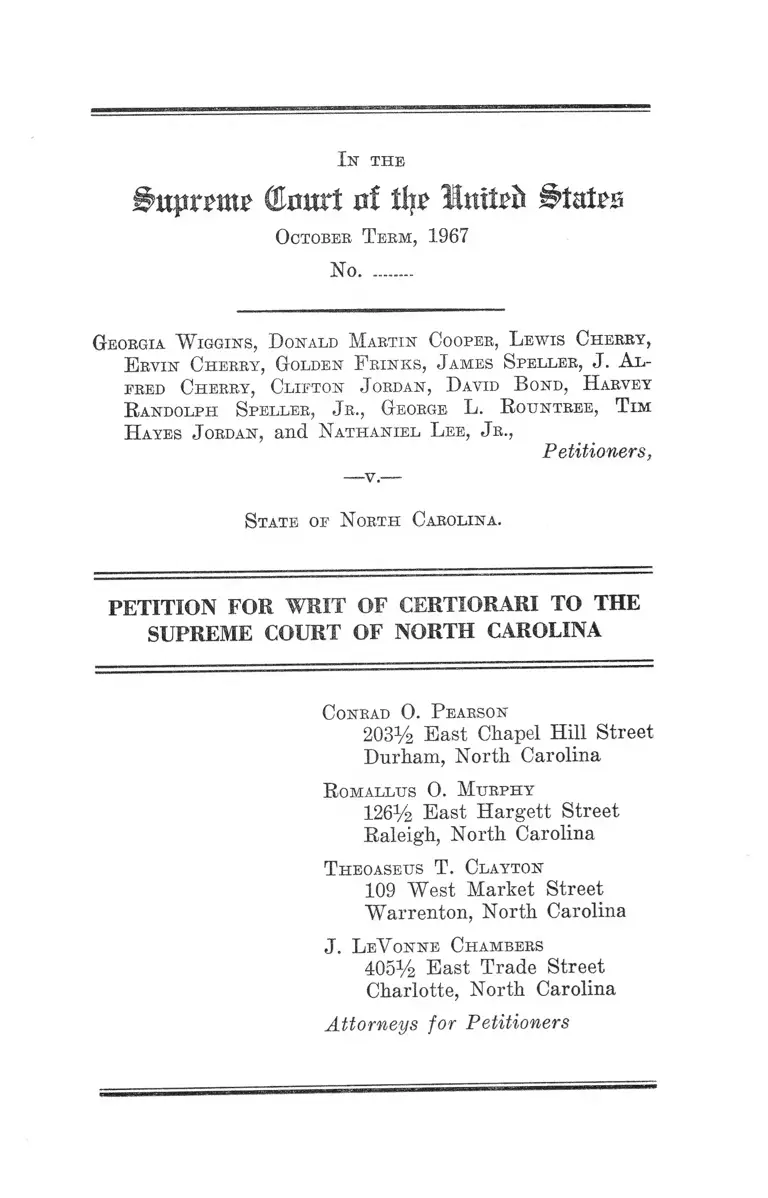

Wiggins v. State of North Carolina Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 2, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wiggins v. State of North Carolina Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1967. d8460c17-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0e2ae8c9-f69f-4ec4-8ef9-e0eaa5636289/wiggins-v-state-of-north-carolina-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

Uttpr^fttF (Emtrt ni tip

October T erm, 1967

No..........

Georgia W iggins, D onald Martin Cooper, L ewis Cherry,

E rvin Cherry, Golden F rinks, J ames Speller, J. A l

fred Cherry, Clifton J ordan, David B ond, H arvey

R andolph Speller, J r., George L. R ountree, T im

H ayes J ordan, and Nathaniel L ee, J r.,

Petitioners,

State of North Carolina.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA

Conrad 0 . P earson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

R omalltts O. Murphy

126% East Hargett Street

Raleigh, North Carolina

T heoaseus T. Clayton

109 West Market Street

Warrenton, North Carolina

J. L eV onne Chambers

405% East Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinion Below ................................ 1

Jurisdiction ....................................................................... 1

Question Presented .......................................................... 2

Statement .................................................. 2

How the Federal Question Was Raised and Decided

Below................................................. 4

R easons for Granting the AVrit—

The Decision of the North Carolina Supreme

Court in Holding That It AVas Not a Denial of

Due Process for the Petitioners to Be Convicted

by a Jury When the Sheriff AVho Selected It

Appeared as a Witness Conflicts With the Opinion

of This Court in Turner v. Louisiana .................. 5

Conclusion .............................................................................. 8

A ppendix—

Decision of the Supreme Court of North Carolina .. la

Table oe Cases

Irvin v. Dowd, 366 U.S. 717 — ..............— ................ 6

Mitchel v. Johnson, 250 F.Supp. 117 (M.D. Ala. 1966) 6

Turner v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 466 — ............................ 7

Statutes:

General Statutes of North Carolina, §14-273 .............. 3

In th e

tour! at tty MnlUb BUUb

October Teem, 1967

No..........

