Dokes v. Arkansas Abstract and Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Dokes v. Arkansas Abstract and Brief for Appellant, 1966. 4e0c07fb-af9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0eb03427-b936-4482-ab36-4b1014f52cae/dokes-v-arkansas-abstract-and-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

N / Q

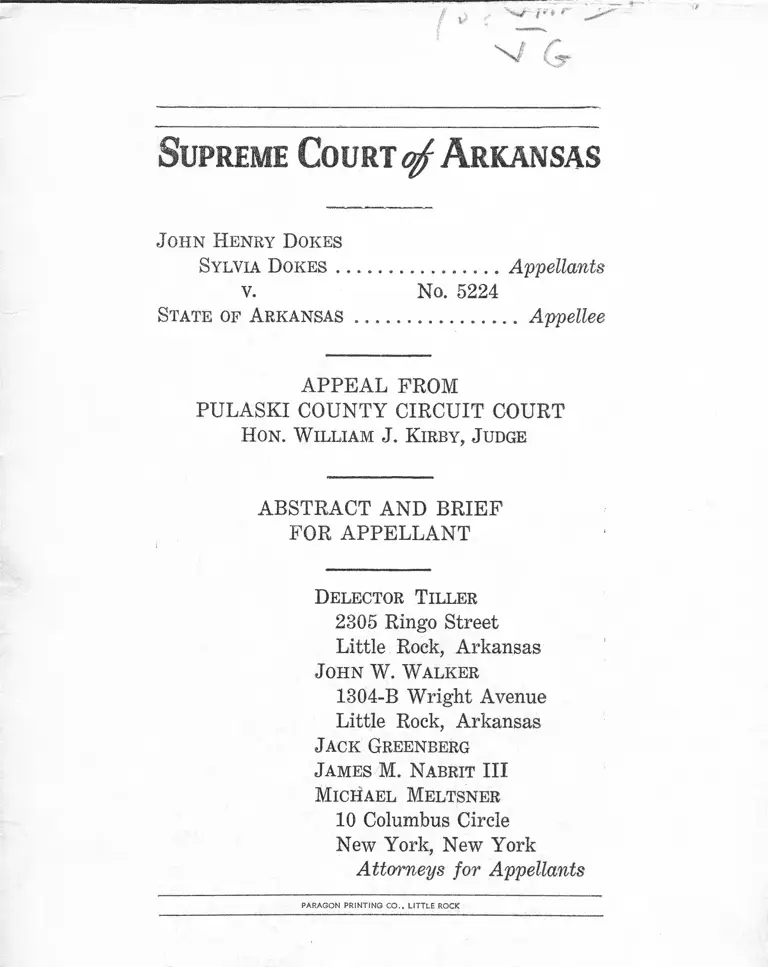

Supreme Court q f A rkansas

John Henry Dokes

Sylvia Do k e s ................................. Appellants

v. No. 5224

State of A r k a n s a s ............................... Appellee

APPEAL FROM

PULASKI COUNTY CIRCUIT COURT

Hon. W illiam J. Kirby, Judge

ABSTRACT AND BRIEF

FOR APPELLANT

Delector Tiller

2305 Ringo Street

Little Rock, Arkansas

John W . W alker

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit III

Michael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Attorneys for Appellants

PARAG ON PR IN T IN G CO.. L ITTLE ROCK

INDEX

Page

Statement of Case ________________________________________ 1

Points Relied On --------------------------------------------------------------- 3

Abstract of Pleas ------------------------------------------------------------- 5

Plea and Arraignment ------------------------------------------------- 5

Motion to Dismiss ------------------- 5

Motion to Suppress Evidence --------------------------------------- 9

Order Overruling Motion to Dismiss and Motion

to Suppress Evidence ------------------------------------------ 10

Testimony For State of Arkansas ------------------------------------- 12

Officer Jim Harris ------------------------- ------------------------- 12

Officer John Terry ---------------------------------------------------- 14

Officer Ralph Parsley ----------------------------------------------- 15

Testimony For Defendants ________________________________ 16

John H. Dokes ------------------------------------------------------------ 16

Sylvia Dokes __________________________________________ 17

Robert Hampton --------------------------------------------------------- 17

Claude Taylor -------------------------------------_--------------------- 18

Trial Verdict and Judgment -------------------------------------------- 21

Motion For New Trial ------------------------------------------------------- 22

Motion For New Trial Overruled --------------------------------------- 25

Argument ___________________________ —----------- >----------------- 26

Conclusion --------------- --------------------------------------------------------- 50

Supreme Court oft A rkansas

John Henry Dokes

Sylvia Do k e s ..................................Appellants

v. No. 5224

State of A rkansas Appellee

APPEAL FROM

PULASKI COUNTY CIRCUIT COURT

Hon. W illiam J. Kirby, Judge

ABSTRACT AND BRIEF

FOR APPELLANT

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Appellants, a married couple, were arrested

on January 30, 1965, at their home, 287 Granite

Mountain Circle, Little Rock, Arkansas, and

charged with contributory delinquency, under

§45-239 of Arkansas Stat. Annot., after police

officers of the City of Little Rock had entered

their apartment without a search or an arrest

warrant.

2

After pleading not guilty to the charges

against them, appellants were tried in the Mu

nicipal Court of Little Rock May 4, 1965, found

guilty and fined $25.00 plus $10.50 costs each.

On appeal to the Circuit Court of Pulaski County,

motions to dismiss the informations and to sup

press evidence were overruled by the Circuit

Court. Appellants were tried before Hon.

William J. Kirby and a jury on April 8, 1966,

were found guilty and fined $200.00 each.

Motion for New Trial was overruled.

3

POINTS RELIED UPON

I

Appellants are denied due process of law as

guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment

to- the Constitution of the United States be

cause there is no evidence in the record to

support their convictions.

II

The statute under which appellants were con

victed is so vague and uncertain as to violate

the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

h i

The admission of testimony regarding observa

tions by police officers inside a home entered

without warrant or probable cause violated

the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments to

the Constitution of the United States.

4

The convictions for contributing to the delin

quency of a minor violate the due 'process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States because no

alleged delinquent minor was ever identi

fied.

IV

V

Appellants have been denied due process of law

as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United

States because they were convicted upon an

information and charge to the jury drawn

from statutes rendered inapplicable by

amendment prior to their trial.

VI

Appellants have been denied their rights under the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States because their arrest and

conviction was motivated by racial consid

erations.

5

ABSTRACT

; PLEA AND ARRAIGNMENT

(T.7)

Pulaski Circuit Court — First Division —

March Term, 1966, Monday, June 14, 1965.

