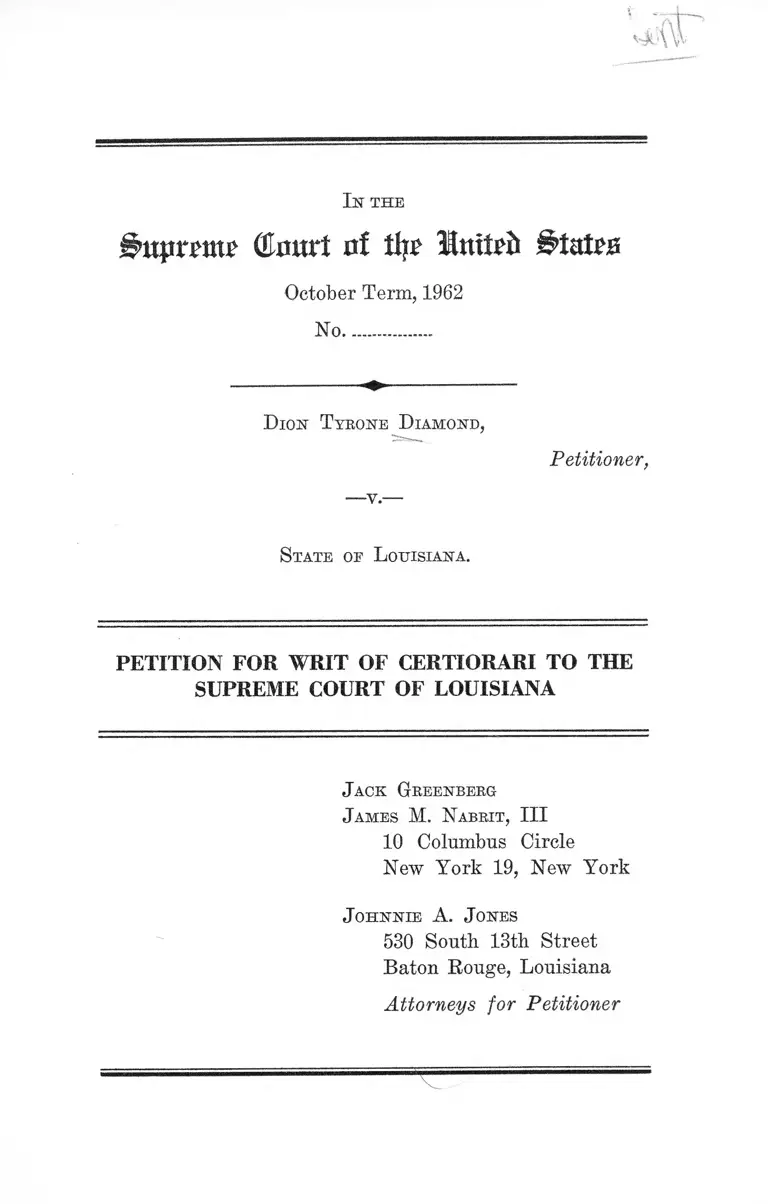

Diamond v. Louisiana Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Louisiana

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Diamond v. Louisiana Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Louisiana, 1963. 620606d1-af9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0e5e84d0-3d05-4237-a900-2ea3baf78035/diamond-v-louisiana-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-louisiana. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

ĵ upmnp GImtri nt tip Unitpfr States

October Term, 1962

No................

In the

D ion T ybone D iamond,

Petitioner,

— y.—

State oe L ouisiana.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF LOUISIANA

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabr.it, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

J ohnnie A. J ones

530 South 13th Street

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Attorneys for Petitioner

I N D E X

PAGE

Citation to Opinions Below .............. .......................... 1

Jurisdiction ................................................................... 2

Question Presented ............................ 2

Statutory and Constitutional Provisions Involved .... 2

Statement ..................................................... 4

How the Federal Questions Were Presented ............ 11

Reasons for Granting the Writ ................................. 17

Conclusion ........................................................................... 24

A ppendix ................................. la

T able op Cases

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 .................. 17,18, 21

Chaplinski v. New Hampshire, 315 IT. S. 568 ........... 22

Cramer v. United States, 325 U. S. 1 ......................... 23

Edwards v. South Carolina, —— U. S. — —, 9 L. ed.

2d 697 .....................................................................17,18, 21

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157 .............. 18,19, 20, 21, 22

N. A. A. C. P. v. Button,------U. S. ------- , 9 L. ed.

2d 405 .......................................................................... 17

Ponchatoula v. Bates, 173 La. 824,138 So. 851........... 21

11

PAGE

State v. Sanford, 203 La. 961, 14 So. 2d 778 .............. 21

Stromberg y. California, 283 U. S. 359 .................. 17, 22, 23

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154............................. 19

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 ............................. 21, 22

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516................................. 23, 24

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U. S. 199........... 19

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 ..........................18, 21, 22

Williams v. North Carolina, 317 U. S. 387 .................. 23

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507 ......................... 17

Yates v. United States, 354 U. S. 298 .......................... 23

In the

(tart itf % Initrii States

October T erm, 1962

No.................

D ion Tyrone D iamond,

—v.—

State oe L ouisiana.

Petitioner,

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF LOUISIANA

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Louisiana entered

in the above entitled case on January 3, 1963.

Citation to Opinions Below

The opinions below are not reported. The Nineteenth

Judicial District Court for the Parish of East Baton Rouge

filed a series of per curiam opinions ruling upon the peti

tioner’s bill of exceptions which were dated November 8,

1962 (R. 23-41), and are printed in the appendix hereto at

p. 3a.

The Supreme Court of Louisiana entered an order deny

ing the applications for writs of certiorari, mandamus and

prohibition (R. 206), which is unreported but is set forth in

the appendix hereto, infra, p. 25a.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Louisiana was

entered January 3, 1963 (R. 206). The jurisdiction of this

Court is invoked under 28 U. S. C., §1257(3), petitioner

claiming rights, privileges and immunities under the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

Question Presented

Whether, where petitioner engaged in making speeches—

an activity within the area of free expression protected by

the Constitution—he was denied due process under the

Fourteenth Amendment when punished under a state law

containing general and indefinite prohibitions against dis

turbing the peace which are not narrowly drawn to define

and prohibit specific conduct?

Statutory and Constitutional

Provisions Involved

1. This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

2. This case also involves Louisiana Revised Statute,

14:103 which provides as follows:

§103. Disturbing the peace

A. Disturbing the peace is the doing of any of the

following in such manner as would foreseeably disturb

or alarm the public:

(1) Engaging in a fistic encounter; or

(2) Using of any unnecessarily loud, offensive, or

insulting language; or

3

(3) Appearing in an intoxicated condition; or

(4) Engaging in any act in a violent and tumultuous

manner by any three or more persons; or

(5) Holding of an unlawful assembly; or

(6) Interruption of any lawful assembly of people;

or

(7) Commission of any other act in such a manner

\ as to unreasonably disturb or alarm the public.

Whoever commits the crime of disturbing the peace

shall be fined not more than one hundred dollars or

imprisoned for not more than, ninety days, or both.

