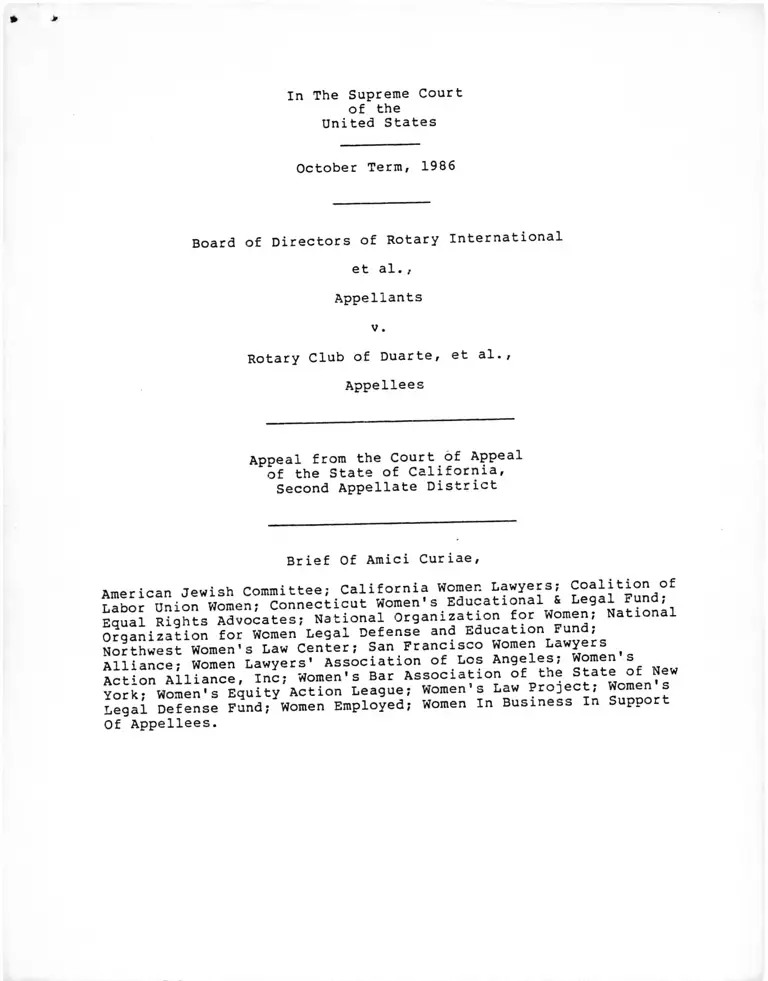

Board of Directors of Rotary International v Rotary Club of Duarte Brief of Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1986

53 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Board of Directors of Rotary International v Rotary Club of Duarte Brief of Amici Curiae, 1986. e0c54155-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0ec5cd45-cc06-4fc2-8f00-a023d7b01261/board-of-directors-of-rotary-international-v-rotary-club-of-duarte-brief-of-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In The Supreme Court

of the

United States

October Term, 1986

Board of Directors of Rotary International

et al.,

Appellants

v .

Rotary Club of Duarte, et al.,

Appellees

Appeal from the Court of Appeal

of the State of California,

Second Appellate District

Brief Of Amici Curiae,

American Jewish Committee; California Women Lawyers; Coalition of

Labor Union Women; Connecticut Women• s _Educational & Legal E^nd,

Equal Rights Advocates; National Organization for Women, National

Organization for Women Legal Defense and Education Fund;

Northwest Women’s Law Center; San Francisco Women Lawyers

Alliance; Women Lawyers’ Association of Los Angeles; Women s

Action Alliance, Inc; Women’s Bar Association of the State of New

York* Women's Equity Action League; Women’s Law Project; Women

Legal Defense Fund; Women Employed; Women In Business In Support

Of Appellees.

I .

STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF

AMICI CURIAE

Amici are national and state organizations, open to women and

men, committed to achieving equal opportunity for women and

minorities in the business, professional and civic life of our

country. Amici's individual statements of interest appear in

Appendix A. Amici's members are personally aware of the high

level of business activity at many of the country's purportedly

"private" clubs and organizatiions, such as Rotary International,

and of the lost business opportunities to themselves and to

others when', and minorities are barred from membership at these

business oriented clubs. Because of its direct impact on women s

and minorities' full access to clubs and organizations which are

centers of business and decision making activity, amici have clo

sely followed the progress of the case at bar and are __________

concurrent with its outcome.

II.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Amici adopt the Statement of the Case set forth by

Appellee, Rotary Club of Duarte.

-2-

III.SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

[LYNN]

IV.

ARGUMENT

A. Introduction

In recent years, the impact on women and minorities of

exclusion from clubs and organizations that hold themselves out

as private, but are in fact centers of business activity has

received wide attention.-/ Such exclusion deprives women of

equal economic opportunity, subjects women to personal hum^iation

and, by barring women from informal centers of power, confirms in

men the belief that women are inappropriate participants where

formal power is exercised. An understanding that such exclusion

is neither unimportant nor benign and that there is indeed exten

sive business activity at so-called "private" clubs and organiza

tions is implicit in the resolutions, executive orders and

personnel policies recently promulgated by numerous organiza-

*Although in many cases the focus of this brief is the impact

of exclusion from business oriented facilities, on women, amci

are equally committed to ensuring that minority groups enjoy full

acass to those important business centers.

1/ See, e.g., Burns The Exclusion of Women from Influential

Mon’c' rinhq- The Inner Sanctum and the Myth of Full Equalityr 18

S;;,.S £p-ST% o T Srhafran. L.H., WELCOME TO THE C L U B / (No

Women Need Apply), Women and Foundations/Corporate Philanthropy,

The All-Male Club: Threatened On All Sides, Business

Week August 11. 1Qfln, qn? Bracewell. Sanctuaries of Power*

HoustoS C U y Magazine; May 1980, at 50; Behind Closed Doors:

Discrimination by Private Clubs: A ^report Based on City

Commission on Human Rights Hearings New York City Commission on

Hvmia" n <>751 ■ Ginsburg. Women as Full Members of the Club

An Evolving American Ideal, 6 Hum. Rts. 1 (1975).

-3-

tions, government officials, corporations and academic institutions

barring the conduct of official business at discriminatory clubs

and other facilities. For example, the American Bar Association,

the State Bar of California and New York, the National

Association of Women Judges, the Association of the Bar of the

City of New York, the Bar Association of San Francisco, New York

County Lawyer's Association, the New York State Bar Association,

American Jewish Congress, and the Council on Foundations prohibit

their committees, sections and staffs from holding meetings and

2/other official functions at clubs that discriminate.— Mayor

Edward I. Koch and Governor Mario Cuomo have issued Executive

Orders barring the conduct of official New York City and New York

3 /State business at such facilities.— The New York Court of

Appeals amended the Rules of The Chief Judge to include a similar

4/prohibition for the Unified Court System.—

Among corporations, ARCO, Michigan Consolidated Gas

Company, CBS, IBM, The New York Times and Bank of America no

2/ "The Use of Private Clubs for Association Functions,"

American Bar Association, adopted October 1978; "Policy on Situs of

Association Council Meetings and Situs of Meetings of Association

Officers and Stafaf", The Association of the Bar of the City of New

York, adopted April 9, 1981; Resolution of the New York County Bar

Association respecting use of discriminatory clubs adopted April 14,

1986; New York State Bar Association, Resolution adopted January 23,

1981; "Discrimination at Private Clubs, Hotels, etc.", American

Jewish Congress, adopted June 6, 1982; "Council Policy on the Use of

Private Clubs", Council on Foundations, adopted October 19, 1981.

3/ Executive Order No. 69. Mayor Edward I. Koch,

September 28, 1983; "Prohibition of the Conduct of City Business at

Private Clubs That Engage in Discriminatory Membership Practices";

Executive Order No. 17, Governor Mario M. Cuomo, May 31, 1983,

"Establishing State Policy on Private Institutions Which

Discriminate".

£/ Rules of the Chief Judge, 22 NYCRR 20.21, adopted

November 24, 1980.

