NAACP v. Thompson Brief for Appellants in Support of Motion for Injunction Pending Appeal

Public Court Documents

June 24, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP v. Thompson Brief for Appellants in Support of Motion for Injunction Pending Appeal, 1963. 0a34111c-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0e99cbe3-50c7-4d52-b92d-88d93b410bb4/naacp-v-thompson-brief-for-appellants-in-support-of-motion-for-injunction-pending-appeal. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

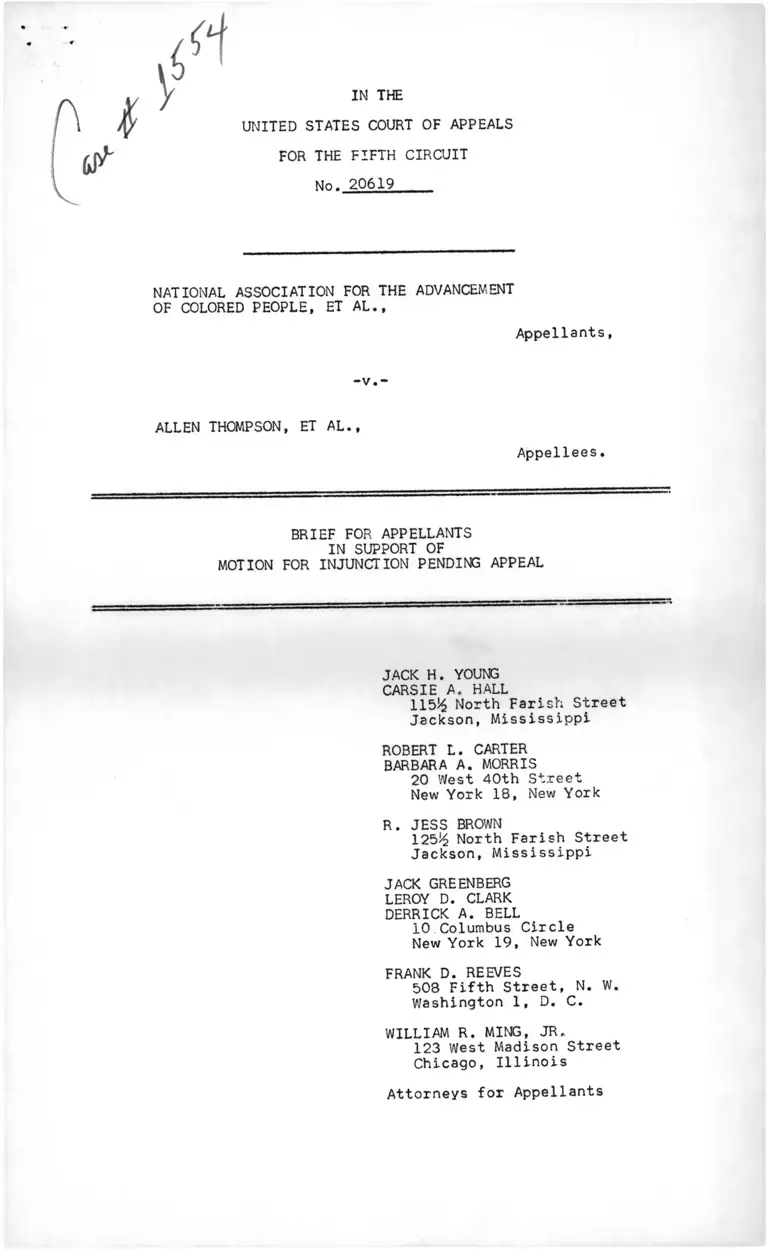

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 20619

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT

OF COLORED PEOPLE, ET AL.,

Appellants,

- v . -

ALLEN THOMPSON, ET AL.,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

IN SUPPORT OF

MOTION FOR INJUNCTION PENDING APPEAL

JACK H. YOUNG

CARSIE A. HALL

115^ North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi

ROBERT L. CARTER

BARBARA A. MORRIS

20 West 40th Street

New York 18, New York

R. JESS BROWN

125^ North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi

JACK GREENBERG

LEROY D. CLARK

DERRICK A. BELL

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

FRANK D. REEVES

508 Fifth Street, N. W.

Washington 1, D. C.

WILLIAM R. MING, JR.

123 West Madison Street

Chicago, Illinois

Attorneys for Appellants

Index

Page

Statement of the Case---------------------------------- 1

Argument

I, This Court Has Jurisdiction to Both Hear

This Motion and Grant the Injunctive

Relief Sought by Appellants------------------ - 5

A. The Order of the Court Below is Appealable

Under 28 U.S.C., Section I292(l)--------- 5

B. The Relief Urgently Sought By Appellants

Is Well Within the Power of This Court--- 9

C. 28 U.S.C., Section 2283 Is No Bar to

Appellants’ Requested Relief------------- 11

II. Appellees, By Enforcing Racial Segregation

Required By State Law, Have Abridged

Appellants’ Constitutionally Protected Freedoms

of Expression and Assembly and Have Thereby,

Created an Emergent Situation Necessitating

Interim Injunctive Relief by This Court------ 15

A. Consistent with State Policy, Appellees

Have Violated Appellants' Constitutional

Rights By the Enforcement of Racial

Segregation------------------------------ 16

B. Appellants’ Protest Activities Are Pro

tected By Their Constitutional Right of

Freedom of Expression and Assembly-------- 19

C. The Urgent Relief Sought By Appellants

Is Justified By the Circumstances of

this Case-------------------------------- 22

Conclusion-------------------------------------------- 24

Table of Cases

American Optometric Ass'n. v. Ritholz,

101 F.2d 883, 887 (7th Cir. 1939)..... ................. 13

Bailey v. Patterson, 199 F. Supp. 595 (S.D. Miss. 1961)

368 U.S. 346, 369 U.S. 31 (1962)................... 5,11,14

Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U.S. 516.................. 15,19

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497......................... . 16

Browder v. Gayle, 352 U.S. 903....... ................... 15

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)...... 10,15,17

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917).......... 7,10

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296............ 19,21

Clark v. Thompson, 313 F.2d 637 (5th Cir., 1963)....... 5

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958)............. 10,16,19

Cooper v. Hutchinson, 184 F.2d 119 (3rd Cir., 1950)......... 12

CORE v. C. H. Douglas,___F.2d___, (5th Cir., May 15, 1963). 10

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, ___F.2d___(5th Cir., May 24, 1963)............. 10

DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U.S. 353....... ............ . 21