B. Any person or persons, providing however noth

ing herein contained shall apply to a bona fide legiti

mate labor organization or to any of its legal activities

such as picketing, lawful assembly or concerted activity

in the interest of its members for the purpose of ac

complishing or securing more favorable wage stand

ards, hours of employment and working conditions,

while in or on the premises of another, whether that

of an individual person, a corporation, a partnership,

or an association, and on which property any store, res

taurant, drug store, sandwich shop, hotel, motel, lunch

counter, bowling alley, moving picture theatre or drive-

in theatre, barber shop or beauty parlor, or any other

lawful business is operated which engages in selling

articles of merchandise or services or accommodation

to members of the public, or engages generally in busi

ness transactions with members of the public who shall:

(1) prevent or seek to prevent, or interfere or seek

to interfere with the owner or operator of such place

of business, or his agents or employees, serving or

selling food and drink, or either, or rendering service

4

or accommodation, or selling to or showing merchan

dise to, or otherwise pursuing his lawful occupation or

business with customers or prospective customers or

other members of the public who may then be in such

building, or

(2) prevent or seek to prevent, or interfere or seek

to interfere with other persons who are expressly or

impliedly invited upon said premises, or with prospec

tive customers coming into or frequenting such prem

ises in the normal course of the operation of the busi

ness conducted and carried on upon said premises, shall

be guilty of disorderly conduct and disturbing the

peace, and upon conviction thereof, shall be punished

by a fine of not more than five hundred dollars or by

imprisonment in the parish jail for not more than six

months, or by both such fine and imprisonment. (As

amended Acts 1960, No. 70, §1.)

Statement

Petitioner, Dion T. Diamond, seeks review of his con

viction of the crime of “disturbing the peace” in the Nine

teenth Judicial District Court of Louisiana, Parish of East

Baton Kouge. Petitioner was charged in that Court by an

information (R. 1) filed March 8, 1962, in case No. 42,917

which alleged that on January 30 and 31,1962, he:

. . . unlawfully did violate L.E.S. 14:103 in that he,

not a student of Southern University, did enter upon

the premises of Southern University and there engage

in and encourage students of Southern University to

hold unruly, unauthorized demonstrations on the

Campus and did lead and encourage said students to

march through the University buildings while classes

were being conducted and did encourage said students

5

to boycott and leave the classes in such manner as

would foreseeably disturb and alarm the public . . .

Petitioner was arraigned and he entered a plea of not

guilty March 8, 1962 (E. 42). On March 12, 1962, the trial

court entered an order, over petitioner’s objection, grant

ing the State’s motion to consolidate this case for trial with

five other separate changes then pending against petitioner

(E. 42). But, eventually) case'No. 42̂ 917 was tried sepa

rately (cf. E. 59), petitioner was convicted only on this

charge, and the present petition thus involves only the

charge quoted above. Petitioner has not been brought to

trial on the other informations, which included allegations

that he violated LSA-E.S. 14:103 by holding unlawful as

semblies and also by interrupting lawful assemblies.1

Before trial petitioner filed an application for a bill of

particulars (E. 9) and a motion to quash the information

(E. 3), both of which were overruled (E. 44). /Trial was

held Mav 8. 1962. and petitioner was found “guilty as

charged” (E. 44) by the Court sitting without a jury. A

motion for new trial (E. 12) was overruled May 24, 1962

(E. 45). In the motion to quash and the motion for new

trail petitioner raised federal constitutional objections as

serting that the statute as applied to him was unconstitu

tionally vague and that it violated his rights to free speech

1 Copies of 3 of the 5 other informations appear in this record

(R. 6-8), having been filed in connection with petitioner’s motion

to quash. Case No. 42,615 alleged that petitioner violated LSA-R.S.

14:1Q3 by holding unlawful assemblies, and No. 42,616 alleged a

violation of the same statute by interrupting lawful assemblies.

Case No. 42,612 charged that petitioner violated LSA-R.S. 14:103.1,

by refusing to leave the premises of Southern University when

requested to do so by authorized University personnel. All three

informations related to the period January 29 through February 1,

1962. Other pending informations charged petitioner with va

grancy under LSA-R.S. 14:107 and with trespass under LSA-R.S.

14:63.

6

and assembly, as is set forth in more detail below, p. 11,

et seq.

Petitioner was ̂ sentenced to pay a fine of $100 and costs,

or in default of the fine, to be confined in the parish jail

for 30 days, and, in addition, to be confined in the parish

jail for 60 days (E, 45).

On November 8, 1962, the trial court filed a series of per

curiams to petitioner’s bills of exceptions (E. 23-41).

Thereafter, on or about November 21, 1962, petitioner ap

plied to the Supreme Court of Louisiana for writs of

certiorari, mandamus and prohibition seeking to invoke

the court’s supervisory powers (E. 195). The writs were

denied January 3, 1963, in an order by the Supreme Court

of Louisiana stating (E. 206) :

The application is denied. We find no error in the

rulings complained of.

Execution of the judgment was stayed for 90 days on

January 10, 1963, to allow petitioner to seek review in

this Court (E. 209).

The events leading to petitioner’s arrest were as follows.

Southern University in East Baton Eouge Parish Louisiana

is a school having about 4400 students (E. 128). The school

had been the scene of a series of demonstrations and meet

ings by students from abouty December 15, 1961 until the

time of petitioner’s arrest on February 1, 1962 (E. 89).

Some students at Southern were boycotting classes until

the situation of students who had been arrested in anti

segregation demonstrations was resolved with the school

(E. 130, 133, 134). Dion T. Diamond, who was not a student

at Southern University, was first observed on the campus

by the State’s witnesses (University employees) on Janu

ary 30, 1962. The evidence at the trial related to a series

7

of speeches made by Diamond to students in a quadrangle

on the campus on January 30 and 31, 1962. There was also

evidence as to the circumstances of his arrest on February

1, 1962. phere was no evidence that petitioner was ever

ordered not'“fo enter the campus, or to leave it, and no

evidence’thaf he was ever told that he could not make

speSeE^tortir^eaMpus or that he_needed any permission

£o~dro su. The UlirvergtfyTeglstrar testified that the school

was a' public institution, and that “ anyone may come there

who wishes” (E. 7).

1. Events of January 30, 1962.

Between 9 :30 and 10:00 A.M. Diamond was seen by the

Dean of Students Marvin Harvey (R. 113). Diamond was

talking to three to four hundred students in a quadrangle

near the student union building (R. 113). Dean Harvey

said that Diamond was “talking about the importance of

demonstrating and staying out of classes” (R. 113). After

about 15 minutes the meeting broke up and the students

went in various directions (R. 114). The Dean stated that

during the speech the students were listening, clapping

and indicating “ expressions of approval” (R. 115). The

Dean said that he had not authorized Diamond to have a

meeting (R. 115).

That afternoon at about 1:00, Dean Harvey observed

about 40 students walking around the campus with signs

(R. 115-116).2

2 A defense witness, Jeanette Gilliam, a former student at

Southern, said that she was present at a speech made by Diamond

in the same area at about 12 :00 noon on the 30th. None of the

State’s witnesses mentioned this speech. Miss Gilliam stated that

Diamond asked students to stay out of classes, but that he did not

advocate students going into classrooms and taking students out

of classes (R. 179-181).

8

2. Events of January 31, 1962— morning.

Diamond made another speech at the same place at a

time variously estimated at 9 :15 to 9 :45 A.M. before a

group estimated by the school’s chief security officer Wil

liam Pass at two to three hundred (R. 66) and estimated

by Dean Harvey at four to five hundred (R. 116). Pass

stated that this was a regular school day, but that students

at that time had been boycotting classes on the campus for

three or four days (R. 66; 96). In his speech Diamond told

the students not to go to classes; that the faculty was sup

porting them and had signed some type of petition; and

that they should show their gratitude by not going to

classes (R. 68). Dean Harvey said that the tenor of the

speech was the same as that of the previous day (R. 117);

that he had not authorized the meeting (R. 117); that it

lasted between 15 and 20 minutes (R. 117); and that he

started toward Diamond to inform him that he did not have

permission to hold the meeting, but that Diamond ceased

speaking and the group dispersed before he got there (R.

116-117).

3. Events of January 31, 1962— afternoon.

Security officer Pass and his assistant Willie Harris

testified about a speech Diamond made during the noon

hour on January 31. Harris estimated that five to six

hundred students were there (R. 149); Pass stated there

were about the same number or possibly more than were

at the morning speech, e.g., two to three hundred (R. 69).

