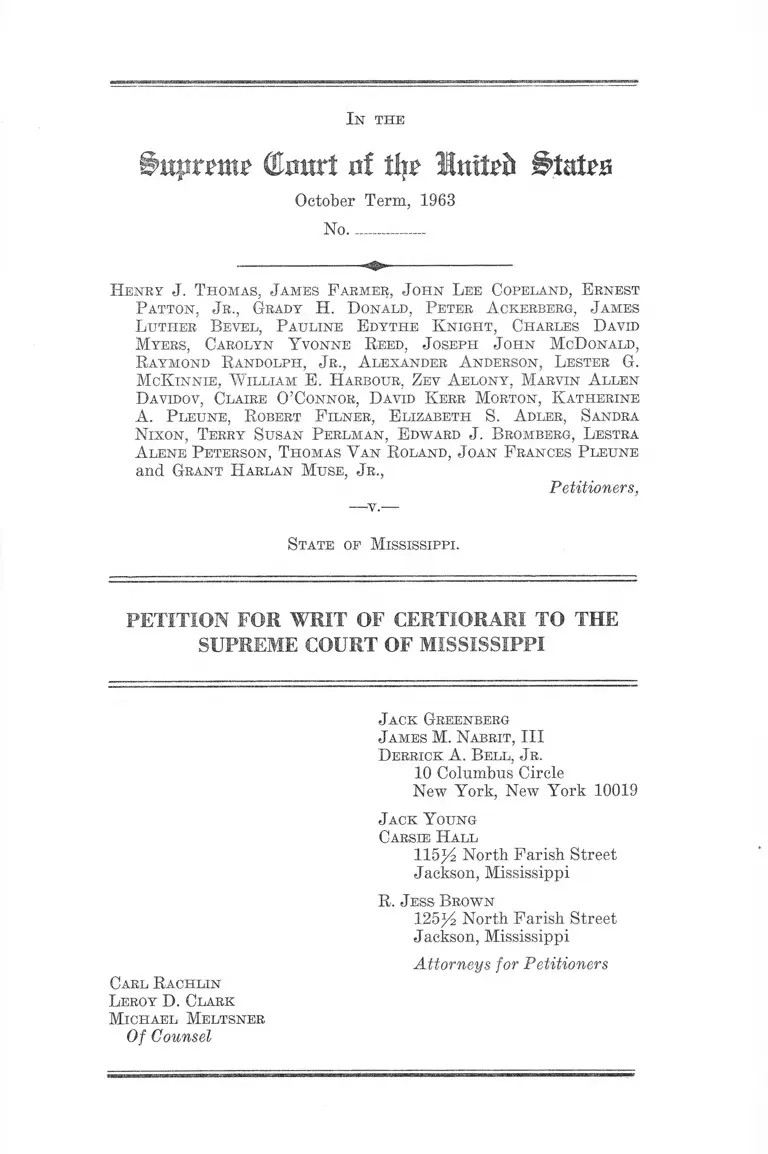

Thomas v. Mississippi Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1963

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Thomas v. Mississippi Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1963. d3af77fe-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0e2d5339-679e-490a-ac89-c54fd6982365/thomas-v-mississippi-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 19, 2026.

Copied!

In the

(Emxt of % 1 nltth BUttz

October Term, 1963

No_________

Henry J. Thomas, James F armer, John Lee Copeland, Ernest

Patton, Jr., Grady H. Donald, Peter A ckerberg, James

Luther Bevel, Pauline Edythe Knight, Charles David

Myers, Carolyn Yvonne Reed, Joseph John McDonald,

Raymond Randolph, Jr., A lexander A nderson, Lester G.

McK innie, W illiam E. Harbour, Zev Aelony, Marvin A llen

Davidov, Claire O’Connor, David Kerr Morton, K atherine

A. Pleune, Robert F ilner, Elizabeth S. A dler, Sandra

Nixon, Terry Susan Perlman, Edward J. Bromberg, Lestra

A lene Peterson, Thomas V an Roland, Joan Frances Pleune

and Grant Harlan Muse, Jr.,

Petitioners,

State oe Mississippi.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF MISSISSIPPI

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Derrick A. Bell, Jr.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Jack Y oung

Carsie Hall

115JT North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi

R. Jess Brown

1 2 5 North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi

Attorneys for Petitioners

Carl Rachlin

Leroy D. Clark

Michael Meltsner

Of Counsel

I N D E X

Opinions Below .................................................................... 2

Jurisdiction ...............................-........ -................................ 2

Questions Presented........ ..................... -................. - ......... 3

Statutory and Constitutional Provisions Involved ....... 4

Statement ........— ...... ................. -............................... -..... 7

Facts in Common .......................................... -.......... 9

A. Trailways Continental Bus Station .........— 11

1. May 24, 1961 .......................-...................... - 11

(a) Bevel and Anderson — ..................... 14

(b) Thomas, Farmer, Copeland, Donald

and Ackerberg ................ 14

2. May 28, 1961 .......... ............. ........................ 16

3. June 2, 1961 ................................................— 17

4. June 7, 1961 ................. ............... ............... 19

B. Greyhound Bus Terminal ......................... 19

1. May 28, 1961 .......................................... 19

2. June 11, 1961 ............................... — ...... 20

3. June 16, 1961 ............................. ...... ......... 21

C. Illinois Central Train Station ---- -------------- 22

1. May 30, 1961 ........................................... .... 22

2. June 8, 1961 ....... ................. .................. . 23

3. June 9, 1961 ............................... ...... -...... - 23

4. June 20, 1961 ......... ..................................... 24

PAGE

ii

PAGE

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and De

cided Below ..... ............................................................. 26

Reasons for Granting the W rit ....... ..................... -............ 31

I. Petitioners’ Convictions Offend Due Process

Because Based on No Evidence of Guilt ......... 32

II. The Statute Used to Convict Petitioners Is So

Vague, Uncertain and Indefinite as to Conflict

With the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment................ .............................. ............... 37

III. These Convictions Constitute State Enforce

ment of Racial Segregation in Interstate Facili

ties Contrary to . the Equal Protection Clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment, Article 1, Sec

tion 8, Clause 2 (Commerce Clause) of the

United States Constitution and 49 U. S. C., Sec

tions 3(1) and 316(d) ........ - ____ ____ ________ 40

IV. These Convictions Conflict With First Amend

ment Guarantees of Free Speech, Assembly

and Association ......................................... 44

Conclusion ............................................................................ 45

A ppendix I ............................................................................ la

Opinion Below, Thomas v. Mississippi............... . la

Concurring Opinion, Thomas v. Mississippi ______ 29a

Opinion Below, Farmer v. Mississippi .................... 36a

Opinion Below, Knight v. Mississippi ............. ..... 40a

I l l

A ppendix II ......................................................... -......... — 46a

Mississippi Code

§ 2351 ........................................................................- 46a

§2351.5 ...... ...................................... -.................. -----.... 46a

§ 2351.7 ................. -............................................-............ 47a

§ 7784 ............. ......... ............ .............................. .......... 48a

§ 7785 .....................................................-....... -......... -.... 49a

§ 7786 ................ ......... ...................... -............... -........... 51a

§7786.01 ...................................................................----- 51a

§ 7787 ...................................-............. ~~........................ 52a

§7787.5 .............................................................. - 52a

Jackson, Mississippi, Ordinance Passed January 12,

1956 ..................................................................................- 55a

A ppendix III ............................................ -..................... — 58a

Opinion Below, Rogers Case ........................ — 58a

Judgment from Mississippi Supreme Court in

Thomas Case ................................-........................... — 59a

Order Overruling Suggestion of Error in Thomas

Case ...................................................... -.......... ....... ..... 61a

T able of Cases

Bailey v. Patterson, 199 F. Supp. 595 (S. D. Miss.