Georgia W iggins, D onald Martin Cooper, L ewis Cherry,

E rvin Cherry, Golden F rinks, J ames Speller, J. Al

fred Cherry, Clifton J ordan, David B ond, Harvey

R andolph Speller, Jr., George L. R ountree, T im

Hayes J ordan, and Nathaniel L ee, J r.,

Petitioners,

— v .—

State of North Carolina.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

entered in this case on December 13, 1967.

Opinion Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

is reported at 158 S.E.2d 37 and is set forth in the appen

dix, infra, pp. la-18a.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

was entered on December 13, 1967. The jurisdiction of

this Court is invoked pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1257(3), peti

tioners having asserted below and asserting here depriva

2

tion of rights secured by the Constitution and statutes of

the United States.

Question Presented

Were petitioners denied their rights under the due

process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment when testi

mony was given at their trial against them by the sheriff

of the county who had handpicked the panel from which

the jury that tried and convicted them was chosen?

Statement

On September 13, 1966, petitioner Golden Frinks drove

to the site of Southwestern High School with approxi

mately 20 other persons, most of whom were students (E.

92). Southwestern High School is a Negro high school

located in Bertie County, North Carolina (R. 91). The

petitioners wished to demonstrate in protest of certain

restrictive policies adopted by the school preventing their

wearing of “freedom buttons.” Upon their arrival at the

high school at about 8:30 a.m., they took up signs and

began peacefully picketing at the side of the road in

front of the high school. The evidence did not indicate

that at any time were they on school property, but rather

were in a ditch that divided the highway from the school.

The picketers were orderly and nonviolent at all times

and did not say anything during the course of their

picketing (E. 93).

The sheriff of Bertie County saw the cars with the dem

onstrators heading towards the high school and he fol

lowed them there. After speaking to the demonstrators,

the sheriff spoke to the principal and called two deputies

to come to the high school. When the deputies arrived

3

all 20 of the demonstrators demonstrating at that time

were arrested (R. 103).

Twelve of the demonstrators were charged with violating

General Statutes of North Carolina, §14-273, which makes

it a misdemeanor to “wilfully interrupt or disturb any pub

lic or private school . . . either within or without the

place where such . . . school is held.” Petitioner, Golden

Frinks, was charged with aiding and abetting the others

with violating the statute (R. 10). All 13 petitioners were

tried together and their convictions wrere affirmed in a

single opinion of the North Carolina Supreme Court (158

S.E.2d 37, App. la ).1

Prior to trial the petitioners challenged the composition

of the jury panels in Bertie County on the grounds that

Negroes had been systematically excluded therefrom. A f

ter a hearing on that issue, the trial judge agreed that

such systematic exclusion had taken place (R. 31-33). How

ever, instead of ordering a recomposition of the entire

jury list and panels, he simply ordered the sheriff to pick

50 citizens known to him as persons of good character

to form a new panel for the purpose of trying petitioners’

case (R. 32-33). The sheriff testified that he used the tele

phone directory and his own memory to select names that

“I knew- were good, outstanding citizens of Bertie County”

(R. 90). From the 50 persons, a jury of six whites and

six Negroes were picked (R. 33).

At trial the sheriff was one of the three witnesses who

testified for the prosecution. The other two witnesses were

the principal of the high school and one of the teachers

there, who, of course, were involved in the dispute with

petitioners over conditions and practices at the school.

Thus, the sheriff was the only wholly disinterested wit

1 The eases o f the rest o f the demonstrators were evidently handled

by the local juvenile court and are not involved in the present petition.

4

ness that testified before the jury. His testimony was

particularly important with regard to the conviction of

petitioner Frinks for aiding and abetting the other defen

dants. The sheriff testified that, before the picketing be

gan, he had informed Frinks that there was a statute that

prohibited disturbing a public school, and that Frinks had

respondent to the effect that he didn’t care (R. 102, 105).

The jury returned a verdict of guilty and the defen

dants were fined from $10.00 to $50.00 and ordered to

pay costs. Petitioner Golden Frinks was sentenced to 60

days in the county jail (R. 119-20). The convictions were

appealed to the Supreme Court of North Carolina, which

affirmed them on December 13, 1967. A stay of execution

of the judgment was granted pending the filing and dis

position of this petition.

How the Federal Question Was

Raised and Decided Below

Petitioners challenged the composition of the jury, the

process of its selection and the sheriff’s testifying to a

jury which he had selected himself. Petitioners objected

to the composition of the jury by a motion to challenge

the jury array (R. 31). After the court had ordered the

dismissal of the original panel and ordered the sheriff to

select 50 jurors himself, a further objection to this pro

cedure was made and overruled by the trial court (R. 33,

87-90). The issue of the denial of due process under the

federal Constitution because the sheriff was a key prose

cution witness before a jury which he himself had selected

was raised by an assignment of error on appeal (R. 135-

37),2 was argued to the Supreme Court of North Carolina,

and was rejected by it (App. 13a; 158 S.E.2d at 45).