Pass stated that “Diamond told the students that we will

go through the classrooms and if necessary wrn will put

them out of the classrooms” (R. 71). Harris said that Dia

mond was pleading for more followers from the student

body (R. 155); that he urged the students to stay out of

classes and was calling for at least fifty percent of the stu

9

dents to support him (E. 155); and that Diamond told the

students “let’s go through the classrooms” (E. 156). Dean

Harvey described this speech by saying that it “ concerned

principally the boycotting of classes” (E. 118).

According to Dean Harvey, about one hour after this

speech he observed at least a hundred students begin to go

from one classroom building to another carrying signs;

that this was a noisy procession which disturbed people

in the buildings where classes were being conducted at the

time; and that this lasted over half an hour (E. 118-119).

Mr. Pass said that the students were walking on the campus

and through the classrooms singing and stomping in a

very loud manner which caused a disturbance for over an

hour (E. 71-72); that they carried signs (E. 73-76); and

that classes in progress were disturbed (E. 72-73). His

assistant, Harris, also recounted this event saying that the

students were “pulling on doors, stomping on the halls”

(E. 155); and that they were disturbing the classes (E.

155). No witness testified that anyone was actually “pulled”

from any classroom. Pass testified that no one was injured

and that there were no fights (E. 110).

None of the witnesses testified that Diamond did any

thing but make the speeches mentioned above. No witness

testified that Diamond entered any University building.

Pass and Harris both stated that they did not see Diamond

in any of the buildings (E. 92; 156). No witness testified

that Diamond carried any signs or participated in making

them (cf. E. 88). On cross examination Pass was asked

(E. 95):

Q. Now, what did the accused do other than to make

a speech? A. That is all I witnessed him doing. He

just made a speech.

10

4. Events of January 31, 1962— evening.

At about 6:00 P.M. on January 31 an official meeting of

the student senate was held in the “ old gymnasium”, at

which Dean Harvey announced that this was the only au

thorized student meeting, and the president of the student

senate, Murphy Jackson, spoke urging the students to go

to classes. Murphy Jackson testified that Diamond sought

permission to speak, but when this was refused Diamond

left the meeting without causing any trouble (R. 174); that

Diamond asked students who wanted to have an “ outcry”

not to disturb the meeting and to be quiet or to leave

(R. 175). Dean Harvey said that when Diamond left the

meeting about 125 students also left (R. 124). Shortly

afterwards there was an impromptu outdoor gathering out

side the “new gymnasium” at which Diamond and a number

of students spoke (R. 124-125, 186). Defense witnesses tes

tified that on this occasion Diamond reprimanded the stu

dents for reportedly having gone through the classroom

buildings that afternoon (R. 181, 183, 186-187).

5. Events of February 1, 1962.

On the morning of February 1, Diamond arrived on the

campus in a taxicab with several other persons (R. 188-

189). As soon as he got out of the taxicab he was placed

under arrest by Willie Harris, the assistant security officer

who was also a deputy sheriff (R. 87, 107-108, 144). Harris

was accompanied by Chief Security Officer Pass who drove

the two of them to Raton Rouge jail. Pass and Harris

both stated that on this occasion they merely observed

Diamond getting out of the taxicab and that Harris imme

diately placed him under arrest. Harris had no arrest

warrant (R. 145). Harris stated that he had wanted to

arrest Diamond on the previous day during the noon

speech, but had been unable to reach him because of the

11

crowd (E. 153). He stated that he arrested Diamond for

“holding an unlawful assembly” the previous day (E. 148);

and that no one told him to make the arrest (E. 153). Pass

denied having ordered or requested Harris to make the

arrest, or having made the arrest himself (E. 106).

How the Federal Questions Were Presented

The federal questions sought to be reviewed here were

raised in the trial court on March 23, 1962, by petitioner’s

Motion to Quash the information (E. 3-5). In this motion

petitioner objected that the statute under which he was

charged was unconstitutionally vague and that it infringed

his right of free speech in violation of the Constitution of

the United States asserting, inter alia:

2. That LSA-E.S. 14:103 of 1950, as amended, should

be declared void for vagueness, in that, said Statute

is so vague on its face that one can not reasonably be

expected to know what conduct is prohibited which

could form the basis for a criminal prosecution.

3. That said Statute is so vague in its application

as to violate the due process clause to the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States of

America.

# * * # #

7. That the said Bill of Information is insufficient

to charge a crime under the provisions of LSA-E.S.

14:103 of 1950, as amended, except that the Statute be

unconstitutional under the Constitution of the State of

Louisiana and, as applied, violative of freedom of

speech and assembly guaranteed to defendant by the

First Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States of America and a denial of due process and

equal protection of the laws clauses as guaranteed to

12

defendant by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States of America, of which he

is a citizen (R. 3-4).

The motion was argued, submitted and denied on April 9,

1962 (R. 44).

At the conclusion of the trial petitioner was found guilty

as charged (R. 44). Thereafter, on May 23, 1962, petitioner

filed a Motion for New Trial (R. 12-16). In the Motion for

New Trial petitioner again objected that his conviction un

der “a general disturbing of the peace statute” violated his

rights of free speech as protected by the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution. In the Motion for New Trial

petitioner asserted, inter alia:

2. That the said verdict is contrary to the law and

evidence in that the evidence adduced on the trial of

this cause clearly establishes that the defendant, on

January 30 and 31, 1962, merely made speeches in

protest of racial segregation to a small group of college

students assembled in front of the Student Union Build

ing on the campus of Southern University whereby he

encouraged the students to stay out of classes in sup

port of the freedom movement protesting racial segre

gation in the Baton Rouge community, the activity

being not proscribed by a general disturbing of the

peace statute, except depriving the defendant of his

constitutional protections guaranteed by the First and

Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution of the

United States of America.

4. That the said verdict is contrary to the law and

evidence in that the evidence adduced on the trial of

this cause clearly .establishes that the defendant, as

did others, between ^December 15, 1961 and February 1,

13

1962, made many speeches or public addresses on the

campus of Southern University and to its student body

urging or encouraging the students of said University

to stay out of classes in protest of racial segregation

and in support of the freedom movement in which

students of the various Negro colleges and universities

throughout the nation and particularly in the Southern

States were participating; and that, to sustain a verdict

of guilty in such case made and provided violates the

defendant’s freedom of speech accorded by the First

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States of

America and, furthermore, denies him due process of

law and equal protection of the laws guaranteed by

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States, the evidence being such that it is im

practicable to determine specifically who was respon

sible for the actions of the students of Southern Uni

versity who participated in the freedom movement

demonstrations. The defendant being not charged with

conspiracy can not be held accountable for malicious

acts of others, if there were any such acts.

# # # # #

6. That the said verdict is contrary to the law and

evidence in that the evidence adduced on the trial of

this cause clearly establishes that the defendant did not

conduct himself in any way which disturbed or tended

to disturb the peace. However, the defendant, on Janu

ary 30 and 31, 1962, did make speeches in front of the

Student Union Building on the campus of Southern

University encouraging the students of Southern Uni

versity, a segregated institution for Negro college stu

dents, to protest (as a unified student body) racial seg

regation in the Baton Rouge community; that such

activities in which the defendant engaged does not con

stitute a violation of a disturbing the peace Statute,

14

except depriving defendant of freedom of speech, due

process of law and equal protection of the laws guaran

teed the defendant, a citizen of the United States, by

the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the Consti

tution of the United States of America.

# # # # #

8. That the said verdict is contrary to the law and

evidence in that it is repugnant to and in violation of

Article 1, Sections 2 and 3 of the Constitution of Louisi

ana of 1921, and also repugnant to and in violation of

the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the Consti

tution of the United States of America; that said ver

dict deprives the defendant of his freedom of speech,

liberties, privileges, immunities, due process and equal

protection of the laws as guaranteed by the provisions

of the Constitution of the State of Louisiana and of the

United States of America, respectively (R. 12, 13, 14,

15).

The Motion for New Trial was overruled May 24, 1962

(R. 45).

