Tate v. Board of Education of the Jonesboro, Arkansas Special School District Appendix-Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

February 10, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Tate v. Board of Education of the Jonesboro, Arkansas Special School District Appendix-Brief for Appellants, 1970. 95fdbebb-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0e72317a-98ce-4bd7-8c9b-742c479650c1/tate-v-board-of-education-of-the-jonesboro-arkansas-special-school-district-appendix-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Copied!

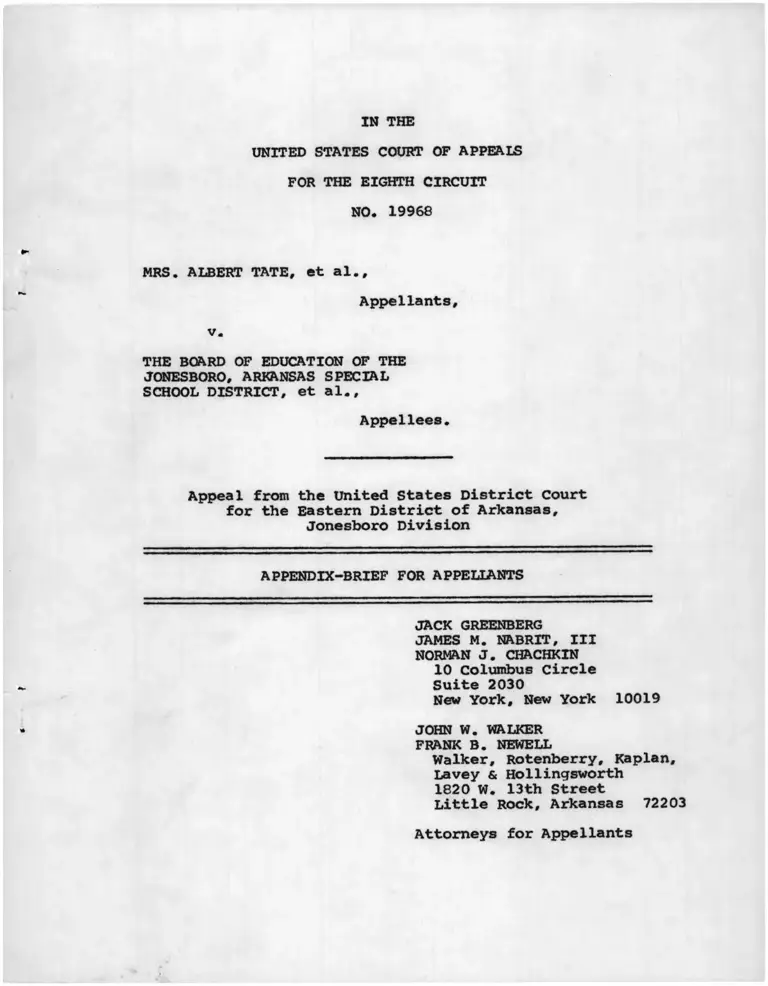

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

NO. 19968

MRS. ALBERT TATE, et al..

Appellants,

v.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE

JONESBORO, ARKANSAS SPECIAL

SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al..

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Arkansas,

Jonesboro Division

APPENDIX-BRIEF FOR APPELIANTS

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030New York, New York 10019

JOHN W. WALKER

FRANK B. NEWELLWalker, Rotenberry, Kaplan,

Lavey & Hollingsworth

1820 W. 13th Street Little Rock, Arkansas 72203

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT....................... -

ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW................. .

STATEMENT................................... .

ARGUMENT:

1. The Court below erred in holding

that appellants' conduct did not

constitute symbolic speech pro

tected by the Free Speech Clause

of the First Amendment to the

Federal Constitution.

2. The Court below erred in holding

that the summary suspension of

appellants did not violate Due

Process.

3. The lower court denied appellants

rights guaranteed by the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment by refusing to enjoin the

playing of "Dixie" at the school

assembly.

CONCLUSION..................................

Page

1

1

2

7

13

18

24

APPENDIX TO ARGUMENT 25

TABLE OF CASES

Pa^e

Barber v. Hardway, 394 U.S. 905 (1969)................ 1,11

Beauharnais v. Illinois, 343 U.S. 250(1951)........ 2,22,23

Blackwell v. Issaquena Board of Education,

363 F.2d 749 (5th Cir. 1965)........................... 1,11

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954 )•■•••••»•..«••.••*.. . ........•*•••••••2*18,19,20,21Brown v. Greer, 299 F. Supp. 595 (1969) .... ...1,11

Brown v. Louisiana, 383 U.S. 131, 142 (1966) .... 1,7

Burnside v. Byars, 363 F.2d 744 (1966).... ........1,8,9,13

Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U.S. 568, 572

(1947)...... ........ .............................2,23

Dickey v. Alabama State Board of Education, 273 F.Supp. 613 (M.D. Ala. 1967).......... .......1,7,9

Dieteman v. Time, Inc. 284 F. Supp. 925

(1968)............................ .................2,22Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Education, 294 F.2d

150, 155 (5th Cir. 1961), cert, denied, 360 U.S.930.................... ..........................1,13,14

Esteban v. Central Mo. State College, 277 F. Supp.

649 (W.D. Mo. 1967).............................. 1,14,17

Frain v. Baron, 38 L.W. 2347 (E.D.N.Y. 1969)........1,10,13

Goldwyn v. Allen, 54 Misc.2d 94, 261 N.Y.S.2d

899 (1967)........................................1,16,17

Green v. County School Board, 391 U„S„ 430 (1968).,.2,18,20

Greene v. Howard University, 271 F. Supp. 609

(D.D.C. 196 )..... ..................................Griffin v. School Board, 377 U.S. 218 (1964)............ 18Hammond v. South Carolina, 272 F. Supp. 947 (1967)......1,8

In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1 (1961)........................ 1, 14

Jones v. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 ( 1 9 6 8 ) . 2 , 2 3 , 2 4

Knight v. State Board of Education, 200 F. Supp.

174 (M.D. Term. 1961)................................1#14

Madera v. Board of Education, 267 F. Supp. 356

(S.D. N.Y. 1967), rev'd on other grounds, 386 F.2d

778 (2nd Cir. 196 ), cert, denied, 390 U.S. 1028

(1968)...............................................1*14

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450 (1968)..2,18

Moore v. Student Affairs Comm, of Troy State

University, 284 F. Supp. 725 (M.D. Ala. 1968).........2,14

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963).....................1,7Raney v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 443 (1968)...... 2,18

Schiff v. Hannah, 282 F. Supp. 381 (W.D. Mich. 1966)...2,14

Soglin v. Kaufman, 295 F. Supp. 978 (1968), aff'd 38

L.W. 2278 (1969)......................... 1,8Tinker v. Des Moines Community School District, 393 U.S.503 (1969).................. ............ ..1,7,9,13

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

372 F.2d 836 (1967)................................. 2,19

- ii -

Page

Wasson v. Trowbridge, 382 F.2d 807 (2nd Cir, 1967).... 2,14

West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette,

319 U.S o 624 (1943)............. .............1,2,9,12,21

Woods v. Wright, 334 F.2d 369 (5th Cir. 1964)......... 2,14

- iii -

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

This is an appeal from the unreported decision of the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of

Arkansas, Hon. Gordon E. Young, United States District Judge,

entered July 23, 1969.

ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

1.

2.

Whether the District Court erred in holding that

appellants' conduct did not constitute symbolic

speech protected by the Free Speech Clause of the

First Amendment to the Federal constitution*

Barber v. Hardway, 394 U.S. 905 (1969)Blackwell v. Issaquena Board of Education, 363 F.Zd

749 (1965)Brown v. Greer, 299 F. Supp. 595 (1969)

Brown v. Louisiana, 383 U.S. 131, (1966)

BURNSIDE v. BYARS, 363 F.2d 744 (1966) _Dickey v* Alabama state Board of Education* 273

F. Supp. 613 (1967)FRAIN v. BARON, 38 L.W. 2347 (E.D.N.Y. 1969)Hammond v. South Carolina State College, 272 F. Supp.

947 (1967)NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963)

SOGLIN v. KAUFMAN, 295 F. Supp. 978 (1968)TINKER v. DES MOINES COMMUNITY SCHOOL DISTRICT, 393

U.S. 503 (1969)West Virginia state Board of Education v. Barnette,

319 U.S. 624 (1943)Wright v. Texas Southern University, 392 F.2d 728

(1968)

Whether the District Court erred in holding that the

summary suspension of appellants did not violate Due

Process:

DIXON v. ALABAMA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION, 294 F.2d

150, .(1961)Esteban v. Central Mo. State College, 277 F. Supp.

649 (1967)GOLDWYN v. ALLEN, 281 N.Y.S.2d 899 (1967)Greene v. Howard University, 271 F. Supp. 609 (1967)

Knight v. State Board of Education, 200 F. Supp. 174

(M.D. Tenn. 1961)In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1 (1961) .Madera v. Board of Education, 267 F. Supp. 356 (1967)

- 1 -

Moore v. Student Affairs Comm, of Troy State

University, 284 P. Supp. 725 (1968)

Schiff v. Hannah, 282 F. Supp. 381 (1966)

Wasson v. Trowbridge, 382 F„2d 807 (1967)

Woods v. Wright, 334 F.2d 369 (1964)

Wright v. Texas Southern University, 392 F.2d 728

(1968)

3. Whether the District Court denied appellants rights

guaranteed by the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment by refusing to enjoin the play

ing of "Dixie" at school assemblies:

Beauharnais v. Illinois, 343 U.S. 250 (1951)

BROWN v. BOARD OF EDUCATION, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

CHAPLINSKY v. NEW HAMPSHIRE, 315 U.S. 568 (1941)

Dieteman v. Time, Inc., 284 F. Supp. 925 (1968)

Green v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 430 (1968)

Griffin v. School Board, 377 U r5. 218 (1964)

Jones v. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968)Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450 (1968)

Raney v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 443 (1968)

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

372 F,2d 836 (1967)West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette,

319 U.S. 624 (1943)

STATEMENT

Procedure:

This action was commenced on November 15, 1968 by the

filing of a Complaint which alleged, inter alia, that

appellees had acted unconstitutionally in suspending minor

appellants for their role in an incident involving the singing

of "Dixie" in school assemblies. The case was decided on

stipulated evidence and pleadings. United States District

Judge Young dismissed the Complaint because, in his view,

there were no federal questions raised. The Court below found1/

that "no racial connotations" (R. 21) were involved in this

case; arguably this finding was intended to dispose of

Reference is to original pagination of Record.

- 2 -

appellants' contentions that they were being denied their

Fourteenth Amendment rights because they were subjected to

an unusually severe punishment. The Court further stated,

at the close of the hearing, that " [t]here are many songs that

I may or may not like; whether I want to get up and march

around or not is something else." (R. 21.) It would appear

that these words were directed at, and intended to dispose of,

appellants' contentions that the practice of singing "Dixie"

as part of a public school exercise contravened the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, and that

their demonstration in opposition to the song was protected by

the First Amendment. With regard to the issue whether the

suspended students were denied Due Process of Law in violation

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, the Court

commented:

School children are subject to dis

ciplinary measures that adults are

not . . . but I find no federal

constitutional principles involved

here.

The District Court's order of dismissal was entered on

July 23, 1967, (A."E") and on August 21, 1969 appellants filed

their Notice of Appeal (A."F") to this Court.

Factual Statement:

The facts of this case are undisputed. They demonstrate

how a school’s unreflective adherence to custom can threaten

the educational process.

- 3 -

The school involved is Jonesboro High School. Recent

desegregation has created a student body racially mixed in a

proportion of roughly 9 to 1, white students predominating.

(R. 8.)

The legal and social climates giving rise to school de

segregation also indicate that a re—evaluation of other old,

accepted policies is in order. It is from the appellees'

failure to appreciate the implications of social change that

the present difficulties arise.

Jonesboro High School, like most schools, recognizes that

extra-curricular activities play an integral part in school

life. With this in mind, numerous such activities are spon

sored by the school. One of the most popular and important

of these is varsity athletics.

Student support for varsity athletics is sought and ob

tained through the medium of pep rallies. These are designed

to arouse the student body to a frenzy of school spirit through

chants and songs, the end in mind being to unify students in

support of the teams.

Traditionally, one of the songs played by the school band

2/

at pep rallies is "Dixie." (R. 8,9.) No protest was heard

when the school was all-white. The last two years, however,

2/ The song "Dixie" was adopted by Jefferson Davis as the

South's national anthem and it was played at his inauguration

as president of the Confederacy.

4

have witnessed increasing resentment of the playing of the

song. Black students see "Dixie" as a relic of slavery ex

pressing a longing that slavery and white supremacy should

return to, if not remain in, the South. School authorities,

well aware of the increasing resentment of black students,

wisely took remedial action. As of September 27, 1968, the

playing of "Dixie" was banned. (R. 10,11.) This affirmative

gesture of good will was almost immediately followed by a

full-scale retreat. Seeking at once to insulate themselves

from criticism by white citizens and to appear "democratic,"

school authorities submitted the matter to a student vote.

The voting being split along racial lines, predictably, the

views of white students prevailed.

On October 25, 1968, three days before the votes were

even counted, school authorities anticipated that black stu

dents would be none too pleased at the election results.

(R. 13,14.) Consequently, students were offered a palliative

in the form of an option of not participating in pep rallies.

They were given leave to go to the auditorium instead, where

they were expected to sit and wait until the rallies ended.

On November 1, 1968, it was announced that "Dixie" would

continue to be a part of the school program. (R. 14,15.)

As it happened, a pep rally was scheduled for November 1,

1968. The school took no position as to whether "Dixie" would

actually be played at this rally or in subsequent ones.

(R. 14,15.)

- 5 -

Consequently, when the rally was held, a number of black

students chose not to participate; but others did. Those who

did not participate went to the school auditorium. Other black

students who chose to attend went directly to the gymnasium,

where, upon entering, they were greeted with "Dixie." Without

even pausing to be seated, appellants turned and quietly ab

sented themselves. (R. 16.) They went directly and peace

fully to the auditorium, located a few feet away in the same

building, which the school had designated as the proper place

for non-participants. (R. 16.)