Denton v. City of Carrollton, Ga., 235 F.2d 481

(5th Cir. 1956)................... ................... 12,13

Douglas v. City of Jeannette, 319 U.S. 157

235 F.2d at ...................................... . 13,14

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U.S. 229................... 6,20

Evers v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

District No.____ (S.D. Miss. 1963)..................... 6

Feiner v. New York, 340 U.S. 315................. ......... 20

Fowler v. Rhode Island, 345 U.S. 67.................. . 20

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157 (1961).................. 5

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U.S. 903......... ..................15,16

Gibson v. Florida Legislative Investigative

Committee, 342 U.S. 539.................... ............ 15

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339............ .......... 15

Gremillion v. NAACP, 366 U.S. 293......................... 15

Grosjean v. American Press Co., 279 U.S. 233.............. 19

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U.S. 296..... ......................19,21

Hughes v. Superior Court, 339 U.S. 460..................... 20

ii

Page

Table Of Cases

(Continued) Page

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24 (1948)...... .............. 10

Jamison v. Alliance Ins. Co. of Philadelphia,

87 F.2d 253, 256 (7th Cir. 1937)........ ................ 13

Kunz v. New York 340 U.S. 299........................ 20,21

Lombard v. State of Louisiana, 31 U.S.L. Week 4476 (1963)... 20

Martin v. Struthers, 319 U.S. 141................. . 19

Meredith v. Fair, 298 F.2d 696, 701 (5th Cir., 1962)....... 5

Milk Wagon Drivers v. Meadow Moor Dairies,

321 U.S. 287........................... ................ 20

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167............. 16

Morrison v. Davis, 252 F.2d 102, 103 (5th Cir., 1958),

cert, denied, 356 U.S. 968 (1958).................. . 13

NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 458......... .................. 15,19

NAACP v. St. Louis & San Francisco Ry„ Co.,

297 I.C.C. 355........................ ................ 15

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697......... ............... 21

Nelson v. Grooms, 307 F.2d 76 (5th Cir., 1962)..... . 10

New Negro Alliance v. Sanitary Grocery Co.,

303 U.S. 552........ ................................... • 20

People v. Barkel, 36 N.Y.S. 2d 1011 (1942)........... 20

People v. Kiernan, 26 N.Y.S. 2d 291 (1940)................ 20

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 31 U.S.L. Week 4475(1963).. 6,20

Plumbers Union v, Graham, 345 U.S. 192............ . 20

Schenck v. U.S., 249 U.S. 47................... . 19

Schneider v. State, 308 U.S. 147........................ . 21

Screws v. United States, 325 U.S. 91.......... .......... 16

Sellers v. Johnson, 163 F.2d 877 (8th Cir., 1947)......... 10,19

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1......................... 16

Shepherd v. Florida, 341 U.S. 40........................... 15

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649.................... 15

Smith v. Apple, 264 U.S. 274..,.......... 13

Stell v. Savannab-Chatham County Board of Education,

___F.2d___ (5th Cir., May 24, 1963).... ................. 10

Stromberg v. California, 283 U.S. 359................ «...... 19

iii

Table Of Cases

(Continued)

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629..... ..................... 15

Teamsters Union v. Vogt, 354 U.S. 284........ ......... 20

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 86. „... .................. 19,21

Toucey v. New York Life Insurance Co.,

314 U.S. 118................................ ........ 12

United States v. City of Jackson, ___F.2d___,

(5th Cir., May 13, 1963)........ .................... 5

United.States v. Lynd, 301 F.2d 818 (5th Cir., 1962)..... 7,9

United States v. Wood, 295 F.2d 772 (5th Cir., 1961).. 7,11,13

Watchtower and Bible Tract Society v. Dougherty,

337 Pa. 286, 11 A.2d 147............................. 20

Watson v. City of Memphis, ___U.S.____(May 27, 1963).... 10

Wells Fargo 8. Co. v. Taylor, 254 U.S. 175..... .......... 13

Woods v. Wright, ____F.2d____(May 22, 1963)............. 10

iv

Page

Statutes. Regulations. Rules and Other Authorities

U.S.C. Sections

28 U.S.C. ,§1292(1)................................... 5,8

22 U.S.C.,§1651...................... 9,12

28 U.S.C.,§1335.............. 12

28 U.S.C.,§2283..... 11,12,13

42 U.S.C.,§1983................... 11

Mississippi Constitution

Mississippi Constitution, §225...... ...... ........... 17

* ' ■ ' '

Mississippi Code, Sections

Code of Mississippi, §2056.7........................... 17

Code of Mississippi, §2339................ 17

Code of Mississippi, §2351.5........................... 17

Code of Mississippi, §3499................... 17

Code of Mississippi, §4065.3............. 5,14,16,17

Code of Mississippi, §4259................ 17

Code of Mississippi, §6882..... 17

Code of Mississippi, §6883.................. 17

Code of Mississippi, §7913...... 17

Code of Mississippi, §7965,...... 17

Code of Mississippi, §7971...... 17

Code of Mississippi, §7786............. 17

Code of Mississippi, §7787.5....,........ 17

V

Statutes. Regulations. Rules and Other Authorities

(Continued)

Page

Rules

F.R.C.P. 62 (9)............................... .......... 9

Other Authorities

Moore, Commentary On Judicial Code..................... 12

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 20610

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT

OF COLORED PEOPLE, ET AL.,

Appellants,

v.

ALLEN THOMPSON, ET AL.,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

IN SUPPORT OF

MOTION FOR INJUNCTION PENDING APPEAL

Statement Of The Case

Commencing on approximately May 28, 1963, appellants, members

of their class, and supporters of equal rights for all citizens

began a series of peaceful protest demonstrations protesting en

forced segregation in the City of Jackson. All of their subsequent

activities have been conducted in a peaceful manner. Any violations

or threats have come from members of the public who disagree with

their views. The officials named as defendants in Count One of the

complaint, have used all the processes of law available to them,

including arrests, convictions, requirement of cash bail bonds,

and court actions to frustrate or prevent the registering of any

expression by appellants and members of their class inconsistent

with the segregation laws and policies in the State of Mississippi.

Appellants have been constantly and violently threatened, intimidated,

and arrested by appellees in their attempts to express their

opposition to the action of Jackson police officials to maintain

and enforce rigid racial segregation as provided by the laws of the

State of Mississippi.

On June 7, 1963, plaintiffs, Negro and white citizens of

the United States, residents and non-residents of Mississippi,

and a non-profit member corporation filed a verified complaint

together with motion for temporary restraining order or preliminary

injunction supported by affidavits in the United States District

Court for the Southern District of Mississippi.