-4-

V. . 5/

* • s ' ' " \ -

longer pay for their efforts to be membets of such clubs or reim-

burse business expenses incurred there.—

Columbia University and the University of Minnesota are among

academic institutions which expressly bar the conduct of univer-

6 /sity business or activities at discriminatory facilities.—

Many of the clubs that have been the targets of these

actions have responded to these external pressures and to the

urgings of their own members by opening their doors to women. In

1986 alone the University Clubs of Pasadena, California and

Providence, Rhode Island, Philadelphia's Union League and the

7 /Detroit Athletic Club were among those voting to admit women.—

The Duarte Rotary Club, too, seeks to acknowledge the

reality of its club's purposes and practices by admitting women

who meet Rotary's membership criteria as business and pro

fessional however, resists this change, pretending that it is

5/ Memorandum from Lowdrick M. Cook, Chairman and Chief

Executive Officer of ARCO to ARCO senior management, May 28, 1986; 2

Utilities Halt Dues for Detroit Men's Club, New York Times,

February 12, 1986 at 10, Col 5; CBS Policy, Delegations of

Authority, Reimbursable Business Expenses, Paragraph 16, Adopted

January 31, 1981; IBM "Position of Non-Support for Organizations or

Service Clubs Which Exclude Persons on the Basis of Race, Color,

Sex, Religion or Natural Origin," Adopted 1980; Century Club's

Timesmen S^uck With the Tab, New York Post, December 12, 1983, at 6,

col.l; Bank of America 1980 Expense Account Guidelines.

6/ "Resolution Concerning University Participation in Clubs

with Discriminatory Admissions Policies", Columbia University

adopted January 23, 1981; Memorandum of President C. Peter

McGrath, June 1984, University of Minnesota.

7/ All Male Club of 60 Years Finally Relents, Los Angeles

Times, June 19, 1986 at 1; Club in Rhode Island to let Women Join,

New York Times, June 8, 1986 at 61, col. 1; Philadelphia Club Drops

All-Male Restriction, New York Times, May 22, 1986 at A.20; Clubs

End Bar to Women, New York Times, December 31, 1986 at D16, col.2.

-5-

solely an organization of intimates providing service to the

public, that it has no business purpose, provides no business

related goods or services, and confers no economic advantage on

its members. Rotary's Manual of Procedure and the affidavits

offered in this and other Rotary cases tell a different story —

the story of an immense international organization avid for

publicity and growth, whose members are chosen strictly for their

standing in the business community and are provided with both the

training andd access to an array of local, national and worldwide

business leaders to enhance that standing in the business com

munity.

Despite Rotary's protestations, the business advantage con

ferred by membership in the organization is undeniable, and the cost

to business and professional women excluded from its ranks severe.

The substantial business activities engaged in by Rotary make appli

cation of the Unruh Civil Rights Act to Rotary a constitutionally

valid effort on the part of California to remove discriminatory

barriers to women's full participation in the business, pro

fessional, civic and political life of the community.

B. The Application Of The Unruh Act To Rotary

International Narrowly Serves The "Profoundly

Important" State Interest Of Ensuring Nondis-

criminatory Access To Commercial Opportunities.

This case requires the court, as it did in Roberts v.

United States Jaycees, 468 U.S. 609, _____ (1984) to "address a

conflict between a State's efforts to eliminate gender-based

discrimination against its citizens and the constitutional

freedom of association asserted by members of a private

organization." California has long sought to eliminate

-6-

discrimination against its citizens on the basis of "sex, race,

color, religion, ancestry, or national origin" by, inter alia,

enactment of the Unruh Civil Rights Act, California Civil Code

§ 51 ("Unruh Act"). In this case, the right which California

seeks to protect is the access of women to economic opportunity.

This court faced a similar effort by the State of Minnesota to

protect women's access to economic advantage in Roberts, supra,

in which this court noted:

"Like many States and municipalities,

Minnesota has adopted a functional definition

of public accommodations that reaches various

forms of public, quasi-commercial conduct.

This expansive definition reflects a recogni

tion of the changing nature of the American

economy and the importance, both to the indi

vidual and to society, of removing the

barriers to economic advancement and political

and social integration that have historically

plagued certain disadvantaged groups,

including women. . . . Assuring women equal

access to such goods, privileges, and advan

tages clearly furthers compelling state

interests."

Roberts, supra, 468 U.S. at ____, 104 S.Ct. at 3254 (citations

omitted). California, too, seeks to further the compelling state

interest of assuring women and minorities equal access to econo

mic advantages available in private clubs and organizations which

are engaged in substantial business activity.

California, has a long history of trying to eliminate

discrimination in all forms of business establishments, public or

private, to ensure its citizens nondiscriminatory access to busi

ness opportunity.

-7-

1 . The Unruh Act Was Enacted To Permit California's

Citizens Nondiscriminatory Acces to Public

Facilities and Economic Advantages.

Civil Code § 51 currently states in pertinent part:

"All persons within the jurisdiction

of this State are free and equal, and no

matter what their sex, race, color, reli

gion, ancestry, or national origin are

entitled to the full and equal accom

modations, advantages, facilities, privi

leges, or services in all business

establishments of every kind whatsoever."

The Act has been progressively expanded over the years to cover

more entities as it has become clear that the full access of

California's citizens to goods, services and economic advantages

in a nondiscriminatory manner required such expansion.

The California Court of Appeal reviewed the history of

the Unruh Act in Curran v. Mount Diablo Council of Boy Scouts,

147 Cal.App.3d 712, 726-27, 195 Cal.Rptr. 325, 333-34 (1983):

"Under California's early common

law, enterprises which were affected with

a public interest had a duty to provide

sejrvice^ to all without discrimination.

In 1987, statutory recognition was given

to thirs common law doctrine by the enact

ment of the predecessor of the present

Unruh Act. . . . "

"From 1897 until 1959, when Unruh

was enacted, the language of the public

accommodation statute was amended on

several occasions, with the Legislature

listing additional specific |>lac es of

public accommodation but always including

the general category of 'all other places

of public accommodation or amusement.'

Despite the broad language forbidding

discrimination by 'all other places of

public accommodation,' certain decisions

of appellate courts made in the late

1950's reveal a judicial effort to

-8-

'improperly' curtail 'the scope of the

public accommodation provisions' by

narrowly defining the kinds of business

that afforded public accommodation. . . .

"Out of a concern for, and in

response to, these decisions restricting

the scope of the public accommodations

provisions, the Legislature in 1959

enacted the Unruh Act . . . "

(Citations and footnotes omitted.)

The Unruh Act has been applied to forbid discrimina

tion by physicians (Washington v. Blampin, 226 Cal.App.2ds 604,

48 Cal.Rptr. 235 (1964)), real estate brokers (Lee v. O'Hara, 58

Cal.2d 476, 370 P.2d 321, 20 Cal.Rptr. 617 (1962)), a condominium

homeowner's association (O'Connor v. Village Green Owners' Ass'n,

33 Cal.3d 709, 662 P12d 427, 191 Cal.Rptr. 320 (1983)) and a

nonprofit organization providing services to boys only (Curran v.

Mount Diablo, supra.).

2. Discriminatory Membership Policies Have a

Crippling Effect on the Professional

Advancement of Women and Minorities

The Unruh Act protects California citizens from a number

of serious social and economic hardships. In this case, at issue

is harm to women and minorities in being excluded from organiza

tions which foster business opportunities and education for their

members.

It has been well documented that a private club can

afford its membetrs unique opportunities for personal contacts

and business deals. Foundations, major corporations, and presti

gious law firms all recognize that private clubs enable their

employees to spend time with :lients in a relaxed, informal

-9-

setting, establishing credibility on a personal and professional

level, and become part of the "who knows whom" net work so criti

cal to professional success. A study sponsored by the American

Jewish Committee revealed that 50.5% of corporate executives

interviewed believed clubs provided valuable business contacts.

Sixty-seven and nine-tenth's percent (67.9%) reported that the

membership adds to one's status in his firm or community. Burns,

The Exclusion of Women from Influential Men's Clubs; The Inner

Sanctum and The Myth of Full Equality, 18 Harv. C.R.-C.L. L.Rev.