Had the students presented themselves at the auditorium

originally, no action would have been taken. For changing

rooms instants later, appellants have been made to suffer in

several ways. Appellants were subjected to a five-day sus-

1/pension which was belatedly reduced to three days, Appel

lants were denied participation in school-related functions

during the period of their suspension. A grade reduction of

from six to ten points from their overall daily score for the

entire grading period was imposed. (R. 17,18.) And, finally,

as a condition of reinstatement, appellants were required to

sign statements implying that their peaceful action was

wrongful. (R. 16,17.)

3/ Twenty-two students were readmitted after three days;

five at the end of four days; and three at the end of five

days.

- 6 -

ARGUMENT

1. The Court below erred in holding that appellants1

conduct did not constitute symbolic speech pro

tected by the Free~~Soeech Clause of the First

Amendment to the Federal Constitution.

This issue arises from the disciplinary action taken

against appellants because of the peaceful exit from the pep

rally. We are concerned at this point with whether the peace

ful exodus is symbolic action guarded from suppression by the

Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment to the Federal

Constitution.

Initially, it is clear that appellants are in a position

to assert constitutional claims. "It can hardly be argued

that . . . students . . . shed their constitutional rights to

freedom of speech or expression at the school house gate."

Tinker v. Des Moines Community School District, 393 U.S. 503

(1969).

Equally apparent is the fact that the rights guaranteed

by the First Amendment "are not confined to verbal expression,"

Brown v. Louisiana, 383 U.S. 131, 142 (1966), and extend to

"protect certain forms of orderly group activity," NAACP v.

Button. 371 U.S. 415, 430 (1963).

For example, the Court has upheld protests against the

Vietnam War voiced by students of a public school system as a

valid exercise of their First Amendment rights. Tinker, supra.

See, also, Dickey v. Alabama State Board of Education, 273 F.

Supp. 613 (M.D, Ala. 1967). Although reasonable, narrowly-

- 7

drawn school regulations aimed at maintaining discipline and

order are permissible, "the Fourteenth Amendment protects the

First Amendment rights of school children against unreasonable

rules and regulations imposed by school authorities." Burnside

v. Byars. 363 F.2d 744, 747-48 (1966). See, also, Soglin v.

Kaufman. 295 F. Supp. 978 (1968), aff’d 38 L.W. 2278 (1969);

Hammond v. South Carolina State College, 272 F. Supp. 947

(1967). To prohibit students’ assertion of First Amendment

rights at a public school, school officials must show that the

exercise of the right would "materially and substantially

interfere with the requirements of appropriate discipline in

the operation of the school." Burnside, supra, at 749

(emphasis added).

The test of a reasonable regulation, therefore, is whether

it "measurably contributes to the maintenance of order and

decorum within the educational system." Burnside, supra, at

748 (emphasis added).

Concomitantly, constitutional protection extends to guard

rights infringed pursuant to a rule reasonable on its face but

4/

unreasonably applied.

The most cursory consideration of the present facts in

light of the above standard of reasonableness reveals that

disciplinary action by the school authorities was unwarranted.

4/ The two school rules (A.34 and 35 ) upon which the

appellees rely to justify their disciplinary action are dis

cussed infra, pp.

8

Perhaps a disruptive exit from a classroom would "materially

and substantially" interfere with "appropriate" discipline.

But surely Burnside, Tinker, and Dickey, supra, cannot intelli

gibly be construed to proscribe a quiet procession from the

designed commotion of a pep rally to a place, a few scant yards

away, specifically made available by school authorities.

The students did not disrupt surroundings otherwise

"orderly and decorous." To see the "order and decorum within

the educational system" jeopardized by such mild action re

quires an attitude and imagination which can charitably be

described as rigidly authoritarian.

Neither can the school authorities' disciplinary action be

justified by pointing to any unauthorized presence in a place

declared off-limits during school hours. Appellants were given

the option to be absent from the assembly. The fact that they

chose to exercise their option by a peaceful exodus from the

pep rally certainly cannot justify suspensions varying from

three days to a week.

The appellees and the lower court may consider "silly"

(R. 21) appellants' sensitivity to a symbol of oppression still

not fully lifted. "But freedom to differ is not limited to

things that do not matter much" to the majority condoning them.

West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette. 319 U.S.

624 (1943).

Only recently a Second Circuit District Court had occasion

to protect the First Amendment rights of a few New York City

9

school children who refused to join their class in pledging

allegiance to the United States flag. Frain v. Baron, 38 L.W.

2347 (E.D.N.Y. 1969). The Court there said:

Since no disruption is imminent,

either from spontaneity or from

non-allegiance swearing students’

actions, the students are entitled

to a preliminary injunction pre

venting their suspension from

class or differentiated treatment

from those who participate in the

pledge....

In a word, as a student in a public school cannot be

punished for reasonably and peacefully expressing opposition

to the Vitenam War, neither can he be disciplined for asserting

opposition to school-supported activities reflecting racial

prejudice, and activities calculated to have, or unintentional

ly having, a humiliating impact upon a minority group.

So long as the method by which the pupils assert that

opposition is peaceful and reasonable and the protestation is

unaccompanied by disruptive reactions by other students,

imposition of punishment is impermissible.

The line separating "orderly activity" constituting

peaceful protest from disruptive conduct is not susceptible of

precise and unalterable demarcation. However, on no view of

the facts presented by this record can a case be made out of

disruption warranting punitive action. The conduct here is

poles away from that shown in cases where restraint by school

officials of First Amendment rights has been upheld.

The Supreme Court has recently reaffirmed the distinction

10 -

between peaceful and disruptive student protest activity. In

denying certiorari in Barber v. Hardway, 394 U.S. 905 (1969),

the Court emphasized the importance of determining whether acts

of protest result in disruption. The concurring opinion of

Justice Fortas acknowledges this distinction as follows:

I agree that certiorari should be

denied. The petitioners were sus

pended from college not for express

ing their opinions . . . but for violent and destructive interference

with the rights of others . . . .

[T]he findings of the District Court,

which were accepted by the Court of Appeals, establish that the petition

ers here engaged in an aggressive and

violent demonstration, and not in

peaceful, non-disruptive expression

such as was involved in Tinker . . . .

Id.. at 905 (emphasis added).

In Wright v. Texas Southern University. 392 F.2d 728

(5th Cir. 1968), it was held that students exceeded the bounds

of permissible conduct by physically and verbally abusing a

teacher.

And in Brown v. Greer. 299 F. Supp. 595 (1969) it was held

that the evidence presented sustained the action of a board of

trustees in suspending students who used abusive and

threatening language toward the Superintendent and others,

struck two faculty members and disrupted orderly operation of

school.

Nor is the case at bar comparable to Blackwell v.