2 The text of the assignment of error is as follows:

This A ssignment of E rror is addressed, (1) to the total denial

by the Trial Court o f defendants’ rights to be tried by a jury sys

5

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

The Decision o f the North Carolina Supreme Court

in Holding That It Was Not a Denial o f Due Process

for the Petitioners to Be Convicted by a Jury When

the Sheriff Who Selected It Appeared as a Witness Con

flicts With the Opinion o f This Court in Turner v,

Louisiana.

In the trial court below petitioners challenged the jury

array on the ground that Negroes had been systematically

excluded from it, in violation of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution. The trial court dismissed the

challenged array and rather than selecting a new panel

through the jury commissioners and court clerks, ordered

the sheriff to personally select 50 persons that in his opin

ion were of good character to be jurors.

tem and by a jury selection process which is completely free of

racial discrimination; (2) to the obviously discriminatory “ cure”

applied by the Trial Court to the adjudged racial discrimination in

the Bertie County jury system, under which “ cure” defendants are

penalized in the jury selection process, solely because of their race,

by being given an abbreviated, improvised and dubious jury panel

o f all talesmen jurors; (3) to the obviously discriminatory “ cure”

applied by the Trial Court to the adjudged racial discrimination by

the Bertie County Commissioner in jury selection, under which “ cure”

defendants are further penalized solely because of their race, by the

Court’s leaving the selection o f their panel to the subjective and

uncontrolled will and discretion of an adversely interested major

witness in their case, to wit, the Sheriff of Bertie County; (4) to the

unconstitutional application of North Carolina General Statutes 9-11

by the Trial Court, under which application, North Carolina General

Statutes 9-11 is applied as a “ cure” to the adjudged unconstitutional

application and administration of North Carolina General Statutes

9-1, et seq., to which the former is an inseverable adjunct. The

rights above-mentioned are all protected by Article I, Sections 13, 17

and 38, o f the Constitution o f North Carolina and by the Due Process

and Equal Protection Clauses o f the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Federal Constitution. The errors above referred to are pointed up

by E xceptions Nos. 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 42 (R. pp. 87, 88, 89, 90, 120).

6

The trial court thus gave limited relief to petitioners’

claims under the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment3 while leaving their related due process rights

to “a fair trial by a panel of impartial, ‘indifferent’ jurors,”

Irvin v. Dowd, 366 U.S. 717, 722, in the hands of the chief

prosecution witness.

The sheriff testified that he selected 50 persons based

on his acquaintance with them and by going through the

telephone directory. Out of this handpicked group of 50

persons, 12 were selected to sit on the jury that tried

and convicted petitioners. At trial the sheriff was one of

three witnesses for the State. Indeed, he was the only ap

parently disinterested witness since the other two, the

principal and a teacher at the high school, were involved

in the dispute with the petitioners.

Moreover, the sheriff’s testimony was of particular im

portance in showing intent on the part of petitioner Frinks

to aid and abet in violating the statute herein involved.

The sheriff stated that he had informed Frinks of the

statute and Frinks had responded that he did not care

that such a prohibition existed (R. 102). It must be as

sumed that the testimony of the sheriff had great weight

in the jurors arriving at a verdict of guilty.

3 It is important to note that in a rural county where the population

is 60% Negro (R. 32), and where the trial court found that Negroes

had been systematically excluded from the jury array, that no reform

of the selection system resulted. While petitioners, as defendants in a

criminal action, might not have standing, as such, to seek structural re

form, ef., Mitchel v. Johnson, 250 F. Supp. 117 (M.D. Ala. 1966), we

contend that the resulting process of selection should be given careful

scrutiny by this Court. The reasonable inference o f discrimination re

sulting from the finding of Negro exclusion is not rectified by the kind

o f procedure complained of herein. For this Court to require that the

procedure be reformed where it has been determined that Negroes have

been systematically excluded from the juries would not only ensure a

fair jury for the defendants here, but would also give some assurance

that Negroes will no longer be so excluded in that jurisdiction.

7

However, the fact that the sheriff had picked the jurors

from his personal acquaintance with them could only serve

to increase his influence over them beyond that enjoyed

by an ordinary witness. Thus, this ease is closely analogous

to Turner v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 466. In that case the two

principal witnesses for the prosecution were deputy sher

iffs. The jurors were sequestered in accordance with Lou

isiana law during the trial and were placed in charge of

the sheriff. As this Court said, “in practice, this meant

that the jurors were continuously in the company of [the]

deputy sheriffs,” 379 U.S. at 468. This Court reversed the

convictions on the ground that the right to a jury trial

guarantees to the criminally accused “ a fair trial by a

panel of impartial, ‘indifferent’ jurors,” 379 U.S. at 471.

An impartial jury could not be assured where witnesses

for the prosecution have acquired an influence over them

through their official capacity.

Similarly here the jurors could not but have been influ

enced inordinately by the testimony of the very man who

had selected them to serve as jurors. Due process demands

no less than that defendants in a criminal trial, if the

state chooses to try them before a jury, be put on an

equal basis with the prosecution and that the jirry be

free of any possible bias towards the prosecution because

of a close relationship between them and witnesses of

the prosecution who are acting in their official capacity.

Petitioners urge that certiorari should be granted to re

solve the important question of whether a procedure such

as adopted here can stand consistent with the rule in

Turner.