321, 328 n.20 (1983), quoting R. Powell, The Social Milieu as

a Force of Executive Promotion 105 (1969). As the New York City

Commission on Human Rights concluded after holding hearings on

business-oriented private clubs:

"Irrespective of the reasons, major

companies, banks, law firms and

trade professional associations

routinely use club facilities rather

than public accommodations for

meetings of all kinds, informal and

formal. . . [W]itnesses testified

from personal experience that clubs

are the preferred setting for sche

duled group meetings ranging from

the inner circle of a particular

firm, to the leaders of an industry,

profession or governmental agency,

to special events at which prominent

persons address a select audience on

matters of special or general

current interest."

E. Lynton, Behind Closed Doors: Discrimination by Private Clubs,

A Report Based on City Commission on Human Rights Hearing 15

(1975); see also Club Membership Practices of Financial

Institutions: Hearings Before the Senate Committee on Banking,

-10-

Housing, and Urban Affairs, 96th Cong., 1st Sess. (1979).

These clubs enable their members to affiliate with a

network of upwardly mobile peers and gain access to the business

and civic leaders of the community. In essence, they provided

members with an entree to the "Old Boy Network." The Old Boy

Network is that series of linkages with influential elders and

am/bitious peers which men develop as they move through school,

work, professional organizations, and private clubs. It provides

men with knowledgeable allies who help them advance in their

careers, teach them the cast of characters, and alert them to job

openings, business opportunities, and financial grants. The kind

of access Rotary provides is evidenced by an article in a recent

issue of The Rotarian, in which the author begins by describing

the experience of a young man newly inducted into Rotary: "At

first he was awed to be fraternizing and breaking bread with

community leaders who were his senior by many years, but they

encouraged him to call them by their first names.' Uhlig, Do

Women Belong in Rotary? No, 150 The Rotarian No. 1, p. 15

(January 1987).

overestimated. The Detroit Free Press has described the Old Boy

men a chance to push the right buttons and meet the right people

at the right time." O'Brien, Women Helping Women, Det. Free

Press, Nov. 13, 1978. Promotions and high-level jobs are often

based on the personal relationships forged in the old Boy

Network. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that almost one

third of all jobs men hold come through personal contacts. U.S.

The importance of access to such networks cannot be

the power really is...the mechanism that gives

-11-

Bureau of Labor Statistics, Bull. No. 1886, Job Seeking Methods

Used by American Workers, Table 3 1972). Most people believe the

percentage is even higher for hihg-level jobs. C. Kleiman,

Women's Networks 2 (1980).

Women need the access to career^enhancing networks as

much as, if not more than, men. Numerous studies conducted over

the past fifteen years have revealed a convergence in men's and

women's career and family goals. See, e.g . , Johnson, For

Students a Dramatic Shift in "Goals", N.Y. Times, Feb. 28, 1983,

at B5, col. 2; Devanna, Male/Female Careers, The First Decade,

Columbia University Graduate School of Business, Center for

Research in Career Development (1984). In one study of male and

female managers in two unnamed companies, researchers found that

women and men both had high power and achievement drives and

strong motivation to manage. Harlan & Weiss, Moving Up: Women

in Managerial Careers, Final Report, Wellesley College Center for

Research on Women (1981).

Yet women have not attained the same professional status

as their male colleagues. Although women fill nearly one-third

of all management positions, most are stuck in jobs with little

authority and relatively low pay. Hymowitz & Schellhardt, The

Glass Ceiling, Wall St. J., March 24, 1986, at ID, col. 1. Only

two percent of top executives surveyed in 1985 are women. Just

one woman- — Katherine Graham of Washington Post Co. — heads a

Fortune 500 company. Id. col. 2. A recent survey of 1,362 senior

executives in positions just under chief executive rank at the

nation's largest companiies tuurned up only 29 women. Why Women

-12-

<1Executives Stop Before The top, Newsweek, Dec. 29, 1986

January 5, 1987 at 72. Moreover, women hold only three to four

percent of Fortune 1000 directorships, despite their majority

place in the work force. Ansberry, Board Games, Wall St. J.,

March 24, 1985, at 4D, col. 1.

Aspiration and drive simply are not enough for women

seeking to equal the professional accomplishments of their male

counterparts. "[W]ho knows whom...is important [in carrer

advancement]. In this regard, women suffer because men tend to

socialize in activities which exclude women." Bartlette,

Poulton-Callahan, Somers, What's Holding Women Back, Management

Weekly, Nov. 8, 1982; see also Hollingsworth, Sex Discrimination

in Private Clubs, 29 Hastings L.J. 417, 421 (1977) ("The exclu

sion of a segment of the population from such private clubs works

to severely limit the economic mobility of that segment."); and

Bell, Power Networking, Black Enterprise 111 (Feb. 1986) ("[T]o

to be truly successful, you have to become a part of the inter

nal, often invisible, old boy network, too."). Women need the

informal contacts, networking, and professional support mem

bership in private clubs, such as Rotary International, offer.

These clubs often argue that they are not commercial

establishments but instead purelyh social organizations in which

their members should enjoy freedom of association. In fact, most

private clubs serve to promote business activity of every con

ceivable kind. In a recent interview, the Presidsent of the Bar

Assjociatino of San Francisco stated that important legal bus

iness, that is both commercial and professional is transacted at

-13-

private clubs. 'Male' Clubs: Bar Leaders are Members, The

Recorders, July 22, 1986. Phillip Johnson, one of the country's

leading architects, periodically convenes "architectural lumi

naries" for "stag dinners at the Century Association." The Trend

Setting Traditionalism of Architect Robert A. M. Stern, N.Y.

Times Magazine, Jan. 14, 1985, at 41, 47. New York City's

Century Club would have been the site of the American Book Awards

Dinner had not objections to use of a sex-discriminatory facility

caused its relocation to the New York Public Library. Three

Writers Win Book Awards, N.Y. Times, Nov. 16, 1984, at C32, col.

1. The Union League, another New York institution which refuses

membership to women, was the site chosen by the Hyatt Corporation

Chairman for a meeting with Braniff airline creditors to discuss

a takeover proposal. Improved Braniff Aid Plan Reported, N.Y.

Times, April 1983, at 29, col. 1.

Rotary International is no different. It cannot

distinguish itself merely by professing that it performs solely

eleomosynary functions. Volume 1 of the Rotary Basic Library

confirms that the primary purpose behind the formation of the

Rotary movement was commercial advantage. "The earliest meetings

of the 'Rotarians' were held in the name of 'acquaintance' and

good fellowship, and they were designed to produce increased

business for each member." (Rotary Basic Library, Vocational

Service, vol. 3, at 6-7). Even today, as Rotary International

admitted in its Jurisdsictional Statement, 'membership in Rotary

is restricted to business and professinoal men..."

(Jurisdictional Statement at 3.) In the proceedings below, Jacob

Frankel, president of California State College, testified that

-14-

Rotary membership was essential for a college president to raise

funds. All members of his cabinet were encouraged to join Rotary

as part of their jobs. (R.T. 70.)

Besides the access to professional development which

discriminatory business-related clubs deprive women, such discri

minatory clubs have other negataive ramifications as well. They

perpetuate the treatment of women and minorities as second class

citizens. As two women law professors testsified before the

United States Senate:

"The existence of such clubs today is

evidence that there are still many who

think that minorities are not fit persons

with whom to associate. The exclusion

of women from private clubs delivers a

different but no less offensive message.

It, too, is a reminder that the legal,

political, and economic role assigned to

women throughout most of our history was

a quite restricted one."

Barbara Allen Babcok and Herma Hill Kay, Statement Submitted to

the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, June 23,

1979, at 1-2. Such policies also deny women and minorities

opportunities for professional growth and advancement. As the

Presidsent of the San Francisco Bar Association stated when

interviewed about such clubs; "The exclusion of women and minori

ties operates as an impediment to their full participation in the

legal profession." 'Male' Clubs: Bar Leaders are Membes, The

Recorder, July 22, 1984.