Issaquena Board of Education. 363 F.2d 749 (5th Cir. 1965),

where the Fifth Circuit rejected the claim of a group of black

11

students that their right to wear what were loosely termed

"freedom buttons" was protected by the First Amendment. There

the appeals court was careful to note that the wearing of the

buttons precipitated loud and boisterous conduct on the part

of other students, and, therefore, had a disruptive effect on

all school activity.

It should be understood that appellants do not contend

that school authorities are powerless to formulate reasonable

regulations to govern student behavior. But, as the Supreme

Court noted more than a quarter of a century ago, although

school boards have " . . . important, delicate, and highly

discretionary functions," they have "none that they may not

perform within the limits of the Bill of Rights. That they are

educating the young for citizenship is reason for scrupulous

protection of Constitutional freedoms of the individual, if we

are not to strangle the free mind of its source and teach

youth to discount important principles of our government as

mere attitudes." West Virginia State Board of Education v.

Barnette. 319 U.S. 624, 637 (1943).

Appellants urge that this is the test to be applied in

determining whether the school authorities' promulgation,

interpretation and application of the school regulation meets

constitutional requirements: Were the students engaged in an

assertion of speech and association rights; and if so, were

they peacefully and reasonably asserting or exercising these

rights? If they were, any punishment therefor by school

12

authorities contravenes constitutional mandates. The applica

tion of this test, developed by the courts in Tinker, Burnside,

Frain and other cases cited supra, admits of no other conclu

sion but that the Court below erred in refusing to grant

relief from the punitive action of the school authorities here.

2. The Court below erred in holding that the summary

suspension of appellants did not violate Due

Process.

"Whenever a governmental body acts so as to injure an

individual, the Constitution requires that the act be consonant

with Due Process of Law." Dixon v* A labama State Board of

Education. 294 F.2d 150, 155 (5th Cir. 1961) cert, denied. 360

U.S. 930* Although "(t]he minimum procedural requirements

necessary to satisfy Due Process depends upon the circumstances

and the interests of the parties involved."•ibid.. there should

at least be notice and an opportunity to be heard before a

state body imposes a serious sanction.

Whether taking serious action against a student without

allowing him sufficient safeguards is viewed as violating Due

Process because it is an arbitrary act or because his freedom

to go to and from his local school is a liberty which cannot

be withdrawn capriciously or because education has economic

value and is property which may not be seized summarily, it is5/

clear that appellants are entitled to some protection.

The Supreme Court has expressed increasing concern that the

treatment of minors by state authorities be in accordance with

13

Indeed, it has been a proposition of many years standing

our law that a student at a public school could not be expelled

or suspended for a substantial interval without a prior hearing.

See, e.g., Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Education, sup.ra;

Knight v. State Board of Education, 200 F. Supp. 174 (M.D.

Tenn. 1961); Woods v. Wright, 334 F.2d 369 (5th Cir. 1964),

Schiff v. Hannah. 282 F. Supp. 381 (W.D. Mich. 1966) (en banc);

Esteban v. Central Mo. State College, 277 F. Supp. 649 (W.D.

Mo. 1967); Moore v. Student Affairs Comm, of Trov State

University. 284 F. Supp. 725 (M.D. Ala. 1968); Greene v. Howard

University. 271 F. Supp. 609 (D.D.C. 196 ); Madera v. Board.of

Education. 267 F. Supp. 356 (S.D. N.Y. 1967), rev»d on other

grounds. 386 F.2d 778 (2nd Cir. 196 ), cert, denied, 390 U.S.

1028 (1968); Wasson v. Trowbridge, 382 F.2d 807 (2nd Cir. 1967)

Wright v. Texas Southern University. 392 F.2d 728 (5th Cir.

1968),, This is a firmly established legal principle which

presently admits of no doubt.

Appellees seek to justify their action by pointing to a

school regulation which provides as follows;

It is strictly against the rules to create

a disturbance in assembly. (A. 24.)

A second source of justification relied on by appellees is

found in the "Jonesboro Senior High School Teacher Handbook."

5/ continued

Due Process. E0g.# In re Gault. 387 U.S. 1 (196 ). The Court held in Gault €Ea"t"aT€Kough the proceedings there were

civil rather than criminal, the state was required to observe

the Due Process requirement of a hearing.- 14 -

It provides as follows:

The Principal shall be empowered to use

all means that he deems necessary to

maintain discipline at all times, and

shall have the support of the Board, as

long as such means are reasonable and

legal.6/ (A. 34.)

It is manifest on the face of the record that there was not

even the semblance of a hearing before appellants were

suspended. Appellee Sims, after briefly conferring with ap

pellee Geis, decided that the departure of the students from

the assembly was disruptive and merited a five-day suspen-

7/sion. The students were not given notice of the charges

6/

If this regulation is meant to confer authority on the

principal to act according to his unfettered discretion, but to

withhold Board support unless the action is "reasonable," then

the Federal and State Constitutions and the State compulsory

attendance school law (Ark. Stats. Ann. §§80-1502 — 80-1508,

1967 Repl.) require that the regulation be held to be of no

effect. If interpreted to authorise the principal to take

action which is "reasonable and legal," the regulation is in

part logically circular since it supplies a legal standard that

qualifies itself with reference to its own legality. If, as

appellants are willing to stipulate for the purposes of argu

ment, the regulation is meant merely to say that a principal

must act in a reasonable fashion, the regulation still does not

justify appellees' action because the degree of punishment im

posed on the students was a manifestly unreasonable one.

7/

This conclusion flies in the face of the facts, for the

record clearly shows that no "disturbance" contemplated by the

first regulation (A. .) occurred. "Disturbance" may be

taken here to mean "disruption" and there simply was none. Of

course, it may be said that school officials were disturbed by

the peaceful, non-disruptive action of the students — as many

people are disturbed by the fact of school desegregation? but

the regulation may not be read so broadly as to prohibit stu

dents from taking constitutionally protected action for fear of

"disturbing" a school official. Moreover, it is not clear that

the regulation was intended to cover pep rallies. "Assemblies"

15

against them. Nor were they permitted to defend their action,

either individually or as a group. By no stretch of the

imagination can the admittedly brief, impromptu "question and

answer" period (R. 17) — held after suspension was decided

upon -- be considered to have satisfied the requirement of a

hearing.

The requisites of Due Process depend upon the circum

stances. Clearly, school officials have the authority to

discipline unruly students. Further, there is no doubt that a

school may exclude -- either by suspension or expulsion — a

child who is disobedient and disruptive. However, when the

penalties result in the deprivation of important rights, the

elemental requisites of Due Process — notice and a hearing ~

must be observed.

That the practical consequences of the suspensions here

are severe is not to be doubted. Suspension for a full school

2/week and attendant grade reductions clearly had an adverse

affect on appellants' academic progress. For example, a ten

7/ continued

are normally occasions where students are called upon to attend

to speeches or other activities given for their benefit. Con

versely, a pep rally by definition involves the purposeful

creation of a boisterous atmosphere — one full of disturbance

-- which would be intolerable were an assembly being held.

See, generally, discussion, supra, Arugment I.

