconstitutional means to achieve those objectives.

The court below noted that the record was devoid of

any evidence that the instant quota was the least in

trusive mechanism available to petitioner, oy that pe

titioner had ever attempted any alternate measure.

Although the California Supreme Court disapproved

of petitioner’s quota, it left petitioner free to explore

new and innovative admission policies. The only limi

tation placed upon petitioner was one consistent with

the Constitution and the previous decisions of this

Court; the University may not prevent an applicant

such as Allan‘Balclcc from attending the Davis Medi

cal School solely because of his race.

The decision below is a practical and sensitive re

sponse lo a complex social issue. It is clearly correct

and should he affirmed by this Court.

26

ARGUMENT

INTRODUCTION

The question presented in this ease is whether peti

tioner’s special admission program, which excluded

Allan Bakke from the Davis Medical School solely be

cause of his race, denied Bakke the equal protection of

the laws. This question, appropriately described by

the court below as “ sensitive and complex”, i s of vital

concern. It presents a constitutional conlliet in which

this Court must decide whether tho right to equal pro

tection, granted by the Fourteenth Amendment to

“ any person” , does iruleedjextend to individuals such

as Allan Bakke or, instead, applies only to protect

certain racial and ethnic groups.

The issue is by no means new. It has attracted con

siderable attention,” evoked a wealth of comment,"

and has been the focus of previous litigation."

*“18 Cal.3d at ‘M i/

"Approximately 50 briefs amicus curiae have been filed herein.

“ Set, eg., Lavinsky, A Moment of Truth on Racially Based

Admissions, 3 Hastings Const. L. Q. 87!) (107G); Rcdisli, Pref

erential Law School Ailmissions and the I'r/ual Protection Clause:

-In Analysis of the Competing Arguments, 22 IJ.C.h.A. E. Rev.

313 (1071); Ely, The Constitutionality of Reverse Racial Dis

crimination, II i.'.C'bi. b. Rev. 723 (1071); Posner, The DcPunis

Case and the Constitutionality of Preferential Treatment of

Racial Minorities, 1071 Sup. Cl. Rev. 1. The discussion lias gone

beyond Ibe law reviews. I'.g., Sindtcr, Aur.uic.i in th k S eventies

at 2G2-320 (1077); f) Inzer, A itiiimative D isciiiuinatton (1075);

Cohen. Race and the Constitution, 220 Toe Nation 135 (107:7);

Wilhins, The Cuse Against Quotas, APE Diii.i.etin , March 1073,

al 1. In the words of Mr. dusliee Brennan: “ |P|cw constitulioual

questions in recent history have, stirred as much debate . . . . • '

DcPunis v. Odegaurd, IIG US. 312, 350 (1071) (dissentin;;

opinion).

"A similar claim was raised in the celebrated case of DcPunis

v. Odtgaard, 82 Wash. 2d 11, 507 l*.2d 11G0 (1073), and in

27

Needless to say, the question demands careful re

view j hut even cases involving broad constitutional

questions are grounded in a factual record and it is

there that the argument must begin.

I

THE SPECIAL ADMISSION PROGRAM VIOLATES ALLAN

DARKE'S RIGHT TO THE EQUAL PROTECTION OF THE

LAWS.

A. The Nature Of The Special Admission Projpram.

1. Thu program ia a racial quota.

There arc 100 places in the first year class at tho

Davis Medical School. Under normal circumstances,

Allan Bakke would he eligible to compete for all of

those places. In this case, however, petitioner has for

mally adopted a preferential racial quota and has set

aside 10 of the places for members of designated ra

cial and ethnic minority groups. In so doing, peti

tioner has prevented Bakke, solely because of his

race, from competing for the 10 quota places. Peti

tioner does not dispute' this fact and, under the

Alevy v. Downslulc Medical Center, 3!) N.Y.2d 32G, 318 N E 2d

537, 381 N.Y.S2d 82 (107G).

The subsequent history of the DcPunis cuse, ccrt. granted,

•111 U.S. 1038 (1873), vacated us moot, -116 U.S. 312 (1871), ia

well chronicled. See, e g., DcPunis Symposium, 75 Coluin. E.Kev.

•183 (1875).

The Alecy cn.se also suffered from procedural defects. In that

ease the court concluded that the plaintiff would not have been

admitted to the .school in question had there been no special

program. ‘*|T|hus,M said the New York Court of Appeals, “ the

petition should be dismissed." 38 N'.Y.2d at 338, 318 N.E.2d ut

517, 381 N.Y.S.2d ut 81.

There arc no such procedural problems in this case.