Count One of that verified complaint is involved in this

motion. The complaint reflects that city, county, and state

officials of Jackson, Hinds County, and Mississippi have embarked

on a program, under color of law, to enforce and maintain racial

segregation in the State of Mississippi by means of unlawful arrests,,

prosecutions, and convictions of appellants and the class they

represent for peacefully protesting racial segregation and dis

crimination in Jackson, Mississippi, in places of public accommodatiu

and in the use of public facilities.

The motion, originally returnable on June 7, was adjourned

to June 8, on which date the appellees appeared and filed a motion

to dismiss the complaint. Argument on the motion was heard on

June 8, 1963, and on June 10th testimony was taken in support of

appellants' motion for temporary restraining order and preliminary

injunction. Immediately prior to the hearing on June 10, the

appellants, named as defendants in Count One, served copies of

affidavits upon counsel for appellees, which affidavits have been

made a part of the record of this proceeding.

In the course of the hearing, testimony was taken from Allen

Thompson, Mayor of the City of Jackson, W. B. Rayfield, Chief of

Police of Jackson, and J. R. Gilfoy, Sheriff of Hinds County.

Chief of Police Rayfield testified that prior to May 25, 1963,

arrangements had been made to hold large numbers of persons in

custody. [Tr. 13],

Mayor Thompson confirmed this fact • that the plans were

made in anticipation of restricting rights of plaintiffs protesting

racial segregation in the City of Jackson, and explained how exhibit

- 2 -

buildings on the county fair grounds had been accommodated for use

as prison facilities as early as May 12, 1963. [Tr. 30 and 37].

Mayor Thompson testified that the "instant arrest" policy utilized

by appellees to suppress and restrict appellants' rights to protest

was in accordance with his instructions and his policy of "main

taining law and order." [Tr. 59].

Mayor Thompson further testified that demands were made by

members of the Negro community to discuss the segregation policies

with him to the end of effecting their termination. [Tr. 72]. He

admitted that segregation existed in Jackson in restaurants and

other places of public accommodation, was vague on details of

arrestsof adults and juveniles and of the disposition of the arrest

but stated that all actions of the police were in accordance with

his policies or instructions. [Tr. 93; 95; 61-62; 65; 96],

Sheriff Gilfoy testified that part of his county personnel

had been assigned to work with the Jackson police in their efforts

to attenuate the peaceful protests of appellants and that county

officers had assisted the Jackson police on three occasions. [Tr. 9

100].

Following the conclusion of testimony from the above three

witnesses, Judge Cox reminded counsel of his intention to leave the

following day for a long planned vacation, whereupon counsel for

all parties agreed to submit the motion to the Court on the pleadin

affidavits filed, testimony, and argument of counsel and upon con

formed copies of certain proceedings in the Chancery Court of Hines

County. [Tr. 108-109].

On June 6, 1963, the City of Jackson obtained a writ of

injunction restraining, without hearing or notice, some of appellan

and the class they represent from engaging in peaceful protests

against racial discrimination and segregation, including parading,

picketing, and seeking of nonsegregated service in public estab

lishments, all of which were termed unlawful. No prior hearing was

accorded appellants; a hearing on that temporary injunction will

not be accorded before September 9, 1963. Appellants' motion to

3

dissolve or stay execution of the temporary injunction was denied

by the Chancery Court of the First Judicial District of Hinds

County on June 7, 1963, and by the Supreme Court of Mississippi

on June 10, 1963. No hearing was accorded prior to determination

of either motion. On June 13, 1963, appellantsfiled a petition and

a motion to dissolve or to stay the execution of the temporary

injunction of the Hinds County Court in the Supreme Court of the

United States. The motion was denied on June 14, 1963.

On June 11, 1963, Judge Harold Cox entered an order refusing

the temporary injunction or a temporary restraining order and di

recting appellants, at peril of their right to federal injunctive

relief, to obey the ex parte temporary injunction of the Hinds

County Chancery Court.

The facts upon which appellants base their request for in

terim relief from this Court are set forth in affidavits of the

following persons filed heretofore with the Clerk of the Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit: appellants Willie B. Ludden; Rev.

Ralph Edwin King; Doris Allison; Doris Erskine; Medgar Evers and

Langston Mitchell, Jr.; Mary Lee Veal, John Clifton Young, Tommie

Jean Levy, John Salter, Frankie Adams, Alphonso Lewis and those

affidavits which will be presented to the Court prior to oral argu

ment of this motion.

On June 12, 1963, appellants filed a Notice of Appeal re

questing entry of a temporary injunction pending appeal of this

cnuse together with a Statement of Points and Designation of the

Contents of the Record on Appeal. By order of this Court entered co.

June 14, 1963, argument on the aforesaid motion was set down for

June 26, 1963.

4

A R G U M E N T

I

THIS COURT HAS JURISDICTION TO BOTH HEAR THIS MOTION

AND GRANT THE INJUNCTIVE RELIEF SOUGHT BY APPELLANTS

A. The Order Of The Court Below Is Appealable

Under 28 U.S.C., Section 1292(1).

The failure of the court below to rule on appellants' motion

for a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction, and

its ruling that the state court injunction is "not void, and

should be respected," constitutes an appealable order as defined

in 28 U.S.C., Section 1292(1), which section gives this court

jurisdiction of appeals from: "Interlocutory orders of the district

courts of the United States...granting, continuing, modifying,

refusing or dissolving injunctions, or refusing to dissolve or

modify injunctions,..."

Appellants have suffered serious violations of fundamental

constitutional rights by reason of the appellees' determination

to maintain segregation, and have detailed the history of incidents

leading to this action in their complaint. Affidavits filed in

response by appellees have not contravened these allegations, and

from the record, it is clear that there is no basic dispute as to

the facts.

The urgency and necessity for immediate action is obvious.

For a long period of time, appellants have been denied rights and

privileges freely exercised by white citizens in the State of

Mississippi because of the firmly fixed policy of racial segregation

existing in that State. 17 Miss. Code Ann. § 4065.3; Meredith.v.

Fair. 298 F.2d 696, 701 (5th Cir., 1962). Appellees have followed

this policy and have defended it in the courts. See, Bailey v...

Patterson. 199 F. Supp. 595 (S.D. Miss. 1961), 368 U.S. 346, 369

U.S. 31 (1962), segregated public travel facilities; Clark v.

Thompson. 313 F.2d 637 (5th Cir. 1963), segregated public recre

ational and library facilities; United States v. City of Jackson.