1961) ....................... ........... ..... .................. ..... ....... 10,42,43

Bailey v. Patterson, 206 F. Supp. 67 (S. D. Miss. 1962) 10

Bailey v. Patterson, 323 F. 2d 201 (5th Cir. 1963) ...... 10

Bailey v. Patterson, 368 U. S. 346 ............----- ------- ----- 10

PAGE

IV

Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U. S. 31 .............................10, 32, 42

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U. S. 454 ..... ......... ............... 32, 43

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 ................................... 33

Burstyn v. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495 ......... ............................. 44

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 .... .................. 39, 44

Connally v. General Construction Co., 269 U. S. 385 .... 39

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, aff’g 257 P. 2d 33 (8th

Cir. 1958) ............................................... ........................ 33,37

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 ...... ........ 37, 44, 45

Fields v. South Carolina, 375 U. S. 44 .......................37, 44

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157 ...... ................. .......36, 44

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903 ............ ...................... 32, 43

Henderson v. United States, 339 U. S. 816..................... 43

Henry v. Bock H ill,------ - U. S .------ (April 6, 1964) ....37,44

Keys v. Carolina Coach Co., 64 Motor Carrier Cases

769 .................................................................................... . 43

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451 .................. 39

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267 .................... 43

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U. S. 80 ................... 43

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 ...................................32, 43

NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 ................. ............. 44

NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415 ................................... 39

NAACP v. St. Louis-S. F. B. Co., 297 I. C. C. 335 ....... 43

Nesmith v. Alford, 318 F. 2d 110 (5th Cir. 1963) ...... 39

PAGE

Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U. S. 244 43

Ealey v. Ohio, 360 U. S. 423 ........... ................. ................. 39

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 ..... ..... - ..... ....... 44

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154 ........................-......36,38

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 .............................. 45

Thompson v. Louisville, 363 U. S. 199 ...... ......... 36

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 8 8 .......... ...... .... ...... . 44

United States v. City of Jackson, 318 F. 2d 1 (5th Cir.

1963) ............. 10,41

Watson v. Memphis, 373 U. S. 526 .................................. 33

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 .......................33, 36, 37, 38

Constitutions, Statutes, Ordinances

and R egulations

Jackson City Ordinance, January 12, 1956 (Minute

Book “ F F ” ) ................................. 6,42

49 C. F. R., Section 180(a) (1)-(10) ________________ 32

Mississippi Code, Title 11, Section 2087.5 (1942 as

amended) ............... ................ ............... ............ -.... —4, 9, 27

Mississippi Code, Title 11, Section 2089.5 ................... 9

Mississippi Code, Title 11, Sections 2351, 2351.5,

2351.7 ..................-......... -................. -................. ............... 6,41

Mississippi Code, Title 17, Section 4065.3 ................. ..28, 40

Mississippi Code, Title 28, Sections 7784, 7785, 7786,

7786.01, 7787, 7787.5 ........... 6,41,42

Mississippi Constitution, Section 225 .... ...................... 28

United States Code, Title 28, Section 1257(3) ............. 3

V

PAGE

VI

PAGE

United States Code, Title 49, Section 3(1) ...................3,40

United States Code, Title 49, Section 316(d) ....3, 6, 27, 32, 40

United States Constitution, Article 1, Section 8, Clause

3 .......................................................... ............. ..... 4,27,31,40

United States Supreme Court Rule 23(5) ..................... 3,8

In the

i&ttprpmp tour! of tlie United BtdUs

October T eem, 1963

No................ .

H enry J. T homas, James F armer, J ohn L ee Copeland,

E rnest P atton, J r., Grady H. D onald, P eter A cker-

berg, J ames L uther B evel, P auline E dythe K night,

Charles D avid Myers, Carolyn Y vonne R eed, J oseph

J ohn M cD onald, R aymond R andolph, J r ., A lexander

A nderson, L ester G. M cJvinnie , W illiam E. H arbour,

Z ev A elony, Marvin A llen D avidov, Claire O ’Connor,

D avid K err M orton, K atherine A . P leune, R obert

F ilner, E lizabeth S. A dler, Sandra N ison , T erry

Susan P erlman, E dward J. B romberg, L estra A lene

P eterson, T homas V an R oland, J oan F rances P leune

and Grant H arlan M use, Jr.,

Petitioners,

— v.—•

State of M ississippi.

PETITION FOR WHIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF MISSISSIPPI

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgments of the Mississippi Supreme Court entered

in the above-entitled cases as set forth in “ Jurisdiction,”

infra.

Opinions Below

The opinions of the Mississippi Supreme Court are re

ported as follows: Thomas v. State, 160 So. 2d 657 (App.

p. la) ; Farmer v. State, 161 So. 2d 159 (App. p. 36a) ;

Knight v. State, 161 So. 2d 521 (App. p. 40a). The remain

2

ing cases were decided by brief opinions affirming on the

authority of the Farmer and Thomas cases. Their cita

tions are set forth in the footnote below.1

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Mississippi Supreme Court in

Thomas v. State, No. 42,987, was entered on February 17,

1964. Judgments in Farmer v. State, No. 42,983; Bevel v.

State, No. 42,960; Aelony v. State, No. 42,980; Bavidov

v. State, No. 42,723; McDonald v. State, No. 42,970; Van

Roland v. State, No. 43,029; Myers v. State, No. 42,968;

Peterson v. State, No. 43,034; Patton v. State, No. 42,956;

Katherine Pleune v. State, No. 42,957; Copeland v. State,

No. 42,722; Muse v. State, No. 42,975; O’Connor v. State,

No. 42,982; Joan Pleune v. State, No. 43,036; Donald v.

State, No. 42,951; Nixon v. State, No. 42,966; Filner v.

State, No. 42,978; Anderson v. State, No. 42,985; Perlman

y. State, No. 42,961; Harbour v. State, No. 42,963; Acker-

berg v. State, No. 42,984; Reed v. State, No. 43,031; Ran

dolph v. State, No. 43,032; and Morton v. State, No. 42,973,

were entered on March 2, 1964, and in Knight v. State, No.

42,958; Bromberg v. State, No. 42,967; McKimiie v. State,

No. 42,971; and Adler v. State, No. 42,999, on March 9,

1964.

Suggestions of error were overruled in Thomas, on

March 16, 1964; in Farmer, Knight, Patton, McDonald,

Bromberg, Filner, Aelony, Nixon, Myers, Donald, Acker-

berg, Harbour, Perlman, Reed, Morton, Anderson, Cope

land, Muse, O’Connor, Van Roland, Adler, McKinnie, K. 1

1 Copeland and Bavidov, 161 So. 2d 161; Donald, Patton, and

K. Pleune, 161 So. 2d 162; Bevel, Perlman, and Harbour, 161 So.

2d 163; Nixon, Myers, and McDonald, 161 So. 2d 164; Morton,

Muse, Filner, 161 So. 2d 165; Aelony, O’Connor, Anderson, 161

So. 2d 166; Ackerberg, Roland-, Reed, 161 So. 2d 167; Randolph,

Peterson, J. Pleune, 161 So. 2d 168; McKinnie, 161 So. 2d 520;

Bromberg and Adler, 161 So. 2d 528. (See App. pp. 58a et seq.)

3

Pleune, Davidov, Bevel, Randolph, and Peterson, on April

6, 1964; and in J. Pleune on April 13, 1964.

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to Title

28, U. S. C., §1257(3), petitioners having alleged below,

and alleging here, deprivation of rights, privileges and

immunities secured by the Constitution of the United

States.2

Questions Presented

Whether the arrest, prosecution and conviction of peti

tioners, Negro and white interstate passengers, deprived

them of rights protected b y :

1. the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

in that the records are devoid of any evidence of guilt;

2. the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

in that the statute under which they were convicted is so

vague and indefinite as to afford no ascertainable standard

of guilt and fails to warn of the conduct punishable;

3. the due process and equal protection clauses of the

Fourteenth Amendment in that their arrests, prosecutions

and convictions were designed to enforce racial segrega

tion required by state statutes and by ordinance of the

City of Jackson in interstate facilities;

4. the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the United

States Constitution in that petitioners were exercising

rights of free expression and assembly in peacefully pro

testing racial segregation in interstate facilities;

5. Title 49, United States Code, §§3(1) and 316(d), pro

hibiting racial discrimination in interstate bus and train

facilities;

2 A common writ of certiorari is filed pursuant to Rule 23(5)

of the Rules of this Court.

4

6. Article 1, Section 8, clause 3 of the United States

Constitution (the Commerce Clause) in that the prosecu

tion of petitioners constituted an unlawful burden on com

merce.

Statutory and Constitutional Provisions Involved

These cases involve Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the United States Constitution and Article 1, Sec

tion 8, Clause 3 (Commerce Clause) of the United States

Constitution.

Each petitioner was convicted under Title 11, Code of

Mississippi, Annotated, Section 2087.5 (1942 as amended):

§2087.5. Disorderly conduct—may constitute felony,

when.