Petitioner filed a Bill of Exceptions (R. 17-22) objecting

to the overruling of the Motion to Quash (Exception No. 1)

and the overruling of the Motion for New Trial (Exception

No. 9). The trial court wrote a per curiam to Bill of Excep

tion No. 1 (R. 23-26). A portion of the per curiam dealing

with the petitioner’s vagueness objection is as follows

(R. 24-25):

In Paragraph 2 of the motion to quash defendant

urges that the statute (LSA-R.S. 14:103, as amended)

should be declared void for vagueness, in that no one

could reasonably be expected to know what conduct is

prohibited. The statute sets forth six different specific

acts, disjunctively, any one of which, if done in such a

15

manner as foreseeably would disturb or alarm the

public, constitutes the crime. Sub-section 7 covers the

commission of any other act in such a manner as to

unreasonably disturb or alarm the public. The Supreme

Court of Louisiana in the case of Town of Ponehatoula

v. Bates, et al., 173 La. 824, 138 So. 851, upheld the

constitutionality of a town ordinance denouncing the

crime of disturbing the peace which read in part: “ It

shall be unlawful for any person within the corporate

limits of the Town of Ponehatoula to engage in a fight

or in any manner disturb the peace.” The court held

that it was not necessary that the ordinance define the

offense for the reason that no better definition for the

offense could be found than that contained in the ordi

nance itself. The Supreme Court of Louisiana cited

this case in denying writs in the case of Louisiana v.

Jannette Hoston, et ah, No. 35,567 on the Criminal

Docket of the Nineteenth Judicial District Court and

the two cases consolidated with it. See also these cases

reported in 82 Supreme Court Reporter 248 wherein

the court did not pass upon the constitutionality of the

statute involved.

Paragraph 3 of the motion to quash alleges that the

statute is so vague in its application as to violate the

due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States of America. On

the hearing on the motion no evidence was introduced

by the defendant to show that the statute was being

applied in such an alleged unconstitutional manner.

The portion of the opinion rejecting petitioner’s free

speech objection was as follows (R. 26):

Article 7 of the motion to quash alleges that the bill

of information is insufficient to charge a crime under

LSA-R.S. 14:03 of 1950, as amended, “ except that the

16

Statute be unconstitutional under the constitution of

the State of Louisiana” and, as applied, is violative of

freedom of speech and assembly guaranteed to defen

dant by the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the

Constitution of the United States of America. This

court felt that the bill of information as drawn did

sufficiently charge the commission of a crime under the

statute and that the statute was constitutional. As to

the manner in which it was being applied no proof was

introduced by the defendant at the hearing on the

motion to show that it was being applied in any un

constitutional manner.

In overruling petitioner’s Motion for New Trial the court

stated with respect to petitioner’s constitutional objections

that “ This Court was also satisfied that the statute denounc

ing the crime is constitutional” (R. 40). Petitioner again

asserted his constitutional objections in the “Applications

for Writs of Certiorari, Mandamus and Prohibition,” etc.

filed in the Supreme Court of Louisiana (R. 195-202). Peti

tioner asserted, inter alia:

5. That the Honorable Court aquo erred in over

ruling relator’s Motion for New Trial; that the evi

dence adduced on the trial of this cause clearly estab

lishes that relator, on January 30 and 31, 1962, merely

made speeches in protest of racial segregation to a

small group of college students assembled in front of

the Student Union Building on the campus of Southern

University whereby he encouraged the students to stay

out of class in support of the freedom movement pro

testing racial segregation in the Baton Rouge commu

nity, the activity being not proscribed by a general

Disturbing of the Peace Statute, except depriving re

lator of his constitutional protections guaranteed by

17

the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the Consti

tution of the United States of America (R. 196-197).

Petitioner made similar constitutional objections raising the

free speech defense in paragraphs 6, 8, 9, 10 and 11 of the

petition.

The Supreme Court of Louisiana denied this application

on January 3,1963 (R. 206).

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

The Decision Below Conflicts With Decisions o f This

Court in That Petitioner Was Convicted for Engaging in

His Constitutionally Protected Right o f Free Speech

Under a Law Too Vague and Indefinite to Conform to the

Fourteenth Amendment’ s Requirements o f Due Process.

This Court has demanded strict standards of statutory

specificity when criminal laws touch upon the area of free

speech and expression, because “ First Amendment freedoms

need breathing space to survive.” N.A.A.C.P. v. Button,

------U. S. ——, 9 L. ed. 2d 405, 417-418; Winters v. New

York, 333 U. S. 507; Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296,

311; Edwards v. South Carolina,------U. S .------- , 9 L. ed. 2d

697, 702-704; Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359, 369.

The statute under which petitioner was convicted sweeps

within its ambit and punishes a great variety of conduct,

including the constitutionally protected area of speech and

expression, “under a general and indefinite characteriza

tion, . . . leaving to the executive and judicial branches too

wide a discretion in its application,” Cantwell v. Connecti

cut, supra (310 U. S. at 308). If conduct, such as petition

er’s series of speeches to student groups on the Southern

University campus, can be regulated and punished at all, it

can only be reached under a law “narrowly drawn to define

18

and punish specific conduct as constituting a clear and pres

ent danger to a substantial interest of the State.” Cantwell

y . Connecticut, supra (310 U. S. at 311); Edwards v. South

Carolina, supra; Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, 202

(concurring opinion); Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88,

105./Since nothing in the statute under which petitioner was

convicted (LSA-E.S. 14:103) represents a legislative judg

ment that the specific conduct of petitioner alleged in the

bill of information or proved at the trial should be pro

hibited, the conviction offends due process under the prece

dents cited above./

It is readily evident that the entire case against petitioner

hinges upon things that he said rather than upon any non

verbal act. This is clear from the information which charges

a series of activities, each of which includes a component of

speech. It is charged that petitioner did “ engage in and

encourage students . . . to hold unruly, unauthorized dem

onstrations,” and did “ lead and encourage . . . students to

march . . . ” etc., and did “ encourage . . . students to boycott

and leave the classes . . . ” (R. 1; emphasis supplied). And

both the evidence and the court’s statement of the basis of

the finding of guilt make clear that the conviction rests on

petitioner’s speeches.3 Although the information charged

3 In ruling upon Bill of Exception No. 7 relating to the over

ruling of defendant’s motion for a directed verdict, the court de

scribed the basis of its finding of guilt as follows (R. 37) :

“ The court overruled the motion for the reason that the

state, in the opinion of the court, had sustained its burden of

proving the guilt of the defendant beyond a reasonable doubt.

Reliable, competent evidence offered by the state showed that

the defendant, a non-student, was present on the campus of

Southern University on the dates alleged in the bill of in

formation, and while there did, in speeches made by him in

meetings not authorized by those in charge of such matters,

encourage and exhort Southern University students to boycott

classes and to march into the classrooms while classes were in

session and to disrupt the classes, even to the extent of pulling

the students from the classrooms, in such a manner as would

foreseeably disturb and alarm the public.”

19

that petitioner did “ engage in” and “ lead” as well as “ en

courage” the demonstrations and the march through the

University buildings, the trial court regarded petitioner’s

speeches as sufficient to sustain the charge, on the theory

that counseling others to do an act was equivalent to doing

it personally (R. 34). Certainly the conviction cannot val

idly rest on the premise that petitioner did anything beyond

speaking—for there is no evidence of any such acts. Thomp

son v. City of Louisville, 362 U. S. 199; Garner v. Louisiana,

368 U. S. 157; Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154.

The statute, therefore, must be measured against the

strict standards of permissible vagueness which are ap

plicable in the area of free speech. The inquiry in the

present case is complicated by the fact that the record does

not indicate what part or parts of LSA-R.S. 14:103 peti

tioner was found to have violated. Neither the prosecution

nor the trial court expressly indicated which part of the

law was relied upon for the charge or the conviction (R. 23).

