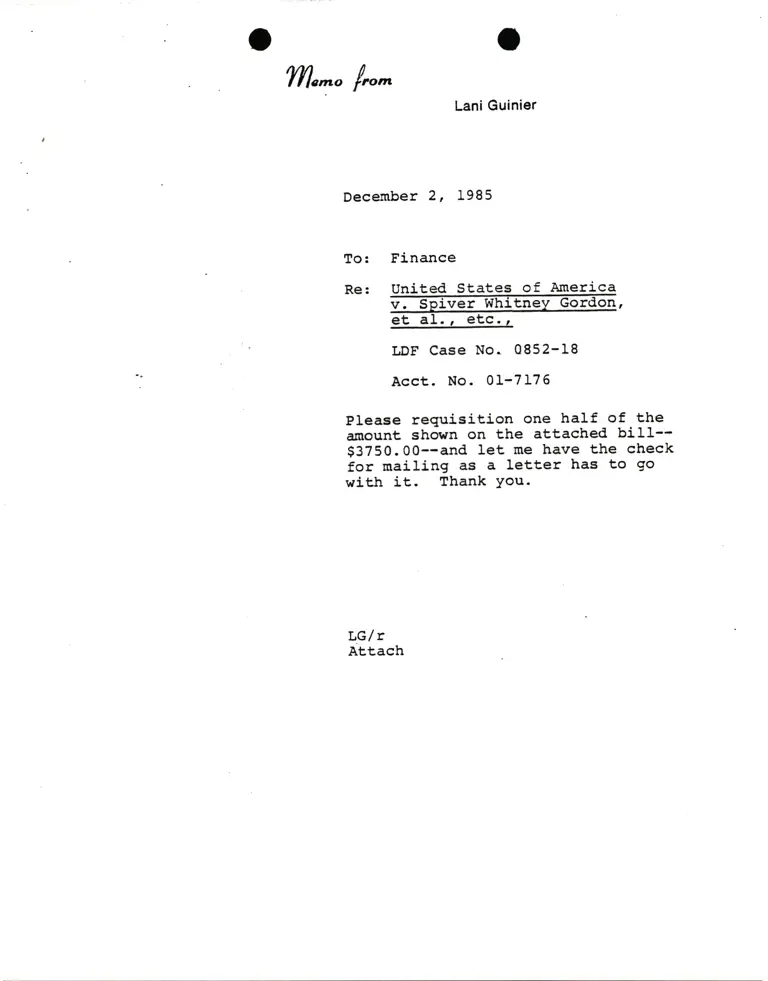

Memorandum from Lani Guinier to Finance Re United States v. Spiver Gordon

Administrative

December 2, 1985

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Memorandum from Lani Guinier to Finance Re United States v. Spiver Gordon, 1985. 4dbd6058-e792-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0e5bea5d-8548-4fa2-82a1-ebd0b4c5947b/memorandum-from-lani-guinier-to-finance-re-united-states-v-spiver-gordon. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

f/l,^o /nn

Lanl Gulnicr

Dccember 2, 1985

8o:

RE:

FLnance

LDf Cate No. 0852-18

lcct. No. 01-7176

P1carc regukltlon one halt of tha

uount rhovn on the attachcd bl'11--

$3750.00--and lct nc bave ttrc chsck

for naillng ae a lcttar bar to go

wlth it. thank You.

l"G/ x

ittach