State of Arkansas

64749 vs. 64750 Contributory Delinquency

Sylvia Dokes (CF)

John Henry Dokes (CM)

This day comes the State of Arkansas by

Philip Ragsdale, Assistant Prosecuting Attorney,

and comes the defendant in proper persons and

by their attorney, Delector Tiller, and defendants

are called to the bar of the Court and informed

of the nature of the charge filed herein, enter

their pleas of not guilty thereto, and by agree

ment the cases are passed to the September set

ting.

NOTION TO DISMISS

(T .18-19)

The defendants hereby make a special ap

pearance for the purpose of moving that the

charges against them be dismissed for the reasons

that follow:

6

1. The alleged. arrest under color of state

law of the defendants and any possible conviction

connected therewith will constitute a violation of

the defendants’ right to peaceably assemble with

members of another race in their own home as

guaranteed by U. S. Const, amend. 1 & 14 Sec. 1

and Ark. Const. Art. 2 Sec. 4 because there was

no legal justification for the arrest but rather the

defendants were arrested solely because they per

mitted a peaceable inter-racial gathering in their

home.

2. The alleged arrest1 under color of state

law of the defendants and any possible conviction

therewith will constitute a violation of the de

fendants’ right to due process of law as guar

anteed by U. S. Const, amend. 5 and 14 Sec. 1

and Ark. Const, of Ark. Art. 2 Sec. 2 & 8 because

there was no legal justification for the arrest but

rather the defendants were arrested solely be

cause they permitted a peaceable inter-racial gath

ering in their home.

3. The alleged arrest under color of state

law of the defendants and any possible convic

tion connected therewith will constitute a violation

of the defendants’ right to equal protection of the

laws as guaranteed by U. S. Const. Amend. 14

Sec. 1 and Ark. Const. Art 2 Sec. 3 because there

was no legal justification for the arrest but rather

the defendants were arrested solely because they

7

permitted a peaceable inter-racial gathering in

their home.

4. The alleged arrest under color of state

law of the defendants and any possible convic

tion connected therewith will constitute a viola

tion of the defendants’ right to be protected

against unreasonable search and seizure as guar

anteed by U. S. Const amend. 4 & 14 Sec. 1 and

Ark. Const. Art. 2 Sec. 15 because there was no

legal justification for the arrest but rather the

defendants were arrested solely because they per

mitted a peaceable inter-racial gathering in their

home.

5. The alleged arrest under state law of the

defendants was invalid because (s) no warrant

of arrest was issued or deliever to any peace o ffi

cer prior to the alleged arrest; (2) the defendants

did not commit any public offense in the presence

of any peace officer; and (3) no peace officer had

any reasonable ground to believe that defendants

had committed a felony. See Ark. Stats. Ann.

Sec. 43-403 (Repl. 1964).

6. The alleged arrest under color of state

law of the defendants was invalid because: (1)

the persons who made the alleged arrest did not

inform the defendants of their authority; (2) the

persons who made the alleged arrest did not in

form defendants of the offense charged against

8

them; (8) the persons who made the alleged

arrest were not acting on a warrant of arrest

and did not give information thereof or show any

warrant of arrest. See Ark. Stats. Ann. Sec.

43-416 (Repl. 1964).

6. The alleged arrest under the color of

state law of the defendants was made without an

arrest warrant and the defendants were not car

ried forthwith before the most convenient magis

trate of the county where the alleged arrest was

made, and the grounds on which the alleged ar

rest was made were not statjd to the magistrate.

See Ark. Stats. Ann. Sec. 4;f-601 (Repl.).

Dated: April 8, 1966

s / Delector Tiller

Delector Tiller, Attorney

for Defendants

2305 Ringo St. LRA

FR 6-2132

Filed:

May 23, 1966

Roger McNair, Circuit Clerk —

9

MOTION TO SUPPRESS EVIDENCE

(T.20)

The defendants captioned above hereby make

special appearance for the purpose of moving to

suppress and exclude any evidence obtained from

the premises at 287 Granit Mountain Circle,

Little Rock, Arkansas, on or about January 30,

1965, for the following reasons:

(a) The evidence that was obtained was

obtained in violation of the statutory and com

mon law of Arkansas and is thereby inadmissa-

ble because (1) no search warrant was executed

by a public officer as required by Ark. Stats.

Annotated Sec. 43-201 (Repl. 1964) or any other

statute nor was any search warrant directed to

a peace officer as required by Ark. Stats. Ann.

Sec. 43-202 (Repl. 1964) or any other statute,

nor was any search warrant served pursuant to

law authorizing any search of the premises or

seizure of evidence; and (2) no lawful arrest

was made in connection with the search and

seizure as required by Ark. Stats. Ann. Sec. 42-

403 (Repl. 1964).

(b) The evidence that was obtained was

obtained in violation of the defendants’ consti

tutional guarantee against unreasonable search

and seizure as provided in Ark. Const. Art. 2 Sec.

14 and is thereby inadmissable.

10

(c) The evidence that was obtained was

obtained in violation of the defendants’ constitu

tional immunity against unreasonable searches

and seizure as provided in U. S. Const. Amend.

4 and 14 Sec. 1 and is thereby inadmissable.

Date: A p ril8,1966.

s / Delector Tiller

Delector Tiller, Attorney

for defendants

Filed:

May 23, 1966

Roger McNair, Circuit Clerk

By: s / D. L. Shook, Deputy Clerk

ORDER OVERRULING MOTION TO DISMISS AND

MOTION TO SUPPRESS EVIDENCE

(T.20-A)

Pulaski Circuit Court — First Division —

March Term, 1966, Wednesday, May 23, 1966

State of Arkansas

64749 vs. 64750 Contributory Delinquency

Sylvia Dokes (CF)

John Henry Dokes (CM)

This day comes the State of Arkansas by

Philip Ragsdale, assistant Prosecuting Attorney,

11

and comes the defendants in proper persons and

by their attorney, Delector Tiller, and Motion to

Suppress evidence and Motion to Dismiss are

filed and heard, and overruled, and the Defend

ants’ Exceptions are saved.

12

ABSTRACT OF TESTIMONY

Given at trial in the Pulaski Circuit Court,

April 8, 1966 (T.22-91).

I. TESTIMONY FOR THE STATE OF ARKANSAS

O f f ic e r J im H a r r is (T .24-38):

I am a member of the Little Rock Police De

partment and also employed as a night watchman

for the Little Rock Housing Authority (T .25).

On January 30, 1965, a Saturday night, I was in

my own automobile at the edge of the Booker

Home Project (T.25) where I could observe all

traffic entering or leaving the project (T .30-31).

About 11:00 p. m. my attention was attracted

by a string of cars with white occupants entering

the project (T.25, 35-36). I was not certain

that they were breaking any law by entering the

project but I felt it was my duty to investigate

(T .32). If it had been Negroes entering the

project my attention would not have been at

tracted to the point of making as thorough an

investigation (T .35-36). I

I also saw what appeared to be white teen

agers go into a liquor store about 200 yards away

and then return to the project. I spoke to the

owner of the store (T.26) who told me that they

had purchased a bottle of rum and some beer

13

(T .33). I then ascertained that the cars I had

seen entering the project were parked just o ff

Granite Mountain Circle. I returned to the

liquor store and telephoned the Vice Squad (T.