8

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons, the petition for writ of certiorari

should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Conrad O. P earson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

R omallus 0 . Murphy

126% East Hargett Street

Raleigh, North Carolina

T heoaseus T. Clayton

109 West Market Street

Warrenton, North Carolina

J. L eV onne Chambers

405% East Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioners

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

NORTH CAROLINA SUPREME COURT

P all T eem 1967

No. 174—Bertie

Decision of the Supreme Court o f North Carolina

State of North Carolina

v.

Georgia W iggins, D onald Martin Cooper, L ewis Cherry,

E rvin Cherry, Golden F rinks, James Speller, J. A l

fred Cherry, Clifton J ordan, David B ond, H arvey

R andolph Speller, J r., George L. R ountree, T im H ayes

J ordan, Nathaniel L ee, J r.

Appeal by defendants from Fountain, J., at the 6 Febru

ary 1967 Session of Bertie.

The defendants were tried on separate warrants, which

were consolidated for trial. The warrants, as to all of the

defendants except Frinks, charged that on or about 13

September 1966 the defendant named therein “did know

ingly, wilfully and unlawfully interrupt and disturb the

Southwestern High School, a public school in Bertie County,

N. C., by picketing in front of the Southwestern High

School,” which picketing interfered with classes at the

school in violation of G.S. 14-273. The warrant against

Frinks charged him with aiding and abetting in such inter

ruption and disturbance of the school.

Prior to pleading to the warrants, the defendants moved

to quash each warrant on the ground that it shows upon its

2a

face that the defendant named therein was “in the peaceful

and orderly exercise of First Amendment rights of picket

ing and * * * of freedom of speech and protest,” and on the

further ground that G.S. 14-273 is unconstitutional, as ap

plied to the alleged conduct of the defendants, “by reason

of the obvious collision between the statute and the rights

of peacefully picketing.” The motion to quash was over

ruled as to each defendant.

Prior to pleading to the warrants, the defendants chal

lenged the array of jurors summoned for that session of

the superior court, the ground of the challenge being that

Negroes had been systematically excluded from the jury

list, and so from the jury box, from which the panel in

question was drawn. All of the defendants are Negroes.

The court conducted a hearing upon this motion, at which

numerous witnesses, including county officials and others,

were called by the defendants and examined. The presiding

judge thereupon found as a fact that “there has been a dis

proportionate number of white persons to that of Negro

persons whose names have been put in the jury box for the

drawing of jurors” as compared with the proportion of

Negro residents of the county to the total population, and

as compared with the proportion of Negroes listing prop

erty for taxes with the total number of persons so doing,

which disproportion he found to have been without any

intention to discriminate on account of race in the selection

of names to be placed in the jury box. The trial judge then

ordered that “ to assure each defendant that he and she

will be tried by jurors who are selected without regard to

race,” no juror will be called into the box for the trial of

these cases from the regular panel, but the sheriff would

summon “ fifty persons who are qualified to serve as jurors

* * * without regard to race.”

Decision of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

3a

The sheriff so summoned a special venire and from it the

trial jury was selected, six of its members being Negroes

and six being white persons.

Thereupon, prior to entering their pleas to the warrants,

the defendants objected to the special venire on the ground

that they were entitled to be tried by jurors “ selected by the

Constitutional system that is provided by the State.” The

sheriff was called as a witness and examined by the defend

ants concerning the method used by him in selecting those

comprising the special venire. The objection of the defend

ants to the special venire was overruled.

Thereupon, the defendants entered pleas of not guilty.

The jury returned a verdict of guilty as to each defendant.

The defendants, other than Frinks, were fined in varying

amounts. Frinks was sentenced to confinement in the county

jail for a term of 60 days. Each defendant appealed.

The State called as witnesses the principal of Southwest

ern High School, the teacher of the class in bricklaying at

the school, and the sheriff of the county. The defendants

offered no evidence.

The school principal testified that on the date named in

the several warrants the school was in session. It is located

on Highway 308, some five miles from the Town of Wind

sor. Only two residences are in the vicinity of the school,

the nearest being 100 yards away. The school building sits

back from the highway approximately 500 feet. At the time

of the alleged offense, the class in brick masonry was in

progress, under the direction of its teacher, on the school

grounds approximately 10 to 25 feet from the highway, the

students in the class being engaged in the erection of cer

tain brick structures as part of their class work. Other

pupils were inside the building where classes were in prog

ress. Frinks drove up to a point on the highway in front

of the school, “unloaded some children and took out some

Decision of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

4a

signs with various wording * * # and gave each one a sign

and they began to picket” ; i.e., to walk up and down the

ditch separating the highway from the school campus. The

school principal thereupon asked the sheriff, who was pres

ent, “ if he could get those people away.” Each of the de

fendants, other than Frinks, participated in the marching.

(The principal did not name Lewis Cherry among the

marchers, hut he was so named by the sheriff.) This conduct

by the defendants resulted in the pupils within the school

building “looking and carrying on” to such an extent that

the principal had “to get them back to their classes and

walk up and down the hall * * * trying to keep them in class.”