____F.2d____, (5th Cir., May 13, 1963), segregation signs in public

- 5 -

travel terminals; Evers v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District

No._____ (S.D. Miss. 1963), segregated public schools.

Now, appellants and members of their class seek by peaceful

protests and demonstrations to convey publicly their strong desire

that racial segregation be ended in Jackson. In response, appellees

have adopted policies and practices aimed at suppressing these

peaceful expressions, which policies and practices are both in

1/violation of appellants®constitutional rights, and are contributing

to an increase in bitterness, racial tension and the probability

of violence. Concluding that appellees intend to continue their

policy of censoring all peaceful protests against racial dis

crimination with arrests and harassment, and fearful that the

brutal suppression of clearly constitutional rights would lead

to further violence by whites and possible retaliation by Negroes,

appellants sought to forestall such conflict, and turned to the

federal court for relief against the policies of appellees and

for vindication of their constitutional rights.

In response, Judge Cox found in his order of June 11, 1963,

from which appellants appeal, that there is "no crisis at hand;

and no necessity or urgency for any immediate actionc" He further

found that the case "is extremely complicated and involves many

intricate legal facets which would entail further intensive

examination and study." For these reasons, Judge Cox "ordered

that this matter will be taken under advisement by the Court for

study and later decision at the proper time."

Since, as indicated in paragraph 7 of the appellants’ Motion

for Preliminary Injunction Pending Appeal, Judge Cox will be absent

1/ earner v. Louisiana. 368 U.S. 157 (1961); Edwards v. .South

Carolina. ___U.S.___, 9 L.Ed. 2d 697 (1963); PetersoQ,_y;.

City of Greenville. U.S. (May 20, 1963).

- 6 -

on vacation for a period of three weeks from June 11, 1963, it

is unlikely that further orders in this case will be forthcoming

from the court below for some time.

Thus, the situation here is similar to that in U.S. v. Lynd,

301 F.2d 818 (5th Cir., 1962) where Judge Cox declined either to

grant or refuse a temporary injunction requested by the government

in a suit to enjoin discriminatory voting practices, and granted

a recess of 30 days to permit the defendants to file an answer

and to prepare for proving their defensive case. This action was

taken in litigation brought to remedy obvious deprivations of

voting rights.

Under these circumstances, as this Court indicated in

U.S. v. Lvnd. supra, appellants were clearly entitled to have a

ruling from the trial judge, and since he did not grant the order,

his action in declining to do so was in all respects a "refusal",

so as to satisfy the requirements of §1292. Cf. U.S. v. Wood.

295 F.2d 772 (5th Cir., 1961).

True, in the Lvnd case, the government's motion for injunctive

relief had been pending for eight months and efforts to obtain

voting records had been frustrated for eleven months before that,

but the decision to grant relief pending appeal appears to pivot

not on the amount of time the government's motion had been pending,

but on Judge Cox's failure to act affirmatively on the motion for

injunctive relief. Thus, the Court concluded:

Where, however, as is here the case, the

plaintiff made a clear showing that rights

which it sought to vindicate were being

violated, and that no response or counter

proof would be available for some con

siderable period after these rights should

have been, but had not been, taken under

consideration by the trial court, the

plaintiff has satisfied every requirement

for the granting of temporary relief pending

a final adjudication of the appeal.

(301 F.2d at 823.)

Here, no less than in Lvnd. relief was requested of Judge

Cox to protect constitutional rights of Negroes from violation

by state officials intent on maintaining racial segregation. But

in addition, there is here an urgency borne out of a fear of

violence that has subsequently been realized with the murder of

7

one of the plaintiffs in this cause. Judge Cox failed to give

that relief in circumstances where it is urgently needed, con

cluded that no crisis exists, stated that further intensive

examination and study is needed, and departed for a three week

vacation.

A further indication that the court below*s order of June 11th

effectively denies the relief requested by appellants in their

motion for a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction

is found in the final paragraph. Here, Judge Cox refers to an

ex parte temporary injunction obtained by appellants on June 6,

1963 from the Chancery Court of Hinds County, which injunction,

without notice or opportunity to be heard, enjoined some of the

appellants and other persons from a whole series of acts and

practices designated by the injunction as illegal and unlawful.

Appellants alleged that the ex parte injunction was one more

illustration of appellees’ willingness to utilize all the powers

of government to maintain racial segregation, but sought no

specific relief with reference to this injunction. Judge Cox

ruled however, that:

The injunction issued by the state court against

the plaintiffs is not void, and should be respected

by the parties and their attorneys until vacated

or reversed, whether it be to the liking of such

parties or not; and further inquiry will be made

later by this Court on that question for a

determination of the status of the parties in

a federal court of equity before a decree is

entered here.

Thus, the court below, on its own motion, engrossed the

state court injunction into its order, "granting" an injunction

in the terms of §1292(1), that the state court injunction was

"not void" and was in fact sufficiently valid to require that it

"be respected by the parties and their attorneys until vacated

or reversed." To obtain compliance of its order, the court in

dicated that unless the state court injunction were obeyed, "whether

it be to the liking of such parties or not," the appellants' stand

ing to obtain equitable relief in a federal court would be

jeopardized.

- 8 -

Appellants submit that this action by the court below was,

in the circumstances of this case, a clear abuse of his discretion

of so important a nature as to fully warrant protection of appellant!

rights pending a decision on this issue by this Court, U. S. v.

Lvnd. supra,

B. The Relief Urgently Sought By Appellants Is

Well Within The Power Of This Court,

The injunctive relief sought by appellants pending appeal

is necessary to protect their rights during the appeal of this

case, and is necessary to preserve the effectiveness of any judg

ment subsequently to be entered, for unless appellees are immediately

enjoined from suppressing appellants’ efforts to end racial segre

gation by peaceful debate and demonstration such peaceful programs

will be stifled beyond resuscitation.

This court has the power to grant the injunction requested.

This power is conferred by the following provisions of Title 28,

United States Code, Section 1651:

(a) The Supreme Court and all courts established

by Act of Congress may issue all writs necessary or

appropriate in aid of their respective jurisdictions

and agreeable to the usages and principles of law.

(b) An alternative writ or rule nisi may be

issued by a justice or judge ofacourt which has

jurisdiction.

And this power remains expressly unfettered by Rule 62(g),

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, which provides as follows:

(g) POWER OF APPELLATE COURT NOT LIMITED. The

provisions in this rule do not limit any power of an

appellate court or of a judge or justice thereof to

stay proceedings during the pendency of an appeal or

to suspend, modify, restore, ot grant an injunction

during the pendency of an appeal or to make any order

appropriate to preserve the status quo or the

effectiveness of the judgment subsequently to be

entered.