But defense counsel assumed, with reason, that the charge

was pursuant to LSA-R.S. 14:103A(7).4 This assumption

was made explicit in the motion for new trial and the court’s

per curiam did not state that it was erroneous.5 * The as

4 Section 14:103A(7) provides as follows:

“ 103. Disturbing the peace

A. Disturbing the peace is the doing of any of the following

in such manner as would foreseeably disturb or alarm the

public:

(7) Commission of any other act in such a manner as to

unreasonably disturb or alarm the public.”

5 The motion for new trial asserted that the verdict was “con

trary to the law and the evidence” in that petitioner did not “ en

gage in any activity that had been denounced as a crime by

LSA-R.S. 14:103(7) of 1950, as amended, the Statute under which

the defendant was charged” (R. 12). The per curiam stated

(R. 40) :

“ The motion for a new trial alleges that the verdict is contrary

to the law and the evidence. The Court heard all the evidence

on the trial of the case and was convinced of the guilt of the

accused beyond a reasonable doubt.”

20

sumption that §14:103A(7) is the basis of the charge is

reasonable because none of the matters charged in the in

formation are readily identifiable as relating to any sub

section of the statute other than this “ catch-all” provision.

Subsections A (l) , A (3) and the entire subsection B are

quite obviously not involved since nothing in the charge or

the evidence is even remotely related to the activities men

tioned therein.6 There is almost equally scant reason to

think that the conviction was founded upon any of the

remaining subsections—A (2), A (4), A (5) or A (6)—since

there was no allegation or evidence of “ loud, offensive or

insulting language” or of “violent and tumultuous” conduct

by petitioner, and since whatever is meant by “holding . . .

an unlawful assembly” and “ interruption of any lawful as

sembly,” separate informations charging these offenses

were, and still are, pending against petitioner. However,

because there may be some basis, however slight, for a

tenuous contention that one or more of these subsections

is involved, this possibility is dealt with in the subsequent

part of this argument below at pp. 23-24. For the present,

the argument is addressed to the far more likely possibility

that the trial court regarded the case, as petitioner did,

i.e., as founded upon LSA-R.S. 14:103A(7).

This provision is the same law which was considered by

this Court in Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157.7 The ma

jority in Garner, supra (368 U. S. at 162, 163, 166, note 13)

found it unnecessary to decide the vagueness and free

speech claims, but these claims were fully discussed in and

6 Subsections A ( l ) and A (3) deal, respectively, with fistic en

counters and intoxicated persons. Subsection B relates to inter

ferences with certain types of businesses.

7 LSA-R.S. 14:103 was amended in 1960 after the trial in

Garner, to add what is now part B, but the law considered by

this Court in Garner, Sec. 14:103(7) remains and is the same as

the present Sec. 14:103A(7).

21

formed the basis of, the concurring opinion by Mr. Justice

Harlan (368 U. S. at 196, et seq.). In Justice Harlan’s

view, this law was unconstitutionally vague as applied in

all three of the factual situations presented in Garner and

the cases consolidated with it (368 U. S. at 205). As that

opinion made clear, the catch-all provisions of this law

prohibiting “ any other act [done] in such a manner as to

unreasonably disturb of alarm the public,” gives a defen

dant “no warning as to what may fairly be deemed to be

within its compass” (368 U. S. at 207).

In this case (R. 25), as in Garner, the Louisiana courts

have referred only to the definition of disturbing the peace

given in an earlier case, Ponchatoula v. Bates, 173 La. 824,

827, 138 So. 851, 852, where it was said to include “any act

or conduct of a person which molests the inhabitants in the

enjoyment of that peace and quiet to which they are entitled,

or which throws into confusion things settled, or which

causes excitement, unrest, disquietude, or fear among per

sons of ordinary normal temperament.” Indeed, to support

its holding on the vagueness issue, the trial court even relied

upon the Louisiana Supreme Court’s ruling in Garner and

its companion cases (R. 2 5 ) It is obvious, then, that this

case does involve’~a“vague"’and generalized conception of

“disturbing the peace” ; that the law has not been limited by

construction ;s and that the law is applied here as it was in

Garner to conduct within the area of speech and expression, t

This Court’s opinions teach that such convictions deny due

process. Cantwell v. Connecticut, supra; Thornhill v. Ala

bama, supra; Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1; Edwards

v. South Carolina, supra. 8

8 The Louisiana Supreme Court itself questioned the validity of

an earlier general “ disturbing the peace” law applied to religious

expression on vagueness grounds in State v. Sanford, 203 La. 961,

14 So.2d 778.

22

\

</'it is submitted that petitioner’s advocacy that students

voluntarily attending a public University refuse to attend

classes as a form of protest was a form of speech on public

issues which a state cannot prohibit, whatever may be one’s

view of the social utility of such a speech.9 T-erminiello v.

Chicago, supra. The information and the court’s per curiam

(E. 37) make it clear that petitioner was charged and con

victed for this lawful advocacy and for allegedly urging

that students march into classroom buildings and disrupt

classes. Cf. Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359. But

even if some or all of petitioner’s speech could validly be

prohibited by the State, it cannot be punished under a vague

and general law such as LSA-R.S. 14:103A(7), which is as

readily applicable to protected speech as it is to that which

is not within the bounds of lawful advocacy, as, for example,

“ fighting words” (see Chaplinski v. New Hampshire, 315

U. S. 568). The law denies due process because “by its

terms [it] appears to be as applicable to ‘incidents fairly

within the protection of the guarantee of free speech,’

Winters v. New York, supra (333 U. S. at 509), as to that

which is not within the range of such protection.” Garner

v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. at 207 (concurring opinion). Peti

tioner need not bear the burden of showing that the State

could not have passed another, more specific, law to reach

his conduct. Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88, 97, 98.

Previously, in the petition, we adverted to the possibility

that the conviction might be attempted to be justified under

some portions of the statute other than subsection A(7).

Actually, each of these other subsections is equally vague

and indefinite as applied to petitioner’s conduct, giving no

9 The reasons for the student boycott of classes are not explained

in the record except for a reference to “certain situations” con

cerning other students “who had been arrested several weeks pre

viously” for “ taking part in antisegregation demonstrations”

(R. 130-133).

23

specific warning that this type of speech is prohibited in

the circumstances of the case. To the extent that the law

touches on the subject of expression, i.e., in terms of “un

necessarily loud, offensive or insulting language” and acts

done in a “violent or tumultuous manner by three or more

persons,” there is no fair warning that petitioner’s speech

could be so regarded. But given the vagueness of subsec

tion A (7), and the obvious possibility that it was the basis

of conviction, a consideration of the vagueness of these

other portions of the law may well be pretermitted.

Under the doctrine of Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S.

359, 368, if it cannot be known from the record whether

or not a defendant was convicted under an unconstitution

ally vague portion of a law7 affecting free speech, the con

viction cannot stand because of the indeterminate possibility

that it was premised on another portion of the law not

subject to the same infirmity. In Stromberg the Court,

noting that the defendant had been convicted under a gen

eral jury verdict which did not specify which of three statu

tory clauses it rested on, concluded that “ if any of the

clauses in question is invalid under the Federal Constitu

tion, the conviction cannot be upheld” (283 U. S. at 368).

The principle wras followed in Williams v. North Carolina,

317 U. S. 387, 292, where the Court said:

To say that a general verdict of guilty should be upheld

though we cannot know that it did not rest on the

invalid constitutional ground on which the case was

submitted to the jury, would be to countenance a pro

cedure which would cause a serious impairment of

constitutional rights.

See also Cramer v. United States, 325 U. S. 1, 36, note 45;

Yates v. United States, 354 U. S. 298, 312; Thomas v. Collins,

323 U. S. 516, 529. Here as in Stromberg, supra, there is

24

a clear and obvious possibility that the conviction was based

upon an impermissibly vague portion of the law. Neither

the accusation, the verdict, nor anything else in the record

makes it certain that this conclusion is erroneous. The

fact that the trier of the facts in Stromberg was a jury

and in this case was a judge does not represent a significant

distinction, as Thomas v. Collins, supra, demonstrates.