When the principal went back into the building, he found

pupils in the classes in progress in rooms facing the high

way “looking out of the windows at what was going on,”

and pupils from classes in progress on the other side of

the building corridor “ running to the side that looked out

on the marchers to see what was happening.” These stu

dents “were talking among themselves * * * saying what

they had seen.” The brick masonry class, consisting of 15

or 16 students, was taken from its work on the school

grounds back to the “ shop” before the completion of its

fully allotted class period. There was no problem in keep

ing order in the school except during the time “when these

defendants were out in front” of the school.

The teacher of the class in bricklaying testified that he

was conducting his class on the school grounds, the project

in hand being the construction of some brick columns, some

ten feet from the ditch in or along which the defendants,

other than Frinks, marched. There were 15 students in the

class. The marchers appeared some ten minutes after the

class started. They arrived in an automobile, got out of it

in front of the school grounds, passed out some signs and

Decision of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

5a

then marched along the ditch. The teacher tried to keep his

students busy but the marchers took their attention, and

some of the students stopped what they were doing and

watched the marchers. The teacher talked to his students

but could not maintain control of the class, so he gathered

up the tools and took the class back into the building two

hours before they were scheduled to complete their assign

ment on the grounds. The marchers were not singing,

clapping their hands, or doing anything except marching.

The sheriff testified that he had been at the school when

it opened for the day’s work, but after the school opened,

he left in his automobile. Approximately four miles away

he met Frinks with four or five other people in his car. The

sheriff at once returned to the school. Upon his arrival

there, he found Frinks’ car parked on the shoulder of the

highway, with several people standing around it, and Frinks

handing out signs “to the students.” (Apparently the

marchers were students enrolled in the school but not in

attendance upon classes that day.) The sheriff asked Frinks

if he was aware of the statute of North Carolina forbidding

the interruption of a public school. Frinks replied, “I don’t

care anything about what is in the Statute Books.” (The

court instructed the jury that the testimony of the sheriff

concerning the remarks of Frinks was evidence as to

Frinks only and not as to any other defendant.) The de

fendants, other than Frinks, together with some eight

others who were “juveniles,” then lined up and started

marching. They were arrested after they had marched up

and down two or three times. The sheriff observed several

students standing and watching the demonstration and the

marching. He also observed the teacher of the bricklaying

class carry his class back into the “ shop.” After passing

out the signs to the marchers and lining up the marchers,

Decision of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

6a

“Frinks got in Ms car and drove off, headed toward Wind

sor.” Approximately 20 minutes elapsed from the arrival

of the defendants at the site of the marching to the arrest

of the marchers. Frinks was arrested two days later.

The various signs carried by the marchers read as

follows:

“ God set us free why should we be here as slaves.”

“A change is going to come.”

“Freedom, Yeah, Yeah, Yeah.”

“We want to talk but you make us talk and we’ll talk

and you will walk.”

“We want to be taught a free education.”

“Let us be free and taught free.”

“Searching, searching for a free Southwestern.”

“Southwestern will overcome some day.”

“What about our buttons, Mr. Singleton ? Freedom!”

“Freedom in ’67.”

“We want to grow up free!”

A ttorney General B ruton and Deputy A ttorney

General M oody for the State.

Clayton & B allance, J . L eV onne Chambers and

M itchell & Murphy for defendant appellants.

L a k e , J. The pertinent provisions of G.S. 14-273 are:

“If any person shall wilfully interrupt or disturb

any public or private school * * # either within or with

out the place where such * * * school is held * * * he

shall be guilty of a misdemeanor, and shall, upon con

Decision of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

7a

viction, be fined or imprisoned or both in the discretion

of the court.”

The defendants argue in their brief that this statute is

void because its prohibitions are uncertain, vague or in

definite, under the rule applied by this Court in State v.

Furio, 267 NC 353, 148 SE 2d 275. They argue in their

brief that the statute contains no definition of “ interrupt”

or of “ disturb” and, consequently, men of common intelli

gence must necessarily guess at its meaning and thus be

left in doubt as to what conduct is prohibited. It is difficult

to believe that the defendants are as mystified as to the

meaning of these ordinary English words as to they profess

to be in their brief. Clearly, they have grossly underesti

mated the powers of comprehension possessed by “men of

common intelligence.” Nevertheless, we treat this conten

tion as having been seriously made.

It is elementary that in the construction of a statute

words are to be given their plain and ordinary meaning

unless the context, or the history of the statute, requires

otherwise. Cab Co. v. Charlotte, 234 NC 572, 68 SE 2d 433;

In re Nissen’s Estate, 345 F 2d 230. While the meaning of

“interrupt” and of “disturb” is perhaps more easily under

stood than defined with precision, resort to Webster’s Dic

tionary reveals that “interrupt” means “to break the uni

formity or continuitj ̂ o f ; to break in upon an action,” and

“disturb” means “to throw into disorder.” For those who

are unhappy without citation to authorities of the type

customarily cited in judicial opinions, we refer to Black’s

Law Dictionary and to Watkins v. Manufacturing Co., 131

NC 536, 42 SE 983, where this Court said that an allega

tion in a complaint for personal injury that the plaintiff

had been “disturbed in body” must be understood to mean

Decision of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

8a

that “her body was thrown into a state of disorder, and

thereby injured.”