When this case is heard on appeal, appellants will contend

that the policy of instantly arresting all persons seeking to

peacefully protest against racial discrimination is violative of

fundamental constitutional rights. This Court has recently acted

- 9 -

>to protect similar rights, CORE v. C. H. Douglas. ____F.2d

(5th Cir., May 15, 1963). However, unless an injunction pending

appeal is granted, appellants will be denied such rights for a

long, and during a critical period in their struggle for full

citizenship in Mississippi. If, as they firmly believe, appellants1

contentions are correct, they will have suffered an irreparable

injury to their rights.

On the other hand, appellees can hardly contend that they

will suffer injury if they are required to protect and not deprive

appellants of their right to protest racial discrimination. The

public peace may not be maintained by depriving Negroes of their

constitutional rights. Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917);

Cooper v. Aaron. 358 U.S. 1 (1958); CORE v, Douglas, supra;

Sellers v. Johnson, 163 F.2d 877 (8th Cir., 1947).

Clearly, the public interest is involved here due to the

national interest in the elimination of state enforced racial

segregation, Brown v. Board of Education. 347 U.S. 483 (1954), and

the elimination of racial discrimination generally, Hurd v. Hodge,

334 U.S. 24 (1948). Lengthy delay in desegregation progress is

viewed with increasing disfavor by the Supreme Court, Watson v.

City of Memphis. ____U.S.____ (May 27, 1963).

Indeed, this Court has recently admonished lower courts to

more speedily cut through delaying tactics utilized in civil rights

litigation, see Nelson v. Grooms. 307 F.2d 76 (5th Cir., 1962),

concurring opinion, and Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of

Mobile County. ____F.2d____ (5th Cir., May 24, 1963). In St ell v._

Savannah-Chatham Countv Board of Education. __ F.2d___ (5th Cir.,

May 24, 1963), this Court granted an injunction pending appeal from

the denial of a preliminary injunction to initiate school desegre

gation, citing as authority, 28 U.S.C.A., §165l(a). Citing the

same section, the Chief Judge of this Court granted an injunction

pending appeal in Woods v» Wright. ___F.2d___(May 22, 1963), re

quiring the Birmingham Board of Education to reinstate 1,000 Negro

students expelled from school for protesting racial discrimination.

The rationale of these decisions is entirely appropriate here,

and the urgently sought relief by appellants pending appeal should

be granted. 10 -

C. 28 U.S.C., Section 2283 Is No Bar To Appellants’

Requested Relief.

Appellees’ utilize not only legislative and executive powers,

but judicial authority via state court prosecutions to deprive

appellants of their constitutional right to protest against the

state enforced policy of racial segregation. Therefore, appellants'

motion for a preliminary injunction pending appeal seeks to enjoin

prosecution of appellants who have been arrested but not tried or

convicted for participating in peaceful demonstrations against

racial segregation (paragraph (h)).

This relief, in the circumstances of this case, is necessary

to prevent the irreparable harm which will be suffered by appellant

as a result of exposure to prosecution in the State of Mississippi

for defiance of the policy of enforced racial segregation, see

United States v. Wood, 295 F.2d 772 (1961); Bailey v. Patterson,

199 F. Supp. 595, 612, 616 (S.D. Miss. 1961)(dissenting opinion)?

Such relief is not barred by reason of 28 U.S.C., Section 2283

which provides;

A court of the United States may not grant an

injunction to stay proceedings in a State court

except as expressly authorized by Act of Congress,

or where necessary in aid of its jurisdiction, or

to protect or effectuate its judgments.

Appellants submit that this case, which seeks relief under

the civil rights statute, 42 U.S.C., Section 1983, constitutes an

exception "expressly authorized by Act of Congress,..." Section

1983 provides:

Every person who, under color of any statute,

ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any

State or Territory, subjects, or^causes to be

subjected, any citizen of the United States or

other person within the jurisdiction thereof to

the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or

2/ The Supreme Court refused to enjoin prosecution of the "Freedom

Riders" under Mississippi’s breach-of-peace statutes because

the appellants did not allege that they had been prosecuted or

threatened with prosecution, and therefore lacked standing to

seek such relief. Bailey v. Patterson, 368 U.S. 34 ; 369 U.S.

31 (1962). No such standing problems exist here. Each of the

individual appellants have been arrested, prosecuted or face

prosecution.

11

immunities secured by the Constitution and laws, shall

be liable to the party injured in an action at law,

suit in equity, or other proper proceeding for redress.

This is the view of the Third Circuit which held in Cooper v.

Hutchinson, 184 F.2d 119 (3rd Cir. 1950), that an injunction could

issue against a state court murder prosecution unless the defendant

3/

were permitted counsel of his choice.

This Court appears in accord with the Third Circuit, for in

Denton v. City of Carrollton. Ga., 235 F.2d 481 (5th Cir. 1956), the

Court reversed a district court’s refusal to enjoin a municipality

from bringing criminal proceedings against a union under an ordi

nance requiring labor organizers to pay a license tax of $1,000

plus $100 a day thereafter. The district court had based its

3/ The first exception to 28 U.S.C., §2283 permitting injunctions

where "expressly authorized by act of Congress" is expressly

applicable only to one statute, the Federal Interpleader Act, 28

U.S.C., §1335, which Act specifically authorizes injunctions

against state court proceedings. However, the wording of other

federal statutes has been said by the courts to imply an excep

tion to §2283. These cases are gathered in Toucey v. New York

Life Insurance Co., 314 U.S. 118. The Civil Rights statute is

an implied exception. Cooper v. Hutchinson, supra.

The second exception which permits federal court injunctions

"where necessary in aid of its jurisdiction" was originally

intended to enact into law the theory of the "res" cases (ena

bling federal courts to protect property which is the subject

of a federal suit from seizure by the state). But the Section,

according to Moore, Commentary on Judicial Code, p. 412, indicate

that the exception provides '• sufficient flexibTlity that a

federal court, as a court of equity, may mould its processes to

deal adequately with the situation at hand."

The third exception permitting a federal court to enjoin state

proceedings "to protect or effectuate its judgmentsis intended

to permit the federal courts to prevent the relitigation in state

courts of rights already adjudicated in an earlier federal court

decision. Moore, supra, p. 410.

Appellants suggest that exceptions two and three are also appli

cable to the case at bar in that the arts of appellees_complained

of here deprive appellants of constitutional rights which this

Court has clearly*hold they possess, because the exceptions are

intended to insure that federal courts will be able to maintain

control over matters in its jurisdiction. Section 2283 takes

on its true prospective when, as suggested by Moore, supra, p.