Since petitioner was charged with violation of LSA-R.S.

14:103, and given a single penalty for violating the law,

which was upheld in its entirety, it follows that a deter

mination that any part of the law denies due process must

impair the entire conviction.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully submitted

that the writ of certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

J ohnnie A. J ones

530 South 13th Street

Baton Rouge 2, Louisiana

Attorneys for Petitioners

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

Minutes o f Court Dated May 8, 1962

NINETEENTH JUDICIAL DISTRICT COURT

Criminal Section

No. 42,917

[ same tit l e ]

Honorable Fred S. LeBlanc, Judge presiding, was opened

pursuant to adjournment.

This case came on for trial in accordance with previous

assignment, the accused, charged with violation of L.R.S.

14:103, being present in court represented by counsel. On

motion of counsel for the accused, the court ordered a

sequestration of witnesses in this case. Evidence was intro

duced, the case argued and submitted, and the court, for

oral reasons assigned, found the accused guilty as charged,

to which verdict counsel for the accused excepted and asked

that a formal bill be reserved. Counsel for the accused gave

notice in open court to the court and opposing counsel of

his intention to apply to the Supreme Court of Louisiana

for writs of certiorari, mandamus and prohibition.

The court denied the request of counsel for the accused

to release the accused on his old bond, and set a new bond

for the accused pending sentence in the amount of $700.00.

Sentence deferred until May 24, 1962.

2a

Minutes o f Court Dated May 24, 1962

NINETEENTH JUDICIAL DISTRICT COURT

Criminal Section

[ same tit l e ]

Honorable Fred S. LeBlanc, Judge presiding, was opened

pursuant to adjournment.

The motion for new trial previously filed herein was

argued, submitted, and the court, for oral reasons assigned,

overruled the motion for new trial, to which ruling of the

court counsel for the accused excepted and asked that a

formal bill be reserved.

The accused, having previously been tried for violation

of L.R.S. 14:103 and found guilty of said violation, was

present in court represented by counsel. The accused was

brought before the bar for sentence. Whereupon, the court

sentenced the accused to pay a fine of $100.00 and costs,

or in default of payment thereof to be confined in the parish

jail for thirty days, and in addition thereto to be confined

in the parish jail for sixty days, to which sentence counsel

for the accused excepted and asked that a formal bill be

reserved.

Counsel for the accused gave notice to the court and to

the Assistant District Attorney in open court of his inten

tion to apply to the Supreme Court of Louisiana for writs

of certiorari, mandamus and prohibition, and requested that

the accused be released on his present bond. The court

ordered the accused released on his present bond, and

granted counsel for the accused until June 22, 1962 during

which to apply to the Supreme Court for writs.

3a

19TH JUDICIAL DISTRICT COURT

P arish of E ast Baton R ouge

State of L ouisiana

Per Curiam to Bill of Exception No. 1

[ same title ]

--------------------— ---------------------

Tlie application for a bill of particulars was denied by

the court for the reason that the information sought by

the defendant did not pertain to the nature of the charge.

LSA-R.S. 235. It will be noted that the defendant in his

application did not call upon the district attorney to spe

cify under which sub-section of LSA-R.S. 14:103 he was

proceeding. The bill of information charges a violation of

R.S. 14:103 and sets forth all the facts upon which the

state was relying for a conviction. The state is not re

quired to furnish to the defendant the evidence it intends

to introduce to obtain a conviction. Likewise, the law does

not require the state to supply the names of any witnesses

to the defendant.

When the court rendered judgment denying defendant’s

application for a bill of particulars defendant objected to

the ruling of the court and reserved a “ formal” bill of

exception, “ and asked that the motion, the bill of informa

tion all be made a part of the record * * *. ” Defendant did

not request that the ruling of the court be made a part of

the Bill of Exception. Moreover, he did not specify the

ground of his objection and did not make that ground a

part of his Bill of Exception. Defendant’s Bill of Excep

tion does not have incorporated within it any of these mat

4a

ters and there is nothing attached to it. LSA-E.S. 15:498-

499.

In objecting to the ruling of the court counsel for the

defendant in reserving his Bill of Exception asked that the

motion for a bill of particulars and the bill of information

be made a part of the “ record”—not a part of the Bill of

Exception. The bill of information and the application for

a bill of particulars were already part of the record. No

part of the record becomes a part of the Bill of Exception

unless it is incorporated therein or attached thereto and

made a part thereof.

The motion to quash the bill of information was over

ruled by the court. In Paragraph 1 of the motion to quash

defendant contends that the bill of information amounts

to a multiplicity of charges growing out of the same inci

dent or occurrence, yet he does not claim that the bill of

information is faulty on the ground of duplicity. In fact,

he alleges “ that said alleged acts could only constitute a

single crime * * *. ” The state contended that under the

authority of LSA-E.S. 15:222 it had the right to cumulate

the acts of the defendant in one count, since it was ap

parent that they were connected with the same transaction

and constituted but one act and that it had charged them

conjunctively in the bill of information. Defendant, as

pointed out above, conceded that the acts of the defendant

constituted but one crime. This court was of the opinion

the state’s position was correct. State v. Morgan, 116 So.

(2d) 682, 238 La. 829; State v. Amiss, 89 So. (2d) 877,

230 La. 1003. Accordingly, the court overruled the motion

to quash the bill of information on this ground of attack.

In Paragraph 2 of the motion to quash defendant urges

that the statute (LSA-E.S. 14:103, as amended) should be

Per Curiam to Bill of Exception No. 1

5a

declared void for vagueness, in that no one could reason

ably be expected to know what conduct is prohibited. The

statute sets forth six different specific sets, disjunctively,

any one of which, if done in such a manner as foreseeably

would disturb or alarm the public, constitutes the crime.

Sub-section 7 covers the commission of any other act in

such a manner as to unreasonably disturb or alarm the

public. The Supreme Court of Louisiana in the case of

Town of Ponchatoula v. Bates, et al., 173 La. 824, 138 So.

851, upheld the constitutionality of a town ordinance de

nouncing the crime of disturbing the peace which read in

part: “ It shall be unlawful for any person within the cor

porate limits of the Town of Ponchatoula to engage in a

fight or in any manner disturb the peace.” The court held

that it was not necessary that the ordinance define the

offense for the reason that no better definition for the

offense could be found than that contained in the ordinance

itself. The Supreme Court of Louisiana cited this case in

denying writs in the case of Louisiana v. Jannette Hoston,

et al., No. 35,567 on the Criminal Docket of the Nineteenth

Judicial District Court and the two cases consolidated with

it. See also these cases reported in 82 Supreme Court

Reporter 248 wherein the court did not pass upon the con

stitutionality of the statute involved.

Paragraph 3 of the motion to quash alleges that the

statute is so vague in its application as to violate the due

process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States of America. On the hearing

on the motion no evidence was introduced by the defendant

to show that the statute was being applied in such an

alleged unconstitutional manner.

Article 4 of the motion to quash alleges as a fact that

there was no disturbance of the peace by the defendant

Per Curiam to Bill of Exception No. 1

6a

within the definition of the crime. This court took the posi

tion that the bill of information charged a crime under the

statute and that it would not be known whether the defen

dant committed the crime charged until after the state had

put on its case.

Article 5 of the motion to quash alleges that the statute

was being unconstitutionally applied because the defendant,

a member of the Negro race, has been heretofore engaged

in activities protesting racial segregation and had lately

come to Southern University to resume Ms collegiate work

there as a student; that when he attempted to speak out in

the cause of justice and freedom he was arrested and jailed.

On the trial of the motion to quash the defendant offered

no proof to establish these alleged facts.