26-27). Officers Terry and Parsley came to the

project and we went to the apartment where I

thought there was a congregation (T .27). No

complaint of disturbance had been made, al

though there were other families living next to

the apartment (T .35). We saw two white males

and a colored female come out of the apartment.

We identified ourselves as police officers. The

colored female we met outside the apartment,

Sylvia Dokes, made no objection to our going in

to the apartment (T .27). We had no search war

rant (T .35). I do not recall whether I said to

her, “ Take me to the party” (T .31).

There were twenty-two people, both colored

and white, in the apartment (T .28). There

were several people singing into a tape recorder

(T .34 ). I heard no cursing or obscene language

and no one was loud or rowdy (T.35). I do not

know whether there were any unescorted females

in the apartment (T .34).

There were cans of beer in various locations

about the apartment and apparently mixed

drinks in the kitchen (T .28). I did not see any

minor take a drink of whiskey, or any of the

defendants give a drink of whiskey to a minor

14

(T .37). I did not see the defendants drink any

whiskey (T.37).

We talked to various boys and girls to get

their names and ages and we took all 22 persons

in the apartment to police headquarters (T.29-

30).

Officer John Terry (T. 39-51):

I was a member of the Little Rock police

force on January 30, 1965 (T .39). On that date

I was called to the Granite Mountain Project by

Officer Harris (T .39). Officer Parsley and

I met him in front of the liquor store across the

street from the project and we went to 287

Granite Mountain Circle. We found three

people coming out of the apartment at that ad

dress and “ we stopped them and took them back

to the apartment” (T .40), Mrs. Dokes ad

mitted us to the apartment after I identified my

self as a police officer (T .41).

When I went into the apartment I saw

Schlitz beer in the kitchen and in the living room

(T.41, 45). Several people were singing (T.

41). I saw a young girl sitting on a couch with

a glass containing ice and liquor in her hand

(T .41). Her name was Janet Kirspel, a 19-

year-old white girl (T .42). I picked up the

glass and asked her if it were hers, but Sylvia

Dokes stated to me that it was her (Mrs. Dokes’ )

15

drink (T .42 ). I did not observe Mr. or Mrs.

Dokes ask any minors who were present to leave

their apartment; nor did I observe them take any

beer away from any minors (T .49).

I did not see any person in the apartment

take a drink of any whiskey and I did not see any

defendant give a minor a drink of whiskey (T.46,

48). Some of the minors had the odor of alco

hol on their breath when I was questioning them

(T .50). After occupants of the apartment were

interviewed at police headquarters (T .43). The

minors were charged with possessing alcoholic

beverages and the adults were charged with con

tributing to the delinquency of minors (T.43,

44).

Officer Ralph Parsley (T .51-56):

I was a member of the Little Rock Police De

partment on January 31, 1965 (T .52). On that

evening, I answered a call from the Booker Home

Project. When I arrived at the apartment of

Mr. and Mrs. Dokes I observed beer and mixed

drinks and heard music (T .52). We had no

search warrant nor arrest warrant (T .55).

Some of those in the apartment were minors.

The youngest person was a 14-year-old girl, who

had an odor of alcohol on her breath (T.53).

Robert Hampton, an adult, stated that he had

been drinking (T.53). In the time I was in the

16

apartment I did not see Mr. and Mrs. Dokes

bar any minor from coming into the apartment

or take any alcoholic beverages away from them

(T .54). I did not see any of the defendants

give any of the minors any whiskey (T .56).

II. TESTIMONY FOR DEFENDANTS

John H. Dokes (T .58-67):

I was trying to get a Negro singing group

together and two friends who worked with me,

James Charton and Paul Schmolke, asked if they

could listen to us rehearse, and if they could

bring dates. I said it would be all right (T.58-

59). I was expecting them on January 30, 1965

but Charton’s younger brother and a friend both

showed up with dates even before James Charton

came, and they asked to come in (T .59). I

didn’t turn them down because of their race.

Later during the evening other whites came over,

all friends of Charton and Schmolke (T. 59).

All the whites had dates (T .65). I didn’t invite

them, but only James Charton and Paul Schmolke

(T .67). I didn’t ask any of them to leave be

cause I had no reason to. My house is open to

visitors T.66). There were twenty-two people

in the apartment (T .64). I don’t know how old

the guests were and I did not ask them (T.63).

James Charton went out and brought back

some beer which he put in my icebox. Another

17

white male adult came with a partly empty bot

tle of rum (T .60). My singing group, which

was just getting started and did not have a name

yet (T.62) was singing into a tape recorder in

the pantry (T .61). I did not see any minors

with whiskey nor did I give whiskey to any minor

(T .63 ).

Sylvia Dokes (T .68-72):

The people were at my apartment that night

to listen to my husband’s group practice (T .68).

I knew that Miss Kirspel was 19 but I didn’t

know the age of Jenifer Brewer or Susan Brewer

(T .69). I couldn’t tell the ages of the white

girls (T .70). I did not see any minors drinking

(T .71). I neither gave them any drinks nor

ordered them out of my house (T .70).

The police told me to take them back where

I came from (T .71). I did not invite the offi

cers into the house and I did not demand to see a

warrant (T .72).

Robert Hampton (T .81-86):

I went to the Dokes’ apartment on January

30 to attend a rehearsal of the singing group (T.

81). I was singing most of the evening (T.84).

I had never met most of the people before other

than the members of the group (T.85). I did

not see the Dokes ask any of the people to leave

18

(T .84). I did not see any minors drinking. I

did not see any adult give any minor beer or

whiskey (T .84).

Claude Taylor (T .86-88):

I was not a member of the singing group but

I came as an advisor. I had my own singing

group at the time and was under contract with a

recording company (T .87).

The State’s Requested Instruction No. 1

(T .73-74)

Any person who shall, by any act, cause, en

courage or contribute to the dependency or de

linquency of a child, as these terms with reference

to children are defined by this act, or who shall,

for any cause, be responsible therefor, shall be

guilty of a misdemeanor and may be tried by any

court in this State having jurisdiction to try and

determine misdemeanors and, upon conviction

therefor, shall be fined in a sum not to exceed

five hundred dollars ($500.00), or imprisonment

in the county jail for a period not exceeding one

(1) year, or by both such fine and imprisonment.

When the charge against any person under this

act concerns the dependency of a child or children,

the offense, for convenience, may be termed con

tributory dependency; and when it concerns the

delinquency of a child or children, for convenience

it may be termed contributory delinquency. Pro

19

vided, however, that the court may suspend any

sentence, stay or postpone the enforcement of

execution or release from custody any person

found guilty in any case under this act when, in

the judgment of the court, such suspension or

postponement may be for the welfare of any de

pendent, neglected or delinquent child as these

terms are defined by this act, such suspension or

postponement to be entirely under the control

of the court as to conditions and limitations.