1. Whoever with intent to provoke a breach of the

peace, or under circumstances such that a breach of

the peace may be occasioned thereby:

(1) crowds or congregates with others in or upon

shore protecting structure or structures, or a

public street or public highway, or upon a. public

sidewalk, or any other public place, or in any

hotel, motel, store, restaurant, lunch counter,

cafeteria, sandwich shop, motion picture theatre,

drive-in, beauty parlor, swimming pool area, or

any sports or recreational area or place, or any

other place of business engaged in selling or serv

ing members of the public, or in or around any

free entrance to any such place of business or pub

lic building, or to any building owned by another

individual, or a corporation, or a partnership or

an association, and who fails or refuses to disperse

and move on, or disperse or move on, when ordered

5

so to do by any law enforcement officer of any

municipality, or county, in which such act or acts

are committed, or by any law enforcement officer

of the State of Mississippi, or any other authorized

person, or

(2) insults or makes rude or obscene remarks or

gestures, or uses profane language, or physical

acts, or indecent proposals to or toward another

or others, or disturbs or obstructs or interferes

with another or others, or

(3) while in or on any public bus, taxicab, or

other vehicle engaged in transporting members of

the public for a fare or charge, causes a disturb

ance or does or says, respectively, any of the mat

ters or things mentioned in subsection (2) supra,

to, toward, or in the presence of any other pas

senger on said vehicle, or any person outside of

said vehicle or in the process of boarding or de

parting from said vehicle, or any employee en

gaged in and about the operation of such vehicle,

or

(4) refusing to leave the premises of another when

recpiested so to do by any owner, lessee, or any

employee thereof,

shall be guilty of disorderly conduct, which is made

a misdemeanor, and, upon conviction thereof, shall

be punished by a fine of not more than two hundred

dollars ($200.00), or imprisonment in the county jail

for not more than four (4) months, or by both such

fine and imprisonment; and if any person shall be guilty

of disorderly conduct as defined herein and such con

duct shall lead to a breach of the peace or incite a riot

in any of the places herein named, and as a result of

6

said breach of the peace or riot another person or per

sons shall be maimed, killed or injured, then the per

son guilty of such disorderly conduct as defined herein

shall be guilty of a felony, and upon conviction such

person shall be imprisoned in the Penitentiary not

longer than ten (10) years.

Each case involves Title 49, United States Code, Section

316(d) :

. . . It shall be unlawful for any common carrier by

motor vehicle engaged in interstate or foreign com

merce to make, give, or cause any undue or unreason

able preference or advantage to any particular person,

port, gateway, locality, region, district, territory, or

description of traffic, in any respect whatsoever; or

to subject any particular person, port, gateway,

locality, region, district, territory, or description of

traffic to any unjust discrimination or any undue or

unreasonable prejudice or disadvantage in any respect

whatsoever. . . .

Each case also involves Sections 2351, 2351.5, 2351.7, 7784,

7785, 7786, 7786.01, 7787, 7787.5 of the Code of Mississippi,

1942 and ordinance of the City of Jackson, Mississippi,

adopted January 12, 1956, and recorded in Minute Book

“ FF,” page 149. These state statutes and Ordinance of the

City of Jackson are appended, infra pp. 46a-57a.

7

Statement

These are twenty-nine of more than three hundred “ Free

dom Eider” cases tried in Jackson, Mississippi.3 The ar

rests, involving common facts relevant to the constitutional

issues, occurred in 1961 in bus and train terminals in the

City of Jackson.4 Each petitioner was tried separately

though common facts and identical federal constitutional

and state law issues were involved. All were charged

with the same offense and received identical sentences.5 The

8 There are twenty-nine separate records and trial transcripts.

However, the principal record is Thomas v. State, No. 42,987.

The testimony and witnesses are essentially the same in all cases.

4 Arrested at Trailways Continental Bus Terminal were: Henry

J. Thomas, No. 42,987 (It. 4) ; James L. Farmer, No. 42,983 (R.

4 ); John Lee Copeland, No. 42,722 (R. 3) ; Ernest Patton, Jr.,

No. 42,956 (R. 4 ) ; Peter Ackerberg, No. 42,984 (R. 4 ) ; James

Luther Bevel, No. 42,960 (R. 4 ) ; Grady Donald, No. 42,951 (R.

4 ) ; and Alexander Anderson, No. 42,985 (R. 4) (May 24, 1961).

Pauline Edythe Knight, No. 42,958 (R. 4) and Charles David

Myers, No. 42,968 (R, 4) (May 28, 1961) ; Carolyn Yvonne Reed,

No. 43,031 (R. 4) and John J. McDonald, No. 42,970 (R. 4)

(June 2, 1961). Raymond Randolph, Jr., No. 43,032 (R. 4) (June

7.1961) .

The following were arrested at Greyhound Bus Terminal: Lester

G. McKinnie, No. 42,971 (R. 4) ; William Harbour, No. 42,963

(R. 3) (May 28, 1961). Katherine A. Pleune (June 10, 1961) (No.

42,957). Zev Aelony, No. 42,980 (R. 4 ) ; Marvin Allen Davidov,

No. 42,723 (R. 4) ; Claire O’Connor, No. 42,982 (R. 4 ) ; David

Kerr Morton, No. 42,973 (R. 4) (June 11, 1961). Robert Filner,

No. 42,978 (R. 4) and Elizabeth S. Adler, No. 42,999 (R. 4) (June

16.1961) .

The following were arrested at Illinois Central Train Terminal:

Sandra Nixon, No. 42,966 (R. 4) (May 30, 1961) ; Terry Susan

Perlman, No. 42,961 (R. 4) (June 8, 1961). Edward Bromberg,

No. 42,967 (R. 4) • Lestra Peterson, No. 42,034 (R. 4) ; Thomas

Van Roland, No. 43,029 (R. 4 ) ; Joan Frances Pleune, No. 43,036

(R. 4) ; and Grant Harlan Muse, No. 42,975 (R. 4) (June 20, 1961).

5 In Municipal Court each petitioner received 60 days suspended

sentence and $200.00 fine. In trials de novo in the County Court

of Hinds County they were sentenced to four months in jail and

$200.00 fine, the maximum provided by statute.

8

same state law and federal constitutional questions were

raised in each case after trials in the Municipal and County

Courts of the City of Jackson,6 and on appeal to the Circuit

and Supreme Courts of Mississippi. See infra, pp. 26-31.

Three affirming opinions were written for all twenty-

nine cases by the Mississippi Supreme Court: Thomas v.

State, No. 42,987; Farmer v. State, No. 42,983; and Knight

v. State, No. 42,958. See infra, pp. la-45a. All others were

affirmed without opinion, merely citing Thomas and Farmer.

See infra, p. 58a. Therefore, for convenient presenta

tion, the issues are brought here by petition for writ of

certiorari in a single document. Supreme Court Rule 23(5),

cf. Petition for Writ of Certiorari, Goher, et al. v. City

of Birmingham, 373 U. S. 374.

Petitioners, white and Negro interstate passengers, were

tried and convicted in the Municipal Court of Jackson

under affidavits charging them with breach of the peace

under Section 2087.5, Miss. Code Annot., 1942 as amended,

in that they did “ wilfully and unlawfully congregate with

others” in “ a place of business engaged in selling members

of the public” and failed or refused “ to move on when

ordered” by a law-enforcement officer.7 Upon conviction

they were sentenced to four months in jail and $200.00 fine,

which convictions were affirmed on appeal to the County,

Circuit, and Supreme Courts of Mississippi.

For purposes of clarity, a resume of the facts in common

in all twenty-nine cases is presented first. Events are then

6 The sentencing portion of each of the 29 records is identical.

Record citations are indicated by name of defendant and page.

7 (R. Ackerberg 4, Adler 4, Aelony 4, Anderson 4, Bevel 4,

Bromberg 4, Copeland 3, Davidov 4, Donald 4, Farmer 4, Filner

4, Harbour 3, Knight 4, McDonald 4, McKinnie 4, Morton 4, Muse

4, Myers 4, Nixon 4, O’Connor 4, Patton 4, Perlman 4, Peterson

4, J. Pleune 4, K. Pleune 3, Randolph 4, Reed 4, Thomas 4, Van

Roland 4.)

9

described sequentially and by place of arrest as follows:

Trailways Continental Bus Station, Greyhound Bus Ter

minal and Illinois Central Railroad Station. Thereafter

follows a detailed exposition of the facts of all the cases

annotated by record citations.

Facts in Common8

Almost identical circumstances surrounded the arrests

of these twenty-nine petitioners. All were interstate pas

sengers protesting racial segregation in interstate bus and

train facilities. All were in racially mixed groups and all

were arrested by police immediately upon arrival in the

City of Jackson.

a 8 In the spring and summer of 1961, more than three hundred

“Freedom Riders,” including these twenty-nine petitioners at

tempted to use travel facilities on an unsegregated basis in Jack-

son, Mississippi. ̂ They were arrested, jailed and later charged

with violating Mississippi disorderly conduct—breach of the peace

statutes. (Title 11, §§2087.5 and 2089.5.)