Article 6 of the motion to quash sets forth a conclusion

to the effect that the use of the criminal processes of the

State of Louisiana in the manner described in paragraph 5

of the motion denies and deprives the defendant of his

rights, privileges, immunities and liberties guaranteed to

him by the due process and equal protection of the law

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States of America. In this connection, the

defendant on the hearing of the motion offered no proof

to show that defendant’s constitutional rights had been

violated in the manner described.

Article 7 of the motion to quash alleges that the bill of

information is insufficient to charge a crime under LSA-

R.S. 14:03 of 1950, as amended, “ except that the Statute

be unconstitutional under the constitution of the State of

Louisiana” and, as applied, is violative of freedom of

speech and assembly guaranteed to defendant by the First

and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution of the

United States of America. This court felt that the bill of

Per Curiam to Bill of Exception No. 1

7a

information as drawn did sufficiently charge the commis

sion of a crime under the statute and that the statute was

constitutional. As to the manner in which it was being

applied no proof was introduced by the defendant at the

hearing on the motion to show that it was being applied in

any unconstitutional manner.

Respectfully submitted at Baton Rouge, Louisiana, this

8th day of November 1962.

Per Curiam to Bill of Exception No. 1

F red S. L eB lanc

Judge, 19th Judicial District Court

Filed Nov. 8 1962

(Signed) Betty B ady

Dy. Clerk

A True Copy Nov. 8, 1962

(Signed) B etty B ady

Dy. Clerk

8a

19TH JUDICIAL DISTRICT COURT

P arish of E ast B aton R ouge

State of L ouisiana

Per Curiam to Bill of Exception No. 2

[ sam e t it l e ]

This Bill of Exception was reserved to the ruling of the

court overruling defendant’s objection to the testimony in

corporated in the Bill of Exception. The basis of the ob

jection was that the testimony of this witness should not

be considered by the court because no explanation had

been made as to wliat a security officer is, as to whether or

not he is a peace officer or sheriff. The court considered

the objection to be premature, and informed counsel for

the defendant that he could develop this point on cross-

examination. As a matter of fact, the witness on direct

examination later explained that he was not a peace officer

and that his duties as security officer consisted of maintain

ing the safety of the faculty staff, the administrative body

and students of Southern University, as well as the prop

erty of the university.

I wish to point out that counsel for the defendant in

resserving his Bill of Exception used these words: “ To

which ruling, Your Honor, I except and ask that a formal

bill be reserved.” Counsel did not at that time request that

the facts upon which the objection and ruling were based

be made a part of the Bill of Exception, nor did he move

that the objection, the ruling and the reasons for the ruling

be made a part of the Bill of Exception. It is the judgment

9a

of this court that the Bill of Exception was improperly re

served. LSA-R.S. 15:499-500.

Respectfully submitted at Baton Rouge, Louisiana, this

8th day of November 1962.

Per Curiam to Bill of Exception No. 2

F eed S. LeB lanc

Judge, 19th Judicial District Court

Filed Nov. 8, 1962

(Signed) B etty B ady

Dy. Clerk

A True Copy Nov. 8, 1962

(Signed) Betty B ady

Dy. Clerk

10a

19TH JUDICIAL DISTRICT COURT

P arish or E ast B aton R ouge

State op L ouisiana

Per Curiam to Bill of Exception No. 3

[ same t it l e ]

After the state’s witness, William Pass, answered the

question set forth in this Bill of Exception, counsel for the

defendant objected to any testimony about the signs “be

cause there is nothing on those things to identify that the

accused had the placards made or that he had anything to

do with them, those could be anybody’s signs.” The court

overruled the objection as being premature, taking the

position that this witness could testify about his familiarity

with the signs. The signs at this juncture were not being

offered in evidence by the state. It was the position of the

court that it would give the state the opportunity to show,

if it could, that there was some connection between the

signs and the defendant in this case. Later, the state was

able to show by the testimony of this witness that he ob

tained some signs on the date of the alleged offense from

Barracks B on the campus of Southern University and that

a group of students from the university were carrying

those signs, or similar signs, when they were marching on

the campus and into four buildings thereon where classes

were in progress after being encouraged by the defendant

to go into the classrooms and disrupt the classes.

In reserving this Bill of Exception counsel for the defen

dant did not comply with the requirements of the law. LSA-

R.S. 15:498-15:499. He merely excepted to the ruling in the

11a

following words: “ To which ruling I except and ask that

a formal bill be reserved.” Although the minute clerk at the

time of the reservation of the Bill of Exception took down

the facts upon which the objection and the ruling were

based, together with the objection, the ruling and the rea

sons for the ruling conformable to LSA-R.S. 15:499, coun

sel for the defendant, as stated above, did not request that

this be done.

Respectfully submitted at Baton Rouge, Louisiana, this

8th day of November 1962.

Per Curiam to Bill of Exception No. 3

F eed S. L eBlanc

Judge, 19th Judicial District Court

Filed Nov. 8, 1962

(Signed) B etty B ady

Dy. Clerk

A True Copy Nov. 8, 1962

(Signed) B etty B ady

Dy. Clerk

12a

19TH JUDICIAL DISTRICT COURT

P arish of E ast B aton R oijgb

State of L ouisiana

Per Curiam to Bill of Exception No. 4

[ same title]

After the testimony recited in this Bill of Exception the

state offered in evidence some of the signs which had been

identified by the witness as being the signs, or similar signs,

which the students carried with them as they marched on

the campus of the university and into the classrooms while

classes were in progress, after they were encouraged by

the defendant to disrupt the classes. Counsel for the defen

dant objected to the offering on the ground that the evidence

was immaterial; secondly, that the witness had not testified

that the defendant made the signs, or that the defendant

had any knowledge of the signs being made, or that the

defendant had instructed anybody to make the signs. The

offering was also objected to on the ground that the defen

dant was not being tried for conspiracy and that the de

fendant was not responsible for what the students did,

contending that all that the defendant did was to use free

dom of speech. Objection was also made on the ground

that the state had not laid a proper foundation for the

introduction of the proffered evidence, in that the state

had not accounted for the whereabouts of the signs from

the date of the commission of the crime to the date of the

trial and that it was possible that the signs could have been

altered or changed.

The court permitted the signs (State-1, inscribed: “ This

is a Freedom Line! Don’t Cross It” ; State-2, inscribed:

“Let’s Twist Back to the Dorms. No Classes!!” ; State-3,

13a

inscribed: “ Please Stay Out!! Suppoi't Your Fellow Stu

dents” ; and State-4, inscribed: “ No Class Today, Sorry” )

to be introduced in evidence. The reason for the ruling as

stated verbatim by the court at the time was: “This is not

a case of theft where property has to be identified with that

degree of particularity. This witness has testified where

he found the signs, the students were in the process of

making them there, and he saw either those signs or similar

signs being carried by the students after they had been

exhorted to go into the classrooms and get the students

out of the classrooms, pull them out if necessary. This

accused is charged with engaging in and encouraging the

students to hold unruly, unauthorized demonstrations. Now,

in heeding his words of encouragement it is always admis

sible to show what happened, that the students, being thus

encouraged by the accused, proceeded to stamp and march

and sing and carry these signs, even to the extent, to use

the words of the accused himself, get them out of the class

rooms, pull them out if necessary. Now, under the law there

is a presumption that a man is presumed to know the nat

ural consequences of his act, and I think that this accused,

after so exhorting these students to swing into the class

rooms, to march and to get the students out of there because

the faculty is already behind them, and in effect if they

refused to leave the classrooms to pull them out, and any

thing that these students did thereafter after being en

couraged by this accused to do would be admissible, the

natural consequence.” * * * “ He has said that he either

saw these signs or similar signs being carried by the stu

dents, so I say it is not necessary in this type of case, be

cause if we were trying these students for carrying signs

which violated the law then that would be a different propo

sition, but the students are not being tried, the accused is

being tried for disturbing the peace by urging them to do

Per Curiam to Bill of Exception No. 4

14a

an unlawful thing, break up the classes, and, as I said,

under 432 every defendant is presumed to intend the nat

ural probable consequences of his act, and the law presumes

that after he exhorts them to do what he did do or did tell

them that they would resort to this type of activity, carry

out his words of encouragement to break up the classes be

cause the faculty was behind them and he was seeing to it, or

going to see to it if he could, if the students would cooperate,

to just break up the classes at Southern University so there

wouldn’t be any classes. Now in going about that he pre

sumed the natural consequences of his act, they might sing,

they might march, they might stomp and they might carry

signs, and as long as this witness can say that these are

similar signs that is enough for the court in this type of

procedure, so I overrule the objection.”