8/See Goldwyn v. Allen, 54 Misc.2d. 94, 281 N.Y.S.2d. 899

(1967) where it was held that a student subjected to disci

plinary sanctions which affected his grades was entitled to be

represented by counsel at a hearing.

16

per cent (10%) grade reduction reduces a low B to a D, a C to

an P. (It should be noted that there were five more F's

received by appellants for the grading period affected by the

suspension than in the prior grading period. (R. 18,19.))

Such reductions might require an affected pupil to repeat the

subject or perhaps a school year. The financial significance

of such punishment is obvious.

Appellants submit that rudimentary Due Process calls for

9/

the adoption of hearing procedures before students are meted

out punishment such as that imposed in this case. Such a

requirement would not hamper the day-to-day operations of

Jonesboro Senior High School. Nor would it undermine the

authority of those responsible for maintaining discipline at

the school. Formal education takes place not just in class

rooms, but in all of a student's experiences with the school

and its personnel. Constitutional considerations aside, it is

harmful to good education when the entire process of school

suspensions operates in an ad. hoc, arbitrary manner. The loss

of faith by students in the inherent justice and fairness of

the educational system may have serious detrimental conse-r .

9/

Appellants do not here argue that students who face sus

pension are entitled to be represented by counsel at a

disciplinary hearing although several courts have upheld such

a claim. See, e.g., Goldwyn v. Allen, 281 N.Y.S.2d 899 (S. Ct. 1967); Esteban, supra. We do, however, recommend that in a

disciplinary hearing which could result in suspension the

parents of the affected student be included as active partici

pants.

17

quences

3. The lover court denied appellants rights guaranteed

by~the~Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment by refusing to enjoin "the playing of

"Dixie” at the school assembly.

The real issue here is Whether school authorities can

functionally preclude from full participation in the educa

tional process substantially all the students of one race. We

believe that both the letter and spirit of Brown v. Board of

Education. 347 U.S. 483 (1954) demand a negative answer.

Ultimately, Brown stands for the proposition that it is

beneficial for children of all races to attend school together.

Separation of children at this critical point of life operates

as a constitutionally proscribed deprivation. See, for

example, Monroe v. Board of commissioners, 391 U.S. 450 (1968);

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968); Raney v.

Board of Education. 391 U.S. 443 (1968); Griffin v. School

Board. 377 U.S. 218 (1964).

It is apparent that school authorities cannot, consistent

ly with the spirit of Brown, sanction practices which create

barriers, grounded on racial strife, between races sought to

be united. Brown and its progeny require integration of stu

dents, faculties, and staff, and reorganization of the school

system into a unitary body. This must be done without undue

affront or antagonism, on the basis of race, being encouraged

or permitted by the appellees. This constitutional duty was

- 18 -

well-put in United States v. Jefferson County Board of Educa

tion. 372 F.2d 836 (1967). Officials administering public

schools, said the Court there:

[Kjave the affirmative duty under the

Fourteenth Amendment to bring about

an integrated, unitary school system

.... In fulfilling this duty it is

not enough for school authorities to

offer Negro children the opportunity

to attend formerly all-white schools.

The necessity of overcoming the ef

fects of the dual school system ...

requires integration of faculties,

facilities and activities, as well as

students. Id.. at 839.

Further, the essence of Brown and the cases which followed it

is that the Fourteenth Amendment guarantees appellants not

only the right to mere attendance at the same facilities but

also the right to full participation in all aspects of the

educational process. Here, the school has conditioned partici

pation in an important activity on the appellants' ability to

tolerate the expression of sentiments which are morally and

legally abhorrent. In effect, the black student has been told

that he may participate in a particular school activity —

pep rallies — under humiliating circumstances, or bide his

time elsewhere.

Appellants contend that the school authorities' policy

denies them equal participation and, consequently, equal

protection of the laws.

Just as school boards are under a duty to achieve racially

non-discriminatory school systems, so must they strive to

19

achieve integration in intra-school activities.

School boards [must] take whatever

steps might be necessary to convert

to a unitary system in which racial

discrimination would be eliminated

root and branch. Green v* School

Board of New Kent County ̂ 391 U.S.

430, 437-38 (1968) (emphasis added).

The choice offered the students under the plan shares the

constitutional infirmities that condemn tactics employed to

avoid the Brown mandate. Under the arrangement designed by

the school, black students who are offended by the song —

almost all the black students in attendance — are segregated

in the school auditorium, while white students are left alone

to enjoy the pep assemblies in the absence of their black

classmates. The school has thus, albeit indirectly, achieved

the segregation of students that Brown and its progeny pro

hibits. The facts of this case demonstrate that the school's

plan has very effectively segregated the white and black stu

dents at Jonesboro Senior High School. In spite of their

desire to attend the varsity assemblies, appellants here were

forced, upon hearing the insulting and demeaning words of a

song that symbolized to them 250 years of slavery and 100 years

of Jim Crow, to forego participation and segregate themselves

in the school auditorium. The horns of the dilemma which con

fronted black students graphically illustrates the unconstitu

tionality of appellees' action? appellants were put to a choice

between their Fourteenth Amendment right to participate in a

school activity and their right not to be subjected to public,

- 20

officiallv—sanctioned, racial abuse and degradation.

That the song is capable of generating resentment can

hardly be gainsaid. It was even damned by its author when it

10/

was declared the Anthem of the Confederacy in 1861.

The school authorities cannot plead ignorance to the

affront offered, since their initial impulse was to bar the

playing of "Dixie." Neither can they delegate their constitu

tional responsibilities to the students and resolve the issue

by their vote. Appellants' constitutional rights are not

susceptible to such a political process of abrogation.

The very purpose of a Bill of Rights

[and the Equal Protection Clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment] was to

withdraw certain subjects from the

vicissitudes of political controversy,

to place them beyond the reach of

majorities and officials and to

establish them as legal principles to

be applied by the courts... [Funda

mental rights may not be submitted to

vote; they depend on the outcome of

no elections. West Virginia Stat=.

Board of Education v. Barnette, 319

U.S. 624, 638 (1943).

Brown, of course, cannot affect the fact that "Old times

"Jefferson Davis liked the song so much that he adopted it

as the South's national anthem and Dixie was played at his

inauguration as president of the Confederacy at Montgomery,

Alabama, on February 18, 1861.

"By the time the nation struggled in the grips of the

Civil War, "Dixie," born of folk tunes and cradled in the North

as a minstrel song, had become a stirring, martial tune for

the Boys in Gray.

"And Emmett, who once served in the Union Army, said, 'If

I had known to what use they were to put my song. I'll be

damned if I'd have written it.9"

- 21 -

dar am not forgotten" in the private contemplation of many

southerners; but Brown does assure that the spirit of the

"old times" of slavery and white supremacy shall not walk with

institutional approval in our public schools.

Nor is it any answer to suggest that the First Amendment

protects the right of appellants to sing a song whcih cele

brates the darkest era in our nation's history. We cannot

countenance in our public schools officially-sponsored

expression of sentiment which defies the law of the Nation.

Although a claimed First Amendment right must be given the

highest respect and careful consideration by our courts, the

First Amendment cannot be used as a shield to protect practices

which effectively derogate Brown and the constitutional

principles which the Supreme Court sought to establish there.