407, it is read in conjunction with the all writs statute, 22

U.S.C., §1651.

12 -

refusal to grant relief on 28 U.S.C., Section 2283, and the doctrine

of comity.

As in the instant case, a high degree of harm was threatened

to appellant, and it is the measure of this prospective harm which

appears as the controlling factor for entitlement to this form of

relief. Thus, the Court in the Denton case, supra, found that the

rule of Douglas v. City of Jeannette, 319 U.S. 157, "envisages

itself the necessity, under circumstances of genuine and irretriev

able damage, for affording equitable relief even though the result

is to forbid criminal prosecution or other legal proceedings." 235

F.2d at 485. See also, American Optometric Ass’n. v. Ritholz, 101

F.2d 883, 887 (7th Cir. 1939); Jamison v. Alliance Ins. Co. of

Philadelphia, 87 F.2d 253, 256 (7th Cir. 1937).

This Court has subsequently indicated that the doctrine of

comity, which is the basis for Section 2283, is not applicable in

4/ , ,

civil rights cases. In Morrison v. Davis, 252 F.2d 102, 103 (5th

Cir. 1958), cert, denied, 356 U.S. 968 (1958), the Court said:

This is not such a case as requires the withholding

of federal court action for reasons of comity, since for

the protection of civil rights of the kind asserted

Congress has created a separate and distinct federal

cause of action. * * * Whatever may be the rule as

to other threatened prosecutions, the Supreme Court in

a case presenting an identical factual issue affirmed

the judgment of the trial court in the Browder esse

[Browder v. Gayle, D.C.M.D.Ala., 142 F. Supp. 707,

affirmed 1956, 352 U.S. 903, 77 S.Ct. 145, 1 L.ed. 2d

114] in which the same contention was advanced. To

the extent that this is inconsistent with Douglas v.

City of Jeannette, Pa., 319 U.S. 157, 63 S.Ct. 877,

87 L.ed. 1324 we must consider the earlier case modified.

This language was repeated in U.S. v. Wood, 295 F.2d 772,

784 (1961) where this Court at the request of the United States,

enjoined the prosecution of a Negro charged with breach of the

peace as a result of voter registration activities. The Court there.

finding that the prosecution would intimidate qualified Negroes

from attempting to register and vote, held that Section 2283 did

not bar injunction requests made by the government, and that under

4/ Section 2283 does not go to the jurisdiction of a federal court,

but is an affirmation of the rules of comity, Smith v. Appfre,

264 U.S. 274; Wells Fargo & Co. v. Taylor, 254 U.S. 175.

13

the circumstances of the case, the comity rule of Douglas v. City

of Jeannette, supra. was inapplicable.

Judge Rives of this Court, dissenting in Bailey v. Patterson.

199 F. Supp. 595, 616 (S.D. Miss, 1961), observed that enjoining

prosecutions similar to those involved here "is not so much an

exception as a practical application of the Jeannette requirement of

• adequacy.1" The alternative to this suit, as Judge Rives stated:

...is that a great number of individual Negroes

would have to raise and protect constitutional

rights through the myriad procedure of local

police courts, county courts and state appellate

courts, with little prospect of relief before

they reach the United States Supreme Court.

Appellees, moreover, are hardly on firm ground in throwing

up the shield of comity as a defense against the relief sought by

appellants. They have shown little respect for the decisions of

federal courts invalidating racial segregation in public facilities,

and indeed have been enjoined by state statute, 17 Miss. Code Ann.

§4065.3:

...to prohibit by any lawful, peaceful and

constitutional means, the implementation of

or the compliance with the Integration

Decisions of the United States Supreme

Court...

Appellees have assumed this obligation wholeheartedly, and without

regard to either the constitutional rights of appellants and the

class they represent, or the respect for the doctine of comity,

which here they seek to invoke as a bar to relief made necessary

by their illegal activity.

In such a situation, it is appropriate, proper, and

necessary that the relief sought by appellants be granted.

14

II

APPELLEES, BY ENFORCING RACIAL SEGREGATION REQUIRED

BY STATE LAW, HAVE ABRIDGED APPELLANTS’ CONSTITUTIONALLY

PROTECTED FREEDOMS OF EXPRESSION AND ASSEMBLY AND HAVE,

THEREBY, CREATED AN EMERGENT SITUATION NECESSITATING

INTERIM INJUNCTIVE RELIEF BY THIS COURT.

Appellants seek here this Court’s aid in vindication of their

constitutional right to peacefully protest the refusal of appellees

and other officials of the State of Mississippi to abandon their

policy of racial segregation.

Each of the individual appellants have been arrested by

appellees while attempting to peacefully exercise their right to

protest, and some have been enjoined by a state court at the request

of appellees from participating in protest demonstrations against

racial segregation.

The corporate appellant asserts the rights of its members,

NAACP v. Alabama. 357 U.S. 458, to associate together and to

advocate, in concert, their right to equal treatment under the law,

their right to be free of segregation and racial discrimination and

their right to espouse their convictions through litigation and all

peaceful means. Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U.S. 516; Gremillion v.

NAACP. 366 U.S. 293; NAACP v. Button. 371 U.S. 415; Gibson v.

Florida Legislative Investigative Committee. 342 U.S. 539.

It represents its members, supporters and like-minded people,

and seeks in this action to end racial intolerance and discrimination

rampant in the State of Mississippi, and obtain judicial relief from

the onerous sanctions of the State which restrict activity to secure

6/

rights guaranteed by the Constitution of the United States.

5/ Appellant National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People is a non-profit membership corporation of the State of New

York that functions through chartered unincorporated affiliates

designated as branches. Its aims and purposes are to eliminate

racial discrimination and segregation from the pattern of American

life through peaceful and lawful means.

6/ The corporate appellant has, through litigation, vindicated the

rights of Negroes to vote, Smith v. Allwright. 321 U.S. 649,

Gomillion v. Lightfoot. 364 U.S. 339; to equal educational oppor

tunities, Brown v. Board of Education. 347 U.S. 483, Sweatt v.

Painter. 339 U.S. 629; to serve on grand and petit juries,

Shepherd v. Florida, 341 U.S. 40; and to unsegregated interstate

travel, NAACP v. St. Louis & San Francisco Rv. Co.. 297 I.C.C. 335;

and intrastate travel, Browder v. Gayle. 352 U.S. 903.

15 -

A. Consistent With State Policy, Appellees Have

Violated Appellants' Constitutional Rights

By The Enforcement Of Racial Segregation.

