Correspondence from Judge Thompson to Counsel Re Discrepancies Between Plaintiffs' Exhibit 187 and Proposed Findings

Public Court Documents

March 21, 1986

5 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Correspondence from Judge Thompson to Counsel Re Discrepancies Between Plaintiffs' Exhibit 187 and Proposed Findings, 1986. f32868ec-b8d8-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0e1c875d-8afa-4d80-8e75-cbcbfccdeff0/correspondence-from-judge-thompson-to-counsel-re-discrepancies-between-plaintiffs-exhibit-187-and-proposed-findings. Accessed January 30, 2026.

Copied!

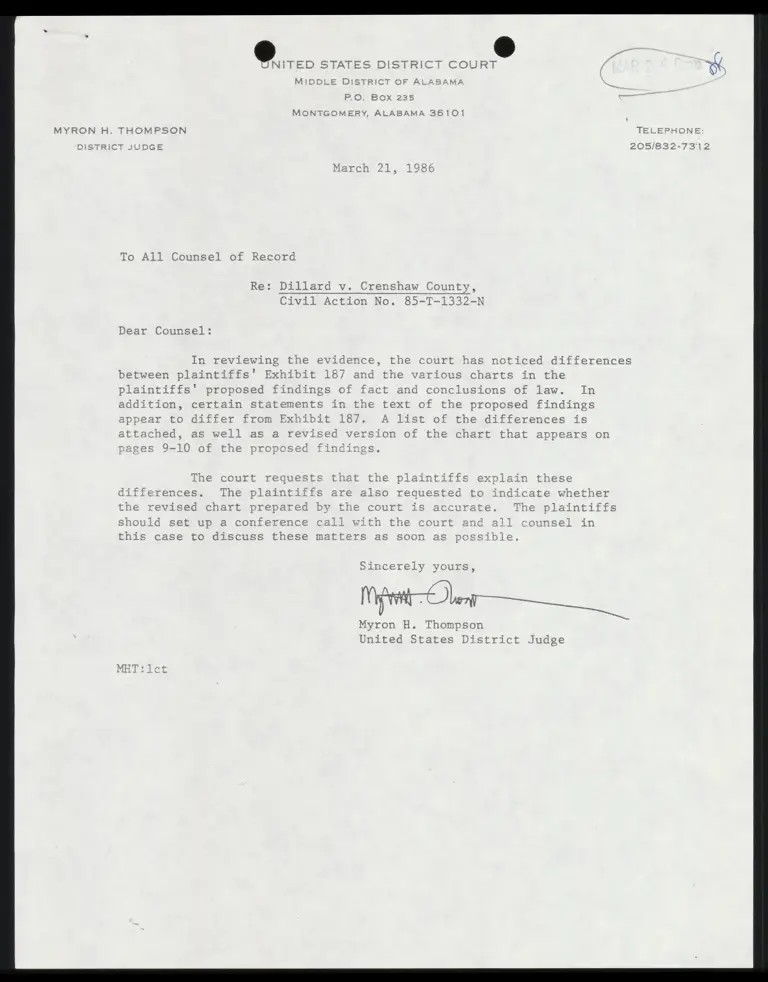

UNITED STATES DISTRIC OUR

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

PO. BOX 235

MONTGOMERY, ALABAMA 36101

. THOMPSON

DISTRICT JUDGE 205/832-7311

To All Counsel of Record

Re: Dillard v. Crenshaw County,

Civil Action No. 85-T-1332-N

Dear Counsel:

In reviewing the evid e, the court has noticed differences

etween plaintiffs' Exhibit 187 and the various charts in the

laintiffs' proposed findin a and conclusions of law. In

dition, certain stateme the text of the proposed findings

A list of the differences is

attached, as well as a revised version of the chart that appears on

e £4

=

T

r

t

Hs

0

0Q

J =

m1 be ~~ ~

The court reque these

13 er rw v 1 4 i” 1 differences. The plainti cate whether

the revised chart prepare plaintiffs

Myron H. Thompson

United States District Jud

11,

Discrepancies Between Plaintiffs' Exhibit 187

And Plaintiffs' Proposed Findings, Etc.

Chart p. 9-10 of Proposed Findings

A, Chart lists Marengo as having districts since 1867; Exhibit 187

shows that Marengo went to appointment system in 1869.

Chart lists Coffee as having districts since 1867; Exhibit 187

shows that Coffee first used districts in 1927.

Chart lists Cullman as having adopted at-large elections in 1895;

Exhibit 187 shows that Cullman did not move to at-large elections

until 1936.

Chart lists Marion as not having changed to at-large elections

prior to 1900; Exhibit 187 says it changed to at-large elections

in 1899,

Chart lists Covington as having districts since 1884 and changing

to at-large elections in 1894; Exhibit 187 shows that Covington

did not have districts until 1915.

Chart lists Pike as having districts in 1884; Exhibit 187 shows

that Pike first used districts in 1893.