Though the facts and charges were almost identical, the State

of Mississippi required a separate trial for each of the more than

three hundred persons arrested, including these twenty-nine peti

tioners. Trials were conducted at the rate of two per day over

a period of months. All were convicted. All were initially fined

two to five hundred dollars ($200,00-$500.00) and given sentences

ranging from sixty days suspended to four months in jail, not

suspended. Practically all sought trials de novo in the County

Court and posted bonds in the amount of five hundred dollars

($500.00) each to assure appearance. Two persons dismissed their

County Court appeals and served out their fines and sentences.

Fifty-four persons entered pleas of nolo contendere, paid fines

and costs and accepted suspended jail sentences. The rest pleaded

not guilty, had their convictions affirmed and sentences increased

to a fine of five hundred dollars ($500.00) and four months in

jail. Those appealing to the Circuit Court from County Court

convictions were required to post additional cash bonds of one

thousand dollars ($1,000.00) each, bringing bond to one thousand,

five hundred dollars ($1,500.00) per person. Indeed, bond costs

alone exceeds three hundred seventy-two thousand dollars ($372,-

000.00). Travel costs, counsel fees and other expenses have fur

ther increased the financial burden.

An additional fourteen thousand dollars ($14,000.00) was paid to

the Clerk of the Mississippi Supreme Court as security for prepara-

1 0

Captain of Police Ray testified in each case that he had

advance notice that petitioners were coming to Jackson

to “ create an incident.” He had numerous police officers

on the scene for the purpose of arresting them and a patrol

wagon parked outside to carry petitioners off to jail. In

each case, he alleged that “ ugly” crowds met petitioners,

though prosecution witnesses as well as petitioners con

tradicted Ray’s testimony. In no case did Captain Ray

arrest anyone in the crowd “ threatening” petitioners.

In no instance did Captain Ray inquire of petitioners

whether they had reason to be in the station. No allegation

was made that any of the petitioners committed any act of

violence or was anything but peaceful. The only evidence

of guilt is their mere “ presence” in the bus and train

terminals in racially mixed groups. In each case, imme

diately upon arrival they were ordered to “ move on and

move out of the terminal” and upon refusal, were arrested.

State statutes as well as an ordinance of the City of

Jackson required segregation in interstate bus and train

facilities (App. pp. 47a-57a). At all places of arrest there

were separate waiting rooms for Negro and white persons

designated by “ white” and “ colored” signs “ By Order of

Police.”

Hereafter follows the detailed facts upon which the

above summary is based.

tion of the twenty-nine records for this petition for certiorari. This

security, like all appearance and appeal bonds posted in these cases,

was in the form of cash as no surety bonds can be obtained by civil

rights demonstrators in Mississippi. See Memorandum of United

States as Amicus Curiae, pp. 2-4, on Motion for a Stay of Injunc

tion Pending Appeal, Bailey v. Patterson, 368 U. S. 346.

Collateral proceedings arising out of these incidents are reported

as follows: Bailey v. Patterson, 199 P. Supp. 595 (S. D. Miss. 1961),

vac. 369 U. S. 31; on remand 206 F. Supp. 67 (S. D. Miss. 1962) ;

aff’d in part and rev’d in part, 323 P. 2d 201 (5th Cir. 1963). See

also Z7. 8. v. City of Jackson, 318 P. 2d 1 (5th Cir. 1963).

1 1

A. Trailways Continental Bus Station:

1. May 24, 1961:

Petitioners Thomas, Farmer, Copeland, Patton, Donald,

Ackerberg, Anderson and Bevel9 boarded Trailways buses

in Montgomery, Alabama for Jackson, Mississippi on May

24, 196110 11 (R. Thomas 562-63). The buses arrived in Jack-

son under heavy police escort (R. Thomas 406).11 After

9 Petitioners Bevel’s and Anderson’s bus arrived in Jackson at

2 :00 p. m. (R. Bevel 18; Anderson 217). They were with a racially

mixed group of twelve (R. Bevel 18). Thomas, Farmer, Copeland,

Patton, Donald and Ackerberg arrived in Jackson together around

4:45 p. m. (R. Thomas 409, 444) with a group of fifteen (R.

Thomas 535). The facts governing the arrival of the two buses are

almost identical.

10 Petitioners had gathered in Montgomery, Alabama from vari

ous parts of the country (R. Thomas 311). Here they regrouped

and travelled to Jackson (R. Thomas 311, 368, 371). W. B. Padgett,

Alabama Department of Public Safety, testified:

“ I had read the itinerary [Freedom Rider] in newscasts, news

papers . . . after leaving Washington, D. C., it was from

Augusta, Georgia, to Atlanta, Georgia, southern part of Georgia

to Birmingham, Alabama; from Birmingham, Alabama to

Montgomery, Alabama; from Montgomery, Alabama to Jack-

son, Mississippi; from Jackson, Mississippi, to New Orleans,

Louisiana and lower end of Louisiana” (R. Thomas 374, 375).

11 Padgett was at the Alabama-Mississippi state line when the

first and second “Freedom Rider” buses crossed on May 24, 1961

(R. Thomas 394-398, 373, 377) and testified:

“ . . . After the first bus passed through the state line into

Mississippi, the officers escorting that bus from Montgomery

to the state line remained there until the second bus passed

through. That would have made . . . approximately twenty-

eight units of automobiles transporting state investigators,

highway patrol officers, National Guard, with each bus. There

were approximately five cars with heavy arms” (R. Thomas

399).

He also stated:

“At the time the [second] bus actually arrived at the line, . . .

there was one helicopter and two or three airplanes circling

the area, maintaining air surveillance over this area.

# # # * *

1 2

National Guardsmen and newspapermen unboarded (R.

Thomas 565; Farmer 25; Bevel 22-23), petitioners walked

quietly down the ramp between two lines of newspapermen

and policemen12 (R. Thomas 565, 593-594; Bevel 24) into

the white waiting room13 14 (R. Thomas 505, 606-607). Captain

of Police Ray testified that “ 50 or 60 people” were inside

the terminal including “ twenty-five” newspapermen (R.

Thomas 566, 617)11 and “ six or eight police officers.” About

75 policemen with three police dogs surrounded the bus

station (R. Bevel 19; Farmer 21).

Ray also testified that he had advance notice that peti

tioners were coming to Jackson to “ create an incident” and

was present at the terminal , “ to maintain law and order”

(R. Thomas 573-574, 613; Bevel 18). He stated that people

in the terminal were in a “ foul mood” and “ as they [peti

“ There was no incident . . . At the time the bus actually trans

ferred from Alabama to Mississippi, there were an estimated

one hundred highway patrolmen, and National Guardmen,

and a large group of Mississippi highway patrolmen and Mis

sissippi National Guard at the time of the actual transfer”

(R. Thomas 400).

12 Captain of Police Ray testified in Thomas:

“ The Trailways bus arrived about 4 :45 p. m., parked in loading

dock number eight, and after this bus stopped, a group of

National Guardmen got off the bus, then a group of news

papermen or reporters, people with cameras and so forth, got

off the bus; then a group of fifteen, of which Henry Thomas

was one of them got off the bus. They kind of stayed together

until they began walking down the ramp (R. Thomas 565).

# # # # #

“ They walked in the door to the waiting room” (R. Thomas

539).

13 The main waiting room located on the west side of the termi

nal was designated for white persons (R. Thomas 505, 507, 591-

592), with a smaller waiting room on the east side of the terminal

for Negroes.

14 Ray testified that “ thirty or forty” people were in the termi

nal when petitioner Bevel arrived (R. Bevel 18). See, too (R.

Farmer 19).

13

tioners] entered the terminal, feeling that it would be best

to get . . . the group . . . out of the bus station, in order to

prevent violence, I . . . ordered them to move on and to

move out of the terminal. They acted as though they did

not hear me even though I talked in a loud tone of voice”

(E. Thomas 571). However, he neither spoke to nor ar

rested persons allegedly threatening petitioners (E. Thomas

624; Bevel 28; Donald 34; Farmer 27; Ackerberg 73).

Wallace Dabbs, a reporter for the Clarion Ledger and a

prosecution witness, testified that petitioners caused no

violence at the time they entered the bus terminal (E.

Thomas 503, 513), and that they walked peacefully into the

white waiting room (E. Thomas 503, 505). Moreover,

“no incidents” or “ remarks of an offensive nature” oc

curred inside the terminal (E. Thomas 513, 631; Farmer

28), and police were “ maintaining superb order in the sta

tion” (E. Thomas 513, 514).15

Another prosecution witness, W. C. Shoemaker of the

Jackson Daily News testified that he saw no act of violence

committed either by petitioners or other persons in the

station (E. Ackerberg 52) and that the police had “ every

thing under control” 16 (E. Thomas 541, 544, 545, 546;

Farmer 38).