In Kovacs v. Cooper, 336 US 77, 69 S. Ct. 448, 93 L. Ed.

513, the Supreme Court of the United States, speaking

through Mr. Justice Reed, in sustaining a conviction in the

courts of the State of New Jersey for violation of an ordi

nance forbidding the use of sound trucks emitting “loud

and raucous” sound, said:

“ The contention that the section is so vague, obscure

and indefinite as to be unenforceable merits only a pass

ing reference. This objection centers around the use

of the words ‘loud and raucous.’ While these are ab

stract words, they have through daily use acquired a

content that conveys to any interested person a suf

ficiently accurate concept of what is forbidden.”

When the words “interrupt” and “disturb” are used in

conjunction with the word “ school,” they mean to a person

of ordinary intelligence a substantial interference with, dis

ruption of and confusion of the operation of the school in

its program of instruction and training of students there

enrolled. We found no difficulty in applying this statute,

in accordance with this construction, to the activities of a

group of white defendants in State v. Guthrie, 265 NC 659,

144 SE 2d 891. Obviously, the statute applies in the same

manner regardless of the race of the defendant. In State

v. Ramsay, 78 NC 448, in affirming a conviction for the

similar offense of disturbing public worship, this Court

speaking through Smith, C.J., said:

“It is not open to dispute whether the acts of the

defendant were a disturbance in the sense that sub

jects him to a criminal prosecution, and that the jury

was warranted in so finding, when they had the ad

Decision of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

9a

mitted effect of breaking up the congregation and

frustrating altogether the purposes for which it had

convened.”

Giving the words of G.S. 14-273 their plain and ordinary

meaning, it is apparent that the elements of the offense

punishable under this statute are: (1) Some act or course

of conduct by the defendant, within or without the school;

(2) an actual, material interference with, frustration of or

confusion in, part or all of the program of a public or pri

vate school for the instruction or training of students en

rolled therein and in attendance thereon, resulting from

such act or conduct; and (3) the purpose or intent on the

part of the defendant that his act or conduct have that ef

fect. One, who has reached the age of responsibility for his

acts and who is not shown to be under disability of mind,

is presumed to intend the natural and normal consequences

of his acts and conduct. State v. Ramsay, supra. Nothing

else appearing, the defendant’s motive for doing wilfully

an act forbidden by statute is no defense to the charge of

violation of such statute. Cox v. Louisiana, 379 US 559, 85

S. Ct. 476, 13 L. Ed. 2d 487 ; Commonwealth v. Anderson,

272 Mass. 100, 172 NE 114, 69 ALE 1097; 21 A m Jur 2d,

Criminal Law, § 85.

Each warrant in the present case charges the defendant

named therein in plain and precise language with each ele

ment of this statutory offense at the specified time and place

by the specified conduct of picketing in front of the school,

which picketing interfered with classes at the school. Each

warrant is sufficiently specific to protect the defendant

named therein from being placed again in jeopardy for the

same offense. Consequently, the motion to quash the war

rants was properly overruled unless the defendants had,

Decision of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

10a

as they contend they did have, a lawful right to engage in

the specified conduct, notwithstanding the statute.

The uncontradicted evidence of the State, if true, as it

must be deemed to be in passing upon a motion for judg

ment of non-suit, is sufficient to show that the defendants,

other than Frinks, intentionally paraded back and forth in

front of the specified public school building and grounds in

the immediate vicinity of a class then in progress on the

school grounds. The evidence likewise shows that Frinks in

tentionally aided, abetted, directed and counseled the march

ing. The marchers carried placards or signs. These signs

were utterly meaningless except on the assumption that

they related to some controversy between the defendants

and the administration of the school, specifically Principal

Singleton. Presumably, they were deemed by the defend

ants sufficient to convey some idea to students or teachers

in the school. The site was the edge of a rural road run

ning in front of the school grounds, with only two residences

in the vicinity. There is nothing to indicate that the

marchers intended or desired to communicate any idea

whatsoever to travelers along the highway, or to any per

son other than students and teachers in the Southwestern

High School. As a direct result of their activities, the work

of the class in bricklaying was terminated because the

teacher could not retain the attention of his students, and

disorder was created in the classrooms and hallways of the

school building itself. Consequently, the motion for non

suit was properly overruled unless the defendants had, as

they contend, the lawful right so to interrupt and disturb

this public school, notwithstanding the provisions of the

statute.

The contention of the defendants that the court com

mitted error in admitting evidence as to the conduct of

Decision of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

11a

the students in the bricklaying class and in the school

building in response to the marching of the defendants

must be deemed frivolous. An essential element of the

offense charged in the warrants is the actual interruption

and disturbance of the program of the school. Obviously,

this can be shown only by evidence of the effect of the

defendants’ conduct upon the activities of the teachers and

students of the school. The witnesses, who testified con

cerning this, related their own observations of what hap

pened upon the school grounds and within the school build

ing while the conduct of the defendants was in progress,

as contrasted with the good order which prevailed prior to

the commencement of the marching and after the departure

of the defendants. Such evidence was clearly material and

competent.