28

Imrdcn of proof rule announced liy the California

Supreme Court, concedes that it cannot refute Babko's

claim that he would have been admitted to the medi

cal school had there been no quota.3*

Because the quota reveals the true nature of the

special admission program, petitioner seeks to evade

this aspect of the case. Petitioner asserts that-there

is no formal allotment of places to specific groups,

hut rather an admission “ goal” which the school is

attempting to achieve." The record herein, however,

establishes beyond doubt that tlio special admission

program is in fact a racial quota. The Chairman of

the Admission Committee testified:

“ Q. [Mr. Colvin] It answers it, except that

I still have a curiosity, which you have perhaps

answered hut there was, correct me if I am wrong,

under the faculty resolution you would continue

to approve apd- process Task Force applications

until 16 had been accepted9

A. [Dr. Lowroy] That is correct, yes.

Q. In the year 1972-73, were any of the [pu

pils] admitted through the Task Force procedure

other than persons of minority ethnic identifi

cation ?

A. No.

’ “It. 115; Brief for Petitioner at 7-8. Tims llui California Su

preme Court modified ii.s opinion lo read, in part;

“ However, on up pool I he University lias conceded that it

cannot meet llm burden of proving Unit tlio special admission

program did uni result in Bahke’s exclusion. Therefore, he

is mlillrd to an order that ho he admitted lo die University.

. . . |T|he trial court is directed lo enter judgment order

ing Bahia1 lo he admitted.” 18 Cal .'Id at 25‘2b, 553 P 2d at

1172, 132 Cal. ft pit*, at 700.

’ •Brief for Petitioner at 11-17.

i

Q. Your answer would he the same for the cur

rent year?

A. That is correct.” (B. 168)

In administering its special admission program in

such a manner, petitioner has transcended any fair

interpretation of “ affirmative action", and has entered

a realm that is constitutionally forbidden. Although

Allan Bnkke was obviously qualified for the Davis

Medical School, petitioner’s quota arrangement ex

cluded him, because of his race alone, from 16 of the

100 places in the first year class. Petitioner’s quota

sought out persons, regardless of their lower qualifi

cations, who satisfied the school’s racial preference."

29

’ ’ Petitioner filled its quota hy seeking out persons with lower

qualifications than Bahhe, us revealed above in Uio churl and

accompanying discussion comparing Babko with regular udmiitces

und with those admitted through the speciul admission program.

Sice pp. 12-15, supra.

Several Amici claim that llakke cannot force the University

to rely on MOAT scores because the lest is ‘‘culturally biased”.

E.y., Brief for National Employment Law Project as Amiens

Curiae at If) 1C; Brief for I .aw .School Admission Council

as Amicus Curiae ut 10; Brief for IJ.C.L.A. Black Law Students

Association, ei ul.. as Amicus Curiae at 8 &. n.10; hid see Brief

of Association of Amcricun Law Schools us Amicus Curiae at

12-17.

llakke, however, has never contended that the school must use

the MOAT as a measure of ability. The California Supreme Court

certainly did not require its use. 18 Cal 3d at 55. Ii is petitioner

who has chosen to rely on the lest.

As lo thu claim of ‘‘cultural bias”, we note that Amici have

presented no evidentiary record in support of their position.

Both the trial court and the California Supreme Court had no

testimony or documentary evidence on the point.

Even former Juslieo Douglas, no great believer in so-called

aptitude tests, staled clearly in DePunis that:

“ The school can safely conclude that the applicant with

u score of 750 should lie admitted before one with u score

of 500. The problem is thut in many cases the choice

30

2. Petitioner's quota uproots individual constitutional freedoms and

replaces them with a destructive system of croup rights.

In attempting to justify the special admission pro

gram, petitioner lias posed several familiar arguments.

Petitioner’s initial thrust is that the program hero

challenged is the only way the University can achieve

its objectives. “ There is," says petitioner, “ . . . no

substitute for the use of race as a factor in admis

sions . . . Such a claim must he judged in terms

of the record. When that is done, there is hut one

conclusion; the record does not support petitioner.

There is simply no evideneo in this case that the

Davis Medical School has ever attempted any alter

native to the quota.

The school opened in 19GS. “ In short order the fac

ulty realized . . . that the existing admissions criteria

failed to allow access for any significant number of

minority students.’” !- To compensate, petitioner estab

lished a racial fpiota. Petitioner made no attempt to

convince the trial court that it could not meet its goals

will bo between G13 and G02 or 571 and 528." <J1C U.S. ut

32!) (dissenting opinion).