A further ramification of the discriminatory policcies,

not to be overlooked, is their effect upon male members. Where

-15-

such exclusionary policies exist, men cannot entertain female or

minority clients. Nor can they invite female colleagues to lunch

or to participate in club activities. Another disadvantage is

the humiliation a member would suffer if he inadvertently invited

a woman or minority to attend a function only to discovery upon

her arrival that she could not attend or must enter through a

side door. Such episodes should not be discounted. Stories of

their occurrence are legion. See, e .g . , Brick, Going Private;

Who is Welcome at the Club?, S.F. Attorney, Feb./March 1984, at

20.

Recognizing these various disadvantages, numerous states

and municipalities recently have enacted legislation designed to

prohibit discriminatory membership practices at private clubs*

Both Detroit and Philadelphia have adopted resolutions that would

bar the city from awarding contracts to any company that pays for

membership or expenses at such clubs. Nazario, Gentlemen of the

Club, Wall St. J., March 24, 1986, at 19D, col. 1. New York City

has amended its definition of a public accommodation to include

any organization that has more than 400 members, regularly serves

meals and regularly receives payments from or on behalf of non

members in furtherance of trade or business. Kolbert, Many Country

Clubs Still Male Bastions, N.Y. Times, July 19, 1986, at 52A,

col. 2.

All of these resolutions folowed extensive hearings on

the policies of private clubs and their discriminatory impact,

The conclusions of the states and cities which reviewed the

matter were unanimous. All embodied "a recognition of the

-16-

changing nat are of the American economy and of the importance,

both to the individual and to society, of removing the barriers

to economic advancement and political and social integration that

have historically plagued certain disadvantaged groups,

including women." Roberts supra, 468 U.S. at 626.

The California legal profession has also recognized the

growing problems that exclusionary membership policies present.

In 1986, both the Bar Association of San Francisco and the

California State Bar Board of Governors adopted resolutions

urging law firms and corporate legal departments to refrain from

scheduling meetings or reimbursing dues or expenses at such

clubs. California Lawyers Move on All-Male Clubs, N.Y. Times,

Aug. 31,; 1986, at 35A, col. 1. In so doing, the Bar recognized,

"continued adherence to those policies and practices imposes an

unfair and arbitrary professional disadvantages on those members

of the [Bar] Association who are subjected to discrimination,

and...such discriminatory policies and practices are antithetical

to the principles of justice for which this Association stands."

San Francisco Bar Ass'n. Resolution, June 11, 1986.

The California Judges Association voted to amend its

judicial code of ethics to state that it is "inappropriate" for

members of the judiciary to belong to such clubs. Hager, Judges

Vote to Avoid Discriminatory Clubs, L.A. Times, Sept. 16, 1986,

at 1, col. 2. In like fashion, the Judicial Conference of the

United States had amended the commentary to Cannon 2 of its code

of Judicial Conduct in 1981 to provide that "it is inappropriate

for a judge to hold a membership in any organization that

-17-

For the first time,practices invidious discrimination."

however, the California amendment declined to leave it up to a

judge's discretion whether the organizatioin he belonged to was

guilty of "invidious discrimination." Id.

B. Application of the Unruh Act to Rotary International

Does Not Infringe Club Members' First Amendment Rights

California's Unruh Act serves to carry out

what Justice O'Connor in her concurring opinion in Roberts,

supra, termed "the power of the States to pursue the profoundly

important goal of ensuring nondiscriminatory access to commercial

opportunities in our society." 468 U.S. ____. In contrast to

this compelling interest, it is clear that application of the

Unruh Act to Rotary does not abridge either of the two components

of the First Amendment right of association identified in

Roberts.

1. Enforcement of the Unruh Act Does Not Abridge

Club Members' Freedom of Intimate Association.

In Roberts this Court observed that the concept of

freedom of intimate association is rooted in notions of personal

liberty and affiliation particularly characteristic of families.

The Court described the kinds of relationships which deserve

freedom of intimate association protection as being

"distinguished by such attributes as relative smallness, a high

degree of selectivity in decisions to begin and maintain the

affiliation, and seclusion from others in critical aspects of

the relationship". 468 U.S. at ____. The Court also noted that

in determining where a particular association lies on the

spectrum between truly intimate relationships deserving First

Amendment protection and those such as a large business

-18-

enterprise that do not, other factors may be relevant, including

"purpose, policies...and other characteristics that in a par

ticular case may be pertinent." 468 U.S. at ____.

Rotary argues that its clubs are selective in their mem

bership, governed by their members, restrict participation to

members, have fellowship in service as their prime purpose and

are therefore entitled to protection of their freedom of intimate

association. (App. Brief at ii). Examination of the true nature

of Rotary International and its individual clubs as revealed in

Rotary's Manual of Procedure and other sources demonstrates that

because of Rotary's size, its intense concern with growth and

publicity, the enforced "intimacy" of members of one club with

hundreds of thousands of men worldwide, the participation of

guests and the public in most Rotary events, the provision of

business management training to members and, most important, the

thoroughly commercial basis of its selection system, Rotary's

members do not have any intimate association to protect.

(a) Selectivity. The crux of Rotary's argument is that

it is distinguishable from Jaycees because, unlike that organiza

tion, which accepted any man aged 18-35 with the ability to pay,

Rotary has a "selective" membership policy. If all that is meant

by "selective" is the dictionary definition of making a choice,

Rotary does indeed have a "selective" membership policy. But to

elevate the mere making of a choice to the embodiment of intimacy

without inquiring into the basis for that choice is to elevate

form over substance.

The repeatedly stated criteria for what makes a club

private include not only that members be selected as opposed to

-19-

admitted wholesale, but that "membership is determined by subjec

tive, not objective criteria." In the Matter of U.S. Power

Squadrons, 465 N.Y.S.2d 871, 876 (Ct. App. 1983), Wright v. Cork

Club, 315 F.Supp. 1143, 1153 (1970). Members of a truly private

club are chosen for their personal attributes as human beings,

not because of where they are employed.

Contrary to this standard of subjectivity, Rotary's

"selectivity" is completely premised on objective business-

related critera. Rotary's selection process utilizes a

"classification of business or profession within the community."

(App. Brief at 7). When a new member is proposed, the classifi

cation committee ascertains "that there is an open classification

of business or profession and that the prospective member's bus

iness or profession is accurately described by the

classification." (App. Brief at 8). The membership committee

evaluates the candidate from the standpoint of character, busi

ness and social standing." (App. Brief at 8, emphasis supplied).

"An active member of a local Rotary Club must work in a

leadership capacity (owner, partner, manager, ej: al.) in a

business or profession in which he is classified." (App. Brief

at 8.)

Roberts, speaks of selectivity in the decision to main

tain the affiliation as well as to begin it. The Court of

8/ Requiring Rotary to admit women will not deprive it of

the right to choose members for their business/professional affi

liations or their congeniality. The effect of applicaiton of the

Unruh Act is only to bar exclusion on invidious discriminatory

grounds not entitled to constitutional protection.

-20-

Appeals noted that according to the testimony of a former Rotary

district governor, many Rotary clubs experience a ten percent

turnover rate, and that in larger clubs the turnover rate is as

high as twenty percent. (Slip. Op. at 22). Rotary's concern

with disaffiliation is apparent in the Manual of Procedure which

stresses ways of reducing membership losses. (Manual of Proc. at

141) .

Beyond the fact that Rotary's selection system is

thoroughly tainted by commercialism, which is enough to undermine

its claim to a right of intimate association, examination of its

size, use of publicity, lack of seclusion and business purpose

make clear that Rotary does not meet the criteria which mark an

organization as truly private.

(b) Size. In August 1982, Rotary had 907,750 members,

making it three times the size of Jaycees. Appellant's

repeatedly state that dividing this number by the 19,788 Rotary

clubs then in existence gives an average club membership of 46.

This average is even larger than the Jaycees, and some Rotary

Clubs, like the Jaycees chapters that were parties in Roberts,

have several hundred members. The Bakersfield, California Rotary

Club, for example, has 200 members. (Slip. Op. p. 30). A club

in the Seattle area has over 750 members. Rotary Club of Seattle

- International District v. Rotary International (W.D. Wash.