The Court gave the State’s Requested

Instruction No. 1.

The defendants objected to the action

of the Court in giving the State’s Requested

Instruction No. 1, and at the time asked

that their exceptions be noted of record,

which was accordingly done.

The State’s Requested Instruction No. 2

(T .75-76)

The words “ delinquent child” shall mean any

child, whether married or single, who, while

under the age of eighteen (18) years, violates a

law of this State; or is incorrigible, or knowing

ly associates with thieves, vicious or immoral

persons; or without just cause and without the

consent of its parents, guardian or custodian ab

sents itself from its home or place of abode, or is

20

growing up in idleness or crime; or knowingly fre

quently visits a house of ill-repute; or knowingly

frequently visits any policy shop or place where

any gaming device is operated; or patronizes,

visits or frequents any saloon or dram shop where

intoxicating liquors are sold; or patronizes or

visits any public pool room where the game of

pool or billiards is being carried on for pay or

hire; or who wanders about the streets in the

nighttime without being on any lawful business

or lawful occupation; or habitually wanders

about any railroad yards or tracks or jumps or

attempts to jump on any moving train, or enters

any car or engine without lawful authority, or

writes or uses vile, obscene, vulgar, profane or

indecent language or smokes cigarettes about

any public place or about any schoolhouse, or is

guilty of indecent, immoral or lascivious conduct;

any child committing any of these acts shall be

deemed a delinquent child.

The Court gave the State’s Requested

Instruction No. 2.

The defendants objected to the action

of the Court in giving the State’s Re

quested Instruction No. 2, and at the time

asked that their exceptions be noted of

record, which was accordingly done.

21

TRIAL VERDICT AND JUDGMENT

(T.10)

Pulaski Circuit Court — First Division

March Term, 1966

Friday, April 8, 1966

State of Arkansas

G4749 & 64750 Contributory Delinquency

Sylvia Dokes (CF)

John Henry Dokes (CM)

This day comes the State of Arkansas by

Mrs. Virginia Ham, Assistant Prosecuting At

torney, and come the defendants in proper per

sons and by their attorney, Delector Tiller, and

pleas of not guilty having previously been entered

parties announce ready for trial, thereupon comes

twelve qualified electors of Pulaski County, viz:

Tom Oakley, Roy Beard, H. C. McDonald, R. C.

Dempsey, Harry M. Johnson, Lawson Harris,

R. F. Miller, L. D. Payne, George Tyler, James

B. Pfeifer, C. M. Measel and Jack Wilson, who

are empanelled and sworn as a trial Jury in this

case, and after hearing the testimony of the wit

nesses, the instructions of the Court, and the

argument of Counsel, the Jury doth retire to

consider arriving at a verdict, and after delibera

tion thereon doth return into open Court with

the following verdicts, “ We, the Jury, find the

22

defendant, Sylvia Dokes, guilty of Contributory

Delinquency, as charged, and fix her punishment

at a fine of Two Hundred Dollars. C. M. Measel,

Foreman.” “ We, the Jury, find the defendant,

John Henry Dokes, guilty of Contributory De

linquency, as charged, and fix his punishment at

a fine of Two Hundred Dollars. C. M. Measel,

Foreman.” Whereupon the Court doth discharge

the Jury from these cases and each defendant is

given fifteen days in which to file Motion for

New Trial and bond is set at Two Hundred Dol

lars for each defendant.

MOTION FOR NEW TRIAL

Come the defendants by their attorney, Delec

tor Tiller, and move this Court for a new trial,

and for their cause, state: 1

1. The Little Rock City Police gained en

trance into the dwelling house of defendants on

January 30, 1965, in the nighttime around 11:30

p.m., without an arrest warrant, without any

reason to suspect that a felony had been com

mitted, without a search warrant, by either arti

fice, the weight of the influence of their authority

as plain clothes policemen, or by indimidation;

and did then and there commence to search the

entire premises of defendants and to make ar

rests of the 22 persons present without having

seen any one of the 7 adults present give or offer

a single minor a drink of alcoholic beverage or

without having seen a single minor solicit or take

a drink of same,

2. The search was unreasonable and in

violation of the Constitution of Arkansas Ar. 2,

Sec. 15; and in violation of the 4th and 14th

Amendments to the Constitution of the United

States.

3. The arrests were unlawful in that no

felony was charged and no misdemeanor was com

mitted in the presence of the officers. The ar

rests were in violation of Ark. Stats. Annotated

(1947) Sec. 43-403, and in violation of the equal

protection and due process clauses of the Arkan

sas Constitution Art. 2, Sec. 8, and of the equal

protection and due process clauses of the 5th and

14th Amendments to the Constitution of the

United States.

4. The verdict of the jury was contrary to

law in that the instruction to the jury stated in

effect that in order for a minor to be delinquent,

he or she had to be 18 years of age or less. The

evidence and the record show that Janet Kirspel,

a 19 year old white girl, was the only person whose

breath smelled of alcohol and who set a glass of

rum, beer, or whiskey down on the table, as the

officers walked into the house.

5. Because of the nature of the case, cus

tom, usage, long standing mores, and the attend

ant wide spread publicity given to the case, it

23

24

was an abuse of judicial discretion for the trial

judge to deny defendants request to examine the

jurors separately for the purpose of forming a

basis for exercising their 3 peremptory challenges

for cause under the authority of Ark. Stats. An

notated (1947) Sec. 39-226; and this,is especial

ly true since the c a p it a l c it iz e n s c o u n c il , P. 0.

Box 1977, Little Rock, Arkansas, printed, pub

lished, and circulated extensively a “ h a n d b i l l ”

calculated'to prejudice the case against all of the

defendants and to arouse the ire of the s e g r e g a

t io n is t s . It is apparent that the printing, pub

lishing, and circulation was done in this manner

to circumvent Ark. Stats. Annotated (1947) Sec.

45-205. The “ h a n d b i l l ” is attached hereto and

made a part hereof.

1 ■' V - y . , ; rH ,j7 ,J

8. The Court erred in refusing to allow

defendant to show what cases had been dismissed

below.

Wherefore, defendants pray that the verdict

of the jury be set aside and a new trial granted.

s / Delector Tiller

Delector Tiller, Attorney

for defendants

Filed

May, 3, 1966

Roger McNair, Circuit Clerk

By D. L. Shook, D. C.

25

MOTION FOR NEW TRIAL OVERRULED

(Tr.17)

Pulaski Circuit Court — First Division —-

March Term, 1966, Wednesday, May 4, 1966.