The situation here, with llalckc scoring in ibe 9Gth, 91th, 971b

and 72nd percentiles, and the special admillccs uierayino in the

Ifitli, 21th, 35th anil 33rd percentiles (1973) and in the 3 lib,

30th, 37tb and 18lh percentiles (1971), is far closer to llui

750-500 situation posed by former Justice Douglas than it is to

the GI3G02 situation, Dahlce is clearly better qualified. Paren-

Ibctieally, wo are bard pressed to understand bow a mathematics

or science question can be unfairly "culturally biased". .57c

I .inn. Vat Him ami the I‘evil id ion of tirades fa Law School 27

J. I .''gal Kdue. 293, 322-323 (1975); Hart £ Kraus, Major Research

L ports of the Law School . I (/mission Council, Apr. 1970; see. also

Sedb.-r, Racial Vre.fermcc, Reality amt The Constitution: liaU.e

v. R‘ (teals of the University of California, 17 Santa Clara L.Ucv.

329. 350 (1977); Brief of Association of American Law Schools

as Amicus Curiae, supra, at 12-17.

"Brief for Petitioner ut M.

"/(/. at 2.

31

through another, Jests discriminatory, program. The

plain tact is that petitioner has never tried any other

measure; nor does it show any inclination to do so.”

I ciitioncr s other rationalizations respecting the

merits of its program arc blind to the inevitable detri

ment suffered by society whenever racial preferences

exist. The mechanism of the quota has grave implica

tions; the evil transcends an individual case of favored

treatment, just us it goes beyond an individual case of

personal discrimination. It implies that rights to educa

tion, training and consequent career opportunities,

ideally open to all on an equal opportunity basis, will

now he officially categorized by group membership.

One would not become a doctor, lawyer, engineer or

accountant, hut a Ulack doctor, a Chicane lawyer,

an Asian engineer, or an American Indian accountant.

Admission to each profession or trade would he lim

ited according to the relative size of each ethnic group.

There is an insoluble question of policy. Is every

preferential racial ethnic quota lawful! I f so, then

presumably a 100% quota (or an exclusionary rule

close thereto) would be approved—and thus would

stand outside the arena of judicial scrutiny. If, on the

other hand, we arc to accept only those quotas which

are “ reasonably" dictated by the motives of their

authors, an opposite result follows: upon the adoption * I

nSee. Lavim.liy, A Moment of Truth on Racially llased Ad

missions. 3 I listings Const. L. Q. 879 (197G). According lo peli-

tinner, if llm judgment below is affirmed and the medical

sc bool cannot utilize a racial quota to govern its selection of

students, tin: school "predictably . . . would simply shut down

I it* I special admission I program |” rather than pursue alternate

measures that are leas discriminatory. Brief for rctilioner at I I.

32

of each quota, the process of judicial review would

begin anew, and the nation's courts would be called

upon endlessly to judge the eligibility of specific

minority groups, to apportion their shares of the

benefit in question, and to rationalize and adjudicate

the relative rights of each collective contestant. Upon

what valid basis could such questions be considered?

“ Once race is a starting point educators and

courts are immediately embroiled in competing

claims of different racial and ethnic groups that

would make difficult, manageable standards con

sistent with the Equal Protection Clause."

DeFunis v. Odegaunl, 41G U.S. 312, 333-331

(1974) (Douglas, J., dissenting).

There immediately arises the problem of numbers.

A quota in proportion to the national population? The

state population? The county or city population? If,

for example, the Japanese population o f the United

States were oife in 350, then would each professional

school class have only one member of that group (and

no more), given 350 places in the class? I f the stale

bad no significant Japanese population, then could no

Japanese qualify?"

’ ‘ Olio observer queries:

"What degree of minority representation is "rcnsoimbluJ'’ It

seems to depend on who is asked and on who makes (lie deci

sion, rather than on any consensus as to the proper base for

representation. . . . |I|n 1072, minority-student caucuses at

the Berkeley t,aw School (University of California) demanded,

in total, about half the entering places for minorities Each’

minority group pressed a different formula: blacks insisted

on a national proportional base, Chieanos on a California base

and Asian-Aioerieans on a local San Francisco Bay area base.

In sum, bow the base is determined in turn determines tbo

proportion of the scarce resource the group can claim, lienee

33

ihci-fi also n risen the question of numerous groups

not covered by petitioner's quota: Filipinos? Sa

moans? Ilawniians? Moroccans? Lebanese?" There

are also a wide variety of ethnic sub-groups contained

withip the so-called “ majority", who themselves have

been disadvantaged or discriminated against in the

past."

Should a preferential quota be extended beyond na

tional, ethnic, and racial groups to religious groups?

I f a religious group were deemed to be disadvantaged,

would its members have special rights? Conversely, if

it were deemed to bo “ not disadvantaged", would the

group be subject to legally approved discrimination?

For, given a limited number of opportunities, the

granting of a preference to include a favored class of

candidates surely implies a detriment— in the way of

exclusion—to individuals who are not so treated.

And who is a member of a racial group? Need one

be a “ full-blooded" American Indian to qualify? Or

is one grandparent sufficient? Or one great-grandpar-

Ihc process of deciding wlmt base lo use is typically highly

political and intensely disputed." Sindler, A mehicv in Tilt

S eventies at 300 (11)77).