Other Constitutional rights, like the right to an equal educa

tional opportunity, are equally as important as freedom of

speech.

While the courts may be required under

some circumstances to balance the rights and privileges when the consti

tutional guaranty of freedom of speech

. . . clashes with [other Constitutional

rights,] there would appear to be no

basis to give greater weight or priority

to any one of these Constitutional

guarantees. Dieteman v. Time, Inc., 284

F. Supp. 925 (1968), at 929.

Moreover, the right to free speech does not give rise to

the right to publicly insult or defame, Beauharnais v.

Illinois. 343 U.S. 250 (1951), and the singing of "Dixie," with

22

its ill-disguised overtones of black inferiority and white

superiority, can certainly be taken as one variety of public

defamation. The song does not lose its defamatory character

because it is not directed against any single individual.

Speech which tends to defame black people as a racial group

is not entitled to First Amendment protection. Beauharnais,

supra. "Dixie’s" lines are "insulting [and] fighting words —

whose which by their very utterance inflict injury or tend to

incite a breach of the peace." Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire,

315 U.S. 568, 572 (1947). Indeed, the avowed purpose of the

verse was to urge men on to battle for a cause abhorrent to

our present national ethic. Our courts have never seen fit to

grace such expression with First Amendment protection. Nor is

any exception to the time-honored rule of Chaplinsky and

Beauharnais warranted here.

It is submitted that school authorities cannot constitu

tionally identify themselves spiritually and emotionally with

the fighting anthem of a Confederacy dedicated to the preserva-

11/

tion of the institution of slavery. It creates an intoler-

11/ In another sense, the singing of the anthem of defeated

slave power abridges Constitutional rights, in that it con

stitutes, clearly and unmistakably, a badge of slavery. The

Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, abolishing slavery

and involuntary servitude, and the congressional enactments

grounded on it, were intended to rid the Nation of all such

badges of slavery. See, e.g., Jones v. Mayer Co., 392 U.S.

409 (1968). But, in the words of Mr. Justice Douglas:

- 23 -

able atmosphere of animosity and resentment; it adversely

affects black students' ability to learn and grow. Here, the

insult offered to black students and the resulting estrange

ment of the races are palpable. If racism is to be eradicated,

reason suggests that it not be fostered by the school system.

CONCLUSION

WHEREFORE, for all the reasons above stated, it is

respectfully urged that this Court reverse the Order of the

District Court, with instructions to afford appellants the

following relief:

(1) That Appellees be enjoined from approving the playing of

the tune "Dixie" at school-related affairs or functions;

(2) That Appellees be required to adopt hearing procedures

which accord with Due Process requirements to be applied before

a student is suspended or expelled from school;

(3) That Appellants and all of the members of the class they

represent affected by the acts complained of on the part of

Appellees or their agents be restored to the position or status

11/ continued

Some badges of slavery remain today.

While the institution has been outlawed,

it has remained in the minds and hearts

of many white men. cases which have

come to this Court depict a spectacle

of slavery unwilling to die. Id., at

445.

Nothing could be more manifest than that this song literally

"depicts a spectacle of slavery unwilling to die. The anthem,

a badge of inferior, second-class citizenship and slave status,

is certainly as much a vestige of slavery as the discriminatory

housing practices which were considered violative of Constitu

tional rights in Jones v. Mayer.

- 24 -

they would have had had suspensions not been enforced;

(4) That Appellees be enjoined from interpreting the regula

tions here involved or any other regulation of the school in

such a manner as to prohibit Appellants or any other student

from taking peaceful and non-disruptive action falling within

the protection of the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States;

(5) Any further relief which this Court deems appropriate.

Respectfully submitted.

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030New York, New York 10019

JOHN W. WALKER

FRANK B. NEWELLWalker, Rotenberry, Kaplan,

Lavey & Hollingsworth

1£20 W. 13th Street

Little Rock, Arkansas 72203

Attorneys for Appellants

24a

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I have this 10th day of February,

1970, served a copy of the foregoing Appendix-Brief on

attorney for appellees by depositing a copy of same in the

United States mail, air mail, postage prepaid, addressed

to Mr. Berl Smith, 604 Citizens Bank Building, Jonesboro,

Arkansas 72401.

James M. Nabrit, III

Attorney for Appellants

APPENDIX TO ARGUMENT

1. MEMORANDUM BRIEF FILED BY APPELLANTS IN COURT BELOW

2. RULES OF JONESBORO SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL

25

Irf TUI UNITED STATf S DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTER* DISTRICT OF ARKANSAS

JWSSEORO DXVISIO::

MRS. ALBERT TATE, <?t el.

Plaintlffa, . CIVIL ACTION

V.

.Til” BOARD OF EDUCATION 0? THE

JOSBRUORO, AP.dAiiDAS SPECIAL

GCHOOL .^STRICT, et el..

HO. J-6C-C-43

Deforviar-tu. :

MEMOItViDUK »FlEr OF PLAINTIFFS

Tho facta of this cono ore rather simple. The Jonesboro

High School has apparently denogrogatod or "unified (in a Ioohi*

6bna<;) for several yearn. Negro puyilo attend the Jonesboro

High School and participate In ochool affairs in varying degrees.

As with root schools, there aro a number of extracurricular

activities at the Jonesboro High School, including varsity

athletics. Student support for varsity athletics is often sought

and obtained through the use of 'pap rallies. It is at these

rallios that the pupils and ochool staff do things in their

judgment necessary to show support for the extra-curricular

athletic program. Tho central purpose at theno rallies, of course,

la to unify students in support of the teams. Apparently, for

many yoars vhen Jonesboro nigh School was an all-white school,

tho familiar southern ooag, "Dixie," was played by the school

band at pep rallies. Thin pattern continued until on or about

SoverJ>*r 1, 19C3, when tho incident which is th-a subject of thi3

litigation occurred. During the preceding several r.onthn prior

to November 1, 1963, negro pupils had in varying forms expressed

their opposition to tho playing of 'Dixie at pop rallies and in j

compulsory student assarr.blios. Tho apparent masoning of the

Btudents, though not necessarily couched in those words, van

that the tono, 'Dixie,' war a relic of slavery den isnod to

- la.-

\

express tho Idea end longing that slavery and vhito supremacy

should return to, if not remain in, tho South. References in

tho song to tha pact and the longing for tho pent vore considered

by the black students to be nn affront to then. Plaintiffa and

other Uegro students and membern of their class had sought to

havo tho song, 'Dixie," eliminated from compulsory student

aasenblies and from pep rallies which seek the support of all

students by communicating their desire to the proper school

authorities. They have at all times made thoir protests in a

reasonable and peaceful rannor and havo at no time been physically

disruptive or violent.

Apparently in recognition of tho fact that tho song,

■Dixie,* was offensive to black ctudontn, defendants apparently

gave black students the dovisive option of not participating in

pop rallies and at the sarao tine apparently took tho position

I that whether “Dixio" would or would not bo played on about or

after November 1, 1960 at pc? rallies was not certain. Therefore,^

on November 1, 1968, when a pop rally was held, a number of black

I students choca not to participate in tho pep rally and a number

chose to arid did participate. Those who did not participate

stayed to themselves in a central site - tho school auditorium.