; . i ....... / K v l ,

State of, Arkansas

( • "> vu\., •1

64749 & 64750 Contributory Delinquency

Sylvia Dokes (CF)

John Henry Dokes (CM)

This day comes the State of Arkansas by

Philip Ragsdale, Assistant Prosecuting Attorney,

and comes the defendants in proper persons and

by their attorney, Delector Tiller, and motion for

new trial having previously been filed hearing is

had and the Court doth overrule said motion and

defendants exceptions were saved and an appeal

is prayed and defendants are given forty five days

(45) in which to file Bill of Exceptions, and

allowed to remain on same bond pending appeal.

26

ARGUMENT

I

Appellants are denied, due process of law as

guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States be

cause there is no evidence in the record to

support their convictions.

Appellants were convicted of contributory

delinquency under a statute which defined that

term as encouraging, aiding or contributing by

some act to any of more than fifteen kinds of

behavior on the part of a child under eighteen

years of age1. The particular charge against

appellants, although never clearly expressed by

the State, is apparently that they were resopnsible

for the alleged violation of Arkansas liquor laws

1 Under the version of Ark. Stat. Annot. §45-204 which

formed the basis for the judge’s charge, a child is delinquent

if he: (1) violates state law; (2) is incorrigible; (3) knowingly

associates with thieves; (4) knowingly associates with vicious

or immoral persons; (5) without cause or parental consent

absents himself from his home; (6) is growing up in idleness

or crime; (7) knowingly frequents a house of ill-repute; (8)

knowingly frequents any policy shop; (9) knowingly frequents

any place where any gaming device is operated; (10) patronizes,

visits or frequents any saloon or dram shop where intoxicating

liuqors are sold; (11) patronizes or visits any public pool room

where the game of pool or billiards is carried on for pay or

hire; (12) wanders about the streets in the nighttime without

being on any lawful business or occupation; (13) habitually

wanders about any railroad yards or tracks; (14) jumps or

attempts to jump on any moving train; (15) enters any car or

engine without lawful authority; (16) smokes cigarettes about

any public place or schoolhouse; (17) is guilty of indecent, im

moral or lascivious conduct.

27

by certain minors. The evidence presented on

behalf of the State was designed to show that on

the evening of January 30, 1965, there were sev

eral minors within a group of 22 persons in ap

pellants’ home. At the same time, there were

also cans of beer and at least one mixed whiskey

drink in the apartment.

The record is barren, however, of any evi

dence showing or tending to show a violation of

the Arkansas Alcoholic Beverage Control Act by

any minor present at that time, to which appel

lants might have contributed.

Officer Harris testified on behalf of the

State that he had not seen any minor take a drink

of beer or whiskey; nor had he seen either of the

appellants give beer or whiskey to any minor;

nor had he seen appellants drinking. Further,

Harris heard no cursing or obscenity; no one in

the apartment was loud or rowdy. Officer Terry

stated that he did not see anyone in the apart

ment take a drink; nor did he see defendants

give any drinks to any minors. Officer Parsley

also testified that he did not see the defendants

give any minor any liquor, and made no reference

in his testimony to seeing anyone, minor or adult,

drinking.

There is no evidence in the record that any

minor possessed any intoxicating beverage, with

the exception of Miss Janet Kirspel, who it was

28

contended was holding a glass containing ice and

liquor. The same police officer who testified

that he saw Miss Kirspel holding the glass also

testified, however, that she was nineteen years

of age at that time. The statutes relating to the

crime of contributory delinquency in Arkansas

speak to acts committed by minors under the age

of eighteen. Thus, even if the jury believed the

police officers’ testimony regarding Miss Kirspel,

they could not consider this as evidence related to

the charges against appellants.

Furthermore, the officers’ testimony re

garding the beer in the apartment is inconclusive,

since the State failed to establish that it was of

a type within the coverage of the Arkansas Bev

erage Control Act. §48-107, Ark. Stat. Annot.

which provides:

. . . Beer containing not more than

five (5 % ) per centum of alcohol by weight

and all other malt beverages containing

not more than five (5 % ) per centum of

alcohol by weight are not defined as malt

liquors, and are excepted from each and

every provision of this Act.

The State did, however, elicit the testimony

that the beer in the cans was Schlitz beer (T.

45). This Court may take judicial notice of the

fact that Schlitz beer does not contain 5% alco

hol by weight.

29

There is thus not a scintilla of evidence in

the record to affirmatively connect any minor who

could have been “ delinquent” under Arkansas

law with any liquor subject to the penal provi

sions of Arkansas’ Beverage Control Act, except

evidence to the effect that such minors were

present, together with many adults, in an apart

ment in which a glass containing intoxicating

liquors was found in the hands of someone above

the age limit of the Arkansas delinquent child

statute. To equate this situation with “ posses

sion” of the liquor by minors subject to the act,

or with their drinking it, would be to deny ap

pellants due process of law as much as “ convic

tion upon a charge not made would be sheer

denial of due process,” DeJonge V. Oregon, 299

U.S. 353, 362 (1937).

There is not a scintilla of evidence in the

record to affirmatively connect any violation of

any law by any minor with appellants, except

evidence that there were minors in appellants’

apartment. It would be an unwarranted inter

ference with appellants’ freedom of association

to allow this single fact to sustain a conviction

on charges that appellants contributed to unlaw

ful activity by children. The minors had not

been invited to a party; to the contrary, the

record shows that appellants did not even invite

them to hear the rehearsal, but that the minors

came at the invitation of others. Furthermore,

30

John Dokes’ testimony, which was not rebutted,

established that neither he nor his wife brought

the whiskey into their apartment, but that it was

carried by a white adult guest. This statement

is supported by the testimony of one of the police

officers that a bottle of rum was purchased that

evening by the very white person who had first

drawn the officer’s attention to the liquor store

across the street from the housing project.

Thus, appellants’ convictions for contributory

delinquency based on some theory that they sup

plied liquor to minors under the age of eighteen,

are completely without evidentiary foundation

and must be reversed. Shuttlesworth y. Birm

ingham, 382 U.S. 87 (1965); Barr v. City of

Columbia, 378 U.S. 146 (1964); Fields v. Fair-

field, 375 U.S. 248 (1963); Taylor y. Louisiana,

370 U.S. 154 (1962); Garner v. Louisiana, 368

U.S. 157 (1961); Thompson v. City of Louisville,

362 U.S. 199 (1960).

II

The statute under ivhich appellants were con

victed is so vague and uncertain as to violate

the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

Assuming arguendo that the former version

of Ark. Stat. Annot. §45-239, under which appel-

31

lants were tried and convicted, may be given a

narrow and restricted interpretation in order to

save its constitutionality, these prosecutions must

fail because of the complete lack of evidence to

support the judgments of conviction (see I

supra). There is, however, no constitutional

reading of this statute (and its companion pro

vision, §45-204) which would bring appellants’

conduct within its scope.