It is now settled that state action which enforces racial

segregation offends the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment whether accomplished through the judiciary, Shelley v.

Kraemer. 334 U.S. 1; the executive and administrative arm, Monroe v.

Pape. 365 U.S. 167; Screws v. United States. 325 U.S. 91; or the

legislature, Gayle v- Browder. 352 U.S. 903. Racial discrimination

can bear no rational relationship to any permissable governmental

functions, and its enforcement by governmental officials, therefore,

violates the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment,

Cooper v. Aaron. 358 U.S. 1, and the Fifth Amendment, Bolling v.

Sharpe. 347 U.S. 497. This constitutional proscription extends to

the use of trespass and breach of the peace laws to maintain

segregation and to the enforcement of ordinances to render con

stitutionally protected peaceful protests "crimes."

But, despite the United States Constitution, decisions of the

United States Supreme Court, and decisions of this Court, the laws

of Mississippi requiring and compelling racial segregation are

affirmatively and aggressively maintained. The Mis sissippi policy

of defiance is accurately reflected in § 4065.3 of the Mississippi

Code of 1942, Ann., which directs the entire executive branch of

government of the State of Mississippi, and all of its sub-divisions,

and all persons responsible thereto in state and local government,

to prohibit compliance with the "Integration Decisions of the

United States Supreme Court" of May 17, 1954 (347 U.S. 483) and of

May 31, 1955 (349 U.S. 294) to prohibit integration of Negroes and

whites in all public places of amusement, recreation or assembly

according to the Resolution of Interposition, Senate Concurrent

Resolution No. 125, adopted by the Mississippi Legislature on

February 29, 1956. This section further promises that the statute

itself shall be a defense to any civil or criminal suit brought

against state officers or agents by any person or by the Federal

Government of the United States. The trespass statute employed to

16 -

effect arrests, §2409.7, Mississippi Code of 1942 Ann., is one of

the "segregation laws: adopted in 1956 as a part of a program of

resistance to the desegregation decision in Brown v. Board of

Education. 347 U.S. 483, and as reaffirmation of racial segregation

as part of the law, customs and policies of Mississippi.

Segregation is required by Mississippi Constitution, §225;

and by the following sections of the Code of Mississippi: §7786

(segregation of races on streetcars and buses); §§ 4259, 7913, 7965,

7971 (segregation of races in prisons); §§ 6882, 6883 (separate

mental wards); §2351.5 (separate rest rooms in railroad and bus

station waiting rooms for interstate passengers); §2056(7) (punishes

any conspiracy to violate the segregation laws of the state);

§3499 (unlawful for taxicabs to transport whites and Negroes

together); §7787.5 (requires construction of separate waiting

rooms by all common carriers for intrastate passengers); §2339

(misdemeanor to publish or advocate the social equality of the

races); §4065.3 (requires all state officers to utilize their

office to maintain segregation of the races.)

Although couched in innocuous terms, application of the

ordinances and statutes to appellants and to the members of the

class they represent under the circumstances of this case, effectuate

segregation. The arresting officers are public officials of the

State of Mississippi purporting to act within the scope of their

authority. Although the Fourteenth Amendment erects no shield

against private discrimination, by making the arrests complained of

by appellants, officials of the State have interposed themselves

between private prejudice and actual suppression of constitutional

rights, and have thereby, become the agent whereby racial segregation

is enforced. Thus is the proscription of the equal protection

clause offended.

In the course of his testimony, Mayor Thompson testified

that the City of Jackson would "protect" the "right" of places of

public accommodation to discriminate against Negro patrons [Tr. 67].

17

Adherence to historical patterns of segregation established

by the state cannot be dismissed as private discrimination or

obedience to custom unrelated to the State. Although segregation

laws may no longer be enforced, as such, the policies they dictate

are compelled by arrests, by the statements of intention to perpetua

segregation by the Governor of Mississippi and by prosecution and

convictions for breach of the peace, parading without a permit and

similar apparently innocuous laws achieved through a cooperative

judiciary. Absent these factors, proprietors of places of public

accommodation have no material private interest in the maintenance

of segregation. It is the power of the State which supports these

customs, enunciates policy and in fine, fosters and enforces

segregation of the races.

18

c r

B. Appellants’ Protest Activities Are Protected

By Their Constitutional Right of Freedom Of

Expression and Assembly

Appellants seek to protect from interference by appellee

authorities, those activities delineated in paragraph 6 a,b,c, and

d of the verified complaint which include peaceful picketing,

requests for service at lunch counters and restaurants, orderly

protest processions and public prayer services, all of which may

be characterized as public protests against the customs, practices,

and laws compelling racial segregation in Jackson, Mississippi,

All of these activities are embraced within constitutionally pro

tected rights to freedom of speech, to freedom of assembly or to

petition for redress of grievances.

Appellants espouse a lawful cause. Their picketing was

peaceful, their requests for service, orderly, their protest

procession without violence or interference with municipal func

tions, and their public prayer, tranquil. Neither violence nor

interruption of the public peace can be attributed to appellants.

The fundamental rights guaranteed by the First Amendment

include peaceful picketing, Thornhill v, Alabama. 310 U.S. 86, dis

seminate m of handbills, Martin v. Struthers. 319 U.S. 141, group

rights to associate, NAACP v. A labama, supra. and to advocate

dissident views Bates v. Little Rock, supra . solicitation of

political allies, Herndon y, Lowry. 301 U.S. 242, freedom to

proselytise, Cantwell v. Connecticut. 310 U.S. 296, unrestrained

publication, Grosjean v. American Press Co.. 279 U.S. 233, and

silent displays of personal convictions, Stromberq v, California.

283 U.S. 359.

The stateb power to limit freedom of expression must be

exercised within the "clear and present danger of substantive evil"

doctrine, Schenck v. U.S.. 249 U.S. 47, Protest against municipal

and state racial segregation policies is not within the "substan

tive evil" which the state may suppress. Cooper v, Aaron, 358

u*s * 1; Sellers v. Johnson, 163 F„2d 877 (8th Cir. 1957). There

19 -

is absent, in the circumstances before this Court, any clear and

present danger of riot or disturbance which would invite preventive

action on the part of the City of Jackson. Compare, Edwards v.

South Carolina. 372 U.S. 229 and Feiner v. New York. 340 U.S.

315.

Within the rational of these cases and of well-settled law,

falls the right of appellants to peacefully picket places of

public accommodation and to carry placards protesting the exclu

sion of Negroes, People v. Kiernan. 26 N.Y.S. 2d 291 (1940);

People v. Barkel. 36 N.Y.S. 2d 1011 (1942); Milk Wagon Drivers

v. Meadow Moor Dairies. 321 U.S. 287; Plumbers Union v„ Graham.