15 On cross-examination, Dabbs testified :

“ Q. So the upshot of it is that during the entire period

from the time that defendant arrived in the white waiting

room until you saw him taken away in the paddy wagon, you

saw no violence or anything untoward at all?

A. No.

Q. And the police had the situation outside on the street

as much under control as they had inside the terminal?

A. I would say so, yes.

# * * * *

Q. You saw no violence in Jackson whatsoever?

A. No; that’s true” (R. Thomas 517).

16 Shoemaker wrote an article on the May 24 events which

appeared in the Jackson Daily News on May 25, in which he stated

that when the “Freedom Riders” arrived only “ a few persons

14

(a) Bevel and Anderson

Petitioners Bevel and Anderson, both Negroes (R. Bevel

75-76; Anderson 239), arrived in Jackson on the first bus

around 2:00 p.m. in a racially mixed group of twelve (R.

Bevel 18; Anderson 217). Inside the terminal eight of them

went to the restroom while four walked to the concession

stand (R. Bevel 25; Anderson 218).

Captain Ray testified that he arrested the four at the

concession stand first and then went into the restroom and

arrested the other eight defendants (R. Bevel 30). Bevel,

Anderson and their companions were alone in the restroom

when Captain Ray entered and ordered them to “ move on

and move out of the terminal” (R. Bevel 25, 26; Anderson

228). They refused and were arrested (R. Bevel 26; Ander

son 219). Bevel and Anderson were quiet and peaceful at

all times (R. Bevel 34; Anderson 232).

(b) Thomas, Farmer, Copeland, Donald

and Ackerberg

These petitioners arrived on the second bus at 4 :45 p.m.

(R. Donald 14, 15; Farmer 20; Copeland 15-16, 25-26;

Ackerberg 48) in a group of “ fourteen Negroes and one

white” (R. Donald 51, 53). On entering the station they

were ordered immediately to “ move on and move out”

(R. Thomas 571; Farmer 25; Copeland 28; Donald 17;

Ackerberg 58, 64). When they did not respond they were

arrested and taken to the police wagon which had been

parked outside the terminal prior to their arrival (R.

Thomas 625-26). Petitioner Donald testified:

watched from the sidewalk a few blocks away.” He also stated

that the “police watched each arriving bus in the event more

'Freedom Eiders’ attempted to violate segregation laws” (R.

Thomas 543).

15

[W]hen I entered the Trailways bus station, several

of the persons who accompanied me to the Trailways

bus station were already being arrested, and I pro

ceeded to turn around, to leave along with another

companion of mine, and one officer said, ‘you wait here

too, you are under arrest.’ He asked my name, I gave

him my name, and he said, ‘you are under arrest also’

(E. Donald 54).

Petitioners were peaceful and quiet at all times (R.

Thomas 621, 629; Donald 22; Farmer 25, 26, 36; Copeland

35).

Captain Eay, however, felt that petitioners’ “presence”

could cause “possible” disorder (R. Thomas 613, 620):

Q. [T]he time you ordered defendant and his com

panions to leave, was there any act of violence com

mitted, up to this moment ?

A. Nothing other than their presence there, by which

a breach of the peace might have been occasioned (E.

Thomas 613).

Ray also testified:

Q. . . . So, the only disorderly act, if you can call it

that, in the waiting room, that you saw after the arrival

of the defendant and his companions, or saw anywhere

in the bus terminal, was the refusal to obey your order

to leave the station?

A. That was the only arrest made there and that was

the only disorderly conduct that had happened at that

time (E. Thomas 625).

In Ackerberg Ray stated:

Q. Now did you see any acts of violence committed

by the defendant . . .?

16

A. No, Ms presence there was what caused the vio

lence or would have caused it (E. Ackerberg 69).

2. May 28, 1961:

Petitioners Knight, a Negro (E. Knight 63), and Myers,

a white person (E. Myers 42), were arrested around 1:30

p.m. with seven other companions in the white waiting room

(E. Knight 31; Myers 15, 17).

Captain Eay testified:

They all came in together. After they got inside the

terminal, they split up. This defendant [Myers] and

three others stayed together, and the other four, they

moved to another part of the terminal, and then I gave

them an order (E. Myers 17).

When Myers refused to obey Eay’s order to move out of

the terminal he was arrested (E. Myers 18). Eay further

testified that everything was peaceful until Myers and his

group arrived, that a crowd was in the station in an “ugly

and angry” mood threatening to harm Myers (E. Myers

17), and that he “wanted to get the cause or the root of

the trouble out of there and this defendant and his group

was the cause or root of the trouble” (E. Myers 27). How

ever, Eay admitted that no overt act was committed against

Myers (E. Myers 27) and that Myers created no disturbance

himself (E. Myers 26, 32).

Q. All right, Captain Eay. Now, the defendant

walked in, and he goes immediately to a seat and sits

down. That’s right?

A. That’s correct.

Q. Did he do anything other than go immediately

to this seat and sir [sic] down?

A. No (E. Myers 27).

17

Petitioner Knight was arrested at the telephone booth

when, according to Captain Ray, “ other people in the station

started towards her” (R. Knight 24). No effort was made

to arrest these persons (R. Knight 24, 25). Ray stated

that Miss Knight:

[W]alked into the terminal . . . She walked in with

her group; they stopped. I ordered them to move on

and move out of the terminal. At that time this defen

dant and her group separated. This defendant walked

to the west-end of the waiting room to a telephone

booth (R. Knight 24).

Miss Knight was quiet and peaceful at all times (R.

Knight 23, 31-32).

Ray testified that “ 30 or 35” people were in the terminal

upon petitioners’ arrival along with “ 12 to 15” policemen

(R. Myers 16).

3. June 2, 1961 :

Petitioners Reed and McDonald arrived at the Trailways

terminal around 6:40 in the evening (R. Reed 16). Miss

Reed, a Negro (R. Reed 60) was arrested in the white

waiting room when she refused to obey Captain Ray’s order

to move out of the terminal (R. Reed 29). Ray testified:

Q. When you entered the waiting room, did you see

the defendant?

A. I did.

Q. Where was she at the time?

A. She was still walking. When I entered, she was

walking. She was walking to the news or concession

stand.

# # # # #

Q. Now, as the defendant entered the waiting room

and walked toward the concession stand, what did you

observe?

18

A. I observed the crowd. At that time it became in

an ugly, angry mood, and I determined that this defen

dant was the cause of the trouble.

# # # # #

Q. I see. And did you determine who they were

mad at?

A. At this defendant and her group.

Q. All right. Did you say anything to any of these

people at this time, this group of people?

A. I did not at that time.

# # # # #

Q. . . . Now, when you gave your order, what was

the defendant doing . . .?

A. . . . She was standing there.

# * # * #

Q. Now, what did you say to this defendant?

A. I ordered her to move on and move out of the

terminal.

Q. Did the defendant say anything, make any reply?

A. She stood there as though I had said nothing

(E. Eeed 27-29).

McDonald, a white person (R. McDonald 67) separated

from the group and entered the “ Negro” waiting room

where he was immediately arrested (R. McDonald 15, 16,

17).

C. R. Keys of the Jackson Police Department testified on

cross-examination :

Q. In other words, he wasn’t doing anything dif

ferent from the other people that came in prior to his

arrival that would cause disturbance in there?

A. Nothing other, only his presence.

Q. Only his presence?

A. That is correct (R. McDonald 33).

19

There were sixteen police officers in the terminal (R.

Eeed 17).

4. June 7, 1961:

Petitioner Randolph, a Negro (R. Randolph 67) and six

companions entered the Trailways terminal about 1 :10 in

the afternoon (R. Randolph 16). Captain Ray testified:

I arrived at the Trailways bus terminal . . . twenty

minutes before this defendant and his group arrived.

At that time, everything was peaceful, normal, people

going about their business in a normal way. This de

fendant and his group came in, they got off the bus;

they all waited together until they got their luggage.

They walked down the ramp together until they got

to the first waiting room, and at that time, three

went into that waiting room, and then this defendant

and two others continued on to the next waiting room,

and by that time people were beginning to mill around

and moving toward this defendant (R. Randolph 18).

He determined that Randolph was the “ root of the trouble,

he and his group” and ordered him to leave the terminal

(R. Randolph 19). Randolph refused and was arrested (R.

Randolph 19). Randolph was entirely peaceful and orderly

(R. Randolph 33).

B. Greyhound Bus Terminal:

1. May 28, 1961s

Petitioner McKinnie, a Negro (R. McKinnie 66), was

arrested around 5 :30 a.m. in the white waiting room of the

Greyhound bus terminal (R. McKinnie 15, 66).