It is fundamental that in order to comply

with the minimum requirements of due process,

state criminal statutes must provide fair notice

of the acts which they encompass, and definite

criteria to be applied by the determiner of guilt:

. . . No one may be required at peril of

life, liberty or property to speculate as to

the_ meaning of penal statutes. All are

entitled to be informed as to what the state

commands or forbids . . .

Lametta v. New Jersey, 306 U.S.

451, 453 (1938); see also

Winters v. New York, 333 U.S.

507, 515-16 (1948).

The statutes under which appellants were

convicted fail to meet these minimum standards.

First of all, they fail to delineate with any clarity

the acts which are made subject to punishment.

§45-239 refers to any act which causes, encour

ages or contributes to the delinquency of any

child. While the same statute refers by impli

32

cation to §45-204 to furnish the meaning of the

words “ delinquent child,” no such guidance ap

pears regarding “ cause, encourage or contribute

to.” The exact relationship between the adult’s

act and the child’s delinquency which will suffice

for conviction is never intimated. It is left to

the unfettered discretion of the trier to determine

the scope and meaning of the law. There do not

seem to be any Arkansas decisions limiting this

discretion in any manner, but even if there are,

the trial judge failed to impart whatever guid

ance they might provide the jury. The statutes

were given verbatim as instructions without defi

nition or explanation.

§45-204, which attempts to define “ delin

quent child,” is broader and more uncertain, if

anything. Referring to more than fifteen kinds

of behavior which render a child delinquent (see

fotnote 1 supra), it fails to make the adult’s re

sponsibility under §45-239 any clearer. It pen

alizes children for being “ incorrigible,” (with

out elucidation of that term’s meaning). This

in itself would appear to be a plainly prohibited

attempt to make criminal a “ status,” see Robin

son v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1926). A child

who is guilty of “ immoral” conduct is likewise

a delinquent, but no particular canons of morality

are ordained by the statutes. Taken together,

the statutes fail to indicate whether the adult

offender must have knowledge of the child’s be

33

havior, or that some act of his has contributed to

that behavior.

The State legislature, apparently conscious

of the infirmities of these provisions, amended

them by act approved March 20, 1965. The

present versions are somewhat more definite in

their scope and application and do provide guid

ance for a jury by requiring the indictment or

information to state the specific act the defendant

is charged to have committed (see footnote 2

post).

The defect in these statutes is apparent in

their use in this case to penalize the parties for

the exercise of constitutional rights of association

and privacy. The statutes are capable of being

used and were here used by state officials to pro

mote racial segregation; it is apparent on the

record that the real reason for the arrest of ap

pellants was the interracial gathering in their

apartment (T .35-36). This “ sweeping and im

proper application” of the statute, NAACP v.

Button, 371 U.S. 415, 433 (1963), its “harsh

and discriminatory enforcement by local prosecut

ing officials, against particular groups deemed

to merit their displeasure . . . ,” Thornhill v. Ala

bama, 310 U.S. 88, 97-98 (1940), is clearly be

yond the bounds of due process.

34

ill

The admission of testimony regarding observa

tions by police officers inside a home entered

without warrant or probable cause violated

the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments to

the Constitution of the United States.

The Fourth Amendment’s restrictions upon

search and seizure apply through the due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to state and

local law enforcement officers. Mapp v. Ohio,

367 U.S. 643 (1961). Their conduct is required

to satisfy the same standards as were developed

in federal criminal cases interpreting the Fourth

Amendment. Ker v. California, 374 U.S. 23

(1963).

The Constitution requires that government

officials obtain a search warrant before entering

and inspecting private property in all but a

limited number of situations. Weeks V. United

States, 232 U.S. 383 (1914). (The State con

cedes that the Little Rock policemen had no

search warrant at the time they entered the

Dokes’ apartment). There are but three classes

of exceptions to the requirement of a warrant:

searches of moving vehicles upon probable cause,

e.g. Carroll v. United States, 267 U.S. 132

(1925); searches justified by the necessity of an

35

emergency, such as the threatened destruction

of evidence, Johnson v. United States, 333 U.S.

10, 15 (1948) (d ictum ); or searches incident to

a lawful arrest, e.g., United States v. Rabinowitz,

339 U.S. 56 (1950). Only the third category

may be fairly said to have a possible application

to this case. There was no emergency making

impracticable the procurement of a search war

rant, no threat of destruction of evidence, as

shown by Officer Harris’ delay (while his fellow

officers arrived at the project) in proceeding to

the Dokes’ apartment.

However, the arrests made by the police of

ficers were in no way lawful arrests. The testi

mony of Officer Parsley shows that they had no

arrest warrant. No crime was committed in

their presence which would justify a warrantless

arrest; nor did they have reason to suspect that

they would apprehend a felon in Dokes’ apart

ment. Much of what they saw took place prior

to the arrest. The State apparently seeks to

justify the arrest on the basis of what the police

allegedly saw once within the apartment. This

it plainly may not do.

In Johnson V. United States, 333 U.S. 10

(1948), a Seattle police detective, accompanied

by federal narcotics agents, smelled burning

opium and knocked at the door of a hotel room

from which the odor emanated. At the same

36

time, the men announced themselves as police

officers. The door was opened, the only occu

pant in the room was placed under arrest, and a

search was made which turned up incriminating

opium and smoking apparatus which was still

warm, apparently from recent use. The district

court refused to suppress the evidence, the defend

ant was convicted and the conviction affirmed by

the Circuit Court of Appeals. The Supreme

Court reversed (333 U.S. at 15-17).

The Government contends, however,

that this search without warrant must be

held valid because incident to an arrest.

This alleged ground of validity requires

examination of the facts to determine

whether the arrest itself was lawful.

Since it was without a warrant, it could

be valid only if for a crime committed in

the presence of the arresting officer or for

a felony of which he had reasonable cause

to believe defendant guilty.

The Government, in effect, concedes

that the arresting officer did not have

probable cause to arrest petitioner until he

had entered her room and found her to be

the sole occupant. . . Thus the Government

quite properly stakes the right to arrest,

not on the informer’s tip and the smell the

officers recognized before entry, but on the

knowledge that she was alone in the room,

gained only after, and wholly by reason of,

their entry of her home. It was therefore

their observations inside of her quarters,

after they had obtained admission under

37

color of their police authority, on which

they made the arrest.

Thus the Government is obliged to

justify the arrest by the search and at the

same time to justify the search by the ar

rest. This will not do. An officer gain

ing access to private living quarters under

color of his office and of the law which he

personifies must then have some valid basis

in law for the intrusion. Any other rule

would undermine “ the right of the people

to be secure in their persons, houses, papers

and effects,” and would obliterate one of

the most fundamental distinctions between

our form of government, where officers

are under the law, and the police-state

where they are the law.

Nor may the search be justified by the con

flicting testimony concerning Mrs. Dokes’ al

leged consent. As one officer stated “ we stopped

them and took them back to the apartment” (T.