When the defendants challenged the array of regular

jurors summoned for the term, on the ground of unconsti

tutional discrimination against members of their race in

the selection of names to go into the jury box from which

the panel was drawn, the trial judge conducted a hearing

and heard all of their evidence upon that matter. Upon this

evidence, he found that a disproportionately small number

of names of Negroes had been included in the box. He

theerupon ordered that no member of the regular jury

panel be called as a juror for the trial of these cases and

directed the sheriff to summon a special venire of fifty

persons “without regard to race.” This was done and from

that panel the jury which tried and convicted the defend

ants was chosen, six of those jurors being Negroes. The

contention of the defendants that it was error to order

such special venire is without merit. The procedure so

followed by the trial judge is expressly authorized by G.S.

9-11, and the only contention of the defendants that tales

Decision of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

12a

jurors can be called only to supplement an insufficient num

ber of regular jurors is refuted by the very case they cite

in their own brief, State v. Manship, 174 NC 798, 94 SE 2,

in which this Court, speaking through Clark, C.J., said:

“It has never been controverted that the judge in his

discretion has the power to excuse any juror and to

discharge any jury that he thinks proper. It seems

that in this case the regular jury had been discharged

under the impression that the business of the court

was over. This case coming up, the defendant asked

for a continuance. But, there being no other ground

suggested therefor, the court, in the exercise of its

discretion, directed tales jurors to be summoned, un

der the above statute [G.S. 9-11], which was passed

for this very purpose, that ‘there may not be a defect

of jurors.’ There was long a practice, under the for

mer statute, that the judge should reserve one juror

of the regular panel to ‘build to,’ based upon the tech

nical idea that the tales jurors should be other jurors,

as if they would not be ‘other’ jurors even if that one

juror had also been discharged. It was no prejudice

to this defendant that one regular juror was not re

tained. Twelve jurors, freeholders, to whom he en

tered no exception, sat upon his case, and he was duly

convicted.”

There is nothing in this record to indicate that any juror

who sat upon the case and convicted the defendants was

challenged by any of the defendants. The record does show

that the defendant Wiggins, having exhausted her per

emptory challenges, attempted to challeng peremptorily a

seventh juror and her challenge to that juror was disal

lowed. However the record shows that the juror so ehal-

Decision of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

lenged by her was removed from the jury upon the

peremptory challenge of another defendant.

The record does not indicate that any other case was

tried at this term of court or that any regular juror, or

any other juror drawn from the jury box, participated in

any way whatever in any proceeding before the court at

this term or at any other term. The objection of these

defendants to trial by jurors drawn from the jury box

having* been sustained, and they having been tried by a

jury summoned and selected pursuant to the statute, and

without discrimination on account of race or otherwise,

the defendants may not attack the judgment entered

against them because of a defect in the composition of the

jury box from which the regular panel was drawn.

We have no information as to what action has or has

not been taken with reference to the jury box since the

trial of these cases, and that question is not now before us.

The special venire was not rendered invalid by reason

of the fact that the sheriff who summoned it, pursuant to

the orders of the court, was a witness for the State in

these cases. State v. Yoes, 271 NC 616, 157 SE 2d 386;

Noonan v. State, 117 Neb. 520, 221 NW 434, 60 ALR 1118;

31 AM JUR, Jury § 108; Anderson on Sheriffs, § 280.

We are, therefore, brought to the principal contention of

the defendants, which, in effect, is that they had a lawful

right wilfully to interrupt and disturb the operation of

this public school for the reason that they wrere carrying

signs bearing the above quoted words thereon, and the pur

pose of their marching was to convey to someone (obvi

ously, students or teachers in the school) some idea. That

is, the defendants assert that the Constitution of this State,

Article I, § 17, and the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States, permit them, with im

Decision of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

14a

munity from prosecution, to disrupt the operation of a

public school so long as the means used by them for that

purpose is marching back and forth in front of the school

while carrying banners and placards on which words

appear.

Freedom of speech and protest against the administra

tion of public affairs, including public schools, is a funda

mental right which has been cherished in this State since

long before the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment to

the United States Constitution. It has, however, never

been doubted that this is not an absolute freedom or that

the State, in the protection of the freedom of others and of

its own paramount interests, such as its interest in the

educaion of its children, may impose reasonable restraints

of time and place upon the exercise of both speech and

movement. Thus, in State v. Ramsay, supra, a former

member of a religious congregation, who had been expelled

therefrom for reasons or pursuant to a procedure which

he deemed insufficient and unjust, was convicted and pun

ished for disturbing public worship when he persisted in

breaking into a worship service of the church and reargu

ing the supposed merits of his case. Neither the enact

ment of Gf.S. 14-273 nor its enforcement against these de

fendants in this case violated the Law of the Land Clause

of Article I, § 17, of the Constitution of North Carolina.

The Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States grants to the defendants no license wilfully

to disturb the operation of a public or private school in

this State.