Chart lists Chilton as having districts since 1884; Exhibit 187

shows that Chilton first used districts in 1959.

Chart lists Cherokee as having districts in 1884; Exhibit 187 shows

that Cherokee first used districts in 1947.

Chart lists Blount as having adopted at-large elections in 1895;

Exhibit 187 shows that it did not adopt at-large election until

1939,

Chart lists Crenshaw as having districts in 1884; Exhibit 187 shows

that Crenshaw has had at-large elections since 1884;

Chart lists Lamar as having districts in 1891 and adopting at-large

elections in 1894; Exhibit 187 shows that Lamar had districts in

in 1889 and did not adopt at-large elections until 1969.

Chart lists DeKalb as having districts in 1889; Exhibit 187 shows

that DeKalb adopted a dual system in 1887 and first moved to

districts in 1893.

Chart p. 10 of Proposed Findings

A, Chart lists Etowah as changing to at-large elections in 1891;

Exhibit 187 shows that this change occurred in 1890.

B. Chart lists Cullman as changing to at-large elections in 1895;

Exhibit 187 shows that this change occurred in 1936.

C. Chart lists Covington as changing from district to at-large

elections in 1894; Exhibit 187 shows that Covington had been

at-large since 1879 and never had districts until 1915.

D. Chart lists Chilton as changing to at-large elections in 1891 and

then moving back to districts in 1897; Exhibit 187 shows that

Chilton never had districts until 1959.

E. Chart lists Blount as changing to at-large elections in 1895;

Exhibit 187 shows that Blount had districts until 1939, when it

moved to a dual system.

F. Chart lists Pike as changing to at-large elections in 1891 and then

switching back to districts in 1893; Exhibit 187 shows that Pike

consistently had at-large elections until 1893, when it changed to

districts, and that it then moved back to at-large elections in

1894.

G. Chart does not indicate that Fayette moved back to districts;

Exhibits 187 shows that it returned to districts in 1896.

H. Lamar should not be on this chart; Exhibit 187 shows that it did

not adopt at-large elections until 1969.

I. It appears that Butler, Choctaw, DeKalb, Marion, and Shelby

counties should all be on this chart.

III. Chart p. 11 of Proposed Findings

A. Chart lists Marengo as changing to districts in 1919; Exhibit 187

shows that Marengo shifted to at-large elections from an appoint-

ment system in 1919.

B. Chart lists Sumter as changing to districts in 1927; Exhibit 187

shows that Sumter moved to at-large elections in 1927.

C. Chart lists Conecuh as changing to districts in 1919; Exhibit 187

shows that it changed in 1915.

D. Chart does not indicate that shortly after Madison changed to

districts in 1901, it adopted a gubernatorial appointment system

instead.

E. Houston, Barbour, and Shelby Counties appear to have changed to

some sort of mixed system, rather than to a pure district system

as the chart suggests.

F. Macon, Baldwin, and Elmore (to a mixed system) should be on this

chart, according to Exhibit 187.

“Dew

Iv.

VI.

Vil.

Chart p. 12 of Proposed Findings

A. Chart lists Franklin as having moved to a dual system in 1951;

Exhibit 187 seems to indicate that this shift occurred in 1949.

B. Chart lists Morgan as having moved to a dual system in 1939;

Exhibit 187 shows that it also had a dual system in 1919.

C. Chart lists Winston as having changed to a dual system in 1965;

Exhibit 187 seems to indicate that this shift occurred in 1959.

D. Blount appears to have adopted dual systems in 1939 and 1949 but

is not listed on this chart.

Chart p. 14 of Proposed Findings

A. Chart lists Houston as having changed to at-large elections in

1953; Exhibit 187 shows that it subsequently moved back to

districts (1957) and finally adopted some sort of mixed system

(1969).

B. Lamar shifted from districts to at-large elections in 1969 but is

not listed on this chart.

Statement p. 21-22 of Proposed Findings

At the bottom of page 21 of their proposed findings, plaintiffs state

that "By 1975, only six of Alabama's 67 counties were still using

single-member district elections for county commission." According to

Exhibit 187, however, 13 counties were using districts in 1975. These

13 counties are: Blount, Bullock, Clay, Cleburne, Coosa, Henry,

Houston, Lamar, Lauderdale, Marion, Monroe, Shelby, and Tallapoosa.

Revised Version of Chart on p. 9 of Proposed Findings

County Date (SMD) Date (A-L) Date (Other)

Winston 1866 1895

Marengo 1867 1869

(appointment)

Morgan 1866 1875

Dale 1867 1879

Geneva 1870 1895

County Date (SMD) Date (A-L) Date (Other)

Etowah 1879 1891

Cullman 1879 1936

Marion 1879 1899

Washington 1887 1894

Blount 1887 1939

Lamar 1889 1969

Pike 1893 1894

DeKalb 1893 1894

Bullock 1893 1894

Baldwin 1893 1894

Butler 1893 1894

Choctaw 1893 1894

Fayette 1893, 1896 1894

Pickens 1893 1894