Captain of Police Ray testified that McKinnie:

. . . Goes in the terminal, he kind of turns to the right

after he passes the ticket office and so forth, and there

2 0

is a water cooler there. He and six others were at the

water cooler, and that’s when I approached this de

fendant because the crowd was in an ugly and angry

mood after this defendant entered. I saw that there

was going to be trouble, I tried to determine the cause

of the trouble, and I found out the cause was this

defendant and his group. So, not wanting any dis

turbance or any violence, I was going to remove that

cause and I ordered this defendant and his group to

move on and move out of the terminal. I gave that

order twice, I asked if they understood the order and

if they were going to obey the order, and they did not

and that’s when I arrested them (R. McKinnie 22-23).

2. June 11, 1961:

Petitioners Aelony, Davidov, O’Connor and Morton, all

white persons (R. Aelony 103; Davidov 76; O’Connor 66;

Morton 69), arrived in Jackson from Memphis, Tennessee

(R. Aelony 50; Davidov 14; O’Connor 16). They were ar

rested as they entered the Negro waiting room of the Grey

hound terminal around 12:45 p.m. in a racially mixed group

of six (R. Davidov 16; Aelony 50).

Captain Ray testified that “ 25 or 35 people” were inside

the bus terminal and that they became “ ugly and angry”

when petitioners entered (R. Davidov 17; Aelony 46). In

order to prevent violence, he “ acted quickly” and asked

petitioners to move out of the terminal (R. Aelony 46, 47).

Petitioners refused and were arrested (R. Davidov 19). He

admitted that petitioners were peaceful, but stated that their

“ presence” created a disturbance.

Q. Now, Captain Ray, I believe you testified that

prior to this, and at this time, this defendant had said

or had done nothing, to indicate that it was his pur

pose to create a disturbance. I mean, he had done noth

2 1

ing, or he had said nothing, or he made no gesture that

indicated that he intended to create a disturbance?

A. No, his presence there was what created a dis

turbance.

Q. But he didn’t do anything?

A. No, he didn’t (R. Davidov 30, 31).

3. June 16, 1961:

Petitioners Pleune, Pilner and Adler, white persons (R.

Pleune 58; Filner 74; Adler 230), arrived in Jackson from

Nashville, Tennessee at 1 :10 in the afternoon (R. Filner 45,

46; Pleune 15) and were arrested as they entered the wait

ing room of the Greyhound terminal (R. Filner 42).

Petitioner Filner testified:

We got off the bus. There was five of us. We walked

into the waiting room, in the bus station. Sat down at

the counter, and I looked around and a police officer

came toward us. The other people kept watching with

curiosity. He [Captain Ray] came toward us and or

dered us to move on, and we didn’t, because it was our

constitutional right to be there, and he arrested us.

Q. Was there any indication, as far as you were

able to ascertain as to what mood these people were in?

A. Well, they didn’t cause any trouble. Of course,

some of these were watching what was going on . . .

just curious, I am sure. The police officer mentioned

they seemed to be advancing threateningly; I didn’t

notice any of this. As soon as we walked in, the police

officer came toward us (R. Filner 41-42).

Filner further testified that his group had been in the

station only a minute when the police walked up to them

(R. Filner 42), that they were peaceful and quiet and

2 2

simply wanted something to eat after a long trip (R.

Filner 42).

Captain Bay testified:

The bus pulled in. This defendant and the group

that he was with got off and walked inside the wait

ing room, and when they entered the waiting room,

people began to get up and moved toward them. That’s

when I felt it necessary to act, and act quickly, to pre

vent any violence. At that time, he had a seat at the

stool, and I ordered him to move on and move out of

there. I asked him if he’d heard the order and if he

was going to obey the order (R. Filner 19).

Petitioners were neither noisy nor violent (R. Filner 42).

Moreover, Eay could recall no actual threats against peti

tioners from the crowd (E. Filner 20-23).

C. Illinois Central Train Station:

1. May 30, 1961:

Petitioner Sandra Nixon, a Negro (R. Nixon 69), arrived

at the Illinois Central train station around 10:15 in the

morning (R. Nixon 15-17) with seven companions (R. Nixon

17). She entered the white waiting room and was im

mediately ordered to leave by Captain Ray who testified

that persons in the station became restless and threatened

to harm her (R. Nixon 20). Determining that petitioner

Nixon and her group was “ the cause or root of the trouble”

he ordered her to move out of the terminal (R. Nixon 18).

She refused and was arrested (R. Nixon 18). He did not

inquire of her business there and stated that she at no

time spoke to him (R. Nixon 27).

2. June 8, 1961:

Petitioner Perlman, a Negro (E. Perlman 61), arrived at

the train terminal at 10:10 in the morning. She was ar

rested upon entering the white waiting room with eight

others (R. Perlman 15, 20-21).

On cross-examination, Captain Ray testified:

Q. All right, sir. Now, Captain Ray, you said that

when the defendant entered the waiting room, that

you were in there, I believe, when she came inf

A. That’s correct.

Q. What was the disposition of the people who were

in the waiting room when the defendant came in?

A. After this defendant and her group entered, they

became in an ugly and angry mood, moved toward this

defendant, started mumbling to each other and that’s—

Q. Do you know— , pardon me.

A. And that’s when I determined the cause of the

trouble and felt it necessary at that time to remove

that cause and I ordered her to leave.

Q. Did you talk to any of these people?

A. At that time?

Q. At that time.

A. At that time, I did not (R. Perlman 23).

3. June 9, 1961:

Bromberg, a white person (R. Bromberg 37), was ar

rested at 5 :30 in the morning as he entered the train ter

minal with a. racially mixed group (R. Bromberg 14, 15, 20).

He was neither loud nor committed any act of violence (R.

Bromberg 22).

Ray stated that “ about fifteen” people were in the ter

minal (R. Bromberg 18) and about a dozen policemen (R.

Bromberg 20). He testified:

23

24

Q. Well, explain to the Court, if you would, why

with these other people you would ask them what

their business was before ordering them to move on,

whereas this defendant you ordered him to move on

without making any inquiries as to what his business

was?

A. Well, as I stated earlier, I was there to maintain

law and order. When this defendant and his group

entered, I felt it necessary to act and act quickly. I

didn’t feel like that I needed to go into a lengthy con

versation, because I was there to prevent violence.

Q. Was there a danger of violence that day?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Now from whom did you fear the violence?

A. We didn’t know what to expect, but from the

remarks that had been made anything could have

happened.

Q. Well, were you afraid this defendant might be

come violent?

A. No, sir, but he was the root of the trouble.

Q. Did this defendant talk in a loud voice or curse?

A. No, sir.

Q. Or push anybody?

A. No, sir.

Q. Was he armed?

A. No, sir.

Q. Did he do anything out of the way, anything dif

ferent from what any other person ordinarily would

do in the train station?

A. No, sir (R. Bromberg 22-23).

4. June 20, 1961:

Petitioners Peterson, Van Roland, Pleune and Muse,

all white persons (R. Peterson 69; Van Roland 84; Pleune

73; Muse 84), refused to leave the Negro waiting room

25

when ordered to by Captain. Bay and were arrested along

with ten others (E. Peterson 17; Van Eoland 15; Pleune

17; Mnse 17). Petitioner Van Eoland testified:

I had my bag with me. I got off the train and walked

down a platform and down some stairs, I believe it was,

or a ramp into what was the terminal, the waiting room

in the terminal (E. Van Eoland 40).

. . . I walked into the waiting room and I decided that,

I wanted some lunch. So I asked the first officer that

I saw if there was a lunch room in the terminal. He

told me there wasn’t, so I decided I would just sit down

on the bench in the waiting room for a few minutes

until I could find out where there was a place to eat.

. . . I had just about got seated when Captain Eay

approached me and he asked me to move on. I asked

him why, and he didn’t tell me. He just ordered me

to move on again, and I didn’t see any reason for

doing so. And at that point Captain Eay placed me

and the people with me under arrest and put us in the

paddy wagon that was waiting outside (B. Van Eoland

42).

Van Eoland further testified that police were stationed

around the walls in the waiting room and that there were

no other persons in the station except the police (E. Van

Eoland 44).

Petitioner Muse, in the same group, testified:

. . . I was rather heavily loaded with baggage and was

the last one to get off the coach, and the others of the

group that I was traveling with, had gone into the wait

ing room by the time I got off the platform. As I ap

proached the waiting room, I heard voices and I arrived

in the waiting room to hear ‘on you all.’ I subsequently

learned that that was the last of two commands to move

on, and it was followed by an arrest, and we were put

aboard the jail wagon (R. Muse 39).

Muse was arrested in the Negro waiting room (R. Muse

41). He saw “ three colored persons sitting on benches”

in the waiting room. (R. Muse 41).