G.S. 14-273 is not discriminatory upon its face. It is

universal in its application. Anyone who does that which

is prohibited by the statute is subject to its penalty. It

does not confer upon an administrative official the author

Decision of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

15a

ity to issue, in his discretion, permits to disturb public

schools and, therefore, does not invite or permit that type

of administrative discrimination against the disseminators

of unpopular ideas which was condemned in. Saia v. New

York, 334 US 558, 68 S. Ct. 1148, 92 L. Ed. 1574.

Neither the statute nor its application in this case has

the slightest relation to State approval or disapproval of

the ideas expressed on the signs carried by the defendants,

or of the position taken by the defendants in their con

troversy, whatever it may have been, with the principal

of the school. Like the ordinance involved in Kovaes v.

Cooper, supra, this statute does not undertake censorship

of speech or protest. As the Court said in the Kovaes

case: “ City streets are recognized as a normal place for

the exchange of ideas by speech or paper. But this does

not mean the freedom is beyond all control.” Again in

Schneider v. State, 308 US 147, 60 S. Ct. 146, 84 L. Ed.

155, the Court, recognizing the authority of a municipal

ity, as trustee for the public, to keep its streets open and

available for the movement of people and property, said,

by way of illustration, a person could not exercise his

liberty of speech “by taking his stand in the middle of a

crowded street, contrary to traffic regulations, and main

tain his position to the stoppage of all traffic * * *” G-.S.

14-273 does not have “the objectionable quality of vague

ness and overbreadth” thought by the United States Su

preme Court to render void the Virginia statute under

examination in NAACP v. Button, 371 US 415, 83 S. Ct.

328, 9 L. Ed. 2d 405. G.S. 14-273 is not “susceptible of

sweeping and improper application” so as to prevent the

advocacy of unpopular ideas and criticisms of public

schools or public officials.

Unquestionably, “ the hours and place of public discus

sion can be controlled” by the State in the protection of

Decision of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

16a

its legitimate and vital public interest in the efficient oper

ation of schools, public or private. See Saia v. New York,

supra; Kovacs v. Cooper, supra. The classic statement by

Mr. Justice Holmes in Schenck v. United States, 249 US

47, 39 S. Ct. 247, 63 L. Ed. 470, “The most stringent pro

tection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely

shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic,” is still

regarded by the Supreme Court of the United States as

a correct interpretation of the First Amendment. The edu

cation of children in schools, public or private, is a matter

of major importance to the State, at least as significant as

the free flow of traffic upon a city street.

In Cox v. Louisiana, supra, the Court recognized that

picketing and parading are subject to state regulation,

even though intertwined with expression and association.

There, the Court, quoting from Gtboney v. Empire Stor

age & Ice Co., 336 US 490, 69 S. Ct. 684, 93 L. Ed. 834,

said, “ [I]t has never been deemed an abridgment of free

dom of speech or press to make a course of conduct illegal

merely because the conduct was in part initiated, evi

denced, or carried out by means of language, either spoken,

written or printed.” Accordingly, the Court there held

valid on its face a state statute prohibiting picketing and

parading in or near a building housing a state court, with

the intent of obstructing or impeding the administration

of justice. The Court said, “Placards used as an essential

and inseparable part of a grave offense against an impor

tant public law cannot immunize that unlawful conduct

from State control.” It deemed “irrelevant” the fact that

“by their lights,” the marchers in that case were seeking

justice. Similarly, it is irrelevant here that the defendants

may have been “by their lights” seeking the improvement

of the educational processes at Southwestern High School.

Decision of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

17a

Whatever their motives, the result of their wilful activi

ties was the disruption of those processes at that school.

That is what the statute forbids and, in so doing, it does

not violate limitations imposed upon the State by the First

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, now

deemed by the Supreme Court of the United States to be

made applicable to the states by the Fourteenth Amend

ment.

It is also irrelevant that the defendants marched silently,

were not on the school grounds, and neither threatened

nor provoked violence. Their actions can admit of no in

terpretation other than that they were planned and carried

out for the sole purpose of attracting and holding the

attention of students or teachers in the Southwestern High

School at a time when the program of the school required

those students and teachers to be engaged in its instruc

tional and training activities. There can also be no doubt

that they succeeded in this purpose. The uncontradicted

evidence as to the defendant Frinks is that, before the

marching began, this statute was called to his attention

and explained to him in substance, to which he replied,

“I don’t care anything about what is in the Statute Books.”

In the light of the uncontradicted evidence, the sentences

imposed by the presiding judge were lenient.

As the Supreme Court of the United States said in Cox

v. Louisiana, supra, “There is a proper time and place for

even the most peaceful protest and a plain duty and re

sponsibility on the part of all citizens to obey all valid

laws and regulations.” The defendants wilfully ignored

this elementary principle of sound government under the

Constitution of our country.

We have carefully examined each assignment of error

and the authorities cited by the defendants in their brief.

Decision of the /Supreme Court of North Carolina

18a

Decision of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

We find nothing in the statute, or in the proceedings in

the court below, which entitles the defendants to a new

trial or to the reversal or arrest of the judgments of the

court below.

No Error.

MEIIEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C .«^^>219