In reserving his Bill of Exception counsel for the defen

dant did so in the following words: “ To which ruling we

except and ask that a formal bill be reserved.” This, in

the opinion of the court, did not meet the requirements

of the law. The minute clerk did, however, at the time take

down the facts upon which the Bill of Exception and the

ruling were based, together with the objection, the ruling

and the reasons for the ruling in compliance with LSA-R.S.

15:499.

Respectfully submitted at Baton Rouge, Louisiana, this

8th day of November 1962.

F red S. L eB laxc

Judge, 19th Judicial District Court

Filed Nov. 8, 1962

(Signed) B etty B ady

Dy. Clerk

A True Copy Nov. 8, 1962

(Signed) B etty B ady

Dy. Clerk

Per Curiam to Bill of Exception No. 4

15a

Per Curiam to Bill of Exception No. 5

19TH JUDICIAL DISTRICT COURT

P arish of E ast B aton R ouge

State of L ouisiana

[ same title]

This Bill of Exception was taken by the defendant when

the court overruled defendant’s objection to the testimony

set forth in this Bill of Exception. The basis of the objec

tion was that there had been no testimony that the defen

dant conducted the procession of students on the campus

and into the classrooms. The court overruled the objection

for the reason that it -was up to the court (the court being

the judge of the facts in the case) to determine whether or

not the defendant conducted the procession.

The witness on the stand at the time was Marvin L.

Harvey, Dean of Students of Southern University. As

such, he testified it was his responsibility to grant or refuse

permission for the holding of student meetings on the

campus. He testified that he had not authorized the defen

dant to hold any student meetings on the campus during

the dates in the bill of information. Such unauthorized

meetings were held, he testified, at which the defendant

addressed the students. After the meeting held on the

morning of January 30, 1962 this witness observed that

approximately forty students ŵ ere walking around the cam

pus carrying signs. This occurred about one o’clock that

afternoon. On the following morning the defendant was

addressing an unauthorized meeting of students, estimated

16a

by the witness to be between four and five hundred in num

ber. There was another such meeting of students held be

tween 12:30 and 1 o’clock on that same day, at which the

defendant spoke to the students, and at about the hour of

2 o’clock the same afternoon the students paraded through

the classrooms in a noisy manner carrying signs. In one

of the buildings this witness testified that some students

left classes. The demonstrators numbered about one hun

dred and the demonstration lasted more than thirty min

utes.

When this objection was urged there was already testi

mony in the record from Security Officer William L. Pass

that he saw and heard the defendant speaking to a group

of from two to three hundred students on the campus, at

which meeting he heard the defendant tell the students not

to attend classes, that they should show their gratitude by

not going to classes since the faculty was behind them. At

another meeting of about the same number of students he

heard the defendant tell the group to go to the classrooms

and pull the students therefrom.

Now, one of the meanings of the word “ conduct” is to

“direct in action or course.” It was clear to the court that

the defendant had conducted the procession and demonstra

tion of the students on the campus and in the classrooms.

Under LSA-B.S. 14:24 all persons concerned in the com

mission of a crime, whether present or absent, whether they

directly commit the offense, aid and abet in its commission,

directly or indirectly counsel or procure another to commit

the crime, are principals.

For the reasons given in the other per curiams, the court

is of the opinion that this Bill of Exception was improperly

reserved.

Per Curiam to Bill of Exception No. 5

17a

Respectfully submitted at Baton Rouge, Louisiana, this

8th day of November 1962.

Per Curiam to Bill of Exception No. 5

F red S. L eBlanc

Judge, 19th Judicial District Court

Filed Nov. 8, 1962

(Signed) B etty B ady

Dy. Clerk

A True Copy Nov. 8, 1962

(Signed) B etty B ady

Dy. Clerk

18a

Per Curiam to Bill of Exception No. 6

19TH JUDICIAL DISTRICT COURT

P akish of E ast B aton R ouge

State oe L ouisiana

[ same t it l e ]

This Bill of Exception was taken by the defendant after

the testimony incorporated therein was given by the wit

ness, Marvin L. Harvey, Dean of Students at the university.

Counsel for the defendant, after ascertaining from the

witness that unauthorized meetings on the campus had been

held by students of Southern University on dates prior

to the dates in the bill of information at which speeches

were made, wanted to know from this witness what those

speeches were about. The state objected. The court sus

tained the objection for the reason that it made no dif

ference in the case on trial as to whether the law had been

violated by others prior to the date of the crime charged

in the bill of information. The court felt that whether the

university had taken action as to those offenders was imma

terial in the case at bar. The court was also of the opinion

that it made no difference in the instant case whether the

unlawful processions and demonstrations of the students

on the dates alleged in the bill of information were brought

about solely by the encouragement and exhortation of the

defendant made by him on those dates or whether these

processions and demonstrations were due in part to

speeches that the students had heard from other speakers

on other occasions prior to the date of this offense. The

court took the position that the statute was violated when

19a

the state proved that the defendant had committed the acts

alleged in the bill of information in such a manner as would

foreseeably disturb or alarm the public. Whether the stu

dents who participated in the noisy processions and demon

strations had been impressed by the defendant’s speeches

encouraging and exhorting them to so act was, in the

opinion of the court, immaterial for the reason that such

speeches were of such a nature as to foreseeably disturb

and alarm the public, regardless of the resulting action.

The court had permitted the state to prove the resulting

action for the reason that this defendant was presumed

by law to intend the natural and probable consequences of

his act. LSA-E.S. 15:432.

This court is of the opinion that this Bill of Exception

was improperly reserved for the reasons given in the pre

ceding per curiams.

Respectfully submitted at Baton Rouge, Louisiana, this

8th day of November 1962.

F red S. L eBlanc

Judge, 19th Judicial District Court

Per Curiam to Bill of Exception No. 6

Filed Nov. 8, 1962

(Signed) B etty B ady

By. Clerk

A Time Copy Nov. 8, 1962

(Signed) B etty B ady

Dy. Clerk

20a

Per Curiam to Bill of Exception No. 7

19TH JUDICIAL DISTRICT COURT

P arish of E ast B aton R ouge

State of L ouisiana

[ same tit l e ]

This Bill of Exception was reserved to the action of

the court overruling defendant’s motion for a directed

verdict of acquittal after the state had rested its case in

chief. In his motion counsel for defendant contended that

the state had failed to prove its case, claiming that the

evidence adduced by the state was insufficient to warrant

and/or sustain a conviction of the defendant.

The court overruled the motion for the reason that the

state, in the opinion of the court, had sustained its bur

den of proving the guilt of the defendant beyond a rea

sonable doubt. Reliable, competent evidence offered by the

state showed that the defendant, a non-student, was pres

ent on the campus of Southern University on the dates

alleged in the bill of information, and while there did, in

speeches made by him in meetings not authorized by those

in charge of such matters, encourage and exhort Southern

University students to boycott classes and to march into

the classrooms while classes were in session and to dis

rupt the classes, even to the extent of pulling the students

from the classrooms, in such a manner as would foresee-

ably disturb and alarm the public.

All of the testimony introduced by the state was tran

scribed by the clerk, but counsel for the defendant in