; Those who participated wont into the gymnasium. As coon as the

black students entered tho pep assembly, thoy were greeted by tho

playing of tiro tuno, "Dixie." At that point tho black students

simply did not toko seats, but turned end peacefully loft tho

gymnasium end went to join tho othar black students who had

elected not to participate in this pop rally. For their con-

i duct, tho students who quietly end peacefully walked out of the

gymnasium wero punished to tho extent that thoy wore required

1

I

'

to suffer grade reductions of 15%, denied participation in school

related functions during the period of their five-day expulsion

o-and,. as a condition for reinstatement, v/ere required to make

public apologies.

The severity of the punishment was extrene. For example

in the case of a person who had a low B average, a 15% grade re

duction would result in a drop to approximately a D average^ '.or a

person with a C average, a 15% grade reduction could mean that

the grade average would be reduced to the point of failure, thus

requiring an affected pupil to repeat a subject or perhaps

another school year. Such a course has financial significance.

Although school is not out, plaintiffs contend, on in

formation and belief, that they have been punished and humiliated

because of their race and their assertion of rights guaranteed to

them by the First, Fifth, Thirteenth, and Fourteenth Amendments

to the United States Constitution. The First Amendment rights

alleged deal with freedom of speech and association and is made

applicable to the defendants by the Fourteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution. The Fifth Amendment rights alleged

deal with procedural due process also made applicable to the de

fendants by the Fourteenth Amendment. The Thirteenth Amendment

rights alleged deal with the ability of black pupils to be free

from having to endure "badges of slavery" as they seek to enjoy

their Brown v . Board of Education •rights. The Fourteenth Amend-

j! ment rights are predicated upon the theory that only black students

for the most part, as a class can have significant objection to the

playing of this offensive southern symbol - "Dixie" - and, there-Ijji fore, any regulations promulgated to punish students for their

II ODposition to it could only, or primarily, apply to black students.

I indeed, only black pupils have been injured under this "Dixie"

I regulation. The due process rights asserted include the right not

only to have their administrators promulgate fair regulations, but

; their right to fair procedures for enforcing and applying those

regulations as welt,

- 3i-

-3-

\

&

Haintiffc* position, is that Srovn v. board^of^ Education#

347 U.S. 433 (1354) and lto projany require integration of

atudanta, faculties, and staff, and rcor-janlEetioft of tha school

*y#t«m In nuch a way ea to becon;o a unitary cno without undue

•ffrout or antagonists being aacouraguJ or jtejnvittcd by the

dofor.danta (or their ageate) In tholr official capacity on either

the bao;lo of r«c», religion, color or national origin. f!ie

fluyrer® Court baa redo thlo quite clear in the religion area,

which la analogous to the npaoch area, fotf-tlvot Court held that

public ocUool districts could not corpol prayer in the school®,

ffclngtca r.chool District v.. Scherjg, 374 W.B. 203 (1363). Vhirt-

liL_ta_i+4*r, t i . t la r.ov offensive to tho Constitution under t!;a

church and otata separation principle for a school cystsw to

paroit classes to bo started with a compulsory religious prayer.

On* apparent reason for reaching this result vac the fact that

most of the prayora tended to project religion into the schools

and ouch injection necessarily forced b o w * nonrollgieua students

to ha offended. A further reaeon for the Cuprevo Court's ruling

j *n 3ohosp;> was tMOt-thors-wsTryJ7̂ benefit n<scenirarily/lfco~*xj derived

| frow an opening prayer oven though it rcay be acceptable to all

| religious groups.

Zy analogy, therefore, it would aeos that there lo no

iij benefit to bo Afforded an integrated school system by the ployingIj off ar, offensive southern ayobol such as ’bixio" in a cowpulaory

j studant ocscubly or ot a school sponsored activity, the tune'*

|devioivs character can bo oooily s««n, for in this case it ha#

; sot students apart primarily because of races.cr̂ 3 Such derisiveness

is not beneficial -- indeed, it in detrimental -- to the educa-

I| tlonal process. School eyetans, under ilrown, supra, ve contend,

i: aro charged with the roapcnoibllity of converting their school

| systftKo in such e sannor vhoroin rocis'i, I* it block or white, 1b

neither taught nor condoned. Panuy v. County Hoard of Kdjacntien

j;of Caviar County. I”. 2d (0th Cir. 1363). If racists is to

.................................... ' *":develop, just «» if religious bigotry is to continue, reason

Ij

suggests that it not b« fostered by the school system.-Vo. -

- 4-

i

A basic issue involved is that of tho meaning of the

First Amendment ao applied to pupils who arc* required by the

State compulsory attendance law (Ark. Stats. Ann. SS00-1502-

80-1500, 1967 Ropl.) to attend school in tho context whoro those

\Btudcnts attend public schools. Once a student ia forced to

roceivo tho benefit of a public education, nuat he, therefore,

forfait hin constitutional right to apeak freely and association

with his peers? Tho courts in roccnt years havo answered thin

quaation nogativoly end hold in effect that n person*o right to

free speech and to reasonably exercise that speech is protected

by tho Constitution. Tho Court has uphold protests againct tho

Vietnam v.'ar made by studonto of tho public school system ns a

valid and reasonable cxercino of their Pirst Anendnont rights.

Tinker v. Den Koines Commu n i ty _Schoo I D lot r let, U.3. ___ ,

21 L.bd 2d 731 (1969) j Dickojy v . A1 obnrr.n_ J^tnte hoard of Education,

273 F.Supp. 613 (K.D, Ala. 1967).by analogy, ec a student in a

public school system cannot bo pur.ichod for reasonably and poaco-

fully protesting or statino hie opposition to tho Vietnam War*

nftithor can Jtudents bo punished for assorting their right to be

free from racial humiliation and school supported prejudice,

especially whero the method by which the pupilo aooort that right

ia psacoful and reasonable. This caoo is quito unlike that of

Blackwell v. Issaquena Board off IkJucntion, 363 F.2d 749 (5th Cir. j

1956), where students engaged In on unquestionable degree off loud

and boistorouo conduct following tho wearing of froodom buttons.

Tho courtn strongly implied in that caoo that if tho students had ̂

not been boistoroua or loud in disrupting, suspensions would not j

havo boon uphold. Likewise, in Wright v. Toxnn Southern

University, 392 F.2d 72D (5th Cir. 1960), tha court hold that

•tudonts exceeded tha bounds of permissible conduct by the

physical and verbal abuse which was heaped upon a school official.

- 5 a. —-5-

I

•nriroR»cftt wore upheld. rlalotlffs thus contend that tha teat

to bo applied In dateroinlny whether defendant* acted yroporly

la follov*» Vero tho students encaycd In an assertion of

•peach and car.cciaticn rights, and if so« wc.ro thc>y peacefully

and reasonably aacurtin; or «tsaroiuing thoso rl<j!.t*7 If tney

veto, any pvinlahawit therefor by school official* violates the

bnitad statu* Constitution. rurnclCi.- v. fcyaro. 313 r.2d 744

<;th Clr. ISCt).