345 U.S. 192; Hughes v. Superior Court. 339 U.S. 460; Teamsters

Union v. Vogt. 354 U.S. 284; Watchtower and Bible Tract Society

v. Dougherty. 337 Pa. 286, 11 A. 2d 147; New Negro Alliance v.

Sanitary Grocery Co.. 303 U.S. 552; the right to participate in

orderly protest marches and to carry signs advocating the end of

racial segregation, Edwards v„ South Carolina, supra; the right

to enter places of public accomodation to request food service on

a racially integrated basis and to remain on the premises follow

ing a refusal of service to silently protest segregation; Peterson

v._City of Greenville, 31 U.S.L, Week 4475 (1963); Lombard v.

State of Louisiana. 31 U.S.L. Week 4476 (1963); and the right to

participate in orderly public prayer services as a means of ex

pressing their dissatisfaction with a segregated social order.

Fowler v. Rhode Island. 345 U.S. 67; Kunz v. New York, 340 U.S.

299, cf, Edwards v. South Carolina, supra.

The record reflects that on May 13, 1963, approximately

three weeks prior to and in anticipation of the commencement of

protests by appellants and the class they represent, appellees

converted exhibit buildings on the county fairgrounds into addi

tional prison facilities. Immediately upon their appearance on

public streets to exercise their right to freedom of expression,

appellees and their agents abruptly quelled the attempts of

appellants and members of their class to communicate and publicize

20

their discontent with enforced segregation in Jackson and in

Mississippi by arrest and incarceration. After instituting this

program whereby the right of free speech was effectively abolished,

appellees proudly denominated it as "instant arrest."

The "instant arrest" policy of the Jackson police belies

any motivation other than to intimidate and extinguish attempts

of Negro citizens to disagree openly with practices of segregation,,

Although First Amendment rights may be balanced against legitimate

interests of the State, these rights become absolute when weighed

against the state’s attempts to maintain a segregated way of life.

"A State may not unduly suppress free communication of views...

under the guise of conserving desirable conditions." Cantwell y.

Connecticut, supra. The arrests in the instant case cannot escape

the condemnation meted out to legislation in Thornhill v..Alabama.

supra; Schneider v» State f wsaim J1 Kunz v. New York, 340 U.S. 290.

They constitute an invalid prior restraint upon the exercise of

freedom of expression and assembly guaranteed by the constitution.

Near v. Minnesota. 283 U.S. 697; Herndon v. Lowry, supra: DeJonge

v. Oregon, 299 U.S. 353.

21

C. The Urgent Relief Sought By Appellants Is

Justified By The Circumstances Of This Case.

Events, since the desegregation decision of 1954, have shown

that when the officials or executive officers of a state act in

arrogant disregard of the law, there is evoked on the part of the

populace, violently aggressive acts of hostility to any change in

the social order to which they have become conditioned. Conversely,

in those instances where the state has acted responsibly, in com

pliance with the law, orderly changeovers have been effected and

accepted by the public.

Appellees and other officials of the State of Mississippi

have failed to follow or to initiate compliance with the desegre

gation decisions of the courts, have actively dexied tnese decisions

and have formulated and effectuated policies purposed to stifle

even peaceful expressions of opposition to racial segregation. The

Negro in Mississippi has endured racial segregation and discriminate r

although those practices have been declared to be unconstitutional.

Appellees, through arrests, harassment and intimidation, have sought

to and have succeeded in suppressing even the right of the Negro to

object to his political and social servitude.

Abdication of appellee authorities from enforcement of the

law has created a climate of lawlessness which has already resulted

in the murder of one of the plaintiffs and which will continue unless

this Court acts to restrain and enjoin appellees abuse of criminal

and civil process.

It is incumbent upon this Court to weigh preservation of

appellants’ constitutionally protected rights in an emergent situ

ation against the interest of the state in preserving and protecting

an unlawful social order by violent, threatening and intimidating

harassment which creates that emergency. The daily attrition of

appellants’ fundamental rights is coerced by the use of state power

to quench peaceful pretests against racial segregation. Whereas

appellants will be amenable to state process following determination

of an appeal on the merits, appellants' rig’nt to protest, stifled

today, cannot be recovered tomorrow. Whereas the state sustains no

injury through cessation of the arrests and prosecution* Inflicted

22 -

on appellants, the impairment of their rights and the burden cast

upon them through use of the civil and criminal process of the state

is irremediable. A temporary injunction is essential to the preser

vation of clear, settled fundamental rights of appellants and to

an end to the critical period of violence and suppression precipitated

by state authorities.

Appellees have summoned all available means to maintain rigid

racial segregation in the City of Jackson, the State of Mississippi.

They have adopted laws which convert attempts of Negroes to eliminate

segregation into crimes and have prosecuted those "criminal"

activities. They have instituted and pursued a policy of "instant

arrest" to suppress appellants’ constitutionally protected right

to protest segregation. They have utilized the criminal machinery

of the State to penalize advocation of equal rights for Negroes.

In short, they have perverted the orderly forces of law and order

and converted them into weapons for the suppression of constitutional

rights and the enforcement of an archaic and unlawful social order.

They have abrogated the right to be free of racial segregation by

the abridgement of the right to speak, to inform and to protest and

have done severe violence and damage to the United States Constitution

from which flows those inalienable rights guaranteed by the founders

of this country to all peoples without regard to the color of their

skin. They have, by oppression and tactics of terror, produced an

atmosphere of suppression of human rights worthy of the dark ages.

Appellants seek no more than that which has been promised and

guaranteed to them for the last hundred years. They seek, from this

Court, the only available remedy which will vindicate and preserve

their fundamental rights.

23 -

Conclusion

For the reasons advanced herein, it is respectfully submitted

that, pending appeal of this cause, appellees be temporarily

enjoined from abrogating appellants' constitutional rights in order

to enforce racial segregation in Jackson, Mississippi.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack H, Young

Carsie A. Hail

115^ North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi

Robert L. Carter

Barbara A. Morris

20 West 40th Street

New York 18, New York

R. Jess Brown

125^ North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi

Jack Greenberg

Leroy D. Clark

Derrick A. Bell

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Frank D. Reeves

508 Fifth Street, N. W.

Washington 1, D. C.

William R. Ming, Jr.

123 West Madison Street

Chicago, Illinois

Attorneys for Appellants

By:

Dated: June 24, 1963.

24