No. C86-1475M) Hough Decl. 11 3, 4.

Moreover, members do not relate only to the members of

their choosing in their own club, as one would expect in an inti

mate relationship. Because Rotary requires members to attend

meetings every week in whatever city they may find themselves

-21-

(Rotary Basic Library, Vol. 1 at 67-69), members are in

"intimate" association not only with the members of their own

clubs, but in varying degrees with the more than 900,000

Rotarians worldwide.

Rotary further departs from the "relative smallness"

required for intimate association protection by its assiduous

pursuit of growth. Recruitment is as central to the operation of

Rotary as it is to the Jaycees. In her concurring opinion in

Roberts, Justice O'Connor cited the finding of the Minnesota

District Court that the Jaycees "encourages continuous recruit

ment of members with the expressed goal of increasing member

ship..." 468 U.S. at _____ . Rotary's constitution and Manual

of Procedure document Rotary's commitment to this same goal.

The constitution states that the purposes of

International are "[t]o encourage, promote, extend and supervise

Rotary throughout the world." (Art. II of the International

chapter entitled "Extension of Rotary" states that it is the

"duty" of the board, all governors and all members of Rotary to

do everything in their power constantly to open new clubs world

wide and make clear that extension of Rotary is an absolute

priority. (Manual of Proc. at 92-99). The chapter on

"Membership in Rotary Clubs" gives explicit directions as to how

each club's membership development committee should operate to

recruit new members and maintain a constant "pattern of growth".

(Manual of Proc. at 134-46). The "Public Relations" sections

directs that each club is to have a public relations committee

which is to use every possible method — a detailed list is

offered — to keep Rotary's name before the public as a prime

-22-

means of "Attracting Men to Rotary Through Public Relations".

(Manual of Proc. at 166-68). Rotary's success in achieving

growth is evident from the fact that whereas membership stood at

907,750 members in 19,788 clubs when this suit commenced in

1982, today there are 1,021,624 members in 22,470 clubs. Vital

Statistics, 150 The Rotarian, No. 1 at 1 (January 1987). This

avid appetite for growth is incompatible with concepts of inti

macy and seclusion.

(c) Publicity. Both In the Matter of U.S. Power

Squadrons, supra, and Wright v. Cork Club, supra, held that among

the criteria to be examined in determining whether an organiza

tion is a private club is whether an organization's "publicity,

if any, is directed solely and only to members for their infor

mation and guidance." Id. at 1153. Similarly, Cornelius v.

Benevolent Protective Order of Elks, 382 F.Supp. 1182 (D. Conn.

1974) held that one of the factors in such a determination is

whether the organization advertises. Ij3. at 1203.

Rotary's Manual of Procedure reveals a virtual obsession

with directing publicity to the public and keeping Rotary

constantly in the public eye. The Manual of Procedure directs

clubs' public relations committees "to take a comprehensive

approach to public relations", and "to utilize newspapers, radio,

television, magazines and firms in telling the Rotary story" and

"providing greater public relations impact". (Manual of Proc. at

166-67).

Rotary's constant attention to publicity is another

means by which it confers a business advantage on its members,

who are regularly brought into the public eye with both their

-23-

Rotarian status and business classification identified. As with

its appetite for growth, Rotary's appetite for publicity is

antithetical to concepts of intimacy and seclusion.

(d) Seclusion. Rotary's claim that its clubs "have

well defined policies restricting participation to members"

(App. Brief at ii) is belied by the Manual of Procedure.

Individual members are urged to make "a special effort" to invite

guests to weekly meetings "in order that non-Rotarian members of

the community may be better informed about the function of the

Rotary Club and its aim and objects." (Manual of Proc. at 35).

Like Jaycees, Rotary conducts a wide range of community service

projects in which members of the public of both sexes and other

organizations participate. (Manual of Proc. at 42-48).

Non-Rotarians are invited to speak at business relations con

ferences (Rotary International No. 540) and international conven

tions (Manual of Proc. at 54). This Court could well have been

speaking of Rotary when it wrote of the Jaycees in Roberts,

"[N]umerous non-members of both genders regularly participate in

a substantial portion of activities central to the decision of

many members to associate with one another, including many of

the organization's various community programs, awards ceremonies,

and recruitment meetings." 468 U.S. at ____.

With respect to women's participation in Rotary,

appellants' urge that, unlike Jaycees, Rotary has no women's

affiliates and that to introduce women into Rotary would, there

fore be a sharp break with tradition. Although women are not

official affiliates of Rotary (Manual of Proc. at 68), the Manual

of Procedure specifically commends the "fine work" peformed by

-24-

"ladies committees or other associations composed of women rela

tives of Rotarians cooperating with and supporting them in ser

vice and other Rotary club activities." (Manual of Proc. at 47).

A recent Rotarian article names these groups as the Rotary Anns,

Inner Wheel and Las Damas de Rotary. Uhlig, Do Women Belong in

Rotary? No, 150, The Rotarian, No. 1, p. 15, et seq. (January

1987).

(e) Purpose. Appellants assert that in Rotary

"fellowship in service to the public is of prime importance."

(App. Br. at 18). Although Rotary does engage in a variety of

community service projects, service to the public is only one of

it purposes. Rotary's Basic Library states that Rotary's

founder, Paul Harris, "had an idea that friendship and business

could be mixed and that doing so would result in more business

and more friendship for everyone involved" and quotes Harris as

having written of the early Rotarians: "In the main their

efforts were directed to keeping each other in business, helping

each other to attain success. They patronized each other when it

was practical to do so, exerted helpful influence, and gave wise

counsel when it was needed." (Rotary Basic Library, Vol. 3,

Vocational Service, at 5, and 6-8).

Concern for members' business success continues to be a

prime feature of Rotary activities. Rotary International No. 540

describing Rotary run "Business Relations Conferences," states,

"One of the most satisfying vocational ser

vice programs for the Rotarian is the busi

ness relations conference. The Rotarian

learns management techniques that help

improve his own business or professional

-25-

skills. He receives the inspiration of

discussing business problems with experts

in his own or related fields."

The Manual of Procedure, under "Business Advice and

Assistance to Rotarians", urges each club to establish committees

to provide confidential business advice for members and to hold

"clinics" for members to discuss problems of an economic nature.

(Manual of Proc. at 38).

The Court of Appeals noted that, despite Rotary

International's written proscription prohibiting "any attempt to

use the privilege of membership for commercial advantage" (Rotary

Basic Library, Focus on Rotary, vol. 1, p. 2), four Rotarians

testified that they joined Rotary to take advantage of the busi

ness opportunities membership offered, and that dues were paid by

employers or taken as personal business deductions. That court

properly concluded:

"The evidence simply does not support the

trial court's finding that the business

advantages are merely incidental. By

limiting membership in local clubs to

business and professional leaders in the

community, International has in effect

provided a forum which encourages busi

ness relations to grow and which enhances

the commercial advantages of its

members".

Rotary Club of Duarate v. Directors of Rotary International, 178

Cal.App.3d 1035, _____ , 224 Cal.Rptr. 2, ______ (1986).

But perhaps the best evidence of the business nature of

the clubs is the pervasive deduction as business expenses of mem

bers' dues and club-related expenses. Innumerable surveys and

interviews have revealed the apparently common practice of

-26-

members and their employers in claiming these expenses as busi

ness deductions. One survey found that 58% of banks and 53% of

savings and loan associations contacted regularly paid membership

dues in private organizations for their executives. Burns,

supra, 18 Harv. C.R.-C.L. L. Rev. at 329 n. 22. Law firms sur

veyed for another article reported that many reimbursed lawyers

for dues and, even those that did not, repaid client entertain

ment charges spent at such clubs. See 'Male* Clubs: Bar

Leaders are Members, The Recorder, July 22, 1986. The full

extent of this practice can be seen best in a letter sent by the

former president of New York City's University Club to its mem

bership: "A recent analysis of dues and expense payments showed

that nearly 40% of receipts were paid by checks drawn on business

accounts: this is only a part of the total since may persons pay

on their own account and then obtain reimbursement from

employers." Letter of J. Wilson Newman, March 30, 1981,

Testimony of the New York City Comm'n. on the Status of Women in

Support of Intro. 513 Before the General Welfare Committee, July

30, 1980. In fact, the financial dependence of most private

clubs on business support is substantial. The National Club

Association has estimated that the average city club would lose

more than $450,000 and the average country club $300,000 if

employers withdrew their finan cial support. Burns, supra, 18

Harv. C.R.-C.L. Rev. at 393. In 1980, the same Association

reported that 37% of city clubs' and 26% of country clubs' income

came from company paid memberships. The All-Male Clubs:

Threatened on all Sides, Business Week, Aug. 11, 1980, at 90.