" “ It is realistic lo expect many more [such groups), because

once this principle for the distribution of benefit uppears operative

each group is under some, pressure lo stake an early claim. The

pressure is greater when it cannot be known in what fraction(s)

Iho calm will lie eut, so that restraint by any group may result in

an ethnic apportionment on some continuum taking no account of

that group whatever." Cohen, Uticc and the Constitution "'0

Tiik Nation 135, 112 (11)75).

“ See Eavinsky, DeFunis o. Odiyuard: The "Fan Decision"

With a .Uissnyn, 75 Coluln E.Hev. 520, 527, n. 38; cf. llcycr v.

Nebraska, 202 II.S. 3!!G (1022). To paraphrase the .Supreme Court

of New Jersey, “ We are a |nationf of minorities." I.ige v. Town

of Montclair, 72 N.J. 5, 2-1, 3G7 A.2d 833, 813 (197G).

31

cal? Are wo to become involved in the testing of legal

lights according to blood lines?

The questions do not slop there. How extensive a

preference should he granted? In this ease it is six

teen places at the Davis Medical School. Why not

eight, or thirty-two, or sixty-four, or some other

number? What is the rational husis for any specific

percentage?

For how long is the preference to he continued?

And who shall decide when the preference is to he al

tered or concluded, and on what terms, and by what

authority?”

These questions illustrate the dilemmas inherent in

the quota system. While they might arise casc-by-case

in the context of heated litigation, their ultimate res

olution would lie beyond the prayer of any individual

claimant. We would be required to abandon the com

mitment to a society protective of individual achieve

ment and replace it with a system of rights based

upon racial or ethnic group membership.

The concept of individual freedom is based upon the

concept of individual achievement. The counter prin

ciple is the principle of ascribing rights to individuals

“ A peculiar aspect of petitioners program is lliat it lias not

been authorized by statute, local ordinance, executive order, or a

court of law. It lias been imposed, instead, by a group of medical

school faculty who decided on an oil hoc basis to apportion places

in the first year class according to race.

Petitioner contends that the faculty has “ independent discretion"

in administering the special admission ipmla Application for Slay

at It. The faculty, however, has set no time limit on the ipmla anil

during the eight years the program has been in operation, lues

made no change in the allotment of places. Indeed, the record

discloses no procedure for altering or ending this racial preference.

I

35

because of their ancestry, and that is tho quota princi

ple. It will he plainly destructive of a free society if

this Coui't, which heretofore has condemned, classifica

tions based on race, were to abandon that wisdom and

approve the quota system invoiced herein by peti

tioner. Indeed, as the California Supreme Court ob

served: “ No college admission policy in history has

been so thoroughly discredited. . . 18 Cal 3d at

G2.

3. There is a distinction between petitioner's quota and

the concept of “ailirmative action".

Several briefs amicus curiae urge the Court to vali

date petitioner’s program because it constitutes “ alfir-

mutive action”.” There is, however, a well-accepted

distinction between affirmative action and tho imposi

tion of a racial quota. In a broad sense, ailirmative ac

tion tdates to the positive effort undertaken by our

society (o integrate the races and provide all Amer

icans with equal opportunities. To this end, govern

ment and private industry have promoted a variety of

programs specially designed to identify, recruit, train

and give cxpciicuec to certain minority persons, A.

great many of these programs are governed by regula

tions promulgated pursuant to the Civil Rights Act of

l'Jfil.” As the Court noted in Griytjx v. Duke Power

0°., 101 U.S. ‘121 (1971), Die Act was intended to pro-

Brief for The Kntiomil Association of Minority Con-

tmelon, ct ul.. us Amicus Citrine at 13-27; Brief for Asian

American Bar Association of the Greater Bay Area us Amicus

Curiae at 21 23; Brief for the Bar Association of San Francisco

cl ul., as Amiens Curiae at JO 18; Brief for National Fund for

Minority Engineers as Amiens Curiae at 20-35.

1, i2 U S C. §§20()t)a-h; sec, e.ij., 15 C.F.lt. §§80.1 -80.13.

3G

hibit racial discrimination; it was not designed to

grant a racial preference to any person or group:

“ In short, the Act does not command that any

person he hired simply because he was formerly

the subject of discrimination, or because he is a

member of a minority group. Discriminatory

preference for any group, -minority or majority,

is precisely and only what Congress has pro

scribed. What is required by Congress is the i-e-

movnl of artificial, arbitrary, and unnecessary

barriers to employment when the barriers operate

invidiously to discriminate on the basis of racial

or other impermissible classification.

# tt #

. . Congress has not commanded that the less

qualified be preferred over the hotter qualified

simply because of minority origins. Par from dis

paraging job qualifications ns such, Congress has

made such qualifications the controlling factor, so