40). Even when there is conflicting testimony,

consent to enter a home is not easily found. In

the Johnson case (333 U.S. at 13) the Court

found:

Entry to defendant’s living quarters,

which was the beginning of the search,

was demanded under color of office. It

was granted in submission to authority

rather than as an understanding and in

tentional waiver of a constitutional right.

Cf. Amos V. United States, 255 U.S. 313.

38

The Court’s words are equally applicable to this

case. When no emergency circumstances exist

to justify a search without a warrant and regu

lar processes are available to obtain search war

rants, the courts should not readily sanction an

alternative method of search. This is especial

ly true when the alternative method so easily

lends itself to abuse through both the deliberate

action of the police and the fear of individuals in

the face of authority. For these reasons the

presumption has always been that consent is

coerced unless proven otherwise by the police.

Judd v. United States, 190 F. 2d 649 (D.C. Cir.

1951); United States V. Roberts, 223 F. Supp. 49,

58 (E.D. Ark. 1963).

The Johnson case is controlling. Clearly,

appellants’ Motion to Suppress the evidence ob

tained by the police officers should have been

granted. The denial of the motion taints the

convictions with evidence obtained in violation of

the Constitution and requires their reversal. The

evidence obtained by the illegal entry in this case

was the only evidence introduced by the State and

thus obviously the conviction must fall.

39

IV

The convictions for contributing to the delin

quency of a minor violate the due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States because no

alleged delinquent minor was ever identi

fied.

Appellants were charged with the crime of

contributory delinquency, which was defined by

the trial court as causing, encouraging or con

tributing to the delinquency of a child. The con

ditions under which a child was to be considered

delinquent were also stated by the trial court in

instruction No. 2. A verdict of guilty was re

turned by the jury against both defendants.

The trial and the subsequent verdicts were

defective in that the State never established at

any stage the minor or minors who were alleged

to have become delinquent as a result of appel

lants’ actions. Appellants were never informed

and the jury was never instructed as to the minor

or minors whose conduct it should consider in de

termining the guilt of appellants. Although

there was testimony in the record that several

minors were present in appellants’ apartment on

the evening of January 30, 1965, there was no

evidence (a) that any particular minor was de

linquent, (b) that appellants were charged with

40

having contributed to the delinquency of any

specific minor, or (c) that the actions of the ap

pellants were responsible for the alleged delin

quency of any minor.

The jury cannot be permitted to draw what

ever inferences it desires regarding an essential

element of a crime. There must be some evidence

to prove every element of that crime Thompson

V. City of Louisville, 362 U.S. 199 (1960).

In Barr V. Columbia, 378 U.S. 146 (1964) ,

defendants were convicted in the courts of South

Carolina on charges of breach of the peace and

trespass. The record established that the Negro

defendants had entered a department store and

sat down at the lunch counter. They were told

by the store manager that he would not serve

them, and he asked them to leave. They re

mained quietly seated at the counter and were

arrested. There was no evidence that they be

came violent or disorderly. The Supreme Court

reversed:

Turning to the merits, the only evi

dence to which the city refers to justify the

breach-of-peace convictions here, and the

only possibly relevant evidence which we

have been able to find in the record, is a

suggestion that petitioners’ mere presence

seated at the counter might possibly have

tended to move onlookers to commit acts

of violence. . . . Accordingly, we are un-

41

willing to assume and find it hard to be

lieve that the State Supreme Court if it

had passed on the point would have held

that petitioners could be punished for tres

pass and for breach of the peace as well,

based on the single fact that they had re

mained after they had been ordered to

leave.. . . Since there was no evidence

to support the breach-of-peace convictions,

they should not stand. Thompson V. City

of Louisville. . . . (378 U.S. at 150-51.)

In the instant case, there is no suggestion

that the minors in appellants’ home on January

30, 1965, were made delinquent by appellants’

actions. To sustain the convictions under these

circumstances would be equivalent to making the

mere presence on one occasion of a minor under

eighteen years of age in a home in which there is

also liquor, conclusive evidence of contributory

delinquency on the part of the homeowner. The

evidence here shows only that Mr. and Mrs. Dokes

tolerated the presence of a number of adults and

minors in their apartment. No noise, rowdyism

or discourtesy of any kind was found by the of

ficers. The appellants did not even offer liquor

to their guests who, the record shows, brought

their own.

42

V

Appellants have been denied due process of law

as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United

States because they were convicted upon an

information and charge to the jury drawn

from statutes rendered inapplicable by

amendment prior to their trial.

At appellants’ trial in the Circuit Court of

Pulaski County on April 8, 1986, the judge in

structed the jury, over the objections of the de

fense, in accordance with the State’s requested

instructions numbers 1 and 2:

[No. 1] Any person who shall, by an

act, cause, encourage or contribute to the

dependency or delinquency of a child, as

these terms with reference to children are

defined by this act, or who shall, for any

cause, be responsible therefor, shall be

guilty of a misdemeanor and may be tried

by any court in this State having jurisdic

tion to try and determine misdemeanors

and, upon conviction therefor, shall be

fined in a sum not to exceed five hundred

dollars ($500.00), or imprisonment in

the county jail for a period not exceeding

one (1 ) year, or by both such fine and im

prisonment. When the charge against

43

any person under this act concerns the de

pendency of a child or children, the offense,

for convenience, may be termed contribu

tory delinquency. Provided, however,

that the court may suspend any sentence,

stay or postpone the enforcement of execu

tion or release from custody any person

found guilty in any case under this act

when, in the judgment of the court, such

suspension or postponement may be for the

welfare of any dependent, neglected or de

linquent child as these terms are defined

by this act, such suspension or postpone

ment to be- entirely under the control of the

court as to conditions and limitations.

[No. 2] T h e words “ delinquent

child” shall mean any child, whether mar

ried or single, who, while under the age of

eighteen (18) years, violates a law of this

State; or is incorrigible or knowingly as

sociates with thieves, vicious or immoral

persons; or without just cause and with

out the consent of its parents, guardian or

custodian absents itself from its home or

place of abode, or is growing up in idleness

or crime; or knowingly frequently visits a

house of ill-repute; or knowingly frequent

ly visits any policy shop or place where any

gaming device is operated; or patronizes,

visits or frequents any saloon or dram shop

44

where intoxicating liquors are sold; or

patronizes or visits any public pool room

where the game of pool or billiards is being

carried on for pay or hire; or who wanders

about the streets in the nighttime without

being on any lawful business or lawful oc

cupation; or habitually wanders about any

railroad yards or tracks or jumps or at-

temps to jump on any moving train, or

enters any car or engine without lawful

authority, or writes or uses vile, obscene,

vulgar, profane or indecent language or

smokes cigarettes about any public place or

about any schoolhouse, or is guilty of in

decent, immoral or lascivious conduct; any

child committing any of these acts shall be

deemed a delinquent child.