-27-

Rotary International is no different. The trial court

record disclosed that Rotary members often deduct their dues as a

business expense obtain reimbursement from their employers. At

least three of petitioner's witnesses testified that either

their employers paid their dues (R.T. 20, 32, 69) or that the

Internal Revenue Service allowed the deduction during income tax

audits. (R.T. 4, 20). A former treasurer of the Bakersfield

Rotary Club testified that, out of the club's 200 members, the

dues of all but eight or ten were paid by their companies or

business. (R.T. 70.)

Such practices clearly belie any argument that such

clubs are purely social organizations. The federal Internal

Revenue Code provides that "all the ordinary and necessary expe

nses paid or incurred during the taxable year in carrying on any

trade or business" may be deducted from income taxes. 26 U.S.C.

§ 162. For the deduction to be allowed for a club-related

expense, federal tax regulations further require that a club be

used for business purposes at least 50% of the time. Treas. Reg.

§ 1.274-2 (e) (4) (iii) (1982). Thus, a member cannot simulta

neously argue that his club does not serve any commercial or

business function while deducting dues and other charges as a

business expense. Treating club-related expenses as a business

deduction is prima facie evidence that membership serves a busi

ness purpose or confers a professional advantage.

When all these indicia of "private" status — selec

tivity in affiliation and disaffiliation, size, publicity, seclu

sion, purpose — are examined, it is clear that Rotary does not

meet the criteria enunciated in Roberts and other federal and

-28-

state cases for an organization entitled to protection of its

right of intimate association. Most damaging to Rotary is the

point on which it has pinned this case: selectivity. The fact

that Rotary's entire selection process is rooted in commercial

concerns, and that from this flows the fact that business advice

and assistance to fellow Rotarians are a central feature of its

operation, must remove Rotary from the ambit of organizations

which can be deemed distinctly private.

2. Enforcement of the Unruh Act's Anti-Discrimination

Provisions Does Not Abridge Club Member's Freedom

of Expressive Association.

The second aspect of the constitutional right of asso

ciation identified in Roberts is the "freedom of expressive

association." As the court there explained, this right derives

from a series of decisions in which this Court has recognized a

"right to associate for the purpose of engaging in those activi

ties protected by the First Amendment — speech, assembly, peti

tion for the redress of grievances, and the exercise of

religion. 104 S.Ct. at 3249. Rotary International and its

individual club members, however, cannot claim immunity from

California's anti-discrimination law by relying on this component

of freedom of association. To begin with, Rotary and other com

mercially oriented clubs do not promote and practice the sorts of

expressive activities that call forth the special protection of

this constitutional guarantee. Moreover, to the extent club mem

bers may be able to claim any protection from this First

Amendment right, they have not shown, and could not show, that it

is infringed by application of the Unruh Act. Finally, even if

enforcement of the Act should cause some incidential burden on

-29-

the male club members' freedom of expressive association, such a

minimal impact is no greater than necessary to achieve the sta

te's "profoundly important goal of ensuring nondiscriminatory

access to commercial opportunities in our society." _Id. at 3257

(O'Connor, J., concurring).

a. Rotary International and Club Members Cannot

Claim the Protection of the Constitutional

Right of Expressive Association.

In Roberts, this Court explained that the right to asso

ciate for expressive purposes, while not itself explicitly

guaranteed by the Constitution, was a necessary concomitant of

the individual's liberty to engage in protected expressive acti

vities. 104 S.Ct. at 3249-50. As such, the right does not

confer an immunity from government regulation upon all asso

ciations and clubs, but it applies only to those organizations

whose purpose for associating is "the advancement of beliefs and

ideas." NAACP v. Alabama ex rel. Patterson, 357 U.S. 499, 460

(1958). Because Rotary International and the other service and

business-related clubs like it throughout the country are not the

types of organizations whose activities or purposes warrant spe

cial First Amendment protection, they cannot invoke this consti

tutional right in order to maintain their male-only membership

restrictions.

This Court's extension of First Amendment protection to

the internal structure of an association has always been tied to

the rights of free speech, petition, and assembly that are made

textually explicit in the constitution. Yet appellants' theory

of freedom of association would uproot the right to expressive

-30-

association from its First Amendment moorings. They would claim

constitutional immunity from California's antidiscrimination law

for an organization whose primary purposes and activities are

commercial rather than expressive — an entity that has, in

effect, "enter[ed] the marketplace of commerce in a[] substan

tial degree." Roberts, 468 U.S. at _________ , 104 S.Ct. at 3259

(O'Connor, J., concurring). Under the circumstances, acceptance

of appellants' claim of free association would trivialize and

even denigrate the First Amendment's protection of free

expression.

This Court's precedents demonstrate that the degree of

constitutional protection afforded International's activities

depends upon the extent to which they further goals independently

protected by the specific guarantees of the First Amendment.

Discriminatory conduct, for example, is not entitled to constitu

tional protection simply because it is practiced by a group,

rather than by individuals. Rather, the Court must first deter

mine whether Rotary's activities can appropriately be charac

terized as protected expression. For, "[i]t is only when [an]

association is predominantly engaged in protected expression that

state regulation of its membership will necessarily affect,

change, dilute or silence one collective voice that must other

wise be heard." ^d.; see generally, L. Tribe, Constitutional Law

§ 12-23, at 702 (19___) (defining the First Amendment freedom of

association as "a right to join with others to pursue goals

independently protected by the first amendment — such as politi

cal advocacy, litigation (regarded as a form of advocacy), or

religious worship" (footnotes omitted) (emphasis in original).

-31-

Formal recognition of the right to freedom of expressive

association first came in NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449. There,

the Court held that an attempt to compel disclosure of the

NAACP's membership lists was an unconstitutional infringement of

the group's associational freedom. The Court expressed concern

that such disclosure would have a negative impact upon the

NAACP's expressive activity. Noting that " [e]ffective advocacy

of public and private points of view . . . is undeniably enhanced

by group association." (Id. at 460), the Court traced the right

of associational freedom to the right of free speech itself: "It

is beyond debate that freedom to engage in association for the

advancement of beliefs and ideas is an inseparable aspect of the

'liberty' assured by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment, which embraces freedom of speech." I<3.

Consistent with this view that freedom of association is

a necessary corollary to the individual's effective pursuit of

his or her own protected First Amendment rights, the Cout has

been dogged in its protection of political parties and other

political advocacy groups against infringement of their asso

ciational freedoms. See, e.g . , Brown v. Socialist Workers— 7_4

Campaign Committee, 459 U.S. 87, ____ (1982) (state's campaign

disclosure requirements unconstitutional as applied to Socialist

Workers Party); Democratic Party v. Wisconsin, 450 U.S. 107, 121

(1981) (state's mandate that primary results shall determine

allocation of votes case by delegates at National Convention an

unconstitutional interference with Democractic Party s right of

expressive association); Kusper v. Pontikes, 414 U.S. 51, 57

-32-

(1973) ("The right to associate with the political party of one's

choice is an integral part of . . . basic constitutional

freedom.").

But, groups whose activities are not so inherently

expressive have received mixed treatment. For example, in NAACP

v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 429-30 (1963), the Court struck down a

state statute restricting the associational freedom of a law firm

engaged in "political expression" to achieve social goals.