Captain Ray testified that Muse was present when he gave

the group both orders to move on (R. Muse 50). Moreover,

Ray stated that a crowd in the station was threatening peti

tioners at the time he arrested them (R. Muse 50, 51).

How the Federal Questions Were

Raised and Decided Below

Petitioners were convicted in the Municipal Court of

the City of Jackson, sentenced to sixty days suspended sen

tence and two hundred dollars ($200.00) fine, and appealed

to the County Court of Hinds County, Mississippi for trials

de novo. Pleas of not guilty were entered by all petitioners.

During trial in the County Court it was ruled that no

evidence would be permitted as to the race of petitioners

or racial segregation in travel facilities. Proof was of

fered at the end of trial that (1) an ordinance of the City

of Jackson, Mississippi and State statutes required racial

segregation on all common carriers (App. pp. 46a-57a), and

(2) petitioners used the racially segregated waiting rooms

on a racially desegregated basis.

At the conclusion of the State’s case petitioners filed

motions for directed verdict alleging:

(1) the State failed to prove the offense charged in the

affidavit;

27

(2) a conviction would deprive them of due process of

law secured by the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution because there was no evidence of guilt;

(3) that Section 2087.5 under which they were charged

was unconstitutional on its face and as applied because

(a) vague, (b) it failed to warn them of the conduct pro

hibited, and (c) it penalized conduct constitutionally pro

tected under the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the

United States Constitution;

(4) the conviction would violate the Fourteenth Amend

ment’s equal protection clause, Article 1, Section 8, Clause

3 of the United States Constitution, as well as the Inter

state Commerce Act, 49 U. S. C. 316(d) (and interpretation

thereof by the Interstate Commerce Commission) in that

Section 2087.5 of Miss. Code Annot., 1942 as amended, and

as applied, denied them the right to use interstate bus

facilities on a racially desegregated basis and deprived

them of the right to move freely from state to state solely

because of race.17

The motions were denied and petitioners were convicted

and sentenced to serve four months in jail and five hun

dred dollars ($500.00) fine. Petitioners requested instruc

tions to the jury requiring the jury to bring in a verdict of

not guilty should they find that the only act committed by

petitioners was refusing to move when ordered to do so by

the arresting officer. The court refused the instruction and

the jury returned a verdict of guilty.

17 (R. Ackerberg 32; Adler 38, 228; Aelony 75; Anderson 237,

265; Bevel 45, 73; Bromberg- 36, 59; Copeland 39; Davidov 74;

Donald 44; Farmer 41; Filner 36, 53; Harbour 32; Knight 35;

McDonald 37; McKinnie 35; Morton 41, 67 ; Muse 31; Myers 35;

Nixon 43, 67; O’Connor 64; Patton 40 ; Perlman 33, 59; Peterson

39 ; J. Pleune 47 ; K. Pleune 29, 55; Randolph 34; Reed 32; Thomas

674; Van Roland 34.)

Motions for new trial alleging that the convictions were

contrary to the evidence and renewing objections raised in

the motion for directed verdict were also denied.18

Appeals were taken to the Circuit Court for the First

Judicial District of Hinds County alleging that the court

below erred in:

(1) denying the motions for directed verdict;

(2) overruling the motions for new trial;

(3) refusing to permit testimony that the terminals were

racially segregated by order of the Police Department, and

that petitioners were in racially mixed groups; and

(4) refusing to judicially notice §§4065.3, 2065.7, 2351.5,

2351.7 and 4259 of the Miss. Code and §225 of the Missis

sippi Constitution, and the Jackson city ordinance (Minute

Book “ FF,” p. 149) 1956, requiring segregation in travel

facilities. The Circuit Court affirmed the convictions.

On appeal to the Supreme Court of Mississippi peti

tioners again alleged that the court below erred in (1)

denying their motions for directed verdicts, (2) overruling

the motions for new trial, (3) sustaining objections to

the introduction of the ordinance of the City of Jackson

requiring racial segregation in travel facilities.

In Thomas the Supreme Court of Mississippi affirmed

the conviction and held that (1) the evidence supported the

arrest and conviction of defendant for disorderly conduct,

and (2) the conviction violated no state or federal law.

The court stated:

18 (E. Ackerberg 33; Adler 229; Aelony 101; Anderson 266;

Bevel 74; Bromberg 60; Copeland 66; Davidov 75; Donald 81;

Farmer 69; Filner 73; Harbour 65; Knight 62; McDonald 66J4 •

McKinnie 65; Morton 68; Muse 83; Myers 63 ; Nixon 68 ; O’Connor

65; Patton 68; Perlman 60; Peterson 68; J. Pleune 71; K. Pleune

56; Kandolph 66; Keed 63; Thomas 708; Van Roland 74.)

29

. . . In order for the State to convict under §2087.5,

Miss. Code 1942, Rec., the following elements must be

present: (1) There must be a crowding or congregat

ing with others; (2) defendant must be in a place of

business engaged in selling or serving members of the

public . . . ; (3) there must be an order given to dis

perse or move on by a law-enforcing officer of a mu

nicipality or county; (4) the order must be disobeyed;

and (5) the intent to provoke a breach of the peace,

or the existence of circumstances such that a breach

of the peace may be occasioned thereby.

The record in this case reflects the following: (1)

the defendant entered the terminal building in Jackson,

Mississippi, on the day in question in the company of

others; (2) the terminal is a place of business engaged

in serving or selling to members of the public; (3) an

officer of the Jackson Police Department ordered de

fendant to move on out of the area; (4) the defendant

refused to obey the officer’s orders and (5) the wit

nesses testified that at the time the defendant and his

companions entered the station, the crowd of people

already there became antagonistic toward defendant;

that if the officer had not acted in ordering defendant

to move on, there would have been violence (App.

p. 12a).

The court concluded:

In the case at bar the defendant not only knew the

situation but he came to the South for the deliberate

purpose of inciting violence, or, as he put it, “ for the

purpose of testing the Supreme Court decision in re

gard to interstate travel facilities.” He left a trail of

violence behind him in Alabama. The jury was, there

fore, warranted in finding that he intended to create

disorder and violence in Jackson, and that, in fact,

30

disorder and violence were imminent at the time when

Thomas refused to obey the police officer’s order to

move on (App. p. 14a).

# # # #

. . . We hold that the constitutional rights of defen

dant were not violated by his conviction for disorderly

conduct. The state’s interest in preventing violence

and disorder, which were imminent under the undis

puted facts, is the vital and controlling fact in this

case. If the defendant had been denied the exercise

of his right to enter the white waiting room, or to

assemble for the purpose of exercising the right to

protest or of free speech, his argument would be perti

nent. But defendant is in no position to claim that he

was merely exercising a constitutionally guaranteed

right, for it is manifestly true that he and his associ

ates participated in a highly sophisticated plan to

travel through the South and stir up racial strife and

violence. All of their activities were broadcast in a

manner to create the greatest public commotion and

uneasiness. When defendant and his companions

reached Jackson, the police had notice of all that had

transpired in Alabama. There is no evidence that the

police did anything other than keep the peace. They

did not deny defendant the right to enter the white

waiting room and were willing and ready to escort

defendant anywhere he wanted to go. This Court can

not escape the duty to accord to the police the authority

necessary to prevent violence, and this is true what

ever the motives of those who are about to cause the

violence, or to precipitate it. In the situation the police

found themselves, it was reasonable to require defen

dant to move on to wherever he wanted to go (App.

p. 26a).

31

In Farmer the court held that the circumstances “were

such that a breach of the peace was likely as a result of

the presence of the appellants and those congregated with

him,” and in Knight the court again found that the evi

dence supported petitioner’s conviction for disorderly con

duct. The remaining cases were affirmed without opinion,

merely citing Thomas and Farmer.

Following judgment in the State Supreme Court, sug

gestions of error were filed alleging, in essence, that:

(1) no evidence supported the convictions;

(2) the ordinance under which they were tried and con

victed is unconstitutionally vague and failed to warn them

of the conduct proscribed;

(3) the arrests and convictions were based upon a policy

of racial discrimination required by city ordinance; and

(4) the convictions violated Article 1, Section 8, Clause

3 in that petitioners were deprived of the right to travel

on a racially desegregated basis in interstate facilities.

Suggestions of error were overruled pursuant to which

this petition for writ of certiorari is filed.

32

Reasons for Granting the Writ

The decisions of the Mississippi Supreme Court conflict

with applicable decisions of this Court on important con

stitutional issues.

I.

Petitioners’ Convictions Offend Due Process Because

Based on No Evidence of Guilt.