(T. pp. 73-76)

The State’s requested instructions were taken

verbatim from former Ark. Stat. Annot. §§45-

239 and 45-204, respectively. However, after

the filing of charges against appellants but well

before trial, the applicable statutes had been sub

45

stantially revised by the Legislature (Acts 1965,

No. 418, approved March 20, 1965).2

2 The statutes now read as follows:

§45-239. Persons contributing to delinquency. Any

person who shall cause, aid, or encourage any person under

eighteen (18) years of age to do or perform any act which if

done or performed would make such person under eighteen

(18) years of age a “delinquent child” as that term is defined

herein, shall be quilty of a misdemeanor. Provided that when

any person is charged by indictment or information with a

violation of this Act, such indictment or information shall state

the specific act with which the defendant is charged to have

committed in violation of this Act. Any person convicted

of a violation of this section shall be punished by imprison

ment for not less than sixty (60) days nor more than one (1)

year, and by a fine of not less than one hundred dollars

($100.00) nor more than five hundred dollars ($500.00). Pro

vided, the court may suspend or postpone enforcement of all

or any part of the sentence or fine levied under this section if

in the judgment of the court such suspension or postponement

is in the best interest of any dependent, neglected or delinquent

child as these terms are defined in this act.

§45-204. Delinquent child. The term “delinquent child”

shall mean and include any person under eighteen (18) years

of age:

(a) Who does any act which, if done by a person eighteen

(18) years of age or older, would render such person subject

to prosecution for a felony or a misdemeanor;

(b) Who has deserted his or her home without good or

sufficient cause or who habitually absents himself or herself

from his or her home without the consent of his or her parent,

step-parent, foster parent, guardian, or other lawful custodian;

(c) Who, being required by law to attend school, habitually

absents himself or herself therefrom; or

(d) Who is habitually disobedient to the reasonable and

lawful commands of his or her parent, step-parent, foster

parent, guardian or other lawful custodian.

Any reputable person may initiate proceedings against a

person under eighteen (18) years of age under this Act by

filing a petition therefor with the juvenile court. All such

proceedings shall be on behalf of the State and in the interest

of the child and the State and due regard shall be given to

the rights and duties of parents and others, and any person

so proceeded against shall be dealt with, protected or cared for

by the county court as a ward of the State in the manner

hereinafter provided.

46

Appellants have a right to a trial which ac

cords in every way with the laws of the State of

Arkansas. This right is denied when repealed

statutes determine the standards of guilt in a

criminal prosecution. Statutory revision is an

expression of legislative dissatisfaction with the

prior rule and makes mandatory the operation of

the new rule in all pending cases. The trial

court is not permitted to choose between statutes

when one has been repealed for it is the duty of

courts to apply the existing law to current cases,

and to take cognizance of changes in the law,

whether such changes are the result of judicial or

legislative action.

Clear statute law requires no less. Ark.

Stat. Annot. §1-104 provides:

No action, plea, prosecution or pro

ceeding, civil or criminal, pending at the

time any statutory provision shall be re

pealed, shall be affected by such repeal, but

the same shall proceed in all respects as if

such statutory provision had not been re

pealed, (except that all proceedings had

after the taking effect of the revised stat

utes, shall be conducted according to the

provisions of such statutes, and shall be, in

all respects, subject to the provisions there

47

of, so far as they are applicable.3 (em

phasis supplied).

Even had the statutes been amended after

the entry of judgment in this action, it would

be the duty of this Court to reverse and remand

the cause for a new trial. In American law,

as Mr. Chief Justice Marshall observed long ago,

It is in the general true that the

province of an appellate court is only to

enquire whether a judgment when ren

dered was erroneous or not. But if sub

sequent to the judgment and before the

decision of the appellate court, a law inter

venes and positively changes the rule which

governs, the law must be obeyed, or its

obligation denied. If the law be consti

tutional . . . I know of no court which can

contest its obligation . . . In such a case the

court must decide according to existing

laws, and if it be necessary to set aside a

judgment, rightful when rendered, but

which cannot be affirmed but in violation

of law, the judgment must be set aside.

( United States v. Schooner

Peggy, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch)

103, 110 (1 8 0 1 ));

3 There is no inconsistency between §§1-104 and 1-103 (set

forth below), since the latter section is operative only upon

statutes which have been completely repealed rather than

revised.

[§1-1031 When any criminal or penal statute shall be

repealed, all offenses committed or forfeitures accrued

under it while it was in force shall be punished or en

forced as if it were in force, and notwithstanding such

repeal, unless otherwise expressly provided in the repealing

statute.

48

See also Durnii v. -J. E. Dunn Constr. Co., 186

F. 2d 27, 29 (8th Cir. 1951). As the Court of

Appeals for the Fourth Circuit put it in a recent

case: “ until a case has been finally adjudicated

on direct appeal it is controlled by the most recent

statutory and decisional law.” Smith V. Hamp

ton Training School, 360 F. 2d 577, 580 (1966).

Appellants were entitled to a trial based on

existing law. By its failure to apply existing

law instead of a repealed statute the trial court

committed error and the judgment below should

be reversed.

VI

Appellants have been denied their rights under the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States because their arrest and

conviction was motivated by racial consid

erations.

Police officer Harris, who was responsible

for the investigation and arrest of appellants,

testified frankly that it was the fact that whites

were entering a segregated Negro housing proj

ect which motivated his interest. He would

have done little or nothing if what he had seen

was merely several cars filled with Negroes driv

ing onto the grounds of the project (T .35-36).

49

The State is not permitted to accord dif

ferent treatment to citizens of different races,

cf. Hamilton v. Alabama, 876 U.S. 650 (1964),

discussed in Bell v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 226, 248

f.n. 4 (1964) (Douglas, J. concurring). The

Fourteenth Amendment restricts state officers

or instrumentalities from using their official

powers to coerce adherence to segregated customs

or practices. Lombard V. Louisiana,, 373 U.S.

267 (1963). Appellants’ rights to the privacy

of their home and their right to associate with

others of their own choosing, are likewise guar

anteed them by the Fourteenth Amendment.

Griswold V. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965).

Appellants’ convictions must, therefore, be

reversed, since it is clear that the sole purpose of

their arrest and prosecution was to discourage

interracial gatherings of any sort, and to deny

them the freedom of their home.

50

CONCLUSION

Wherefore, for all the foregoing reasons,

appellants respectfully submit that the judg

ments of the trial court should be reversed and

dismissed.

Respectfully submitted,

D e l e c t o r T il l e r

2305 Ringo Street

Little Rock, Arkansas

J o h n W . W a l k e r

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas

J a c k G r e e n b e r g

J a m e s M . N a b r it III

M ic h a e l M e l t s n e r

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Attorneys for Appellants