Plaintiffs «So not contend that echool officials atro

powerless to fonrulatst reatcr.aVlft r«*;ulttionr to severe the

behavior or conduct of pupils vblle in the cur-tody of defciadsat*.

iChat they do contend It that the royulntior.o in thin ctio, if

tliero W any, era patently cnreatchftblc *::<! thus offensive to the

Constitution. J'-oruovsr, th«ro can bo no crgvrsent that th.u very

vor‘it of the turns, ’Pixie.' su^jeat lor.yin? for and adheranc* toI

the precept* of the pro -Civil car ora, prccopta which wore finally

struck dovn, hopefully fee all tine, by the Rupr<nv« Court Is

i-rcwii v. hoard of. f ducat ten, eupra. ~her*forft, v* contend that

! the playin'* of 'Pixie,’ by a school a per. cored croup in r. school

| content constitutes a l adpo of slavery forbidden by thw Consti-

; tut ion. don®3 y. PyA>ra, 3S2 b.S. 4C9 (19«0), (corcurrlinj opinion)>

$♦*1. v. "aryl*n$. 373 235, 242 (1963).

finally, plaintiffs vora. denied ri<jhte guaranteed to

thoas by the duo process and c^vsi protection clauses of the

Vourtcanth hNor.dsfcont to th* L'nits.i ftatos Constitution. Plaintiffs

wore ptmish-ad for violati ny va'jUfl, indvfiriite and ir.vufficioatly

publicised regulations (if lndca-i that* v<sro any revelations at

ell) , rjyulr.tions which w*ro liXuly and predictably applicable to

blech student* primarily. A regulation may appear reasonable

on its face but if it can only be racial in result, it foot b«

| struck do /si. fee, for axacpla. the “voter fraesi/v;" casts. If

i a county or state has a history of ba.jro voting denial, and or.o

of relatively full white voter ro jistrntion, coupled with rany

jj unfraschinttii Macke of lev education, to impose a litoracy test

-ia.-

- e -

ij and impartially administer it would b« to parpatuato tha status

i quo but in * different fora. Co a t o nCo un ty,_ t'or th Ce rollna y.

j United rtatgg, 37 U.r.L.tfeoX (JiinO 2, 19C5}» ^hdtm_v._KontJUc)i^#

304 U.S. 13$ (1?G$).

Plaintiffs were further deprived of a fair hearing andI

j opportunity to bo represented by counsel by such euspenoion-

i| Olrony. Alabama statoboard of Education, 234 P.2d 150 (5th cir.j

J 1?61). They vero deprived of notice of the charges against thoa,

: of the opportunity to confront their accusoro, and the wholo

! plethora of duo process righto offerded accused poroone about to

| be faced with penalty for rule or la* violations. In a (sense,

|

therefore, the seriousness of the penalties! iwpoeed is comparable

to r.any nlcderejanor offon3oa. but, at leant in Court, a person

has certain rightn. t’or those and other roaconu, the convictions j

and (subsequent punishment of plaintiffs cannot ho allowed to stand.

Tho relief that would bo appropriate now should, of

i

| course, be foraulntcd by tiso Court ; but vtt believe that equity

j rcquiren at tha locot that!

(D defendants be unjoined from approving the playing

■ of tha tuno, "Dixie," at school tainted affairs or functions.

(2) any rule or regulation promulgated by defendants

l! which punishes or premicos to punish or affect one racial group

! by ito operation end doeo not apply to tho dominant racial group,

|j or to tho entire student body for that matter, bo otruch down.

(3) the apocific rule relied upon by defondanto heroin i

j| bo atruoh down oo violative of tho First, Thirteenth and Fourteenthl!li Amendments to tha Constitution of tho United States;I]

(4) plaintiffn end any members of their class affected

i by tho acto complained of in tho complaint bo restored to tho

|j position or status they would hovo had had tho cucponoionu not

been enforced; end if any atudont suspended purauent to this

li policy has been forced to undergo oxponoe of ouneor school cduca-]|

tion or boon deprived of tho opportunity to graduate with hisl|jj clasc or bo prosftotad, that auoh expense bo paid to ouch person

by tho defendants and that defendants bo required where necessary

to grant diplomas to any plaintiff or ner.bor of plaintiff's claao

' and provide tutorial help to any person effected by the acts

-7-

- 7 A -

complained about) and

(5) that dcfond&nte be enjoined otherwise aa io

■pacifically requonted in tha complaint.

Plaintiffs do not waive any of their righto for relief

by this Memorandum of Law and respectfully otntoa to the Court

that although cone of tho points nnoortad nay indeed bo novel

puroly because of tho naturo of tho suspensions and tho paucity

of caso lav/ of tho general subject, plaintiffs are nonetheless

entitled to comprehensive equitable relief, for which they

pray.

Respectfully oufcnittad,

KALKF.R, ROTENBEMY V KAPLAN

1820 West 13th Street

Little Rock, Arkansas 7220

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES N. HABRIT, IIIMICHAEL KELTSNER

HORilAN J. CKACHKIN

Suite 2030

10 Columbus CircleKcw York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

i

By _____ ____

~Jofin H. Walker

CERTIFICATE OP SERVICE

I do hereby certify that I havo served a copy of tho

above and foregoing Memorandum of Law upon tho attorney for

defendants, Ecrl S. Smith, Lnq., at Barrott, wheatloy, Smith

i Deacon, 004 Citineno Bank building, Jonesboro, Arkansas, by

nailing came, this 13th day off Juno, 1909.

-*<L-

- 8-

;

\

„„ 0 o£ the "blach end Cold" handbook tetniehcd

. U student* .t Jonesboro nigh School oppe.r. the folloolng

n u n s Strictly against the rules to create a

disturbance in assembly.

On page 44 in the Jonesboro Senior High School

Teacher Handbook, under "Policy of the Jonesboro School

Board," adopted August 11. 1959, appears the following:,

"The Principal shall be empowered to use all

means that he deems necessary to maintain

discipline at all times, and shall have the

support of the Board, as long as such means

arc reasonable and legal.

t

I

■ o. p.k« « . « s” ‘" "lEh scb°o1

, ..suspension” appears the

Teacher handbook, under

following:

e* studeat . « »• « * P " 4" 1 tr°“ ‘Ch°01 ?

school pt.otlP*1 .» Joatlflnhlo pround, lot .

period not to exceed one »eek, provided verb.l

notii loot l°n 1“ d)v,n P*tcn" l'nnie‘lla 1e IP *

case it is not possible to notify parents

verbally, they will be promptly notified by

mail. U the points deducted from a student's

daily average scores due to suspension should

result in lowering his score as much as

letter grades (such as dropping from B to D)

or cause him to have failing marks in his daily

average scores, at that time he may request per

mission to do sufficient extra work to remove

the penalty caused by the suspension. Such

request will always be granted provided the

make-up work is completed in one week after

return. It is not the intention of the school

to cause the student to fail due to suspension."

:i

\