Petitioners, white and Negro interstate travelers, were

convicted under a disorderly conduct statute, which pun

ishes :

Whoever, with intent to provoke a breach of the peace,

or under circumstances such that a breach of the peace

may be occasioned . . . crowds or congregates with

others in . . . any place of business engaged in selling

or serving members of the public . . . and refuses to

disperse or move on, when ordered so to do by any

law enforcement officer . . .

That petitioners had a clear right to use bus and train ter

minal facilities in the City of Jackson, Mississippi, on a

racially unsegregated basis is indisputable, Boynton v. Vir

ginia, 364 U. S. 454; Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903;

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373; Bailey v. Patterson, 369

U. S. 373; 49 U. S. C. §316(d); 49 C. F. R. §180(a) (1)-(10)

(I. C. C. regulations prohibiting racial segregation in

terminal facilities serving interstate passengers), and un

disputed. Despite this clear right, however, and despite

petitioners’ entirely lawful attempts to exercise this right,

they were immediately arrested in the City of Jackson by

police officers who awaited their arrival in the terminals,

and were convicted. In Thomas, the Mississippi Supreme

Court held that “ the evidence shows that the officer arrested

the defendant in good faith, under reasonable apprehension

of an imminent breach of the peace” and that “ [t]he State’s

33

interest in preventing violence and disorder, which were

imminent under the undisputed facts, is the vital and con

trolling fact in this case” (App. p. 26a).

This holding is patent error. It flies in the face of the

records in these cases as well as repeated decisions of this

Court. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, affirming 257 F. 2d

33, 38-39 (8th Cir. 1958); Watson v. Memphis, 373 U. S.

526; Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284; Buchanan v. Warley,

245 U. S .60.

In its opinion the Supreme Court of Mississippi stated

that:

. . . In order for the State to convict under §2087.5,

Miss. Code 1942, Rec., the following elements must be

present: (1) There must be a crowding or congregat

ing with others; (2) defendant must be in a place of

business engaged in selling or serving members of the

public . . . ; (3) there must be an order given to dis

perse or move on by a law-enforcing officer of a mu

nicipality or county; (4) the order must be disobeyed;

and (5) the intent to provoke a breach of the peace, or

the existence of circumstances such that a breach of the

peace may be occasioned thereby.

The record in this case reflects the following: (1) the

defendant entered the terminal building in Jackson,

Mississippi, on the day in question in the company of

others; (2) the terminal is a place of business engaged

in serving or selling to members of the public; (3) an

officer of the Jackson Police Department ordered de

fendant to move on out of the area; (4) the defendant

refused to obey the officer’s orders and (5) the wit

nesses testified that at the time the defendant and his

companions entered the station, the crowd of people

already there became antagonistic toward defendant;

that if the officer had not acted in ordering defendant

to move on, there would have been violence (R. Thomas

777-78).

34

The evidence in these cases clearly fails to meet the re

quirements for a finding of guilt under this statute. Not

only is the sole evidence of “ crowding or congregating” the

simple fact that petitioners arrived in groups,19 these rec

ords are barren of any indication that petitioners either

intended to provoke a breach of the peace or that a breach

of the peace was likely from their actions.

These petitioners did nothing unlawful. Captain of Police

Ray and other prosecution witnesses agreed that petitioners

were entirely peaceful and quiet at all times while in bus

and train terminals in the City of Jackson, Mississippi.

Not a single disorderly or violent act occurred in any ter

minal at any time.20 Indeed, Ray testified that he feared no

violence from petitioners. While an estimated “ crowd” of

white people were present in the terminals upon petitioners’

19 Indeed, several petitioners were arrested while sitting' or stand

ing alone or with a few other persons (R. Knight 247; McDonald

67; Van Roland 42).

20 Q. The time you ordered defendant and his companions to

leave, was there any act of violence up to this moment?

A. Nothing other than their presence there by which a

breach of the peace might have occasioned (R. Thomas 587).

# # * * *

Q. So the only disorderly act, if you can call it that, in the

waiting room, that you saw after the arrival of the defendant

and his companions, saw anywhere in the bus terminal, was

the refusal to leave—your order to leave the station?

A. That was the only arrest made there. That was the only

disorderly conduct that happened at that time (R. Thomas

599-600).

In Davidov, Ray testified on cross-examination:

Q. Now, Captain Ray, I believe you testified that prior to

this, and at this time, this defendant had said or had done

something to indicate that it was his purpose to create a dis

turbance. 1 mean, he had done nothing, or he had said noth

ing, or he made no gestures that indicated that he intended

to create a disturbance ?

A. No, his presence there was what created a disturbance.

Q. But he didn’t do anything ?

A. No, he didn’t (R. Davidov 30, 31).

35

arrival, numerous police officers were present to “maintain

law and order.” 21 The sole basis for petitioners’ arrest was

their mere “ presence.” 22

In each case Ray testified that he had “ advance notice”

of petitioners’ arrival, and was present at the terminals to

preserve “ law and order.” 23 In each case he stated that a

21 Ray gave estimates of between 35 and 50 people as present

in and around the terminals besides petitioners. However, a num

ber of newspapermen were included in this number. Moreover,

Ray’s testimony is weakened by an article written by Shoemaker,

a reporter for the Jackson Daily News and a prosecution witness

in several cases, who wrote that “only a few persons watched from

the sidewalk a few blocks away” (R. Thomas 543). And petitioner

Van Roland testified that when he arrived at the Greyhound bus

terminal, the police were the only persons present, while Ray spoke

of a “crowd.”

22 On another occasion C. R. Keyes of the Jackson Police De

partment testified:

Q. In other words, he was not doing anything different from

the other people who came in prior to his arrival that would

cause disturbance in there ?

A. Nothing, only his presence.

Q. Only his presence ?

A. That is correct (R. McDonald 33).

23 The principal evidence relied upon by the Court was Captain

of Police Ray’s testimony that he “ definitely believed there would

have been possibly a riot or some disturbance, and that possibly

bloodshed would have taken place” (emphasis added). The records

here utterly belie any such contention.

Ray and the Court also relied heavily upon the fact that some

of the petitioners had met with violence in Alabama. From this

the Court concluded in Thomas :

“ In the case at bar, defendant not only knew the situation but

he came to the South for the deliberate purpose of inciting

violence, or, as he put it, ‘for the purpose of testing the Su

preme Court decision in regard to interstate travel facilities.’

He left a trail of violence behind him in Alabama. The jury

was, therefore, warranted in finding that he intended to create

disorder and violence in Jackson, and that, in fact, disorder

and violence were imminent at the time when Thomas refused

to obey the police officer’s order to move on” (App. p. 14a).

The Court also pointed to the riots accompanying the attempt of

James Meredith to enroll at the University of Mississippi as evi

dence that a race riot might have ensued from petitioner’s presence.

However the Meredith case came after petitioners’ arrests.

36

“ crowd” was in the terminal which became in an “ugly and

angry mood” and began “moving towards” petitioners. Yet

Ray at no time spoke to the “ crowd” or ordered them to

move back or out of the terminals.24

Evidence of an “ imminent breach of the peace” is ren

dered even less credible in view of the numerous police

officers present when petitioners arrived in the City of

Jackson. Ray expressed confidence on several occasions

that he had everything under control, as did other prosecu

tion witnesses.25

That this evidence utterly fails to establish any conduct

by petitioners which constitutes a crime is patently clear,

and conviction under these circumstances is a manifest

denial of due process under the Fourteenth Amendment.

Thompson v. Louisville, 363 TJ. S. 199; Taylor v. Louisiana,

370 U. S. 154; Garner v. Louisiana, 368 TJ. S. 157; Wright

24 In Perlman, Ray testified:

Q. What was the disposition of the people who were in the

waiting room when the defendant came in ?

A. After this defendant and her group entered, they be

came in an ugly and angry mood, moved toward this defen

dant, started mumbling to each other and that’s—

Q. Do you know, pardon me—

A. And that’s when I determined the cause of the trouble

and felt it necessary at that time to remove that cause and

ordered her to leave.

Q. Did you talk to any of these people ?

A. At that time ?

Q. At that time.

A. At that time, I did not (R. Perlman 23).

25 Dabbs, a reporter for the Clarion Ledger, testified on cross-

examination :

Q. And the police had the situation outside on the street

as much under control as inside the terminal?

A. I would say so, yes.

When the first two buses arrived at the Greyhound terminal, Ray

had approximately 75 police officers in and around the station,

along with three police dogs. The “crowd” consisted of between

35 to 50 persons (R. Thomas 566; Bevel 19; Farmer 21).

37

v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284. Mere “presence” of Negroes or

of Negroes and whites together in a public place is no

crime, Garner, supra, nor is failure to obey the command of