Yet, a law firm engaged in an ordinary commercial practice is

afforded no special First Amendment associational protection.

Thus, in Hishon v. King and Spaulding, 467 U.S. ____,. 104 S.Ct.

2229 (1984), the Court held that a commercial law firm could not

assert its freedom of association as a defense against the enfor

cement of federal antidiscrimination laws. See also Ohralik v.

Ohio State Bar Association, 436 U.S. 447, 459 (19 ) ("A lawyer's

procurement of remunerative employment is a subject only margi

nally affected with First Amendment concerns"). Moreover, this

Court would have reached the same result in Hishon even if the

firm had engaged in a "substantial" amount of activity entitled

to First Amendment protection. Roberts, 104 S.Ct. at 3260

(0:Connor, J., concurring).

Similarly, the Court's extension of First Amendment

associational protection to the internal structure and affairs of

a labor union has depended upon the nature of the union's activi

ties. A labor union representing "the general business needs of

employees," for example, is subject to the government's ratinal

regulation of its membership. Railway Mail Association v. Corsi,

-33-

326 U.S. 88, 94 (1945) (emphasis added). On the other hand, a

union engaged in ideological activity is not. See Abood v.

Detroit Board of Education, 431 U.S. 209, 236 (1977) (State may

not compel association with union advocating political positions,

but is permitted to compel association with union engaging in

commerical activity).

In sum, the right of free speech is at the heart of the

Court's willingness to extend constitutional protection to an

association's internal affairs. Associational status does not in

and of itself confer First Amendment protection; there is no

right to associate per se. Accordingly, Rotary can claim special

First Amendment protection under the banner of freedom of asso

ciation only if it can show that it truly has the purpose of

advancing beliefs or ideas.

Such a showing cannot be made in this case. There is no

indication in the record, and no suggestion in appellants' brief,

that protected expression is even an "insubstantial part" of

Rotary's purposes and activities. Unlike even the Jaycees, whose

activities included a modicum of protected expression on politi

cal, economic, cultural, and social affairs (104 S.Ct. at 3254),

the record in this case is devoid of any mention that the Rotary

has ever taken a public position on issues such as the federal

budget, school prayer, voting rights, or foreign relations. See

id. at 3255.

Moreover, like the Jaycees, Rotary has chosen to

"enter[] the marketplace of commerce in a[] substantial degree,"

and in so doing, it has forfeited "the complete control over its

-34-

membership that it would otherwise enjoy if it confined its

affairs to the marketplace of ideas." Roberts, 104 S.Ct. at 3259

(O'Connor, J., concurring). As the California Court of Appeals

found, the "evidence leaves no doubt that business concerns are a

motivating factor in joining local clubs." J.S. App. C-26.

While, like the Jaycees, Rotarians may "regularly engage in a

variety of civic, charitable, lobbying, fundraising and other

activities worth of constitutional protection," Roberts, 104

S.Ct. at 3254 (citing Village of Schaumburg v. Citizens for a

Better Environment, 444 U.S. 620, 632, 100 S.Ct. 826, 833 (1980),

the Court of Appeals found "that there are business benefits

enjoyed and capitalized upon by Rotarians and their businesses or

employers." J.S. App C-26.-^ The volume of expressive activity

conducted by the Rotarians is simply not enough to overcome a

characterization of the organization as a predominantly com—

merical association. Indeed, that characterization is confirmed

by the common practice among business firms of paying the indivi

dual membership dues of their employees, and of members claiming

their dues as deductible business expenses. See J.S. App. C-25

to C-26; see also Roberts, 104 S.Ct. at 3261 (O'Connors, J., con

curring) (relying on fact that business firms pay for the indivi

dual memberships of employees who belong to the Jaycees).

9/ Appellants persist in citing the trial court opi

nion to the effect that the business benefits of Rotary mem

bership are "incidental to the [association's] principal

purposes," (Brief for Appellant, at 29 (quoting from J.S. App.

B-3)), even though that finding has been discredited and is of no

import under California law. See above.

-35-

Accordingly, the Court should not allow Rotary's sweeping invoca

tion of associational freedom to insulate it from coverage of

10/California's anti-discrlmination law.—

b. Enforcement of the Unruh Civil Rights Act Would

Not Interfere With Any Expressive Purposes or

Activities of Rotary International and Other

Business-Related Clubs.

Even if it could be said that the Rotary and other

business-related clubs engage in activities that invoke the pro

tection of the First Amendment right of expression, the clubs

"have failed to demonstrate that [the Unruh Civil Rights Act]

imposes any serious burdens on the male members' freedom of

expressive association." Roberts, 104 S.Ct. at 3254. In par

ticular, there is "no basis in the record for concluding that

admission of women as full voting members will impede the organi

zation's ability to engage in these protected activities or to

disseminate its preferred views." Id.

There is, of course — as this Court recognized in

Roberts — no conceivable ground for positing that the con

sideration of women for membership in Rotary would somehow

10/ This is not to suggest that an essentially commer

cial enterprise possesses no First Amendment protection for its

internal affairs and organization. Amici would not deny that the

infringement of associational rights, even in a commercial con

text, must bear a rational relation to a state interest.^ See,

e.g., Abood, 431 U.S. at 222 (interference with labor union's

associational freedom may be justified by government s interest

in industrial peace). Here, however, the State of California has

a legitimate interest in ensuring that the commercial opportunity

of Rotary membership is denied to no California citizen solely on

the basis of race, sex, or some prohibited classification.

-36-

interfere with the organization's stated objective: to "provide

humanitarian service, encourage high ethical standards in all

vocations and help build goodwill and peace in the world." 1981

Manual of Procedure, at 7 [J.A. ___] ^ Nor does rendering of

civic services and responding to community needs in any way

require a single-sex membership. To the contrary, the record

established that many Rotary clubs, with the encouragement of the

International, seek the close cooperation and support of women in

their service and other club-related activities, even

establishing auxiliary women's committees for this very purpose.

11/ Any secondary objective of promoting fellowship and

camraderie among Rotary's members, although no deserving of the

special constitutional protection reserved for expressive activi

ties (see Part _______ , supra), is likewise not abridged by the

admission of women into Rotary. As the New Jersey courts have

declared in rejecting a similar freedom of association defense to

the hitherto male-only restriction of Little League membership:

Little League also points to the vaunted aims of the

organization, mentioned in its federal charter of

development in children of "qualities of citizenship,

sportsmanship, and manhood," and it implies these

objectives will be impaired, in the case of boys, by

admission of girls to the activity. We are quite unable

to understand how these conclusions are arrived at.

Moreover, assuming "manhood," in the sense of the

charter, means basically maturity of character, just

as does "womanhood," we fail to discern how and why

little girls are not as appropriate prospects for

learning citizenship and sportsmanship, and developing

character, as boys."

National Organization for Women v. Little League Baseball, Inc.,

127 N.J. Super. 552, 318 A.2d 33, 39 aff'd, 67 N.J. 320, 338

A.2d 198 (1974). In any event, the local Duarte Rotary chapter

certainly did not believe that the admission of women would

interfere with the fellowship and camaraderie of its male

members.

-37-

Cf. Roberts, 104 S.Ct. at 3254-55(Id. at 47 [J .A. ____

(participation of women in many of Jaycees' activities dispels

claim that admission of women will impair organization's symbolic

message). In short, as in Hishon v. King & Spalding, ___U.S.

___, ___ , 104 S.Ct. 2229, 2235 (1984), appellant "has not shown

how its ability to fulfill such a function would be inhibited by

a requirement that it consider [a woman] for [membership] on her

merits.

Indeed, Rotary International does not really contend

that requiring local clubs to consider women for membership would

interfere with the achievement of any of the organization's com

mendable service objectives. Rather, it asserts only that

admitting women to membership in local California clubs, as the

Duarte chapter desires to do, "would comprise a material inter

ference with deeply felt choices of associational preference of

many Rotarians." (Appellants' Brief at 34; see also J.S. App.

12/ This is typical of most of the so-called "private"

business clubs and service organizations throughout the country.

Women are often allowed (and sometimes encouraged) to participate

in the club's activities as wives or guests, while being denied

the commercial opportunities and advantages that first-class

membership would provide.

13/ Appellant International also contends that

requiring it to permit local clubs to admit women "would risk a

material and harmful disruption of the cooperative integrity of

Rotary" due to its dependence on "a delicate balance of divergent

attitudes in diverse cultures." Appellants' Brief, at 34.

Aside from the fact that the Court of Appeals concluded as a

matter of state law that the evidence did not support a finding

that the admission of women into the Duarte chapter "would cause

the downfall of the District or International or seriously

interfere with Rotary's objectives" (J.S. App. ____), the disire

-38-

In sum, a p p l i c a t io n o f the Unruh Act to Rotary

International works no infringement on the organization's or its

members' freedom of expressive association — if only for the

simple reason that the male-only membership restriction bears no

relation at all to the purposes and activities of the Club,

expressive or otherwise. Like the Minnesota law at issue in

Roberts, the Unruh Act "requires no change in the [Rotary's]

creed . . . , and it imposes no restrictions on the organiza

tion's ability to exclude individuals with ideologies or philo

sophies different from those of its existing members." 104 S.Ct.

at 3254; cf. J.S. App. C-___ ("Unruh Act] does not require

International to change its objectives or to open membership to

the entire public at large, nor does it invalidate its selective

membership requirements."). Accordingly, there is no First

Amendment violation in this case: "The Amendment does not forbid

regulation which ends in no restraint upon expression or in any

other evil outlawed by its terms and purposes." Oklahoma Press

Publishing Co. v. Walling, 327 U.S. 186, 193 (1946). See also

Marchioro v. Chaney, 442 U.S. U.S. 191 (1979).

13/ (cont'd) to appease the "divergent attitudes in

diverse cultures" cannot justify unlawful acts fo discrimination.

When Rotary International conducts its operations in the United

States and the State of California, it subjects itself to th laws

of those "cultures," and the "attitude" of the law in this

country is that women are not to be denied equal access to com

mercial opportunities and advantages. See generally Sumitomo

Shoji America, Inc., v. Avagliano, 457 U.S. 176 (1982) (Japanese

company operating in United States must comply with Title VII

prohibition against hiring only male Japanese citizens for execu

tive, managerial, and sales positions).

-39-

J —__

time and again rejected any notion that the First Amendment

/right of expressive association protects the socialpreferences

of an organization’s members, at least when tjx*se preferences

demand the exclusion of an entire categopyof individuals based

solely on their race or sex: "Indi^ious private discrimina

tion may be characterized as afdrm of exercising freedom of j

association protected by thjs^First Amendment, but it has never'

j

been accorded affirmative constitutional protections.” Norwood

— • Harrison, 413^tKS. 455, 470 (1973); accord, Runyon v.

McCrary. 42^if.S. 160, 175-76 (1976); Hishon v. King & Spalding.

^ 4/ T ■ V _ SRotary International &*- soma other club[ cannot shield ££e££f from_ application of the Unruh Civil Rights Act

by claiming that a belief in its male-only membership policy is

one of the fundamental tenets of the organization, and hence is

expression protected by the First Amendment freedom of associa

tion. This eseentially is the contention raised by amicus

Conference of Private Organizations, which asserts, however

implausibly, that the male-only policy is the sine qua non of

membership for many Rotarians. (See Brief of the Amicus Curiae

in Support of Appellants by the Conference of Private Organiza

tions, at 12-15.) Not only is such an argument unsupported bv

any evidence in this record, but it confuses the right to

promote a particular belief — which is generally protected

under the First Amendment — with the right to practice that

same belief which does not always enjoy constitutional

protection. This distinction was deemed critical by this Court

in declaring the racially discriminatory admission practices of

private nonsectarian schools unlawful under 42 U.S.C. § 1981

After reviewing the development of the First Amendment right’"to

engage in association for the advancement of beliefs and ideas"

(flugting NAACP v. Alabama. 357 U.S. at 460), the ?ourt explained:

From this principle it may be assumed that parents

have a First Amendment right to send their children to

educational institutions that promote the belief that

racial segregation is desirable, and that children

have an equal right to attend such institutions. But

it does not follow that the practice of excluding

racial minorities from such institutions is also protected by the same principle. . .

[cont'd]

In sum, a p p l i c a t io n o f the Unruh G-i v i l Rirghfr̂ Act to

Rotary International works no infringement on the organization's

or its members' freedom of expressive association — if only for

the simple reason that the male-only membership restriction

bears no relation at all to the purposes and activities of the

Club, expressive or otherwise. Like the Minnesota law -at issue

in Roberts, the Unruh Act "requires no change in the [Rotary's]

creed . . . , and it imposes no restrictions on the organiza

tion's ability to exclude individuals with ideologies or

philosophies different from those of its existing members." 104

S.Ct. at 3254; £f. J.S. App. C-___ ("[Unruh Act] does not

require International to change its objectives or to open

membership to the entire public at Large, nor does it invalidate

its selective membership requirements."). Accordingly, there is

no First Amendment violation in this case: "The Amendment does

not forbid regulation which ends in no restraint upon expression

or in any other evil outlawed by its terms and purposes."

Oklahoma Press Publishing Co. v. Walling, 327 U.S. 186, 193

(1946). See also Marchioro v. Chaney. 442 U.S. 191 (1979)

Runyon v. McCrory, 427 U.S. at 176 (emphasis in original). See

also Railway Mail Association v. Corsi, 326 U.S.88. 93-94 (19 45~ —

It is conceivable, perhaps, that for some types of pwLa-t

organizations, such as the Klu Klux Klan, the expressive content

of its discriminatory membership criteria is so intimately tied

to the very purposes, beliefs, and pronouncements of the

organization, that government regulation of' its membership

criteria would constitute an infringement on its freedom of

expression, requiring a court to determine whether that

infringement may nevertheless be justified by compelling state

interests that could not be achieved by less restrictive means.

But that is certainly not the situation here.

^ [cont,'d]

(right to associate for political purposes is not infringed by

state regulation of political parties that does not in fact

burden the exercise of any political rights).

Z. Any Intrusion on Rotary International's or Its

Club Members* Freedom of Expressive Association

Is Justified by the Compelling State Interest in

Ensuring Non-Discriminatory Access to Commercial

Opportunities in Our Society.

This Court has often admonished that, however valued

the right to associate for expressive purposes may be, it is not

absolute. Rather, " [i]nfringements on that right may be

justified by regulations adopted to .serve compelling state

interests, unrelated to the suppression of ideas, that cannot be

achieved through means significantly less restrictive of

associational freedoms." Roberts, 104 S.Ct. at 3252 (citing

cases). Here, as in Roberts, to the extent that application of

the Unruh Civil Rights Act creates any burden on appellants'

right to associate, that impact is no greater than is necessary

to achieve the state's goal of eradicating discrimination, a

compelling state interest "of the highest order." Id. at 3253.

Rights Act — and its application to Rotary International in

this case — "plainly serves compelling state interests of the

highest order." Id. The State uf California, sensitive t

i and pluralistic nature of its populace'^s well as to- its

_____ I fnral origins^ has histor ically been deeply committed tb'̂

As discussed in Part ____, supra, the Unruh Civil

•j Ls citizens an environment where all percons,

PK77#3

3 of race, creed, color, national origin, or sex,/have a fair

andx «cjual opportunity to participate fully in tho^business,

professional, civic, and political life of th/ community. This

commitment\s embodied not only in laws liXe the Unruh Act and

the general constitutional proscriptions against invidious

discrimination, bb£ in a specific st^te constitutional guarantee

safeguarding every ir^ividual's right freely to pursue business

and professional opportuh^ties/vithout regard to his or her

"sex, race, creed, color, ot\national or ethnic origin." Cal.

Const., Art. I, sec. 8. /California has found, with ample

support (see Part / supra), thbh one very real barrier to

the advancement of Women and minorities in the business and

professional life of the state is the discriminatory practices

of certain membership organizations where business opportunities

are promoted, deals are frequently made, and the\personal